Chapter 1: Introduction to the Canadian recommendations for the prevention and treatment of malaria

Last complete chapter revision: February 2024

On this page

Preamble

The Committee to Advise on Tropical Medicine and Travel (CATMAT) provides the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) with ongoing and timely medical, scientific, and public health advice relating to tropical infectious disease and health risks associated with international travel. PHAC acknowledges that the advice and recommendations set out in this statement are based upon the best current available scientific knowledge and medical practices, and is disseminating this document for information purposes to both travellers and the medical community caring for travellers.

Persons administering or using drugs, vaccines, or other products should also be aware of the contents of the product monograph(s) or other similarly approved standards or instructions for use. Recommendations for use and other information set out herein may differ from that set out in the product monograph(s) or other similarly approved standards or instructions for use by the licensed manufacturer(s). Manufacturers have sought approval and provided evidence as to the safety and efficacy of their products only when used in accordance with the product monographs or other similarly approved standards or instructions for use.

Introduction

Malaria is a common and potentially fatal parasitic infection in human beings. It is a protozoan disease transmitted by the bite of infected female anopheline mosquitoes. Rarely, transmission may occur through transfused bloodFootnote 1Footnote 2, solid organ transplantationFootnote 2, needle sharing, or from mother to fetusFootnote 3. Five different species of the genus Plasmodium cause malarial infection in humans: Plasmodium falciparum and Plasmodium vivax cause most cases globally, whereas Plasmodium ovale and Plasmodium malariae global burden is low, and the zoonotic Plasmodium knowlesi is found predominantly in southeast Asia. The clinical impact of molecularly identified zoonotic Plasmodium cynomolgi and Plasmodium simium in humans is not fully understoodFootnote 4Footnote 5.

Clinical manifestations of malaria are dependent on the age and immune status of the host. The spectrum of clinical effects ranges from asymptomatic parasitemia and uncomplicated malaria to severe malaria and potentially death. Undifferentiated fever is most commonly caused by malaria in endemic areas. The disease is characterized by non-specific flu-like symptoms, such as myalgia, fatigue, headache, abdominal pain, and malaise, which are followed by irregular fever and rigors. Nausea, vomiting, jaundice, and orthostatic hypotension also commonly occur. The alternate-day or periodic fevers described in the literature are rarely observed in Canada due to asynchronous infections and prompt treatment.

The symptoms of malaria are nonspecific and definitive diagnosis is not possible without parasitologic testing, which can be done using microscopy of a blood film, an antigen detection test (rapid diagnostic test), or molecular testing. See Malaria: Chapter 6 for information on malaria diagnosis.

Infections caused by P. falciparum have the highest fatality rate, however P. vivax and P. knowlesi can also cause severe disease. Malaria-associated deaths are frequently the result of delays in the diagnosis and treatment of the infectionFootnote 6Footnote 7. Most deaths due to malaria are preventable.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), an estimated 249 million cases of malaria occurred worldwide in 2022, with approximately 95% of these cases reported in 29 countries. Notably, 4 countries accounted for nearly 50% of all malaria cases globally, namely Nigeria, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Uganda, and MozambiqueFootnote 7. In 2022, approximately 608,000 deaths due to malaria were reported worldwide, with over 50% occurring in 4 countries: Nigeria, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Niger, and the United Republic of TanzaniaFootnote 7.

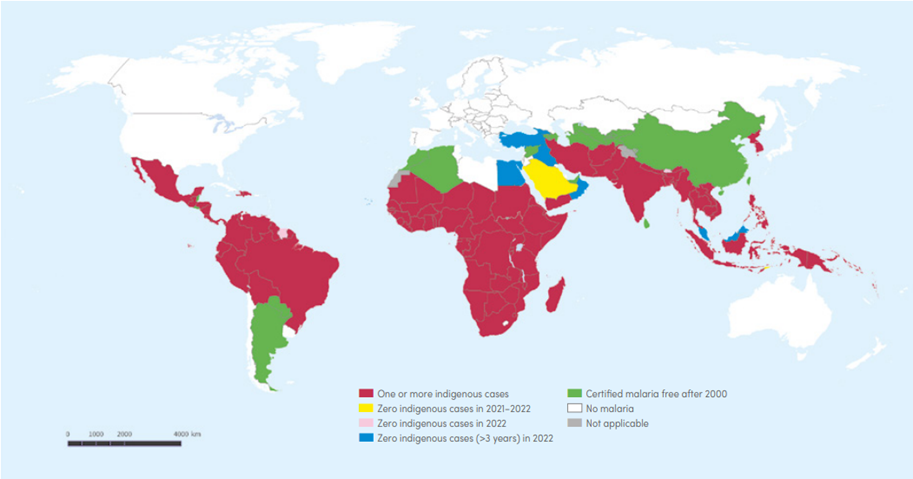

With the success of the Millennium Development Goal to halt and reverse the incidence of malaria by 2015, the subsequent Sustainable Development Goals aim to end malaria epidemics by 2030Footnote 8. To meet this target, the Global Technical Strategy for Malaria proposes to reduce malaria mortality and incidence by at least 95%, eliminate malaria from at least 35 countries where it is transmitted, and prevent re-establishment of malaria in all countries that are malaria free by 2030 compared with 2015Footnote 8. Figure 1 shows the key indicators towards malaria control and elimination in reported malaria incidence between 2000 and 2021. Progress may be undone by the widespread resistance of P. falciparum to chloroquine and sulfadoxine-pyrimethamine, the more recent emergence of artemisinin-resistance in the Greater Mekong Subregion and elsewhere, resistance to insecticides, and declining sensitivity of rapid diagnostic testsFootnote 7.

Figure 1: Text description

Areas with 1 or more indigenous cases:

- Central America, excluding:

- Bahamas

- Belize

- Cuba

- El Salvador

- Jamaica

- Puerto Rico

- South America, excluding:

- Argentina

- Chile

- Falkland Islands

- Paraguay

- Suriname

- Uruguay

- Africa, excluding:

- Algeria

- Cabo Verde

- Egypt

- Libya

- Morocco

- Tunisia

- Western Sahara

Areas with 0 indigenous cases between 2021 and 2022:

- Saudi Arabia

- Timor-Leste

Areas with 0 indigenous cases in 2022:

- Bhutan

- Suriname

Areas with 0 indigenous cases (>3 years) in 2022:

- Egypt

- Georgia

- Iraq

- Malaysia

- Oman

- Türkiye

Areas certified malaria free after 2000:

- Algeria

- Argentina

- Armenia

- Azerbaijan

- Belize

- China

- El Salvadore

- Israel

- Kyrgyzstan

- Morocco

- Paraguay

- Sri Lanka

- Syria

- Taiwan

- Tajikistan

- Turkmenistan

- United Arab Emirates

- Uzbekistan

Areas with no malaria:

- Australia

- Canada

- Chile

- Cuba

- Europe

- Jamaica

- Japan

- Kazakhstan

- Lesotho

- Libya

- Mongolia

- New Zealand

- Russia

- Tunisia

- United Kingdom

- United States of America

- Uruguay

Not applicable:

- Jammu and Kashmir

- Western Sahara

Countries with 0 indigenous cases for at least 3 consecutive years are considered to have eliminated malaria. In 2022, Malaysia reported 0 indigenous cases caused by human Plasmodium species for the fifth consecutive year and Cabo Verde reported 0 indigenous cases for the fourth year. Belize was certified malaria free in 2023, following 4 years of 0 malaria casesFootnote 7.

The Canadian Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System (CNDSS), a passive surveillance system coordinated by PHAC, is used to monitor more than 40 nationally notifiable infectious diseases. Notification by provinces and territories to the federal level is voluntary, and cases are based on predetermined surveillance definitions. From 2010 to 2021, 5,390 cases of malaria were diagnosed and reported to the CNDSS, with an annual average of 449 cases (range: 185 to 611). Between 2010 and 2021, 23% of the 5,390 reported cases were among those aged 19 years or younger. In 2018, Ontario stopped surveillance and reporting of malaria cases among diseases of public health significance, resulting in a 39% decrease in all CNDSS-reported malaria cases compared to 2017.

From 2010 to 2018, there were 16,355 malaria cases reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in the United StatesFootnote 9. The annual average of 1,817 malaria cases (range: 1,524 to 2,161) reported in the U.S. has been increasing since 1972. This trend parallels the increasing number of international flights by U.S. citizens. In 2018, children (< 18 years) represented 16.1% of these cases (294 of 1,823), with 66 (3.6%) aged 5 years or younger. Severe malaria was diagnosed in a total of 251 (13.8%) of 1,823 cases in 2018, of which 2.8% (7 of 251) patients died.

There were 84 cases of malaria diagnosed among returned Canadian travellers presenting to the 8 Canadian GeoSentinel Surveillance Network sites in 2022; 76% of these cases were caused by P. falciparum.

The Canadian Malaria Network (CMN), in collaboration with PHAC and Health Canada's Special Access Program, maintains supplies of intravenous artesunate and intravenous quinine at major medical centres across the country to facilitate rapid access to effective treatment of severe malaria.

From January 2016 to December 2022, a total of 708 patients diagnosed with severe or complicated malaria were reported to the CMN. Of these cases, 14.1% were aged 16 years or younger. The majority (75.4%) were assumed to have acquired malaria in Africa. Where the reason for travel was known (n = 564 patients), 55.1% were reported to be visiting friends and relatives, 18.6% were reported to be immigrants, 11.2% were reported to be business travellers, and 7.8% were reported to be on vacation. Parenteral artesunate was requested for 96.3% of cases. It is worth noting that parenteral quinine has not been requested in Canada since 2018. There were delays in malaria management, with a mean wait time of 4.55 days between the onset of symptoms and medical careFootnote 10.

Almost all malaria-associated deaths among travellers are due to P. falciparum. The overall case- fatality rate of imported P. falciparum malaria varies from about 1% to 5% and increases to 20% for those with severe malaria, even when the disease is managed in intensive care unitsFootnote 11Footnote 12. Progression from asymptomatic infection to severe and complicated malaria can be extremely rapid, with death occurring within 36 to 48 hours. The most important factors that determine patient survival are early diagnosis and appropriate therapy.

Footnotes:

- Footnote a

-

This map is intended as a visual aid only; see Appendix 1 for specific country recommendations. Reproduced with permission from: WHO, 2023.

References:

- Footnote 1

-

Slinger R, Giulivi A, Bodie-Collins M, et al. Transfusion-transmitted malaria in Canada. CMAJ. 2001;164(3):377-379.

- Footnote 2

-

Ashley EA, White NJ. The duration of Plasmodium falciparum infections. Malar J. 2014;13:500. Published 2014 Dec 16. doi:10.1186/1475-2875-13-500

- Footnote 3

-

Davies HD, Keystone J, Lester ML, Gold R. Congenital malaria in infants of asymptomatic women. CMAJ. 1992;146(10):1755-1756.

- Footnote 4

-

Brasil P, Zalis MG, de Pina-Costa A, et al. Outbreak of human malaria caused by Plasmodium simium in the Atlantic Forest in Rio de Janeiro: a molecular epidemiological investigation. Lancet Glob Health. 2017;5(10):e1038-e1046. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30333-9

- Footnote 5

-

Ta TH, Hisam S, Lanza M, Jiram AI, Ismail N, Rubio JM. First case of a naturally acquired human infection with Plasmodium cynomolgi. Malar J. 2014;13:68. Published 2014 Feb 24. doi:10.1186/1475-2875-13-68

- Footnote 6

-

Bell D, Wongsrichanalai C, Barnwell JW. Ensuring quality and access for malaria diagnosis: how can it be achieved?. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2006;4(9):682-695. doi:10.1038/nrmicro1474

- Footnote 7

-

World Health Organization. World Malaria Report; 2023. Accessed December 8, 2023. https://www.who.int/teams/global-malaria-programme/reports/world-malaria-report-2023

- Footnote 8

-

World Health Organization. Global Technical Strategy for Malaria 2016-2030; 2015. Accessed October 5, 2023. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/documents/global-technical-strategy-for-malaria-2016-2030.pdf

- Footnote 9

-

Mace KE, Lucchi NW, Tan KR. Malaria Surveillance - United States, 2018. MMWR Surveill Summ. 2022;71(8):1-35. Published 2022 Sep 2. doi:10.15585/mmwr.ss7108a1

- Footnote 10

-

Personal communication, McCarthy AE, 2023.

- Footnote 11

-

McCarthy AE, Morgan C, Prematunge C, Geduld J. Severe malaria in Canada, 2001-2013. Malar J. 2015;14:151. Published 2015 Apr 11. doi:10.1186/s12936-015-0638-y

- Footnote 12

-

Plewes K, Leopold SJ, Kingston HWF, Dondorp AM. Malaria: What's New in the Management of Malaria?. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2019;33(1):39-60. doi:10.1016/j.idc.2018.10.002