Chapter 8 - Drugs for the prevention and treatment of malaria: Canadian recommendations for the prevention and treatment of malaria

Updated 2019

What's new

- Recommendation for consistent Primaquine dose (30 mg base (52.6 mg salt) regardless of geographic area of malaria acquisition.

- Correction in Quinine doses

- New evidence included on use of artemisinin combination therapy (ACT) in pregnant women

- New evidence that doxycycline may be considered for treatment of malaria in children under 8 years when there are no other alternative options

- For the prevention of chloroquine-resistant malaria, mefloquine is now listed as one of several options, along with atovaquone-proguanil, doxycycline or primaquine

- Clarification of follow on multidrug therapy for severe falciparum malaria

- Updated references where appropriate

Chapter 8: Drugs for the prevention and treatment of malaria

- Preamble

- Background

- Methods

- Introduction

- Drugs (In Alphabetical Order)

- Other Drugs not available or not routinely recommended in Canada (In Alphabetical Order)

- Malaria Vaccines – Not available in Canada

- Acknowledgements

- References

Preamble

The Committee to Advise on Tropical Medicine and Travel (CATMAT) provides the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) with ongoing and timely medical, scientific, and public health advice relating to tropical infectious disease and health risks associated with international travel. PHAC acknowledges that the advice and recommendations set out in this statement are based upon the best current available scientific knowledge and medical practices, and is disseminating this document for information purposes to both travellers and the medical community caring for travellers.

Persons administering or using drugs, vaccines, or other products should also be aware of the contents of the product monograph(s) or other similarly approved standards or instructions for use. Recommendations for use and other information set out herein may differ from that set out in the product monograph(s) or other similarly approved standards or instructions for use by the licensed manufacturer(s). Manufacturers have sought approval and provided evidence as to the safety and efficacy of their products only when used in accordance with the product monographs or other similarly approved standards or instructions for use.

Background

This chapter reviews the drugs (in alphabetical order) used for the prevention and treatment of malaria. This information is not comprehensive. Note that product recommendations are subject to change, and health care providers should consult up-to-date information, including recent drug monographs, for any updates, particularly with respect to compatibility, adverse reactions, contraindications, precautions and warnings (See also Chapters 3, 4, 5 and 7).

Methods

This chapter of the CATMAT malaria guidelines was developed by a working group comprised of volunteers from the CATMAT committee. Criteria outlined in the CATMAT statement on Evidence based process for developing travel and tropical medicine related guidelines and recommendationsFootnote 1, were used to decide whether a Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) methodological approach would be required for this chapter. The GRADE approach was not used in this chapter. Advice is based on a narrative review of the relevant literature and on expert opinion. The working group, with support from the secretariat, was responsible for: assessing available literature for any recent contributory evidence, synthesis and analysis, draft recommendations and chapter writing. The most recently published WHO Guidelines for the Treatment of MalariaFootnote 2 which are based on a robust GRADE review of the available evidence, are referenced in this chapter update. Based on the evidence compiled as well as on expert opinion, recommendations for interventions were made, as indicated in tables 8.1 to 8.9.

Introduction

A health care provider should only prescribe drugs for the prevention of malaria after an individual risk assessment (see Chapter 2) in an effort to ensure that only those travellers truly at risk of malaria infection receive chemoprophylaxis. Any drugs taken for malaria chemoprophylaxis should be used in conjunction with personal protective measures to prevent mosquito bites (see Chapter 3).

Like all drugs, antimalarials have the potential to cause adverse effects, though most people using chemoprophylaxis will have no or only minor adverse effects. Careful adherence to dosing guidelines, contraindications, warnings and precautions can minimize any adverse effects. To assess drug tolerance and if time permits, start the antimalarial regimen several days or weeks (depending on the antimalarial prescribed) before travel (see Chapter 4).

In pregnant women, pharmacokinetics of antimalarials are affected by the large volume of distribution and higher clearance rate, suggesting that higher dosages might be warranted, particularly for treatment of malaria in pregnant women. However, no optimal dose has been established and existing prophylactic dosages appear to be effective in preventing malaria in pregnant womenFootnote 3Footnote 4Footnote 5Footnote 6. For more information on the safety of prophylactic antimalarials in pregnant and breastfeeding women, refer to chapter 5.

In light of the increasing prevalence of counterfeit medications in some countries and the potentially serious consequences of inadequate antimalarial prophylaxis or treatment, travellers should buy their antimalarials before leaving Canada (see Chapter 5, section on counterfeit drugs in “Preventing Malaria in the Long-Term Traveller or Expatriate”). Table 8.10 provides information on the base/salt equivalents of selected antimalarial drugs, and Table 8.11 summarizes information, including doses, for the antimalarial drugs routinely used in Canada.

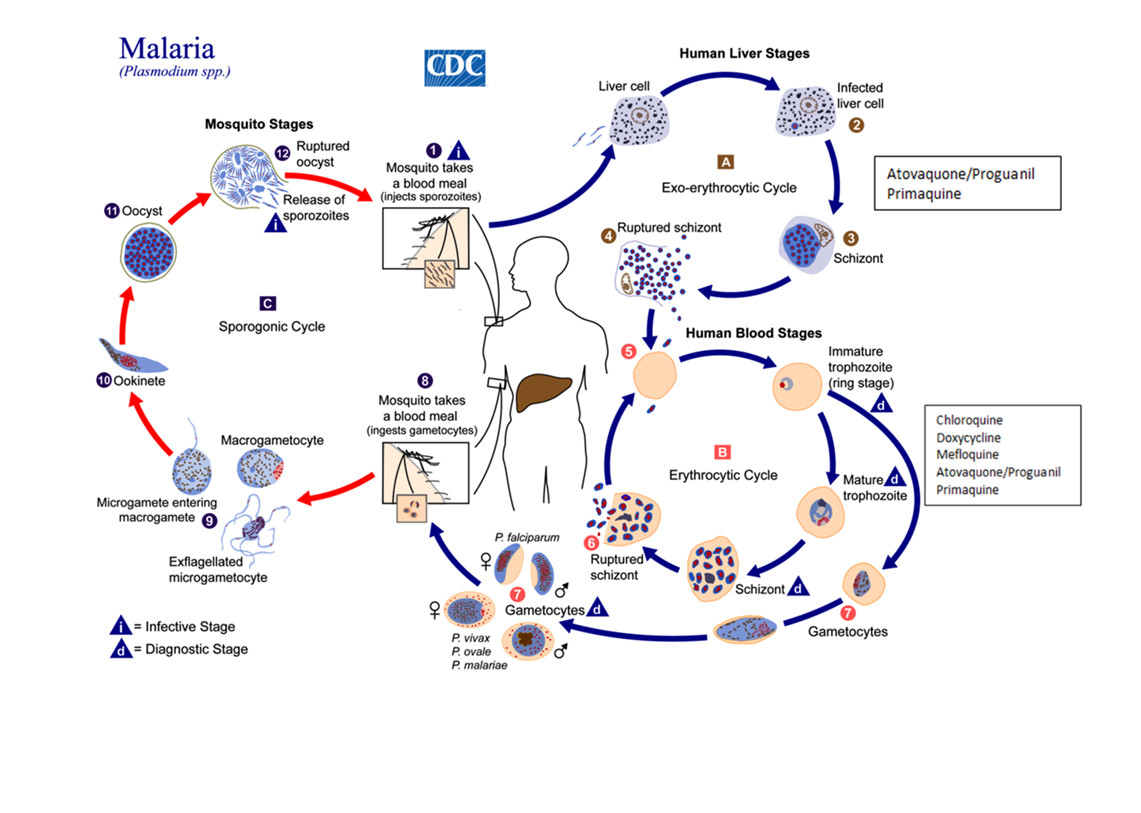

Figure 8.1 depicts the malaria lifecycle and the sites of action of chemoprophylactic agents. The malaria parasite life cycle involves two hosts. During a blood meal, a malaria-infected female anopheline mosquito inoculates sporozoites into the human host ❶. Sporozoites infect liver cells ❷ and mature into schizonts ❸, which rupture and release merozoites ❹.

In Plasmodium vivax and Plasmodium ovale, a dormant stage (hypnozoites) can persist in the liver and cause relapses by invading the bloodstream weeks or even years later. After this initial replication in the liver (exo-erythrocytic schizogony, A, the parasites undergo asexual multiplication in the erythrocytes (erythrocytic schizogony, B. Merozoites infect red blood cells ❺. The ringstage trophozoites mature into schizonts, which rupture releasing merozoites ❻. Some parasites differentiate into sexual erythrocytic stages (gametocytes) ❼. Blood stage parasites are responsible for the clinical manifestations of the disease.

Figure 1 – Long description

This image is of the malaria life cycle and the sites of action of recommended chemoprophylactic drugs. The diagram depicts three cycles, two that take place in the human host and one that takes place in the mosquito host. There are 12 sequential stages shown across the three cycles with arrows indicating direction.

The first cycle is the Exo-erythocytic cycle or human liver stages. First, a malaria-infected female anopheline mosquito takes a blood meal from a human and inoculates sporozoites into the human host. The diagram displays the letter “i” in this first step to indicate that this is the infective stage of malaria. Second, the sporozoites infect liver cells. Third, the infected liver cells mature into schizonts. Fourth, the schizonts rupture and release merozoites.

This leads into the second cycle, the erythrocytic cycle or human blood stages. In the fifth step of the life cycle, the merozoites infect red blood cells. Six, the ring stage trophozoites mature into schizonts, which rupture releasing merozoites. Seventh, some parasites differentiate into sexual erythrocytic stages (gametocytes). The diagram displays the letter “d” during the human blood stage, or erythocytic cycle, to indicate that this is the diagnostic stage of malaria.

This leads into the third cycle, the sporogonic cycle or mosquito stages. In the eighth step of the life cycle, an anopheles mosquito takes a blood meal from a human host and ingests the gametocyctes. Ninth, the microgametes enter the macrogametes. Tenth, this generates zygotes, which become ookinetes. Eleventh, the ookinetes develop into oocysts. Twelfth, the oocysts rupture and release sporozoites, which brings the cycle back to the first step of the life cycle where the mosquito infects a human host by taking a blood meal.

The diagram also depicts which drugs are appropriate for each stage of the malaria life cycle. In the human liver stages, atovaquone/proguanil and primaquine can be used. In the human blood stages, chloroquine, doxycycline, mefloquine, atovaquone/proguanil and primaquine can be used. Refer to the text for a further description of the drugs used.

Agents used for causal chemoprophylaxis include atovaquone-proguanil and primaquine. These drugs act at the liver stage of the malaria life cycle, prevent blood-stage infection, and need only be taken for one week after leaving a P. falciparum malaria-endemic area. Agents used for suppressive chemoprophylaxis (including mefloquine, chloroquine, and doxycycline) act at the erythrocytic (asexual) stage of the malaria life cycle, and hence need to be taken for four weeks after departure from a malaria-endemic area.

Drugs (In Alphabetical Order)

Artemisinin and derivatives

Mechanism of action

Artemisinin (quinghaosu) is an endoperoxide-containing natural antimalarial from sweet wormwood (Artemisia annua). The semi-synthetic analogues of artemisinin, including artesunate, artemether, arteether and dihydroartesinin, are available in oral, parenteral and suppository formulations. They are all metabolized to a biologically active metabolite, dihydroartemisinin (DHA), and exert their antiparasitic effects on many stages of erythrocytic phase parasites, including the younger, ring-forming parasites, thus decreasing the numbers of late parasite forms that can obstruct the microvasculature of the host. All artemisinin preparations have been studied and used for treatment only. They are not recommended for prophylaxis because of their short half-life.

Artemisinin and its derivatives generally produce rapid clearance of parasitemia and rapid resolution of symptoms. The artemisinin derivatives are effective against P. falciparum strains resistant to other antimalarials, but have high recrudescence rates (about 10% to 50%) when used as monotherapy for fewer than five days.

Indications and efficacy

Studies have examined longer durations of therapy (seven days), and artemisinin-based combination therapy of artemisinin derivatives with mefloquine, lumefantrine, amodiaquine or tetracycline–doxycycline to prevent recrudescence. Combination therapy results in higher than 90% cure rates of primary and recrudescent P. falciparum infections. While efficacy remains high in many areas of the world, prolonged parasite clearance times following treatment with some artemisinin-based combination therapies, and also with seven-day artemisinin therapy, have been observed on the Thai/Cambodian border and throughout mainland southeast Asia from southern Vietnam to central MyanmarFootnote 8Footnote 9.

Coartemether (Riamet® in Europe, Coartem® in Africa and the United States) is an oral combination of artemether and lumefantrine. Coartemether is licensed in some European countries and in the United States and is becoming widely distributed in Africa for the treatment of malaria. A six-dose regimen of artemether-lumefantrine appears more effective than some antimalarial regimens not containing artemisinin derivatives, but has not been directly compared to atovaquone/proguanil, or oral quinine based regimensFootnote 10. A review of several studies suggests that mefloquine plus artesunate is as effective as artemether-lumefantrine and may, in fact, be superiorFootnote 11.

Randomized controlled trials comparing parenteral artesunate and quinine for the treatment of severe malaria in both adults and children and in different regions of the world clearly show the benefits of artesunateFootnote 12Footnote 13Footnote 14.

Artemisinin-based combination therapy (ACT) is the recommended first-line treatment for uncomplicated falciparum malaria and for the treatment of malaria when the causative species has not been identifiedFootnote 2. Parenteral artesunate is recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO) as the treatment of first choice for severe or complicated malariaFootnote 2. Artemisinin and its derivatives are available and increasingly used in southeast Asia and Africa, and parenteral artesunate is now available in Canada and can be obtained from the CMN (see Appendix V). Note that IV artesunate should be reserved for those who have severe malaria, where it has been proven superior to quinine. Parenteral quinine is the preferred agent ONLY for those who do not meet WHO criteria for severe malaria and who are unable to tolerate oral therapy. Quinine is preferred in these cases in order to preserve available stocks of artesunate, which are limited in Canada at this time. Both IV artesunate and IV quinine are available through the CMN.

Orally administered artemisinin drug combinations, such as the combination artemisinin-lumefantrine (Coartem®), are recommended by WHO as the treatment of choice for uncomplicated falciparum malaria. Oral artemisinin derivatives are not yet licensed or available in Canada but have been approved in the United States by the Food and Drug Administration.

Adverse effects, contraindications and precautions

Artemisinin and its derivatives are generally well tolerated. Neurologic lesions involving the brainstem have been seen in rats, dogs and primates given repeated doses of artemisinin derivatives, in particular the lipid-soluble derivativesFootnote 15Footnote 16. Such effects have not been observed with oral administration of any artemisinin derivative or with intravenous (IV) artesunate. However, use of inappropriate dose regimens may cause neurotoxicity in humansFootnote 17. Cases of delayed hemolytic anemia (either recurrent or persistent) following use of parenteral artesunate (8 to 32 days after therapy) for severe malaria have been reported worldwide. Patients with high pre-treatment parasitaemia appear to be at higher risk. Post-artesunate delayed hemolysis (PADH) is likely the result of the delayed clearance of once-infected erythrocytes, which continue to circulate after the pharmacologic effect of parenteral artesunate, and is not the result of any toxic effect of parenteral artesunateFootnote 18. Due to the risk of hemolysis, Health Canada and the Canadian Malaria Network (CMN) recommend a CBC be performed weekly for at least 4 weeks following treatment with parenteral artesunate to monitor patients for anemia. In addition, patients treated with IV artesunate should be counselled to report signs of hemolysis, such as dark urine, yellowing of skin or whites of eyes, fever, abdominal pain, pallor, fatigue, shortness of breath and/or chest pain. A study has suggested that treatment of uncomplicated malaria with coartemether may be associated with hearing loss in some people, possibly from synergy between potentially ototoxic agents in combination,Footnote 19 however; the study was limitedFootnote 20 and other research found hearing loss to be only transitoryFootnote 21. To date, there have been two human cases of complete heart block associated with the use of artemisinins, but most volunteer and clinical studies have found no evidence of cardiac adverse effectsFootnote 22Footnote 23.

The safety of artemisinin derivatives in pregnancy has not been established; however, it should be noted that malaria in pregnancy is frequently associated with increased morbidity and adverse outcomes of pregnancyFootnote 2Footnote 24. A review of the limited available data suggests that artemisinins are effective and unlikely to cause fetal loss or abnormalities when used in late pregnancyFootnote 25. Note that none of these studies had adequate power to rule out rare serious adverse events, even in the second and third trimestersFootnote 25. A recent report by WHO reviewed the use of artemisinin combination therapy (ACT) in pregnant women from endemic areasFootnote 26. It concluded that data on ACT use for treatment of clinical uncomplicated malaria in the second and third trimester of pregnancy indicate that they are safe in terms of pregnancy outcomes. The same report suggested that ACT exposure in the first trimester of pregnancy did not increase the risk of miscarriage, stillbirths or major congenital malformations compared to quinine, and based on the available updated evidence, the first-line treatment of uncomplicated malaria in the first trimester of pregnancy could be revised to include ACTs as a therapeutic option. Most of the data of artemisinin exposure in the first trimester of pregnancy are from artemether-lumefantrine exposure; consequently, more safety data are needed with other ACTsFootnote 26. In a study conducted in Thailand, malaria and pregnancy had no effect on pharmacokinetics of IV artesunate, but both had opposite effects on oral bioavailability of artesunate, resulting in a net decrease of 25% in oral bioavailabilityFootnote 27. The authors conclude that further study of dose optimization is required. In light of these findings, close monitoring is recommended, as an extension of time to treat may be required.

The quality of artemisinin derivatives available in developing countries may be questionable, as they may not be produced in accordance with the good manufacturing production standards required in North America, or they may be counterfeitFootnote 28 (see Chapter 5, section on counterfeit drugs in “Preventing Malaria in the Long-Term Traveller or Expatriate”).

In recent years, non-pharmaceutical grade products made from Artemisia plant material including tablets and capsules have gained popularity, particularly in countries where there is limited access to pharmaceutical grade artemisinin and its derivatives. The WHO does not support the use of non-pharmaceutical forms of Artemisia for the prevention or treatment of malaria.

Table 8.1: Recommendations for Artemisinin and derivatives

Artemether in combination with lumefantrine (Riamet® in Europe, Coartem® in Africa and the U.S.) is widely distributed in Africa for the treatment of P. falciparum malaria. A 6-dose regimen of artemether–lumefantrine appears more effective than some antimalarial regimens not containing artemisinin derivativesFootnote 10Footnote 11.

Parenteral artesunate is recommended as the first-line treatment of severe P. falciparum malariaFootnote 12, and can be used during all trimesters of pregnancy. Parenteral administration of artesunate should be followed by a full complete course of appropriate oral therapy. See Chapter 7, treatment of severe malaria.

On the basis of their short half-life, artemisinin compounds should not be used for chemoprophylaxis.

ABBREVIATIONS: ACT, artemisinin-based combination therapy; P, Plasmodium.

Atovaquone-proguanil

Trade Names: Malarone®, Malarone Pediatric®, Atovaquone Proguanil, Mylan-Atovaquone/Proguanil, Teva-Atovaquone Proguanil

Atovaquone-proguanil is licensed in Canada for malaria chemoprophylaxis in adults and in children weighing 11 kg and above, and for treatment of uncomplicated malaria in adults and in children weighing 11 kg and aboveFootnote 29 (see Chapter 5 for dosage in children weighing between 5 and 11 kg). Two formulations of Malarone® are available: Malarone® tablets containing 250 mg of atovaquone and 100 mg proguanil hydrochloride, and Malarone® pediatric tablets, containing 62.5 mg atovaquone and 25 mg proguanil hydrochlorideFootnote 29.

Mechanism of action

Atovaquone-proguanil is a fixed drug combination of atovaquone and proguanil in a single tablet. The two components are synergistic, inhibiting electron transport and collapsing mitochondrial membrane potential. Atovaquone-proguanil is effective as a causal (acting at the liver stage) as well as a suppressive (acting at the blood stage) prophylactic agent. Atovaquone-proguanil must be taken daily, and it is essential that it be taken with a fatty meal - due to poor oral absorption otherwise, with associated diminished efficacy. Because of its causal effects, atovaquone-proguanil can be discontinued one week after departure from a malaria-endemic area. The elimination half-life of atovaquone-proguanil is 2 to 3 days in healthy adults, but only 1 to 2 days in children aged 6 to 12 yearsFootnote 29. There are limited off-label data available that show that shorter prophylaxis courses with atovaquone-proguanil may be effectiveFootnote 30Footnote 31.

Indications and efficacy

For malaria chemoprophylaxis, atovaquone-proguanil is as effective (96%–100%) in the non-immune traveller as doxycycline and mefloquine against chloroquine-resistant falciparum malariaFootnote 32Footnote 33. It is also effective along the borders of Thailand, where chloroquine and mefloquine resistance is documentedFootnote 34Footnote 35. Daily atovaquone-proguanil taken with fatty food can now be considered as first-line chemoprophylaxis in areas with multidrug-resistant falciparum malaria (with attention to contraindications and precautions) (see Appendix I)Footnote 34Footnote 36.

In clinical trials of treatment of acute, uncomplicated P. falciparum malaria conducted in southeast Asia, South America and Africa, the efficacy of the combination of atovaquone-proguanil (dosed once daily for three days) exceeded 94%Footnote 37. In addition, published case reports have documented that it successfully treated multidrug-resistant malaria that failed to respond to other therapiesFootnote 32. Being an effective and well-tolerated therapy, atovaquone-proguanil is considered first-line treatment of uncomplicated P. falciparum infection, including multidrug-resistant P. falciparumFootnote 37, provided that it was not used as chemoprophylaxis during travel.

There have been sporadic documented cases of atovaquone-proguanil clinical treatmentFootnote 33Footnote 38Footnote 39Footnote 40Footnote 41Footnote 42Footnote 43Footnote 44Footnote 45 and prophylaxis failuresFootnote 46, some of which have been related to atovaquone-proguanil-resistant P. falciparum malaria acquired in sub-Saharan AfricaFootnote 38Footnote 39Footnote 40Footnote 41Footnote 42Footnote 43. Other clinical failures of atovaquone-proguanil have been clearly linked to sub-therapeutic serum levels following administration of the drug without fatty foodFootnote 46, while others are suggestive of such drug malabsorption due to an absence of genetic markers of resistance in the causative P. falciparum isolateFootnote 40Footnote 44Footnote 45. It is the anecdotal experience of members of CMN that treatment failures of atovaquone-proguanil due to malabsorption, not drug resistance, are becoming increasingly common due to a failure by practitioners and pharmacists to prescribe the drug to be taken with fatty food. Thus, it is imperative to reiterate the importance of co-administration of drug with fatty food to nursing and medical staff managing patients who are being treated with atovaquone-proguanil for uncomplicated malaria.

There is insufficient evidence at this time to recommend atovaquone-proguanil for the routine treatment of non-falciparum malaria, although limited trial data suggest efficacy for the treatment of P. vivax malaria when atovaquone-proguanil is combined with primaquine (primaquine treatment should overlap with the three days of treatment with atovaquone-proguanil)Footnote 47Footnote 48Footnote 49. In clinical cases when there is a possibility of P. falciparum infection and P. vivax cannot be definitively confirmed, atovaquone- proguanil can be used for initial treatment. There is more danger to incorrectly treating chloroquine- resistant P. falciparum than treating with atovaquone-proguanil that is ultimately confirmed not to have been required.

Adverse effects, contraindications and precautions

At prophylactic doses, the most frequently cited adverse drug reactions are gastrointestinal reactions (e.g. nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea) and headache. In four of six placebo-controlled trials evaluating the safety and tolerability of atovaquone-proguanil prophylaxis, there was no difference between atovaquone-proguanil and placebo arms with respect to adverse drug reactionsFootnote 33.

During treatment, the most frequent adverse events are also those associated with the gastrointestinal tract: approximately 8% to 15% of adults and children experience nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain or diarrheaFootnote 29, and 5% to 10% develop transient, asymptomatic elevations in transaminase and amylase levelsFootnote 33. Serious adverse events associated with atovaquone-proguanil, such as seizures, hepatitis and rash (including Stevens-Johnson syndrome), are rare, as are adverse drug reactions that limit treatment. Atovaquone has been associated with fever and rash in HIV-infected people, requiring discontinuation of therapy, and has been shown to be teratogenic in rabbits but not in rat models (US Food and Drug Administration category C drug). Atovaquone increases the plasma concentration of zidovudine (AZT) and lowers serum levels of azithromycin. Coadministration of efavirenz with Malarone resulted in a decrease in exposures to atovaquone and proguanil. When given with efavirenz or boosted protease-inhibitors, atovaquone concentrations have been observed to decrease as much as 75%Footnote 29. Proguanil is well tolerated; although oral aphthous ulcerations are not uncommon, they are rarely severe enough to warrant discontinuing this medication. Proguanil may potentiate the anticoagulant effect of warfarin and similar anticoagulants (those metabolized by CYP 2C9) through possible interference with metabolic pathwaysFootnote 50.

Severe renal insufficiency (creatinine clearance < 30 mL/min) and hypersensitivity to either component is a contraindication to atovaquone-proguanil use. Atovaquone-proguanil is also contraindicated during pregnancy due to a lack of available safety data. A cohort study evaluated the risk of major birth defects among children born to pregnant travellers who were exposed to atovaquone-proguanil during the first trimesterFootnote 51. Atovaquone-proguanil exposure during any of the first 12 weeks of pregnancy was not associated with increased risk of any major birth defectFootnote 51. Three small published trials have reported on the safety and efficacy of atovaquone-proguanil used in conjunction with artesunate for rescue therapy in cases of multidrug-resistant P. falciparum infection in pregnant womenFootnote 52Footnote 53Footnote 54. There were no serious adverse drug events, and adverse drug reactions that were mild-to-moderate in nature were similar between comparator groups. There was no excess risk of prematurity, intrauterine growth retardation, low birth weight or congenital anomalies attributable to atovaquone-proguanil useFootnote 52Footnote 53Footnote 54. Thus, preliminary data suggest that atovaquone- proguanil appears to be safe, well tolerated and of no increased toxicity to the fetus in pregnant women being prophylaxed or treated for malaria. Additional data will be required before atovaquone-proguanil use in pregnancy is no longer contraindicated.

It is unknown whether atovaquone is excreted in human breast milkFootnote 33. Proguanil is excreted in small quantities. Thus, the use of atovaquone-proguanil in nursing women is recommended only if the infant weighs more than 5 kgFootnote 33.

Table 8.2: Recommendations for Atovaquone-proguanil

ATQ–PG prophylaxis has high-level efficacy (96%–100%) against chloroquine-resistant falciparum malaria Footnote 32Footnote 33.

Daily ATQ–PG can now be considered as first-line chemoprophylaxis in areas with multidrug-resistant falciparum malariaFootnote 32Footnote 35.

ATQ–PG is considered a first-line treatment for acute, uncomplicated P. falciparum malaria from southeast Asia, South America and Africa with an efficacy of ~ 94%Footnote 32Footnote 36.

There is insufficient evidence at this time to recommend ATQ–PG for the routine treatment of non-falciparum malaria, although it remains a reasonable option when standard therapy (eg. chloroquine) cannot be usedFootnote 33Footnote 47Footnote 48Footnote 49.

ABBREVIATIONS: ATQ-PG, atovaquone-proguanil; P, Plasmodium.

Chloroquine (or hydroxychloroquine)

Trade Names: Apo-Hydroxyquine, Mint-Hydroxychloroquine, Mylan-Hydroxychloroquine, Plaquenil®, Pro-Hydroxychloroquine, Teva-Chloroquine

Mechanism of action

Chloroquine is a synthetic 4-aminoquinoline, which acts against the intra-erythrocytic stage of parasite development. Chloroquine accumulates in the digestive vacuole of the Plasmodium parasite, where it binds haematin, leading to toxic metabolite formation within the digestive vacuole and damage to the plasmodial membranes. Hydroxychloroquine can be used if chloroquine not available or if the patient is already on hydroxychloroquine for another reason.

Indications and efficacy

Chloroquine (or hydroxychloroquine), taken once weekly, is effective for malaria prevention in areas with chloroquine-sensitive malaria and it remains the drug of choice for malaria chemoprophylaxis

in areas with chloroquine-sensitive malaria. Chloroquine is the drug of choice for the treatment of chloroquine-sensitive falciparum malaria, chloroquine-sensitive P. vivax, as well as P. ovale, P. malariae and P. knowlesi infectionsFootnote 55. P. vivax and P. ovale infections also require treatment of the hypnozoite forms that remain dormant in the liver and can cause a relapsing infection – see section on Primaquine below.

Chloroquine is suitable for people of all ages and for pregnant women. There is insufficient drug excreted in breast milk to protect a breast-feeding infant, and therefore nursing infants should be given chloroquine (adjusted for changing weight, see Table 8.11). Since overdoses are frequently fatal, instructions for childhood doses should be carefully followed, and the medication should be kept out of the reach of children.

Weekly chloroquine plus daily proguanil (Savarine® not available in Canada) is significantly less efficacious than atovaquone-proguanil, doxycycline or mefloquine and is not routinely recommended for prevention of malaria for Canadian travellers going to sub-Saharan Africa because of the high risk of chloroquine-resistant P. falciparum malariaFootnote 32Footnote 56.

Adverse effects, contraindications and precautions

Except for its bitter taste, chloroquine is generally well tolerated; most of its adverse effects are mild and self-limitingFootnote 57Footnote 58. Taking the drug with food may reduce other mild adverse effects, such as nausea and headache. Black-skinned people may experience generalized pruritus, which is not indicative of drug allergy. Lack of compliance due to pruritus may account for therapeutic failures associated with the use of chloroquine. Transient, minor visual blurring may occur initially but should not be a reason to discontinue chloroquine. Retinal toxicity is of concern when a cumulative dose of 100 g of chloroquine is reached. Anyone who has taken 300 mg of chloroquine weekly for more than five years and requires further prophylaxis should be screened twice-yearly for early retinal changesFootnote 36. Chloroquine may worsen psoriasis and, rarely, is associated with seizures and psychosis. It should not be used in individuals with a history of epilepsy or generalized psoriasisFootnote 15Footnote 36. Concurrent use of chloroquine interferes with antibody response to intradermal human diploid cell rabies vaccine.

Table 8.3: Recommendations for Chloroquine (or hydroxychloroquine)

Chloroquine (hydroxychloroquine), taken once weekly, is effective for malaria prevention in areas with chloroquine-sensitive malariaFootnote 55.

Chloroquine is the drug of choice for the treatment of malaria caused by chloroquine-sensitive P. falciparum and P. vivax, and all P. ovale, P. malariae and P. knowlesi infectionsFootnote 55.

Weekly prophylaxis with chloroquine plus daily proguanil (Savarine®) is significantly less efficacious than ATQ–PG, doxycycline or mefloquine and is NOT recommended for travellers Footnote 32Footnote 56.

Chloroquine should not be used in individuals with a history of epilepsy or generalized psoriasisFootnote 15Footnote 36.

ABBREVIATIONS: ATQ-PG, atovaquone-proguanil; P, Plasmodium.

Clindamycin

Trade Names: Dalacin C®, Apo-Clindamycin, Auro-Clindamycin, Clindamycine, Mylan-Clindamycin, Riva-Clindamycin, Teva-Clindamycin,

Mechanism of action

Clindamycin is an antimicrobial that inhibits the parasite’s apicoplast.

Indications and efficacy

Clindamycin is indicated only for the treatment of malaria and only in restricted circumstances. Clindamycin, although less effective than doxycycline or atovaquone-proguanil, is used in combination with quinine for those unable to tolerate or who have contraindications to the use of first-line agents (e.g. pregnant women and young children).

Adverse effects, contraindications and precautions

The most frequent adverse events with clindamycin are diarrhea and rash. Clostridium difficile infection, including pseudomembranous colitis, has been reported.

Table 8.4: Recommendations for Clindamycin

Clindamycin combined with quinine is recommended as treatment of chloroquine- or mefloquine-resistant P. falciparum malaria in pregnant women, children (< 8 years of age) and tetracycline-intolerant adultsFootnote 47 when artemisinin-derivatives (e.g. artesunate) are unavailable or atovaquone-proguanil cannot be used.

ABBREVIATIONS: P, Plasmodium.

Doxycycline

Trade Names: Apo-Doxy, Doxycin, Doxytab, Teva-Doxycycline

Mechanism of action

Doxycycline is an antimicrobial that inhibits parasite protein synthesis.

Indications and efficacy

Doxycycline is effective for the prevention and treatment of chloroquine-resistant P. falciparum.

It has been shown to be as effective as atovaquone-proguanil and mefloquine for the prevention of chloroquine-resistant P. falciparumFootnote 36. Doxycycline is an efficacious chemoprophylactic agent against mefloquine-sensitive and mefloquine-resistant P. falciparum malariaFootnote 36 but must be taken daily for it to work, and for four weeks after leaving the malaria-endemic area. The major reason for doxycycline failures is noncompliance with this daily regimen.

Travellers taking minocycline for the treatment of acne or rheumatoid arthritis and for whom doxycycline was recommended for malaria chemoprophylaxis should switch to doxycycline 100 mg daily the day before arrival in the malaria-endemic area. Once they have completed their anti-malarial chemoprophylaxis (including the 4 weeks of doxycycline chemoprophylaxis after leaving the malaria-endemic area), they should resume their former dose of minocycline. Travellers should use an effective sunscreen, especially since the dose of doxycycline used for malaria chemoprophylaxis may be higher than the minocycline dose used in the treatment of acne. Note that the preponderance of literature on efficacy of tetracyclines as antimalarials has focused on doxycyclineFootnote 59 and that insufficient data exist on the antimalarial prophylaxis efficacy of minocycline.

Adverse effects, contraindications and precautions

Doxycycline can cause gastrointestinal upset and, rarely, esophageal ulceration or esophagitis. These effects are less likely to occur if the drug is taken with food and large amounts of fluid. Absorption of doxycycline may be reduced if taken with dairy products. For this reason, pharmacies may advise taking doxycycline on an empty stomach. However, as noted above, this strategy is far more likely to cause gastrointestinal upset and compromise compliance. Patients should be instructed to ingest the drug with fluids or small amounts of food to mitigate gastrointestinal side effects. In randomized controlled trials of doxycycline at prophylactic doses, nausea and abdominal pain were the most commonly reported mild to moderate adverse eventsFootnote 59. Avoid taking doxycycline in the 30 minutes before lying down or with Pepto-Bismol® or antacids. Because doxycycline is photosensitizing, it may cause the skin to burn more easily; using a sunscreen that blocks ultraviolet A and B rays may reduce this problemFootnote 59. Doxycycline may also increase the risk of vaginal candidiasis, so women should carry antifungal therapy for self-treatment of vaginal candidiasis. Although tetracyclines and other antibiotics have been cited as a cause of oral contraceptive failure, evidence fails to demonstrate any significant associationFootnote 59Footnote 60. Concurrent use of doxycycline with barbiturates, carbamazapine or phenytoin may result in a 50% decrease in doxycycline serum concentration because of induction of hepatic microsomal enzyme activity and reduction of the half-life of doxycycline. There is a theoretical risk of reduced effectiveness of the oral typhoid vaccine (Ty21a) if given concurrently with doxycycline. Doxycycline should therefore not be used within 3 days of Ty21a vaccine administrationFootnote 59. Doxycycline and other tetracyclines are associated with benign intracranial hypertension, which can result in visual disturbances and rarely in permanent visual impairmentFootnote 61.

Doxycycline is contraindicated for pregnant women particularly after the 4th month of pregnancyFootnote 62, breastfeeding women, and historically doxycycline was also contraindicated in children aged less than 8 years. However, there are now data to suggest that doxycycline may be considered for treatment of malaria in children less than 8 years when there are no other alternative optionsFootnote 63. The American Academy of Pediatrics now states that doxycycline can be used for short durations (21 days or less) regardless of patient ageFootnote 64. Doxycycline has been taken safely in prophylactic doses for at least 12 months, and tetracycline derivatives have been used at lower doses over many years for skin disorders such as acne.

Table 8.5: Recommendations for Doxycycline

Doxycycline has high level efficacy (93%–100%) for the prevention of chloroquine-resistant P. falciparum and for mefloquine-resistant P. falciparumFootnote 59.

Travellers should be informed about the small doxycycline-associated risks of esophageal ulceration, vaginal candidiasis and photosensitivity.

Doxycycline is contraindicated during pregnancy, while breastfeeding and generally in children < 8 years of age unless there are no other treatment options. Note that doxycycline can be administered for short durations (21 days or less) regardless of patient age.

Concurrent use of doxycycline with barbiturates, carbamazapine or phenytoin may result in a 50% decrease in doxycycline serum concentration.

People taking minocycline for the treatment of acne or rheumatoid arthritis should switch to doxycycline 100 mg daily for the duration of their stay in the malaria-endemic area plus for four weeks after leaving the area, then switch back to their usual dose of minocycline.

ABBREVIATIONS: P, Plasmodium.

Mefloquine

Trade Name: Mefloquine

Mechanism of action

Mefloquine is a fluorinated quinoline. It is a lipophilic drug that acts on the intra-erythrocytic asexual stages of parasite development, inhibiting heme polymerization within the food vacuole.

Indications and efficacy

Mefloquine is an effective chemoprophylactic and therapeutic agent against drug-resistant

P. falciparum. In Canada, it is routinely recommended only for chemoprophylaxis. CATMAT does not routinely recommend mefloquine for the treatment of malaria, because it is less well tolerated at treatment doses (25 mg base/kg). Severe neuropsychiatric reactions are reported to be 10 to 60 times more frequent, occurring in 1/215 to 1/1,700 users of treatment doses of mefloquineFootnote 15.

For the prevention of chloroquine-resistant malaria, mefloquine is one of several options, along with atovaquone-proguanil, doxycycline or primaquineFootnote 65. The chemoprophylactic efficacy of mefloquine is generally greater than 90%Footnote 66 except for multidrug-resistant areas including some border areas of Thailand with Myanmar (Burma), Laos and Cambodia, also southern Vietnam and the southwest borders of China. Mefloquine is a suppressive chemoprophylactic agent and must be taken for four weeks after departure from a malaria-endemic area.

In order to assess mefloquine tolerance in those without contraindications (see below), it is recommended to start mefloquine chemoprophylaxis at least 2 weeks, and preferably 3 weeks, before arrival in an endemic area. This strategy allows the traveller time to contact the prescribing physician to arrange an alternative antimalarial if needed. Alternatively, data from several trials indicate that mefloquine taken once daily for three days before travel (loading dose) followed by a once weekly dose is relatively well-tolerated and an effective way to rapidly achieve therapeutic blood levels (reaching steady state levels in four days compared with seven to nine weeks with standard weekly dosing of mefloquine)Footnote 67. In controlled studies, only about 2% to 3% of loading dose recipients discontinued mefloquine, and most of these did so during the first week.

There is no evidence that toxic metabolites of mefloquine accumulate, and long-term prophylactic use of mefloquine (> 1 year) by Peace Corps volunteers in Africa was not associated with additional adverse effectsFootnote 56. It is recommended, therefore, that the duration of mefloquine use not be arbitrarily restricted in individuals who tolerate this medication.

Adverse effects, contraindications and precautions

The profile of mefloquine adverse events is characterized by a predominance of neuropsychiatric reactionsFootnote 68; controlled studies have shown a significant excess of neuropsychiatric events in mefloquine users versus comparatorsFootnote 66. The mefloquine Product MonographFootnote 69 now contains a Contraindications checklist and a Serious Warnings and Precautions Box to remind prescribers that:

- Mefloquine should not be prescribed to patients with major psychiatric disorders.

- Mefloquine may cause neuropsychiatric adverse reactions that can persist after mefloquine has been discontinued.

- During prophylactic use, if psychiatric or neurologic symptoms occur, mefloquine should be discontinued and an alternative medication should be substituted.

The most frequent adverse effects reported with mefloquine use are nausea, strange vivid dreams, dizziness, mood changes, insomnia, headache and diarrhea; most of these are mild and self-limitingFootnote 57Footnote 58. Serious but rare adverse drug reactions include psychiatric (psychosis, hallucinations) and neurologic (seizures, severe vertigo and/or tinnitus, peripheral neuropathy) events, agranulocytosis, aplastic anemia, and hepatic impairment including hepatic failureFootnote 69. A recent systematic review found that mefloquine users were more likely to discontinue their medication due to adverse events than atovaquone-proguanil users, but there was no difference in discontinuation when compared to those taking doxycyclineFootnote 68. Tens of millions of travellers have used mefloquine chemoprophylaxis, and severe neuropsychiatric reactions (seizure, psychosis) to this drug are rare (1 in 10,600) when used at prophylactic dosesFootnote 70. The frequency of serious adverse effects from mefloquine was found not to differ from atovaquone-proguanil or doxycycline, when the drugs were compared in a systematic reviewFootnote 68. Occasionally, a traveller (in particular, womenFootnote 15Footnote 71 and people with low body weightFootnote 66, will experience less severe but still troublesome neuropsychiatric reactions (e.g. anxiety, mood change) with mefloquine prophylaxis (1 in 250 to 500 users), requiring a change to another drug. This can sometimes be prevented by splitting the weekly dose of one tablet into two halves, taken twice a week for the same total weekly dose.

Adverse reactions are generally reversible, but because of the long half-life of mefloquine, adverse reactions to mefloquine may occur or persist up to several months after discontinuation of the drug. In a small number of patients it has been reported that depression, dizziness or vertigo and loss of balance may continue for months after discontinuation of mefloquine, and permanent vestibular damage has been seen in some casesFootnote 69Footnote 72. Rare cases of suicidal ideation and suicide have been reportedFootnote 69.

When mefloquine is prescribed for prophylactic use, individuals should be advised that if they experience neuropsychiatric symptoms, such as acute anxiety, depression, restlessness or confusion, or severe dizziness, tinnitus, vertigo, or symptoms of a peripheral neuropathy, these may be prodromal to more serious adverse events. They should report these adverse events immediately, discontinue the drug, and substitute it with another medication.

Contraindications to mefloquine use include known hypersensitivity or past severe reaction to mefloquine; history of serious psychiatric disorder (e.g. psychosis, severe depression, generalized anxiety disorder, schizophrenia or other major psychiatric disorders); and seizure disorder.

Caution should be exercised when prescribing mefloquine in the following situations:

- Children smaller than 5 kg since experience with mefloquine in infants less than 3 months old or weighing less than 5 kg is limited, and the tablet cannot be accurately subdivided and may need to be specially compoundedFootnote 69.

- Use in those with occupations requiring fine coordination or activities in which vertigo may be life-threatening, such as flying an aircraft.

- Concurrent use of chloroquine or quinine-like drugs (due to the risk of a potentially fatal prolongation of the QT interval), for example halofantrine and mefloquine should not be used concurrently, (see section on halofantrine below).

- Underlying cardiac disease, cardiac conduction disturbances or arrhythmia. There are safety concerns regarding the co-administration of mefloquine and agents known to alter cardiac conduction, including other related antimalarial compounds (quinine, quinidine, chloroquine), beta-blockers, calcium channel blockers, phenothiazines, antihistamines and tricyclic antidepressants because these drugs may contribute to a prolongation of the QT intervalFootnote 73. At present the concurrent use of these agents is not contraindicated, but caution should be exercised in prescribing mefloquine in these situations and use should be monitored.

- First trimester of pregnancy. Data from published studies in pregnant women have shown no increase in the risk of teratogenic effects or adverse pregnancy outcomes following mefloquine treatment or prophylaxis during pregnancyFootnote 69. WHO states that if travel during the first trimester of pregnancy is absolutely essential, then because of the danger of malaria to the mother and fetus, effective preventive measures should be taken, including prophylaxis with mefloquine where this is indicatedFootnote 36. The use of mefloquine to prevent malaria in pregnant women should be based on an individual risk-benefit analysis of adverse effects (including dizziness and nausea) versus the risk of a pregnant woman acquiring malaria infection, with the understanding that the safety of mefloquine in pregnancy is controversial and a continuing subject of debateFootnote 74 (See Chapter 5; section 5.2).

Mefloquine is extensively metabolized in the liver by CYP3A4; caution should therefore be exercised when mefloquine is administered concomitantly with CYP3A4 inhibitors such as ketoconazole or macrolide antimicrobials because this can result in toxic levels of mefloquineFootnote 66. Co-administration with CYP3A4 inducers (eg. anticonvulsants, barbiturates, St. John’s wort, some NNRTIs, rifampicin, rifabutin) may result in subtherapeutic levels of mefloquine and mefloquine failures. In addition, mefloquine is a substrate and an inhibitor of P-glycoprotein. Therefore drug-drug interactions could also occur with drugs that are PGP substrates or are known to modify the expression of this transporterFootnote 69.

Insufficient mefloquine is excreted in breast milk to protect a nursing infant. Although the package insert recommends that mefloquine not be given to children weighing less than 5 kg, it should be considered for children at high risk of acquiring chloroquine-resistant P. falciparum malaria (see Chapter 4; Chapter 5; Appendix I). There are no pharmacokinetic data upon which to recommend a correct dose for children weighing less than 15 kg. WHO has suggested a chemosuppressive dose of 5 mg base/kg weekly for children weighing more than 5 kg. Uncertainty in the dosing for small infants must be weighed against the risk of malaria.

Table 8.6: Recommendations for Mefloquine

If tolerated, mefloquine is one of several options (along with atovaquone–proguanil, doxycycline or primaquine), for the prevention of chloroquine-resistant malariaFootnote 65.

Mefloquine is not recommended for prevention of malaria in border areas between Cambodia, Myanmar, Laos and Thailand, as well as southern Vietnam and the southwest borders of China due to reports of treatment failures in excess of 50% in those areasFootnote 36.

Long-term use of mefloquine (> 1 year) in Africa is not associated with additional adverse effects, and its use should not be arbitrarily restricted in individuals who tolerate this medicationFootnote 15.

When mefloquine is prescribed for prophylactic use, individuals should be advised that if they experience neuropsychiatric symptoms, they should report these adverse events immediately, discontinue the drug, and substitute it with another medication.

Mefloquine is not recommended as a treatment for malaria. With doses used for treatment, severe neuropsychiatric reactions are reported to occur in 1/215 to 1/1,700 usersFootnote 15.

Mefloquine is contraindicated in individuals with known mefloquine hypersensitivity, past severe reaction to mefloquine, a history of serious psychiatric disorder (e.g. psychosis, severe depression, generalized anxiety disorder, schizophrenia or other major psychiatric disorders), seizure disorder and cardiac conduction delaysFootnote 15.

Primaquine

Trade Name: Primaquine (primaquine phosphate)

Mechanism of action

Primaquine is an 8-aminoquinoline antimalarial that is active against multiple life cycle stages of the plasmodia that infect humans; it has been used for over 50 years. Its mechanism of action is not fully understood. However, primaquine is active against the developing liver stages (causal effect), thereby preventing establishment of infection; against liver hypnozoites, preventing relapses in established P. vivax and P. ovale infections; against blood stages; and against gametocytes, thereby preventing transmission.

Indications and efficacy

Primaquine is used in three major ways to prevent malaria: 1) as a primary chemoprophylactic agent: 2) for prevention of relapse due to liver stages of P. vivax or P. ovale infection (primaquine anti-relapse therapy [PART]): 3) in the treatment regimen of confirmed bloodstream infections with P.vivax or P.ovale infection as radical cure to prevent relapse. See adverse effects section for information on the need to test for glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) levels prior to use of primaquine.

- Primary chemoprophylaxis: Primaquine is an effective chemoprophylactic agent against both P. falciparum and P. vivax malariaFootnote 65. Studies have shown efficacy in semi-immune and nonimmune subjects, although data for varied geographic regions are limited. Given at a dose of 0.5 mg/kg base per day (adult dose 30 mg base per day) for 11 to 50 weeks, primaquine had a protective efficacy of 85% to 94% against both P. falciparum and P. vivax infectionsFootnote 75. Primaquine is well tolerated in people who are not G6PD deficient. Because of the causal effects of primaquine, it can be discontinued one week after departure from a malaria-endemic area. All travelers need to be evaluated for G6PD deficiency before primaquine is initiated. Although not a first-line chemoprophylactic agent, primaquine may be considered an alternative chemoprophylactic agent (with attention to contraindications and precautions) for those without G6PD deficiency when other regimens are either inappropriate or contraindicated.

- Primaquine anti-relapse therapy (PART): P. vivax and P. ovale parasites can persist in the liver and cause relapses for as long as five years after departure from a malaria-endemic area. Since most malarial areas of the world (except Haiti and the Dominican Republic) have at least one species of relapsing malaria, travellers to these areas have some risk of acquiring either P. vivax or P. ovale, although actual risk for an individual traveller is difficult to define. Primaquine decreases the risk of relapses by acting against the liver stages of P. vivax and P. ovale. There are currently only two drugs available in Canada which act on the liver stage: atovaquone-proguanil and primaquine. Only primaquine has cidal activity against the hypnozoites, and therefore only primaquine is effective against late vivax and ovale infection. None of the other currently recommended chemoprophylaxis regimens will prevent relapses due to P. vivax and P. ovale. Primaquine terminal prophylaxis is administered after the traveller has left a malaria-endemic area, usually during the last two weeks of chemoprophylaxis with doxycycline or mefloquine, or last week of prophylaxis with atovaquone-proguanil. Terminal prophylaxis with primaquine is generally indicated only for people who have had prolonged exposure in malaria-endemic regions (e.g. long-term travellers or expatriates)Footnote 76. PART should therefore be considered in travellers who have lived for 6 months or longer in a high-risk area or who have likely experienced intense exposure to P. vivax, such as in areas of the Omo River (Ethiopia) and Papua New GuineaFootnote 76.

- Radical Cure: Primaquine is also indicated as part of the treatment of confirmed bloodstream infection with P. vivax or P. ovale. In order to reduce the risk of relapse following the treatment of symptomatic P. vivax or P. ovale infection, primaquine is indicated to provide “radical cure.” Primaquine should be initiated for radical cure after the acute febrile illness is over, but to overlap with the blood schizonticide (i.e. chloroquine, atovaquone-proguanil, or quinine). P. vivax isolates with a decreased responsiveness to primaquine are well documented in southeast Asia and, in particular, Papua New Guinea and Papua (Irian Jaya). On the basis of increasing numbers of reports of resistance to primaquine at the standard dose of 0.25 mg/kg, the WHO recommends a higher dose (0.5 mg base/kg by weight) for radical cure for patients who acquired relapsing malaria in Oceania and southeast AsiaFootnote 2. To avoid any potential under dosing, CATMAT recommends the use of 30 mg base (52.6 mg salt) daily x 14 days as the standard adult dose (0.5 mg/kg) regardless of geographic area of malaria acquisition. For pediatric patients, dose is by weight, to a maximum of 30 mg base daily (See Table 8.11). This higher dose recommendation is consistent with malaria treatment guidelines published by the United KingdomFootnote 77 and from the CDC in the United StatesFootnote 55. In Canada primaquine is marketed as 26.3 mg salt (equivalent to 15 mg base) (Table 8.10)Footnote 78. There is often confusion in dispensing this medication. To avoid having patients under dosed, ensure prescription is clear that a 30 mg base is 2 tablets daily, for 14 days.

Adverse effects, contraindications and precautions

Primaquine is generally well tolerated but may cause nausea and abdominal pain, which can be decreased by taking the drug with food. More importantly, primaquine may cause methemoglobinemia and oxidant-induced hemolytic anemia, particularly among individuals with G6PD deficiency, which is more common in those of Mediterranean, African and Asian ethnic origin. Four classes of G6PD deficiency exist and are classified based on the level of residual enzyme activity in red blood cells, with Class I being the most severe form, and Classes II to IV having diminishing degrees of deficiency. Most people with G6PD deficiency will have a moderate variant, with more than 10% residual G6PD red cell activity. As well, those receiving more than 15 mg base/day have a greater risk of hemolysis. Therefore, all individuals should have their G6PD level measured before primaquine therapy is initiated.

Primaquine is contraindicated in people with severe G6PD deficiencies. In mild variants of G6PD deficiency, primaquine has been used safely at a lower dose for radical cure to prevent P. vivax and P. ovale relapses (0.8 mg base/kg weekly; adult dose 45 mg base weekly for 8 weeks); however, this reduced dose is insufficient for chemoprophylactic activity. Administering primaquine less frequently (e.g. weekly rather than daily) and for longer (e.g. eight weeks versus standard two weeks) enables effective PART with minimal risk of hemolysis in those with less severe forms of G6PD deficiency. When used at prophylactic doses (0.5 mg base/kg daily) in children and adults with normal G6PD activity, mean methemoglobin rates (5.8%) were below those associated with toxicity (> 10%). Advise travellers to stop their medication and report to a physician immediately if jaundice, gray skin or abnormally dark or brown urine is noted.

Primaquine is contraindicated in pregnancy. P. vivax or P. ovale infections occurring during pregnancy should be treated with standard doses of chloroquine (Table 8.3). Relapses can be prevented by weekly chemoprophylaxis with chloroquine until after delivery, when primaquine can be safely used for mothers with normal G6PD levels. However, primaquine should only be used in nursing mothers if the infant has been tested and found not to be G6PD deficient.

Recently, genetic variants of CYP enzymes presumably responsible for metabolism of primaquine to active metabolites have been described. Primaqine may be ineffective in the presence of these polymorphisms, which can be present in 10% or more of some populationsFootnote 79Footnote 80. Detection of these polymorphisms can be performed in some research laboratories at this time, and these variants may account for some cases of what was presumed to be primaquine resistance.

In 2018, the U.S. FDA approved another 8-aminoquinoline, tafenoquine (Arakoda™; Krintafel™) for the prevention of all human malarial species, and specifically for relapse of P. vivax and P. ovale infections. Tafenoquine likely has a similar mechanism of action to primaquine, but has a longer half-life (14-days), which enables use of just a single dose of tafenoquine (Krintafel™) for radical cure or PART of relapsing strains of malaria. Like primaquine, G6PD testing is required before use, and the drug is contraindicated in pregnancy and lactation, as well as in those with psychosis. At this time, tafenoquine is neither licensed nor marketed in Canada, thus, it remains unavailable for routine prophylaxis or treatment.

Table 8.7: Recommendations for Primaquine

Screening for glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) levels is recommended, prior to use of primaquine.

Primaquine (30 mg base daily) is an effective chemoprophylactic agent with a protective efficacy of 85%–93% against both P. falciparum and P. vivax infections; it is recommended for prophylaxis against chloroquine-resistant P. falciparum infections when the first-line agents, mefloquine, doxycycline and ATQ–PG, cannot be used, and in the prophylaxis of P. vivax or P. ovale malaria. Patients must be screened for G6PD deficiencyFootnote 58Footnote 81.

Primaquine (30 mg base daily for 2 weeks) is used for terminal prophylaxis (PART) after the traveller has left a malaria-endemic area, usually during or after the last two weeks of chemoprophylaxis; generally indicated only for people who have had prolonged exposure in Vivax-endemic regions (e.g. long-term travellers or expatriates)Footnote 76.

Primaquine 30 mg base daily for 2 weeks is effective treatment as a radical cure of established infection with P. vivax or P. ovale. Primaquine should be initiated for radical cure after the acute febrile illness is over, but to overlap with the blood schizonticide treatment in order to prevent relapse of infectionFootnote 2Footnote 82

ABBREVIATIONS: ATQ-PG, atovaquone-proguanil; G6PD, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase; P. Plasmodium.

Quinine and quinidine

Oral Quinine Trade Names: Apo-Quinine, Jamp-Quinine, Pro-Quinine, Quinine-Odan, Quinine Sulfate, Teva-Quinine

Mechanism of action

Quinine and quinidine are quinoline-containing antimalarials. They are alkaloid derivatives of Cinchona bark and act on the intra-erythrocytic asexual stage of the parasite.

Indications and efficacy

Quinine and quinidine are indicated only for the treatment of malaria and not for prophylaxis. Quinine (or quinidine) should not be used alone: a second drug such as doxycycline or clindamycin should always be used concurrently.

Oral treatment with quinine is indicated for uncomplicated falciparum malaria and as step-down therapy after parenteral treatment of complicated malaria.

Quinine and artesunate are first-line drugs for the parenteral therapy of severe or complicated malaria, but artesunate has been shown to be the more effective treatment for severe malariaFootnote 12. The CMN recommends reserving the use artesunate for those presenting with WHO-defined severe malaria and using parenteral quinine in those whose indication is vomiting or intolerance to oral therapy. Because of the significant cardiotoxic effects associated with parenteral quinidine it is to be considered only if the two first-line drugs are unavailable; in that case cardiac monitoring is required.

Adverse effects, contraindications and precautions

Minor adverse events are common with quinine and quinidine use. These include cinchonism (tinnitus, nausea, headache, and blurred vision), hypoglycemia (especially in pregnant women and children), nausea and vomiting. Occasionally, hypersensitivity and nerve deafness have been reported. Parenteral quinidine has the potential to increase the QT interval and therefore requires electrocardiographic monitoring. Electrocardiographic monitoring should also be considered with use of parenteral quinine.

Table 8.8: Recommendations for Quinine

Oral therapy with quinine (with a second agent – doxycycline or clindamycin) is indicated for the treatment of uncomplicated falciparum malaria and as step-down therapy after parenteral treatment of complicated malariaFootnote 36Footnote 48.

Parenteral quinine is recommended for those without severe malaria who are unable to take oral therapy

Parenteral quinine is the alternative drug for the treatment of severe or complicated malaria when parenteral artesunate is unavailableFootnote 2.

Other Drugs not available or not routinely recommended in Canada (In Alphabetical Order)

It is important for travellers and providers to understand that the medical management of malaria in countries where the disease is endemic may differ significantly from management in Canada.

In countries where malaria is endemic, the number of effective medications available for treatment may be limited; indeed, some of the drugs used may be ineffective in nonimmune travellers or be associated with unacceptable adverse outcomes. In addition, drugs purchased locally may be counterfeitFootnote 83. As well, the level of health care available in some of these countries may put travellers at risk of other infectious diseases.

Amodiaquine is a 4-aminoquinoline that was first introduced as an alternative to chloroquine. Resistance to this drug has followed the path of chloroquine resistance. Bone marrow toxicity and hepatotoxicity have been noted when it is used for malaria prophylaxis. Amodiaquine is not recommended for malaria chemoprophylaxis.

Azithromycin (Zithromax®) is a macrolide antimicrobial that inhibits the parasite apicoplast. Azithromycin has been shown not to be very effective in the prevention of P. falciparum malaria. Studies performed to date indicate that azithromycin is less effective than atovaquone-proguanil, doxycycline, mefloquine or primaquineFootnote 33Footnote 59Footnote 76Footnote 84. There is insufficient evidence to recommend azithromycin as an alternative antimalarial except under circumstances in which other, more effective and safer, medications are not available or are contraindicated. The antimalarial effect of azithromycin may make detection of malaria infection more difficult and the empiric use of macrolide antibiotics for fever, prior to ruling out malaria, is discouraged.

Azithromycin is considered to be safe in pregnancy and for children and is available in suspension. However, in view of the serious consequences of malaria in pregnancy and in young children, use of this suboptimal antimalarial would not routinely be recommended.

Halofantrine is a phenanthrene methanol derivative related to mefloquine and quinine. It is available only in an oral formulation, which is limited by variable bioavailability. Halofantrine is not licensed in Canada and has been withdrawn from the world market because of concerns about cardiotoxicity. It does remain widely available in the tropics, and travellers should know of the danger of this drugFootnote 15Footnote 58. WHO has reported cardiac deaths associated with the use of halofantrine and no longer recommends its use.

Piperaquine is a bisquinoline antimalarial drug that was first synthesised in the 1960s and used extensively in China for malaria prophylaxis and treatment for about 20 years. With the development of piperaquine-resistant strains of P. falciparum and the emergence of the artemisinin derivatives, its use declined during the 1980s. However, in the 1990s, Chinese scientists rediscovered piperaquine as one of a number of compounds suitable for combination with an artemisinin derivative. Recent Indochinese studies have confirmed the excellent clinical efficacy of piperaquine-DHA combinations (28-day cure rates > 95%) and have demonstrated that currently recommended regimens are not associated with significant adverse effects. The pharmacokinetic properties of piperaquine have also been characterized recently, revealing that it is a highly lipid-soluble drug with a large volume of distribution at steady state, long elimination half-life and a clearance that is markedly higher in children than in adults. The tolerability, efficacy, pharmacokinetic profile and low cost of piperaquine make it a promising partner drug for use as part of artemisinin-based combination therapy (ACT)Footnote 85.

Proguanil should not be used as a single agent (e.g. Paludrine®), or in combination with chloroquine (Savarine®) for chemoprophylaxisFootnote 56Footnote 70Footnote 86Footnote 87. Further information is available for the combined product atovaquone-proguanil (Malarone®) above.

Pyrimethamine alone (Daraprim®) is not recommended for malaria chemoprophylaxis because of widespread drug resistance in Asia and AfricaFootnote 83 and evidence of some resistance in HaitiFootnote 88.

Pyrimethamine-sulfadoxine (Fansidar®) is a fixed drug combination antimetabolite that inhibits parasite folate synthesis. Historically, this drug has been used for treatment, including self-treatment, of P. falciparum, but increasing resistance means it has limited utility for the treatment of P. falciparum and is no longer recommended. Resistance has been reported in the Amazon Basin, southeast Asia, and increasingly throughout AfricaFootnote 89.

Pyrimethamine-sulfadoxine is not recommended by CATMAT, CDC or WHO for chemoprophylaxis because of the life-threatening complication of Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysisFootnote 15. It has been used, however, in parts of Africa for intermittent prophylactic treatment during pregnancy and sometimes in childhood.

Pyronaridine is a benzonaphthyridine synthesized in China in 1970 that has been used to treat

P. vivax and P. falciparum infections for more than 20 years and has been shown to effectively treat falciparum malaria in children in Cameroon. It has more gastrointestinal adverse effects than chloroquine. Pyronaridine has been used in combination with the artemisinin derivatives in the treatment of falciparum malariaFootnote 90.

Table 8.9: Recommendations for other drugs not available or not routinely recommended in Canada

Azithromycin has been shown not to be very effective in the prevention of P. falciparum malariaFootnote 33Footnote 59Footnote 76Footnote 84.

Amodiaquine is not recommended for malaria chemoprophylaxis because of its established risks of fatal hepatic and bone marrow toxicityFootnote 15Footnote 58Footnote 91.

Halofantrine has been associated with cardiac toxicity and should not be used as an antimalarialFootnote 15Footnote 58. Travellers should be forewarned, as it may still be available in some countries.

Piperaquine's tolerability, efficacy, pharmacokinetic profile and low cost make it a promising partner drug for use as part of an ACTFootnote 85.

Pyrimethamine alone (Daraprim®) is not recommended for malaria chemoprophylaxis because of widespread antifolate drug resistanceFootnote 83.

Proguanil should not be used as a single agent for chemoprophylaxis because of widespread drug resistanceFootnote 56Footnote 70Footnote 86Footnote 87.

Pyrimethamine–sulfadoxine (Fansidar®) is not recommended for chemoprophylaxis because of the life-threatening complication of Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysisFootnote 15.

Pyronaridine has received insufficient study to recommend its use for the treatment of malaria in nonimmune travellersFootnote 90.

Proguanil alone or in combination with chloroquine (Savarine®) is less effective than mefloquine, doxycycline and ATQ–PG and is not recommended for malaria prophylaxisFootnote 56Footnote 86Footnote 87Footnote 92.

ABBREVIATIONS: ART, artemisinin-based combination therapy; ATQ-PG, atovaquone-proguanil; P. Plasmodium.

Malaria Vaccines – Not available in Canada

Mosquirix, an antimalarial vaccine developed by GlaxoSmithKline in partnership with the PATH Malaria Vaccine Initiative, was given a positive scientific opinion in July 2015 by the European Medicines Agency for use outside the EU. Mosquirix is intended for use in areas where malaria is endemic, for the active immunization of children aged 6 weeks to 17 months against malaria caused by the Plasmodium falciparum parasite and against hepatitis B. After decades of research into malaria vaccinations, Mosquirix is the first vaccine for the disease to be assessed by a regulatory agencyFootnote 93.

| Drug | Base (mg) | Salt (mg) |

|---|---|---|

Chloroquine phosphate |

155.0 |

250.0 |

Chloroquine sulphateFootnote b |

100.0 |

136.0 |

Clindamycin hydrochloride |

150.0 |

225.0 |

Mefloquine |

250.0 |

274.0 |

Primaquine |

15.0 |

26.3 |

Quinidine gluconate |

5.0 |

8.0 |

7.5 |

12.0 |

|

10.0 |

16.0 |

|

15.0 |

24.0 |

|

Quinidine sulphateFootnote c |

7.5 |

9.0 |

10.0 |

12.0 |

|

15.0 |

18.0 |

|

Quinine dihydrochloride |

5.0 |

6.0 |

7.5 |

9.0 |

|

15.0 |

18.0 |

|

16.7 |

20.0 |

|

Quinine sulphate |

250.0 |

300.0 |

| Indication | Adult dosage | Pediatric dosage | Advantage | Disadvantage | Adverse effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

ATOVAQUONE–PROGUANIL (ATQ–PG) |

|||||

Prevention and |

Adult tablet: |

Pediatric tablets: |

Causal prophylaxis – only have to continue for 7 days after exposure |

Daily dosing for prophylaxis |

Frequent: |

ARTESUNATE |

|||||

Treatment of severe and complicated malaria |

Treatment:

|

Treatment:

|

Improved efficacy and faster response than parenteral quinine; no cardiovascular or hypoglycemic effects |

Requires concurrent therapy with second drug |

Frequent: |

CHLOROQUINE |

|||||

Prevention and treatment |

Prevention:

|

Prevention: Treatment: |

Long-term safety data for prophylaxis |

Most areas now report chloroquine resistance |

Frequent:

|

CLINDAMYCIN |

|||||

Alternative treatment |

Prevention: |

Prevention: |

Safe in pregnancy and |

Lower efficacy than |

Frequent: |

DOXYCYCLINE |

|||||

Prevention |

Prevention:100 mg once daily; start 1 day before entering malaria-endemic area and continue during exposure and for 4 weeks after leaving |

Prevention: Note that doxycycline can be administered for short durations (21 days or less) regardless of patient age. IV doxycycline is not licensed in Canada but available via Health Canada’s Special Access Program |

Protection against |

Daily dosing required for chemoprophylaxis |

Frequent: |

HYDROXYCHLOROQUINE |

|||||

Prevention and treatment |

Prevention: |

Prevention: 15–20 kg: ½ tablet Treatment: |

Long-term safety data for prophylaxis |

Most areas now report |

Frequent: |

MEFLOQUINE |

|||||

Prevention of |

Prevention: |

Prevention: |

Weekly dosing |

There are rare cases of severe intolerance to |

Frequent: |

PRIMAQUINE |

|||||

Prevention of |

Prevention: |

Prevention: |

Causal prophylaxis – only have to continue for 7 days after exposure |

Requires G6PD testing (see Chapter 4) |

Occasional: |

QUINIDINE |

|||||

|

Prevention: |

Prevention: |

|

Parenteral therapy |

Frequent: |

QUININE DIHYDROCHLORIDE |

|||||

|

Prevention: |

Prevention: |

|

|

Frequent: |

QUININE SULPHATE |

|||||

|

Prevention: |

Prevention: |

|

|

Similar to above |

Acknowledgements

This chapter was prepared by: McDonald P (lead), Boggild A, McCarthy A, and approved by CATMAT.

CATMAT would like to acknowledge the technical and administrative support from the Office of Border and Travel Health at the Public Health Agency of Canada for the development of this statement.

CATMAT Members: McCarthy A (Chair), Acharya A, Boggild A, Brophy J, Bui Y, Crockett M, Greenaway C, Libman M, Teitelbaum P, Vaughan S.

Liaison Members: Angelo K (US Centers for Disease Control Prevention), Audcent T (Canadian Paediatric Society) and Pernica J (Association of Medical Microbiology and Infectious Disease Canada).

Ex officio members: Marion D (Canadian Forces Health Services Centre, Department of National Defence), McDonald P (Bureau of Medical Science, Health Canada), Rossi C (Medical Intelligence, Department of National Defence) and Schofield S (Pest Management Entomology, Department of National Defence).