Chapter 7 - Treatment of malaria: Canadian recommendations for the prevention and treatment of malaria

Notice

Please note: Oral artemisinin-based combination therapies (ACTs) as first-line therapy for uncomplicated malaria, such as the combination artemether-lumefantrine (Coartem®), are not yet licensed nor available in Canada.

Updated 2019

What's new

- Change in recommended Primaquine dose to 30 mg base (52.6 mg salt) regardless of geographic area of malaria acquisition

- Clarification of hyperparasitemia for severe or complicated malaria

- Clarification of follow-on multidrug therapy for severe falciparum malaria

- Correction in Quinine doses

- Updated references where appropriate

Chapter 7: Treatment of malaria

Table of contents

- Preamble

- Background

- Methods

- Introduction

- General Principles of Management

- Management of Falciparum Malaria

- Severe Malaria

- Uncomplicated P. Falciparum

- Management of Non-Falciparum Malaria

- Management of Malaria when Laboratory results or Treatment drugs are delayed

- Primaquine Treatment

- Self-Treatment of Presumptive Malaria

- Acknowledgements

- References

Preamble

The Committee to Advise on Tropical Medicine and Travel (CATMAT) provides the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) with ongoing and timely medical, scientific, and public health advice relating to tropical infectious disease and health risks associated with international travel. PHAC acknowledges that the advice and recommendations set out in this statement are based upon the best current available scientific knowledge and medical practices, and is disseminating this document for information purposes to both travellers and the medical community caring for travellers.

Persons administering or using drugs, vaccines, or other products should also be aware of the contents of the product monograph(s) or other similarly approved standards or instructions for use. Recommendations for use and other information set out herein may differ from that set out in the product monograph(s) or other similarly approved standards or instructions for use by the licensed manufacturer(s). Manufacturers have sought approval and provided evidence as to the safety and efficacy of their products only when used in accordance with the product monographs or other similarly approved standards or instructions for use.

Background

There are a number of drugs that can be used to treat patients diagnosed with malaria. Selection of the appropriate approach involves many considerations, including first identifying the species and severity of infection. This chapter provides the Committee to Advise on Tropical Medicine and Travel (CATMAT)'s guidance and recommendations for the appropriate treatment and management of malaria.

Methods

This chapter of the CATMAT malaria guidelines was developed by a working group comprised of volunteers from the CATMAT committee. Criteria outlined in the CATMAT statement on Evidence based process for developing travel and tropical medicine related guidelines and recommendationsFootnote 1, were used to decide whether a Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) methodological approach would be appropriate for this chapter. The GRADE approach was not used in this chapter. Advice is based on a narrative review of the relevant literature and on expert opinion. The working group, with support from the secretariat, was responsible for: assessing available literature for any recent contributory evidence, synthesis and analysis, draft recommendations and chapter writing. The following guidance incorporates evidence from the most recently published WHO Guidelines for the Treatment of Malaria, which was developed using GRADEFootnote 2. Based on the evidence compiled as well as expert opinion, recommendations for interventions were made and are supported by available evidence, as indicated in tables 7.1 and 7.2.

Introduction

Uncomplicated malaria refers to symptomatic malaria without evidence of severe disease or evidence of vital organ dysfunction. The objective of treating uncomplicated malaria is to cure the infection. This is important: treatment will, in cases of Plasmodium falciparum, help prevent progression to severe disease. When choosing treatment regimens, it is important to consider drug tolerability, adverse effects of drugs and the speed of the therapeutic response.

Severe or complicated malaria refers to symptomatic malaria with:

1) hyperparasitemia

- ≥ 2% in children < 5 yearsFootnote *

- ≥ 5% for non-immuneFootnote † adults and children ≥ 5 years

- ≥10% for semi-immuneFootnote † adults and children ≥ 5 years, or

2) evidence of end organ damage or complications, at any parasitemia, as listed in Table 7.1.

In addition, patients unable to tolerate oral medication are at risk of progressing to severe disease.

The primary objective of treatment of severe or complicated malaria is to prevent death. For cerebral malaria, prevention of neurological deficits is also an important objective. When treating severe malaria in pregnancy, saving the life of the mother is the primary objective. Preventing recrudescence and avoiding minor adverse effects are secondary objectives.

In a case of P. falciparum asexual parasitemia and no other obvious cause of symptoms, the presence of one or more of the clinical or laboratory features in Table 7.1 classifies the person as having severe malaria.

| Clinical manifestation | Laboratory test |

|---|---|

| Prostration / impaired consciousness | Severe anemia (hematocrit < 20%; Hb ≤ 70 g/L) |

| Respiratory distress | Hypoglycemia (blood glucose < 2.2 mmol/L) |

| Multiple convulsions | Acidosis (arterial pH < 7.25 or bicarbonate < 15 mmol/L) |

| Circulatory collapse | Renal impairment (creatinine > 265 umol/L)Footnote 3 |

| Pulmonary edema (radiological) | Hyperlactatemia |

| Abnormal bleeding | Hyperparasitemia

|

| Jaundice | |

| Hemoglobinuria | |

Adapted from: Guidelines for the Treatment of Malaria, World Health Organization, 2015 (2)

In Canada, everyone (and especially children) with P. falciparum malaria should be considered for admission to hospital or should receive initial treatment in an observation unit. This is in an effort to ensure that treatment can be tolerated and to confirm decreasing parasitemia with treatment. Severe or complicated disease (Table 7.1) or the inability to tolerate oral therapy requires parenteral therapy and close clinical monitoring, preferably in an intensive care unit (ICU).

The Canadian Malaria Network (CMN) provides access to parenteral IV therapy (artesunate and quinine) and can assist in the management of malaria cases (see Appendix V).

General principles of management

The initial management of the patient depends on many factors, including the species and the severity of infection, the age of the patient, the pattern of drug resistance in the area of acquisition, as well as the safety, availability and cost of antimalarial drugs. At times, management decisions may be necessary before parasitology laboratory results become available. When managing malaria, three questions need to be answered:

- Is this infection caused by P. falciparum?

Treatment varies according to the species of malaria (See Table 7.2). P. falciparum can cause life-threatening disease in a nonimmune host. Falciparum malaria is a medical emergency. - Is this a severe or complicated infection? (See Table 7.1)

Severe or complicated malaria, regardless of causative species, requires parenteral therapy and sometimes an exchange transfusion. Parenteral artesunate and/or quinine are available through the CMN (see Appendix V). - Was the infection acquired in an area of known drug-resistant malaria? (See Appendix I)

Adjust treatment accordingly. Malarial parasites in most of the world are drug resistant. When in doubt, treat all P. falciparum malaria as drug resistant.

Table 7.2: Summary of malaria treatment recommendations

P. falciparum

The treatments of choice for uncomplicated P. falciparum malaria include:

Oral atovaquone–proguanilFootnote 2

Oral quinine combined with oral doxycycline or clindamycin

Combination therapy with an artemisinin derivativeFootnote 2 (not yet available in Canada)

Parenteral artesunate is recommended as first-line treatment for severe P. falciparum malaria, with parenteral quinine as an alternativeFootnote 4. Treatment should be completed with one full course of multidrug follow-on therapy (see Box 7.1).

Exchange transfusion may have benefits for treating hyperparasitemic cases of P. falciparumFootnote 5.

The use of steroids to treat severe or cerebral malaria has been associated with worse outcomes and should be avoided (6).

P. vivax and P. ovale

To prevent P. vivax and P. ovale malaria relapses, primaquine phosphate (30 mg base daily for 2 weeks) should be given concurrently or immediately following chloroquine treatmentFootnote 7 after exclusion of G6PD deficiency.

Management of falciparum malaria

Consider admitting nonimmune patients and all children with P. falciparum malaria, severe or uncomplicated, to hospital in an effort to ensure that antimalarial drugs are tolerated and to detect complications or early treatment failure. If hospital admission is decided against, all patients must be observed in the emergency department during their first dose of therapy to ensure that the drug is tolerated. To decrease risk of adverse outcomes from treatment as an outpatient, provide further doses of treatment before discharge or direct the person to a pharmacy that can fill the prescription appropriately.

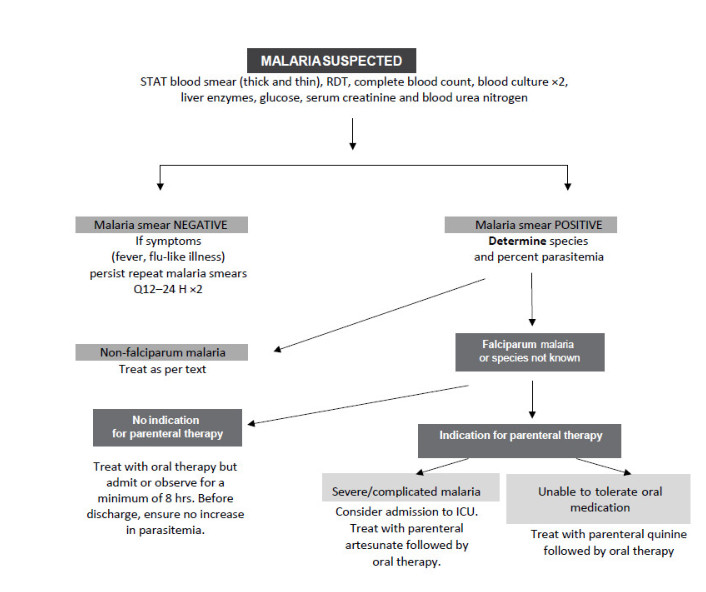

An algorithm for the management of malaria (see Figure 7.1) is based on two essential requirements: a parasitology laboratory result within two hours, and the availability of an appropriate antimalarial drug within one to two hours. (See below for malaria management when these prerequisites are not available). Treatment of malaria does not stop with the selection of appropriate antimalarial medications. Clinically assess all patients daily until fever ends and at any time that symptoms recur; for P. falciparum cases, repeat malaria smears daily until these are negative.

Please refer to the World Health Organization (WHO) Guidelines for the Treatment of MalariaFootnote 2 and Management of severe Malaria - a practical handbook Footnote 8 for a more detailed discussion.

Severe malaria

Severe malaria is usually due to P. falciparum infection. However, P. vivax can very occasionally lead to severe disease, including severe anemia, severe thrombocytopenia, pancytopenia, jaundice, splenic rupture, acute renal failure and acute respiratory distress syndromeFootnote 8Footnote 9Footnote 10Footnote 11Footnote 12. In addition, P. knowlesi, a simian malaria parasite, has emerged in southeast Asian countries including Brunei, Burma (Myanmar), Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam. P. knowlesi can also cause a severe and fatal infectionFootnote 13Footnote 14. Prompt and effective treatment and case management of knowlesi malaria should be the same as for severe falciparum malaria.

Severe P. falciparum infections may have a mortality rate of 20% or higher. Immediately hospitalize all cases of severe P. falciparum infection and provide urgent, intensive medical management, ideally in an ICUFootnote 15. Conduct clinical observations as frequently as possible; include vital sign monitoring, with accurate assessment of respiratory rate and pattern, coma score and urine output. Monitor blood glucose using rapid stick tests every four hours or more frequently, especially in unconscious patients. Treat seizures promptly; however, there is no role for prophylactic antiseizure medicationFootnote 2. Individuals with severe falciparum malaria are at risk of all the adverse outcomes listed in Table 7.1, as well as permanent neurologic deficits, chronic renal insufficiency and death.

Two classes of drugs are effective for the parenteral treatment of severe malaria: Cinchona alkaloids (quinine) and the artemisinin derivatives (artesunate, artemether and artemotil)Footnote 2Footnote 16. Randomized controlled trials comparing parenteral artesunate and quinine for severe malaria treatment in both adults and children and in different regions of the world clearly show the benefits of artesunateFootnote 16Footnote 17Footnote 18. There have been some recent reports of prolonged parasite clearance times following artemisinin-based treatment of P. falciparum in limited areas of southeast AsiaFootnote 19Footnote 20, however, artesunate remains the first-line treatment of choice for severe malaria acquired even in southeast AsiaFootnote 21. In cases of delayed response to artemisinin-based therapies in travellers from this region, it may be necessary to extend therapy. CATMAT recommends seeking expert advice on the management of these cases from a tropical disease specialist with particular expertise in malaria (see Appendix V for CMN contact information).

All patients with severe P. falciparum infections and all those who are unable to tolerate drugs orally should receive parenteral therapy. For patients meeting criteria for severe malaria, artesunate is the treatment of choice. If the only indication for parenteral therapy is vomiting or inability to tolerate oral therapy, without any criteria for severe malaria, request IV parenteral quinine (if no contraindications), since supplies of artesunate are limited. Intravenous artesunate and/or quinine are available 24 hours per day through the CMN (see Appendix V).

CATMAT recommends that all severe falciparum malaria patients who require parenteral artesunate receive follow-on therapy to ensure that one complete course of multidrug therapy is given (see Box 7.1).

- If the patient receives less than 4 doses of artesunate, then follow-on therapy should include combination therapy with either 3 days of atovaquone-proguanil, or 7 days of oral quinine + doxycycline/clindamycin.

- If the patient receives 4 full doses of artesunate over 48-hours, then follow-on therapy can be a choice of 3 days of atovaquone-proguanil, or 7 days of doxycycline or 7 days of clindamycin.

This recommendation for multidrug follow-on therapy is consistent with malaria treatment guidelines published by the United KingdomFootnote 21 and with the WHOGuidelines for the Treatment of MalariaFootnote 2 but differ from that of the CDCFootnote 22.

Many ancillary treatments have been suggested for the management of severe malaria, but few have been shown to improve outcomeFootnote 2. Individualize fluid resuscitation based on estimated deficit. The optimal rate of resuscitation, the role of colloids versus crystalloids, and the optimal electrolyte composition of the resuscitation solution have not been established, however avoiding unnecessary fluid resuscitation may be advisable in view of some RCT results suggesting possible harm in childrenFootnote 23Footnote 24. Check for hypoglycemia (potentially exacerbated by quinine therapy, which stimulates insulin release) in any patient who deteriorates suddenly, and treat this immediately. Avoid using steroids to treat severe or cerebral malaria since these have been associated with worse outcomesFootnote 2Footnote 6. Correct bleeding and coagulopathy in severe malaria using blood products and injection of vitamin KFootnote 2. Evidence of shock should prompt empiric use of broad-spectrum antibioticsFootnote 2. All patients with malaria should have blood cultures done to exclude intercurrent bacteremia.

In cases of severe or complicated P. falciparum infection with high parasitemia (> 10%), consider exchange transfusion as a potentially life-saving procedure. The rationale for exchange blood transfusion includes: the removal of infected red blood cells (RBCs) from the circulation, thereby reducing the parasite load; the rapid reduction of the antigen load and burden of parasite-derived toxins and metabolites; the removal of host-derived toxic mediators; and the replacement of rigid unparasitized RBCs with normal-functioning cells, thereby reducing microcirculatory obstruction.

Exchange blood transfusion requires a safe blood supply, intensive nursing and multiple units of packed red blood cells (PRBC). There is no consensus on either the indications or the volume of blood that needs to be exchanged; however, anticipate 5 to 10 PRBC unitsFootnote 5Footnote 25.

CATMAT strongly recommends consulting with an infectious or tropical disease expert when managing a patient with severe malaria. Members of the CMN are available to provide assistance. See Appendix V for CMN contact information.

Box 7.1: Chemotherapy of severe or complicated P. falciparum malaria

Parenteral artesunate and parenteral quinine are available 24 hours per day through the CMN. For contact information, see Appendix V.

- NOTE: If the only indication for parenteral therapy is vomiting or the inability to tolerate oral therapy, without any criteria for severe malaria, request parenteral quinine (if no contraindications). For patients meeting criteria for severe malaria, artesunate is preferred.

- NOTE: All patients on parenteral therapy should switch to oral therapy as soon as possible. Patients who meet criteria for severe malaria should receive at least 24 hours of parenteral therapy before switching to oral therapy.

Parenteral Artesunate

Give artesunate 2.4 mg/kg (for children <20 kg, the dose is 3 mg/kg) as an intravenous bolus over 1-2 minutes at 0, 12, 24 and 48 hours. After 24 hours, if possible switch to a full course of dual oral follow on therapy (atovaquone–proguanil, or doxycycline plus quinine, or clindamycin plus quinine). If oral medications are not possible after 48 hours of artesunate, daily IV artesunate doses can continue for a total of 7 days (or switch to a 7 day course of IV clindamycin plus IV quinine or IV doxycycline plus IV quinine (not licensed in Canada but available via Health Canada's Special Access Program ).

Plus follow-on oral therapy (start 4 hours after final dose of artesunate)

Atovaquone–proguanil (do not use as follow-on oral therapy if used as malaria chemoprophylaxis or creatinine clearance (CrCl) <30 ml/min):

Adults: 4 tablets (1000 mg atovaquone and 400 mg proguanil) daily for 3 days with fatty food;

Pediatric: 20 mg/kg atovaquone and 8 mg/kg proguanil once daily for 3 days with fatty food (see Chapter 8, Table 8.11)

OR

Doxycycline (do not use as follow-on oral therapy if used as malaria chemoprophylaxis; contraindications: pregnancy, breastfeeding, age < 8 years) plus quinine sulphateFootnote *:

Doxycycline:

Adults: 100 mg orally twice daily for 7 days;

Pediatric: 2 mg/kg (to a maximum of 100 mg) twice daily for 7 days

Quinine Sulphate (oral)Footnote *:

Adults: 500 mg base/600mg salt every 8 hours for 7 days

Pediatric: 8.3 mg /kg base (max 500 mg base) every 8 hours for 7 days

OR

Clindamycin (only if the patient is unable to take doxycycline or atovaquone–proguanil) plus quinine sulphateFootnote *:

Clindamycin:

Adults: 300 mg base every 6 hours for 7 days

Pediatric: 5 mg base/kg every 6 hours for 7 days

Quinine Sulphate (oral)Footnote *:

Adults: 500 mg base/600mg salt every 8 hours for 7 days

Pediatric: 8.3 mg /kg base (max 500 mg base) every 8 hours for 7 days

Parenteral Quinine

Quinine dihydrochloride (base) 5.8 mg/kg loading doseFootnote ** (quinine dihydrochloride [salt] 7 mg/kg) intravenously by infusion pump over 30 minutes, followed immediately by 8.3 mg base/kg (quinine dihydrochloride [salt] 10 mg/kg) diluted in 10 mL/kg isotonic fluid by intravenous infusion over 4 hours (maintenance dose). Repeat once every 8 hours until the patient can swallow (after a minimum of 24 hours if used for severe malaria), and then administer oral quinine tablets (plus doxycycline or clindamycin) to complete 7 days of quinine treatment, or change to a full dose of oral atovaquone-proguanil (see below).

PLUS (either concurrently or immediately after parenteral quinine)

Atovaquone–proguanil (do not use as follow-on oral therapy if used as malaria chemoprophylaxis or creatinine clearance (CrCl) <30 ml/min):

Adults: 4 tablets (1000 mg atovaquone and 400 mg proguanil) once daily for 3 days with fatty food;

Pediatric: 20 mg/kg atovaquone and 8 mg/kg proguanil once daily for 3 days with fatty food (see Chapter 8, Table 8.11).

OR

Doxycycline (do not use as follow-on oral therapy if used as malaria chemoprophylaxis; contraindications: pregnancy, breastfeeding, age < 8 years) plus oral quinine if IV quinine no longer necessary

Doxycycline:

Adults: 100 mg orally twice daily for 7 days;

Pediatric: 2 mg/kg (to a maximum of 100 mg) twice daily for 7 days

Quinine Sulphate (oral):

Adults: 500 mg base every 8 hours for a total of 7 days (combined IV and oral quinine)

Pediatric: 8.3 mg /kg base (max 500 mg base) every 8 hours for a total of 7 days (combined IV and oral)

OR

Clindamycin (only if the patient is unable to take doxycycline or atovaquone–proguanil) plus oral quinine if IV quinine no longer necessary

Clindamycin:

IV: 10 mg/kg (loading dose) intravenously, followed by 5 mg/kg every 8 hours for 7 days, OR

Oral: Adults: 300 mg base every 6 hours for 7 days

Pediatric: 5 mg base/kg every 6 hours for 7 days

Quinine Sulphate (oral):

Adults: 500 mg base every 8 hours for 7 days (combined IV and oral quinine)

Pediatric: 8.3mg /kg base (max 500 mg base) every 8 hours for a total of 7 days (combined IV and oral)

Figure 1 – Long description

This image is an algorithm that explains the process for the management of malaria. At the top, the algorithm begins with “Malaria Suspected.” If malaria is suspected, a STAT blood smear (thick and thin), rapid diagnostic test (RDT), complete blood count, blood culture (times two), liver enzymes, glucose, serum creatinine and blood urea nitrogen should all be completed for the patient.

The algorithm provides two options after “Malaria Suspected:” the malaria smear is negative or the malaria smear is positive. If the malaria smear is negative, but symptoms (e.g., fever, flu-like illness) persist, then smears should be repeated two more times, in 12 and 24 hours. If the smears are still negative, then malaria has been ruled out and the algorithm ends. If the malaria smear is positive, then the species and percent parasitemia should be determined.

Following the arrows of the algorithm, there are two options for the species and percent parasitemia: first, non-falciparum malaria or second, falciparum malaria or species not known. If the species is non-falciparum malaria, then management can follow as outlined in the text (refer to the Management of Non-Falciparium Malaria section). If the species is falciparum malaria or if the species is not known, then the algorithm shows two additional options: no indication for parenteral therapy or indication for parenteral therapy.

If there is no indication for parenteral therapy, then the patient should be treated with oral therapy, but admitted or observed for a minimum of 8 hours. In addition, before being discharged, the patient should be checked to ensure there is no increase in parasitemia. If there is an indication for parenteral therapy then the algorithm shows two final options: severe/complicated malaria or unable to tolerate oral medication. For severe complicated malaria, the patient should be considered for admission to the intensive care unit (ICU). In addition, the patient should be treated with parenteral artesunate followed by oral therapy. If the patient is unable to tolerate oral medication, then treatment with parenteral quinine should be followed by oral therapy.

ABBREVIATIONS: ICU—intensive care unit; RDT—rapid diagnostic test; STAT—with no delay.

Uncomplicated P. falciparum

Uncomplicated cases of P. falciparum can progress to severe malaria if not properly treated and monitored. Treat infections acquired in a chloroquine-sensitive zone with chloroquine alone (see Table 8.11). WHO advocates oral combination therapy containing artemisinin derivatives as the first choice for oral therapyFootnote 2. Until these agents are available in Canada, treat infections possibly or definitely acquired in drug-resistant regions (most of the cases of P. falciparum malaria seen in Canada) with atovaquone-proguanil or quinine and a second drug (preferably doxycycline). If the person can tolerate quinine orally as well as doxycycline, administer quinine and doxycycline simultaneously or sequentially, starting with quinine; if doxycycline is contraindicated, administer oral quinine and clindamycin simultaneously or sequentially. If oral medication is not tolerated, administer parenteral quinine (preferred) or artesunate (if contraindications to quinine) as per Table 8.11. The oral artemisinin combination therapy Co-artem (artemether/lumefantrine) is widely available in the US and Europe and particularly in sub-Saharan Africa. Using any medication acquired in an endemic area poses a risk due to high rates of counterfeit medicine. Practitioners should be cautious about using medication acquired in endemic areas to treat malaria, and should conduct close follow-up of patients.

Management of non-falciparum malaria

Chloroquine remains the treatment of choice for non-falciparum malaria (caused by P. vivax, P. ovale, P. malariae or P. knowlesi) outside of New Guinea (Papua New Guinea and Papua [Irian Jaya]) as per Table 8.11. In the case of non-falciparum malaria, conduct a clinical assessment daily until fever ends and whenever symptoms recur. Recurrence of asexual parasitemia less than 30 days after treatment suggests chloroquine-resistant P. vivax; recurrence after 30 days suggests primaquine-resistant P. vivax.

Recent reports have confirmed the presence and high prevalence (80%) of chloroquine-resistant P. vivax in Papua. Sporadic cases of chloroquine-resistant P. vivax malaria have been reported elsewhere (e.g. in Indonesia, Papua New Guinea, the Solomon Islands, Burma [Myanmar] and Guyana)Footnote 26. At present, chloroquine monotherapy can no longer be relied upon either for chemoprophylaxis or treatment of P. vivax acquired in New GuineaFootnote 2, and the optimal treatment is unknownFootnote 8.

Standard chloroquine doses (25 mg base/kg over 72 hours) combined with high-dose primaquine (0.5 mg base/kg daily for 14 days) have been suggested as treatment for chloroquine-resistant P. vivax acquired in Papua, with 14-day failure rates of 5% and 28-day failure rates of 15% (compared to 44% and 78% for chloroquine monotherapy, respectively)Footnote 27. Limited data also suggest that a combination of standard dose atovaquone-proguanil 7(4 tablets daily x 3 days) with primaquine (0.5 mg base/kg daily x 14 days) is >95% effectiveFootnote 28Footnote 29. Finally, a 7-day course of oral quinine may be used if clinical and/or parasitologic failure is observed with combination chloroquine-primaquine, or atovaquone/proguanil-primaquine. CATMAT recommends daily blood smears until resolution of parasitemia in those being treated for presumed chloroquine-resistant P. vivax. CATMAT further recommends seeking expert advice on the management of these cases from an infectious or tropical disease specialist (see Appendix V for CMN contact information).

Management of malaria when laboratory results or treatment drugs are delayed

If fever, travel history and initial laboratory findings (low white blood count and/or platelets) suggest a diagnosis of malaria but the malaria smear is delayed for more than 2 hours, start a therapeutic antimalarial.

When a severe or complicated P. falciparum infection is diagnosed and parenteral quinine or artesunate is indicated but not available for more than an hour, start quinine orally (after a dose of dimenhydrinate (Gravol®) or by nasogastric tube if necessary) until the parenteral drug is available. Note, do not use quinine loading dose if the patient received quinine or quinidine within preceding 24 hours or mefloquine within the preceding 2 weeks (see Box 7.1).

Primaquine treatment

Primaquine can be used as "primaquine anti-relapse therapy" (PART) for prevention of relapse of P. vivax or P. ovale malaria once a traveller has departed specific malarious areas where risk of P. vivax is high. As a PART strategy, daily 30-mg primaquine for 14 days overlapping the blood schizonticide chemoprophylactic (ie, atovaquone-proguanil, doxycycline, or mefloquine) may be reasonable in those with prolonged exposure (>6 months) in an area with probable intense exposure to P. vivax, such as Papua and Papua New Guinea. However, data supporting the PART strategy have been derived exclusively from studies of primaquine overlapping with chloroquine for primary prophylaxis, where efficacy approaches 95% (see Chapter 4 and Table 8.11 for dosage recommendations).

P. vivax and P. ovale have a persistent liver phase (hypnozoites) that is responsible for relapses and susceptible only to treatment with primaquine. Relapses caused by the persistent liver forms may appear months after exposure (occasionally, up to five years), even in the absence of primary symptomatic malaria infection. None of the currently recommended chemoprophylaxis regimens will prevent relapses due to these two species of Plasmodium. To reduce the risk of relapse following the treatment of symptomatic P. vivax or P. ovale infection, primaquine is indicated to provide “radical cure” (as per Table 8.11).

Patients should be tested to exclude glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) deficiency before giving antirelapse therapy with primaquine. G6PD deficiency is classified based on the level of residual enzyme activity in the red blood cells (RBC): Class I is the most severe form, and Classes II to IV having diminishing degrees of deficiency. A large retrospective study of 63,302 US army personnel found G6PD deficiency in 2.5% of males and 1.6% females. The highest rates were among African American males (12.2%), followed by Asian males (4.3%), African American females (4.1%), Hispanics males (2%), Hispanic females (1.2%) and Asian females (0.9%). The rates among Caucasians were low (0.3% of males and 0% females). None had Class I deficiency; however, 46 males and one female had Class II deficiency, which can be associated with severe, life-threatening hemolysisFootnote 30.

In cases with known or suspected G6PD deficiency, seek expert medical advice because primaquine may cause hemolysis in G6PD deficiency. Because the G6PD status of the fetus is unknown, primaquine is contraindicated in pregnancy. P. vivax or P. ovale infections during pregnancy should be treated with standard treatment doses of chloroquine (see Table 8.11). Relapses can also be prevented by weekly chemoprophylaxis with chloroquine until after delivery, when primaquine can be safely used by mothers with normal G6PD levels.

P. vivax isolates with a decreased responsiveness to primaquine are well documented in southeast Asia, in particular Papua New Guinea and Papua. Failure of primaquine radical treatment has been recently reported from Thailand, Somalia and elsewhereFootnote 31. As a result, the WHO’s recommended dosage of primaquine to prevent relapse for malaria acquired in Oceania and southeast Asia has increased to 30 mg base (0.5 mg base/kg) by weight daily for 14 daysFootnote 2. To avoid any potential under-dosing, CATMAT recommends use of 30 mg base (52.6 mg salt) daily x 14 days as the standard adult dose (0.5 mg/kg) regardless of geographic area of malaria acquisition. For pediatric patients, dose is by weight, to a maximum of 30 mg/base daily (See Table 8.11). This higher dose recommendation is consistent with malaria treatment guidelines published by the United KingdomFootnote 21 and the CDC in the United StatesFootnote 22.

In Canada primaquine is marketed as 26.3 mg salt (equivalent to 15 mg base) (Chapter 8, Table 8.10). There is often confusion in dispensing this medication; ensure prescription is clear that a total dose of 30 mg base requires 2 tablets daily, for 14 days, to avoid under-dosing of patients . See Table 8.11 for details on pediatric dose.

Blood infection with P. malariae may persist for many years, but it is not life-threatening and is easily cured by a standard treatment course of chloroquine (see Table 8.11). It can, however, be associated with complications such as splenomegaly, hypersplenism or renal dysfunctionFootnote 32Footnote 33.

Plasmodium knowlesi has emerged as a threat in southeast Asia. It can be confused by microscopists as P. malariae but can have a higher (> 1%) parasitemia than is seen in P. malariae infections. Systemic symptoms and complications can mimic P. falciparum malaria. Thus, people who have recently been in southeast Asia and have parasite levels over 1% and a parasite morphology resembling that of P. malariae can be diagnosed as having P. knowlesi. Treatment with chloroquine is reportedly effective, but systemic symptoms and complications similar to hyperparasitemic P. falciparum infections require very close monitoring and careful management,Footnote 34Footnote 35 and potentially, parenteral therapy with artesunate.

Self-treatment of presumptive malaria

Self-treatment of malaria (also known to as standby emergency treatment) has received little study, yet it is a frequent topic of discussion with travellers. It is particularly important to know about self-treatment (See Table 7.3) if going to sub-Saharan Africa where 90% of global morbidity and mortality from malaria occurs.

Table 7.3: Summary of malaria self-treatment recommendations

Individuals in chloroquine-sensitive regions should self-treat with chloroquine and then resume or start chloroquine prophylaxisFootnote 36Footnote 37Footnote 38. In chloroquine- and/or chloroquine and mefloquine-resistant P. falciparum regions, self-treatment should consist of a drug different to that used for prophylaxis, choosing from one of the following:

- atovaquone–proguanil (Malarone®) or

- oral quinine and doxycycline (substitute clindamycin if doxycycline is contraindicated) or

- artemether–lumefantrine (Coartem®), ideally purchased from a country with high standards of quality control (e.g. in Europe or the United States) so as to minimize the likelihood of using counterfeit productsFootnote 37Footnote 38Footnote 39Footnote 40.

A number of antimalarials are contraindicated for treatment of malaria (self-treatment or otherwise):

- mefloquineFootnote 41Footnote 42

- pyrimethamine–sulfadoxine (Fansidar) Footnote 43Footnote 44

- mefloquine–FansidarFootnote 42

- halofantrineFootnote 45

- chloroquine–FansidarFootnote 46.

Reasons for self-treatment include travel to remote regions where health care is a problem and travel to regions where malaria risk is small and the traveller would like to use self-treatment rather than long-term prophylaxisFootnote 36Footnote 46Footnote 47Footnote 48. If presumptive self-therapy is prescribed, the traveller should be told the following:

- Travellers to high-risk regions should never rely exclusively on a self-treatment regimenFootnote 36Footnote 49Footnote 50Footnote 51.

- Individuals at risk of malaria and unable to seek medical care or receive adequate malaria treatment drugs within 24 hours should carry effective medication for self-treatment of presumptive malariaFootnote 36Footnote 51.

- The signs and symptoms of malaria are nonspecific; many other diseases can mimic malaria, including influenza, dengue, typhoid, meningitis, and febrile gastroenteritis.

- Neither travellers (including expatriates) nor physicians can definitively diagnose malaria without a laboratory test for malariaFootnote 2Footnote 37Footnote 52.

- Both false-negative and false-positive malaria smears are reported to varying degree by all malaria diagnostic laboratories.

- Self-treatment is not definitive; it is a temporary, life-saving measure for 24 hours while seeking medical attention.

- Presumptive treatment requires a different drug if the traveller is taking something for chemoprophylaxis, except in chloroquine-sensitive regions (see Appendix 1)Footnote 36Footnote 48Footnote 51.

Acknowledgements

This chapter was prepared by: McCarthy A (lead), Boggild A, Crockett M, McDonald P and approved by CATMAT.

CATMAT would like to acknowledge the technical and administrative support from the Office of Border and Travel Health at the Public Health Agency of Canada for the development of this statement.

CATMAT Members: McCarthy A (Chair), Acharya A, Boggild A, Brophy J, Bui Y, Crockett M, Greenaway C, Libman M, Teteilbaum P, Vaughan S.

Liaison Members: Angelo K (US Centers for Disease Control Prevention), Audcent T (Canadian Paediatric Society) and Pernica J (Association of Medical Microbiology and Infectious Disease Canada).

Ex officio members: Marion D (Canadian Forces Health Services Centre, Department of National Defence), McDonald P (Bureau of Medical Science, Health Canada), Rossi C (Medical Intelligence, Department of National Defence) and Schofield S (Pest Management Entomology, Department of National Defence).