Bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccine: Canadian Immunization Guide

For health professionals

Updated: December 2014

On this page

- Key Information

- Epidemiology

- Preparations Authorized for Use in Canada

- Efficacy, Effectiveness and Immunogenicity

- Recommendations for Use

- Vaccine Administration

- Serologic Testing

- Storage Requirements

- Concurrent Administration with Other Vaccines

- Vaccine Safety and Adverse Events

- Other Considerations

- Selected References

Key Information (Refer to text for details)

- What

-

- Tuberculosis (TB) is transmitted by the airborne route and usually requires prolonged exposure for infection to occur.

- In Canada, TB occurs more commonly among Aboriginal people and foreign-born populations.

- Risk factors for the acquisition of TB include proximity to a person with infectious TB, particularly in crowded living conditions.

- Risk factors for progression to active TB include co-morbidities (such as HIV/AIDS, other immunodeficiencies, diabetes, silicosis), malnutrition, and smoking.

- Bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccine efficacy is estimated to be about 51% in preventing any TB disease and up to 78% in protecting newborns from miliary (disseminated) or meningeal TB.

- Intradermal administration of BCG vaccine usually results in erythema and a papule or ulceration, followed by a scar at the immunization site.

- Who

-

- BCG vaccine is not recommended for routine use in any Canadian population.

- Following consideration of local TB epidemiology and if a program of early detection and treatment of latent TB infection cannot be implemented, BCG vaccination may be considered in exceptional circumstances, such as for infants in high risk communities, for persons at high risk of repeated exposure, for certain long-term travellers to high prevalence countries, and in infants born to mothers with infectious TB disease.

- In high risk communities, infants less than 2 months of age do not need to be tuberculin skin tested before receiving BCG vaccine. For infants 2 to 6 months of age, an individual assessment of the risks and benefits of tuberculin skin testing prior to BCG vaccination is indicated. For infants over 6 months of age, administer BCG vaccine if the one-step tuberculin skin test (TST) is negative.

- Immunocompromised persons and pregnant women should not receive BCG vaccine, because it is a live vaccine.

- How

-

- BCG vaccine is administered as a single intradermal dose.

- Why

-

- One-third of the world's population is infected with TB and TB is the second leading cause of death from an infectious disease.

- The incidence of TB in Canada is among the lowest in the world. However, certain sub-populations in Canada remain at risk: Aboriginal persons in areas with a high prevalence of TB (particularly infants), Canadian-born elderly persons, immigrants, homeless persons and those infected with HIV.

Significant revisions since the last chapter update are highlighted in the CIG Table of Updates which is available on the PHAC website.

For additional information regarding tuberculosis and tuberculosis management in Canada, refer to the most current Canadian Tuberculosis Standards, 8th Edition (2022). For additional information regarding tuberculosis and travellers, refer to previously published Committee to Advise on Tropical Medicine and Travel (CATMAT) Statements and Statement Updates. For additional information regarding tuberculosis and HIV management, refer to WHO policy on collaborative TB/HIV activities: Guidelines for national programmes and other stakeholders.

Epidemiology

Disease description

Infectious agent

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious, bacterial disease caused by the bacillus Mycobacterium tuberculosis. The bacteria typically infect the lungs (pulmonary) but can affect other sites as well (extra-pulmonary).

Reservoir

Humans

Transmission

M. tuberculosis infection is spread almost exclusively by the airborne route. The droplets may remain suspended in the air and are inhaled by a susceptible host. The duration of exposure required for infection to occur is generally prolonged (commonly weeks, months or even years). The risk of infection with M. tuberculosis varies with the duration and intensity of exposure, the infectiousness of the source case, the susceptibility of the exposed person, and environmental factors. Although treatment courses are prolonged, effective treatment of the individual with active TB disease can reduce the infectiousness after two weeks.

Risk factors

A variety of factors influence the risk for M. tuberculosis infection, progression to active disease, and adverse outcomes from active disease:

- Risk factors for infection include proximity to a person with infectious TB, which may occur in a household setting where TB is present, in homeless shelters, in prisons and in certain occupations (e.g., working in a hospital or homeless shelter). In the household setting, over-crowding or living in large groups with a person with infectious TB increases the risk of infection.

- Progression from infection to active disease may be facilitated by co-morbidities such as HIV/AIDS and other immunodeficiencies, diabetes, silicosis, or malnutrition. Smoking is also associated with an increased risk for TB disease progression.

- Adverse outcomes from disease are associated with delayed diagnosis and treatment of alcoholism, malnutrition, injection drug use and homelessness. Poverty, access to treatment, and compliance with treatment regimens may be related to these risk factors.

Spectrum of clinical illness

Most persons infected with TB do not develop active disease; the infection remains latent. The risk of developing active TB varies according to time since infection, age, nutrition and medical co-morbidities and other factors listed above. The lifetime cumulative risk for the development of active TB disease in an infected person is estimated to be 5% to 10%. Approximately 50% of cases of active TB disease occur in the first 2 years following infection. In young children, the risk of disease after infection is inversely related to age. There is a very high risk (up to 40%) in infants, who can have rapid progression and have a higher probability of miliary (disseminated) or meningeal disease. Rapid progression from infection to active TB disease is also more common in persons who are immunocompromised (e.g., HIV-infected, solid organ transplantation, receiving immunosuppressive therapy).

Classic symptoms of active disease include cough, fever, weight loss and night sweats. The clinical diagnosis of miliary TB is difficult because of variable presentation. Despite appropriate treatment, mortality from miliary TB remains as high as 20%. TB meningitis is associated frequently with devastating consequences: 25% morbidity (i.e., permanent neurologic deficit) and 15% to 40% mortality, despite available treatment.

Disease distribution

Incidence/prevalence

Global

TB continues to be a leading cause of morbidity and mortality, especially in low and middle income countries. The global picture of TB is complicated by drug resistance and the HIV epidemic. About one-third of the world's population is infected with TB and TB is the second leading cause of death from an infectious disease worldwide. In 2010, there were an estimated 9 million cases of active TB disease and an estimated 1.4 million deaths from TB (1.1 million in non-HIV infected individuals and 350,000 in HIV-infected individuals).

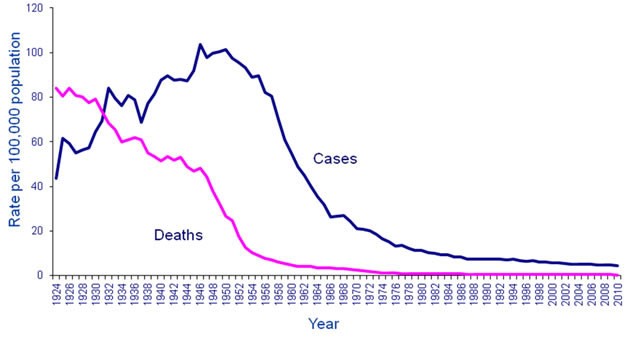

National

The reported incidence of TB in Canada is declining since a peak in the early 1940s (refer to Figure 1). In 2010, 1,577 cases of TB disease were provisionally reported, representing an incidence rate of 4.6 per 100,000 population. Most cases of active TB occurred in two groups: foreign-born individuals (66% of cases, rate of 13.3 per 100,000) and Aboriginal peoples (21% of cases, rate of 26.4 per 100,000). In 2010, Nunavut reported the highest incidence rate at 304 per 100,000 population, followed by the Northwest Territories (25.1) and Yukon (17.4).

The Canadian-born non-Aboriginal population accounts for 12% of cases, with an overall rate of 0.7 per 100,000. This rate is higher in the elderly, especially in those greater than 75 years of age. In 2010, only 4.9% of cases (77/1,577) were less than 15 years of age, and the corresponding age-specific incidence of these cases was 1.4 per 100,000.

Figure 1: Text description

This image is a graph showing the decline in the number of cases and the number of deaths from tuberculosis in Canada over time. The x axis represents the time between 1924 and 2010. The y axis represents rates per 100,000 population starting with 0 at the bottom to 120 cases at the top.

Two lines appear on the graph. The blue line represents the number of cases, the pink line represents the number of deaths. The blue line shows an initial incidence of approximately 44 cases per 100,000 in 1924. There was an irregular rise in cases to approx. 84 cases per 100,000 in 1931, a drop to 70 cases per 100,000 in 1938 and then a peak of 104 cases per 100,000 in 1948. There was a gradual decline to 90 cases per 100,000 by 1955 and then a steep decline in the number of cases to 26 cases per 100,000 by 1967. There was then a steady gradual decline to approximately 8 cases per 100,000 by 1987, down to the current level of 4.6 cases per 100,000 in 2010. The pink line for number of deaths shows a high of approximately 84 cases per 100,000 in 1924. This then takes a moderate decline to a mortality rate of 46 cases per 100,000 in 1948 (when the number of cases was the highest). There is then a drop in the mortality rate to approximately 8 cases per 100,000 by 1967; the mortality rate then hovers close to zero between 1977 and 2010.

Preparation Authorized For Use In Canada

BCG VACCINE (live, attenuated Bacille Calmette-Guérin vaccine derived from Mycobacterium bovis (Connaught substrain)), sanofi pasteur Ltd. (BCG)

Lyophilized preparations of BCG for intravesical use in the treatment of carcinoma of the urinary bladder are formulated at a significantly higher strength and must not be used for TB vaccination.

For complete prescribing information, consult the product leaflet or information contained within Health Canada's authorized product monographs available through the Drug Product Database. Refer to Table 1 in Contents of Immunizing Agents Available for Use in Canada in Part 1 for a list of all vaccines available for use in Canada and their contents.

Efficacy, Effectiveness and Immunogenicity

Efficacy and effectiveness

Clinical trials have demonstrated conflicting results regarding BCG vaccine's efficacy. Meta-analytic reviews have estimated the vaccine efficacy in preventing any TB disease at approximately 51%. The protective effect of BCG vaccine against disseminated TB in the newborn is estimated to be 78%.

The duration of BCG vaccine protection is not well-established. Although generally thought to have declining protection over time, one follow up study demonstrated a protective effect for as long as 60 years. BCG vaccine will not prevent the development of active TB in individuals who are already infected with M. tuberculosis. TB disease should be considered as a possible diagnosis in any vaccinee who presents with a suggestive history, or signs or symptoms of TB, regardless of immunization history.

Immunogenicity

Immunological correlates of protection against TB infection or disease after BCG vaccination have not been identified.

Recommendations For Use

BCG vaccine is not recommended for routine use in any Canadian population. Following consideration of local TB epidemiology and a decision that a program of early detection and treatment of latent TB infection cannot be implemented, BCG vaccination may be considered in exceptional circumstances, such as for infants in high risk communities, for persons at high risk of repeated exposure, for certain long term travellers to high prevalence countries, and in infants born to mothers with infectious TB disease.

- Infants in high risk communities

-

If processes for early identification and treatment of latent TB infection are not available, BCG vaccine may be considered for infants residing among groups of persons or in First Nations and Inuit communities with an average annual rate of smear-positive pulmonary TB greater than 15 per 100,000 population (all ages) during the previous 3 years, or for infants residing in populations with an annual risk of TB infection greater than 0.1%.

These criteria are based on the following:

- The rate of smear-positive pulmonary TB at 15 per 100,000 population represent a high incidence of infectious TB in designated geographic areas outside Canada. The Canadian Tuberculosis Committee and the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) have adopted the same breakpoint for use in the Canadian population. For information on international smear-positive pulmonary TB incidence rates, refer to www.publichealth.gc.ca/tuberculosis.

- When the annual risk of TB infection is less than 0.1%, the International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease recommends that selective discontinuation of BCG vaccination programs be considered.

The goal of BCG vaccination in infants is to prevent miliary TB and TB meningitis. Infants in high risk communities should receive BCG vaccine as soon after birth as feasible and preferably before 6 weeks of post-natal age or discharge into the community. Refer to Infants born prematurely.

If BCG vaccination is offered to all infants in a community that does not meet one of the above criteria, the vaccination program should be discontinued as soon as a program of early detection and treatment of latent TB infection can be implemented.

If BCG vaccination is considered appropriate, based on the criteria listed above, HIV testing in the mother of the child should be undertaken and shown to be negative, and there should be no evidence or known risk factors for immunodeficiency in the child being vaccinated, including no family history of immunodeficiency. Indications that an inherited immunodeficiency may be present in a family include a history of neonatal or infant deaths in the immediate or extended family. Such a history precludes BCG vaccination until immunodeficiency is excluded in the child. The optimal management of HIV exposed newborns living in communities meeting the criteria listed above is currently under National Advisory Committee on Immunization (NACI) review.

- Persons at high risk of repeated exposure

-

If processes for early identification and treatment of latent TB infection are not available, BCG vaccine may be considered for individuals who may be exposed repeatedly to persons with untreated, inadequately treated or drug-resistant active TB disease, or to tubercle bacilli in conditions where protective measures against infection are not feasible. Treatment of the source, removal from the source, TB screening and chemoprophylaxis of the exposed person as indicated, or any combination thereof, is generally preferred over the administration of BCG vaccine. Before taking any action, consultation with a TB or infectious disease expert is recommended. Refer to Workers for additional information. In exceptional circumstances, BCG vaccine may be considered for long term travellers to countries with a high TB prevalence. Refer to Travellers for additional information.

BCG vaccination: pre-immunization tuberculin skin testing

The one-step tuberculin skin test (TST) is recommended as part of the assessment of some infants for BCG vaccine (see below). Two-step tuberculin skin tests do not provide added value in this age group.

Tuberculin skin testing of infants prior to BCG vaccination

In infants who require BCG vaccine, the need for a one-step TST is outlined below:

- If the infant is less than 2 months of age: give BCG vaccine without prior TST because the risk of prior TB exposure is low and the sensitivity of the TST at detecting latent TB infection is unknown.

- If the infant is between 2 and 6 months of age: complete an individual risk-benefit assessment because the validity of TST in infants under 6 months of age is unknown. In these infants, false negative TST results may occur; false positive TST results are rare. Tuberculin skin testing in this age group may lead to early diagnosis of latent TB infection. However, there is a risk that the infant may be lost to follow-up between the TST and receiving BCG vaccine.

Based on the outcome of the risk-benefit assessment a vaccine provider may:

- Administer a one-step TST before BCG vaccine if there is a high risk of prior TB exposure OR

- Administer BCG vaccine without prior TST if the infant may not return after TST for BCG vaccine

If a TST is administered between 2 and 6 months of age, it should be recognized that the TST may be falsely negative, and therefore, despite a negative TST and BCG vaccination, active TB should still be considered if clinically compatible symptoms develop.

- If the infant is more than 6 months of age: complete a one-step TST. If the TST is negative, give BCG vaccine.

Refer to Other considerations for information regarding BCG vaccination and post-immunization tuberculin skin testing.

Pregnancy and breastfeeding

BCG vaccine has not been studied in pregnant or lactating women. BCG vaccine should not be given during pregnancy, although no harmful effects of BCG vaccination on the foetus have been observed. It is not known whether BCG vaccine is excreted in human milk. Because live vaccine may be excreted in human milk, caution should be exercised when considering BCG vaccine during lactation. Refer to Immunization in Pregnancy and Breastfeeding in Part 3 for additional general information.

Infants born prematurely

Infants born prematurely may receive BCG vaccine any time after 31 weeks of gestational age. Infants born prematurely (especially those weighing less than 1,500 grams at birth) are at higher risk of apnea and bradycardia following vaccination. Hospitalized premature infants should have continuous cardiac and respiratory monitoring for 48 hours after their first immunization. Refer to Immunization of Infants Born Prematurely in Part 3 for additional information.

Immunocompromised persons

BCG immunization is contraindicated in most immunocompromised persons, including HIV infection, altered immune status due to malignant disease or transplant, and impaired immune function secondary to treatment with corticosteroids, chemotherapeutic agents or radiation. There is substantial risk of disease due to dissemination of the vaccine bacille in immunocompromised people. Two exceptions to this contraindication are that BCG vaccine may be used, if indicated, in persons with complement deficiencies or isolated IgA deficiencies. Refer to Contraindications and Precautions. Refer to Immunization of Immunocompromised Persons in Part 3 for additional general information.

Persons with chronic diseases

Persons with chronic renal disease or undergoing dialysis, and those with hyposplenism or asplenia, may receive BCG vaccine if indicated. Refer to Immunization of Persons with Chronic Diseases in Part 3 for additional general information.

Travellers

In general travellers do not need BCG vaccine. TB screening and chemoprophylaxis as indicated is the preferred approach to TB control in travellers.

BCG vaccine may be considered for long-term travellers to countries with a high prevalence of TB in the following circumstances:

- Young children (under 5 years of age) who are anticipated to have no access to regular tuberculin skin testing

- Individuals who may have extensive occupational exposure to multidrug-resistant (MDR) tuberculosis

- Travellers who, for reasons of logistics, drug toxicity or intolerance, or personal choice, are expected not to be able to utilize the recommended surveillance strategy or chemoprophylaxis regimens.

Travellers working in hospitals in high incidence countries have an increased risk of acquiring TB, especially where HIV is co-endemic. Individuals who have immigrated to Canada are likely at higher risk than the average traveller when visiting friends and relatives in high prevalence countries, possibly due to their closer contact with the local population.

Consultation with an infectious disease or travel medicine specialist is recommended prior to travel. For additional information regarding TB and travellers, refer to Committee to Advise on Tropical Medicine and Travel (CATMAT) Archived: Risk assessment and prevention of tuberculosis among travellers. Refer to Immunization of Travellers in Part 3 for additional general information.

Workers

In general, workers do not need BCG vaccine. Appropriate personal protection, environmental controls, treatment of the source, and TB screening and chemoprophylaxis of the exposed person as indicated are the typical approaches to TB control in workers. If processes for early identification and treatment of latent TB infection are not available, BCG vaccine may be considered for workers (such as health care workers, laboratory workers, prison workers and those working in shelters for the homeless) who may be repeatedly exposed to persons with untreated, inadequately treated or drug-resistant active TB, or tubercle bacilli in conditions where protective measures against infection are not feasible. Consultation with a TB or infectious disease expert is recommended if BCG vaccine is considered for any group of workers. Refer to Immunization of Workers in Part 3 for additional general information.

Vaccine Administration

Vaccine reconstitution

BCG vaccine contains live, viable, attenuated mycobacteria. It must be handled as an infectious agent. Gloves should be worn when reconstituting the contents of the vial and for withdrawing the dose. The syringe, needle, vial with unused product, and all materials exposed to the product should be disposed in a container for biohazardous waste.

Dose, route of administration, and schedule

Dose

- Infants (12 months of age and younger): 0.05 mL (0.05 mg)

- Children (greater than 12 months of age) and adults: 0.1 mL (0.1 mg)

Route of administration

Reconstituted BCG vaccine should be administered by intradermal injection into the most superficial layers of the skin, in accordance with the instructions in the manufacturer's product leaflet. The area over the deltoid muscle is the preferred administration site. Refer to Vaccine Administration Practices in Part 1 for additional information.

Do NOT administer the product by the intravenous, intramuscular or subcutaneous routes. Intramuscular or subcutaneous administration may result in an abscess at the injection site.

Schedule

One dose of BCG vaccine should be administered.

Booster doses and re-immunization

Re-immunization with BCG vaccine is not recommended. One study in school-aged children documented that re-immunization with BCG vaccine conferred no additional protection.

Serologic Testing

Serologic testing is not recommended before or after receiving BCG vaccine.

Storage Requirements

BCG vaccine should be stored in a refrigerator at +2º C to +8º C, and protected from light. Care should be taken not to freeze it. The reconstituted product also should be stored in a refrigerator at +2º C to +8º C, and used within 8 hours. Refer to Storage and Handling of Immunizing Agents in Part 1 for additional general information.

Concurrent Administration with Other Vaccines

BCG vaccine may be administered concurrently with non-live vaccines and live vaccines at different injection sites using separate syringes and needles. In a blinded, randomized trial, neonates experienced less pain when the BCG vaccine was administered prior to concurrent intramuscular hepatitis B vaccine. If not given concurrently, a minimum interval of 4 weeks is recommended between administration of two live parenteral vaccines (such as BCG and measles-mumps-rubella) to reduce or eliminate potential interference from the vaccine given first on the vaccine given later. Live oral and nasal vaccines, like rotavirus vaccine and live attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV), may be given concurrently with, or at any time before or after, live parenteral vaccines, such as BCG vaccine. Refer to Timing of Vaccine Administration in Part 1 for additional general information.

Vaccine Safety and Adverse Events

Refer to Adverse events following immunization Part 2 for additional general information.

Common and local adverse events

Intradermal administration of BCG vaccine usually results in the development of erythema and either a papule or ulceration (in about 50%), followed by a scar at the immunization site. Keloid formation occurs in 2% to 4% of vaccine recipients. Non-suppurative regional lymphadenopathy occurs in 1% to 10%. Most reactions are generally mild and do not require treatment.

Less common and serious or severe adverse events

Serious adverse events are rare following immunization and, in most cases, data are insufficient to determine a causal association. Rare adverse events include local abscess formation and suppurative regional lymphadenitis (0.03% to 0.05% of vaccinees). These occur more frequently among infants less than 12 months of age than among older children and adults. There is some evidence in adults to suggest that subcutaneous administration of vaccine rather than the intended intradermal route is associated with more frequent abscess formation. Very rarely, disseminated BCG infection may occur and can be fatal in approximately 1 in 1 million vaccinations. Fatal cases almost always involve children with primary immunodeficiencies.

From 1993 to 1999, five cases of fatal disseminated BCG infection were reported by the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC)-Canadian Pediatric Society (CPS) Immunization Monitoring Program-Active (IMPACT) pediatric hospital surveillance network. These reports led to a thorough review by PHAC's Advisory Committee on Causality Assessment (ACCA) of the 5 deaths and 16 additional cases (1 non-fatal disseminated infection, 2 osteomyelitis, 8 abscesses, 4 lymphadenitis, 1 cellulitis) hospitalized for complications following BCG vaccination administered between 1993 and 2002. An additional fatal case of disseminated BCG was identified in 2003. All six fatal cases involved First Nations/Inuit infants with underlying immunodeficiency disorders that were not yet diagnosed at the time of immunization (vaccinated in the first week of life for 5 cases and at age 3 weeks for 1 case). All 6 cases were considered by ACCA as "very likely-certainly" associated with the vaccine. These events led to a change in NACI recommendations in 2004 and discontinuation of routine immunization of First Nations/Inuit infants in many Canadian provinces and territories.

Anaphylaxis following vaccination with BCG vaccine may occur but is very rare.

Guidance on reporting Adverse Events Following Immunization (AEFI)

Vaccine providers are asked to report, through local public health officials, any serious or unexpected adverse event felt to be temporally related to vaccination. An unexpected AEFI is an event that is not listed in available product information but may be due to immunization, or to a change in the frequency of a known AEFI. Refer to Adverse events following immunization in Part 2 and other guidance for additional information about AEFI reporting.

Contraindications and precautions

BCG vaccine is contraindicated in persons with a history of anaphylaxis after previous administration of the vaccine and in persons with proven immediate or anaphylactic hypersensitivity to any component of the vaccine or its container. In situations of suspected hypersensitivity or non-anaphylactic allergy to vaccine components, investigation is indicated, which may involve immunization in a controlled setting. Consultation with an allergist is advised. Refer to Table 1 in Contents of Immunizing Agents Available for Use in Canada in Part 1 for lists of all vaccines available for use in Canada and their contents. For BCG vaccine, potential allergens include latex in the vial stopper.

BCG immunization is contraindicated in most immunocompromised persons, including HIV infection, altered immune status due to malignant disease or transplant, and impaired immune function secondary to treatment with corticosteroids, chemotherapeutic agents or radiation. Exceptions include both complement and isolated IgA deficiency. Before an infant is vaccinated with BCG vaccine, the mother must be known to be HIV negative, and there should be no family history of immunodeficiency. Indications that an inherited immunodeficiency may be present in a family include a history of neonatal or infant deaths in the immediate or extended family. Such a history precludes BCG vaccination until immunodeficiency in the child is excluded.

If the BCG vaccine is administered accidently to an immunocompromised individual, consult an infectious diseases or TB specialist for treatment.

Immunization of pregnant women should be deferred until after delivery and generally should not be given if the mother is breastfeeding.

Extensive skin disease or burns are contraindications to BCG vaccination.

BCG is contraindicated for individuals with a positive TST, although immunization of tuberculin reactors has occurred frequently without complications.

Administration of BCG vaccine should be postponed in persons with severe acute illness. Persons with minor or moderate acute illness (with or without fever) may be vaccinated.

Refer to General Contraindications and Precautions in Part 2 for additional general information. Refer to Immunization of Immunocompromised Persons and Immunization of Persons with Chronic Diseases in Part 3 for additional general information.

Drug interactions

The BCG vaccine should not be administered to individuals receiving drugs with anti-tuberculous activity, since these agents may inactivate the vaccine bacillus.

Other Considerations

BCG vaccination: post-immunization tuberculin skin testing/interferon gamma release assay blood testing

BCG immunization may result in a positive TST. The benefits gained by immunization must be weighed against the potential loss of the TST as a primary tool to identify infection with M. tuberculosis. The increasing availability of interferon gamma release assay (IGRA) blood testing may reduce this concern because the BCG vaccine does not produce a "false positive" result with the IGRA test. However, the IGRA test is expensive and not available in all jurisdictions in Canada. The usefulness of this test in children less than 5 years of age has been questioned due to only a moderate concordance (69% to 89%) with the TST, although the IGRA is considered more sensitive.

BCG vaccine is one of the mostly widely used vaccines in the world and is currently given at or soon after birth to children in over 100 countries. Vaccine may have been received by several population groups, including immigrants from many European countries and most developing countries. In Canada, many Aboriginal Canadians and persons born in Quebec and Newfoundland and Labrador from the 1940s until the late 1970s were vaccinated.

If BCG vaccine is received in the first year of life, it is very unlikely to cause TST reactions of 10 mm or more in persons 10 years of age and older because tuberculin reactivity acquired through BCG vaccination in infancy generally wanes over time. Therefore, a history of BCG immunization received in infancy can be ignored in all persons 10 years of age and older when interpreting a TST result of 10 mm or greater.

If BCG vaccine was received between the ages of 1 and 5 years, persistent positive TST reactions may be observed in 10% to 15% of subjects even 20 to 25 years later. In persons vaccinated at 6 years of age and older, up to 40% will have persistent positive TST reactions. BCG-related TST reactions may be as large as 25 mm or more. Therefore, if BCG immunization was received after the first year of life, it can be an important cause of false-positive TST reactions, particularly in populations in which the expected prevalence of TB infection (i.e., true positive TST reactions) is less than 10%.

BCG immunization can be ignored as a cause of a positive TST under the following conditions:

- BCG vaccine was given during infancy, and the person tested is now 10 years of age or older. Although availability of the IGRA test is limited in Canada, IGRA testing has been shown to be a useful confirmatory test for latent tuberculosis infection in TST positive school children at low risk of TB infection who received BCG vaccine in infancy.

- The person is from a group with a high prevalence of TB infection (true positives), e.g., close contacts of an infectious TB case, Aboriginal Canadians from a high-risk community, immigrants from countries with a high incidence of TB.

- The person has a high risk of progression to disease if infected.

BCG vaccination should be considered the likely cause of a positive TST if:

- BCG vaccine was given after 12 months of age, AND

- there has been no known exposure to an active TB case or other risk factors, AND

- the person is either a Canadian-born non-Aboriginal OR an immigrant from a country with low TB incidence (e.g., Western Europe, United States).

Tuberculin skin testing should not be used as a method to determine whether previous BCG immunization was effective.

References

- American Academy of Pediatrics. Pickering LK, Baker CJ, Kimberlin DW, et al. (editors). Red Book: 2012 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 29th ed. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2012.

- Brewer TF, Colditz GA. Relationship between bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG) strains and the efficacy of BCG vaccine in the prevention of tuberculosis. Clin Infect Dis 1995;20(1):126-35.

- Burl S, Adetifa UJ, Cox M et al. Delaying Bacillus Calmette-Guerin Vaccination from Birth to 4 ½ months of age reduces postvaccination Th1 and IL-17 responses but leads to comparable mycobacterial responses at 9 months of age. J Immunol 2010;185:2620-28.

- Canadian Lung Association/Canadian Thoracic Society, Public Health Agency of Canada. Canadian tuberculosis standards, 6th edition. Ottawa (Canada): Canadian Lung Association and Government of Canada; 2007. Accessed July 2011.

- Canadian Tuberculosis Committee. Recommendations on Interferon Gamma

Release Assays for the Diagnosis of Latent Tuberculosis Infection--2010 Update. Can Comm Dis Rep 2010;36(ACS-5). - Colditz GA, Berkey CS, Mosteller F et al. The efficacy of bacillus Calmette-Guérin vaccination of newborns and infants in the prevention of tuberculosis: meta-analyses of the published literature. Pediatrics 1995;96:29-35.

- Colditz GA, Brewer TF, Berkey CS et al. Efficacy of BCG vaccine in the prevention of tuberculosis. Meta-analysis of the published literature. JAMA 1994;271(9):698-702.

- Committee to Advise on Tropical Medicine and Travel. Risk assessment and prevention of tuberculosis among travellers. Can Comm Dis Rep 2009;37(ACS-5).

- Deeks SL, Clark M, Scheifele D et al. Serious adverse events associated with bacille Calmette-Guérin vaccine in Canada. Pediatr Infect Dis 2005;24(6):538-41.

- Faridi MA, Kaur S, Krishnamurthy S et al. Tuberculin conversion and leukocyte migration inhibition test after BCG vaccination in newborn infants. Hum Vaccin 2009;5: 690-95.

- Fine PE. Bacille Calmette-Guérin vaccines: a rough guide. Clin Infect Dis 1995;20(1):11-14.

- Houston S, Fanning A, Soskolne CL et al. The effectiveness of bacillus Calmette-Guérin (BCG) vaccination against tuberculosis: a case-control study in Treaty Indians, Alberta, Canada. Am J Epidemiol 1990;131(2):340-48.

- Jacobs S, Warman A, Richardson R et al. The tuberculin skin test is unreliable in school children BCG-vaccinated in infancy and at low risk of tuberculosis infection. Pediatri Infect Dis 2011;30(9):754-58.

- Lotte A, Wasz-Hockert O, Poisson N et al. BCG complications. Estimates of the risks among vaccinated subjects and statistical analysis of their main characteristics. Adv Tuberc Res 1984;21;107-93.

- O'Brien KL, Ruff AJ, Louis MA et al. Bacille Calmette-Guérin complications in children born to HIV-1 infected women with a review of the literature. Pediatrics 1995;95(3):414-18.

- Pabst HF, Godel J, Grace M et al. Effect of breast-feeding on immune response to BCG vaccination. Lancet 1989;1(8633):295-97.

-

Public Health Agency of Canada. Yuan L. Compendium of Latent Tuberculosis Infection (LTBI) Prevalence rates in Canada. July 2007. Accessed September 2012.

- Sanofi pasteur Ltd. Package Insert - BCG Vaccine. September 2002.

- Thayyil-Sudhan S, Kumar A, Singh M et al. Safety and effectiveness of BCG vaccine in pre-term babies. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed 1999;81:F64-F66.

- World Health Organization. Global tuberculosis control 2011. Accessed January 2012.

- World Health Organization. Global tuberculosis programme and global programme on vaccines. Statement on BCG revaccination for the prevention of tuberculosis. Wkly Epidemiol Rec 1995;70(32):229-31.

- World Health Organization. WHO policy on collaborative TB/HIV activities: Guidelines for national programmes and other stakeholders. Accessed June 2012.