Recommendations for public health programs on the use of pneumococcal vaccines in children, including the use of 15-valent and 20-valent conjugate vaccines

Download in PDF format

(1.57 MB, 65 pages)

Organization: Public Health Agency of Canada

Date published: 2024-03-11

Cat.: HP5-239/1-2024E-PDF

ISBN: 978-0-660-70388-6

Pub.: 230765

On this page

- Preamble

- Summary of information contained in this NACI statement

- Introduction

- Methods

- Vaccine

- Evidence summary

- Ethics, equity, feasibility and acceptability considerations

- Economics

- Recommendations

- Research and surveillance priorities

- List of abbreviations

- Acknowledgements

- Appendix A: Tables

- References

Preamble

The National Advisory Committee on Immunization (NACI) is an External Advisory Body that provides the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) with independent, ongoing and timely medical, scientific, and public health advice in response to questions from PHAC relating to immunization.

In addition to burden of disease and vaccine characteristics, PHAC has expanded the mandate of NACI to include the systematic consideration of programmatic factors in developing evidence-based recommendations to facilitate timely decision-making for publicly funded vaccine programs at provincial and territorial levels.

The additional factors to be systematically considered by NACI include economics, ethics, equity, feasibility and acceptability. Not all NACI statements will require in-depth analyses of all programmatic factors. While systematic consideration of programmatic factors will be conducted using evidence-informed tools to identify distinct issues that could impact decision-making for recommendation development, only distinct issues identified as being specific to the vaccine or vaccine-preventable disease will be included.

This statement contains NACI's independent advice and recommendations, which are based upon the best current available scientific knowledge. This document is being disseminated for information purposes. People administering the vaccine should also be aware of the contents of the relevant product monograph. Recommendations for use and other information set out herein may differ from that set out in the product monographs of the Canadian manufacturers of the vaccines. Manufacturer(s) have sought approval of the vaccines and provided evidence as to its safety and efficacy only when it is used in accordance with the product monographs. NACI members and liaison members conduct themselves within the context of PHAC's Policy on Conflict of Interest, including yearly declaration of potential conflict of interest.

Summary of information contained in this NACI statement

The following highlights key information for immunization providers. Please refer to the remainder of the statement for details.

What

The bacterium Streptococcus pneumoniae can lead to invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD), a serious communicable disease, and other infections such as community acquired pneumonia and acute otitis media. There are currently more than 100 known serotypes of S. pneumoniae. The majority of pneumococcal infections are caused by only a portion of these serotypes.

Health Canada has recently authorized two new pneumococcal conjugate (Pneu-C) vaccines for infants, children and adolescents 6 weeks through 17 years of age:

- Pneu-C-15 (15-valent) is authorized with an indication for prevention of IPD caused by 15 serotypes of S. pneumoniae.

- Pneu-C-20 (20-valent) is authorized with an indication for prevention of IPD caused by 20 serotypes of S. pneumoniae.

Who

IPD is most common in young children, older adults, and groups at increased risk due to a medical condition and/or environmental/living conditions (see Table 1). NACI continues to recommend that all routine infant immunization programs in Canada include a conjugate pneumococcal vaccine.

For routine immunization programs in children less than 5 years of age who are not at increased risk of IPD:

- NACI recommends that either Pneu-C-15 or Pneu-C-20 should be the current product of choice for children less than five years of age in routine immunization programs.

For children at increased risk of IPD due to a medical and/or environmental/living conditions (Table 1):

- NACI recommends that Pneu-C-20 should be used for children 2 months to less than 18 years of age who have conditions that result in increased risk of IPD. Children who have started their pneumococcal vaccine series with Pneu-C-13 or Pneu-C-15 should complete their series with Pneu-C-20.

- NACI recommends that children under 18 years of age who are at increased risk of IPD due to medical and/or environmental/living conditions and who have completed their recommended immunization schedule with Pneu-C-13 or Pneu-C-15, should receive one catch-up (additional) dose of Pneu-C-20.

- NACI recommends that Pneu-C-20 should be offered to children less than 18 years of age who received a hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) after consultation with their transplant specialist.

For additional information, including supporting evidence and rationale for these recommendations, please see Recommendations.

Table 1: Risk conditions resulting in increased risk of IPD

Medical risk conditions

- Chronic cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leak

- Cochlear implants, including those who are to receive implants. The highest risk is in the weeks following implant. It is best to administer prior to implant but surgery should not be delayed to administer vaccine. Vaccine should be given as soon as possible.

- Chronic kidney disease, particularly those with nephrotic syndrome, on dialysis, or with renal transplant

- Chronic liver disease, including hepatic cirrhosis and biliary atresia

- Chronic neurologic condition that may impair clearance of oral secretions

- Functional or anatomic asplenia (including sickle cell disease and other hemoglobinopathies, congenital or acquired asplenia, or splenic dysfunction)

- Diabetes mellitus

- Chronic heart disease (including congenital heart disease and cyanotic heart disease)

- Chronic lung disease, including asthma requiring acute medical care in the preceding 12 months

- Congenital immunodeficiencies involving any part of the immune system, including B-lymphocyte (humoral) immunity, T-lymphocyte (cell) mediated immunity, complement system (e.g. properdin, or factor D deficiencies)

- Immunocompromising therapy, including use of long-term corticosteroids, chemotherapy, radiation therapy, and post-organ transplant therapy

- HIV infection

- Hematopoietic stem cell transplant (recipient)* see separate recommendation

- Malignant neoplasms, including leukemia and lymphoma

- Solid organ transplant

Environmental or living conditions for individuals

- Who live in communities or settings experiencing sustained high IPD rates

- Who are underhoused or experiencing houselessness

- Who are in residential care for children with complex medical needs

How

Pneu-C-15 and Pneu-C-20 are administered intramuscularly using a single-dose, prefilled syringe. A single dose of Pneu-C-15 and Pneu-C-20 is 0.5ml.

Pneu-C-15 and Pneu-C-20 are provided either using a 3-dose (2+1) schedule at 2 months, 4 months and 12 months of age, or a 4-dose (3+1) schedule at 2 months, 4 months and 6 months followed by a dose at 12 to 15 months of age. For more information on immunization schedules, including for children at increased risk of IPD and by immunization history, refer to the pneumococcal vaccines chapter of the Canadian Immunization Guide and Recommendations (Table 7).

Contraindications for Pneu-C-15 and Pneu-C-20 include hypersensitivity (e.g., anaphylaxis) to the vaccine or any of its components. Pneumococcal vaccines may be administered concurrently with other vaccines, except for a different formulation of pneumococcal vaccine (e.g., do not concurrently administer conjugate and polysaccharide pneumococcal vaccines).

Why

Pneumococcal disease can lead to long-lasting complications and can result in significant morbidity and mortality, especially for young children and other children at increased risk of IPD. The most effective way to prevent these infections is through immunization. Pneu-C-15 and Pneu-C-20 are designed to prevent infection from a larger number of serotypes than previous pneumococcal vaccines.

Introduction

Guidance objective

The need for updated National Advisory Committee on Immunization (NACI) guidance on the pediatric pneumococcal vaccine program arose from the authorization of new pediatric indications for two pneumococcal conjugate (Pneu-C) vaccines. On July 8, 2022, Health Canada authorized the use of a pneumococcal conjugate 15-valent vaccine (Pneu-C-15, Vaxneuvance®), for active immunization of children from 6 weeks through 17 years of age for the prevention of invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD) caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae serotypes 1, 3, 4, 5, 6A, 6B, 7F, 9V, 14, 18C, 19A, 19F, 22F, 23F and 33F. On July 21, 2023, Health Canada authorized the use of a pneumococcal conjugate 20-valent vaccine (Pneu-C-20, Prevnar 20®) for the prevention of IPD caused by S. pneumoniae serotypes 1, 3, 4, 5, 6A, 6B, 7F, 8, 9V, 10A, 11A, 12F, 14, 15B, 18C, 19A, 19F, 22F, 23F and 33F in children 6 weeks through 17 years of age.

Note: For purposes of this document, 'children' refers to infants, children and adolescents under 18 years of age.

On October 4th, 2022, NACI provided interim guidance on the use of Pneu-C-15 vaccine, recommending that it may be used interchangeably with Pneu-C-13 in children 6 weeks to 17 years of age. Following the approval of Pneu-C-20 for use in children, additional guidance was requested by Provinces and Territories on the use of these vaccines in routine pediatric immunization programs in Canada.

The primary objectives of this Statement are to:

- review the evidence on the potential benefits (immunogenicity), risks (safety) and modelled impact and cost-effectiveness of pediatric pneumococcal immunization programs using Pneu-C-15 or Pneu-C-20 on the reduction on the pneumococcal disease burden in Canada.

- provide recommendations for the use of Pneu-C-15 and Pneu-C-20 vaccines in routine pediatric programs in Canada and for children at increased risk of IPD.

Background on pneumococcal vaccines, immunization programs and recommendations for children in Canada

In Canada, routine immunization programs for IPD for infants include the use of Pneu-C vaccines provided either using a 3-dose (2+1) schedule at 2 months, 4 months and 12 months of age or a 4-dose (3+1) schedule at 2 months, 4 months and 6 months followed by a dose at 12 to 15 months of age. Infants at increased risk of IPD due to an underlying medical condition have previously been recommended to receive the 4-dose schedule of Pneu-C-13 vaccine, as well as one dose of Pneu-P-23 vaccine at 24 months of age, at least 8 weeks after Pneu-C-13 vaccine, to increase protection against additional S. pneumoniae serotypes not contained in Pneu-C-13. Children with certain medical conditions were also recommended an additional booster dose of Pneu-P-23 vaccine at least 5 years after any previous dose of Pneu-P-23 vaccine.

In 2021, it was estimated that 85.1% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 83.1% to 87.0%) of 2-year-old children in Canada had at least 3 doses of the pneumococcal vaccineFootnote 1. The current national vaccination coverage goal by 2025 is to have 95% of 2-year-old children immunized with at least 3 doses of the recommended pneumococcal vaccineFootnote 2.

Methods

In brief, the stages in the preparation of a NACI statement are:

- Knowledge synthesis: retrieval and summary of individual studies, and assessment of the risk of bias of included studies.

- Summary of vaccine-relevant evidence: benefits (examples would include: immunogenicity, efficacy and effectiveness profiles compared with existing vaccines) and potential harms (safety profile compared with existing vaccines), considering the certainty of the synthesized evidence and, where applicable, the magnitude of effects observed across the studies.

- Systematic assessment of program-relevant considerations related to ethics, equity, feasibility, and acceptability (EEFA).

- Economic evaluation, including a systematic review of economic evaluations and economic modelling.

- Use of all available evidence to inform recommendations.

NACI reviewed the available evidence on Pneu-C-15 and Pneu-C-20 immunogenicity and safety, pneumococcal disease burden, and cost-effectiveness and considerations for ethics, equity, feasibility, and acceptability during meetings held on June 12, July 7 and September 27, 2023. Following NACI discussion, additional evidence on the risk of IPD in children with risk factors was reviewed by the Committee on November 16, 2023. Recommendations on the use of pneumococcal vaccines in pediatric populations were approved on December 5, 2023.

Further information on NACI's process and procedures is available elsewhereFootnote 3. Comprehensive NACI recommendations for the use of pneumococcal vaccines in Canada are provided in the pneumococcal vaccines chapter in the Canadian Immunization Guide (CIG).

Burden of invasive pneumococcal disease

Since 2000, IPD has been nationally notifiable in Canada through the Canadian Notifiable Disease Surveillance System (CNDSS), with all provinces and territories reporting cases that meet the national case definition. For this Statement, the CNDSS line list data used to assess the burden of IPD among different pediatric age groups were available from ten provinces and from the International Circumpolar Surveillance (ICS) program for the three territories. In addition to the three territories, regions of Canada captured in the ICS system also include northern Labrador and northern Quebec. The incidence of IPD in these regions was compared to national IPD incidence using aggregate CNDSS data. All cases were presumed to meet the national case definition of IPD. More information about the CNDSS data is provided at Notifiable Diseases Online, including limitations to the CNDSS data.

The National Microbiology Laboratory (NML) collaborates with public health laboratories to conduct passive, laboratory-based surveillance of IPD in Canada and releases regular reportsFootnote 4. All IPD isolates from public health laboratories are serotyped by the NML, although specimen collection may be limited by variable regional standards, the preliminary nature of some data, and the availability of bacterial isolates for testing. Serotype data may also be biased toward overrepresentation of more virulent serotypes for which medical treatment is sought and clinical specimens are taken. Information on serotype distribution is provided for 80% to 98% of all IPD cases reported to CNDSS.

For the serotype reporting in this Statement, serotype 6C was included with Pneu-C-13 serotypes due to cross protection with 6A. Serotypes 15B and 15C were grouped together as 15B/C because of reported reversible switching between them in vivo during infection, making it difficult to precisely differentiate between the two types.

Additional information on complications of pneumococcal disease were collected through the pediatric hospital-based surveillance network IMPACT (Immunization Monitoring Program, ACTive) which covers 90% of tertiary care pediatric beds in Canada.

There are limited Canadian-specific data on pneumococcal disease in children with medical risk conditions. NACI reviewed information on pneumococcal disease in this population based on data from a recent review conducted to inform the United States (US) Advisory Committee on Immunization PracticesFootnote 5.

Literature review of Pneu-C-15 and Pneu-C-20

The overarching research question to support the evidence review is: What is the efficacy, effectiveness, immunogenicity, and safety of Pneu-C-15 and Pneu-C-20 compared to Pneu-C-13, when used to reduce the risk of IPD in children under 18 years of age?

Population: Children 6 weeks to under 18 years of age with and without additional risk factors for IPD (Table 1) who have never been vaccinated, have an incomplete vaccine series, or have completed their vaccine series (for catch-up/additional doses).

Intervention: Pneu-C-15 or Pneu-C-20 (alone or in a mixed series).

Comparator: Currently recommended age and risk factor-appropriate pneumococcal vaccine schedule.

Outcomes: Death due to S. pneumoniae serotypes included in the vaccine (i.e., vaccine serotype), IPD due to vaccine serotypes, acute otitis media (AOM) or pneumococcal community acquired pneumonia (CAP) due to vaccine serotypes, and serious adverse events following vaccination.

As efficacy/effectiveness and safety data were not published at the time of the initial evidence review, NACI evaluated immunogenicity and safety data accessible in the regulatory submission to Health Canada and/or were presented to NACI by the manufacturer.

Immunogenicity datapoints that were reviewed by NACI included opsonophagocytic (OPA) geometric mean titers (GMT), IgG geometric mean concentrations (GMC), and seroresponse rates (defined according to the World Health Organization standard of either a greater or equal to 4-fold increase in pre-vaccination GMC/GMT ratios or GMC values of greater or equal to 0.35 μg/mL)Footnote 6. The data that were extracted for analysis included information on the study design, population, intervention, comparator, and outcomes of interest. The risk of bias for each study was assessed using the Cochrane Risk of Bias Tool. The Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations (GRADE) framework was used to assess the certainty of evidence where possible, based on availability of outcome information. Immunogenicity outcomes (ratios/differences) with Pneu-C-15 or Pneu-C-20 compared to Pneu-C-13 were considered to be numerically lower or higher when all CI values in all studies were less than 1.00 or greater than 1.00, respectively. Serotypes for which these values could not be determined were either those in which CIs were null-inclusive (i.e., included 1.00) or where results were mixed across studies. GRADE data tables for analyzed studies are available in Appendix A.

Literature review of Pneu-C-15 and Pneu-C-20 cost-effectiveness

A systematic review of the cost-effectiveness of Pneu-C-15 and Pneu-C-20 vaccines for preventing pneumococcal disease in infants and children included published studies of economic evaluations conducted in populations aged less than 18 years, comparing currently used vaccines to prevent pneumococcal disease to Pneu-C-15 or Pneu-C-20 and measures of economic outcomes (incremental cost per quality-adjusted life year [QALY], cost per life year, etc.). A systematic literature search for English- and French-language studies was conducted in six electronic databases: Embase, Ovid Medline, International Pharmaceutical Abstracts, EBM Reviews, SCOPUS, and Econlit. The search was limited to records published between January 1, 2018, to March 7, 2023. All costs were adjusted to 2022 Canadian dollars and are reported as such. Additional details of the economic literature review are provided in a supplementary economic evidence summary.

NACI cost-utility analysis

A model-based cost-utility analysis was conducted from health system and societal perspectives. A multi-age static cohort model was used to compare the benefits (in QALYs) and costs (in 2022 Canadian dollars) associated with using Pneu-C-15 or Pneu-C-20 compared to Pneu-C-13 in previously unvaccinated infants that are eligible for routine pneumococcal vaccination. The analysis used a 10-year time horizon, with lifetime costs and consequences of pneumococcal disease discounted at 1.5% and all costs adjusted to 2022 Canadian dollars. Details of the cost-utility analysis are provided in a supplementary economic evidence summary.

Vaccine

There are currently five vaccines in Canada that are authorized for use in children less than 18 years of age:

- Pneu-P-23 (Pneumovax®23) is a sterile solution of 23 highly purified capsular polysaccharidesFootnote 7.

- Pneu-C-10 (Synflorix®) is a sterile suspension of saccharides of the capsular antigens of 10 serotypes of S. pneumoniae conjugated to the Non-Typeable Haemophilus influenza protein D, diphtheria or tetanus toxoidFootnote 8.

- Pneu-C-13 (Prevnar®13) is a sterile solution of polysaccharide capsular antigen of 13 serotypes of S. pneumoniae. The antigens are individually conjugated to a Corynebacterium diphtheriae (CRM197) protein carrierFootnote 9.

- Pneu-C-15 (Vaxneuvance®) is a sterile suspension of purified capsular polysaccharides from 15 serotypes of S. pneumoniae. The antigens are individually conjugated to diphtheria CRM197 protein carrierFootnote 10.

- Pneu-C-20 (Prevnar 20TM) is a sterile saccharide suspension of the capsular antigens of 20 serotypes of S. pneumoniae. The antigens are individually conjugated to diphtheria CRM197 proteinFootnote 11.

Additional information about the composition of these vaccines is available in Table 2.

| Vaccine name | PneuMOVAX®23 (Pneu-P-23) |

SYNFLORIX® (Pneu-C-10) |

PREVNAR®13 (Pneu-C-13) |

VAXNEUVANCE® (Pneu-C-15) |

PREVNAR 20TM (Pneu-C-20) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Manufacture | Merck | GSK | Pfizer | Merck | Pfizer |

| Date of initial authorization in Canada / pediatric age of authorization | December 23, 1983 / 2 years old to 17 years old |

December 11, 2008/ 6 weeks to 5 years old |

December 21, 2009/ 6 weeks to 17 years old |

July 8, 2022 / 6 weeks to 17 years old |

May 9, 2022 (adult) July 21, 2023 (children)/ 6 weeks to 17 years old |

| Type of vaccine | Polysaccharide | Conjugate | Conjugate | Conjugate | Conjugate |

| Vaccine composition | 25 mcg of capsular polysaccharides from each of S. pneumoniae serotypes 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6B, 7F, 8, 9N, 9V, 10A, 11A, 12F, 14, 15B, 17F, 18C, 19A, 19F, 20, 22F, 23F and 33F, sodium chloride 0.9 % w/w, phenol 0.25% w/w and water for injection. |

1 mcg of each saccharide for S. pneumoniae serotypes 1, 5, 6B, 7F, 9V, 14 and 23F, and 3 mcg of saccharide for serotype 4, 18C and 19F, Non-Typeable Haemophilus influenzae |

2.2 mcg of each saccharide for S. pneumoniae serotypes 1, 3, 4, 5, 6A, 7F, 9V, 14, 18C, 19A, 19F and 23F, 4.4 mcg of saccharide for serotype 6B, 34 mcg CRM197 carrier protein, 4.25 mg sodium chloride, 100 mcg polysorbate 80, 295 mcg succinic acid and 125 mcg aluminum as aluminum phosphate adjuvant and water for injection |

32 mcg of total pneumococcal polysaccharide (2.0 mcg each of polysaccharide serotypes 1, 3, 4, 5, 6A, 7F, 9V, 14, 18C, 19A, 19F, 22F, 23F and 33F and 4.0 mcg of polysaccharide serotype 6B) conjugated to 30 mcg of CRM197 carrier protein, 125 mcg of |

2.2 mcg of each of S. pneumoniae serotypes 1, 3, 4, 5, 6A, 7F, 8, 9V, 10A, 11A, 12F, 14, 15B, 18C, 19A, 19F, 22F, 23F and 33F saccharides, 4.4 mcg of 6B saccharide, 51 mcg CRM197 carrier protein, 100 mcg polysorbate 80, 295 mcg succinic acid, 4.4 mg sodium chloride, and 125 mcg aluminum as aluminum phosphate adjuvant and water for injection |

Route of administration |

Intramuscular or subcutaneous injection |

Intramuscular injection |

Intramuscular injection |

Intramuscular injection |

Intramuscular injection |

Storage Requirements |

Multi-dose vial. |

Single-dose prefilled syringe. Refrigerate at 2°C to 8°C. Do not freeze. Store in original package. |

Single-dose prefilled syringe. Refrigerate at 2°C to 8°C. Do not freeze. Store in original package. |

Single-dose prefilled syringe. Refrigerate at 2°C to 8°C. Do not freeze. Protect from light. Administer as soon as possible after being removed from the refrigerator. |

Single-dose pre-filled syringe. Refrigerate at 2°C to 8°C. Do not freeze. Store horizontally in original package. |

A comparison of serotypes included in currently authorized vaccine formulations is provided in Table 3.

| Vaccine | Serotypes in penumonoccal vaccines | |||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 4 | 6B | 9V | 14 | 18C | 19F | 23F | 5 | 7F | 3 | 6A | 19A | 22F | 33F | 8 | 10A | 11A | 12F | 15B | 2 | 9N | 17F | 20 | |

| PNEU-C-10 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N |

| PNEU-C-13 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N |

| PNEU-C-15 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N |

| PNEU-C-20 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | N | N |

| PNEU-C-23 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y |

| Abbreviations: Y: yes; N: no | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

Evidence summary

Burden of disease

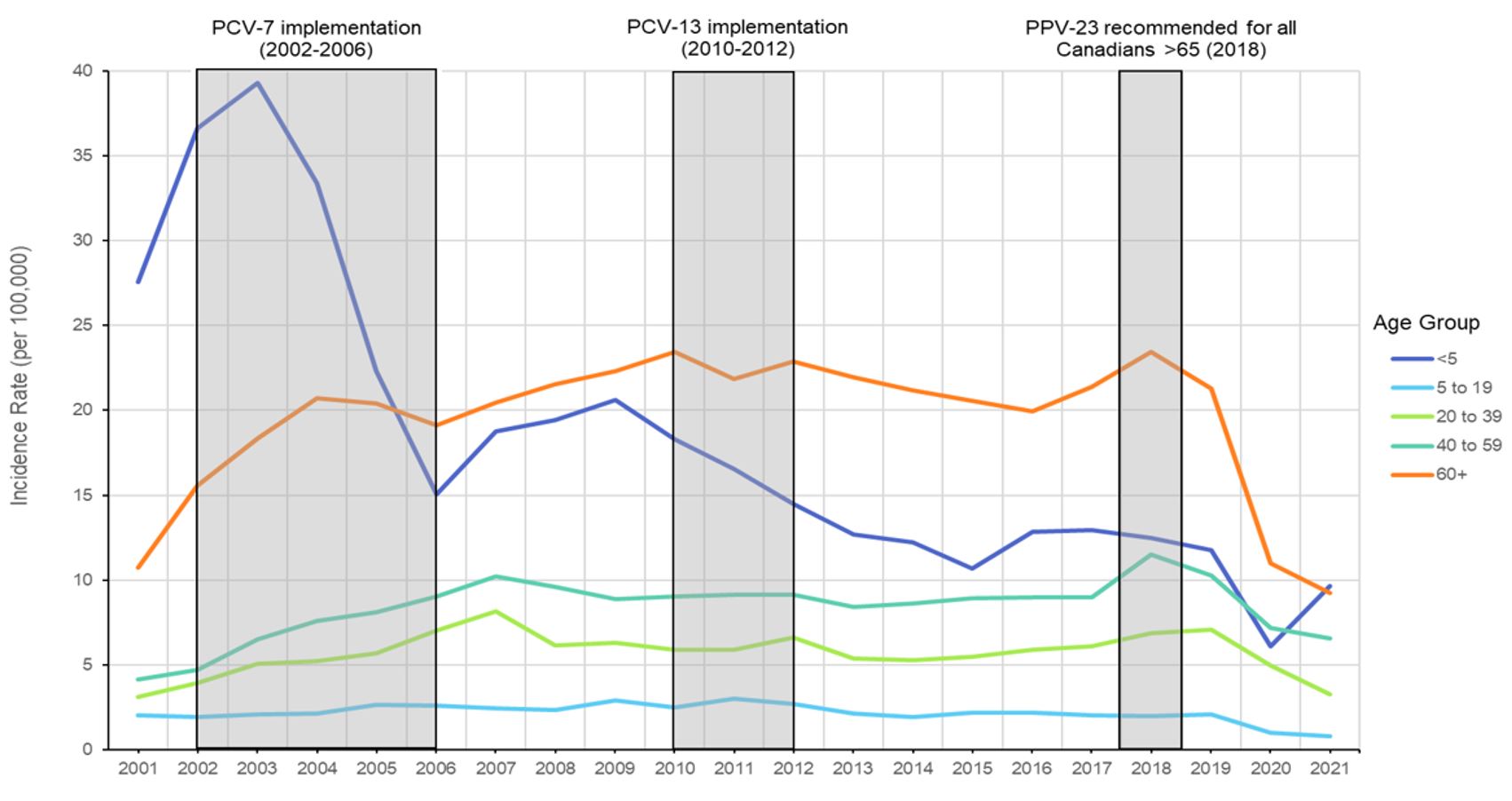

IPD incidence rates by age group

Following the implementation of Pneu-C programs in Canada, between 2001 and 2021, there was an approximately 65% reduction in overall IPD incidence in children under five years of age. Although Pneu-C-7 vaccine had the largest impact on IPD incidence in the under-five age group, further decreases in this age group were observed with the switch to Pneu-C-13 in 2010. Since 2015, when the reported IPD incidence rate in children under five years of age reached 10.7 (95% CI: 9.3-12.2) cases per 100,000 population, the IPD in this age group has remained stable, with the exception being a decrease in the IPD incidence rate in 2020 (IR: 6.1, 95% CI: 5.0-7.3) during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic. In contrast, since the introduction of Pneu-C programs, the IPD incidence in individuals 5 to 19 has remained low and relatively stable (Figure 1). Between 2014 and 2021, there have been, on average, 214 cases of IPD reported annually for children under five years of age (164 cases per year in the 1-to-4-year age group), and 108 cases per year in the 5- to 19-year-old age group.

Figure 1: Text description

A line graph displaying the incidence rate of invasive pneumococcal disease each year from 2001 to 2021, for different age groups including less than 5 years of age, 5 to 19 years of age, 20 to 39 years of age, 40 to 59 years of age, and 60 years of age and older, and highlighting the dates of implementation of Pneu-C-7, Pneu-C-13, and Pneu-P-23 in Canada.

| Year | Less than 1 | 1 to 4 | 5 to 9 | 10 to 14 | 15 to 19 | 20 to 24 | 25 to 29 | 30 to 39 | 40 to 59 | 60 and over |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2001 | 37.8 | 25.2 | 3.6 | 1.1 | 1.5 | 1.6 | 1.8 | 2.5 | 4.1 | 10.8 |

| 2002 | 50.0 | 33.5 | 3.2 | 1.6 | 1.2 | 1.6 | 2.1 | 3.5 | 4.7 | 15.6 |

| 2003 | 54.5 | 35.6 | 4.4 | 1.2 | 1.0 | 1.4 | 3.0 | 4.7 | 6.5 | 18.3 |

| 2004 | 42.9 | 31.0 | 4.3 | 1.2 | 1.3 | 1.6 | 2.8 | 4.9 | 7.6 | 20.7 |

| 2005 | 25.9 | 21.4 | 5.3 | 1.8 | 1.3 | 2.6 | 3.2 | 5.0 | 8.1 | 20.4 |

| 2006 | 20.3 | 13.7 | 4.6 | 1.8 | 1.8 | 2.0 | 3.8 | 6.8 | 9.0 | 19.1 |

| 2007 | 30.3 | 15.8 | 3.4 | 1.9 | 2.1 | 3.4 | 4.5 | 7.1 | 10.2 | 20.5 |

| 2008 | 29.8 | 16.7 | 4.6 | 1.4 | 1.4 | 2.7 | 3.5 | 5.2 | 9.6 | 21.6 |

| 2009 | 27.8 | 18.7 | 5.8 | 1.6 | 1.8 | 2.4 | 3.5 | 5.5 | 8.9 | 22.3 |

| 2010 | 25.1 | 16.5 | 4.8 | 1.8 | 1.3 | 1.9 | 3.1 | 5.2 | 9.0 | 23.4 |

| 2011 | 20.7 | 15.5 | 5.3 | 2.5 | 1.7 | 1.4 | 3.1 | 5.4 | 9.2 | 21.8 |

| 2012 | 18.3 | 13.6 | 4.3 | 2.5 | 1.6 | 2.5 | 4.0 | 5.1 | 9.2 | 22.9 |

| 2013 | 18.7 | 11.2 | 3.8 | 1.5 | 1.3 | 1.5 | 2.8 | 4.6 | 8.4 | 21.9 |

| 2014 | 17.6 | 10.9 | 3.7 | 1.1 | 1.0 | 1.7 | 2.6 | 4.4 | 8.6 | 21.2 |

| 2015 | 14.4 | 9.8 | 3.9 | 1.2 | 1.5 | 1.9 | 2.8 | 4.5 | 8.9 | 20.6 |

| 2016 | 15.7 | 12.1 | 3.6 | 1.3 | 1.7 | 2.3 | 2.6 | 4.8 | 9.0 | 20.0 |

| 2017 | 15.6 | 12.3 | 3.5 | 1.2 | 1.4 | 1.5 | 2.8 | 5.3 | 9.0 | 21.4 |

| 2018 | 12.0 | 12.6 | 3.7 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.6 | 3.6 | 5.7 | 11.5 | 23.4 |

| 2019 | 13.4 | 11.3 | 3.8 | 1.2 | 1.3 | 2.1 | 2.8 | 6.0 | 10.3 | 21.3 |

| 2020 | 6.0 | 6.1 | 1.7 | 0.5 | 0.8 | 1.5 | 2.5 | 3.9 | 7.2 | 11.0 |

| 2021 | 10.3 | 9.5 | 1.5 | 0.4 | 0.6 | 2.0 | 2.5 | 4.2 | 6.6 | 9.3 |

Data Source: CNDSS

IPD incidence rates by geographic region

Differences in IPD incidence rates are also observed geographically. When compared to those reported for the rest of Canada, the incidence rates of IPD in Northern Canada have been higher across age groups, and particularly in children less than one year of age (incidence rate ratio of 5.9 [95% CI: 4.7-7.5]). Outside of Northern Canada, the incidence rates in 5- to 19-year-old age groups have consistently remained below 5 cases per 100,000 population between 2001 and 2021 (Table 4).

| Age group (years) | IR Northern Canada | IR Rest of Canada | IRR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Less than 1 | 133.0 | 22.6 | 5.9 (4.7-7.5) |

| 1-4 | 36.7 | 16.0 | 2.3 (1.8-2.9) |

| 5-9 | 10.9 | 3.9 | 2.8 (1.9-4.0) |

| 10-14 | 2.8 | 1.4 | 1.9 (0.9-4.1)Footnote b |

| 15-19 | 6.1 | 1.4 | 4.4 (2.6-7.3) |

|

|||

IPD reporting according to vaccine serotypes

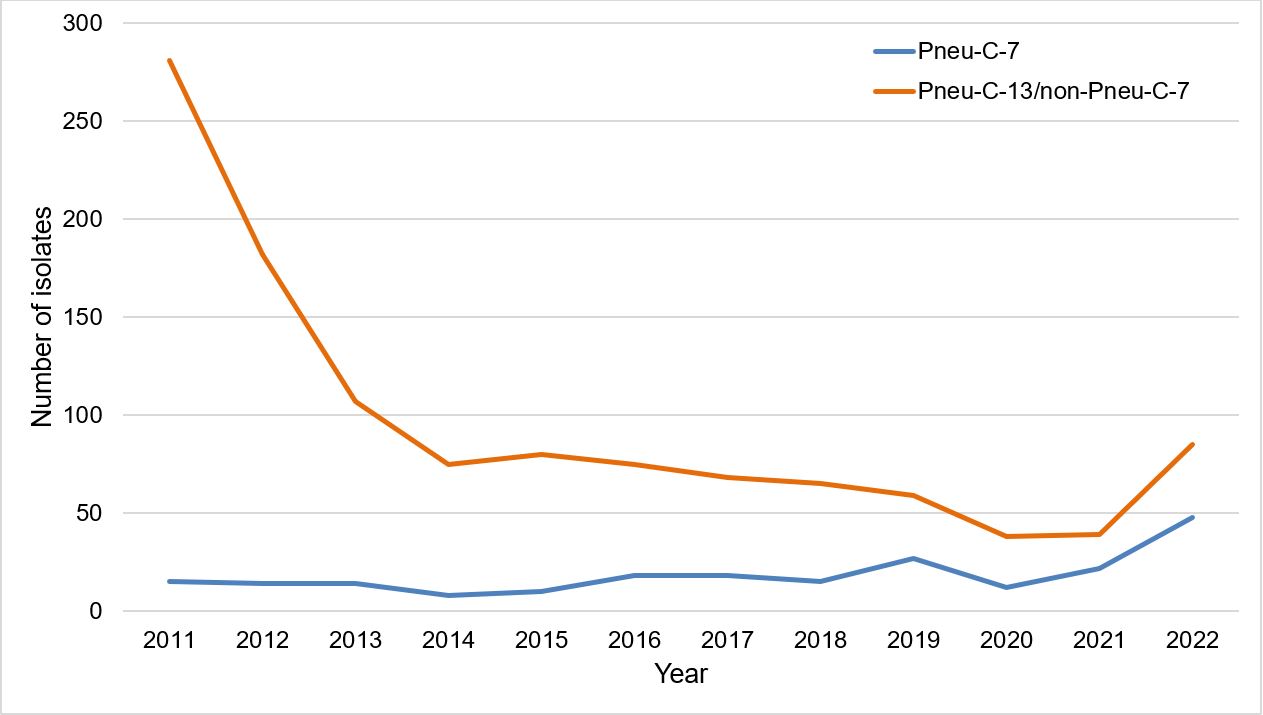

Excluding a slight increase in 2022, the number of isolates caused by Pneu-C-7 vaccine serotypes has remained relatively stable following the introduction of Pneu-C-13 into routine pediatric programs despite the approximately 25% lower GMC IgG concentrations that were reported in the Pneu-C-7/Pneu-C-13 clinical trials for the shared antigens (although seroresponse rates were similar) [Figure 2]Footnote 9.

Figure 2: Text description

A line graph displaying the number of Streptococcus pneumoniae isolates collected each year from 2011 to 2022, for Pneu-C-7 serotypes and Pneu-C-13/non-Pneu-C-7 serotypes.

| Year | Number of isolates of: | |

|---|---|---|

| Pneu-C-7 serotypes | Pneu-C-13/non-Pneu-C-7 serotypes | |

| 2011 | 15 | 281 |

| 2012 | 14 | 182 |

| 2013 | 14 | 107 |

| 2014 | 8 | 75 |

| 2015 | 10 | 80 |

| 2016 | 18 | 75 |

| 2017 | 18 | 68 |

| 2018 | 15 | 65 |

| 2019 | 27 | 59 |

| 2020 | 12 | 38 |

| 2021 | 22 | 39 |

| 2022 | 48 | 85 |

Data Source: National Laboratory Surveillance of IPD in Canada (eSTREP); NML. Preliminary data for 2021 and 2022.

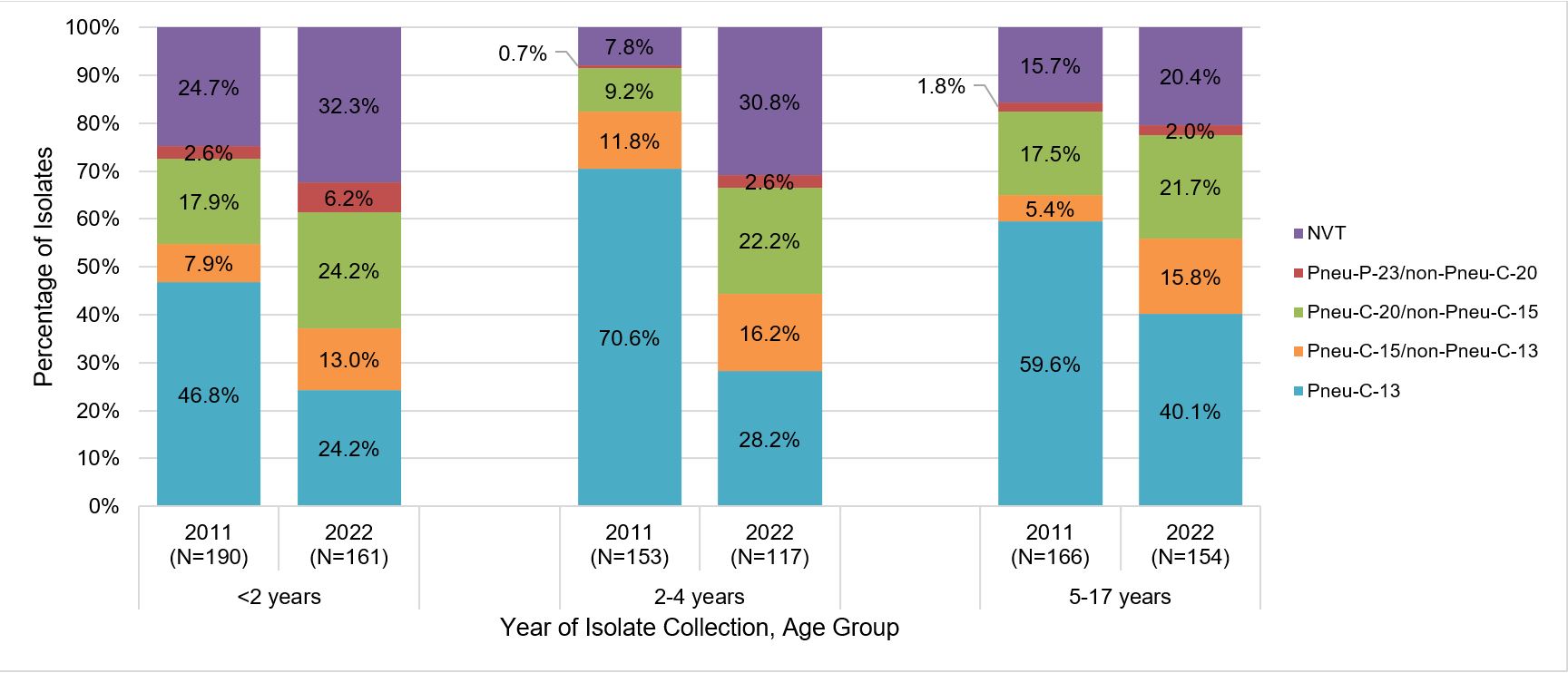

Following the introduction of Pneu-C-13 vaccine into routine pediatric immunization programs, there has been a generally decreasing trend in the proportion of pediatric IPD isolates due to vaccine serotypes, from approximately 58% in 2011 to 31% in 2022. However, the proportion of non-Pneu-C-13 vaccine serotypes has increased from 2011 to 2022. In children less than 18 years of age, the largest increases in vaccine serotypes were observed for Pneu-C-20/non-Pneu-C-15 serotypes (from 15.1% to 22.8%), followed by Pneu-C-15/non-Pneu-C-13 serotypes (from 8.3% to 14.9%) and Pneu-P-23/non-Pneu-C-20 serotypes (from 1.8% to 4.4%); the proportion of IPD isolates caused by non-vaccine type (NVT) serotypes increased from approximately 17% to 28%. Figure 3 provides information by age group.

Figure 3: Text description

A stacked bar graph displaying the percentage of Streptococcus pneumoniae isolates collected from each vaccine category (PNEU-C-13, PNEU-C-15/non-PNEU-C-13, PNEU-C-20/non-PNEU-C-15, PNEU-P-23/non-PNEU-C-20 and other non-vaccine serotypes) in 2011 compared to 2022, for different pediatric age groups: <2 years, 2-4 years and 5-17 years of age.

| Age group | Year | Vaccine (%, N) | Total | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PNEU-C-13 | PNEU-C-15/ non-PNEU-C-13 |

PNEU-C-20/ non-PNEU-C-15 |

PNEU-P-23/ non-PNEU-C-20 |

NVT | ||||||||

| Less than 2 years | 2011 | 46.8% | (89) | 7.9% | (15) | 17.9% | (34) | 2.6% | (5) | 24.7% | (47) | 190 |

| 2022 | 24.2% | (39) | 13.0% | (21) | 24.2% | (39) | 6.2% | (10) | 32.3% | (52) | 161 | |

| 2 to 4 years | 2011 | 70.6% | (108) | 11.8% | (18) | 9.2% | (14) | 0.7% | (1) | 7.8% | (12) | 153 |

| 2022 | 28.2% | (33) | 16.2% | (19) | 22.2% | (26) | 2.6% | (3) | 30.8% | (36) | 117 | |

| 5 to 17 years | 2011 | 59.6% | (99) | 5.4% | (9) | 17.5% | (29) | 1.8% | (3) | 15.7% | (26) | 166 |

| 2022 | 40.1% | (61) | 15.8% | (24) | 21.7% | (33) | 2.0% | (3) | 20.4% | (31) | 154 | |

Data Source: National Laboratory Surveillance of IPD in Canada (eSTREP); NML. Preliminary data for 2021 and 2022.

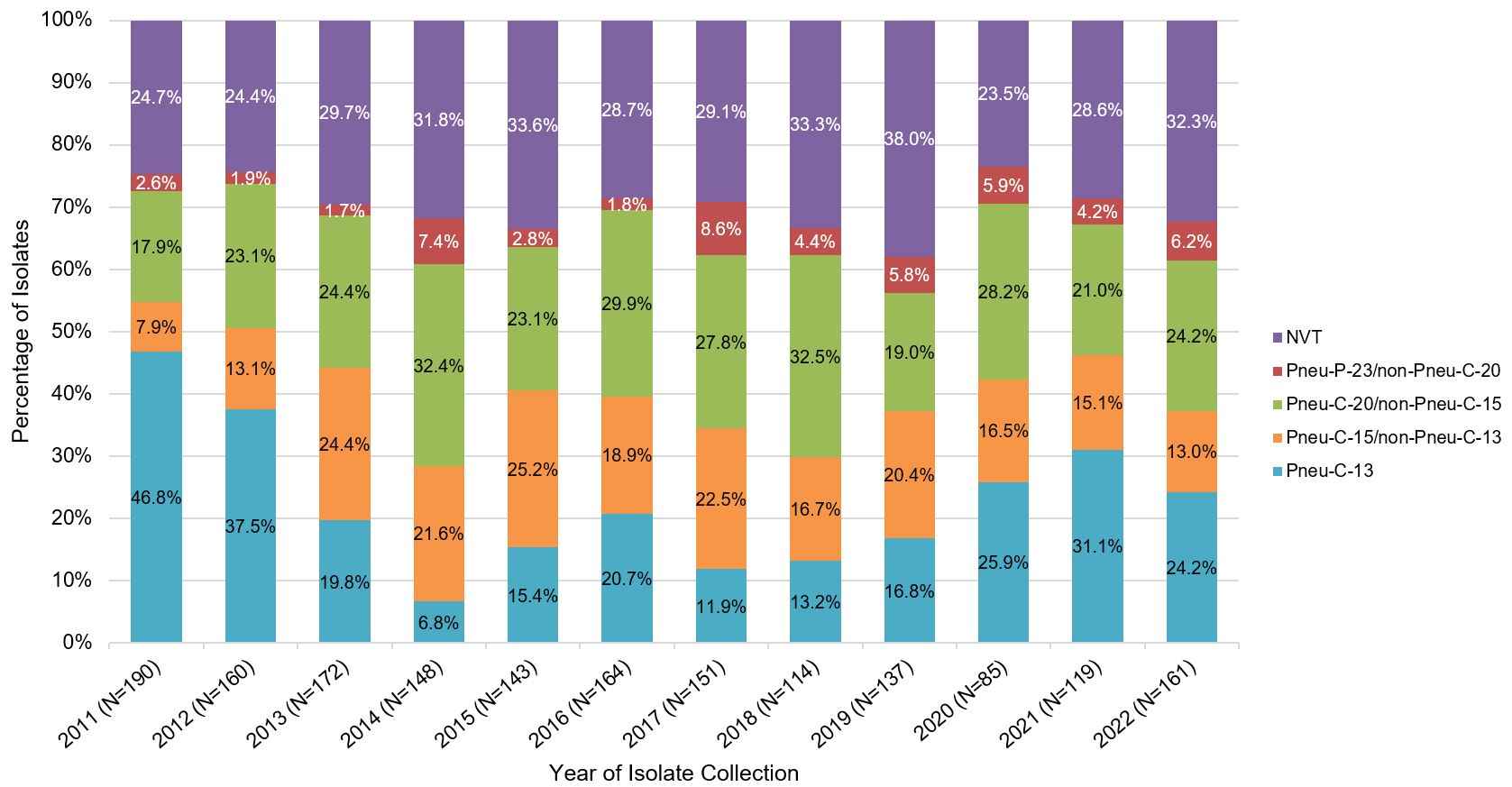

In children less than 2 years of age, apart from a slight increase in 19F and 19A serotype isolates, there was an overall decrease in the proportion of isolates caused by Pneu-C-13 serotypes from 2011 to 2014, after which the proportion stabilized (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Text description

A stacked bar graph displaying the percentage of Streptococcus pneumoniae isolates collected from each vaccine category (PNEU-C-13, PNEU-C-15/non-PNEU-C-13, PNEU-C-20/non-PNEU-C-15, PNEU-P-23/non-PNEU-C-20 and other non-vaccine serotypes), for children <2 years of age in 2011 to 2022.

| Year | Vaccine (%, N) | Total | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PNEU-C-13 | PNEU-C-15/ non-PNEU-C-13 |

PNEU-C-20/ non-PNEU-C-15 |

PNEU-P-23/ non-PNEU-C-20 |

NVT | |||||||

| 2011 | 46.8% | (89) | 7.9% | (15) | 17.9% | (34) | 2.6% | (5) | 24.7% | (47) | 190 |

| 2012 | 37.5% | (60) | 13.1% | (21) | 23.1% | (37) | 1.9% | (3) | 24.4% | (39) | 160 |

| 2013 | 19.8% | (34) | 24.4% | (42) | 24.4% | (42) | 1.7% | (3) | 29.7% | (51) | 172 |

| 2014 | 6.8% | (10) | 21.6% | (32) | 32.4% | (48) | 7.4% | (11) | 31.8% | (47) | 148 |

| 2015 | 15.4% | (22) | 25.2% | (36) | 23.1% | (33) | 2.8% | (4) | 33.6% | (48) | 143 |

| 2016 | 20.7% | (34) | 18.9% | (31) | 29.9% | (49) | 1.8% | (3) | 28.7% | (47) | 164 |

| 2017 | 11.9% | (18) | 22.5% | (34) | 27.8% | (42) | 8.6% | (13) | 29.1% | (44) | 151 |

| 2018 | 13.2% | (15) | 16.7% | (19) | 32.5% | (37) | 4.4% | (5) | 33.3% | (38) | 114 |

| 2019 | 16.8% | (23) | 20.4% | (28) | 19.0% | (26) | 5.8% | (8) | 38.0% | (52) | 137 |

| 2020 | 25.9% | (22) | 16.5% | (14) | 28.2% | (24) | 5.9% | (5) | 23.5% | (20) | 85 |

| 2021 | 31.1% | (37) | 15.1% | (18) | 21.0% | (25) | 4.2% | (5) | 28.6% | (34) | 119 |

| 2022 | 24.2% | (39) | 13.0% | (21) | 24.2% | (39) | 6.2% | (10) | 32.3% | (52) | 161 |

Data Source: National Laboratory Surveillance of IPD in Canada (eSTREP); NML. Preliminary data for 2021 and 2022.

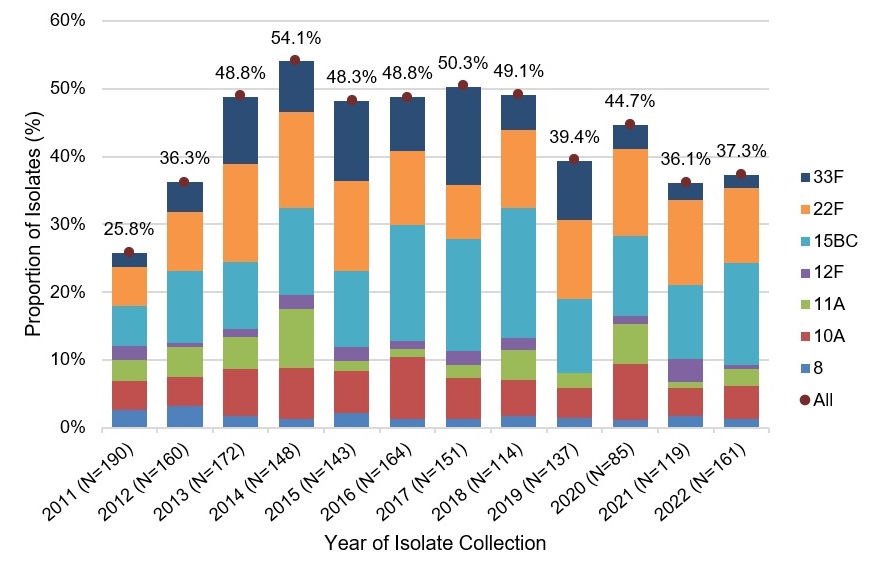

In contrast, the proportion of Pneu-C-20 unique serotypes has increased in children less than 2 years of age, from 25.8% in 2011 to 37.3% in 2022. In 2022, the two additional serotypes contained in Pneu-C-15 would have potentially prevented an additional 13% of IPD cases in children less than 2 years of age, while the 7 additional serotypes contained in Pneu-C-20 would have potentially prevented approximately 37% of additional IPD cases in this age group (Figure 5).

Figure 5: Text description

A stacked bar graph displaying the percentage of Streptococcus pneumoniae isolates collected of each Pneu-C-15/non-Pneu-C-13 (22F and 33F) and Pneu-C-20/non-Pneu-C-15 (8, 10A, 11A, 12F and 15B/C) serotype, including a total combined percentage of all seven serotypes, for children <2 years of age in 2011 to 2022.

| Year(n) | Serotype(%, n) | Combined total (%,n) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PNEU-C-15/non-PNEU-C-13 | PNEU-C-20/non-PNEU-C-15 | ||||||||||||||

| 22F | 33F | 8 | 10A | 11A | 12F | 15BC | |||||||||

| 2011 (190) | 5.8% | (11) | 2.1% | (4) | 2.6% | (5) | 4.2% | (8) | 3.2% | (6) | 2.1% | (4) | 5.8% | (11) | 25.8% (49) |

| 2012 (160) | 8.8% | (14) | 4.4% | (7) | 3.1% | (5) | 4.4% | (7) | 4.4% | (7) | 0.6% | (1) | 10.6% | (17) | 36.3% (58) |

| 2013 (172) | 14.5% | (25) | 9.9% | (17) | 1.7% | (3) | 7.0% | (12) | 4.7% | (8) | 1.2% | (2) | 9.9% | (17) | 48.8% (84) |

| 2014 (148) | 14.2% | (21) | 7.4% | (11) | 1.4% | (2) | 7.4% | (11) | 8.8% | (13) | 2.0% | (3) | 12.8% | (19) | 54.1% (80) |

| 2015 (143) | 13.3% | (19) | 11.9% | (17) | 2.1% | (3) | 6.3% | (9) | 1.4% | (2) | 2.1% | (3) | 11.2% | (16) | 48.3% (69) |

| 2016 (164) | 11.0% | (18) | 7.9% | (13) | 1.2% | (2) | 9.1% | (15) | 1.2% | (2) | 1.2% | (2) | 17.1% | (28) | 48.8% (80) |

| 2017 (151) | 7.9% | (12) | 14.6% | (22) | 1.3% | (2) | 6.0% | (9) | 2.0% | (3) | 2.0% | (3) | 16.6% | (25) | 50.3% (76) |

| 2018 (114) | 11.4% | (13) | 5.3% | (6) | 1.8% | (2) | 5.3% | (6) | 4.4% | (5) | 1.8% | (2) | 19.3% | (22) | 49.1% (56) |

| 2019 (137) | 11.7% | (16) | 8.8% | (12) | 1.5% | (2) | 4.4% | (6) | 2.2% | (3) | 0.0% | (0) | 10.9% | (15) | 39.4% (54) |

| 2020 (85) | 12.9% | (11) | 3.5% | (3) | 1.2% | (1) | 8.2% | (7) | 5.9% | (5) | 1.2% | (1) | 11.8% | (10) | 44.7% (38) |

| 2021 (119) | 12.6% | (15) | 2.5% | (3) | 1.7% | (2) | 4.2% | (5) | 0.8% | (1) | 3.4% | (4) | 10.9% | (13) | 36.1% (43) |

| 2022 (161) | 11.2% | (18) | 1.9% | (3) | 1.2% | (2) | 5.0% | (8) | 2.5% | (4) | 0.6% | (1) | 14.9% | (24) | 37.3% (60) |

Data Source: National Laboratory Surveillance of IPD in Canada (eSTREP); NML. Preliminary data for 2021 and 2022.

All/Combined total refers to the total combined percentage of all Pneu-C-15/non-Pneu-C-13 (22F and 33F) and Pneu-C-20/non-Pneu-C-15 serotypes (8, 10A, 11A, 12F and 15B/C).

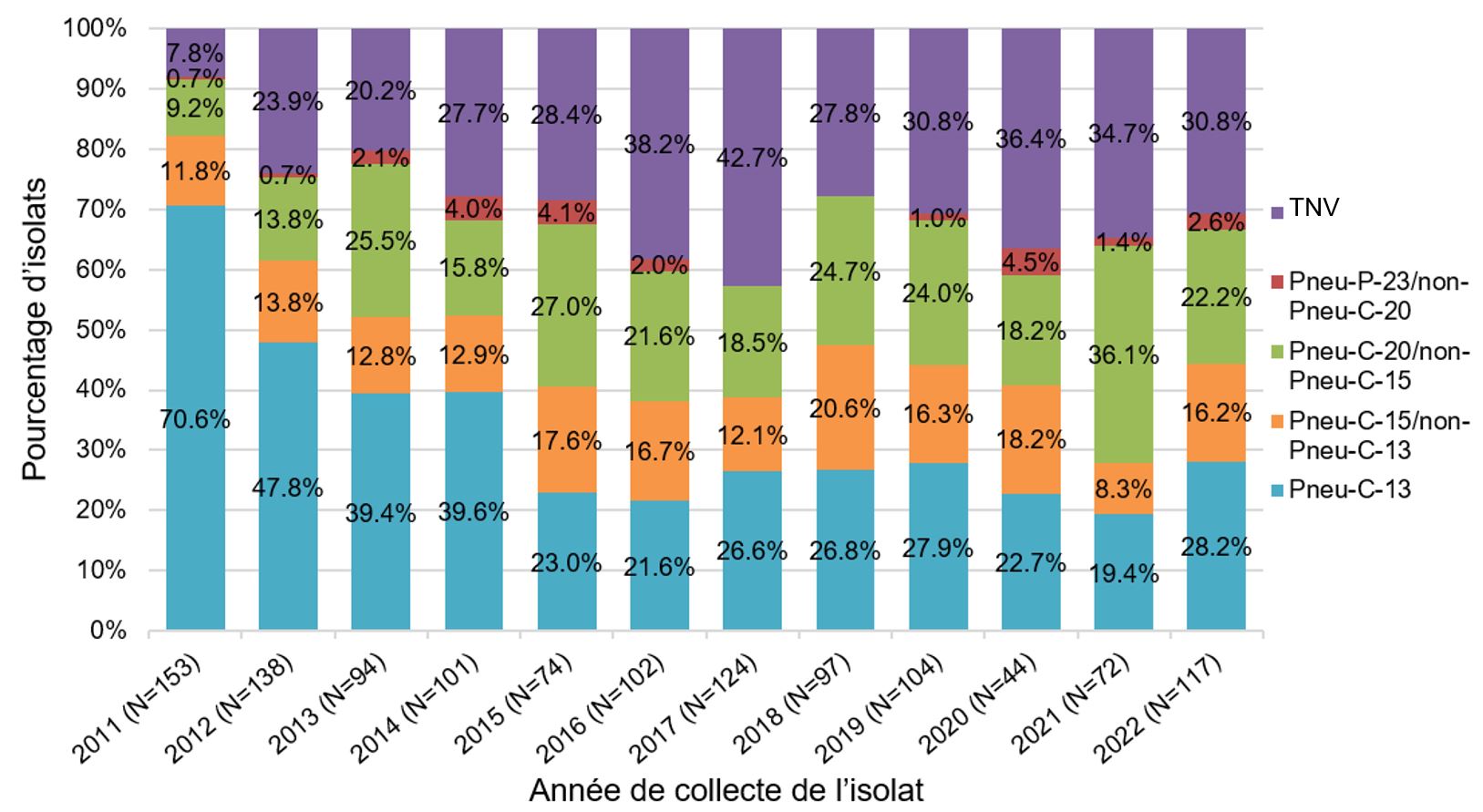

In children 2 to 4 years of age, the proportion of isolates due to the Pneu-C-13 vaccine serotypes has decreased since 2011 from 70.6% to 28.2% in 2022. Similarly, to the under 2-year age group, a more rapid decrease was observed between 2011 to 2014/15, after which the proportion change stabilized. During the same period, an increase was observed in Pneu-C-15/non-Pneu-C-13 and Pneu-C-20/non-Pneu-15 serotypes (from 11.8% to 16.2%, and 9.2% to 22.2%, respectively) [Figure 6 ].

Figure 6: Text description

A stacked bar graph displaying the percentage of Streptococcus pneumoniae isolates collected from each vaccine category (PNEU-C-13, PNEU-C-15/non-PNEU-C-13, PNEU-C-20/non-PNEU-C-15, PNEU-P-23/non-PNEU-C-20 and other non-vaccine serotypes), for children 2 to 4 years of age in 2011 to 2022.

| Year | Vaccine (%, N) | Total | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PNEU-C-13 | PNEU-C-15/ non-PNEU-C-13 |

PNEU-C-20/ non-PNEU-C-15 |

PNEU-P-23/ non-PNEU-C-20 |

NVT | |||||||

| 2011 | 70.6% | (108) | 11.8% | (18) | 9.2% | (14) | 0.7% | (1) | 7.8% | (12) | 153 |

| 2012 | 47.8% | (66) | 13.8% | (19) | 13.8% | (19) | 0.7% | (1) | 23.9% | (33) | 138 |

| 2013 | 39.4% | (37) | 12.8% | (12) | 25.5% | (24) | 2.1% | (2) | 20.2% | (19) | 94 |

| 2014 | 39.6% | (40) | 12.9% | (13) | 15.8% | (16) | 4.0% | (4) | 27.7% | (28) | 101 |

| 2015 | 23.0% | (17) | 17.6% | (13) | 27.0% | (20) | 4.1% | (3) | 28.4% | (21) | 74 |

| 2016 | 21.6% | (22) | 16.7% | (17) | 21.6% | (22) | 2.0% | (2) | 38.2% | (39) | 102 |

| 2017 | 26.6% | (33) | 12.1% | (15) | 18.5% | (23) | 0.0% | (0) | 42.7% | (53) | 124 |

| 2018 | 26.8% | (26) | 20.6% | (20) | 24.7% | (24) | 0.0% | (0) | 27.8% | (27) | 97 |

| 2019 | 27.9% | (29) | 16.3% | (17) | 24.0% | (25) | 1.0% | (1) | 30.8% | (32) | 104 |

| 2020 | 22.7% | (10) | 18.2% | (8) | 18.2% | (8) | 4.5% | (2) | 36.4% | (16) | 44 |

| 2021 | 19.4% | (14) | 8.3% | (6) | 36.1% | (26) | 1.4% | (1) | 34.7% | (25) | 72 |

| 2022 | 28.2% | (33) | 16.2% | (19) | 22.2% | (26) | 2.6% | (3) | 30.8% | (36) | 117 |

Data Source: National Laboratory Surveillance of IPD in Canada (eSTREP); NML. Preliminary data for 2021 and 2022.

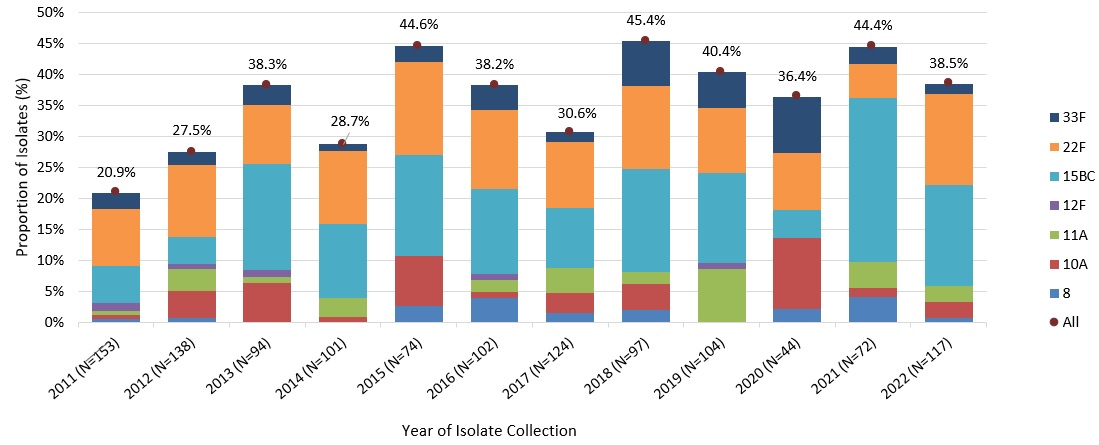

In 2022, the two additional serotypes contained in Pneu-C-15 would have potentially prevented

approximately 16% of additional IPD cases in children 2 to 4 years of age, while the 7 additional serotypes contained in Pneu-C-20 would have potentially prevented approximately 39% of additional IPD cases in this age group (Figure 7).

Figure 7: Text description

A stacked bar graph displaying the percentage of Streptococcus pneumoniae isolates collected of each Pneu-C-15/non-Pneu-C-13 (22F and 33F) and Pneu-C-20/non-Pneu-C-15 (8, 10A, 11A, 12F and 15B/C) serotype, including a total combined percentage of all seven serotypes, for children 2 to 4 years of age in 2011 to 2022.

| Year (n) | Serotype (%, N) | Combined total (%, N) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PNEU-C-15/non-PNEU-C-13 | PNEU-C-20/non-PNEU-C-15 | ||||||||||||||

| 22F | 33F | 8 | 10A | 11A | 12F | 15BC | |||||||||

| 2011 (153) | 9.2% | (14) | 2.6% | (4) | 0.7% | (1) | 0.7% | (1) | 0.7% | (1) | 1.3% | (2) | 5.9% | (9) | 20.9% (32) |

| 2012 (138) | 11.6% | (16) | 2.2% | (3) | 0.7% | (1) | 4.3% | (6) | 3.6% | (5) | 0.7% | (1) | 4.3% | (6) | 27.5% (38) |

| 2013 (94) | 9.6% | (9) | 3.2% | (3) | 0.0% | (0) | 6.4% | (6) | 1.1% | (1) | 1.1% | (1) | 17.0% | (16) | 38.3% (36) |

| 2014 (101) | 11.9% | (12) | 1.0% | (1) | 0.0% | (0) | 1.0% | (1) | 3.0% | (3) | 0.0% | (0) | 11.9% | (12) | 28.7% (29) |

| 2015 (74) | 14.9% | (11) | 2.7% | (2) | 2.7% | (2) | 8.1% | (6) | 0.0% | (0) | 0.0% | (0) | 16.2% | (12) | 44.6% (33) |

| 2016 (102) | 12.7% | (13) | 3.9% | (4) | 3.9% | (4) | 1.0% | (1) | 2.0% | (2) | 1.0% | (1) | 13.7% | (14) | 38.2% (39) |

| 2017 (124) | 10.5% | (13) | 1.6% | (2) | 1.6% | (2) | 3.2% | (4) | 4.0% | (5) | 0.0% | (0) | 9.7% | (12) | 30.6% (38) |

| 2018 (97) | 13.4% | (13) | 7.2% | (7) | 2.1% | (2) | 4.1% | (4) | 2.1% | (2) | 0.0% | (0) | 16.5% | (16) | 45.4% (44) |

| 2019 (104) | 10.6% | (11) | 5.8% | (6) | 0.0% | (0) | 0.0% | (0) | 8.7% | (9) | 1.0% | (1) | 14.4% | (15) | 40.4% (42) |

| 2020 (44) | 9.1% | (4) | 9.1% | (4) | 2.3% | (1) | 11.4% | (5) | 0.0% | (0) | 0.0% | (0) | 4.5% | (2) | 36.4% (16) |

| 2021 (72) | 5.6% | (4) | 2.8% | (2) | 4.2% | (3) | 1.4% | (1) | 4.2% | (3) | 0.0% | (0) | 26.4% | (19) | 44.4% (32) |

| 2022 (117) | 14.5% | (17) | 1.7% | (2) | 0.9% | (1) | 2.6% | (3) | 2.6% | (3) | 0.0% | (0) | 16.2% | (19) | 38.5% (45) |

Data Source: National Laboratory Surveillance of IPD in Canada (eSTREP); NML. Preliminary data for 2021 and 2022.

All/Combined total refers to the total combined percentage of all Pneu-C-15/non-Pneu-C-13 (22F and 33F) and Pneu-C-20/non-Pneu-C-15 serotypes (8, 10A, 11A, 12F and 15B/C).

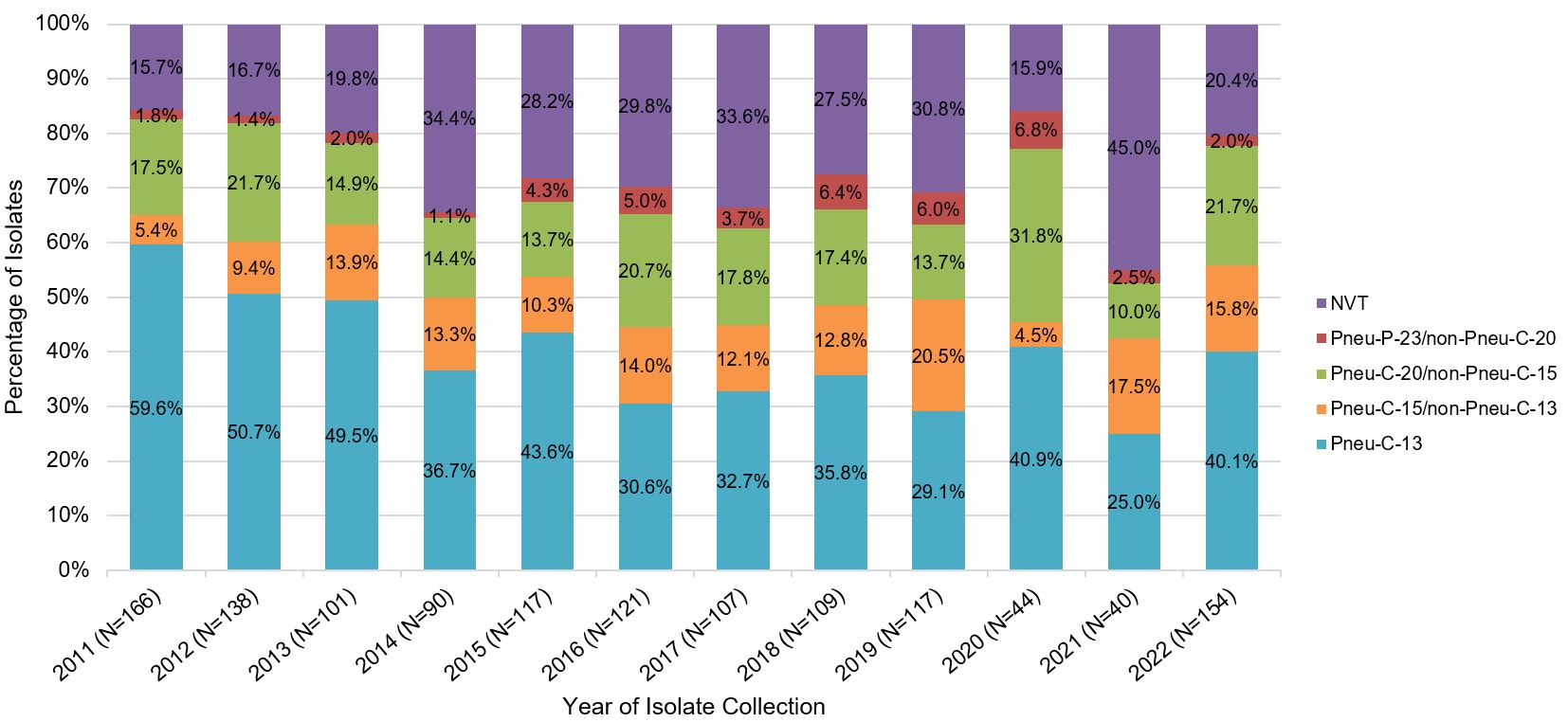

A similar trend has also been observed in the 5- to 17-year-old age group. In 2022, Pneu-C-15/non-Pneu-C-13 and Pneu-C-20/non-Pneu-15 serotypes contributed to approximately 16% and 22% of isolates, respectively (Figure 8).

Figure 8: Text description

A stacked bar graph displaying the percentage of Streptococcus pneumoniae isolates collected from each vaccine category (PNEU-C-13, PNEU-C-15/non-PNEU-C-13, PNEU-C-20/non-PNEU-C-15, PNEU-P-23/non-PNEU-C-20 and other non-vaccine serotypes), for children 5 to 17 years of age in 2011 to 2022.

| Year | Vaccine (%, N) | Total | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PNEU-C-13 | PNEU-C-15/ non-PNEU-C-13 |

PNEU-C-20/ non-PNEU-C-15 |

PNEU-P-23/ non-PNEU-C-20 |

NVT | |||||||

| 2011 | 59.6% | (99) | 5.4% | (9) | 17.5% | (29) | 1.8% | (3) | 15.7% | (26) | 166 |

| 2012 | 50.7% | (70) | 9.4% | (13) | 21.7% | (30) | 1.4% | (2) | 16.7% | (23) | 138 |

| 2013 | 49.5% | (50) | 13.9% | (14) | 14.9% | (15) | 2.0% | (2) | 19.8% | (20) | 101 |

| 2014 | 36.7% | (33) | 13.3% | (12) | 14.4% | (13) | 1.1% | (1) | 34.4% | (31) | 90 |

| 2015 | 43.6% | (51) | 10.3% | (12) | 13.7% | (16) | 4.3% | (5) | 28.2% | (33) | 117 |

| 2016 | 30.6% | (37) | 14.0% | (17) | 20.7% | (25) | 5.0% | (6) | 29.8% | (36) | 121 |

| 2017 | 32.7% | (35) | 12.1% | (13) | 17.8% | (19) | 3.7% | (4) | 33.6% | (36) | 107 |

| 2018 | 35.8% | (39) | 12.8% | (14) | 17.4% | (19) | 6.4% | (7) | 27.5% | (30) | 109 |

| 2019 | 29.1% | (34) | 20.5% | (24) | 13.7% | (16) | 6.0% | (7) | 30.8% | (36) | 117 |

| 2020 | 40.9% | (18) | 4.5% | (2) | 31.8% | (14) | 6.8% | (3) | 15.9% | (7) | 44 |

| 2021 | 25.0% | (10) | 17.5% | (7) | 10.0% | (4) | 2.5% | (1) | 45.0% | (18) | 40 |

| 2022 | 40.1% | (61) | 15.8% | (24) | 21.7% | (33) | 2.0% | (3) | 20.4% | (31) | 154 |

Data Source: National Laboratory Surveillance of IPD in Canada (eSTREP); National Microbiology Laboratory. Preliminary data for 2021 and 2022.

Between 2018 and 2022, the conjugate-vaccine serotypes that were the most common cause of IPD in children were ST22F, ST15B/C, ST19A and 3 which represented, on average, approximately 12%, 12%, 9% and 8% of all isolates collected per year, respectively (National Laboratory Surveillance of IPD in Canada (eSTREP); NML).

IPD incidence in children at increased risk of IPD due to underlying medical conditions

Data on the risk of pneumococcal disease in the pediatric population in the pneumococcal conjugate vaccine era is available from the US. Even with widespread use of pneumococcal conjugate vaccines, from the period 2007 to 2010, children with certain underlying medical conditions continued to demonstrate an increased burden of pneumococcal diseaseFootnote 12, including IPD, pneumococcal pneumonia and all-cause pneumonia. In 2018–2019, approximately 25% of IPD in children 5 to 18 years occurred in children with immunocompromising conditions, cochlear implants, or cerebrospinal fluid leaksFootnote 13.

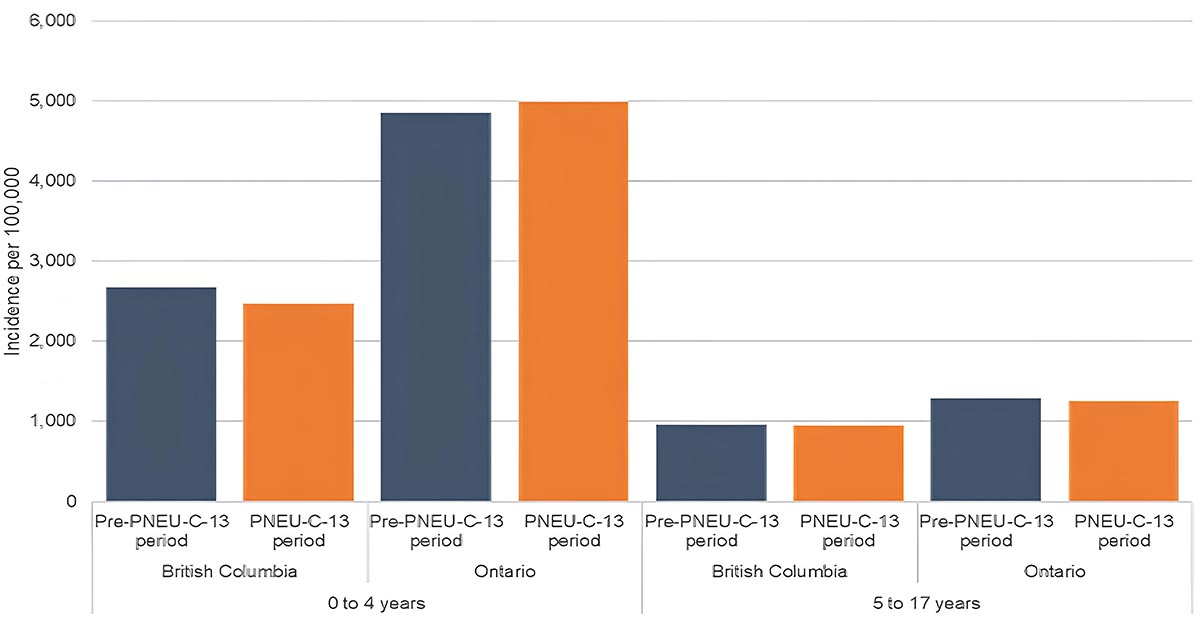

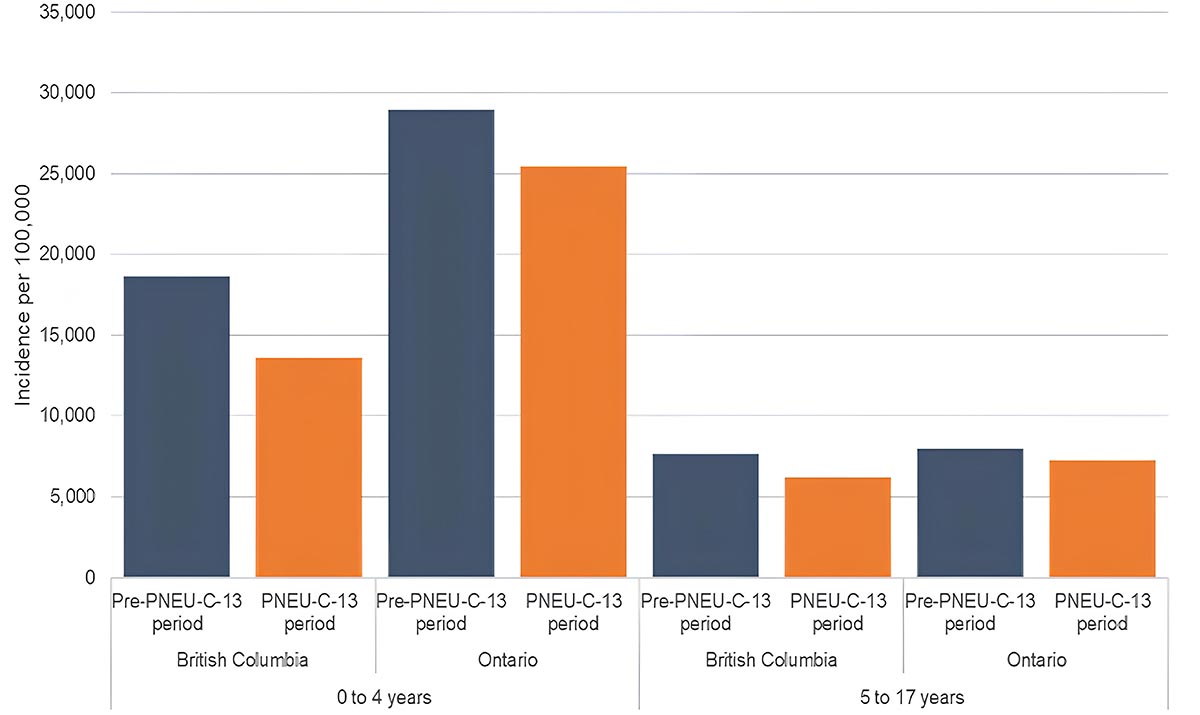

Non-invasive pneumococcal disease burden

National surveillance data on AOM and CAP are not available in Canada, and disease burden estimates are based on provincial health administrative data from British Columbia (BC) and Ontario (ON). The estimated incidence rates for CAP following Pneu-C-13 vaccine programme implementation among children less than 5 years of age ranged from 2,500 per 100,000 (BC) to 5,000 per 100,000 (ON). Among children 5 to 17 years of age, the incidence of CAP ranged from 950 per 100,000 (BC) to 1,250 per 100,000 (ON)Footnote 14. The estimated incidence rates for AOM following Pneu-C-13 vaccine programme implementation among children less than 5 years of age ranged from 14,000 per 100,000 (BC) to 25,000 per 100,000 (ON). Among children 5 to 17 years of age, the incidence of AOM ranged from 6,200 per 100,000 (BC) to 7,200 per 100,000 (ON)Footnote 14. (Figure 9). Overall, following the implementation of the Pneu-C-13 vaccine program, the available data suggests limited changes to non-IPD burden, with a slight decrease in AOM incidence in younger childrenFootnote 14.

International studies show that the proportion of CAP cases attributable to S. pneumoniae was estimated to be 6% in infants under 1 year of age and 12% in children 1 to 15 years of ageFootnote 15Footnote 16. The proportion of AOM cases attributable to S. pneumoniae was estimated to be 17% in childrenFootnote 15Footnote 17. Given the reliance on administrative data and limited studies assessing the proportion of non-invasive CAP and AOM by etiology, there is considerable uncertainty about the proportion of non-invasive CAP and AOM due to S. pneumoniae as well as the relevant serotype distribution in children with these infections when they are caused by S. pneumoniae.

a. Community-acquired pneumonia

Figure 9a: Text description

Age group-specific incidence of CAP (a)

A bar graph displaying the incidence rate of Community Acquired Pneumonia (CAP) in British Columbia (on the far left), and in Ontario (on the left), pre-PNEU-C-13 in blue and following the introduction of PNEU-C-13 period in orange children 4 years old and younger and in British Columbia (on right) and in Ontario (on the far right) for pre PNEU-C-13 period in blue and following the introduction of PNEU-C-13 period for children 5 to 17 years old.

| Age group | Province | Period | Incidence per 100,000 population |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 to 4 years | British Columbia | Pre-PNEU-C-13 period | 18,639.80 |

| 0 to 4 years | British Columbia | PNEU-C-13 period | 13,603.80 |

| 0 to 4 years | Ontario | Pre-PNEU-C-13 period | 28,937.90 |

| 0 to 4 years | Ontario | PNEU-C-13 period | 25,467.60 |

| 5 to 17 years | British Columbia | Pre-PNEU-C-13 period | 7,648.40 |

| 5 to 17 years | British Columbia | PNEU-C-13 period | 6,205.70 |

| 5 to 17 years | Ontario | Pre-PNEU-C-13 period | 7,998.60 |

| 5 to 17 years | Ontario | PNEU-C-13 period | 7,225.90 |

b. Acute otitis media

Figure 9b: Text description

Age group-specific incidence of AOM (b)

A bar graph displaying the incidence rate of Acute Otitis Media (AOM) in British Columbia (on the far left), and in Ontario (on the left), pre-PNEU-C-13 in blue and following the introduction of PNEU-C-13 period in orange children 4 years old and younger and in British Columbia (on right) and in Ontario (on the far right) for pre PNEU-C-13 period in blue and following the introduction of PNEU-C-13 period for children 5 to 17 years old.

| Age group | Province | Period | Incidence per 100,000 population |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 to 4 years | British Columbia | Pre-PNEU-C-13 period | 2,671.60 |

| 0 to 4 years | British Columbia | PNEU-C-13 period | 2,464.10 |

| 0 to 4 years | Ontario | Pre-PNEU-C-13 period | 4,854.20 |

| 0 to 4 years | Ontario | PNEU-C-13 period | 4,991.10 |

| 5 to 17 years | British Columbia | Pre-PNEU-C-13 period | 957.60 |

| 5 to 17 years | British Columbia | PNEU-C-13 period | 945.20 |

| 5 to 17 years | Ontario | Pre-PNEU-C-13 period | 1,289.80 |

| 5 to 17 years | Ontario | PNEU-C-13 period | 1,249.00 |

Figures adapted from Nasreen S et al., 2022Footnote 14.

Immunogenicity, efficacy and safety of Pneu-C-15 and Pneu-C-20 in pediatric populations

There are currently no efficacy or effectiveness data available for Pneu-C-15 or Pneu-C-20 vaccines for any pediatric indication. NACI reviewed the evidence on safety and immunogenicity of Pneu-C-15 vaccine from eight Phase 2/3 clinical trials which included a range of pediatric populations, and which used different vaccine schedules. An additional trial, V114-022, provided information about immunogenicity and safety following the immunization of 14 hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) participants 3 to 17 years of age (with 8 receiving Pneu-C-15)Footnote 18. For the Pneu-C-20 vaccine, data on the safety and immunogenicity was available from five Phase 2/3 clinical trials. Summary of key clinical trial information that was reviewed by NACI is provided in Table 8.

Overall, a comparative analysis of data reported in Pneu-C-15 studies V114-008, V114-025, V114-027 and V114-029Footnote 19Footnote 20Footnote 21Footnote 22, and in Pneu-C-20 studies B7471003, B7471011, B747B1012, and B7471013Footnote 23Footnote 24Footnote 25Footnote 26 showed congruent immune response patterns following vaccination with using either a 2+1 or 3+1 immunization schedule in healthy vaccine-naïve infants (Table 9, Table 10, Table 11, Table 12, Table 13). In addition, there were no differences found in reported adverse events and the overall safety profiles of higher-valent vaccines when compared to Pneu-C-13 (Table 13, Table 14, Table 15).

Immunogenicity

NACI reviewed the available evidence on immunogenicity of Pneu-C-15 and Pneu-C-20 vaccines in the context of routine pediatric immunization programs as well as catch-up and re-immunization schedules. The infant schedules used in the studies included a two dose (provided at 2 and 4 months of age) or three dose (provided at 2, 4 and 6 months of age) priming series followed by an additional dose at 11 to 15 months of age. Studies that evaluated Pneu-C-15 immunogenicity in pre-term infants also used an alternative priming schedule in which the vaccine was provided at 2, 3 and 4 months of age as well as 11-15 months. Immunogenicity was measured one month following dose administration and evaluated post dose 2 (PD2), 3 (PD3) and 4 (PD4). In all infant studies, Pneu-C vaccines were provided concomitantly with other recommended pediatric vaccines.

Immunogenicity of Pneu-C-15 in pediatric populations

Immunogenicity following immunization with Pneu-C-15 was reported in seven Phase 2/3 clinical trials that included healthy children (five studies), children with sickle cell disease (one study) and children with HIV infection (one study) (Table 8).

In the pivotal double-blind clinical trial V114-025Footnote 20 that used a 2+1 vaccination schedule, immunogenicity was measured in healthy infants aged 2 to 15 months who were vaccinated with Pneu-C-13 (n=593) or Pneu-C-15 (n=591). When analyzed according to relative differences in antibody concentrations, lower GMC ratios were observed following dose 2 (PD2) and dose 3 (PD3) with Pneu-C-15 vaccination for the majority of serotypes (9/13 and 11/13, respectively). In Pneu-C-15 recipients, the lowest titres were reported for serotypes 1, 5 and 6A, PD3. Similarly, when assessed by OPA GMT, functional antibodies were lower for 11/13 serotypes PD3 in Pneu-C-15 recipients compared to Pneu-C-13 recipients. However, differences between these vaccines were less pronounced when immunogenicity was reported as seroresponse rate differences, with lower values measured for 3/13 and 6/13 shared serotypes PD2 and PD3, respectively. The patterns of IgG immune responses between doses in this study were generally comparable between the intervention groups, demonstrating significant antibody waning prior to the administration of the booster dose, as well as rapid boosting following the receipt of the booster dose, confirming the presence of immune memory. A summary of GRADE evidence is provided in Table 9.

In three clinical trials that used a 3+1 vaccination schedule (V114-008, V114-027, V114-029)Footnote 19Footnote 21Footnote 22, immunogenicity was assessed in close to 1,400 healthy infant Pneu-C-15 recipients. Lower antibody concentrations were consistently reported after Pneu-C-15 administration for 5/13 shared serotypes PD3 (synthesis of 2 trials) and PD4 (synthesis of 3 trials). Compared to Pneu-C-13, OPA GMT ratios were numerically lower for serotypes 4, 6A, 19A and 23F, PD3 as well as serotypes 1, 3, 5, 6B, 7F and 9V PD4 in Pneu-C-15 recipients (synthesis of 2 trials). There were notable uncertainties regarding the differences in seroresponse rates between groups PD3 and PD4. Similar to what was observed following a two-dose primary schedule, the pattern of antibody waning following the receipt of the primary series was comparable and significant PD3, while PD4 administration immune responses demonstrated a pattern that was conclusive with the establishment of immune memory. A summary of immunogenicity data reported in studies V114-008, V114-025, V114-027 and V114-029 and a summary of GRADE evidence is provided in Table 10.

Mixed schedules

The V114-027 trialFootnote 21 was the only trial that evaluated the immunogenicity of mixed schedules. In this study, 900 healthy participants 40 to 90 days of age were randomized to one of five groups (n=180 per group) to receive a complete four dose series with Pneu-C-13 or Pneu-C- 15, or a mixed regimen initiated with one, two or three doses of Pneu-C-13 and continued with Pneu-C-15.

When assessed by serotype-specific seroresponse rates, a mixed regimen consisting of two or three Pneu-C-15 doses elicited generally comparable immune responses PD3 to those observed after Pneu-C-13 only administration. Similar GMC ratios between a Pneu-C-13-only schedule and a mixed schedule using two doses of Pneu-C-15 were also observed PD3 and PD4. In a mixed schedule with three Pneu-C-15 doses, lower GMC ratios were observed for 4/13 shared serotypes both PD3 and PD4.

As seen with schedules that used only Pneu-C-13 or Pneu-C-15 vaccine, significant antibody waning was observed across all mixed intervention groups PD3, while the fourth dose led to a steep increase in antibody concentrations that were comparable or superior to those observed PD3.

Catch-up vaccination: vaccine-naïve and children with an incomplete Pneu-C series

In the double-blind V114-024 clinical trialFootnote 27, 602 healthy pneumococcal vaccine-naïve children or children who previously received a partial series of a licensed pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (Pneu-C-7, Pneu-C-10 or Pneu-C-13) were randomized to receive an age-appropriate schedule using one to three catch-up doses of either Pneu-C-13 or Pneu-C-15 vaccine. The study stratified children in five groups according to age (7 to 11 months, 12 to 23 months, greater or equal to 2 to less than 6 years, and greater or equal to 6 to 17 years), with all participants less than 2 years of age being Pneu-C vaccine-naïve. In all age groups, serotype-specific antibody concentrations and seroresponse rates at 30 days following the last dose were generally comparable between intervention groups for all common vaccine serotypes and significantly higher for the Pneu-C-15 unique serotypes.

Re-vaccination: children at increased risk of IPD with a completed Pneu-C-13 series

In the V114-023 trialFootnote 28, 99 children 5 to 17 years old with sickle cell disease were randomized in a 2:1 ratio to receive a single dose of either Pneu-C-15 or Pneu-C-13. When assessed by serotype-specific IgG GMCs at 30 days post Pneu-C vaccination, immune responses were generally similar between groups for the shared serotypes and higher for the Pneu-C-15 unique serotypes. Over 75% of Pneu-C-15 recipients achieved greater or equal to 4-fold rise in antibody concentrations for the two unique serotypes whereas only 42% and 58% of vaccine recipients achieved greater or equal to 4-fold rise OPA GMTs for the serotype 33F and 22F, respectively.

In the V114-030 studyFootnote 29, 400 children 6 to 17 years old with HIV were randomized in a 1:1 ratio to receive a single dose of either Pneu-C-15 or Pneu-C-13 vaccine followed by Pneu-P-23 at week 8 post immunization. At 30 days following the administration of Pneu-C-15, IgG GMC were numerically similar for all 13 shared and higher for the two unique serotypes. One month following Pneu-P-23 administration, antibody concentrations were generally similar between groups, although numerically lower for all serotypes compared to those observed one month prior, post Pneu-C administration.

Pre-term infants

An integrated analysis of over 350 pre-term infants who were enrolled in studies V114-025, V114-027, V114-029 and V114-031Footnote 20Footnote 21Footnote 22Footnote 30 demonstrated that, overall, immune responses following Pneu-C-15 vaccination were generally comparable to those observed in pre-term infants receiving Pneu-C-13 for the shared serotypes and consistent with those observed in term infants receiving four doses of Pneu-C-15 vaccine (including IgG GMC and OPA GMT). Over 85% and 96% of pre-term infants receiving Pneu-C-15 achieved seroprotective IgG concentrations of greater or equal to 0.35 μg/mL for each of the vaccine serotypes PD3 and PD4, respectively.

Immunogenicity of Pneu-C-20 in pediatric populations

A pivotal clinical study B7471012Footnote 25 measured immune responses in infants following a 2+1 immunization schedule. The observed IgG antibody concentrations PD2 and PD3 were lower for all common serotypes among Pneu-C-20 recipients compared to Pneu-C-13 recipients. While a lower seroresponse was reported for 9/13 shared serotypes PD2, seroresponse PD3 was only lower for ST3 while for the majority of other shared serotypes (12/13) it was uncertain due to the inclusion of null. The OPA GMTs were generally lower at all time points for the shared serotypes except for ST19A, PD3. A summary of the GRADE assessment is provided in Table 11.

Two clinical trials measured immune responses using a 3+1 infant schedule. In the pivotal B7471011 studyFootnote 24, antibody concentrations were lower for all shared serotypes PD3 and for 12/13 serotypes PD4 compared to Pneu-C-13 recipients. While, similarly, lower seroresponse rates were observed for the majority (8/13) of shared serotypes PD3, there were only 2 shared serotypes (ST1 and ST3) for which lower seroresponse rates were reported PD4. The OPA GMTs were also generally lower for the majority of shared serotypes PD3 and PD4. A very similar pattern of IgG GMC, seroresponse rates and OPA GMTs were also reported PD3 and PD4 in the second, smaller, trial titled B7471003Footnote 23. A summary of GRADE assessment is provided in Table 12.

In all infant studies there was an observed congruency in immune response patterns between intervention groups, independent of the schedule used. There was an observed antibody waning (both for total and functional antibodies) following the completion of the primary series and significant antibody boosting following the receipt of the additional dose. In all studies, one month after the additional dose, antibody levels surpassed those observed after the completion of the primary series, demonstrating the establishment of immune memory in all vaccine recipients.

Re-vaccination: children who completed a routine Pneu-C-13 series

In children 5 to 17 years of age, immunization elicited increases in OPA GMTs for all vaccine serotypes, with the pre/post increase in OPA GMTs for the 7 serotypes not contained in Pneu-C-13 ranging from 11.5 to 499-fold. Immunogenicity data from vaccine-experienced individuals was available from only one study (B7471014)Footnote 31. In this study, 425 children less than 5 years of age previously immunized with greater or equal to 3 doses of Pneu-C-13 and 406 children 5 to 17 years of age (regardless of prior pneumococcal vaccination status) were recruited to receive one dose of Pneu-C-20. Among study participants less than 5 years of age, increases in IgG concentrations were observed for all 20 vaccine contained serotypes with at least 83% achieving predefined IgG concentrations of the 7 additional serotypes, except for serotype 12F (40.0%).

Immunogenicity of routinely administered pediatric vaccines when administered concurrently with Pneu-C-15 or Pneu-C-20

Concurrent administration of Pneu-C-15 or Pneu-C-20 with other routinely administered pediatric vaccines was assessed in all infant clinical trials. In addition to pneumococcal vaccines, participants also received diphtheria, tetanus, pertussis, poliomyelitis (serotypes 1, 2 and 3), hepatitis A, hepatitis B, Haemophilus influenzae type b, measles, mumps, rubella, varicella, and rotavirus vaccines, either as monovalent or combination vaccines. Immune responses to all antigens provided concomitantly with Pneu-C-15 or Pneu-C-20 were similar to those observed in Pneu-C-13 recipients as assessed by the individual antigen-specific response rates (for the combination and monovalent vaccines) or GMT (rotavirus vaccine) at 30 days following the completion of the primary series and the receipt of the additional dose, in both the 2+1 and 3+1 immunization schedule.

Evidence on safety

NACI reviewed the available evidence on safety of Pneu-C-15 and Pneu-C-20 vaccines in the context of routine pediatric immunization programs and catch-up and re-immunization schedules. Evidence on safety was available from clinical trials involving children receiving one or more doses of Pneu-C-15 or Pneu-C-20 vaccine and, in most of the trials, one or more doses of Pneu-C-13 vaccine.

Evidence on safety of Pneu-C-15 in pediatric populations

Adverse events (AE) following immunization with Pneu-C-15 vaccine were reported in eight clinical trials. Overall, 5,399 children received one or more doses of Pneu-C-15 and 3,280 children received one or more doses of Pneu-C-13. The measured safety endpoints included the proportion of participants with solicited local and systemic AEs 1 to 14 days post-vaccination, maximum body temperature measurements 1 to 7 days post-vaccination and serious adverse events (SAEs), up to 6 months following vaccination.

A GRADE assessment of studies that reported safety results for three outcomes of interest (total SAEs, vaccine-related SAEs and death) using 2+1 and 3+1 schedules, concluded that in vaccine-naïve infants there was moderate to high certainty evidence of little to no difference between the Pneu-C-13 and Pneu-C-15 groups (and low to moderate certainty evidence of little to no difference for immunocompromised infants due to small sample size) [Table 13].

A GRADE assessment of studies that reported safety results of additional vaccine doses in vaccine-experienced children concluded that there was moderate certainty evidence of little to no difference between vaccines for all measured safety outcomes (Table 14).

A separate integrated analysis of the final safety database (data from studies V114-025, -027, -029 and -031 that had a similar study design and population) included data from 3,589 healthy infants who received at least one dose of Pneu-C-15 and 2,058 who received at least one dose of Pneu-C-13. Solicited AEs accounted for the majority of reported safety events and were mostly of short duration (3 days or less) and of mild to moderate intensity. The proportions of participants with local and systemic AEs (solicited and unsolicited) after each dose in the primary series, after the booster dose, and after any dose were similar in both intervention groups. In infants, the most frequently reported AEs after any dose of Pneu-C-15 were irritability (range: 47% to 55.1%), somnolence (22.8% to 40.7%), injection-site pain (19.1% to 27.1%), and decreased appetite and other injection-site reactions (less than 20%). In children 11 to 15 months of age, the most frequently reported AEs were irritability (45.7%), somnolence (21.8%), injection-site pain (21%), decreased appetite (19.4%) and other injection-site reactions (erythema, swelling, induration; all less than 22%).

For the majority of participants who received Pneu-C-15, study investigators reported maximum body temperature measurements of less than 38.0 °C, with a temperature distribution that was comparable between intervention groups. Of the participants with a maximum body temperature higher than 38.0 °C, no significant differences were observed between Pneu-C-13 and Pneu-C-15 vaccine recipients after any vaccine dose. SAEs were reported for 10% (n=358) of Pneu-C-15 recipients and 10.5% (n=217) of Pneu-C-13 recipients. While the majority of SAEs were deemed to be non-vaccine related, there were three vaccine-related SAEs reported in 2 participants in the Pneu-C-15 group and 1 participant in the Pneu-C-13 group (all were pyrexia requiring hospitalization). There were 4 deaths (2 in Pneu-C-13 and 2 in Pneu-C-15 recipients), of which none were considered to be related to either of the vaccines.

Pre-term infants

The safety of Pneu-C-15 was assessed in over 170 pre-term infants (gestational age less than 37 weeks) who were immunized using a four-dose schedule. The safety profile following vaccination with Pneu-C-15 was similar to that observed in term infants. The frequency of SAEs was similar between groups (14.9% for Pneu-C-15 and 14.4% for Pneu-C-13). There were no vaccine related SAEs or deaths reported among this small group of pre-term infants.

Evidence on safety of Pneu-C-20 in pediatric populations

Safety data following immunization with Pneu-C-20 vaccine was available from five clinical trials (B7471003, B7471011, B7471012, B7471013, and B7471014)Footnote 23Footnote 24Footnote 25Footnote 26Footnote 31. One (B7471014) was a single-arm trial (n=839) with vaccine-experienced children and was evaluated separatelyFootnote 31. Overall, from the four assessed trials (B7471003, B7471011, B7471012, B7471013)Footnote 23Footnote 24Footnote 25Footnote 26, 2,833 infants received one or more doses of Pneu-C-20 and 2,320 infants received one or more doses of Pneu-C-13. In addition, there were 831 children 15 months through 17 years of age who received at least 1 dose of Pneu-C-20 vaccine. The measured safety endpoints included the proportion of participants with solicited local and systemic AEs 1-7 days post-vaccination (including immediate AEs occurring within 30 minutes post-vaccination), AEs one month after each dose and SAEs up to 6 months following vaccination. A GRADE analysis of studies that reported safety results using 2+1 and 3+1 schedules concluded that there was low to moderate certainty evidence of little to no difference between vaccines for all measured safety outcomes (very low to low among the immunocompromised groups, Table 15).

A separate integrated safety analysis (data from studies B7471003, B7471011, B7471012 and B7471013 that had similar study designs and populations) included data from 2,812 healthy infants who received at least one dose of Pneu-C-20 and 2,299 who received at least one dose of Pneu-C-13Footnote 23Footnote 24Footnote 25Footnote 26. The rates of local reactions and systemic events among infants receiving Pneu-C-20 and Pneu-C-13 after any dose were similar, with the most commonly reported AEs in Pneu-C-20 recipients being irritability (range 59.1% to 71.3%), somnolence (37.0% to 66.5%), injection site pain (33.5% to 46.3%), decreased appetite (22.7% to 26.0%), and other injection site reactions (15.1% to 24.7%). In children 11 to 15 months of age, the most frequently reported AEs in the 3-dose study (B7471012)Footnote 25 and 4-dose studies (B7471003, B7471011, B7471013)Footnote 23Footnote 24Footnote 26 were irritability (58.5% in 3-dose study and 71% in 4-dose studies), somnolence (37.7% and 50.9%), injection-site pain (33.4% and 42.4%), decreased appetite (26.4% and 39.3%), and other injection site reactions (redness or swelling) (15.1% and 36.9%).

For the majority of participants who received Pneu-C-20, study investigators reported maximum body temperature measurements of less than 38.0 °C, with a temperature distribution that was comparable between vaccine groups. Of the participants with a maximum body temperature higher than 38.0°C, no significant differences were observed between Pneu-C-13 and Pneu-C-20 vaccine recipients after any vaccine dose. SAEs were reported for 4.8% of Pneu-C-20 recipients and 4.5% of Pneu-C-13 recipients. While the majority of SAEs were assessed as non-vaccine related, one SAE with onset 7 days after the first vaccine dose was assessed as possibly related to either Pneu-C-20 or one of the concomitant vaccines received. The study participant was hospitalized with fever, painful swelling in the right groin and a right inguinal hernia. Laboratory tests revealed elevated inflammatory markers (C-reactive protein and procalcitonin) and a negative blood culture. The study participant was treated with antibiotics in hospital and the event resolved. There were no deaths reported in any of the Pneu-C-20 pediatric trials.

Pre-term infants

The safety of Pneu-C-20 was assessed in 110 pre-term infants (gestational age greater or equal to 34 to less than 37 weeks) who were immunized with a four-dose schedule (at 2, 4, 6, and 12 to 15 months of age). The safety profile of Pneu-C-20 and Pneu-C-13 was similar to that observed in term infants, including both local reactions and systemic events after each dose. The frequency of AEs reported up to one month post dose 3 was 31.2% for Pneu-C-20 and 23.5% for Pneu-C-13. The frequency of AEs reported up to one month post dose 4 was similar between groups (14.3% for Pneu-C-20 and 17.2% for Pneu-C-13). The percentages of participants with SAEs from Dose 1 to 6 months after Dose 4 were also similar between the two groups (4.4% and 5.6% for Pneu-C-20 and Pneu-C-13 groups, respectively).

Ethics, equity, feasibility and acceptability considerations

NACI uses a published, peer-reviewed framework and evidence-informed tools to ensure that issues related to ethics, equity, feasibility, and acceptability (EEFA) are systematically assessed and integrated into its guidanceFootnote 32.

Infants and children under 5 years of age are at higher risk of IPD compared to children 5 years and age and older and benefit from a routine pneumococcal immunization program. Vaccination of the young pediatric population provides both direct protection and indirect protection to other vulnerable populations (e.g. older adults). Previous recommendations on the use of pneumococcal vaccines in children have also recognized that some groups require additional vaccine doses to provide optimal protection (i.e., the 3+1 vaccine schedule, additional dose with Pneu-P-23), particularly for individuals who may experience decreased immune response due to underlying medical conditions. The continued use of both age- and risk-based vaccine recommendations promotes equitable access to pneumococcal vaccination for those who are most in need of protection.

Children with medical risk factors have been identified as being at increased risk of IPD. Social, environmental, or living conditions can also increase the risk of severe illness and should be considered. The higher disease burden of IPD observed in Northern Canada can be attributed to a variety of intersecting factors, including environmental/living factors (e.g. crowding), the younger age distribution compared to the general Canadian population, and decreased access to health care. Therefore, living in communities or settings experiencing sustained high levels of IPD, or being subject to ongoing risk of IPD due to other environmental or living conditions (i.e., houselessness or residential care) should be identified as risk factors that result in increased risk of IPD. In the case of Indigenous communities, autonomous decisions should be made by Indigenous Peoples with the support of healthcare and public health partners in accordance with the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous PeoplesFootnote 33.

The new higher-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccines offer an opportunity to protect children against additional serotypes compared to Pneu-C-13, and further reduce the burden of IPD. Vaccine coverage of the pediatric pneumococcal vaccines is high in the Canadian population (with an estimated coverage of 85.1% in 2021), and with a routine vaccination program already in place, no change in vaccine uptake is anticipated as a result of the adoption of the higher-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccines.

Conjugate vaccines induce formation of long-term memory cells, provide longer duration of protection, reduce mucosal carriage of bacteria, and have an anamnestic response, in a way that polysaccharide vaccines do not. Therefore, while Pneu-C-20 may not contain as many serotypes as Pneu-P-23, the advantages of a conjugate vaccine outweigh the slightly reduced breadth in serotype coverage. This was considered sufficient to eliminate the need for Pneu-P-23 and would contribute to simplifying the pediatric vaccine schedule, improving program feasibility.

Provinces and territories have previously transitioned from the use of Pneu-C-7 to Pneu-C-13 in pediatric pneumococcal vaccination programs and demonstrated the feasibility of adopting new vaccine products. There will be similar challenges including needing to update communications (e.g. protocols and training, public messaging), minimizing vaccine wastage, and implementing catch-up guidance for specific cohorts. A notable barrier expected in the transition to the use of higher-valent pneumococcal vaccines is the cost of the new vaccines, and there may be variability in how or when each jurisdiction is able to adopt any new recommendations on the use of the higher-valent vaccines. Some jurisdictions may opt to focus on offering the new products initially to certain populations at increased risk of IPD, while others may also factor in local serotype epidemiology in their choice of product. The use of a single product in both routine and high-risk programs for children and adults would reduce program complexity and reduce the chance for administering a different vaccine than intended.

Economics

A systematic review and de novo model-based economic evaluation were used as economic evidence to inform decision-making for the use of Pneu-C-15 and Pneu-C-20 in the pediatric population. Full details, including assumptions and limitations, are provided in a supplementary economic evidence summary.

Systematic review

A systematic search of the peer-reviewed and grey literature identified two model-based economic evaluations comparing Pneu-C-15 to Pneu-C-13 in pediatric populations. Both studies evaluated routine infant programs and did not evaluate vaccination strategies for groups at increased risk for IPD. No studies were identified that included Pneu-C-20 as of March 7, 2023. The studies were conducted in the United States and were cost-utility analyses that used a societal perspectiveFootnote 34Footnote 35. One of the studies was industry sponsoredFootnote 35. Both models were static and did not include transmission dynamics. Indirect protection effects were included as a percent reduction in IPD or all pneumococcal disease in individuals not receiving Pneu-C-15 vaccineFootnote 34Footnote 35. Both models employed a similar approach to model the risk of pneumococcal disease, including IPD, non-bacteremic pneumococcal pneumonia, pneumococcal AOM and long-term post-meningitis sequelae as health outcomes.

Despite differences in perspective used, model type, and time horizon, both studies concluded that Pneu-C-15 use was associated with lower costs and improved health outcomes, dominating Pneu-C-13; however, these analyses assumed that Pneu-C-15 and Pneu-C-13 were priced equivalently in the base caseFootnote 34Footnote 35. In sensitivity analyses, results were robust to alternate assumptions about vaccine effectiveness, coverage, and indirect effects, with Pneu-C-15 remaining the dominant strategy when Pneu-C-15 and Pneu-C-13 were priced equivalentlyFootnote 34Footnote 35. In a threshold analysis, Pneu-C-15 was shown to remain the dominant strategy up to a maximum price per dose that is 18% higher than Pneu-C-13Footnote 35. A catch-up campaign using Pneu-C-15 for all children aged 2 to 5 years who were previously fully vaccinated with Pneu-C-13 was unlikely to be cost-effective, with ICERs exceeding $3.5 million per QALY gainedFootnote 34.

Cost-utility analysis