HIV rapid testing

Download this article as a PDF (697 KB - 12 pages)

Download this article as a PDF (697 KB - 12 pages) Published by: The Public Health Agency of Canada

Issue: Volume 40-18: Blood, cell and tissue transplant surveillance

Date published: November 20, 2014

ISSN: 1481-8531

Submit a manuscript

About CCDR

Browse

Volume 40-18, November 20, 2014: Blood, cell and tissue transplant surveillance

Systematic review

A review of Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) rapid testing

Ha S1*, Foley S1, Paquette D1, Seto J1

Affiliation

1 Centre for Communicable Diseases and Infection Control, Public Health Agency of Canada, Ottawa, ON

Correspondence

DOI

https://doi.org/10.14745/ccdr.v40i18a06

Abstract

Background: In Canada, it is estimated that 71,300 persons were living with HIV at the end of 2011. Approximately 25% (14,500 to 21,500) of prevalent cases were unaware of their HIV infection. Expanded use of HIV rapid tests may increase the detection of undiagnosed infections, enable earlier treatment and support services and prevent the onward transmission of HIV.

Objective: To examine patient acceptability, impact (defined as receipt of test results and linkage to care) and cost-effectiveness of HIV rapid tests.

Methods: A search was conducted for systematic reviews on HIV rapid testing, with studies from both developed and developing countries, published in English and between 2000 and 2013. The Assessment of Multiple Systematic Review (AMSTAR) tool was used to assess the included systematic reviews for methodological quality. Results were summarized narratively for each of the outcomes.

Results: Eight systematic reviews were included. Acceptability of HIV rapid tests was generally high in medical settings (69% to 98%) especially among pregnant women and youth attending emergency rooms but was lower in non-medical settings (14% to 46%). The percentage of people who obtained their test results was variable. It was high (83% to 93%) in emergency rooms but was low in a rapid care setting with regular business hours (27%). Impact on linkage to care was limited. Only one systematic review examined cost-effectiveness of rapid testing and concluded that HIV rapid tests were cost-effective in comparison to traditional methods; however, results were all based on static models.

Conclusion: Overall, HIV rapid tests demonstrated generally high acceptability, variability in receiving test results and limited impact on linkage to care. While these findings suggest that HIV rapid tests may be useful, further research is needed to confirm in whom, when and where they are best used and how to ensure better linkage to care.

Introduction

At the end of 2011, an estimated 71,300 persons were living with Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) and Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (AIDS) in Canada and an estimated 25% were unaware of their HIV status Footnote 1. Those unaware of their status are unable to take advantage of available support services and care, are at increased risk of transmitting HIV and are at increased risk of acquiring other sexually transmitted and blood-borne infections. Effective screening strategies that lead to earlier diagnosis and treatment can contribute to improved individual and population health outcomes Footnote 2.

With the emergence of new diagnostic technologies, there are increasing options for HIV testing. Rapid tests for HIV are available worldwide including oral fluid tests and finger prick tests using whole blood or plasma. HIV rapid tests can be either self-administered or administered by trained staff. In Canada, HIV rapid tests can only be carried out by trained staff in point-of-care (POC) settings (e.g., doctors' offices, clinics, emergency departments) Footnote 3,Footnote 4,Footnote 5. In addition, the Public Health Agency of Canada recommends that HIV rapid tests be administered in conjunction with pre- and post-test counselling Footnote 5.

Only one HIV rapid test is licensed for use in Canada Footnote 6. In October 2005, Health Canada approved the INSTI™ HIV-1 Antibody Test (a single use rapid test for HIV) for use in POC settings. In 2008, the license was amended to include the INSTI™ HIV-1/HIV-2 Antibody Test Footnote 6. This test is a preliminary antibody screening test that can be performed on site where the patient can receive their results immediately (< 1hr) Footnote 7,Footnote 8,Footnote 9,Footnote 10. If the patient receives a preliminary reactive result, a confirmatory test using traditional laboratory-based testing is required. If the test result is negative (non-reactive), no further testing is necessary Footnote 3,Footnote 5.

Previous studies suggest POC testing has the potential to improve the management of infectious diseases by identifying new infections, reducing the numbers of those who are unaware and facilitating linkage to care Footnote 11,Footnote 12. To ensure HIV rapid tests are feasible, they should also be cost-effective. The objective of this rapid review was to examine the most current evidence on patient acceptability, impact (defined as receipt of test results and linkage to care) and cost-effectiveness of HIV rapid tests.

Methods

We followed the Ottawa Hospital Research Institute's methods for conducting rapid reviews Footnote 13. This method is designed to provide decision-makers with a synthesis of an extensive literature in a timely manner Footnote 13. A protocol was developed for the rapid review a priori that included: question development and refinement; a systematic literature search; screening and selection of systematic reviews; assessing the quality of the evidence; and a narrative synthesis of included studies. Footnote 13.

Search strategy

The following databases were searched: Medline, Embase, Scopus, Social Policy and Practice, Proquest Public Health and Google Scholar. Articles were included if they were published between January 2000 and September 2013; included studies from developed or developing countries; and/or published in English. The search strategy included the following key words: ("human immunodeficiency virus" OR "HIV") AND ("Point of care" OR "point-of-care", "rapid test" OR "home-based test" OR "screen*") AND ("linkage to care" OR "follow-up" OR "barrier*", "intervention*" OR "access*" OR "diagnos*") OR ("acceptab*", "willing*", "satisf*", "preference*") OR ("feasib*", "economic*", "financ*", "cost*"). Articles that reported results on HIV prevalence or studies with no mention of HIV rapid testing were excluded from the review.

Quality assessment of the studies

Each systematic review was evaluated using the Assessment of Multiple Systematic Review (AMSTAR) tool for methodological quality Footnote 14. The AMSTAR tool consists of an 11-item questionnaire that assesses the following criteria: use of an a priori design; duplicate study selection and data extraction process; comprehensive literature search; use of publication status as an inclusion criterion; characteristics of included studies; list of included / excluded studies; assessment of the quality of studies; appropriate use of scientific quality in forming conclusions; appropriate methods used to combine study findings; assessment for publication bias; and acknowledgement of conflict of interest. To ensure reliability of the assessment, two of the authors (SH, SF) evaluated the systematic reviews using the AMSTAR tool. Where there was discrepancy, a third person (DP) was invited to assess the criterion in question.

Data extraction

For each of the included systematic reviews, two authors (SH, SF) extracted data on population; search years; number of included studies; locations of included studies; study objective; type of intervention; and outcomes. Outcomes of interest included: acceptability, receipt of HIV test results, linkage to care and cost-effectiveness. After data extraction, both authors compared their findings to ensure consistency.

Results

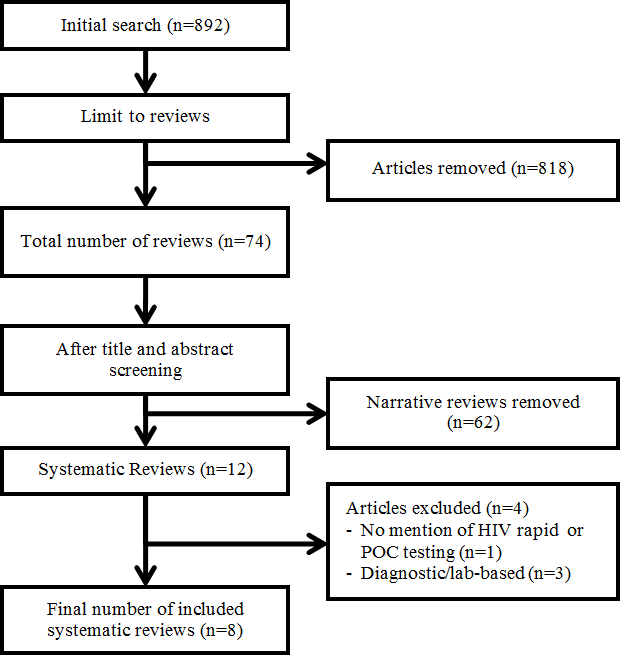

The initial search yielded a total of 892 articles on rapid testing for HIV. After limiting to systematic reviews (n=12), eight review articles met the inclusion criteria (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Algorithm of literature search and study selection of systematic reviews on rapid HIV testing

Text Equivalent - Figure 1

Figure 1 presents a flow diagram of the literature search and study selection process for systematic reviews on rapid HIV testing. The initial search yielded a total of 892 articles. After limiting the search to systematic reviews, 877 articles were removed, resulting in a total of 74 reviews. After title and abstract screening, 62 narratives were removed leaving 12 systematic reviews. Another four studies were excluded; of which, one study had no mention of HIV rapid or POC testing and three studies were diagnostic and/or lab-based. A final number of 8 systematic reviews were included in this rapid review.

A description of the included reviews and the respective AMSTAR score out of 11, are presented in Table 1. Three had perfect AMSTAR scores and another was of high quality (with a score of 8). Reasons for a systematic review having a score less than eight included: it did not specify a duplicate study selection and data extraction process; assessment and documentation of the quality of the studies; or assessment of publication bias.

| Reference | Objective(s) | Population and location | Search period, intervention and number of included studies | AMSTAR score (out of 11) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bateganya (2007) Footnote 17 | To identify and critically appraise studies addressing the implementation of home-based HIV voluntary counselling and testing; to assess the effect of this intervention compared to facility-based HIV counselling and testing. | Population: Adults (>15 years) Location(s): Uganda and Zambia |

Search period: 1980 - 2007 Intervention: Voluntary counselling and testing for HIV No. included studies: 2 |

11 |

| Bateganya (2010) Footnote 8 | To establish the effect of home-based HIV voluntary counselling and testing on uptake of HIV testing. | Population: Adults (>15 years) Location(s): Zambia |

Search period: 2007 - 2008 Intervention: Voluntary counselling and testing for HIV No. included studies: 1 Table 1 - Footnote 1 |

11 |

| Dibosa-Osadolor (2010) Footnote 21 | To review evidence used to derive estimates of cost-effectiveness of HIV screening and to appraise the methodologies of economic studies of HIV screening. | Population: Various Location(s): Not stated |

Search period: 1993 -2008 Intervention: Economic modelling of HIV screening and testing programs No. included studies: 17 |

7 |

| Napierala Mavedzenge (2013) Footnote 18 | To conduct a review of policy and research on HIV self-testing. | Population: Various Location(s): Kenya, Zambia, United States, Singapore, South Africa, Germany, Malawi, Netherlands, United Kingdom, France |

Search period: 1980 - May 2012 Intervention: HIV self-testing No. included studies: 24 |

6 |

| Pant Pai (2007) Footnote 15 | To summarize the overall diagnostic accuracy of rapid HIV tests in pregnancy; evaluate outcomes and impact of testing; and identify practical challenges related to the implementation of voluntary HIV testing and counselling in pregnant women. | Population: Pregnant women (18 to 44 years) Location(s): South Africa, United States, Latin America, South-East Asia, Jamaica |

Search period: 1991 - July 2005 Intervention: HIV POC testing in pregnancy No. included studies: 17 |

8 |

| Pant Pai (2013) Footnote 9 | To review supervised and unsupervised self-testing strategies for HIV. | Population: Various Location(s): United States, Canada, Singapore, India, Malawi, Spain, Kenya, Netherlands |

Search period: January 2000 - October 2012 Intervention: Supervised and unsupervised HIV POC testing No. included studies: 21 |

11 |

| Roberts (2007) Footnote 16 | To review the outcomes of blood and oral fluid rapid HIV testing. | Population: Various Location(s): United States, Kenya, Brazil, Zimbabwe, Burkina Faso, Mexico |

Search period: January 2000 - June 2006 Intervention: HIV rapid testing No. included studies: 26 |

4 |

| Turner (2013) Footnote 19 | To review preferences and acceptability of rapid POC testing in youth, to document notification rates and to identify socio-demographic factors associated with youth choosing rapid HIV POC testing over traditional testing. | Population: Youth (<25 years) Location(s): United States |

Search period: January 1990 - March 2013 Intervention: HIV POC testing No. included studies: 14 |

7 |

Acceptability

Almost all of the reviews (7/8) examined acceptability. Acceptability was defined in these reviews as the population's uptake of a rapid test Footnote 8,Footnote 9,Footnote 15,Footnote 16,Footnote 17 or as the patient's preference for a rapid test when offered the choice of a rapid test or traditional laboratory-based test Footnote 18,Footnote 19.

In the Roberts et al. review, the overall acceptability of rapid tests administered in both medical and community settings ranged from 14% to 98 % Footnote 16. Acceptability of rapid testing was lower (14% to 46%) in alternative testing sites (e.g., bathhouses, needle exchange programs, jails and emergency departments) compared to medical settings (69% to 98%) (e.g., sexually transmitted infection clinics, labour and delivery units and hospitals) Footnote 16. The wide range of acceptance rates may have been affected by differences in the definition of acceptability and in the data collection methods.

In two reviews, acceptability for HIV rapid tests was high among pregnant women Footnote 15,Footnote 16. In the Pant Pai et al. review, acceptability among pregnant women ranged from 83% to 97% Footnote 15. Similarly, in the Roberts et al. review, acceptability among pregnant women ranged from 74% to 86% in American studies and from 93% to 98% in international studies Footnote 16. Among pregnant women, the following factors were associated with high acceptability of HIV rapid testing: age (<21 years), higher education and lack of appropriate prenatal care during pregnancy Footnote 15.

Among the youth, Turner et al. found that 35% to 93% accepted HIV rapid tests when offered. The 35% acceptance rate was found in an adolescent outpatient clinic Footnote 19. However, when given the option of rapid or traditional methods, youth from the adolescent outpatient clinic selected rapid methods 70% of the time Footnote 19. The highest acceptance rates (83% to 93%) were found in emergency rooms suggesting that there is high acceptability for rapid testing among youth attending emergency departments Footnote 19.

In the Mavedzenge et al. review, acceptability was defined as the interest to self-test. Among key populations such as men who have sex with men (MSM) and emergency department attendees, the authors found that acceptability of self-testing was moderate to high (62% to 92%) Footnote 18. Reasons for preferring self-testing included privacy, autonomy, confidentiality, anonymity, convenience and speed.

Pant Pai et al. demonstrated that acceptability (choosing self-testing over the traditional laboratory-based tests) was high in supervised and unsupervised settings Footnote 9. In supervised settings, there was high acceptability (74% to 96%) among emergency department attendees, urban MSM, university students and the general urban population. Of note, an older study from 2001 reported an acceptance rate of 24% among HIV clinic attendees. In unsupervised settings, the high acceptability (74% to 84%) was only based on two studies, which focused on healthcare professionals and HIV negative MSM Footnote 9.

Acceptability of HIV rapid tests was variable across different populations, but was generally high among pregnant women, youth attending emergency rooms and in medical settings. More research is needed to explore self-testing in unsupervised settings and reasons for low acceptance rates in non-medical settings.

Receipt of HIV test results

Four of the eight (4/8) systematic reviews examined the impact of HIV rapid testing on patients' receipt of test results. One systematic review by Roberts et al. noted that 27% to 100% of clients who attended medical and community settings for rapid testing received their HIV test results Footnote 16. The low rate of 27% was when same day results were available in an urgent care clinic with regular business hours and most participants left before the results were available Footnote 20. In the remaining studies, more than 70% of participants who underwent rapid testing at hospitals, sexually transmitted infection clinics, homeless shelters and bathhouses received their test results Footnote 16.

In a review by Bateganya et al., those who received voluntary counselling and testing (with rapid tests) at home were approximately five times more likely to receive their test results compared with those who received voluntary counselling and rapid testing at a clinic Footnote 17. The authors conducted an updated review that included one additional study, and found that 56% of individuals who had the home-based testing received their test results compared to 12% who had clinic-based testing Footnote 8. Based on these findings, receipt of rapid test results tended to be moderate to high except in urgent care clinics with regular business hours.

Linkage to care

Six of the eight (6/8) systematic reviews assessed linkage to care although the definition of linkage to care varied among the reviews. Roberts et al. defined linkage to care as entry into medical care and found this occurred in 47% to 100% of those who were diagnosed with HIV from rapid tests Footnote 16. Mavedzenge et al. defined linkage to care as linkage to prevention, treatment and care services and concluded that data are insufficient to determine whether self-testing leads to timely linkage to care Footnote 18. Dibosa-Osadolor et al. found that rapid HIV testing resulted in a higher percentage of patients being appropriately linked to care compared to traditional HIV testing Footnote 21; however, exact percentages were not listed. Bateganya et al. did not provide a clear definition for linkage to care, but included studies that offered voluntary pre- and post-test counselling at home. Compared to those offered testing and counselling in a clinic, those tested at home were more likely to accept post-test counselling Footnote 17. In the updated review by Bateganya et al., 12% received post-test counselling from a clinic and 56% received post-test counselling at home Footnote 8. Most reviews acknowledged that information on linkage to care was sparse Footnote 9,Footnote 15,Footnote 16.

See Table 2 for a summary of the acceptability, receipt of test results and linkage to care data.

| Reference | Acceptability | Receipt of HIV test results | Linkage to care |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bateganya (2007) Footnote 17 | Those randomized in optional testing locations (including home-based testing) were 4.6 times more likely to accept voluntary counselling and testing than those in the facility arm (RR 4.6 95% CI 3.6-6.2) Footnote 26. | In the year where participants were given the option to receive their HIV test results at home, participants were 5.23 times more likely to receive their results than during the year when results were available only at the facility (OR 5.23 95%CI 4.02-6.8) Footnote 27. | The definition for linkage to care was unclear. It appears that those who received their results also received post-test counselling. |

| Bateganya (2010) Footnote 8 | Acceptability of pre-test counselling and HIV test was 12% vs. 57% (optional group) Footnote 26 | 12% received post-test counselling and their test results from the local clinic; 56% received results and counselling at home (RR 4.7 95%CI 3.62-6.21) Footnote 26. | The definition for linkage to care was unclear. It appears that those who received their results also received post-test counselling. |

| Dibosa-Osadolor (2010) Footnote 21 | N/A | N/A | Antibody rapid testing also resulted in a higher percentage of patients being appropriately linked to care Footnote 28,Footnote 29,Footnote 30,Footnote 31. |

| Napierala Mavedzenge (2013) Footnote 18 | Health workers from African countries had high interest in self-testing 73% to 79% Footnote 32,Footnote 33,Footnote 34. In US studies, emergency department patients and MSM Table 2 - Footnote 2 had high acceptability ranging from 83% to 89% Footnote 35,Footnote 36,Footnote 37. | N/A | Insufficient data. |

| Pant Pai (2007) Footnote 15 | Overall acceptability: 83% to 97% Footnote 38,Footnote 39,Footnote 40,Footnote 41,Footnote 42. No clear consensus on patient preference for method of rapid tests (e.g., blood-based over oral fluid based). |

N/A | Details of linkages to care and prevention were not reported. |

| Pant Pai (2013) Footnote 9 | Overall acceptability: 74% to 96% for both supervised and unsupervised settings Footnote 7,Footnote 35,Footnote 43,Footnote 44,Footnote 45,Footnote 46,Footnote 47,Footnote 48,Footnote 49. Supervised settings: 24% to 95% Footnote 7,Footnote 35,Footnote 43,Footnote 44,Footnote 45,Footnote 46,Footnote 47

|

N/A | Only one study in a US unsupervised setting was reported à 96% of those who test positive for HIV would seek post-test counselling Footnote 50. |

| Roberts (2007) Footnote 16 | Overall acceptability: 14% to 98% Footnote 10,Footnote 39,Footnote 51,Footnote 52,Footnote 53,Footnote 54,Footnote 55,Footnote 56,Footnote 57,Footnote 58,Footnote 59,Footnote 60,Footnote 61,Footnote 62,Footnote 63,Footnote 64.

|

Overall receipt of HIV test results: 27% to 100% Footnote 10,Footnote 20,Footnote 51,Footnote 54,Footnote 55,Footnote 56,Footnote 59,Footnote 63,Footnote 64,Footnote 65,Footnote 66,Footnote 67,Footnote 68,Footnote 69.

|

Overall: 47% to 100% (all US studies) Footnote 20,Footnote 54,Footnote 55,Footnote 65. Few studies examined entry rates into medical care in those who were found to be HIV+ from rapid tests. |

| Turner (2013) Footnote 19 | Overall acceptability: 35% to 93% Footnote 70,Footnote 71,Footnote 72,Footnote 73,Footnote 74,Footnote 75,Footnote 76,Footnote 77,Footnote 78,Footnote 79,Footnote 80. Lowest acceptance rate was found in an adolescent outpatient clinic (35%) Footnote 73. Highest acceptance rates found in emergency departments (83% and 93%) Footnote 74,Footnote 77. When given the options of rapid and traditional testing, youth selected rapid tests 70% of the time Footnote 73. |

Participants who chose a rapid test were more likely to receive their test results within the follow-up period, compared with those who chose traditional test (91.3% vs. 46.7%; OR 12 95%CI 3.98-36.14) Footnote 73. 100% of youth aged 13-17 years who accepted rapid testing received their results Footnote 77. | N/A |

Cost-effectiveness

Of the 17 modelling studies reviewed by Dibosa-Osadolor et al., seven studies addressed diagnostic testing for HIV detection. Four modelling studies specifically assessed rapid testing with immediate patient notification in a clinical setting. The authors concluded that HIV rapid testing was more cost-effective than traditional laboratory-based testing with immediate patient notification Footnote 21. However, the majority of the modelling studies of rapid testing reviewed were based on static models, which do not include time dependencies. This can potentially result in an overestimation of the cost-effectiveness of infectious diseases Footnote 21,Footnote 22. In this review, there was no information on the direct and indirect costs of rapid testing or on the cost per the quality-adjusted life-year gained.

Discussion and conclusion

Our rapid review of eight systematic reviews found that HIV rapid tests demonstrated generally high acceptability, especially among pregnant women; variability in receiving test results; and limited impact on linkage to care. One review found that rapid testing was cost-effective, but the studies were based on a static versus a dynamic model; therefore, further studies are warranted to determine the impact of rapid tests on linkage to care and its cost-effectiveness.

The rapid review methodology is a fairly novel approach that has its strengths and limitations. The strength is that it is a rapid way to summarize evidence for decision-makers. In addition, the evidence is presented transparently, allowing users to assess the evidence and make informed decisions. However, there are a few limitations to consider when reviewing these results. The shortened timeframe of the rapid review process may miss studies that were not included in the reviews and therefore, may introduce bias through the absence of some relevant information. It may exclude recently published systematic reviews or those currently in press Footnote 23,Footnote 24. Moreover, data from some individual studies were cited more than once across the systematic reviews, which may inflate the confidence in the results presented in this rapid review Footnote 24,Footnote 25. Finally, the systematic reviews included studies from different countries and different types of HIV rapid tests; therefore, the results from this review may not be generalizable to other rapid tests or to the Canadian setting.

It appears that offering HIV rapid tests in settings is highly effective when test results can be readily obtained. This suggests that rapid HIV tests could decrease the proportion of individuals who are unaware of their HIV status and merits further study. Future research should compare effectiveness among different populations and settings, as well as explore ways to improve linkage to care. It would be useful to have a cost-effectiveness study based on a dynamic model.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Margaret Gale-Rowe, John Kim, Lisa Pogany and Tom Wong for their review and input into the writing of this article. The authors would also like to thank Cindy Smalley and Elizabeth Dekens for their contributions to the literature search.

Conflict of interest

None.

Funding

This study was supported by the Public Health Agency of Canada.

Page details

- Date modified: