Archived - E. coli O157:H7 infections associated with pork products in Canada

Download this article as a PDF (181 KB - 4 pages)

Download this article as a PDF (181 KB - 4 pages) Published by: The Public Health Agency of Canada

Issue: Volume 43-1: Enteric disease outbreaks

Date published: January 5, 2017

ISSN: 1481-8531

Submit a manuscript

About CCDR

Browse

Volume 43-1, January 5, 2017: Enteric disease outbreaks

Outbreak report

Escherichia coli O157:H7 infections associated with contaminated pork products — Alberta, Canada, July–October 2014

L Honish1,2*, N Punja1,2, S Nunn1,2, D Nelson1,2, N Hislop1,2, G Gosselin1,2, N Stashko2,3, D Dittrich2,3

Affiliations

1 Alberta Health Services, Canada

2 Investigative Team from Alberta Health Services, Alberta Provincial Laboratory for Public Health, Alberta Health, Alberta Agriculture and Forestry, Public Health Agency of Canada, Canadian Food Inspection Agency, Health Canada, First Nations and Inuit Health Branch

3 Alberta Agriculture and Forestry, Canada

Correspondence

Suggested citation

Honish L, Punja N, Nunn S, Nelson D, Hislop N, Gosselin G, Stashko N, Dittrich D. Escherichia coli O157:H7 infections associated with contaminated pork products — Alberta, Canada, July–October 2014. Can Commun Dis Rep. 2017;43(1):21-4. https://doi.org/10.14745/ccdr.v43i01a04

Note

† This paper is identical in content to the primary article published in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR) and released electronically on January 5, 2017, having met the guidelines for simultaneous publication as set forth by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors.

Summary

What is already known about this topic?

Pork is a known, although infrequent, source of human Escherichia coli O157:H7 infection. E. coli O157:H7 infections often result in clinically severe illness with serious complications in humans.

What is added by this report?

During July–October 2014, an outbreak of 119 cases of E. coli O157:H7 infections associated with exposure to contaminated pork products occurred in Alberta, Canada. E. coli O157:H7-contaminated pork and pork production environments and mishandling of pork products was identified at all key points in the implicated pork distribution chain. Measures to control the outbreak included product recalls, destruction of pork products, temporary food facility closures, targeted interventions to mitigate improper pork-handling practices, and prosecution of a food facility operator.

What are the implications for public health practice?

Pork should be considered in public health E. coli O157:H7 investigations and prevention messaging, and pork handling and cooking practices should be carefully assessed during regulatory food facility inspections.

Introduction

During July–October 2014, an outbreak of 119 Escherichia coli O157:H7 infections in Alberta, Canada was identified through notifiable disease surveillance and investigated by local, provincial and federal public health and food regulatory agencies. Informed by case interviews, seven hypothesized potential food sources were identified and investigated. The majority of patients reported having consumed meals containing pork at Asian-style restaurants in multiple geographically diverse Alberta cities during their exposure period. Traceback investigations revealed a complex pork production and distribution chain entirely within Alberta. E. coli O157:H7-contaminated pork and pork production environments and mishandling of pork products was identified at all key points in the chain, including slaughter, processor, retail and restaurant facilities. The outbreak pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) cluster pattern was found in clinical and pork E. coli O157:H7 isolates. Measures to mitigate the risk included pork product recalls, destruction of pork products, temporary food facility closures, targeted interventions to mitigate improper pork-handling practices identified at implicated food facilities and prosecution of a food facility operator. Pork should be considered in E. coli O157:H7 investigations, and prevention messaging, and pork handling and cooking practices should be carefully assessed during regulatory food facility inspections.

Epidemiologic Investigation

For this outbreak, a case was defined as a laboratory culture-confirmed E. coli O157:H7 infection with one of 16 PFGE cluster patterns identified in a resident of or visitor to Canada during July–November 2014. Cases were identified through notifiable disease surveillance.

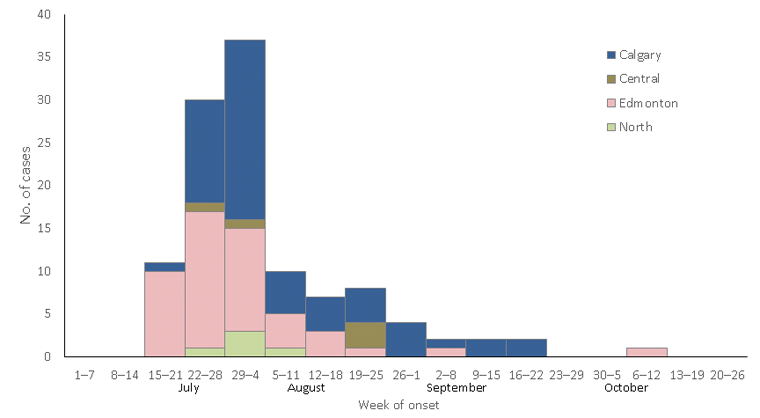

A total of 119 outbreak cases were identified, including four (3%) patients who were classified as having secondary infections (i.e., acquired through household contact with an outbreak-associated patient). All patients were in Alberta during all or part of the incubation period. Illness onsets for the 119 patients ranged from July 20 to October 6 (Figure 1). Cases occurred among persons in a wide geographical distribution across Alberta. Twenty-three (19%) patients were hospitalized, six of whom developed hemolytic uremic syndrome; no deaths were reported. The median age of patients was 23 years (range = 1– 82 years) and 76 patients (64%) were female.

Figure 1: Cases of pork-associated E. coli O157:H7 infection week of onset and region — Alberta, Canada, July‑October 2014 Figure 1 footnote 1

Text description: Figure 1

Figure 1: Cases of pork-associated E. coli O157:H7 infection week of onset and region — Alberta, Canada, July‑October 2014 Figure 1 footnote 1

| Week of onset | Number of cases | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| North | Edmonton | Central | Calgary | |

| July 1–7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| July 8–14 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| July 15–21 | 0 | 10 | 0 | 1 |

| July 22–28 | 1 | 16 | 1 | 12 |

| July 29–August 4 | 3 | 12 | 1 | 21 |

| August 5–11 | 1 | 4 | 0 | 5 |

| August 12–18 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 4 |

| August 19–25 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 4 |

| August 26– September 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| September2–8 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| September 9–15 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| September 16–22 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| September 23–29 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| September 30–October 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| October 6–12 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| October 13–19 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| October 20–26 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Exposure to food at Alberta Asian-style restaurants (36 facilities widely distributed across the province) was reported by 85 (74%) of the 115 primary outbreak patients. Routine public health follow-up interviews failed to identify the source. Enhanced interviews with patients and follow-up at restaurants revealed that the exposure-specific frequency for each of seven ingredients (mung bean sprouts, beef, carrots, cucumbers, green onions, lettuce, and pork) exceeded 35%.

Environmental Investigation

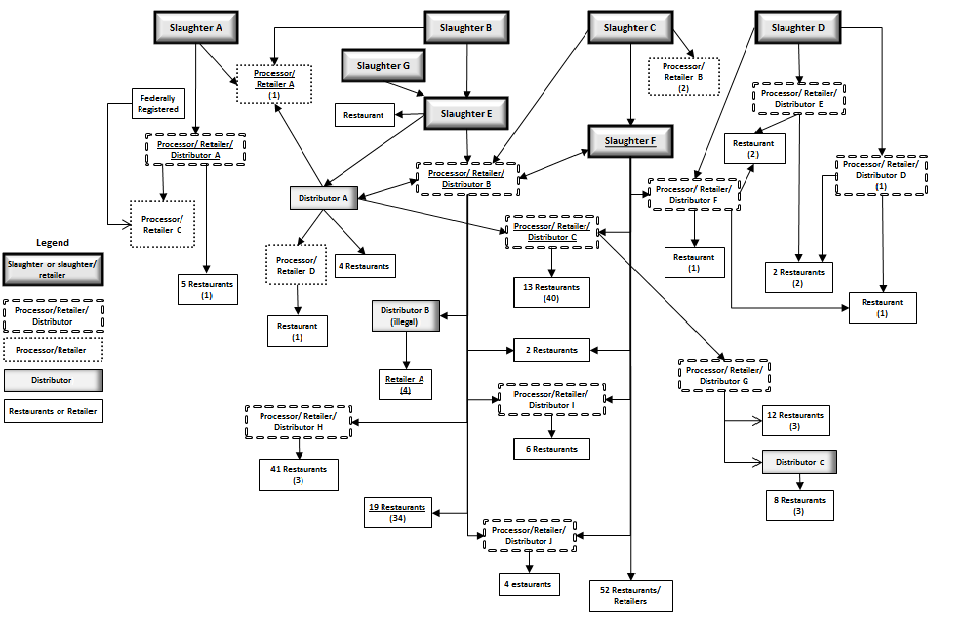

Regulatory agencies conducted inspections at 201 food facilities to inform the investigation and control the outbreak. Extensive investigation of Alberta mung bean sprout supplier/distributor facilities ruled out this product as a source. A traceback investigation was initiated that focused on suppliers of the six remaining high exposure-frequency foods. No single common restaurant supplier was identified for these foods. Pork was identified as the only ingredient with a supplier network entirely within Alberta, and thus emerged as the leading hypothesized source of the outbreak. Confirmation of the complex intra-Alberta pork supplier network (Figure 2) revealed that exposure to food from a facility within the network was the most common identified exposure (Table 1) among primary outbreak case patients (96/115, 83%). Most of these exposures occurred at restaurants (81, 84%). Consumption of pork was identified among 65% of outbreak case patients. A total of 295 samples, including environmental surface swabs (n = 157), food (116), food surface swabs (13), and water (9), were collected analyzed for the presence of E. coli O157:H7. A range of sample types were collected during hypothesis generation; sample collection later focused on pork and pork production environments, as informed by the investigation. E. coli O157:H7 was identified in 18 samplesFootnote *, all of which were from pork or pork products or surface swabs in pork production facilities. Apart from two isolates from a slaughter facility, PFGE cluster patterns identified in patient isolates matched those in food and environmental sample isolates. Four outbreak cases were associated with exposure to chicken sausage products from one facility; laboratory analysis of the products identified E. coli O157:H7, detected pork, and did not detect poultry. Investigation revealed that the chicken product producer had purchased pork fraudulently labeled as chicken by an illegal distributor linked to a facility in the Alberta pork supplier network.

Figure 2: Alberta pork supplier network, pork-associated E. coli 0157:H7 outbreak — Alberta, Canada, July-October 2014 Figure 2 footnote 1Figure 2 footnote 2Figure 2 footnote 3Figure 2 footnote 4

Text description: Figure 2

Figure 2: Alberta pork supplier network, pork-associated E. coli 0157:H7 outbreak — Alberta, Canada, July-October 2014 Figure 2 footnote 1Figure 2 footnote 2Figure 2 footnote 3Figure 2 footnote 4

The flow diagram of the Alberta pork supplier network has four boxes at the top of the figure named slaughter A, B, C and D. From slaughter A there are two arrows; one going to processer/retailer A and the other going to processor/retailer/distributor A. There are no arrows going out from the processor retailer A box. From the processor/retailer/distributor A box there are two arrows going out. One to processor/retailer C that is federally registered and the other box goes to five restaurants. From the slaughter B box there are two arrows going out - one to the same processor/retailer A box as slaughter A and the other goes to slaughter E. A Slaughter G box also points to slaughter E. From the slaughter E box there are three arrows. The first arrow goes to a box marked restaurant, the second arrow goes to a box marked distributor A. The third box goes to processor/retailer/Distributor B box. The distributor A box has a two-way arrow that points to and from processor/retailer/distributor B and has three arrows going out from it. One arrow goes to processor/retailer/distributor C, a second arrow goes to a processor/retailer D and the third arrow goes to a box marked four restaurants. From processor/retailer D box there is one arrow that points to a box with one restaurant. From processor/retailer/distributor B there are 6 arrows going out. One arrow goes to a box marked illegal distributor B that points to retailer A. The second arrow points to two restaurants. A third arrow points to processor/retailer/distributor I that points to 6 restaurants. A fourth arrow points to processor/retailer/distributor H that points to 41 restaurants. A fifth arrow points to 19 restaurants and the sixth arrow points to processor/retailer/distributor J which in turn points to 4 restaurants. From processor/retailer/distributor C there are two arrows going out – one to 13 restaurants and one to processor/retailer/distributor G that in turn has two arrows going out: one to 12 restaurants and one to distributor C that goes out to 8 restaurants. Slaughter C has three arrows; one points to processor/retailer/distributor B, one points to Slaughter F and one points to processor/retailer B. processor/retailer/distributor B. There are 6 arrows going out from Slaughter F: one to processor/retailer/distributor C, a second to two restaurants a third at processor/retailer/distributor I, a fourth that points to processor/retailer/distributor H, a fifth that points to 52 restaurants and retailers and a sixth that points to processor/retailer/distributor F. Slaughter D has 3 arrows; one points to processor/retailer/distributor F, the second points to processor/retailer/distributor E and the third points to processor/retailer/distributor D. Processor/retailer/distributor F points to three boxes: one restaurant (as does processor/retailer/distributor E), one restaurant (as well as processor/retailer/distributor D) as well as another restaurant. In addition, processor/retailer/distributor E points to 2 restaurants (that is also linked to processor/retailer/distributor D).

| Potential exposure sites | Number of patients with exposure to site | Number (%) of patients with pork exposure |

|---|---|---|

| Asian-style restaurant(s)Table 1 - Footnote 2 | 81 | 48 (59) |

| Asian-style marketTable 1 - Footnote 2 | 3 | 1 (33) |

| Sausage producer/retailerTable 1 - Footnote 2 | 4 | 4 (100) |

| Festival temporary food facilityTable 1 - Footnote 2 | 7 | 7 (100) |

| Meat processor/retailerTable 1 - Footnote 2 | 1 | 1 (100) |

| Asian-style restaurant(s)Table 1 - Footnote 3 | 4 | 4 (100) |

| No suspect source facilityTable 1 - Footnote 4 | 12 | 10 (83) |

| Poor historian | 3 | n/a |

| Total | 115 | 75 (65) |

Public Health Response

The local health department ordered four food facilities, including one slaughter/retail facility, two processor/distributor/retail facilities and one restaurant facility, to temporarily close, as a result of significant numbers of cases associated with exposure to food distributed by the facility, identified critical food handling violations and/or E. coli O157:H7-positive surface swabs. The illegal pork distributor fraudulently selling pork as chicken was issued court orders to close the business and to appear for questioning. The operator failed to appear, and an arrest warrant was issued. The Canadian Food Inspection Agency issued recall notices for pork products (and chicken products containing pork) distributed by six facilities. Multiple news releases were issued to local media outlets to inform the public of the outbreak investigation.

Root cause analyses were conducted by food regulatory agencies at four slaughter facilities implicated in the pork supplier network. All facilities slaughtered multiple species, including cattle. Common observations included opportunities for cross-contamination related to sharing of animal pens, inadequate cleaning and sanitation of knives or equipment between carcasses, and close proximity of carcasses during slaughter activities. At the slaughter facility that was temporarily closed, inconsistent personnel hygiene practices and poor knowledge of food safety were also identified. Corrective actions related to sanitary dressing procedures, process flow, hygiene, hand-washing, cleaning and sanitation were initiated and monitored through routine inspections. Products suspected of being contaminated were removed from one facility.

Environmental Health Officers (EHOs) with the local health department conducted comprehensive assessment of pork-handling practices and other potential contributing factors at 111 restaurants (those at which patients were thought to have acquired their infection and additional selected similar restaurants in Alberta). EHOs observed practices used by operators at baseline, surveyed them about their procedures using a standardized questionnaire and used this information to inform intervention strategies. Few operators had validated or standardized procedures for cooking pork products and the majority used visual indicators to ascertain whether pork products were adequately cooked. Cross-contamination concerns that might have contributed to infection were identified in several restaurants. EHOs identified that staff with adequate food safety training at >80% of facilities often did not have direct oversight of day-to-day food handling activities. Interventions and ongoing monitoring programs with short, intermediate and long-term objectives were implemented at the facilities to mitigate identified problems. This phased approach included delivery of onsite food safety training by EHOs, development and distribution of educational resources in the first language of employees (printed and online) and assistance with the creation of food safety plans for properly cooking pork products. Mitigation strategies included the distribution of digital thermometers and digital timers by EHOs. During on-site training sessions, EHOs demonstrated proper hand-washing and environmental surface sanitation procedures, and identified other strategies operators could use to reduce the likelihood of cross-contamination. Compliance with these food safety elements was measured before and after mitigation strategies were carried out to help evaluate selected intervention measures.

Discussion

This outbreak represents the second largest foodborne and third largest overall E. coli O157:H7 outbreak in Canadian history, after a foodborne outbreak associated with salami produced in British Columbia in 1999 Footnote 1 and after a waterborne outbreak in Walkerton, Ontario in 2000 Footnote 2. There is strong epidemiological evidence that the cause of this outbreak was exposure to contaminated pork products produced and distributed in Alberta. The molecular epidemiology of the clinical and pork E. coli O157:H7 outbreak isolates is described elsewhere Footnote 3. Pork is a known, although infrequent, source of human E. coli O157 infection Footnote 4Footnote 5Footnote 6Footnote 7Footnote 8. Most documented outbreaks have been associated with sausage products containing pork and other meats, and the species-specific source of contamination was not confirmed. It has been reported that E. coli O157:H7 is prevalent globally at varying rates in swine, that infected swine might shed the bacteria for prolonged periods and horizontal transmission between swine and other livestock species might occur Footnote 9.

E. coli O157:H7-contaminated pork and pork production environments and mishandling of pork products was identified at all key points in the implicated Alberta pork distribution chain, including slaughter, processor, retail and restaurant facilities. The originating source or sources of the contamination was however not confirmed. Cross-contamination appears to be an important contributing factor in this outbreak, as evidenced by absence of known pork exposure in 35% of outbreak cases. Based on the findings of this investigation, pork should be considered a potential source in public health E. coli O157:H7 investigations and prevention messaging, and pork handling and cooking practices should be carefully assessed during regulatory food facility inspections.

Acknowledgments

Brent Friesen, Kate Snedeker, Adrienne MacDonald, Alberta Health Services; Linda Chui, Jocelyne Kakulphimp, Alberta Provincial Laboratory for Public Health.

Alberta Health Services, Alberta Agriculture and Forestry, from Alberta Health Services, Alberta Provincial Laboratory for Public Health, Alberta Health, Alberta Agriculture and Forestry, Public Health Agency of Canada, Canadian Food Inspection Agency, Health Canada, First Nations and Inuit Health Branch.