Acute flaccid myelitis (AFM) in Canada

Download this article as a PDF

Download this article as a PDFPublished by: The Public Health Agency of Canada

Issue: Volume 46–10: Laboratory Biosafety

Date published: October 1, 2020

ISSN: 1481-8531

Submit a manuscript

About CCDR

Browse

Volume 46–10, October 1, 2020: Laboratory Biosafety

Rapid communication

Acute flaccid myelitis in Canada, 2018 to 2019

Catherine Dickson1, Brigitte Ho Mi Fane1, Susan G Squires1

Affiliation

1 Centre for Immunization and Respiratory Infectious Diseases, Public Health Agency of Canada, Ottawa, ON

Correspondence

Suggested citation

Dickson C, Ho Mi Fane B, Squires SG. Acute flaccid myelitis in Canada, 2018 to 2019. Can Commun Dis Rep 2020;46(10):349–53. https://doi.org/10.14745/ccdr.v46i10a07

Keywords: acute flaccid myelitis, acute flaccid paralysis, enterovirus, infectious disease, surveillance

Abstract

Starting in 2014, biennial clusters of acute flaccid myelitis (AFM), frequently described as “polio-like” illness, have been reported across the United States and elsewhere, often linked to enteroviruses. To assess AFM trends in Canada, we reviewed the Canadian Acute Flaccid Paralysis Surveillance System (CAFPSS) for cases reported during the 2018 and 2019 calendar years that meet the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention case definitions for AFM. A total of 10 cases (8 in 2018 and 2 in 2019) met the confirmed AFM case definition and 30 (26 in 2018 and 4 in 2019) met the probable AFM case definition. Sixty percent of confirmed and probable cases were younger than five years old, and all cases had symptom onset between the months of July and October. Enteroviruses were detected in 50% of confirmed cases. At the time of writing this report, 2020 AFM data were not yet available; it is unknown if a spike in AFM cases will be seen in 2020.

Introduction

Spikes in acute flaccid myelitis (AFM), an emerging form of acute flaccid paralysis (AFP) related to viral infections and frequently described as “polio-like” illness, have been reported in the United States and elsewhere, in a seemingly biennial pattern in the summer and fall, in 2014, 2016 and 2018Footnote 1Footnote 2Footnote 3Footnote 4Footnote 5.

AFP is defined as a sudden onset of paralysis with reduced muscle tone in one or more limbs. This syndrome is caused by a range of etiologies, such as Guillain–Barré syndrome, transverse myelitis or neuropathies. These conditions are associated with neurotropic viruses, such as enteroviruses, including polio, Herpesviridae and parainfluenzavirusFootnote 6. AFM is a subtype of AFP associated with lesions in the grey matter of the spinal cord. It has been linked to viral infections, particularly enteroviruses EV-D68 and EV-A71, which can be spread via oral–fecal and respiratory routesFootnote 3Footnote 7Footnote 8.

AFM has been associated with disability and large healthcare requirements, mostly in childrenFootnote 9Footnote 10. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has reported extensively on recent trends of AFM, in the United StatesFootnote 3Footnote 11. This emerging trend has led to concerns about the potential effect of AFM on Canadians. The seriousness of the condition as well as the lack of clear knowledge about the etiology of the disease underscore the need to better understand the epidemiology of AFM to further identify prevention and patient management measuresFootnote 3.

This study describes the preliminary analysis of AFM in Canada for the years 2018 and 2019, using data from the Canadian Acute Flaccid Paralysis Surveillance System (CAFPSS). Understanding seasonality trends of AFM can be helpful for public health and healthcare systems in their resource planning and messaging in preparation for a potential seasonal spike in 2020.

Methods

CAFPSS collects information on cases of AFP in children younger than 15 years old through reports from the Canadian Immunization Program Monitoring Active (IMPACT) and from the Canadian Paediatric Surveillance Program (CPSP). IMPACT is a network of 12 paediatric centres across Canada, representing 90% of paediatric tertiary care beds. CPSP collects information on rare paediatric conditions from a network of over 2,500 paediatricians across the countryFootnote 12Footnote 13. By monitoring for potential cases of polio presenting with AFP, CAFPSS is part of Canada’s ongoing efforts to maintain our polio elimination status. CAFPSS collects information on clinical presentation and investigations including laboratory results and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) reports. All cases in the CAFPSS are adjudicated against the AFP case definition by a specially trained physician.

AFM is not a notifiable disease in Canada; as such, following the increase in AFM cases reported in the United States in 2018, CAFPSS has been leveraged to monitor for AFM as it would be captured within the broader case definition of AFP. Each confirmed AFP case is reviewed by the adjudicating physician against the CDC case definition to determine the AFM status of AFP cases reported in Canada. For this paper, we used the 2018 CDC case definition for AFMFootnote 6:

- A case was classified as confirmed AFM if the MRI results show a spinal cord lesion with predominant grey matter involvement spanning one or more vertebral segments

- A case was classified as probable AFM if the cerebrospinal fluid had a white blood cell count greater than 5 cells/mm3

We extracted 2018 and 2019 AFP data from CAFPSS and aggregated these by year of paralysis/weakness onset. We then conducted descriptive analyses by year, age group, sex, AFM status (using the 2018 CDC case definition), outcome and virology results.

Results

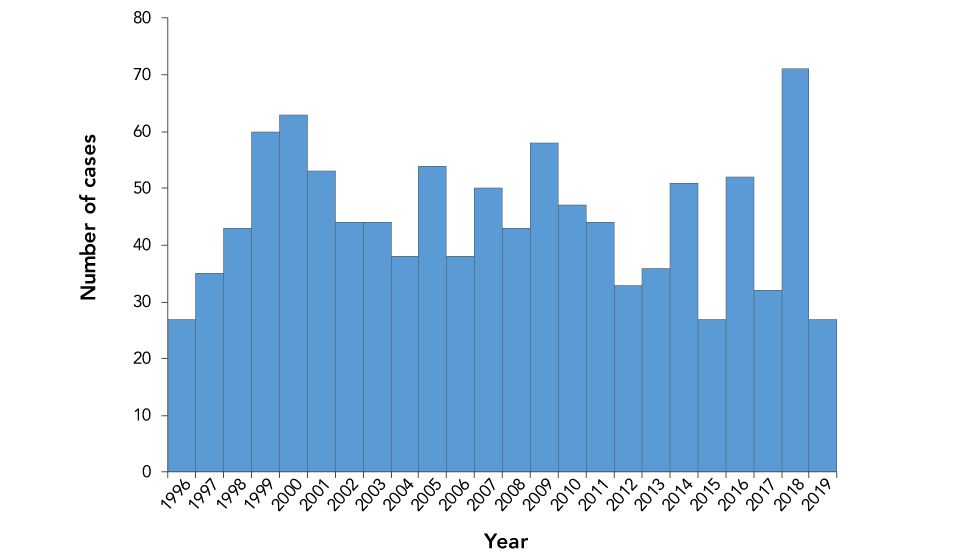

Since the implementation of CAFPSS in 1996, an average of 45 confirmed cases of AFP have been reported to the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) annually, from 27 cases in 1996 and 2019 to 71 cases in 2018 (Figure 1). Between 2018 and 2019, PHAC received 120 reports of sudden onset muscle weakness in children younger than 15 years old. Of these reports, 98 were confirmed as AFP cases, eight did not meet the AFP case definition and were discarded, nine were duplicates and five remain under investigation, meaning that additional information has been requested to determine if they meet the AFP case definition.

Figure 1: Number of confirmed AFP cases in Canada, by year, 1996–2019 (n=1,070)Figure 1 footnote a

Text description: Figure 1

Figure 1: Number of confirmed AFP cases in Canada, by year, 1996–2019 (n=1,070)Figure 1 footnote a

| Year | Number of confirmed AFP cases |

|---|---|

| 1996 | 27 |

| 1997 | 35 |

| 1998 | 43 |

| 1999 | 60 |

| 2000 | 63 |

| 2001 | 53 |

| 2002 | 44 |

| 2003 | 44 |

| 2004 | 38 |

| 2005 | 54 |

| 2006 | 38 |

| 2007 | 50 |

| 2008 | 43 |

| 2009 | 58 |

| 2010 | 47 |

| 2011 | 44 |

| 2012 | 33 |

| 2013 | 36 |

| 2014 | 51 |

| 2015 | 27 |

| 2016 | 52 |

| 2017 | 32 |

| 2018 | 71 |

| 2019 | 27 |

Following the review of the 2018 and 2019 AFP confirmed cases using the 2018 CDC case definition, 10 cases were classified as confirmed AFM and 30 as probable AFM (Table 1). Of both confirmed and probable cases, 60% were younger than five years old. Boys accounted for slightly more than half of all AFM cases (Table 2).

| Classification | 2018 | 2019 | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Confirmed AFP cases | 71 | 100 | 27 | 100 | 98 | 100 |

| AFM statusFootnote b of Table 1 | ||||||

| Confirmed | 8 | 11 | 2 | 7 | 10 | 10 |

| Probable | 26 | 37 | 4 | 15 | 30 | 31 |

| Not AFM | 23 | 32 | 17 | 63 | 40 | 41 |

| Unable to determineFootnote c of Table 1 | 14 | 20 | 4 | 15 | 18 | 18 |

| Parameter | AFM cases | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Confirmed (n=10) | Probable (n=30) | Not AFM (n=40) | AFM status not determined (n=18) | |||||

| Median age (years) | 4.9 | 4.8 | 2.9 | 5.8 | ||||

| Age range | (11 months to 13.6 years) | (7 months to 14.5 years) | (3 months to 14.5 years) | (1.5 to 14.8 years) | ||||

| Age group (years) | ||||||||

| Younger than 1 | 1 | 10% | 1 | 3% | 5 | 13% | 0 | 0 |

| 1–4 | 5 | 50% | 17 | 57% | 24 | 60% | 8 | 44% |

| 5–9 | 3 | 30% | 6 | 20% | 6 | 15% | 3 | 17% |

| 10–14 | 1 | 10% | 6 | 20% | 5 | 13% | 7 | 39% |

| Sex | ||||||||

| Female | 4 | 40% | 14 | 47% | 16 | 40% | 6 | 33% |

| Male | 6 | 60% | 16 | 53% | 23 | 58% | 12 | 67% |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3% | 0 | 0 |

| Outcome at the time of most recent case report update | ||||||||

| Fully recovered | 0 | 0 | 7 | 23% | 7 | 18% | 2 | 11% |

| Partial recovery with residual paralysis/weakness | 3 | 30% | 7 | 23% | 14 | 35% | 6 | 33% |

| Deceased | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3% | 0 | 0 |

| UnknownFootnote b of Table 2 | 7 | 70% | 16 | 53% | 18 | 45% | 10 | 56% |

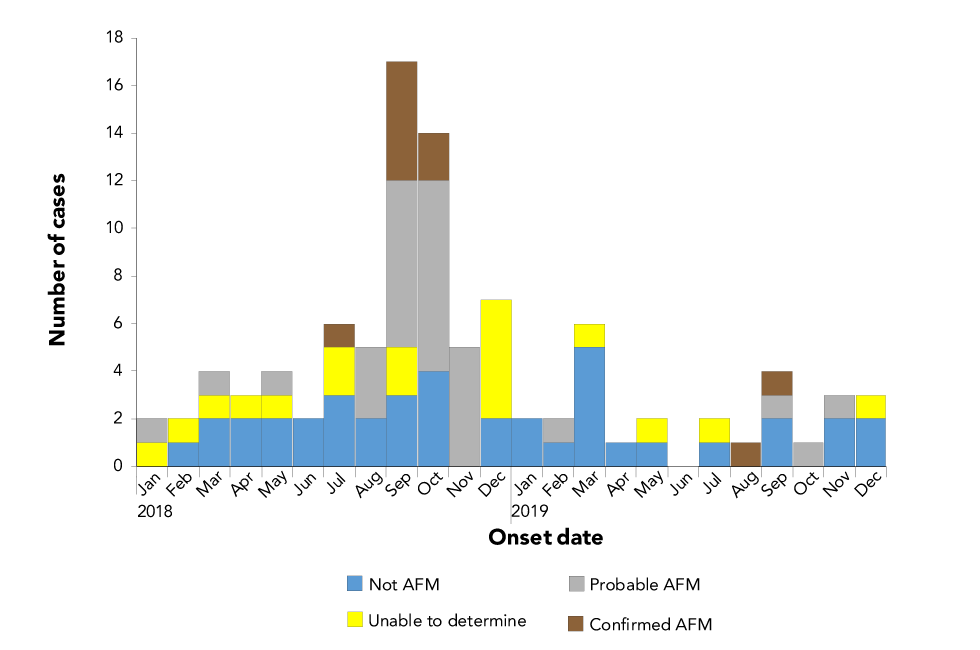

Of the 10 confirmed AFM cases, all had a symptom onset date between July and October. Probable AFM cases had a symptom onset between January and November, although 87% (n=26) of these had a symptom onset between August and November (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Confirmed AFP cases reported to PHAC by paralysis or weakness onset date and by AFM status, 2018–2019Figure 2 footnote a

Text description: Figure 2

Figure 2: Confirmed AFP cases reported to PHAC by paralysis or weakness onset date and by AFM status, 2018–2019Figure 2 footnote a

| Onset month | Not AFM | Confirmed AFM | Probable AFM | Unable to determine | Total number of AFP cases |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| January 2018 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| February 2018 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| March 2018 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| April 2018 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| May 2018 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| June 2018 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| July 2018 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 6 |

| August 2018 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 5 |

| September 2018 | 3 | 5 | 7 | 2 | 17 |

| October 2018 | 4 | 2 | 8 | 0 | 14 |

| November 2018 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 5 |

| December 2018 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 7 |

| January 2019 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| February 2019 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| March 2019 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 6 |

| April 2019 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| May 2019 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| June 2019 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| July 2019 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| August 2019 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| September 2019 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 4 |

| October 2019 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| November 2019 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 |

| December 2019 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 |

All confirmed and probable cases were hospitalized. The median duration of hospitalization for confirmed AFM cases was 17.5 days (range: 2–70 days) and for probable AFM cases was 12 days (range: 3–46 days). Of the 10 confirmed AFM cases, none had fully recovered at the time of most recent case report update and three (30%) had partially recovered with residual paralysis/weakness. As for the 30 probable AFM cases, seven (23%) had recovered and seven (23%) had partially recovered with residual paralysis/weakness at the time of most recent case report update.

Enteroviruses were detected in five of the confirmed AFM cases: two were positive for EV-D68, one case was positive for EV-A71, one case was positive for enterovirus type unspecified and the remaining case was positive for rhinovirus/enterovirus single target. These viruses were detected through stool samples (n=3), throat swabs (n=1) and nasopharyngeal swabs (n=1). No other viral agents were detected in confirmed AFM cases, although viral testing was performed for all cases.

Of the 30 probable AFM cases, 26 (87%) had viral testing results available. Of these, enteroviruses were detected in 10 (38%) cases: five (50%) had EV-D68, three (30%) had enterovirus type unspecified, one (10%) had EV-A71 concurrent with rhinovirus and one (10%) was positive for rhinovirus/enterovirus single target. These probable AFM cases had enterovirus or rhinovirus/enterovirus single target detected through throat swabs (n=4), nasopharyngeal swabs (n=4), stool samples (n=1) and cerebrospinal fluid (n=1). In addition, six (23%) probable AFM cases had other viral agents detected.

Of the 40 cases classified as not AFM cases, 17 (43%) had viral testing results available. Of these, three (18%) cases tested positive for enteroviruses: one case was positive for enterovirus type unspecified, one for rhinovirus/enterovirus single target and one for rhinovirus/enterovirus single target along with another viral infection. These infections were detected from nasopharyngeal swabs (n=2) and stool samples (n=1). One additional case classified as not AFM was positive for another viral agent.

Of the 18 cases for which AFM status could not be determined, 13 (72%) had viral testing results available. Of these, one case was positive for enterovirus type unspecified detected via a throat swab. The remaining cases were either positive for other viral agents (n=2) or had negative virology results (n=10).

Other viral agents detected in the cases that were not confirmed AFM included bocavirus, adenovirus, rhinovirus, coxsackievirus, Epstein–Barr virus, West Nile virus and norovirus.

Strengths and limitations

The increase in AFP case reports in 2018 may be due, in part, to increased awareness of AFM among Canadian clinicians following the increase in number of AFM cases in the United States during that year.

Because the purpose of CAFPSS is to monitor for poliovirus in children, it is not an ideal surveillance tool for AFM. CAFPSS is limited to cases in children younger than 15 years old. As such, the trends described here are limited by data collection availability only for people younger than 15 years. Although cases of AFM have been reported in adults, the majority have been in young childrenFootnote 3. This suggests that CAFPSS can be expected to capture the majority of AFM cases. We anticipate that, although this limitation would reduce overall AFM case counts, it would not affect overall AFM trends.

MRI is essential for the confirmation of AFM. However, in this report, assessments were limited to the information provided to CAFPSS, which were often brief summaries of the MRI report. In other words, it was not possible to ascertain whether some cases met the case definition for AFM. CAFPSS did, however, allow for the use of an existing surveillance tool to monitor trends during periods when spikes in AFM activity have been reported elsewhere and to identify AFM activity related in part to non-polio enterovirus with a similar pattern in seasonality to reports coming out of the United States.

At the time of writing this report, 2020 AFM data were not yet available. The data will need to be analyzed in relation to recent historical trends. It is yet to be seen whether physical distancing and infection control practices in the community will reduce the burden of AFM by reducing community transmission of viruses other than coronavirus disease (COVID-19). The authors will continue to monitor reports of AFP and AFM in Canada and work with surveillance partners to ensure ongoing reporting.

Conclusion

In 2018, a record number of AFP cases was reported to CAFPSS, substantially higher than in 2019. A small proportion (10%) of the cases reported from 2018 and 2019 met the 2018 CDC case definition for confirmed AFM, with the majority having onset of paralysis in the late summer and early fall of 2018. This coincides temporally with the cyclical increase in AFM cases observed in the United StatesFootnote 3, suggesting that a similar trend might be occurring in Canada.

A larger proportion of AFP cases (31%) met the 2018 CDC case definition for probable AFM. It is anticipated that a larger proportion of AFP cases would meet the case definition for probable AFM cases given the broad requirement criteria. The CDC has revised the 2020 probable AFM case definition to be more specificFootnote 14. We anticipate this greater specificity will lead to fewer diagnosed cases of probable AFM in future years when the new case definition is applied to our surveillance data.

Enterovirus or rhinovirus/enterovirus was detected in non-cerebrospinal fluid specimens of half of the confirmed AFM cases, a greater proportion than seen in any of the other AFM categories. This is consistent with other reports of AFM being linked to enterovirus infectionsFootnote 3Footnote 7. No other viral infections were reported in confirmed AFM cases, whereas a variety of other viral infections were reported in each of the other AFM categories, suggesting that these cases might be linked to multiple viral etiologies.

Authors’ statement

- CD — Conceptualization, investigation, writing–original draft, writing–review and editing

- BHMF — Methodology, investigation, formal analysis, writing–original draft, writing–review and editing

- SGS — Conceptualization, writing–review and editing

Competing interests

None.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank F Reyes Domingo, M Roy and D MacDonald for their work on acute flaccid paralysis surveillance as well as Dr. J Ahmadian-Yazdi for his assistance with the preparation of this manuscript. The authors would also like to thank the Canadian Paediatric Surveillance Program and the Canadian Immunization Program Monitoring Active (IMPACT) surveillance program, particularly the IMPACT nurse monitors.

Funding

This work was supported by the Public Health Agency of Canada.