Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in paediatrics

Download this article as a PDF

Download this article as a PDFPublished by: The Public Health Agency of Canada

Issue: Volume 47 No. 11, November 2021: Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children

Date published: November 2021

ISSN: 1481-8531

Submit a manuscript

About CCDR

Browse

Volume 47 No. 11, November 2021: Multisystem Inflammatory Syndrome in Children

Rapid Communication

Rapid review of multisystem inflammatory syndrome in paediatrics: What we know one year later

Megan Striha1, Rojiemiahd Edjoc1, Natalie Bresee2, Nicole Atchessi1, Lisa Waddell3, Terri-Lyn Bennett4, Emily Thompson1, Maryem El Jaouhari1, Samuel Bonti-Ankomah1

Affiliations

1 Health Security and Regional Operations Branch, Public Health Agency of Canada, Ottawa, ON

2 Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario, Ottawa, ON

3 National Microbiology Laboratory, Public Health Agency of Canada, Winnipeg, MB

4 Centre for Surveillance and Applied Research, Public Health Agency of Canada, Ottawa, ON

Correspondence

Suggested citation

Striha M, Edjoc R, Bresee N, Atchessi N, Waddell L, Bennett T-L, Thompson E, El Jaouhari M, Bonti-Ankomah S. Rapid review of multisystem inflammatory syndrome in paediatrics: What we know one year later. Can Commun Dis Rep 2021;47(11):466–72. https://doi.org/10.14745/ccdr.v47i11a04

Keywords: multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children, pediatric multisystem inflammatory syndrome, COVID-19, MIS-C, PIMS, PIMS-TS

Abstract

Background: Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) associated with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is an emerging condition that was first identified in paediatrics at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. The condition is also known as pediatric inflammatory multisystem syndrome temporally associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (PIMS-TS or PIMS), and multiple definitions have been established for this condition that share overlapping features with Kawasaki Disease and toxic shock syndrome.

Methods: A review was conducted to identify literature describing the epidemiology of MIS-C, published up until March 9, 2021. A database established at the Public Health Agency of Canada with COVID-19 literature was searched for articles referencing MIS-C, PIMS or Kawasaki Disease in relation to COVID-19.

Results: A total of 195 out of 988 articles were included in the review. The median age of MIS-C patients was between seven and 10 years of age, although children of all ages (and adults) can be affected. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children disproportionately affected males (58% patients), and Black and Hispanic children seem to be at an elevated risk for developing MIS-C. Roughly 62% of MIS-C patients required admission to an intensive care unit, with one in five patients requiring mechanical ventilation. Between 0% and 2% of MIS-C patients died, depending on the population and available interventions.

Conclusion: Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children can affect children of all ages. A significant proportion of patients required intensive care unit and mechanical ventilation and 0%–2% of cases resulted in fatalities. More evidence is needed on the role of race, ethnicity and comorbidities in the development of MIS-C.

Introduction

On March 11th, 2020 the World Health Organization declared a global pandemic of the severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). Soon after, in April 2020, multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C) associated with SARS-CoV-2 virus was identified in the United Kingdom (UK)Footnote 1. Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children is an acute illness that is characterized by immune dysregulation with multisystem involvement and severe symptoms typically requiring hospitalization. The syndrome is thought to occur in children two to six weeks following infection with SARS-CoV-2Footnote 2.

The syndrome is also known as pediatric inflammatory multisystem syndrome temporally associated with SARS-CoV-2 (PIMS-TS or PIMS). Multiple definitions have been established for this condition, including by the World Health OrganizationFootnote 3, United States (US) Centers for Disease Control and PreventionFootnote 4, the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health in the UKFootnote 5 and the Canadian Paediatric SocietyFootnote 6Footnote 7. The definitions, which are similar but not identical, are provided in Appendix A.

There is no definitive diagnostic test for MIS-C and MIS-C is considered a separate but similar clinical syndrome to Kawasaki Disease (complete, incomplete, atypical or shock syndrome), toxic shock syndrome and macrophage activated syndromeFootnote 8.

Current situation

More than a year has elapsed since MIS-C was first identified during the ongoing coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic and a large body of evidence is now available. This review aims to synthesize what is currently known and what is still unclear about the epidemiological characteristics of this emerging disease.

Methods

A database maintained by the Public Health Agency of Canada is populated daily with new COVID-19 literature and includes studies published since the start of the pandemic until March 9, 2021, in PubMed, Scopus, BioRxiv, MedRxiv, ArXiv, SSRN and Research Square. Articles were cross-referenced with the COVID-19 information centers centres run by Lancet, BMJ, Elsevier and Wiley. These COVID-19 studies were gathered in an Excel spreadsheet database and were searched to retrieve MIS-C literature.

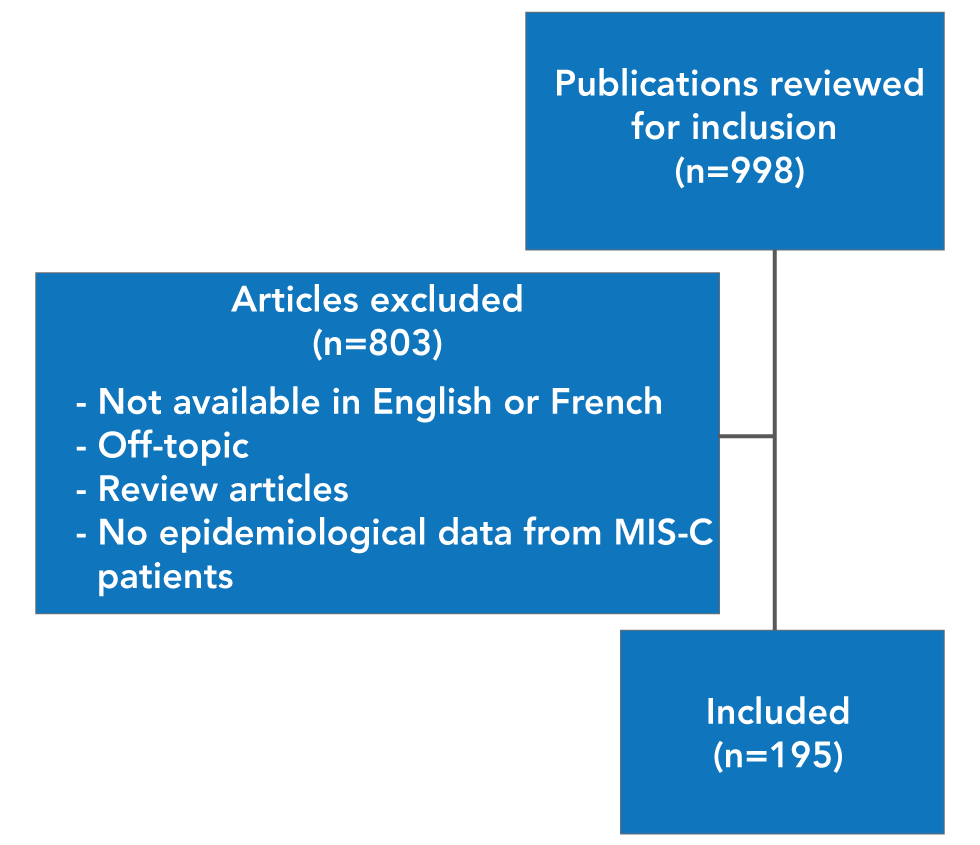

Articles (n=998) were screened for relevance and were included if epidemiological descriptions of MIS-C, PIMS, PIMS-TS or Kawasaki Disease related to COVID-19 were present. Articles (n=803) were excluded if they were not available in English or French, they were off-topic, they were review article or they did not contain epidemiological data from MIS-C patients. In total, 195 articles were deemed relevant and included in this review (Figure 1). Multiple articles could potentially refer to the same cases, and therefore double counting is a limitation of this review.

Figure 1: Article exclusion tree

Text description: Figure 1

There were 998 articles included in this review with 803 excluded based on a set criteria set a priori. Overall, 195 articles were included in the full article review.

Results

A total of 195 articles were included in this review. The vast majority of articles were cohorts (prospective n=15, retrospective n=70 or ambi-directional n=4) and case reports (n=101), with a minority being case-controls (n=3) or natural experiments (n=2).

Most articles originated in the US (n=78) and the UK (n=23), with a smaller number from India (n=18) and European countries (France n=12, Italy n=10, Spain n=7). There were far fewer studies from Africa (South Africa n=2, Algeria n=1, Nigeria n=1, Egypt n=1) and Asia (South Korea n=2, Japan n=1, Indonesia n=1).

Case reports were summarized together (articles=101, MIS-C cases=207), as individual patient information was often available. The cohorts, case-controls and natural experiment articles were also summarized together and are referred to as cohorts in the results section (articles=94, MIS-C cases=4,630). Article summaries are available in Supplemental material.

Age and sex

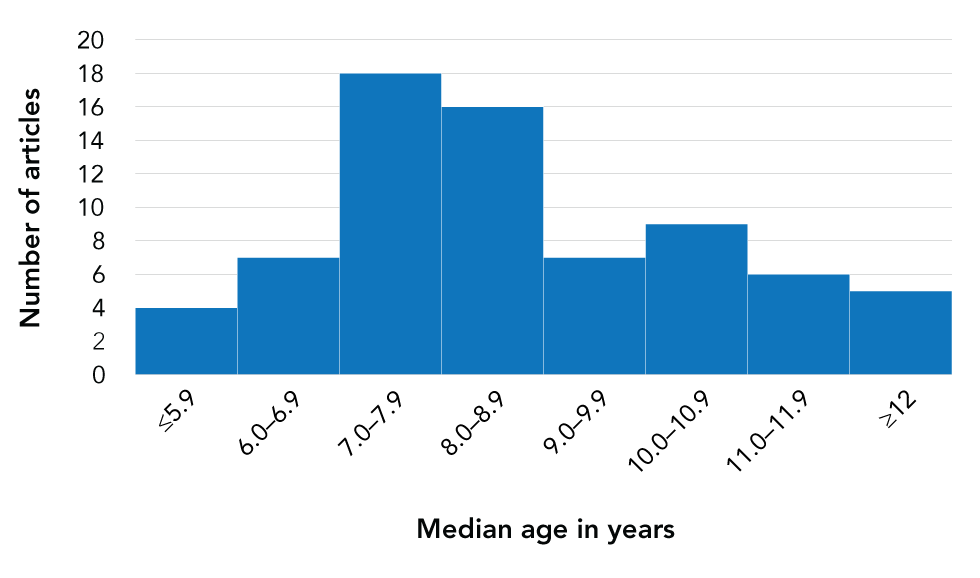

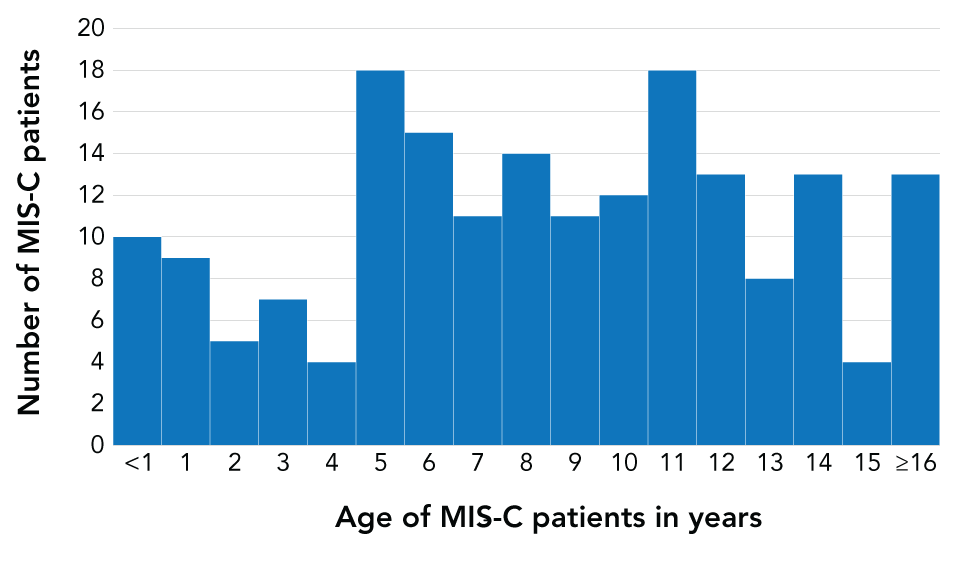

In the cohort articles, 50 of 72 (70%) articles reported the median age of MIS-C patients as between seven and 10 years (Figure 2). In addition, the median age of 184 patients reported in case reports was 8.8 years, ranging from one month to 20 years (23 cases did not have individual age data). However, MIS-C has been reported in all paediatric age groups, with wide ranges in many articles (Figure 3).

Figure 2: Median age of multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children cases presented in cohort articles (n=72)

Text description: Figure 2

This figure demonstrates the distribution of the median age in years in cohort articles from 7–10 years old.

Figure 3: Age of multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children patients reported in case report articles (n=101, MIS-C cases=185)

Text description: Figure 3

This figure demonstrates the age of MIS-C patients reported in case report articles indicating a wide range of ages.

More male than female MIS-C cases were identified in this review. Cohort articles that report on sex gave an overall average of 58% male, with 64 of 89 (72%) reporting more male MIS-C cases than female. Additionally, there were 115 males out of 197 patients identified in case reports, for a total of 58% male (10 cases did not have sex data).

Race, ethnicity and comorbidities

The distribution of race, ethnicity and comorbidities in MIS-C cases is less clear than of age and sex. This is in part because of the varied general population of the geographies represented in the articles and in part due to issues with incomplete data collection. In addition, race and ethnicity are known to affect the likelihood of becoming infected with COVID-19 initiallyFootnote 9Footnote 10Footnote 11Footnote 12Footnote 13 and could also affect the likelihood of developing MIS-C subsequently (Figure 4). This is a complex relationship, which few articles have sought to disentangle.

Figure 4: RelationshipFootnote a between general population, COVID-19 and MIS-C cases

Text description: Figure 4

There is evidence that racial and ethnic minority groups are disproportionately affected by COVID-19 (arrow 1). The effect of race and ethnicity on arrow 2 is less clear.

In the United States, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention states that, compared with White people, Black people are 1.1 times more likely to be infected and 2.8 times more likely to be hospitalized with COVID-19, while Hispanic people are 2.0 times more likely to be infected and 3.0 times more likely to be hospitalized with COVID-19Footnote 10. Many factors have been identified as causes of these disparities. Racial and ethnic minorities face several issues, including discrimination, access to health care and income inequality. Black and Hispanic people are also more likely to live in crowded housing and have a higher likelihood of being frontline workers, leading to higher risk of COVID-19 infectionsFootnote 11. These disparities and the resulting high burden of COVID-19 cases may partially or wholly explain the disproportionately high rates of MIS-C sometimes reported among Black and Hispanic populations.

Three articles describing large cohorts took a closer look at the relationship between race, ethnicity and MIS-C cases (Table 1). Overall, one article found a disproportionately high incidence of MIS-C in Black and Hispanic children compared to White children (incidence rate ratio of 3.15 and 1.70 respectively)Footnote 14. If race and ethnicity play no role in the development of MIS-C after COVID-19 (arrow 2 in Figure 4), the expectation is that a proportionate number of children of every race and ethnicity will develop MIS-C after COVID-19. Three studies suggest that this is not the case, and that Black children are overrepresented among MIS-C cases when compared to those hospitalized with COVID-19Footnote 14Footnote 15Footnote 16. Conversely, Hispanic children are underrepresented among MIS-C cases when compared to those hospitalized with COVID-19Footnote 14Footnote 15. There is also some evidence that White children are underrepresented among MIS-C cases when compared to those hospitalized with COVID-19Footnote 15Footnote 16.

| Racial and ethnic composition | % Composition | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lee et al.Footnote 14 (US)Table 1 footnote a (n=182) |

Feldstein et al.Footnote 15 (US)Table 1 footnote b (n=421) |

Swann et al.Footnote 16(UK) (n=651) |

||

| Black children | Percentage of Black children in the general paediatric population | 22.2% | N/A | N/A |

| Percentage of Black children among hospitalized paediatric COVID-19 cases | 19.9% | 21.5% | 7.4% | |

| Percentage of Black children among MIS-C cases | 34.4% | 32.3% | 17.3% | |

| Hispanic children | Percentage of Hispanic children in the general paediatric population | 35.6% | N/A | N/A |

| Percentage of Hispanic children among hospitalized paediatric COVID-19 cases | 40.0% | 45.4% | N/A | |

| Percentage of Hispanic children among MIS-C cases | 29.8% | 35.8% | N/A | |

| White children | Percentage of White children in the general paediatric population | 26.1% | N/A | N/A |

| Percentage of White children among hospitalized paediatric COVID-19 cases | 13.8% | 18.4% | 51.2% | |

| Percentage of White children among MIS-C cases | 12.8% | 11.7% | 30.8% | |

The most commonly reported comorbidities in the articles of children with MIS-C were asthma and obesity. However, one article found that MIS-C patients were more likely to have no comorbidities than acute COVID-19 patientsFootnote 15, while a second found that MIS-C patients are slightly more likely to be obese than those in the general populationFootnote 17. Overall, the evidence on comorbidities in MIS-C patients is relatively underdeveloped.

Outcomes

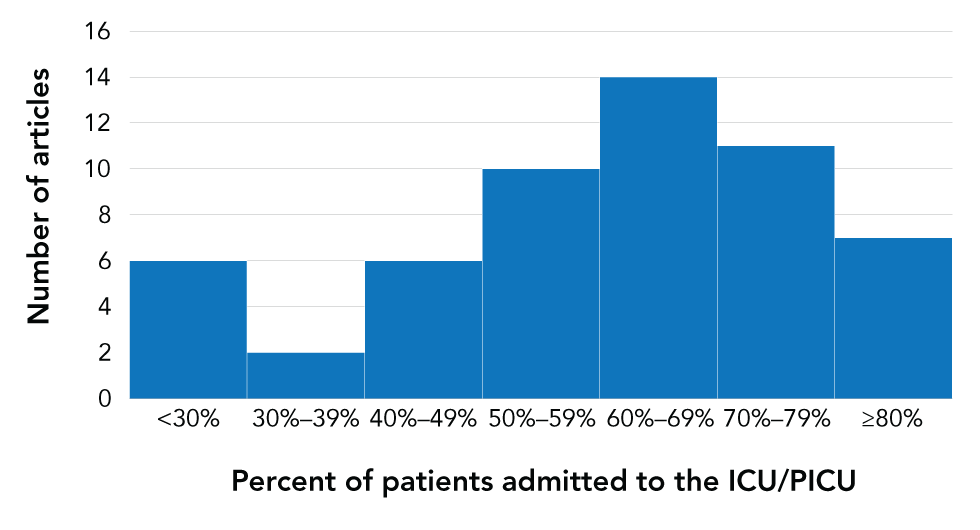

A large proportion of MIS-C patients (generally more than half) were admitted to an intensive care unit (ICU) or pediatric intensive care unit (PICU). In articles where ICU/PICU admission was not required as part of the study design, 56 cohort articles reported 62% of patients were admitted to ICU (Figure 5), while 80 case reports stated 78% of patients were admitted to ICU.

Figure 5: Percent of cases of multisystem inflammatory syndrome in paediatric patients admitted to ICU/PICU in cohort articles where ICU/PICU admission was not required by the study design (n=56)

Text description: Figure 5

This figure demonstrates that in articles where ICU/PICU admission was not required, 62% of patients were admitted to the ICU, while 78% were admitted to the ICU in case reports articles.

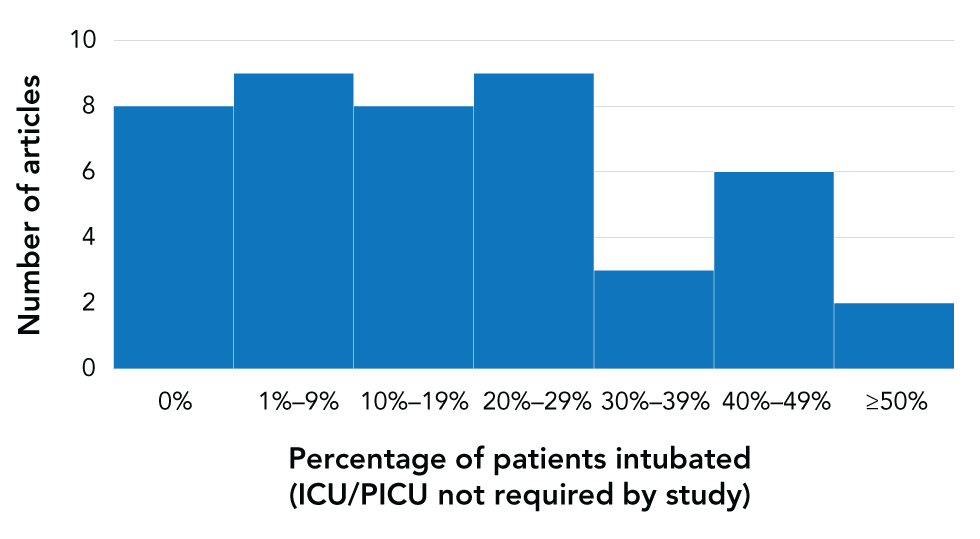

In addition, approximately one in five MIS-C patients required intubation. In articles where ICU admission was not required as part of the study design, 45 cohort articles reported 22% of patients were intubated (Figure 6). In addition, in 14 cohort studies that did require ICU/PICU admission, 32% of patients were intubated. Finally, 76 case reports stated 34% of patients required intubation.

Figure 6: Percent of cases of multisystem inflammatory syndrome in paediatrics patients that were intubated in cohort articles where the study design did not require ICU/PICU admission (n=45)

Text description: Figure 6

This figure demonstrates that only one in five patients required intubation (22%).

Generally, approximately 2% of MIS-C patients died. In 72 cohort articles that reported on outcomes, 2.0% of all patients died (n=78/3,977 cases), although 48 of 72 articles reported no deaths at all. In 88 case reports, 6.4% of all patients died. The case reports tend to highlight unique or more serious cases, which may explain why the overall mortality rate in these articles was much higher than in the cohort articles.

Discussion

There is a growing body of evidence outlining the epidemiological characteristics of MIS-C patients. It is clear that MIS-C affects children of all ages, with median age reported between seven and 10 years in 70% of articles. There seems to be proportionally fewer cases reported in children and young adults 16 years and older relative to rates of COVID-19 infection in these groups, but this may be due to many of the articles being based on work in paediatric hospitals. When compared with rates of COVID-19 cases, older teenagers and young adults in the US are more likely to be infected (or tested and identified as cases) than children, contrary to what has been reported about MIS-C rates so farFootnote 18.

The overrepresentation of male MIS-C cases is not seen in the rates of COVID-19 in children. In the US, male and female children are affected by COVID-19 roughly equally, with slightly higher rates in girlsFootnote 18. However, the slight overrepresentation of male children is also seen in Kawasaki Disease, a closely related condition that has a better-developed body of evidence available. There is some suggestion that the male overrepresentation is due to genetic factors in Kawasaki DiseaseFootnote 19, which could be explored further to determine if this is also the case for MIS-C.

In regard to race and ethnicity, it is well established that racial and ethnic minority groups are disproportionately burdened by COVID-19 cases because of sociodemographic and other related factorsFootnote 11Footnote 12Footnote 13. There is some evidence that Black and Hispanic children are disproportionately affected by MIS-C as well. The evidence presented here is from only two US and one UK study, and further studies are needed to verify these observations.

There is some evidence from studies on Kawasaki Disease that suggest genetic factors might play a role, with certain Asian groups being overrepresented amongst Kawasaki casesFootnote 20. Exploration of similar mechanisms in MIS-C would provide further insight.

In addition, comorbidities were inconsistently reported and are interrelated with other epidemiological factors, such as race and ethnicity. It is thus less clear how obesity, asthma and other comorbidities contribute to the development of MIS-C.

Finally, it is clear that MIS-C is a syndrome that causes serious symptoms that require hospitalization and often admission to an ICU or PICU. Access to adequate care, including intubation in severe cases, is critical in the treatment of MIS-C.

Conclusion

Multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children can affect children of all ages, with a median age most commonly reported between seven and 10 years. Males were more often affected (58% of cases). Many patients, often more than half, were admitted to the ICU or PICU, with a fifth requiring intubation. Between 0% and 2% of MIS-C patients died, depending on the context and available treatment. More evidence is needed on the role of race, ethnicity and comorbidities in the development of MIS-C. Future avenues of study include surveillance reports targeting incidence, along with studies on sequelae.

Authors’ statement

- MS — Methodology, investigation, writing–original draft

- RE — Conceptualization, writing–review and editing, supervision

- NB — Writing–review and editing

- LW — Writing–review and editing

- T-LB — Writing–review and editing

- ET — Writing–review and editing

- MEJ — Writing–review and editing

- SB-A — Writing–review and editing

Competing interests

None.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the work of the Emerging Science Group for allowing us to collaborate with them on this important issue.

Funding

None.

Supplemental material

Summary of evidence on multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (n=195)

Appendix A: Definitions of multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children

The definition of multisystem inflammatory syndrome (MIS-C) published by the World Health OrganizationFootnote 3 states:

- Children and adolescents 0–19 years of age with fever for more than three days

AND

- Two of the following:

- Rash or bilateral non-purulent conjunctivitis or muco-cutaneous inflammation signs (oral, hands or feet)

- Hypotension or shock

- Features of myocardial dysfunction, pericarditis, valvulitis, or coronary abnormalities (including ECHO findings or elevated Troponin/NT-proBNP)

- Evidence of coagulopathy (by PT, PTT, elevated d-Dimers)

- Acute gastrointestinal problems (diarrhoea, vomiting, or abdominal pain)

AND

- Elevated markers of inflammation such as erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), C-reactive protein (CRP), or procalcitonin

AND

- No other obvious microbial cause of inflammation, including bacterial sepsis, staphylococcal or streptococcal shock syndromes

AND

- Evidence of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) (reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR), antigen test or serology positive), or likely contact with patients with COVID-19

The case definition of MIS-C published by the United States Centers for Disease ControlFootnote 4 states:

- An individual aged younger than 21 years presenting with fever (greater than 38.0°C for greater than or equal to 24 hours, or report of subjective fever lasting greater than or equal to 24 hours), laboratory evidence of inflammation, and evidence of clinically severe illness requiring hospitalization, with multisystem (more than two) organ involvement (cardiac, renal, respiratory, hematologic, gastrointestinal, dermatologic or neurological)

AND

- No alternative plausible diagnoses

AND

- Positive for current or recent severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) infection by RT-PCR, serology, or antigen test; or exposure to a suspected or confirmed COVID-19 case within the four weeks prior to the onset of symptoms

The definition of pediatric inflammatory multisystem syndrome (PIMS) released by the United Kingdome Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health (RCPCH)Footnote 5 states:

- A child presenting with persistent fever, inflammation (neutrophilia, elevated CRP and lymphopenia) and evidence of single or multi-organ dysfunction (shock, cardiac, respiratory, renal, gastrointestinal or neurological disorder) with additional features. This may include children fulfilling full or partial criteria for Kawasaki disease

AND

- Exclusion of any other microbial cause, including bacterial sepsis, staphylococcal or streptococcal shock syndromes, infections associated with myocarditis such as enterovirus (waiting for results of these investigations should not delay seeking expert advice)

AND

- SARS-CoV-2 PCR testing may be positive or negative

The definition of PIMS released by the Canadian Paediatric SocietyFootnote 6Footnote 7 states:

- Persistent fever (higher than 38.0°C for three or more days) and elevated inflammatory markers (CRP, ESR, or ferritin)

AND one of both of the following:

- Features of Kawasaki disease (complete or incomplete)

- Toxic shock syndrome (typical or atypical)

AND

- No alternative etiology to explain the clinical presentation

AND

- Patients need not have positive SARS-CoV-2 status for consideration