Health equity and First Nations, Inuit and Métis peoples

Download this article as a PDF

Download this article as a PDF Published by: The Public Health Agency of Canada

Issue: Volume 48-4, April 2022: First Nations Health

Date published: April 2022

ISSN: 1481-8531

Submit a manuscript

About CCDR

Browse

Volume 48-4, April 2022: First Nations Health

Overview

Supporting health equity for First Nations, Inuit and Métis peoples

Margo Greenwood1,2,3, Donna Atkinson1, Julie Sutherland1

Affiliations

1 National Collaborating Centre for Indigenous Health, University of Northern British Columbia, Prince George, BC

2 School of Education, University of Northern British Columbia, Prince George, BC

3 First Nations Studies Program, University of Northern British Columbia, Prince George, BC

Correspondence

Suggested citation

Greenwood M, Atkinson D, Sutherland J. Supporting health equity for First Nations, Inuit and Métis peoples. Can Commun Dis Rep 2022;48(4):119–23. https://doi.org/10.14745/ccdr.v48i04a01

Keywords: health equity, First Nations, Inuit, Métis, public health, Indigenous, Canada

Abstract

The National Collaborating Centre for Indigenous Health (NCCIH) is unique among the National Collaborating Centres as the only centre focused on the health of a population. In this fifth article of the Canada Communicable Disease Report’s series on the National Collaborating Centres and their contribution to Canada’s public health response to the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic, we describe the work of the NCCIH. We begin with a brief overview of the NCCIH’s mandate and priority areas, describing how it works, who it serves and how it has remained flexible and responsive to evolving Indigenous public health needs. Key knowledge translation and exchange activities undertaken by the NCCIH to address COVID-19 misinformation and to support the timely use of Indigenous-informed evidence and knowledge in public health decision-making during the pandemic are also discussed, with a focus on acting on lessons learned moving forward.

Introduction

The National Collaborating Centres (NCCs) for Public Health (NCCPH) were established in 2005 as part of the federal government’s commitment to renew and strengthen public health infrastructure in Canada following the 2003 severe acute respiratory syndrome epidemicFootnote 1. Funded by the Public Health Agency of Canada, the NCCs promote and support the timely use of scientific research and other knowledges in public health practice, programs and policies in Canada Footnote 2. The NCCs work to identify knowledge gaps and needs to stimulate research in public health priority areas, synthesize and disseminate new and existing research into user-friendly formats, and foster networks and collaborations among public health professionals, policy-makers and researchers. Hosted by academic or government organizations across Canada, each NCC focuses on a specific area of public health: Indigenous Health; Environmental Health; Infectious Diseases; Knowledge Translation Methods and Tools; Healthy Public Policy; and Determinants of HealthFootnote 2. In this brief overview, we will present the mandate and priority areas of the National Collaborating Centre for Indigenous Health (NCCIH), along with descriptions of how NCCIH works, who it serves and how it adapted to evolving Indigenous public health needs during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic.

National Collaborating Centre for Indigenous Health: Sharing knowledge, making a difference

Situated on the traditional territory of the Lheidli T’enneh First Nation in Prince George, British Columbia (BC), the NCCIH, formerly the NCC for Aboriginal Health,Footnote 3 is hosted at the University of Northern British Columbia—a small, research-intensive university serving rural, remote and northern populations. The NCCIH’s mandate is to strengthen public health systems and support health equity for First Nations, Inuit and Métis peoples in Canada through knowledge translation and exchange. This work is guided by four overarching principles intended to 1) respect diversity and the unique interests of First Nations, Inuit and Métis peoples, 2) support the inclusion and participation of First Nations, Inuit and Métis peoples in the public health system, 3) incorporate Indigenous knowledge and holistic approaches and 4) encourage collaboration and capacity building. The NCCIH applies these principles to its work in several key priorities areas that reflect our understanding of, and approach to, transforming Indigenous public health in Canada.

Priority areas

Key priority areas are informed by direct and ongoing engagement with public health stakeholders and community members through a variety of methods, including convening national gatherings, supporting and participating in networks and committees, conducting environmental scans and literature reviews, administering surveys and undertaking focus groups and key informant interviewsFootnote 2. The NCCIH Advisory Committee, composed of First Nations, Inuit, Métis and non-Indigenous public health experts from across the country, provides strategic direction and advice to the NCCIH and offers ongoing feedback on strategic priorities to ensure the work’s relevance to First Nations, Inuit and Métis peoples and communities. With the eight-year renewal of the NCC program in 2019, the NCCIH’s priority areas remain committed to addressing emerging Indigenous public health issues.

The NCCIH has seven key priority areas. The first priority area is focused on the social determinants of health, or the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work and age that influence health outcomesFootnote 4. As part of this work, NCCIH looks “beyond the social” to the determinants of health specific to First Nations, Inuit and Métis peoples, such as colonization, systemic racism and intergenerational traumaFootnote 5. Given that gender interacts with other determinants of health to influence health risks, outcomes, behaviours, opportunities and experiences across a person’s lifespan, the NCCIH’s activities and resources use gender-based analysis plus (GBA+) and other Indigenous-specific gender-based analysis tools and strategies to consider the unique experiences of Indigenous men, women, boys, girls and lesbian, gay, bisexual, transsexual, transgendered, intersexual, queer, questioning, two-spirited (LGBTTIQQ2S) in public health policies, programs and initiatives. Second, First Nations, Inuit, and Métis child, youth and family health is another important priority area because families and communities are not only an important source of strength and safety but also the place where health and wellness begins and thrives. Third, Indigenous people’s relationships with and dependence on the land, waters, animals, plants and natural resources for their sustenance, livelihoods, cultures, identities, health and well-being are prioritized. Fourth, we work to address the disproportionate burden of chronic and infectious diseases on Indigenous populations by sharing knowledge and fostering dialogue on issues such as tuberculosis, sexually transmitted and bloodborne infections, and COVID-19Footnote 6. Fifth, to support Indigenous perspectives and approaches to United Nation’s 2030 Agenda for Sustainable DevelopmentFootnote 7 and Canada’s Agenda National StrategyFootnote 8, NCCIH also focus on key aspects of the sustainable development goals such as reduced inequalities, climate action and poverty. Recognizing that Indigenous knowledges and perspectives are foundational to evidence-based decision-making, the NCCIH’s sixth priority area is focused on the integration and application of diverse knowledge systems in public health. Finally, to address systemic anti-Indigenous racism in healthcare systems, the NCCIH prioritizes the development of knowledge products and activities on cultural safety and respectful relationships. The NCCIH website provides evidence-based, Indigenous-specific resources and tools in each of these priority areas. Demand for credible, user-friendly and culturally relevant information is reflected in the NCCIH’s growing number of unique and returning visitors to the NCCIH’s website, which increased by 47% and 51%, respectively, in the last fiscal year.

Conceptual change model

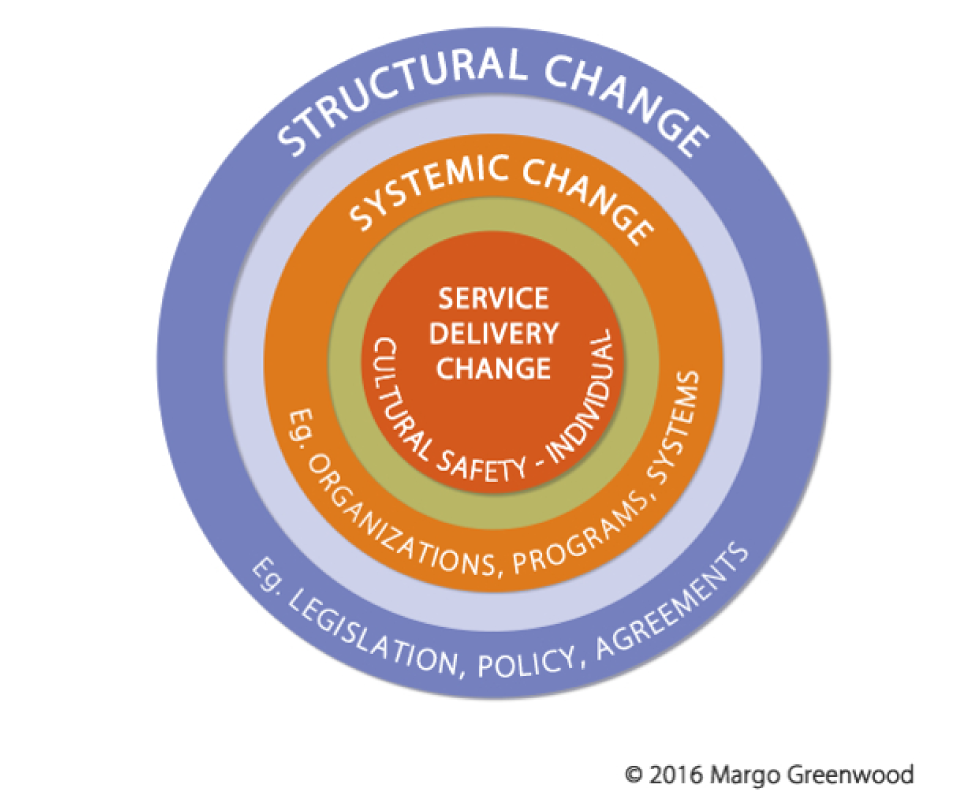

The NCCIH’s approach to Indigenous public health transformation is grounded in a conceptual change model (Figure 1)Footnote 9 illustrated by three interconnected layers: structural change; systemic change; and service delivery changeFootnote 9. The change model incorporates social determinants and Indigenous determinants of health approaches and a life course perspective, all of which are necessary for the multi-level, cross-disciplinary, concurrent implementation of policies, programs and practices to address health inequities of Indigenous peoples over the long term.

Figure 1: Conceptual change model of National Collaborating Centre for Indigenous Health’s approach to Indigenous public health transformation

Text description: Figure 1

The figure is a concentric circle. The outer ring is purple; a line of text at the top of this ring reads Structural Change; a line of text at the bottom of this ring reads Eg. legislation, policy, agreements. The next ring, one closer to the centre, is light purple and has no text. The third ring from the outside is orange; a line of text at the top of the orange ring reads Systemic Change; a line of text at the bottom of this ring reads Eg. organizations, programs, systems. The ring closest to the centre is green and has no text. The centre of the circle is dark orange; a line of text at the middle of the centre reads Service Delivery Change; a line of text at the bottom of the centre reads Cultural Safety – Individual.

The outer layer of the model refers to the “big super structures” like high-level policies, legislation and/or formal agreements that are enablers of structural change. In Canada, examples of these big structural enablers include the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s (TRC) Calls to Action, the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (MMIWG) Calls for Justice, and the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP). The NCCIH has consistently identified, evolved and responded to these high-level policies, legislation and formal agreements by mobilizing knowledge to increase understanding and application of Indigenous-informed evidence at the policy level.

The second layer depicted in the change model refers to systemic change at the level of organizations and agencies responsible for operationalizing change, such as hospitals, schools, early childhood programs, child welfare agencies and mental health and addictions programsFootnote 9. Since its inception, NCCIH has mobilized knowledge to reduce inequities in Indigenous health at the program and organizational level by producing environmental scans, literature reviews, fact sheets, guidance documents and health promotion resources to inform evidence-based decision-making and adoption of best or promising practices. At the very centre of the model is service delivery change, where individuals interact with each other in providing or receiving healthcare or other servicesFootnote 9. The NCCIH has worked diligently over the last 16 years to develop resources and activities to deepen understanding, awareness, reflection and action at the individual or practice level, including the importance of cultural safety and respectful relationships.

National Collaborating Centre for Indigenous Health in the time of COVID-19

With the emergence of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) in late 2019, the NCCIH quickly mobilized to stop the spread of COVID-19 misinformation and to support the use of Indigenous-informed evidence and knowledge in public health decision-making. It began by establishing a COVID-19 quick links page on its website to provide reliable and timely information in response to the global explosion of research and information on COVID-19Footnote 10. In collaboration with Indigenous Services Canada, it also created a COVID-19 resource library to provide easy access to over 370 First Nations, Inuit and Métis-specific resources and tools in English, French and multiple Indigenous languages. Published by both Indigenous and non-Indigenous researchers and organizations, the curated resource library covers a wide range of topics (e.g. barriers to care, harm reduction, infection prevention and control, emergency management) and formats (e.g. information sheets, posters, videos, protocols and guidelines, reports and journal articles). In addition to this preliminary work and to act on lessons learned, NCCIH conducted a survey of stakeholders in the spring of 2020 to identify ongoing and emerging knowledge needs and gaps related to First Nations, Inuit and Métis peoples and COVID-19. The survey aimed to inform the work moving forward for resource and tools development, as well to establish new partnerships and collaborations. The COVID-19 priority areas identified by survey respondents included mental health and wellness, stigma and discrimination, public health messaging, substance use, addictions and harm reduction, and housing and homelessness. With these priority areas in mind, NCCIH spent the subsequent months working with Indigenous health researchers, program managers, policy-makers, health professionals, government and national Indigenous organizations on a number of COVID-19 initiatives: webinars and podcasts; fact sheets; animated videos; reports; and a national survey on access to healthcare services during the pandemic.

Over a four-week period from January to February 2021, NCCIH delivered a series of webinars as part of its COVID-19 and First Nations, Inuit and Métis people’s virtual gathering. Delivered in collaboration with Indigenous organizations and scholars from coast-to-coast-to-coast, the 2.5 hour webinars focused on key topic areas, including Indigenous Governance and Self-Determination in Planning and Responding to COVID-19Footnote 11, Socio-Economic Impacts of COVID-19 on the Health and Well-Being on First Nations, Inuit and Métis PopulationsFootnote 12, Data Collection on COVID-19 Cases in First Nations, Inuit and Métis Populations and CommunitiesFootnote 13, and Innovative Public Health Messaging on COVID-19 and Indigenous PeoplesFootnote 14. Engagement in the webinar series was significant, with over 3,800 individuals registering from various sectors, including Indigenous organizations, local and regional public health units, health authorities, hospitals, universities or research centres, federal, provincial and territorial governments and non-profit organizations. Post-webinar survey data indicated that 94%–97% of respondents rated the webinars as excellent or very good and that the webinars enhanced their knowledge. Respondents also offered comments on the webinars, noting they were extremely informative, thought-provoking and a great mixture of academic, personal and experiential/artistic perspectives. In addition to the webinars, the Centre published a number of podcasts as part of our “Voices from the Field” series on topics such as grief, mourning and mental health Footnote 15, how to stay connected to traditions and ceremonies during a pandemicFootnote 16, respecting our EldersFootnote 17 and public health considerations for COVID-19 in evacuations of northern Indigenous communities Footnote 18.

In partnership with BC’s Northern Health Authority’s Indigenous Health branch, the NCCIH also developed resources to address COVID-19 and stigma, including the animated videos “Healing in Pandemic Times: Indigenous Peoples, Stigma and COVID-19”Footnote 19 and “There is no Vaccine for Stigma: A Rapid Evidence Review of Stigma Mitigation Strategies During Past Outbreaks Among Indigenous Populations Living in Rural, Remote and Northern Regions of Canada and What Can Be Learned for COVID-19”Footnote 20. To support the rollout of COVID-19 vaccines in Canada, NCCIH also worked with several organizations to share and exchange knowledge to better understand vaccine hesitancy and promote vaccine confidence generally among First Nations, Inuit and Metis peoples. Key activities done in partnership with the NCC for Infectious Diseases included a webinar on vaccine hesitancy and potential implications during the COVID-19 pandemic, with over 900 attendeesFootnote 21, an animated video on building vaccine confidenceFootnote 22, and a series of fact sheets on vaccine confidence and vaccine preventable diseases for Indigenous peoples and healthcare professionalsFootnote 23. Additionally, the NCCIH published two articles in partnership with the Royal Society of Canada: “Vaccine Mistrust: A Legacy of Colonialism”Footnote 24 and “Enhancing COVID-19 Acceptance in Canada”Footnote 25. Finally, in partnership with Public Health Agency of Canada, NCCIH and NCC for Infectious Diseases are leading the development of a national survey on access to healthcare services during the pandemic, with a focus on sexually transmitted and blood-borne illnesses and harm-reduction services.

Conclusion

Through knowledge sharing, partnerships and collaboration, community engagement and rapid response to emerging public health challenges such as COVID-19, NCCIH joined the other NCCs in renewing and strengthening public health infrastructure in Canada. In its unique position among the NCCs of focusing on a specific, though diverse, population, the NCCIH strives to confront determinants of health that affect First Nations, Inuit and Métis peoples. Its conceptual change model created a foundation from which to work to address inequities at service delivery, systemic and structural levels and build a just society for all Indigenous peoples in Canada.

Authors’ statement

All authors are equal contributors to this paper.

The content and view expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Government of Canada.

Competing interests

None.

Acknowledgements

None.

Funding

The NCCIH is funded by the Public Health Agency of Canada.