Status report – FoodReach Toronto: lowering food costs for social agencies and community groups

Health Promotion and Chronic Disease Prevention in Canada

Paul Coleman, PhDFootnote 1; John Gultig, MEdFootnote 2; Barbara Emanuel, MESFootnote 1; Marianne Gee, PhDFootnote 3; Heather Orpana, PhDFootnote 3,Footnote 4

https://doi.org/10.24095/hpcdp.38.1.05

Author references:

- Endnote 1

-

Toronto Food Strategy, Toronto Public Health, Toronto, Ontario, Canada

- Endnote 2

-

Pitch Communications Ltd, Toronto, Ontario, Canada

- Endnote 3

-

Public Health Agency of Canada, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada

- Endnote 4

-

School of Psychology, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada

Correspondence: John Gultig, 277 Victoria St, 2nd Floor, Suite 200, Toronto, ON M5B 1W2; Tel: 416-338-7864; Email: jgultig@pitchcommunications.com

Abstract

Toronto has the largest absolute number of food insecure households for any metropolitan census area in Canada: of its 2.1 million households, roughly 252 000 households (or 12%) experience some level of food insecurity. Community organizations (including social agencies, school programs, and child care centres) serve millions of meals per year to the city's most vulnerable citizens, but often face challenges accessing fresh produce at affordable prices. Therefore in 2015, Toronto Public Health, in collaboration with public- and private-sector partners, launched the FoodReach program to improve the efficiency of food procurement among community organizations by consolidating their purchasing power. Since being launched, FoodReach has been used by more than 50 community organizations to provide many of Toronto's most marginalised groups with regular access to healthy produce.

Keywords: food security, food sustainability, food system, alternative food network, food procurement, healthy diet

Highlights

- The objective of FoodReach is to provide community agencies with regular and predictable access to affordable, fresh food in Toronto.

- Food purchased through FoodReach is used to prepare meals and snacks for children, low-income families, people experiencing homelessness and other groups.

- These meals are often the only source of healthy food accessed by people within these communities in a day.

- In its first year (May 2015 to April 2016), FoodReach worked with more than 50 community organizations to improve their access to affordable produce.

Introduction

Food insecurity, defined as inadequate access to food due to financial constraints, affects approximately 2.2 million CanadiansFootnote 1 and approximately 10% of Canadian households with children.Footnote 2 Food insecurity often accompanies other social determinants of health including poverty, unemployment and lower levels of education, and disproportionately impacts vulnerable groups such as children, single parent families, Canadian newcomers, and Canada's first inhabitants-Indigenous communities.Footnote 2 It is associated with a range of chronic health conditions including diabetes, heart disease, osteoporosis and obesityFootnote 3,Footnote 4 and higher health care spending.Footnote 5Household food insecurity is also associated with an increased risk of emotional and behavioural problems among children, which can have lasting effects throughout their lifetime.Footnote 6,Footnote 7

Within Canada, the prevalence of food insecurity varies considerably between municipalities.Footnote 8 Toronto has a food insecurity rate that nears the Canadian average, but because of its large population size, has the largest absolute number of food insecure households for any census metropolitan area in Canada. More specifically, of Toronto's 21 million households, roughly 252 000 households (or 12%) experienced some level of food insecurity in 2011-2012.Footnote 8 It is a problem that is growing rather than declining:Footnote 9 between 2008 and 2016 the food banks in Toronto increased in use by 12%.Footnote 10

As is the case in many Canadian citiesFootnote 11, Toronto tackles food insecurity through various mechanisms including charitable models (e.g. food banks), household support models (e.g. community gardens and community kitchens) and community food system models that seek to maximize partnerships to increase local food security.Footnote 4 In Toronto more than 1000 community agencies, 750 school-based Student Nutrition Programs (SNPs) and 900 child care centres serve millions of meals per year to some of the city's most vulnerable groups. Research undertaken by Toronto Public Health revealed that many community organizations face challenges accessing fresh, affordable food.Footnote 12 Typically, their food supply chains rely on small budgets, unpredictable donations, little negotiating power when entering contracts with large food service providers, and reliance on volunteers.

In 2013, as part of the Toronto Food Strategy, Toronto Public Health began assessing the feasibility of various systemic and sustainable models for improving the efficiency of food procurement and reducing dependence on charitable donations among community organizations. In 2015, the FoodReach initiative was launched as a collaboration between public, community and private sector partners to address this systemic problem.

The FoodReach initiative

The objectives of FoodReach are two-fold:

- To provide community agencies with regular and predictable access to affordable, fresh food. Through its Buying Portal, FoodReach aims to aggregate the collective purchasing power of its members, regardless of their size, to provide access to fresh produce at wholesale prices-a benefit which in the past was only available to large organizations.

- To strengthen the system that supports marginalised communities in Toronto. Through its Knowledge Exchange Portal, FoodReach also aims to enable agencies to share existing knowledge and resources in order to build systemic capacity in healthy food preparation at lower costs.

The Buying Portal

The FoodReach Buying Portal (www.foodreach.ca) is an online system through which individual community organizations can order fresh fruit, vegetables, dairy, eggs and bread from a variety of suppliers. The Buying Portal combines a user-friendly "front-end" food ordering website for community organizations and a "back-end" processing website for food consolidators (private businesses that sell food products to other businesses). Consolidators source fresh produce from the Ontario Food Terminal (OFT)-the main produce distribution centre for Toronto and third largest food terminal in North America-as well as local farmers, and deliver it to members the next day.

The ability to access fresh produce daily at wholesale prices from a public institution like the OFT is critically important to FoodReach. It is a one-stop point at which produce can be purchased, and then delivered. Given the number of consolidators working out of the OFT, it provides healthy competition and thus good prices. Another important dimension of FoodReach is that there is no delivery fee and a low minimum order requirement of only $50. This is important because many of the organizations working with marginalised communities are small scale and food is often not a major line item in their budgets. In some cases, it is not budgeted for at all. This has led to agencies serving unhealthy food-coffee and muffins for breakfast, as an example-to children, low-income families, people experiencing homelessness and other forms of marginalisation.Footnote 13 Yet, for many, this food is sometimes their only source of food for the day. FoodReach attempts to provide agencies with a cost-effective source of better food.

The Knowledge Exchange Portal

FoodReach's Knowledge Exchange Portal aims to provide a platform for community organizations to collaborate, share resources and menu ideas, access training materials, and learn more about healthy diets and the local food system. This is especially important because many of those who buy and prepare food within community organizations are untrained cooks who serve meals on limited budgets. It is also an attempt to 'knit together' a large community of organizations who, despite being united by similar missions, tend not to collaborate sourcing food or delivering meal programs.Footnote 13

The Knowledge Exchange Portal has been designed to increase organizational confidence, knowledge, and motivation to encourage healthy food purchasing, healthy meal preparation, and ultimately to facilitate lasting behaviour change among community organizations that provide meals to vulnerable populations in Toronto.

A new and more interactive knowledge exchange portal was launched in December 2016. It works in tandem with a renewed social media campaign that both informs agencies of what FoodReach offers and provides useful information, like what fresh produce is peaking in price (and so should be avoided), and what a useful substitute is.

Operations and governance structure of FoodReach

FoodReach is a social enterprise that brings together public, private and government organizations, and is incorporated as a not-for-profit organization.

FoodReach is governed by a small board of directors comprising the City of Toronto, Student Nutrition Toronto, the Parkdale Activity-Recreation Centre (PARC)-an NGO that works with members on issues of poverty and mental health-and a key community stakeholder, STOP Community Food Centre. Figure 1 presents a diagram of the governance structure of FoodReach.

Figure 1 text description

As can be seen in this figure, FoodReach operates for its members, which are mainly child care centres, community agencies and Student Nutrition Programs. The organization is governed by a small board of directors comprising the City of Toronto, Student Nutrition Toronto, the Parkdale Activity-Recreation Centre (PARC)-an NGO that works with members on issues of poverty and mental health-and a key community stakeholder, STOP Community Food Centre. An Operations Committee is responsible for implementing FoodReach's day-to-day activities. FoodReach also continues to call on external advisors and partners, including the Canadian Diabetes Association, the City of Toronto social procurement working group, Creating Health Plus, the Metcalf Foundation, the Ontario Food Terminal, the Parkdale Activity-Recreation Centre and the Public Health Agency of Canada, to provide regular insights that enable FoodReach to refine their operations and social mission on a regular basis.

An Operations Committee-responsible for implementing FoodReach's day-to-day activities-was established in late August 2016. FoodReach also continues to call on external advisors and partners to provide regular insights that enable FoodReach to refine their operations and social mission on a regular basis.

A lot of thought went into the kind of structure needed. The guiding principles were that it should provide a forum through which members can contribute ideas, a board that can ensure that funds are raised efficiently and that operations are carried out in the manner members desire, and an operations committee that works with a high degree of independence to grow the organization. Given that the initiative straddles public, private and civic space, the FoodReach governance structure works to ensure that all are represented, heard and understood.

Results (the first 21 months)

In its first year–May 2015 to April 2016–an average of 23 members placed orders through the FoodReach portal each month, ranging from one member in May 2015 to 39 members in November 2015. By comparison, an average of 42 members placed orders through FoodReach each month in its second year so far–May 2016 to January 2017, fluctuating from 40 in May 2016 to 57 members in January 2017 (Figure 2).

Figure 2 text description

This figure depicts the number of members ordering with FoodReach between May 2015 and January 2017. In its first year-May 2015 to April 2016-an average of 23 members placed orders through the FoodReach portal each month, ranging from one member in May 2015 to 39 members in November 2015. By comparison, an average of 42 members placed orders through FoodReach each month in its second year so far-May 2016 to January 2017, fluctuating from 40 in May 2016 to 57 members in January 2017.

The total number of active members-those regularly ordering through FoodReach-has grown consistently. A sharp increase in activity is evident from September 2016, which corresponds with FoodReach hiring three new members of staff, bringing a second consolidator on board, and starting to serve both SNPs and child care centres. As the new project manager, Alvin Rebick, explained in a December 2016 interview, this "is really the point when we moved away from pilot to full implementation. Although we are still learning and there are still problems, we are now better equipped to deal with them." Given the increasing rate at which active users are coming aboard, it is highly likely that by the end of year two FoodReach will, minimally, have doubled the number of agencies purchasing through its portal.

In contrast, total membership now constitutes about 10% of the approximately 2500 agencies that FoodReach was established to support. Over 200 members are now registered on the FoodReach portal but many are still not active users.

FoodReach's ongoing "implementation research"Footnote 15 has revealed that the hesitance in coming aboard is multi-faceted: many are simply reluctant to leave relationships with existing suppliers, others prefer the high touch relationships they currently have to an online system, while a few don't recognise any price advantage.

Most of all, the research shows that the major impediment is a lack of knowledge of what FoodReach offers. This seems to be borne out by the rapid increase in use once a more systematic outreach programme was adopted, problems with suppliers were resolved, and a more accessible website was launched.

Membership, and active membership, is important. But so is 'spend' per member. In order to attract private sector suppliers-who are important to long-term sustainability -the average spend per member must be attractive. This is challenging given that the reason FoodReach was established was because many of these agencies are so small that they cannot leverage economies of scale, and FoodReach's combining of purchasing power was an attempt to do so.

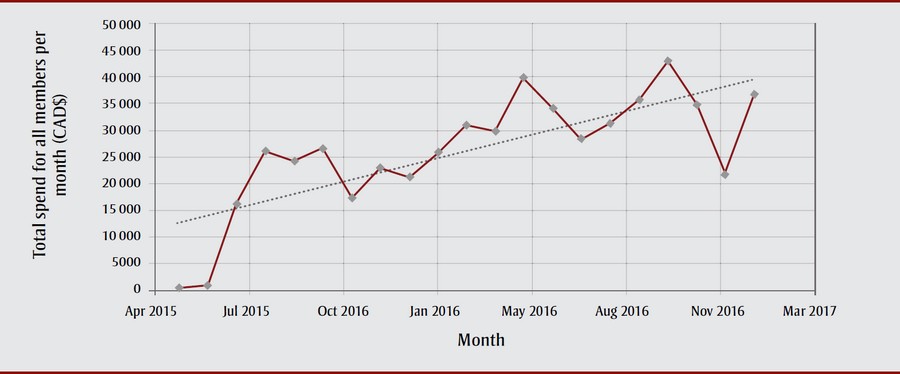

In May 2015, just one agency spent $490 through the FoodReach portal. In January 2017, 57 members spent $38 000 through the portal; a 75-fold increase in overall spend (Figure 3).

Figure 3 text description

This figure presents the total spent monthly by all members through FoodReach, between May 2015 and January 2017. In May 2015, one single agency spent $490 through the FoodReach portal. In January 2017, 57 members spent $38 000 through the portal; a 75-fold increase in overall spend.

Average member spend has also increased from $490 to about $670 per month. In October 2016, 54 members spent $43 000-almost $800 per agency-through the portal, the best per month spend so far for FoodReach. Late 2016 showed a dip in sales, due to the increase in food donations received by community agencies and the closure of schools. Data from January 2017 indicates that sales have returned to their pre-dip levels, and are increasing again.

Successes and challenges

To help inform the initiative, FoodReach conducted implementation research to document challenges and opportunities that community organizations face when buying fresh produce. The early 2016 research-using a mixed-methods approach that incorporated both qualitative and quantitative data collection, and approved by the Toronto Public Health Research Ethics Board-included a series of 17 user and non-user interviews. These interviews were run again in late 2016 to track how users rated FoodReach, and what was keeping non-users from participating.

From these interviews, the program learned that member organizations most valued the 'quality and freshness of produce', while the free next-day delivery and small minimum orders were viewed as the biggest advantages of using FoodReach. The latter was especially important for the many small agencies with limited storage space.

Most organizations using FoodReach liked the idea of an online buying portal to purchase fresh produce, but a number spoke of the buying portal as a little alienating. This was, in part, due to a preference for talking directly to their contact via telephone. It was also due to FoodReach's design-a double sign-in-and confusing labelling by consolidators which led to buyers being unsure of prices and quantities being offered. Both of these problems have now been addressed.

Organizations reported that FoodReach had increased the quantity and frequency of healthy food served in their meal programs. It had also simplified food preparation because, rather than having to make do with what they received in terms of food donations-which changed from day-to-day and, thus, made menu planning challenging, especially for the many untrained cooks-food deliveries were now predictable.

The issue of food prices and overall food costs was complex. Many organizations spoke of FoodReach reducing cost, both in terms of dollars spent as well as the amount of staff time needed to purchase and pick up fresh produce. But this issue requires further research, since several agencies did not consider-or budget for-travel time and staff time as part of the 'costs' of fresh food procurement. Agencies that did focus on overall cost of procurement and factored in time were more likely to offer 'reduced costs' as a benefit of the FoodReach programFootnote 16.

Almost all agencies believed in FoodReach's broader social goals of increasing control of the food supply chain and improved knowledge exchange. However, most members found that the Knowledge Exchange Portal was underdeveloped and requested more information on seasonal pricing, nutritional information, preparing halal, and sharing menus, amongst other things. Agencies also expressed an interest in receiving rebates and a number of non-users believed they were too small to use FoodReach. Other agencies had long-term contracts in place with existing suppliers. These findings were incorporated into a re-design of the FoodReach knowledge exchange portal.

Through its initial implementation, FoodReach also encountered some barriers working with food consolidators. Historically, the majority of food consolidators received produce orders from community organizations by phone, and uptake of the FoodReach web portal was a technological challenge for some. In other cases, consolidators already had individual online ordering systems in place and considerable financial resources were required to enable compatibility of these systems with the FoodReach portal. This unexpected challenge has consumed a lot of FoodReach's time and budget, and continues to be an area of significant work.

Future directions

Prior to the development of FoodReach, community agencies sourced food for meal programs through a range of mechanisms and consolidators, mostly in isolation. By bringing agencies together, FoodReach aggregates and leverages the collective purchasing power of community organizations to obtain wholesale pricing on fresh produce and improve the efficiency of delivery. Not only does this program help lower food costsFootnote 17 in many cases, it also seeks to improve nutritional quality of meals, build communities, provide educational material, connect producers to consumers, and provide members with the opportunity to take control of the local food system.

The ability of the FoodReach program to deliver these opportunities is expected to increase as the program matures, with the expansion of human resource capacity, continued negotiations with food consolidators, and continued and increased participation by community organizations, municipal government and student nutrition programs.

Two other important food security initiatives currently being discussed by Toronto Public Health's Food Strategy group demonstrate the potential power of the FoodReach idea. Toronto Community Housing is considering establishing community food buying clubs, and Toronto Public Health is discussing the idea of social supermarkets for low-income neighbourhoods. Both would benefit from having FoodReach as a potential buying portal through which they can access fresh food at wholesale prices.

Furthermore, the development of the Knowledge Exchange Portal will offer new features to community organizations, such as training programs, information on substituting food items for healthier options, and information on seasonal pricing. It is anticipated that these new features will support community organizations by providing skills and knowledge to take control of the food system. Finally, FoodReach is refining its website to include analytics that will provide FoodReach and Toronto Public Health with the ability to monitor the impact of the program over time and document improvements in the quantity and quality of food served in community meal programs.

Discussion

Since its launch in May 2015, FoodReach has helped consolidate the food purchasing of over 50 community organizations working to address food insecurity in Toronto by providing healthier meals to the hungry. It has grown steadily, but slowly, often because knowledge of what it offers has not been understood by its target agencies. Since September 2016, when several permanent staff came on board, this has changed and FoodReach's growth trajectory has turned sharply upwards.

The "catch 22" issue of leveraging good wholesale pricing is that it requires volume (in other words, more agencies participating), yet to get the volume it needs good pricing. This is an issue that FoodReach has addressed and in 2016 they brought aboard child care centres en-masse. This has been an important factor in FoodReach's recent growth (see Figures 1 and 2). It is currently in negotiation with the City of Toronto's social procurement division to become a supplier there. This will also bring on a large number of agencies. According to FoodReach, the prospects for growth are good.

During its next phase of development, FoodReach will focus on growing its client base (i.e. community organizations that purchase food through the program), establishing a sustainable funding model, and refining its Buying Portal and Knowledge Exchange portal to further support community organizations.

Few studies have explored the ability of programs like FoodReach to support the needs of vulnerable populations relying on community organizations and student nutrition programs (which are under pressure to reduce costs) to access the food they need. It is also unclear what impact FoodReach, and other programs, have on addressing household food insecurity and poverty. Initiatives like FoodReach fit within Collin's proposed conceptual framework for household food insecurity action as a type of "community food systems model."Footnote 11 These types of municipal initiatives aim to maximize community self-reliance by building partnerships among governments, food champions, and service providers.

Despite growth in recent years, there is in general a lack of systematic evaluation for these initiatives.Footnote 11 More research is needed to understand whether programs like FoodReach increase food security for individuals and communities. Initial qualitative findings from FoodReach suggest that community organizations benefit from the ease, quality, and price of produce offered by the FoodReach program, but longer term evaluative studies are needed to better understand the impact on household food insecurity.

The FoodReach program not only supports community efforts to reduce household food insecurity, but also supports healthy food procurement more broadly. In 2014, a number of Canadian health and scientific organizations identified the need for healthy food procurement policies that encourage consumption of fresh produce, take steps to ensure the affordability of healthier foods, and implement educational components to increase awareness, desire, and demand for healthier options.Footnote 14 Together these enable food systems change. FoodReach is just one way Toronto Public Health is helping community organizations achieve these healthy food procurement objectives.

Conclusion

Toronto Public Health's FoodReach program has helped consolidate the food purchases of over 50 community organizations working to address food insecurity in Toronto by providing meals to the hungry. This program may be an effective way of supporting community action to alleviate food insecurity and promote healthy eating, and research is ongoing to better understand FoodReach, the challenges and opportunities it represents, and its social and health impacts.

Acknowledgements

The Public Health Agency of Canada provided funding for the research on which this article is based.

Conflicts of interest

The authors had no conflicts of interest to report.

Authors' contributions and statement

PC and JG were primary researchers/evaluators/writers; BE was Project Manager, and MG and HO, both from PHAC, provided funding and critical comment.

The content and views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Government of Canada.

References

- Footnote 1

-

Statistics Canada. CANSIM Table 105-0547: Household food insecurity, by age group and sex, Canada, provinces, territories, health regions (2013 boundaries) and peer groups, occasional (number unless otherwise noted) [Internet]. Ottawa (ON): Statistics Canada; 2013 [cited 2016 Oct 24]. Available from: http://www5.statcan.gc.ca/cansim/a26?lang=eng&id=1050547

- Footnote 2

-

Roshanafshar S, Hawkins E. Food insecurity in Canada. Health at a Glance (Statistics Canada). 2015;82-624-X.

- Footnote 3

-

Vozoris NT, Tarasuk VS. Household food insufficiency is associated with poorer health. J Nutr. 2003;133(1):120-126.

- Footnote 4

-

City of Toronto. Toronto Food Strategy. [Internet]. Toronto (ON): City of Toronto; 2016 [Accessed 10/24, 2016.] Available from: http://www1.toronto.ca/wps/portal/contentonly?vgnextoid=75ab044e17e32410VgnVCM10000071d60f89RCRD.

- Footnote 5

-

Tarasuk V, Cheng J, de Oliveira C, Dachner N, Gundersen C, Kurdyak P. Association between household food insecurity and annual health care costs. CMAJ. 2015;187(14):E429-36.

- Footnote 6

-

Melchior M, Chastang J, Falissard B, et al. Food Insecurity and Children's Mental Health: A Prospective Birth Cohort Study. PLoS ONE 2012. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0052615.

- Footnote 7

-

Belsky DW, Moffitt TE, Arseneault L, Melchior M, Caspi A. Context and sequelae of food insecurity in children's development. American Journal of Epidemiology 2010;172(7):809-818. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq201.

- Footnote 8

-

Sriram U, Tarasuk V. Changes in household food insecurity rates in Canadian metropolitan areas from 2007 to 2012. Can J Public Health. 2015;106(5):e322-7.

- Footnote 9

-

Widener MJ, Minaker L, Farber S, et al. How do changes in the daily food and transportation environments affect grocery store accessibility? Journal of Applied Geography. 2017;83:46-62. doi: 10.1016/j.apgeog.2017.03.018.

- Footnote 10

-

Matern R. Who's hungry: a tale of two cities. 2015 profile of hunger in Toronto. Toronto (ON): Daily Bread Food Bank; 2015. Available from: http://www.dailybread.ca/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/2015-WH-FINAL-WEB.pdf

- Footnote 11

-

Collins PA, Power EM, Little MH. Municipal-level responses to household food insecurity in Canada: a call for critical, evaluative research. Can J Public Health. 2014;105(2):e138-41. doi: 10.17269/cjph.105.4224.

- Footnote 12

-

Miller S. Finding food: community food procurement in the city of Toronto. Toronto (ON): Toronto Public Health; 2013. Available from: http://tfpc.to/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2014/02/CFP-Finding-Food.pdf

- Footnote 13

-

Toronto Public Health. Food Reach: Assessment of Food Distribution Portal. Phase 2 (Part 2). Report to the Public Health Agency of Canada. [Internet]. Toronto (ON): Toronto Public Health; 2015. Available upon request.

- Footnote 14

-

Campbell N, Duhaney T, Arango M, et al. Healthy Food Procurement Policy: an important intervention to aid the reduction in chronic noncommunicable diseases. Canadian Journal of Cardiology. 2014;30:1456. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2014.06.021.

Notes

- Footnote 15

-

FoodReach: Phase 3 report to PHAC (March 2017). Available upon request.

- Footnote 16

-

No hard numbers on FoodReach's impact on prices of food, or on the total costs to agencies of food procurement, are available. FoodReach is still investigating this. Initial indications are that FoodReach's prices are competitive but are likely to reduce the overall cost to agencies because of their just-in-time delivery, and the freshness of the produce provided.

- Footnote 17

-

FoodReach sees food prices and food costs as different. Because of very low margins on food prices, FoodReach aims to simply remain competitive. However, its service does provide ways in which overall food costs for agencies can be lowered.

Page details

- Date modified: