Equity reporting: a framework for putting knowledge mobilization and health equity at the core of population health status reporting

Health Promotion and Chronic Disease Prevention in Canada

Lesley Ann Dyck, MA Footnote 1; Susan Snelling, PhD Footnote 2; Val Morrison, MA Footnote 3; Margaret Haworth-Brockman, MSc Footnote 4; Donna Atkinson, MA Footnote 5

https://doi.org/10.24095/hpcdp.38.3.02

This evidence synthesis has been peer reviewed.

Correspondence: National Collaborating Centre for Determinants of Health, St. Francis Xavier University, PO Box 5000, Antigonish, NS B2G 2W5; Tel: 902-867-6133; Email: nccdh@stfx.ca

Abstract

The National Collaborating Centres for Public Health (NCCPH) collaborated on the development of an action framework for integrating equity into population health status reporting. This framework integrates the research literature with on-the-ground experience collected using a unique collaborative learning approach with public health practitioners from across Canada.

This article introduces the Action Framework, describes the learning process, and then situates population health status reporting (PHSR) in the current work of the public health sector. This is followed by a discussion of the nature of evidence related to the social determinants of health as a key aspect of deciding what and how to report. Finally, the connection is made between data and implementation by exploring the concept of actionable information and detailing the Action Framework for equity-integrated population health status reporting. The article concludes with a discussion of the importance of putting knowledge mobilization at the core of the PHSR process and makes suggestions for next steps. The purpose of the article is to encourage practitioners to use, discuss, and ultimately strengthen the framework.

Keywords: population health status reporting, health equity, inequity, social determinants of health, knowledge mobilization

Highlights

- Population health status reporting is a core public health practice, but in Canada it does not tend to explicitly describe health inequities or make recommendations for action to improve health equity.

- This project used a unique collaborative learning circle approach to examine how to better integrate a focus on health equity in population health status reporting processes.

- The result of the project is an action framework that puts knowledge mobilization at the centre to support the implementation of a population health status reporting process that is more likely to result in action to improve health equity.

Introduction

Describing differences in health status between and within populations or groups is central to population health status reporting in Canada.Footnote 1 However, we are particularly interested in differences in health status that can be judged as systematic, unfair and avoidable. These differences in health outcomes are often described as social inequalities, or inequities, and are rooted in unequal power relationships and structures across societies.Footnote 2,Footnote 3 In order to address inequities and improve health equity, we must therefore take collaborative action to improve the social determinants at the root of the health disparity, which include a range of social, political and economic factors.Footnote 4 This is at the heart of an equity-integrated population health status reporting process.

The public health sector has a number of roles in addressing the social determinants of health and improving health equity.Footnote 5 The role we focus on in this article is ‘assess and report’. Reporting purposefully on differences in health status between socio-economic groups, rather than adjusting for the effect of this difference on health status, has been identified as a promising practice for improving health equity.Footnote 6 Purposeful reporting of health inequities leverages both the core public health function of surveillance and the common practice of population health status reporting (PHSR). By assessing and reporting on health inequities, including effective strategies to reduce these inequities, the argument has been made that public health organizations are more likely to take action and be better able to support others to collaborate to decrease health inequities.Footnote 7

We went looking for population health status reports in Canada that demonstrate the effective integration of health equity issues and the social determinants of health and found they were not common. When we did find them, there did not seem to be a consistent or standard approach.Footnote 8,Footnote 9,Footnote 10,Footnote 11 This led us to ask: What does the effective integration of health equity look like in a PHSR process? What do we need to pay attention to in order to do it well? How does such a process contribute to action on the social determinants of health to improve health equity? While exploring these questions we developed the Equity-Integrated Population Health Status Reporting: Action Framework,Footnote 12 an action framework for the PHSR process that we thought might help to guide public health organizations in their work of ‘assessing and reporting’ in a manner that would drive action on the social determinants of health and health inequity.

This article introduces the Action Framework and provides the context for its development. We start by briefly describing our learning process, and then situate PHSR in the work of the public health sector. This is followed by a discussion of the nature of evidence related to the social determinants of health as a key aspect of deciding what and how to report. Finally, we make the connection between data and implementation by exploring the concept of actionable information, and then introduce our Action Framework for equity-integrated PHSR. We conclude with a discussion of the importance of putting knowledge mobilization at the core of the PHSR process and make suggestions for next steps.

Methods: our framework development process

Our learning process was led by the National Collaborating Centre for the Determinants of Health (NCCDH), one of six national collaborating centres for public health established in 2005 to strengthen knowledge translation and exchange for public health in Canada.Footnote 13 A learning circle of health equity champions from across Canada was established by the NCCDH, representing a diversity of perspectives from ten different public health organizations (such as program managers, medical health officers, policy analysts and epidemiologists from health units/regional health authorities, and provincial public health departments) and universities (researchers specifically). They were tasked with identifying and exploring the core issues associated with integrating health equity into population health status reporting, and identifying promising practices in the Canadian context. This resulted in the Learning Together Series,Footnote 14 a collection of documents describing the learning circle process and the key questions explored during each meeting of the circle. This became the foundation for a collaboration with the other five NCCPH centres to develop the Equity-Integrated Population Health Status Reporting: Action Framework.Footnote 12 This Action Framework was developed and refined through interviews with ten key stakeholders at local, provincial and national levels in Canada. Iterations of the Action Framework were also presented and discussed during workshops at three Canadian public health conferencesFootnote a and a webinar.Footnote b Feedback from over 100 public health practitioners attending these events was collected via notes of the proceedings and evaluations, and used to inform the final version of the framework.

Results: production of an equity-integration population health status report

What is a population health status report?

The six core functions of public health in Canada include: population health assessment, health promotion, disease and injury control and prevention, health protection, surveillance, and emergency preparedness and epidemic response.Footnote 15,Footnote 16 All levels of government (federal, provincial, territorial and their delegated authorities including regional health authorities) perform some or all of these functions. All governments appoint a chief public or medical health officer to provide leadership to their public health efforts in their respective jurisdictions,Footnote 15 with the legislation and roles varying somewhat across provinces and territories.

Reporting is not a core function but is an essential tool for fulfilling the public health mandate across the six core functions. In a summary of the structural profile of public health in Canada, the National Collaborating Centre for Healthy Public Policy found that the mandate to report on population health assessment and surveillance (as the key functions most relevant to population health status reporting) varied across jurisdictions. At the federal level “[t]he Chief Public Health Officer shall, within six months after the end of each fiscal year, submit a report to the Minister on the state of public health in Canada.”Footnote 17 An example from the provincial level comes from British Columbia (BC), where the BC Public Health Act stipulates that population health assessment is mainly the responsibility of the Provincial Health Officer (PHO). At the regional level, an example from Manitoba positions population health assessment as a public health function that is partially assumed on the regional level with some of its components instituted by the Regional Health Authorities Act.Footnote 17

Integrating the concept of equity

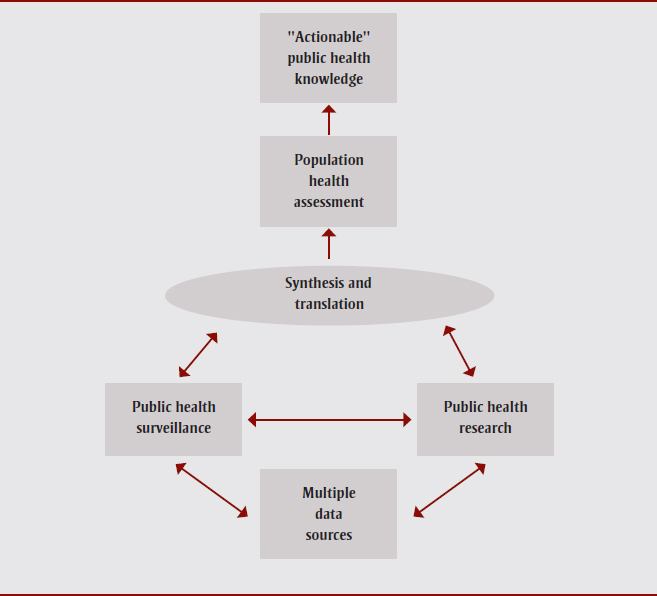

For our project, we used a definition of equity-integrated population health status reports to include “any instrument that uses existing scientific and local knowledge to inform decisions, improve health programs, and reduce health inequities.”Footnote 1,p.2 Population health status reports generally include surveillance and other data, and tend to be used to highlight specific public health issues or topics.Footnote 1 Having said that, one of the challenges of examining health equity in the context of a population health status report is that there is no standardized format, content or process for this report. If we consider PHSR at the broadest level to be a type of population health assessment, we can frame it within the larger context of health knowledge (Figure 1).Footnote 18 Based on this, a population health status report can be understood as a product (e.g., print document, electronic file, or webpage) that provides an assessment of the health of the population and generates actionable public health knowledge. It is based on the same multiple data sources that inform both public health surveillance and public health research (Figure 1).Footnote 18

Source: Lexicon, definitions, and conceptual framework for public health surveillance.Footnote 18,p.13

Figure 1 - Text Description

Figure 1 presents a diagram that looks at public health surveillance in the larger context of health knowledge. If we consider a population health status report at the broadest level to be a type of population health assessment, it can be framed as a product (e.g., print document, electronic file, or webpage) that provides an assessment of the health of the population and generates actionable public health knowledge. It is based on the same multiple data sources that inform both public health surveillance and public health research.

Characterizing the assessment process and its objectives

Information about how to undertake an effective and actionable population health status reporting/assessment process is hindered by the lack of established reporting and process guidelines. Community health assessment is a comprehensive community development approach, which is normally part of a larger community health improvement process.Footnote 19 It is often led by community organizations in partnership with the health sector and is most commonly found in the United States.Footnote 20 Like community health assessment, population health status reporting (PHSR) is both the activity and product of identifying and prioritizing population health issues, and it varies according to the size and nature of the community, the lead organization or partners and their goals, the resources available and other local factors.Footnote 20 However, PHSR as a process in Canada is led by the public health sector and is therefore more likely to be undertaken as a method of generating actionable information for the public health sector, not the wider community. As we shall explain, this presents a particular challenge for reporting on health inequities with the objective of generating action to improve the social determinants of health.

In our review of public health reports across Canada, we found that the intended purpose of any particular report was context/topic specific and could include any or all of: a) a program/service focus around improving accountability and assessing quality/effectiveness; b) a population focus to assess changes in health status over time and across geographic regions; and c) a health disparity focus to identify or quantify health differences between groups.Footnote 21 We concluded that the evidence-based and public nature of population health status reports, while not standardized or necessarily inclusive of equity issues, has helped them become a key building block for the construction and realignment of public health policies and programs.Footnote 1

However, there is a second audience of healthy public policy stakeholders outside of the public health sector (including other government departments, municipalities, and community organizations) that is often targeted by these reports, usually through the inclusion of cross-sectoral intervention examples and recommendations for action.Footnote 21 With respect to action on the social determinants of health, this second “external” audience is critical. Health equity is determined by social factors related to broad public policy, norms and values—most of which are outside the influence of the health sector. Therefore, if the information is only actionable by the public health sector, it will be insufficient to reduce systemic health inequities.

Our learning circle of public health practitioners and researchers came to the conclusion that a successful report is one that is used. What makes the information in the report actionable is the critical consideration for how to best integrate health equity into a population health status report. What we learned from public health practitioners across Canada is that, in order to ensure a report is used, we need to attend to the format and content of a population health status report, as well as how we engage with stakeholders in the community as part of the data gathering and reporting process.

We will more closely examine engagement as a key principle of PHSR, but first we need to apply an equity lens to what is considered valid evidence for a population health status report.

The evidence base for “health inequity” as a public health issue and area for action

The evidence base for health inequity as a public health issue and area for action is growing; helped considerably by the establishment of the World Health Organization (WHO) Commission on Social Determinants of Health (CSDH). One of the CSDH knowledge networks created a guide for constructing the evidence base on the social determinants of health, including six conceptual and theoretical problems.Footnote 22 One of the most important points they make for translating knowledge about health inequities into action is that evidence on its own does not ensure success or provide an imperative for action. It needs refinement and engagement of all the players involved in generating evidence, turning it into policy, and turning policy into action and practice. The guide concludes with a recognition that—although we know a lot about the social factors that affect health—what is known is not universal in its applicability. What is known “… must therefore be read through a lens which deals with its salience, meaning and relevance in particular local contexts.”Footnote 22,p.218 This underscores the importance of engaging those who understand the local context in the process of gathering, analyzing and reporting data on population heath status in order to effectively integrate health equity considerations.

There are a number of population health status reports in Canada that have tackled the conceptual challenges in different ways in order to effectively integrate a health equity lens.Footnote 8,Footnote 9,Footnote 10,Footnote 11,Footnote 23,Footnote 24,Footnote 25,Footnote 26 These reports share the distinction of being explicit about their focus on equity and intention to drive action to improve health equity, and referencing the collaborations and consultations with both organizations and citizens that were necessary to produce the reports. However, these reports do not share a standardized approach, and most are one-time-only reports making it difficult to track change over time and evaluate their collective impact on reducing health inequities. Notable exceptions to the one-time-only reports are the Toronto Unequal City reports from 2010 and 2015,Footnote 11 and the Community Health Assessments from Brandon 2004, 2009, and 2015Footnote 23 and Winnipeg 2004, 2009-10 and 2015.Footnote 26

Part of the challenge of tracking change over time has been the diversity of measures and indicators used to assess and monitor health equity. This challenge has been of particular interest over the past decade or so in Canada, resulting in collaborative equity indicator development processes,Footnote 27,Footnote 28 the development and application of a variety of socio-economic deprivation indicesFootnote 29,Footnote 30,Footnote 31 and an equity indicator trend report.Footnote 32 Epidemiologists continue to discuss the best methods to measure and track health equity and inequity,Footnote 33,Footnote 34,Footnote 35,Footnote 36 but some argue that it is not the quality of the measures that are the issue, but establishing agreement on which indicators to use and encouraging consistent collection and reporting over time.Footnote 37,Footnote 38

There continue to be significant conceptual and methodological issues that create barriers to accessing appropriate and high-quality data. For example, administrative health data do not normally include income, ethnicity, employment and education data that would allow us to disaggregate population data in a manner that would support a health equity assessment. This makes it very difficult to look at differences in health status between populations; particularly change over time for groups who have been traditionally marginalized and oppressed (e.g. people with disabilities, members of the LGBTQ community). We can also see these challenges in the poor quality and lack of Indigenous health information in Canada, the United States, New Zealand and Australia. Only recently have health surveys in Canada and elsewhere made it possible for people to self-identify as Indigenous, allowing analysts to better understand health inequities for Indigenous people living off-reserve and in urban settings. Finally, causal pathways between interventions and impacts on health inequities are not clearly understood,Footnote 22 making it difficult to know how and what data to collect as part of standard program evaluations. All of this has impeded “… the strategic implementation of evidence-based public health interventions aimed at preventing avoidable mortality.”Footnote 39,p.644

In Canada, data associated with First Nation, Inuit and Métis populations are often not available, incomplete, culturally inappropriate, and impacted by fundamental power and control issues, including jurisdictional arguments among different levels of government.Footnote 40,Footnote 41 There have been attempts to overcome these challenges, for example through the work of the First Nations Information Governance Centre (FNIGC). The FNIGC has worked to put communities at the heart of the population health status reporting process by developing the First Nations Regional Health Survey (RHS). This has given communities control over the PHSR process, including decisions about participation, choice of indicators, ownership of data and the information reported.Footnote 42 However, this is only a first step as the First Nations RHS does not include the large number of Indigenous people living in urban settings across Canada or other Indigenous groups (e.g. Métis people).

Engagement and actionable health information

Corburn and Cohen make the case that “drafting, measuring, tracking, and reporting of indicators can be viewed not as a technical process for experts alone, but rather as an opportunity to develop new participatory science policy making, or what we call governance.”Footnote 38,p.2 They refer to governance not just of formal institutions, but also “norms, routines and practices” that help shape issues that get onto the health research and policy agenda, the evidence base that is used, and the social actors who are deemed expert enough to participate in these decisions. As a result, it is the process of developing and using indicators of health equity/inequities that create opportunities for new healthy and equitable governance.Footnote 38 This is reinforced in the WHO Europe report on governance for health equity,Footnote 43 where they recommend equity and health equity as essential markers of a fair and sustainable society, requiring evidence and analysis connected to broad sectoral goals and joint assessment methods across sectors and stakeholders.

For public health institutions, using indicators to shape policy and drive action to improve health equity requires capacity to move beyond traditional indicators and engage with a broad range of stakeholders in non-traditional ways. It is important to recognize that

[t]raditional indicators that measure morbidity and mortality tend to either place responsibility for improving health on the medical or public health communities or on vaguely identified institutions such as the economy, education, or built environment. The result is an overemphasis on medical and public health solutions while failing to articulate the specific institutions and policies that might need to change to promote greater health equity.Footnote 38,p.5

A community-engaged approach to PHSR is critical for integrating health equity in a manner that informs the development and delivery of public health programs and services, but also drives intersectoral action on health inequity. This requires that the public health sector move beyond traditional monitoring and surveillance approaches and not be limited to population health status defined by aggregating individual-level health data. Given that evidence is never free of values, if we do not apply an equity lens to collecting, analyzing and synthesizing evidence, we run the risk of ignoring systemic power and oppression issues potentially embedded in population health status measures.

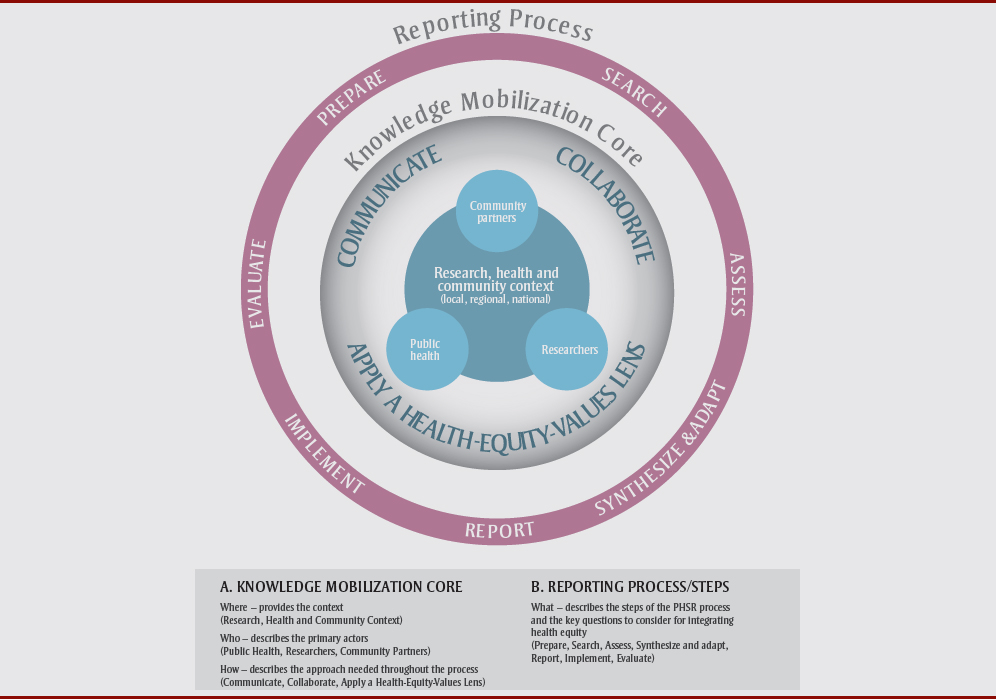

By adopting a community-engaged approach to the ‘assess and report’ role, the public health sector can benefit from the power of PHSR to blend evidence with values—in this case values of equity and fairness. A community-engaged approach to PHSR makes these values explicit in evidence and increases the potential of the evidence to be actionable. The Action Framework identifies three essential components guiding the engagement process for equity-integrated PHSR, including communicate, collaborate, and apply a health-equity values lensFootnote 12 (see the “knowledge mobilization core” in Figure 2).

Source: Summary – Equity-Integrated Population Health Status Reporting: Action Framework.Footnote 49,p.2

Figure 2 - Text Description

This figure depicts the proposed population health status reporting Action Framework.

As part of its knowledge mobilization core, the Action Framework identifies three essential components guiding the engagement process for equity-integrated PHSR, including communicate, collaborate, and apply a health-equity values lens. Although improved equity in population health status is the intended long-term outcome, the framework is unique in that it includes outcomes to ensure “the community is better equipped to take action to address health equity issues” and therefore puts local intersectoral leadership at the very centre. The framework also identifies roles and specific outcomes for each of the three core stakeholder groups as a result of engaging in this process, including public health, community partners, and researchers. The knowledge mobilization core of the framework is the foundation for the essential knowledge synthesis, translation and exchange that happens throughout the PHSR process. It is specific to the intended users of the framework (intersectoral community leadership) and is based on a collaborative approach that integrates health equity throughout. It includes three main elements related to where, who, and how, as follows:

- Where – provides the context (Research, Health and Community Context)

- Who – describes the primary actors (Public Health, Researchers, Community Partners)

- How – describes the approach needed throughout the process (Communicate, Collaborate, Apply a Health-Equity-Values Lens).

- This core is surrounded by population health status reporting steps, summed up by the what:

- What – describes the steps of the PHSR process and the key questions to consider for integrating health equity (Prepare, Search, Assess, Synthesize and adapt, Report, Implement, Evaluate).

Discussion: an action framework for PHSR

In traditional population health status reports, the knowledge to action process emphasizes evidence and concludes with a summary of health status. In reporting processes oriented to action, however, the knowledge mobilization approach combines research knowledge with other types of knowledge and turns them into policy recommendations to drive practice. Although this action-oriented approach to PHSR is less common, there are increasing numbers of examples in Canada.Footnote 9,Footnote 11,Footnote 24

Orientation to action

We are proposing a PHSR framework that is oriented to action, putting equity-informed knowledge mobilization at the core and surrounded by population health status reporting steps, as depicted in Figure 2. Although improved equity in population health status is the intended long-term outcome, the framework is unique in that it includes outcomes to ensure “the community is better equipped to take action to address health equity issues”Footnote 12,p.9 and therefore puts local intersectoral leadership at the very centre. The framework also identifies roles and specific outcomes for each of the three core stakeholder groups as a result of engaging in this process, including public health, community partners, and researchers.

The Action Framework draws from two similar evidence-driven frameworks: the Evidence informed public health model from the National Collaborating Centre for Methods and Tools (NCCMT)Footnote 44 and the Action Cycle developed by the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (RWJF).Footnote 45 A brief summary of our framework is provided here, but a complete description—including promising-practice examples—can be found in the document Equity-Integrated Population Health Status Reporting: Action FrameworkFootnote 12 available from the NCCDH website.

Knowledge mobilization

The knowledge mobilization core of the framework is the foundation for the essential knowledge synthesis, translation and exchange that happens throughout the PHSR process. It is specific to the intended users of the framework (intersectoral community leadership) and is based on a collaborative approach that integrates health equity throughout. It includes three main elements related to where, who, and how (see Box 1). Concrete examples of strong knowledge mobilization for an equity-integrated PHSR approach in Canada and internationally can be found in the Action Framework document.Footnote 12 These include reports that apply an explicit health equity lens, as well as those that provide good examples of collaboration and communication practices around health equity and PHSR.

Box 1. Knowledge mobilization core

Where – a PHSR process can be done at any level: local, regional, or national. At each level there are different people, organizations, political cultures, and available data. Ultimately, however, the community context and local issues inform the reporting process, and are impacted by it as part of the larger system(s). Over time, the community is better equipped to take action to address health equity issues, and the outcome is improvement in health equity within the local community context.

Who – the primary actors in a strong equity-integrated population health status reporting process are the public health sector, community partners, and researchers; a process led by any actor alone is less likely to result in action. The capacity for leadership and action of each is critical to being able to effectively integrate health equity into a PHSR process. The public health sector is essential in implementing PHSR, and public health actors and advocates are well positioned to provide leadership for an effective PHSR process. Community partners (including government, community organizations and other grass-roots leaders) are critical throughout the entire process, and researchers working in a variety of settings and disciplines are important at different points in the process.

How – There is no ‘one size fits all’ approach to mobilizing knowledge in a PHSR process. However, there are principles that are essential to apply throughout the process, which have been captured in the framework as a series of questions that must be considered. These questions can be clustered into three groups: a) Apply a health-equity-values lens, b) Collaborate, and c) Communicate.

Source: Adapted from Summary - Equity-Integrated Population Health Status Reporting: Action Framework.Footnote 49,p.3

Steps for developing and implementing reports

The ’reporting process/steps’ in our framework include seven steps for developing and implementing PHSR. Each step includes key questions to guide activities to ensure the right structures are implemented to support the work of the equity-integrated PHSR process (see Box 2). Just as we did for the knowledge mobilization core of the framework, we identified a number of promising practices in association with one or more of the seven steps of the reporting process. These can also be found in the Action Framework document.Footnote 12

Box 2. Key questions for each of the seven steps of the equity-integrated PHSR process

- Prepare - Who needs to be part of the process? What are the key questions and issues/problems? In what ways are equity values integrated into our investigation questions?

- Search - What is the best way to find the relevant research evidence? What indicators will help us answer the research question? What other data are available? Do we need to develop a plan to collect additional data?

- Assess - What are the data sources and the quality of the data? What limitations are inherent in the sources and data? Is there evidence available from other quantitative, qualitative or participatory research that can be used to complement the data? How do research approaches, data collection and analysis integrate health equity values? Do the various indicators adequately measure both assets and deficits? How well are population demographics disaggregated by geographic, economic and social characteristics?

- Synthesize and adapt - How can we synthesize, adapt and integrate different types of evidence to paint a more complete picture of inequities? What recommendations can we make for practice based on the available evidence? How are health equity values integrated into our recommendations? How do the recommendations relate to the local context?

- Report - Who is our audience and what is the best way to communicate what we have learned?

- Implement - How can we frame the findings so that they engage everyone? What is the best way to explore potential actions, spanning from community mobilization to policy development? How can we collaborate to implement these potential actions?

- Evaluate - How well did the PHSR process contribute to achieving our organizational goals for the report, where improved equity is included and integrated among those goals? In what ways did increased community capacity to take action on the social determinants of health and health equity result from the process?

Source: Adapted from: Equity-Integrated Population Health Status Reporting: Action Framework.Footnote 12,p.35

As a side note, the one step in the process that we were unable to find a promising practice for is the ’evaluate‘ step. One of the challenges around evaluating outcomes such as the impact of policy changes is the long-term nature of the process. As Hilary Graham has pointed out, this has an impact on political commitment to greater health equity, which “… may quickly wane, particularly if the policy changes … prove insufficient to secure a narrowing of inequalities … within the short time periods that governments typically set for their policy goals.”Footnote 46,p.475 Through our consultation process we learned from some informants that they are either evaluating or planning to evaluate their PHSR activities, but we were not able to document concrete examples. As a next step in developing the equity-integrated PHSR framework, it will be important to seek out and learn from any evaluations that have been undertaken.

Conclusion: contribution and further development of the action framework

As our learning circle and other public health informants told us, a report that doesn’t get used won’t help us to improve health equity.Footnote 21 As a result, knowledge mobilization is a central feature of an equity-integrated PHSR framework. We learned that an equity-integrated PHSR process needs to be built around an iterative process that can be applied to fit the context and capacity of stakeholders, and that can draw on promising practices from other disciplines and jurisdictions. In our conversations with a range of public health practitioners, we also learned that to do it well, equity-integrated PHSR must be transparent in how it brings together evidence and social justice values. This makes it more likely that the data will be used to inform other larger processes, including community health assessment and improvement, anti-poverty initiatives and sustainable development work, all of which will contribute to improved health equity.

Although ‘evaluate’ is an important step in the framework, we were not able to find evaluations describing how PHSR contributes to action on the social determinants of health specifically. Collectively, we need to strengthen the evidence base for ‘assess and report’ as a promising public health practice to address health inequities.Footnote 14 We propose two main areas of inquiry and look forward to supporting research-to-practice collaborations in these areas:

- an assessment of current PHSR processes being implemented by public health in Canada, with the objective of evaluating both the processes and outcomes, including policy changeFootnote 47

- the development of clear performance guidelines for PHSR that effectively integrate health equity, as well as organizational and healthy public policy objectives.Footnote 48

Our hope is that this framework will contribute to the improvement and application of population health status reporting to advance health equity in Canada. We look forward to hearing from public health organizations about how they are using their own PHSR processes to improve health equity in their communities.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this project was provided from the operating budget of the National Collaborating Centre for the Determinants of Health, which is funded by the Public Health Agency of Canada. Special thanks to Tannis Cheadle for her assistance in developing and writing the Action Framework document. And thanks as always to the many public health practitioners who participated in the learning circle meetings, workshops and webinars, and reviewed many drafts along the way.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

LAD provided leadership to project and conceptualized and wrote the initial draft of the paper. SS, VM, MHB and DA contributed relevant literature from each NCC program and provided feedback to drafts of the paper. All authors approved the final manuscript.

The content and views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Government of Canada.