Original quantitative research – Age at first alcohol use predicts current alcohol use, binge drinking and mixing of alcohol with energy drinks among Ontario Grade 12 students in the COMPASS study

Health Promotion and Chronic Disease Prevention in Canada

Simone D. Holligan, PhDAuthor reference 1Author reference 2; Katelyn Battista, PhDAuthor reference 2; Margaret de Groh, PhDAuthor reference 1; Ying Jiang, MDAuthor reference 1; Scott T. Leatherdale, PhDAuthor reference 2

https://doi.org/10.24095/hpcdp.39.11.02

This article has been peer reviewed.

Author references:

- Author reference 1

-

Public Health Agency of Canada, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada

- Author reference 2

-

School of Public Health and Health Systems, University of Waterloo, Waterloo, Ontario, Canada

Correspondence: Simone D. Holligan, 200 University Avenue West, Waterloo, ON N2L 3G1; Tel:519-888-4567; Email: sholligan@uwaterloo.ca

Abstract

Introduction: This study investigates the influence of age at first use of alcohol on current alcohol use and associated behaviours in a large sample of Canadian youth.

Methods: This descriptive-analytical study was conducted among Ontario Grade 12 students enrolled in the COMPASS Host Study between 2012 and 2017. We used generalized estimating equations (GEE) modelling to determine associations between age at first alcohol use and likelihood of current versus non-current alcohol use, binge drinking and mixing of alcohol with energy drinks among respondents.

Results: Students reporting an age at first alcohol use between ages 13 and 14 years were more likely to report current alcohol use versus non-current use (OR = 2.80, 95% CI: 2.26–3.45) and current binge drinking versus non-current binge drinking (OR = 3.22, 95% CI: 2.45–4.25) compared to students reporting first alcohol use at age 18 years or older. Students who started drinking at 8 years of age or younger were more likely to report current versus non-current alcohol use (OR = 3.54, 95% CI: 2.83–4.43), binge drinking (OR = 3.99, 95% CI: 2.97–5.37), and mixing of alcohol with energy drinks (OR = 2.26, 95% CI: 1.23–4.14), compared to students who started drinking at 18 years or older.

Conclusion: Starting to drink alcohol in the early teen years predicted current alcohol use, current binge drinking and mixing of alcohol with energy drinks when students were in Grade 12. Findings indicate a need for development of novel alcohol prevention efforts.

Keywords: youth, alcohol, initiation, first drink, binge drinking, public health

Highlights

- Prevalence of current alcohol use among Grade 12 students ranged between 45% and 53% across the six-year study period.

- Students who started drinking between the ages of 13 and 14 years were nearly 3 times more likely to drink alcohol and over 3 times more likely to binge drink in Grade 12 compared to those who started drinking at age 18 years or older.

- Students who started drinking at age 8 years or younger were nearly 3.5 times more likely to drink alcohol and 4 times more likely to binge drink in Grade 12 compared to those who started drinking at 18 years of age or older.

Introduction

Alcohol use in adolescents negatively affects their mental and physical development;Footnote 1 peer and parental alcohol use are key influences on such behaviour.Footnote 2 For these reasons, the minimum legal drinking age has been set at 18 years for Alberta, Quebec and Manitoba, and at 19 years for all other Canadian provinces and territories. Psychosocial factors including pubertal changes, emotional vulnerability and sensation-seeking behaviour have been shown to promote alcohol use in adolescents who are transitioning to high school.Footnote 2Footnote 3 Using data from the Mental Health Supplement of the Ontario Health Survey, DeWit and colleaguesFootnote 4 demonstrated associations between early age at first use of alcohol and development of lifetime alcohol abuse and dependence at 10 years since first use of alcohol. Survival analyses showed that respondents who had their first drink of alcohol between ages 13 and 14 were five times more likely to develop alcohol abuse than those who started to drink at 19 years or older.Footnote 4 Respondents who reported first drinking between ages 11 and 12 were over nine times more likely to develop alcohol dependence than those who started to drink at 19 years or older.Footnote 4

Binge drinking, or the consumption of five or more alcoholic drinks on one occasion,Footnote 5 has been associated with lower academic performance and other risk behaviours including smoking and the use of illicit drugs.Footnote 6 Data from the Canadian Community Health Survey showed that, of youth aged between 12 and 17 years, 4.2% (n = 94 300) reported engaging in heavy drinking in 2017, and 3.4% (n = 77 100) reported engaging in heavy drinking in 2018.Footnote 7 Data from the Youth Risk Behaviour Survey further suggested that while binge drinking rates were similar among girls and boys, rates rose with increasing age and grade level.Footnote 6 Binge drinking during adolescence has also been predictive of binge drinking into early adulthood. Data from the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth indicated that binge drinking between 17 and 20 years of age increased the relative risk of binge drinking between 30 and 31 years of age by over twofold for males and over threefold for females.Footnote 8 Mixing of alcohol with energy drinks has also been associated with increased alcohol intake per drinking occasion,Footnote 9 and is deemed a strong indicator of risk-taking behaviour among youth.Footnote 10 Additional studies have shown associations between early adolescent alcohol use and alcohol-related injuries,Footnote 11 as well as increased likelihood of alcohol dependence later in life.Footnote 12

Other indicators of health status also compound early initiation of alcohol use in youth. Findings from the first cycle of the COMPASS Host Study showed that students who smoked were 61% more likely to use alcohol and had a twofold increased likelihood of binge drinking, while students who used marijuana had a tenfold increased likelihood of using alcohol and a twelvefold increased likelihood of binge drinking.Footnote 13 Students who were physically active according to Health Canada guidelines were also 29% more likely to use alcohol and 35% more likely to engage in binge drinking, suggesting a strong influence of schools' sporting culture on alcohol use behaviours among youth.Footnote 13 There was no difference in likelihood of current alcohol use or current binge drinking between males and females.Footnote 13 From a resilience perspective, resources that protect against youth binge drinking can be grouped into factors that include the strength of personal relationshipsFootnote 14 and school structure.Footnote 15

The goal of the current study was to gain knowledge about youth who use alcohol, specifically on predictors of their alcohol use and related behaviours within the current policy environment. To our knowledge, this paper is the first to investigate whether age at first alcohol use predicts current alcohol use, binge drinking or mixing of alcohol with energy drinks among a large sample of Canadian youth.

Methods

Study description

The COMPASS Host Study is a prospective cohort study (2012 to 2021) designed to collect data from a convenience sample of Canadian secondary schools and the students between Grades 9 and 12 who attend these schools. Annual student-level assessments are made on rates of alcohol use, marijuana and tobacco use, obesity, school connectedness, bullying, academic achievement and mental health via the COMPASS Student Questionnaire, described elsewhere.Footnote 16 Comprehensive details on the COMPASS Host Study, including sampling, data collection and linkage process, are available online. Ethics approval for this study was obtained from the University of Waterloo's Office of Research Ethics (ORE # 17264) and respective school boards.

Sample

In our investigation, we used data from Ontario Grade 12 students in year 1 (2012) through year 6 (2017) of the COMPASS Host Study. The inclusion criteria comprised all English-speaking school boards that had secondary schools with Grades 9 through 12 and a student population of at least 100 students or greater per grade level; had schools that operated in a standard school/classroom setting; and permitted the use of active-information passive-consent parental permission protocols.Footnote 16 We approached all school boards meeting the inclusion criteria.

There were 5699 participating Grade 12 students (from 43 schools) in year 1; 9370 (from 79 schools) in year 2; 8322 (from 78 schools) in year 3; 8046 (from 72 schools) in year 4; 7146 (from 68 schools) in year 5; and 6505 (from 61 schools) in year 6. Study participation rates in each year ranged from 78% to 82%, with the primary reasons for non-response being absenteeism or scheduled spare at the time of survey. Students with missing data on any of the study variables were removed, resulting in a final sample of 4813 Grade 12 students in year 1; 7749 in year 2; 6736 in year 3; 6470 in year 4; 5685 in year 5; and 5389 in year 6.

Measures

Demographics, alcohol use behaviours and risk factors were queried via the COMPASS Student Questionnaire. To assess sex, students were asked, "Are you female or male?" To assess ethnicity, students were asked, "How would you describe yourself?" Responses were grouped as: White for "White"; and non-White for "Black" or "Asian" or "Off-Reserve Aboriginal" or "Latin American/Hispanic" or "Mixed/Other." To assess levels of school connectedness, we used a six-item derived measure. These items assessed students' agreement with the following statements, as previously reported:Footnote 15 "I feel close to people at my school"; "I feel I am part of my school"; "I am happy to be at my school"; "I feel the teachers at my school treat me fairly"; "I feel safe in my school"; and "Getting good grades is important to me." Scores range between 6 and 24, with higher scores indicating higher levels of school connectedness. Cronbach's α for this measure was 0.83.

To assess age at first alcohol use, students were asked, "How old were you when you first had a drink of alcohol that was more than a sip?" Responses were grouped as: age 8 years or younger; 9–10 years; 11–12 years; 13–14 years; 15–16 years; 17 years; and 18 years or older. To assess alcohol use, students were asked, "In the last 12 months, how often did you have a drink of alcohol that was more than just a sip?" Responses were grouped in three categories: Current for "Once a month" or "2 or 3 times a month" or "Once a week" or "2 to 3 times a week" or "4 to 6 times a week" or "Every day"; Non-current for "I did not drink alcohol in the last 12 months" or "I have only had a sip of alcohol" or "Less than once a month"; and Never for "I have never drunk alcohol." To assess binge drinking behaviour, students were asked, "In the last 12 months, how often did you have 5 drinks of alcohol or more on one occasion?" Responses were grouped as: Current for "Once a month" or "2 to 3 times a month" or "Once a week" or "2 to 5 times a week" or "Daily or almost daily"; Non-current for "I did not have 5 or more drinks on one occasion in the last 12 months" or "Less than once a month"; and Never for "I have never done this." To assess mixing of alcohol with energy drinks, students were asked, "In the last 12 months, have you had alcohol mixed or pre-mixed with an energy drink (such as Red Bull, Rock Star, Monster or another brand)?" Responses were grouped as: Current for "Yes"; Non-current for "I did not do this in the last 12 months"; and Never for "I have never done this."

To assess smoking status, students were asked, "On how many of the last 30 days did you smoke one or more cigarettes?" Responses ranged from "None" to "30 days (every day)" and were grouped in two categories:Current smoker for responses ranging from 1 to 30 days; and Non-smoker for a response of 0 days. To assess marijuana use, students were asked, "In the last 12 months, how often did you use marijuana or cannabis?" Responses were grouped in three categories: Current for "Once a month" or "2 or 3 times a month" or "Once a week" or "2 to 3 times a week" or "4 to 6 times a week" or "Every day"; Non-current for "I have used marijuana but not in the last 12 months" or "Less than once a month"; and Never for "I have never used marijuana." To assess levels of physical activity, students were queried on how many minutes of hard and moderate physical activity they did on each of the last seven days. Following the Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology 24-hour movement guidelines, students who completed at least 60 minutes of moderate and/or hard physical activity on each day in the past seven days were classified as Meeting physical activity guidelines, while students who completed less than 60 minutes of activity in the past seven days were classified as Not meeting physical activity guidelines.

Statistical analyses

We used descriptive statistics to show the distribution of the study variables. Marginal logistic regression using generalized estimating equations (GEE) models were then used to examine whether age at first alcohol use influences current versus non-current alcohol use, binge drinking and mixing of alcohol with energy drinks in the last 12 months among students who drink. Full models were fitted for each outcome. All models controlled for sex (male/female), ethnicity (White or non-White), school connectedness, year of data collection, smoking status, marijuana use and physical activity level, and accounted for within-school clustering.

We fitted GEE models using the SAS PROC GEE procedure with a binomial distribution and a logit function. All models used an exchangeable working correlation structure based on the results of initial analyses. We used empirical standard error estimates to calculate confidence intervals and test statistics. Analyses were conducted using the statistical software package SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Demographics

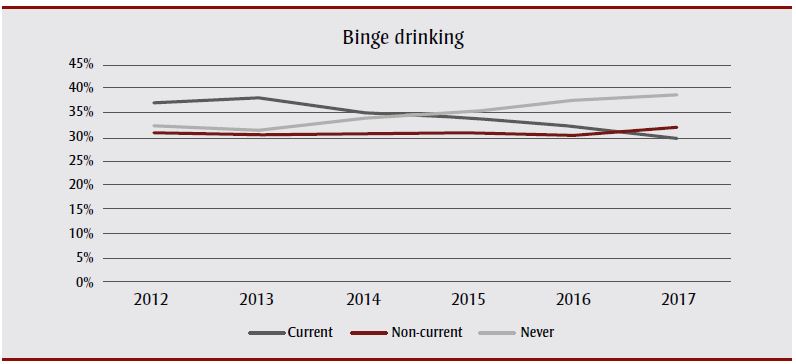

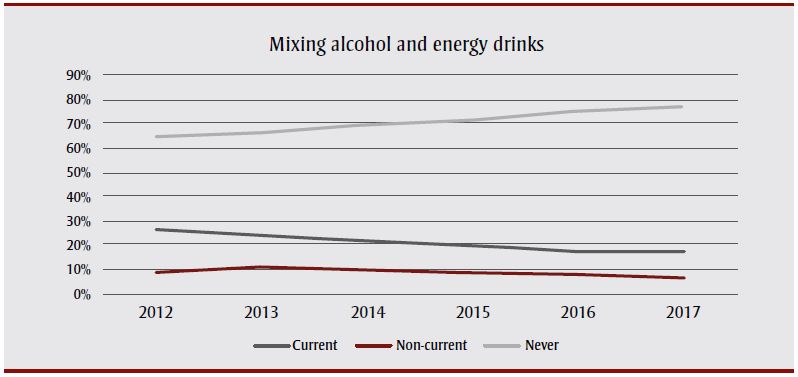

As shown in Table 1, the most frequently reported age at first alcohol use was between ages 15 and 16 years; proportions ranged between 31.0% and 34.0% across years. An average of 24.5% of Grade 12 students reported an age at first alcohol use between 13 and 14 years of age, while an average of 4.5% reported an age at first use of 8 years of age or younger across years. Among Grade 12 students, prevalence of current alcohol use ranged between 45.0% and 53.0% across years (Figure 1). Prevalence of current alcohol use increased modestly in 2013 (p = .003), and steadily declined between 2013 and 2017 (p < .001). As shown in Table 2 and Figure 2, prevalence of current binge drinking ranged between 29.0% and 38.0% across years, with steady declines from 2013 to 2017 (p < .05). Prevalence of mixing alcohol with energy drinks was highest in 2012 at 26.0%, and steadily declined across years to 17.0% in 2017 (p < .001), as shown in Table 2 and Figure 3. Students reported school connectedness scores between 18.0 ± 3.5 and 18.3 ± 3.5 across years (Table 1).

| Characteristics | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 4813 | N = 7749 | N = 6736 | N = 6470 | N = 5685 | N = 5389 | ||||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | ||

| Sex | Girls | 2430 | 50 | 3916 | 51 | 3477 | 52 | 3251 | 50 | 2938 | 52 | 2727 | 51 |

| Boys | 2383 | 50 | 3833 | 49 | 3259 | 48 | 3219 | 50 | 2747 | 48 | 2662 | 49 | |

| Ethnicity | White | 3844 | 80 | 6237 | 80 | 5392 | 80 | 5021 | 78 | 4437 | 78 | 4085 | 76 |

| Non-WhiteTable 1 Footnote a | 969 | 20 | 1512 | 20 | 1344 | 20 | 1449 | 22 | 1248 | 22 | 1304 | 24 | |

| Age at first use of alcohol | ≤ 8 years | 217 | 5 | 329 | 4 | 324 | 5 | 300 | 5 | 238 | 4 | 222 | 4 |

| 9–10 years | 107 | 2 | 235 | 3 | 152 | 2 | 173 | 3 | 140 | 2 | 121 | 2 | |

| 11–12 years | 307 | 6 | 451 | 6 | 371 | 6 | 357 | 6 | 335 | 6 | 249 | 5 | |

| 13–14 years | 1252 | 26 | 1978 | 26 | 1664 | 25 | 1535 | 24 | 1319 | 23 | 1251 | 23 | |

| 15–16 years | 1545 | 32 | 2639 | 34 | 2217 | 33 | 2059 | 32 | 1747 | 31 | 1754 | 33 | |

| 17 years | 218 | 5 | 367 | 5 | 329 | 5 | 327 | 5 | 290 | 5 | 269 | 5 | |

| ≥ 18 years | 47 | 1 | 55 | 1 | 48 | 1 | 67 | 1 | 61 | 1 | 59 | 1 | |

| Only a sip/never | 1120 | 23 | 1695 | 22 | 1631 | 24 | 1652 | 26 | 1555 | 27 | 1464 | 27 | |

| Alcohol use in past 12 months | Current | 2455 | 51 | 4102 | 53 | 3323 | 49 | 3155 | 49 | 2669 | 47 | 2449 | 45 |

| Non-current | 1803 | 37 | 2676 | 35 | 2422 | 36 | 2247 | 35 | 2019 | 36 | 2007 | 37 | |

| Never | 555 | 12 | 971 | 13 | 991 | 15 | 1068 | 17 | 997 | 18 | 933 | 17 | |

| Binge drinking in past 12 months | Current | 1783 | 37 | 2940 | 38 | 2359 | 35 | 2189 | 34 | 1830 | 32 | 1584 | 29 |

| Non-current | 1488 | 31 | 2372 | 31 | 2087 | 31 | 2005 | 31 | 1715 | 30 | 1720 | 32 | |

| Never | 1542 | 32 | 2437 | 31 | 2290 | 34 | 2276 | 35 | 2140 | 38 | 2085 | 39 | |

| Mixing alcohol with energy drinks in past 12 months | Current | 1270 | 26 | 1817 | 23 | 1437 | 21 | 1290 | 20 | 971 | 17 | 907 | 17 |

| Non-current | 446 | 9 | 814 | 11 | 634 | 9 | 556 | 9 | 451 | 8 | 358 | 7 | |

| Never | 3097 | 64 | 5118 | 66 | 4665 | 69 | 4624 | 71 | 4263 | 75 | 4130 | 77 | |

| Smoking status | Current | 695 | 14 | 1188 | 15 | 1002 | 15 | 1059 | 16 | 885 | 16 | 759 | 14 |

| Non-smoker | 4118 | 86 | 6561 | 85 | 5734 | 85 | 5411 | 84 | 4800 | 84 | 4630 | 86 | |

| Marijuana use | Current | 1084 | 23 | 1772 | 23 | 1557 | 23 | 1488 | 23 | 1308 | 23 | 1307 | 24 |

| Non-current | 1162 | 24 | 1850 | 24 | 1541 | 23 | 1480 | 23 | 1256 | 22 | 1262 | 23 | |

| Never | 2567 | 53 | 4127 | 53 | 3638 | 54 | 3502 | 54 | 3121 | 55 | 2820 | 52 | |

| Meeting physical activity guidelines | Yes | 2142 | 45 | 3458 | 45 | 3039 | 45 | 2992 | 46 | 2601 | 46 | 2193 | 41 |

| No | 2671 | 55 | 4291 | 55 | 3697 | 55 | 3478 | 54 | 3084 | 54 | 3196 | 59 | |

| School connectednessTable 1 Footnote b | Mean (SD) | 18.3 (3.2) | 18.2 (3.3) | 18.2 (3.5) | 18.3 (3.5) | 18.0 (3.5) | 18.0 (3.6) | ||||||

|

|||||||||||||

Figure 1. Prevalence of alcohol use among Ontario Grade 12 students in the COMPASS Host Study, 2012–2017

Text description

| Alcohol use in past 12 months | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Current | 51% | 53% | 49% | 49% | 47% | 45% |

| Non-current | 37% | 35% | 36% | 35% | 36% | 37% |

| Never | 12% | 13% | 15% | 17% | 18% | 17% |

| Characteristics | 2012 (%) |

2013 (%) |

p- valueTable 2 Footnote a | 2014 (%) |

p- valueTable 2 Footnote a | 2015 (%) |

p- valueTable 2 Footnote a | 2016 (%) |

p- valueTable 2 Footnote a | 2017 (%) |

p -valueTable 2 Footnote a | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohol use in past 12 months | Current | 51 | 53 | .003 | 49 | < .001 | 49 | < .001 | 47 | < .001 | 45 | < .001 |

| Non-current | 37 | 35 | 36 | 35 | 36 | 37 | ||||||

| Never | 12 | 13 | 15 | 17 | 18 | 17 | ||||||

| Binge drinking in past 12 months | Current | 37 | 38 | .592 | 35 | .040 | 34 | < .001 | 32 | < .001 | 29 | < .001 |

| Non-current | 31 | 31 | 31 | 31 | 30 | 32 | ||||||

| Never | 32 | 31 | 34 | 35 | 38 | 39 | ||||||

| Mixing alcohol with energy drinks in past 12 months | Current | 26 | 23 | < .001 | 21 | < .001 | 20 | < .001 | 17 | < .001 | 17 | < .001 |

| Non-current | 9 | 11 | 9 | 9 | 8 | 7 | ||||||

| Never | 64 | 66 | 69 | 71 | 75 | 77 | ||||||

|

||||||||||||

Figure 2. Prevalence of binge drinking among Ontario Grade 12 students in the COMPASS Host Study, 2012–2017

Text description

| Binge drinking in past 12 months | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Current | 37% | 38% | 35% | 34% | 32% | 29% |

| Non-current | 31% | 31% | 31% | 31% | 30% | 32% |

| Never | 32% | 31% | 34% | 35% | 38% | 39% |

Figure 3. Prevalence of mixing of alcohol with energy drinks among Ontario Grade 12 students in the COMPASS Host Study, 2012–2017

Text description

| Mixing alcohol with energy drinks in past 12 months | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Current | 26% | 23% | 21% | 20% | 17% | 17% |

| Non-current | 9% | 11% | 9% | 9% | 8% | 7% |

| Never | 64% | 66% | 69% | 71% | 75% | 77% |

Alcohol use

Compared to students reporting an age at first alcohol use of 18 years or older, students reporting an age at first alcohol use between 13 years and 14 years (odds ratio [OR] 2.80, 95% CI: 2.26–3.45), 11 years and 12 years (OR 2.86, 95% CI: 2.29–3.56), and 8 years or less (OR 3.54, 95% CI: 2.83–4.43) had an increased likelihood of current versus non-current alcohol use (Table 3). For every 1-unit increase in school connectedness, there was an associated 5% increase in likelihood of current alcohol use versus non-current alcohol use (OR 1.05, 95% CI: 1.04–1.06). Boys were more likely to report current versus non-current alcohol use over girls (OR 1.20, 95% CI: 1.12–1.28).

| Characteristics | Current vs. non-currentTable 3 Footnote a alcohol use (n = 27 725) |

Current vs. non-currentTable 3 Footnote a binge drinking (n = 24 072) |

Current vs. non-currentTable 3 Footnote a mixing of alcohol with energy drinks (n = 10 506) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |||||

| Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | |||||

| Sex | Girls | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Boys | 1.20 | 1.12 | 1.28 | 1.32 | 1.24 | 1.40 | 1.25 | 1.13 | 1.39 | |

| Ethnicity | White | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Non-White | 0.81 | 0.75 | 0.88 | 0.94 | 0.84 | 1.05 | 1.15 | 1.02 | 1.29 | |

| Year of collection | 2012 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| 2013 | 1.04 | 0.91 | 1.17 | 0.99 | 0.87 | 1.14 | 0.74 | 0.63 | 0.87 | |

| 2014 | 0.89 | 0.80 | 0.99 | 0.87 | 0.77 | 0.99 | 0.74 | 0.63 | 0.87 | |

| 2015 | 0.90 | 0.80 | 1.00 | 0.82 | 0.71 | 0.94 | 0.72 | 0.61 | 0.85 | |

| 2016 | 0.89 | 0.79 | 0.99 | 0.81 | 0.71 | 0.93 | 0.68 | 0.58 | 0.80 | |

| 2017 | 0.80 | 0.69 | 0.93 | 0.68 | 0.60 | 0.78 | 0.80 | 0.66 | 0.96 | |

| Age at first use of alcohol | ≥ 18 years | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| ≤ 8 years | 3.54 | 2.83 | 4.43 | 3.99 | 2.97 | 5.37 | 2.26 | 1.23 | 4.14 | |

| 9–10 years | 2.81 | 2.15 | 3.67 | 3.36 | 2.49 | 4.54 | 1.39 | 0.75 | 2.59 | |

| 11–12 years | 2.86 | 2.29 | 3.56 | 2.96 | 2.27 | 3.87 | 1.73 | 0.97 | 3.10 | |

| 13–14 years | 2.80 | 2.26 | 3.45 | 3.22 | 2.45 | 4.25 | 1.51 | 0.85 | 2.68 | |

| 15–16 years | 1.69 | 1.39 | 2.06 | 1.97 | 1.51 | 2.55 | 1.43 | 0.80 | 2.53 | |

| 17 years | 0.73 | 0.60 | 0.90 | 0.93 | 0.69 | 1.27 | 1.48 | 0.81 | 2.69 | |

| Smoking status | Non-smoker | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Current | 2.15 | 1.93 | 2.39 | 2.37 | 2.15 | 2.60 | 1.57 | 1.41 | 1.76 | |

| Marijuana use | Never | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Non-current | 1.90 | 1.76 | 2.05 | 2.01 | 1.89 | 2.14 | 1.13 | 1.01 | 1.27 | |

| Current | 3.83 | 3.49 | 4.21 | 4.12 | 3.80 | 4.48 | 1.54 | 1.37 | 1.73 | |

| Meeting physical activity guidelines | No | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Yes | 1.31 | 1.24 | 1.39 | 1.38 | 1.30 | 1.46 | 1.06 | 0.96 | 1.16 | |

| School connectednessTable 3 Footnote b | 1.05 | 1.04 | 1.06 | 1.03 | 1.02 | 1.04 | 0.99 | 0.98 | 1.00 | |

Abbreviations: GEE, generalized estimating equation; OR, odds ratio. Note: Reference categories are "Girls," "White," "2012," "≥ 18 years of age," "Non-smoker," "Never" and "No."

|

||||||||||

Binge drinking

As shown in Table 3, compared to students with an age at first alcohol use of 18 years or older, students reporting an age at first alcohol use of 16 years or younger were more likely to report current binge drinking over non-current binge drinking (ages 15 to 16 years, OR = 1.97, 95% CI: 1.51–2.55; ages 13 to 14 years, OR = 3.22, 95% CI: 2.45–4.25; ages 11 to 12 years, OR = 2.96, 95% CI: 2.27–3.87; ages 9 to 10 years, OR = 3.36, 95% CI: 2.49–4.54; ages 8 years or younger, OR = 3.99, 95% CI: 2.97–5.37). Boys were more likely to report current binge drinking over non-current binge drinking compared to girls (OR = 1.32, 95% CI: 1.24–1.40). For every 1-unit increase in school connectedness, there was a 3% increase in likelihood of current over non-current binge drinking (OR = 1.03, 95% CI: 1.02–1.04). Students were less likely to report current versus non-current binge drinking between 2015 and 2017, compared to the baseline year of 2012 (2015, OR = 0.82, 95% CI: 0.71–0.94; 2016, OR = 0.81, 95% CI: 0.71–0.93; 2017, OR = 0.68, 95% CI: 0.60-0.78).

Mixing alcohol with energy drinks

Compared to students reporting an age at first alcohol use of 18 years or older, students reporting an age at first alcohol use of 8 years or younger had a twofold increase in the likelihood of current versus non-current mixing of alcohol with energy drinks (OR = 2.26, 95% CI: 1.23–4.14); see Table 3. Boys were more likely to report current versus non-current mixing of alcohol with energy drinks over girls (OR = 1.25, 95% CI: 1.13–1.39). Non-White students were more likely to report current versus non-current mixing of alcohol with energy drinks compared to White students (OR = 1.15, 95% CI: 1.02–1.29). School connectedness did not influence likelihood of current versus non-current mixing of alcohol with energy drinks. Students were less likely to report current versus non-current mixing of alcohol with energy drinks between 2013 and 2017, compared to the baseline year of 2012 (2013, OR = 0.74, 95% CI: 0.63–0.87; 2014, OR = 0.74, 95% CI: 0.63–0.87; 2015, OR = 0.72, 95% CI: 0.61–0.85; 2016, OR = 0.68, 95% CI: 0.58–0.80; 2017, OR = 0.80, 95% CI: 0.66–0.96); see Table 3.

Other indicators of risk

Students who reported current smoking had an increased likelihood of current versus non-current alcohol use (OR = 2.15, 95% CI: 1.93–2.39), current versus non-current binge drinking (OR = 2.37, 95% CI: 2.15–2.60), and current versus non-current mixing of alcohol with energy drinks (OR = 1.57, 95% CI: 1.41–1.76), compared to non-smoking students. Current marijuana users had an increased likelihood of current versus non-current alcohol use (OR = 3.83, 95% CI: 3.49–4.21), current versus non-current binge drinking (OR = 4.12, 95% CI: 3.80–4.48), and current versus non-current mixing of alcohol with energy drinks (OR = 1.54, 95% CI: 1.37–1.73), compared to students who never used marijuana. Physically active students had an increased likelihood of current versus non-current alcohol use (OR = 1.31, 95% CI: 1.24–1.39), and current versus non-current binge drinking (OR = 1.38, 95% CI: 1.30–1.46), compared to relatively inactive students.

Discussion

Our study shows associations between age at first alcohol use and current alcohol use and related behaviours among a large sample of Ontario Grade 12 students. Students who reported first drinking alcohol between ages 13 and 14 years were nearly 3 times more likely to engage in drinking alcohol, and over 3 times more likely to binge drink, compared to those who reported first drinking at age 18 or older. Students who reported first drinking alcohol at age 8 years or younger were 3.5 times more likely to engage in drinking alcohol, nearly 4 times more likely to binge drink, and over 2 times more likely to engage in mixing alcohol with energy drinks than those who reported first drinking at age 18 or older. As evidenced elsewhere,Footnote 4 the younger students were at the time of their first use of alcohol, the more likely they were to display current alcohol use and maladaptive patterns of use upon transition to adulthood. While Miller and colleaguesFootnote 6 showed similar rates of binge drinking among boys and girls in high school, results from the present study showed that boys in Grade 12 were more likely to engage in binge drinking and mixing of alcohol with energy drinks than girls. As indicated in previous work,Footnote 13 students who smoked, used marijuana and were physically active were more likely to use alcohol, display binge drinking, and engage in mixing alcohol with energy drinks. Moreover, increasing levels of school connectedness among these Grade 12 students were found to increase likelihood of drinking alcohol and binge drinking, indicating the potential influence of peer drinking networks within the school environment.Footnote 2 Our study also showed that physically active Grade 12 students and Grade 12 students with higher levels of school connectedness were more likely to use alcohol and binge drink. While resilience frameworks have shown associations between measures of school connectedness and alcohol use behaviours among youth,Footnote 6Footnote 17Footnote 18 we hypothesize that such associations may show a nonlinear, U-shaped relationship. Consistently high school connectedness may be indicative of other factors, such as involvement in school sports,Footnote 19 which has been linked to increased likelihood of alcohol use.Footnote 13Footnote 15

Prevalence of current alcohol consumption was relatively high among the sample of Grade 12 students, with rates above 45% across years. Prevalence of current binge drinking among these students was also relatively high, with rates fluctuating between 29% and 38% across years. Modest declines in rates of binge drinking from 2012 through 2017 may be attributed to relative increases in students who reported never binge drinking, as the proportion of students reporting non-current binge drinking remained stable. While not evaluative, declines in binge drinking rates have paralleled emphasis on municipal alcohol policies by Public Health Ontario,Footnote 20 along with a focus on alcohol-related injuries by the Alcohol Locally Driven Collaborative Project (LDCP) Team.Footnote 21

Mixing of alcohol with energy drinks has been considered a marker for risk-taking behaviour,Footnote 10 with a meta-analysis showing that consumers who combined alcohol with energy drinks over alcohol alone tended to consume more alcohol per drinking occasion.Footnote 9 Health Canada regulations for food and natural products manufacturers stipulates labelling of energy drinks with text including "not recommended for children" and "do not mix with alcohol." The deadline for compliance with this labelling regulation was December 2013. Prevalence of mixing alcohol with energy drinks among Grade 12 students was below 30% in 2012 and steadily declined thereafter. Natural experiments would show whether the decline could have resulted from this policy; regardless, a near 10% decrease in prevalence across six years shows promise for future cross-sectoral strategies for prevention and cessation programming.Footnote 22

Strengths and limitations

Our study utilized a large sample of Grade 12 students from a convenience sample of schools in the province of Ontario. COMPASS is a prospective cohort study (2012 to 2021) collecting data from a convenience sample of secondary schools and the students between Grades 9 and 12 who attend these schools. COMPASS utilizes purposive sampling for recruitment of participating schools from different geographical regions.Footnote 16 While this approach may impact external validity, data are comparable with other large-scale surveys on alcohol use and binge drinking prevalence among Canadian youth—namely, the Canadian Community Health Survey (2009/2010) and the Canadian Alcohol and Drug Monitoring SurveyFootnote 23 and the Canadian Student Tobacco, Alcohol and Drugs Survey.Footnote 24 Data from the COMPASS Host Study's student questionnaire are self-reported, and though bias may have been introduced through self-report, this method provides an emic representation of students' health behaviours. The data collection procedures further limit social desirability bias by using an active-information, passive-consent permission approach, which has been found to maintain confidentiality and minimize underreporting.Footnote 25 While the repeat cross-sectional design of our study also accounts for changes in the sample over time, interpretation of findings may only be relevant to a substantive proportion of Grade 12 students.

Conclusion

There is a high prevalence of alcohol use among Grade 12 students in Ontario, with relative stability across a six-year time period. Binge drinking rates peaked and modestly declined across years, while mixing of alcohol with energy drinks generally decreased across years. An age at first alcohol use of 14 years or younger predicted current alcohol use among Grade 12 students. An age at first alcohol use of 16 years or younger predicted current binge drinking, while an age at first use of 12 years or younger predicted mixing of alcohol with energy drinks among Grade 12 students. Findings indicate a need for novel approaches for alcohol prevention and cessation programming for youth.

Acknowledgements

The COMPASS Host Study is supported by a bridge grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) Institute of Nutrition, Metabolism and Diabetes (INMD) through the "Obesity – Interventions to Prevent or Treat" priority funding awards (OOP-110788; grant awarded to S. Leatherdale) and an operating grant from the CIHR Institute of Population and Public Health (IPPH) (MOP-114875; grant awarded to S. Leatherdale). Dr. Leatherdale is a Chair in Applied Public Health Research funded by the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) in partnership with CIHR. Dr. Holligan was supported by the Public Health Agency of Canada through the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC) Visiting Fellowships (VF) program.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Authors' contributions and statement

SH conceptualized the study and wrote the manuscript. KB conducted the data analyses. SL designed the survey and collected the study data. All authors contributed to the interpretation of the findings and development of manuscript drafts, and approved the final version of the manuscript.

The content and views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Government of Canada.

References

- Footnote 1

-

Butt P, Beirness D, Gliksman L, Paradis C, Stockwell T. Alcohol and health in Canada: a summary of evidence and guidelines for low-risk drinking. Ottawa (ON): Canadian Centre on Substance Abuse; 2011. 66 p.

- Footnote 2

-

Kelly AB, Chan GC, Toumbourou JW, et al. Very young adolescents and alcohol: evidence of a unique susceptibility to peer alcohol use. Addict Behav. 2012;37(4):414-9.

- Footnote 3

-

Monahan KC, Steinberg L, Cauffman E. Affiliation with antisocial peers, susceptibility to peer influence, and antisocial behavior during the transition to adulthood. Dev Psychol. 2009;45(6):1520-30.

- Footnote 4

-

DeWit DJ, Adlaf EM, Offord DR, Ogborne AC. Age at first alcohol use: a risk factor for the development of alcohol disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(5):745-50.

- Footnote 5

-

Wechsler H, Nelson TF. Binge drinking and the American college student: what's five drinks? Psychol Addict Behav. 2001;15(4):287-91.

- Footnote 6

-

Miller JW, Naimi TS, Brewer RD, Jones SE. Binge drinking and associated health risk behaviors among high school students. Pediatrics. 2007;119(1):76-85.

- Footnote 7

-

Statistics Canada. Canadian Community Health Survey (CCHS). Table 13-10-0096-11: Heavy drinking, by age group [Internet]; Ottawa (ON): Statistics Canada; 2018 [cited 2019 July]. Available from: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=1310009611

- Footnote 8

-

McCarty CA, Ebel BE, Garrison MM, et al. Continuity of binge and harmful drinking from late adolescence to early adulthood. Pediatrics. 2004;114(3):714-9.

- Footnote 9

-

Verster JC, Benson S, Johnson SJ, Alford C, Godefroy SB, Scholey A. Alcohol mixed with energy drink (AMED): a critical review and meta-analysis. Hum Psychopharmacol [Internet]. 2018 [cited 2019 Nov];33(2):e2650. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5901036/pdf/HUP-33-na.pdf

- Footnote 10

-

Verster JC, Aufricht C, Alford C. Energy drinks mixed with alcohol: misconceptions, myths, and facts. Int J Gen Med [Internet]. 2012 [cited 2018 Nov];5:187-98. Available from: https://www.dovepress.com/energy-drinks-mixed-with-alcohol-misconceptions-myths-and-facts-peer-reviewed-article-IJGM

- Footnote 11

-

Kypri K, Paschall MJ, Langley J, Baxter J, Cashell-Smith M, Bourdeau B. Drinking and alcohol-related harm among New Zealand university students: findings from a national web-based survey. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2009;33(2):307-14.

- Footnote 12

-

Palmer RH, Young SE, Hopfer CJ, et al. Developmental epidemiology of drug use and abuse in adolescence and young adulthood: evidence of generalized risk. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;102(1-3):78-87.

- Footnote 13

-

Herciu AC, Laxer RE, Cole A, Leatherdale ST. A cross-sectional study examining factors associated with youth binge drinking in the COMPASS study: year 1 data. J Alcohol Drug Depend [Internet]. 2014 [cited 2018 Nov];2(4):172. Available from: https://www.longdom.org/open-access/a-crosssectional-study-examining-factors-associated-with-youth-binge-drinking-in-the-compass-study-year-data-2329-6488.1000172.pdf

- Footnote 14

-

Stanton B, Li X, Pack R, Cottrell L, Harris C, Burns JM. Longitudinal influence of perceptions of peer and parental factors on African American adolescent risk involvement. J Urban Health. 2002;79(4):536-48.

- Footnote 15

-

Crosnoe R. Academic and health-related trajectories in adolescence: the intersection of gender and athletics. J Health Soc Behav . 43(3):317-35.

- Footnote 16

-

Leatherdale ST, Brown S, Carson V, et al. The COMPASS study: a longitudinal hierarchical research platform for evaluating natural experiments related to changes in school-level programs, policies and built environment resources. BMC Public Health [Internet]. 2014 [cited 2018 Aug];14(1):331. Available from: https://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2458-14-331

- Footnote 17

-

Costa FM, Jessor R, Turbin, MS. Transition into adolescent problem drinking: the role of psychosocial risk and protective factors. J Stud Alcohol. 1999;60(4):480-90.

- Footnote 18

-

Weatherson KA, O'Neill M, Lau EY, Qian W, Leatherdale ST, Faulkner GEJ. The protective effects of school connectedness on substance use and physical activity. J Adolesc Health. 2018;63(6):724-31.

- Footnote 19

-

Patte KA, Qian W, Leatherdale ST. Binge drinking and academic performance, engagement, aspirations, and expectations: a longitudinal analysis among secondary school students in the COMPASS study. Health Promot Chronic Dis Prev Can. 2017;37(11):376-85.

- Footnote 20

-

Ontario Agency for Health Protection and Promotion (Public Health Ontario). At a glance: the eight steps for developing a municipal alcohol policy. Toronto (ON): Queen's Printer for Ontario; 2014. 3 p.

- Footnote 21

-

The Alcohol Locally Driven Collaborative Project (LDCP) Team . Addressing alcohol consumption and alcohol-related harms at the local level. Toronto (ON): Public Health Ontario; 2014. 222 p.

- Footnote 22

-

de Goeij MC, Jacobs MA, van Nierop P, et al. Impact of cross-sectoral alcohol policy on youth alcohol consumption. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2016;77(4):596-605.

- Footnote 23

-

Kirst M, Mecredy G, Chaiton M. The prevalence of tobacco use co-morbidities in Canada. Can J Public Health. 2013;104(3):e210-e215.

- Footnote 24

-

Government of Canada. Detailed tables for the Canadian Student Tobacco, Alcohol and Drugs Survey 2016-17 [Internet]. Table 14: Past twelve-month use and mean age at first use of alcohol and cannabis 1, by sex, Canada, 2016-17. Ottawa (ON): Government of Canada. 2018 [cited 2018 Nov]. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/canadian-student-tobacco-alcohol-drugs-survey/2016-2017-supplementary-tables.html#t14

- Footnote 25

-

Thompson-Haile A, Bredin C, Leatherdale ST. Rationale for using active-information passive-consent permission protocol in COMPASS. Waterloo (ON): University of Waterloo and Canadian Institutes of Health Research. Compass Technical Report Series, 1(6). 2013. 10 p.