Evidence synthesis – Physical activity and social connectedness interventions in outdoor spaces among children and youth: a rapid review

Health Promotion and Chronic Disease Prevention in Canada

Alexander Wray, HBESFootnote 1Footnote 2; Gina Martin, PhDFootnote 1Footnote 2; Emma Ostermeier, HBScFootnote 1Footnote 2; Alina Medeiros, HBHScFootnote 1Footnote 2; Malcolm Little, HBAFootnote 1Footnote 2; Kristen Reilly, PhDFootnote 1Footnote 2; Jason Gilliland, PhDFootnote 1Footnote 2Footnote 3

https://doi.org/10.24095/hpcdp.40.4.02

This article has been peer reviewed.

Author references

- Footnote 1

-

Human Environments Analysis Lab, Department of Geography, Western University, London, Ontario, Canada

- Footnote 2

-

Children’s Health Research Institute, London, Ontario, Canada

- Footnote 3

-

School of Health Studies, Department of Paediatrics, Department of Epidemiology & Biostatistics, Western University, London, Ontario, Canada

Correspondence: Jason Gilliland, Social Science Centre Rm. 2333, 1151 Richmond Street, London, ON N6A 3K7; Email: jgillila@uwo.ca

Abstract

Introduction: The rise in sedentary behaviour, coupled with the decline in overall mental health among Canadian children and youth in recent decades, demonstrates a clear need for applied research that focusses on developing and evaluating cross-disciplinary interventions. Outdoor spaces provide opportunities for physical activity and social connectedness, making them an ideal setting to address these critical health concerns among children and youth.

Methods: We conducted a rapid review of peer-reviewed (n = 3096) and grey literature (n = 7) to identify physical activity and/or social connectedness outdoor space interventions targeted at children and youth (19 years and under) in Australia and New Zealand, Canada, Europe and the United States. We determined if interventions were effective by analyzing their research design, confidence intervals and reported limitations, and then conducted a narrative synthesis of the effective interventions.

Results: We found 104 unique studies, of which 70 (67%) were determined to be effective. Overall, 55 interventions targeted physical activity outcomes, 10 targeted social connectedness outcomes and 5 targeted both. Play (n = 47) and contact with nature (n = 25) were dominant themes across interventions, with most taking place in a school or park. We report on the identifying features, limitations and implications of these interventions.

Conclusion: The incorporation of natural and play-focussed elements into outdoor spaces may be effective ways to improve physical activity and social connectedness. There is a considerable need for more Canadian-specific research. Novel methods, such as incorporating smartphone technology into the design and evaluation of these interventions, warrant consideration.

Keywords: environment design, exercise, social capital, recreational park, nature, adolescent, child, review

Highlights

- Contact with nature and play are integral elements of interventions that effectively promote higher physical activity and improve social connectedness among children and youth in outdoor spaces.

- Technology is an emerging delivery mechanism for outdoor-based interventions that target physical activity and social connectedness outcomes among primary school (5–12 years old) and teenage (13–19 years old) populations.

- Youth (13–19 years old) are an understudied population for interventions with physical activity and social connectedness outcomes.

- Canadian-specific research about physical activity and social connectedness among children and youth in outdoor spaces is limited, even though there is government policy tailored to address these activities.

Introduction

Adequate amounts of daily physical activity are important for the optimal growth and development of children and youth. Routine moderate-to-vigorous physical activity is linked to multiple health benefits including reduced risk of high blood pressure, obesity, heart disease, stroke, different types of cancer and depression.Footnote 1Footnote 2 Beyond health indicators, additional moderate-to-vigorous physical activity has been linked to greater academic achievement, improved cognitive performance and higher self-esteem.Footnote 3

Social connectedness has also been linked to outdoor spaces, although the evidence is not as robust as for the link between physical activity and outdoor spaces. Green spaces have been linked to a stronger sense of place which, in turn, leads to stronger community identity and more vibrant relationship networks.Footnote 4 Other individual and group-level factors affect social connectedness, but outdoor spaces can reinforce these associations.Footnote 5Footnote 6 For example, recreational activities in neighbourhood outdoor spaces provide opportunities for interaction with others, thus promoting the formation of social connections across populations.Footnote 5Footnote 7

The notable decline in physical activity levels and rise in a sense of social isolation experienced by Canadian children and youth in recent decades demonstrates a clear need for applied research that focusses on developing and evaluating interventions to address physical activity and social interaction.Footnote 8Footnote 9 Outdoor spaces, which we define as including all natural, water, sporting, playground and hardscaped public open spaces, typically provide opportunities to connect with nature, pursue recreational activities and facilitate social connection.Footnote 10 Such spaces provide ideal settings, in our view, to deliver interventions that address physical inactivity and lack of social interaction.Footnote 11

Interaction with outdoor spaces, specifically natural and naturalized urban spaces, has been associated with positive outcomes across physical, mental, social, emotional and cognitive measures of health and well-being.Footnote 7Footnote 12Footnote 13 Areas with naturally derived obstacles—dynamic playscapes—can particularly encourage children and youth to engage in active, thrilling and risky play. These opportunities for play can independently test their abilities and limits, thereby fostering the development of social resilience.Footnote 14Footnote 15

Outdoor spaces play an important role in encouraging physical activity and promoting social contact between children and youth.Footnote 5Footnote 16 Specifically, research has found a positive relationship between naturalized spaces and leisure-time activities, such as active play, walking and cycling.Footnote 5 Trails in outdoor spaces may be suitable for active transportation, which is an effective way for children and youth to achieve recommended levels of daily physical activity.Footnote 17 Further, the natural aesthetic of these environments significantly increases the desirability of walking and cycling.Footnote 18

While substantial cross-sectional evidence exists on the effects of outdoor settings on various dimensions of mental health, there has been little research on how such spaces can be designed to increase social connection.Footnote 12 Childhood wellness has been directly tied to social connection.Footnote 19 Specifically, increased interactions between children and youth appear to improve social skills, which increases social connection to others.Footnote 20 The creation of positive relationships at a young age may protect against poor health outcomes later in life.Footnote 20Footnote 21 On the contrary, poor social relationships at younger ages have been associated with substance abuse, depression, anxiety, poor relationships and decreased academic performance in late youth.Footnote 22 Social connection and physical activity are routinely shaped by outdoor space, making it an ideal setting for population health interventions.

The links between the characteristics of outdoor spaces and physical activity or social connectedness show how built environment factors influence health behaviours in children and youth. However, to understand how physical activity and social connectedness, in particular, may be improved through outdoor spaces, we need to examine interventions that target both these spaces and populations. Much of the evidence base that focusses on the role of outdoor spaces in shaping physical activity and social connectedness is cross-sectional, with little testing of interventions that alter health behaviours through environmental or social modifications.Footnote 4Footnote 5Footnote 6Footnote 8Footnote 9Footnote 19 Accordingly, this review identifies and synthesizes peer-reviewed and grey literature that addresses outdoor space interventions targeted at physical activity and/or social connectedness among children and youth.

Rationale

The Chief Public Health Officer of Canada’s Report on the State of Public Health in Canada 2017: Designing Healthy Living explored the influences of community design and infrastructure on physical and mental health.Footnote 23 Outdoor spaces, such as parks, public plazas, forests and trails, were identified as important settings for promoting change that positively affects the health of the Canadian population. Federal, provincial and territorial governments have also recognized the importance of these spaces and places in shaping physical activity through the 2018 Common Vision for Increasing Physical Activity and Reducing Sedentary Living in Canada: Let’s get moving.Footnote 11 This document recognizes that children and youth are the most efficient population to receive targeted interventions given the ability to build the foundations for lifelong healthy habits. In addition, interventions targeted at children and youth could promote healthier and more socially engaging environments that are beneficial to everyone. Although all populations are equally deserving of intervention-based research and policy initiatives, research focussing on adult populations was beyond the scope of this review.

To investigate the Public Health Agency of Canada’s policy priority of increasing physical activity and improving social connectedness among children and youth, we undertook a rapid review of outdoor space interventions. Our aim was to identify interventions that have the greatest positive effects on childhood physical activity and social connectedness. This review critically synthesizes interventions in outdoor spaces that have outcome measures for physical activity or social connectedness among children and youth (aged 19 years and less) from Australia, Canada, Europe (including Turkey), New Zealand and the United States of America (USA). This is a research-focussed summary of the findings from a review, undertaken at the request of the Public Health Agency of Canada’s Centre for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Equity in early 2019.

Methods

We undertook a rapid review of peer-reviewed and grey literature using a two-stage open-ended process. A rapid review is a systematic assessment of established knowledge about a topic that captures the volume and overall direction of the literature. We elected to use a rapid review approach because of the need for an expedited timeline to inform further research and policy in this area. The comprehensiveness of the search, thoroughness of the quality assessment and details of the synthesis are limited by this methodology.Footnote 24

Search strategy

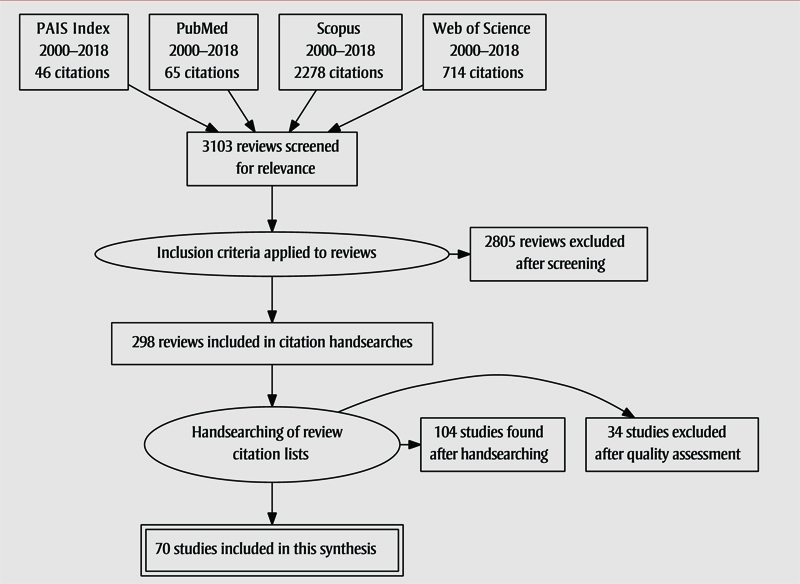

This rapid review used a two-stage process. In the first stage, we undertook a keyword search in PAIS Index, PubMed, Scopus and Web of Science for systematic literature reviews and meta-analyses published between 2000 and 2018 (Table 1). These studies explored outdoor settings from the perspective of physical activity or social connectedness.

| Database | Search string |

|---|---|

| PAIS Index | ( NOFT( ( "built environment" OR "social environment" OR "natural environment" OR "outdoor space" OR greenspace OR "green space" OR brownfield OR "public space" OR "open space" OR "recreational space" OR playground OR school ) AND ( "physical activity" OR exercise OR "outdoor play" OR "outdoor activity" OR "physical health" OR "social cohesion" OR "social interaction" OR "social capital" OR ( social AND ( connect* ) ) OR "mental health" OR wellbeing OR well-being OR wellness ) ) AND NOFT( infant OR toddler OR child OR children OR childhood OR adolescent OR teen OR teenager OR youth ) ) AND NOFT( review AND ( rapid OR scoping OR systematic OR "of reviews" OR literature ) ) |

| PubMed | (((Environment Design[MeSH Terms]) AND (("Adolescent"[Mesh]) OR "Child"[Mesh]))) AND "Review" [Publication Type] |

| Scopus | ( TITLE-ABS-KEY ( ( "built environment" OR "social environment" OR "natural environment" OR "outdoor space" OR greenspace OR "green space" OR brownfield OR "public space" OR "open space" OR "recreational space" OR playground OR school ) AND ( "physical activity" OR exercise OR "outdoor play" OR "outdoor activity" OR "physical health" OR "social cohesion" OR "social interaction" OR "social capital" OR ( social AND ( connect* ) ) OR "mental health" OR wellbeing OR well-being OR wellness ) ) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY ( infant OR toddler OR child OR children OR childhood OR adolescent OR teen OR teenager OR youth ) ) AND TITLE-ABS-KEY ( review AND ( rapid OR scoping OR systematic OR "of reviews" OR literature ) ) |

| Web of Science | ( TS=(children OR adolescents OR youth) AND TS=("physical activity" OR "mental health" OR wellbeing OR well-being OR "social capital" OR "social cohesion" OR "social connection" OR "social connectedness") ) AND ( TS=(greenspace OR "green space" OR "outdoor space" OR park OR "public space" OR brownfield OR "open space") ) |

This stage of the search returned 3103 reviews, of which 298 were determined to be potentially relevant to our investigation.

In the second stage of the search process, five independent reviewers manually searched the results sections of these 298 systematic reviews and meta-analyses for studies on interventions in outdoor spaces with populations aged 19 years or less, from Australia, Canada, Europe, New Zealand or the USA, that had at least one outcome measure for physical activity or social connectedness. As stated earlier, we defined outdoor spaces as including all natural, water, sporting, playground and hardscaped public open spaces.

This stage of the search yielded 104 unique intervention studies. We report on 70 (67%) that we determined to be of sufficient quality and impact for inclusion in the review (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Rapid review search process diagram

Figure 1 - Text Equivalent

| Level (Top to Bottom) |

Position (Left to Right) | Text |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1 | PAIS Index 2000–2018: 46 citations |

| 1 | 2 | PubMed 2000–2018 65: citations |

| 1 | 3 | Scopus 2000–2018: 2278 citations |

| 1 | 4 | Web of Science 2000–2018: 714 citations |

| 2 | 1 | 3103 reviews screened for relevance |

| 3 | 1 | Inclusion criteria applied to reviews |

| 3 | 2 | 2805 reviews excluded after screening |

| 4 | 1 | 298 reviews included in citation handsearches |

| 5 | 1 | Handsearching of review citation lists |

| 5 | 2 | 104 studies found after handsearching |

| 5 | 3 | 34 studies excluded after quality assessment |

| 6 | 1 | 70 studies included in this synthesis |

Selection criteria

The selection criteria—age, setting (outdoor spaces), location and outcome measure (physical activity and social connectedness)—were developed with public health practitioners based on their research and policy needs.

We adopted the World Health Organization’s Global Strategy on Diet, Physical Activity and Health definition of physical activity as bodily movement that occurs as part of structured exercise, play, work, mobility or recreation.Footnote 2 We considered social connectedness as encapsulating the presence, quantity and quality of social interaction between people.Footnote 19 These definitions were used to make scoping decisions and synthesize the evidence base.

Scoping, screening and quality assessment

We developed a quality assessment tool to determine the internal reliability and external validity of each intervention study. Scoping, screening and quality assessment decisions were completed by at least two reviewers, working independently. Disagreements were resolved through consensus after discussion with a third team member.

We assessed the research design and reporting of each study to determine the validity of its findings. This approach was inspired by other standardized quality assessment protocols. However, given the design of our review methodology, the lack of quality assessment tools in this subject area and the broad variation in methodological design and outcome measures of each intervention study, our approach is not a traditional marker of study quality.Footnote 25 Rather, our bespoke quality assessment uses an approach rooted in the core principles of quality appraisal to retrieve studies demonstrating interventions that effectively increase physical activity and/or social connectedness in children and youth.Footnote 25

We assessed the quality of studies based on four types of validity. Internal validity was assessed by examining the reporting of limitations in the study. Construct validity was assessed by comparing the composition of the sample to the expected population and by appraising the reporting of the intervention’s implementation. External validity was assessed by appraising the suitability of a study’s methodological approach compared to its conclusions. Statistical conclusion validity was assessed by accounting for the study’s sample size and reported effect sizes.

We excluded any study that at least two reviewers independently assessed as having one or more major flaws in internal, construct, external or statistical conclusion validity. As such, our review is a distillation of intervention-type studies that could be used to inform the development of future interventions, and in particular, the evaluations of these interventions to build a more robust evidence base.

Data extraction and synthesis

At least two reviewers, working independently, extracted bibliographic details and information about the population, intervention, context, outcome, timing and setting for each study determined to be relevant and of sufficient quality according to its research design, confidence intervals and reported strengths and limitations. Disagreements were resolved through discussion until consensus was reached. Results were synthesized based on their common thematic elements as determined by public health practitioner interest.

Results

The quality assessment rendered 70 unique intervention studies for this critical narrative synthesis. The bulk of the interventions focussed on physical activity outcomes (n = 55); a few explored social connectedness (n = 10) or both outcomes together (n = 5). Play (n = 47) and contact with nature (n = 25) were dominant themes across interventions, with most taking place in a school (n = 48) or public park (n = 11). The majority (n = 64) of studies worked with preschool or elementary school-aged children (<13 years), with a few (n = 20) interventions engaging with secondary school-age populations (13–19 years). Effect sizes (Cohen’s d) in Tables 2, 3 and 4 are reported at the 95% confidence level using information (i.e. means, standard deviations, sample size) described in the associated manuscript.

Physical activity

We found 55 interventions that had a physical activity outcome, including 8 in Australia and New Zealand, 3 in Canada, 15 in Europe (including Turkey) and 29 in USA (Table 2). The most popular form of intervention involved modifying the built environment or providing additional equipment and supports for moderate-to-vigorous physical activity.Footnote 26Footnote 27Footnote 28Footnote 29Footnote 30Footnote 31Footnote 32Footnote 33Footnote 34Footnote 35Footnote 36Footnote 37Footnote 38Footnote 39Footnote 40Footnote 41Footnote 42Footnote 43 Other interventions deployed programmingFootnote 44Footnote 45Footnote 46Footnote 47Footnote 48Footnote 49Footnote 50Footnote 51Footnote 52Footnote 53 or curriculum changes involving outdoor spaceFootnote 54Footnote 55Footnote 56Footnote 57Footnote 58Footnote 59Footnote 60Footnote 61Footnote 62Footnote 63 to promote physical activity. The concept of fostering spontaneous play in school and community-based settings was often an underlying component of these interventions.

| Ref. | Effect (95% CI) | Sample size (n) | Intervention | Design | Age group | Setting |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (47) USA |

3.28 (2.32, 4.24) | 54 | Education and support groups | CCT | Primary | Parks |

| (58) USA |

0.66 (0.52, 0.80) | 1849 | Education and support groups | RCT | Primary Teen |

Education |

| (60) EU |

1.10 (1.01, 1.19) | 19 | Naturalized outdoor spaces | ITS | Primary | Education |

| (61) USA |

0.87 (0.65, 1.11) | 211 | Naturalized outdoor spaces | CCT | Primary | Education |

| (78) USA |

0.75 (0.34, 1.16) | 152 | Active and safe routes to school | RCT | Primary | Community |

| (49) USA |

2.04 (1.71, 2.37) | 147 | Naturalized outdoor spaces | CCT | Primary | Parks |

| (63) AN |

2.00 (1.99, 2.01) | 2965 | Education and support groups | RCT | Primary | Education |

| (57) EU |

0.02 (−0.66, 0.70) | 2287 | Recess programs and supervision | RCT | Primary | Education |

| (79) EU |

0.46 (0.36, 0.56) | 2840 | Recess programs and supervision | RCT | Primary Teen |

Education |

| (33) AN |

1.55 (1.47, 1.63) | 102 | Naturalized outdoor spaces | ITS | Primary | Education |

| (59) EU |

0.88 (−11.9, 13.7) | 19 | Naturalized outdoor spaces | ITS | Primary | Education |

| (77) EU |

1.29 (1.07, 1.51) | 1793 | Education and support groups | ITS | Primary Teen |

Education |

| (54) AN |

3.99 (−52.3, 60.3) | 97 | Education and support groups | ITS | Primary | Education |

| (68) EU |

0.99 (0.89, 1.10) | 3336 | Active and safe routes to school | CCT | Primary | Community |

| (71) USA |

3.33 (3.21, 3.45) | 653 | Active and safe routes to school | ITS | Primary | Education |

| (69) USA |

2.97 (2.33, 3.61) | 324 | Active and safe routes to school | CCT | Primary | Education |

| (72) USA |

0.30 (−1.18, 1.78) | 149 | Active and safe routes to school | ITS | Primary | Education |

| (45) AN |

−0.26 (−1.00, 0.48) | 480 | Recess programs and supervision | ITS | Primary | Education |

| (30) CA |

Improvement | 400 | Naturalized outdoor spaces | Q | Primary | Education |

| (43) EU |

0.18 (−2.65, 3.01) | 235 | Play equipment | CCT | Primary | Education |

| (70) USA |

0.09 (0.01, 0.17) | 3315 | Active and safe routes to school | CCT | Primary | Education |

| (40) USA |

Improvement | 5 | Built environment modification | Q | Primary | Parks |

| (28) USA |

0.95 (0.89, 1.01) | 56 | Naturalized outdoor spaces | ITS | Preschool | Education |

| (26) EU |

0.01 (−0.88, 1.07) | 412 | Play equipment | CCT | Primary | Education |

| (27) USA |

1.42 (1.40, 1.44) | 9407 | Naturalized outdoor spaces | CCT | Primary | Education |

| (29) USA |

0.73 (0.57, 0.89) | 377 | Play equipment | ITS | Teen | Community |

| (67) USA |

1.60 (1.38, 1.82) | 2207 | Built environment modification | ITS | Primary Teen |

Community |

| (36) USA |

1.03 (0.86, 1.19) | 2712 | Naturalized outdoor spaces | Obs. | Preschool Primary Teen |

Parks |

| (32) USA |

8.33 (8.04, 8.62) | 64 | Play equipment | ITS | Preschool | Education |

| (38) USA |

2.13 (0.80, 3.46) | 107 | Naturalized outdoor spaces | ITS | Preschool | Education |

| (73) USA |

4.37 (−13.4, 22.2) | 20 | Active and safe routes to school | ITS | Teen | Community |

| (41) EU |

0.61 (−3.92, 5.14) | 60 | Play equipment | CCT | Primary | Education |

| (34) USA |

1.79 (1.38, 2.20) | 309 | Play equipment | Obs. | Primary | Education |

| (75) EU |

0.72 (−8.13, 9.57) | 313 | Active and safe routes to school | ITS | Primary | Education |

| (65) EU |

0.82 (0.39, 1.25) | 126 | Regulatory changes | ITS | Primary | Community |

| (44) USA |

2.00 (1.94, 2.06) | 710 | Recess programs and supervision | CCT | Primary | Community |

| (50) CA |

1.22 (1.18, 1.26) | 5200 | Education and support groups | CCT | Primary | Education |

| (46) USA |

0.74 (−0.01, 1.49) | 262 | Recess programs and supervision | RCT | Primary | Education |

| (48) AN |

5.80 (2.00, 9.60) | 497 | Built environment modification | Obs. | Primary Teen |

Parks |

| (53) USA |

0.32 (0.19, 0.45) | 227 | Naturalized outdoor spaces | CCT | Primary | Education |

| (51) USA |

1.6 (0.00, 3.33) | 8727 | Naturalized outdoor spaces | RCT | Primary Teen |

Education |

| (56) AN |

1.8 (0.50, 3.10) | 221 | Recess programs and supervision | RCT | Primary | Education |

| (55) USA |

0.58 (0.51, 0.65) | 1582 | Education and support groups | RCT | Primary | Education |

| (66) EU |

1.41 (1.15, 1.67) | 1359 | Active and safe routes to school | CCT | Primary Teen |

Education |

| (62) EU |

0.16 (−1.58, 1.90) | 797 | Recess programs and supervision | RCT | Primary | Education |

| (42) EU |

2.00 (1.67, 2.33) | 128 | Built environment modification | ITS | Primary | Education |

| (52) USA |

0.48 (−2.16, 3.12) | 21 | Recess programs and supervision | CCT | Primary | Education |

| (35) AN |

1.08 (0.94, 1.22) | 459 | Education and support groups | ITS | Preschool | Education |

| (31) USA |

0.57 (0.38, 0.76) | 1206 | Recess programs and supervision | RCT | Primary | Education |

| (39) AN |

12.5 (−13.0, 38.0) | 1582 | Built environment modification | RCT | Primary Teen |

Education |

| (76) USA |

2.24 (0.19, 4.29) | 442 | Recess programs and supervision | Obs. | Primary | Education |

| (37) EU |

0.79 (−58.2, 59.8) | 247 | Recess programs and supervision | RCT | Primary | Education |

| (80) CA |

3.21 (3.12, 3.30) | 3817 | Active and safe routes to school | ITS | Primary | Community |

| (64) USA |

1.30 (0.20, 2.30) | 104 | Regulatory changes | CCT | Primary Teen |

Community |

| (74) USA |

2.86 (2.77, 2.95) | 187 | Active and safe routes to school | Obs. | Primary | Community |

| Abbreviations: AN, Australia & New Zealand; CA, Canada; CCT, case–control trial; CI, confidence interval; EU, Europe; ITS, Interrupted time series; Obs., observational; Q, Qualitative; RCT, randomized controlled trial; USA, United States of America. | ||||||

Technology was sometimes used as a delivery mechanism for the intervention. In addition, some interventions leveraged active travel as a way to increase physical activity through walking school buses or improved cycling supports.Footnote 64Footnote 65Footnote 66Footnote 67Footnote 68Footnote 69Footnote 70Footnote 71Footnote 72Footnote 73Footnote 74Footnote 75 An emerging area for population-level intervention research is the use of smartphone and remote sensing technology to deliver interventions to children and youth.Footnote 76Footnote 77Footnote 78Footnote 79Footnote 80 In short, physical activity interventions often combine environmental supports and programming with a play-based approach to reduce knowledge and contextual barriers to participation.

Social connectedness

We found 10 interventions with outcomes related to social connectedness, from across Australia and New Zealand (n = 1), Europe (n = 4) and the USA (n = 5) (Table 3). Many interventions identified increasing exposure to nature as a pathway to increasing social connectedness.Footnote 81Footnote 82Footnote 83Footnote 84Footnote 85 In addition, some interventions modified features of the built and social environment to increase opportunities for social interaction.Footnote 86Footnote 87Footnote 88Footnote 89Footnote 90 These opportunities were rooted in promoting spontaneous and organized play; sometimes they leveraged technology to connect participants. Effective interventions that increase social connectedness appear to rely on creating supportive environments with high exposure to natural elements.

| Ref. | Effect (CI 95%) | Sample (n) | Intervention | Study design | Age group | Setting |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (83) EU |

1.29 (−2.45, 5.03) | 8 | Naturalized outdoor spaces | ITS | Primary | Parks |

| (85) USA |

3.77 (2.88, 4.66) | 598 | Naturalized outdoor spaces | CCT | Primary | Education |

| (86) AN |

0.55 (−0.08, 1.19) | 20 | Play equipment | ITS | Primary | Parks |

| (87) USA |

Improvement | 50 | Naturalized outdoor spaces | Q | Primary Teen |

Parks |

| (90) EU |

Improvement | 18 | Built environment modification | Q | Preschool Primary Teen |

Parks |

| (81) EU |

0.09 (0.00, 0.17) | 223 | Naturalized outdoor spaces | CCT | Teen | Education |

| (82) USA |

0.48 (0.02, 0.94) | 112 | Naturalized outdoor spaces | ITS | Teen | Education |

| (89) USA |

0.32 (0.16, 0.48) | 27 | Recess programs and supervision | ITS | Preschool | Education |

| (84) USA |

3.12 (−1.68, 7.92) | 24 | Education and support groups | ITS | Primary Teen |

Parks |

| (88) EU |

4.49 (1.93, 10.44) | 1347 | Built environment modification | CCT | Teen | Education |

| Abbreviations: AN, Australia & New Zealand; CA, Canada; CCT, case–control trial; CI, confidence interval; EU, Europe; ITS, interrupted time series; Obs., observational; Q, qualitative; RCT, randomized controlled trial; USA, United States of America. | ||||||

Joint outcomes

We identified five interventions in Europe (n = 4) and the USA (n = 1) that had outcomes for both physical activity and social connectedness (Table 4). These interventions typically involved modifying the built or natural environment to create opportunities for physical activity and social connection.Footnote 91Footnote 92Footnote 93 Alternatively, interventions used physical activity as an opportunity to promote social connection.Footnote 94Footnote 95 These multifaceted interventions seem to provide the most impactful solutions, as they can improve both physical activity and social connectedness among children and youth.

| Ref. | Effect (CI 95%) | Sample (n) | Intervention | Design | Age | Setting |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (94) EU |

0.42 (−2.4, 10.1) | 38 | Education and support groups | RCT | Teen | Education |

| (93) USA |

1.58 (1.37, 1.79) | 112 | Built environment modifications | CCT | Primary Teen |

Parks |

| (91) USA |

0.62 (0.76, 0.90) | 27 | Naturalized outdoor spaces | ITS | Preschool | Education |

| (95) USA |

3.14 (1.82, 4.46) | 27 | Recess programs and supervision | CCT | Primary | Education |

| (92) USA |

2.39 (2.27, 2.51) | 58 | Active and safe routes to school | CCT | Primary | Community |

| Abbreviations: AN, Australia & New Zealand; CCT, case–control trial; CA, Canada; CI, confidence interval; EU, Europe; ITS, interrupted time series; Obs., observational; Q, qualitative; RCT, randomized controlled trial; USA, United States of America. | ||||||

Discussion

The broad concern about activity levels and socialization among children and youthFootnote 8Footnote 9 provides the impetus for further studies that can identify interventions that get children and youth outdoors. All three levels of government in Canada have made moves to better support public use of outdoor spaces through funding, programming and staff training. Therefore, it is ideal to evaluate work that either captures the effects of ongoing interventions in local communities or develops new interventions for the Canadian context that are informed by international evidence.

Contact with nature is recognized as an integral part of health and well-being in all populations. The interventions included in our review suggest opportunities for both physical activity and social connection among children and youth often occur in natural and play-encouraging outdoor spaces. Many of the physical activity-related studies reviewed identified the presence of nature as a moderator of the intervention’s effect on physical activity.Footnote 30Footnote 36Footnote 38 Naturalized environments were noted as being a clear determinant of social connection between children and youth.Footnote 81Footnote 82Footnote 83Footnote 84Footnote 85 Given Canada’s high rate of naturalized space per capita for over 90% of households,Footnote 96 nature should be viewed as a fundamental component of any intervention with a physical activity or social connectedness outcome.

Play is an important element of most physical activity interventions. Interventions from FranceFootnote 26 and the United KingdomFootnote 41 provide excellent examples of how to easily increase participation in moderate-to-vigorous physical activity through playground markings and with proactive supervision by staff who promote children’s games and movement. Play equipment is a common feature of many public outdoor spaces in Canada. However, much of this equipment consists of traditional playground structures (i.e. slides, swings, jungle gyms) that do not typically foster high levels of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity.Footnote 10 Riskier play may incentivize higher physical activity and improve social connectedness, but the studies reviewed do not include data on injuries and other consequences from these types of interventions.Footnote 97 Youth could be engaged with outdoor spaces through access to free game equipment or if they had digital challenges to compete in against friends.Footnote 43Footnote 98

Technology is an emerging area of interest.Footnote 54Footnote 76Footnote 79Footnote 80 Given the high adoption rate of mobile devices, plus the myriad sensors and devices being placed in Canadian urban environments, technologies could be used to deliver and track the effects of health interventions with a view to preventing chronic disease.Footnote 99 A few of the interventions reviewed included technological elements, with some gamifying simple physical activities like walking to school or running around a track.Footnote 79Footnote 80 Future Canadian-specific interventions could apply a technological element to the delivery or monitoring element of existing interventions to improve data collection efficiency and encourage higher uptake of the intervention among children and youth. For example, traditional observational methods for collecting data on the use of playground equipmentFootnote 26Footnote 34Footnote 41Footnote 76 could be replaced with anonymized pattern-recognition camera technology to detect when children are engaging in moderate-to-vigorous physical activity. Moreover, compared to traditional email and paper-based techniques,Footnote 54Footnote 78 a GPS-enabled mobile phone application could deliver recommendations about activities and outdoor spaces to visit when in geographical proximity to these spaces. Such a user-friendly approach explicitly provides opportunities for physical activity and chance social encounters among youth.

Strengths and limitations

This rapid review encapsulates the available literature on the connections between physical activity, social connectedness, outdoor spaces and population-level health interventions. As part of the review, expert reviewers undertook a systematic search and clearly documented the review process. This methodological approach ensures reproducibility and transparency.

However, the use of a rapid review approach could limit the comprehensiveness of the interventions captured in this report. In addition, the lack of a formal standardized quality assessment tool for rapid reviews could limit the generalizability of our findings. Our review is further limited by excluding evidence that was not published in English or was from outside of Australia, Canada, Europe, New Zealand and the USA. The exclusion of interventions by population age could also limit finding interventions for adults that could translate to potential interventions for children and youth.

Conclusion

Our review found a wide range of evidence about interventions that could effectively increase physical activity and improve social connectedness among children and youth. The evidence base aligns with policies at all levels of government in Canada and could be used to guide implementation of detailed interventions at the local level. Moreover, the findings of our review align with other recent evidence syntheses of this topic, particularly on incorporating nature into interventions that improve physical activity and social connectedness outcomes.Footnote 100Footnote 101 However, the lack of Canadian-specific research may hamper the overall applicability of our findings to Canada’s many diverse and vibrant communities.

Further, the results of this review are high-level in nature; this limits their transferability across populations and contexts. Many of the interventions reviewed in this study were only tested and/or shown to be effective in one demographic group and contextual setting, which should not be construed as an evidence-based finding that the intervention works in all contexts with all children and youth populations. There is a clear need for more studies that replicate existing interventions in new contexts and with different populations.

Implications

The interventions identified in this review should be used to inform interventions made by all levels of government, school boards and community actors to create outdoor spaces that contribute to increasing physical activity and social connectedness in children and youth. Policy makers and program delivery staff should reach out to researchers in advance of implementing changes to the built environment or implementing changes to regulatory systems to allow high-quality pre–post studies of the effects of the intervention. In addition, researchers should make their knowledge, expertise and willingness to collaborate known to policy makers and program delivery staff to ensure interventions are of strong methodological design and contribute to the broader evidence base. This collaborative approach would maximize the impact of public funds, advance research-policy partnerships and create a more robust understanding of physical activity and social connectedness interventions. Further, given the underrepresentation of youth across the evidence base, there is a clear need for policy makers and researchers to work collaboratively with youth populations in Canada in both research and practice.Footnote 102

Future research

While there is a large body of international evidence about interventions for increasing physical activity and social connectedness among children and youth, there is a lack of Canadian-specific research. Our review originally captured 104 studies, but only 7 included a Canadian population; of these, only 2 were determined to be of sufficient quality using our quality assessment process. This is not due to a lack of action by governments and civil society to improve the physical activity and social connectedness of children and youth in Canada. Rather, these interventions are not adequately tracked and reported through easily searchable sources. Research practices that can rapidly respond to outdoor space interventions using controlled study designs should be emphasized, and international studies should be replicated in many different Canadian contexts.

The lack of evidence for interventions that could increase physical activity or social connection in secondary school-age populations compared to the volume of evidence available on interventions for preschool and elementary school populations is of concern. Because of concerns about Canadian youth populations disengaging from public life and outdoor spaces,Footnote 103 future research should focus on exploring the unique enablers and barriers to youth participation in physical activity and creating social connections. This research could involve blending technology into outdoor spaces as well as determining the built and natural features that attract youth to outdoor spaces.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank Dawn Sheppard and Ahalya Mahendra of the Centre for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Equity at the Public Health Agency of Canada for their guidance and valuable input on the review. This review was supported by the Public Health Agency of Canada’s Partnerships and Strategies Division, and graduate training awards from the Children’s Health Research Institute.

Authors’ contributions and statement

AW: design and conceptualization of the work, acquisition and interpretation of the data, drafting the manuscript, revising the manuscript; GM: acquisition and interpretation of the data, drafting the manuscript, revising the manuscript; EO: acquisition and interpretation of the data, revising the manuscript; AM: acquisition and interpretation of the data, revising the manuscript; ML: acquisition and interpretation of the data, revising the manuscript; KR: revising the manuscript; JG: the design and conceptualization of the work and revising the manuscript. All authors were responsible for approval of the final manuscript for submission.

The content and views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Government of Canada.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Footnote 1

-

Janssen I, LeBlanc AG. Systematic review of the health benefits of physical activity and fitness in school-aged children and youth. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2010;7:40. doi:10.1186/1479-5868-7-40.

- Footnote 2

-

World Health Organization. Global strategy on diet, physical activity and health [Internet]. Geneva (CH): WHO; 2019 [cited 2019 Feb 27]. Available from: http://www.who.int/dietphysicalactivity/pa/en/

- Footnote 3

-

Biddle SJ, Asare M. Physical activity and mental health in children and adolescents: a review of reviews. Br J Sports Med. 2011;45(11):886-95. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2011-090185.

- Footnote 4

-

Dinnie E, Brown KM, Morris S. Community, cooperation and conflict: negotiating the social well-being benefits of urban greenspace experiences. Landsc Urban Plan. 2013;112:1-9. doi:10.1016/j.landurbplan.2012.12.012.

- Footnote 5

-

van den Berg MM, van Poppel M, van Kamp I, et al. Do physical activity, social cohesion, and loneliness mediate the association between time spent visiting green space and mental health? Environ Behav. 2019;51(2):144-66. doi:10.1177/0013916517738563.

- Footnote 6

-

Dzhambov A, Hartig T, Markevych I, Tilov B, Dimitrova D. Urban residential greenspace and mental health in youth: different approaches to testing multiple pathways yield different conclusions. Environ Res. 2018;160:47-59. doi:10.1016/j.envres.2017.09.015.

- Footnote 7

-

Amoly E, Dadvand P, Forns J, et al. Green and blue spaces and behavioral development in Barcelona schoolchildren: the BREATHE project. Environ Health Perspect. 2014;122(12):1351-8. doi:10.1289/ehp.1408215.

- Footnote 8

-

Colley RC, Carson V, Garriguet D, Janssen I, Roberts KC, Tremblay MS. Physical activity of Canadian children and youth, 2007 to 2015. Statistics Canada; 2017.

- Footnote 9

-

Malla A, Shah J, Iyer S, et al. Youth mental health should be a top priority for health care in Canada. Can J Psychiatry. 2018;63(4):216-22. doi:10.1177/0706743718758968.

- Footnote 10

-

ParticipACTION. The brain + body equation: the 2018 ParticipACTION report card on physical activity for children and youth [Internet]. Toronto (ON): ParticipACTION; 2018 [cited 2019 Apr 17]. Available from: https://www.participaction.com/en-ca/resources/report-card

- Footnote 11

-

Public Health Agency of Canada. A common vision for increasing physical activity and reducing sedentary living in Canada: let’s get moving [Internet]. Ottawa (ON): Government of Canada; 2018 [cited 2019 Apr 17]. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/healthy-living/lets-get-moving.html

- Footnote 12

-

Tillmann S, Tobin D, Avison W, Gilliland J. Mental health benefits of interactions with nature in children and teenagers: a systematic review. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2018;72(10):958-66. doi:10.1136/jech-2018-210436.

- Footnote 13

-

Ward JS, Duncan JS, Jarden A, Stewart T. The impact of children’s exposure to greenspace on physical activity, cognitive development, emotional wellbeing, and ability to appraise risk. Health Place. 2016;40:44-50. doi:10.1016/j.healthplace.2016.04.015.

- Footnote 14

-

Brussoni M, Olsen LL, Pike I, Sleet DA. Risky play and children’s safety: balancing priorities for optimal child development. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2012;9(9):3134-48. doi:10.3390/ijerph9093134.

- Footnote 15

-

Thompson Coon J, Boddy K, Stein K, Whear R, Barton J, Depledge MH. Does participating in physical activity in outdoor natural environments have a greater effect on physical and mental wellbeing than physical activity indoors? A systematic review. Environ Sci Technol. 2011;45(5):1761-72. doi:10.1021/es102947t.

- Footnote 16

-

Coen SE, Mitchell CA, Tillmann S, Gilliland JA. ‘I like the “outernet” stuff:’ girls’ perspectives on physical activity and their environments. Qual Res Sport Exerc Health. 2019;11(5):599-617. doi:10.1080/2159676X.2018.1561500.

- Footnote 17

-

Wendel-Vos GC, Schuit AJ, de Niet R, Boshuizen HC, Saris W, Kromhout D. Factors of the physical environment associated with walking and bicycling. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2004;36(4):725-30. doi:10.1249/01.MSS.0000121955.03461.0A.

- Footnote 18

-

Larsen K, Gilliland J, Hess PM. Route-based analysis to capture the environmental influences on a child’s mode of travel between home and school. Ann Assoc Am Geogr. 2012;102(6):1348-65. doi:10.1080/00045608.2011.627059.

- Footnote 19

-

Umberson D, Montez JK. Social relationships and health: a flashpoint for health policy. J Health Soc Behav. 2010;51(Suppl):S54-66. doi:10.1177/0022146510383501.

- Footnote 20

-

Olsson CA, McGee R, Nada-Raja S, Williams SM. A 32-year longitudinal study of child and adolescent pathways to well-being in adulthood. J Happiness Stud. 2013;14(3):1069-83.

- Footnote 21

-

Carter M, McGee R, Taylor B, Williams S. Health outcomes in adolescence: associations with family, friends and school engagement. J Adolesc. 2007;30(1):51-62. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2005.04.002.

- Footnote 22

-

Bond L, Butler H, Thomas L, et al. Social and school connectedness in early secondary school as predictors of late teenage substance use, mental health, and academic outcomes. J Adolesc Health. 2007;40(4):357.e9-18. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.10.013.

- Footnote 23

-

Tam T. The Chief Public Health Officer’s Report on the State of Public Health in Canada – designing healthy living. Ottawa (ON): Public Health Agency of Canada; 2017 Oct.

- Footnote 24

-

Grant MJ, Booth A. A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Inf Libr J. 2009;26(2):91-108. doi:10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x.

- Footnote 25

-

Valentine JC. Judging the quality of primary research. In: Cooper H, Hedges LV, Valentine JC, editors. The handbook of research synthesis and meta-analysis. 2nd ed. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 2009. pp. 129-46.

- Footnote 26

-

Blaes A, Ridgers ND, Aucouturier J, Van Praagh E, Berthoin S, Baquet G. Effects of a playground marking intervention on school recess physical activity in French children. Prev Med. 2013;57(5):580-4. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2013.07.019.

- Footnote 27

-

Brink LA, Nigg CR, Lampe SM, Kingston BA, Mootz AL, van Vliet W. Influence of schoolyard renovations on children’s physical activity: the Learning Landscapes Program. Am J Public Health. 2010;100(9):1672-8. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2009.178939.

- Footnote 28

-

Coe DP, Flynn JI, Wolff DL, Scott SN, Durham S. Children’s physical activity levels and utilization of a traditional versus natural playground. Child Youth Environ. 2014;24(3):1-15. doi:10.7721/chilyoutenvi.24.3.0001.

- Footnote 29

-

Cohen DA, Marsh T, Williamson S, Golinelli D, McKenzie TL. Impact and cost-effectiveness of family Fitness Zones: a natural experiment in urban public parks. Health Place. 2012;18(1):39-45. doi:10.1016/j.healthplace.2011.09.008.

- Footnote 30

-

Dyment JE, Bell AC, Lucas AJ. The relationship between school ground design and intensity of physical activity. Child Geogr. 2009;7(3):261-76. doi:10.1080/14733280903024423.

- Footnote 31

-

Elder JP, McKenzie TL, Arredondo EM, Crespo NC, Ayala GX. Effects of a multi-pronged intervention on children’s activity levels at recess: the Aventuras para Niños study. Adv Nutr. 2011;2(2):171S-6S. doi:10.3945/an.111.000380.

- Footnote 32

-

Hannon JC, Brown BB. Increasing preschoolers’ physical activity intensities: an activity-friendly preschool playground intervention. Prev Med. 2008;46(6):532-6. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2008.01.006.

- Footnote 33

-

Harten N, Olds T, Dollman J. The effects of gender, motor skills and play area on the free play activities of 8-11 year old school children. Health Place. 2008;14(3):386-93. doi:10.1016/j.healthplace.2007.08.005.

- Footnote 34

-

Farley TA, Meriwether RA, Baker ET, Rice JC, Webber LS. Where do the children play? The influence of playground equipment on physical activity of children in free play. J Phys Act Health. 2008;5(2):319-31. doi:10.1123/jpah.5.2.319.

- Footnote 35

-

Finch M, Wolfenden L, Morgan PJ, Freund M, Jones J, Wiggers J. A cluster randomized trial of a multi-level intervention, delivered by service staff, to increase physical activity of children attending center-based childcare. Prev Med. 2014;58:9-16. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2013.10.004.

- Footnote 36

-

Floyd MF, Bocarro JN, Smith WR, et al. Park-based physical activity among children and adolescents. Am J Prev Med. 2011;41(3):258-65. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2011.04.013.

- Footnote 37

-

Loucaides CA, Jago R, Charalambous I. Promoting physical activity during school break times: piloting a simple, low cost intervention. Prev Med. 2009;48(4):332-4. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2009.02.005.

- Footnote 38

-

Nicaise V, Kahan D, Reuben K, Sallis JF. Evaluation of a redesigned outdoor space on preschool children’s physical activity during recess. Pediatr Exerc Sci. 2012;24(4):507-18. doi:10.1123/pes.24.4.507.

- Footnote 39

-

Parrish AM, Okely AD, Batterham M, Cliff D, Magee C. PACE: A group randomised controlled trial to increase children’s break-time playground physical activity. J Sci Med Sport. 2016;19(5):413-8. doi:10.1016/j.jsams.2015.04.017.

- Footnote 40

-

Pratt B, Hartshorne NS, Mullens P, Schilling ML, Fuller S, Pisani E. Effect of playground environments on the physical activity of children with ambulatory cerebral palsy. Pediatr Phys Ther. 2016;28(4):475-82. doi:10.1097/PEP.0000000000000318.

- Footnote 41

-

Stratton G. Promoting children’s physical activity in primary school: an intervention study using playground markings. Ergonomics. 2000;43(10):1538-46. doi:10.1080/001401300750003961.

- Footnote 42

-

Van Cauwenberghe E, De Bourdeaudhuij I, Maes L, Cardon G. Efficacy and feasibility of lowering playground density to promote physical activity and to discourage sedentary time during recess at preschool: a pilot study. Prev Med. 2012;55(4):319-21. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2012.07.014.

- Footnote 43

-

Verstraete SJ, Cardon GM, De Clercq DL, De Bourdeaudhuij IM. Increasing children’s physical activity levels during recess periods in elementary schools: the effects of providing game equipment. Eur J Public Health. 2006;16(4):415-9. doi:10.1093/eurpub/ckl008.

- Footnote 44

-

Farley TA, Meriwether RA, Baker ET, Watkins LT, Johnson CC, Webber LS. Safe play spaces to promote physical activity in inner-city children: results from a pilot study of an environmental intervention. Am J Public Health. 2007;97(9):1625-31. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2006.092692.

- Footnote 45

-

Ha AS, Burnett A, Sum R, Medic N, Ng JY. Outcomes of the rope skipping ‘STAR’ programme for schoolchildren. J Hum Kinet. 2015;45(1):233-40. doi:10.1515/hukin-2015-0024.

- Footnote 46

-

Huberty JL, Beets MW, Beighle A, Welk G. Environmental modifications to increase physical activity during recess: preliminary findings from ready for recess. J Phys Act Health. 2011;8(s2):S249-56. doi:10.1123/jpah.8.s2.s249.

- Footnote 47

-

Story M, Sherwood NE, Himes JH, et al. An after-school obesity prevention program for African-American girls: the Minnesota GEMS pilot study. Ethn Dis. 2003;13(1 Suppl 1):S54-64.

- Footnote 48

-

Timperio A, Giles-Corti B, Crawford D, et al. Features of public open spaces and physical activity among children: Findings from the CLAN study. Prev Med. 2008;47(5):514-8. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2008.07.015.

- Footnote 49

-

Trost SG, Rosenkranz RR, Dzewaltowski D. Physical activity levels among children attending after-school programs. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2008;40(4):622-9. doi:10.1249/MSS.0b013e318161eaa5.

- Footnote 50

-

Veugelers PJ, Fitzgerald AL. Effectiveness of school programs in preventing childhood obesity: a multilevel comparison. Am J Public Health. 2005;95(3):432-5. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2004.045898.

- Footnote 51

-

Webber LS, Catellier DJ, Lytle LA, et al. Promoting physical activity in middle school girls: trial of activity for adolescent girls. Am J Prev Med. 2008;34(3):173-84. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2007.11.018.

- Footnote 52

-

Weintraub DL, Tirumalai EC, Haydel KF, Fujimoto M, Fulton JE, Robinson TN. Team sports for overweight children: the Stanford Sports to Prevent Obesity Randomized Trial (SPORT). Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2008;162(3):232-7. doi:10.1001/archpediatrics.2007.43.

- Footnote 53

-

Wells NM, Myers BM, Henderson CR. School gardens and physical activity: a randomized controlled trial of low-income elementary schools. Prev Med. 2014;69:S27-33. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.10.012.

- Footnote 54

-

Duncan S, McPhee JC, Schluter PJ, Zinn C, Smith R, Schofield G. Efficacy of a compulsory homework programme for increasing physical activity and healthy eating in children: the healthy homework pilot study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2011;8(1):127. doi:10.1186/1479-5868-8-127.

- Footnote 55

-

Dzewaltowski DA, Estabrooks PA, Welk G, et al. Healthy youth places: a randomized controlled trial to determine the effectiveness of facilitating adult and youth leaders to promote physical activity and fruit and vegetable consumption in middle schools. Allegrante JP, Barry MM, editors. Health Educ Behav. 2009;36(3):583-600. doi:10.1177/1090198108314619.

- Footnote 56

-

Engelen L, Bundy AC, Naughton G, et al. Increasing physical activity in young primary school children — it’s child’s play: a cluster randomised controlled trial. Prev Med. 2013;56(5):319-25. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2013.02.007.

- Footnote 57

-

Haerens L, Deforche B, Maes L, Cardon G, Stevens V, De Bourdeaudhuij I. Evaluation of a 2-year physical activity and healthy eating intervention in middle school children. Health Educ Res. 2006;21(6):911-21. doi:10.1093/her/cyl115.

- Footnote 58

-

McKenzie TL, Sallis JF, Prochaska JJ, Conway TL, Marshall SJ, Rosengard P. Evaluation of a two-year middle-school physical education intervention: M-SPAN: Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2004;36(8):1382-8. doi:10.1249/01.MSS.0000135792.20358.4D.

- Footnote 59

-

Mygind E. A comparison between children’s physical activity levels at school and learning in an outdoor environment. J Adventure Educ Outdoor Learn. 2007;7(2):161-76. doi:10.1080/14729670701717580.

- Footnote 60

-

Mygind E. A comparison of childrens’ statements about social relations and teaching in the classroom and in the outdoor environment. J Adventure Educ Outdoor Learn. 2009;9(2):151-69. doi:10.1080/14729670902860809.

- Footnote 61

-

Skala KA, Springer AE, Sharma SV, Hoelscher DM, Kelder SH. Environmental characteristics and student physical activity in PE class: findings from two large urban areas of Texas. J Phys Act Health. 2012;9(4):481-91. doi:10.1123/jpah.9.4.481.

- Footnote 62

-

Toftager M, Christiansen LB, Ersbøll AK, Kristensen PL, Due P, Troelsen J. Intervention effects on adolescent physical activity in the multicomponent SPACE study: a cluster randomized controlled trial. PLoS One. 2014;9(6):e99369. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0099369.

- Footnote 63

-

Waters E, Gibbs L, Tadic M, et al. Cluster randomised trial of a school-community child health promotion and obesity prevention intervention: findings from the evaluation of fun ‘n healthy in Moreland! BMC Public Health. 2017;18(1):92. doi:10.1186/s12889-017-4625-9.

- Footnote 64

-

Benjamin Neelon SE, Namenek Brouwer RJ, Østbye T, et al. A community-based intervention increases physical activity and reduces obesity in school-age children in North Carolina. Child Obes. 2015;11(3):297-303. doi:10.1089/chi.2014.0130.

- Footnote 65

-

D’Haese S, Van Dyck D, De Bourdeaudhuij I, Deforche B, Cardon G. Organizing “Play Streets” during school vacations can increase physical activity and decrease sedentary time in children. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2015;12(1):14. doi:10.1186/s12966-015-0171-y.

- Footnote 66

-

Elinder LS, Heinemans N, Hagberg J, Quetel A-K, Hagströmer M. A participatory and capacity-building approach to healthy eating and physical activity - SCIP-school: a 2-year controlled trial. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2012;9(1):145. doi:10.1186/1479-5868-9-145.

- Footnote 67

-

Fitzhugh EC, Bassett DR, Evans MF. Urban trails and physical activity. Am J Prev Med. 2010;39(3):259-62. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2010.05.010.

- Footnote 68

-

Goodman A, van Sluijs EM, Ogilvie D. Impact of offering cycle training in schools upon cycling behaviour: a natural experimental study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2016;13(1):34. doi:10.1186/s12966-016-0356-z.

- Footnote 69

-

Heelan KA, Abbey BM, Donnelly JE, Mayo MS, Welk GJ. Evaluation of a walking school bus for promoting physical activity in youth. J Phys Act Health. 2009;6(5):560-7. doi:10.1123/jpah.6.5.560.

- Footnote 70

-

Hoelscher D, Ory M, Dowdy D, et al. Effects of funding allocation for safe routes to school programs on active commuting to school and related behavioral, knowledge, and psychosocial outcomes: results from the Texas Childhood Obesity Prevention Policy Evaluation (T-COPPE) Study. Environ Behav. 2016;48(1):210-29. doi:10.1177/0013916515613541.

- Footnote 71

-

Mendoza JA, Levinger DD, Johnston BD. Pilot evaluation of a walking school bus program in a low-income, urban community. BMC Public Health. 2009;9(1):122. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-9-122.

- Footnote 72

-

Mendoza JA, Watson K, Baranowski T, Nicklas TA, Uscanga DK, Hanfling MJ. The walking school bus and children’s physical activity: a pilot cluster randomized controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2011;128(3):e537-44. doi:10.1542/peds.2010-3486.

- Footnote 73

-

Parker KM, Rice J, Gustat J, Ruley J, Spriggs A, Johnson C. Effect of bike lane infrastructure improvements on ridership in one New Orleans neighborhood. Ann Behav Med. 2013;45(suppl_1):S101-7. doi:10.1007/s12160-012-9440-z.

- Footnote 74

-

Stevens RB, Brown BB. Walkable new urban LEED_Neighborhood-Development (LEED-ND) community design and children’s physical activity: selection, environmental, or catalyst effects? Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2011;8(1):139. doi:10.1186/1479-5868-8-139.

- Footnote 75

-

Vanwolleghem G, D’Haese S, Van Dyck D, De Bourdeaudhuij I, Cardon G. Feasibility and effectiveness of drop-off spots to promote walking to school. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2014;11:136. doi:10.1186/s12966-014-0136-6.

- Footnote 76

-

Black IE, Menzel NN, Bungum TJ. The relationship among playground areas and physical activity levels in children. J Pediatr Health Care. 2015;29(2):156-68. doi:10.1016/j.pedhc.2014.10.001.

- Footnote 77

-

De Bourdeaudhuij I, Maes L, De Henauw S, et al. Evaluation of a computer-tailored physical activity intervention in adolescents in six European countries: the Activ-O-Meter in the HELENA intervention study. J Adolesc Health. 2010;46(5):458-66. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.10.006.

- Footnote 78

-

Ford PA, Perkins G, Swaine I. Effects of a 15-week accumulated brisk walking programme on the body composition of primary school children. J Sports Sci. 2013;31(2):114-22. doi:10.1080/02640414.2012.723816.

- Footnote 79

-

Haerens L, De Bourdeaudhuij I, Maes L, Cardon G, Deforche B. School-based randomized controlled trial of a physical activity intervention among adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2007;40(3):258-65. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2006.09.028.

- Footnote 80

-

Hunter RF, de Silva D, Reynolds V, Bird W, Fox KR. International inter-school competition to encourage children to walk to school: a mixed methods feasibility study. BMC Res Notes. 2015;8(1):19. doi:10.1186/s13104-014-0959-x.

- Footnote 81

-

Akpinar A. How is high school greenness related to students’ restoration and health? Urban For Urban Green. 2016;16:1-8. doi:10.1016/j.ufug.2016.01.007.

- Footnote 82

-

Hartig T, Evans GW, Jamner LD, Davis DS, Gärling T. Tracking restoration in natural and urban field settings. J Environ Psychol. 2003;23(2):109-23. doi:10.1016/S0272-4944(02)00109-3.

- Footnote 83

-

Roe J, Aspinall P. The emotional affordances of forest settings: an investigation in boys with extreme behavioural problems. Landsc Res. 2011;36(5):535-52. doi:10.1080/01426397.2010.543670.

- Footnote 84

-

Scholl KG, McAvoy LH, Rynders JE, Smith JG. The influence of an inclusive outdoor recreation experience on families that have a child with a disability. Ther Recreation J. 2003;37(1):38.

- Footnote 85

-

Waliczek TM, Bradley JC, Zajicek JM. The effect of school gardens on children’s interpersonal relationships and attitudes toward school. Horttechnology. 2001;11(3):466-8. doi:10.21273/HORTTECH.11.3.466.

- Footnote 86

-

Bundy AC, Luckett T, Naughton GA, et al. Playful interaction: occupational therapy for all children on the school playground. Am J Occup Ther. 2008;62(5):522-7. doi:10.5014/ajot.62.5.522.

- Footnote 87

-

Gallerani DG, Besenyi GM, Wilhelm Stanis SA, Kaczynski AT. “We actually care and we want to make the parks better”: A qualitative study of youth experiences and perceptions after conducting park audits. Prev Med. 2017;95:S109-14. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.08.043.

- Footnote 88

-

Haug E, Torsheim T, Samdal O. Physical environmental characteristics and individual interests as correlates of physical activity in Norwegian secondary schools: the health behaviour in school-aged children study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2008;5(1):47. doi:10.1186/1479-5868-5-47.

- Footnote 89

-

Holmes RM, Pellegrini AD, Schmidt SL. The effects of different recess timing regimens on preschoolers’ classroom attention. Early Child Dev Care. 2006;176(7):735-43. doi:10.1080/03004430500207179.

- Footnote 90

-

Jeanes R, Magee J. ‘Can we play on the swings and roundabouts?’: Creating inclusive play spaces for disabled young people and their families. Leis Stud. 2012;31(2):193-210. doi:10.1080/02614367.2011.589864.

- Footnote 91

-

Cosco NG, Moore RC, Smith WR. Childcare outdoor renovation as a built environment health promotion strategy: evaluating the Preventing Obesity by Design intervention. Am J Health Promot. 2014;28(3 Suppl):S27-32. doi:10.4278/ajhp.130430-QUAN-208.

- Footnote 92

-

Gutierrez CM, Slagle D, Figueras K, Anon A, Huggins AC, Hotz G. Crossing guard presence: impact on active transportation and injury prevention. J Transp Health. 2014;1(2):116-23. doi:10.1016/j.jth.2014.01.005.

- Footnote 93

-

Tester J, Baker R. Making the playfields even: evaluating the impact of an environmental intervention on park use and physical activity. Prev Med. 2009;48(4):316-20. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2009.01.010.

- Footnote 94

-

Dudley DA, Okely AD, Pearson P, Peat J. Engaging adolescent girls from linguistically diverse and low income backgrounds in school sport: a pilot randomised controlled trial. J Sci Med Sport. 2010;13(2):217-24. doi:10.1016/j.jsams.2009.04.008.

- Footnote 95

-

Howe CA, Freedson PS, Alhassan S, Feldman HA, Osganian SK. A recess intervention to promote moderate-to-vigorous physical activity: structured recess intervention. Pediatr Obes. 2012;7(1):82-8. doi:10.1111/j.2047-6310.2011.00007.x.

- Footnote 96

-

Statistics Canada. Canadians and nature: parks and green spaces, 2013 [Internet]. Ottawa (ON): Statistics Canada; 2015 [cited 2019 Aug 2]. (Enviro Fact Sheet). Report No.: 16-508-X. Available from: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/16-508-x/16-508-x2015002-eng.htm

- Footnote 97

-

Brussoni M, Gibbons R, Gray C, et al. What is the relationship between risky outdoor play and health in children? A systematic review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2015;12(6):6423-54. doi:10.3390/ijerph120606423.

- Footnote 98

-

Coombes E, Jones A. Gamification of active travel to school: a pilot evaluation of the beat the street physical activity intervention. Health Place. 2016;39:62-9. doi:10.1016/j.healthplace.2016.03.001.

- Footnote 99

-

Wray AJ, Olstad DO, Minaker LM. Smart prevention: a new approach to primary and secondary cancer prevention in smart and connected communities. Cities. 2018;(79):53-69. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2018.02.022.

- Footnote 100

-

Hunter RF, Cleland C, Cleary A, et al. Environmental, health, wellbeing, social and equity effects of urban green space interventions: a meta-narrative evidence synthesis. Environ Int. 2019;130:104923. doi:10.1016/j.envint.2019.104923.

- Footnote 101

-

Heath GW, Bilderback J. Grow healthy together: effects of policy and environmental interventions on physical activity among urban children and youth. J Phys Act Health. 2019;16:172-6. doi:10.1123/jpah.2018-0026.

- Footnote 102

-

Arunkumar K, Bowman DD, Coen SE, et al. Conceptualizing youth participation in children’s health research: insights from a youth-driven process for developing a youth advisory council. Children. 2019;6(1):3. doi:10.3390/children6010003.

- Footnote 103

-

Statistics Canada. A portrait of Canadian youth: March 2019 updates [Internet]. Ottawa (ON): Government of Canada; 2019 May [cited 2019 Aug 21]. Report No.: 11-631-X. Available from: https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/11-631-x/11-631-x2019003-eng.htm