At-a-glance – Trends in emergency department visits for acetaminophen-related poisonings: 2011–2019

Health Promotion and Chronic Disease Prevention in Canada

Jaskiran Kaur, MSc; Steven R. McFaull, MSc; Felix Bang, MPH

https://doi.org/10.24095/hpcdp.40.4.05

Author references

Public Health Agency of Canada, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada

Correspondence: Jaskiran Kaur, Centre for Surveillance and Applied Research, Public Health Agency of Canada, Rm 629A4, 785 Carling Avenue, Ottawa, ON K1A 0K9; Tel: 613-668-7254; Email: jaskiran.kaur@canada.ca

Abstract

We examined trends in emergency department (ED) presentation rates for acetaminophen-related poisonings across Canada. A total of 27 123 cases of poisoning were seen in the electronic Canadian Hospitals Injury Reporting and Prevention Program (eCHIRPP) sentinel sites between April 2011 and February 2019; of these, 13.7% were related to acetaminophen use. A significant decreasing trend for both sexes was observed for unintentional poisonings (males: −10.3%; females: −8.0%). For intentional poisonings, there was a significant decrease among females only (−5.9%). Females have consistently displayed higher rates of ED presentations for both unintentional and intentional poisoning.

Keywords: acetaminophen, Tylenol, paracetamol, poisoning, CHIRPP

Highlights

- A total of 27 123 cases of poisoning were captured in the eCHIRPP database, of which 3721 cases (13.7%) were acetaminophen related.

- About 50.3% of the poisonings were unintentional, 48.6% were intentional and 1.1% were of undetermined intent.

- There was a significant decreasing trend in acetaminophen poisonings, among all unintentional poisonings, for both males (−10.3%) and females (−8.0%).

- Among all intentional poisonings, there was a significant decrease for acetaminophen poisonings among females (−5.9%) but not among males.

- Compared to males, females had consistently higher rates of emergency department presentations for both unintentional and intentional acetaminophen-related poisonings.

Introduction

Acetaminophen, also known as paracetamol, APAPFootnote 1 or Tylenol, is a common medication used for reducing pain and fever. It is widely available on the market in many over-the-counter and prescription medicines. It can be found as an individual product containing acetaminophen only (e.g. Tylenol); as over-the-counter cold remedies (e.g. DayQuil/NyQuil); or in combination with an opiate (e.g. Percocet). Due to its widespread availability, acetaminophen is a common cause of both unintentional and intentional ingestions.

Research from Canada and the United States has shown that, if taken in excessive amounts, acetaminophen is the leading cause of acute liver failure.Footnote 1Footnote 2Footnote 3Footnote 4 Approximately 4500 hospitalizations due to acetaminophen overdose are reported each year in Canada. About 6% of patients hospitalized for overdose develop liver conditions including acute liver failure that may lead to death.Footnote 2

The purpose of this brief report is to describe the pattern of cases of acetaminophen ingestions reporting to Canadian emergency departments.

Methods

The Canadian Hospitals Injury Reporting and Prevention Program (CHIRPP)Footnote 5 is a sentinel injury and poisoning surveillance system administered by the Public Health Agency of Canada. CHIRPP collects data from emergency departments (ED) in 11 pediatric and 8 general hospitals across Canada (19 sites altogether). We searched the electronic (eCHIRPP) database for ED visit records for acetaminophen-related poisonings between 1 April 2011 and 23 February 2019 (N = 1 037 843). Cases were included if the following criteria were met:

- Description of injury

- The direct cause of injury, or contributing factors, was coded as “Acetaminophen, INCL Tylenol – alone” (eCHIRPP code 753F) or “Acetaminophen, INCL Tylenol – with other substance, INCL Tylenol with codeine” (eCHIRPP code 754F) or “Allergy/cold/cough medications, INCL containing ASA or acetaminophen” (eCHIRPP code 755F), or

- The narrative text included the following French and English key words/strings: “ACETA,” “ACÉTA,” “TYLENOL,” “TYLÉN,” “PARACETA,” “PARACÉTA”

- Nature of injury and external cause.

- The nature of injury code indicated poisoning or toxic effect (eCHIRPP code 50NI) or the external cause contained the code 301EC (301EC: Poisoning INCL street and prescription drugs, alcohol, solvents, gases, corrosives and pesticides/fertilizers).

In instances where only one of the three criteria was met, an analyst adjudicated the case manually. Cases (n = 98) were excluded from the present analysis when it was uncertain which drug had been taken.

Time trends for 2011 to 2018 were analyzed using Joinpoint Regression Program version 4.6.0.0 (SEERStat, NCI, Bethesda, MD, USA), which outputs the average annual per cent change (AAPC) or the annual per cent change (APC).Footnote 6 Data for 2019 are incomplete and therefore excluded from the trends analysis. All statistical analyses were performed using Enterprise Guide, version 5.1 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

From 1 April 2011 to 23 February 2019, a total of 27 123 cases of poisoning were seen at the eCHIRPP sentinel sites, of which 3721 (13.7%) cases were related to acetaminophen. This represented 13 719/100 000 eCHIRPP cases of all types of poisoning. About 50.3% of the poisonings were classified as unintentional, while 48.6% were intentional and 1.1% of the cases were of undetermined intent.

The median age was 14.0 years (interquartile range [IQR]: 2.0–16.0). Females accounted for two-thirds (n = 2513; 67.5%) of the ED visits for acetaminophen-related poisoning, representing 19.9% of all female poisoning cases from 2001 to 2019. Those aged 15–19 years accounted for one-third (35%) of acetaminophen-related poisoning cases in eCHIRPP, while those aged 2–4 years accounted for 22.9% of acetaminophen-related poisoning cases.

Acetaminophen-related intentional poisonings were significantly higher in those aged 15–19 years (28.2%; p < .0001) and in females (42.2%; p < .0001). The majority of the cases (n = 2597; 69.8%) involved products containing acetaminophen alone (e.g. Tylenol), while 15.9% (n = 590) involved acetaminophen combined with other substances (e.g. Tylenol with codeine) and 14.4% (n = 534) involved allergy/cold/cough medication containing acetaminophen. Acetaminophen-related intentional poisonings predominated in both sexes from the age of 10 years and older.

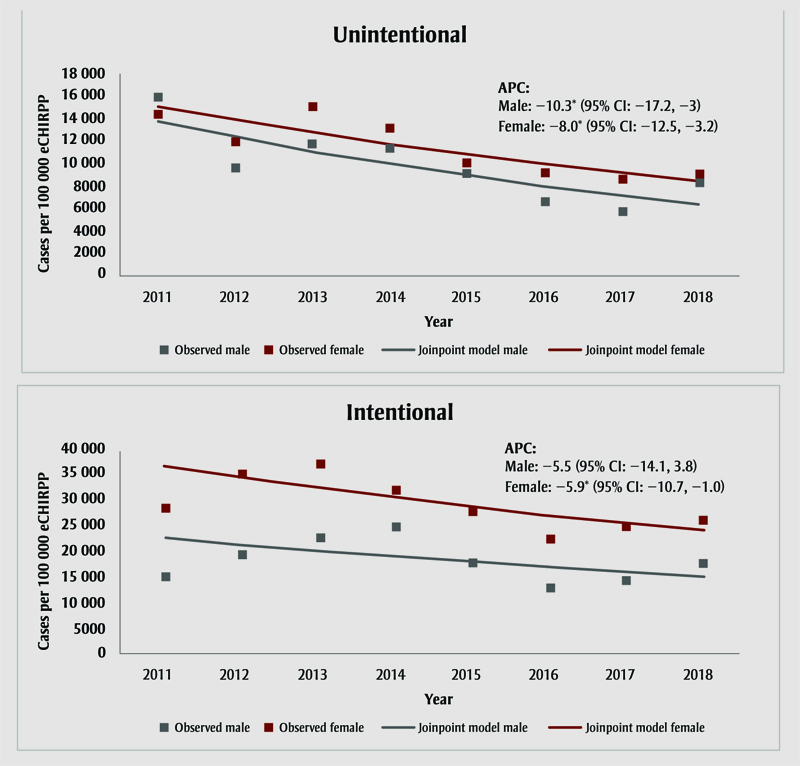

Figure 1 shows the results of the Joinpoint analysis by intent and sex from 2011 to 2018 (data for 2019 are incomplete and therefore excluded from the trends analysis). No inflection points were found and overall trends were represented by APC. As a proportion of all unintentional poisonings, there was a significant decreasing trend for both males (−10.3%; 95% CI: −17.2 to −3.0) and females (−8.0%; 95% CI: −12.5 to −3.2). For the intentional acetaminophen poisonings, there was a significant decrease among females (−5.9%; 95% CI: −10.7 to −1.0) but not males.

Figure 1. Evolution of normalizedFootnote a emergency department presentation rates associated with intentional and unintentional acetaminophen poisonings, by intent and sex, eCHIRPP, 2001–2018Footnote b

Figure 1 - Text Equivalent

| Unintentional | Intentional | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year | Male Cases per 100 000 eCHIRPP | Female Cases per 100 000 eCHIRPP | Year | Male Cases per 100 000 eCHIRPP | Female Cases per 100 000 eCHIRPP |

| 2011 | 15973 | 14439 | 2011 | 15054 | 28185 |

| 2012 | 9680 | 12008 | 2012 | 19380 | 35147 |

| 2013 | 11753 | 15087 | 2013 | 22378 | 36976 |

| 2014 | 11470 | 13257 | 2014 | 24786 | 31825 |

| 2015 | 9198 | 10156 | 2015 | 17801 | 27754 |

| 2016 | 6620 | 9204 | 2016 | 12829 | 22434 |

| 2017 | 5762 | 8625 | 2017 | 14504 | 24978 |

| 2018 | 8282 | 9081 | 2018 | 17757 | 26154 |

| Annual Percent Change (APC) | −10.3%Footnote * (95% CI: −17.2, −3) | −8.0%Footnote * (95% CI: −12.5, −3.2) | Annual Percent Change (APC) | −5.5% (95% CI: −14.1, 3.8) | −5.9%Footnote * (95% CI: −10.7, −1) |

|

|||||

Abbreviations: APC, annual per cent change; CI, confidence interval; eCHIRPP, electronic Canadian Hospitals Injury Reporting and Prevention Program.

Note: Undetermined intent was excluded from the analysis due to the low number of cases.

- Footnote a

-

Proportion of all eCHIRPP cases for a given year (× 100 000).

- Footnote b

-

Because data are incomplete for 2019, only 2011 to 2018 data were included in the Joinpoint analysis.

* Indicates that APC is significantly different from zero at the α = 0.05 level.

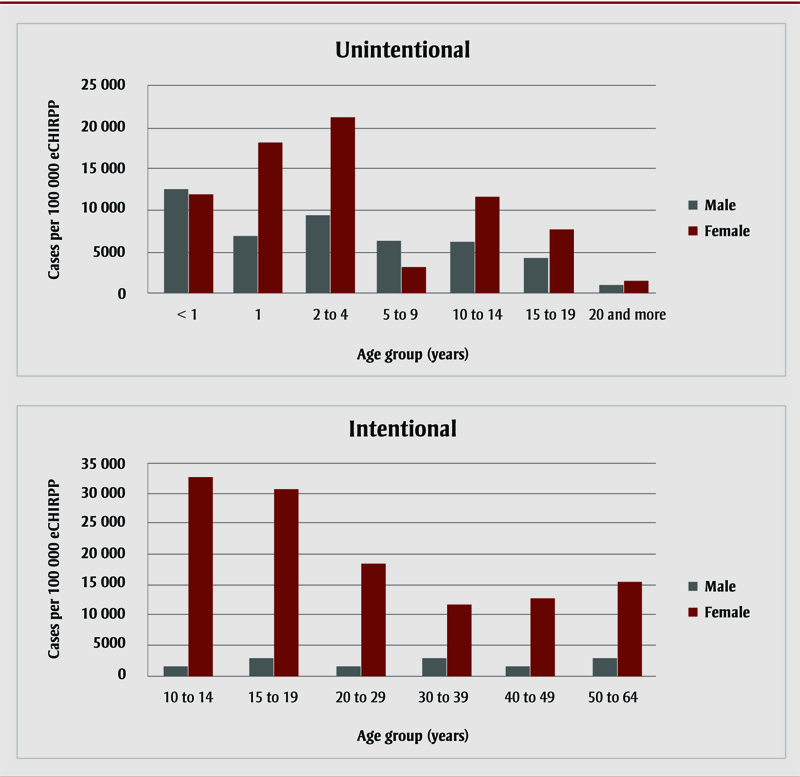

Figure 2 summarizes the results for both sexes by age and by intent. Females were older, with a median age of 14.0 years (IQR: 9.0–16.0) compared to a median age of 3.0 years for males (IQR: 2.0–15.0). Females have consistently displayed higher rates of ED presentations for both unintentional and intentional acetaminophen-related poisoning than males. At almost six times that of males in the same age group, females aged 10–19 years have a disproportionately high rate of unintentional poisoning (n = 1390; 31 512 per 100 000 eCHIRPP cases).

Figure 2. NormalizedFootnote a distribution of emergency department presentations for acetaminophen-related poisonings, by age and sex, eCHIRPP, 2001–2019

Figure 2 - Text Equivalent

| Unintentional | Intentional | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age group (years) | Male cases per 100 000 eCHIRPP |

Female cases per 100 000 eCHIRPP |

Age group (years) | Male cases per 100 000 eCHIRPP |

Female cases per 100 000 eCHIRPP |

| < 1 | 12536 | 11921 | 10-14 | 1350 | 32829 |

| 1 | 6877 | 18199 | 15-19 | 2720 | 30772 |

| 2-4 | 9394 | 21217 | 20-29 | 1539 | 18560 |

| 5-9 | 6076 | 3172 | 30-39 | 2886 | 11659 |

| 10-14 | 6139 | 11645 | 40-49 | 1681 | 12821 |

| 15-19 | 4212 | 7685 | 50-64 | 2576 | 15271 |

| ≥ 20 | 921 | 1456 | |||

Abbreviation: eCHIRPP, electronic Canadian Hospitals Injury Reporting and Prevention Program.

Note: Due to non-stable data, the <10-year and >65-year age groups were not included in the analysis for intentional poisoning.

- Footnote a

-

Proportion of all eCHIRPP cases for a given age group (× 100 000).

The number of patients presenting to EDs for acetaminophen-related poisoning decreased in older age groups (≥ 20 years) for both sexes.

Discussion

From 2011 to 2019, 3721 acetaminophen-related poisoning cases presented to EDs across Canada; these accounted for 13.7% of all poisoning cases in eCHIRPP. Consistent with other studies,Footnote 7Footnote 8 there were far more acetaminophen-related poisoning cases among females than males. This is consistent with data that show poisoning to be a primary method of suicide among females.Footnote 9Footnote 10

Overall, ED presentations due to acetaminophen overdose appeared to decline between 2011 and 2018. As a proportion of all unintentional poisonings, a significant decreasing trend was observed for both males and females; in the case of intentional acetaminophen poisonings, a significant decrease was noted among females but not males.

We found that children aged 0–4 years had more acetaminophen-related accidental poisonings compared to other age groups. Accidental poisonings predominated in females in all ages groups except among neonates and infants aged less than one year. It is possible that these accidental overdoses were caused by miscalculation or incorrect measurement of doses by parents/guardians. On the other hand, intentional poisoning by acetaminophen was more common among adolescents aged 10–19 years, with higher prevalence among females. Studies have shown that self-poisoning is the most common method of attempting suicide among adolescentsFootnote 11Footnote 12 and that over-the counter medications are the most commonly used means.Footnote 13 Acetaminophen-related mortality is higher in countries where unlimited quantities can be obtained.Footnote 14 However, it is important to note that the use of acetaminophen for self-poisoning is not merely related to its accessibility but also to its popularity and the availability of other methods.

In 2009, Health Canada finalized the Acetaminophen Labelling Standard, which led to the inclusion of stronger warnings on the risk of liver damage.Footnote 15 The labelling standard was revised in 2016 based on the outcome of Health Canada’s 2014 review.Footnote 16 These recommendations include, but are not limited to, a stronger warning to do with concomitant alcohol consumption; more safety information about the product’s contents on the label; and a drug facts table providing instructions and warnings in an easy-to-read format. A dosing device has also been included to help parents/caregivers administer children’s liquid acetaminophen products.

All acetaminophen products have been expected to comply with the new labelling standard since March 2018. As such, the improved labelling standard may be have been implemented too recently to have had an obvious effect. Consequently, ongoing surveillance of acetaminophen-related poisoning is necessary to assess the effect of the improved labelling standard and to support the implementation of safety measures to reduce the risk of harm from this regularly used and widely accessible medication.

Strengths and limitations

This study provides the most up-to-date analysis of pan-Canadian trends in ED presentations of acetaminophen poisoning. However, our sample was not fully representative of the Canadian population as only some hospitals participate in the CHIRPP. Because CHIRPP sites are mostly pediatric hospitals located in major cities, older teens, adults, some Indigenous peoples and rural inhabitants are underrepresented.

While eCHIRPP captures cases who are dead-on-arrival, fatalities are underrepresented because ED data do not capture those who died before they could be taken to hospital or those who died after being admitted. Patients who bypass the ED registration desk for immediate treatment may also not be captured. The same is true of those who do not complete the Injury/Poisoning Reporting form.

Finally, the narratives are largely dependent on patients/caregivers as they are based solely on the information they provide at the time of the injury. Patients who do not have good knowledge of drugs may confuse acetaminophen with other drugs. Further, the intent of the poisoning could also be potentially flawed from omissions as patients may not want to report this due to the sensitive nature of the topic.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Melinda Tiv and James Cheesman for their valuable input on the coding and classification rules of acetaminophen-related poisoning cases. The authors would also like to thank Aimée Campeau for reviewing the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Authors’ contributions and statement

JK conducted the data analysis and wrote the paper. FB performed Joinpoint analysis. SRM and FB helped revise the paper.

All authors are employees of the Public Health Agency of Canada. However, the content and views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Government of Canada.

References

- Footnote 1

-

Lee MW. Acetaminophen (APAP) hepatoxicity – Isn’t it time for APAP to go away? J Hepatol. 2017;67(6):1324-31. doi:10.1016/j.jhep.2017.07.005.

- Footnote 2

-

Acetaminophen [Internet]. Ottawa (ON): Government of Canada; 2016 [cited 2019 April 10]. Available from: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/drugs-medical-devices/acetaminophen.html

- Footnote 3

-

Yoon E, Babar A, Choudhary M, Kutner M, Pyrsopoulos N. Acetaminophen-induced hepatotoxicity: a comprehensive update. J Clin Transl Hepatol. 2016;4(2):131-42. doi:10.14218/JCTH.2015.00052.

- Footnote 4

-

Clark R, Fisher JE, Sketis IS, Johnston GM. Population prevalence of high dose paracetamol in dispensed paracetamol/opiod prescription combinations: an observational study. BMC Clin Pharmacol. 2012;12(11). doi:10.1186/1472-6904-12-11.

- Footnote 5

-

Crain J, McFaull S, Thompson W, et al. The Canadian Hospital Injury Reporting and Prevention Program: a dynamic and innovative injury surveillance system. Health Promot Chronic Dis Prev Can. 2016;36(6):112-7. doi:10.24095/hpcdp.36.6.02.

- Footnote 6

-

Statistical Methodology and Applications Branch Surveillance Research Program, National Cancer Institute. Joinpoint regression program, version 4.6.0.0 – 2018 Apr. Bethesda (MD): National Cancer Institute; 2018.

- Footnote 7

-

Myers RP, Li B, Shaheen AA, et al. Emergency department visits for acetaminophen overdose: a Canadian population-based epidemiologic study (1997-2002). CJEM. 2007;9(4):267-74.

- Footnote 8

-

Major MJ, Zhou HE, Wong HL, et al. Trends in rates of acetaminophen-related adverse events in the United States. Pharmacoepidemiol Druf Saf. 2016;25(5):590-8. doi:10.1002/pds.3906.

- Footnote 9

-

Skinner R, McFaull S, Rhodes AE, Bowes M, Rockett IR. Suicide in Canada: is poisoning misclassification an issue? Can J Psychiat. 2016;61(7):405-12. doi:10.1177/0706743716639918.

- Footnote 10

-

Skinner R, McFaull S, Draca J, et al. Suicide and self-inflicted injury hospitalizations in Canada (1979 to 2014/15). Health Promot Chronic Dis Prev Can. 2016;36(11):243-51.

- Footnote 11

-

Geulayov G, Casey D, McDonald KC, et al. Incidence of suicide, hospital-presenting non-fatal self-harm, and community-occurring non-fatal self-harm in adolescents in England (the iceberg model of self-harm): a retrospective study. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5:167-74. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(17)30478-9.

- Footnote 12

-

Plemmons G, Hall M, Doupnik S, et al. Hospitalization for suicide ideation or attempt: 2008-2015. Pediatrics. 2018;141(6):e20172426. doi:10.1542/peds.2017-2426.

- Footnote 13

-

Spiller HA, Ackerman JP, Smith GA, et al. Suicide attempts by self-poisoning in the United States among 10–25 year olds from 2000 to 2018: substances used, temporal changes and demographics. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2019:1-12. doi:10.1080/15563650.2019.1665182.

- Footnote 14

-

Gunnell D, Murray V, Hawton K. Use of paracetamol (acetaminophen) for suicide and nonfatal poisoning: worldwide patterns of use and misuse. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2000;30(4):313-26.

- Footnote 15

-

Health Canada, Health Products and Food Branch, Therapeutic Products Directorate. Notice: Release of final guidance document: acetaminophen labelling standard. Ottawa (ON): Health Canada; 2009 Oct 28 [cited 2019 Oct 07]. Available from http://ashleylouisecampbell.com/web_documents/label_stand_guide_ld-eng.pdf

- Footnote 16

-

Health Canada, Health Products and Food Branch, Natural and Non-prescription Health Products Directorate. Notice: Revised guidance document: acetaminophen labelling standard. Ottawa (ON): Health Canada; 2016 Sep 15 [cited 2019 Oct 07]. Available from: http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/dhp-mps/alt_formats/pdf/prodpharma/applic-demande/guide-ld/label_stand_guide_ld-2016-eng.pdf