Evidence synthesis – Evidence-informed interventions and best practices for supporting women experiencing or at risk of homelessness: a scoping review with gender and equity analysis

Health Promotion and Chronic Disease Prevention in Canada

Anne Andermann, MD, DPhil, CCFP, FRCPCAuthor reference footnote 1Author reference footnote 2Author reference footnote 3; Sebastian Mott, MSWAuthor reference footnote 3; Christine M. Mathew, MScAuthor reference footnote 4; Claire Kendall, MD, CCFPAuthor reference footnote 4Author reference footnote 5; Oreen Mendonca, BScAuthor reference footnote 4; Dawnmarie HarriottAuthor reference footnote 6; Andrew McLellan, MScNAuthor reference footnote 5Author reference footnote 7; Alison Riddle, MScAuthor reference footnote 8; Ammar Saad, MScAuthor reference footnote 4Author reference footnote 9; Warda Iqbal, MDAuthor reference footnote 9; Olivia Magwood, MPHAuthor reference footnote 4; Kevin Pottie, MD, CCFPAuthor reference footnote 4Author reference footnote 5

https://doi.org/10.24095/hpcdp.41.1.01

This article has been peer reviewed.

Correspondence: Dr. Anne Andermann, Associate Professor, Family Medicine Centre, St. Mary’s Hospital, 3830 Lacombe, Montréal, QC H3T 1M5; Email: anne.andermann@mail.mcgill.ca

Abstract

Introduction: While much of the literature on homelessness is centred on the experience of men, women make up over one-quarter of Canada’s homeless population. Research has shown that women experiencing homelessness are often hidden (i.e. provisionally housed) and have different pathways into homelessness and different needs as compared to men. The objective of this research is to identify evidence-based interventions and best practices to better support women experiencing or at risk of homelessness.

Methods: We conducted a scoping review with a gender and equity analysis. This involved searching MEDLINE, CINAHL, PsycINFO and other databases for systematic reviews and randomized trials, supplementing our search through reference scanning and grey literature, followed by a qualitative synthesis of the evidence that examined gender and equity considerations.

Results: Of the 4102 articles identified on homelessness interventions, only 4 systematic reviews and 9 randomized trials were exclusively conducted on women or published disaggregated data enabling a gender analysis. Interventions with the strongest evidence included post-shelter advocacy counselling for women experiencing homelessness due to intimate partner violence, as well as case management and permanent housing subsidies (e.g. tenant-based rental assistance vouchers), which were shown to reduce homelessness, food insecurity, exposure to violence and psychosocial distress, as well as promote school stability and child well-being.

Conclusion: Much of the evidence on interventions to better support women experiencing homelessness focusses on those accessing domestic violence or family shelters. Since many more women are experiencing or at risk of hidden homelessness, population-based strategies are also needed to reduce gender inequity and exposure to violence, which are among the main structural drivers of homelessness among women.

Keywords: scoping review, women, shelters, hidden homelessness, violence, equity, gender, housing, intervention research, evidence-informed policy

Highlights

- Women make up over one-quarter of Canada’s documented homeless population, but many more are “hidden homeless” who remain uncounted, and their pathways into homelessness and their support needs are often different than those of men.

- A number of evidence-informed interventions are available to better support women experiencing or at risk of homelessness, including post-shelter advocacy interventions, permanent housing subsidies (e.g. tenant based rental vouchers) and case management or other forms of social support.

- These interventions reduce homelessness, food insecurity, exposure to intimate partner violence and psychosocial distress, leading to greater self-esteem and quality of life for women, as well as fewer child separations and foster care placements, and significant improvements in school stability and child well-being.

- Widespread implementation of evidence-informed interventions is needed, both during the COVID-19 pandemic and afterward to better support women who are experiencing or at risk of homelessness, as well as to create the structural changes required to redress persistent gender inequities and eliminate violence.

- Population-wide measures to prevent women from experiencing homelessness in the first place include improving access to child care and stable employment, flexible work conditions, reducing wage gaps, formalizing and remunerating the work of informal family caregivers (most often done by women), changing social norms that tolerate and perpetuate intimate partner violence, and ensuring that women control a fair share of household wealth and decision-making.

Introduction

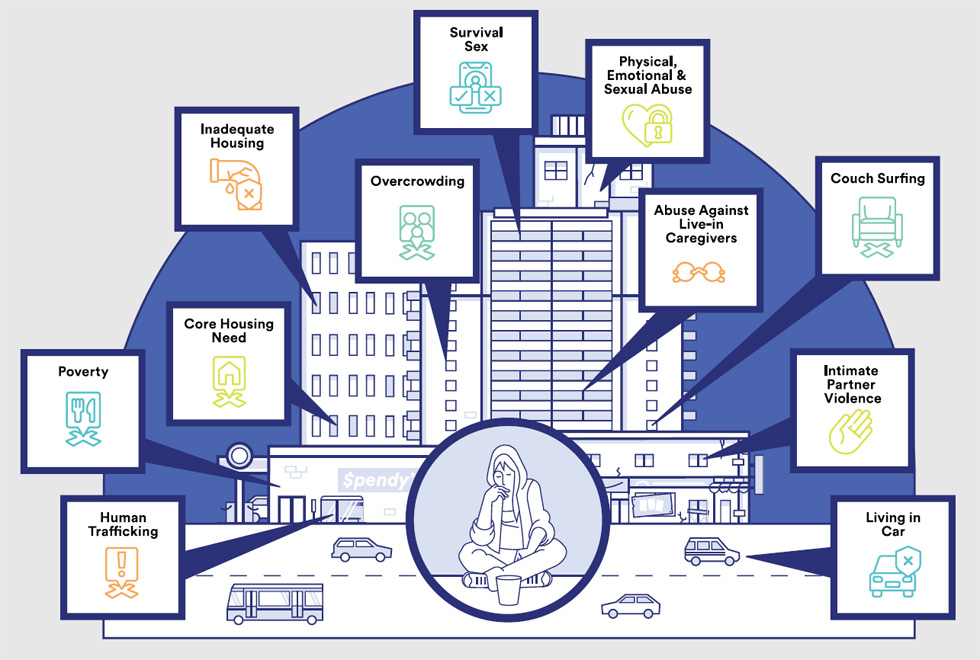

Women make up approximately 27.3% of the Canadian homeless population.Footnote 1 However, this is a major underestimate of the actual number experiencing and at risk of homelessness. According to the Canadian definition of homelessness,Footnote 2 women are considered “emergency sheltered” if they are staying temporarily at shelters, including those for victims of family violence, which is a major driver of homelessness for women and children across CanadaFootnote 3 and globally.Footnote 4 However, more often, women (especially those with children) attempt to remain off the streets and out of shelters becoming “hidden homeless,” moving from place to place and “couch surfing” at the homes of friends or family. These women are considered “provisionally accommodated,” defined as someone who is “homeless and without permanent shelter who accesses temporary accommodation.”Footnote 2,p3 This umbrella term also includes institutionalized persons who might transition into homelessness after their release in the absence of sufficient discharge planning and follow-up (e.g. girls “aging out” of foster care or incarcerated women departing from correctional services); recently arrived immigrants and refugees in temporary resettlement (e.g. multiple families sharing an overcrowded dwelling); women with cognitive or psychological disabilities; and many other groups.Footnote 2 Women may be forced to engage in “survival sex,” are more likely to be exploited by human trafficking, and may even be living in their car in an attempt to stay safe, but they are often hidden behind closed doors (Figure 1), and therefore many remain uncounted.Footnote 5

Figure 1. Different forms of hidden homelessness among women, girls and gender-diverse persons experiencing homelessness

Text description: Figure 1

Figure 1. Different forms of hidden homelessness among women, girls and gender-diverse persons experiencing homelessness

This figure illustrates the different forms of hidden homelessness among women, girls and gender-diverse persons experiencing homelessness: Human trafficking; Poverty; Core housing needs; Inadequate housing; Overcrowding; Survival sex; Physical, emotional and sexual abuse; Abuse against live-in caregivers; Couch surfing; Intimate partner violence; and Living in a car.

An analysis of Canadian census data from 2014 has shown that over 1 million women reported having experienced hidden homelessness at some point in their life, which was often associated with a history of adverse childhood experiences, weaker social networks and gender-diverse backgrounds.Footnote 6 In addition to these women experiencing various forms of homelessness, there is an even greater number who are considered “precariously housed,”Footnote 2 meaning they are living in homes in “core housing need”Footnote 7 that require major repairs (“inadequate housing”), have an insufficient number of rooms to accommodate the people living there (“unsuitable housing”), and cost more than 30% of the household’s before-tax income (“unaffordable housing”). These women are therefore considered at imminent risk of homelessness in the event of a crisis (e.g. escalating violence, marital separation, eviction).Footnote 2

It has been shown that women have different pathways into homelessness, as well as different support needs, than men.Footnote 8 Women are more likely to experience homelessness due to domestic violence and a lack of social support. Leaving a violent relationship can be considerably more difficult if a victim shares children, a home and resources with their partner.Footnote 9 On average, one woman in Canada is killed by her intimate partner every 5 days.Footnote 10 Over 40 000 women and their 27 000 children resort to living in shelters across Canada each year, with approximately 3600 women and their 3100 children staying in shelter facilities on any given night.Footnote 11 Shelters are a means to escape emotional or psychological abuse (89%), physical abuse (73%), financial abuse (51%), sexual abuse (33%) and even human trafficking (3%) and forced marriage (2%).Footnote 11 Women in rural and remote areas, and particularly Indigenous women,Footnote 12 experience the highest overall rates of intimate partner violence (IPV).Footnote 13 Those with dependent children often try to avoid shelters until all other options are exhausted (i.e. staying with family and friends).Footnote 14 Therefore, exploring interventions that are effective in addressing homelessness requires a gender analysis, since what works for men does not necessarily work for women.Footnote 15Footnote 16

Intimate partner violence, poverty and homelessness among women are inter-linked and a major challenge and hidden crisis in Canada that costs taxpayers an estimated CAD 7 billion each year. The greatest losses are incurred by the women themselves, including the harms of witnessing violence and lost opportunities for their children.Footnote 17 Since the COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in extended lockdowns for months at a time across Canada, the situation for women at risk of or experiencing homelessness is all the more urgent.Footnote 18

As part of a larger initiative to develop clinical practice guidelines for supporting persons experiencing homelessness in Canada,Footnote 19Footnote 20 women experiencing homelessness were considered among the priority populations identified using a modified Delphi consensus process.Footnote 21 The aim of this article is to examine evidence-based interventions and best practices specifically aimed at supporting women experiencing and at risk of homelessness, to enable a more effective approach that is tailored and adapted to the specific needs of women.

Methods

We conducted a scoping review of published primary and secondary research studies using standard methodsFootnote 22 with a gender analysis to understand what interventions are effective for women experiencing homelessness and more responsive to their specific needs,Footnote 23 as well as an equity analysis to assess the potential for reducing inequities in multiple domains.Footnote 24

Search strategy and selection criteria

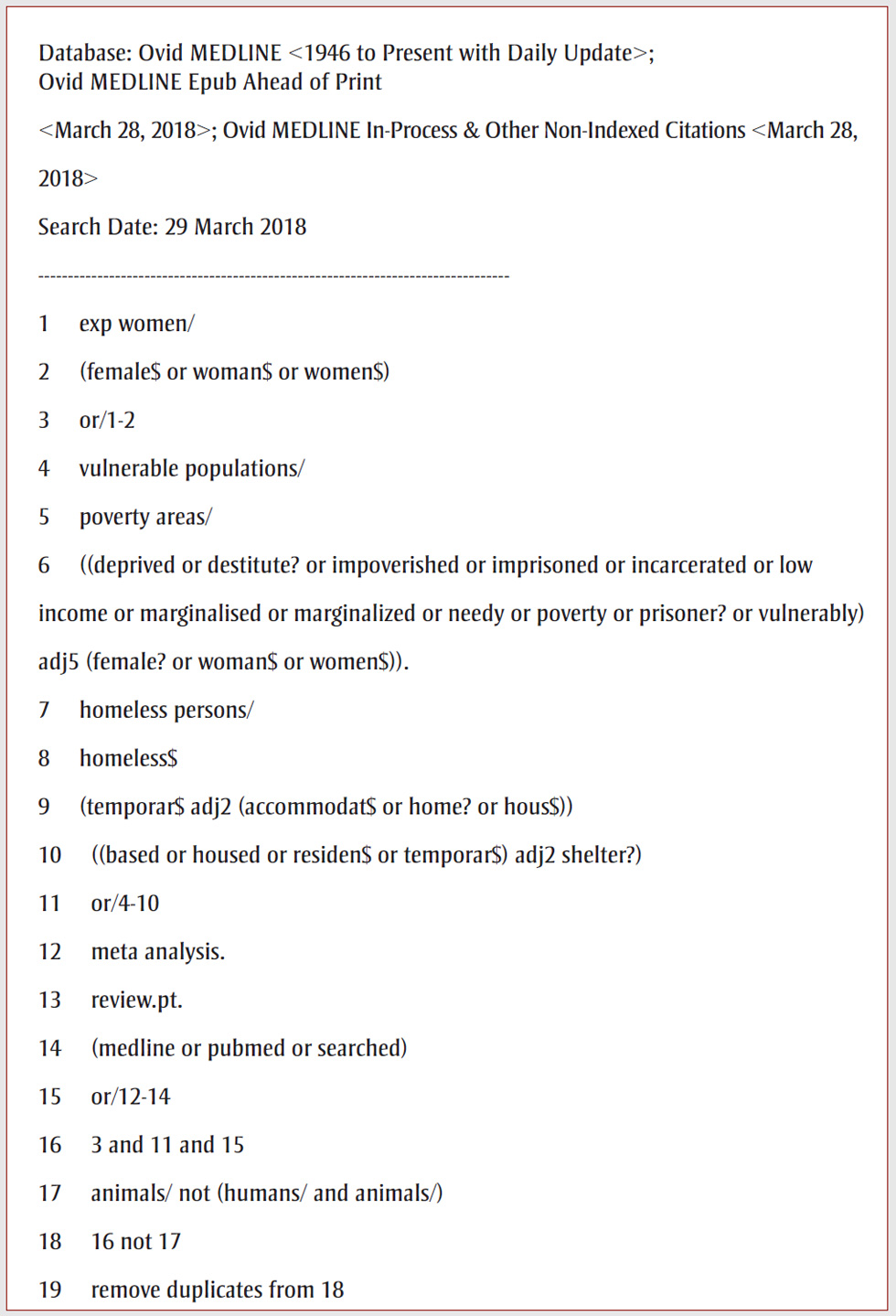

A systematic search was carried out with the aid of an information scientist using relevant keywords and Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) terms for published randomized trials and systematic reviews. Keywords included “women”, “vulnerable populations”, “homeless” and “marginalized.” Figure 2 shows the MEDLINE search strategy with a complete list of key words. Databases searched were MEDLINE, CINAHL, PsycINFO, Cochrane CENTRAL, PROSPERO and DARE from database inception to 28 March 2018. Title and abstract screening was done by two reviewers independently, in duplicate. All randomized controlled trials and systematic reviews exclusively focussed on women (aged 18 years and over) experiencing homelessness were selected for full-text review. However, since the availability of intervention research focussed on women experiencing homelessness is limited, we also included equity-relevant, mixed population studies for which disaggregated outcomes data were available to assess the intervention’s impact on women (and their offspring, where applicable).Footnote 25 There was no restriction for types of intervention(s) or outcomes studied (as long as housing status was one of these outcomes). Searches were conducted using English search terms, and articles were retrieved regardless of language of publication. To ensure relevance to the Canadian context, only articles from high-income countries as defined by the World Bank were retained. Full-text review was done independently, and 20% of a random selection of excluded studies was corroborated by a second reviewer. All inter-reviewer discrepancies during both phases of screening were resolved through discussion or by a third reviewer.

Figure 2. Search strategy for systematic review of evidence-informed interventions and best practices for supporting women experiencing or at risk of homelessness

Text description: Figure 2

Figure 2. Search strategy for systematic review of evidence-informed interventions and best practices for supporting women experiencing or at risk of homelessness

Database: Ovid MEDLINE <1946 to Present with Daily Update>; Ovid MEDLINE Epub Ahead of Print <March 28, 2018>; Ovid MEDLINE In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations <March 28, 2018>

Search Date: 29 March 2018

- exp women/

- (female$ or woman$ or women$)

- or/1-2

- vulnerable populations/

- poverty areas/

- ((deprived or destitute? or impoverished or imprisoned or incarcerated or low income or marginalised or marginalized or needy or poverty or prisoner? or vulnerably) adj5 (female? or woman$ or women$)).

- homeless persons/

- homeless$

- (temporar$ adj2 (accommodat$ or home? or hous$))

- ((based or housed or residen$ or temporar$) adj2 shelter?)

- or/4-10

- meta analysis.

- review.pt.

- (medline or pubmed or searched)

- or/12-14

- 3 and 11 and 15

- animals/ not (humans/ and animals/)

- 16 not 17

- remove duplicates from 18

Reference lists for all articles selected for full-text review were manually searched for further relevant citations. These were cross-referenced against our original search results and any additional potentially relevant citations were screened. A published Campbell Evidence and Gap MapFootnote 26 and a focussed grey literature search of documents on the Government of Canada websiteFootnote 27 were used to identify additional studies with disaggregated women-specific data for inclusion. Finally, experts in the field were consulted to ensure inclusion of any additional relevant studies in the grey literature.

Data synthesis with a gender and equity analysis

Following title and abstract screening and full text review, a standardized data extraction form was used to systematically extract data from included studies (i.e. study design, target population, intervention, control group, outcomes). Due to the heterogeneity of the population subtypes studied (women experiencing homelessness who were shelter-based vs. community-based), the many different types of interventions included and the wide range of outcomes measured, there were insufficient data for a meta-analysis and forest plot, and therefore a qualitative (narrative) synthesis was used to describe the findings. Two independent reviewers identified emerging themes by coding data from the data extraction forms; any interpretive differences were resolved through discussion, and themes were compiled and reported narratively.

A gender analysis was carried out based on the Canadian Institutes for Health Research (CIHR) Sex/Gender-Responsive Assessment Scale for Health Research.Footnote 28 Studies were rated on a scale of 0 to 3:

- Gender-blind: Disregards that different genders can be differentially affected (score = 0);

- Gender-sensitive: Acknowledges sex/gender, but not part of study design (score = 1);

- Gender-specific: Acknowledges sex/gender, and part of study design (score = 2);

- Gender-transformative: Addresses gender-related drivers of inequities (score = 3).

An equity analysis further examined whether the studies incorporated broader health equity considerations using the PROGRESS Plus framework (Place of residence, Race/ethnicity/culture/language, Occupation, Gender, Religion, Education, Socioeconomic status, Social capital plus other context-specific factors),Footnote 25 as well as reflecting on how future widespread implementation of the interventions under study could reduce or inadvertently lead to widening health inequities in practice, for instance, better supporting women already accessing shelter supports but potentially leaving further behind women in the community experiencing hidden homelessness.

Results

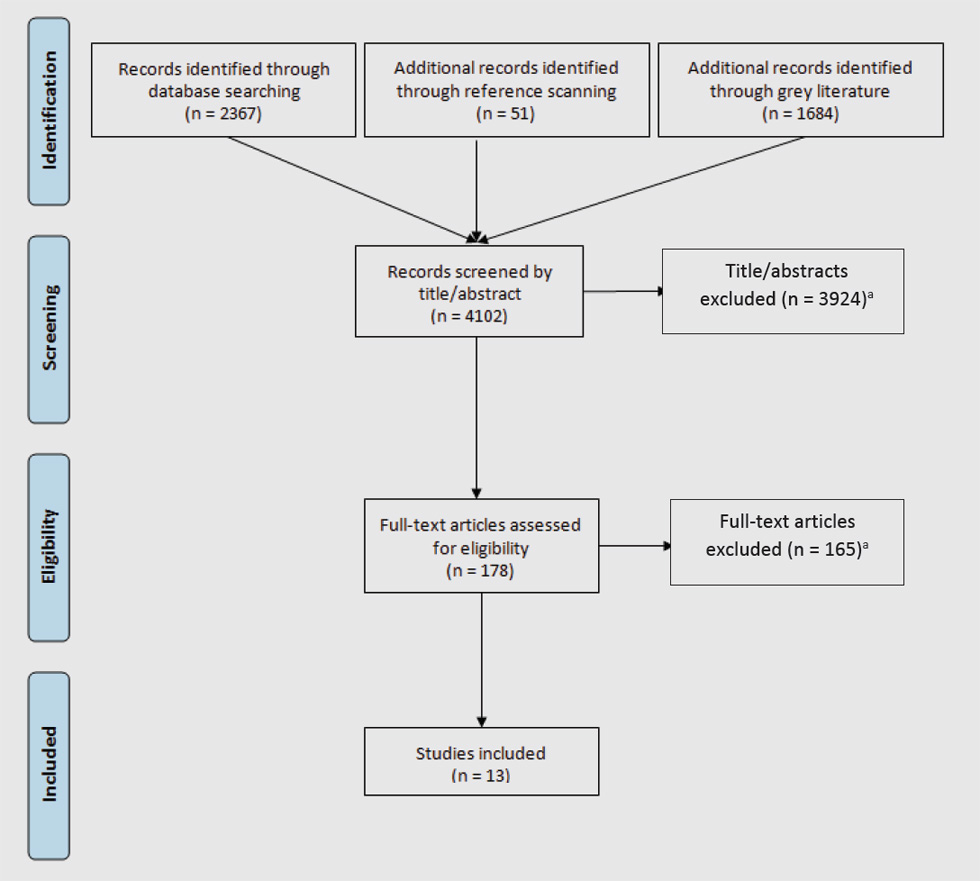

Of 4102 studies identified (2367 by systematic searching, 51 by reference scanning, and 1684 in the grey literature) 3924 were excluded during the title/abstract screening, and a further 165 following full-text review. In total, 13 articles were included in our final analysis, including 4 systematic reviewsFootnote 29Footnote 30Footnote 31Footnote 32 and 9 randomized trialsFootnote 33Footnote 34Footnote 35Footnote 36Footnote 37Footnote 38Footnote 39Footnote 40Footnote 41 conducted in the USA (n = 8), Netherlands (n = 2), UK (n = 1), Australia (n = 1) and Canada (n = 1) (Figure 3). Having satisfied the four main inclusion criteria for this review, each of these articles is based on the highest-quality evidence (i.e. systematic reviews and randomized controlled trials) relevant to the Canadian context (i.e. data collected in high-income country settings), assesses the impact of intervention(s) on housing status and enables a gender analysis (i.e. research focussed on women or disaggregated data on women participants).

Figure 3. PRISMA flowchart of research studies identified by systematic searching multiple sources of evidence and including only highest-quality evidence relevant to Canadian context that allowed a gender analysis of intervention impact on housing status

Text description: Figure 3

Figure 3. PRISMA flowchart of research studies identified by systematic searching multiple sources of evidence and including only highest-quality evidence relevant to Canadian context that allowed a gender analysis of intervention impact on housing status

Figure 3 is a flowchart that shows that 2367 records were identified through database searching, 51 additional records were identified through reference scanning, and 1684 additional records were identified through grey literature. In total 4102 records were screened by title/abstract whereby 3924 title/abstracts were excludedFootnote a. This left 178 articles to be assessed for eligibility whereby 165 were excludedFootnote a, leaving in total 13 studies that were included.

Gender and equity analysis of included studies

Of the 13 included studies (Table 1), 9 studies Footnote 29Footnote 31Footnote 32Footnote 33Footnote 37Footnote 38Footnote 39Footnote 40Footnote 41 were rated as gender-specific, since they acknowledged gender-related needs or trends, and incorporated gender considerations in study design. The remaining 4 studies Footnote 30Footnote 34Footnote 35Footnote 36 were rated as gender-sensitive because they acknowledged gender- or sex-related differences but did not incorporate these considerations in the research design.

| Article | Gender analysis | Equity analysis |

|---|---|---|

| Systematic review 1. Jonker et al.Footnote 29 |

Gender-specific (participants were female IPVFootnote c victims aged >18 years, recruited through shelters) | Place of residence = “shelter” Gender = “women” |

| Systematic review 2. Speirs et al.Footnote 30 |

Gender-sensitive (participants included more than 50% women aged 15–60 years) | Place of residence = “homeless” Ethnicity = “53% were of African American origin”Footnote d Gender = “women and men” |

| Systematic review 3. Rivas et al.Footnote 31 |

Gender-specific (participants included women aged 15 years and over who have experienced IPVFootnote c) | Place of residence = many “living with or still intimately involved with the perpetrator at study entry” Ethnicity = “whites, African Americans and Latinas,”Footnote d one study in this systematic review included “mostly Chinese women” Gender = “women” Education = “few had university studies” Socioeconomic status = “most of the women were on low incomes” |

| Systematic review 4. Wathen and MacMillanFootnote 32 |

Gender-specific (participants included women leaving shelter after at least 1 night’s stay; also included married US Navy couples where active-duty husbands had history of substantiated physical assault of female partners) | Place of residence = “shelter” for at least 1 night Ethnicity = one study had “a sample of predominantly HispanicFootnote d women who were pregnant and had experienced physical abuse” Gender = “women” Plus = focussed on IPVFootnote c, which in this study was “defined as physical and psychological abuse of women by their male partners, including sexual abuse and abuse during pregnancy” |

| Randomized controlled trial 1. Constantino et al.Footnote 33 |

Gender-specific (participants included first-time residents of a domestic violence shelter for abused women in Western Pennsylvania) | Place of residence = “domestic violence shelter” Ethnicity = “Most women were white, not Hispanic,Footnote d and the rest were African Americans” Occupation = Half were unemployed Education = “Most of the women completed high school, and three women had college degrees” Socioeconomic status = three-quarters had annual income less than USD 20 000 Gender = “women” |

| Randomized controlled trial 2. Gubits et al.Footnote 34 |

Gender-sensitive (participants included 2282 families who enrolled in the Family Options Study and had characteristics “similar to characteristics of families who experience homelessness nationwide …. The typical family in the study consisted of an adult woman, a median of 29 years old, living with one or two of her children in an emergency shelter.”) | Place of residence = “Most families in the study (79 percent) were not homeless immediately before entering the shelter from which they were recruited into the study …. Many reported they either had a poor rental history (26 percent had been evicted) or had never been a leaseholder (35 percent).” Occupation = “Most family heads were not working at the time of random assignment (83 percent), and more than one-half had not worked for pay in the previous 6 months.” Socioeconomic status = “The median annual household income of all families in the study at baseline was $7410.” Gender = Different family types enrolled in the study, including single-parent, women-headed families. Plus = “21 percent reported a disability that prevents or limits work” |

| Randomized controlled trial 3. McHugo et al.Footnote 35 |

Gender-sensitive (participants included adults with “severe mental illness who were currently homeless or at high risk for homelessness”) | Place of residence = “Participants were recruited from community mental health centers, hospitals, homeless shelters, food kitchens, drop-in centers, crisis housing, and hotels.… 85.1 percent were homeless…. The average number of months homeless in their lifetime was 51.7, and their average age at the time of their first homeless episode was 28.9 years (SD = 10.9).” Ethnicity = “Most of the participants were African-American (82.6%).” Occupation = “unemployed (90.1%)” Gender = “over half of the final study group members were women (52.1%)” Plus = “72.7 percent of the study group had schizophrenia spectrum disorders and 27.3 percent had mood disorders” |

| Randomized controlled trial 4. Milby et al.Footnote 36 |

Gender-sensitive (participants included “homeless persons from the Birmingham, Alabama, area with coexisting cocaine dependence and nonpsychotic mental disorders…. We examined the relationship of gender to the outcomes of housing, employment, and abstinence. We found no evidence that gender acted as an effect modifier or a confounder.”) | Place of residence = “lacked a fixed nighttime residence, including shelters or other temporary accommodations, or were at imminent risk of becoming homeless” Ethnicity = Most participants were “African American” Occupation = “Longest full-time job” Gender = about one-quarter were female Plus = “cocaine dependence”; “veteran” |

| Randomized controlled trial 5. Nyamathi et al.Footnote 37 |

Gender-specific (participants included “homeless African American, HispanicFootnote d, and AngloFootnote d women and their intimate partners living in an inner-city area of Los Angeles.... Both men and women mostly showed similar improvement on scores.”) | Place of residence = “homeless…defined as one who spent the previous night in a shelter, hotel, motel, or home of a relative or friend and was uncertain as to her residence in the next 60 days or who stated that she did not have a home or house of her own in which to reside” Ethnicity = African American, Hispanic/Latina,Footnote d Anglo American,Footnote d other Occupation = unemployment Gender = “The vast majority of the intimate partners were male (94%); however, 7% of the partners were female” Education = years of education Plus = lifetime history of substance abuse; HIV positive |

| Randomized controlled trial 6. Nyamathi, Leake et al.Footnote 38 |

Gender-specific (participants included “858 women who were residing in 10 homeless shelters and/or 11 drug recovery programs”) | Place of residence = “homeless woman was defined as one who spent the previous night in a shelter, hotel, motel, or home of a relative or friend and was uncertain as to her residence in the next 60 days or stated that she did not have a home or house of her own in which to reside” Ethnicity = “Eligible candidates had to be African-American or LatinaFootnote d women” Occupation = “women were predominantly single, African-American, and unemployed” Plus = “recent history of drug addiction, HIV positive” |

| Randomized controlled trial 7. Nyamathi, Flaskerud et al.Footnote 39 |

Gender-specific (participants included “241 homeless and drug addicted women and their sexual partners”) | Place of residence = “resided in one of 11 homeless shelters and 9 residential drug recovery programs” Ethnicity = “All but two of the women were African-American or LatinaFootnote d” Occupation = “the vast majority of women were unemployed and had children” Gender = women and their sexual partners Religion = “Protestant (75%)” Education = “years of education ranged from 3 to 17 years” Plus = “drug user, a sexual partner of a drug user, a prostitute or homeless and housed in a shelter” |

| Randomized controlled trial 8. Lako et al.Footnote 40 |

Gender-specific (participants were women who “were eligible if they: (1) were aged ≥ 18; (2) stayed at the shelter due to IPVFootnote c or honor-related violence [violence committed to restore or prevent violation of the family honor]; (3) stayed at the shelter for ≥ 6 weeks; (4) had a set date of departure from the shelter or received priority status for social housing; and (5) were moving to housing without daily supervision or support where they would have to pay rent or housing costs”) | Place of residence = shelter Ethnicity = “the proportion of Dutch-speaking women with unmet care needs declined from 88% to 57%, while the proportion of non-Dutch-speaking women with unmet care needs declined from 100% to 90%” Gender = women Education = low, intermediate, high Plus = “unmet care needs” |

| Randomized controlled trial 9. Samuels et al.Footnote 41 |

Gender-specific (participants included “single, female-headed households entering family homeless shelters”) | Place of residence = “shelter” Ethnicity = “Most of the homeless mothers (85%) identified as African American, Latino,Footnote d or other ethnic minority” Occupation = “most (85%) were currently unemployed” Education = “Nearly two-fifths of the mothers did not have a high school diploma” Socioeconomic status = “monthly income” USD 680–810 Plus = “More than 1 out of 5 of the mothers reported that during their childhood, they had been involved in foster care placements” |

|

||

In terms of broader equity considerations, in addition to gender, the included studies also looked at place of residence, since identifying evidence-informed interventions for women experiencing homelessness was the main objective of this review and studies that did not address housing status were excluded. However, of the included studies, most focussed on emergency-sheltered women (i.e. temporarily housed in domestic violence shelters or family homeless shelters) who would be easier to identify and recruit for research.Footnote 29Footnote 31Footnote 32Footnote 33Footnote 34Footnote 40Footnote 41 Very few studies were entirely or partly community-based and included women who were hidden homeless or at risk of homelessness (e.g. precariously housed due to exposure to intimate partner violence).Footnote 0Footnote 31Footnote 32In terms of ethnicity and language, multiple studiesFootnote 30Footnote 32Footnote 33Footnote 34Footnote 35Footnote 36Footnote 37Footnote 38Footnote 39Footnote 40Footnote 41 specified the ethnicity of the population studied, notably women from low-income racialized communities, but did not disaggregate or report on specific findings for minority populations.Footnote 29Footnote 32Footnote 34 The three studies by Nyamathi and colleaguesFootnote 37Footnote 38Footnote 39 focussed on women of African American and Latin American descent diagnosed with HIV in the United States. Lako and colleaguesFootnote 40 made recommendations for migrant women experiencing homelessness who face particular barriers in access to health and social services. One systematic reviewFootnote 31 concluded that further work is needed to ascertain how advocacy interventions can be tailored to different ethnic groups, and to abused women living in rural communities or resource-poor settings. There was little additional information in most of the studies on the women’s education level, occupation, socioeconomic status, or other factors such as physical or cognitive disability, severe mental illness, substance use disorder, adverse childhood experiences or prior involvement in foster care. Even when these equity considerations were identified, they often were not integrated into the study analysis to determine whether or how these factors influenced outcomes.

Gender-related drivers of homelessness among women: violence, poverty and lack of child care

Eight out of 13 studiesFootnote 29Footnote 31Footnote 32Footnote 33Footnote 36Footnote 38Footnote 40Footnote 41 identified a high prevalence of IPV as a gender-specific driver of homelessness. The intervention target population of five studiesFootnote 29Footnote 31Footnote 32Footnote 33Footnote 40 was women experiencing IPV. Abuse was reported to lead to more severe health outcomes and higher health care costs for women.Footnote 31Footnote 32Footnote 33One study Footnote 32 emphasized the importance of intervening with perpetrators of violence, as well as victims, and the need for further research into the effectiveness of both approaches.

Women’s lack of access to and control of resources (e.g. income, education or social support) was identified by six studiesFootnote 29Footnote 30Footnote 33Footnote 38Footnote 40Footnote 41 as another main driver leading to women experiencing homelessness. One studyFootnote 29 highlighted that combining social support with improved access to resources, leading to greater financial autonomy for women, improved their ability to leave abusive relationships. Another studyFootnote 41 reported that connecting mothers to government entitlements and employment programs alleviating poverty and providing opportunities facilitated coping with the trauma of homelessness. Women’s financial dependence on their abusers was identified as a barrier to them leaving abusive situations.Footnote 33

Another resource concern that disproportionately affects women experiencing homelessness is a lack of access to child care. Family units experiencing homelessness are largely female-headed.Footnote 34Footnote 41 One study identified the lack of child care as increasing the risk of homelessness among women.Footnote 36 Three studies reported that the absence of child care acted as a barrier to attending appointments for medical or social servicesFootnote 30Footnote 33 or as a potential cause of loss to follow-up.Footnote 31 Samuels et al. highlighted the additional stress associated with becoming homeless with children,Footnote 41 and Speirs and colleagues reported that women experiencing homelessness need a safe place for themselves and their children.Footnote 30

Evidence-informed interventions and best practices to support women experiencing homelessness

A number of interventions were examined through these primary and secondary research studies including social support, advocacy and case management interventions, as well as permanent housing support interventions (Table 2).

| Populations studied |

|---|

|

| Interventions |

|

| Outcomes |

|

Social support, advocacy and case management intervention

Four systematic reviews and three randomized trials provided evidence on social support, advocacy and case management interventions that significantly improved mental health, social belonging, time to rehousing and health-service utilization among women experiencing homelessness.Footnote 29Footnote 30Footnote 31Footnote 32Footnote 33Footnote 40Footnote 41 Most often these interventions were delivered via the support staff of domestic violence shelters, which are an important type of temporary housing support used as a platform for the delivery of many other interventions.

Emergency-sheltered women experiencing homelessness

Many different types of social support, advocacy and case management interventions have been studied for emergency-sheltered women. For example, Constantino and colleaguesFootnote 33 evaluated an 8-week program consisting of weekly 90-minute sessions offered by a trained nurse who provided women in domestic violence shelters guidance on how to access community resources and promote self-esteem. The program was shown to significantly improve perceived availability of support resources and to reduce women’s psychological distress symptoms as compared to the control group.

Critical time interventions (CTIs) are strengths-based approaches to expand social networks and ensure continuity of care during difficult transition periods in people’s lives (e.g. leaving a domestic violence shelter and moving to a new home). Case managers provide practical and emotional support for one to three hours per week over a period of several months (e.g. helping to furnish the apartment, active listening support or linking the client to support resources). This kind of support has been shown to reduce posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms as well as unmet health care needs, especially among minority populations who do not speak the local language.Footnote 40

A meta-analysis by Jonker and colleaguesFootnote 29 examined a variety of individual and group social support interventions provided to emergency-sheltered women experiencing homelessness following the escalation of IPV, including group counselling, coping skills training, problem-solving techniques, music therapy, cognitive behavioural techniques, the development of parenting skills, stress management and brief one-on-one advocacy services. They found that these shelter-based and post-shelter social support interventions were effective in improving women’s mental health outcomes, in decreasing abuse and in improving social outcomes.

The systematic review by Wathen and MacMillanFootnote 32 also found that among women who have spent at least one night in a shelter, “there is fair evidence that those who received a specific program of advocacy and counselling services reported a decreased rate of re-abuse and an improved quality of life.”Footnote 32,p.589 The post-shelter advocacy services involved assisting women for four to six hours a week for 10 weeks with devising safety plans (if needed) and accessing community resources such as housing, employment and social support. Rivas and colleagues specifically examined advocacy interventions and similarly found that intensive advocacy for women in domestic violence shelters improved quality of life and reduced physical abuse for a period of one to two years after the intervention.Footnote 31

Women in the community experiencing hidden homelessness or at risk of homelessness

Speirs and colleaguesFootnote 30 conducted a systematic review of effective interventions that community nurses could use to support women experiencing homelessness in community-based settings (e.g. hidden homelessness or at risk of homelessness). They found that social support interventions such as structured education and support sessions (with or without advocates or support persons), as well as therapeutic communities, reduced psychological distress and health care use, improved self-esteem and reduced drug and alcohol use (i.e. maladaptive forms of coping).

Wathen and MacMillanFootnote 32 similarly attempted to identify evidence-based interventions that would be applicable in primary care settings to reduce IPV, and thus protect women at risk of homelessness from escalation of violence. However, they found insufficient evidence to screen all women systematically for IPV in primary care settings, though targeted case finding is still important for women presenting with violence-related issues who require referral and support.

Rivas and colleaguesFootnote 31 found moderate evidence that brief advocacy may provide small, short-term mental health benefits and reduce abuse, particularly for pregnant women, since IPV can increase around the time of pregnancy and therefore increase risk of homelessness and other negative outcomes.

Permanent housing support interventions

Four randomized trials examined permanent housing support interventions that improved housing stability and positively impacted mental health, quality of life and substance use outcomes.Footnote 34Footnote 35Footnote 36Footnote 41

Family critical time interventions (FCTIs) involve case managers who support mothers with children over 9 months old in creating and maintaining effective links to community resources and accessing relevant services (including mental health support, childcare, employment linkages) and through assistance in applying for benefits, to gradually identify and transition to stable community housing and supports.Footnote 41 Mothers experiencing homelessness who accessed FCTIs plus scattered-site housing exited the shelter and obtained stable housing significantly more rapidly, with three-quarters housed within 100 days compared to 300 days or more for families receiving services-as-usual.Footnote 41 Both abstinence-contingent and non-abstinence-contingent housing increased number of days women were housed, employed and abstinent, though abstinence-contingent housing was somewhat more successful in decreasing the incidence of substance use.Footnote 36

McHugo et al.Footnote 35 examined permanent supportive housing with integrated case management services (“integrated housing”) versus community-based housing with case-management services provided in parallel (“parallel housing”), and found that both interventions increased stable housing and reduced functional homelessness, time spent in institutional settings and exposure to interpersonal violence, particularly for those benefitting from integrated housing services. The authors note that “the most surprising finding in this study was the emergence of gender as a moderator variable,”Footnote 35, p.979whereby landlords in community-based housing were more likely to consider male participants as potentially threatening, whereas women “were often seen as victims and accorded more benign decisions regarding their housing.”Footnote 35, p.979 Thus, among those in the parallel housing stream, female participants spent more time in stable housing and reported greater overall life satisfaction than their male counterparts.

The Family Options study enrolled families experiencing homelessness who had spent at least seven days in a family shelter.Footnote 34 Over two-thirds were female-headed, single-parent families. Families were randomized to receive one of three interventions or be assigned to a control group receiving usual care in which families needed to find their own housing without access to specific interventions or additional support. The most effective intervention was priority access to deep permanent housing subsidies. The permanent housing subsidies were often in the form of ongoing rental assistance using tenant-based vouchers allowing families to rent the apartment of their choice in the private housing market but only pay a maximum of 30% of their adjusted monthly income, with the rest covered by the subsidy. These subsidies were sometimes accompanied by assistance in initially finding housing but proved to be highly effective even if not coupled with additional supportive services. Families receiving the tenant-based voucher permanent housing subsidies had significant reductions in homelessness, housing instability, use of emergency shelters up to 18 months post intervention, food insecurity, exposure to violence and psychosocial distress compared to usual care.Footnote 34 These families also had fewer child separations and foster care placements, and significant improvements in school stability and multiple other measures of adult and child well-being.

In contrast, those who were instead randomized to receive community-based rapid re-housing offering only temporary rental assistance renewable up to a maximum of 18 months, or those receiving temporary housing for up to 24 months in agency-controlled buildings with support services, had almost no impact on the incidence of IPV, homelessness, housing stability or rates of family preservation. Moreover, these interventions were nearly as costly as permanent housing subsidies, but were significantly less effective across multiple outcomes, and had only marginal added value over usual care.Footnote 34

Discussion

This scoping review with a gender and equity analysis identified evidence-informed interventions and best practicesFootnote 42 that help to overcome gender-related drivers of homelessness among women, notably, exposure to intimate partner violence and lack of financial independence. These interventions include social support, advocacy and case management (e.g. post-shelter advocacy counselling, therapeutic communities, group counselling, critical time interventions, etc.), as well as permanent supportive housing (e.g. tenant-based rental assistance) with or without case management.

The interventions for which there is consistent and stronger evidence across studies included post-shelter advocacy counselling, permanent housing subsidies and case management. For women experiencing homelessness due to IPV, post-shelter advocacy counselling resulted in lower rates of re-abuse, greater access to resources and improved quality of life.Footnote 32 Permanent housing subsidies (e.g. tenant-based rental assistance vouchers) for women with children spending at least seven days in a family shelter were shown to reduce housing instability, food insecurity, exposure to violence and psychosocial distress, as well as significantly improving school stability and child well-being outcomes.Footnote 34 The addition of case management (including FCTIs) helped women exit shelters and access stable housing more rapidly,Footnote 41 while reducing exposure to IPV, homelessness and time spent in institutional settings.Footnote 35

Support for these interventions is further corroborated by the evidence reviews of the Canadian Task Force on Preventive Health Care,Footnote 43 the US Guide to Community Preventive ServicesFootnote 44 and the new Canadian Medical Association Journal Clinical Guidelines for Homeless and Vulnerably Housed People and People with Lived Homelessness Experience.Footnote 19

In addition to being evidence-informed, it is also important to be trauma-informed.Footnote 45 Women experiencing or at risk of homelessness may suffer many traumatic losses, including the loss of a safe place to live, disruptions at work and the resulting instability for their family.Footnote 46 Women should therefore be involved in the decisions that affect them, and be empowered to choose the types of interventions that are right for them and their specific situation so that they can have greater agency to determine their future and that of their family.Footnote 47

Strengths and limitations

A major strength of this study was the inclusion of a gender and equity analysis, allowing a better understanding of different pathways into homelessness for women, as well as different approaches for supporting those already experiencing and at risk of homelessness, particularly in relation to IPV and poverty.

A limitation of this study is that much of the current evidence base focusses on women experiencing homelessness who are emergency-sheltered (i.e. in domestic violence shelters or family homeless shelters), with much less research available to guide community-based intervention decisions and much-needed outreach for the even larger proportion of women who are hidden homeless or at risk of homelessness. The evidence is also quite heterogeneous. Different studies examine a number of different study subpopulations, types of interventions (often complex, multicomponent interventions) and outcome measures, which also makes it very difficult to conduct quantitative synthesis (e.g. meta-analysis) to determine the efficacy and effect size of any given intervention. As well, while the search strategy included the terms “wom*n” and “female”, we recognize the possibility that evidence specific to other subpopulations of women, for example, trans women, may not have been adequately identified and addressed by this search.

Implications for policy and practice

While women living in Canada have high rates of educational attainment, Canada falls far below other high-income countries in terms of women’s economic participation, pay index and political empowerment.Footnote 48 Annually in Canada, 96 000 individuals, the majority women, are victims of police-reported intimate partner violence.Footnote 49 It is well known that this grossly underestimates the actual number of women experiencing interpersonal violence, which, combined with women’s lack of financial independence, is a major driver putting women at risk of homelessness. While shelters provide temporary refuge during times of crisis, these experiences are highly disruptive. What women and children need is to be housed in safe, affordable, permanent housing equipped with adequate social supports and resources to overcome challenges in family dynamics and exposure to violence, or at the very least to have an exit strategy that allows them to rebuild their lives without needing shelters, which often remain a “last resort.”

Conclusion

During the COVID-19 pandemic, responding to the needs of women experiencing or at risk of homelessness has become more urgent than ever, as families are at home in close quarters, with schools and daycares closed for extended periods and rates of domestic violence on the rise worldwide.Footnote 50 Women accounted for almost three-quarters of job losses in Canada during the first wave of COVID-19. The pandemic also revealed the extent to which women work in child care and elder care, sectors that are often underfunded and involve large proportions of informal and unpaid work, even though it is critical to the functioning of our economy and society.Footnote 51

Even before COVID, women with children, particularly single mothers, earned less than women without children.Footnote 52 Women’s economic empowerment interventions and legal reforms are central to IPV prevention approaches,Footnote 53 which in turn can prevent homelessness. It is now possible to imagine a post-COVID Canada where there is an end to woman and child homelessness through greater investments in promoting gender equity.Footnote 51 This could involve a number of structural changes, including formalizing care work with pay scales and benefits, transforming gender norms, improving access to child care, ensuring pay equity, creating opportunities for parental leave and work-life balance, ensuring job protection for persons with disabilities and other pro-equity policies and programs.

Creating more supportive social environments for health across the life course involves helping to support families in creating stronger adult-adult and adult-child attachments and nurture social-emotional competencies for families through prenatal classes and nurse home visitation programs, as well as in daycares and schools, to create greater family stability and to reduce IPV and adverse childhood experiences, which are often precursors to homelessness.

Since the number of women and children in shelters is only the “tip of the iceberg,” a population approach can improve outcomes for many more women and their children, before they reach a crisis situation.Footnote 54 Greater efforts are therefore needed to measure the iceberg “below the surface” of IPV and hidden homelessness among women to better appreciate the true magnitude of the situation and the specific causes, to better support women with lived experience and to prevent homelessness.

Acknowledgements

This work was funded in part by the Public Health Agency of Canada. The authors would like to thank Kaitlin Schwan and Arlene Hache for permission to reprint Figure 1.

Conflicts of interest

No competing interests are declared by the authors.

Authors’ contributions and statement

All authors were involved in the conception of the study. SM, CM and OM led the data extraction and initial analysis of the data. AA drafted the final version of the manuscript, and all authors reviewed and approved the final version for publication.

The content and views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Government of Canada.