Commentary – Timing of 24-hour movement behaviours: implications for practice, policy and research

HPCDP Journal Home

Published by: The Public Health Agency of Canada

Date published: April 2022

ISSN: 2368-738X

Submit a manuscript

About HPCDP

Browse

Previous | Table of Contents | Next

Jennifer R. Tomasone, PhDAuthor reference footnote 1; Ian Janssen, PhDAuthor reference footnote 1Author reference footnote 2; Travis J. Saunders, PhDAuthor reference footnote 3; Mary Duggan, CAEAuthor reference footnote 4; Rebecca Jones, BAAuthor reference footnote 5; Melissa C. Brouwers, PhDAuthor reference footnote 6; Guy Faulkner, PhDAuthor reference footnote 7; Stephanie M. Flood, MScAuthor reference footnote 1; Kirstin N. Lane, PhDAuthor reference footnote 4Author reference footnote 8; Amy E. Latimer-Cheung, PhDAuthor reference footnote 1; Jean-Philippe Chaput, PhDAuthor reference footnote 6Author reference footnote 9

https://doi.org/10.24095/hpcdp.42.4.05

Author references

Correspondence

Jennifer Tomasone, School of Kinesiology and Health Studies, Queen’s University, Kingston, ON K7L 3N6; Tel: 613-533-6000 ext. 79193; Email: tomasone@queensu.ca

Suggested citation

Tomasone JR, Janssen I, Saunders TJ, Duggan M, Jones R, Brouwers MC, Faulkner G, Flood SM, Lane KN, Latimer-Cheung AE, Chaput JP. Timing of 24-hour movement behaviours: implications for practice, policy and research. Health Promot Chronic Dis Prev Can. 2022;42(4):170-4. https://doi.org/10.24095/hpcdp.42.4.05

Keywords: physical activity, sedentary behaviour, sleep, timing, knowledge translation, public health, 24-Hour Movement Guidelines

Highlights

- For health benefits, Canadians need to:

- move when it suits them;

- remove screens from bedrooms and limit screen use prior to bedtime; and

- adjust bedtime so that they can sleep the recommended amount.

- The 24-Hour Movement Guidelines Communication Toolkit has resources that can be used across settings to help Canadians optimize movement behaviours throughout the day.

Introduction

Physical activity, sedentary behaviour and sleep cannot be considered in isolation given their co-dependence: their integration within the 24-hour day has important health implicationsFootnote 1Footnote 2Footnote 3. This paradigm shift to an integrated approach to movement behaviours has led to the Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology (CSEP) developing and releasing the world’s first 24-hour movement guidelines (24HMGs) for all agesFootnote 4Footnote 5Footnote 6Footnote 7. The 24HMGs are evidence-based recommendations for optimal levels of physical activity, sedentary behaviour and sleep according to age group: infants, toddlers and preschoolers (0–4 years)Footnote 5; children and youth (5–17 years)Footnote 4; and adults (18–64 years and 65+ years)Footnote 6. The guidelines emphasize that the integration of these behaviours over a 24-hour period is important for health benefits, that is, “the whole day matters” for health.

With recent, focussed efforts to disseminate the 24HMGs in Canada,Footnote 8Footnote 9 the concept of “the whole day matters” is gaining traction. The tagline accompanying the guidelines—“Move more. Reduce sedentary time. Sleep well”—has simplified the recommendations into a single, generic message to help foster Canadians’ confidence to meet the 24HMG recommendationsFootnote 8Footnote 10.

While the 24HMGs (and tagline) offer guidance on what to do, the public, practitioners, policy makers and researchers have asked for advice about how to do it, including optimal timing for movement behaviours. In other words, should physical activity be done in the morning, afternoon or evening? Should recreational screen time be avoided before bed? Does it matter what time a person goes to bed if they get sufficient sleep?

Researchers recently synthesized the literature examining the health outcomes associated with the timing of movement behavioursFootnote 11Footnote 12Footnote 13. The main findings of the systematic reviews in this special issue of the journal indicate that, for health benefits, Canadians need to:

- move when it suits themFootnote 11;

- remove screens from bedrooms and limit screen use prior to bedtimeFootnote 12; and

- adjust bedtime so that they can sleep the recommended amountFootnote 13.

This commentary aims to:

- offer evidence-informed advice for practice, policy and research regarding the optimal timing of movement behaviours across a number of settings; and

- draw attention to existing and new promotional materials for the 24HMGs that advise Canadians on how they can make their “whole day matter.”

Advice for practice, policy and research

Readers can refer to the CSEP and ParticipACTION websites for recommendations on physical activity, sedentary behaviour and sleep by age group. Given that 24HMGs exist for all age groups, it is impossible to develop an exhaustive list of end users or settings where the review findings could be applied. Instead, we have organized potential end users according to the settings in which they could consider the timing of movement behavioursFootnote 14Footnote 15. We include advice for practice, policy and/or research where applicable to a given setting. The advice can be applied across the life course as studies exist to support findings across all agesFootnote 16 and the information is beneficial to Canadians’ health regardless of age.

Household settings

A household encompasses a person living alone or a group of people living in the same dwelling, be it a family, several families or unrelated individuals of all agesFootnote 15. End users in the household setting include infants, children, youth and adults. This setting is important to movement behaviour timing because this is where Canadians generally sleep and where movement behaviour habits are formed and perpetuatedFootnote 15.

The 24HMGs specify that moderate-to-vigorous physical activity, as well as light physical activity, of sufficient duration (according to age group) are critical for health benefits. Given that physical activity is equally beneficial whether it is done in the morning, afternoon or evening,Footnote 11 choosing when to be active should be up to the individual as long as they maintain healthy sleep behaviours. This means that if you get up early to exercise because that is when it easiest for you to be active, you should go to bed early so that you get enough sleep.

The 24HMGs recommend daily limits for screen time that differ by age. Removing screen-based devices from bedrooms and eliminating screen time (i.e. scrolling through social media, watching TV or movies) prior to bed are strategies to optimize sleep duration and quality. While Saunders and colleaguesFootnote 12 indicate that there is insufficient evidence to suggest a threshold for how much time we should have without screens before bed, the American Academy of PediatricsFootnote 17 and the Canadian Pediatric SocietyFootnote 18 recommend avoiding screens for at least one hour before bed.

The 24HMGs also recommend uninterrupted sleep of sufficient duration (according to age) with consistent waking and bedtimes across the week. Later sleep timing (i.e. going to sleep at a later time) is associated with adverse health outcomes for children and youthFootnote 11 as well as adultsFootnote 16. Given that many people’s school and work start times are fixed, early sleep times throughout the entire week (vs. variations between weekend and school/work week) are ideal.

Education settings

Education settings include schools and school-boards with childcare, elementary, secondary and postsecondary divisions. Education settings reach a large proportion of the Canadian population—infants, toddlers, preschoolers, young children, youth and young adults—and indirectly reach others—siblings, parents, grandparents, caregivers, teachers, administrators, etc.

In-class education settings can adjust how they operate to enable physical activity and limit screen use throughout the day as well as encourage earlier bedtimes. Presenting opportunities for and encouraging light physical activity (i.e. standing, active sitting/seated movement, breaks for stretching) and/or bursts of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity can foster a culture where students move more. Students will experience the immediate benefits of physical activity on their ability to focusFootnote 19 and learn to identify when their body prefers to move.

At the elementary and secondary levels, teachers should consider the volume, frequency and modality (e.g. paper-based vs. screen-based)Footnote 20 of homework to help students get to bed early enough and limit screen exposure near bedtime. Postsecondary instructors may choose to adjust the due times for assignments to during the day or early evening; the authors’ experience is that this strategy successfully helps students avoid staying up late to submit assignments and use screens close to bedtime.

One policy lever to create a culture of healthy movement behaviours is through curriculum design and implementation. Specifically, we need to embed into all curricula an awareness of the importance of 24-hour movement behaviours as well as advice on “how to” apply the 24HMGs to lifestyles. The 24HMGs need to be reiterated at multiple points, in a similar way to how Canada’s Food GuideFootnote 21 is integrated into childcare, elementary, secondary and postsecondary curricula. Also required is training and professional development to foster expertise among educators and enable the implementation of these new aspects of the curriculum as well as teachable moments.

A second policy lever is reconsideration of school hours. For example, delaying start times of secondary schools would help improve sleep duration among youthFootnote 22; further research is required to determine how long to delay school start times.

Both policy levers require the action of administrators and policymakers who are responsible for system-level adjustments for what, how and when students learn.

Workplace settings

Workplace settings include all the organizations that employ Canadians—which amounts to a substantial proportion of the population. Workplaces can strive to ensure that their mandates, strategic plans, operating practices and external messages encourage employees and others to optimize movement behaviours.

Enacting an organizational policy to foster a culture that encourages physical activity (i.e. movement breaks) throughout the day and promotes less screen use in the evening (e.g. not expecting responses to email or work to be done in the evening) would support the implementation of findings published in this special issue of the journal. Some workplaces may also be able to enact a flexible work policy to help promote the preservation of sleep duration and consistency for employees and their household.

Settings with health and exercise professionals

Canadians consider health professionals—nurses, physicians, dietitians, physiotherapists, etc.—as experts and credible sources of information on movement behaviourFootnote 23. Qualified exercise professionals (including CSEP Certified Personal Trainers, CSEP Clinical Exercise Physiologists and kinesiologists) are trained to educate and counsel the public about healthy lifestyles including physical activity, sedentary behaviours and sleep. Through their interactions with patients/clients and caregivers, professionals in this setting offer trusted information for healthy movement across the life course.

The findings about the optimal timing of movement behaviours may support conversations about lifestyles that health professionals have with patients/clients. The advice in this commentary can be given as practical tips and answers to commonly asked questions. We need changes to training curricula, additional professional development opportunities and tools so that practitioners are knowledgeable and can confidently discuss movement behaviours (including optimal timing of behaviours).

Community service settings

Community service settings include staff, coaches, instructors and administrators at physical activity, child/youth services and community organizations that offer programs and services to Canadians of all ages (e.g. after-school programs, arts and recreation programs, national and provincial sport organizations, local community centres). Encouraging optimal movement behaviour timing is important in these settings as their mandates generally focus on promoting the health and well-being of the individuals they serve.

Options to exercise need to be available at various times to make it easier for individuals to be physically active when it suits them. Practices or programs, particularly those for children and youth, should not be at times that interfere with their ability to get optimal sleep duration, consistency and timing. If early morning programming is unavoidable (e.g. access to pools or ice rinks), coaches/instructors need to encourage earlier bedtimes to balance the gains from physical activity against the threats of interrupted sleep among participants.

Note that there is some interdependence between this setting and the education setting, and delaying school start times would impact potential start times of programs. Policy changes to support optimal timing of movement behaviours among children and youth needs to be coordinated across these two settings—ideally in consultation with the household setting to ensure parent/guardian support for changes.

Settings that endorse or study movement, health and well-being

These settings include governmental and nongovernmental organizations, intermediary groups and workplaces that communicate health information to members of the general public (e.g. ParticipACTION, Canadian Public Health Association, PHE Canada, Lifeworks) or fund health research initiatives (e.g. Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Public Health Agency of Canada, Heart and Stroke Foundation). These settings have substantial reach, are seen as credible sources of health information and have a role to play in communicating and integrating the advice we present here into their practices.

Organizations that provide health funding can prioritize the research gaps identified in the systematic reviews published in this issue. Specifically, there is a need for high quality randomized intervention studies with larger sample sizesFootnote 11Footnote 12Footnote 13 that examine the chronic impact of changing behaviour timing on health outcomesFootnote 12. Of note, while Janssen et al.Footnote 11 identified that there are no health implications based on the time of day that physical activity is performed, motivation to engage in physical activity may waiver throughout the day (e.g. people who plan to be active in the morning are more likely to carry through with their goalFootnote 24). Additional research exploring the psychological antecedents of the timing of all three movement behaviours is warranted.

Several organizations in this category are involved in the surveillance of Canadians’ movement behaviours. Changes to surveillance measures are not required as a result of the new evidence presented in this special issue of the journal. However, current surveillance must be maintained to evaluate ongoing efforts to promote the “whole day matters” in the described settings.

24HMG promotional materials on how Canadians can make their “whole day matter”

The novel findings in this special issue complement the suite of Canadian 24HMGsFootnote 4Footnote 5Footnote 6 by providing evidence for optimizing the timing of movement behaviours with additional tips on how to implement the guidelines.

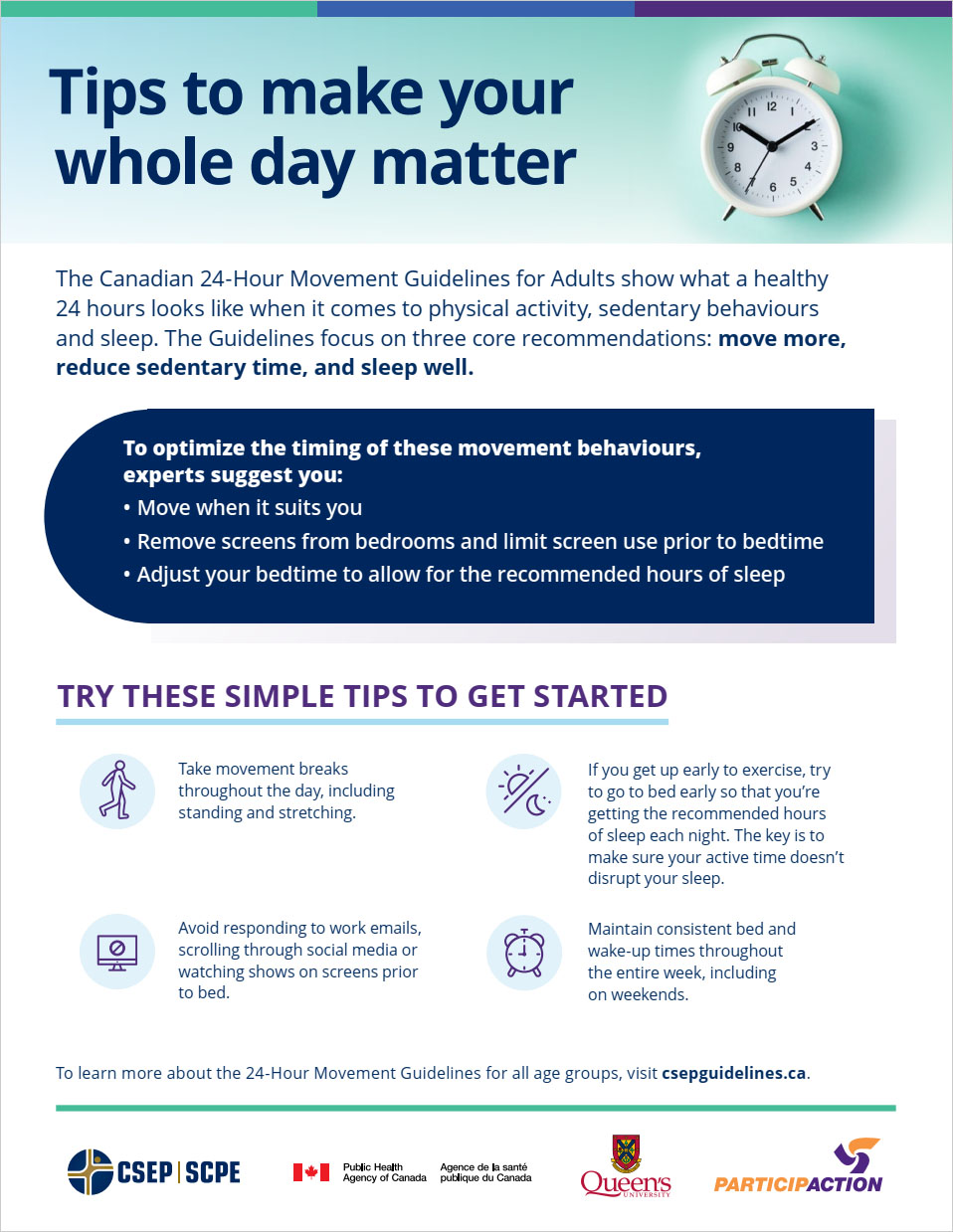

To assist with the dissemination of the review findings and the advice outlined in this commentary, the CSEP has developed a poster, Tips to make your whole day matter, highlighting key advice about optimal timing of movement behaviours for better health outcomes (see Figure 1). All 24HMG promotional materials, including this poster, are available in the 24-Hour Movement Guidelines Communications Toolkit on the CSEP and ParticipACTION websites.

Figure 1 - Text description

This figure is a poster entitled “Tips to make your whole day matter”. It presents the following information:

The Canadian 24-Hour Movement Guidelines for Adults show what a healthy 24 hours looks like when it comes to physical activity, sedentary behaviours and sleep. The Guidelines focus on three core recommendations: move more, reduce sedentary time, and sleep well.

To optimize the timing of these movement behaviours, experts suggest you:

- Move when it suits you

- Remove screens from bedrooms and limit screen use prior to bedtime

- Adjust your bedtime to allow for the recommended hours of sleep

Try these simple tips to get started:

Take movement breaks throughout the day, including standing and stretching.

Avoid responding to work emails, scrolling through social media or watching shows on screens prior to bed.

If you get up early to exercise, try to go to bed early so that you’re getting the recommended hours of sleep each night. The key is to make sure your active time doesn’t disrupt your sleep.

Maintain consistent bed and wake-up times throughout the entire week, including on weekends.

To learn more about the 24-Hour Movement Guidelines for all age groups, visit csepguidelines.ca.

Conclusion

The three systematic reviews in this special issue of the journal synthesized evidence about optimal timing of movement behaviours. The findings will have implications for how Canadians think about and engage in physical activity, sedentary behaviour and sleep throughout the 24-hour period. We have made suggestions and produced resources to help Canadians implement the review findings, and the 24HMGs, in their daily lives, across settings. It is critical that public health practitioners, policy makers and researchers heed the advice in a unified effort to help Canadians make their whole day matter.

Acknowledgements

The developed resources were funded by the Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology (CSEP) and were produced by ParticipACTION.

Conflicts of interest

TJS has received honorariums for public speaking on the relationship between sedentary behaviour, physical activity and health among children and youth. SMF received personal fees from the Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology during the development of this commentary.

Authors’ contributions and statement

All authors conceptualized the ideas presented, contributed to figure development, provided a critical review of the commentary, and approved the final manuscript for submission.

JRT, IJ, TS and JPC contributed to the writing of this commentary.

The content and views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Government of Canada.