Evidence synthesis – A comparative systematic scan of COVID-19 health literacy information sources for Canadian university students

HPCDP Journal Home

Published by: The Public Health Agency of Canada

Date published: March 2022

ISSN: 2368-738X

Submit a manuscript

About HPCDP

Browse

Previous | Table of Contents | Next

Sana Mahmood, BScAuthor reference footnote 1; John Vincent Lobendino Flores, BAAuthor reference footnote 2; Erica Di Ruggiero, PhDAuthor reference footnote 3; Paola Ardiles, MBAAuthor reference footnote 2; Hussein Elhagehassan, BAAuthor reference footnote 2; Simran PurewalAuthor reference footnote 2

https://doi.org/10.24095/hpcdp.42.5.02

(Published 16 March 2022)

This article has been peer reviewed.

Author references

Correspondence

Sana Mahmood, Faculty of Arts and Science, University of Toronto, 100 St. George St., Toronto, ON M5S 3G3; Tel: 647-704-6523; Email: sana.s.mahmood@gmail.com

Suggested citation

Mahmood S, Lobendino Flores JV, Di Ruggiero E, Ardiles P, Elhagehassan H, Purewal S. A comparative systematic scan of COVID-19 health literacy information sources for Canadian university students. Health Promot Chronic Dis Prev Can. 2022;42(5):188-98. https://doi.org/10.24095/hpcdp.42.5.02

Abstract

Introduction: With the rapid spread of online coronavirus-related health information, it is important to ensure that this information is reliable and effectively communicated. This study observes the dissemination of COVID-19 health literacy information by Canadian postsecondary institutions aimed at university students as compared to provincial and federal government COVID-19 guidelines.

Methods: We conducted a systematic scan of web pages from Canadian provincial and federal governments and from selected Canadian universities to identify how health information is presented to university students. We used our previously implemented health literacy survey with Canadian postsecondary students as a sampling frame to determine which academic institutions to include. We then used specific search terms to identify relevant web pages using Google and integrated search functions on government websites, and compared the information available on pandemic measures categorized by university response strategies, sources of expertise and branding approaches.

Results: Our scan of Canadian government and university web pages found that universities similarly created one main page for COVID-19 updates and information and linked to public sector agencies as a main resource, and mainly differed in their provincial and local sources for obtaining information. They also differed in their strategies for communicating and displaying this information to their respective students.

Conclusion: The universities in our sample outlined similar policies for their students, aligning with Canadian government public health recommendations and their respective provincial or regional health authorities. Maintaining the accuracy of these information sources is important to ensure student health literacy and counter misinformation about COVID-19.

Keywords: COVID-19, health literacy, public health, online information, Canada, postsecondary students, university

Highlights

- This paper identifies measures taken by postsecondary institutions to enhance student COVID-19 health literacy in Canada.

- Advice from Canadian universities is compared to Canadian provincial and federal government public health guidelines.

Introduction

COVID-19 was declared a global pandemic on 11 March 2020 by the World Health Organization.Footnote 1 The first known case occurred in Wuhan, China, in December 2019, and the first case in Canada was detected on 25 January 2020.Footnote 1 The pandemic also gave rise to a COVID-19 “infodemic,” or “information epidemic,” which is an overwhelming amount of information spread rapidly through communication technologies.Footnote 2 This surplus of information includes both credible information and misinformation.Footnote 2 In relation to COVID-19, this ranges from information on viral distribution and preventive measures published by reliable public health authorities, to unsubstantiated “remedies,” to claims by unauthorized sources of the virus being a hoax.Footnote 3

Previous research has revealed that conspiracy allegations can directly impact preventive behaviours; this has arisen not only in the context of COVID-19, but for past major disease outbreaks including HIV and the Zika virus.Footnote 3 The distribution of, access to and uptake of credible information thus play important roles in mitigating pandemic spread and contributing to the success of public health measures. Credible health resources may aid individuals in developing the skills to identify pandemic-related misinformation and are key to ensuring health literacy.

Health literacy is the “degree to which people are able to access, understand, appraise and communicate information to engage with the demands of different health contexts to promote and maintain health across the life-course.”Footnote 4,p.ii In addition to accessing information, health literacy is also necessary for applying the acquired information to making health-related decisions.Footnote 4 Conversely, low levels of health literacy may signify difficulty in understanding health conditions and related information, thereby affecting an individual’s health-related decision-making processes.Footnote 4 With the ongoing pandemic, it is necessary to enhance literacy to promote better understanding of the public health information available, and to thereby encourage compliance with public health protocols.

From 1 July to 30 September 2020, we conducted a cross-sectional survey of COVID-19-related health literacy in Canadian postsecondary students, which served as context for the present study.Footnote 5 The survey was conducted by researchers at the University of Toronto and Simon Fraser University, in partnership with the international COVID-19 Health Literacy Consortium (a global network for research on health literacy and digital health literacy), and obtained data on the health literacy of young adults in over 50 countries.Footnote 6 The survey revealed that Canadian young adults frequently accessed sources of health information about the coronavirus through websites of public sector bodies such as the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC), as well as other health portals. The use of these reputable sources was reported to be beneficial by students, since it might enhance their health literacy through reliable and accurate information distribution.Footnote 5

Ideally, curtailing coronavirus misinformation in students should also be a priority for academic institutions. In pursuing mitigation strategies for COVID-19, postsecondary institutions in Canada shifted early in the pandemic to remote learning methods, with the cessation of many in-person activities, in accordance with physical distancing measures and national and provincial pandemic restrictions.Footnote 7 This sudden transition into remote learning created new challenges for students in adapting to the online learning environment, particularly due to the lack of previous online learning opportunities.Footnote 7Footnote 8 Because of this new online learning environment, postsecondary students who require constant access to the Internet may also experience increased exposure to both reliable and unreliable online claims, which in turn may affect their understanding of current health information. Academic institutions can collectively help to reverse the confusion and misinformation stemming from these unauthorized sources and improve student health literacy by mirroring official government public health information, thereby also providing consistency in the information presented by each institution. As postsecondary students may communicate health information to others, it is important to ensure that this population group is also able to effectively access, comprehend and evaluate the credibility of online information sources.Footnote 5

There is limited research regarding the health literacy of postsecondary students, particularly those in Canada, and few studies focus on the sources from which students are receiving health information.Footnote 5 This study aims to address this knowledge gap within the context of the COVID-19 pandemic in Canada. In this paper, we report on a systematic scan of publicly available sources of health information from both federal and provincial government websites and postsecondary institutions. Our scans aimed to examine (1) what information on pandemic measures was disseminated to universities and students by the federal and provincial governments and by Canadian universities; (2) how these sources compare with each other; and (3) whether this access to health information had an impact on the health literacy levels self-reported by postsecondary students.

Methods

To identify the health information available to university students, we conducted systematic scans of publicly available information drawn from government and university web platforms. We defined this systematic scanning process as the identification of and data extraction from relevant web pages guided by the application of specific search and inclusion/exclusion criteria listed in the sections that follow. The time frame for scanning government platforms was July to October 2020, and the time frame for scanning university platforms was November 2020 to January 2021.

Scans of publicly available information drawn from government platforms

In deciding which government agencies and types of information to use in our scan, we created criteria for inclusion and exclusion as follows. Included were official Canadian federal government and Ontario and British Columbia provincial government web pages, publicly available (i.e. not in private domains, and accessible to the general public) online information about COVID-19, and information that would affect postsecondary students and institutions (i.e. through closures of facilities and travel restrictions). Excluded were municipal government web pages and private databases.

We chose not to include municipal and city-level data, because, due to the pandemic, we could not assume that students were physically based in the city where their institution was located. We relied only on publicly available information for accessibility reasons, as these sources are likely more readily available to all students compared to private web pages blocked to individuals not part of a specific organization, or requiring subscription. Finally, because the international survey that we referenced as a sampling frame was focussed on postsecondary institutions, we limited the information sources we observed to those relevant to the postsecondary setting.

After determining these inclusion/exclusion criteria, we selected three relevant public sector agencies to search, based on the study location: the official sites of the governments of Canada, Ontario and British Columbia. We then performed a search using the websites’ integrated search functions with the search terms “COVID-19” plus one of the following: “policy”, “measures”, “public health” or “postsecondary”. This resulted in the inclusion of eight government web pages, including the Government of Canada’s federal legislationsFootnote 9Footnote 10Footnote 11 and guidance for postsecondary institutions,Footnote 12 PHAC’s individual and community-based measures to mitigate the spread of COVID-19 in Canda,Footnote 13 the province of Ontario’s pandemic restrictions and framework for reopening the provinceFootnote 14Footnote 15 and the province of British Columbia’s pandemic restrictions and BC restart plan.Footnote 16

The time frame for scanning government web pages was from July to October 2020; therefore, the results are limited to the most recent available at that time. We scanned the web pages by extracting and summarizing information about the pandemic public health measures (which we defined as a range of regulations, policies and guidance) put in effect by federal and provincial governments that would affect academic institutions and students, as well as guidelines for how to enact and follow these measures.

Scans of publicly available information drawn from university platforms

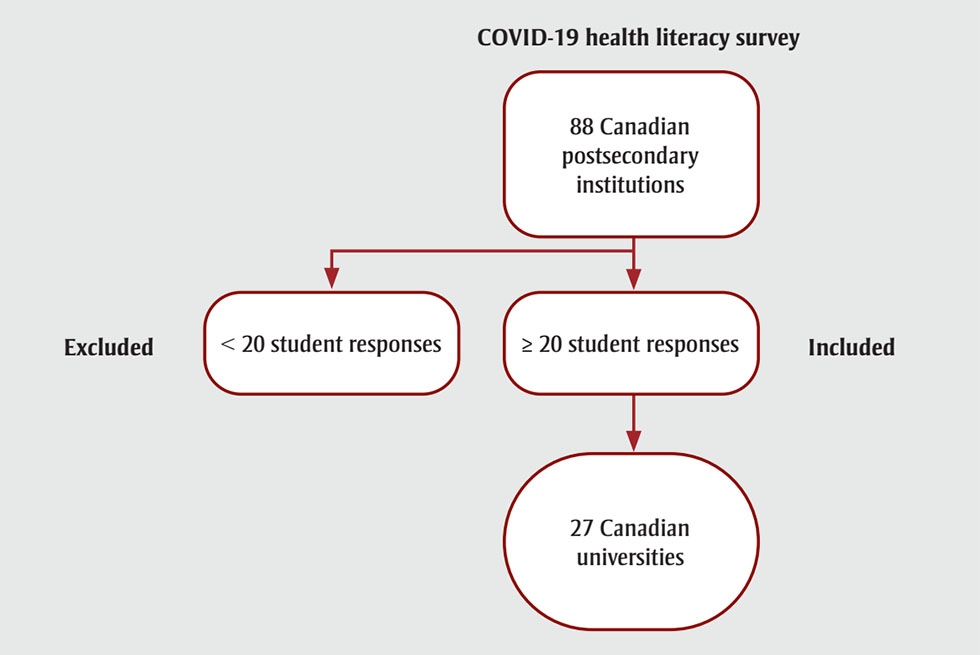

To compare postsecondary institution information sources to those from government public health authorities, we created a framework for deciding which institutions’ web pages to scan. We used the results of our earlier COVID-19 health literacy cross-sectional study as a sampling frame from which to choose a subset of academic institutions to include in our scan. In total, the survey received 2679 responses from students enrolled across 88 Canadian postsecondary institutions (Figure 1).Footnote 5 We specifically limited the institutions searched to those from which at least 20 students enrolled at the academic institution had responded (while institutions themselves were not recruited to participate in the survey, students from different institutions were able to voluntarily respond). This cut-off value narrowed our scans to observing the pandemic-related information published by 27 Canadian universities aimed at their students, and consequently resulted in the exclusion of any Canadian colleges due to a lower response rate from college students.

Figure 1 - Text description

This figure shows the inclusion and exclusion of postsecondary institutions in the systematic scan. The COVID-19 health literacy survey was administered in 88 Canadian postsecondary institutions. Any institution in which less than 20 student responses were received were excluded, and those with 20 or more student responses were included, for a result of 27 Canadian universities.

- Footnote a

-

The COVID-19 health literacy survey was administered to students in Canadian postsecondary institutions from July to September 2020.Footnote 5

Next, we determined keywords to identify relevant web pages from this subset of universities. The search terms were: [institution name], “COVID-19” and “student”, which were input into the Google search engine. The time frame for scanning universities was between November 2020 and January 2021. We then developed a guideline for the kinds of common information to extract and observe from each university, namely the institution’s response strategies, frequently asked questions (FAQ), sources of expertise, and branding approaches (Table 1). These selected items were also used to provide a side-by-side comparison of the universities’ responses to the pandemic directives by federal and provincial governments, through the listing of provincial and local sources of expertise and any additional public sector agencies or public health bodies on their web pages.

| Item | Description | Universities that used these items on their web pages |

|---|---|---|

| Response strategies | ||

| Campus closures and restrictions | Institution-initiated, campus-related changes in response to the pandemic, including the implementation of physical distancing practices, closures or restrictions on campus facilities and services, and shifts to remote learning | Simon Fraser University,Footnote 17Footnote 20Footnote 21 University of British Columbia,Footnote 18 University of Victoria,Footnote 19 Brandon University,Footnote 22 University of Calgary,Footnote 23 University of Alberta,Footnote 24 University of Lethbridge,Footnote 25 Mount Royal University,Footnote 26 University of Winnipeg,Footnote 27 University of Saskatchewan,Footnote 28 University of Manitoba,Footnote 29 University of Waterloo,Footnote 30 University of Toronto,Footnote 31Footnote 32 University of Ottawa,Footnote 33 York University,Footnote 34 Lakehead University,Footnote 35 Western University,Footnote 36 McMaster University,Footnote 37 Queen’s University,Footnote 38 University of Guelph,Footnote 39 Brock University,Footnote 40 Laurentian University,Footnote 41 Ryerson University,Footnote 42 Concordia University,Footnote 43 McGill University,Footnote 44 Acadia University,Footnote 45 Dalhousie UniversityFootnote 46 |

| COVID-19 updates and information pages | Web pages published by individual universities citing COVID-19-related information and providing students with updates to the new academic term and remote learning strategies, public health measures in place on campus and additional health tips and resources | |

| COVID-19 FAQ | Community-specific FAQ organized based on inquiries from students as well as faculty and staff | |

| COVID-19 roadmaps | Detailed plans and steps for returning to campus, in line with government and public health authorities’ advice | Simon Fraser University,Footnote 17Footnote 20Footnote 21 University of Lethbridge,Footnote 25 University of Toronto,Footnote 31Footnote 32 University of Ottawa,Footnote 33 York University,Footnote 34 Acadia UniversityFootnote 45 |

| Campus case trackers | Information on locations and buildings on campus at which there was a confirmed positive case | University of Calgary,Footnote 23University of Manitoba,Footnote 29 Queen’s University,Footnote 38 University of Guelph,Footnote 39 McGill University,Footnote 44 Acadia UniversityFootnote 45 |

| Screening tools and self-assessment forms | Tools initiated for assessing oneself regarding signs or symptoms that may require self-isolation | Simon Fraser University,Footnote 17Footnote 20Footnote 21University of Lethbridge,Footnote 25 University of Toronto,Footnote 31Footnote 32 University of Guelph,Footnote 39 Brock University,Footnote 40 Laurentian University,Footnote 41 Ryerson University,Footnote 42 McGill UniversityFootnote 44 |

| Instructional videos | Videos entailing detailed instructions for safety protocols enacted on campus and how to effectively follow them | University of Saskatchewan,Footnote 28 University of Toronto,Footnote 31Footnote 32 Western UniversityFootnote 36 |

| Training courses | E-courses on adhering to safety protocols following public health guidance | University of Alberta,Footnote 24 University of Guelph,Footnote 39 McGill UniversityFootnote 44 |

| Chat features | Live chat functions were available for queries about the pandemic | Laurentian UniversityFootnote 41 |

| Sources of expertise: federal public health authorities | ||

| Government of Canada, PHAC | Simon Fraser University,Footnote 17Footnote 20Footnote 21 University of British Columbia,Footnote 18 University of Victoria,Footnote 19 Brandon University,Footnote 22 University of Calgary,Footnote 23 University of Alberta,Footnote 24 University of Lethbridge,Footnote 25 Mount Royal University,Footnote 26 University of Winnipeg,Footnote 27 University of Saskatchewan,Footnote 28 University of Manitoba,Footnote 29 University of Waterloo,Footnote 30 University of Toronto,Footnote 31Footnote 32 University of Ottawa,Footnote 33 York University,Footnote 34 Lakehead University,Footnote 35 Western University,Footnote 36 McMaster University,Footnote 37 Queen’s University,Footnote 38 University of Guelph,Footnote 39 Brock University,Footnote 40 Laurentian University,Footnote 41 Ryerson University,Footnote 42 Concordia University,Footnote 43 McGill University,Footnote 44 Acadia University,Footnote 45 Dalhousie UniversityFootnote 46 | |

| Provincial public health authorities | ||

| Government of British Columbia, British Columbia Centre for Disease Control | Simon Fraser University,Footnote 17Footnote 20Footnote 21 University of British Columbia,Footnote 18 University of Victoria,Footnote 19 | |

| Government of Alberta | University of Calgary,Footnote 23 University of Alberta,Footnote 24 University of Lethbridge,Footnote 25 Mount Royal University,Footnote 26 | |

| Government of Saskatchewan | University of Saskatchewan,Footnote 28 | |

| Government of Manitoba | Brandon University,Footnote 22 University of Winnipeg,Footnote 27 University of ManitobaFootnote 29 | |

| Government of Ontario, Public Health Ontario | University of British Columbia,Footnote 18 University of Victoria,Footnote 19 University of Waterloo,Footnote 30 University of Toronto,Footnote 31Footnote 32 University of Ottawa,Footnote 33 York University,Footnote 34 Western University,Footnote 36 McMaster University,Footnote 37 Brock University,Footnote 40 Laurentian University,Footnote 41 Ryerson University,Footnote 42 | |

| Quebec Public Health | Queen’s University,Footnote 38 Concordia UniversityFootnote 43 | |

| Government of Nova Scotia | Acadia University,Footnote 45 Dalhousie UniversityFootnote 46 | |

| Local public health authorities | ||

| Toronto Public Health | University of Toronto,Footnote 31Footnote 32 York University,Footnote 34 Ryerson University,Footnote 42 | |

| Region of Waterloo Public Health | University of Waterloo,Footnote 30 | |

| Thunder Bay District Health Unit | Lakehead University,Footnote 35 | |

| Simcoe Muskoka District Health Unit | Lakehead University,Footnote 35 | |

| Middlesex-London Health Unit | Western University,Footnote 36 | |

| KFL&A Public Health | Queen’s University,Footnote 38 | |

| Wellington-Dufferin-Guelph Public Health | University of Guelph,Footnote 39 | |

| Niagara Region Public Health | Brock University,Footnote 40 | |

| Prairie Mountain Health | Brandon University,Footnote 22 | |

| Branding approaches | ||

| Hashtags | Branding approaches included the use of hashtags for individual universities with the goal of fostering connection while still physically apart, and staying informed (included #UTogether, #YU Better Together, #TakeCareWesternU Toolkit) | University of Toronto,Footnote 31Footnote 32 York University,Footnote 34 Western UniversityFootnote 36 |

Abbreviations: FAQ, frequently asked questions; KFL&A, Kingston, Frontenac, Lennox and Addington; PHAC, Public Health Agency of Canada. |

||

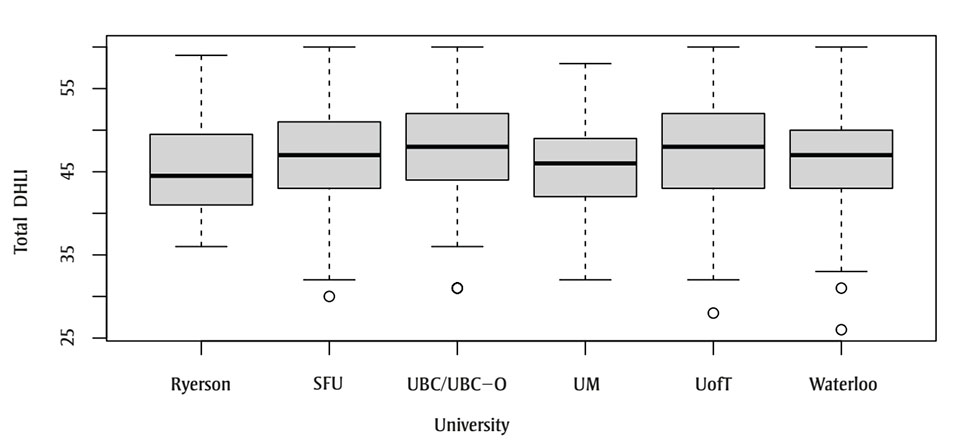

To better understand how the mirroring of official resources by academic institutions may have a role in enhancing student health literacy, we also presented students’ average estimated health literacy from the top four and bottom two universities in our 27-university subsample. The health literacy data was obtained from our earlier COVID-19 health literacy survey study; these estimates were generated in that study by reviewing the responses to health literacy-related questions (Table 2).Footnote 5

| School | DHLI-COVID (N = 1749) Range of possible scores: 15–60 Mean, Median (IQR) |

Satisfaction with COVID information (N = 1889) Range: 1–5 (1 = very dissatisfied; 5 = very satisfied) Mean, Median (IQR) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | Median | Mean | Median | |

| Simon Fraser University | 47.1 | 47.0 (43.0–51.0) | 3.6 | 4.0 (3–4) |

| University of Waterloo | 46.5 | 47.0 (43.0–50.0) | 3.7 | 4.0 (3–4) |

| University of British Columbia | 48.1 | 48.0 (44.0–52.0) | 3.6 | 4.0 (3–4) |

| University of Toronto | 47.6 | 48.0 (43.0–52.0) | 3.6 | 4.0 (3–4) |

| Ryerson University | 45.6 | 44.5 (41.0–49.5) | 3.6 | 4.0 (3–4) |

| University of Manitoba | 46.4 | 46.0 (42.0–49.0) | 3.8 | 4.0 (3–4) |

Abbreviations: DHLI, digital health literacy instrument; IQR, interquartile range. |

||||

We further grouped the 27 universities included in the scan by region: three universities in the West Coast (British Columbia), eight universities from the Prairie Provinces (Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba), 14 universities in Central Canada (Ontario and Quebec), and two universities from the Atlantic Provinces (Nova Scotia) (Table 1).

Results

First, we present our review of four web pages from the federal government and three web pages from the provincial governments of Ontario and British Columbia for information available to the postsecondary student population. Next, we highlight the results from our scan of 27 Canadian universities for the types of web pages used to provide health information about COVID-19 to students.

Federal government: guidance for postsecondary institutions and students

Web pages presented by the Canadian federal government included those on pandemic measures that would affect the general population and thereby students, as well as postsecondary institution–specific information on how to enforce these measures for students on campus. In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, the federal government enacted measures to prevent people with COVID-19 coming in from outside of Canada, including border closures and limiting of nonessential travel, along with mandatory 14-day isolation periods upon entry into the country.Footnote 9Footnote 10Footnote 11

These mandates were followed by guidance for academic institutions during the pandemic, developed by PHAC and Canadian public health experts, directed at postsecondary institution administrators. This guidance outlined a risk-based approach for campus planning and operations to administrators and course providers, taking into consideration factors such as the amount of on-campus COVID-19 transmission and domestic and international travel requirements. It also addressed collaboration with local public health authorities in the event of an outbreak, and included recommendations for the timing of school closures and openings.Footnote 12

Federal advice also referred postsecondary institutions to previously issued general guidance for personal preventive measures and community-based measures in mitigating COVID-19 spread in Canada detailing the risk of transmission, which is particularly high in indoor environments with a high density of people, thereby reinforcing the need for campus closures.Footnote 13 Federal guidance further stated that relevant information should be shared by academic institutions with their students.Footnote 12

Provincial government: measures in effect in Ontario and British Columbia

Provincial government web pages also presented safety measures, including those being implemented in classroom settings. We limited the scope of our review of provincial measures to Ontario and British Columbia, mainly due to the geographic location of the institutions of the research team.Footnote 5

Ontario was first declared to be in a state of emergency in March of 2020, when schools and other public establishments were shut down.Footnote 14 The provincial government provided guidance as to when these establishments would be permitted to resume operations, and at what capacity, with restrictions listed in Ontario’s Roadmap to Reopen.Footnote 14Footnote 15

Similarly, the province of British Columbia enacted measures that followed the province’s restart plan: this was founded on principles for moving forward during COVID-19 by staying informed and prepared, and by following public health advice.Footnote 16 During the first phase of this restart plan, a public health state of emergency was declared for the province, limiting operations to essential services; this also resulted in reduced in-classroom learning.Footnote 16

Additional public health messaging issued in both provinces reiterated and encouraged the practice of good hygiene and safety measures through mask-wearing and physical distancing.Footnote 15Footnote 16

Scans of universities from the West Coast

The three universities from the Canadian West Coast region—Simon Fraser University, the University of British Columbia and the University of Victoria—referenced recommendations and policies from the BC Centre for Disease Control, the provincial government of British Columbia and PHAC for planning their university operations and pandemic measures for students, staff and faculty members.Footnote 17Footnote 18Footnote 19 Each institution had published similar web pages in terms of the content and resources dedicated to COVID-19 information, and each had included pages for students’ FAQ. They also provided links to additional resources, including British Columbia government COVID-19 self-assessment tools and mandatory isolation policies, as well as links for student health and well-being that allowed students to both give and receive support during COVID-19 outbreaks.Footnote 17Footnote 18Footnote 19Footnote 20Footnote 21

Scans of universities from the Prairie Provinces

The eight universities in the Prairie Provinces region were Brandon University, the University of Calgary, the University of Alberta, the University of Lethbridge, Mount Royal University, the University of Winnipeg, the University of Saskatchewan and the University of Manitoba.Footnote 22Footnote 23Footnote 24Footnote 25Footnote 26Footnote 27Footnote 28Footnote 29 These institutions cited similar recommendations made by PHAC, as well as recommendations set by their respective regional health authorities and provincial bodies (e.g. ministries of health).Footnote 22Footnote 23Footnote 24Footnote 25Footnote 26Footnote 27Footnote 28Footnote 29 The COVID-19 web pages published by these institutions included information on campus operations and updates, FAQ and self-assessment and prevention tools. As with the other universities, students are required to complete health declaration forms prior to accessing campus facilities.Footnote 22Footnote 23Footnote 24Footnote 25Footnote 26Footnote 27Footnote 28Footnote 29

Scans of universities from Central Canada

The 14 universities from Central Canada were the University of Waterloo, the University of Toronto, the University of Ottawa, York University, Lakehead University, Western University, McMaster University, Queen’s University, the University of Guelph, Brock University, Laurentian University, Ryerson University, Concordia University and McGill University.Footnote 30Footnote 31Footnote 32Footnote 33Footnote 34Footnote 35Footnote 36Footnote 37Footnote 38Footnote 39Footnote 40Footnote 41Footnote 42Footnote 43Footnote 44 These institutions also referenced guidelines provided by PHAC, and additionally adhered to the recommendations from their respective regional health authorities or public health units (in the case of Ontario-based academic institutions) for campus operations, international travel policies and COVID-19 measures.Footnote 30Footnote 31Footnote 32Footnote 33Footnote 34Footnote 35Footnote 36Footnote 37Footnote 38Footnote 39Footnote 40Footnote 41Footnote 42Footnote 43Footnote 44 These institutions created web pages for FAQ regarding COVID-19, newly implemented campus protocols and self-assessment tools. Additional resources provided by these institutions were mental health portals designed to help students adapt to the challenges introduced by the pandemic.Footnote 30Footnote 31Footnote 32Footnote 33Footnote 34Footnote 35Footnote 36Footnote 37Footnote 38Footnote 39Footnote 40Footnote 41Footnote 42Footnote 43Footnote 44

Scans of universities from the Atlantic Provinces

The two universities from the Atlantic Provinces were Acadia University and Dalhousie University.Footnote 45Footnote 46 These two institutions followed and referenced notices from the Government of Nova Scotia, and created pages for campus updates on the pandemic and future university reopening plans, as well as student health and safety resources and FAQ.Footnote 45Footnote 46

Survey results

Using the data from the earlier COVID-19 health literacy survey for the top four (Simon Fraser University, the University of Waterloo, the University of British Columbia and the University of Toronto) and bottom two (Ryerson University and the University of Manitoba) institutions of our 27-university sample, we determined the average response for six questions (Table 2). Five questions (numbered 14 to 18 on the survey) related to digital health literacy, and one (question 23) gauged satisfaction with online COVID-19 information (Table 3).Footnote 5 The averages of the responses to each of the six questions were compared across the given institutions, and no significant difference was observed for either digital health literacy or for satisfaction with COVID-19. Findings from the scans of institutions’ web pages showed that they similarly followed government guidelines and had similar coronavirus-related resources available for their students.

Table 3. COVID-19 health literacy surveyFootnote a questions 14 to 18 and 23

Q14. When you search the Internet for information on the coronavirus or related topics, how easy or difficult is it for you to… (on a scale from very easy, easy, difficult, very difficult):

... make a choice with all the information you find?

... use the proper words or search query to find the information you are looking for?

… find the exact information you are looking for?

Q15. When typing a message (e.g. on a forum, or on social media such as Facebook or Twitter) about the coronavirus or related topics, how easy or difficult is it for you to... (on a scale from very easy, easy, difficult, very difficult):

... clearly formulate your question or health-related worry?

... express your opinion, thoughts or feelings in writing?

... write your message as such, for people to understand exactly what you mean?

Q16. When you search the Internet for information on the coronavirus or related topics, how easy or difficult is it for you to... (on a scale from very easy, easy, difficult, very difficult):

... decide whether the information is reliable or not?

... decide whether the information is written with commercial interests (e.g. by people trying to sell a product)?

... check different websites to see whether they provide the same information?

Q17. When you search the Internet for information on the coronavirus or related topics, how easy or difficult is it for you to... (on a scale from very easy, easy, difficult, very difficult):

... decide if the information you found is applicable to you?

... apply the information you found in your daily life?

... use the information you found to make decisions about your health (e.g. on protective measures, hygiene regulations, transmission routes, risks and their prevention)?

Q18. When you post a message about the coronavirus or related topics on a public forum or social media, how often... (on a scale from never, once, several times, often):

... do you find it difficult to judge who can read along?

... do you (intentionally or unintentionally) share your own private information (e.g. name or address)?

... do you (intentionally or unintentionally) share someone else’s private information?

Q23. How satisfied are you with the information you find on the Internet about coronavirus (on a scale from very dissatisfied, dissatisfied, partly satisfied, satisfied, very satisfied)?

- Footnote a

-

The COVID-19 health literacy survey was administered to students in Canadian postsecondary institutions from July to September 2020.Footnote 5

Discussion

The COVID-19 pandemic has been a primary focus of research due to its widespread impacts; however, a relatively small portion of this research has focussed on pandemic-related health literacy, specifically among postsecondary students. Due to the shift to remote, online learning across many Canadian academic institutions, postsecondary students would be expected to have increased exposure to both credible and less reliable online claims about COVID-19.

It is crucial for reliable sources such as public health bodies and postsecondary institutions to continue to distribute accurate health information to counter misinformation. There is a correlation between professional encouragement and preventive behaviour in university students. One Canadian study found students were 76 times more likely to willingly receive COVID-19 vaccines once available if they had been encouraged by medical professionals as opposed to other students that had not received advice from their doctor or pharmacist, or if they had unaddressed concerns about the safety and efficacy of the COVID-19 vaccines.Footnote 47 This study further substantiated the importance of regularly communicating accurate COVID-19 health information, as health communication can correlate with the uptake of coronavirus vaccines among the university student population.Footnote 47

For this reason, we examined the kinds of resources made available to postsecondary students searching for coronavirus-related information. This included publicly available information from government bodies and web pages of postsecondary institutions, since students may rely on them as a resource for disease-related information and campus restrictions and protocols.

In scanning the information published by federal and provincial governments in Canada, we noted that both had taken measures to ensure the health and safety of the general population in terms of reducing viral transmissions. The changes that would directly affect postsecondary students and institutions were the closures of academic institutions. The provinces of Ontario and British Columbia both created frameworks for reopening each province after a reduction in case counts, which listed already implemented restrictions and plans for the future, and drew attention to the importance of communicating up-to-date information.Footnote 15Footnote 16

The federal government created a web page for guidance and recommendations directed specifically toward postsecondary institutions regarding changes across campus that should be made in response to the pandemic and recommended to these institutions that they share relevant information with their students, but did not have information specifically addressing students.Footnote 12 This may be because education is a provincial jurisdictional responsibility. While this web page provided recommendations for campus-related changes, further guidance should be provided by government to institutions on how to monitor and enforce the changes.

A majority of the students who participated in the COVID-19 health literacy survey reported high levels of health literacy, with 52.6% finding it “easy” and 30.4% finding it “very easy” to use online health information to make health-related decisions (Table 3, Figure 2).Footnote 5 This level of ease could be attributed to the accessibility and availability of health information from public bodies. These sources are also relayed by postsecondary institutions; the survey showed that a high proportion of students use official government sources to obtain health information about the pandemic. In scanning information published by postsecondary institutions, we found these scans showed alignment with the frequently used sources by students in accessing COVID-19 information, as they mirrored the information and directives available on the websites of government bodies, including safety and distancing protocols, recommended closures of buildings on campus and links directing users to additional resources published by these official bodies.

Figure 2. Postsecondary student digital health literacy and satisfaction with institution’s COVID-19 information, COVID-19 health literacy survey, by university, July to September 2020

Figure 2A - Text description

| School | DHLI-COVID (N = 1749) Range of possible scores: 15–60 |

|

|---|---|---|

| Mean | Median | |

| Ryerson University | 45.6 | 44.5 (41.0–49.5) |

| Simon Fraser University | 47.1 | 47.0 (43.0–51.0) |

| University of British Columbia | 48.1 | 48.0 (44.0–52.0) |

| University of Manitoba | 46.4 | 46.0 (42.0–49.0) |

| University of Toronto | 47.6 | 48.0 (43.0–52.0) |

| University of Waterloo | 46.5 | 47.0 (43.0–50.0) |

Figure 2B - Text description

| School | Satisfaction with COVID information (N = 1889) Range: 1–5 (1 = very dissatisfied; 5 = very satisfied) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Mean | Median | |

| Ryerson University | 3.6 | 4.0 (3–4) |

| Simon Fraser University | 3.6 | 4.0 (3–4) |

| University of British Columbia | 3.6 | 4.0 (3–4) |

| University of Manitoba | 3.8 | 4.0 (3–4) |

| University of Toronto | 3.6 | 4.0 (3–4) |

| University of Waterloo | 3.7 | 4.0 (3–4) |

Abbreviations: DHLI, digital health literacy instrument; SFU, St. Francis Xavier University; UBC/UBC-O, University of British Columbia/University of British Columbia-Okanagan; UM, University of Manitoba; UofT, University of Toronto.

Notes: Data are from cross-sectional survey of Canadian university students’ COVID-19 health literacy.Footnote 5 Only the top four and bottom two schools of a 27-school subsample (ranking for digital health literacy) are shown here. Error bars indicate confidence intervals.

In particular, we found that all of these institutions similarly sourced the Government of Canada and related public health authorities such as PHAC for COVID-19 information. The major contrasts that we noticed regarding sources of expertise across these web pages mainly consisted of the institutions’ references to provincial and municipal bodies, which is to be expected since many of the institutions are located in different regions across Canada.

In terms of the universities’ response strategies and branding approaches, we noted that universities mainly differed in the methods used for providing information, but maintained the same goal of educating their students on the pandemic and ensuring safety. All of the observed universities had created main pages for COVID-19 information with links navigating to additional resources, including updates, the universities’ responses and FAQ. The universities’ strategies for providing information began branching when it came to other resources available to students. For example, some universities provided self-screening tools to determine whether one might be at risk or health-compromised and should self-isolate, while other universities instead opted for online campus case trackers to alert their students to locations where there were confirmed cases of COVID-19 and suggesting students isolate if they had been at these locations during the time of exposure.

Other differences included the universities’ use of instructional videos versus training courses to inform their students of current public health guidelines and how to effectively follow these protocols on campus, and the use of different social media hashtags to tailor information to their own students and maintain a sense of connection while apart during the pandemic.

Strengths and limitations

This study provides insight into the kinds of publicly accessible sources of COVID-19 health information made available to postsecondary students by government and academic institutions. As the scans were conducted between September 2020 and January 2021, it provides contextual information on the Canadian public health policy environment during the COVID-19 pandemic. Furthermore, by comparing our findings with our earlier health literacy survey results, we found evidence of some congruence between the behaviours of postsecondary institutions and those of the students, in that they both referred back to government policies for university responses and COVID-19 information.

However, some limitations should be noted. These include the lack of consistently available information during the pandemic, as responses from federal and provincial governments and regional health authorities were still unstable due to the rapid release of new COVID-19-related information. The provincial web page scans are further limited, as we only observed information from the provinces of Ontario and British Columbia.

In addition, our scans of postsecondary institutions and the measurements of health literacy may have been subject to sampling bias, as a majority of the respondents to the health literacy survey were students in the health field, which may have resulted in an overestimation of health literacy levels among postsecondary students. Similarly, a sampling bias may have also stemmed from the exclusion of colleges within our scanning frame, as there were not enough responses from colleges to meet our sampling threshold. The use of Google (a commercial database) as the sole search engine for our study may have led to selection bias through the indexing of web pages. The visual presentation of information, such as the positioning and/or use of infographics by different university web pages, was not explored in this study, although how information is presented and the ease of navigation through a web page can also impact health literacy.

Despite these limitations, this study provides novel insights into the online health resources available to university students, and into students’ health literacy levels.

Conclusion

Overall, we examined 27 universities in this study and found that these institutions followed the same guidelines from the federal government, including from agencies such as PHAC, as well as their respective provincial government and local health authorities, for campus operations, COVID-19 measures and enhancement of health literacy among their students. Greater health literacy levels in this student population would encourage adherence to the current pandemic public health measures such as physical distancing, mask-wearing and vaccination, which directly relate to minimizing the spread of COVID-19. The Canadian government and Canadian postsecondary institutions should continue to provide easily accessible and verified up-to-date information to their students to assist in curbing the spread of COVID-19 and reducing health care burdens.

This study helped to identify the online information-seeking behaviours of university students, and how information published by the government and by universities promotes access to credible online health resources. Future research is needed to address the limitations mentioned above, and to include local public health information.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the postsecondary students who took part in the study survey.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Authors’ contributions and statement

EDR and PA completed the study conceptualization. SM, JF, HE and SP performed the data collection and analysis, and EDR and PA reviewed the interpretation of results. SM, JF, EDR and PA wrote the manuscript draft. EDR and PA reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors approved the final version of the manuscript before submission.

The content and views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Government of Canada.