Original quantitative research – Sentinel surveillance of injuries and poisonings associated with cocaine and other substance use: results from the Canadian Hospitals Injury Reporting and Prevention Program (CHIRPP)

HPCDP Journal Home

Published by: The Public Health Agency of Canada

Date published: July 2022

ISSN: 2368-738X

Submit a manuscript

About HPCDP

Browse

Ithayavani Iynkkaran, PhDAuthor reference footnote 1; Sarah Zutrauen, BHScAuthor reference footnote 1; Sofiia Desiateryk, BScAuthor reference footnote 1; Ze Wang, BScAuthor reference footnote 1; Lina Ghandour, MScAuthor reference footnote 2; Steven R. McFaull, MScAuthor reference footnote 3; André Champagne, MPHAuthor reference footnote 3; James CheesmanAuthor reference footnote 3; Minh T. Do, PhDAuthor reference footnote 1Author reference footnote 2Author reference footnote 4

https://doi.org/10.24095/hpcdp.42.7.01

This article has been peer reviewed.

Author references

Correspondence

Minh T. Do, Department of Health Sciences, Carleton University, 2305 Health Sciences Building, 1125 Colonel By Drive, Ottawa, ON K1S 5B6; Tel: 613-901-9632; Email: minh.do@carleton.ca

Suggested citation

Iynkkaran I, Zutrauen S, Desiateryk S, Wang Z, Ghandour L, McFaull SR, Champagne A, Cheesman J, Do MT. Sentinel surveillance of injuries and poisonings associated with cocaine and other substance use: results from the Canadian Hospitals Injury Reporting and Prevention Program (CHIRPP). Health Promot Chronic Dis Prev Can. 2022;42(7):263-71. https://doi.org/10.24095/hpcdp.42.7.01

Abstract

Introduction: Consumption of cocaine can lead to numerous injuries and poisoning. However, only a limited number of studies have explored cocaine-related injuries. This study examined a wide range of injuries and poisonings related to cocaine only and in combination with other substances in Canada using sentinel surveillance data captured by the electronic Canadian Hospitals Injury Reporting and Prevention Program (eCHIRPP).

Methods: Injuries and poisonings related to the use of cocaine only or in combination with other substances were identified in the eCHIRPP database between January 2012 and December 2019 for all ages. Descriptive analyses were performed to investigate the distribution of demographic and injury characteristics in poisoning and injury records related to the use of cocaine only and in combination with other substances. Statistical analyses were conducted to find the proportion of cocaine-related injuries per 100 000 eCHIRPP records. Cocaine-related injury trends were assessed using annual percent change (APC).

Results: Cocaine-related injuries and poisonings were observed in 123 records per 100 000 eCHIRPP records. Of the 1482 patients who presented to emergency departments of CHIRPP sites with this type of injury or poisoning, the majority involved cocaine use in combination with one or more substances (80.0%; n = 1186), whereas cocaine-only use was the minority (20.0%; n = 296). Among all cocaine-related records, poisoning was the leading diagnosis (62.7%; n = 930) and most injuries and poisonings were unintentional (73.5%; n = 1090). Overall, the trend of cocaine-related eCHIRPP records for all age groups increased over the study period from 2012 to 2019 (APC [total] = 47.8%, p < 0.05).

Conclusion: Our findings of a higher proportion of cocaine-related injuries and poisonings among adolescents and young adults, as well as the co-consumption of cocaine with other substances, demonstrate the importance of extensive surveillance of cocaine-related injuries and poisonings and the implementation of evidence-based public health interventions.

Keywords: cocaine, cocaine-related injuries and poisonings, co-consumption, emergency department, Canadian Hospitals Injury Reporting and Prevention Program

Highlights

- There were 123 records of cocaine-related injuries and poisonings per 100 000 eCHIRPP records identified in the eCHIRPP database between January 2012 and December 2019 for all age groups.

- The majority of injuries and poisonings occurred when cocaine was used in combination with one or more substances (80.0%; n = 1186).

- The proportion of cocaine-related injuries and poisonings was generally higher among males across most age groups compared to females, except for females under 19 years of age, who represented a slightly higher proportion than males in the same age group.

- The overall trend of cocaine-related records for all age groups showed an increase over the study period from 2012 to 2019 (APC [total] = 47.8%, p < 0.05).

- Among all cocaine-related records, poisoning was the leading diagnosis (62.7%; n = 930).

Introduction

In Canada, as in many parts of the world, substance use and addiction are significant public health problems. The Canadian Substance Use Costs and Harms 2015–2017 report indicated that in 2017, substance use cost Canadians approximately CAD 46 billion, both directly and indirectly, and led to 275 000 hospitalizations and nearly 75 000 deaths.Footnote 1 According to the Government of Canada, psychoactive substances, such as alcohol, tobacco, prescription medications and cannabis, are most commonly used by Canadians, while other psychoactive substances that are illicit, such as cocaine, heroin, ecstasy and methamphetamine, are used by a smaller number of Canadians at some point in their lifetime.Footnote 2

Cocaine is regulated under Canada’s Controlled Drugs and Substances Act.Footnote 3 The criminal penalty for possession of cocaine can be as many as seven years of imprisonment, while production and trafficking can lead to lifetime imprisonment. Despite these regulatory measures, Canada ranks second in the world for the median number of days of cocaine use among those who reported using cocaine in the previous 12 months, according to the Global Drug Survey 2019.Footnote 4 Furthermore, the 2017 Canadian Tobacco, Alcohol and Drugs Survey (CTADS) found that around 2% of the Canadian population were using cocaine, compared to 1% in 2015.Footnote 5Footnote 6 This survey further revealed that cocaine was the third most prevalent substance consumed after alcohol and cannabis (besides tobacco) among those 19 years of age and older.Footnote 5Footnote 6Footnote 7 In addition, according to the Canadian Student Tobacco, Alcohol and Drugs Survey (CSTADS), an estimated 2.2% of students in Grades 7 to 12 reported cocaine use in 2018-2019; among these students, those in Grades 10 to 12 reported the highest cocaine use (3.4%).Footnote 8

Cocaine, a powerful nerve stimulant and an addictive substance, is derived from coca leaves. It is a popular street drug also known as “coke,” “blow,” “crack,” “snow” and “Charlie,” among others.Footnote 9 Cocaine users may consume it by snorting it directly into the nose, rubbing it on their gums, dissolving it in water and injecting it, or smoking it. The consumption of cocaine increases energy and alertness, lowers appetite and sleep and generates intense feelings of euphoria.Footnote 10 Evidence indicates that cocaine use is associated with short- and long-term health risks to multiple organs, such as the brain, heart, lungs, liver and kidneys.Footnote 11 Another major concern about using cocaine, a sympathomimetic and psychoactive substance, is that it can impact the drug user’s cognitive ability and judgment, which could lead to fatal or nonfatal injuries.Footnote 12Footnote 13 Furthermore, consuming cocaine alongside other drugs is a common practice among street drug users.Footnote 14 Polysubstance use, such as illicit drugs with alcohol or other substances, can lead to physical, behavioural and health complications.Footnote 15

So far, cocaine research has focussed on drug overdose deaths, trauma and fatal injuries involving cocaine. Nevertheless, injuries and poisonings associated with cocaine use among the Canadian population have not been studied well. Considering the rapid increase in harms associated with cocaine use in CanadaFootnote 1 and the small number of studies that have explored cocaine-related injuries, the objective of our study was to examine the various injuries and poisonings related to cocaine and other substance use among Canadians using sentinel surveillance data captured from January 2012 to December 2019 by the electronic Canadian Hospitals Injury Reporting and Prevention Program (eCHIRPP).

Methods

Data source

The eCHIRPP is an injury and poisoning sentinel surveillance system that collects and analyzes data on injuries and poisonings of patients who visit the emergency departments (EDs) of 11 pediatric hospitals and 9 general hospitals across Canada.Footnote 16 During their visit to the ED of a participating CHIRPP hospital, the injured person or the accompanying caregiver is asked to complete a questionnaire about the injury circumstances.Footnote 17 The attending physician or other hospital staff later adds clinical details of the injury. These data are entered into the secure, web-based eCHIRPP database by the CHIRPP site coordinators. Narratives of injury information given by the patients or caregivers are extracted by data coders from the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC). Data from the eCHIRPP database were initially queried for injuries and poisonings related to the use of cocaine occurring between April 2011 and July 2020 for all ages.

Cocaine-related records were identified using search terms such as “cocaine”, “crack cocaine”, “coke”, “blow”, “free base”, “crack”, “snow”, and “Charlie” in the substance ID and the narrative description of the injury/poisoning event in the eCHIRPP database, and were confirmed manually. A total of 1629 cocaine-related injuries and poisonings were reported in the eCHIRPP database between April 2011 and July 2020. We excluded records from the years 2011 and 2020, as these were incomplete. This reduced the cocaine-related records to 1482, representing 123.1 records per 100 000 eCHIRPP records.

Injuries associated with cocaine use were characterized into two distinct categories based on substance ID, diagnosis and manual review of the narrative description: cocaine-only and cocaine with one or more substances.Footnote 18 To identify potential drug combinations used with cocaine, cocaine with one or more substances was further stratified into subcategories such as cocaine and alcohol, cocaine and cannabis, cocaine and other illicit drugs, cocaine and medications (over the counter or prescription-based), and cocaine and mixed substances (i.e. more than one specified category was used with cocaine).

To explore the characteristics of the location variable, cocaine-related records were categorized based on two classifications: rural or urban and indoor or outdoor. Though substance use was often perceived to occur at parties, recreational places or outdoors, surveys found it occurred mostly at a person’s own home or another’s home. Therefore, to investigate these findings (i.e. the specific locations of injury event), indoor and outdoor settings were further characterized into subcategories.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive analyses were performed to investigate the distribution of demographic and injury characteristics (such as sex, age, location—rural/urban, location—indoor/outdoor, nature of injury, intent and disposition) of associated cocaine and other substance-related poisoning and injury records. Frequency distributions such as counts and percentages were generated, and data were presented overall and stratified by cocaine-only and cocaine-related substance use. Cocaine-related proportions were calculated relative to 100 000 eCHIRPP records by identifying cocaine-related records relative to all records (excluding cocaine-related records) found in the eCHIRPP database. Statistical analyses were conducted using Microsoft Excel 2010 and Joinpoint Regression Program version 4.8.0.1.Footnote 19 Time trend analyses were performed for the study period of January 2012 to December 2019 by sex and age group (15–19 years, 20–29 years, 30 years and older, and all ages) for all cocaine-related and cocaine-only injuries using Joinpoint software. The age group under 15 years was excluded from the time trend analyses due to the small counts. The annual percentage change (APC) and p-values were computed to describe trends over time. APC segments are significantly different from zero at the α = 0.05 level.

Results

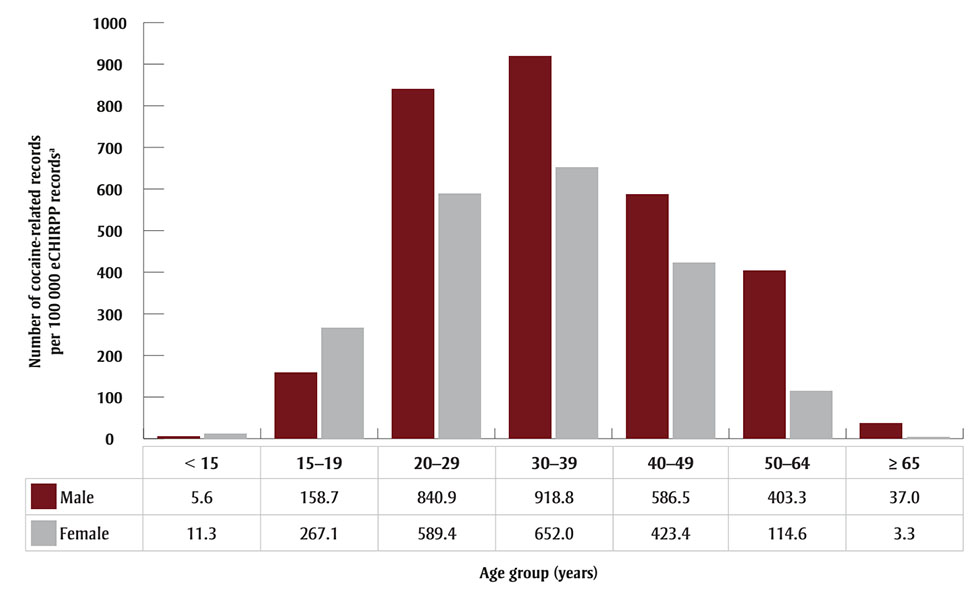

Demographic and injury characteristics of cocaine-related records between 2012 and 2019 are presented in Table 1. Of the 1482 cocaine-related records, the majority involved cocaine use in combination with one or more other substances (80.0%; n = 1186), whereas cocaine-only use occurred in 20.0% of records (n = 296). For both cocaine-only use and cocaine use in combination with one or more substances, males (67.5% and 62.5%, respectively) represented the larger proportion. The number of injury and poisoning records related to cocaine-only use was highest among those aged 30 to 39 years (24.7%, n = 73), whereas the number of records related to the use of cocaine with one or more other substances was highest among those aged 20 to 29 years (32.6%, n = 386). When cocaine-related records were stratified by sex and age to calculate the number of records per 100 000 eCHIRPP records, males accounted for a higher proportion of all cocaine-related records across most age groups, except for those aged less than 15 years and 15 to 19 years; in those groups, females (11.3 and 267.1 records/100 000 eCHIRPP records, respectively) represented a larger proportion compared to males (5.6 and 158.7 records/100 000 eCHIRPP records, respectively; Figure 1).

| Characteristics | All n (%) |

Cocaine only n (%) |

Cocaine with one or more substancesFootnote a n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 1482 (100.0) | 296 (20.0) | 1186 (80.0) |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 941 (63.5) | 200 (67.5) | 741 (62.5) |

| Female | 541 (36.5) | 96 (32.5) | 445 (37.5) |

| Age group (years) | |||

| < 10 | 15 (1.0) | 5 (1.7) | 10 (0.8) |

| 10–14 | 51 (3.4) | 6 (2.1) | 45 (3.8) |

| 15–19 | 294 (19.8) | 37 (12.5) | 257 (21.7) |

| 20–29 | 457 (30.8) | 71 (24.0) | 386 (32.6) |

| 30–39 | 334 (22.5) | 73 (24.7) | 261 (22.0) |

| 40–49 | 179 (12.1) | 60 (20.3) | 119 (10.0) |

| ≥ 50 | 152 (10.3) | 44 (14.9) | 108 (9.1) |

| Location—urban/ruralFootnote b | |||

| Urban | 1271 (85.8) | 254 (85.8) | 1017 (85.7) |

| Rural | 156 (10.5) | 28 (9.5) | 128 (10.8) |

| Location—indoor/outdoor | |||

| Indoor locationsFootnote c | 483 (32.6) | 93 (31.4) | 390 (32.9) |

| Own home | 188 (12.7) | 35 (11.8) | 153 (13.0) |

| Other people’s home | 118 (8.0) | 23 (7.8) | 95 (8.0) |

| Other | 68 (4.6) | 11 (3.7) | 57 (4.8) |

| Outdoor locationsFootnote d | 389 (26.3) | 67 (22.6) | 322 (27.3) |

| Street, highway or public road | 147 (9.9) | 23 (7.8) | 124 (10.5) |

| Public transportation or vehicle | 105 (7.1) | 27 (9.1) | 78 (6.6) |

| Public park | 20 (1.4) | 1 (0.3) | 19 (1.6) |

| Residential | 37 (2.6) | 4 (1.4) | 33 (2.8) |

| Nature of injuriesFootnote e | |||

| Poisoning | 930 (62.7) | 149 (50.3) | 781 (65.8) |

| External wound | 129 (8.7) | 23 (7.8) | 106 (8.9) |

| Fracture, sprain or strain | 104 (7.0) | 26 (8.8) | 78 (6.6) |

| Traumatic brain injury | 61 (4.1) | 12 (4.1) | 49 (4.1) |

| Other injuriesFootnote f | 35 (2.4) | 5 (1.7) | 30 (2.5) |

| Intent of injuries | |||

| Unintentional | 1090 (73.5) | 233 (78.7) | 857 (72.3) |

| Self-harm | 274 (18.5) | 42 (14.2) | 232 (19.6) |

| Physical assault | 79 (5.3) | 14 (4.7) | 65 (5.5) |

| Sexual assault | 17 (1.2) | 1 (0.3) | 16 (1.4) |

| Maltreatment | 17 (1.2) | 2 (0.7) | 15 (1.3) |

| ERP involvement | 5 (0.3) | 4 (1.4) | 1 (0.1) |

| Disposition | |||

| Left without being seen by physician | 47 (3.2) | 20 (6.8) | 27 (2.3) |

| Advice only, diagnostic testing, referred to GP (no treatment in ED) | 111 (7.5) | 27 (9.1) | 84 (7.1) |

| Treated in ED with follow-up PRN | 239 (16.1) | 63 (21.3) | 176 (14.8) |

| Observation in ED, follow-up PRN | 638 (43.1) | 102 (34.5) | 536 (45.2) |

| Observation in ED, follow-up required | 88 (5.9) | 20 (6.8) | 68 (5.7) |

| Treated in ED, follow-up required, referred for injury treatment |

107 (7.2) | 12 (4.1) | 95 (8.0) |

| Admitted to hospital for injury treatment | 199 (13.4) | 38 (12.8) | 161 (13.6) |

| Admitted for other than injury treatment | 45 (3.0) | 11 (3.7) | 34 (2.9) |

Abbreviations: eCHIRPP, electronic Canadian Hospitals Injury Reporting and Prevention Program; ED, emergency department; ERP, emergency response personnel; GP, general practitioner; PRN, as needed.

|

|||

Figure 1 - Text description

| Age group (years) | Male | Female |

|---|---|---|

| <15 | 5.6 | 11.3 |

| 15–19 | 158.7 | 267.1 |

| 20–29 | 840.9 | 589.4 |

| 30–39 | 918.8 | 652.0 |

| 40–49 | 586.5 | 423.4 |

| 50–64 | 403.3 | 114.6 |

| ≥65 | 37.0 | 3.3 |

Abbreviation: eCHIRPP, electronic Canadian Hospitals Injury Reporting and Prevention Program.

a Expressed as a proportion of eCHIRPP records

for each age group (× 100 000).

Cocaine-only incidents and incidents involving cocaine with one or more substances had similar distributions in rural (9.5% vs. 10.8%) and urban (85.8% vs. 85.7%) settings. There were 483 incidents related to cocaine use at indoor locations, the highest proportion of which occurred at the patient’s own home (n = 188). Conversely, cocaine-related injuries that occurred outdoors (n = 389) frequently took place on streets, highways or public roads (n = 147; Table 1).

Poisoning (62.7%) was the leading nature of injury among all cocaine-related records, followed by external wound (8.7%), fracture, sprain or strain (7.0%), brain injury (4.1%), and other injuries (2.4%; Table 1). With regard to the intent of injuries, unintentional injuries were the most frequent (73.5%), while self-harm (18.5%) was found to be the second most common. Most patients were observed in the ED with follow-up as needed (43.1%, n = 638; Table 1), while 199 (13.4%) patients were admitted to hospital for injury treatment, the majority of which were males (n = 139), and patients aged 20 to 29 years (n = 65). There were 45 (3.0%) patients admitted for reasons other than injury treatment.

As shown in Figure 2, the majority of patients consumed cocaine with mixed substances (i.e. more than one substance, including alcohol, cannabis, illicit drugs or medication; n = 457) followed by cocaine and alcohol (n = 417). There were more male patients than female across all substance categories (Figure 2).

Figure 2 - Text description

| Gender | Type of substance use | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cocaine only | Cocaine and alcohol | Cocaine and cannabis | Cocaine and other illicit drugs | Cocaine and medications | Cocaine and mixed substances | |

| Male | 200 | 256 | 43 | 136 | 20 | 286 |

| Female | 96 | 161 | 15 | 81 | 17 | 171 |

Abbreviation: eCHIRPP, electronic Canadian

Hospitals Injury Reporting and Prevention Program.

Note: “Mixed substances” refers to more than one specified

substance category use with cocaine.

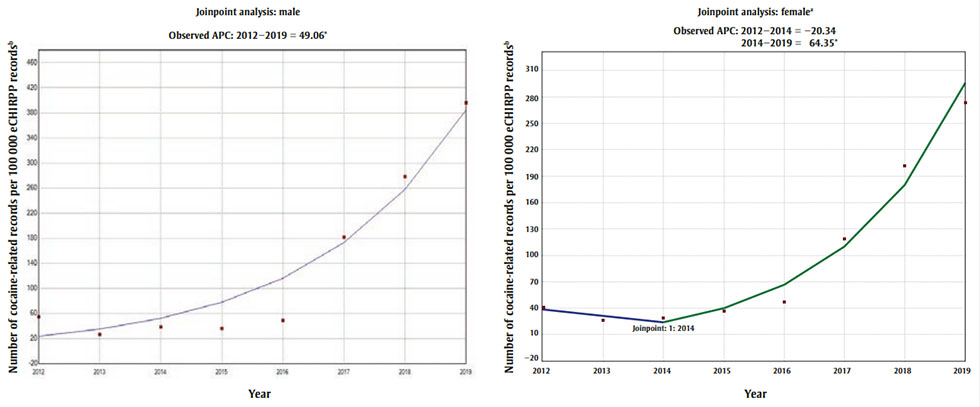

The time trend for cocaine-related injuries and poisonings, by sex, for the period between January 2012 and December 2019, is shown in Figure 3. For males, there was a slight decrease from 2012 to 2013 and 2014 to 2015, followed by an increasing trend from 2015 to 2019. The Joinpoint analysis software did not identify significant inflection points, and the overall trend for males was represented by an increasing APC of 49.1% (p < 0.05). For females, the Joinpoint analysis software identified a decreasing trend from 2012 to 2014 (APC = −20.3%, p > 0.05) and an increasing trend from 2014 to 2019 (APC = 64.3%, p < 0.05). A significant inflection point occurred in 2014 for females (Figure 3).

Figure 3 - Text description

| Year | Number of cocaine-related records per 100 000 eCHIRPP recordsFootnote b | |

|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | |

| 2012 | 54.55 | 41.14 |

| 2013 | 26.42 | 26.62 |

| 2014 | 38.41 | 29.10 |

| 2015 | 36.08 | 36.93 |

| 2016 | 48.83 | 47.33 |

| 2017 | 181.52 | 119.18 |

| 2018 | 278.12 | 201.62 |

| 2019 | 395.69 | 273.53 |

|

||

Abbreviations: APC, annual percent change; eCHIRPP,

electronic Canadian Hospitals Injury Reporting and Prevention Program.

a Joinpoint graphs are shown to highlight the

inflection point in 2014 for females.

b Expressed as a proportion of eCHIRPP

records for a given year (× 100 000).

* Indicates that APC is significantly different from

zero at the α = 0.05 level.

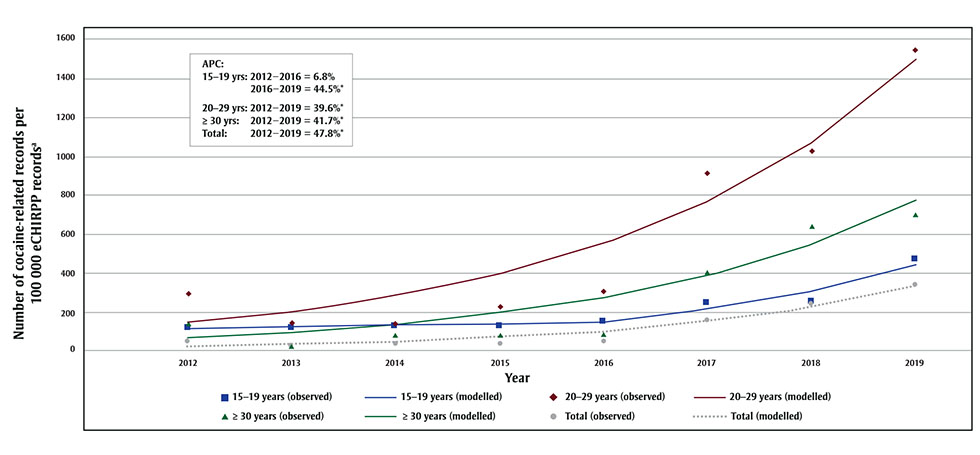

Figure 4 shows the trends in all cocaine-related injuries and poisonings by age group for 2012 to 2019. The overall trend of cocaine-related records for all age groups in eCHIRPP increased between the years 2012 and 2019 (APC = 47.8%, p < 0.05). Among those aged 15 to 19 years, the proportion of cocaine-related incidents increased slightly for 2012 through 2016 (APC = 6.8%, p > 0.05), then considerably increased from 2016 to 2019 (APC = 44.5%, p < 0.05). A steady growth was observed for those aged 20 to 29 and 30 years and older between 2012 and 2019 (APC = 39.6%, p < 0.05 and APC = 41.7%, p < 0.05, respectively).

Figure 4 - Text description

| Year | 15-19 yrs (observed) | 15-19 yrs (modelled) | 20-29 yrs (observed) | 20-29 yrs (modelled) | ≥ 30 yrs (observed) | ≥ 30 yrs (modelled) | Total (observed) | Total (modelled) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2012 | 121.29 | 113.39 | 293.69 | 144.62 | 139.82 | 67.36 | 48.83 | 21.5 |

| 2013 | 115.43 | 121.05 | 145.83 | 201.91 | 25.79 | 95.46 | 26.51 | 31.78 |

| 2014 | 126.64 | 129.23 | 138.01 | 281.89 | 78.69 | 135.28 | 34.37 | 46.98 |

| 2015 | 128.02 | 137.97 | 224.93 | 393.56 | 81.1 | 191.71 | 36.45 | 69.45 |

| 2016 | 151.01 | 147.29 | 301.43 | 549.48 | 87.89 | 271.68 | 48.17 | 102.66 |

| 2017 | 247.08 | 212.81 | 915.06 | 767.15 | 407.2 | 385.01 | 154.21 | 151.75 |

| 2018 | 253.19 | 307.48 | 1026.18 | 1071.06 | 644.74 | 545.62 | 244.14 | 224.32 |

| 2019 | 468.82 | 444.27 | 1546.58 | 1495.37 | 698.74 | 773.22 | 341.56 | 331.59 |

Abbreviations: APC, annual percent change; eCHIRPP,

electronic Canadian Hospitals Injury Reporting and Prevention Program.

a Expressed as a proportion of eCHIRPP

records for a given year (× 100 000).

*Indicates that APC is significantly different from zero

at the α = 0.05 level.

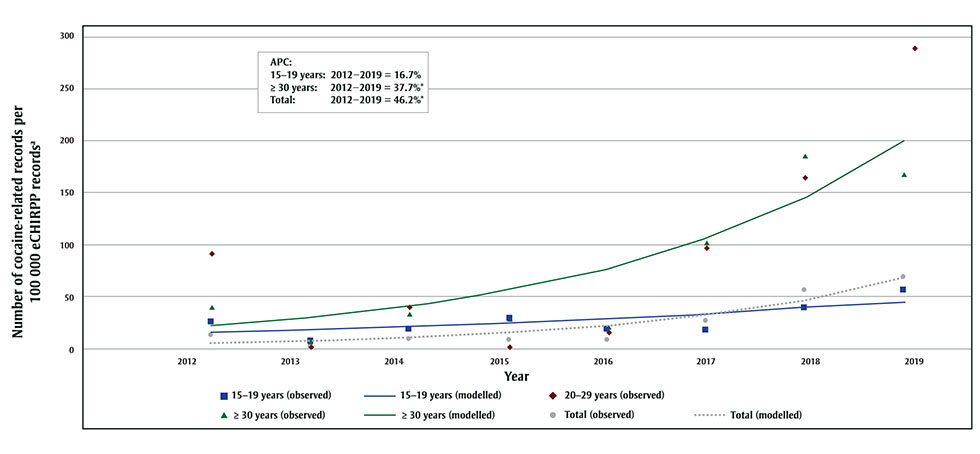

Figure 5 displays the trend of the cocaine-only injury and poisoning proportion by age group over the 2012 to 2019 period. The trend has no significant inflection point for the 15 to 19 years, 30 years and older, and all-age groups, and demonstrated an increasing trend (15–19: APC = 16.7%, p > 0.05; 30 years and older: APC = 37.7%, p < 0.05; all ages: APC = 46.2%, p < 0.05) during the study period. The APC for the 20 to 29 age group could not be estimated due to the insufficient number of cocaine injuries and poisonings in certain years.

Figure 5 - Text description

| Year | 15-19 yrs (observed) | 15-19 yrs (modelled) | 20-29 yrs (observed) | ≥ 30 yrs (observed) | ≥ 30 yrs (modelled) | Total (observed) | Total (modelled) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2012 | 24.24 | 15 | 91.59 | 39.91 | 21.31 | 11.44 | 4.73 |

| 2013 | 5.77 | 17.5 | 0 | 6.45 | 29.34 | 1.43 | 6.91 |

| 2014 | 17.25 | 20.42 | 39.39 | 32.77 | 40.4 | 8.42 | 10.1 |

| 2015 | 29.07 | 23.82 | 0 | 27.02 | 55.63 | 7.01 | 14.77 |

| 2016 | 17.4 | 27.79 | 15.03 | 20.67 | 76.59 | 7.36 | 21.59 |

| 2017 | 16.43 | 32.41 | 96.1 | 101.49 | 105.45 | 26.07 | 31.57 |

| 2018 | 38.14 | 37.81 | 164.58 | 184.45 | 145.2 | 55.33 | 46.15 |

| 2019 | 54.29 | 44.11 | 282.51 | 168.41 | 199.91 | 67.99 | 67.48 |

Abbreviations: APC, annual percent change; eCHIRPP,

electronic Canadian Hospitals Injury Reporting and Prevention Program.

Note: APC for the 20–29 age group could not be

estimated due to the insufficient number of cocaine-only injuries and poisonings

in certain years.

a Expressed as a proportion of eCHIRPP

records for a given year (× 100 000).

*Indicates that APC is significantly different from zero

at the α = 0.05 level.

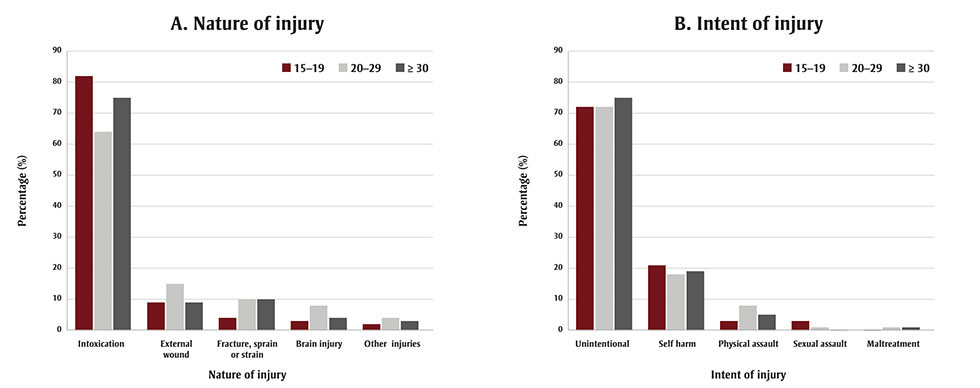

When investigating the nature of cocaine-related injuries and poisonings, we found that the nature of injury varied by the age group. Intoxication was found to be the leading nature of injury among all age groups (Figure 6A). External wound was the second highest among those aged 15 to 19 (9%) and 20 to 29 years (15%), and third among those aged 30 years and over (9%). Fracture, sprain or strain ranked third among those aged 15 to 19 (4%) and 20 to 29 (10%), and second among those aged 30 and over (10%; Figure 6A). Similarly, the intent of injuries among cocaine-related incidents also varied by age groups. Unintentional injury ranked first, followed by self-harm and physical assault for all age groups, except that in the 15 to 19 age group, sexual assault ranked third (Figure 6B).

Figure 6 - Text description

| Age group (years) | Intoxication | External wound | Fracture, sprain or strain | Brain injury | Other injuries |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15–19 | 82 | 9 | 4 | 3 | 2 |

| 20–29 | 64 | 15 | 10 | 8 | 4 |

| ≥30 | 75 | 9 | 10 | 4 | 3 |

| Age group (years) | Unintentional | Self harm | Physical assault | Sexual assault | Maltreatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15–19 | 72 | 21 | 3 | 3 | 0 |

| 20–29 | 72 | 18 | 8 | 1 | 1 |

| ≥30 | 75 | 19 | 5 | 0 | 1 |

Abbreviation: eCHIRPP, electronic Canadian Hospitals Injury Reporting and Prevention Program.

Discussion

Our study revealed a substantial number of cocaine-related injuries and poisonings and increasing trends in cocaine-related injury and poisoning patients presenting to EDs participating in eCHIRPP between January 2012 and December 2019. Adolescent years can be a time of experimentation with substance use for many young people.Footnote 20 Research has shown that early (12–14 years of age) to late (15–17 years of age) adolescence is a critical period for the initiation of substance use, with substance use typically being highest in early adulthood.Footnote 20 Consistent with the existing research,Footnote 20 we observed similar patterns of cocaine-related injuries in which younger adults (20–29 years) comprised a higher proportion of cocaine-related injuries and poisonings relative to older adults. This is of particular concern, given the evidence that substances with psychoactive effects have a greater impact on developing brains.Footnote 21 Adolescents may face difficulties as they pass through the different phases of development into young adulthood, and they may turn to substance use to cope with the demands of difficult situations.Footnote 22 Our findings illustrate the importance of continued surveillance of substance-related harms, especially among youth and young adults.

This study found that cocaine-related injuries and poisonings were generally higher among males compared to females, which is in accordance with the Canadian Tobacco, Alcohol and Drugs Survey (CTADS) findings that cocaine use was more prevalent among males than females in 2017.Footnote 6 However, our study found the proportion of cocaine-related injuries and poisonings among females under 19 years of age was slightly higher compared to males. Another key finding from our study is the most common injury location. When exploring the distribution of injuries occurring at indoor settings, we found that the highest proportion of cocaine-related injuries and poisonings occurred at the patient’s own home, followed by another person’s home. This is consistent with data from the 2001 Australia National Drug Strategy Household Survey, in which participants reported that they usually used cocaine at their own home or at a friend’s home.Footnote 23

Cocaine users frequently use cocaine with other substances, particularly alcohol or other psychoactive substances that modify the psychological effects of cocaine or blunt its unpleasant side effects.Footnote 24 However, cocaine taken in combination with other substances, presents more severe health risks than cocaine taken by itself, as it increases the toxicity of cocaine and risk of fatal overdose.Footnote 15 A study from Switzerland on acute cocaine-related health problems in patients presenting to an urban ED found that cocaine alone was used by a smaller proportion of patients (16%), whereas most patients (84%) consumed cocaine with at least one other substance such as alcohol, illicit drugs or cannabis.Footnote 25 Similarly, a technical report on the emergency health consequences of cocaine use in Europe revealed that alcohol is the substance most frequently co-ingested with cocaine, followed by psychoactive medicines.Footnote 26

In line with these studies, we observed that among all cocaine-related eCHIRPP records, 20% were related to cocaine-only use, while 80% were related to cocaine use combined with one or more other substances. Furthermore, the substances associated with the most injuries and poisonings identified in our study were cocaine in combination with mixed substances (i.e. cocaine plus more than one other substance), followed by cocaine combined with alcohol.

As cocaine is a psychoactive substance with known neurobehavioural effects such as irritability, anger and aggression, studies found that people who use cocaine might be more likely to be involved in injuries related to violence and assault.Footnote 27Footnote 28 Our study found approximately 25% of patients presenting to the ED with cocaine-related injuries or poisonings were there due to self-harm (18.5%), physical assault (5.3%) or sexual assault (1.2%). Though the majority of injuries in this study were due to intoxication and were unintentional, the acute use of alcohol and cocaine is known to be associated with suicide attempts and fatal injuries.Footnote 29Footnote 30 Our study demonstrates the importance of continued surveillance of substance-related harms including those involving cocaine use to help prevent the increasing incidence of substance-related emergencies.

Strengths and limitations

The major strength of this study is the utilization of the eCHIRPP database as the data source. The eCHIRPP is a well-established and reliable sentinel surveillance system that collects detailed clinical data from the EDs of 20 hospitals across Canada and captures a wide range of injuries and poisonings associated with the use of cocaine and other substances.

However, this study also has some limitations. It is possible that substance use may have been underreported due to stigma associated with the nature of the topic. Also, the majority of the participating eCHIRPP hospitals are pediatric hospitals; therefore, certain groups may be underrepresented in the data, such as older teens and adults.Footnote 17 In addition, as the eCHIRPP sentinel surveillance program operates only at selected Canadian hospital EDs, the true burden of cocaine-related injuries may have been underestimated. Another limitation is that the eCHIRPP data do not capture most of the fatal incidents or mild ones treated at other locations such as clinics, supervised injection sites or nonparticipating CHIRPP hospitals. Despite having data spanning an eight-year period (2012–2019), trend analysis (APC) for some strata were constrained by small sample sizes, which are subject to random variations. Future studies with larger sample sizes are needed to improve the precision of the trend estimates. Regardless of these limitations, the eCHIRPP database is a robust source of data related to injuries and poisonings associated with cocaine use among Canadians.

Conclusion

This study provides a descriptive overview of cocaine-related injury and poisoning characteristics, including intent and nature of injury. The higher frequency of cocaine-related injuries and poisonings in the adolescent and young adult age groups identified in this study suggests the need for ongoing surveillance efforts. In addition, the majority of injury and poisoning incidents captured in this study were related to the co-consumption of other substances with cocaine. Therefore, future research should aim to better understand the risk of injuries and poisonings associated with co-consumption of substances with cocaine. Finally, considering that 2020 and 2021 data were not included in our study, further study of any potential impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on substance use would be beneficial.

Conflicts of interest

The authors have no conflicts to declare.

Authors’ contributions and statement

II, MTD, SZ, SD, ZW, LG, SRM, AC and JC were involved in the project design and conceptualization. II conducted the literature review search and data analyses and drafted the manuscript. SRM, AC and JC extracted the eCHIRPP data. All authors contributed to revising the article.

The content and views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Government of Canada.