Evidence synthesis – Scoping review of adult-oriented outdoor play publications in Canada

HPCDP Journal Home

Published by: The Public Health Agency of Canada

Date published: March 2023

ISSN: 2368-738X

Submit a manuscript

About HPCDP

Browse

Previous | Table of Contents | Next

Louise de Lannoy, PhDAuthor reference footnote 1; Kheana Barbeau, BAAuthor reference footnote 2; Nick Seguin, MScAuthor reference footnote 3; Mark S. Tremblay, PhDAuthor reference footnote 1Author reference footnote 3Author reference footnote 4

https://doi.org/10.24095/hpcdp.43.3.04

This article has been peer reviewed.

Author references

Correspondence

Louise de Lannoy, CHEO Research Institute, 401 Smyth Rd, Ottawa, ON K1H 8L1; Tel: 343-202-8333; Email: ldelannoy@cheo.on.ca

Suggested citation

de Lannoy L, Barbeau K, Seguin N, Tremblay MS. Scoping review of adult-oriented outdoor play publications in Canada. Health Promot Chronic Dis Prev Can. 2023;43(3):139-50. https://doi.org/10.24095/hpcdp.43.3.04

Abstract

Introduction: Since 2015, there has been growing interest in Canada and beyond on the benefits of outdoor play for physical, emotional, social and environmental health, well-being and development, for adults as well as children and youth.

Methods: This scoping review aims to answer the question, “How, and in what context, is adult-oriented outdoor play being studied in Canada?” We conducted an electronic search for peer-reviewed articles on outdoor play published in English or French after September 2015 by authors from Canadian institutions or about Canadian adults. The 224 retrieved articles were organized according to eight priorities: health, well-being and development; outdoor play environments; safety and outdoor play; cross-sectoral connections; equity, diversity and inclusion; professional development; Indigenous Peoples and land-based outdoor play; and COVID-19. We tallied the study designs and measurement methods used.

Results: The most common priority was outdoor play environments; the least common were COVID-19 and Indigenous Peoples and land-based outdoor play. Cross-sectional studies were the most common; no rapid reviews were identified. Sample sizes varied from one auto-ethnographic reflection to 147 000 zoo visitor datapoints. More studies used subjective than objective measurement methods. Environmental health was the most common outcome and mental/emotional development was the least.

Conclusion: There has been a staggering amount of articles published on adult-oriented outdoor play in Canada since 2015. Knowledge gaps remain in the relationship between outdoor play and adult mental/emotional development; the connections between environmental health and Indigenous cultures and traditions; and how to balance promoting outdoor unstructured play with protecting and preserving natural spaces.

Keywords: preventive health, physical activity, healthy lifestyle, environmental health

Highlights

- We identified 224 Canadian articles on adult-oriented outdoor play.

- The most common priority was outdoor play environments; the least common were COVID-19 and Indigenous Peoples and land-based outdoor play.

- This scoping review highlights the staggering amount of articles published on adult-oriented outdoor play in Canada since 2015, identifies gaps in knowledge and provides recommendations for future work.

Introduction

The Position Statement on Active Outdoor Play (Position Statement)Footnote 1 highlighted the many benefits of outdoor play on children’s physical, mental, emotional, social and environmental health, development and well-being.Footnote 2Footnote 3 The Position Statement served to galvanize the outdoor play sector and bring together stakeholders with overlapping interests in outdoor play and children’s health and well-being from the education, community, health, environment, parks, wildlife, ecology, law and Indigenous rights sectors, among others.Footnote 1

The Position Statement also led to the formation of Outdoor Play Canada,Footnote 4 a network of thought leaders working together to promote, protect and preserve access to play in nature and the outdoors for people of all ages living in Canada. Seven years later, Outdoor Play Canada launched the Outdoor Play in Canada: 2021 State of the Sector Report (State of the Sector Report)Footnote 5 to reinvigorate the momentum set off by the Position Statement, to reflect on efforts achieved since its release, and to identify a common vision for the outdoor play sector.

This scoping review is part of that larger State of the Sector Report.Footnote 5 We sought to determine the volume of published outdoor play research by authors from Canadian institutions or about a Canadian population since the release of the Position StatementFootnote 1 and identify where existing evidence is concentrated and where further knowledge generation is required. We categorized all included outdoor play articles according to eight of the nine priorities identified in the State of the Sector ReportFootnote 5 (“the common vision”) to identify where there is substantial knowledge and evidence to inform practice and policy and where knowledge gaps remain. We did not include the “research and support data collection on outdoor play” priority because all published research papers align with this priority.

In this scoping review, we used the definition of outdoor play developed in the Play, Learn and Teach Outdoors Network (PLaTO-Net) Terminology, Taxonomy, Ontology Global Harmonization Project,Footnote 6 that outdoor play is “a form of play that takes place outdoors” and play is “voluntary engagement in activity that is fun and/or rewarding and usually driven by intrinsic motivation.” We also adhered to the Ryan and DeciFootnote 7,p.56 definition of intrinsic motivation as “doing an activity for its inherent satisfaction rather than for some separable consequence” (e.g. cracking thin ice puddles, making art for art’s sake).

As these broad definitions do not limit play to children, we did not limit the scope of this review to this age group. We identified 416 published articles in our initial search in March 2021 and 447 articles in a second search in March 2022. This was a staggering increase in the number of publications from the original 49 articles (not exclusively Canadian authors or populations) used to inform the Position Statement. Given the number of articles identified, we separated the included articles into two: literature on children’s and youth’s outdoor play and on adult-oriented outdoor play. This scoping review focusses on adult-oriented outdoor play and aims to determine how, and in what context, adult-oriented outdoor play is being studied in Canada.

Methods

The methods for this systematic scoping review have been described in detail in an article on child- and youth-oriented outdoor play.Footnote 8 Briefly, we followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis Extension for Scoping Review (PRISMA-ScR) guidelinesFootnote 9 (checklist available on request from the authors). We also used the Arksey and O’MalleyFootnote 10 framework and completed the following six steps: (1) identifying the research question; (2) identifying relevant studies; (3) selecting eligible studies; (4) charting the data; (5) collating, summarizing and reporting of results; and (6) consulting with relevant stakeholders.

Search strategy

We conducted an electronic search, led by KB, first in March 2021 and then again in March 2022, via Ovid MEDLINE, EBSCO Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) and Scopus. A description of the full search strategy and the search terms used have been published elsewhereFootnote 7 and are also available on the OSF platform.

Study inclusion criteria

We used the population, concept and context frameworkFootnote 11 to shape our research question and guide the development of the inclusion criteria. Included articles were

- written by authors from Canadian institutions or examined a Canadian population;

- in either of the two official languages in Canada (English and French); and

- published between the release of the Position Statement, in September 2015, and March 2022.

We based our definition of outdoor play on the definition developed in the PLaTO-Net Terminology, Taxonomy, Ontology Global Harmonization Project,Footnote 6 which does not limit play to children; as such we did not place any limits on participant age.

Study selection

Articles that met the inclusion criteria were downloaded and imported into Covidence (Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, AU). Following de-duplication, two reviewers (LDL and KB) worked independently to screen the titles and abstracts (level 1 screening) of included articles using the population, concept and context framework.Footnote 11 For full-text screening (level 2 screening), at least two of three reviewers (LDL, KB and NS) had to agree on final inclusion, resolving any conflicts through discussion to achieve consensus.

Data extraction

Three reviewers met weekly during the extraction phase to discuss any uncertainties and ensure standardization of the extraction protocol and to agree upon any amendments to the data extraction form (adapted from de Lannoy et al.Footnote 8), for example, if new outcomes had emerged.

The following data were extracted from each article using the Covidence extraction template: title, country, population (children/youth <18 years; adults ≥18 years; or both); study design; measurement of outdoor play; and outcomes associated with outdoor play. The outcomes associated with outdoor play included the following:

- cognitive development (“the process by which human beings acquire, organize and learn to use knowledge”);Footnote 12, p.317

- cognitive health (“the ability to clearly think, learn and remember”);Footnote 13

- environmental health (“the interconnections between people and their environment by which human health and a balanced, nonpolluted environment are sustained or degraded”);Footnote 14, p.995

- general well-being (“the combination of feeling good and functioning well”);Footnote 15

- mental development (“the progressive changes in mental processes due to maturation, learning and experience”) and emotional development (“gradualincrease in the capacity to experience, express, and interpret the full range of emotions and in the ability to cope with them appropriately”)Footnote 16

- mental/emotional health (“the state of psychological and emotional well-being”);Footnote 17

- physical development (advancements and growth of the body, including the brain, muscles and senses, and the refinements of motor skills);Footnote 18Footnote 19

- physical health (“the body’s physical state and how well it works,”Footnote 20,p.381 and “taking into consideration everything from the absence of disease to fitness level”);Footnote 21

- quality of life (“an individual’s perception of their position in life in the context of the culture in which they live and in relation to their goals, expectations, standards and concerns”Footnote 22, p.1403);

- skills development (an “ability and capacity acquired … to smoothly and adaptively carry out complex activities or … functions”Footnote 23,p.5); and

- social health (“that dimension of an individual’s well-being that concerns how [they] get along with other people, how other people react to [them] and how [they] interact with social institutions and societal mores”).Footnote 24, p.75

After data extraction, the template containing the extracted data was downloaded and expanded upon to synthesize themes related to study design and measurement of outdoor play.

We organized retrieved studies by design into the following categories: literature review, systematic review, meta-analysis, scoping review, rapid review, commentary, randomized controlled trial (RCT), non-RCT, longitudinal study, cross-sectional study or mixed methods study according to established definitions.Footnote 25

Measurement of outdoor play was categorized as objective or subjective. Objective measurements included use of a device (e.g. accelerometer, Global Positioning System); observations (e.g. system of observing outdoor play); or environmental assessment (e.g. examination of neighbourhood correlates of outdoor play). Subjective measurements included proxy report (e.g. parent reporting on their child’s behaviour), self-report (e.g. an individual reporting on their own behaviour) and narrative (e.g. single-person retelling of an experience). In addition, we extracted themes related to the priorities identified in the State of the Sector ReportFootnote 5 (see Table 1), as this scoping review was conducted as part of that report.

| PriorityFootnote b | Brief description | Number of action items and examples |

|---|---|---|

| Promote, protect, preserve and invest in outdoor play environments (Outdoor play environments) |

This priority is intended to be inclusive of all outdoor spaces where outdoor play may occur—built environments (e.g. playgrounds, streets) and existing natural spaces. It highlights synchronicities between outdoor play and sustainability efforts (e.g. development of sustainable cities and communities). | 15 action items E.g. Accept a shared responsibility for connection and access to the Land, where “Land” includes peoples, cultures, languages and knowledge. |

| Promote the health, well-being and developmental benefits of outdoor play (Health, well-being and development) |

This priority is intended to recognize the importance of outdoor play for physical, mental, emotional and social development of children and the health and well-being of people of all ages, while providing specific actions for how this information may be promoted across sectors. | 7 action items E.g. Promote an understanding of the value and benefit of play for all ages. |

| Expand and enable cross-sectoral connections/collaborations (Cross-sectoral connections) |

This priority recognizes that outdoor play initiatives, programs and projects are found across many sectors. To develop and promote outdoor play priorities, we need to promote connections and collaborations across sectors so that we work together, learn from each other and amplify each other’s work. | 6 action items E.g. Develop cross-sectoral connections and identify other stakeholders who will help fuel the development of measurement tools. |

| Increase and improve professional development opportunities in outdoor play (Professional development) |

This priority recognizes the need to increase and improve professional development opportunities in outdoor play for educators (e.g. early childhood educators, elementary and secondary school educators) as well as for those across all sectors involved in outdoor play (parents, coaches, health professionals, built environment professionals, students). This is crucial to help shift mindsets and provide tools to advocate for and promote outdoor play. | 15 action items E.g. Work with colleges and universities to make sure that training on outdoor play is available in early childhood education programs. |

| Reframe views on safety and outdoor play (Safety and outdoor play) |

This priority focusses on the need to reframe the ways liability and safety are applied to outdoor play opportunities to improve the balance between protecting against injury and promoting beneficial play opportunities. | 10 action items E.g. Take an assets-based approach; base decisions surrounding outdoor play on assets rather than on liabilities. |

| Advocate for equity, diversity and inclusion in outdoor play (Equity, diversity and inclusion) |

This priority is grounded in and builds upon the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, which recognizes “the right of the child to rest and leisure, to engage in play and recreational activities appropriate to the age of the child and to participate freely in cultural life and the arts.”Footnote 26 | 9 action items E.g. Ensure that diverse groups, including Indigenous Peoples, and children and youth, are at outdoor play leadership tables. |

| Ensure that outdoor play initiatives are Land-based and represent the diverse cultures, languages and perspectives of Indigenous Peoples of North America (Indigenous Peoples and land-based outdoor play) |

This priority recognizes that Indigenous Peoples have lived on and played in connection with the Land we now call Canada since time immemorial, and that supporting, learning about and engaging in Indigenous-led land-based outdoor play provides an opportunity to build trusting and respectful relationships between Indigenous Peoples and non-Indigenous people, move towards reconciliation and raise the next generation of environmental stewards. | 7 action items E.g. Focus on creating ethical and safe spaces to support Indigenous and western worldviews coming together respectfully and in a balanced way. Find ways to support these respectful partnerships. |

| Leverage engagement opportunities with the outdoors during and after COVID-19 (COVID-19) |

This priority highlights how the COVID-19 pandemic led to a rediscovery of the outdoors for physical and mental health, for enjoyment, fun and relaxation. This rediscovery has great potential to be an accelerator for outdoor play efforts. | 6 action items E.g. Leverage the current opportunity (the pandemic) to push the importance of outdoor play and recognize the advantages it brings. Preserve neighbourhood changes that have encouraged and facilitated spontaneous outdoor play. |

| Research and support data collection on outdoor play (Research and data collection) |

This priority focuses on gaps in knowledge related to outdoor play, and the research and data collection efforts that are needed to address those gaps. It also recognizes that research and knowledge on outdoor play needs to be made accessible to governments, policy makers, educators, community organizations and the private sector. | 10 action items E.g. Create valid and reliable outdoor play measurement tools and resources and promote the use of these tools to achieve greater consistency and reproducibility across research groups. |

Data synthesis

Because of the large number of articles meeting the inclusion criteria following level 2 screening (n = 447), the data were separated into two datasets according to age (children/youth <18 years; adults ≥18 years). If an article included both children/youth and adults, it was included in both datasets.

We organized the articles according to the priorities identified in the State of the Sector Report (see Table 1), recognizing that many articles align with more than one priority. We then counted the articles categorized according to each priority, each type of study design and measurements of outdoor play.

Stakeholder engagement

The various components of the State of the Sector Report, including the scoping reviews used to identify the outdoor play research published since the release of the Position Statement, were discussed during a series of four meetings by a 63-person national cross-sectoral consultation group. In addition, at the launch of the State of the Sector Report at the 2021 Breath of Fresh Air Summit, stakeholders discussed how this scoping review could identify a base of knowledge on equity, diversity and inclusion efforts in the field of outdoor play.

More information on the process of developing the State of the Sector Report is available on the Outdoor Play Canada website.

Results

Study selection

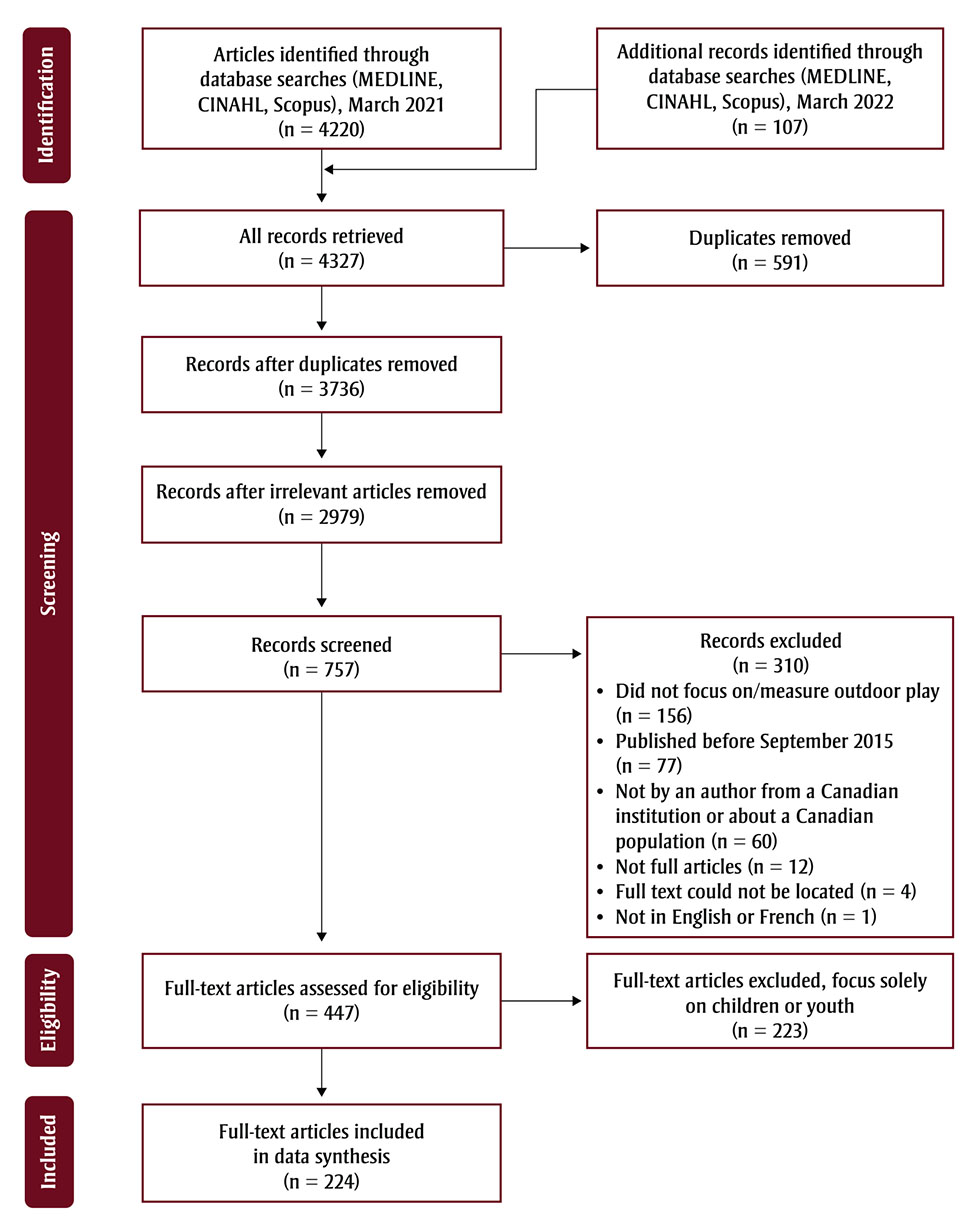

Our search of Canadian-focussed peer-reviewed outdoor play publications retrieved 4327 results. A total of 591 duplicates were removed, resulting in 3736 articles sent to level 1 screening. After removal of irrelevant articles (n = 2979), 757 articles underwent level 2 screening. At this point, 310 articles were excluded because they did not measure or focus on outdoor play (n = 156; 50%); they were published before September 2015 (n = 77; 25%); they did not study a Canadian population or were not written by an author from a Canadian institution (n = 60; 19%); they were not considered to be journal articles (e.g. they were conference proceedings, etc.; n = 12; 4%); the full-text could not be located (n = 4; 1%); or they were not published in either English or French (n = 1; <1%). For the full review, 447 articles were deemed relevant; 223 articles that focussed solely on children/youth underwent a separate scoping review,Footnote 8 and 224 articles that focussed on adult-oriented outdoor play were included in this scoping review.

See Figure 1 for a visual representation of the screening process.

Figure 1 - Text description

This figure illustrates the selection process of studies for inclusion in the scoping review. There are 3 phases to the process: identification, screening, eligibility.

Phase 1: Identification

- Articles identied through database searches (MEDLINE, CINAHL, Scopus), March 2021 (n = 4220)

- Additional records identied through database searches (MEDLINE, CINAHL, Scopus), March 2022 (n = 107)

This yielded a total of 4327 articles identified, which were analyzed in phase 2.

Phase 2: Screening

- Records after duplicates removed: (n = 3736)

- Records after irrelevant articles removed: (n = 2979)

- Records screened: (n = 757)

- Of the 757 records screened, there were records excluded (n = 310) for the following reasons:

- Did not focus on/measure outdoor play: (n = 156)

- Published before September 2015: (n = 77)

- Not by a Canadian author or about a Canadian population: (n = 60)

- Not full articles: (n = 12)

- Full text could not be located: (n = 4)

- Not in English or French: (n = 1)

- Of the 757 records screened, there were records excluded (n = 310) for the following reasons:

This yielded a total of 447 articles screened, which were analyzed in phase 3.

Phase 3: Eligibility

- Full-text articles assessed for eligibility (n = 447)

- Of the 447 articles assessed for eligibility, there were some excluded (n = 223) because they focused solely on children or youth.

Therefore, n = 224 full-text articles were included in the data synthesis.

Study characteristics

An overview of the characteristics of each included study is shown in Supplementary Table 1. By definition, all studies focussed on adults 18 years and older (some also included children/families) and were written by authors from Canadian institutions or were works that studied a Canadian population. Sixteen studies included data from both Canadian and international populations,Footnote 28Footnote 29Footnote 30Footnote 31Footnote 32Footnote 33Footnote 34Footnote 35Footnote 36Footnote 37Footnote 38Footnote 39Footnote 40Footnote 41Footnote 42Footnote 43 and in one, a Canadian research team analyzed data exclusively from international populations.Footnote 42 Sample sizes varied substantially and ranged from an auto-ethnographic reflection by one individual involved in a community gardening projectFootnote 45 to 147 000 data points on zoo visitors over 16 years.Footnote 46

Outdoor play themes

A central aim of this scoping review was to identify how many of the included articles align with each of the priorities identified in the State of the Sector Report, recognizing that many would align with more than one. We sorted included articles according to one or more of the following priorities, in order, from highest to lowest number of included studies: outdoor play environments (n = 165); health, well-being and development (n = 163); cross-sectoral connections (n= 66); professional development (n = 40); safety and outdoor play (n = 37); equity, diversity and inclusion (n = 36); Indigenous Peoples and land-based outdoor play (n = 16); and COVID-19 (n = 10). As previously mentioned, by the nature of their being published, all studies could be included in the “research and support data collection on outdoor play” priority; as a result, we did not use this priority when categorizing the articles.

Outdoor play study design

Cross-sectional studies were the most common study design across the State of the Sector Report (see Table 2). No rapid reviews were identified. There were no commentaries in the Indigenous Peoples and land-based outdoor play and COVID-19 priorities; no meta-analyses in the cross-sectoral connections, equity, diversity and inclusion, professional development, safety and outdoor play, Indigenous Peoples and land-based outdoor play or COVID-19 priorities; no mixed-methods studies in the COVID-19 priority; no non-RCT interventions in the equity, diversity and inclusion, Indigenous Peoples and land-based outdoor play, and COVID-19 priorities; no RCTs in the outdoor play environments, equity, diversity and inclusion, Indigenous Peoples and land-based outdoor play and COVID-19 priorities; no scoping reviews in the safety and outdoor play, professional development and COVID-19 priorities; and no systematic reviews in the professional development and COVID-19 priorities.

| Study design | Articles per priority, % (n)Footnote b | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outdoor play environments (n = 165) |

Health, well-being and development (n = 163) |

Cross-sectoral connections (n = 66) |

Professional development (n = 40) |

Safety and outdoor play (n = 37) |

Equity, diversity and inclusion (n = 36) |

Indigenous Peoples and land-based outdoor play (n = 16) |

COVID-19 (n = 10) |

|

| Commentary | 4.8 (8) | 6.1 (10) | 3.0 (2) | 5.0 (2) | 2.7 (1) | 2.8 (1) | 0 | 0 |

| Cross-sectional study | 58.2 (96) | 55.8 (91) | 53.0 (35) | 60.0 (24) | 56.8 (21) | 58.3 (21) | 43.8 (7) | 80.0 (8) |

| Literature review | 15.2 (25) | 11.0 (18) | 15.2 (10) | 15.0 (6) | 21.6 (8) | 19.4 (7) | 31.3 (5) | 10.0 (1) |

| Longitudinal study | 6.7 (11) | 6.7 (11) | 12.1 (8) | 5.0 (2) | 2.7 (1) | 5.6 (2) | 6.3 (1) | 10.0 (1) |

| Meta-analysis | 0.6 (1) | 0.6 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Mixed methods | 10.3 (17) | 13.5 (22) | 18.2 (12) | 15.0 (6) | 10.8 (4) | 16.7 (6) | 12.5 (2) | 0 |

| Non-RCT intervention | 4.8 (8) | 5.5 (9) | 3.0 (2) | 5.0 (2) | 5.4 (2) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| RCT | 0 | 0.6 (1) | 1.5 (1) | 2.5 (1) | 2.7 (1) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Rapid review | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Scoping review | 2.4 (4) | 3.1 (5) | 1.5 (1) | 0 | 0 | 2.8 (1) | 6.3 (1) | 0 |

| Systematic review | 4.8 (8) | 4.3 (7) | 3.0 (2) | 0 | 2.7 (1) | 8.3 (3) | 12.5 (2) | 0 |

Measurement of outdoor play

Articles were also grouped and tallied according to measurement of outdoor play and further subdivided into objective and subjective measures (see Table 3). Across all State of the Sector Report priorities, subjective measures were more common than objective measures.

| Measures | Articles per priority, % (n)Footnote b | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outdoor play environments (n = 165) |

Health, well-being and development (n = 163) |

Cross-sectoral connections (n = 66) |

Professional development (n = 40) |

Safety and outdoor play (n = 37) |

Equity, diversity and inclusion (n = 36) |

Indigenous Peoples and land-based outdoor play (n = 16) |

COVID-19 (n = 10) |

|

| Subjective measures | ||||||||

| Narrative | 41.2 (68) | 50.9 (83) | 63.6 (42) | 55.0 (22) | 45.9 (17) | 52.8 (19) | 56.3 (9) | 0 |

| Proxy report | 5.5 (9) | 6.7 (11) | 4.5 (3) | 2.5 (1) | 10.8 (4) | 2.8 (1) | 0 | 20.0 (2) |

| Self-report | 44.2 (73) | 47.2 (77) | 47.0 (31) | 47.5 (19) | 32.4 (12) | 41.7 (15) | 31.3 (5) | 60.0 (6) |

| Objective measures | ||||||||

| Device | 8.5 (14) | 7.4 (12) | 4.5 (3) | 7.5 (3) | 10.8 (4) | 0 | 6.3 (1) | 10.0 (1) |

| Environmental assessment | 7.9 (13) | 3.7 (6) | 3.0 (2) | 0 | 0 | 5.6 (2) | 0 | 0 |

| Observations | 11.5 (19) | 10.4 (17) | 9.1 (6) | 7.5 (3) | 8.1 (3) | 11.1 (4) | 12.5 (2) | 10.0 (1) |

The most common method of subjective measurement was narrative, except in studies within the outdoor play environments and COVID-19 priorities, which used self-reports more often. Proxy reporting was the least common subjective method of measurement, except for the COVID-19 priority, where narrative was the least common subjective method of measurement.

Observation was the most common objective method of measurement across priorities, tying with devices as the most common measure within the professional development and COVID-19 priorities. Devices alone were the most common objective method of measurement for the safety and outdoor play priority.

Environmental assessment was the least used objective method of measurement, except for studies within the equity, diversity and inclusion priority, where none of the studies used devices as their objective method of measurement.

Commentary themes

Commentaries were grouped into three main themes: outdoor play and climate change/ecological impacts; outdoor play as a method or facilitator of learning; and outdoor play and physical and/or mental well-being (see Table 4). Across State of the Sector Report priorities, outdoor play and physical and/or mental well-being was the most common commentary theme. Outdoor play as a method or facilitator of learning was the least common theme and, alongside the theme on outdoor play and climate change/ecological impacts, was not found in the cross-sectoral connections, professional development, safety and outdoor play, equity, diversity and inclusion, Indigenous Peoples and land-based outdoor play or COVID-19 priorities.

| Commentary themes | Articles per priority, % (n)Footnote b | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outdoor play environments (n = 165) |

Health, well-being and development (n = 163) |

Cross-sectoral connections (n = 66) |

Professional development (n = 40) |

Safety and outdoor play (n = 37) |

Equity, diversity and inclusion (n = 36) |

Indigenous Peoples and land-based outdoor play (n = 16) |

COVID-19 (n = 10) |

|

| Outdoor play and climate change/ecological impacts | 1.8 (3) | 1.9 (3) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Outdoor play as a method/facilitator of learning | 1.2 (2) | 1.2 (2) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Outdoor play and physical and/or mental well-being | 3.0 (5) | 4.3 (7) | 3.0 (2) | 5.0 (2) | 2.7 (1) | 2.8 (1) | 0 | 0 |

Outcomes

Within each of the State of the Sector Report priorities, articles were categorized and tallied according to outcome (see Table 5). Environmental health was the most common outcome for half of the priorities, namely outdoor play environments, cross-sectoral connections, professional development (tied as most common with skills development) and Indigenous Peoples and land-based outdoor play.

In contrast, mental/emotional development was not identified as an outcome in any of the priorities. Cognitive health as an outcome was not found within the safety and outdoor play or COVID-19 priorities. Cognitive development, physical development, quality of life and skills development were other outcomes not found within the COVID-19 priority.

| Outcome | Articles per priority, % (n)Footnote b | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outdoor play environments (n = 165) |

Health, well-being and development (n = 163) |

Cross-sectoral connections (n = 66) |

Professional development (n = 40) |

Safety and outdoor play (n = 37) |

Equity, diversity and inclusion (n = 36) |

Indigenous Peoples and land-based outdoor play (n = 16) |

COVID-19 (n = 10) |

|

| Cognitive development | 5.5 (9) | 8.0 (13) | 15.2 (10) | 20.0 (8) | 5.4 (2) | 5.6 (2) | 12.5 (2) | 0 |

| Cognitive health | 6.7 (11) | 8.0 (13) | 6.1 (4) | 7.5 (3) | 0 | 8.3 (3) | 12.5 (2) | 0 |

| Environmental health | 65.5 (108) | 42.9 (70) | 48.5 (32) | 42.5 (17) | 35.1 (13) | 41.7 (15) | 62.5 (10) | 20.0 (2) |

| General well-being | 21.8 (36) | 29.4 (48) | 21.2 (14) | 15.0 (6) | 27.0 (10) | 38.9 (14) | 31.3 (5) | 40.0 (4) |

| Mental/emotional development | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Mental/emotional health | 23.6 (39) | 34.4 (56) | 24.2 (16) | 12.5 (5) | 24.3 (9) | 30.6 (11) | 43.8 (7) | 30.0 (3) |

| Physical development | 4.2 (7) | 4.9 (8) | 4.5 (3) | 10.0 (4) | 2.7 (1) | 5.6 (2) | 0 | 0 |

| Physical health | 27.9 (46) | 38.7 (63) | 24.2 (16) | 12.5 (5) | 48.6 (18) | 30.6 (11) | 12.5 (2) | 80.0 (8) |

| Quality of life | 4.2 (7) | 5.5 (9) | 4.5 (3) | 2.5 (1) | 2.7 (1) | 11.1 (4) | 12.5 (2) | 0 |

| Skills development | 13.9 (23) | 15.3 (25) | 30.3 (20) | 42.5 (17) | 24.3 (9) | 22.2 (8) | 25.0 (4) | 0 |

| Social health | 34.5 (57) | 44.2 (72) | 40.9 (27) | 27.5 (11) | 35.1 (13) | 58.3 (21) | 50.0 (8) | 30.0 (3) |

Discussion

As for our scoping review on children’s and youth’s outdoor play,Footnote 8 the number of articles published on adult-oriented outdoor play in Canada over the past 7 years and included in this review is remarkable compared to other reviews on Canadian leisure research from past years.Footnote 47 The COVID-19 pandemic led to a pattern of reengaging with the outdoors for safe social gatherings, the health benefit and, more simply, as “something to do” in the face of pandemic-related restrictions.Footnote 48 This reengagement may have contributed to the surge in outdoor play publications in 2020, as did the increase in the number of researchers who, in accordance with health-related guidelines put in place to decrease transmission of SARS‑CoV‑2, were unable to spend time in the lab or field and instead focussed on writing.Footnote 49

Despite this surge, we observed areas where further research is required, namely on Indigenous and land-based outdoor play as well as outcomes related to adult-oriented mental/emotional development.

Outdoor play priorities

We included all ages in the scoping review to adhere to the PLaTO-Net definition of outdoor play.Footnote 6 We subsequently decided to separate the data according to age (children/youth and adults) because of the large number of articles retrieved based on our inclusion criteria and because we surmised that adult-oriented outdoor play would explore different themes and outcomes and may be measured and expressed differently from children’s and youth’s outdoor play. Accordingly, the outdoor play environments priority was the more common focus of studies on adult-oriented outdoor play, whereas health, well-being and development was the primary focus in the scoping review on children’s and youth’s outdoor play.Footnote 8 Similarly, environmental health (e.g. pro-environmental leisure activity, behaviour and/or stewardship), was the most common outcome studies of adult-oriented outdoor play examined, while in children and youth this was physical health (see Supplementary Table 2).

Of concern is that the Indigenous Peoples and land-based outdoor play priority continues to be among the least common (n = 16), second only to COVID-19 (n = 10), despite recognized connections between the environment, environmental health and Indigenous cultures and traditionsFootnote 44Footnote 50Footnote 51Footnote 52 For example, in the article by Mikraszewicz and Richmond in 2019,Footnote 50 the authors present the reflections of Elders and youth canoeing the length of the Pic River on the ways the journey fostered and was pivotal to promoting cultural identity, traditional knowledge sharing and land stewardship. The State of the Sector ReportFootnote 5 identifies seven action items (see Table 1) to support the Indigenous Peoples and land-based outdoor play priority, help build trusting relationships between local Indigenous and non-Indigenous people, address the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s Calls to Action,Footnote 53 and raise the next generation of environmental stewards. Addressing these actions is one approach the outdoor play sector can take to promote the recognition of Indigenous knowledge as integral to advancing outdoor play environments.

Outdoor play outcomes

As with the scoping review of children’s and youth’s outdoor play,Footnote 8 the least commonly measured outcome for adult-oriented outdoor play was mental/emotional development; in fact, our search through three health-centred databases of peer-reviewed articles did not retrieve any articles that explored this outcome. However, we identified many articles that explored mental/emotional health (n = 59).

A similar pattern was observed for articles examining the effect of adult outdoor play on physical development and physical health, with very few articles identified for physical development (n = 8) and many more for physical health (n = 73). What is curious is that the number of articles on cognitive development and cognitive health was the same (n = 15, each). This suggests that while recognition and interest are growing in the area of cognitive development and outdoor play in adult populations, the same is not true for mental/emotional and physical development, highlighting a major gap and opportunity for future research.

A common thread through articles that explored cognitive development was a focus on outdoor educational programs with opportunities for learning for both students and practitioners. These studies often explored how child-led outdoor learning challenges traditional pedagogical approaches.Footnote 54Footnote 55Footnote 56Footnote 57Footnote 58Footnote 59Footnote 60 In a similar vein, in Leather et al.,Footnote 61 co-authors from Canada and the United Kingdom challenged conventional postsecondary pedagogy and showed how play may serve to promote creativity, wellness and graduate employability among adult learners.

Although the benefits of outdoor play for adult learners and practitioners have historically received little attention, this is beginning to change. In Scotland, for example, outdoor play programs are reported to expand practitioner teaching and learning opportunities and support their sense of resilience and well-being.Footnote 62 Outdoor play as a pedagogical approach is discussed in the professional development priority and represents the need to increase and improve opportunities for high-quality professional development in outdoor play. It is therefore encouraging that there is a growing body of evidence that may be used to support the action items within this priority and the notion of outdoor play as an avenue for lifelong learning.

Measurement of outdoor play

The results of this scoping review show that adult outdoor play typically focusses on outdoor recreation and leisure, although some articles discuss adult outdoor play in the context of co-play with children.Footnote 63Footnote 64Footnote 65Footnote 66 Accordingly, outdoor play was often measured through narrative interviews with recreation and leisure participants. For example, Neumann and MasonFootnote 67 allowed interviewed facility managers to stray from the pre-prepared interview questions in order to more effectively describe the unique or specific ways in which they were able to sustainably resolve conflicts between cross-country skiers and fat bikers sharing recreational trails. In other papers in this scoping review, this form of interviewing, which allows participants the space to describe their experiences across time in relation to the topic of study, is often described as “storytelling.”Footnote 68Footnote 69

Although subjective measures, such as these narrative interviews, were the most common method of measurement (see Table 3), as was observed for children’s and youth’s outdoor play,Footnote 8 fewer studies examining adult-oriented play used a combination of subjective and objective methods of measurement. Using a combination of measures to assess children’s and youth’s outdoor play may be necessary as their play is less structured and more spontaneous than adults’ outdoor play and therefore more difficult to assess. But it is also plausible that the field of adult play is underdeveloped and less rigorously studied because play is typically considered an activity that is important for children and youth at various developmental stages.

When several methods were used to measure adults’ outdoor play, objective measures were often used to assess physical activity and subjective measures to capture the experience and emotion associated with the activity. For example, in a study of the impact on visitor usage of converting an urban trail into a skate way during the winter, McGavock et al.Footnote 70 measured trail use and users’ physical activity using objective measures and the impact on mental health with subjective measures. Both physical and emotional/mental elements are critical components of play for adults as well as children, as per the PLaTO-Net definition.Footnote 6 This reinforces the State of the Sector ReportFootnote 5 action item on the need to create valid and reliable outdoor play measurement tools to gather complete and consistent data across studies.

Strengths and limitations

Major strengths of this scoping review on adult-oriented outdoor play include its adherence to best practices for conducting scoping reviews, with the use of the PRISMA-ScR guidelinesFootnote 9 and the Arksey and O’MalleyFootnote 10 framework. Further, as our search included all peer-reviewed literature, regardless of type of study or article, we were able to identify and document the vastness and diversity of the literature published in Canada on the topic.

Our exclusion of articles in languages other than English or French, a potential limitation, resulted in the removal of only one study. Our focus on published studies by authors from Canadian institutions or that examined a Canadian population only limits the generalizability of our findings beyond Canada. Indeed, it also provides insight for Canadian outdoor play advocates, practitioners, researchers and organizations on the knowledge available to support the actions within the State of the Sector Report,Footnote 5 and where further knowledge generation is needed to take relevant action.

Future directions

Adult-oriented outdoor play environments, with the focus on the environmental impacts of outdoor recreation and leisure (see Table 1), is a topic that is gaining interest partly because of the growth in outdoor pursuits during the COVID-19 pandemic,Footnote 30 recognition of Indigenous knowledge as integral to advancing this topic,Footnote 50Footnote 51Footnote 52 as well as the burgeoning concerns of governments and researchers alike over the effects of climate change and the need to protect natural spaces.Footnote 71 This was much less of a focus in the articles included in the scoping review on children’s and youth’s outdoor play,Footnote 8 despite children’s tendencies to wander beyond designated paths and trails while playing outdoors.Footnote 55 Identifying how to balance promoting unstructured outdoor play—and the curiosity and environmental stewardship that comes from it for both children and adults—with protecting and preserving natural spaces is a clear gap in the literature and warrants further investigation.

While Canadians nationwide were seen to re-engage with the outdoors during the COVID-19 pandemic, the pandemic also revealed that access to the outdoors and outdoor spaces is not equitably distributed.Footnote 72 At the launch of the State of the Sector Report at the 2021 Breath of Fresh Air Summit in October 2021, several stakeholders emphasized the importance of establishing, as a first step, a base of knowledge on equity, diversity and inclusion efforts in the field of outdoor play. Our search retrieved 36 articles on this priority, including a recent scoping review on the relationship between nature and immigrants’ integration and well-being in Canada.Footnote 73 This and the other articles identified may help showcase current obstacles and achieved successes and inform future efforts in advancing equity, diversity and inclusion in the outdoor play sector.

Conclusion

We retrieved 224 articles published since 2015 and written by authors from Canadian institutions or about Canadian adults in response to the question, “How, and in what context, is adult-oriented outdoor play being studied in Canada?” The articles covered all State of the Sector ReportFootnote 5 priority areas. The most common focus was outdoor play environments, and the most common outcome environmental health. The least common priorities were COVID-19, likely because of the relative recency of the start of the pandemic, and Indigenous Peoples and land-based outdoor play. This is a concern given the recognized connections between the environment, environmental health and Indigenous cultures and traditions. Moreover, we did not identify any articles that looked at mental/emotional development as an outcome, highlighting a major knowledge gap.

This scoping review calls attention to the encouraging and staggering increase in adult-oriented outdoor play research in Canada over the last 7 years; identifies gaps in knowledge; and proposes areas for future work to ensure the promotion, protection and preservation of access to play in nature and the outdoors for all people living in Canada.

Acknowledgements

Funding for the Outdoor Play in Canada: 2021 State of the Sector Report, including this scoping review, was secured through a grant from an anonymous donor, The Lawson Foundation and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council.

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Authors’ contributions and statement

Conceptualization of the scoping review – LDL, KB and MST

Data curation, formal analysis and investigation – LDL, KB and NS

Methodology – LDL and KB

Writing of the original draft – LDL

Review and editing of the draft – LDL, KB, NS and MST

Funding acquisition – LDL and MST

Project administration – LDL and MST

The content and views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Government of Canada.