Chapter 2: Mapping Connections: An understanding of neurological conditions in Canada – Health services for neurological conditions

2. Health Services for Neurological Conditions

Neurological conditions are associated with a broad spectrum of health impacts that vary both in nature and in severity (Chapter 1). A range of health services for individuals living with a neurological condition, their families, and caregivers is necessary to appropriately address these impacts. In Canada, health is a shared responsibility between federal and provincial governments, with provinces and territories in charge of the organization of their health services. Thus, a true understanding of the issues related to health services in Canada would require data collection at the provincial and territorial levels in order to develop knowledge relevant to each jurisdiction.

Several projects of the Study explored the need for, and adequacy of, health services for those with a neurological condition along the continuum of health care provision [1][2][4][6][7][8][9][10][11][16]. These projects included the perspectives of individuals living with a neurological condition, informal caregivers, health care providers, and policy makers. In this chapter, health services were investigated in terms of utilization, costs, role of informal caregivers, perceptions (of administrators, patients, and caregivers) on their adequacy, delivery of continuing care, care of children, and specific needs of Aboriginal Canadians.

It takes strong and sustained advocacy to access and coordinate the range of services required. Services for our daughter come from: the health authority, money set aside for physiotherapy, a disability group, a community living fund, foundations, etc.

~ Informal caregiver

2.1 Individuals with a neurological condition use a considerable amount of health care services across the continuum of care

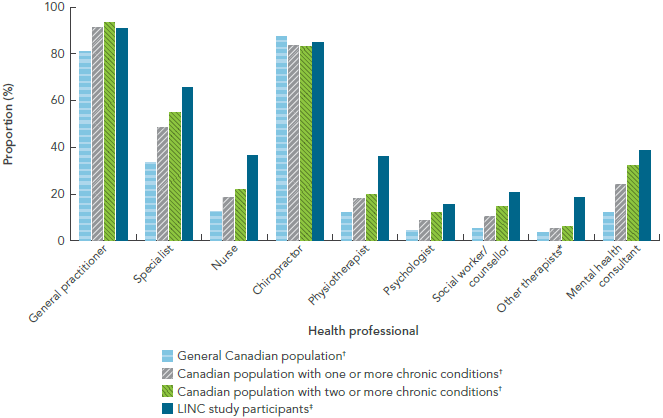

The LINC Project [9] survey, based on a convenience sample of 754 volunteer adults living with a neurological condition in the community, found that these individuals used more universally insured health services than Canadians with other chronic health conditions (Figure 2-1).Footnote 25 This finding was related to specialist physician services in particular, but was also applicable to service providers that were not always accessible through public funding, such as nurses, physiotherapists, psychologists, social workers, and counsellors.

FIGURE 2-1: Health service utilization in the past year among Canadians with and without neurological or other chronic health conditions, by health professional type, Canada, 2010-2012, The Everyday Experience of Living with and Managing a Neurological Condition (LINC) Project [9]

NOTES:

- LINC

- The Everyday Experience of Living with and Managing a Neurological Condition.

- CCHS

- Canadian Community Health Survey.

- *

- Other therapists included occupational therapists, audiologists, and speech therapists.

- †

- 2009-2010 CCHS data; data were weighted to represent the Canadian population living in the community and were age-sex-standardized to the LINC population. Chronic conditions included asthma, arthritis, back problems, high blood pressure, chronic bronchitis/emphysema, diabetes, heart disease, cancer, ulcers, urinary incontinence, bowel disorders, mood disorders, or anxiety disorders.

- ‡

- LINC data.

SOURCES: LINC survey (LINC Project [11]); 2009-2010 CCHS (Statistics Canada).

Text Equivalent - Figure 2-1

The bar graph shows the utilization of health services in the past year by health professional type. Canadians with a neurological condition in the LINC study were compared to the general Canadian population, Canadians living with one or more chronic condition(s), and Canadians living with two or more chronic conditions. This is shown on the horizontal axis, and is shown for each health professional type (general practitioner, specialist, nurse, chiropractor, physiotherapist, psychologist, social worker or counsellor, other therapist, or mental health consultant). On the graph, the vertical axis lists the proportions of health service utilization, by each of these four populations, for each health professional type.

In general, the use of a general practitioner and chiropractor was high for any of the populations (with or without a neurological or chronic condition). For general practitioners, the Canadian population with two or more chronic conditions (which included asthma, arthritis, back problems, high blood pressure, chronic bronchitis/emphysema, diabetes, heart disease, cancer, ulcers, urinary incontinence, bowel disorders, mood disorders, or anxiety disorders) had the highest utilization. For chiropractors, the general Canadian population had the highest utilization. For the other health professional types, Canadians with a neurological condition in the LINC study had the highest utilization.

Data were from the 2010-2012 LINC survey from the LINC Project and the 2009-2010 CCHS from Statistics Canada. LINC stands for The Everyday Experience of Living with and Managing a Neurological Condition. CCHS stands for Canadian Community Health Survey. CCHS data were weighted to represent the Canadian population living in the community and were age-sex-standardized to the LINC population.

The table lists the proportions of health service utilization by each population for each health professional type under study:

| General practitioner (%) | Specialist (%) | Nurse (%) | Chiropractor (%) | Physiotherapist (%) | Psychologist (%) | Social worker/counsellor (%) | Other therapists (%) | Mental health consultant (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LINC study participants | 90.8 | 65.5 | 36.3 | 84.6 | 36.1 | 15.4 | 20.7 | 18.4 | 38.5 |

| General Canadian population | 80.7 | 33.4 | 12.4 | 87.4 | 11.8 | 4.3 | 4.9 | 3.3 | 11.9 |

| Canadian population with one or more chronic conditions | 91.2 | 48.2 | 18.4 | 83.6 | 17.8 | 8.6 | 10.1 | 5.1 | 24.0 |

| Canadian population with two or more chronic conditions | 93.3 | 54.9 | 21.8 | 83.0 | 19.7 | 12.1 | 14.4 | 5.8 | 32.0 |

Up to a quarter of the population living with a neurological condition in the community accesses formal assistance. Twenty-five per cent of respondents to the LINC survey made extensive use of formal caregiving, mainly for personal care (eating, dressing, bathing, and toileting) or for house and yard work [9]. Similarly, when respondents with migraine were removed from SLNCC data,Footnote 26 21.2% of Canadians living with a neurological condition reported accessing formal assistance during the previous year [16]. In Ontario, individuals with a neurological condition in registered home care programs used more health care services than did those receiving home care for other conditions [8].

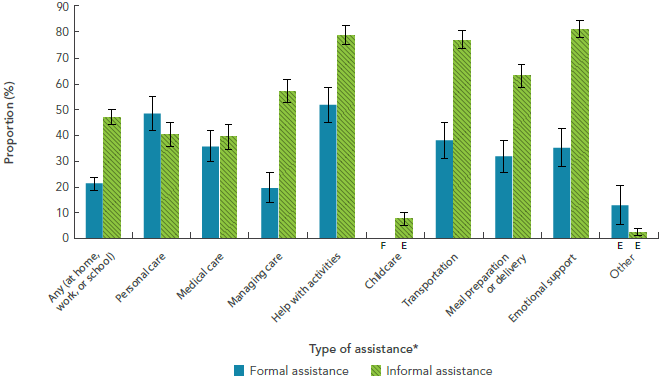

The usage of various types of formal and informal assistance, as noted by the SLNCC (excluding migraine), is shown in Figure 2-2 [16]. Most often, formal assistance was used for general help with activities (51.7%) or personal care (48.6%). Although not shown, when formal assistance was used, it was used frequently, at least once a week or daily, and was used in conjunction with informal assistance [10][16].

FIGURE 2-2: Formal and informal assistance use among respondents age 15+ years living with a neurological condition (excluding migraine), by type of assistance, Canada, 2011-2012, SLNCC 2011-2012 Project [16]

NOTES:

Data were weighted to represent the Canadian population living with a neurological condition and were based on self- or proxy-report. The 95% confidence interval shows an estimated range of values which is likely to include the true value 19 times out of 20.

- SLNCC

- Survey on Living with Neurological Conditions in Canada.

- *

- 'Type of assistance' was limited to the population receiving assistance. Categories were not mutually exclusive.

- E

- Interpret with caution; coefficient of variation between 16.6% and 33.3%.

- F

- Data were unreportable due to small sample size or high sampling variability.

SOURCE: 2011-2012 SLNCC data (Statistics Canada).

Text Equivalent - Figure 2-2

The bar graph shows the prevalence of self-reported formal and informal assistance use by Canadians living with a neurological condition but excluding migraine. On the horizontal axis, formal and informal assistance use are shown in separate categories for each of the types of assistance (any, personal care, medical care, managing care, help with activities, childcare, transportation, meal preparation or delivery, emotional support, and other). The vertical axis lists the proportion.

The population presented here was limited to only those who reported receiving assistance, and categories were not mutually exclusive. The use of informal assistance was typically much higher than formal assistance use for all types of assistance except for personal care and 'other' care, where formal assistance use was higher. Formal assistance was used most often for help with activities, with 51.7% of respondents reporting this type of assistance. Informal assistance was used most often for emotional support, with 81.3% of respondents reporting this type of assistance. Informal assistance was also high for help with activities (78.7%) and transportation (77.1%).

Data were from the 2011-2012 SLNCC from Statistics Canada. SLNCC stands for Survey on Living with Neurological Conditions in Canada. Data were weighted to represent the Canadian population living with a neurological condition and were based on self- or proxy-report. E signals that the reader should interpret the data with caution, because the coefficient of variation was between 16.6% and 33.3%. F signals that the data were unreportable due to small sample size or high sampling variability.

The table lists formal and informal assistance use for the various types of assistance under study:

| Type of assistance | Formal assistance (%) | Informal assistance (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Any (at home, work, or school) | 21.2 | 47.0 |

| Personal care | 48.6 | 40.4 |

| Medical care | 35.7 | 39.4 |

| Managing care | 19.6 | 57.2 |

| Help with activities | 51.7 | 78.7 |

| Childcare | F | 7.6 E |

| Transportation | 38.0 | 77.1 |

| Meal preparation or delivery | 31.9 | 63.0 |

| Emotional support | 35.2 | 81.3 |

| Other | 13.0 E | 2.5 E |

Canadians living with a neurological condition use health care services more often than those without that neurological condition. Investigators of the British Columbia (BC) Administrative Data Project [1] found that of individuals who sought health care services, those diagnosed with targeted neurological conditions had more hospital days, physician visits, prescriptions, and days in residential care compared to individuals without these neurological conditions:

- Acute hospital utilization: Per capita hospital days ranged from 2.2 days for women with multiple sclerosis to 64.7 days for men with spinal cord injury. This rate of utilization was 3.5 to 110 times higher for individuals with a specific neurological condition than for individuals without that condition in British Columbia during the fiscal year 2010/2011.Footnote 27,Footnote 28 The high per capita hospital days for those with brain and spinal cord injury likely reflected the length of time that individuals with these conditions spent in rehabilitation.Footnote 29

- Physician services utilization: Physician visits, a reflection of the utilization of services by individuals both in the community and in acute care hospitals, were 1.4 to 5.6 times higher among individuals with a neurological condition than among those without that condition in British Columbia in 2010/2011. Individuals that presented with spinal cord injury (92.9 visits for men), traumatic brain injury (79.5 visits for women), Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias (55.1 visits for men), and brain and spinal cord tumours (53.7 visits for men) had the greatest numbers of per capita physician visits.

- Prescription medication utilization: Use of prescribed medications, expressed as per capita dispensed prescription days, was highest in British Columbia in 2010/2011 for those with parkinsonism, which included Parkinson’s disease (1,689.9 prescription days for men; 1,952.2 for women). Usage of prescribed medications was similarly high for individuals with Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias (1,732.6 for men; 1,898.4 for women), and slightly lower for those with Huntington’s disease (1,348.0 for men; 1,522.1 for women) and anterior horn cell disease, which included ALS (1,080.1 for men; 1,277.5 for women). For all neurological conditions studied by the BC Administrative Data Project [1], women had higher dispensed prescription days compared to men.

- Residential care utilization: The number of days in residential care per capita was approximately three to 200 times higher among individuals with a specific neurological condition than among those without that condition in British Columbia in 2009/2010. The number of days in residential care was highest for individuals with Huntington’s disease (231.6 per capita days for men; 248.6 for women). Per capita days of residential care were also high for those with Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias (97.1 for men; 134.3 for women), cerebral palsy (80.0 for men, 81.3 for women), and parkinsonism (50.5 for men, 76.1 for women).

The interRAI Project [8] noted that individuals with a neurological condition also used more alternate level of care (ALC) days in hospital while awaiting nursing home placement. Approximately half of identified ALC patients had Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias, while parkinsonism was the next most common neurological condition, albeit present in less than 10% of ALC patients. Responsive or challenging behaviours were present in three quarters of ALC patients with Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias.

Based on results from the LINC Project [9], children living with a neurological condition also used the health care system more frequently. Although children with a neurological condition used generalist physician services at a level similar to Canadian children overall, those with a neurological condition were more likely to have a hospital stay, contact a specialist physician, receive mental health services, or consult with a social worker or counsellor.

The mental health service needs of Canadians living with a neurological condition are significant. The impacts of neurological conditions on the mental health of affected individuals were considerable (Chapter 1), and consequently led to an increased need for supportive care, where 34.8% of Canadians with a neurological condition reported receiving formal emotional support because of their condition [16].Footnote 30

The impacts of these medical conditions on every facet of our lives are enormous – who could possibly think that people living with a neurological condition wouldn't need mental health care?

~ Individual living with a neurological condition

In contrast to the documented use of mental health services, results from the Health Services Project [7] suggested that such needs were not always being adequately met. Based on results from an online survey completed by administrators of publicly-funded acute care hospitals, long-term care facilities, and community outpatient centres from all regions of Canada, 33% of respondents indicated that their facility did not accept patients with psychiatric diagnoses or severe behavioural disorders. Only 9% of these service providers had access to a neuropsychologist, and only 3% had access to a neuropsychiatrist.

The lack of neuropsychiatrists is a huge gap in the health care system. We also need more team-based care to enable one stop shopping.

~ Individual living with a neurological condition

2.2 Costs of health services for Canadians with a neurological condition are greater than for those without a neurological condition

Estimating costs of health services for Canadians with a neurological condition, relative to Canadians without these conditions, is a complex endeavour influenced by a variety of factors, which in turn may vary by jurisdiction. Certain projects of the Study [1][8][9][10] contributed new evidence on this issue, but these findings may be limited in their generalizability across Canada.

Total direct health care costs are high for Canadians living with a neurological condition. Total and per capita direct health care costs for 13 neurological conditions investigated in British Columbia for fiscal year 2010/2011 were three to 41 times higher among individuals diagnosed with any of the investigated neurological conditions compared to age-standardized data for individuals without those particular conditions (Table 2-1) [1].Footnote 31 The particularly high per capita costs seen for traumatic brain and spinal cord injuries were mostly associated with the hospital costs required for their treatment.

Large as these figures were, they underestimated the true costs for each condition because this project only had access to direct costs in addition to limited out-of-pocket expenses (which included prescription drugs not covered by British Columbia Pharmacare). Services provided by salaried physicians and many indirect costs (such as patient and caregiver time away from work or on long-term disability) could not be determined from the available data.

| Condition | Total direct health care cost ($)Footnote * | Per capita cost ($)Footnote † | Ratio of cost | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| with the specified neurological condition | without the specified neurological condition | with/without the specified neurological condition | ||

| Alzheimer's disease and other dementias | 527,494,000 | 5,200 | 1,700 | 3.0 |

| Anterior horn cell disease | 8,405,000 | 13,000 | 1,800 | 7.1 |

| Brain injury (traumatic) | 86,839,000 | 26,900 | 1,800 | 14.6 |

| Brain tumour (malignant) | 25,624,000 | 13,200 | 1,800 | 7.2 |

| Cerebral palsy | 50,520,000 | 6,100 | 1,800 | 3.4 |

| Epilepsy | 208,679,000 | 5,800 | 1,800 | 3.2 |

| Huntington's disease | 2,160,000 | 10,800 | 1,900 | 5.8 |

| Hydrocephalus | 44,923,000 | 12,000 | 1,800 | 6.6 |

| Multiple sclerosis | 70,462,000 | 6,900 | 1,800 | 3.7 |

| Muscular dystrophy | 4,257,000 | 11,300 | 1,800 | 6.2 |

| Parkinsonism | 120,358,000 | 11,100 | 1,800 | 6.0 |

| Spina bifida | 7,009,000 | 9,200 | 1,800 | 5.0 |

| Spinal cord injury | 17,720,000 | 75,200 | 1,800 | 40.6 |

NOTES:

SOURCE: Population Health Surveillance and Epidemiology, British Columbia Ministry of Health (September 2011). |

||||

Another project also demonstrated that the costs of caring for individuals with a neurological condition in home care programs or in chronic care facilities were greater than those for individuals with other conditions [8].

We have spent a lot of money on mobility equipment and supplies. Home modifications are very expensive. We don’t go on vacation.

~ Individual living with a neurological condition

Average out-of-pocket expenses are high. Sixty percent of respondents in the LINC Project [9] reported out-of-pocket costs for prescribed medications, despite the fact that 85% of the sample reported having a drug insurance plan. Nearly 20% had paid more than $1,000 in out-of-pocket expenses in the previous year. Questions about average annual out-of-pocket expenses per respondent were also part of the SLNCC,Footnote 32 but estimates were likely much lower than the true costs actually experienced by Canadians, since average costs do not reflect individual experiences (Table 2-2).

| Condition | Annual out-of-pocket cost per respondent ($) |

|---|---|

| Alzheimer's disease and other dementias | 1,000 |

| Brain injury (traumatic) | 800 |

| Epilepsy | 500 |

| Multiple sclerosis | 1,000Footnote E |

| Spinal cord injury (traumatic) | 1,200 |

| Parkinson's disease | 1,100 |

| Stroke | 800 |

NOTES: Data were rounded to the nearest hundred.

SOURCE: 2011-2012 SLNCC data (Statistics Canada) provided by POHEM-Neurological (Statistics Canada and Public Health Agency of Canada). |

|

The British Columbia PharmaNet database provided information about the costs of medications not covered by British Columbia Pharmacare, although self-paid and third-party payments were not separable. For three neurological conditions in 2010/2011, these costs (out-of-pocket, at least in part) were more than $1,000: brain tumour - $1,095 (age-standardized comparison group without the condition - $313); multiple sclerosis - $1,270 (comparison group - $311); and parkinsonism - $1,071 (comparison group - $311) [1].

Money for food, rent, or prescriptions should not be a decision faced by people with disabilities on a regular basis.

~ Individual living with a neurological condition

Funds are available in my province for home renovations, but they’re hard to get.

~ Informal caregiver

2.3 Limitations in health care services have been identified

To assess the provision of health services in Canada, the Health Services Project [7] aimed to identify needs, gaps, current policies, and best practices. This project performed a literature review of 723 articles, held structured interviews with 180 key informants from across Canada (39% health care professionals, 47% non-health care professionals, and 14% policy makers), and conducted an online survey completed by administrators in 645 of the 2,783 publically-funded health care facilities in Canada (acute care hospitals, long-term care facilities, community outpatient centres, and home care organizations).

The scoping review and key informant interviews documented a lack of knowledge or awareness regarding neurological conditions among service providers and a limited availability of much needed services for Canadians living with a neurological condition, particularly for those living in rural areas.

Families often know more about neurological conditions than health professionals. Many times a family member or a voluntary health organization representative needs to be with an affected individual. This is an added burden for families and patients.

~ Individual living with a neurological condition

More health services are available for common neurological conditions than for rare conditions. A high proportion of care providers offered services for individuals with stroke (71%), Parkinson’s disease (65%), Alzheimer’s disease (65%), traumatic brain injury (59%), and multiple sclerosis (57%). However, only a small proportion of care providers reported services for individuals with less common conditions such as dystonia (28%), Tourette syndrome (17%), or Rett syndrome (13%).

The availability of certain support services is limited. There was a lack of information on, and services for, education or return to school, employment, family and caregiver support, housing, and transportation. Informed by their interviews with service providers and policy makers, the Health Services Project [7] team developed a ‘chronic care model for neurological conditions’. This model provided the vision for a comprehensive system change, aimed at improving the quality of life for individuals living with these conditions and increasing collaboration between the health system, the community, and the socioeconomic and political sectors.

Access to services for individuals with a neurological condition is sometimes limited by exclusion criteria. Although data could not be differentiated by type of facility, most service providers reported exclusion criteria for accessing their services. This may have been appropriate if the service provider was not equipped to address the needs of the patient. In addition to 33% of reporting facilities having exclusion criteria for psychiatric diagnoses, severe behavioural disorders, or for substance abuse or substance dependence, a further 32% of reporting facilities reported exclusions for medical instability, degenerative medical conditions, or the presence of comorbidities, while 21% reported exclusions on the basis of age. Only 28% of service providers reported no exclusion criteria. It was noted that the implementation of these criteria may not only vary by facility, but may also vary by health sector or jurisdiction.

Service delivery is affected by resource allocation and by the physical environment. Nearly half (47%) of service providers cited staff ratios and 37% cited physical environment as barriers to their ability to adequately provide services.

What about the stigma with healthcare professionals at the general practitioner level? They don’t want you. You could be a difficult client and take up a lot of time.

~ Individual living with a neurological condition

2.4 Canadians with a neurological condition and their informal caregivers typically rate the adequacy of health services lower than do their health care providers

The Health Services Project [7] compared the perspectives of 100 LINC Project [9] participants with the perspectives of 100 health care providers. Individuals from each group were questioned about the perceived adequacy of various aspects of health care services,Footnote 33 with a qualitative rating scale of providing: ‘little or no’, ‘basic or intermediate’, ‘advanced’, or ‘optimal’ support. Overall, Canadians living with a neurological condition (or their caregivers) rated health care services lower than did service providers; mean scores given by patients were all in the ‘little or no’ to ‘basic or intermediate’ support ranges, while provider’s scores were in the ‘basic or intermediate’ to ‘advanced’ range.

Improvements are required for goal setting and continuity of care. Goal setting, follow-up, and coordination received the lowest rankings by patients, with mean scores that indicated ‘little or no’ support. Health care providers also gave their lowest score to this aspect of health care services, but their ratings were in the ‘basic or intermediate’ range.

There really isn’t a system: the transition points just aren’t there. People are operating independently in silos. So each time you go somewhere new you have to do a new assessment. No one trusts the previous one.

~ Health care provider

Integrated multidisciplinary care is important. Neither patients nor health care providers rated any aspect of service provision as ‘optimally integrated’ for chronic illness. About a third of respondents in the LINC Project [9] reported having access difficulties when seeking a specialist appointment. The Health Services Project [7] also demonstrated gaps in access to, and availability of, current services to support transitions between settings (e.g. pediatric to adult, community to long-term care) and reiterated the existing need to address social determinants of health such as education, employment, housing and transportation.

When kids turn 18 they fall off the cliff. The adult system is fragmented and is based on episodic care for chronic conditions.

~ Health care provider

Satisfaction is high for some health services. In general, high levels of overall satisfaction were expressed by the 30% of LINC Project [9] respondents who accessed community-based services. Also, a sample of 104 parents of children with cerebral palsy rated the services their children had received quite highly using the Measure of Process of Care questionnaire [4].Footnote 34

2.5 An obligation is placed on family and friends to provide care

You have to take on so many roles: be a medical expert, put on makeup, style hair, be both hands on and philosophical.

~ Informal caregiver

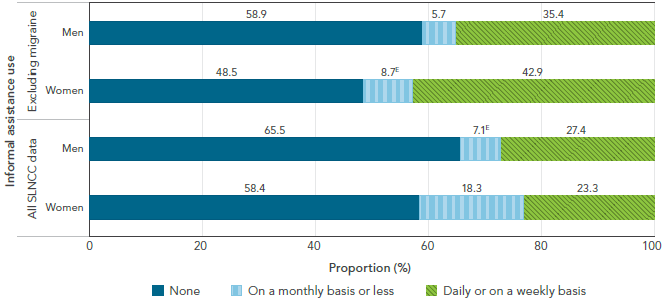

Care provided by family, friends, and neighbours, termed ‘informal caregiving’ throughout the Study, is an important service required and received by many individuals with a neurological condition. Almost half (45%) of LINC respondents reported that they received informal care [9]. At a national level, 39.6% of Canadians with a neurological condition (excluding migraine) received informal assistance that included general help with activities (78.7%), transportation (77.1%), and meal preparation and delivery (63.0%) (Figure 2-2, section 2.1) [16]. Among Canadians living with a neurological condition (excluding migraine), 81.3% were receiving informal assistance for emotional support, which was the most frequently reported category. Excluding migraine, women were more likely to use informal assistance compared to men. When migraine was also considered, the proportion of informal assistance used on a monthly basis or less increased for both men and women (Figure 2-3).

When I go shopping, I have to take both my mother, who has dementia, and my 18-year-old daughter, who has a severe intellectual handicap, with me. I rely on my healthy 8-year-old son to keep them from wandering off while I am at the check-out or getting the car from the parking lot.

~ Informal caregiver

FIGURE 2-3: Frequency of informal assistance use among respondents age 15+ years living with a neurological condition (including and excluding migraine), by sex, Canada, 2011-2012, SLNCC 2011-2012 Project [16]

NOTES:

Data were weighted to represent the Canadian population living with a neurological condition and were based on self- or proxy-report.

- SLNCC

- Survey on Living with Neurological Conditions in Canada.

- E

- Interpret with caution; coefficient of variation between 16.6% and 33.3%.

SOURCE: 2011-2012 SLNCC data (Statistics Canada).

Text Equivalent - Figure 2-3

The bar graph shows the distribution of informal assistance use by sex for Canadians living with a neurological condition (including and excluding migraine). Informal assistance use is shown in three categories (none, on a monthly basis or less, and daily or on a weekly basis). On the graph, the horizontal axis shows how the population is divided into these three categories and adds to 100%, and the vertical axis lists the population with a neurological condition, including and excluding migraine, by sex.

Women always used more informal assistance than men, but men used it more frequently (on a daily or weekly basis instead of on a monthly basis or less). When migraine was included, the use of informal assistance was not as high as when migraine was excluded from analysis.

Data were from the 2011-2012 SLNCC from Statistics Canada. SLNCC stands for Survey on Living with Neurological Conditions in Canada. Data were weighted to represent the Canadian population living with a neurological condition and were based on self- or proxy-report. E signals that the reader should interpret the data with caution, because the coefficient of variation was between 16.6% and 33.3%.

The table lists the distribution of informal assistance use by category (none, on a monthly basis or less, and on a daily or weekly basis) by sex and including and excluding migraine:

| Frequency | All SLNCC data | Excluding migraine | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women (%) | Men (%) | Women (%) | Men (%) | |

| None | 58.4 | 65.5 | 48.5 | 58.9 |

| On a monthly basis or less | 18.3 | 7.1 E | 8.7 E | 5.7 |

| Daily or on a weekly basis | 23.3 | 27.4 | 42.9 | 35.4 |

2.6 Information concerning the health service needs for children with a neurological condition is limited

Although data concerning health services for children with a neurological condition were scarce in the Study, available findings suggested that health services for some children may have been sub-optimal or would have benefited from clearer care pathways.

Children living with a neurological condition require regular use of health services, but these services are sometimes lacking. It was estimated that a fifth of children with a neurological condition in the LINC Project [9] had not seen a general practitioner or pediatrician in the previous year, and only two-thirds had received specialist physician care. Children with newly diagnosed cerebral palsy utilized a range of rehabilitation services [4], but it was noted that services such as these were often not available when a condition was long-standing or if the condition was combined with a cognitive impairment [8]. In general, the Health Services Project [7] survey of providers found that there were fewer services offered for children (age 0 to 17 years) when compared to those available to adults.

Kids growing up with neurological conditions have a different life experience. And my needs as a parent are different from parents taking care of individuals with spinal cord injury or spina bifida.

~ Informal caregiver

2.7 The health service needs for First Nations and Métis individuals with a neurological condition pose unique challenges

The NWAC Project [11] team identified several challenges met by First Nations and Métis individuals requiring health care services for neurological conditions. They included the following:

- The lack of accessible specialized health care and diagnostic services in northern, rural, or remote locations;

- Transportation to health care services, especially for individuals living in remote areas;

- Difficulties navigating the health system in relation to which level of government was responsible;

- Lack of support and training for families with a member affected by a neurological condition;

- The need for better cultural competence among health care providers;

- The lack of understandable information regarding neurological conditions; and

- The need for greater awareness in First Nations and Métis populations about neurological conditions to address stigma associated with these conditions.

We go to case conferences where the doctor makes a treatment plan for one of us with a neurological condition. But it’s not carried out up north because there’s really nothing up there – especially for young people and elders.

~ NWAC Project participant

Overcoming these challenges would entail actions such as working more closely with First Nations and Métis individuals, increasing the availability of services in their respective communities, instituting holistic approaches to healing, providing opportunities for traditional ceremonies and gatherings, and making advocates or guides available to First Nations and Métis individuals accessing the health care system.

Many Aboriginal people don’t trust – and therefore don’t use – mainstream health care services because they don’t feel safe from stereotyping and racism, and because the Western approach to health care can feel alienating and intimidating.

~ NWAC Project participant

2.8 The prediction and evaluation of health care needs can be informed by Study findings

Comprehensive assessment tools, such as the interRAI suite of assessment instruments, can improve accuracy when defining the care needs of individuals with chronic neurological conditions rather than basing decisions on diagnostic information alone. For example, the interRAI Project [8] noted that health care needs in chronic care settings were better defined by the type of functional impairment rather than by diagnostic category.

Focusing on function rather than diagnosis is where we should start with system change for people with neurological conditions. Once this is in place, the rest will evolve.

~ Health care provider

Other projects of the Study also identified areas that merit further evaluation. By using data extracted from the electronic medical records (EMRs) of primary care physicians, the EMR Project [6] determined that significant numbers of patients with dementia or parkinsonism were not being prescribed potentially beneficial condition-specific medications by their primary care physicians. With respect to rehabilitative services, the interRAI Project [8] found that the combination of a neurological condition and cognitive impairment was a significant barrier, where individuals with cognitive impairment were less likely to receive occupational therapy and life skills training than individuals without cognitive impairment.

2.9 Looking ahead: 2011 to 2031

Results from the Microsimulation Project [10], which are based on status quo assumptions,Footnote 35 project that:

- Total annual health care costs for individuals age 40 years and older with Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias and Parkinson’s disease/parkinsonism will double between 2011 and 2031. For the other five modelled neurological conditions, direct health care costs will increase, but not as significantly.

- Acute hospitalizations will remain as the largest contributor to total direct health care costs for all the modelled neurological conditions except for Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias, where facilities-based long-term care will remain as the largest contributor.

- By 2031, total direct health care costs for Canadians with the seven modelled neurological conditions will be, depending on the condition, $0.6 billion to $13.3 billion greater than the health care costs of Canadians without these conditions. Thus, if within the next 20 years, innovations in care, prevention, and treatment allowed health care utilization by Canadians with the modelled neurological conditions to move toward the utilization seen in those without these conditions, a substantial amount of health care resources could be used to meet other needs.

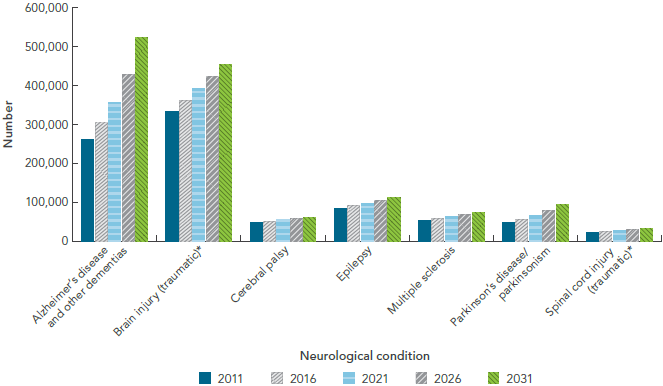

- Based on health status (defined by HUI-3 scores rather than unmet care needs), the numbers of Canadians with Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias or Parkinson’s disease/parkinsonism who are likely candidates for informal care will nearly double in the next 20 years (Figure 2-4). For other conditions modelled in the Microsimulation Project [10], the need for informal care is expected to rise moderately. Given current sociodemographic changes in Canada (such as smaller families and greater geographic dispersion) it is likely that innovative changes will be required to meet these increased care demands.

If dementia doubles in 20 years as has been predicted, we need to know where people are going to go, and what each one costs in terms of resources, implications for rehabilitation, and quality of life.

~ Individual living with a neurological condition

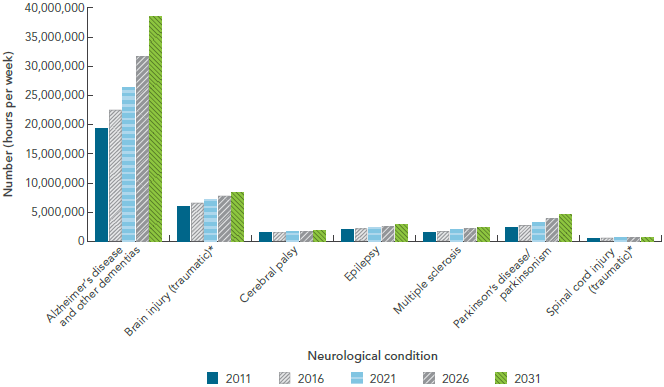

FIGURE 2-4: Projected number of Canadians who are likely candidates for informal care, by select neurological condition, Canada, 2011, 2016, 2021, 2026, and 2031, Microsimulation Project [10]

NOTES:

- *

- Traumatic brain and spinal cord injuries were based on hospitalized cases, and excluded injuries that did not present to hospital.

SOURCE: POHEM-Neurological (Statistics Canada and Public Health Agency of Canada).

Text Equivalent - Figure 2-4

The bar graph is a complex display showing the projected number over time of Canadians living with select neurological conditions who will require informal care. On the graph, the horizontal axis has two components: first, there are seven neurological conditions listed (Alzheimer's disease and other dementias, brain injury, cerebral palsy, epilepsy, multiple sclerosis, Parkinson's disease/parkinsonism, and spinal cord injury). Second, for each neurological condition, it shows five time periods (2011, 2016, 2021, 2026, and 2031). The vertical axis lists the total number.

For all neurological conditions under study, the projected number of Canadians requiring informal care increased in a stepwise fashion. The projected number requiring care was highest for those living with Alzheimer's disease and other dementias, and showed a large increase in 2031 to 522,000, which is double the number seen in 2011. The projected number requiring care was lowest for those living with spinal cord injury, which showed little increase over time.

Data were from the POHEM-Neurological modelling platform from Statistics Canada and Public Health Agency of Canada. Traumatic brain and spinal cord injuries were based on hospitalized cases, and excluded injuries that did not present to hospital.

The table lists the number of Canadians requiring informal care over time for each of the neurological conditions under study:

| Neurological condition | 2011 | 2016 | 2021 | 2026 | 2031 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alzheimer's disease and other dementias | 261,414 | 304,061 | 356,045 | 428,689 | 522,213 |

| Brain injury (traumatic; hospitalized) | 333,832 | 362,366 | 392,145 | 422,422 | 453,824 |

| Cerebral palsy | 48,254 | 51,020 | 54,481 | 58,254 | 61,797 |

| Epilepsy | 84,265 | 91,082 | 97,708 | 104,882 | 113,049 |

| Multiple sclerosis | 52,412 | 58,667 | 64,285 | 69,352 | 73,224 |

| Parkinson's disease/parkinsonism | 48,886 | 56,831 | 66,977 | 79,821 | 94,684 |

| Spinal cord injury (traumatic; hospitalized) | 23,310 | 25,534 | 27,804 | 30,482 | 32,297 |

- Although data are not shown, the number of hours of informal care needed each week by an individual living with one of the seven modelled neurological conditions will remain relatively stable in 2031 compared to 2011, where an estimated average of 18 hours of informal care per week is required for those with hospitalized traumatic brain injury, while 74 hours per week is required for those with Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias.

- The total number of hours of informal care provided per week is substantial, and is projected to increase over the next 20 years for all seven modelled neurological conditions (Figure 2-5). In particular, while the number of hours of informal care provided per week for Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias is already significantly higher when compared to the other modelled conditions, this number is expected to double by 2031.

FIGURE 2-5: Projected number of hours of informal caregiving per week, by select neurological condition, Canada, 2011, 2016, 2021, 2026, and 2031, Microsimulation Project [10]

NOTES:

- *

- Traumatic brain and spinal cord injuries were based on hospitalized cases, and excluded injuries that did not present to hospital.

SOURCE: POHEM-Neurological (Statistics Canada and Public Health Agency of Canada).

Text Equivalent - Figure 2-5

The bar graph is a complex display showing the projected number of hours of informal caregiving provided per week for a selection of neurological conditions. On the graph, the horizontal axis has two components: first, there are seven neurological conditions listed (Alzheimer's disease and other dementias, brain injury, cerebral palsy, epilepsy, multiple sclerosis, Parkinson's disease/parkinsonism, and spinal cord injury). Second, for each neurological condition, it shows five time periods (2011, 2016, 2021, 2026, and 2031). The vertical axis lists the total number representing hours per week.

For all neurological conditions under study, the projected number of hours per week spent providing informal care increased in a stepwise fashion except for spinal cord injury, which remained fairly flat over time. The projected number of hours per week spent providing informal care was highest for those living with Alzheimer's disease and other dementias, and increased from 19 million in 2011 to 39 million in 2031. The projected number of hours per week spent providing informal care was lowest for those living with spinal cord injury, and ranged from 486,000 in 2011 to 702,000 in 2031.

Data were from the POHEM-Neurological modelling platform from Statistics Canada and Public Health Agency of Canada. Traumatic brain and spinal cord injuries were based on hospitalized cases, and excluded injuries that did not present to hospital.

The table lists the number of hours per week spent providing informal care for each of the neurological conditions under study:

| Neurological condition | 2011 | 2016 | 2021 | 2026 | 2031 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alzheimer's disease and other dementias | 19,235,612 | 22,458,177 | 26,277,847 | 31,579,388 | 38,524,969 |

| Brain injury (traumatic; hospitalized) | 5,973,190 | 6,534,886 | 7,112,350 | 7,732,292 | 8,347,794 |

| Cerebral palsy | 1,431,843 | 1,504,951 | 1,615,502 | 1,725,412 | 1,827,497 |

| Epilepsy | 1,950,742 | 2,144,243 | 2,324,204 | 2,541,001 | 2,829,843 |

| Multiple sclerosis | 1,478,236 | 1,715,027 | 1,937,694 | 2,155,617 | 2,286,601 |

| Parkinson's disease/parkinsonism | 2,358,369 | 2,741,609 | 3,230,859 | 3,837,186 | 4,592,978 |

| Spinal cord injury (traumatic; hospitalized) | 485,623 | 541,456 | 593,855 | 657,873 | 702,239 |

- Out-of-pocket costs for caregivers will remain stable, ranging from approximately $1.7 thousand annually per individual living with epilepsy, to approximately $4.6 thousand annually per individual living with Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias. These projections could be affected by changes in policy concerning universally insured health care.

2.10 Knowledge gaps

Individual Study projects were limited in their coverage of health services for every Canadian jurisdiction, and were not designed to fully ascertain the wide range of out-of-pocket costs that individuals may accrue because of their neurological condition. Specifically, health service gaps were identified, such as:

- The inconsistent availability of multidisciplinary care;

- The application of eligibility criteria, especially restrictions on the provision of care for individuals with mental health disorders, and an assessment of the burden that these restrictions place on patients with a neurological condition compared to those without a neurological condition.

Data on health services for Canadians living with a neurological condition were lacking or deficient regarding:

- The distribution and quality of health services across the various regions and jurisdictions of Canada;

- The current costs of providing care for individuals with a neurological condition in continuing care (home care programs, long-term care facilities) as well as in acute care settings across the country;

- The personal cost of medications for individuals with each neurological condition, especially given that all provincial and territorial drug plans involve co-payments;

- The perceptions of health care providers on the accessibility, timeliness, and quality of health services for individuals with a neurological condition;

- The provision of health care for First Nations, Inuit, and Métis populations, for vulnerable populations, and for children with a neurological condition.

Applying the best currently available knowledge gained from Study projects, such as addressing potential barriers in access to care or the physical and mental health needs identified by Canadians living with a neurological condition, can help improve the adequacy of the health care system for individuals navigating through the care options for their neurological condition.

2.11 Key themes

In this chapter, which examined existing health services for individuals living with or affected by a neurological condition in Canada, it was noted that:

- Community-based services as well as hospital-based health care programs and resources are both important components of effective health service delivery.

- Many of those with a neurological condition receive extensive services from informal caregivers, and these caregivers often require emotional and financial support.

- Cultural background and language must be considered in the delivery of health care services for individuals with a neurological condition.

- Functional ability, as well as diagnosis, needs to be considered when developing care plans for individuals living with a neurological condition.

- Individuals with milder forms of neurological conditions also have specific needs that require recognition and support.

- It is important to recognize the impact and complexities of mental health comorbidities in individuals with a neurological condition and their caregivers. Currently, there are insufficient services and service providers to address the coexistence of mental health disorders and neurological conditions, in spite of evidence documenting this need.

- Individuals with a neurological condition need transition support as they move along the continuum of care, which is often directed by the progression of their condition.

- Individuals with a neurological condition would benefit from the current moves in some jurisdictions to modify chronic care; these changes could be guided by models, such as the recently developed revised chronic care model that incorporates environmental, social, and educational factors.

- The utilization and cost of drugs, including co-payments, is a significant component of overall health care costs, both for individuals living with a neurological condition and for the health care system.

Microsimulation modelling of seven neurological conditions projects that by 2031:

- Total annual health care costs (direct costs) will increase for each of the seven modelled neurological conditions, and will be twice as high for Canadians age 40 years and older with Alzheimer's disease and other dementias and Parkinson's disease/parkinsonism.

- Acute hospitalizations will continue to be the largest contributor to total direct health care costs for all the modelled neurological conditions except Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias, where facilities-based long-term care will remain as the largest contributor.

- Increased numbers of Canadians with the seven modelled neurological conditions will become likely candidates for informal care (based on their health status as defined by their HUI-3 score), and for those with Alzheimer's disease and other dementias and Parkinson's disease/parkinsonism, the number of candidates for informal care will nearly double.