Chapter 3: Mapping Connections: An understanding of neurological conditions in Canada – Scope (prevalence and incidence)

3. Scope (prevalence and incidence) of neurological conditions

To best address the health impacts (Chapter 1) and health service needs (Chapter 2) of Canadians living with a neurological condition as well as their families and caregivers, program and policy planning is informed by different types of evidence. Understanding the magnitude of neurological conditions in Canada, in terms of how many Canadians are living with these conditions, constitutes a core piece of this process.

The data from the Study are so important – without solid numbers, asking for program funding is based on anecdotal reports. Now there is so much more.

~ Volunteer, health organization employee

In this Study, projects focusing on the prevalence (extent of the population affected) and incidence (new occurrence) of neurological conditions in Canada were carried out to document the burden of these conditions [1][2][3][4][5][6][8][10][12][15][17][18]. A wide range of data sources and methods for estimating prevalence and incidence were used, each with strengths and limitations. Assessing the validity and reliability of prevalence and incidence estimates from these different data sources – systematic reviews and meta-analyses, health administrative databases, EMRs, surveys, and microsimulation models – provided important information for the surveillance and monitoring of neurological conditions in Canada. In this chapter, findings were generally referred to as 'estimates', because their calculation was based on samples of the population, and not on the entire population.

3.1 Determining prevalence and incidence estimates of neurological conditions is complex

The Study produced the first reliable Canadian prevalence and incidence estimates for many of the targeted neurological conditions. Because systematic reviews of the published literature identified few Canadian studies presenting prevalence and incidence for the neurological conditions targeted in the Study [18], the prevalence and incidence data produced by individual Study projects resulted in novel information for many of these neurological conditions in a Canadian context. Confidence in prevalence or incidence estimates is strengthened if they are confirmed by more than one source; as such, these new estimates were compared to estimates based on meta-analyses of studies (mostly from outside of Canada) that met predetermined criteria for quality and homogeneity. Canadian prevalence estimates produced by Study projects are presented in Table 3-1 by data source, and are positioned relative to the findings derived from meta-analyses. Table 3-2 provides new prevalence estimates of neurological conditions specific to Canadians living in long-term care facilities.

Critically assessing new estimates of prevalence and incidence

- Meta-analyses as a comparator: By combining data from multiple published studies, meta-analyses have the potential to generate a prevalence or incidence estimate that is more precise than that of a single study. The precision of such estimates is dependent on the quality and uniformity of the studies included in the meta-analyses. If the 95% confidence interval of a new estimate generated by this Study overlaps with the 95% confidence interval of the meta-analysis estimate, it may support the value of this new estimate. If the 95% confidence interval of the new estimate generated by this Study only overlaps with the range of estimates included in the meta-analysis, then this new estimate may need to be used with caution. New estimates that are outside of the ranges seen in published data may be of questionable reliability, because they currently cannot be confirmed by other data sources.

- Variations in estimates: For some neurological conditions, wide variations in estimates exist. Part of this variance may be due to differences in methodology, populations studied, case ascertainment, or definitions used. Differences in incidence and prevalence of these neurological conditions may also be influenced by environmental, geographic, genetic, or demographic factors.

| Meta-analyses and systematic reviewsTable 3-1 Footnote 1 (worldwide unless otherwise specified) |

Administrative dataTable 3-1 Footnote 2 (British Columbia) |

Survey dataTable 3-1 Footnote 3 (Canada) |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prevalence range in individual studies (rate per 100,000 population) |

Number of studies included | Pooled point prevalence | Period prevalence | Weighted period prevalence | |||||

| Rate per 100,000 population | (95% confidence interval) | Rate per 100,000 population |

(95% confidence interval) | Rate per 100,000 population | (95% confidence interval) | ||||

| Alzheimer's disease and other dementias | |||||||||

| Community, age 65+ years | 800-37,218 | 29 | 5,234 | (4,142-6,613) | - | - | 2,130 | (1,910-2,340) | |

| Community and long-term care facilities, age 65+ years | 1,948-64,706 | 13 | 15,544 | (9,070-26,638) | 7,594.6 | (7,540.9-7,648.6) | - | - | |

| Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS or Lou Gehrig's disease) | |||||||||

| 1.6-7.9 | 5 | 4.4 | (2.7-7.2) | 10.2Table 3-1 Footnote 4 | (9.5-11.0) | 10Table 3-1 Footnote E | (10-20) | ||

| Brain injury (traumatic) | |||||||||

| 2,136-5,700 | 2 | 3,490.1Table 3-1 Footnote 5 | (1,333.9-9,131.6) | 835.6 | (827.1-844.2) | 410 | (380-450) | ||

| Brain tumour | |||||||||

| 130.8-221.8Table 3-1 Footnote 5 | 2 | - | - | 38.1Table 3-1 Footnote 6 | (36.4-39.8) | 140Table 3-1 Footnote 7 | (120-160) | ||

| Cerebral palsy | |||||||||

| 110-390 | 28 | 211Table 3-1 Footnote 8 | (198-225) | 191.9Table 3-1 Footnote 9 | (187.5-196.3) | 130 | (110-150) | ||

| Dystonia | |||||||||

| 10.1-37.1 | 5 | 16.4Table 3-1 Footnote 10 | (12.1-22.3) | - | - | 40 | (30-50) | ||

| Epilepsy | |||||||||

| Overall | 321-1,550 | 33 | 746 | (678-817) | 1246.2Table 3-1 Footnote 9 | (1,235.8-1,256.6) | - | - | |

| Active | 73-10,500 | 93 | 596 | (538-661) | - | - | 400 | (360-430) | |

| Huntington's disease | |||||||||

| 1.6-12.7 | 10 | 5.7Table 3-1 Footnote 11 | (4.4-7.4) | 4.0 | (3.6-4.5) | 10Table 3-1 Footnote E | (10-10) | ||

| Hydrocephalus | |||||||||

| All | 30.7-310.1 | 7 | 93.0 | (51.4-168.4) | 74.7Table 3-1 Footnote 9 | (72.2-77.2) | - | - | |

| Age <4 years | - | - | - | - | 76.0 | (63.8-89.8) | 70Table 3-1 Footnote e | (30-110) | |

| SeniorsTable 3-1 Footnote 12 | 198.7-350.3 | 3 | 238.6 | (146.3-389.2) | 139.8 | (130.9-148.8) | 40Table 3-1 Footnote e | (20-60) | |

| Migraine | |||||||||

| - | - | - | - | - | - | 8,270 | (8,100-8,450) | ||

| Multiple sclerosis | |||||||||

| 40-298 | 10 | 208.4Table 3-1 Footnote 13 | - | 177.4 | (174.1-180.8) | 290 | (260-320) | ||

| Muscular dystrophy | |||||||||

| 6.3-25.5 | 5 | 16.1Table 3-1 Footnote 14 | (11.2-23.2) | 106.8Table 3-1 Footnote 15 | (104.0-109.5) | 70 | (60-90) | ||

| Parkinson's diseaseTable 3-1 Footnote 16 | |||||||||

| Age group (years) | All | 405-19,030 | 47 | - | - | 147.0Table 3-1 Footnote 9 | (144.0-150.1) | 170 | (140-200) |

| 40+ | - | - | - | - | 342.0 | (334.6-349.5) | 330 | (280-380) | |

| 45+ | - | - | - | - | 396.6 | (387.9-405.3) | 390 | (330-450) | |

| 40 to 49 | - | - | 40.5 | (20.3-81.0) | 26.9 | (23.1-30.7) | Table 3-1 Footnote F | Table 3-1 Footnote F | |

| 50 to 59 | - | - | 106.7 | (53.9-211.2) | 79.5 | (72.8-86.2) | 90Table 3-1 Footnote E | (60-120) | |

| 60 to 69 | - | - | 428.5 | (235.5-779.8) | 301.5 | (285.8-317.1) | 410Table 3-1 Footnote E | (260-560) | |

| 70 to 79 | - | - | 1,086.5 | (627.0-1,883.0) | 913.4 | (878.1-948.7) | 1,030 | (810-1,240) | |

| 80+ | - | - | 1,903.0 | (1,132.2-3,198.4) | 1,697.7 | (1,640.4-1,754.9) | 1,420 | (1,050-1,790) | |

| Spina bifida | |||||||||

| Folate intake unknown | 1.4-580.8 | 147 | 46.4Table 3-1 Footnote 5 | (42.2-51.0) | 17.0Table 3-1 Footnote 9 | (15.7-18.4) | 110 | (90-120) | |

| Folate supplemented | 1.4-82.1 | 13 | 25.1Table 3-1 Footnote 5 | (19.9-31.7) | - | - | - | - | |

| Spinal cord injury (traumatic) | |||||||||

| - | 1 | 3.7 | - | 67.3 | (65.1-69.7) | 360 | (330-400) | ||

| Spinal cord tumour | |||||||||

| - | - | - | - | 38.1Table 3-1 Footnote 6 | (36.4-39.8) | 30 | (20-30) | ||

| Stroke | |||||||||

| - | - | - | - | - | - | 980 | (920-1,030) | ||

| Tourette syndrome | |||||||||

| Age groups (years) | 0+ | - | - | - | - | - | - | 100 | (80-120) |

| 6 to 15 | 100-5,260 | 13 | 770 | (390-1,510) | - | - | 370 | (260-480) | |

| 0 to 17 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 250 | (180-310) | |

NOTES:

|

|||||||||

| Weighted period prevalence | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | Women | |||

| Rate per 100,000 population | (95% confidence interval) | Rate per 100,000 population | (95% confidence interval) | |

| Full SNCIC sample | 61,760 | (60,580-62,950) | 66,440 | (65,250-67,630) |

| Alzheimer's disease and other dementias | 36,910 | (36,020-37,800) | 49,150 | (48,150-50,140) |

| ALS | 130 | (110-160) | 70 | (60-90) |

| Brain injury (traumatic) | 3,710 | (3,520-3,900) | 1,240 | (1,150-1,340) |

| Brain or spinal cord tumour | 410 | (320-510) | 390 | (270-500) |

| Cerebral palsy | 2,410 | (2,270-2,560) | 1,230 | (1,150-1,310) |

| Dystonia | 300 | (250-350) | 210 | (170-240) |

| Epilepsy | 5,710 | (5,470-5,950) | 3,160 | (3,040-3,290) |

| Huntington's disease | 290 | (260-330) | 220 | (190-240) |

| Hydrocephalus | 620 | (560-680) | 350 | (310-380) |

| Multiple sclerosis | 1,300 | (1,200-1,400) | 1,540 | (1,450-1,620) |

| Muscular dystrophy | 310 | (260-370) | 120 | (90-150) |

| Parkinson's disease | 6,300 | (6,090-6,510) | 3,950 | (3,820-4,080) |

| Spina bifida | 190 | (160-230) | 130 | (110-150) |

| Spinal cord injury (traumatic) | 770 | (690-850) | 290 | (250-320) |

| Stroke | 16,500 | (16,050-16,960) | 14,430 | (14,060-14,800) |

| Tourette syndrome | 290 | (260-320) | 50 | (40-60) |

NOTES:

SOURCE: 2011–2012 SNCIC data (Statistics Canada). |

||||

Administrative data are a valid source of prevalence data. Using a well-established Ontario database that links EMRs to administrative data, the Ontario (ON) Administrative Data Project [12] team carried out groundwork for the use of administrative data in the surveillance of neurological conditions. By identifying patients with certain neurological conditions using EMR data and then developing algorithms to capture these patients with administrative data, the ON Administrative Data Project [12] produced validated case definitions for Alzheimer's disease and other dementias, epilepsy, multiple sclerosis, and parkinsonism. This, in part, informed the work performed by the BC Administrative Data Project [1] team (Table 3-1).

Based on findings from British Columbia health administrative data, prevalence estimates for most neurological conditions were concordant with those obtained by systematic reviews and meta-analyses [1][18]. Ontario estimates for Alzheimer's disease and other dementias, epilepsy, multiple sclerosis, and parkinsonism (data not shown) also approximated those of the BC Administrative Data Project [1][12]. These findings suggest that, for the most part, health administrative data will be a promising source of data for the national surveillance of neurological conditions.Footnote 36 However, in instances where a condition is defined using the fourth or fifth digits of International Classification of Diseases (ICD) coding, specificity may be lost if hospital or physician claim databases do not capture this level of detail. In most provinces and territories, the physician claim database does not provide the level of digit required for specificity; therefore, a broader category of illness is captured, such as parkinsonism instead of Parkinson's disease, anterior horn cell disease instead of ALS, or myopathy instead of muscular dystrophy.

EMR data are a promising source of information. The EMR Project [6] was successful in producing prevalence estimates for Alzheimer's disease and other dementias, epilepsy, and parkinsonism that were congruent with the estimates obtained from meta-analysis [18]. These findings suggest that the EMRs of family physicians are another potential source of readily accessible epidemiological data on neurological conditions.

Survey data provide reliable prevalence estimates for certain neurological conditions. The CCHS 2010–2011 Project [3] produced prevalence estimates that were comparable to those obtained from meta-analysis for hydrocephalus (infants and children) and Parkinson's disease [18]. For Alzheimer's disease and other dementias, brain tumour, cerebral palsy, dystonia, epilepsy, Huntington's disease, multiple sclerosis, spina bifida, and Tourette syndrome, prevalence estimates were outside the confidence intervals of the pooled estimates obtained through meta-analysis, but remained within the ranges presented by the individual studies included in the meta-analysis (Table 3-1, above). Of note, the prevalence estimate for Alzheimer's disease and other dementias that was derived from the CCHS (2010–2011) was much lower than the estimate obtained from meta-analysis. This implies that self-reported survey data for Canadians living in the community may not be reliable for certain rare or debilitating neurological conditions, regardless of whether proxy responses are included.Footnote 37

Incidence data can be obtained from administrative data. Estimates for newly diagnosed cases, as opposed to existing cases, of selected neurological conditions were provided by the BC Administrative Data Project [1].Footnote 38 For Alzheimer's disease and other dementias, ALS, malignant brain tumours, Huntington's disease, parkinsonism (when compared by age group), and spinal cord injury (when pre-hospital mortality was excluded), the 95% confidence intervals for British Columbia data estimates overlapped with those of the meta-analysis [18]. For epilepsy, hydrocephalus (in infants under one year of age), and multiple sclerosis, estimates from British Columbia were within the ranges of the component studies of the meta-analysis. The CCDSS is currently being expanded to include Alzheimer's disease and other dementias, epilepsy, multiple sclerosis, parkinsonism, and stroke to allow for the ongoing collection of incidence data for these conditions at the national level [2].

Data collected in long-term care facilities show a high prevalence of neurological conditions in these populations. Certain populations can be hard to reach using existing data sources. Most national surveys currently exclude populations living in facilities. While EMR and administrative data may count these populations to some degree, they may not be able to identify them as living in long-term care facilities. The Survey of Neurological Conditions in Institutions in Canada (SNCIC) 2011–2012 Project [17], which employed a mail-in questionnaire to Canadian long-term care facilities, was considered successful with a response rate of 63.5%.

Although it was no surprise that neurological conditions were more prevalent among those in long-term care facilities and in home care programs than among those living in the community at large, the actual figures remained striking. According to results from the interRAI Project [8] (in jurisdictions where data were available), more than half of individuals in formal home care programs (Ontario) or long-term care facilities (Ontario and several other provinces and territories) had at least one neurological condition. The SNCIC 2011–2012 Project [17] also estimated that 64.8% of residents in long-term care facilities in Canada had at least one of the neurological conditions targeted by the survey. The majority (69.3%) of diagnoses reported by administrators were for Alzheimer's disease and other dementias (Table 3-2).Footnote 39

3.2 The distribution of neurological conditions and their comorbidities can differ by age and sex

Data from the CCHS 2010–2011 Project [3] confirmed that multiple sclerosis and migraine affected more women than men, while Tourette syndrome, Parkinson's disease, and brain or spinal cord injury occurred more frequently among men. These data also showed that the overall prevalence of the selected neurological conditions increased with age, peaking at age 80 years and older. This peak was driven mainly by Alzheimer's disease and other dementias, stroke, and Parkinson's disease – neurological conditions that are more prevalent in older age groups. Certain neurological conditions primarily affected younger and middle-age adults, such as multiple sclerosis or traumatic brain injury, while some tended to present in childhood (e.g. cerebral palsy, spina bifida, and hydrocephalus). Moreover, the prevalence of neurological conditions typically present at birth may be affected by the gestational age of the infant. For instance, the Systematic Reviews Project [18] noted that the prevalence of cerebral palsy per 100,000 live births was 11,180 for pre-term infants, compared to a prevalence of 211 when infants of any gestational age were considered.

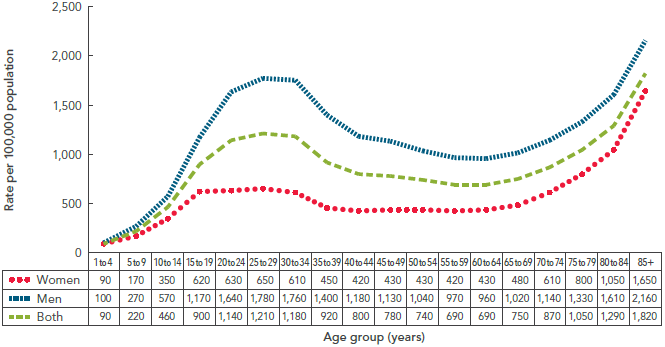

The burden of certain neurological conditions varies by sex and over the life course. Prevalence data from the BC Administrative Data Project [1] depicted clear age and sex patterns:

- Alzheimer's disease and other dementias: Figure 3-1 illustrates how the rates of Alzheimer's disease and other dementias increased similarly in men and women until 80 years of age (approximately doubling every five years after age 70), when the increase became greater in women.

- Parkinsonism: Parkinsonism, which mainly includes Parkinson's disease, was rare under the age of 45 years, but steadily increased thereafter, affecting more men than women (Figure 3-2).

- Multiple sclerosis: The prevalence of multiple sclerosis was higher among women than men for all age groups, but peaked at age 55 to 59 years for both sexes (Figure 3-3).

- Traumatic brain injury: The prevalence of traumatic brain injuries peaked at age 25 to 29 years and declined until age 65 to 69 years, when it started to rise again (Figure 3-4). Regardless of age group, traumatic brain injuries were higher among men than women.

- Spinal cord injury: Finally, for spinal cord injuries, the data showed that regardless of age group, the prevalence was generally higher among men than women (Figure 3-5).

The unequal distribution of the burden of neurological conditions between sexes and across age groups reinforced the need to consider prevalence and incidence patterns when planning for health services and programs.

NOTES:

The 95% confidence interval shows an estimated range of values which is likely to include the true prevalence 19 times out of 20.

BC - British Columbia.

SOURCE: Population Health Surveillance and Epidemiology, British Columbia Ministry of Health (March 2014).

Text Equivalent - Figure 3-1

The line graph shows the prevalence of Alzheimer's disease and other dementias by sex and age group. On the graph, the horizontal axis shows five age groups (65 to 69, 70 to 74, 75 to 79, 80 to 84, and 85+). The vertical axis shows the rate per 100,000 population. A data table showing the rates for women, men, and both is also included below the horizontal axis.

Alzheimer's disease and other dementias increased exponentially with age. For both sexes combined, the rate climbed from 915.7 per 100,000 population in those age 65 to 69 years to 24,699.9 per 100,000 population in those age 85+ years. The rate was higher for men in the 65 to 69 and 70 to 74 year age groups, but was higher for women in the other age groups.

BC stands for British Columbia. Data were based on 2009/10 health administrative data provided by the BC Ministry of Health in the BC Administrative Data Project.

The table lists the rates of Alzheimer's disease and other dementias per 100,000 population for each age group under study:

| Crude prevalence rate/100,000 population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Both | Men | Women |

| 65 to 69 | 916 | 989 | 844 |

| 70 to 74 | 2,747 | 2,801 | 2,696 |

| 75 to 79 | 6,499 | 6,312 | 6,675 |

| 80 to 84 | 12,843 | 12,021 | 13,474 |

| 85+ | 24,700 | 21,101 | 26,633 |

NOTES:

The 95% confidence interval shows an estimated range of values which is likely to include the true prevalence 19 times out of 20.

BC * - British Columbia.

Parkinsonism includes Parkinson's disease.

SOURCE: Population Health Surveillance and Epidemiology, British Columbia Ministry of Health (March 2014).

Text Equivalent - Figure 3-2

The line graph shows the prevalence of parkinsonism, which includes Parkinson's disease, by sex and age group. On the graph, the horizontal axis shows ten age groups (40 to 44, 45 to 49, 50 to 54, 55 to 59, 60 to 64, 65 to 69, 70 to 74, 75 to 79, 80 to 84, and 85+). The vertical axis shows the rate per 100,000 population. A data table showing the rates for women, men, and both is also included below the horizontal axis.

At about 55 to 59 years of age, the rate of parkinsonism increased markedly, from 127.0 per 100,000 population for both sexes to 1996.3 per 100,000 population for both sexes in the 85+ year age group. Parkinsonism was always higher in men than in women.

BC stands for British Columbia. Data were based on 2009/10 health administrative data provided by the BC Ministry of Health in the BC Administrative Data Project.

The table lists the rates of parkinsonism per 100,000 population for each age group under study:

| Crude prevalence rate/100,000 population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Both | Men | Women |

| 40 to 44 | 23 | 27 | 18 |

| 45 to 49 | 41 | 46 | 36 |

| 50 to 54 | 66 | 83 | 49 |

| 55 to 59 | 127 | 161 | 94 |

| 60 to 64 | 269 | 327 | 212 |

| 65 to 69 | 478 | 575 | 383 |

| 70 to 74 | 834 | 1,036 | 641 |

| 75 to 79 | 1,346 | 1,653 | 1,067 |

| 80 to 84 | 1,863 | 2,365 | 1,484 |

| 85+ | 1,996 | 2,623 | 1,679 |

NOTES:

Data were rounded to the nearest ten.

BC

British Columbia.

SOURCE: Population Health Surveillance and Epidemiology, British Columbia Ministry of Health (September 2011).

Text Equivalent - Figure 3-3

| Crude prevalence rate/100,000 population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Both | Men | Women |

| 15 to 19 | 20 | 10 | 20 |

| 20 to 24 | 30 | 20 | 40 |

| 25 to 29 | 60 | 30 | 100 |

| 30 to 34 | 120 | 60 | 180 |

| 35 to 39 | 190 | 90 | 290 |

| 40 to 44 | 250 | 110 | 390 |

| 45 to 49 | 300 | 150 | 440 |

| 50 to 54 | 340 | 160 | 520 |

| 55 to 59 | 390 | 210 | 560 |

| 60 to 64 | 360 | 200 | 510 |

| 65 to 69 | 300 | 180 | 410 |

| 70 to 74 | 210 | 150 | 260 |

| 75 to 79 | 160 | 100 | 220 |

| 80 to 84 | 120 | 80 | 150 |

| 85+ | 60 | 30 | 80 |

Figure 3-4: Prevalence of traumatic brain injury, by sex and age group, British Columbia, 2009/2010, BC Administrative Data Project [1]

NOTES:

Data were rounded to the nearest ten.

- BC

- British Columbia.

SOURCE: Population Health Surveillance and Epidemiology, British Columbia Ministry of Health (September 2011).

Text Equivalent - Figure 3-4

The line graph shows the prevalence of traumatic brain injury, by sex and age group. On the graph, the horizontal axis shows eighteen age groups (1 to 4, 5 to 9, 10 to 14, 15 to 19, 20 to 24, 25 to 29, 30 to 34, 35 to 39, 40 to 44, 45 to 49, 50 to 54, 55 to 59, 60 to 64, 65 to 69, 70 to 74, 75 to 79, 80 to 84, and 85+). The vertical axis shows the rate per 100,000 population. A data table showing the rates for women, men, and both is also included below the horizontal axis.

The prevalence of traumatic brain injury showed an interesting trend by age group. The rate of traumatic brain injury was high in the teenage and young adult age groups of 10 to 14, 15 to 19, 20 to 24, 25 to 29, and 30 to 34. The rate then decreased and remained relatively stable until it increased again in the older age groups of 80 to 84 and 85+ years. For all ages, the rate of traumatic brain injury was higher in men than in women.

BC stands for British Columbia. Data were rounded to the nearest ten. Data were based on 2009/10 health administrative data provided by the BC Ministry of Health in the BC Administrative Data Project.

The table lists the rates of traumatic brain injury per 100,000 population for each age group under study:

| Crude prevalence rate/100,000 population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Both | Men | Women |

| 1 to 4 | 90 | 100 | 90 |

| 5 to 9 | 220 | 270 | 170 |

| 10 to 14 | 460 | 570 | 350 |

| 15 to 19 | 900 | 1,170 | 620 |

| 20 to 24 | 1,140 | 1,640 | 630 |

| 25 to 29 | 1,210 | 1,780 | 650 |

| 30 to 34 | 1,180 | 1,760 | 610 |

| 35 to 39 | 920 | 1,400 | 450 |

| 40 to 44 | 800 | 1,180 | 420 |

| 45 to 49 | 780 | 1,130 | 430 |

| 50 to 54 | 740 | 1,040 | 430 |

| 55 to 59 | 690 | 970 | 420 |

| 60 to 64 | 690 | 960 | 430 |

| 65 to 69 | 750 | 1,020 | 480 |

| 70 to 74 | 870 | 1,140 | 610 |

| 75 to 79 | 1,050 | 1,330 | 800 |

| 80 to 84 | 1,290 | 1,610 | 1,050 |

| 85+ | 1,820 | 2,160 | 1,650 |

Figure 3-5: Prevalence of traumatic spinal cord injury, by sex and age group, British Columbia, 2009/2010, BC Administrative Data Project [1]

NOTES:

- BC

- British Columbia.

SOURCE: Population Health Surveillance and Epidemiology, British Columbia Ministry of Health (September 2011).

Text Equivalent - Figure 3-5

The line graph shows the prevalence of traumatic spinal cord injury, by sex and age group. On the graph, the horizontal axis shows eighteen age groups (1 to 4, 5 to 9, 10 to 14, 15 to 19, 20 to 24, 25 to 29, 30 to 34, 35 to 39, 40 to 44, 45 to 49, 50 to 54, 55 to 59, 60 to 64, 65 to 69, 70 to 74, 75 to 79, 80 to 84, and 85+). The vertical axis shows the rate per 100,000 population. A data table showing the rates for women, men, and both is also included below the horizontal axis.

The prevalence of spinal cord injury jumped from 6 per 100,000 population in the 10 to 14 year age group to 94 per 100,000 population in the 35 to 39 year age group (for both sexes). The rate of spinal cord injury remained high in the adult age groups, and then decreased in the oldest age group of 85+ years. After the age group of 15 to 19 years and before age 80, the rate of spinal cord injury was at least twice as high in men compared to women.

BC stands for British Columbia. Data were based on 2009/10 health administrative data provided by the BC Ministry of Health in the BC Administrative Data Project.

The table lists the rates of spinal cord injury per 100,000 population for each age group under study:

| Crude prevalence rate/100,000 population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | Both | Men | Women |

| 1 to 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 5 to 9 | 3 | 3 | 4 |

| 10 to 14 | 6 | 7 | 6 |

| 15 to 19 | 18 | 26 | 10 |

| 20 to 24 | 51 | 75 | 26 |

| 25 to 29 | 65 | 95 | 36 |

| 30 to 34 | 89 | 133 | 46 |

| 35 to 39 | 94 | 149 | 41 |

| 40 to 44 | 93 | 142 | 45 |

| 45 to 49 | 89 | 140 | 39 |

| 50 to 54 | 97 | 143 | 51 |

| 55 to 59 | 82 | 132 | 32 |

| 60 to 64 | 78 | 124 | 33 |

| 65 to 69 | 83 | 132 | 36 |

| 70 to 74 | 84 | 130 | 41 |

| 75 to 79 | 94 | 142 | 50 |

| 80 to 84 | 93 | 116 | 75 |

| 85+ | 73 | 88 | 65 |

The age at onset of symptoms and diagnosis differ by neurological condition. The age at onset of symptoms and age at diagnosis differed by neurological condition (Table 3-3) [16]. However, based on survey data, differences were not statistically significant by sex except for the age at diagnosis for Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias.Footnote 40 A better analysis of sex differences in the age of onset of various neurological conditions could be addressed with a longitudinal cohort analysis or through the use of administrative data.

| Condition | Men | Women | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at symptom onset | Age at diagnosis | Age at symptom onset | Age at diagnosis | |||||

| Mean | (95% confidence interval) | Mean | (95% confidence interval) | Mean | (95% confidence interval) | Mean | (95% confidence interval) | |

| Alzheimer's disease and other dementias | 70.2 | (68.1-72.3) | 72.2 | (70.1-74.2) | 73.6 | (71.6-75.5) | 75.8 | (74.4-77.2) |

| ALS | Table 3-3 Footnote F | Table 3-3 Footnote F | Table 3-3 Footnote F | Table 3-3 Footnote F | Table 3-3 Footnote F | Table 3-3 Footnote F | Table 3-3 Footnote F | Table 3-3 Footnote F |

| Brain injury (traumatic) | Table 3-3 Footnote N/A | Table 3-3 Footnote N/A | 29.3 | (25.5-33.1) | Table 3-3 Footnote N/A | Table 3-3 Footnote N/A | 31.7 | (26.7-36.6) |

| Brain tumour | 35.5 | (29.9-41.1) | 37.2 | (31.4-43.0) | 37.8 | (32.0-43.6) | 40.0 | (34.6-45.7) |

| Cerebral palsy | Table 3-3 Footnote F | Table 3-3 Footnote F | Table 3-3 Footnote F | Table 3-3 Footnote F | Table 3-3 Footnote F | Table 3-3 Footnote F | 2.1Table 3-3 Footnote E | (0.8-3.4) |

| Dystonia | 31.0Table 3-3 Footnote E | (20.4-41.6) | 34.0Table 3-3 Footnote E | (22.2-45.8) | 33.8 | (23.4-44.2) | 42.2 | (30.3-54.0) |

| Epilepsy | 21.3 | (18.1-24.5) | 21.8 | (18.6-25.0) | 19.5 | (17.0-22.1) | 20.7 | (18.0-23.3) |

| Huntington's disease | Table 3-3 Footnote F | Table 3-3 Footnote F | Table 3-3 Footnote F | Table 3-3 Footnote F | Table 3-3 Footnote F | Table 3-3 Footnote F | Table 3-3 Footnote F | Table 3-3 Footnote F |

| Hydrocephalus | Table 3-3 Footnote F | Table 3-3 Footnote F | Table 3-3 Footnote F | Table 3-3 Footnote F | 19.3Table 3-3 Footnote E | (10.0-28.7) | 20.4Table 3-3 Footnote E | (12.1-28.7) |

| Migraine | 24.2 | (20.6-27.8) | 26.6 | (23.3-29.8) | 22.8 | (21.3-24.3) | 26.4 | (24.9-28.0) |

| Multiple sclerosis | 31.9 | (29.2-34.5) | 34.8 | (31.9-37.6) | 32.3 | (30.3-34.4) | 37.8 | (35.5-40.2) |

| Muscular dystrophy | 22.6 | (16.6-28.6) | 24.9 | (19.0-30.8) | 25.5Table 3-3 Footnote E | (14.6-36.5) | 28.1Table 3-3 Footnote E | (16.7-39.5) |

| Parkinson's disease | 63.2 | (60.0-66.3) | 64.2 | (61.0-67.4) | 65.1 | (61.7-68.5) | 66.9 | (64.0-69.8) |

| Spina bifida | Table 3-3 Footnote N/A | Table 3-3 Footnote N/A | Table 3-3 Footnote N/A | Table 3-3 Footnote N/A | Table 3-3 Footnote N/A | Table 3-3 Footnote N/A | Table 3-3 Footnote N/A | Table 3-3 Footnote N/A |

| Spinal cord injury (traumatic) | Table 3-3 Footnote N/A | Table 3-3 Footnote N/A | 34.7 | (32.5-37.0) | Table 3-3 Footnote N/A | Table 3-3 Footnote N/A | 38.3 | (34.4-42.3) |

| Spinal cord tumour | 49.5 | (43.9-55.1) | 48.0 | (42.0-53.9) | 33.9Table 3-3 Footnote E | (17.7-50.2) | 36.3Table 3-3 Footnote E | (20.6-51.9) |

| Stroke | 56.7 | (53.2-60.2) | Table 3-3 Footnote N/A | Table 3-3 Footnote N/A | 54.8 | (51.0-58.6) | Table 3-3 Footnote N/A | Table 3-3 Footnote N/A |

| Tourette syndrome | 8.2 | (6.5-9.9) | 13.1 | (9.6-16.5) | 10.8Table 3-3 Footnote E | (6.4-15.2) | 11.6Table 3-3 Footnote E | (5.9-17.2) |

NOTES:

SOURCE: 2011–2012 SLNCC data (Statistics Canada). |

||||||||

There are common comorbidities associated with neurological conditions. Men and women differed in their experiences of the physical and social aspects of neurological conditions. Chronic conditions such as neurological conditions may impact men and women at different stages in life, affecting their professional or familial roles. Because the onset of many of these neurological conditions occurs in later life, Canadians may be faced with various comorbidities, and women, who tend to live longer than men, may face additional burdens.

Certain chronic conditions, such as arthritis and high blood pressure, were common comorbidities for the overall population with a neurological condition (excluding migraine) (Table 3-4)[3].Footnote 41 The prevalence of asthma, arthritis, and bowel disease was higher among women than men, while heart disease was higher among men than women. The BC Administrative Data Project [1] also listed the eight most common ‘other diagnoses’ throughout 2005/2006 to 2009/2010 that were associated with each of the 13 neurological conditions addressed in this project, but these associations were a mix of causes and complications related to neurological conditions.

| Condition | Men | Women | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prevalence (%) | (95% confidence interval) | Prevalence (%) | (95% confidence interval) | |

| AsthmaTable 3-4 Footnote * | 8.2 | (6.5-9.9) | 13.6 | (11.4-15.8) |

| ArthritisTable 3-4 Footnote *Table 3-4 Footnote † | 33.0 | (29.7-36.4) | 42.4 | (38.9-46.0) |

| High blood pressure | 35.7 | (32.8-38.6) | 38.6 | (34.9-42.3) |

| COPDTable 3-4 Footnote ‡ | 10.4 | (7.9-12.8) | 10.2 | (8.0-12.5) |

| Diabetes | 15.2 | (12.6-17.7) | 12.0 | (10.0-14.1) |

| Heart diseaseTable 3-4 Footnote * | 20.8 | (18.0-23.5) | 13.6 | (11.6-15.7) |

| Cancer | 6.4 | (5.0-7.8) | 5.2 | (3.7-6.7) |

| Stomach/intestinal ulcer | 7.0 | (5.1-8.9) | 6.9 | (5.4-8.4) |

| Bowel disorderTable 3-4 Footnote * | 8.0 | (6.0-9.9) | 12.9 | (10.8-15.1) |

| Mood disorder | 17.2 | (14.6-19.8) | 20.5 | (17.7-23.3) |

| Depression | 13.2 | (9.1-17.4) | 17.2 | (12.8-21.6) |

| Anxiety disorder | 13.2 | (11.1-15.2) | 16.3 | (13.6-19.0) |

NOTES:

SOURCE: 2010–2011 CCHS data (Statistics Canada). |

||||

3.3 Building capacity for the surveillance of neurological conditions is well underway

One of the goals of the Study was to provide evidence that could inform the development of a surveillance system for neurological conditions in Canada. Progress towards this goal was advanced through four interdependent approaches: systematic reviews and meta-analyses [18], new developments at the Agency to add neurological conditions to the CCDSS [2], the estimates of prevalence and incidence based on different data sources by the projects and surveys of the Study [1][3][6][10][12][17], and the development of guidelines and toolkit for the creation and management of registries [4][15]. In general, none of the data sources examined in the Study was able to produce reliable prevalence estimates for certain targeted neurological conditions, specifically, those that were less prevalent. There were also varying levels of concordance among prevalence estimates for certain conditions, in part because of non-uniform case definitions applied by the different projects or because their coverage was limited to certain jurisdictions.

There is a real opportunity to extend the chronic disease surveillance system, and this report has highlighted several promising areas for further investigation.

~ Federal public servant

Systematic reviews of the literature provide evidence for data coding and sources. To determine the best sources of ascertainment (identification of cases) for 15 neurological conditions, the Systematic Reviews Project [18] identified 30 studies that validated ICD coding of case definitions in health administrative data. The project team also evaluated the sources of ascertainment from over 1,200 studies for prevalence and incidence of neurological conditions and, in consultation with 50 experts, identified the most frequently used sources of data for each condition. They also prepared an inventory of neurological registries.

The results of this investigation supported the development of surveillance for some neurological conditions. Findings from this project demonstrated that the accuracy of ICD coding had been validated for Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias, motor neuron disease,Footnote 42 epilepsy, multiple sclerosis, Parkinson's disease, spinal cord injury, and traumatic brain injury, but not for specific brain tumours, cerebral palsy, dystonia, Huntington's disease, hydrocephalus, muscular dystrophy, spina bifida, or Tourette syndrome.Footnote 43 The project team also concluded that the following sources of ascertainment were the most appropriate for the surveillance of certain neurological conditions:

- Multiple sources: Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias, ALS, cerebral palsy, Huntington's disease, hydrocephalus, multiple sclerosis, muscular dystrophy, Parkinson's disease, and traumatic brain injury.

- Registries: Brain tumours, cerebral palsy, spinal cord injury, and rare disorders.

- Administrative data or EMRs: Epilepsy.

- Population-based random sampling, door-to-door surveys,Footnote 44 or school-based studies: Dystonia and Tourette syndrome.

- Specific surveillance programs: Congenital anomaly surveillance programs for spina bifida.

The addition of neurological conditions to the CCDSS is progressing. The CCDSS is a collaborative network of provincial and territorial surveillance systems led by the Agency to collect data on chronic conditions (such as diabetes or hypertension). In conjunction with some of the other projects of the Study [1][10][12][18], the CCDSS Neurological Conditions Working Group conducted development work to add four neurological conditions to the CCDSS (Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias, epilepsy, multiple sclerosis, and parkinsonism) [2]. The inclusion of stroke in the CCDSS has been ongoing and is led by the CCDSS Stroke Working Group.

Studies to validate algorithms for these five conditions were performed by the ON Administrative Data Project [12]. This represented a major step toward the development of the CCDSS for the pan-Canadian surveillance of neurological conditions, as it allowed for the identification of the best performing algorithms. In 2013/2014, these five neurological conditions were included in the CCDSS national pilot, a process in which all provinces and territories test the case definitions in their jurisdiction. Careful analysis of national pilot data will ensure that the selected case definitions consistently apply across all Canadian provinces and territories. With the formal inclusion of these conditions in the CCDSS in the near future, this component of the Study will continue on an ongoing basis as part of the Agency’s national public health surveillance mandate.

The Canadian Primary Care Sentinel Surveillance Network (CPCSSN) has been expanded to include neurological conditions. The EMR Project [6] used the existing CPCSSN platform to develop case definitions for Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias, epilepsy, and parkinsonism. Findings from this project suggest that EMRs could be used for regular surveillance of these conditions in community-based primary care when ascertainment algorithms are appropriately validated.

Creating a combined data registry to highlight the commonalities between and among neurological conditions – could this be linked or combined with chronic disease surveillance?

~ Volunteer, researcher

Guidelines have been created for the development and maintenance of registries. For neurological conditions not well suited to surveillance through surveys and/or administrative data, the creation of a registry may be another approach. Disease or patient registries are collections of data related to patients with a specific diagnosis or condition. The Registry Guidelines Project [15] carried out extensive literature reviews, held three structured focus group meetings and two consensus conferences, and used a modified Delphi consultation process to produce comprehensive guidelines for the development, implementation, and maintenance of registries of neurological conditions in Canada. These guidelines have been published,Footnote 45 and an implementation toolkit will assist in the planning of future registries for neurological conditions. This project delineated the key elements of:

- Good registry design: Participant informed consent, transparency, an advisory council, clear data ownership, appropriate data security, data release procedures, multi-modal patient recruitment, patient follow-up, planned data linkage, standard operating procedures, a data management plan, and appropriate data collection.

- A high quality registry: A quality management plan; standardized methodologies to address data collection and source inconsistencies; the use of an iterative or pilot-tested data collection method; rigorous, consistent and documented processes for data cleaning and correction; trained personnel; and a defined audit system with initialization triggers.

- A registry with high impact: Advance planning, adequate human and financial resources, regular communication with participants and stakeholders, efficient data collection, and transparent operation.

Although Canadian patients were generally supportive of the concept of disease and patient registries and were willing to participate in such registries, certain considerations emerged from the structured focus groups:

- Before providing their consent to participate in a registry, patients wanted to know certain features of the registry: Its purpose; its capacity to facilitate ethical research with meaningful results; that it is well managed and sustainable; that participation will not be onerous; and that they may withdraw at any time.

- Patients also had difficulty understanding the need to share other information such as: Personal information including age, occupation, income, provincial health number, and marital status. They also did not wish to provide their Social Insurance Number to a registry, even if they knew this was the only national individual identifier.

The Cerebral Palsy Registry Project [4] also produced information about the key challenges involved in expanding an existing registry. Although the experiences of this project team were specific to cerebral palsy, lessons learned could be helpful in the development of registries for other neurological conditions.

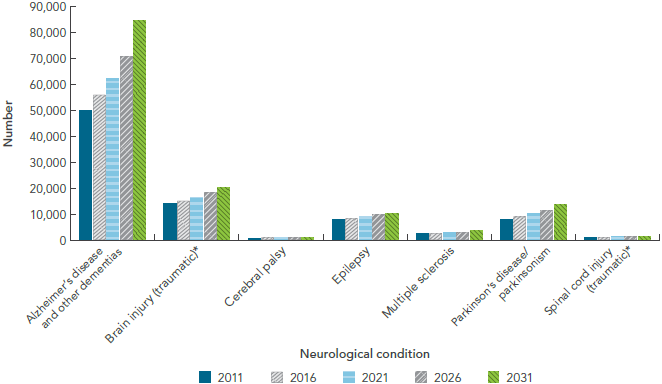

3.4 Looking ahead: 2011 to 2031

Results from the Microsimulation Project [10], which are based on status quo assumptions,Footnote 46 project that between 2011 and 2031:

- The number of Canadians living with Alzheimer's disease and other dementias and Parkinson's disease/parkinsonism (based on prevalence numbers) will almost double (Table 3-5).

| Condition | Projection year | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2011 | 2016 | 2021 | 2026 | 2031 | |

| Number of prevalent casesTable 3-5 Footnote * (rate per 100,000 population in projection year)Table 3-5 Footnote * |

|||||

| Alzheimer's disease and other dementias | 340,200 | 395,000 | 461,700 | 554,200 | 674,000 |

| (2,000) | (2,200) | (2,400) | (2,700) | (3,100) | |

| Brain injury (traumatic)Table 3-5 Footnote † | 550,900 | 595,700 | 640,100 | 685,600 | 730,300 |

| (1,600) | (1,700) | (1,700) | (1,800) | (1,800) | |

| Cerebral palsy | 75,200 | 79,800 | 84,300 | 89,300 | 94,200 |

| (200) | (200) | (200) | (200) | (200) | |

| Epilepsy | 321,700 | 345,400 | 368,100 | 392,100 | 415,800 |

| (1,000) | (1,000) | (1,000) | (1,000) | (1,000) | |

| Multiple sclerosis | 98,800 | 108,600 | 117,800 | 126,200 | 133,600 |

| (400) | (400) | (400) | (400) | (400) | |

| Parkinson's disease/parkinsonism | 84,700 | 99,000 | 116,800 | 138,800 | 163,700 |

| (500) | (500) | (600) | (700) | (700) | |

| Spinal cord injury (traumatic)Table 3-5 Footnote † | 35,000 | 38,400 | 41,800 | 45,200 | 48,100 |

| (100) | (100) | (100) | (100) | (100) | |

NOTES:

SOURCE: POHEM–Neurological (Statistics Canada and Public Health Agency of Canada). |

|||||

- In the population age 65 years and older, there will be at least twice as many, if not more, Canadians living with each of the seven modelled neurological conditions (based on prevalence numbers) (Table 3-6).

| Condition | Projection year | |

|---|---|---|

| 2011 | 2031 | |

| Number of prevalent casesTable 3-6 Footnote * | ||

| Alzheimer's disease and other dementias | 310,000 | 639,700 |

| Brain injury (traumatic)Table 3-6 Footnote † | 119,100 | 258,700 |

| Cerebral palsy | 6,000 | 15,000 |

| Epilepsy | 56,700 | 123,800 |

| Multiple sclerosis | 28,100 | 58,000 |

| Parkinson's disease/parkinsonism | 71,500 | 148,800 |

| Spinal cord injury (traumatic)Table 3-6 Footnote † | 8,600 | 19,300 |

NOTES:

SOURCE: POHEM–Neurological (Statistics Canada and Public Health Agency of Canada). |

||

- The number of Canadians newly diagnosed (incidence count) with cerebral palsy, epilepsy, multiple sclerosis, and spinal cord injury will grow in line with the growth of the population, so that incidence rates in 2031 will remain close to those seen in 2011 (Table 3-7). For conditions whose risk increases markedly with age, the incidence will increase beyond the rate of population growth. In particular, for Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias and Parkinson’s disease/parkinsonism, the incidence rate will increase by almost 50%.

- For traumatic brain injury, the number of hospitalizations is expected to increase by 28% over the next 20 years unless better prevention strategies are implemented.

| Condition | Projection year | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2011 | 2016 | 2021 | 2026 | 2031 | |

| Number of incident casesTable 3-7 Footnote * (rate per 100,000 population in projection year)Table 3-7 Footnote † |

|||||

| Alzheimer's disease and other dementias | 59,600 | 66,700 | 77,500 | 93,200 | 110,700 |

| (360) | (370) | (410) | (460) | (530) | |

| Brain injury (traumatic)Table 3-7 Footnote ‡ | 20,200 | 21,000 | 22,700 | 24,800 | 25,900 |

| (60) | (60) | (60) | (70) | (70) | |

| Cerebral palsy | 1,800 | 1,900 | 2,000 | 2,000 | 2,200 |

| (20) | (20) | (20) | (20) | (20) | |

| Epilepsy | 18,300 | 19,000 | 20,400 | 21,600 | 22,400 |

| (50) | (50) | (60) | (60) | (60) | |

| Multiple sclerosis | 4,100 | 4,400 | 4,300 | 4,300 | 4,800 |

| (15) | (16) | (15) | (14) | (15) | |

| Parkinson's disease/parkinsonism | 10,400 | 11,900 | 14,000 | 16,000 | 18,600 |

| (60) | (60) | (70) | (80) | (90) | |

| Spinal cord injury (traumatic)Table 3-7 Footnote ‡ | 1,400 | 1,600 | 1,700 | 1,600 | 1,700 |

| (4) | (5) | (5) | (4) | (5) | |

NOTES:

SOURCE: POHEM–Neurological (Statistics Canada and Public Health Agency of Canada). |

|||||

- The number of deaths among Canadians with a neurological condition will increase, with the greatest impact seen in those living with Parkinson’s disease/parkinsonism, where a 74% increase in the number of deaths is projected over time. The total number of deaths for those living with Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias, which is already the highest of the modelled conditions in 2011, will increase by a further 70% by 2031 (Figure 3-6).

Figure 3-6: Projected number of deaths, by select neurological condition, Canada, 2011, 2016, 2021, 2026, and 2031, Microsimulation Project [10]

NOTES:

* Traumatic brain and spinal cord injuries were based on hospitalized cases, and excluded injuries that did not present to hospital.

SOURCE: POHEM–Neurological (Statistics Canada and Public Health Agency of Canada).

Text Equivalent - Figure 3-6

The bar graph is a complex display showing the projected number of deaths over time in Canadians living with select neurological conditions. On the graph, the horizontal axis has two components: first, there are seven neurological conditions listed (Alzheimer's disease and other dementias, brain injury, cerebral palsy, epilepsy, multiple sclerosis, Parkinson's disease/parkinsonism, and spinal cord injury). Second, for each neurological condition, it shows five time periods (2011, 2016, 2021, 2026, and 2031). The vertical axis lists the total number of deaths.

For Alzheimer's disease and other dementias, brain injury, epilepsy, multiple sclerosis, and Parkinson's disease/parkinsonism, the projected number of Canadians dying increased in a stepwise fashion over time. The projected number of deaths over time remained stable for cerebral palsy and spinal cord injury. The projected number of deaths was highest for those living with Alzheimer's disease and other dementias, and was comparatively low for cerebral palsy and spinal cord injury.

Data were from the POHEM-Neurological modelling platform from Statistics Canada and Public Health Agency of Canada. Traumatic brain and spinal cord injuries were based on hospitalized cases, and excluded injuries that did not present to hospital.

The table lists the number of deaths in Canadians living with each of the neurological conditions under study:

| Neurological condition | 2011 | 2016 | 2021 | 2026 | 2031 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alzheimer's disease and other dementias | 49,671 | 55,885 | 62,045 | 70,673 | 84,600 |

| Brain injury (traumatic; hospitalized) | 14,126 | 15,047 | 16,415 | 18,195 | 20,066 |

| Cerebral palsy | 737 | 921 | 965 | 986 | 1,001 |

| Epilepsy | 7,707 | 8,225 | 8,993 | 9,790 | 10,111 |

| Multiple sclerosis | 2,458 | 2,662 | 2,750 | 3,024 | 3,449 |

| Parkinson's disease/parkinsonism | 7,963 | 8,972 | 10,007 | 11,373 | 13,818 |

| Spinal cord injury (traumatic; hospitalized) | 1,061 | 1,102 | 1,144 | 1,278 | 1,387 |

3.5 Knowledge gaps

While several projects of this Study generated new findings that hold promise for the further determination of scope of neurological conditions in Canada, it was also demonstrated that for some conditions, different data sources produced incongruent results. This complexity calls for caution and careful consideration when selecting the most appropriate statistics to describe the burden of neurological conditions in Canada.

Regarding the scope of neurological conditions, the Study identified two main categories of gaps – gaps in research and gaps in infrastructure. Research gaps included the lack of data on:

- The identification of certain neurological conditions, such as multiple sclerosis or Parkinson's disease, at their earliest stages (noting that early symptoms are often non-specific, which makes it hard to reach a diagnosis, in addition to a tendency to use coding to describe symptoms rather than the diagnosis itself);

- Less prevalent conditions such as ALS, dystonia, and Huntington's disease, as well as other neurological conditions not targeted by the Study;

- Neurological conditions in populations typically excluded from participation in national population surveys;Footnote 47 and

- The extent of neurological conditions among children (including cerebral palsy, epilepsy, multiple sclerosis, brain injury, and stroke), and the persistence of these conditions into adulthood.

Gaps in infrastructure included the need for:

- Standardization of diagnostic codes (e.g. ICD-10-CA) used in physician billing claims and hospital data in all provinces and territories;

- Standardization of case definitions and algorithms, as well as their periodic review;

- Ongoing consideration and incorporation of newly available data (e.g. pharmaceutical or costing data); and

- Complete data capture and reporting of benign brain tumours in existing provincial and territorial cancer registries.

Findings from the Study were highly valuable in providing researchers and the Agency the tools and evidence to consider when developing national surveillance of neurological conditions in Canada.

3.6 Key themes

In this chapter, various data sources were explored for their utility and suitability in examining the epidemiology of neurological conditions in Canada. It was noted that:

- The Study has produced many new estimates of the prevalence and incidence of neurological conditions in Canada which were not previously available. For many neurological conditions, estimates derived from administrative data, self-report survey, and EMRs conform to estimates based on meta-analyses of international studies. However, primarily for technical reasons, additional studies will be necessary to obtain reliable prevalence estimates for ALS, muscular dystrophy, spinal cord injury, and traumatic brain injury in Canada.

- When the estimates of prevalence and incidence from different sources differ significantly, they need to be interpreted with caution and the differences must be carefully balanced and critically appraised.

- Estimates of prevalence and incidence compiled periodically and systematically from health administrative data can be used to trace the course of neurological conditions over time, as well as across provinces and territories.

- The expansion of the evolving surveillance system for neurological conditions in Canada has been enhanced by the determination of the best sources of epidemiological data for certain neurological conditions and by the validation of algorithms for use with administrative data.

- Detailed guidelines and a toolkit for the development and maintenance of registries that can contribute to the surveillance of neurological conditions are now available.

- Neurological conditions are the primary diagnoses of more than half of Canadians in continuing care (home care programs and long-term care facilities). Therefore, to determine the prevalence of severely debilitating neurological conditions in Canada, data from both the community and long-term care facilities are necessary to obtain a more comprehensive picture.

Microsimulation modelling of seven neurological conditions projects that by 2031:

- Traumatic brain injury, Alzheimer's disease and other dementias, and epilepsy will continue to be the most prevalent of the modelled conditions.

- In a population age 65 years and older, the number of Canadians living with each of the modelled neurological conditions will more than double.

- The number of new cases of cerebral palsy, epilepsy, multiple sclerosis, and spinal cord injury will rise with the growth of the population.

- The number of Canadians receiving a new diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease and other dementias or Parkinson's disease/parkinsonism will close to double.

- The number of Canadians hospitalized with a brain injury will increase by 28%.