Expert Panel Report

Building Common Ground: A New Vision for Impact Assessment in Canada

Download the alternative format

(PDF format, 5.2 MB, 124 pages)

Table of Contents

- Message from the Panel

- Executive Summary

- Introduction: Our Mandate and Our Journey

- Section 1 – Outlining the Vision

- Section 2 – Developing the Vision

- Section 3 – Implementing the Vision

- Section 4 – The Expert Panel’s Review Process and What We Heard

- Annex 1 – Expert Panel Terms of Reference

- Annex 2 – Biographies of Expert Panel Members

- Annex 3 – Discussion Paper: “Suggested Themes for Discussion”

Message from the Panel

We have been honoured to serve on the Expert Panel mandated by the Minister of Environment and Climate Change to review federal environmental assessment processes. Enclosed is our Report to the Minister outlining our recommendations to restore the public’s trust and confidence in these processes. From the start, we have each believed that this is an important undertaking without which Canada would be stalled on its journey toward sustainable development. Economic progress, environmental protection and social improvement would all be less than ideal without an assessment process that has the trust of Canadians.

To all who participated in our review, we offer our heartfelt thanks and deep appreciation. Without your selfless effort, we would not have been able to undertake this work. Many of you came before us to share your views and experiences and to suggest solutions to improve assessment processes in Canada. Your enthusiasm and commitment fuelled our own passion and gave us the energy we needed day after day to complete our task. Others spent hours writing submissions that were thought-provoking and valued. We thank you all. You have been a source of inspiration.

We were very impressed by the younger generations of participants who came before us. Coupled with those who asked us to adopt “next generation” environmental assessment, we received a clear message to focus on development that is sustainable for present and future generations. We send them special thanks for their knowledge, passion and commitment, and know that they will lead Canada to a better place.

In developing our Report, we have strived to take all of your recommendations into account in developing our vision for the future. Separate from our Report, we have put together a detailed annotation of your recommendations and identified where in our Report they have been addressed.

We would like to acknowledge the support from Minister McKenna and thank her for the opportunity to contribute to this important initiative. We wish her, her office and her staff success in developing a new federal assessment regime, and we hope that our Report will be helpful in doing so.

To the Multi-Interest Advisory Committee, to the selected experts and to the former project review panel members who gave of their time to help us, we offer our thanks. Your assistance was invaluable.

Finally, to the Secretariat who supported us, we have nothing but praise and admiration. The many hours you all spent working tirelessly to enable us to complete this task was truly awesome. Thank you all very much. We would also like to thank the Canadian Environmental Assessment Agency for their support in establishing the Secretariat and our Panel.

This Report is for those who think there is a better way forward. Take the next steps. Make us all accountable to build a better Canada, more in line with who we are and what we value.

Johanne Gélinas (Chair)

Doug Horswill (Member)

Rod Northey (Member)

Renée Pelletier (Member)

Executive Summary

In her mandate letter from the Prime Minister, the Minister of Environment and Climate Change (the Minister) was directed to immediately review environmental assessment (EA) processes with these objectives: to restore public trust in EA; to introduce new, fair processes; and to get resources to market. On August 15, 2016, the Minister announced the establishment of our four-person Expert Panel (the Panel) to conduct this review.

The Terms of Reference established for the review directed us, the Panel, to engage broadly with Canadians, Indigenous Peoples, provinces and territories, and key stakeholders to develop recommendations to the Minister on how to improve federal EA processes.

Views about federal EA across the various interests ranged from support to all-out opposition. It was clear, however, that current assessment processes under the Canadian Environmental Assessment Act, 2012 (CEAA 2012) are incapable of resolving these disparate points of view.

In general, we did not hear strident opposition to the development of projects, although in a few cases there were those who held that certain projects should not have gone ahead. Rather, we heard that, when communities, proponents and governments work together with mutual respect and understanding in a process that is open, inclusive and trusted, assessment processes can deliver better projects, bring society more benefits than costs and contribute positively to Canada’s sustainable future.

As we drew lessons from what we had heard across the country, we came to the conclusion that we need to improve the way we plan for development in our country. We believe that Canadians deserve better and that it is entirely possible to deliver better. Our Report explains how to achieve this.

In Section 1, Outlining the Vision, we lay the foundation for the recommendations that follow. We outline that, in our view, assessment processes must move beyond the bio-physical environment to encompass all impacts likely to result from a project, both positive and negative. Therefore, what is now “environmental assessment” should become “impact assessment” (IA). Changing the name of the federal process to impact assessment underscores the shift in thinking necessary to enable practitioners and Canadians to understand the substantive changes being proposed in our Report.

We also outline that, as we listened to presenters and read the many submissions presented to us, we came to understand that any new effective assessment process must be governed by four fundamental principles. IA processes must be transparent, inclusive, informed, and meaningful.

In Section 2, Developing the Vision, we outline recommendations about the purpose of IA, the importance of co-operation among jurisdictions, integrating Indigenous considerations into IA processes, enabling meaningful participation and ensuring evidence-based decision-making. Each of these aspects is fundamental to ensuring that federal IA is robust and responds effectively to what we heard across the country.

Impact assessment aims to identify and address potential issues and concerns early in the design of projects, plans and policies. In so doing, it can contribute to the creation of positive relationships among various interest groups, including reconciliation between Indigenous Peoples and non-Indigenous peoples. IA also aims to contribute to the protection of the bio-physical environment and the long-term well-being of Canadians by gathering proper information to inform decision-making. At a project scale, IA should improve project design and ensure appropriate mitigation measures and monitoring programs are implemented. In sum, IA processes should give Canadians confidence that projects, plans and policies have been adequately assessed.

Federal IAs require clear direction on both the purpose and parameters of the process. There are many options on how best to do IA. In considering the future of IA in Canada, it is necessary to begin by answering the following fundamental questions through a consideration of jurisdiction, significance and sustainability, and IA’s role as a planning tool:

- What should require federal IA?

- When should a federal IA for a project, plan, or policy begin?

- What should federal IA look at?

Regarding the purpose of IA, the Panel recommends that:

- federal interest be central in determining whether an IA should be required for a given project, region, plan or policy.

- federal IA should begin with a legislated Planning Phase that, for projects, occurs early in project development before design elements are finalized.

- sustainability be central to IA. The likelihood of consequential impacts on matters of federal interest should determine whether an IA would be required.

- federal IA decide whether a project should proceed based on that project’s contribution to sustainability.

- IA legislation require the use of strategic and regional IAs to guide project IA.

IA creates challenges for Canada’s system of government, with the requirement that a broad range of information be collected and evaluated but with no government having full authority to regulate all impacts. Federal, provincial, territorial, municipal and Indigenous governments may each have responsibility for the conduct of IA, but each level of government can only regulate matters within its jurisdiction.

The principle of “one project, one assessment” is central to implementing IA around the five pillars of sustainability. Grounding federal IA in legal jurisdiction, starting early in planning and focusing on assessing contributions to sustainability make co-operation among jurisdictions essential to ensure Canadians realize the benefits from IA.

Regarding co-operation among jurisdictions, the Panel recommends that:

- co-operation be the primary mechanism for co-ordination where multiple IA processes apply.

- substitution be available on the condition that the highest standard of IA would apply.

Finding ways to enhance Indigenous participation and consultation was identified as a key goal in the Panel’s Terms of Reference, as was reflecting the principles of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), “especially with respect to the manner in which environmental assessment processes can be used to address potential impacts to potential or established Aboriginal or treaty rights.”

The Panel recognizes that there are broader discussions that need to occur between the Government of Canada and Indigenous Peoples with respect to nation-to-nation relationships, overlapping and unresolved claims to Aboriginal rights and title, reconciliation, treaty implementation and the broader implementation of UNDRIP. Many of these discussions will be necessary prerequisites to the full and effective implementation of the recommendations contained in this Report.

Regarding Indigenous considerations, the Panel recommends that:

- Indigenous Peoples be included in decision-making at all stages of IA, in accordance with their own laws and customs.

- IA processes require the assessment of impacts to asserted or established Aboriginal or treaty rights and interests across all components of sustainability.

- any IA authority be designated an agent of the Crown and, through a collaborative process, thus be accountable for the duty to consult and accommodate, the conduct of consultation, and the adequacy of consultation. The fulfilment of this duty must occur under a collaborative framework developed in partnership with impacted Indigenous Groups.

- any IA authority increase its capacity to meaningfully engage with and respect Indigenous Peoples, by improving knowledge of Indigenous Peoples and their rights, history and culture.

- a funding program be developed to provide long-term, ongoing IA capacity development that is responsive to the specific needs and contexts of diverse Indigenous Groups.

- IA-specific funding programs be enhanced to provide adequate support throughout the whole IA process, in a manner that is responsive to the specific needs and contexts of diverse Indigenous Groups.

- IA legislation require that Indigenous knowledge be integrated into all phases of IA, in collaboration with, and with the permission and oversight of, Indigenous Groups.

- IA legislation confirm Indigenous ownership of Indigenous knowledge and include provisions to protect Indigenous knowledge from/against its unauthorized use, disclosure or release.

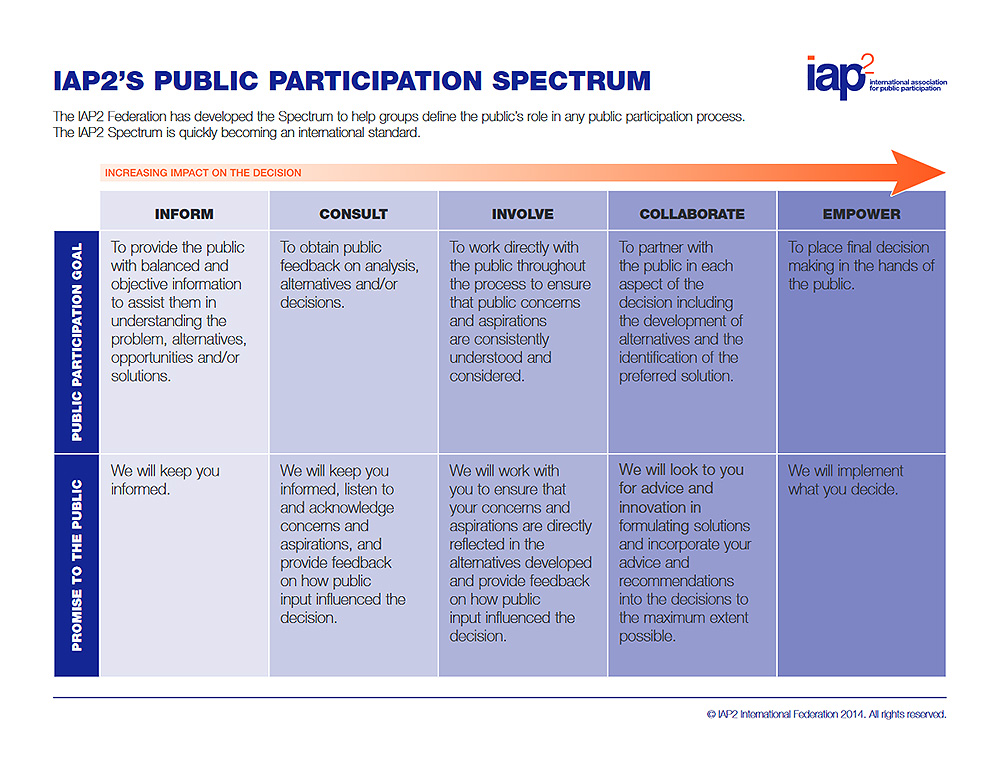

Meaningful public participation is a key element to ensure the legitimacy of IA processes and central to a renewed IA that moves it towards a consensus-building exercise, at the core of which are face-to-face discussions.

IA can build trust in communities by bringing all affected parties to the table; it increases the transparency of the process by facilitating information sharing; it improves the design of initiatives by incorporating public information, expertise, perspective and concerns; and it provides for improved decision-making by ensuring all relevant information is available. It is through public engagement and participation that social license to operate – obtaining broad public support for proposed undertakings – can be built and optimal results of IA can be reached. Further, as a learning process, it builds literacy in IA processes and builds capacity. Lastly, meaningful participation does not finish with the decision and can contribute to oversight of project implementation.

Regarding public participation, the Panel recommends that:

- IA legislation require that IA provide early and ongoing public participation opportunities that are open to all. Results of public participation should have the potential to impact decisions.

- the participant funding program for IA be commensurate with the costs associated with meaningful participation in all phases of IA, including monitoring and follow-up.

- IA legislation require that IA information be easily accessible, and permanently and publicly available.

Science, facts and evidence are critical to a well-functioning IA process. Whether for collecting data, analyzing results or establishing monitoring and follow-up programs, the quality of science contributes to a trusted process and credible outcomes.

Evidence comes in many forms and includes Indigenous knowledge and community knowledge. The sustainability-based IA framework being proposed seeks to integrate all relevant evidence that supports outcomes within the environmental, health, social, cultural and economic pillars.

Regarding evidence-based IA, the Panel recommends that:

- IA legislation require that all phases of IA use and integrate the best available scientific information and methods.

- IA legislation require the development of a central, consolidated and publicly available federal government database to house all baseline and monitoring data collected for IA purposes.

- IA legislation provide any IA authority with power to compel expertise from federal scientists and to retain external scientists to provide technical expertise as required.

- any IA authority have the statutory authority to verify the scientific accuracy of studies across all pillars of sustainability.

- IA integrate the best evidence from science, Indigenous knowledge and community knowledge through a framework determined in collaboration with Indigenous Groups, knowledge holders and scientists.

- IA legislation require that any IA authority lead the development of the Impact Statement.

- IA decisions reference the key supporting evidence they rely upon, including the criteria and trade-offs used to achieve sustainability outcomes.

In Section 3, Implementing the Vision, we explain how our recommended vision can be put into practice. Our recommendations cover the assessment regime and its governance structure. They seek to ensure that the process, the resulting decisions and their implementation are inclusive, transparent and fair. We explain how assessment processes would start earlier and result in better and more-informed decisions. Our recommended approach seeks to build public confidence in the assessment process. We believe that public trust can lead to more efficient and timely reviews. It may also support getting resources to market.

To restore public trust and confidence in assessment processes, any authority given the mandate to conduct federal assessments should be aligned with the Panel’s guiding principles. In developing recommendations for how to govern federal IA, the Panel has identified four areas of focus:

- Striving to remove any perceived notion of bias on the part of responsible authorities;

- Maximizing the benefits of a planning-focused IA;

- Instilling co-operation and consensus as a governance philosophy; and

- Ensuring that IA delivers transparent, evidence-based decisions.

In consideration of these areas, the Panel recommends that:

- a single authority have the mandate to conduct and decide upon IAs on behalf of the federal government.

- the IA authority should be established as a quasi-judicial tribunal empowered to undertake a full range of facilitation and dispute-resolution processes.

Project IA is the cornerstone of the proposed IA regime. We believe that bringing federal assessment into alignment with the four principles guiding our review requires fundamental change. The proposed new process would:

- aim to build consensus and reduce conflict;

- facilitate co-operation with the provinces, territories and Indigenous jurisdictions;

- avoid conflicts of interest and protect against bias;

- mandate early planning and early engagement;

- integrate science, Indigenous knowledge and community knowledge;

- have time limits and cost controls that reflect the specific circumstances of each project, rather than the current “one size fits all” approach; and

- lead to decisions based on the five pillars of sustainability (environment, economy, social, cultural and health).

All told, this process would seek to restore trust by bringing parties together, benefiting communities and advancing the national interest in sustainable development.

Indigenous Peoples in Canada have a particularly important role to play in project IA. The proposed assessment process would seek to engage Indigenous Groups from early project planning through to assessment decisions and follow-up. It would more accurately and holistically assess impacts to Aboriginal and treaty rights and interests and identify appropriate accommodation measures. This IA process should contribute to a meaningful nation-to-nation relationship.

Therefore, regarding project IA, the Panel recommends that:

- IA legislation define a “project” to be a physical activity or undertaking that impacts one or more matters of federal interest.

- IA legislation require project IAs when a project is on a new Project List, a project not on the new List is likely to have a consequential impact, or the IA authority accepts a request.

- all phases of project IA be conducted through a multi-party, in-person engagement process.

- the outcome of the Planning Phase would be a conduct of assessment agreement.

- Based on a prepared project design, the conduct of assessment agreement would finalize the factors for assessment, set out the sustainability framework, identify studies that need to be conducted, address the constitutional duty to consult, outline how the process will integrate procedural and legislative requirements of other jurisdictions, and provide details on IA timing and cost.

- the studies outlined in the conduct of assessment agreement be completed in the Study Phase. The IA authority would lead an assessment team accountable for preparing the Impact Statement, informed by these studies.

- a Decision Phase be established wherein the IA authority would seek Indigenous consent and issue a public decision statement on whether the project contributes positively to the sustainability of Canada’s development.

The Decision Phase completes the “assessment” part of the IA process, while monitoring and follow-up related to conditions, as well as compliance and enforcement, make up the post-IA phase. These post-IA elements are equally important to restore trust in assessment processes and ensure robust oversight, as they ensure the implementation of conditions issued with the decision and verify the accuracy of the assessment predictions and the effectiveness of identified mitigation measures.

Establishing an effective and transparent post-IA phase ensures that project implementation meets the outcomes established through the IA process. A consistent methodology for all monitoring of projects, applied to things such as data collection, would allow for results to be compared for similar project types or activities in a similar region.

Therefore, the Panel recommends that:

- decision statements use outcome-based conditions that set clear and specific standards of performance.

- IA legislation contain a formal process to amend conditions.

- IA legislation ensure sustainability outcomes are met through mandatory monitoring and follow-up programs with minimum standard requirements common to all project IAs.

- Indigenous Groups and local communities be involved in the independent oversight of monitoring and follow-up programs established by the IA authority.

- all monitoring and follow-up data, including raw data, results and any actions taken to address ineffective mitigation, be posted on a public registry.

- IA legislation provide a broad range of tools to enforce IA conditions and suspend or revoke approvals.

- the results of inspections be promptly available to the public. An annual report of compliance with conditions for all projects should be published in a public registry.

- IA legislation authorize the IA authority to carry out compliance and enforcement activities with other jurisdictions, so long as the results of such activities are no less available to the public than the results of activities by the IA authority.

A final consideration of project IA is the need for a well-designed and successful IA process to provide clarity to all parties through predictable requirements and timelines. A one-size-fits-all approach to project IA timelines through legislated timeframes has not met the objective of delivering cost and time certainty to proponents. Nevertheless, these attributes are essential to ensure that projects providing a net benefit to the country are approved and built.

Any new IA regime must recognize the importance of trying to discipline the process to provide timely and cost-effective IA for Canadians.

Therefore, the Panel recommends that:

- the IA authority be required to develop an estimate of the cost and timeline for each phase of the assessment and report regularly on the success in meeting these estimates.

While project-specific assessments have an important role to play to ensure new activities contribute to sustainability, many sustainability questions cannot be properly assessed at the scale of project IA. Enhanced interactions between projects, regions, plans and policies, and the pillars of sustainability are an important purpose of IA. A federal IA regime equipped with this suite of options can apply the best type of assessment to any given activity or decision. Therefore, a tiered approach should be implemented whereby strategic and regional IAs produce the policy and planning foundations for improved and efficient project IAs.

Regional IA will provide clarity on thresholds and objectives on matters of federal interest in a region and will inform and streamline project IA. In addition to being well-equipped to address the sustainability of development in various regions, particularly in relation to cumulative impacts, regional IA can also streamline project IA to the benefit of proponents and communities alike.

Regarding regional IA, the Panel recommends that:

- IA legislation require regional IAs where cumulative impacts may occur or already exist on federal lands or marine areas, or where there are potential consequential cumulative impacts to matters of federal interest.

- IA legislation require the IA authority to develop and maintain a schedule of regions that would require a regional IA and to conduct those regional IAs.

- a regional IA establish thresholds and objectives to be used in project IA and federal decisions.

A new strategic IA model should be put in place to provide guidance on how to implement existing federal policies, plans and programs in a project or regional IA. This approach involves no amendment to the existing Cabinet Directive on the Environmental Assessment of Policy, Plan and Program Proposals and its process for assessing new federal initiatives. Instead, the new model of strategic IA would apply exclusively to the implementation of existing federal plans, programs and policies where these initiatives have consequential implications for project or regional IA.

Regarding strategic IA, the Panel recommends that:

- IA legislation require that the IA authority conduct a strategic IA when a new or existing federal policy, plan or program would have consequential implications for federal project or regional IA.

- strategic IA define how to implement a policy, plan or program in project and regional IA.

IA should play a critical role in supporting Canada’s efforts to address climate change. Current processes and interim principles take into account some aspects of climate change, but there is an urgent national need for clarity and consistency on how to consider climate change in project and regional IA.

Criteria, modelling and methodology must be established to:

- assess a project’s contribution to climate change;

- consider how climate change may impact the future environmental setting of a project; and

- consider a project’s or region’s long-term sustainability and resiliency in a changing environmental setting.

The Panel’s recommended model for strategic IA would prove beneficial in determining a consistent approach for evaluating a project’s contributions to climate change.

Therefore, regarding climate change and IA, the Panel recommends that:

- Canada lead a federal strategic IA or similar co-operative and collaborative mechanism on the Pan-Canadian Framework on Clean Growth and Climate Change to provide direction on how to implement this Framework and related initiatives in future federal project and regional IAs.

In Section 4, The Expert Panel’s Review Process and What We Heard, we summarize our cross-country review process and what we heard from coast to coast to coast. The input we received had a depth and quality that clearly demonstrated how important this issue is to Canadians, and was instrumental to the development of our Report.

These recommendations, taken together, present the Panel’s vision for an impact assessment regime that will protect the physical and biological environment, promote social harmony and facilitate economic development.

Advancing Canada’s economy is about generating job-supporting economic growth across all sectors. Infrastructure projects and the resource industries are among those most affected by the assessment processes. We believe that the process we propose, which is guided by principles designed to restore public trust and confidence, will facilitate the investment in these sectors that is necessary to grow Canada’s economy in ways that will contribute positively to a sustainable future.

Leadership from the federal government toward improving the project assessment process across Canada would benefit every Canadian. We believe that this review provides the opportunity to raise the bar on assessment processes so that effective and trusted decisions can be made, co-operation can replace dissension, and parties can be assured that assessment processes are fair.

The Panel has diligently pursued its mandate and trusts that this Report will be accepted as a satisfactory reflection of its work.

Introduction: Our Mandate and Our Journey

Our mandate

In her mandate letter from the Prime Minister, the Minister of Environment and Climate Change (the Minister) was directed to immediately review environmental assessment (EA) processes with these objectives: to restore public trust in EA; to introduce new, fair processes; and to get resources to market. On August 15, 2016, the Minister announced the establishment of our four-person Expert Panel (the Panel) to conduct this review.

The Terms of Reference established for the review directed us, the Panel, to engage broadly with Canadians, Indigenous Peoples, provinces and territories, and key stakeholders to develop recommendations to the Minister on how to improve federal EA processes.Footnote 1

Our journey

To fulfil our mandate, we have spent the past seven months travelling, listening, reading, thinking and writing.

We have heard from Indigenous Peoples, individual Canadians, environmental groups, EA practitioners, consultants, academics, industry, provincial EA offices and federal departments. Through all these interactions, we each grew individually as we came to understand many different points of view surrounding EA in Canada.Footnote 2

Our travels took us from coast to coast to coast. Throughout our journey, we encountered a fairly consistent pattern of concerns and issues.

- Proponents were divided: some were, by and large, happy with the system as it exists today while others expressed concerns that timelines are not met, assessment processes are not co-ordinated and processes across the three responsible authorities are not consistent.

- Environmental organizations and individuals expressed dissatisfaction and frustration with many elements of the process: they were challenged by a lack of adequate resources, troubled by tight timelines when faced with huge amounts of difficult technical data, unable to access pertinent information, exasperated by the lack of acknowledgement of their concerns, and dissatisfied with the lack of explanation provided for decisions.

- Indigenous Peoples shared many of these dissatisfactions but added more deep-seated concerns derived from what they considered a lack of respect for their rights and title.

- Provincial agencies told us that they wanted to see more effective co-operation with the federal environmental review process but were challenged by the inflexibility of the federal process timelines. They also reported a significant decline in federal scientific support for EA that was inhibiting timely and effective processes at both levels of government.

- Federal departments underlined their commitment to supporting EA, but they, too, felt stymied by inadequate resources.

Each region of the country added particular concerns and issues.

- In Atlantic Canada, offshore oil development, fisheries and electrical power development were dominant concerns.

- In Quebec, we heard about pipeline reviews, ports and power concerns, as well as the importance of federal/provincial co-ordination and understanding Indigenous concerns in the Far North.

- In Ontario, we heard from industry associations on how assessment could be improved. Matters about nuclear waste disposal, mining developments and Indigenous rights were common themes.

- In Manitoba and Saskatchewan, the issues ranged from pipelines to uranium mining, with messages about federal EA ranging from “Leave it alone because it is working” to “Throw it out and start over.”

- Alberta found us fully engaged in matters around oil and gas development and, in particular, issues related to developments in Fort McMurray. Indigenous Peoples in both Calgary and Fort McMurray stressed the problems brought on by the fast pace of development and cumulative impacts from many unassessed activities, such as in-situ oil extraction facilities. They found themselves asked to review thousands of pages of reports and data with few resources and even less time. In short, they were overwhelmed by what they faced. Some of the companies that presented before us understood the dilemma faced by Indigenous Groups and attempted to address it within their own processes. Overall, the pace and extent of development confounded the federal environmental assessment process as it pertains to development in the Athabasca region.

- Finally, in British Columbia, we found a hot-bed of concern around oil and gas pipelines, as well as mining projects, hydro-electrical projects and ports.

Across the country, in every place we visited, the presentations from Indigenous Peoples moved us. We heard how multiple developments in the northeast of British Columbia had impacted more than 80 per cent of Treaty 8 land without any effective assessment of impacts. We heard from the Innu Nation and the Nunatsiavut Government how the Lower Churchill Hydroelectric Project had created impacts that had the potential to wreak havoc on the wildlife upon which they depend. While these impacts had been foreseen to some extent in the assessment process, the project had been approved anyway. We heard many more cases where Indigenous Peoples felt that their rights and interests had been neglected or ignored.

Views about federal EA across the various interests ranged from support to all-out opposition. It was clear, however, that current assessment processes under the Canadian Environmental Assessment Act, 2012 (CEAA 2012) are incapable of resolving these disparate points of view.

In general, we did not hear strident opposition to the development of projects, although in a few cases there were those who held that certain projects should not have gone ahead. Rather we heard that, when communities, proponents and governments work together with mutual respect and understanding in a process that is open, inclusive and trusted, assessment processes can deliver better projects, bring society more benefits than costs and contribute positively to Canada’s sustainable future.

A comment made by a community leader in Prince Rupert summed up the essence of what EA should help achieve: when you come into this world, you receive a full basket, and it is your obligation to pass a full basket on to the next generation.Footnote 3 We believe that our task is to help ensure this lofty goal can be met.

Section 1 – Outlining the Vision

1.1 Meeting the challenge

Participants told us that they want an assessment process that protects the physical and biological environment, promotes social harmony and facilitates economic opportunities. They are looking to enhance long-term well-being for themselves, their fellow citizens and society as a whole through a rigorous assessment process that will achieve decisions that are considered fair by all parties.

Our review of EA is happening in the “heat of the moment.” Some of the most controversial projects in a generation have been, or continue to be, under review. Added to this is the controversy surrounding CEAA 2012 itself which, in many ways, is a far cry from what came before. While CEAA 2012 improved EA processes for some, it also sowed the seeds of distrust in many segments of society: it imposed unrealistically short timelines for the review of long, complex documents by interested parties; it vastly reduced the number of projects subject to review; and it placed more accountability for some assessment decision-making in the political realm. In essence, CEAA 2012 fuelled some of the dissension around project assessment today.

While the CEAA 2012 process defines the starting point for our work, we have looked back in time through the development of EA in Canada. What we see is a pendulum of policy that we believe has swung too far. The process we envision occupies a middle ground between the assessment practices from the 1990s and those in practice today. It also builds upon the structures and laws that are in place. We are not proposing the creation of something entirely new.

There is a tendency for people to judge the effectiveness of an assessment process on how it might apply to the largest and most controversial projects. While this is important, it must be remembered that assessment applies to far more than projects that can fill the nightly news. Our vision was to design a process that could deal effectively with the large controversial projects and very successfully with the many less controversial projects.

The need to respect one another and to listen to, hear and understand each other’s perspectives were central themes that emerged across the country. These have become the building blocks around which we built our vision for an effective assessment process. We concluded that the commitment to be empathetic, to search for common ground and to build toward consensus were the keys to success.

The term “social license” came to our attention in numerous ways. We took social license to mean the broad-based acceptance of a project or activity by the Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities that would be affected by the project. Acquiring social license will most certainly help a proponent gain approval for a project. We concluded that an effective assessment process should achieve two essential outcomes: pave the way for regulatory approval of accepted projects, and facilitate a proponent’s acquisition of social license.

Co-operation among all orders of government – federal, provincial and Indigenous – is essential to successful implementation of assessment in Canada. The Constitution splits jurisdiction for many of the matters that underlie the determination of whether, and under what conditions, a project would be good for Canada. Thus, effective assessment will normally require governments to work together.

A new assessment process must address the inequity felt by Indigenous Peoples. Reconciliation between Indigenous and non-Indigenous people demands it. Our mandate asks us to reflect the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP) in new assessment processes. During our meetings in Inuvik, we heard how the EA process in the Inuvialuit Settlement Region integrates Aboriginal rights and title. We saw the effectiveness that resulted from processes that are open, inclusive and trusted by affected communities. Assessments are conducted in open and collaborative ways to ensure that Indigenous Peoples’ interests are accounted for. Indigenous Groups are fully involved in making decisions about projects in their territory. The processes in northern Canada beyond the Inuvialuit Settlement Region were all commended to us for their effectiveness in reflecting the principles of UNDRIP in EA.

We understand, of course, that the political, demographic and community circumstances in northern Canada are not those further south, so the lessons from the North may not be directly transferable. However, the northern experience does offer guidance for resolving some of the concerns of Indigenous Peoples by providing for their involvement throughout the assessment process and in decision-making about projects that have the potential to affect their rights.

Advancing Canada’s economy is about generating job-supporting economic growth across all sectors. Infrastructure projects and the resource industries are among those most affected by the assessment processes. We believe that the process we propose, which is guided by principles designed to restore public trust and confidence, will facilitate the investment in these sections that is necessary to grow Canada’s economy in ways that will contribute positively to a sustainable future.

Leadership from the federal government toward improving the project assessment process across Canada would benefit every Canadian. We believe that this review provides the opportunity to raise the bar on assessment processes so that effective and trusted decisions can be made, co-operation can be built and participants can be assured that assessment processes are fair.

We believe that the assessment process envisioned in our model will meet the test. It will protect the physical and biological environment, promote social harmony and facilitate economic development.

1.2 From environmental assessment to impact assessment

A matter that was heard resoundingly from Canadians was the need for an EA process to move beyond the bio-physical environment to encompass all impacts, both positive and negative, likely to result from a project. The many presenters who raised this suggested that social issues, economic opportunities, health impacts and cultural concerns should be considered.

As a consequence, we believe that what is now “environmental assessment” should become “impact assessment.” This new approach would not be limited in its breadth but would instead be all-encompassing. Progress towards this modern assessment regime will be facilitated by moving from EA to impact assessment (IA).

Changing the name of the federal process to impact assessment underscores the shift in thinking that is needed to enable practitioners and Canadians to understand the substantive changes being proposed in our Report.

1.3 The principles guiding our vision

As we listened to presenters and read the many submissions presented to us, we came to understand that any new, effective assessment process must be governed by four fundamental principles.

Transparent

Presenters repeatedly expressed concerns that discussion between regulators and proponents occurred behind "closed doors," that decisions came out of a "black box" without explanation or accompanying rationale, and that they did not know whether their comments had been considered. This perception contributes to a sense of suspicion and distrust among many participants in the assessment process and a belief among many that the processes are "rigged" in favour of proponents.

To restore trust and confidence in assessment processes, people must be able to see and understand how the process is being applied, how assessments are being undertaken and how decisions are being made. Without this transparency, no process will be trusted. Therefore, we concluded that, in order to restore the public’s trust, the new assessment process for Canada must be transparent.

Inclusive

The assessment process can contribute positively to a project's social license if, and only if, that process takes into account the concerns of all parties who consider themselves or their interests to be affected by that project. The exclusion of individuals or groups from the assessment process erodes any sense of justice and fairness.

Likewise, excluding issues from assessment when there are individuals who have an interest in having those issues considered also erodes the sense of justice and fairness. Concerns were frequently expressed that important, valued components were left out while tangential matters were included. Matters such as impact on Aboriginal rights and title were not properly included in the scope of the assessment. Socio-economic effects were often underplayed.

Considering all of these perspectives, we conclude that, to be considered just and fair, the new assessment process must be inclusive.

Informed

Submissions received over the course of our hearings repeatedly stressed that the assessment process must be based on unbiased, adequate, accessible and complete information about impacts, issues, concerns and processes. People called for information to be presented in a way that that they could understand, for technical scientific information to be translated into plain language, for information and data to be easily accessible, and for Indigenous knowledge and community knowledge to be integrated with western science as the foundation for decision-making. Moreover, there was a strong expression of the need for the information to be independent of the proponent and special interests.

In order to ensure confidence in the new assessment process, we conclude that it must be entirely based on evidence that is, and is seen to be, unbiased, accurate, accessible and complete. The new assessment process must be informed.

Meaningful

Many presenters expressed the view that the current assessment process was just window-dressing, that the decision in favour of a project was always a foregone conclusion, and that there was no place in the process for a finding of “no-go.” Receiving a report of many thousands of pages and being required to prepare a response in 30 days did not allow meaningful input. Responses were often not provided to interventions by the public, leaving people to feel that their perspectives were not taken into account or that they were being ignored. In short, some groups felt that participation in the EA process was a waste of time and effort. Many presenters also felt that conditions attached to the approval of a project were ineffective and that follow-up was often minimal to non-existent. This led some to conclude that the assessment process itself did not result in meaningful undertakings.

In order to rebuild confidence and trust in IA, we conclude that the process must be perceived by interveners to give them a real opportunity to be heard and to feel that they have had a chance to influence the ultimate decisions. The new assessment process must be meaningful.

Moving forward

As we drew lessons from what we had heard across the country, we came to the conclusion that we need to improve the way we plan for development in our country. We believe that Canadians deserve better and that it is entirely possible to deliver better. Our Report explains how to achieve this.

The process we envision would encourage co-operation and reduce conflict. It would be clear and easy to understand. It would be predictable, consistent, comprehensive and open. It would be independent of either real or apprehended conflicts of interest and bias. It would be disciplined in duration and cost. It would facilitate the opportunity to make meaningful contributions by anyone who wanted to participate. It would foster a culture of learning so that assessments became more effective and efficient over time. It would facilitate co-operation with the provinces and First Nations to ensure the goal of “one project, one review” is achieved. And it would involve monitoring and follow-up to ensure that expectations at the time of decisions were being realized. If successfully implemented, references to the courts should be the exception rather than the rule.

Participants from the interested public and civil society organizations will find the opportunity to be engaged from the outset to the completion of a review. They will be able to access the information they need to formulate and present informed viewpoints. And they will know how their comments were addressed.

Indigenous Peoples will see many elements of UNDRIP reflected in the vision. Rather than finding themselves left on the sidelines of discussion around projects that affect them, Indigenous Peoples will be part of the decision-making process.

Proponents will secure their social license as they proceed through the project assessment that lies at the heart of the new model of assessment. The collaborative mechanisms we envisage will move the process from conflict toward consensus and should facilitate the building of positive relationships among proponents and intervening parties.

Provinces will see a process that rests on co-operation among all orders of government. Both the mechanisms and the incentive for enhanced co-operation in assessment are fundamental to this new model.

Scientists will benefit from a renewed emphasis on open data so that new scientific endeavours can benefit from knowing what has gone before. The emphasis in the new vision that decisions be fully informed by evidence – whether western science, Indigenous knowledge or community knowledge – will benefit all parties.

The Panel has diligently pursued its mandate and trusts that this Report will be accepted as a satisfactory reflection of its work.

Section 2 – Developing the Vision

In this section, we outline recommendations about the purpose of impact assessment (IA), the importance of co-operation among jurisdictions, integrating Indigenous considerations into IA processes, enabling meaningful participation and ensuring evidence-based decision-making. Each of these aspects is fundamental to ensuring that federal IA is robust and responds effectively to what we heard across the country.

2.1 The Purpose of Federal Impact Assessment

Context

Impact assessment (IA) aims to identify and address potential issues and concerns early in the design of projects, plans and policies. In so doing, it can contribute to the creation of positive relationships among various interest groups, including reconciliation between Indigenous Peoples and non-Indigenous peoples. IA also aims to contribute to the protection of the bio-physical environment and the long-term well-being of Canadians by gathering proper information to inform decision-making. At a project scale, IA should improve project design and ensure appropriate mitigation measures and monitoring programs are implemented. In sum, IA processes should give Canadians confidence that projects, plans and policies have been adequately assessed.

IA, as defined by the International Association for Impact Assessment, is “the process of identifying the future consequences of a current or proposed action.”Footnote 4 Whereas most environmental laws and policies set standards to regulate aspects of development such as air emissions, water withdrawals, waste management and land use, IA goes beyond a review of individual aspects of a proposal to look at the big picture – what is proposed and what may be impacted? In other words, IA processes implement the proverb, “Look before you leap.”

To achieve this outcome, the type of assessment undertaken must be appropriate for the circumstance. There are three scales of IA most commonly referenced, which are Strategic IA, Regional IA and Project IA.Footnote 5 While the overarching purposes of each scale of assessment are consistent, it is important to apply the right tool to the job at hand in order to be most effective.

In Canada, the purpose of what has been called environmental assessment (EA) has evolved over time, from the federal Environmental Assessment and Review Process for major policy initiatives in 1974, through the first iteration of the Canadian Environmental Assessment Act in 1992 (CEAA 1992), to the more recent process implemented through the Canadian Environmental Assessment Act, 2012 (CEAA 2012). The types of activities undergoing review, the effects considered and the decisions made over time have shaped public perceptions of federal IA and its ability to meet the needs of Canadians.

Federal IAs require clear direction on both the purpose and parameters of the process. There are many options on how best to do IA. In considering the future of IA in Canada, it is necessary to begin by answering the following fundamental questions through a consideration of jurisdiction, significance and sustainability, and IA’s role as a planning tool:

- What should require federal IA?

- When should a federal IA for a project, plan or policy begin?

- What should federal IA look at?

2.1.1 Federal jurisdiction

What we heard

Participants considered federal jurisdiction as it relates to IA in a variety of ways. Some saw it as permitting, or even requiring, a wider consideration of issues in federal IA. Others saw a very narrow and specific role for federal IA within the confines of federal jurisdiction. However, while there was divergence in this regard, one common thread expressed across a broad range of perspectives was that it should be clear when a federal IA will be required.

Findings and recommendations

The Panel places great importance on the fact that federal IA must respect Canada’s Constitution. It thus cannot apply to every project or every decision that may affect the environment.Footnote 6 Federal IAs should only be conducted on a project, plan or policy that has clear links to matters of federal interest. These federal interests include, at a minimum, federal lands, federal funding and federal government as proponent, as well as:

- species at risk;

- fish;

- marine plants;

- migratory birds;

- Indigenous Peoples and lands;

- greenhouse gas emissions of national significance;

- watershed or airshed effects crossing provincial or national boundaries;

- navigation and shipping;

- aeronautics;

- activities crossing provincial or national boundaries and works related to those activities; or

- activities related to nuclear energy.

The careful consideration and incorporation of federal jurisdiction is the starting point from which to answer the question of when federal IA should apply.

The Panel recommends that federal interest be central in determining whether an IA should be required for a given project, region, plan or policy.

2.1.2 Impact assessment as a planning tool

What we heard

Planning emerged as a valued purpose of IA and was seen as an opportunity to proactively address potential project problems from the outset. Public and Indigenous participants expressed a resounding desire and need for early engagement in project design and planning. Many saw early involvement as an opportunity to reduce conflict later in the IA process and as a way that adversarial relationships with project proponents might be avoided at the outset, prior to large investments of time and money into publicly contested options.

“By critically examining development actions while they are still being conceptualized, IA contributes to fostering a balanced and sustainable future.”

Findings and recommendations

It is essential to maximize the role of planning and the value that can be derived from it within the federal IA process. Over time, environmental regulatory requirements have increased, and IA has emerged as one of the most important tools to integrate these requirements and look at the big picture. To do that effectively, project IAs must begin early in project design, and continue through the undertaking of studies and through to an informed decision.

While project IA typically occurs prior to the majority of regulatory requirements being determined and sets the foundation for environmental considerations to be incorporated throughout decision-making, assessments do not currently start early enough. Without input from potentially impacted communities and Indigenous Groups, as well as potential experts and regulators, a proponent’s studies will not be as fully informed as possible, making it likely that the project itself will be suboptimal. This is the process we have today where, by the time project proponents submit a detailed project description to initiate the current assessment process, many of the most important decisions about how the project is to be undertaken have already been made.

“The earlier you can get in and you go in less prescriptive — it's like if I have my home and there's a fellow— I want to build a pipeline. I go up to him and I said, you know, we want to build a pipeline. And we're going to build it right through your backyard. And we would like you to sign-off on it and we're really good people so everything is great . But if you go to them early and say, you know, we're building a pipeline from this place to that place . it'd probably be an easier conversation . And I think it's just really showing that respect for their thoughts and ideas and you're not just coming in after the fact.”

Early engagement is critical to fully inclusive and informed IA processes. Establishing relationships among proponents, interested publics, Indigenous Groups and potential regulators early in the design of activities can allow for concerns to be discussed and addressed in advance of critical decisions and investments. Early engagement of all interested parties will also facilitate transparent information sharing and decision-making. Starting consensus building and co-operation early in project planning can also reduce the adversarial nature of project reviews. Beginning in the planning phase, face-to-face engagement should be prioritized to maximize relationship building, constructive dialogue and opportunities for consensus.

Additional benefits include offering a forum to build trusting relationships among proponents, governments and local communities, identify potential impacts to Aboriginal and treaty rights Footnote 7 across the five pillars of sustainability, and integrate Indigenous knowledge, laws and customs into the process.

This proposed Planning Phase should lead to a more effective and efficient process. In the development of projects today, some proponents may already undertake a conceptual Planning Phase, prior to the initiation of the current assessment process.Footnote 8 Bringing this conceptual Planning Phase into the formal IA process would aid both proponents and communities by helping facilitate relationship-building and trust. It would also provide clarity to the proponent early in the process with regard to the main issues of concern. For communities and Indigenous Groups, the Planning Phase would allow them to identify important information that can be inputted into the IA.

Overall, early engagement enhances IA as a planning tool by opening the process up to include collaborative planning of the project or region in question, as well as the planning and undertaking of the studies required to assess its impacts.

The Panel recommends that federal IA should begin with a legislated Planning Phase that, for projects, occurs early in project development before design elements are finalized.

2.1.3 From significance to sustainability

What we heard

While there were some exceptions, it was undoubtedly the case that there was broad interest from presenters across Canada in adopting a sustainability focus for federal IA. Participants shared their diverse notions of sustainability, many of which were holistic and called for the consideration of future generations. Many expressed support for the concept of next-generation EA, the objective of which “is to protect and enhance the resilience of desirable bio-physical, socio-ecological and human systems and to foster and facilitate creative innovation and just transitions to more sustainable practices.”Footnote 9

“The two core purposes of federal EA law and associated processes are: to strengthen progress towards sustainability, including through positive contributions to lasting socio-economic and biophysical wellbeing, while avoiding and mitigating adverse environmental effects; and to enhance the capability, credibility and learning outcomes of EA-related deliberations and decision making.”

Many participants identified the need for clarity and direction regarding the meaning and application of sustainability in an IA context. Sustainability criteria could be developed for each project but should be guided by transparent standards. There was a desire for a more holistic decision, based on a broad suite of evidence, with clearly articulated rationales. In cases where a project is found to not have a positive contribution to sustainability or to have unacceptable negative effects on a given area of sustainability, most participants wanted this decision to be a clear and firm “no.”

Many of these same participants also identified challenges with the current focus on avoiding or minimizing significant adverse environmental effects, as well as the associated cabinet decisions of when significant adverse environmental effects were justified.

Findings and recommendations

Sustainability should be central to federal IA. To meet the needs of current and future generations, federal IA should provide assurance that approved projects, plans and policies contribute a net benefit to environmental, social, economic, health and cultural well-being.

In evaluating what federal IA should consider, there is historic context for the current focus on the significance of adverse environmental effects. This focus came to prominence in Canada’s 1984 Environmental Assessment and Review Process Guidelines Order and was reinforced in CEAA 1992. The significance approach remains in place under the current assessment legislation, CEAA 2012.

However, this approach may no longer be appropriate. First, it focuses only on negative effects, and second, because significance is a “yes/no” decision, it results in adversarial relations at the outset. Instead, assessment should in the future include a review of net benefits and a review of trade-offs between benefits and negative effects.

“Sustainability means the conditions under which ecosystem function, socio-cultural and economic well-being are maintained and risk to ecological integrity is low, thus providing the ecological foundation for the long-term socio-cultural and economic well-being.”

IA also needs to better address a review of alternatives. There is a need for an open and informed discussion about the nature of developments, and including the review of pros and cons of more than one option is essential.

The concept of sustainability provides all the key ingredients to adequately address these needs. A sustainability approach seeks to ensure that projects are planned to avoid or minimize harm and deliver benefits for current and future generations. It requires honest consideration of both positive and negative impacts and provides space for an analysis of alternatives. It is consistent with international environmental practices and trends and provides sufficient scope to meaningfully reflect UNDRIP. Its ultimate goal is to advance initiatives that contribute to lasting improvement in society’s well-being.

To put these ideas into action, a clear understanding of sustainability is required.

“Environmental assessment should include a review of the impacts of all living beings, including but not limited to economic, social, cultural and health-related factors.”

Sustainability is a term that has different meanings to different people in different contexts. As such, on its own it may pose challenges to implementation. Therefore, at the outset of each assessment, a sustainability framework should be defined to address specific aspects of a project and the potential for interactions and impacts on five pillars of sustainability:

- environmental

- social

- economic

- health

- cultural.

Expanding upon the three pillars typically referenced – environmental, social and economic – brings necessary emphasis to potential important impacts in IA. These five pillars are interrelated, and all five must be examined to assess impacts to Aboriginal and treaty rights and interests. Additionally, the assessment of alternatives can be undertaken, with consideration of the impacts and benefits of each alternative on the relevant components of sustainability.

A clear and transparent framework for evaluating impacts to these components needs to be established. The sustainability questions developed by the Joint Panel for the Kemess North Gold-Copper Mine provide a useful starting point. With some paraphrasing, these questions ask:

- Is adequate protection provided though all phases of the project or plan?

- Are net benefits provided locally, regionally and nationally?

- Is there a net contribution to the well-being of potentially affected people and to their interests and aspirations?

- Are the benefits and costs fairly distributed?

- Are benefits provided now, without compromising the ability of future generations to benefit?

These questions should be asked throughout an IA, but at the beginning of an IA, these questions can help guide the review of alternatives and development of specific issues to be assessed. These questions should allow the local context – such as ecologically sensitive areas, specific social dynamics, or resources required for preferred cultural practices – to be reflected in the IA.

This sustainability framework includes each of the pillars and the interactions among them. While the objective should be to minimize the times when achieving benefits in one pillar comes at the cost of losses to other pillars, trade-offs may be necessary. In this model, the ultimate IA decision on a project will apply the sustainability framework in the form of a sustainability test. This test should be project-specific and answer questions similar to the five questions set out above using clear, objective criteria.

An IA process based on sustainability must focus on activities with potential impacts on matters of federal interest that are consequential to present and future generations. The term “consequential” is of utmost importance in triggering meaningful federal IA. Impacts that are consequential to present and future generations are, for example, impacts that:

- affect multiple matters of federal interest;

- are of a duration that will be multi-generational; and/or

- extend beyond a project site in geographic extent.

Other factors, such as if the impact is in an ecologically or culturally sensitive area, or if the impact has the potential to contribute to cumulative impacts, may also be deemed consequential impacts to present and future generations.

The Panel recommends that sustainability be central to IA. The likelihood of consequential impacts on matters of federal interest should determine whether an IA would be required.

The Panel believes that this sustainability approach will remedy concerns with current decisions of justification of significant adverse effects. In order to contribute effectively to Canada’s future, IA itself must judge more than the adverse environmental impacts of a development project. IA should be able to analyse, discuss and weigh negative and positive project impacts openly. Projects which provide a net benefit to the country should be approved. Those that do not should not.

An IA process should result in a clear decision, informed by the sustainability test. If a project fails to pass the test, IA decision-makers should have the authority to say “no” to the project as proposed and such a decision should restrict the issuance of subsequent federal regulatory approvals. If a project is found to contribute to sustainability at the IA stage, subsequent federal regulatory approvals would be informed by the outcomes of the IA.

The Panel recommends that federal IA decide whether a project should proceed based on that project’s contribution to sustainability.

2.1.4 Tiering

Project-specific assessments have an important role to play to ensure new activities contribute to sustainability. Many sustainability questions, however, cannot be properly assessed at the scale of project IA. It is therefore necessary to examine whether strategic IA or regional IA can identify how policies and plans can better inform IAs.

Strategic IA will provide clarity on how federal policies can be effectively considered in regional and project IA. Regional IA will provide clarity on thresholds and objectives on matters of federal interest in a region and will inform and streamline project IA.

Therefore, a tiered approach should be implemented whereby strategic and regional IAs provide the policy and planning foundations for improved and efficient project IAs. The information gathered and knowledge gained at one tier of IA should inform IAs conducted at the lower tiers. For example, baseline data and plans from regional IAs should inform project IAs, allowing for a more thorough and efficient assessment of the project-specific issues at hand.

Enhanced interactions between projects, regions, plans and policies, and the pillars of sustainability are an important purpose of IA. A federal IA regime equipped with this suite of options can apply the best type of assessment to any given activity or decision.

The Panel recommends that IA legislation require the use of strategic and regional IAs to guide project IA.

2.2 Co-Operation Among Jurisdictions

Context

IA creates challenges for Canada’s system of government, with the requirement that a broad range of information be collected and evaluated but with no government having full authority to regulate all impacts. Federal, provincial, territorial, municipal and Indigenous governments may each have responsibility for the conduct of IA, but each level of government can only regulate matters within its jurisdiction.

For example, in the current environmental assessment context, federal decisions must be tied to matters within federal authority such as fish and fish habitat, provincial decisions must be tied to matters within provincial authority such as provincial land and certain kinds of resource development, and municipal decisions must be consistent with authority delegated to municipalities by provinces. Similarly, each jurisdiction may also lead responsibility to make decisions on the pillars of sustainable development – environmental, economic, social, cultural or health.

Indigenous jurisdiction over IA has a more complex legal basis. In some instances, IA is defined through self-governments agreements, modern treaties or agreements established under federal statutes such as the First Nation Land Management Act. In many instances, Indigenous Groups have inherent jurisdiction over their traditional territories, in alignment with Canada’s Constitution and the principles of UNDRIP.

Key Terms

Delegation: When a part of one jurisdiction’s (A) process is carried out by another person, body or jurisdiction. The process of jurisdiction A is applied by the delegated body.

Co-operation: Co-ordinate EA processes with the objective of “one project, one assessment.” All jurisdictions conduct their respective EAs, while aligning their processes to the extent possible.

Substitution: When an EA law or process of one jurisdiction (A) is substituted for an EA law or process of another jurisdiction (B). The process of jurisdiction A is applied to meet the obligations of jurisdiction B. Jurisdiction B makes its decisions based on the results of A’s process.

Equivalency: When it is determined that Jurisdiction A’s process is equal to Jurisdictions B’s process and they are therefore essentially the same. An assessment under B’s process is therefore not required and only A makes a decision at the end of the EA.

The federal environmental assessment process under CEAA 2012 includes provisions to enable co-ordination among jurisdictions, including delegation, co-operation, substitution and equivalency. Among federal and provincial governments, the general principle guiding co-operation is “one project, one assessment.” To implement this principle, many projects since the 1990s have been subject to joint federal-provincial panels. CEAA 2012 changed certain aspects of federal EA – such as timelines, authority to carry out EA and scope of EA – so that it became more difficult to carry out joints EAs. However, CEAA 2012 also encouraged substitution and equivalency, with British Columbia being the only province to reach a substitution agreement. The result of these changes is that current co-operative assessment practices have not achieved the goal on “one-project, one-assessment.” There are fewer joint panels and assessments now increasingly occur in parallel instead.

For sustainability to be advanced, all jurisdictions need to find a way to work together. As outlined previously, federal IA should be grounded in legal jurisdiction, start early in planning and focus on assessing contributions to sustainability. These foundations make co-operation among jurisdictions essential to ensure Canadians realize the benefits from IA.

2.2.1 Co-operation

What we heard

The Panel heard overwhelmingly that one project should be subject to only one assessment process. Participants emphasised that co-ordinating IA processes is key to ensuring that all impacts likely to result from a project are effectively considered. Co-ordinating multiple processes allows for the combining of strengths from each jurisdiction. It also provides process certainty for proponents and more meaningful engagement of the public and Indigenous Groups.

“Application of CEAA to a project should continue to provide for co-ordination (harmonization/substitution) of federal EA requirements with provincial/territorial EA requirements and processes to ensure “one project, one review.”

Many participants said there is a need for federal involvement in all IA processes because federal experts bring particular expertise on matters of federal interest and represent a national and potentially more neutral perspective on resource development. Participants also said they are less concerned about who leads the assessment process than about the process being fair, robust and transparent.

In a full day meeting with provincial and territorial environmental assessment practitioners,Footnote 10 the Panel heard that a common objective is a rigorous environmental assessment process that enables effective public and Indigenous engagement. Participants emphasized the need for a flexible federal assessment process to facilitate effective co-operation, reduce duplication and respect jurisdictional lines. They also reiterated the importance of federal expert engagement in all IAs, even in circumstances where only the provincial or territorial process applies.

In a full day meeting with federal departments,Footnote 11 the Panel heard that there is a need to bring together federal, provincial and Indigenous knowledge to understand the effects of an activity. Departments noted that better federal and provincial co-ordination mechanisms are needed and that co-ordination should occur early. Departments suggested that good co-ordination has occurred in past joint review panels.

Findings and recommendations

The principle of “one project, one assessment” is central to implementing IA around the five pillars of sustainability. Other options will result in fragmented, inefficient and inconsistent IAs and project decisions.

In Canada, many jurisdictions have the expertise, knowledge, best practices and capacity to contribute to IA. For example, the federal and provincial governments may focus on closely related issues, such as impacts to water quality versus impacts to a fishery. Yet Indigenous Groups also have relevant knowledge on these topics related to the practise of their Aboriginal and treaty rights, their traditional and ongoing land use, and their laws, customs and institutions. Similarly, municipalities are the custodians of land use and the full range of local impacts that affect residents and their communities. Co-operation brings all of this expertise to the table to make informed decisions about how a project may best contribute to Canada’s sustainable future.

For most projects, potential impacts on the five pillars of sustainability will include areas beyond federal authority. Therefore, to further the values achieved by “one project, one assessment,” there must be co-operative decision-making about a project’s contribution to the long-term well-being of Canadians. This will likely require provincial involvement, as well as the involvement of any other government with a decision-making authority over the project subject to IA.

“An important feature of the federal EA regime is that, even where it falls short, it provides us access to the federal crown and federal departments.”

The principal benefits of co-operative IA are:

- integration of all interests and issues into one process;

- sharing and streamlining of costs due to the removal of duplication;

- conduct of joint public and Indigenous engagement activities;

- involvement of the best experts from all jurisdictions;

- collective review, weighing and evaluating of impacts, including trade-offs, across the five pillars of sustainability; and

- agreement on appropriate conditions to inform decision-making and approvals.

To date, the best examples of co-operation among jurisdictions have been joint review panels, backed up by general co-operation agreements between Canada and many provinces. As such, expanding the co-operation model to include all relevant jurisdictions is the preferred method to carry out jurisdictional co-ordination.

The Panel recommends that co-operation be the primary mechanism for co-ordination where multiple IA processes apply.

Mechanisms to support co-operation

Co-operation in IA may take a variety of forms. Most broadly, co-operation arrangements with provincial or Indigenous governments can outline how all future IAs in that jurisdiction will be undertaken. Co-operation arrangements can also be sector-specific to identify when, for example, a joint review panel would be appropriate, or project-specific to set out the membership of a specific review panel and scope of the review. Each type of arrangement has value in improving consistency and certainty for all parties engaged in the IA process.

Project-specific co-operation arrangements should be negotiated early in the project Planning Phase and form part of any agreement on the conduct of a project IA, from planning through to study, decision-making and follow up.

Co-operation agreements

The federal government should demonstrate leadership and initiate discussions to build a co-operative framework early in the development of a modernized IA regime. In addition to project-specific co-operation arrangements, overarching IA co-operation agreements are also a mechanism to support the implementation of a co-operative approach to IA in a region or jurisdiction.

Where co-operation agreements now exist between the federal and provincial government, or between the federal government and Indigenous Groups, they should be revisited to ensure that they reflect a sustainability-based IA model and meet the principle of harmonization upward, meaning co-operation to meet the highest standard of IA. Co-operation agreements should also demonstrate how the principles of UNDRIP would be reflected in co-operative assessment processes. The co-operation framework established by the Canadian Council of Ministers of the Environment in 1999 should be revisited and modernized to implement the principle of harmonization upward.

Co-operation with Indigenous Groups

Co-operation arrangements under a new IA regime should address the duty to consult and how the principles of UNDRIP are to be reflected in the IA process.