Syphilis in Canada: Technical report on epidemiological trends, determinants and interventions

Download the alternative format

(PDF format, 5.9 MB, 181 pages)

Organization: Public Health Agency of Canada

Published: 2020-11-18

Table of Contents

- Foreword

- Table of figures

- Table of tables

- Abbreviations

- Executive summary

- 1. Syphilis: Natural history, diagnosis and treatment

- 2. Burden of syphilis and co-infections

- 3. Epidemiological trends of syphilis in Canada, 2009-2018

- 4. Determinants and risk factors of syphilis in Canada

- 5. Congenital syphilis: Trends, determinants and response

- 5.1 Congenital syphilis trends in Canada over the past 25 years

- 5.2 Epidemiological situation across Provinces and Territories

- 5.3 Factors associated with Canadian trends

- 5.4 Comparison of recent trends in Canada to those of other countries

- 5.5 Addressing Congenital Syphilis in Canada: Potential solutions

- 6. Interventions and policy for syphilis prevention and control

- 7. Conclusion

- References

- Appendix A: Clinical algorithm for syphilis staging and treatment

- Appendix B: Case definitions of syphilis used in Canada

- Appendix C: Data and methods

- Appendix D: Rates of infectious syphilis per 100,000 population by sex in countries of the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, 2008-2017

- Appendix E: Proportion of cases by syphilis stage overall and by sex in Canada, 1991-2017

- Appendix F: Rates of reported cases of infectious syphilis per 100,000 population by age group and sex in Canada, 2009-2018

- Appendix G: Rates of reported cases of infectious syphilis by province/territory and by sex in Canada, 2009-2018

- Appendix H: Number of cases and rates of congenital syphilis, rates of infectious syphilis among women aged 15 – 39 and rates of infectious syphilis among females, 1993-2018

Foreword

The Centre for Communicable Diseases and Infection Control at the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) is pleased to present the report: Syphilis in Canada, Technical Report on Epidemiological Trends, Determinants and Interventions. The purpose of this report is to provide information to the public health sector, to clinicians and to policy makers about trends in syphilis cases and infection rates in Canada. This report was developed in response to the current rise of syphilis rates in Canada. It presents evidence on the current trends in rates of syphilis infection in Canada, associated risk factors, and some interventions that were implemented in response to the increase in cases of syphilis in Canada.

Syphilis is a notifiable disease in Canada. The report Syphilis in Canada, Technical Report on Epidemiological Trends, Determinants and Interventions is primarily based on surveillance data submitted to the Canadian Notifiable Disease Surveillance System (CNDSS) by provincial and territorial health authorities and also presents data published in provincial and territorial surveillance reports as well as information from the scientific literature and from the grey literature including media releases and international reports.

We welcome all comments and suggestions for improving future publications. We invite you to contact the staff of the Centre for Communicable Diseases and Infection Control, Public Health Agency of Canada, at phac.sti-hep-its.aspc@canada.ca.

Table of figures

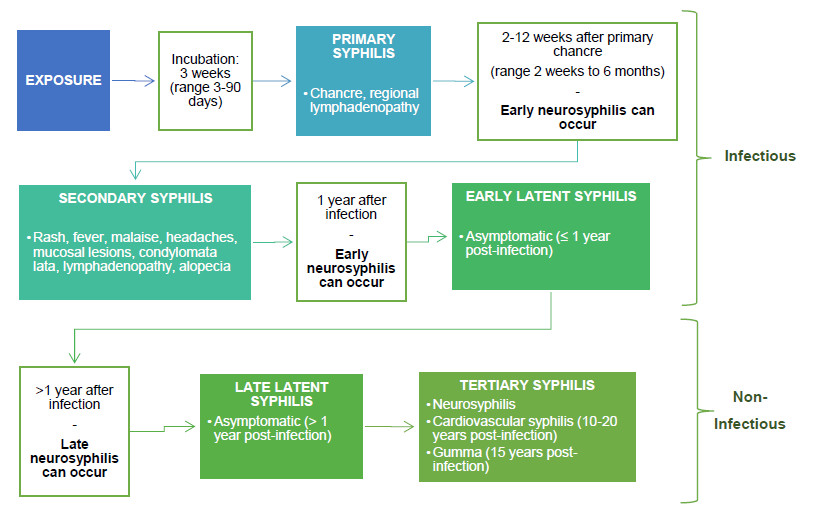

- Figure 1. Summary of the natural history of untreated syphilis and its associated clinical manifestations

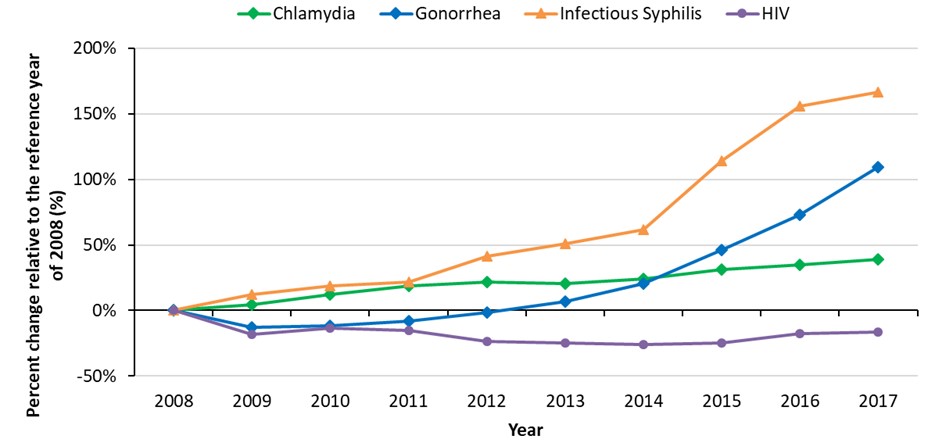

- Figure 2. Percentage change in rates of reported cases of STBBI in Canada, relative to the reference year of 2008, 2008-2017

- Figure 3. Factors contributing to the HIV-syphilis syndemic

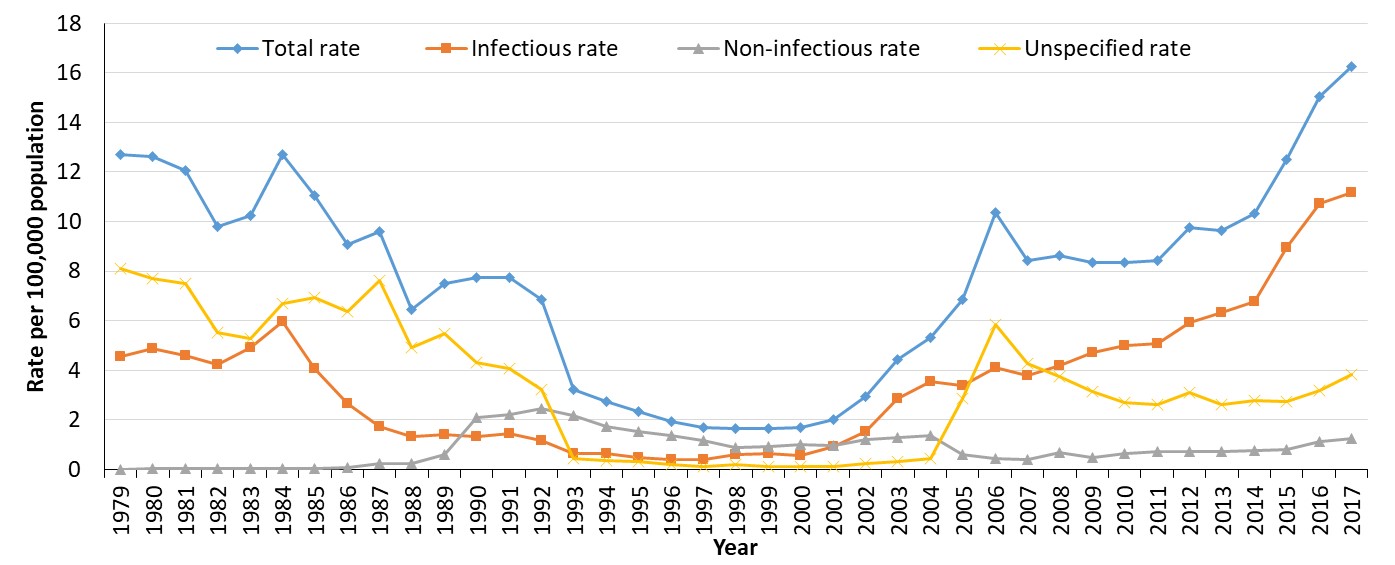

- Figure 4. Total, infectious stages and non-infectious stages rates of reported cases of syphilis in Canada, 1979-2017

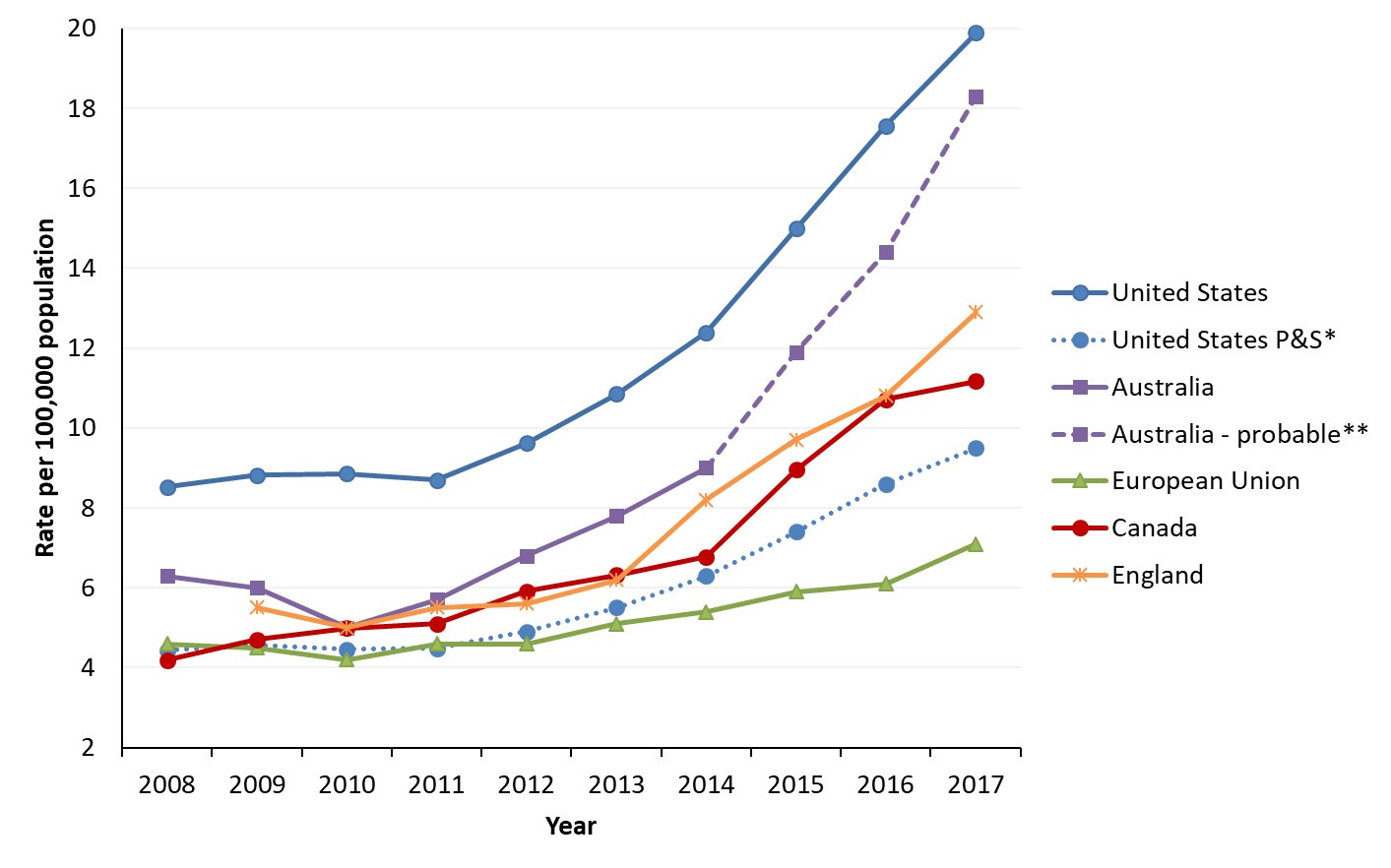

- Figure 5. Comparison of rates of reported cases of infectious syphilis in OECD countries, 2008-2017

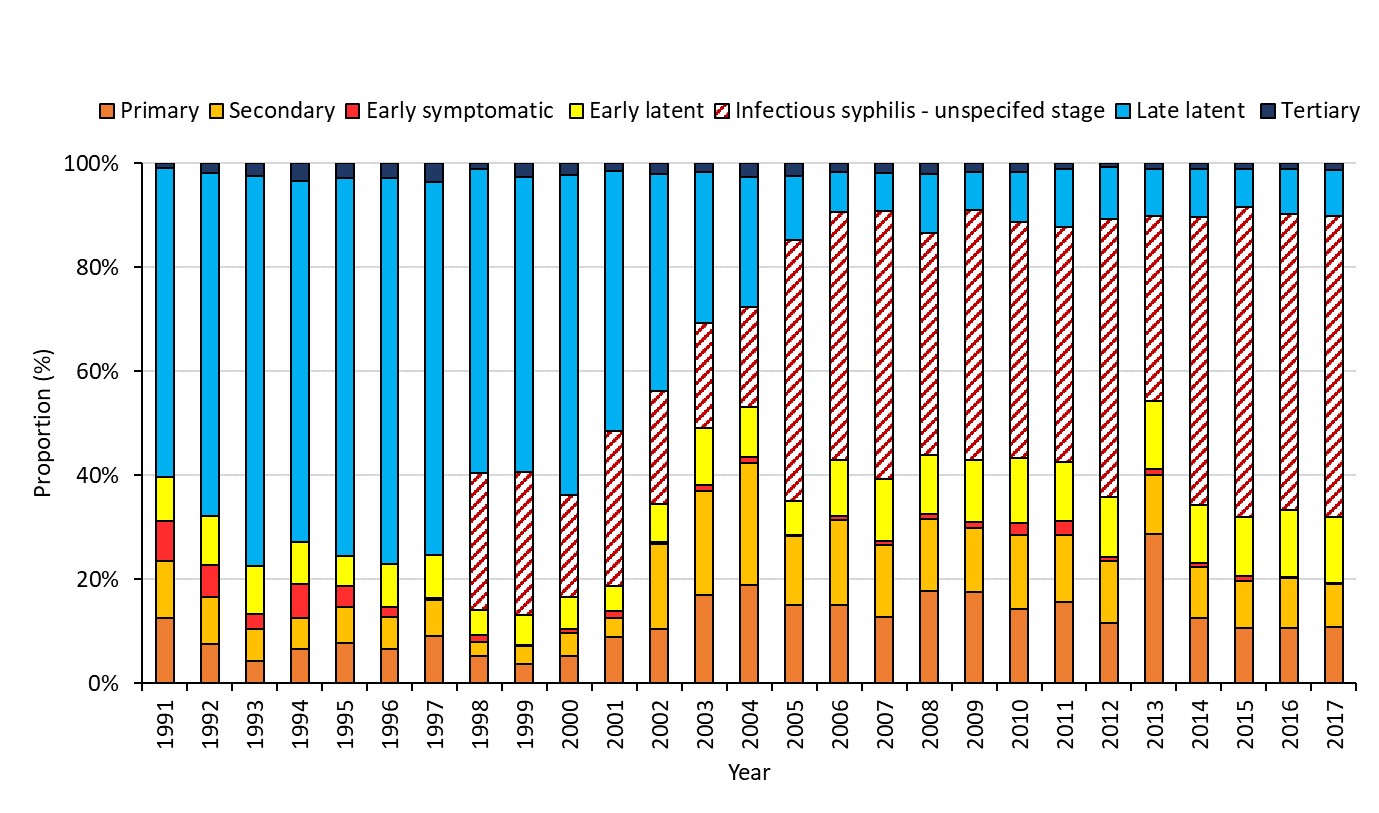

- Figure 6. Proportion of reported cases of syphilis by stage of infection in Canada, 1991-2017

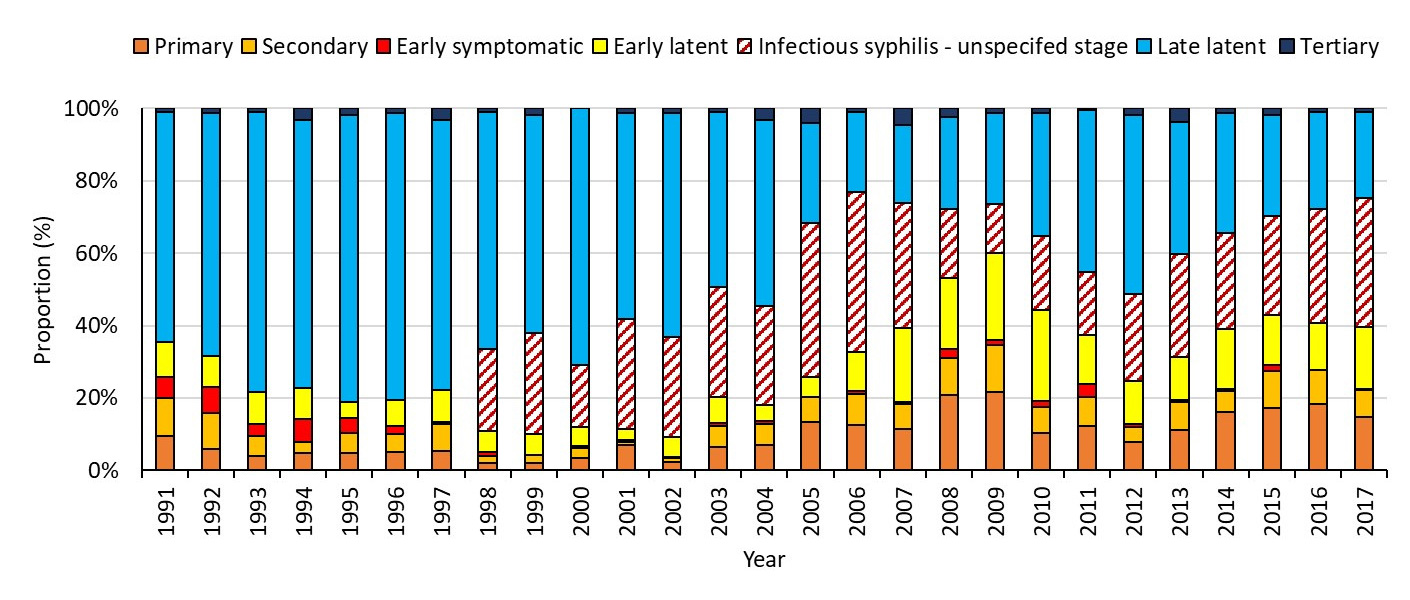

- Figure 7. Proportion of reported cases of syphilis by stage of infection among males in Canada, 1991-2017

- Figure 8. Proportion of reported cases of syphilis by stage of infection among females in Canada, 1991-2017

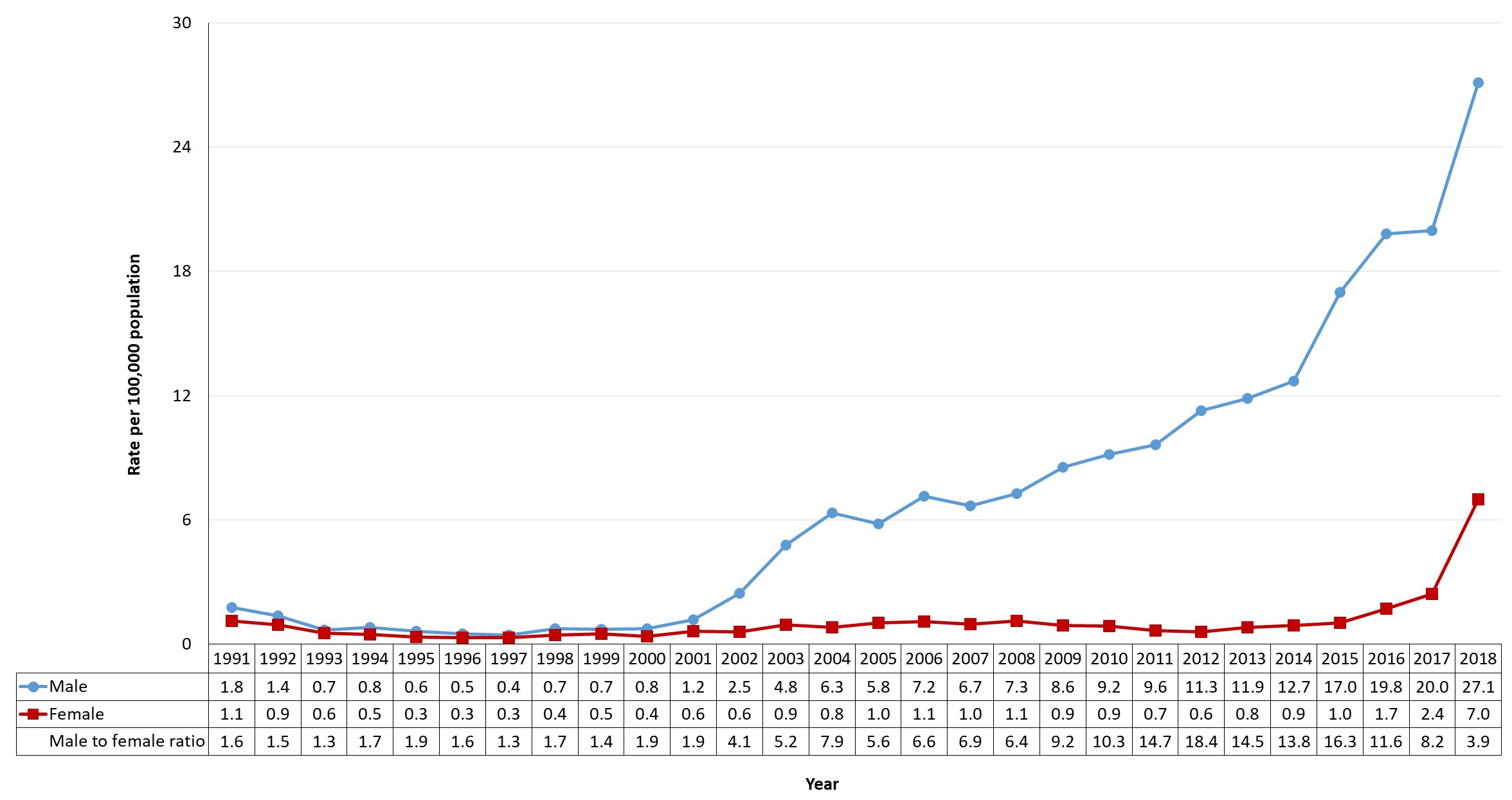

- Figure 9. Rates of reported cases of infectious syphilis by sex in Canada, 1991-2018

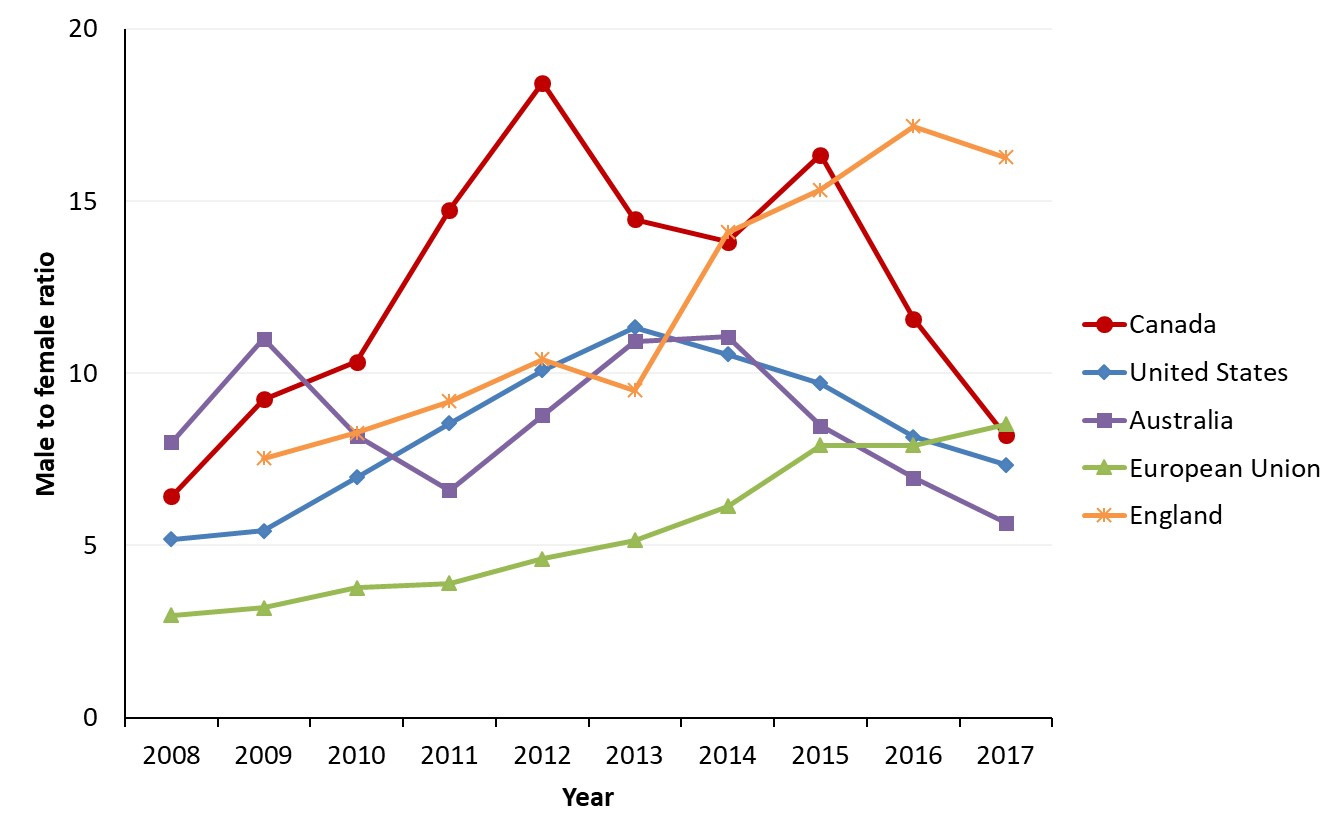

- Figure 10. Comparison of reported male-to-female rate ratios of infectious syphilis in OECD countries, 2008-2017

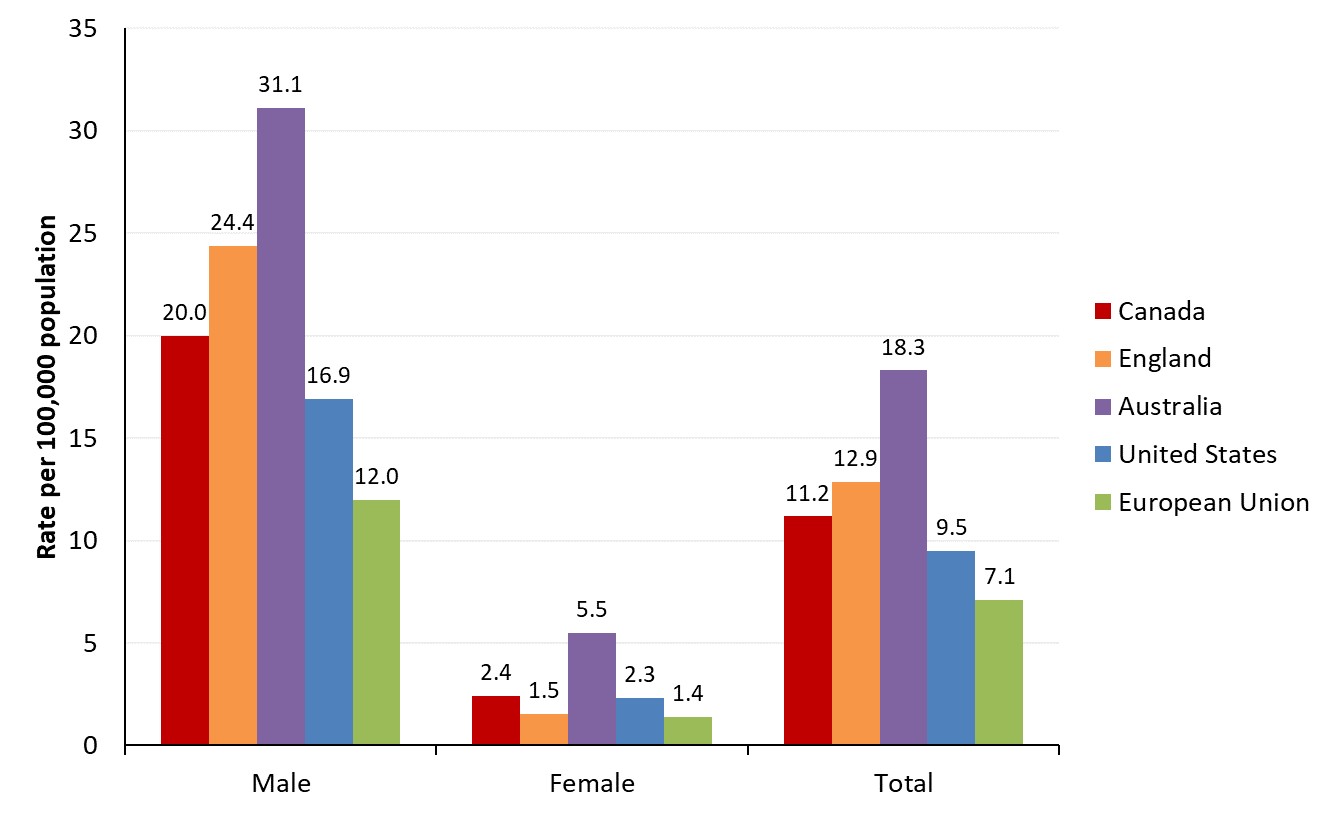

- Figure 11. Rates of reported cases of infectious syphilis by sex in OECD countries, 2017

- Figure 12. Rates of reported cases of infectious syphilis by age group in Canada, 1991-2018

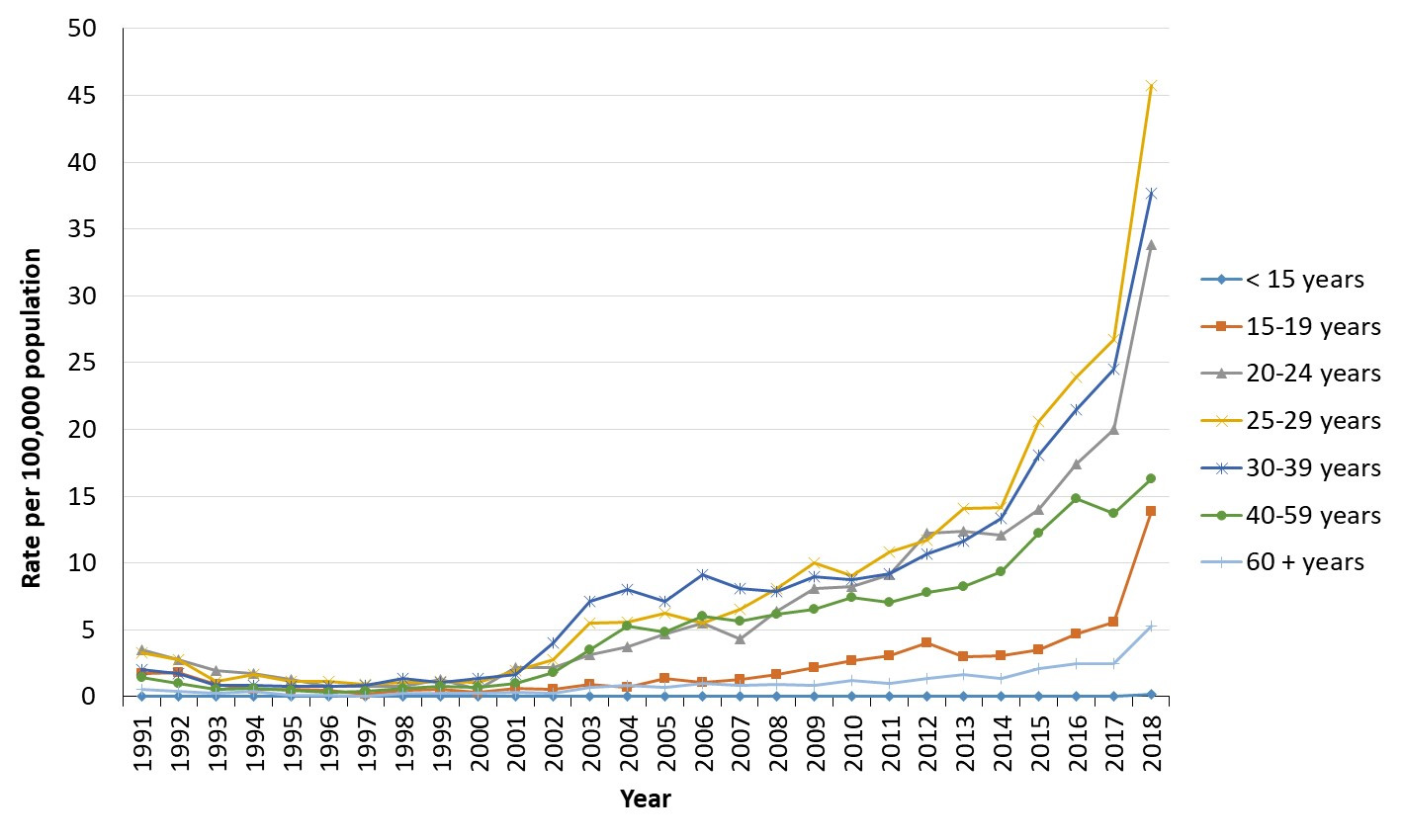

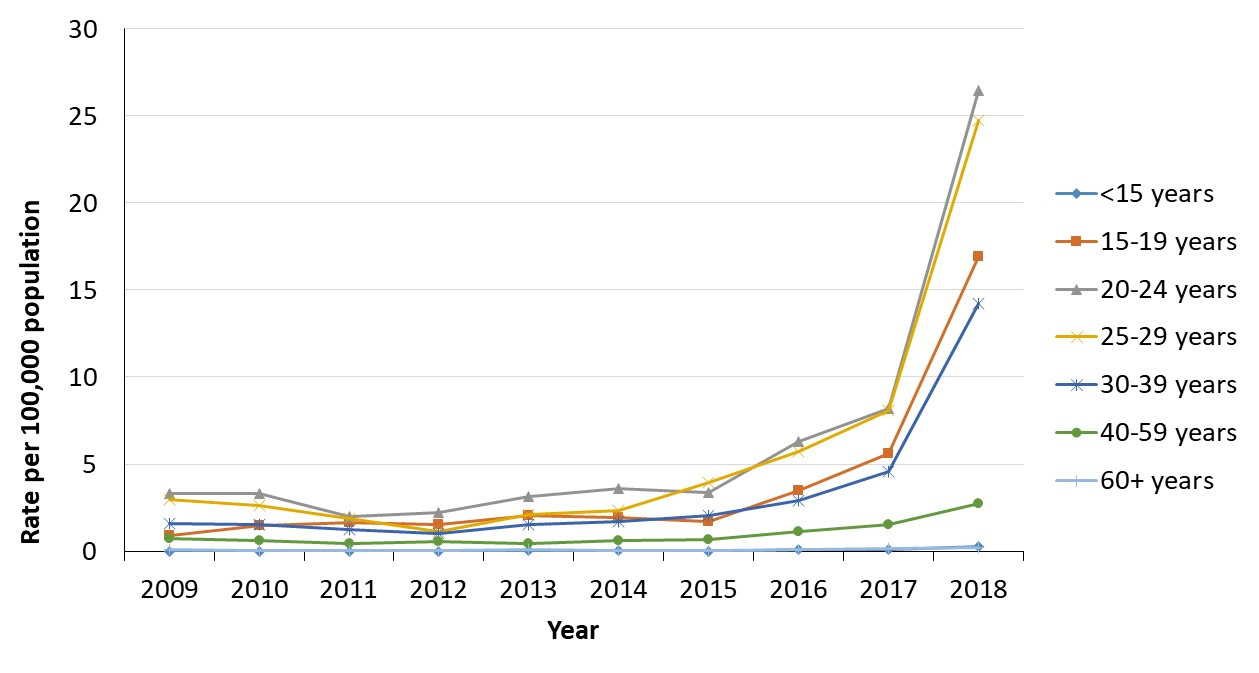

- Figure 13. Rates of reported cases of infectious syphilis by age group among males in Canada, 2009-2018

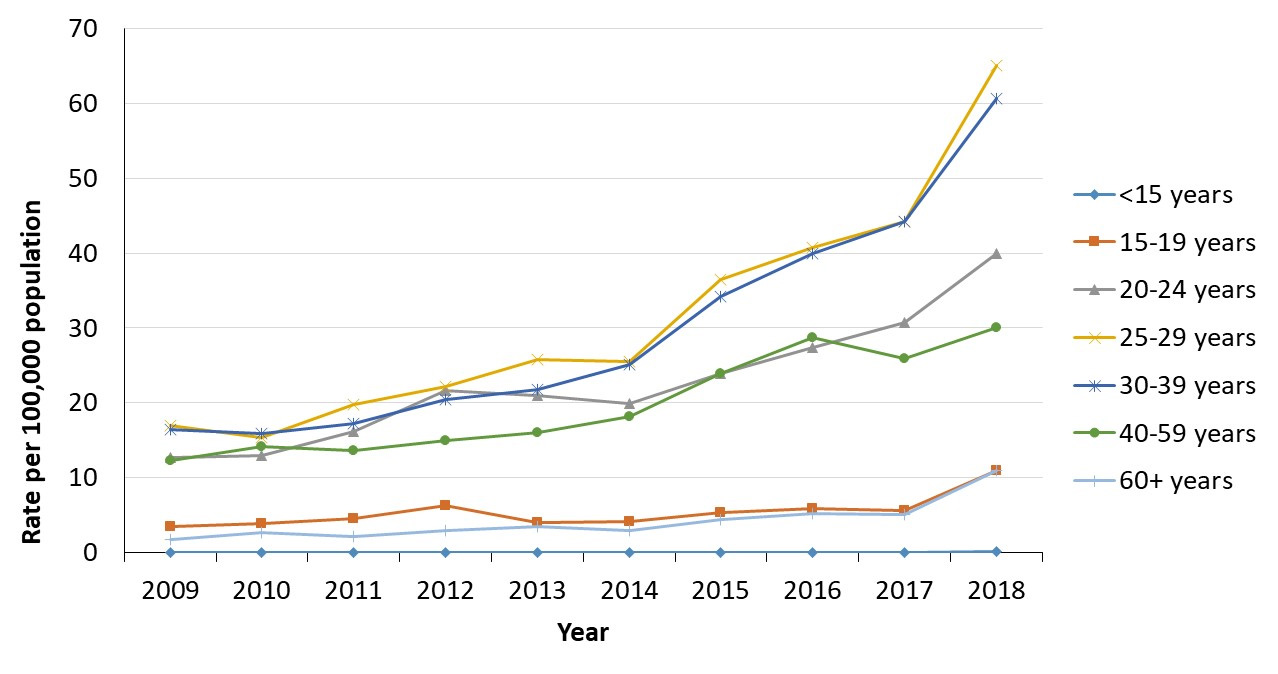

- Figure 14. Rates of reported cases of infectious syphilis by age group among females in Canada, 2009-2018

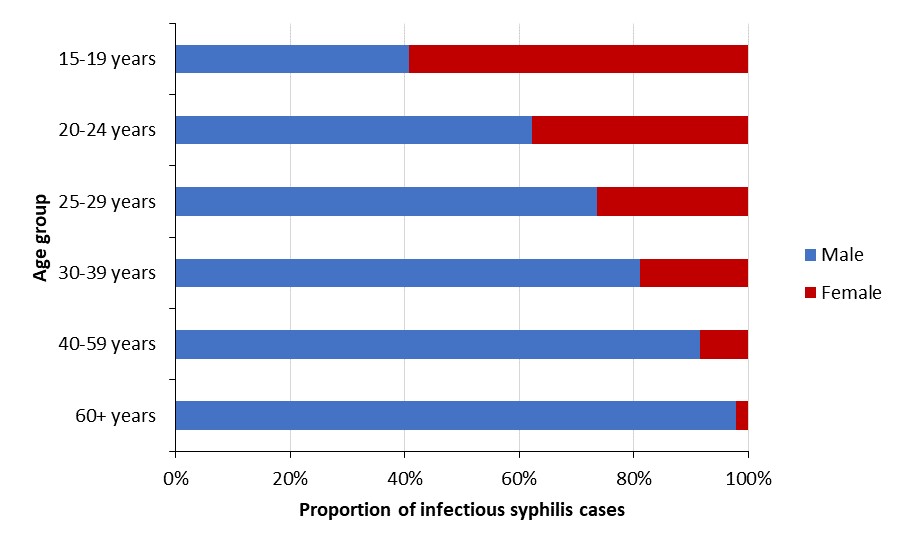

- Figure 15. Proportion of reported cases of infectious syphilis by age group and sex in Canada, 2018

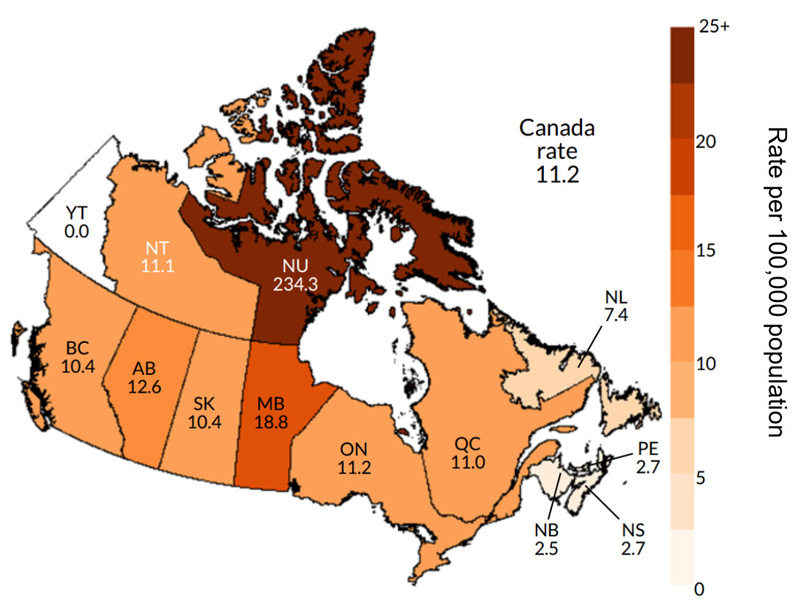

- Figure 16. Rates of reported cases of infectious syphilis by province and territory in Canada, 2017

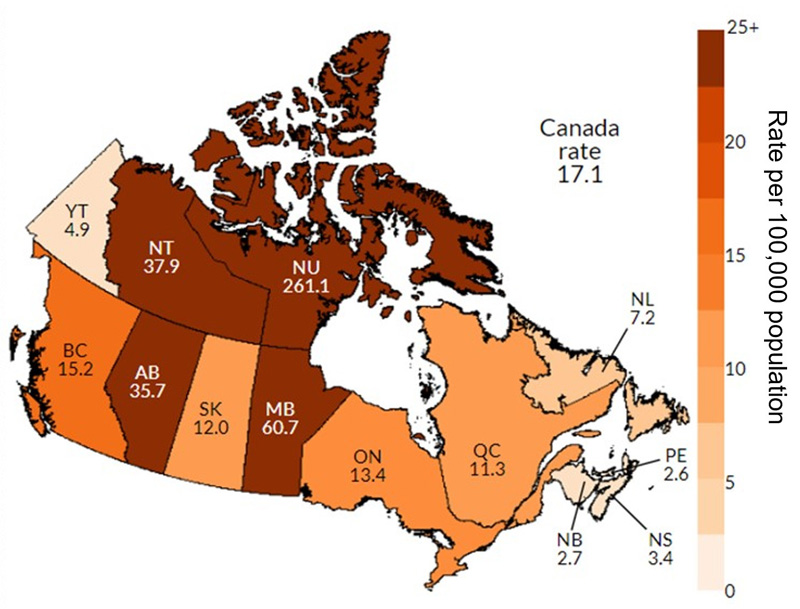

- Figure 17. Reported rates of infectious syphilis by province and territory in Canada, 2018 (preliminary data)

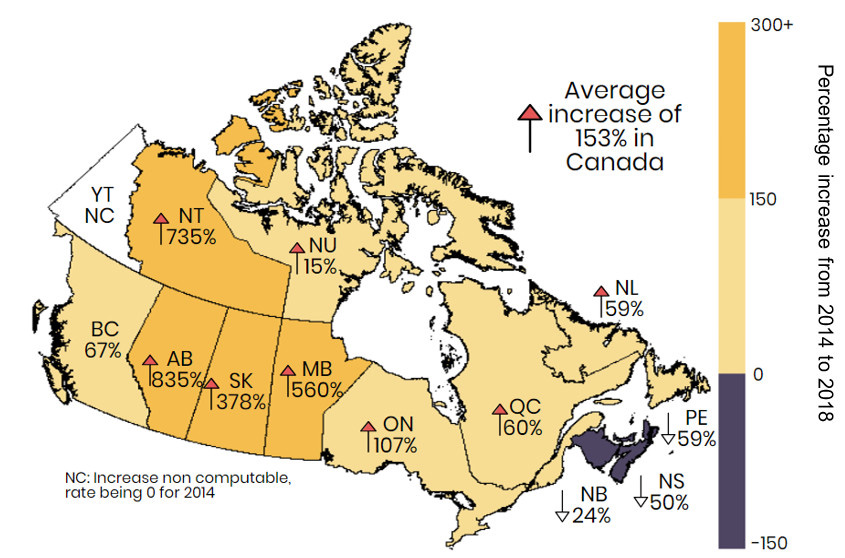

- Figure 18. Change in rates of reported cases of infectious syphilis from 2014 to 2018 by province and territory in Canada

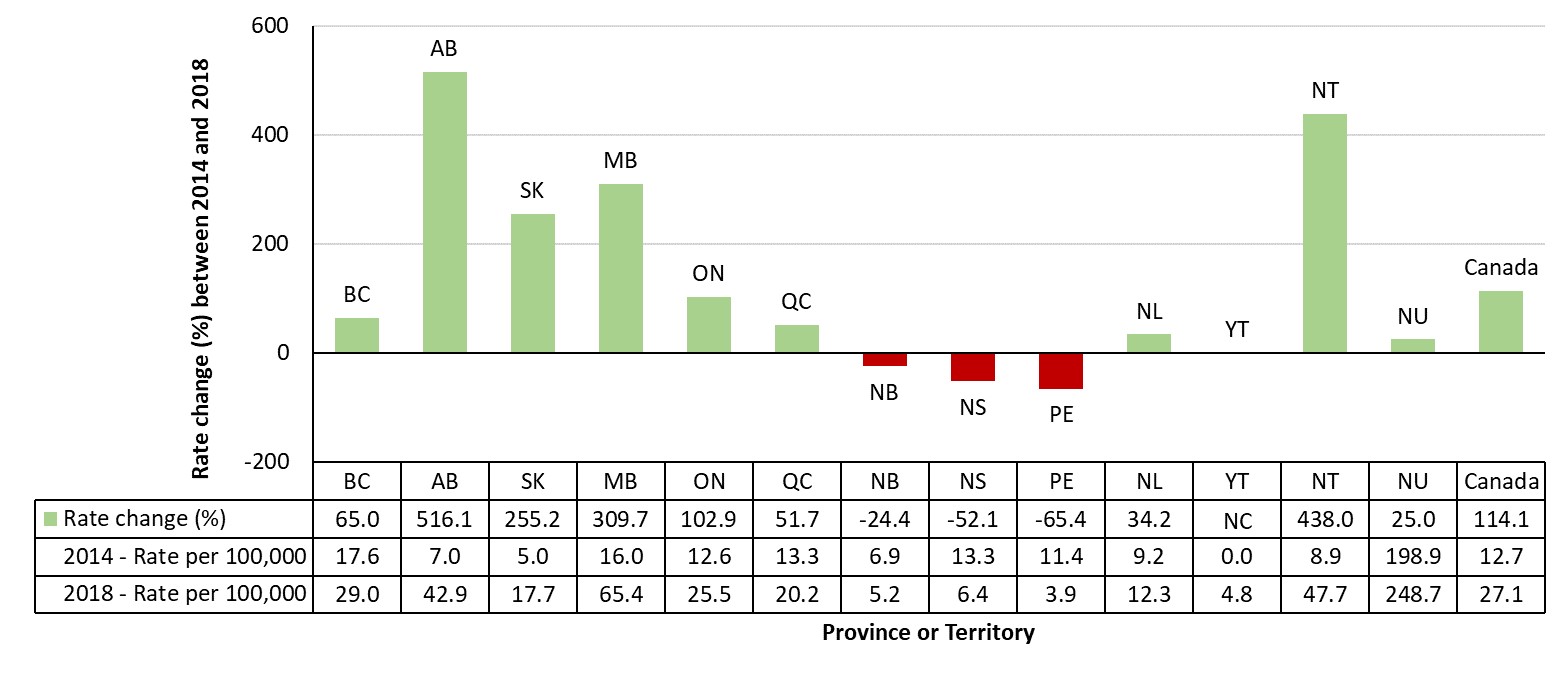

- Figure 19. Percentage change in rate of reported cases of infectious syphilis between 2014 and 2018 in males by province and territory in Canada

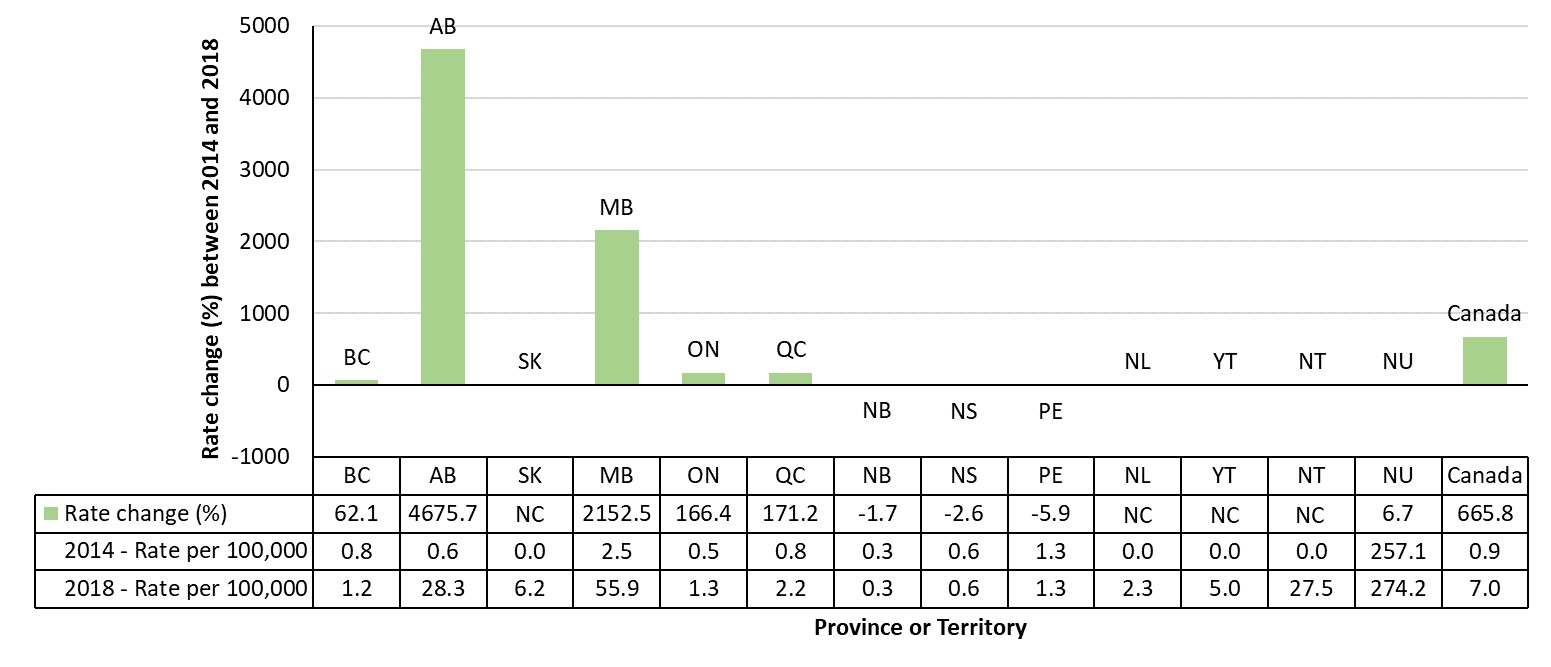

- Figure 20. Percentage change of rate of reported cases of infectious syphilis between 2014 and 2018 in females by province and territory in Canada

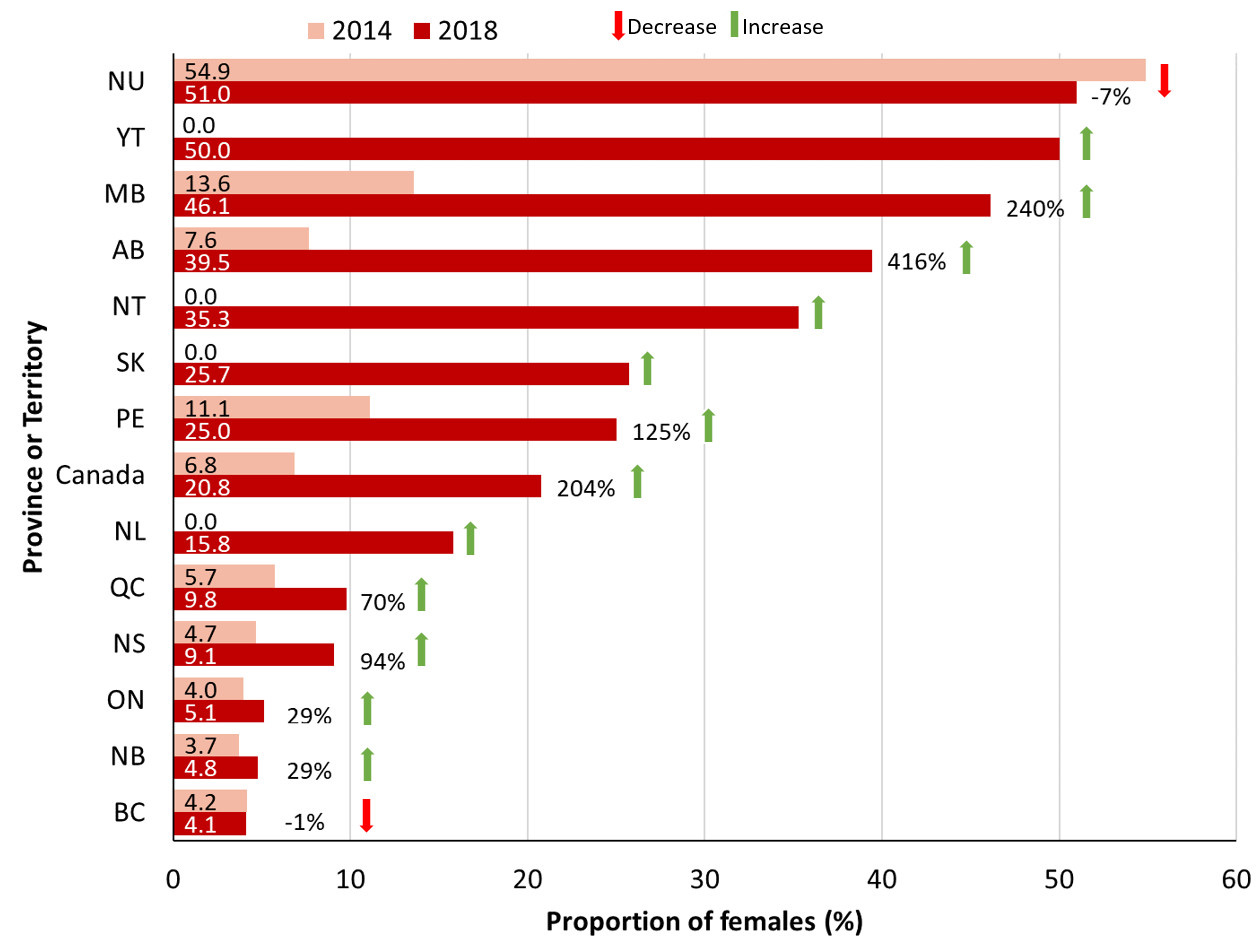

- Figure 21. Proportion of reported cases of females and percentage change by province and territory from 2014 to 2018 in Canada

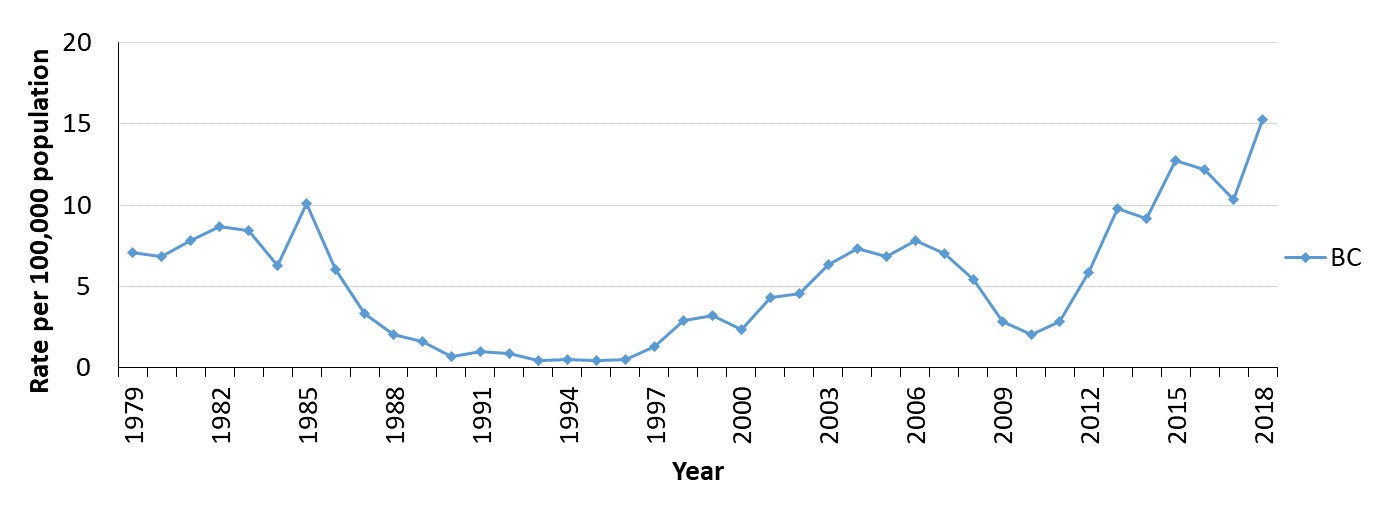

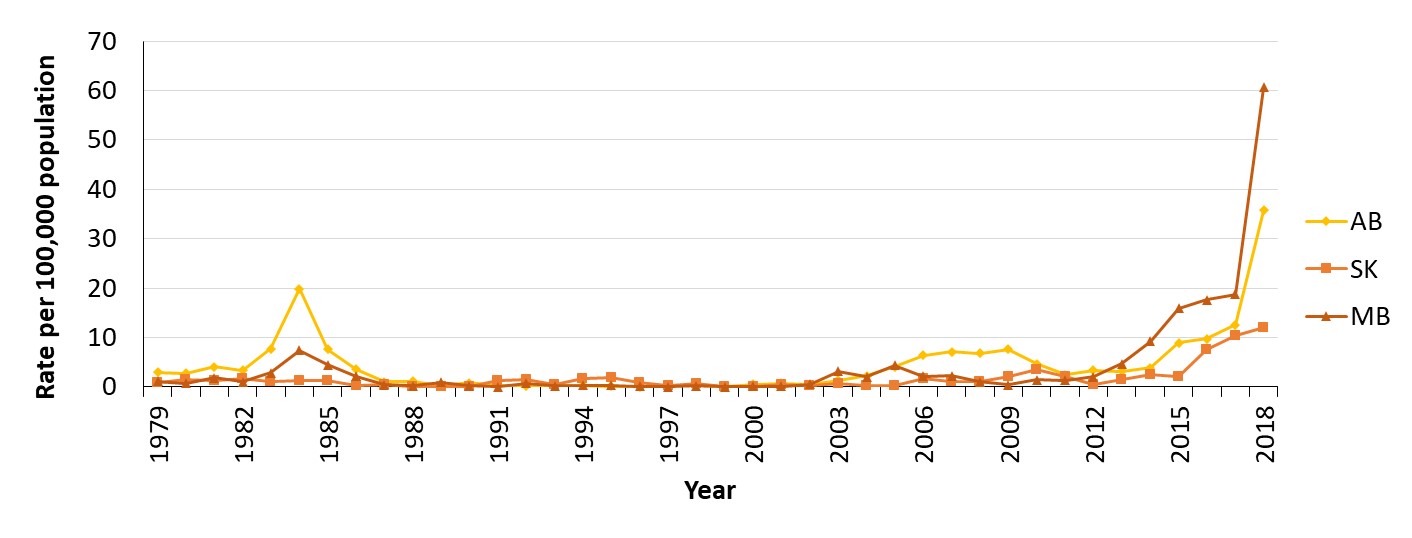

- Figure 22. Rates of reported cases of infectious syphilis cases in British Columbia, Canada, 1979-2018

- Figure 23. Rates of reported cases of infectious syphilis by sex in British Columbia, Canada, 2009-2018

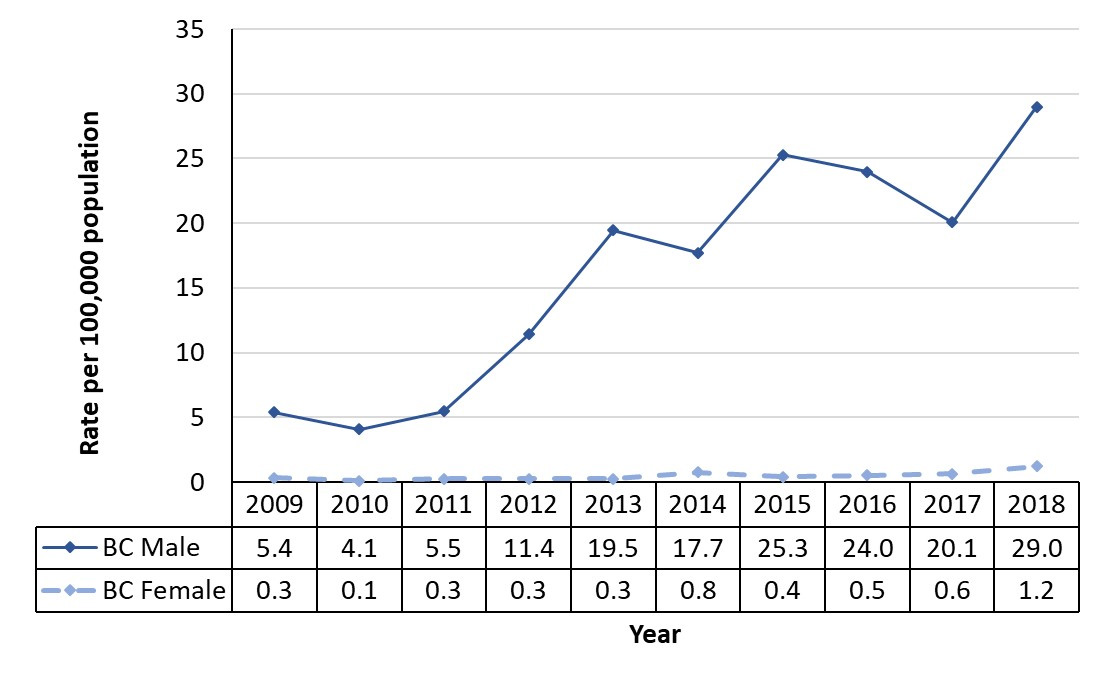

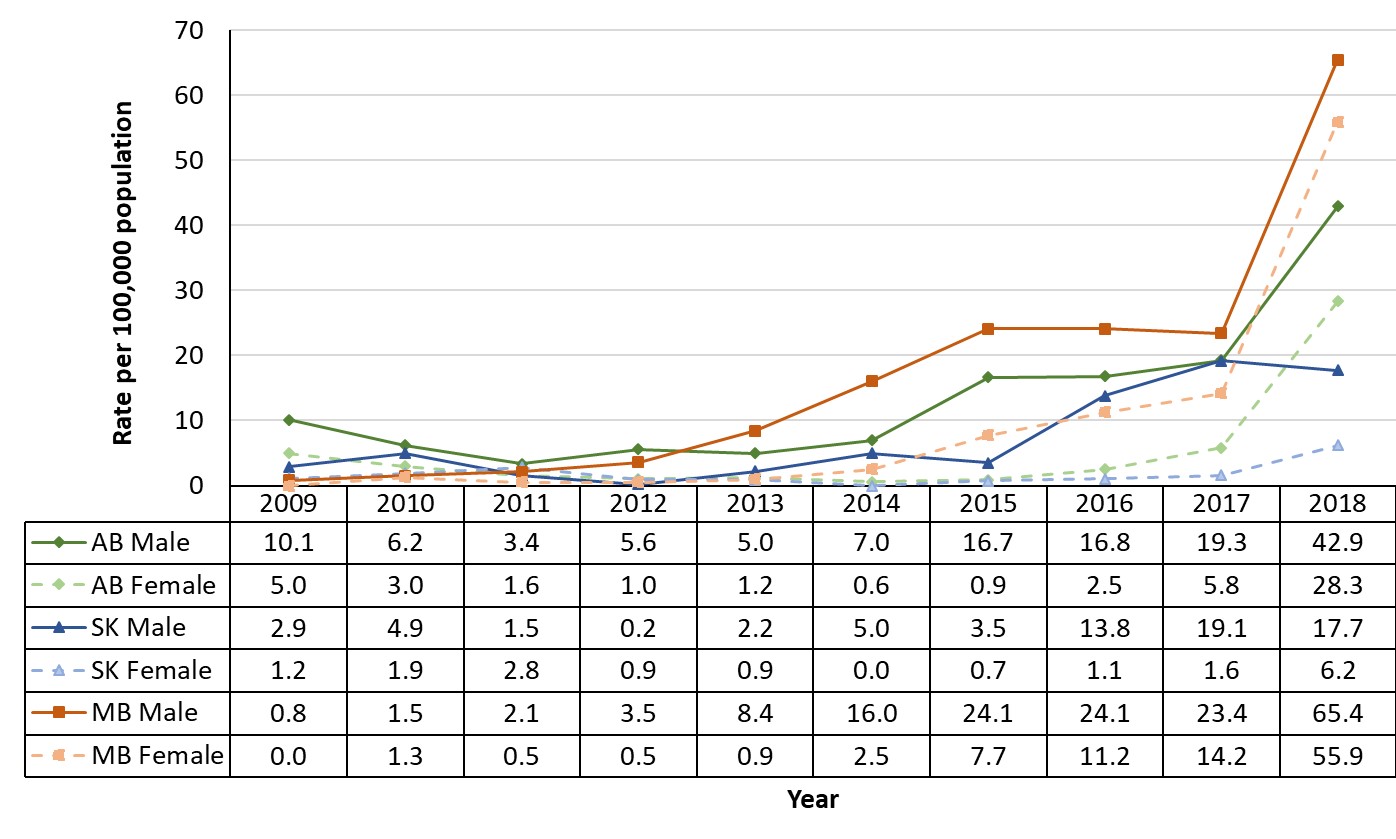

- Figure 24. Rates of reported cases of infectious syphilis in Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba, Canada, 1979-2018

- Figure 25. Rates of reported cases of infectious syphilis by sex in Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba, Canada, 2009-2018

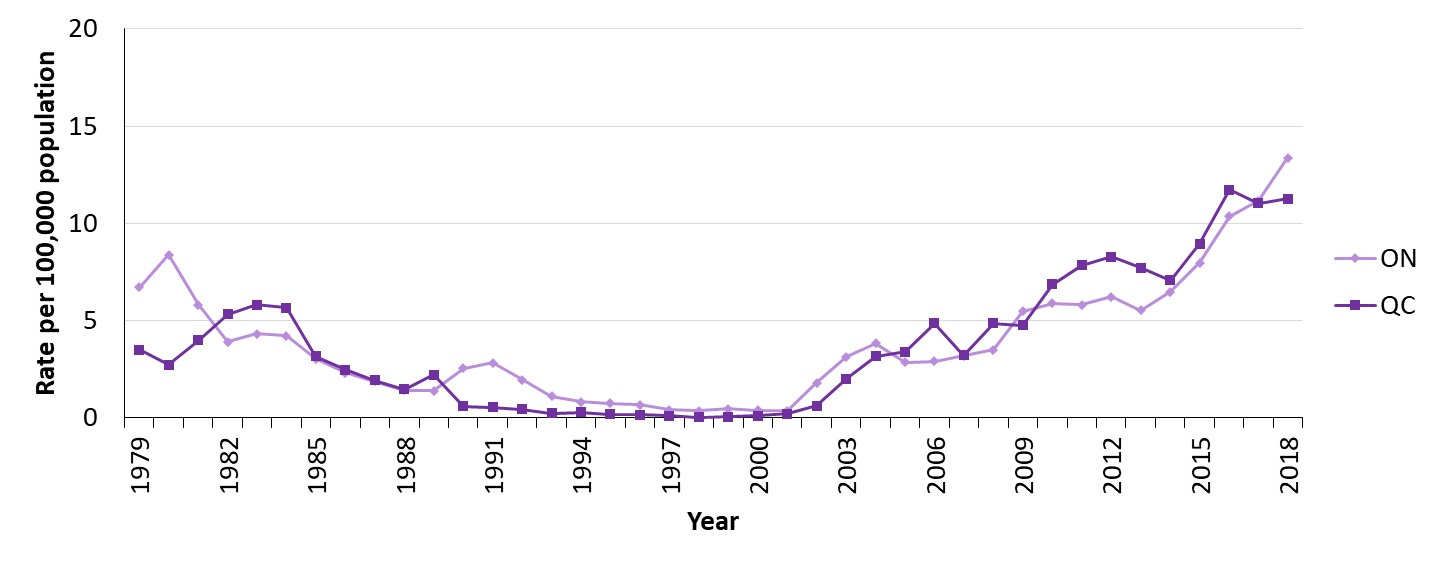

- Figure 26. Rates of reported cases of infectious syphilis in Ontario and Quebec, Canada, 1979-2018

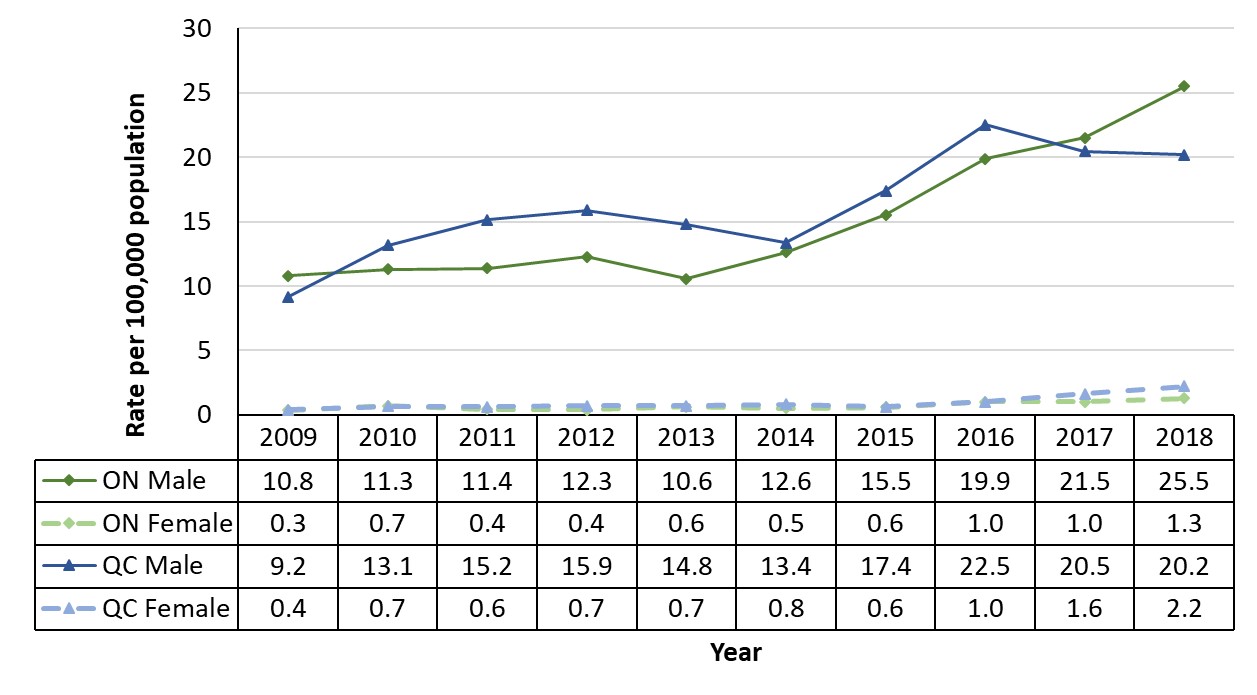

- Figure 27. Rates of reported cases of infectious syphilis by sex in Ontario and Quebec, Canada, 2009-2018

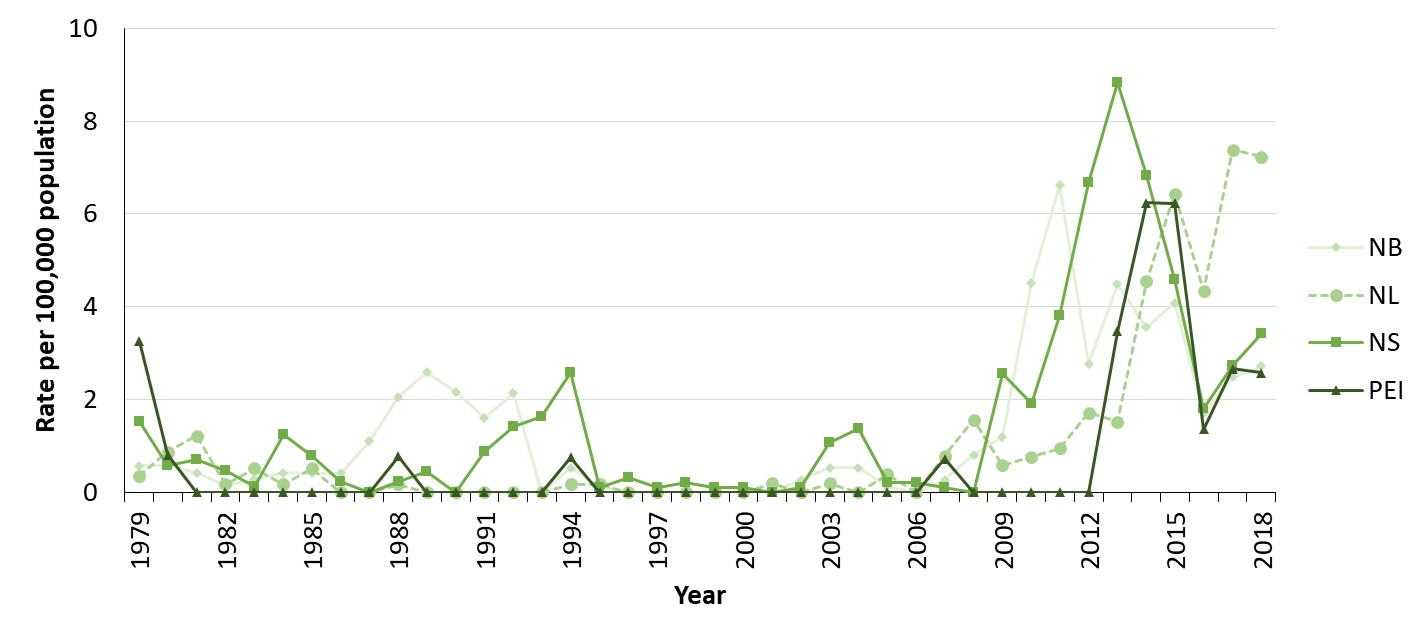

- Figure 28. Rates of reported cases of infectious syphilis in New Brunswick, Newfoundland and Labrador, Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island, Canada, 1979-2018

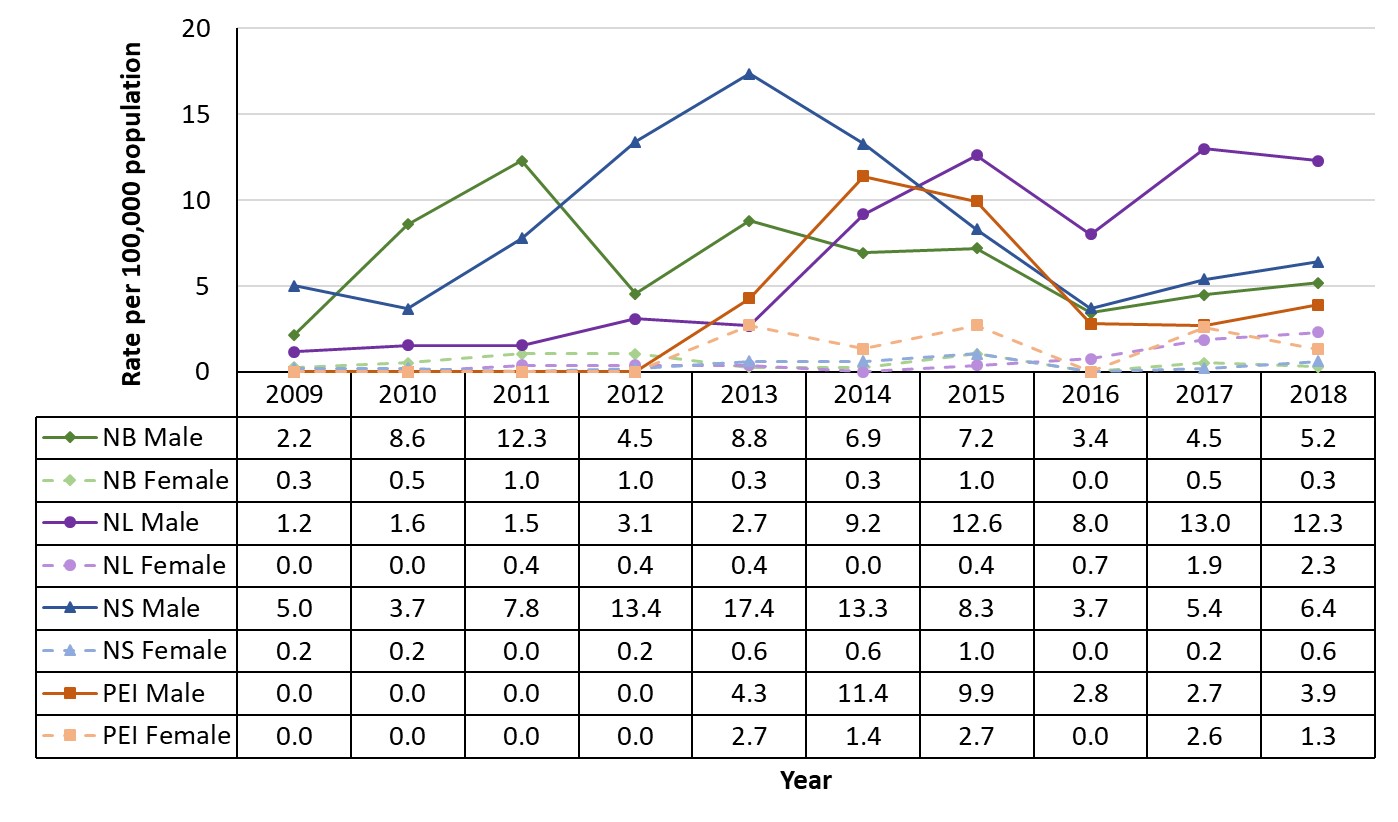

- Figure 29. Overall rates of reported cases of infectious syphilis by sex in New Brunswick, Newfoundland and Labrador, Nova Scotia, and Prince Edward Island, Canada, 2009-2018

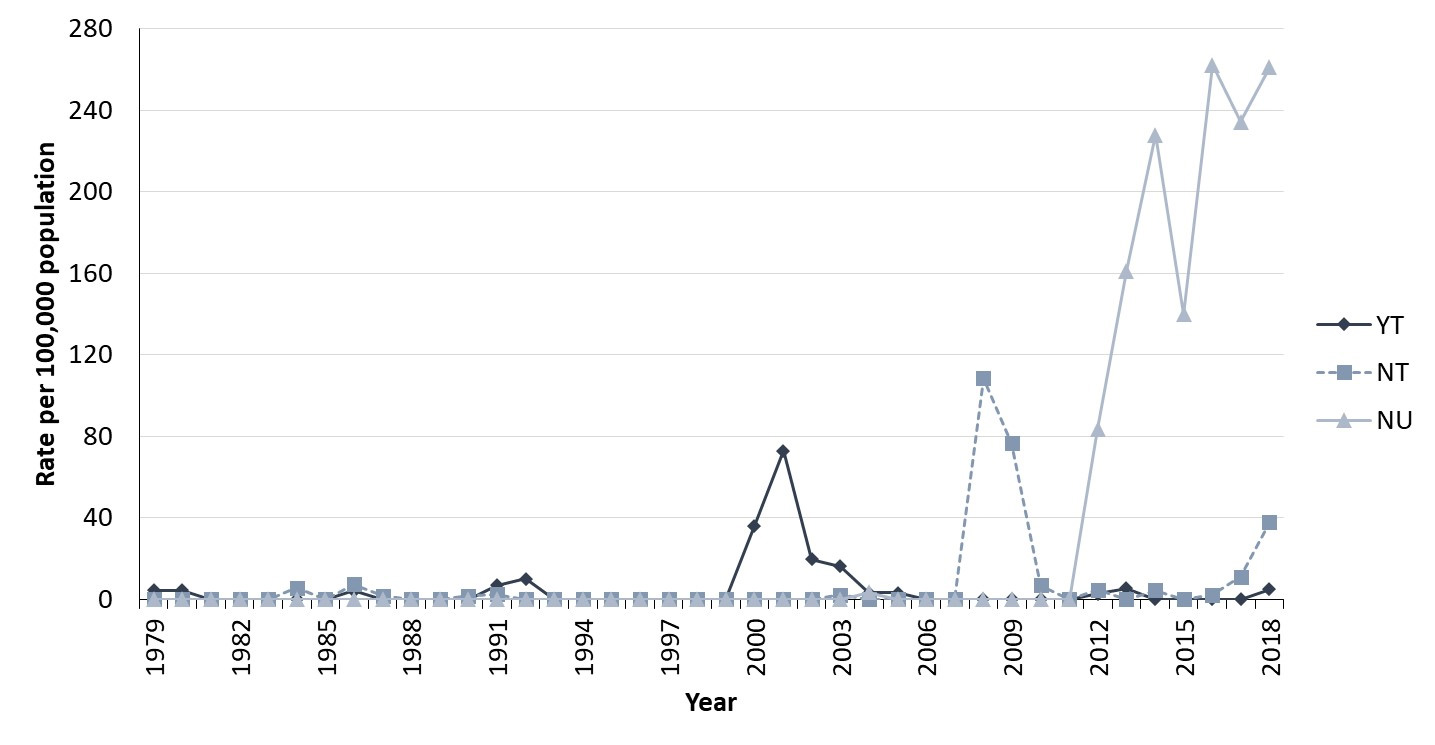

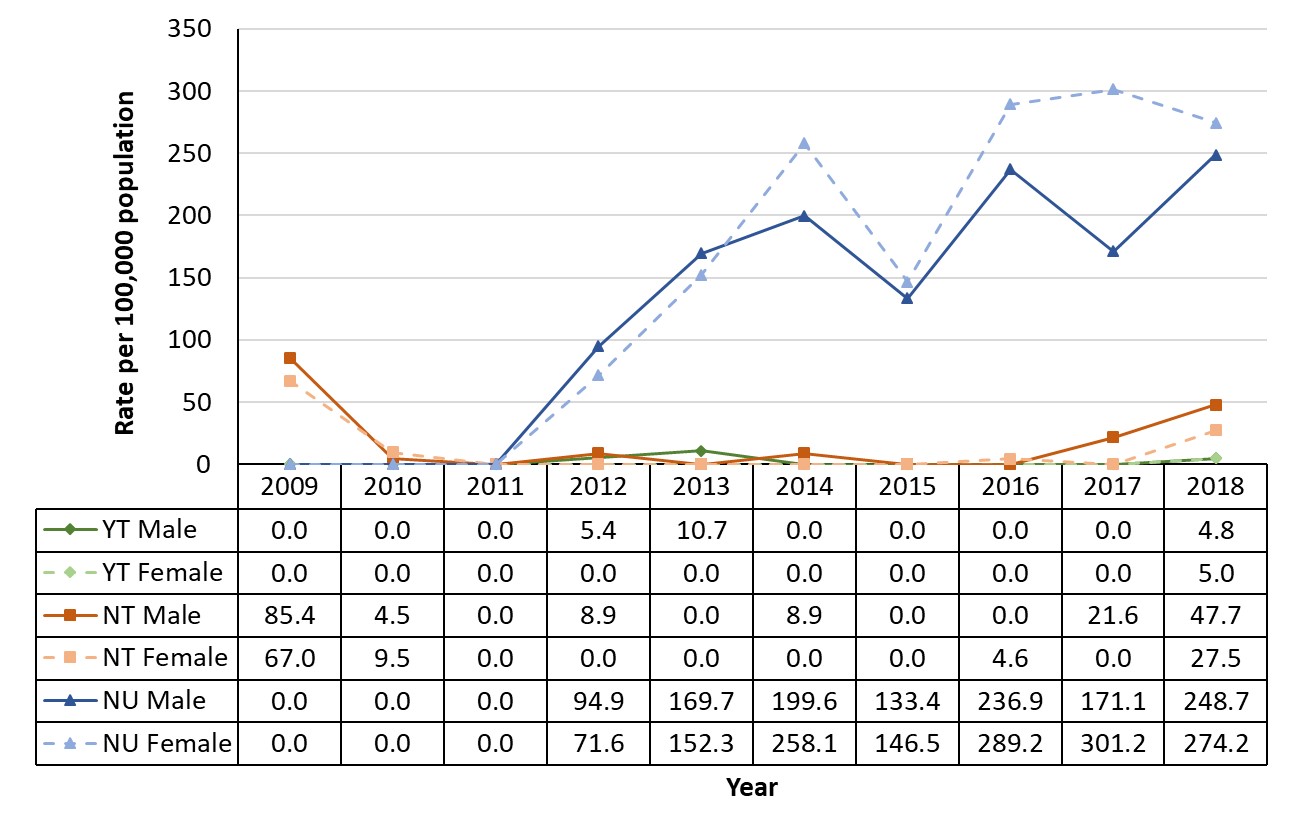

- Figure 30. Rates of reported cases of infectious syphilis in Yukon, Northwest Territories and Nunavut, Canada, 1979-2018

- Figure 31. Rates of reported cases of infectious syphilis by sex in Yukon, Northwest Territories and Nunavut, Canada, 2009-2018

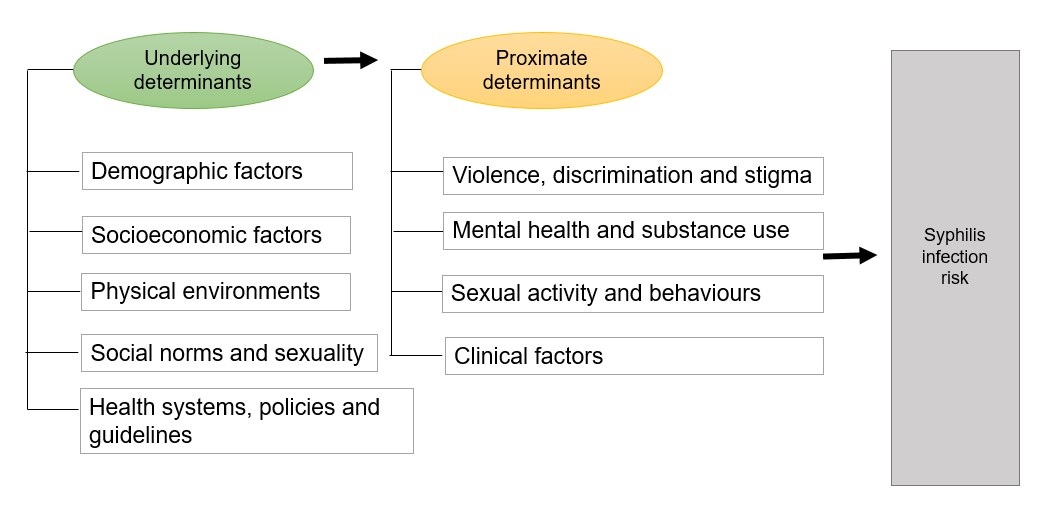

- Figure 32. Conceptual framework of syphilis infection in Canada

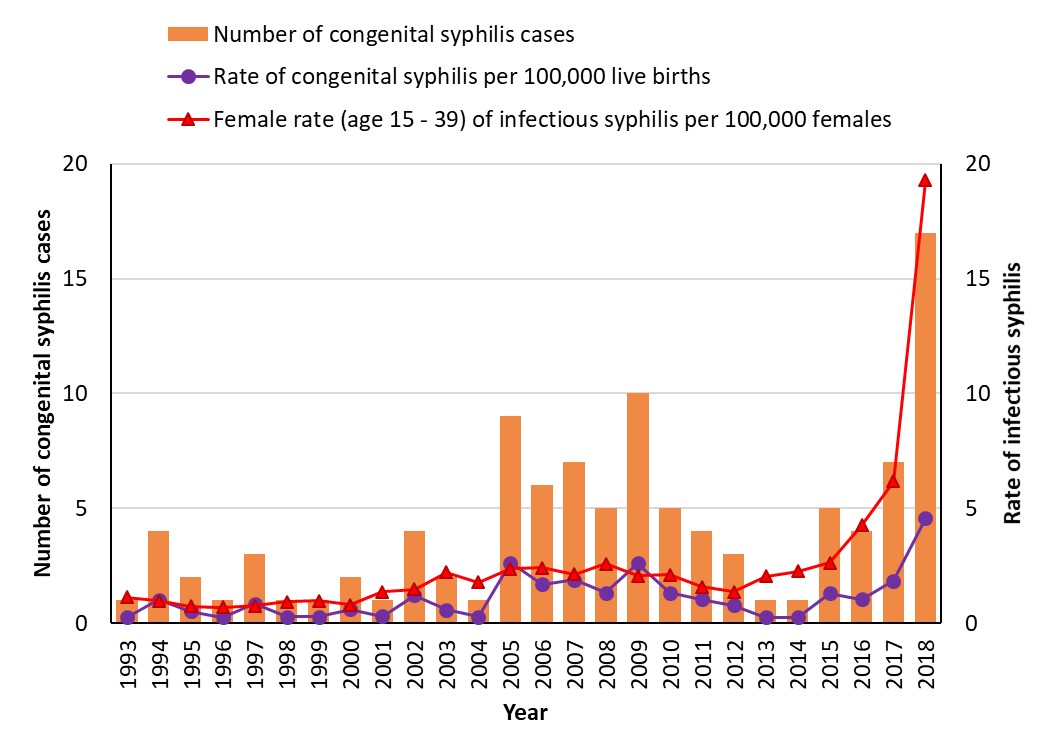

- Figure 33. Number and rates of reported cases of congenital syphilis and rates of reported cases of infectious syphilis among females of reproductive age (15 to 39 years of age), Canada, 1993-2018

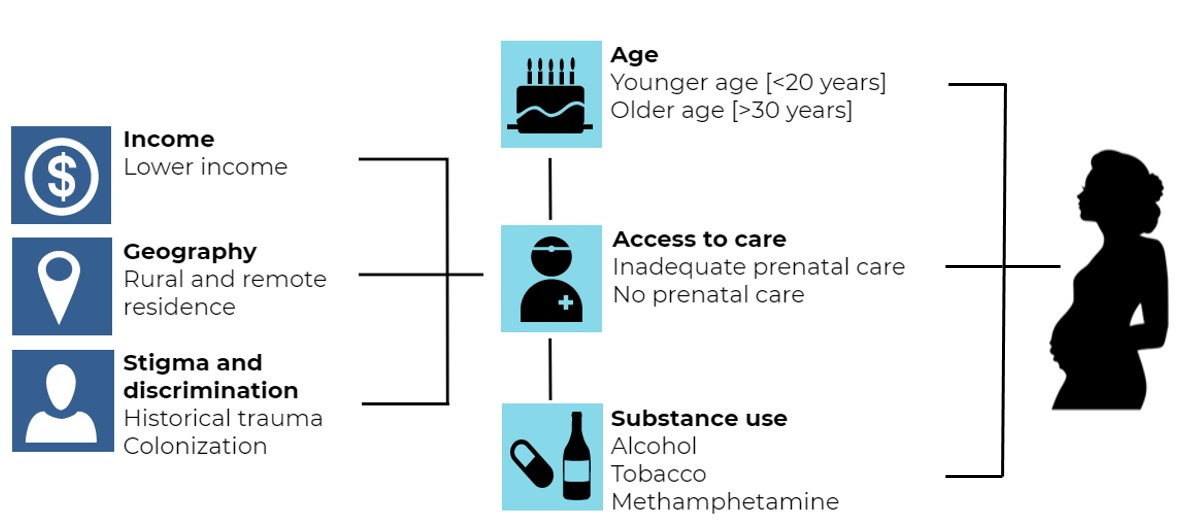

- Figure 34. Most commonly reported risk factors associated with maternal syphilis and related congenital syphilis in the Canadian literature

Table of tables

- Table 1. Provincial and territorial comparison with the national case definition for congenital syphilis

- Table 2. Provincial comparison with the national case definition of neurosyphilis and primary, secondary, early latent, late latent and tertiary syphilis

- Table 3. Comparison of syphilis reporting practices across provinces and territories over time in Canada

Abbreviations

- AB

- Alberta

- aOR

- Adjusted odds ratio

- aIRR

- Adjusted incidence rate ratio

- ART

- Antiretroviral therapy

- BC

- British Columbia

- BCCDC

- British Columbia Centre for Disease Control

- CDC

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

- CGSTI

- Canadian Guidelines for Sexually Transmitted Infections

- CI

- Confidence interval

- CIA

- Chemiluminescence immunoassays

- CNDSS

- Canadian Notifiable Disease Surveillance System

- CSF

- Cerebrospinal fluid

- CPHA

- Canadian Public Health Association

- DBS

- Dried blood spot [testing]

- DFA-TP

- Direct fluorescent antibody test for T. pallidum

- DNA

- Deoxyribonucleic acid

- ECDC

- European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control

- EIA

- Enzyme immunoassay (Treponemal screening test)

- EMIS

- The European Men-Who-Have-Sex-With-Men Internet Survey

- EU

- European Union

- FTA-ABS

- Fluorescent treponemal antibody absorbed test (treponemal screening test)

- gbMSM

- Gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men

- GHB

- Gamma-hydroxybutyrate

- HAV

- Hepatitis A virus

- HBV

- Hepatitis B virus

- HCV

- Hepatitis C virus

- HIV

- Human immunodeficiency virus

- HPV

- Human papilloma virus

- IHC

- Immunohistochemistry

- IM

- Intramuscular

- LA

- Long acting

- LIA

- Line immunoassay

- MB

- Manitoba

- MBIA

- Microbead immunoassay

- MLST

- Multilocus sequence typing

- NAT

- Nucleic acid test

- NAAT

- Nucleic acid amplification testing

- NB

- New Brunswick

- NCCID

- National Collaborating Centre for Infectious Diseases

- NL

- Newfoundland and Labrador

- NS

- Nova Scotia

- NT

- Northwest Territories

- NU

- Nunavut

- OECD

- Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development

- ON

- Ontario

- OR

- Odds ratio

- PCR

- Polymerase chain reaction

- PE

- Prince Edward Island

- PEP

- Post-exposure prophylaxis

- PHAC

- Public Health Agency of Canada

- POC

- Point-of-care [testing]

- Pap

- Papanicolaou [test]

- PT

- Provinces/Territories

- PrEP

- Pre-exposure prophylaxis

- QC

- Quebec

- RNA

- Ribonucleic acid

- RPR

- Rapid plasma reagin test (non-treponemal screening test)

- rRNA

- Ribosomal ribonucleic acid

- RSSS

- Reverse sequence screening for syphilis

- SIECCAN

- Sex Information and Education Council of Canada

- SMS

- Short message service [text messaging]

- SOICC

- Syphilis Outbreak Investigation Coordination Committee

- ST

- Sequence type

- STBBI

- Sexually transmitted blood-borne infections

- STI

- Sexually transmitted infection

- SK

- Saskatchewan

- TP-PA

- T. pallidum particle agglutination test (treponemal screening test)

- UK

- United Kingdom

- US

- United States [of America]

- VDRL

- Venereal disease research laboratory test (non-treponemal screening test)

- YT

- Yukon

- WHO

- World Health Organization

Executive summary

This report provides information on syphilis to public health professionals, clinicians and decision-makers.

The report is organized around six thematic areas:

- Syphilis: natural history, testing and treatment

- Burden of syphilis and co-infections

- Epidemiological trends of syphilis in Canada, 2009-2018

- Determinants and risk factors of syphilis in Canada

- Congenital syphilis: trends, determinants and response

- Interventions and policy for syphilis prevention and control

The first two thematic areas are addressed by summarizing existing guidance from the Canadian Guidelines for Sexually Transmitted Infections (CGSTI) and clinical and laboratory literature. In order to describe syphilis trends in Canada, the third section uses surveillance data from the Canadian Notifiable Disease Surveillance System (CNDSS) from 1971 to 2017, along with preliminary 2018 data provided directly to PHAC by the provinces and territories. Wherever possible, Canadian trends are compared to international trends. The report also describes recent syphilis outbreaks across Canada, as well as the factors that have been associated with syphilis infection in studies conducted in Canada (Section 4). Lastly, interventions and policies proposed to support the control of syphilis in Canada are discussed in Section 5 and Section 6.

1. Syphilis: natural history, testing and treatment

Syphilis is an infection caused by the bacteria Treponema pallidum. Syphilis is primarily transmitted sexually, although blood-borne transmission is possible. If left untreated, the infection can progress through four stages: primary, secondary, latent and tertiary. Individuals can transmit the infection during the early stages of infection (primary, secondary and early latent syphilis). Chancres and unspecific symptoms, such as fever, malaise or headaches, are among the most common symptoms in the early stages. Tertiary syphilis can cause severe neurological, cardiologic and musculoskeletal manifestations. The infection can also be transmitted from a mother to her fetus/child during pregnancy or at delivery, causing congenital syphilis. Congenital syphilis can lead to stillbirth, birth defects or infant death.

Guidelines for screening vary across the provinces and territories. The CGSTI recommends screening for any individual presenting with signs and symptoms or with risk factors, such as having engaged in condomless sex. Syphilis is usually diagnosed using serological tests on blood samples. Microscopic examination or Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) can also be used to detect T. pallidum or its deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA). Syphilis is usually treated with penicillin. Resistance of T. pallidum to penicillin has not been reported.

2. Burden of syphilis and co-infections

National rates of chlamydia, gonorrhea and syphilis have been increasing, with syphilis having the highest relative rate increase of all three over 2009 to 2018. Some populations, such as gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men (gbMSM), have been more affected in the past few decades. However, over the past five years, infection rates have substantially increased in other populations including females of reproductive age. As a result, the highest number of congenital syphilis cases observed in the last 25 years in Canada (17 cases) were reported in 2018. Though syphilis is not associated with high levels of mortality in Canada, it is associated with reduced functioning, a lowered quality of life as well as psychosocial repercussions. Specific populations are affected by overlapping epidemics, such as syphilis and Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) infection, which exacerbate the burden of these infections for affected individuals and communities. Syphilis interacts with HIV to amplify the impacts of both infections, as one may lead to the acquisition of the other and intensify its progression.

3. Epidemiological trends of syphilis in Canada, 2009-2018

Following a sustained decline in the 1990s, syphilis rates began to increase in Canada once again in the early 2000s. In the past few years, rates in Canada have reached their highest point in decades. Similar trends can be found in other high-income countries, such as Australia, the European Union (EU), New Zealand, the United States (US), and the United Kingdom (UK).

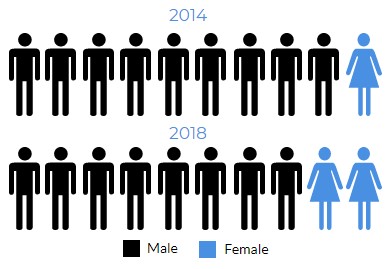

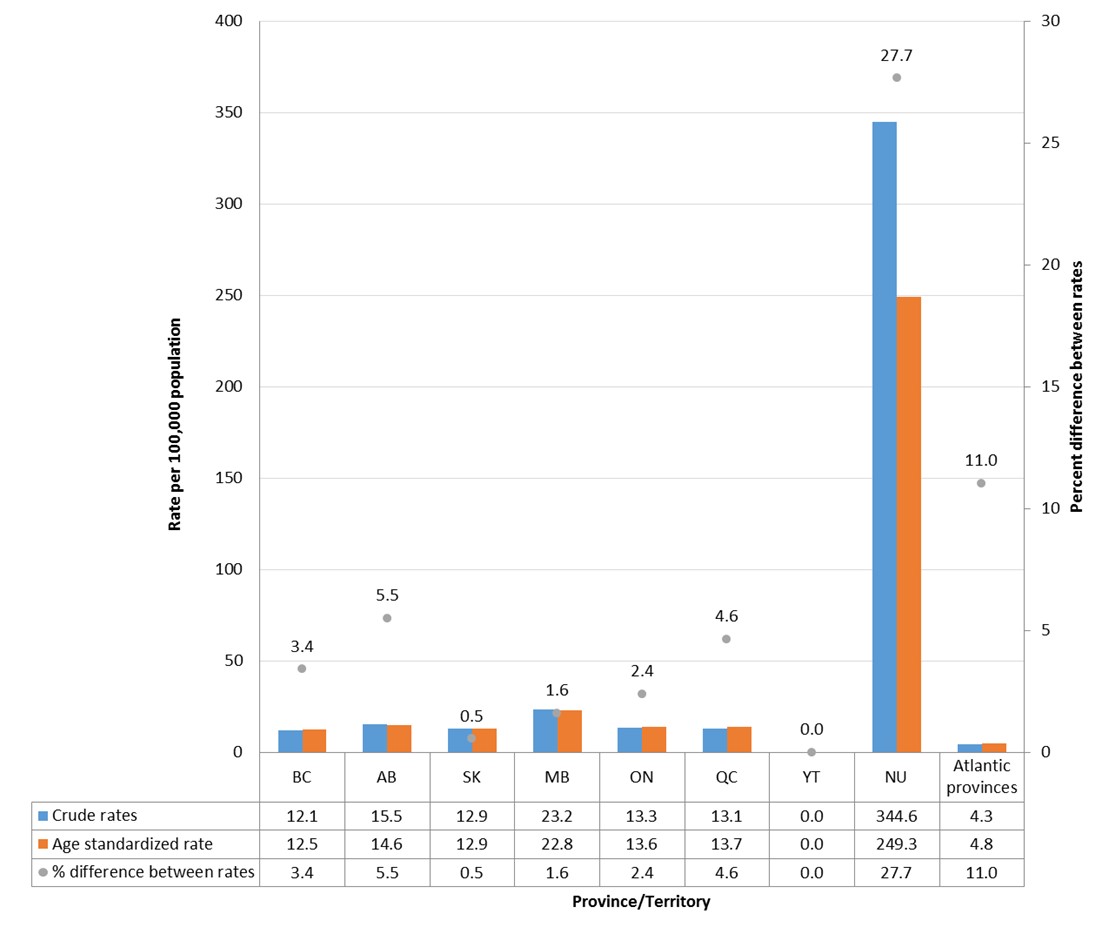

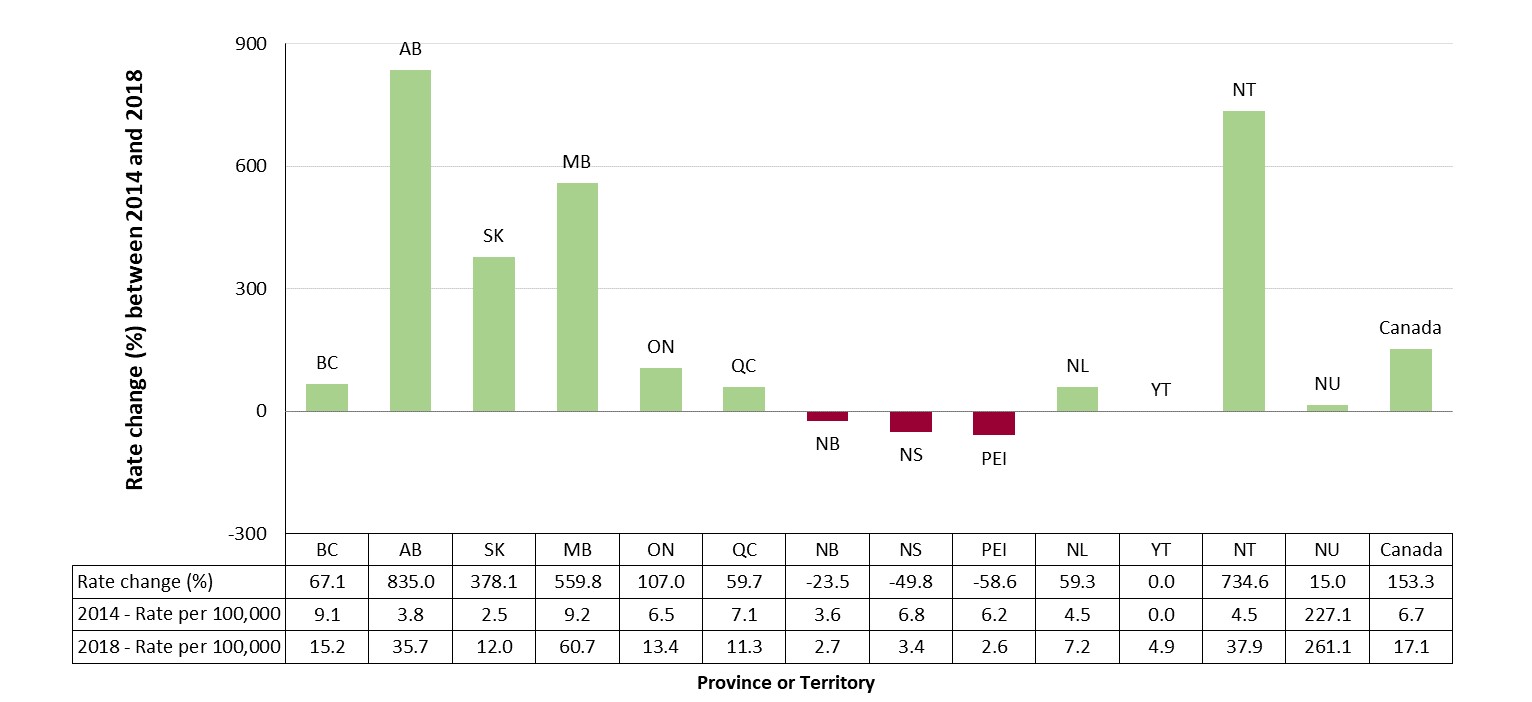

In the 1990s, rates among males and females were similar, but beginning in the 2000s, rates among males began to increase rapidly. In 2012, syphilis rates among males were 18 times higher than among females. However, in 2018, preliminary data indicate a reduction in the male-to-female ratio of new syphilis infections from 8:1 in 2017 to 4:1in 2018. In 2017, the highest rates were observed in the 25 to 29 year old age group and the 30 to 39 year old age groups. Female cases tend to be younger than male cases, as the proportion of male cases increases with age.

Between 2014 and 2018, most provinces and territories reported increases in their infectious syphilis rates. Outbreaks of syphilis have recently been reported in nine provinces and territories. The provinces and territories with the highest increases in rates over this time were Alberta (831%), Northwest Territories (550%), Manitoba (538%), and Saskatchewan (393%). Currently, the jurisdiction with the highest infectious syphilis rate is Nunavut with 261.1 cases per 100,000 population in 2018.

4. Determinants and risk factors of syphilis in Canada

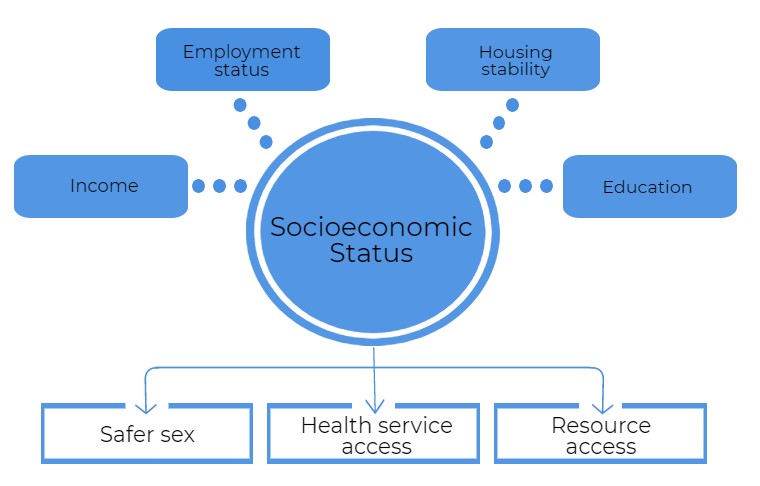

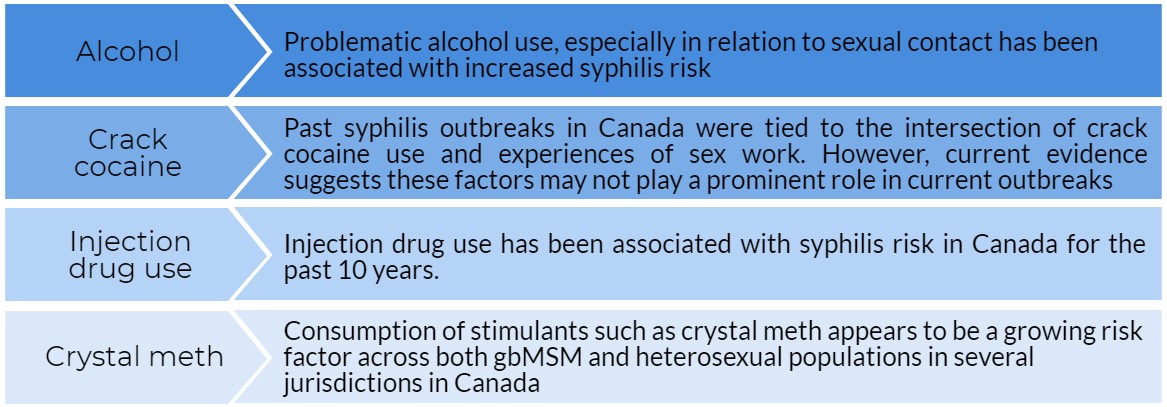

Various social determinants of health and health behaviours shape the risk of acquiring syphilis. These include a broad range of underlying factors, such as age, sex and gender, socioeconomic factors, culture, norms, and health policies and programs, which influence individual-level risk factors, such as sexual activity, substance use, experiences of violence and discrimination and access to health care and services. There is a synergistic interaction at play between the concurrent epidemics of syphilis, other sexually transmitted and blood-borne infections (STBBI) and substance use, given their common risk factors and aggravating social forces.

5. Congenital syphilis: trends, determinants and response

As rates of syphilis increase among women of reproductive age, the number of early congenital syphilis (i.e., within two years of birth) cases is also rising in Canada. From 1993 (when congenital syphilis became notifiable) to 2017, between one and ten cases of congenital syphilis cases were reported each year in Canada. In 2018, 17 cases were reported, and over 50 cases are expected for 2019. The situation is particularly worrisome in the Prairies, which have reported the bulk of congenital syphilis cases in 2018 and 2019. Moreover, several provinces and territories have recently reported their first congenital syphilis case in years.

While there have been few studies examining the risk factors for congenital syphilis, findings from those that exist have reported inadequate prenatal care as one of the main reasons for the occurrence of congenital syphilis. Pregnant women with syphilis who are not screened and treated in a timely manner are at high risk of transmitting the infection to their baby.

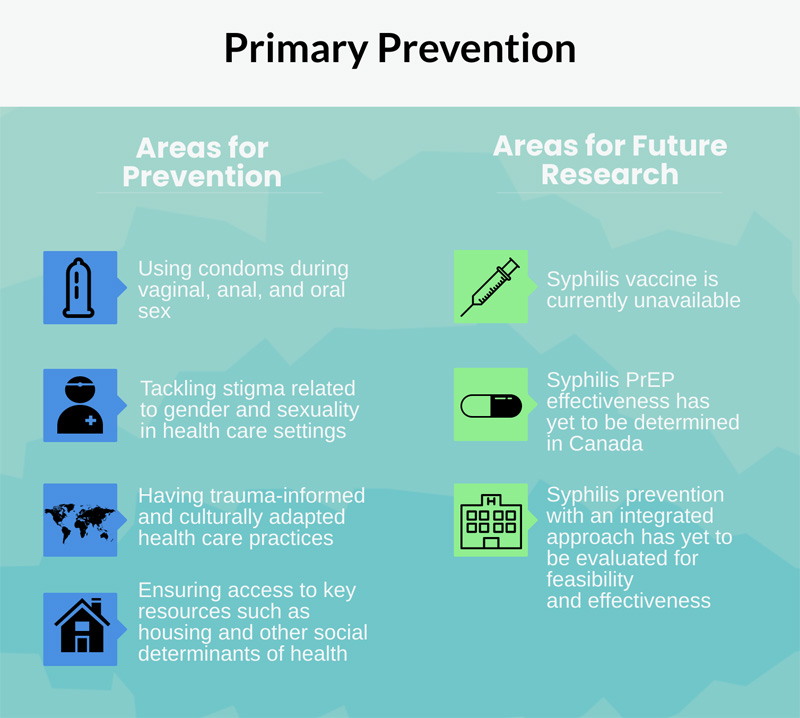

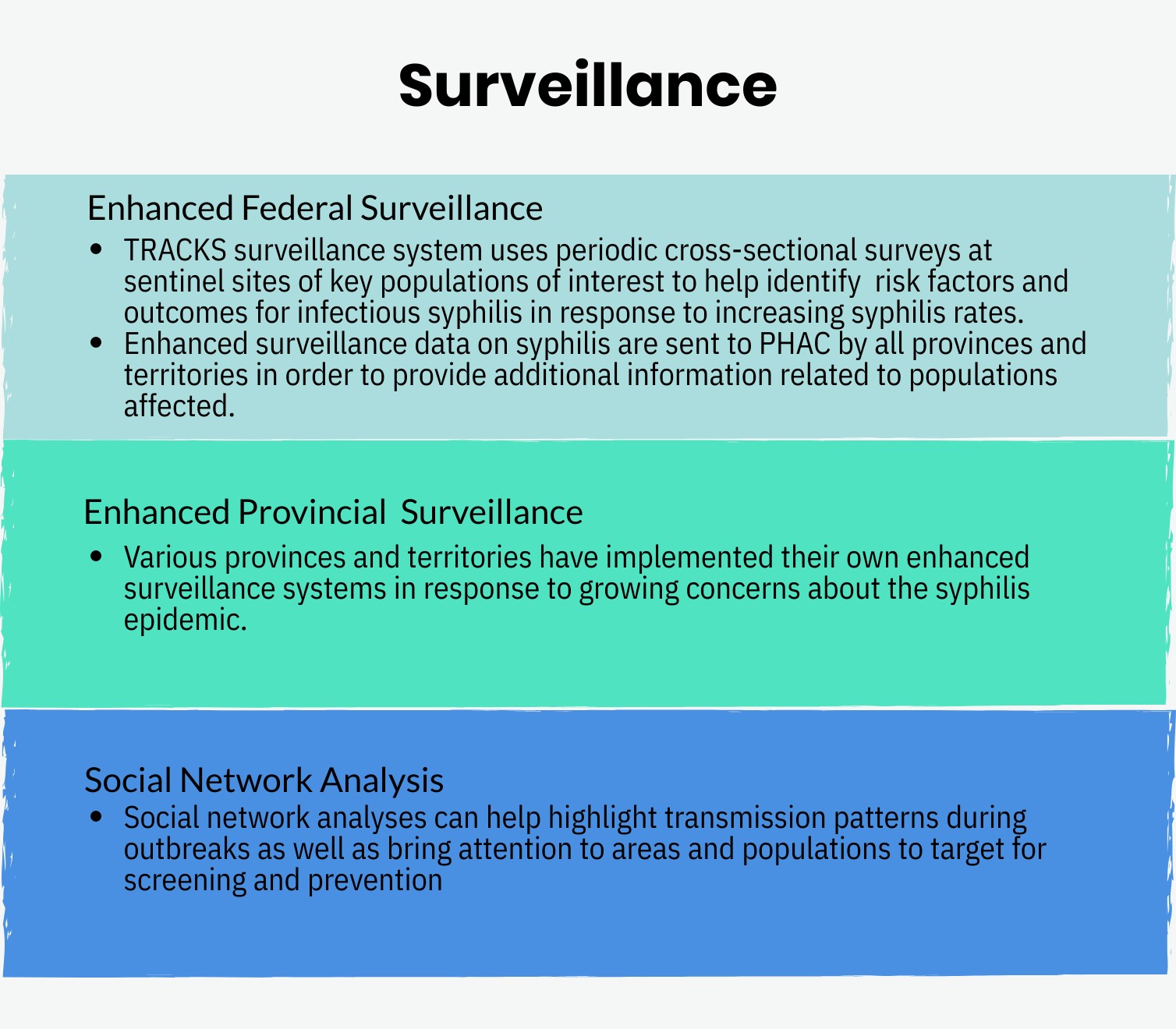

6. Interventions and policy for syphilis prevention and control

The Pan-Canadian STBBI Framework for Action identifies four pillars of action for addressing STBBI, including syphilis: prevention, testing, initiation of care and treatment, and ongoing care and support. The following section reviews the published literature on interventions and policy for syphilis prevention and control originating from Canada and abroad. Strategies to address syphilis are described according to the four pillars for action, starting with improving primary syphilis prevention to addressing underlying social determinants of health. This section also summarizes educational and clinical strategies to increase screening accessibility and uptake as well as approaches to ensure effective case management, and adapt surveillance practices to current epidemiologic case profiles. Areas for future research concerning the syphilis cascade of care, genomic analysis, and program evaluation are noted.

A note on language around sex and gender identity

Throughout the report, considerations of sex and gender are limited by data sources available. Syphilis trends and risk factors are presented according to sex (male, female), as these data are collected in most of the surveillance systems operating within Canada as well as most observational studies. Given that the multi-level determinants of syphilis infection can vary according to gender identity and experiences, discussion of influences of gender identity on how individuals perceive themselves or others, how they act, and how inequities are distributed across society have been included wherever possible throughout this report.

1. Syphilis: natural history, diagnosis and treatment

1.1 The origins of syphilis and means of transmission

Syphilis is a complex systemic illness caused by a bacterial infection. Specifically, it is caused by the spirochete bacterium Treponema pallidum, subspecies pallidum.

The origins of syphilis are unclear. Several hypotheses have been suggested, from a possible emergence in South-Western Asia around 3000 BC, to navigators from the Columbus fleet having brought back the disease from the New World - where it had existed in the pre-Columbian period - to the Old World in 1493Footnote 1.

Syphilis is transmitted primarily via genital, anal, or oral sexual contactFootnote 2. Other routes of transmission, such as through kissing with exchange of saliva, blood transfusion and sharing of needles, are possible, but rareFootnote 3. Congenital syphilis occurs mainly via vertical transmission during pregnancy, although transmission from mother to child can also happen due to contact with an active lesion at the time of deliveryFootnote 1. Transplacental transmission can occur as early as nine weeks of gestation and the remainder of the pregnancyFootnote 4. Syphilis in pregnancy can cause miscarriage, stillbirth or neonatal death. In 2012, syphilis resulted in 350,000 adverse pregnancy outcomes globally, including 143,000 early fetal deaths and stillbirths and 62,000 neonatal deathsFootnote 5.

In Canada, syphilis has been a notifiable disease since 1924, and congenital syphilis has been notifiable since 1993Footnote 6. However, reporting has been heterogeneous across provinces and territories (PTs) over time. Furthermore, for congenital syphilis cases, only cases diagnosed in infants less than two years of age are currently reportable nationally.

1.2 Infectious syphilis staging and clinical manifestations

If left untreated, syphilis infection can progress through four stages: primary, secondary, latent (early and late) and tertiary (stage progression described in Figure 1 ). However, reinfections are possible following treatment.

Figure 1 - Text description

Infectious stages:

Exposure → Incubation: 3 weeks (range 3-90 days) → Primary syphilis: chancre, regional lymphadenopathy → Secondary incubation: 2-12 weeks after primary chancre (range 2 weeks to 6 months) - Early neurosyphilis can occur → Secondary syphilis: rash, fever, malaise, headaches, mucosal lesions, condyomata lata, lymphadenopathy, alopecia → 1 year after infection - Early neurosyphilis can occur → Early Latent syphilis: asymptomatic (≤1 year post-infection) → Pathway linked to non-infectious syphilis

Non-infectious stages:

>1 year incubation - Late neurosyphilis can occur → Late latent syphilis: asymptomatic (>1 year-post infection) → Tertiary syphilis: neurosyphilis, cardiovascular syphilis (10-20 years post-infection), gumma (15 years post-infection)

1.2.1 Primary syphilis

Primary stage syphilis usually occurs after an incubation period of three weeks, on average. However, the incubation period can last between 3 and 90 days. At this stage, a lesion (chancre) may occur as well as regional lymphadenopathy. The chancre may not be readily apparent, as it may be internal (e.g., intra-anal, oral or on the internal genital tract in females), and therefore can frequently go unnoticed. This stage of syphilis is considered infectious with an estimated risk of transmission of approximately 60% per sexual partnerFootnote 2.

1.2.2 Secondary syphilis

After a secondary incubation period of two to 12 weeks (which can last up to six months), infectious syphilis may progress to the secondary stage. Symptoms at this stage can include rashes, fever, malaise, headaches, mucosal lesions, condylomata lata (wart-like lesions), lymphadenopathy, and patchy or diffuse alopecia, signs and symptoms of meningitis, uveitis/retinitis (e.g. blurred vision, eye redness, flashes or floaters) or otic symptoms (e.g., hearing loss, tinnitus). This secondary stage is also considered infectious, with an estimated risk of approximately 60% per sexual partnerFootnote 2.

1.2.3 Latent syphilis (early, late)

Without treatment, secondary syphilis can progress to the latent stage, during which no symptoms are present. Latent syphilis infections that occur within the first year following infection are considered “early” latent syphilisFootnote 3. This stage is considered infectious because one in four cases can relapse to secondary stage manifestationsFootnote 7. An asymptomatic infection that persists over a year after the infection acquisition is considered “late” latent syphilis.

1.2.4 Neurosyphilis

At any stage of infection, Treponema pallidum can invade the central nervous system causing neurosyphilis. Neurosyphilis may be asymptomatic or may present with symptoms. Early neurosyphilis occurs within the first year of infection, and approximately 5% of cases experience symptoms, such as meningitis, cranial neuritis, ocular involvement and meningovascular diseaseFootnote 8. Neurosyphilis is considered late if its onset is more than one year after infection. At this stage, 2-5% experience general paresis and 2-9% experience tabes dorsalis (loss of coordination of movement)Footnote 8. Other signs and symptoms of neurosyphilis include ataxia, vertigo, dementia, headaches, personality changes, Argyll Robertson pupil, otic symptoms (e.g. tinnitus, hearing loss) and ocular symptoms (e.g. blurred vision, bright flashes, floating spots).

1.2.5 Tertiary syphilis

Though rare, latent infections can progress to tertiary syphilis. Tertiary infections are not infectious. At this stage, the infection can affect several organs, including the brain, nerves, eyes, heart, blood vessels, liver, bones, and joints. Tertiary syphilis can manifest as neurosyphilis (described above). It can also manifest as to cardiovascular syphilis, which occurs ten to 30 years following initial exposure and can lead to development of aortic aneurysms or regurgitation, or coronary artery ostial stenosis. Although most cases will develop within 15 years, syphilis can manifest between one and 46 years following initial exposure, and can lead to gummatous lesions (gumma) on any organ, with clinical manifestations varying based on the site involvedFootnote 3.

1.2.6 Congenital syphilis

The risk of vertical transmission varies depending on the stage of maternal syphilis, with the risk being over 50% if the pregnant woman has untreated primary or secondary syphilisFootnote 9Footnote 10. Congenital syphilis can lead to stillbirth. Early congenital syphilis occurs within the first two years of life. Manifestations can include fulminant disseminated infection, rhinitis (snuffles), mucocutaneous lesions, hepatosplenomegaly, anemia, osteochondritis and neurosyphilis. Symptom onset after two years is defined as late congenital syphilis. Symptoms include interstitial keratitis, lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, anemia, bone involvement, dental abnormalities such as Hutchinson’s teeth, and neurosyphilis.

1.2.7 Syphilis staging

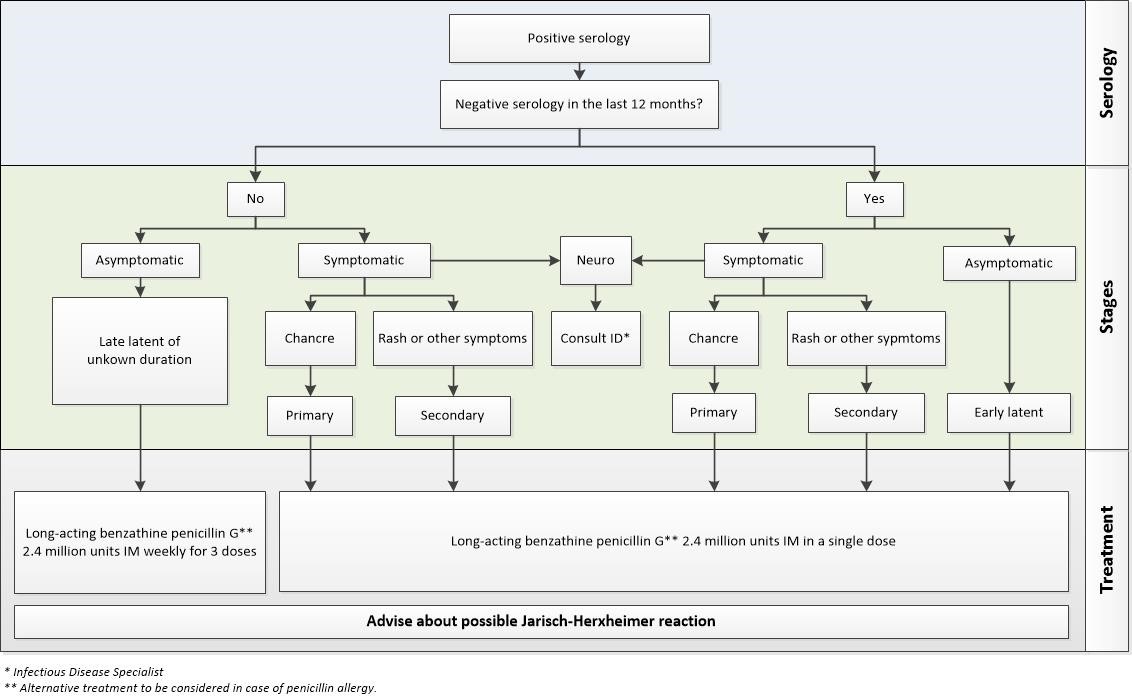

Syphilis staging can be challenging, as infection stage cannot be determined by laboratory testing alone. Patient history and clinical presentation of disease are essential to determine syphilis stage and allow proper treatment. For primary and secondary stages, positive serology and clinical manifestation are needed to stage cases, as these stages can only be distinguished by signs and symptoms. In the case of asymptomatic patients with positive serology, patient history is necessary to determine staging; those who previously tested negative in the last 12 months are most likely to be in the early latent stage of syphilis, while those without negative serology in the previous 12 months may be in the late latent stage. Neurosyphilis can manifest in early (infectious neurosyphilis) or late stages (non-infectious neurosyphilis) of syphilis infection. Similar to what was discussed above, patient history is pivotal, as only previous serology testing and the history of physical symptoms can distinguish infectious from non-infectious neurosyphilis cases. This distinction is important, as early stages and late stages will require different courses of treatment. Appendix A presents an algorithm of syphilis staging according to the CGSTI.

1.3 Syphilis screening

1.3.1 Target population for screening

The Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) guidelines recommend that any individual presenting signs or symptoms compatible with syphilis and individuals presenting with risk factors for syphilis should be screenedFootnote 3. These risk factors include:

- Having sexual contact with someone who has received a syphilis diagnosis

- Being a man who has sex with men

- Being engaged in transactional sex

- Having experienced homelessness or street involvement

- Having used injection drugs

- Reporting multiple sexual partners

- Personal history of syphilis, HIV infection or other sexually transmitted infections (STIs)

- Being born to a mother diagnosed with infectious syphilis in pregnancy

- Having lived in a country or region with a high prevalence of syphilis

- Having a sexual partner with any of the above risk factors

Guidelines for screening vary across provinces and territories. Local, provincial and territorial recommendations should be followed.

1.3.2 Screening in pregnancy

Given the rising rates of syphilis and congenital syphilis in Canada, universal screening of all pregnant women continues to be important and is the standard of care in all jurisdictions. Universal screening of pregnant women is recommended during the first trimester or at first prenatal visitFootnote 11. Repeat screening at 28-32 weeks (third trimester) and at delivery is recommended in areas with outbreaks and for women at high risk of acquiring syphilis. More frequent screening should be considered for women at high risk. It is also recommended that pregnant women with no history of prenatal care or testing be tested at delivery. Lastly, any person delivering a stillborn infant after 20 weeks gestation should be screened for syphilis.

1.3.3 Screening in immigrants to Canada

Currently, syphilis testing is mandatory for all individuals aged 15 years and older who undergo an immigration medical examFootnote 12. This medical exam is mandatory for all foreign nationals applying for permanent residency and for temporary resident applicants who intend to work in an occupation in which the protection of public health is essential (workers in the health sector field, for example)Footnote 13. Cases that are positive must document appropriate treatment according to Canadian protocol by providing a completed Syphilis Treatment Form with the immigration medical exam contentFootnote 14.

1.4 Laboratory Diagnosis of Syphilis

Pathogenic treponemal bacteria include Treponema pallidum subspecies pallidum (subsequently referred to as T. pallidum) that causes venereal syphilis, T. pallidum subspecies endemicum that causes bejel or endemic syphilis, T. pallidum subspecies pertenue that causes yaws, and T. carateum that causes pinta. Since the commonly used serological tests for the diagnosis of syphilis cannot differentiate between infection caused by T. pallidum and infections due to other pathogenic non-venereal treponemal agents, the differential diagnosis of skin lesions suspected of syphilis or other treponemal infection should therefore, include a careful clinical examination and consideration of the patient’s background history including any travel to endemic areas for non-venereal treponematosis.

Syphilis can be diagnosed using serological tests (treponemal or non-treponemal), microscopic examination or nucleic acid amplification tests (NAAT). Point-of-care testing is increasingly of interest for underserved populations, but is not yet licensed by Health Canada for use in Canada.

1.4.1 Serological diagnosis

Initial screening for syphilis can be conducted using a non-treponemal test or a treponemal test, both of which are applied on a serum sample. Once reactive, the treponemal test will most often remain so throughout the person’s life, even in the presence of treatmentFootnote 2. However, 15-25% will serorevert (non-reactive test result) if the individual is successfully treated while their infection is at the primary stageFootnote 2.

Non-treponemal antibody test

Non-treponemal tests approved by Health Canada include the Rapid Plasma Reagin (RPR) and the Venereal Disease Research Laboratory (VDRL) tests. These tests detect non-specific antibodies to a complex mixture of cardiolipin, lecithin, and cholesterol. Both tests are flocculation tests (clumping of antigen mixture by positive test sample) and therefore, are subjective tests that require experience on the part of the test operator. Positive non-treponemal tests are indicative of active infection at the primary, secondary, or latent stages of infection; and when done quantitatively, they can be used to follow successful treatment of infection by observing a drop in the antibody titreFootnote 3.

RPR is slightly more sensitive (86%) than VDRL (78%) for the detection of primary syphilis but both tests are 100% sensitive in secondary syphilisFootnote 15. RPR can only be used on serum samples, while VDRL can be used to detect antibodies in serum and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and is the only approved non-treponemal serological test to be used on CSF for the diagnosis of neurosyphilisFootnote 16. Interpretation of non-treponemal test results may be complicated by the prozone phenomenon, which occurs with very high titre samples that give negative results unless the test samples are diluted. Biological false positives, which may occur due to factors unrelated to treponemal infections, such as older age, some viral, bacterial, and parasitic infections, and some autoimmune diseases and pregnancy, may also interfere with the interpretation of non-treponemal test results.

Treponemal antibody test

Unlike non-treponemal tests, these tests use treponemal antigens to detect anti-treponemal antibodies. Since a positive treponemal antibody test result may remain positive for a very long time, treponemal antibody tests cannot be used to differentiate active infections from previous infections that have been treated in the past, nor can they be used to monitor and confirm success of treatment. There are many Health Canada approved serological tests that detect treponemal antibodies and these include amongst others, the fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption (FTA-ABS) test, Treponema pallidum particle agglutination (TP-PA) assay, various traditional enzyme immunoassays (EIAs), newer EIAs such as the chemiluminescence immunoassay (CIA) or the microbead immunoassay (MBIA), and the line immunoassay (LIA).

When the sensitivity and specificity of some of these treponemal antibody tests were compared, FTA-ABS has the lowest sensitivity in detecting both primary (78.2%) and secondary syphilis (92.8%) compared to other immunoassays (TP-PA, Trep-Sure, Inno-LIA, CIA and MBIA) that were found to be 100% sensitive in detecting secondary syphilis, while their sensitivities for primary syphilis were between 94.5% to 86.4%. The overall specificity was lowest for Trep-Sure (82.6%) and highest for TP-PA (100%), with FTA-ABS achieving a specificity of 98.0%Footnote 17. False positive treponemal tests have been reported in patients with gingivitis and periodontitis due to cross-reactive antigens present on oral spirochete organismsFootnote 18.

Algorithm of syphilis serology

Two types of serologic screening algorithms are currently used in Canada: traditional and reverse algorithmsFootnote 19. Traditionally, the serological detection of syphilis infection starts by screening with a non-treponemal antibody test. When positive, it is confirmed using a treponemal antibody test. For high risk individuals, both non-treponemal and treponemal antibody tests are done at the same time to detect possible latent infection when the non-treponemal antibody test may be negativeFootnote 20.

The reverse sequence syphilis screening (RSSS) algorithm approach uses a treponemal test to screen and a quantitative non-treponemal test to confirm the positives. With increasing sample volumes for syphilis screening and the availability of automatic high-throughput platforms (such as CIA and MBIA) for performing treponemal antibody tests, many laboratories have opted for the reverse approach screening of syphilis, using high throughput treponemal antibody tests and confirming any positive findings with a non-treponemal antibody test. Presently, most provinces and territories favour the reverse algorithmFootnote 3. In general, since the interpretation of serology results can be complex, and different algorithms may be employed across provinces and territories, consultation with public health laboratories regarding testing protocols is recommended.

When screening is done with the more sensitive treponemal test, discordant positive treponemal test results that cannot be confirmed by a non-treponemal test becomes a diagnostic and clinical issueFootnote 21. For example, in a study involving over three million test samples in a major Canadian city, it was found that 2.2% of the samples screened positive for syphilis when CIA was used vs. only 0.6% positive when screening was done by RPRFootnote 22. However, of the 2.2% that screened positive by CIA, 1.4% were RPR negative and only 0.6% of the samples having screened positive by CIA but negative by RPR were cases of early primary syphilis. These cases showed seroconversion to RPR positive, in a follow-up test sample. Therefore, under the RSSS algorithm, those who screened positive by EIA but who were RPR-negative may represent either early primary syphilis, treated past syphilis infection, latent syphilis of unknown duration, or false positive reaction. Consistent with this, in another study that examined the impact of the RSSS algorithm, an increase in the diagnosis of late latent syphilis was notedFootnote 23.

1.4.2 Other methods of detection

Microscopic examination

The method of choice to detect T. pallidum may depend on the type of specimen taken for examination. Tissue specimens taken for histological examination can be used to examine the presence of T. pallidum using either silver staining or an immunohistochemistry (IHC) reaction. The former test relies on a morphological recognition of spirochetes in tissue samples made visible by the silver nitrate deposit or impregnation around the bacteriaFootnote 24. The IHC method has enhanced sensitivity and specificity from the use of antibodies, such as monoclonal antibodies to T. pallidum and an enzyme reaction such as peroxidase reacting with an insoluble substrate to allow the antigen-antibody reaction to be visible under light microscopyFootnote 25. However, both methods are prone to potential false positives due to staining artifacts and the presence of cross-reacting bacteriaFootnote 26.

Direct observation of T. pallidum in fresh specimens, such as serous fluids from genital, skin or mucous membrane lesions of primary and secondary syphilis cases, can be carried out by dark-field microscopy. This method requires a trained microscopist to recognize the live motile spirochetes. As a result, the test has to be performed at, or near, the location of specimen collection. It is not suitable for oral and anal lesion specimens due to the presence of other spirochete organisms whose morphology is indistinguishable from T pallidum. The use of microscopic examination is now limited in Canada, with only one provincial public health laboratory still using microscopy as a mean for laboratory diagnosis of primary syphilis, due to the difficulties in maintaining the technical expertise and methodological limitations of the technique.

Another method for detection of T. pallidum is the direct fluorescent antibody test for T. pallidum (DFA-TP). This method is now almost obsolete due to lack of a reliable source of direct fluorescent anti-T. pallidum antibody.

Nucleic acid amplification test

Detection of T. pallidum nucleic acid by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) is a sensitive test capable of detecting ten to 100 copies of the target geneFootnote 27. PCR testing to detect DNA or ribonucleic acid (RNA) targets have been describedFootnote 28Footnote 29. However, there is currently no Health Canada-licensed PCR test commercially available for use in Canada. As a result, many laboratories have developed their own in-house test or adopted methods described in academic journals. In the last two decades, the use of PCR for the diagnosis of syphilis has provided some information about its optimal use. PCR is most useful for the diagnosis of primary syphilis before seroconversion occursFootnote 30Footnote 31. This method performs best in specimens taken from moist lesions in both primary and secondary syphilis. Its performance in blood specimens is only about 50%, except in neonates with congenital syphilisFootnote 32. Positive PCR results have been reported with urine and semen specimens as well as in the oral cavity of secondary syphilis cases involving men who have sex with men, even without oral lesionsFootnote 33-35. Another use of PCR is in testing the involvement of T. pallidum in unusual pathology, such as lung abscess, tonsillitis or a non-healing oral ulcer that extends to the lower lipFootnote 36-38.

1.4.3 Typing of T. Pallidum

Although various methods have been in use in the past, it appears likely that the recently proposed multi-locus sequencing typing (MLST) will become the widely adopted method of choice for the typing of T. pallidumFootnote 39. Since MLST has been used widely in the tracking of other bacterial pathogens like meningococci, pneumococci, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus and many others, clinicians and public health officials are familiar with the method and the terminology used.

As of September 2018, 40 Sequence Types (STs) of T. pallidum have been documented, and they have been reported from Europe, North America, South America, and Asia. These STs can be grouped into two clonal complexes: the SSl4-like clonal complex and the Nichols-like clonal complex. Although not part of the MLST scheme, PCR amplification and sequencing of the 23S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) gene that encodes for macrolide resistance or susceptibility can identify resistant strains as well as the type of resistance. Mutations at positions 2058 or 2059, corresponding to the 23S rRNA gene of Escherichia coli (accession number V00331), results in an A to G substitution, which has been shown to cause macrolide resistanceFootnote 40Footnote 41. The A2058G mutation causes azithromycin resistance, but not resistance to spiramycin, while the A2059G causes resistance to both antibiotics.

1.4.4 Point-of-care test for syphilis

Diagnostic testing conducted at or near the site of patient care, called point-of-care (POC) testing, can provide results to a clinician without time spent waiting for sample transport and laboratory processingFootnote 42. While the World Health Organization (WHO) studies POC tests for syphilis and other STIs as a means for control in developing countries and in resource-limited settings, their use and need in high-income countries like Canada are less definedFootnote 43Footnote 44. Nevertheless, there is much interest in the role of POC tests for STIs (including syphilis) in STI clinics, remote regions, and underserved populations, particularly during outbreak situations. Currently there are no licensed POC test kits for the diagnosis of syphilis in Canada, although access to these tests might be possible through the Special Access Programme for Medical DevicesFootnote 45. Field evaluations are currently underway to examine the diagnostic utilities of such POC tests across different settings, venues and populations who may benefit from such methods.

1.5 Syphilis Treatment

Syphilis is usually treated with penicillin, a treatment method that was established in 1943Footnote 46. A single dose (2.4 million units delivered through intra-muscular (IM) injection) of benzathine penicillin G-Long acting (LA) can render T. pallidum non-infectious within 24 hours for early syphilis infectionFootnote 47. Infection of longer duration requires repeated dosing. There are limited data supporting the efficacy of alternate antibiotics, such as doxycycline or ceftriaxone, for patients with penicillin allergies. These treatments may take longer to render a person non-infectious, so close patient follow-up is required. A more complete summary of treatment guidelines is available.Footnote 3

Syphilis is usually treated with penicillin. Resistance of T. pallidum to penicillin has not been reported.

Resistance of T. pallidum to penicillin (the drug of choice) has not been reported, however resistance to macrolide antibiotics — including azithromycin — has been reported in many parts of the world including CanadaFootnote 48. Unless the T. pallidum strain has been tested and found to be sensitive, azithromycin is not recommended for the treatment of syphilis.

1.5.1 Treatment for people living with HIV

Though the literature on syphilis treatment for people living with HIV is limited, existing studies suggest that this population should receive the same penicillin treatment as people who are HIV-negative (single dose benzathine penicillin G-LA for treatment of early syphilis infection). It should be noted, however, that some experts suggest a higher dosage (three weekly doses of 7.2 million units IM) for people living with HIVFootnote 3.

1.5.2 Treatment during pregnancy

For early syphilis cases in pregnant women, a single penicillin dose is reported to be effectiveFootnote 49. However, given the difficulty in staging cases among pregnant women and the association between pregnancy and both lower plasma penicillin levels and modified pharmacokinetics of penicillin, some experts recommend infectious cases be treated with two doses of benzathine penicillin G-LA 2.4 million units one week apart, particularly in the third trimesterFootnote 50. In general, treatment during pregnancy should be managed in collaboration with an obstetrician or maternal fetal medicine specialist.

1.5.3 Treatment of newborns (congenital syphilis)

No newborn should be discharged from hospital without confirmation that either the mother or newborn infant has undergone syphilis serology testing during pregnancy or at the time of labour and delivery and that the results will be followed up according to local protocolFootnote 11. Treatment is recommended for all neonates and children who are symptomatic. Furthermore, all infants for whom adequate follow-up cannot be ensured including those for whom the non-treponemal test yielded a titre that was at least four-fold higher than that of the birthing parent, and those for whom the treatment of the birthing parent was inadequate, unknown, did not contain penicillin, or occurred in the last month of pregnancy, should also be treatedFootnote 10. Preferred penicillin treatments vary based on the age of the child (<1 month versus ≥ 1 month of age) and presence of symptomsFootnote 10.

- Syphilis is a notifiable disease caused by a bacterium, Treponema pallidum, and is transmitted primarily through genital, anal or oral sexual contact.

- Congenital syphilis occurs via vertical transmission mainly during pregnancy and can cause miscarriage, stillbirth or infant death shortly after birth.

- If left untreated, a primary syphilis infection can progress through secondary, latent and tertiary disease stages. Out of the four stages of syphilis, three are infectious: primary, secondary and early latent syphilis.

- PHAC’s guidelines recommend that, any individual presenting signs or symptoms compatible with syphilis and any individual presenting with risk factors for syphilis be tested.

- Universal screening is recommended for pregnant women in the first trimester or at least once during pregnancy. Moreover, consideration should be given to repeat screening at 28-32 weeks of gestation and at delivery, particularly in areas experiencing outbreaks or for women at risk of syphilis acquisition.

- Syphilis is diagnosed most often using serologic tests and can be easily treated with penicillin.

2. Burden of syphilis and co-infections

2.1 Epidemiology of syphilis in Canada

Following chlamydia and gonorrhea, syphilis is the third most commonly reported notifiable STI in CanadaFootnote 51. Canada, in 1998, announced a national goal of maintaining a syphilis rate below 0.5 per 100,000 population by the year 2000. However, since the early 2000s, rates of syphilis infection have been steadily increasingFootnote 52. In recent years, many jurisdictions are experiencing a major surge in their number of syphilis cases (Section 3). Between 2008 and 2017, the rate of infectious syphilis increased nationally by 167%, the highest relative increase of all three STIsFootnote 51. In 2017, the most recent year for which pan-Canadian syphilis data have been published, the rate of infectious syphilis in Canada was 11.2 cases per 100,000 populationFootnote 51. That year, the rate was 2.4 cases per 100,000 females, and 20.0 cases per 100,000 malesFootnote 51. Though the rate is lower among females, provincial reports suggest that up to 86% of female syphilis cases are among women of childbearing age (15 to 39 years), leading to a higher risk of congenital syphilis incidenceFootnote 53. Provincial and territorial reports suggest that since 2017, rates of infectious and congenital syphilis have increased significantly, with a national rate of 17.0 in 2018, according to preliminary 2018 data (Section 5).

The risk of syphilis is not distributed evenly across the Canadian population. Certain populations, such as gbMSM, are known to experience high rates. Moreover, large increases in rates have been observed recently in other populations, especially women of reproductive ageFootnote 54. As a result of this recent trend, Canada reported its highest number of congenital syphilis cases in past 25 years in Canada in 2018 (17 cases). Section 4 of this report describes in detail social inequalities with regard to syphilis risk, highlighting the importance of considering health equity in syphilis prevention and control.

2.2 Burden of the disease on those affected

Among people diagnosed with syphilis in Canada, data on the distribution of staging is currently lacking. Most published studies do not distinguish between stages of infection in their reporting, and consistent staging data are not currently available across all provinces and territoriesFootnote 55. Studies that do detail staging indicate a broad distribution of cases across stages at diagnosis. Among 1,473 syphilis cases diagnosed between 1995 and 2005 in British Columbia, 50% were at primary or secondary stages, and 50% were early latentFootnote 56. In another study of a randomly selected set of 350 syphilis cases among gbMSM in British Columbia in 2013, 20% of cases were diagnosed at a primary stage, 25% were secondary, and 55% were early latentFootnote 57. In a Winnipeg-based study of 151 infectious syphilis cases in 2014 and 2015, 41% were primary, 35% were secondary, and 21% were early latentFootnote 58. Additionally, in an Alberta-based review of retrospective cases from 1975 to 2016, 8,874 cases of syphilis were reported, of which 51% of cases were infectious (i.e. primary, secondary or early latent), while 49% were classified as non-infectious (i.e. late latent or tertiary)Footnote 59. Of the 254 cases of neurosyphilis and tertiary syphilis identified in this review, 251 cases were neurosyphilis (52% early neurosyphilis and 46% late neurosyphilis) and three were cardiovascular syphilis.

In the same Winnipeg-based study referenced above, when comparing the distribution of stages among males and females, the authors found that although the proportions diagnosed at a primary stage were similar for both sexes (approximately 41%), female cases were diagnosed later (18% secondary and 35% early latent) than males (37% secondary and 19% early-latent)Footnote 58. Studies suggest that the higher rates of later-stage syphilis diagnosis among females may be due to the fact that primary lesions may be less visible for females than males, thus making it more difficult for females to know to seek assessment and diagnosisFootnote 2. Other reported reasons for this difference include the fact that females may be less likely than males to be screened for syphilis when another STI is suspected, and they may be more likely to seek over-the-counter treatments, which may mask STI presence and delay diagnosisFootnote 60. Furthermore, while many health clinic programs and community-based organizations have conducted considerable outreach activities among gbMSM communities to promote access to sexual health resources and services, there have been fewer efforts geared towards women. Additionally, it has been reported in existing literature that cases of congenital syphilis usually occur because of absence or delays in access to prenatal care for pregnant women (Section 5). These disparities in the targeting of sexual health outreach may also contribute to delays in syphilis diagnosis among women. Overall, the large proportion of cases diagnosed at an early-latent phase may indicate gaps in syphilis screening and knowledge in the country. Inequalities in stage distribution represent an important health equity issue.

If left untreated, syphilis can progress from primary to subsequent stages, each associated with distinct clinical burdens for those affectedFootnote 2. Available studies suggest that between 15% and 40% of untreated cases will experience complications associated with late stage syphilis, such as late neurosyphilis or tertiary syphilisFootnote 2. Late stage syphilis requires a more intensive treatment, with possible side effects and greater risk of treatment failureFootnote 2. Treatment failure is characterized by increasing or stable non-treponemal test titers at the recommended follow-up test one month after treatment.

Syphilis during pregnancy can lead to adverse outcomes for the fetus, including miscarriage, stillbirth and infant death. Although syphilis is not associated with high levels of mortality in Canada, it is associated with a reduction in functioning and poorer quality of life. A study conducted in Ontario reported that untreated syphilis was associated with the equivalent of 18 years of life lost due to reduced functioning, 94% of which was attributable to neurosyphilisFootnote 61. However, given that there may be considerable under-diagnosis and under-reporting of syphilis, the authors note that it is possible that these estimates underestimate the true number of years of life lostFootnote 61. Furthermore, beyond the physical health burden associated with syphilis infection, some studies also identify psychosocial repercussions of syphilis-related stigmaFootnote 62Footnote 63.

2.3 Risk of sexual transmission

It is understood that the transmission rate of infectious syphilis (primary, secondary, and early latent stages) per sexual partner is approximately 64% for primary and secondary syphilis64. There are few studies exploring the per-act transmission risk of syphilisFootnote 64. An American study that focused on transmission among gbMSM found that the probability of transmission is of 0.5% to 1.4% per sexual act during the primary and secondary syphilis stages, with lower probability in the early latent stage64. Lastly, though few studies have explored possible sex differences in transmission probability, experts hypothesize that as with HIV and gonorrhea, transmission probabilities may be higher from men-to-women than from women-to-menFootnote 65.

In general, the probability of transmission is dependent on the susceptibility of the sexual partner that is exposed64. Population-level risk of transmission is lower when pro-active screening occurs, cases are treated, cases’ contacts are traced and treated, and preventive strategies, such as condoms, are employedFootnote 64. These factors, as well as other strategies to reduce transmission risk, are described in Section 6 of this report.

2.4 Adverse pregnancy outcomes

As mentioned previously, the majority of female syphilis cases are among individuals of childbearing age (15 to 49 years, as defined by the WHO, although the PHAC STBBI surveillance team uses 15-39 years, in accordance with CNDSS age groups categories)Footnote 51Footnote 53.

Studies on mother-to-child syphilis transmission risk are rare. In a systematic review, transmission rates ranging from 2.3% to 40.9% have been reported, with a pooled mother-to-child transmission rate of 15.5%Footnote 66.

Among pregnant women, the risk of transmission is dependent on the stage of the syphilis infection as well as the timing of infection, diagnosis, and treatment during the pregnancy. However, evidence indicates that vertical transmission can occur at any time during pregnancyFootnote 64Footnote 67. The risk of vertical transmission is highest when syphilis is acquired near termFootnote 67. Research suggests that the risk of vertical transmission is 70% to 100% during primary and secondary stages, and 40% in the early latent phaseFootnote 3. If untreated, approximately 77% of maternal syphilis cases will result in adverse outcomes, which could include pre-term birth, stillbirth, neonatal mortality or clinical manifestations of congenital syphilisFootnote 64Footnote 68. Risks of adverse outcomes are higher compared to uninfected pregnancies, even after treatmentFootnote 69. As adverse pregnancy outcomes cause physical and psychological burdens both for the parent and the child, maternal syphilis and congenital syphilis are of significant public health concern.

2.5 Co-infections and syndemics

In recent years, the incidence of STIs has been increasing both in Canada and internationally (Figure 2 and Figure 5).

Figure 2 - Text description

This graph displays the percent change in chlamydia, gonorrhea, infectious syphilis, and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) rates relative to the reference year of 2008, between 2008 and 2017 in Canada. The horizontal axis shows the calendar years from 2008 to 2017. The vertical axis shows the percent change of rates of chlamydia, gonorrhea, infectious syphilis, and HIV.

| Year | Percent change relative to the reference year of 2008 (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chlamydia | Gonorrhea | Infectious Syphilis | HIV | |

| 2008 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 2009 | 4% | -13% | 12% | -18% |

| 2010 | 12% | -12% | 19% | -13% |

| 2011 | 19% | -8% | 22% | -15% |

| 2012 | 22% | -1% | 41% | -24% |

| 2013 | 21% | 7% | 51% | -25% |

| 2014 | 24% | 21% | 62% | -26% |

| 2015 | 31% | 46% | 114% | -25% |

| 2016 | 35% | 73% | 156% | -17% |

| 2017 | 39% | 109% | 167% | -16% |

Source: Public Health Agency of Canada (2019). Canadian Notifiable Disease Surveillance System.

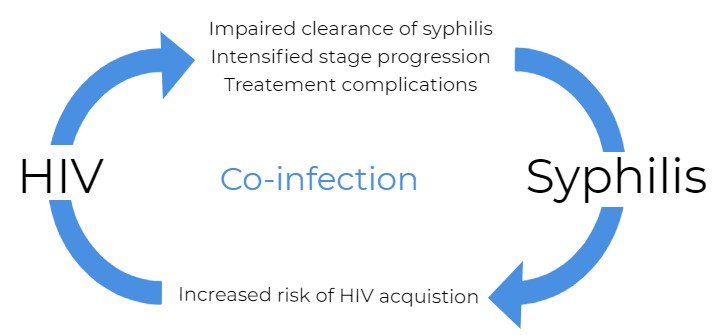

There is a trend with regard to co-infection of syphilis with HIV. The current epidemics of syphilis and other STIs have been described as a syndemic, given their concurrence (co-infections are common), interactions between these infections, associated health consequences, and shared underlying determinants (Figure 3)Footnote 62Footnote 70Footnote 71. National surveillance data do not track co-infections, but existing Canadian studies have reported the prevalence of syphilis among HIV-positive individuals to be around 8% to 11%Footnote 72Footnote 73.

Syphilis increases the risk of acquisition and transmission of HIV in several waysFootnote 74. First, syphilitic chancres provide an entry portal for the HIV virusFootnote 75. Secondly, the bacterium causing the syphilis infection, T. pallidum, has been observed to increase the expression of the CCR5 chemokine receptor—one of the principal receptors for macrophage-tropic viruses, such as HIV. This leads to a higher likelihood of HIV transmissionFootnote 75.

Figure 3 - Text description

Factors contributing to the HIV-syphilis syndemic:

- Biological interaction (syphilis influences HIV in the following ways: chancres facilitate HIV transmission (entry point), T. pallidum induces expression of CCR5 on macrophages, and syphilis decreases CD4 counts; HIV influences syphilis in the following ways: HIV impairs clearing of syphilis, complicates syphilis testing, diagnosis and treatment, and enhances neurosyphilis complications)

- There are common risk factors such as inconsistent condom use, multiple and/or anonymous sexual partners, substance use and mental health issues

- There are also underlying social factors which include malnutrition, poverty, stigma, access to healthcare and street/domestic violence

Adapted from Jiang et al. (2017), Yu et al. (2018), Singer and Clair (2003), Singer et al. (2006), Lang et al. (2018), Remis et al. (2016), Solomon et al. (2016) and Karp G et al. (2009)

Adapted from Jiang et al. (2017)Footnote 70, Yu et al. (2018)Footnote 62, Singer and Clair (2003)Footnote 71, Singer et al. (2006)Footnote 76, Lang et al. (2018)Footnote 72, Remis et al. (2016)Footnote 73, Solomon et al. (2016)Footnote 74 and Karp G et al. (2009)Footnote 75.

In turn, people living with HIV are eight times more likely to be infected with syphilis compared to the general populationFootnote 75. Several factors can explain the association between HIV and syphilis infection. First, the immune suppression associated with HIV is believed to impair clearance of syphilisFootnote 75. Further, HIV alters the natural evolution of syphilis, leading to more rapid progression through the disease stages —namely, to neurosyphilis and more aggressive and atypical signs of infection— and syphilis treatment complications have also been observedFootnote 2Footnote 75Footnote 77. Studies also indicate that it can be difficult to diagnose neurosyphilis in people living with HIV, insofar as CSF invasion-related symptoms can occur without syphilis infectionFootnote 2. Lastly, due to the shared risk factors for both HIV and syphilis infections (including biological susceptibility and sexual behaviours), people living with HIV are more likely to have repeated syphilis infections following successful syphilis treatmentFootnote 64Footnote 78.

Inconsistent condom use and sex with multiple or anonymous partners are major risk factors for both syphilis and HIVFootnote 76Footnote 79. Condom use is an effective prevention method to reduce the spread of STIs, but inconsistent or improper use decreases its effectivenessFootnote 80. A study conducted by Remis et al.Footnote 73 (n=442) showed that condomless anal and oral sex with casual partners was correlated with syphilis infection among gbMSM living with HIV in Toronto. Another study (n=194) identified syphilis co-infection in populations living with HIV and underlined a number of additional risk factors for syphilis co-infection, such as being a man who has sex with men, as well as alcohol and recreational substance useFootnote 72.

Overarching adverse social conditions, such as malnutrition, poverty, stigma, discrimination and exposure to violence, can put individuals at risk for syndemics, exacerbating the likelihood of acquiring co-occurring infectionsFootnote 71Footnote 76. These inequalities all have an impact on health and can lead to adverse health outcomes in key populations and can limit access to healthcare and appropriate treatmentFootnote 62Footnote 80.

Key messages

- National rates of syphilis infection have had a higher relative increase between 2013 and 2018, compared to chlamydia and gonorrhea rates.

- Gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men are the most affected population in past decades but high relative increases in rates have been observed in women of reproductive age in recent years.

- The female syphilis rate increase in recent years has translated to an increase in the number of congenital syphilis cases.

- Untreated syphilis is associated with a high burden of congenital cases and with reduced functioning for other cases.

- Trends of syphilis and other STIs have been described as a syndemic.

3. Epidemiological trends of syphilis in Canada, 2009-2018

3.1 Historical and recent national rates of syphilis in Canada

In Canada, syphilis has been nationally notifiable since 1924. In this section, Canadian syphilis CNDSS data covering the period of 1979 to 2017 are presented, along with preliminary data for 2018, provided directly by PTs. Current case definitions and details concerning data sources and analysis are described in Appendix B and Appendix C.

3.1.1 Historical syphilis trends in Canada

Canadian rates of syphilis were high until the 1940s, when they started to decrease significantly, a trend that continued until the 1980s. Rates remained low for most of the 1990s (Figure 4). This trend was also observed in other countries, such as the UKFootnote 81. Following this period of decline, Canadian rates began to climb again in the early 2000s (Figure 4). A similar increase in incidence rates was observed in the UK and the US over this time (Figure 5)Footnote 81Footnote 82.

Several hypotheses have been proposed to explain the growing incidence of syphilis in Canada over the past decades. In the 1990s and 2000s, a number of significant events occurred, including the introduction of antiretroviral therapy (ART) for HIV treatment in the late 1990s. This was followed by the arrival of the Internet and online apps for meeting potential sexual partners, as well as an increase in the use of certain drugs, such as crystal methamphetamine for chemsex in the 2000sFootnote 83. The term “chemsex” (or Party and Play, “PnP”) refers to the planned use of certain substances, including but not limited to methamphetamines, to extend the duration (hours to days) and intensity of sexual encounters (number of partners, types of practices)Footnote 84. While it is hypothesized that these ecological factors have shaped current STI incidence patterns in North America, no Canadian studies have confirmed the correlation between these population-level shifts and changes in syphilis incidenceFootnote 83.

Figure 4 - Text description

This graph displays the rate per 100,000 population for syphilis, between 1979 and 2017 in Canada. The horizontal axis shows the calendar years from 1979 to 2017. The vertical axis shows the rate per 100,000 population for syphilis overall, infectious syphilis, non-infectious syphilis and unspecified syphilis.

| Year | Rate per 100,000 population | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total Rate | Infectious Rate | Non-Infectious Rate | Unspecified Rate | |

| 1979 | 12.7 | 4.6 | 0.0 | 8.1 |

| 1980 | 12.6 | 4.9 | 0.0 | 7.7 |

| 1981 | 12.1 | 4.6 | 0.0 | 7.5 |

| 1982 | 9.8 | 4.2 | 0.0 | 5.5 |

| 1983 | 10.2 | 4.9 | 0.0 | 5.3 |

| 1984 | 12.7 | 6.0 | 0.0 | 6.7 |

| 1985 | 11.1 | 4.1 | 0.1 | 6.9 |

| 1986 | 9.1 | 2.6 | 0.1 | 6.4 |

| 1987 | 9.6 | 1.7 | 0.2 | 7.6 |

| 1988 | 6.4 | 1.3 | 0.2 | 4.9 |

| 1989 | 7.5 | 1.4 | 0.6 | 5.5 |

| 1990 | 7.7 | 1.3 | 2.1 | 4.3 |

| 1991 | 7.8 | 1.5 | 2.2 | 4.1 |

| 1992 | 6.8 | 1.2 | 2.5 | 3.2 |

| 1993 | 3.2 | 0.6 | 2.2 | 0.4 |

| 1994 | 2.7 | 0.6 | 1.7 | 0.3 |

| 1995 | 2.3 | 0.5 | 1.5 | 0.3 |

| 1996 | 1.9 | 0.4 | 1.4 | 0.2 |

| 1997 | 1.7 | 0.4 | 1.2 | 0.1 |

| 1998 | 1.7 | 0.6 | 0.9 | 0.2 |

| 1999 | 1.6 | 0.6 | 0.9 | 0.1 |

| 2000 | 1.7 | 0.6 | 1.0 | 0.1 |

| 2001 | 2.0 | 0.9 | 1.0 | 0.1 |

| 2002 | 3.0 | 1.5 | 1.2 | 0.2 |

| 2003 | 4.4 | 2.9 | 1.3 | 0.3 |

| 2004 | 5.3 | 3.6 | 1.4 | 0.4 |

| 2005 | 6.8 | 3.4 | 0.6 | 2.9 |

| 2006 | 10.4 | 4.1 | 0.4 | 5.9 |

| 2007 | 8.4 | 3.8 | 0.4 | 4.3 |

| 2008 | 8.6 | 4.2 | 0.7 | 3.8 |

| 2009 | 8.3 | 4.7 | 0.5 | 3.1 |

| 2010 | 8.4 | 5.0 | 0.7 | 2.7 |

| 2011 | 8.4 | 5.1 | 0.7 | 2.6 |

| 2012 | 9.7 | 5.9 | 0.7 | 3.1 |

| 2013 | 9.6 | 6.3 | 0.7 | 2.6 |

| 2014 | 10.3 | 6.8 | 0.8 | 2.8 |

| 2015 | 12.5 | 9.0 | 0.8 | 2.7 |

| 2016 | 15.0 | 10.7 | 1.1 | 3.2 |

| 2017 | 16.3 | 11.2 | 1.3 | 3.8 |

Source: Public Health Agency of Canada (2019). Canadian Notifiable Disease Surveillance System.

Infectious syphilis rates have continued to increase in Canada (Figure 5) in the last decade. Similar increases have been observed in other Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries (Figure 5). Canadian rates tend to be similar to those of England and slightly higher than those reported in the US. Detailed rates of infectious syphilis for Canada and other selected OECD countries for the last decade are presented in Appendix D.

Figure 5 - Text description

This graph displays the infectious syphilis rate per 100,000 population for OECD countries and Canada, between 2008 and 2017. The horizontal axis shows the calendar years from 2008 to 2017. The vertical axis shows the rate per 100,000 population for the United States (US), Australia, European Union (EU), Canada, and England.

| Year | Rate per 100,000 population | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| United States | United States P&SFootnote * | Australia | Australia-probableFootnote ** | European Union | Canada | England | |

| 2008 | 4.4 | 8.5 | 6.3 | 4.6 | 4.2 | ||

| 2009 | 4.6 | 8.8 | 6.0 | 4.5 | 4.7 | 5.5 | |

| 2010 | 4.5 | 8.9 | 5.0 | 4.2 | 5.0 | 5.0 | |

| 2011 | 4.5 | 8.7 | 5.7 | 4.6 | 5.1 | 5.5 | |

| 2012 | 4.9 | 9.6 | 6.8 | 4.6 | 5.9 | 5.6 | |

| 2013 | 5.5 | 10.9 | 7.8 | 5.1 | 6.3 | 6.2 | |

| 2014 | 6.3 | 12.4 | 9.0 | 9.0 | 5.4 | 6.8 | 8.2 |

| 2015 | 7.4 | 15.0 | 11.9 | 5.9 | 9.0 | 9.7 | |

| 2016 | 8.6 | 17.6 | 14.4 | 6.1 | 10.7 | 10.8 | |

| 2017 | 9.5 | 19.9 | 18.3 | 7.1 | 11.2 | 12.9 | |

Note: Canada’s definition of infectious syphilis includes confirmed cases of primary, secondary and early latent syphilis. Please note that some of the countries presented have slightly different definitions.

|

|||||||

Note: Canada’s definition of infectious syphilis includes confirmed cases of primary, secondary and early latent syphilis. Please note that some of the countries presented have slightly different definitions.

* The US includes confirmed primary and secondary stages only in its definition of infectious cases (US- P&S- blue dotted line). Confirmed early latent cases were added to primary and secondary cases to produce US rate estimates for the definition of infectious syphilis used in Canada (solid blue line).

** The dotted line for Australia represents the years for which the case definition included probable cases of infectious syphilis (in addition to confirmed cases of primary, secondary and early latent syphilis). In 2015, approximately 9% were reported as such.

The EU includes all cases of syphilis regardless of stage, although of the countries that provided staging information, 95% of cases were reported as either primary, secondary or early latent.

- Footnote a

-

Sources:

- Australia: Kirby Institute. HIV, viral hepatitis and sexually transmissible infections in Australia: annual surveillance report 2018. 2018. Australia’s notifiable disease status, 2015: Annual report of the National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System, NNDSS Annual Report working group

- European Union: European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). Syphilis - Annual epidemiological report for 2017. 2019 12 July 2019.

- United States: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Table 27. Primary and Secondary Syphilis — Reported Cases and Rates of Reported Cases by State/Area and Region in Alphabetical Order, United States and Outlying Areas, 2013–2017. 2018; Accessed September 10, 2019.

- Canada: Government of Canada. Canadian Notifiable Disease Surveillance System. 2018; 2019.

- England: Public Health England, Official Statistics, Sexually transmitted infections (STIs): annual data tables. Table 1 (b): Rates of new STI diagnoses in England by gender, 2008 – 2017, Rates per 100 000, Syphilis: primary, secondary, early latent, total.

Over the past 25 years, the distribution of syphilis cases across the four stages of infection has evolved. Historically, the vast majority of cases were diagnosed in the late latent phase (Figure 6). For example, in the 1990s, only 20% of cases for which a status was specified were diagnosed in the infectious stages. However, over time, cases have tended to be diagnosed earlier. Since 2006, primary, secondary and early latent cases now comprise at least 75% of the reported cases in Canada (Figure 6)Footnote 85-88. This increase in the proportion of cases diagnosed during an infectious stage may be related to the introduction of PCR testing used in the diagnosis of syphilis, especially at early stages and for individuals without antibody response. Increased screening in key populations may also play a role. Few provinces, including British Columbia and Ontario, stopped reporting non-infectious cases in the late 1990s, which has affected the proportion of non-infectious cases reported nationally. However, the observed pattern of an increased proportion of cases that are infectious over time holds even after excluding British Columbia and Ontario from the analysis. Reporting patterns by PT are presented in Appendix B.

Figure 6 - Text description

This graph displays the proportion of reported syphilis cases by stage of infection, between 1991 and 2017 in Canada. The horizontal axis shows the calendar years from 1991 to 2017. The vertical axis shows the proportion of total reported syphilis cases of primary, secondary, early symptomatic, early latent, unspecified infectious syphilis, late latent, and tertiary syphilis.

| Year | Proportion of Reported Syphilis Cases (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary | Secondary | Early symptomatic | Early latent | Infectious syphilis- unspecified stage | Late latent | Tertiary | |

| 1991 | 12.6% | 10.9% | 7.8% | 8.4% | 0.0% | 59.5% | 0.9% |

| 1992 | 7.6% | 9.1% | 6.1% | 9.4% | 0.0% | 66.0% | 1.9% |

| 1993 | 4.4% | 6.1% | 2.9% | 9.1% | 0.0% | 75.0% | 2.5% |

| 1994 | 6.7% | 5.9% | 6.5% | 8.1% | 0.0% | 69.5% | 3.3% |

| 1995 | 7.7% | 7.0% | 4.1% | 5.6% | 0.0% | 72.6% | 2.9% |

| 1996 | 6.5% | 6.2% | 1.9% | 8.3% | 0.0% | 74.2% | 2.9% |

| 1997 | 9.2% | 6.8% | 0.4% | 8.3% | 0.0% | 71.6% | 3.6% |

| 1998 | 5.2% | 2.7% | 1.4% | 4.8% | 26.3% | 58.5% | 1.1% |

| 1999 | 3.7% | 3.4% | 0.2% | 5.8% | 27.6% | 56.7% | 2.6% |

| 2000 | 5.3% | 4.3% | 0.8% | 6.2% | 19.5% | 61.6% | 2.3% |

| 2001 | 9.0% | 3.6% | 1.4% | 4.7% | 29.8% | 50.0% | 1.5% |

| 2002 | 10.5% | 16.3% | 0.4% | 7.4% | 21.7% | 41.8% | 2.0% |

| 2003 | 17.0% | 19.9% | 1.3% | 10.9% | 20.1% | 29.2% | 1.6% |

| 2004 | 18.9% | 23.5% | 1.2% | 9.5% | 19.4% | 25.0% | 2.5% |

| 2005 | 15.0% | 13.4% | 0.2% | 6.5% | 50.2% | 12.3% | 2.4% |

| 2006 | 15.1% | 16.4% | 0.7% | 10.9% | 47.5% | 7.8% | 1.6% |

| 2007 | 12.8% | 13.8% | 0.7% | 12.1% | 51.4% | 7.4% | 1.8% |

| 2008 | 17.8% | 13.9% | 0.9% | 11.4% | 42.5% | 11.4% | 2.0% |

| 2009 | 17.6% | 12.3% | 1.1% | 11.9% | 48.1% | 7.3% | 1.7% |

| 2010 | 14.2% | 14.3% | 2.3% | 12.6% | 45.3% | 9.7% | 1.6% |

| 2011 | 15.6% | 12.8% | 2.8% | 11.4% | 45.0% | 11.2% | 1.2% |

| 2012 | 11.7% | 11.9% | 0.7% | 11.6% | 53.5% | 10.0% | 0.7% |

| 2013 | 28.7% | 11.3% | 1.1% | 13.2% | 35.5% | 9.1% | 1.1% |

| 2014 | 12.6% | 9.8% | 0.8% | 11.2% | 55.4% | 9.1% | 1.1% |

| 2015 | 10.6% | 9.2% | 0.8% | 11.5% | 59.6% | 7.1% | 1.2% |

| 2016 | 10.7% | 9.5% | 0.2% | 12.9% | 57.0% | 8.6% | 1.1% |

| 2017 | 10.7% | 8.3% | 0.3% | 12.7% | 57.8% | 9.0% | 1.2% |

Note: Early symptomatic includes both primary and secondary cases.

Source: Public Health Agency of Canada (2019). Canadian Notifiable Disease Surveillance System.

Slight variations in staging, according to sex, have been observed in Canada. Between 1991 and 2017, the proportion of infectious syphilis cases was higher amongst males (Figure 7) than females (Figure 8) (case proportions by syphilis stage overall and sex are presented in Appendix E). Potential reasons for the difference in proportion of infectious syphilis by sex are presented in Section 2.2.

Figure 7 - Text description

This graph displays the proportion of reported syphilis cases by stage of infection, between 1991 and 2017 in Canada for males. The horizontal axis shows the calendar years from 1991 to 2017. The vertical axis shows the proportion of total reported syphilis cases of primary, secondary, early symptomatic, early latent, unspecified infectious syphilis, late latent, and tertiary syphilis.

| Year | Proportion of Reported Syphilis Cases | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary | Secondary | Early symptomatic | Early latent | Infectious syphilis- unspecified stage | Late latent | Tertiary | |

| 1991 | 15.0% | 11.2% | 9.3% | 7.4% | 0.0% | 56.2% | 0.9% |

| 1992 | 8.9% | 8.2% | 5.4% | 9.9% | 0.0% | 65.4% | 2.2% |

| 1993 | 4.4% | 6.8% | 2.6% | 9.4% | 0.0% | 73.1% | 3.7% |

| 1994 | 8.1% | 8.4% | 6.6% | 7.6% | 0.0% | 65.9% | 3.4% |

| 1995 | 10.0% | 8.4% | 4.0% | 6.5% | 0.0% | 67.3% | 3.7% |

| 1996 | 7.8% | 7.1% | 1.8% | 9.2% | 0.0% | 69.9% | 4.3% |

| 1997 | 12.8% | 6.2% | 0.4% | 7.8% | 0.0% | 68.7% | 4.1% |

| 1998 | 7.9% | 3.3% | 1.7% | 3.7% | 29.5% | 52.7% | 1.2% |

| 1999 | 5.1% | 4.3% | 0.4% | 5.9% | 27.5% | 53.7% | 3.1% |

| 2000 | 6.8% | 5.4% | 1.1% | 6.8% | 21.2% | 54.7% | 4.0% |

| 2001 | 10.4% | 5.5% | 2.0% | 5.8% | 29.7% | 45.0% | 1.7% |

| 2002 | 14.1% | 23.1% | 0.3% | 8.2% | 19.0% | 32.8% | 2.4% |

| 2003 | 20.1% | 24.0% | 1.5% | 11.9% | 17.0% | 23.7% | 1.8% |

| 2004 | 21.5% | 27.5% | 1.3% | 10.6% | 17.6% | 19.1% | 2.4% |

| 2005 | 15.4% | 14.9% | 0.3% | 6.7% | 52.0% | 8.7% | 2.0% |

| 2006 | 15.6% | 17.8% | 0.6% | 10.9% | 48.1% | 5.1% | 1.8% |

| 2007 | 13.0% | 15.1% | 0.8% | 10.4% | 54.6% | 4.7% | 1.3% |