Evaluation of the Centre on Diversity and Inclusion

On this page

- 1.0 Introduction

- 2.0 Results at a glance

- 3.0 Background

- 4.0 Evaluation methodology and scope

- 5.0 Literature and jurisdictional review: summary

- 6.0 Findings

- 7.0 In the absence of CDI

- 8.0 Recommendations

- Appendix A: Summary of Conclusions and Recommendations

- Appendix B: Logic Model

- Appendix C: Methodology

- Appendix D: Program Descriptions

- Appendix E: Management Response and Action Plan

- Appendix F: Additional OCHRO Programming Related to Diversity and Inclusion

1.0 Introduction

This report presents the results of the Evaluation of the Centre on Diversity and Inclusion (CDI) of the Office of the Chief Human Resources Officer (OCHRO), Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat (TBS).

The evaluation was conducted between January 2022 and March 2023 and was a requirement for CDI. Because CDI is a new program, the evaluation focused on:

- CDI’s relevance

- the implementation of CDI’s initiatives

- progress toward CDI’s immediate outcomesFootnote 1

The evaluation was:

- undertaken by TBS’s Internal Audit and Evaluation Bureau with the assistance of Goss Gilroy Inc.

- conducted in accordance with the Treasury Board Policy on Results and associated directive and standards

2.0 Results at a glanceFootnote 2

As this evaluation will show, under pressure to produce outcomes with insufficient time and resources, CDI has experienced challenges in meeting its immediate outcomes despite employees’ efforts and commitment. These challenges have included inadequate lead time required to research and implement initiatives.

“...to think that the issues that CDI was created to address would be dealt with in a three-year period … it’s foolhardy.”

CDI’s creation in 2020 was timely, given increasing support nationally and internationally for the value of using an equity, diversity and inclusion lensFootnote 3 to:

- better understand systemic barriers

- develop sustainable outcomes and better results

As part of a larger Government of Canada agenda on diversity and inclusion, CDI has been under pressure to produce results.

The evaluation found that there is an ongoing need for the Government of Canada to support an initiative that acknowledges the complexity of people management by providing advice, guidance and a coordinating function relating to diversity and inclusion. This complexity encompasses issues across the employee population of the federal public service, as illustrated in this statement: “The more diverse a team or organization is, the more leaders need to be skillful at interpreting and managing difference and the conflict that emerges.”Footnote 4

The following two documents are relevant to the findings of this evaluation:

- Building Leadership Competencies on Diversity and Inclusion: A Case Study in Canada (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development)

- Building a Diverse and Inclusive Public Service: Final Report of the Joint Union/Management Task Force on Diversity and Inclusion (Government of Canada)

The evaluation found that CDI has made progress toward the immediate outcome of improved horizontal coordination and coherence across departmental approaches to diversity and inclusion. This progress has been largely achieved through:

- the Designated Senior Officials for Employment Equity, Diversity and Inclusion (DSOEEDI) community of practice

- the Mentorship Plus Affinity Group, which comprises departments that have led the implementation of the Mentorship Plus program

Nonetheless, this evaluation report will show that CDI’s ability to progress toward its other short-term outcomes has been limited. Inadequate attention to program development, combined with a lack of governance and strategic direction, has resulted in the program using traditional activities to meet its goals.

Lastly, the evaluation notes gaps in understanding regarding CDI’s role in government-facing activities in diversity and inclusion and the public-facing roles of other government organizations.

When reading this report, it is important to understand that the term “equity-seeking” is not everyone’s preferred term.Footnote 5 Although the term reflects choices made when CDI was created, the language used to discuss diversity and inclusion continues to evolve, and not everyone agrees on the term’s exact meaning.

3.0 Background

-

In this section

3.1 Program context

Although diversity and inclusion are not new priorities, they have had an increased profile in recent years:

- the Clerk’s Call to Action Anti-Racism, Equity, and Inclusion in the Federal Public Service implicates all deputy ministers and, notably, there are specific responsibilities for diversity and inclusion set out in 14 ministerial mandate letters

- in the 2020 Speech from the Throne, the government committed to renewing its efforts to address systemic racism, in part by “implementing an action plan to increase representation in hiring and appointments, and leadership development within the Public Service”

- the 2021 Speech from the Throne reiterated that fighting systemic racism, sexism, discrimination, misconduct and abuse would remain a priority for the Government of Canada, including in its core institutions

- this commitment also appeared in the 2021 mandate letter of the President of the Treasury Board and included several new commitments to advance work to create a diverse, equitable and inclusive public service

CDI’s implementation has been steeped in social and political context, including:

- the rise of the “Black Lives Matter” movement

- the locating of unmarked graves of Indigenous children in Canada in 2022

- health, education and employment challenges as a result of COVID-19

Governments, non-profit organizations and other organizations are turning to equity, diversity and inclusion as one of many approaches to help:

- identify systemic barriers

- understand the role of power and privilege in sustaining inequities, exclusion and injustice

Canada took a similar approach when establishing CDI. Its creation was timely given the increasing support nationally and internationally of the value of using an equity, diversity and inclusion lensFootnote 6 to:

- better understand systemic barriers

- develop sustainable outcomes and better results

3.2 Program profile

CDI was established in 2020 as a temporary, stand-alone entity within OCHRO to create a diverse and inclusive public service by addressing the need for focused and accelerated implementation of diversity and inclusion initiatives across the public serviceFootnote 7.

A number of complementary initiatives were underway within OCHRO as CDI was launching, including:

- disaggregating and publishing data about the employee population of the federal public service to obtain a more accurate representation of gaps

- ensuring development of the right benchmarks for diversity

- the Self-Identification Project for employees

CDI’s work supports deputy heads’ mandate commitments, as outlined in the Clerk’s Call to Action, to bring lasting change to their organizations. The work is framed by the Government of Canada’s five Diversity and inclusion areas of focus for the public service:

- disaggregating and publishing data for a more accurate representation of gaps

- ensuring the right benchmarks

- increasing the diversity of the senior leaders of the public service

- addressing systemic barriers (including in foundational legislation)

- engagement, awareness and education

CDI supports departments in the latter three areas of focus (areas 3 to 5).Footnote 8

CDI’s mandate is to:

- lead new and innovative initiatives on diversity and inclusion

- develop innovative solutions for recruitment and talent management

- coordinate with stakeholdersFootnote 9 whose policies and programs affect the diversity and inclusion agenda

- co-develop solutions with the many diversity and inclusion networks across the public service

- lead change management and monitor its ongoing progress on these priorities and commitments

It is not part of CDI’s mandate to be a centre of expertise on diversity and inclusion within the Government of Canada.

To support its mandate and responsibilities, CDI delivers specific programs to support employment equity and equity-seekingFootnote 10 employees within the federal public service. Four of these programs are:

- the Mosaic Leadership Development program

- the Mentorship Plus program

- the Federal Speakers’ Forum on Lived Experience (formerly the Federal Speakers’ Forum)

- the Career Pathways for Indigenous Employees

Since the decision in 2023 to sunset the CDI, this programming has been absorbed by other sectors within OCHRO; program descriptions can be found in Appendix D.

3.3 Expected outcomes

CDI’s logic modelFootnote 11 identifies long-term, intermediate and immediate outcomes as follows:

Long-term outcomes

- Increased diversity in the public service

- Increased inclusion in the public service

Intermediate outcomes

- Decrease in workplace barriers faced by employees from equity-seeking groups

- Diversity and inclusion lens applied within departments for managing people

Immediate outcomes

- Increased departmental ability for inclusive people management

- Innovative diversity and inclusion talent management solutions for equity-seeking groups

- Improved horizontal coordination and coherence across departmental approaches to diversity and inclusion

- Increased career opportunities for equity-seeking groups

The outcomes of CDI’s logic model are further described with the findings in Section 6 (page 9) of this report.

4.0 Evaluation methodology and scope

-

In this section

The evaluation covered the period from CDI’s launch in August 2020 to March 2023. Interim findings were provided to CDI, enabling it to make program improvements before the end of the evaluation. The context of the pandemic was considered, as the program was implemented during COVID-19 restrictions. This formative evaluation assessed the following:

- relevance

- performance, specifically:

- implementation and efficiency

- effectiveness, that is, progress toward immediate outcomes

To meet evaluation standards and ensure an inclusive approach, the evaluation used a mixed methods approach that included quantitative and qualitative methodologies, with equity-seeking employee networks and partners among others, that included:

- a jurisdictional scan

- a document review

- key informant interviews

- two online surveys

Further information on the methodology used is available in Appendix C.

In addition, an Evaluation Working Group:

- contributed to the evaluation framework

- reviewed evaluation tools and key informant lists

- distributed the evaluation’s surveys

This group’s involvement ensured that the evaluation was inclusive and thoughtfully implemented, and its participation is gratefully recognized.Footnote 12 Members of the group comprised representatives from the following:

- the Centre on Diversity and Inclusion

- the Knowledge Circle for Indigenous Inclusion

- the National Managers’ Community

- the Interdepartmental Network on Diversity and Employment Equity

- the Public Service Commission of Canada

- the Office of Public Service Accessibility

4.1 Limitations

Two limitations to the evaluation were identified:

- Challenges with information management, exacerbated by high staff turnover, resulted in a lack of documentary evidence, which affected responses to several evaluation questions. This limitation was particularly evident when establishing focus groups of co-development participants. This limitation was partially mitigated by using multiple lines of evidence.

- A response rate could not be calculated for the survey sent to members of the National Managers’ Community and equity, diversity and inclusion human resources (HR) professionals because the link was circulated to a very large mailing list. The link was also posted as an open link on the National Managers’ Community website.

5.0 Literature and jurisdictional review: summary

-

In this section

The literature review

The literature emphasizes that equity, diversity and inclusion efforts are complementary to one another. One aspect cannot thrive and flourish without the others.Footnote 13 In considering diversity, the literature refers to, for example:

- casting a wider recruitment net to hire new talent

- establishing alliances with equity-seeking groups to aid representation

Implementing inclusion practices may mean:

- implementing specific training

- inclusive hiring

- de-biasing feedback and evaluations

- clarifying what is meant by “inclusion” and “belonging” and developing strategies that focus on these aspects

The literature cautions that not all training is useful, and poorly implemented training can make a biased workplace culture worse.Footnote 14 Lastly, the literature explains that equity practices require a “deep dive” to examine current policies and procedures to ask: How will each equity-seeking group experience this specific policy?

According to the literature review, there are five effective best practices for increasing diversity and inclusion:

- establishing responsibility structures

- recruitment retention strategies

- mentoring programs

- establishing employee resource groups

- diversity and inclusion training programs

In addition to these best practices, the literature review found that it is critical to adopt a deliberate change management processFootnote 15 to secure meaningful change in workplace culture. This process is a continuous journey and requires a long-term commitment.

The jurisdiction review

Evaluators searched across various jurisdictions for best practices and implementation lessons of similar initiatives. The jurisdictional review found limited sources. Although a variety of jurisdictions had material on diversity, there was less material on diversity and inclusion.

As noted in the literature review, the jurisdictional review also identified that only approaches that target systemic change with a deliberate change management approach lead to sustainable, high-impact and relevant outcomes. Only systemic change can ensure that organizational changes are not superficial and that they in fact result in:

- meaningful change in workplace culture

- behavioural change among staff

- change in processes and procedures, which are often impacted by unconscious biases

Given these findings, CDI’s design and intended outcomes are best suited for a longer term than was planned.

6.0 Findings

6.1 RelevanceFootnote 16

Conclusion

There is an ongoing need for an organization that focuses on diversity and inclusion in the federal public service that is supported by:

- strong governance

- a targeted vision

- a strategic framework to align with best practices

Departments need access to timely, centralized advice and guidance.

Findings

CDI was launched in direct alignment with a government priority. According to the evaluation’s document review, no other federal organization had a horizontal public service mandate for diversity and inclusion within the Government of Canada. All lines of evidence confirm that a formal, central structure is necessary to maintain the focus required to increase diversity and inclusion within the public service.

Although not a part of CDI’s mandate, the evidence shows a need within the public service for formal advice and guidance, which would be expected from a central agency:

- 43% of HR professionals surveyed indicated that they have the appropriate tools or guidance to help increase diversity in their organizations

- interview respondents expressed a need for a centre of expertise to provide guidance and policy interpretation

6.2 Performance: implementation and efficiency

Conclusion

Temporary funding, combined with a lack of strategic direction and governance, heavy workloads, and high turnover at all levels, has made it difficult to implement CDI efficiently.

Findings

At its launch, the President of the Treasury Board’s commitment and support of CDI was described as a tremendous asset. Given the prominence that the Treasury Board has given to CDI, it was accorded a high level of respect and credibility, particularly in the assistant and associate deputy minister and deputy minister communities. Its position within a central agency has underscored CDI as a government-wide initiative to tackle diversity and inclusion.

Although this support was instrumental in creating CDI, its implementation has faced challenges. CDI was established as a temporary structure, which does not align with the literature and best practice. Its temporary funding, uncertain future and reorganization midway through its initial mandate diminished its efficiency.

“What makes it a little dangerous is that it gives the impression that the public service is serious in dismantling discrimination without resourcing [it and] not taking a serious approach.”

With the Government of Canada’s growing interest in diversity and inclusion, the demand for CDI’s services has been beyond its bounds. Repeated staff assignments and secondments have been relied on to meet staffing needs and demand for services. CDI has at no point been fully staffed, and CDI interviewees reported being overworked and under a high degree of pressure to produce outputs. In 2021, only 30% of staff positions were indeterminate.

The lack of documentation in the corporate information management repository restricted the ability of this evaluation to confirm that CDI’s outcomes are being achieved:

- employees have not consistently developed and preserved documents that pertained to processes and decisions

- employees’ reliance on temporary information management repositories for corporate documents, and the attrition of staff, has resulted in significant losses of documentation

In CDI’s third year, there was an effort to improve information management administration.

Although there is a strategic framework for the Government of Canada’s larger diversity and inclusion agenda, there have been no finalized, CDI-specific strategic planning documents. This lack has contributed to an absence of clarity in communications about CDI’s mandate. For example, some key informants expected CDI to be a voice for employee networks or a centre for guidance and expertise, although it does not have the mandate (or capacity) for either activity. As set out in best practice, a strategic framework is a critical element to culture change and the success of diversity and inclusion initiatives.

6.2.1 Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic

CDI was implemented during the COVID-19 pandemic, which was both a facilitator and a barrier to its implementation. The pandemic introduced virtual work to many public servants, which enabled more engagement in CDI’s initiatives. For example:

- there were very high rates of participation in the annual 2021 Government of Canada Conference on Equity, Diversity and Inclusion

- virtual work has also enabled CDI to hire employees from across Canada, thereby increasing its own diversity

On the other hand, key informants and focus group participants suggested that the additional management and HR responsibilities that came with COVID-19 decreased departments’ time and “bandwidth” to undertake diversity and inclusion activities. Awareness of CDI and its initiatives has been non-existent for some departments, and pressure to implement initiatives has been resisted by others.

6.2.2 CDI’s use of co-development principles

Role and extent of co-development

Evidence from key informants, documents and focus groups shows that CDI has recognized co-development as an important approach in diversity and inclusion, and it has loosely applied the following definition to its co-development in the context of reaching out to employment equity members, equity-seeking groups and other formal and informal groups: “a voluntary process where management and bargaining agent work together on a jointly defined or desired matter in order to produce an agreed result.”Footnote 17

All CDI key informants noted CDI’s extensive consultations and its tremendous level of effort dedicated to engagement with employee networks organizations.

Using a survey and focus groups to reach members of employment equity and equity-seeking groups, CDI gathered records of lived experience to inform the design of:

- the Mentorship Plus program

- the Mosaic Leadership Development program (Mosaic program)

- the Federal Speakers’ ForumFootnote 18

Overall, documents indicate that from November 2020 to December 2021, CDI held numerous engagements to discuss its activities.

Due to gaps in information management, the evaluation was not able to contact the full range of implicated stakeholders to confirm their experience. Although those who participated in the evaluation indicated that CDI has been sincere in its engagement, this engagement was not perceived as co-development but rather as extensive consultation. In addition, key informants and focus group participants indicated that some efforts were rushed, preventing networks from having the time to engage in meaningful consultation with their own members. One survey respondent wrote, “I wish consultations with equity-seeking groups were more genuine. There is an impression that consultations are lip service only.”

Lack of evidence of co-developers’ influence on design

The absence of a feedback loop meant that employee networks did not know if or how their feedback influenced program design. For instance, key informants did not see recommendations from the Knowledge Circle for Indigenous Inclusion for the Career Pathways for Indigenous Employees co-development process reflected in the final product. Although co-development documents provided details on the program aspirations of co-developers, these elements have not always been implemented. Key informants questioned whether authentic co-development can happen in an environment where senior management approval could be seen as rendering judgment on employee networks’ needs and experiences.

For example, although suggested by co-development participants, the Mosaic program does not require departments to use alternative processes for candidate selection. Neither does it guarantee an EX‑01 position to participants or compel departmental executives to attend learning sessions on emotional intelligence.

Key informants highlighted broader issues that have affected views of the co-development process, such as:

- continued observations of consultations as being “top-down”

- general feelings of distrust

- insufficient engagement of grassroots employee groups already working in diversity and inclusion

6.3 Performance: effectiveness

Overall conclusion on performance

CDI has made progress toward one immediate outcome, that of horizontal coordination and coherence. It should be recognized that CDI’s immediate outcomes cannot be reasonably achieved in a three-year time frame.

The most complex diversity and inclusion issues identified in the literature are systemic barriers. Key informants and focus group participants did not observe that CDI’s activities have addressed these, and several felt that CDI does not have the levers to influence systemic change. With the growth in legislative requirements, expectations in ministers’ mandate letters, and pressures emerging from current events, several key informants felt that CDI has been pulled in multiple directions, with little time to critically assess the fit of these requests with CDI’s mandate. As the literature review identified, initiatives that have been targeting similar goals have been given longer delivery windows than CDI has been given.

6.3.1 Immediate outcome 1: increased departmental ability for inclusive people management

Conclusion

CDI has not noticeably increased departmental ability for inclusive people management. Questions remain about what “inclusive management” means.

Findings

The concept of inclusive people management is subjective. CDI has used the definition of “people management” from Building a Diverse and Inclusive Public Service: Final Report of the Joint Union/Management Task Force on Diversity and Inclusion:Footnote 19

- “improving representation, outreach, staffing, recruitment, onboarding, retention, career progression and management

- “addressing racism, discrimination, unconscious bias and harassment”

The evidence showed that interpretations of inclusive people management differ across individuals and departments, ranging from improved management of all employees to the improved management of equity-seeking employees specifically. Inclusive people management has also been interpreted as better equipping equity-seeking employees to manage.

One of the primary enablers of diversity and inclusion is time. Research demonstrates that hiring results in greater diversity when managers have adequate time to devote to examining potential candidates; respondents of the National Managers’ Community / HR survey results indicated that 9% of departments have taken measures to provide additional time for their staffing actions.

In addition to indicating a lack of time, only 45% of managers surveyed felt that they have the tools and guidance to increase inclusive people management in the public sector. Moreover, only 45% of managers and HR professionals indicated that their departments have taken steps to enable opportunities for difficult conversations with employees, which is a key characteristic of inclusive workplaces. As one key informant stated, “when you talk about inclusive people management, it has to be modelled first.” Racism is the second most discussed barrier among employees; employees are more likely to discuss racism with other employees (67%) than with their HR unit (40%) or their manager (45%).Footnote 20

Findings from the evaluation’s focus groups, surveys and interviews point to additional areas that inform the lack of progress on this immediate outcome:

- departments that have participated in the Mosaic and Mentorship Plus programs do not require sponsors or other senior leaders to engage in training to increase their ability for inclusive people management

- the Designated Senior Officials (DSOs) for Employment Equity, Diversity and Inclusion (DSOEEDI) committee has been pivotal in increasing awareness and ability in diversity and inclusion; though survey evidence showed that the group evolved away from having difficult conversations

- DSO survey respondents felt they received information that enabled them to increase diversity (47%) and inclusion (36%) within their own departments

- although there has been an anecdotal increase in organic engagement, dialogue and cross-sharing related to diversity and inclusion, key informants raised concerns about gaps in performance data resulting from a lack of measurement of inclusive people management:

- for example, it was generally felt by key informants and noted in Federal Speakers’ Form participation surveys that, although the forum has raised awareness of the experiences of diverse employees and moved the public service toward inclusion, the level of raised awareness has not been measured

6.3.2 Immediate outcome 2: innovative diversity and inclusion talent management solutions for equity-seeking groups

Conclusion

Evidence shows that CDI’s diversity and inclusion talent management solutions for equity-seeking groups have not been considered innovative. There has been a general lack of consensus about what constitutes innovation.

Findings

CDI has implemented a variety of traditional programs; there was no research evidence or stakeholder experience indicating that these programs were innovative. Despite aspirations to co-develop programs that would be an innovative response to equity-seeking employees’ experiences, such programming has not been the outcome.

Key informants and focus group participants perceived the Mosaic program, the Federal Speakers’ Forum, Career Pathways for Indigenous Employees, and the Mentorship Plus program as modified versions of regular leadership development, speakers’ forums, websites and mentorship programs.

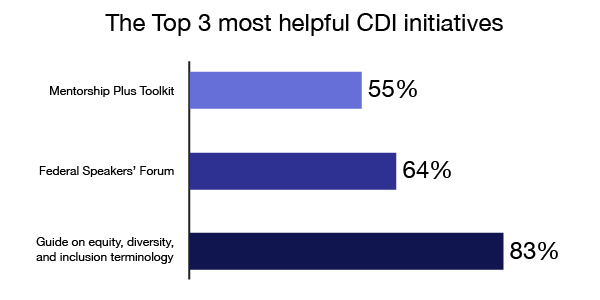

Figure 1 - Text version

- Mentorship Plus Toolkit: 55%

- Federal Speaker's Forum: 64%

- Guide on Equity, Diversity and Inclusion Terminology: 83%

DSO survey results showed that the top three most helpful CDI initiatives have been:

- the Guide on Equity, Diversity and Inclusion TerminologyFootnote 21 (83%)

- the Federal Speakers’ Forum (64%)

- the Mentorship Plus Toolkit (55%)

Although not CDI initiatives, the Clerk’s Call to Action (77%) and the Directive on Employment Equity, Diversity and InclusionFootnote 22 (75%) were also perceived to be helpful in encouraging diversity and inclusion focus. The results from the National Managers’ Community / HR survey did not find the same high rates of usefulness for these tools.

6.3.3 Immediate outcome 3: improved horizontal coordination and coherence across departmental approaches to diversity and inclusion

Conclusion

CDI has improved horizontal coordination and coherence to some extent, with progress shown primarily through the DSOEEDI community of practice and the Mentorship Plus Affinity Group.

Findings

The Directive on Employment Equity, Diversity and InclusionFootnote 23 gave rise to the DSOEEDI community of practice, as each deputy head named a designated senior official (DSO) for employment equity, diversity and inclusion. The DSOEEDI committee is managed by CDI and was described by CDI key informants as a “very strategic alliance.” The survey of DSOEEDI members indicated the following:

- 79% of them felt that the committee increased the coordination of diversity and inclusion initiatives across the federal public service

- 21% indicated the same regarding the coherence of these initiatives

In contrast with CDI key informants, DSO survey respondents noted that full progress toward this outcome has been hindered by DSOEEDI meetings because of:

- presentations that were too “in the weeds” (too detailed)

- insufficient strategic discussion

- decreasing engagement by CDI leadership over time

Acknowledging a gap in sponsorship capacity in small departments and agencies, CDI established a separate repository of Mentorship Plus sponsors for those employees.

The Mentorship Plus Affinity Group, which comprises departments that led the implementation of the Mentorship Plus program, indicated that the combination of the Mentorship Plus Toolkit and regular meetings has increased the coherence of the program’s implementation.

Most key informants felt that CDI has made efforts to complement other federal programs and activities, thereby avoiding duplication.

CDI has had formal partnerships, such as:

- collaboration with the Canada School of Public Service, Statistics Canada and others on the annual Government of Canada Conference on Equity, Diversity and Inclusion, a broadly accessible opportunity for training and raising awareness across the public service

- memoranda of understanding on interpretation services with Employment and Social Development Canada, second official language training for racialized employees at Public Services and Procurement Canada, and provision of professional and Indigenous advisory services with the Knowledge Circle for Indigenous Inclusion

Informal partnerships were developed at the outset of CDI’s implementation. These included:

- partnerships with other programs and groups (such as participation in interdepartmental committees and working groups)

- engagement in bilateral meetings

- outreach to employee networks

According to interviews, these partnerships have not always had the expected results because their informal nature has not been conducive to maintaining continuity due to the frequent turnover of CDI staff.

Communications about CDI’s mandate may have been unclear to departments:

- key informants lacked an understanding of CDI’s mandate and the mandates of departments that had complementary mandates

- many key informants were not aware of the differences between CDI and the Public Service Commission of Canada, the Federal Anti-Racism and LGBTQ2 Secretariats, and the difference between the mandates of internal- and external-facing organizations

This situation has led to misunderstandings about CDI’s mandate and its target community.

CDI created departmental guidance documents for both the Mosaic and Mentorship Plus programs:

- the focus groups and 55% of DSO survey respondents indicated that departments have found the Mentorship Plus Toolkit useful

- all lines of evidence showed that guidance material for the Mosaic program has been open to misinterpretation about the intent of the program, including participants’ promotion to an EX‑01 position:

- for example, the program did not guarantee promotion to an EX‑01 position as stated in the welcoming presentation to participants (“Opportunity to be assessed by a board for an EX appointment”),Footnote 24 whereas at the time of data collection, the evaluation found that the web-based guidance document stated, “The Mosaic Leadership Development program seeks to create meaningful change by including an EX‑01 appointment to participants who have successfully completed the program”; this statement was modifiedFootnote 25 when interim findings were provided to CDI

6.3.4 Immediate outcome 4: increased career opportunities for equity-seeking groups

Conclusion

There is little evidence to show that CDI initiatives have increased career opportunities for equity-seeking groups. Competing priorities have posed barriers.

Findings

The theory of change underlying CDI’s Mosaic programFootnote 26 and Career Pathways for Indigenous Employees assumes that an employment equity or equity-seeking employee’s career progression is constrained due to individual knowledge gaps that can be remedied by additional information or training. Although more individual training and skill development can be helpful, such an approach does not address the effect of institutional systemic barriers faced by equity-seeking employees. For example, the Mosaic program was described by some focus group participants as replicating the existing structure and barriers of the public service instead of tackling them:

- the Mosaic program still has barriers, such as sponsors who do not understand their role, with one protégé stating, “people were being taught to be ‘like’ the sponsors”

- the Mentorship Plus program has more directly targeted systemic barriers; some focus group participants said the program will “level the playing field” and increase the “ability for others to know who is out there”

Barrier

Competing federal priorities of supporting the advancement of employees in equity-seeking groups and the public service requirements for official languages remains an issue, albeit one that is outside the mandate of CDI.

Although most focus group participants did not indicate that they had more career opportunities by participating in the Mosaic program, they noted positive impacts such as:

- personal growth

- having a stronger voice

- having certain tools to succeed in interviews

Participants also appreciated sharing experiences with program participants who were in similar situations. This sharing validated their own experience and helped them feel they weren’t alone, for example, that “it’s not me that’s the problem.”

Of note, the National Managers’ Community / HR survey found that 58% of respondents indicated that official languages requirements:

- are a systemic barrier to advancement

- have impacted the career mobility of employment equity and equity-seeking employees in their department

This barrier was also noted by key informants and in survey comments.

6.3.5 Unintended outcomes

The speed at which CDI was implemented and developed its programs resulted in occasions when its programs have reinforced systemic barriers. CDI has relied on programs and processes already in place. It therefore:

- has missed an opportunity to be innovative

- has not challenged existing systemic barriers to diversity and inclusion

7.0 In the absence of CDI

When key informants were asked about potential outcomes if CDI were discontinued, they suggested two potential outcomes:

- a return to the piecemeal and inconsistent approach to diversity and inclusion

- there would be the message that diversity and inclusion is not a long-term priority for the federal government, which would reinforce the status quo and directly impact the ability of the public service to recruit and retain a representative workforce

Although most key informants and some survey respondents had mixed views about departments operating their own programs, most were concerned about potential lost momentum, believing that many issues would remain unresolved or potentially fall back without a central coordinating body. Although CDI has not made progress toward all its immediate outcomes, its creation alone is seen as progress. A few respondents said that because of CDI’s temporary nature, the government sent the message to public servants that diversity and inclusion is not a long-term priority.

8.0 Recommendations

Although it is unrealistic to assume that a single program can fully eliminate systemic barriers within the public service, deliberate action is required. The following recommendations will better align the program’s activities with its planned outcomes.

It is recommended that:

- CDI/OCHRO support the public service to fulfill the need for timely, coherent and coordinated policy advice and guidance on equity, diversity and inclusion by operating a policy-focused body that has governance mechanisms and defined roles and responsibilities

- CDI/OCHRO, while maintaining a focus on the program’s mandate, review the resources needed to meet the program’s strategic outcomes, considering the capabilities and competencies required

- For new diversity and inclusion programs or changes to existing programs, OCHRO include a change management strategy that acknowledges the role of consistent, sustained leadership as a requirement for systemic change

- OCHRO increase the likelihood of reaching its outcomes by reviewing governance and the risk drivers of new and short-term initiatives

Appendix A: Summary of Conclusions and Recommendations

-

In this section

Conclusions

Relevance

There is an ongoing need for an organization that focuses on diversity and inclusion in the federal public service that is supported by:

- strong governance

- a targeted vision

- a strategic framework to align with best practices

Departments need access to timely, centralized advice and guidance.

Performance: implementation and efficiency

Temporary funding, combined with a lack of strategic direction and governance, heavy workloads, and high turnover at all levels, has made it difficult to implement CDI efficiently.

Performance: effectiveness

CDI has made progress toward one immediate outcome, that of horizontal coordination and coherence. It should be recognized that CDI’s immediate outcomes cannot be reasonably achieved in a three-year time frame.

- Immediate outcome 1: CDI has not noticeably increased departmental ability for inclusive people management. Questions remain about what “inclusive management” means.

- Immediate outcome 2: Evidence shows that CDI’s diversity and inclusion talent management solutions for equity-seeking groups have not been considered innovative. There has been a general lack of consensus around what constitutes innovation.

- Immediate outcome 3: CDI has improved horizontal coordination and coherence to some extent, with progress shown primarily through the DSOEEDI community of practice and the Mentorship Plus Affinity group.

- Immediate outcome 4: There is little evidence to show that CDI initiatives have increased career opportunities for equity-seeking groups. Competing priorities have posed barriers.

Recommendations

It is recommended that:

- CDI/OCHRO support the public service to fulfill the need for timely, coherent and coordinated policy advice and guidance on equity, diversity and inclusion by operating a policy-focused body that has governance mechanisms and defined roles and responsibilities

- CDI/OCHRO, while maintaining a focus on the program’s mandate, review the resources needed to meet the program’s strategic outcomes, considering the capabilities and competencies required

- For new diversity and inclusion programs or changes to existing programs, OCHRO include a change management strategy that acknowledges the role of consistent, sustained leadership as a requirement for systemic change

- OCHRO increase the likelihood of reaching its outcomes by reviewing governance and the risk drivers of new and short-term initiatives

Appendix B: Logic Model

Centre for Diversity and Inclusion Logic Model

Long-term Outcomes

Increased diversity in the public service

Increased inclusion in the public service

Intermediate Outcomes

Decrease in workplace barriers faced by employees from equity-seeking groups

A diversity and inclusion lens applied within departments for managing people

Immediate Outcomes

Increased departmental ability for inclusive people management

Innovative diversity and inclusion talent management solutions for equity-seeking groups.

Improved horizontal coordination and coherence across departmental approaches to diversity and inclusion

Increased career opportunity for equity-seeking groups

Reach

Humans Resources, Hiring Managers, Bargaining Agents, Equity-seeking groups, Public Servants, Other government departments

Outputs

Training, Mosaic, Mentorship Plus, Federal Speakers Bureau, Legislation/policy recommendations

Activities

Developing partnerships, co-developing tools, training, initiatives, analyzing legislation/policy, coordination, monitoring initiatives

Appendix C: Methodology

-

In this section

The evaluation covered the period from CDI’s launch in August 2020 to March 2023. The context of the pandemic was considered, as the program was launched during lockdown restrictions. The evaluation assessed CDI using multiple lines of evidence that target the following.

Relevance

The extent to which the current program design aligns with the areas CDI means to address, including the extent to which the program reflects best practices and emerging issues in public service diversity and inclusion initiatives.

Performance

- Implementation: the extent to which the CDI model was designed and implemented as planned

- Efficiency: the extent to which CDI has made efficient use of resources as well as whether there were impacts on design and implementation from the short-term funding

- Effectiveness: the extent to which CDI has made progress toward its immediate outcomes

Evaluation methodologies

The evaluation methodologies used were as follows:

- A literature and jurisdictional review

- A document and administrative data review

- Key informant interviews (n=41): Interviews addressed key evaluation questions related to relevance and performance of CDI, including effectiveness and design alternatives. Key informants were identified by TBS’s Internal Audit and Evaluation Bureau in consultation with CDI. There were 41 English and French interviews with representatives from the following:

- Centre on Diversity and Inclusion

- federal department and agency partners

- participants in consultations and others

- Focus groups: In fall 2023, nine focus groups were held (39 participants total) with

- equity-seeking employment networks and partners

- Mentorship Plus program protégés

- Mentorship Plus Affinity Group participating departments

- Mosaic program participants

Individuals who wanted to participate but who were not able to attend a focus group were provided with a one-to-one meeting with the evaluator.

- Surveys: Two surveys were undertaken by TBS’s Internal Audit and Evaluation Bureau:

- the surveys were designed to contribute to answering key evaluation questions related to the relevance and performance of CDI, including:

- effectiveness and efficiency

- design alternatives

- the survey was launched in an online format using available contact information provided by CDI and members of the Evaluation Working Group

- the survey was available in English and French

- the surveys were designed to contribute to answering key evaluation questions related to the relevance and performance of CDI, including:

The list of respondents was drawn from the following sources:

- Designated Senior Officials for Employment Equity, Diversity and Inclusion: individual closed survey links were sent to all individuals on the master list created from these respondent lists

- Equity, Diversity and Inclusion HR email list: individual closed survey links were sent to all individuals on the master list created from these respondent lists

- National Managers’ Community GCconnex page

In addition, survey links were sent to individuals who asked to complete the survey, based on referral. Access was provided directly to such individuals.

- The DSO survey was launched in fall 2023. During the fielding period, weekly email reminders were sent. There were n=48 surveys completed of 92 emails sent, which yielded a response rate of 52%.

- The National Managers’ Community / HR survey was launched in fall 2023. During the fielding period, weekly email reminders were sent. There were n=185 surveys completed:

- because of the distribution method used, no response rate can be calculated

- the survey was accessible via an open link on the National Managers’ Community GCconnex page

- links were sent to an HR email list that contained hundreds of names

Appendix D: Program Descriptions

When it was created, CDI was led by an Executive Director (EX‑03), who was supported by:

- an EX‑02 responsible for stakeholder engagement and strategic management

- an EX‑01 responsible for special projects implementation

The EX‑03 Executive Director position was later reclassified as an EX‑04 Assistant Deputy Minister. When the incumbent left in late fall 2021, three sectors were merged into the People and Culture Division under a Senior Assistant Deputy Minister (EX‑05).

The diversity and inclusion principles used by CDI are as follows:

- “A diverse workforce in the public service is made up of individuals who have an array of identities, abilities, backgrounds, cultures, skills, perspectives and experiences that are representative of Canada’s current and evolving population.

- “An inclusive workplace is fair, equitable, supportive, welcoming and respectful. It recognizes, values and leverages differences in identities, abilities, backgrounds, cultures, skills, experiences and perspectives that support and reinforce Canada’s evolving human rights framework.”Footnote 27

CDI’s primary stakeholders are:

- Designated Senior Officials for Employment Equity, Diversity and Inclusion: a community of practice managed by CDI that discusses ongoing initiatives that support diversity and inclusion within the public sector

- Government of Canada partners: these include but are not limited to the Public Service Commission of Canada, the Canada School of Public Service, Canadian Heritage, the Privy Council Office, Women and Gender Equality, and Statistics Canada to coordinate and align diversity and inclusion activities

- employee networks and grassroots organizations: these include groups that fall outside of and within the Employment Equity Act designation

The Mosaic Leadership Development program equips equity-seeking employees at the EX minus 1 level with the required skills and competencies they need to enter the EX cadre.

The Mentorship Plus program pairs employees from employment equityFootnote 28 and equity-seeking groupsFootnote 29 with executive sponsors to support upward career mobility, facilitate increased visibility in informal networks, and provide access to development opportunities.

The Federal Speakers’ Forum on Lived ExperienceFootnote 30 provides an avenue for employees to share their lived experiences, raise awareness and build empathy, in support of CDI’s objective to inspire action to change the culture in the public service.

Career Pathways for Indigenous Employees is a website to support IndigenousFootnote 31 employees in mapping out their careers in the federal public service and addresses barriers related to onboarding, employee retention and career development faced at various career junctures.

Appendix E: Management Response and Action Plan

Management Response and Action Plan for the Evaluation of the Centre on Diversity and Inclusion

Recognizing that the evaluation of the Centre on Diversity and Inclusion (CDI) started less than a year after CDI was created, and that the scope of the evaluation focused only on a selection of initiatives advanced by CDI, we welcome the evaluation’s recommendations and propose the following action plan.

The actions outlined in this plan take into consideration that a decision was taken in 2023 to not renew the time-limited funding for CDI. However, some key programming has continued following the reprioritization and reallocation of resources within OCHRO.Footnote 32

Recommendation 1: CDI/OCHRO support the public service to fulfill the need for timely, coherent and coordinated policy advice and guidance on equity, diversity and inclusion by operating a policy-focused body with governance mechanisms and defined roles and responsibilities.

Management response: Agree. OCHRO recognizes the continued need for timely, coherent and coordinated policy advice and guidance to departments and agencies related to equity, diversity and inclusion, with clear governance mechanisms and defined roles and responsibilities.

| Proposed actions for Recommendation 1 | Start date | Targeted completion date | Office of primary interest |

|---|---|---|---|

CDI/OCHRO will:

|

January 2024 | June 2024 | CDI/OCHRO |

Recommendation 2: CDI/OCHRO, while maintaining a focus on the program’s mandate, review the resources needed to meet the program’s strategic outcomes, considering the capabilities and competencies required.

Management response: Agree. OCHRO recognizes that it needs to:

- review and align the resources needed to meet the program’s strategic outcomes and the delivery of the most impactful advisory and program functions

- ensure that the functions are equipped with the capabilities and competencies required

| Proposed actions for Recommendation 2 | Start date | Targeted completion date | Office of primary interest |

|---|---|---|---|

| CDI will review and realign as needed its resources in order to meet the program’s strategic outcomes. | January 2024 | June 2024 | CDI |

Recommendation 3: For new diversity and inclusion programs, or changes to existing programs, OCHRO include a change management strategy that acknowledges the role of consistent, sustained leadership as a requirement for systemic change.

Management response: Agree. We agree that future diversity and inclusion programs should include a clear change management strategy that includes the role of consistent, sustained leadership as a requirement for systemic change.

| Proposed actions for Recommendation 3 | Start date | Targeted completion date | Office of primary interest |

|---|---|---|---|

OCHRO will identify a change management framework that:

|

January 2024 | March 2025 | OCHRO |

Recommendation 4: OCHRO increase the likelihood of reaching its outcomes by reviewing governance and risk drivers of new and short-term initiatives.

Management response: Agree. OCHRO takes note of the need for good governance practices and the mitigation of risk drivers to increase the likelihood of reaching its outcomes while implementing new and short-term initiatives.

| Proposed actions for Recommendation 4 | Start date | Targeted completion date | Office of primary interest |

|---|---|---|---|

| OCHRO will review its governance structures and risks drivers of new and short-term initiatives. | January 2024 | March 2025 | OCHRO |

Appendix F: Additional OCHRO Programming Related to Diversity and Inclusion

-

In this section

- Disaggregated diversity and inclusion data

- Modernized Self-Identification Questionnaire

- Maturity Model on Diversity and Inclusion

- Bias mitigation initiatives

- Employment Equity Act and related policy support

- Support to interdepartmental equity, diversity and inclusion horizontal initiatives

- Employment Equity Champions and Chairs Committees and Circle Secretariat

- Succession planning for the assistant deputy minister community and talent pipeline

- Executive Leadership Development Program

Disaggregated diversity and inclusion data

Disaggregated diversity and inclusion data is data on the workforce composition of federal government departments. Such data is interpreted using a data visualization tool. This data:

- provides views into the composition of 21 employment equity subgroups

- provides departments with a more holistic picture of the experiences and representation of equity groups

- allows departments to identify more precisely where gaps remain and what action can be taken to improve representation

Modernized Self-Identification Questionnaire

Modernization of the Self-Identification Questionnaire includes developing a centralized platform for departments to collect representation data in accordance with the Employment Equity Act and beyond the four designated equity groups. This modernized data management approach will provide a more comprehensive view of employee demographic diversity, thereby improving measurement, reporting and programming toward a more inclusive workplace.

Maturity Model on Diversity and Inclusion

The Maturity Model on Diversity and Inclusion is a self-assessment tool that enables departments to measure their maturity across five key dimensions of diversity and inclusion. The model also offers departments specific actions tailored to their current maturity level, aiding them in advancing toward the next stage of maturity.

Bias mitigation initiatives

Bias mitigation initiatives are considered in talent management discussions with assistant deputy ministers and are integrated into an implementation package designed to empower departments to implement their own bias mitigation initiatives:

- at executive and non-executive levels

- in performance and talent management

- in other HR processes

Employment Equity Act and related policy support

OCHRO is responsible for reporting on the administration of the Employment Equity Act in the core public administration, including producing the annual report on employment equity report in the public service. Other policy activities include:

- the review of employment equity indicators in the government’s Management Accountability Framework (MAF)

- ongoing support to the implementation of the federal Action Plan for the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and the Inuit-Crown Indigenous Partnership action plan

Support to interdepartmental equity, diversity and inclusion horizontal initiatives

OCHRO provides advice and guidance to horizontal initiatives that advance equity, diversity and inclusion across government. These horizontal initiatives include:

- the Clerk’s Call to Action on Anti-Racism, Equity, and Inclusion in the Federal Public Service

- Canada’s Anti-Racism Strategy

- Canada’s Action Plan on Combatting Hate

OCHRO is also actively involved in advancing the Federal 2SLGBTQI+ Action Plan. OCHRO collaborates with:

- the Interdepartmental Terminology Committee on Equity, Diversity and Inclusion

Employment Equity Champions and Chairs Committees and Circle Secretariat

OCHRO fulfills the role of secretariat for three Employment Equity Deputy Minister Champions appointed by the Clerk, along with their respective members representing visible minorities, federal employees with disabilities, and Indigenous employees. CDI enables the committees to advance public service employment equity, diversity and inclusion objectives by providing a platform for networking and the exchange of best practices among departments.

Succession planning for the assistant deputy minister community and talent pipeline

OCHRO established and executed a comprehensive system-wide approach for recognizing and nurturing high-potential assistant deputy ministers. This initiative places a particular emphasis on talent drawn from employment equity groups, facilitating their accelerated readiness for promotion at the EX-05 and deputy levels. Resources are also allocated to strengthen an inclusive talent pipeline for upward mobility at all executive levels, through visibility initiatives that highlight diverse talent to deputy heads and heads of HR.

Executive Leadership Development Program

OCHRO ensures alignment between the Mosaic Leadership Development program with its complement, the Executive Leadership Development Program. This program is designed to offer focused learning and developmental opportunities for executives, with a commitment to dedicating at least 50% of its EX-01 to EX-03 cohort to employees from Indigenous Peoples, visible minorities, and persons with disabilities groups.

© His Majesty the King in Right of Canada, as represented by the President of the Treasury Board, 2024

ISBN: 978-0-660-72254-2