Assessing Program Resource Utilization When Evaluating Federal Programs

Notice to the reader

The Policy on Results came into effect on July 1, 2016, and it replaced the Policy on Evaluation and its instruments.

Since 2016, the Centre of Excellence for Evaluation has been replaced by the Results Division.

For more information on evaluations and related topics, please visit the Evaluation section of the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat website.

Centre of Excellence for Evaluation

Expenditure Management Sector

Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat

ISBN: 978-1-100-22230-1

Catalogue No. BT32-43/2013E-PDF

© Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada,

represented by the President of the Treasury Board, 2013

This document is available in alternative formats upon request.

Table of Contents

- Introduction

- 1.0 Value for Money in Federal Evaluations

- 2.0 Understanding Core Issue 5: Demonstration of Efficiency and Economy

- 3.0 Scoping Core Issue 5 in Evaluations: Choosing a Perspective

- 4.0 An Overview of Analytical Approaches to Addressing Core Issue 5

- 5.0 Logic Models, Program Theory, Cost Information and Core Issue 5

- 6.0 Next Steps for the Federal Evaluation Community

- 7.0 Suggestions and Enquiries

- Appendix A: The Evolution of Federal Evaluation Issues 1977 to 2009

- Appendix B: Performance in Evaluations of Federal Programs

- Appendix C: Program Readiness for Assessment of Core Issue 5

- Appendix D: Roles and Responsibilities in the Assessment of Core Issue 5

- Appendix E: Optimization of Inputs and Outputs

- Appendix F: Operational Efficiency Analysis

- Appendix G: Economy Analysis

- Appendix H: Bibliography

Introduction

Background: Why Assess Program Resource Utilization When Evaluating Federal Programs?

In the Government of Canada, evaluation is the systematic collection and analysis of evidence on the outcomes of programs to make judgments about their relevance and performance, and to examine alternative ways to deliver them or to achieve the same results. The purpose of evaluation is to provide Canadians, parliamentarians, ministers, deputy heads, program managers and central agencies with an evidence-based, neutral assessment of the value for money of federal government programs, initiatives and policies (Canada, 2009c, sections 3.1, 3.2, 5.1 and 5.2).1 In doing so, evaluation supports the following:

- Accountability, through public reporting on results;

- Expenditure management;

- Management for results; and

- Policy and program improvement.

In order to ensure that evaluations adequately support these uses, evaluations must assess not only a program's relevance and results achievement but also the resources the program uses. Evaluations need to explore issues such as what and how resources were used in the realization of outputs and outcomes, whether the extent of resource utilization was reasonable for the level of outputs and outcomes observed, and whether there are alternatives that would yield the same or similar results (or indeed other results) using the same or a different level of resources.

The assessment of program resource utilization in evaluations of Canadian federal programs is not new. All policies on evaluation, since the first in 1977, have required evaluators to consider some aspect of resource utilization as part of their evaluative assessment.2 This requirement has been articulated over time through evaluation issues such as efficiency and cost-effectiveness.3 Most recently, the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat's Directive on the Evaluation Function (Canada, 2009a)4 outlined a series of five “core issues” to be addressed in evaluations of federal programs. Core Issue 5, Demonstration of Efficiency and Economy, requires that evaluations include an assessment of program resource utilization in relation to the production of outputs and progress toward expected outcomes.

About This Document: Users and Uses

This document has been designed for evaluators of federal government programs, as well as for program managers, financial managers and corporate planners. Its goal is to assist these users in better understanding, planning and undertaking evaluations that include an assessment of program resource utilization by:

- Clarifying the purpose of assessing resource utilization as a core issue in evaluations;

- Assisting with the “scoping” of assessments of program resource utilization;

- Outlining a range of approaches to assessing program resource utilization; and

- Providing some methodological support for undertaking certain types of assessments of program resource utilization.

It is important to note that there is no “one size fits all” approach to assessing a program's resource utilization in evaluations. This document is therefore not intended as a step-by-step guide. Rather, it is intended as an orientation to assessing Core Issue 5. In undertaking assessments of program resource utilization in evaluations, heads of evaluation, as well as evaluation managers and evaluators, will need to ensure that individuals or teams performing the work have the knowledge, competencies, skills and experience to carry out the assessments of program resource utilization with an acceptable degree of quality, rigour and credibility.

Acknowledgements

This document was developed by the Centre of Excellence for Evaluation of the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat with the support of Dr. Greg Mason.

The Centre would like to thank the departments and agencies that reviewed and provided comments on draft versions of this document.

1.0 Value for Money in Federal Evaluations

Value for Money

=

Demonstration of Relevance

+

Demonstration of Performance

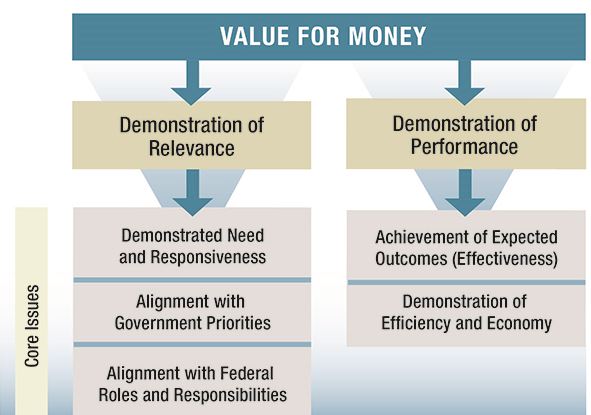

The definition of value for money in an evaluative sense, as approved by the Treasury Board through the Policy on Evaluation (Canada, 2009c), is the extent to which programs demonstrate relevance and performance. This definition builds on traditional definitions of value for money, which typically focus only on effectiveness, efficiency and/or economy of programs (Bhatta, 2006, pp. 185–187, 662). For evaluation purposes, integrating relevance into the concept of value for money allows evaluators to provide conclusions on performance that are better contextualized (i.e., data on performance can be interpreted in relation to issues such as the societal need for the program or the priority placed on the program by the elected government). By providing more contextualized findings and conclusions, evaluations will be better positioned to support decision making about program improvement and expenditure management (including expenditure review).

Annex A of the Directive on the Evaluation Function provides an analytical framework for arriving at conclusions on the relevance and performance of programs in the form of five “core issues” (CIs). These must be addressed in all evaluations undertaken in response to the Policy on Evaluation.5 The five CIs comprise three related to program relevance and two related to program performance:

Core Issues: Relevance

- Issue 1: Continued need for the program: Assessment of the extent to which the program continues to address a demonstrable need and is responsive to the needs of Canadians.

- Issue 2: Alignment with government priorities: Assessment of the linkages between program objectives, federal government priorities and departmental strategic outcomes.

- Issue 3: Alignment with federal roles and responsibilities: Assessment of the role and responsibilities of the federal government in delivering the program.

Core Issues: Performance (Effectiveness, Efficiency and Economy)

- Issue 4: Achievement of expected outcomes: Assessment of progress toward expected outcomes (including immediate, intermediate and ultimate outcomes) with reference to performance targets, program reach and program design, including the linkage and contribution of outputs to outcomes.

- Issue 5: Demonstration of efficiency and economy: Assessment of resource utilization in relation to the production of outputs and progress toward expected outcomes.

These five CIs constitute key lines of inquiry that evaluators need to explore (but are not limited to) in order to arrive at meaningful findings that support the development of conclusions on both the relevance and performance of programs.

Figure 1 - Text version

Figure 1 outlines a deconstruction of the concept of value for money that demonstrates how the five core issues to be addressed in evaluation of federal programs “map” into the concept.

In Figure 1, value for money is defined as comprising a) a demonstration of program relevance and b) a demonstration of program performance.

The demonstration of program relevance is defined as comprising and being addressed through three core issues: Core Issue 1–Demonstrated need and responsive; Core Issue 2–Alignment with government priorities; and Core Issue 3–Alignment with federal roles and responsibilities.

The demonstration of program performance is defined as comprising and being addressed through two other core issues: Core Issue 4–Achievement of expected outcomes (effectiveness) and Core Issue 5–Demonstration of efficiency and economy.

Appendix B contains a more detailed discussion on the concept of performance in evaluations of federal programs.

2.0 Understanding Core Issue 5: Demonstration of Efficiency and Economy

2.1 Why Assess Program Resource Utilization in Evaluations?

Evaluations that focus solely on the outcome achievement of programs, without taking into account the utilization of program resources, provide incomplete performance stories (Yates in Bickman & Rog, eds., 1998, p. 286; Herman et al., 2009, p. 61). The information needs of key evaluation users led to the inclusion in the Directive on the Evaluation Function of a core issue related to program resource utilization in evaluations of federal programs. In order to make better decisions (e.g., about program or policy improvement and expenditure management), deputy heads of departments, senior managers, program managers and central agencies need to be aware not only of program relevance, the observed results and the contribution of programs to those results, but also of issues such as the following:

- What and how resources are being consumed by programs;

- How those resources relate to the achievement of results (outputs and outcomes);

- How program relevance and other contextual factors affect both the resources being consumed and the observed results; and

- Potential alternatives to existing programs and/or resource consumption approaches.

Understanding the role that resources play in the performance of federal programs also helps program managers and corporate planners tell a more complete performance story in their reporting to parliamentarians and to Canadians.

In summary, CI5 is intended to act as a foundation upon which evaluators can base their assessments of resource utilization in federal programs.

Evaluation, Audit and CI5

CI5 is not intended to require evaluators to pursue “audit-like” lines of inquiry (i.e., assessing the design, function, integrity and quality of risk management, control systems and governance) (Canada, 2009d, section 3.3). Rather, CI5 is focused on the relationship between resource utilization, results achievement, relevance and the program's context.

2.2 Flexible Perspectives on Core Issue 5

2.2.1 Defining Core Issue 5

As provided in the Directive on the Evaluation Function (Canada, 2009a), CI5 (Demonstration of Efficiency and Economy) is defined as an “assessment of resource utilization in relation to the production of outputs and progress toward expected outcomes.”

By not focusing strictly on cost-effectiveness, as was the case under the 2001 Evaluation Policy (Canada, 2001), CI5 provides evaluators with flexibility in scoping and determining what aspects of resource utilization to explore in the context of any particular evaluation.

In the broadest of terms, the assessment of resource utilization is concerned with the degree to which a program demonstrates efficiency and/or economy in the utilization of resources. It is important to note, however, that these two concepts—efficiency and economy—represent a wide range of possible focuses and approaches to assessing program resource utilization.

Program Performance

=

Achievement of Expected Outcomes

+

Demonstration of Efficiency and Economy

It is also important to note that assessments of both efficiency and economy are linked to the assessment of program effectiveness (i.e., the degree to which intended results are being achieved) as outlined in CI4 (Achievement of Expected Outcomes). Collectively, CI4 and CI5 represent the analysis of overall performance of programs.

2.2.2 Demonstration of Efficiency

Focus of Analysis

- Allocative efficiency:

- Generally focuses on the relationship between resources and outcomes

- Operational efficiency:

- Generally focuses on the relationship between resources and outputs

Demonstration of efficiency in federal programs, in general terms, can be approached from two perspectives: “allocative” efficiency and “operational” efficiency.

- Allocative efficiency:

- This perspective on efficiency is generally concerned with the big picture of whether the resources consumed in the achievement of outcomes was reasonable in light of issues such as the degree of outcome achievement, the program's context and the alternatives to the existing program. The types of questions asked and analysis employed in the assessment of allocative efficiency generally involve comparison of the cost and outcomes of interventions that have the same or similar goals (e.g., of two existing programs or two elements within the same program) or comparison of an existing program to a real or hypothesized alternative. Often, the assessment of allocative efficiency can be accomplished using cost or economic analysis approaches (e.g., cost-effectiveness analysis); however, in some cases, more qualitative approaches (e.g., utility-based approaches) may also be employed.

- Operational efficiency:

- (Eureval/Centre for European Evaluation Expertise, 2006, p. 2): Sometimes referred to by a variety of other terms (including technical efficiency (de Salazar et al., 2007, p. 12), transformational efficiency (Palenberg, M. et al., 2011, p. 7.), management efficiency and implementation efficiency), this perspective on efficiency is largely concerned with how inputs are being used and converted into outputs that support the achievement of intended outcomes. The types of questions asked and analysis employed in the assessment of operational efficiency are those that are common in, but not exclusive to, formative evaluations, process evaluations, implementation evaluations, and design and delivery evaluations. As discussed in the following, this assessment often involves analyzing the degree to which outputs have been optimized in relation to the resources consumed in producing them and the manner in which they support outcome achievement.

2.2.3 Demonstration of Economy

As noted in the Policy on Evaluation (Canada, 2009c), federal government evaluations focus their assessments of economy on the extent to which resource use has been minimized in the implementation and delivery of programs. Economy is said to have been achieved when the cost of resources used approximates the minimum amount of resources needed to achieve expected outcomes. In this case, minimum does not refer to an absolute minimum. Rather, it refers to an optimized and contextualized minimum. This optimized and contextualized minimum is determined by analyzing the degree to which input costs were minimized based on the program's context, input characteristics (such as their quality, quantity, timeliness and appropriateness), extent of impact on outcomes achievement, and the alternatives available. This is discussed further below.

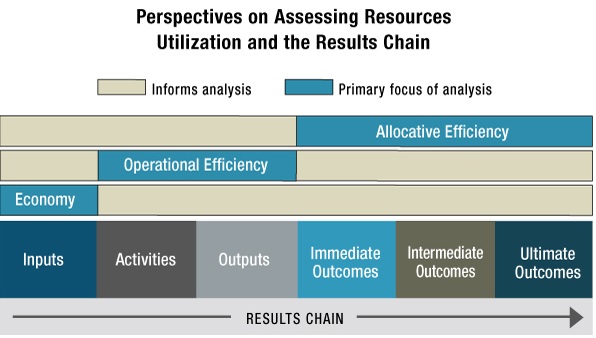

Figure 2 provides an overview of the relationship between the perspectives outlined in the preceding and program results chains (and, thus, logic models).

Figure 2 - Text version

Figure 2 outlines the relationship between the proposed analytical perspectives on Core Issue 5 and elements of a logic model. For illustrative purposes, a generic simplified logic model is presented. In this model, a series of successive logic model elements are presented. These are the program inputs, activities, outputs, immediate outcomes, intermediate outcomes and ultimate outcomes. These elements are successive in that each one leads to the next one in the chain (i.e., inputs lead to activities, activities lead to outputs, outputs lead to immediate outcomes, etc.).

In Figure 2, allocative efficiency is shown to be an analysis that primarily examines the relationship between a program's inputs and observed outcomes (at the immediate, intermediate and/or ultimate level). Operational efficiency is shown to be an analysis that primarily examines how program inputs are used to undertake activities that produce outputs. It is indicated that operational efficiency analysis is secondarily informed by the observed outcomes of the program. Finally, economy is shown to be an analysis that primarily focuses on the inputs provided to a program. It is indicated that economy analysis is secondarily informed by the observed outputs and outcomes of the program.

In some cases, alternative perspectives on assessing CI5 that do not necessarily fall within the categories outlined in the preceding may be considered appropriate. If alternative perspectives are used, evaluators should provide an appropriate rationale for the selected approach to assessing CI5.

3.0 Scoping Core Issue 5 in Evaluations: Choosing a Perspective

Rationale for Choice of Perspective on CI5

In the methodology section of evaluation reports, evaluators should explain the rationale for the choice of perspective on CI5.

Programs across the Government of Canada are highly diverse (e.g., in terms of delivery models, intended outcomes, beneficiaries, government priorities, program life cycles and levels of maturity). Evaluators will need to work with evaluation users and stakeholders to help identify which perspectives on CI5 can and should be included in the evaluation of a specific program. Following are examples of questions that may assist evaluators in this process:

- What are the specific purposes of the evaluation (e.g., how will it be utilized)? What are the information needs of the intended users? What types of information and perspectives on CI5 will best support meaningful utilization of the evaluation?

- At what stage is the program in its development (e.g., is it at a stage in its life cycle where assessment of allocative efficiency is feasible)? Alternatively, is the program the newest one in a series of programs that have sought to address the same issue?

- What are the main delivery mechanisms for the program? Are there clear activities and outputs contributing to specific outcomes? Or is the program complex, with activities and outputs contributing to multiple outcomes?

- What are the major program inputs? Are they mainly human resources (full-time equivalents (FTEs))? Are there goods or services being purchased as inputs to the program?

- What is the risk profile of the program? Has the department deemed it to be a high-risk program (e.g., of high materiality and high impact on Canadians)?

- When was the last evaluation? Did that evaluation adequately address CI5 and yield findings that suggested acceptable performance in this area?

- Are there known or suspected concerns about program efficiency or economy? If so, what are they?

- What is the status of performance measurement data available to support evaluation? Are program managers successfully implementing a performance measurement strategy that is collecting both financial and non-financial data that would support an assessment of CI5? If not, what would be required to collect or appropriately format this data, either before or during an evaluation?6

By exploring these questions (and others), evaluators can better determine which perspective(s) on resource utilization may need to be taken into account in the evaluation. In many cases, evaluations may need to address all three perspectives. However, in some cases, evaluation may need to examine only a subset of these perspectives to support the intended uses of the evaluation. Some examples of instances where the three different perspectives may be useful are outlined in Table 1.

| Perspective | Examples |

|---|---|

| Allocative Efficiency |

|

| Operational Efficiency |

|

| Economy |

|

To support the scoping exercise outlined in the preceding, Appendix C provides readers with a checklist for assessing the readiness of a program for an assessment of CI5. Appendix D also provides an overview of roles and responsibilities in preparing and undertaking assessments of CI5.

As with evaluations in general, evaluators will need to calibrate their approach to assessing CI5 based on the information needs of their senior managers and the risks associated with the program.

CI5: Assessment of Efficiency and Economy?

Evaluations are used by a range of actors—deputy heads, program managers, corporate planners and central agency analysts—to support a variety of decision-making, learning and reporting functions. In principle, the needs of these users will be best supported if evaluations address both efficiency and economy. However, in certain cases (e.g., evaluations of extremely low-risk programs that have simple delivery mechanisms, non-complex results chains and a single input such as FTEs), it might be argued that the need for assessing economy is not practical or feasible. In these cases, departments should provide an explanation or analysis as to why it was not practical or feasible to address economy issues.

4.0 An Overview of Analytical Approaches to Addressing Core Issue 5

Once a scoping exercise has identified the perspectives to be examined during the evaluation and evaluation questions have been developed, evaluators need to select one or more analytical approaches for assessing CI5.

Approaches to assessing program resource utilization in evaluations can be viewed on a continuum that comprises the following:7

- Cost-comparative approaches:

- These approaches to assessing CI5 generally involve comparing the resources utilized for some aspect of the program (e.g., the cost per outcome, cost per output, cost of inputs) to the resources utilized in other (often alternative) programs that have the same or similar intended results or to some other known standard (e.g., a benchmark or cost target).

- Qualitative/mixed approaches:

- These approaches typically involve the exercise of evaluative judgment based on qualitative and quantitative data about resource utilization in the program, to arrive at findings and conclusions. These approaches range from highly structured qualitative assessments and comparisons to theorized alternatives, to expert judgment and assessments of optimization.

- Descriptive approaches:

- These are non-critical approaches that involve only relating facts about the utilization of resources in a program (e.g., statement of actual budgets, cost per output, cost per outcome). No analysis or evaluative judgement is provided. Although descriptive analyses are generally insufficient for assessing CI5 in a meaningful manner, they may form the foundation for the qualitative/mixed and cost-comparative approaches outlined above.

Continuum of Analytical Approaches to CI5

This continuum of analytical approaches to CI5 is roughly analogous to the continuum of experimental to non-experimental to descriptive evaluation for assessing program effectiveness:

- Cost-comparative approaches:

- Test resource utilization with a counterfactual.

- Qualitative/mixed approaches:

- Build theories and test actual resource utilization against a counter-hypothetical, observations or alternative.

- Descriptive approaches:

- Provide empirical data with no analysis.

Within this continuum, numerous specific approaches can be used to support an analysis of CI5. Some of the more common approaches are outlined in Table 2.8 It is important to note that these represent only a small sample of approaches that evaluators may wish to adopt in addressing CI5.

| Analytical Approach | Cost-Comparative (CC) Qualitative/Mixed(QM) | Primary Perspective on CI5 Generally Analyzed Using This Approachtable 2 note * |

|---|---|---|

Table 2 Notes

|

||

| Cost-effectiveness analysis | CC | Allocative efficiency |

| Cost-benefit analysis | CC (QM)table 2 note † | Allocative efficiency |

| Cost-utility analysis | CC (QM) | Allocative efficiency |

| Operational efficiency analyses—examples include: | ||

|

CC | Operational efficiency |

|

CC | Operational efficiency |

|

QM (CC) | Operational efficiency |

|

QM | Operational efficiency |

|

QM (CC) | Operational efficiency |

|

QM | Operational efficiency |

|

CC or QM | Operational efficiency |

| Economy analysis—examples include: | ||

|

CC | Economy |

|

CC | Economy |

|

CC | Economy |

|

QM (CC) | Economy |

Summaries of these approaches are provided in the following.

Cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA): CEA, broadly speaking, refers to the comparative assessment of costs per “unit” of outcome (a cost-effectiveness ratio) between two or more program elements (e.g., entire programs, delivery elements of a single program, real or hypothesized alternatives) that a) have the same (or very similar) intended outcomes, and b) can be evaluated using the same measures or criteria (Levin & McEwan, 2001, pp. 10–11). For example, an evaluation of a smoking cessation program may choose to use CEA to compare the relative “per quit” cost of smoking cessation support groups with the cost of subsidizing nicotine replacement therapy (gum, lozenges or patches) for individual smokers (Herman et al., 2009, pp. 56–57).

Cost-benefit analysis (CBA): In its classic sense, CBA (also sometimes referred to as benefit-cost analysis), refers to analytical approaches that seek to monetize (i.e., assign financial value to) all the costs and benefits related to a program (e.g., entire programs, delivery elements of a single program) and compare their net present values, usually expressed in the form of a cost-benefit ratio. CBA therefore allows evaluators to compare the benefits (real or potential) of programs (or program elements) that have different intended results (Brent, 2002, pp. 144–146; Levin & McEwan, 2001, pp. 11–19). For example, CBA may be used as an evaluation tool to help decision makers decide between two non-related program options (e.g., investing in a smoking cessation program versus investing in early childhood education). However, and perhaps more commonly, CBA can be used to compare program options that are somehow related, for example, comparing the net benefit of a flood diversion program designed to address average flooding events with one designed to handle worst-case flooding events.

One of the distinctive features of CBA is that, in principle, it takes a broader societal view of costs and benefits (compared with other approaches such as CEA, which tends to focus on the program) (Herman et al., 2009, p. 56). As such, CBA can be useful, in particular, for addressing allocative efficiency issues. CBA can also be useful in identifying unexpected outcomes or results of programs. The sensitivity of CBA may mean that it is less useful for informing assessments from the perspectives of operational efficiency or economy of inputs, depending on the level at which costs and benefits are identified.9

One of the challenges with CBA lies in quantifying and monetizing the costs and benefits. In response to this challenge, various authors have offered approaches to incorporating qualitative elements into CBA, leading to the emergence of qualitative cost-benefit analysis, which seeks to provide a more comprehensive account of the benefits and costs of programs (Rogers, Stevens & Boymal, 2009, pp. 84, 89; van den Bergh, 2004, pp. 389–392).

Cost-utility analysis (CUA): Cost-utility analysis, a relative of CEA, compares the utility of a program (i.e., the worth, value, merit of—or degree of satisfaction with—program outcomes, usually as defined from the perspective of beneficiaries) in light of the costs (Levin & McEwen, 2001, pp. 19–22; White et al., 2005, pp. 7–8). Although in some CUAs “utility” is a highly structured concept (e.g., in the health sector, utility is measured in terms of quality-adjusted life years or healthy-year equivalents), indications are emerging that some latitude can be exercised in developing other quantitative or qualitative “units” of utility (e.g., constructed at the level of immediate or intermediate outcomes) in what might be called a realist or calibrated approach to analyzing the reasonableness of costs versus outcomes. CUA can be useful, in particular, for addressing allocative efficiency. At the same time, CUA may provide insight into potential areas of concern with regard to operational efficiency or economy, based on the perspectives of program users (i.e., beneficiaries) or others.

Operational-efficiency analysis (OEA): For the purposes of evaluations of federal programs, OEA (referring directly to the CI5 operational efficiency perspective outlined above) includes a broad range of analytical approaches that can be used in assessing how programs are managed and organized to support the achievement of results. These approaches may include cost-based models that focus on assessing the cost of specific outputs in relation to comparators (e.g., planned costs, benchmarks), assessments of the optimization of outputs and/or the assessment of efficiency issues, and opportunities at the level of program activities. These analyses are undertaken in light of program relevance and other contextual issues (Eureval/Centre for European Evaluation Expertise, 2006, p. 14). However, although some approaches to OEA may draw on audit data, the analysis is not intended to duplicate or overlap with issues typically explored in internal audits that focus on the design and functioning of risk management, control and governance processes—often at an organizational (rather than program) level (Canada, 2009d, section 3.3). Some examples of analytical approaches to operational efficiency analysis include the following:

- Benchmarking: Comparisons of actual cost per unit of program output versus a known standard or best practice (McDavid and Hawthorn, 2006). Where actual cost per unit of output varies greatly from the benchmark, the evaluator can work to identify a reasonable rationale for the variances and determine what, if any, effect these have had on the production of outputs and/or the achievement of outcomes.

- Planned to actual cost comparison and analysis/expenditure tracking and analysis: Comparisons of planned program costs (e.g., by unit of output, by budget line item) with actual costs or with a trend in cost of output over time. Where there have been significant cost variances, the evaluator can work to identify a reasonable rationale for the variances and determine what, if any, effect these have had on the production of outputs and/or the achievement of outcomes.

- Business process mapping and analysis: Business process mapping and analysis refers broadly to a range of activities that involve identifying key delivery processes and analyzing them to determine whether any challenges (e.g., bottlenecks) are inhibiting the achievement of outputs and outcomes or are otherwise inefficient. These business processes may be mapped out using logic models or program theories. In some cases, the process maps can be costed to allow for cost analysis. In other cases, the approach might be more qualitative (e.g., based on observation of business processes, interviews with key informants).

- Fidelity assessment (O'Connor, Small & Cooney, 2007) / testing theory of implementation: Fidelity assessments or testing a theory of implementation are generally qualitative approaches to assessing operational efficiency. These approaches focus on assessing the degree to which a program was implemented according to its initial plans, identifying variances in implementation, and examining these in order to determine the rationale for the variances and the effect they had on costs or on the achievement of outputs, outcomes or costs. These approaches also allow for an assessment of the changes in delivery made by the program in its implementation approach and the impact that these had on costs or on the production of outputs or achievement of outcomes. Where possible, these approaches may be combined with comparative cost-based approaches.

- Participatory appraisal: Participatory appraisal is a predominantly qualitative approach that involves working with key stakeholders to identify potential inefficiencies that may be consuming resources unnecessarily or inhibiting the achievement of outputs or outcomes. Tools such as outcome mapping may be useful in this regard.10

- Optimization analysis11 / expert opinion: Optimization analysis refers to the assessment of the degree to which outputs can be said to have been optimized when certain factors, including the cost, quantity, quality, timeliness and appropriateness of the outputs produced, have been balanced by program managers in a defensibly rational manner in light of the program theory (i.e., assumptions, risks, mechanisms and context), relevance (i.e., CI1, CI2 and CI3) and observed results (i.e., outcomes) of the program (CI4). Inefficiencies can be said to be present where one or more of the optimization factors have not been adequately balanced and output or outcome achievement has been affected. Similarly, expert opinion refers to other approaches to assessing optimization based on the knowledge and experience of an expert observer. Expert opinion approaches may be formal (i.e., use specific criteria) or informal, although the latter should be used only rarely and in programs where the level of risk and complexity require only minimal rigour. Appendix E provides more details on the concept of optimization.

- Comparison with alternative program models: Where possible, operational efficiency of programs can be compared with real or hypothesized program alternatives. This assessment might be cost-based or qualitative or both.

Appendix F provides more discussion on operational efficiency analysis, including a list of common lines of inquiry.

Economy analysis: For the purposes of evaluations of federal programs, economy analysis refers to analytical approaches for assessing how programs have selected inputs12 intended to support the production of outputs and the achievement of results. These approaches may include analysis of the cost of inputs in relation to comparators (e.g., alternative inputs for the same delivery model or delivery models using other inputs) and/or more qualitative assessment of inputs (such as analysis of the impact of human resources configurations in relation to program delivery and observed results). These analyses are undertaken in light of program relevance and other contextual issues. Like operational efficiency analysis, economy analysis is not intended to duplicate or overlap with internal audit processes but rather, where appropriate and available, to take advantage of some of the data generated by internal audits. Examples of analytical approaches to economy analysis include the following:

- Benchmarking: Similar to the use of benchmarking for operational efficiency analysis (see above) except that the focus is on the cost of inputs.

- Planned to actual cost comparison and analysis: Similar to the use of benchmarking for operational efficiency analysis (see above) except that the focus is on the cost of inputs.

- Comparative cost per input: Similar to the comparisons with alternative program models discussed above. Where possible, economy of inputs can be compared with real or hypothesized alternatives.

- Optimization analysis or expert opinion: Similar to the use of optimization analysis or expert opinion related to outputs except that the focus is on inputs.

Appendix G provides more discussion on economy analysis, including a list of common lines of inquiry.

The list of approaches to assessing efficiency and economy outlined in the preceding is not exhaustive. Other analytical approaches (e.g., cost-feasibility analysis, cost-minimization analysis, multi-attribute decision making and others) not discussed in detail here may also serve as the basis for assessment of CI5.

Many of the approaches outlined above require specific technical and methodological knowledge and experience. Heads of evaluation and evaluation managers should ensure that the individual or team working on the assessment of CI5 have (individually or collectively) the knowledge, skills and competence to adequately undertake the activities and analysis required for successful assessment of CI5.

As with evaluations in general, evaluators will need to calibrate their approach to assessing CI5 based on the information needs of their senior managers and on the risks associated with the program.

5.0 Logic Models, Program Theory, Cost Information and Core Issue 5

5.1 Logic Models and Program Theory

Many of the approaches to assessing CI5 that are outlined in the preceding section (e.g., cost-effectiveness analysis) require evaluators to identify units of analysis (e.g., inputs, activities, outputs, outcomes, results chains or service lines). In addition, evaluators may need to build an understanding of the context, assumptions, mechanisms and risks associated with programs. Logic models and program theories or theories of change can assist evaluators in this regard.

Logic Models

Logic models are a commonly recognized tool of results-based management in Canadian federal government programs. They are an integral element of the performance measurement strategies that program managers are responsible for developing at the design stage of programs (see the Directive on the Evaluation Function, 2009, section 6.2). Inherent in many logic models are results chains that align the specific inputs, activities and outputs of a program to its intended outcomes.13 Being able to identify the program's results chains may help identify units of analysis for assessing the cost of outputs, and the efficiency of the program and management processes intended to produce them.

Readers are encouraged to refer to the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat publication Supporting Effective Evaluations: A Guide to Developing Performance Measurement Strategies for more information on logic modelling.

Program Theory and Theory of Change

Increasingly, program managers are being encouraged, through their performance measurement strategies, to not only define their program logic (e.g., through the use of logic models) but also to delineate a program theory or theory of change that underlies their program logic. These theories build on logic models or results chains by articulating the mechanisms, assumptions, risks and context that explain how and why a program is intended to function, how and why intended results will come about, and may explain why certain decisions were made about program delivery.

A well-articulated program theory can serve both program managers and evaluators in helping to identify units that can be analyzed in terms of their relative economy and efficiency.

Program theories can play several other roles in the assessment of CI5, including the following:

- Identifying the processes, mechanisms and activities that are being used to operationalize the program and explaining why the outputs are plausibly linked to the outcomes;

- Identifying planned attribution of outcomes to outputs, outputs to activities, and activities to inputs or the planned contribution of programs to outcomes;

- Explaining the decisions made by program managers in terms of program design, selection of resources and delivery models, and other key implementation decisions; and

- Revealing the context of the program (including societal or other factors that may reinforce or act against the realization of expected outcomes).

Readers are encouraged to refer to the growing body of literature on program theory and theory of change evaluations and the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat publication Theory-Based Approaches to Evaluation: Concepts and Practices.

5.2 Proactive Identification of Cost Information

All perspectives on CI5 require information about program costs. The term “cost” refers to the value (generally, but not always, economic value) of the resources consumed in undertaking an activity, producing an output or realizing an outcome of a program (Guide to Costing, Canada, 2008).

Heads of Evaluation, Program Managers and Cost Information

Where applicable, heads of evaluation should take advantage of processes such as commenting on Treasury Board submissions, compiling the Annual Report on the State of Performance Measurement, and departmental evaluation planning to reinforce with program managers the need to collect cost information in a manner that supports the assessment of CI5.

There are various types of costs normally associated with Canadian federal government programs. These include the following:

- Operating costs:

- There are generally considered to be four types of operating costs—salary and benefits; operational costs related to accommodation, supplies, workstations, communications, etc.; professional services; and direct corporate overhead.

- Capital costs:

- These include the cost of developing new capital infrastructure and the cost of cyclical replacement of capital items.

- Costs of services from other government departments:

- For some programs, a significant portion of their services is delivered by other government departments and agencies.

- Non-administrative disbursements:

- These are typically referred to as grants and contributions or transfer payments to third-party delivery agents or other parties outside the federal government.

- Non-government costs:

- These are costs borne by parties other than the Government of Canada, including participants' costs (e.g., user fees, application costs or compliance costs) and other governmental and non-governmental partners.

Calibrating Costing and Cost Tracking

Program managers, financial managers and heads of evaluation will need to consider the relative size, scope and risks of the program in determining the complexity of the costing and financial tracking systems required to effectively support evaluation.

Program managers and financial managers should follow the instructions on costing outlined in the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat Guide to Costing in identifying cost objects, bases, classifications and assignments. Moreover, program and financial managers should:

- Identify cost objects based on discernible activities, outputs, service lines, results chains and/or immediate outcomes, with a mind to developing “units of analysis” that can be considered in the assessment of program efficiency and economy;

- Consult with heads of evaluation concerning plans for collecting and tracking financial data to ensure that they will effectively support the evaluation of the program, including CI5;

- Take into account the types of evaluation questions and related data needs outlined in the sections on assessing economy and efficiency outlined later in this document; and

- Seek cost assignments and allocations that help reflect the true cost of the objects and the program as a whole (e.g., ways of assigning or allocating operating and maintenance costs to specific cost objects).

Decisions about the complexity of costing and financial expenditure tracking should be taken with due consideration for the size, scope and risks associated with the program. For example, low-risk programs that have relatively simple service lines requiring minimal inputs (e.g., only operations and maintenance) leading to specific results may choose to define cost objects at the level of immediate outcomes. In these cases, evaluators may choose to approach the assessment from the allocative efficiency perspectives.

5.3 Retroactive Identification of Cost Information

Depending on the maturity of the program's costing and financial tracking systems, evaluators may encounter challenges, including the following:

- Lack of cost data;

- Low-quality cost data; and

- Cost reporting that is not clearly aligned with activities, outputs, immediate outcomes, services lines or other analytical units that are useful for evaluative purposes.

Although in some cases programs may not have usable cost data, it would be highly unusual for a program to have no financial data. A list of some of the common sources of financial data (or data that can support the evaluator in determining costs) includes the following:

- A program's Financial Information Management System;

- Recent audits or operational reviews;

- Program budgets;

- A program's logic model and theory of change;

- Program planning, reporting, management and operational documents;

- Program and non-program stakeholders (e.g., management, staff and clients);

- A department's budget and/or budget reports;

- Current literature about similar programs; and

- Performance measurement data (collected in response to the performance measurement strategy and/or performance measurement framework).

Where cost data is not available or not aligned with analytical units that are useful for analyzing CI5, evaluators may need to undertake exercises to help allocate costs to units of analysis. For example, evaluators may use the following:

- Staff surveys to help approximate the time employees are spending on different activities or outputs. These surveys may also be used to support other analytical approaches to CI5 (e.g., participatory appraisals);

- Time logs, even if kept for only a short period such as a month, can help approximate the time that employees are spending on different activities or outputs. Time logs can also be useful in identifying activities that require the greatest effort, allowing evaluators to focus their analysis; and

- Process maps may be useful in identifying the major activities and service lines in a given program.

As noted previously, challenges with financial data (e.g., lack of data, data coding not aligned with evaluation units) does not constitute a rationale for not addressing the five CIs or for downgrading evaluation scopes, approaches or designs.

6.0 Next Steps for the Federal Evaluation Community

This guide provides evaluators of federal government programs with an overview and orientation to the assessment of CI5. As noted above, there is a wide range of more traditional approaches to assessing resource utilization—such as cost-effectiveness and cost-benefit analysis—that evaluators can draw from when appropriate. The evaluation community is encouraged to build capacity to undertake these types of analysis.

At the same time, newer and innovative approaches (such as qualitative cost-utility analysis and testing implementation theories) are emerging, and these have the potential to provide alternatives where traditional cost-based approaches may not be suitable or feasible. The federal evaluation community, including the Centre of Excellence for Evaluation and evaluation functions in departments and agencies, should pilot alternative approaches that appear promising for use in different programs and contexts.

7.0 Suggestions and Enquiries

Suggestions and enquiries concerning this guide should be directed to the following:

Centre of Excellence for Evaluation

Expenditure Management Sector

Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat

Email: evaluation@tbs-sct.gc.ca

For more information on evaluations and related topics, visit the Centre of Excellence for Evaluation section of the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat website.

Appendix A: The Evolution of Federal Evaluation Issues 1977 to 2009

| Policy | Evaluation Policy (1977)table A1 note * | Evaluation Policy (1992)table A1 note † | Review Policy (1994)table A1 note ‡ | Evaluation Policy (2001) | Policy on Evaluation (2009) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Table A1 Notes

|

|||||

| Core issues | N/A | Relevance | Relevance | Relevance | Relevance |

| Effectiveness | Success | Success | Success | Achievement of expected outcomes | |

| Efficiency | Cost-effectiveness | Cost-effectiveness | Cost-effectiveness | Resource utilization (demonstration of efficiency and economy) | |

In order to help ensure that the federal evaluation function continues to be responsive to the needs of its clients (i.e., the users of evaluation), the Policy on Evaluation (2009) builds on and clarifies the evaluation issues identified in the Evaluation Policy (2001) (i.e., relevance, success and cost-effectiveness) by:

- Clearly defining the concept of value for money for evaluative purposes;

- Clearly identifying relevance and performance as sub-components of value for money;

- Providing evaluators with three core evaluation issues to help guide the assessment of program relevance;

- Grouping success and cost-effectiveness together as elements of program performance; and

- Providing evaluators with two core evaluation issues to help guide the assessment of program performance.

The suite of five core evaluation issues, used consistently over time, will help the government build a reliable base of evaluation evidence that is used to support policy and program improvement, expenditure management, Cabinet decision making, and public reporting at both the level of individual programs and horizontally across government.

Appendix B: Performance in Evaluations of Federal Programs

As noted in Annex A of the Policy on Evaluation, performance is defined as the extent to which effectiveness, efficiency and economy are achieved in federal government programs.

Building Blocks of Performance: Core Issue 4 (Achievement of Expected Outcomes) and Core Issue (CI) 5 (Demonstration of Efficiency and Economy)

Core Issue 4 (Achievement of Expected Outcomes)

Assessment of progress toward expected outcomes (including immediate, intermediate and ultimate outcomes) with reference to performance targets, program reach and program design, including the linkage and contribution of outputs to outcomes.

CI4 and CI5 provide evaluators with two key building blocks in the assessment of program performance. CI4 (Achievement of Expected Outcomes) provides a platform for evaluators to identify and explore questions related to the effectiveness of programs, including but not limited to questions about the following:

- Observed results (both expected and unintended);

- The attribution of observed results to government programs, or the contribution of government programs to observed results;

- Reach of program results;

- Program design and delivery; and

- Alternatives to existing programs.

Core Issue 5 (Demonstration of Efficiency and Economy)

Assessment of resource utilization in relation to the production of outputs and progress toward expected outcomes.

CI5 provides evaluators with a complementary platform to identify and explore questions related to resource utilization in programs, including but not limited to questions about the following:

- The relationship between observed outputs, outcomes and costs;

- The relative cost of inputs;

- The reasonableness of the cost of outputs and outcomes in light of contextual factors; and

- Reasonableness of and alternatives to existing resource utilization approaches.

Performance Is Greater Than the Sum of its Parts

The process of arriving at clear and valid conclusions on program performance involves not only an analysis leading to findings on CI4 and CI5 taken separately, but also an analysis of the relationships between them (e.g., how effectiveness varies in relation to efficiency and/or economy). Further, it is important to note that these conclusions will need to be informed and contextualized by findings on the relevance of the program through CI1 to CI3, by other contextual factors, or by findings concerning alternative approaches to achieving the same results, for example:

- Programs that are determined to be a high priority for the government or that address a significant need of Canadians may be implemented on timelines or under other conditions that affect the program's demonstration of efficiency or economy;

- Unexpected shifts in the international or economic climate may have an impact on the cost of resources being used by the program; and

- Alternative delivery models may arise in response to new technologies that may be more efficient than the delivery model used in the current program.

Evaluators will need to undertake these evaluative assessments in a manner that is both credible and calibrated to the risks associated with the program.

Appendix C: Program Readiness for Assessment of Core Issue 5

The assessment of the degree to which a program is ready for assessment of its economy and efficiency is largely based on an assessment of the program logic and theory, and the availability, accessibility and formatting of data to inform the assessment. The checklist in Table C1 has been designed to assist evaluators in working with program managers and financial managers to determine strengths and gaps in the readiness of the program for an assessment of CI5. Completing this checklist well in advance of evaluations will allow evaluators to alert program managers about gaps in their performance measurement system for supporting evaluations. This checklist can also be used by program managers and financial managers to inform the development and implementation of their performance measurement strategy.

| Requirement | Low Readiness | Medium Readiness | High Readiness |

|---|---|---|---|

| Efficiency (Allocative and Operational) and Economy | |||

| Program has a clearly defined logic model | |||

| Program outlined its program theory as part of its logic modelling exercise | |||

| Program has developed and implemented its performance measurement strategy | |||

| Cost objects are clearly linked to appropriate activities, outputs and/or outcomes (and/or entire results chains or service lines) | |||

| Operational Efficiency-Specific Readiness | |||

| Program has operational plans with clearly defined timelines and implementation targets | |||

| Implementation progress can be tracked (e.g., through action/business plans and meeting minutes that link back to operational plans) | |||

| Costs can be associated with each output | |||

| Economy-Specific Readiness | |||

| Cost objects are associated with clear targets | |||

| Costs are appropriately and consistently assigned or allocated to cost objects | |||

| Program has reliable, regular reporting on costs, including time use and acquisitions | |||

Rating Scale

- Low readiness:

- The requirement is not in place (e.g., the program does not have a clear logic model, cost objectives are not associated with clear targets).

- Medium readiness:

- The requirement is partially in place (e.g., costs can be associated with some outputs).

- High readiness:

- The requirement is fully in place (e.g., cost objects are all clearly linked to appropriate activities, outputs or outcomes).

Appendix D: Roles and Responsibilities in the Assessment of Core Issue 5

The following roles and responsibilities have been developed to assist evaluators (including departmental heads of evaluation) in communicating with program managers and financial managers about needs, roles and responsibilities for the assessment of Core Issue 5 (CI5).

Program managers, financial managers and heads of evaluation / evaluation managers all have key roles to play in ensuring that a program is ready to be assessed in terms of CI5. These roles begin at the design stage of a program and continue throughout its existence.

Given that the roles and responsibilities of program managers, financial managers and heads of evaluation / evaluation managers are closely dependant on one another, tools—such as the performance measurement (PM) strategy, evaluation strategy, evaluation framework and the Annual Report on the State of Performance Measurement—are important platforms that provide these three key parties the opportunity to interact regularly concerning evaluation and performance measurement needs.

Program Managers

Under the Directive on the Evaluation Function (Canada, 2009a, section 6.2.1), program managers are responsible for developing, updating and implementing PM strategies for their programs.14 These PM strategies include program descriptions, logic models (and related program theories), clear performance measures, and evaluation strategies.15 For new programs, PM strategies should be developed at the design stage of the program. For ongoing programs for which no PM strategy exists, one should be developed in a timely manner that ensures that data will be available to support program monitoring and evaluation activities. In developing a PM strategy, program managers will need to do the following:

- Work closely with financial managers to ensure that systems for tracking financial expenditures can support an assessment of the efficiency and economy of a program and are appropriate for the relative complexity, materiality and risks associated with the program; and

- Consult with the head of evaluation on the development of their PM strategy to ensure that it will effectively support program evaluations (Directive on the Evaluation Function, Canada, 2009a, section 6.2.3).

Financial Managers

Financial managers play an important role in the following:

- Helping, as outlined in the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat Guide to Costing (2008), to identify appropriate cost objects that are clearly aligned with program activities, outputs or immediate outcomes (i.e., the results chains or service lines) that will support an assessment of efficiency and economy; and

- The operationalization of ongoing financial tracking and the subsequent provision of data to support monitoring and evaluation.

As already noted, financial managers will need to work closely with both program managers and heads of evaluation, particularly at the design stage of the program, to ensure that the approach to collecting and tracking financial data will be effective in supporting an evaluation.

Heads of Evaluation

Heads of evaluation are responsible for “reviewing and providing advice on the performance measurement strategies for all new and ongoing direct program spending, including all ongoing programs of grants and contributions, to ensure that they effectively support an evaluation of relevance and performance” (Directive on the Evaluation Function, Canada, 2009a, section 6.1.4). Further, heads of evaluation, or evaluation managers selected by them, are responsible for developing evaluation approaches that meet the requirements outlined in the Policy on Evaluation and its related documents.16 In cases where programs are less ready in terms of the availability of data, heads of evaluation will need to work with program managers and financial managers to develop strategies (e.g., retroactive cost assignment/allocation, staff surveys, process maps, management reviews) that can help support the assessment of efficiency and economy. Finally, heads of evaluation are responsible for “submitting to the Departmental Evaluation Committee an annual report on the state of performance measurement of programs in support of evaluation” (Directive on the Evaluation Function, Canada, 2009a, section 6.1.4). It is recommended that this report include an assessment of the collection of both financial and non-financial data to support effective evaluation.

Appendix E: Optimization of Inputs and Outputs

In evaluations of federal programs where operational efficiency analysis and economy analysis are used as approaches to assessing CI5, the focus of analysis is not strictly on the cost per unit of output or input. Rather, the analysis also needs to consider the degree to which outputs or inputs have been optimized.

Inputs or outputs can be said to have been optimized when certain factors, including the cost, quantity, quality, timeliness and appropriateness of the outputs produced or inputs acquired, have been balanced by program managers in a defensibly rational manner in light of the program's theory (i.e., assumptions, risks, mechanisms and context), logic, relevance (i.e., CI1, CI2 and CI3) and observed results (i.e., CI4). Evaluators need to further consider how the balancing of attributes affected the achievement of outcomes. Table E1 provides more details on the input and output optimization factors.

| Attribute | Outputs (Efficiency) | Inputs (Economy) |

|---|---|---|

| Cost | The cost of outputs and the degree to which the program has sought to minimize this cost (while maintaining appropriate quality, quantity and timeliness) | The cost of inputs and the degree to which the program has sought to minimize these (while maintaining appropriate quality, quantity and timeliness) |

| Quality | The degree to which outputs are adequate to produce the expected outcomes | The degree to which inputs are adequate to produce the expected outputs and outcomes |

| Quantity | The degree to which sufficient outputs have been produced to support achievement of expected outcomes | The degree to which sufficient inputs have been acquired to produce the expected outputs and outcomes |

| Timeliness | The degree to which outputs have been produced at appropriate points in the program | The degree to which inputs have been procured or otherwise made available at appropriate points in the program |

| Appropriateness | The degree to which the outputs were apt to support the achievement of expected outcomes | The degree to which the inputs were apt to support the production of outputs and outcomes were acquired |

Appendix F: Operational Efficiency Analysis

Operational efficiency is largely concerned with the question of how resources are being converted into outputs that support the achievement of intended outcomes. Operational efficiency analysis (OEA) does not constitute a single analytical approach or a formalized process such as cost-benefit analysis. Rather, OEA refers to a range of analytical approaches, models and methods that may be used (where warranted and in various combinations) to assess the efficiency of programs in a detailed manner. This, among other things, allows evaluators to:

- Calibrate evaluations by undertaking a deeper analysis of specific results chains, outputs or activities that are deemed to be higher-risk; and/or

- Undertake assessments of efficiency for programs that are not at a point in their life cycle or maturity where a full cost-effectiveness or cost-benefit analysis is warranted (e.g., formative evaluations).

OEA Lines of Inquiry

There are several lines of inquiry that can be pursued in assessing operational efficiency. These can be divided into broad categories, including (but not limited to) the following:

- Outputs in terms of their costs;

- Qualitative dimensions of program processes and outputs (including questions related to output optimization and program management decision making regarding resource utilization); and

- Those concerning the context, risks and assumptions for the production of outputs that support outcome achievement.

Table F1 provides sample questions that might be explored when undertaking OEA in an evaluation.

| Line of Inquiry | Sample Questions |

|---|---|

| Output costs |

|

| Qualitative dimensions of operational efficiency |

|

| Context, risks and assumptions concerning the production of outputs |

|

Appendix G: Economy Analysis

Economy analysis is largely concerned with the extent to which resource use has been minimized in the implementation and delivery of programs. In broad terms, this may include (but is not limited to) assessments of:

- The cost of specific inputs in relation to comparators (e.g., planned costs, benchmarks, alternatives);

- The optimization of inputs; or

- The effects of the program context on input optimization and input selection by program management.

Economy analysis (EA) does not constitute a single analytical approach or a formalized process such as cost-benefit analysis. Rather, EA refers to a range of analytical approaches, models and methods that may be used (where warranted and in various combinations) to assess the economy of programs in a detailed manner. This, among other things, allows evaluators to calibrate evaluations by undertaking targeted analyses of specific inputs.

EA Lines of Inquiry

An evaluation can pursue several lines of inquiry in assessing economy. These can be divided into categories, including (but not limited to):

- Those that directly address inputs in terms of their costs;

- Those that address optimization of inputs and program management decision making regarding input acquisition and utilization for output production; and

- Those concerning the context, risks and assumptions for the acquisition of inputs.

Table G1 provides sample questions that might be explored when undertaking EA in an evaluation.

| Line of Inquiry | Sample Questions |

|---|---|

| Input costs |

|

| Input optimization |

|

| Context, risks and assumptions concerning the acquisition of inputs |

|

Appendix H: Bibliography

- Aucoin, P. (2005). Decision-making in government: The role of program evaluation. Ottawa: Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat.

- Bhatta, G. (2006). International dictionary of public management and governance. New York: M.E. Sharpe Inc.

- Brent, Robert J. (2002). A simple method for converting a cost-effectiveness analysis into a cost-benefit analysis with an application to state mental health expenditures. Public Finance Review, 30(2): 144–160.

- Canada. (1977). Treasury Board. Policy circular on “Evaluation of programs by departments and agencies.” Ottawa: Treasury Board.

- Canada. (1992). Treasury Board. Evaluation and audit. In Treasury Board Manual. Ottawa: Treasury Board.

- Canada. (1994). Treasury Board. Review, internal audit and evaluation. In Treasury Board Manual. Ottawa: Treasury Board.

- Canada. (2001). Treasury Board. Evaluation policy. Ottawa: Treasury Board.

- Canada. (2004a). Canadian International Development Agency. CIDA evaluation guide. Ottawa: Canadian International Development Agency.

- Canada. (2004b). Office of the Auditor General of Canada. Performance audit manual. Ottawa: Ministry of Public Works and Government Services.

- Canada. (2008). Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat. Guide to costing. Ottawa: Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat.

- Canada. (2009a). Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat. Directive on the evaluation function. Ottawa: Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat.

- Canada. (2009b). Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat. Instructions to departments for developing a management, resources and results structure. Ottawa: Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat.

- Canada. (2009c). Treasury Board. Policy on evaluation. Ottawa: Treasury Board.

- Canada. (2009d). Treasury Board. Policy on internal audit. Ottawa: Treasury Board.

- Canada. (2009e). Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat. Standard on evaluation for the Government of Canada. Ottawa: Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat.

- Canada. (2010). Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat. Supporting effective evaluations: A guide to developing performance measurement strategies. Ottawa: Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat.

- Chen, H. T. (2005). Practical program evaluation: Assessing and improving planning, implementation, and effectiveness. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- de Salazar, L. et al. (2007). Guide to economic evaluation in health promotion. Washington, D. C.: Pan American Health Organization.

- Earl, S., Carden, F. & Smutylo, T. (2001). Outcome mapping: Building learning and reflection into development programs. Ottawa: International Development Research Centre.

- Eureval/Centre for European Evaluation Expertise. (2006). Study on the use of cost-effectiveness analysis in EC's evaluations. Eureval/European Commission.

- Griffiths, B., Emery, C. & Akehurst, R. (1995). Economic evaluation in rheumatology: A necessity for clinical studies. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases, 54(11): 863–864.

- Herman, P. M. et al. (2009). Are cost-inclusive evaluations worth the effort? Evaluation and Program Planning, 1(32:1): 55–61.

- Levin, Henry M. & McEwan, Patrick J. (2001). Cost-effectiveness analysis: Methods and applications. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Inc. (second edition).

- Lusthaus, C. et al. (2002). Organizational assessment: A framework for improving performance. Ottawa: International Development Research Centre.

- McDavid, J. C. & Hawthorn, L. R. L. (2006). Program evaluation and performance measurement: An introduction to practice. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Inc.

- Nagel, S. S., ed. (2002). Handbook of public policy evaluation. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Inc.

- Newman, I. & Benz, C. R. (1998). Qualitative and quantitative research methodology: Exploring the interactive continuum, Southern Illinois University.

- O'Connor, Cailin, Small, Stephen A. & Cooney, Siobhan, M. (2007). Program fidelity and adaptation: Meeting local needs without compromising program effectiveness. What works, Wisconsin—Research to Practice Series. Issue 4. University of Wisconsin–Madison and University of Wisconsin–Extension.

- Palenberg, M. et al. (2011). Tools and methods for evaluating the efficiency of development interventions. Berlin: Federal Ministry for Economic Cooperation and Development.

- Rogers, Patricia J., Stevens, Kaye & Boymal, Jonathan. (February 2009). Qualitative cost-benefit evaluation of complex, emergent programs. Evaluation and program planning, Elsevier, 32(1): 83–90.

- Shaw, I., Greene, J. & Mark, M. (2006). The Sage handbook of evaluation, Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications Inc.

- van den Bergh, J. C. J. M. (2004). Optimal climate policy is a utopia: From quantitative to qualitative cost-benefit analysis. Ecological Economics 48(1): 385–393.

- Weiss, C. H. (Ed.). (1977). Using social research in public policy making. Lexington, MA: D.C. Heath.

- White, Jennifer L. et al. (). Cost analysis in educational decision making: Approaches, procedures, and case examples. WCER Working Paper No. 2005-1. Wisconsin Centre for Education Research.

- Yates, B. T. (1998). Formative evaluation of costs, cost-effectiveness, and cost-benefit: Toward cost → procedure → process → outcome analysis. In Bickman, L. & Rog, D. J. (Eds.). Handbook of applied social research methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage: 285–314.