Annual Report on the Public Servants Disclosure Protection Act 2020 to 2021

The Annual Report on the Public Servants Disclosure Protection Act provides an overview of the activities respecting disclosures made in federal public sector organizations.

On this page

- Message from the Chief Human Resources Officer

- About this report

- Office of the Chief Human Resources Officer: activities to support ethical workplaces

- Education and awareness-raising activities

- Public Service Employee Survey: ethics in the workplace

- Organizational disclosure activity

- Appendix A: summary of organizational activity related to disclosures under the Public Servants Disclosure Protection Act

- Appendix B: Public Service Employee Survey – ethics in the workplace

- Appendix C: disclosure process under the Act

- Appendix D: key terms

Message from the Chief Human Resources Officer

It is my pleasure to present the 14th annual report on the Public Servants Disclosure Protection Act to the President of the Treasury Board of Canada for tabling in Parliament.

The Public Servants Disclosure Protection Act promotes trust in the public sector by fostering an environment where public servants feel that they can come forward with enquiries or allegations about possible wrongdoing. This report provides information on activities related to such disclosures in federal public sector organizations and includes details on the actions taken by organizations in response to allegations of wrongdoing.

This year’s findings from the Public Service Employee Survey show that, overall, public servants perceive their workplace to be more ethical than in the previous year, suggesting that ongoing education and awareness activities are having an impact. While a positive trend, there is still more work to do as this is not evenly distributed across the public service.

My office has continued to support federal organizations in creating and sustaining an ethical workplace where employees feel comfortable coming forward with disclosures of wrongdoing. With the implementation of the new Policy on People Management and its associated directives, including the Directive on Conflict of Interest, deputy heads’ accountability to prevent and respond to matters that impact the ethical culture of the workplace has been reinforced. The creation of the Centre on Diversity and Inclusion in September 2020 and continued work to prevent harassment and discrimination have helped to create healthy workplaces that support mental health and are part of our ongoing support to deputy heads and leaders at all levels.

Through these efforts, we will continue to foster an ethical workplace culture that is respectful, healthy, diverse and inclusive. At the same time, we will continue to raise awareness among public servants about the disclosure process available to them, including protections against acts of reprisal so that public servants feel safe and supported in reporting possible wrongdoing now and in the future.

Original signed by

Christine Donoghue

Chief Human Resources Officer

Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat

About this report

This annual report on the Public Servants Disclosure Protection Act (the Act) covers the period from April 1, 2020, to March 31, 2021. The report contains information on disclosure activities in the federal public sector, which includes departments, agencies, and Crown corporations as defined in section 2 of the Act. The report also contains information on the activities the Office of the Chief Human Resources Officer (OCHRO) has undertaken over the same period to foster an ethical workplace culture.

Every organization subject to the Act is required to designate a senior officer for internal disclosure who is responsible for addressing disclosures made under the Act and for establishing internal procedures to manage disclosures. Alternatively, organizations that are too small to designate a senior officer or establish their own internal procedures can have disclosures handled directly by the Public Sector Integrity Commissioner of Canada (PSIC). This report does not contain information on disclosures or reprisal complaints made to the PSIC, other recourse mechanisms or anonymous disclosures.

Office of the Chief Human Resources Officer: activities to support ethical workplaces

In this section

Senior officers and communities of practice

To better equip senior officers for disclosure of wrongdoing and managers to support public servants in their organizations, OCHRO continued to develop and provide them with guides, tools and advice. OCHRO also continued to deliver one-on-one orientation sessions for newly designated senior officers for disclosure of wrongdoing and their teams to ensure that they understand their accountabilities under the Act.

In addition, OCHRO continued to facilitate a government-wide community of practice to share promising strategies and discussions of recent developments in the fields of values and ethics, disclosure of wrongdoing, reprisal protections, and conflict of interest resolution. This facilitation included hosting nine meetings of the Interdepartmental Network on Values and Ethics and supporting six meetings of the Internal Disclosure Working Group.

In 2020, OCHRO published an evergreen guidebook for departments to support the delivery of programs and services to Canadians during a gradual, safe, and sustainable easing of COVID-19 restrictions. Additionally, we provided information online to support public servants’ physical and mental health and to help public servants adapt to working remotely. While these supports did not provide specific advice on disclosure, they contributed to supporting a healthy and ethical workplace. OCHRO will continue to monitor the effects of remote work and adapt its support accordingly.

Policy on People Management and Directive on Conflict of Interest

The new Policy on People Management and the accompanying Directive on Conflict of Interest came into effect on April 1, 2020. To support deputy heads in their obligations to prevent and resolve conflicts of interest and conflicts of duties, OCHRO developed and distributed several guides and held remote awareness sessions on these issues for values and ethics practitioners and designated senior officials.

The new policy and directive complement chief executives’ obligations, under the Values and Ethics Code for the Public Sector, to ensure that public servants can obtain appropriate advice on ethical issues within their organization.

Diversity and inclusion in the workplace

A public service that is diverse and inclusive is important for a workplace culture where public servants from equity-seeking groups feel comfortable in disclosing wrongdoing.

The Centre on Diversity and Inclusion (CDI) was established in September 2020 to help deputy heads and leaders at all levels create a more inclusive and diverse public service. CDI initiated the development of programs and activities that focus on enterprise-wide solutions by partnering with employment equity groups, equity-seeking groups and stakeholders. Activities included a mentorship program to better support leadership development; a community of practice for designated senior officials for employment equity, diversity and inclusion; and a platform for public servants from diverse groups to share lived experiences.

In 2020–21, OCHRO conducted several activities that contributed to the modernization of the employment equity regime and public service attitudes toward diversity and inclusion. These activities included providing support for the development and adoption of amendments to the Public Service Employment Act. The activities aimed to remove or reduce systemic barriers and challenges faced by equity-seeking groups, and to engage with key federal departments on modernizing the collection and analysis of employment equity data to advance discussions on self-identification.

Preventing and resolving harassment and violence in the workplace

A workplace that is free of harassment and violence is an essential part of an environment where employees feel safe to come forward with disclosures of wrongdoing.

Employment and Social Development Canada’s (ESDC’s) Labour Program developed new regulations in 2019–20 to better protect employees from harassment and violence in federally regulated workplaces. To ensure that harassment and violence are not tolerated, condoned or ignored in the public service, we worked with bargaining agents and released a new Directive on the Prevention and Resolution of Workplace Harassment and Violence in December 2020.

OCHRO also worked with the Canada School of Public Service (CSPS) and the Canadian Centre for Occupational Health and Safety to support the development of three workplace harassment and violence prevention courses specifically for public service employees, supervisors, managers, departmental occupational health and safety committee members, and designated recipients.Footnote 1

Mental health in the workplace

Having the right workplace conditions to support mental health and wellness generates higher levels of employee engagement and adds to public servants’ confidence in coming forward with concerns about wrongdoing.

OCHRO’s Centre of Expertise on Mental Health in the Workplace supports federal organizations in aligning with the National Standard of Canada: Psychological Health and Safety in the Workplace and advances the Federal Public Service Workplace Mental Health Strategy.

Departmental “pulse-check” survey results over the past year indicated that working from home is having varying mental health–related impacts. Some respondents reported positive impacts and a healthier work environment, whereas others reported negative impacts due to feelings of anxiety in the face of uncertainty and loneliness. Results of the 2020 Public Service Employee Survey (PSES) showed overall improvements in mental health awareness, satisfaction with actions taken by managers to support employees’ mental health, and incidents of harassment and violence. At the same time, stresses related to workload, social isolation, long hours, and balancing family responsibilities have increased and are now the main factors affecting the mental health of the public service.

In 2020, the Centre of Expertise created a curated suite of mental health resources for public servants. The suite provides tools for employees who face challenges while working remotely, such as balancing family life and caregiving with work.

International engagement

OCHRO continues to collaborate with international organizations on global integrity and anti-corruption efforts. These international engagements help OCHRO to stay up to date on global activities, research, and best practices in the areas of integrity, anti-corruption and disclosure regimes. The engagements also allow OCHRO to continue to share and promote Canada’s successful strategies, including:

- Representing Canada on the Organisation of Economic Co-operation and Development’s (OECD’s) Working Party of Senior Public Integrity Officials and contributing to the development of a Public Integrity Maturity Model and best practice tools to complement the OECD Public Integrity Handbook.

- Providing strategic integrity expertise to Global Affairs Canada as the Canadian representative in the OECD Working Group on Bribery, and the anti-corruption working groups at the United Nations and the G20. OCHRO is also involved in ongoing international development projects, including Strengthening Ethics and Integrity in South Africa and Modernizing the Peruvian Public Service.

- Providing input on Canada’s anti-corruption efforts to the Department of Justice Canada as the Canadian representative at the Organization of American States’ Follow-Up Mechanism for the Implementation of the Inter-American Convention Against Corruption.

Education and awareness-raising activities

In this section

Enterprise-wide

Complementary to OCHRO’s activities to promote ethical practices and a positive environment for disclosing wrongdoing across the public service, the CSPS provides enterprise-wide training to promote values and ethics in the workplace.

In 2021, the CSPS saw a 25% increase in the completion of the values and ethics courses they offer, compared to 2020:

- 24,967 public servants completed the mandatory CSPS course “Values and Ethics Foundations for Employees” (C255)

- 1,460 managers completed the course “Values and Ethics Foundations for Managers” (C355)

Federal public sector organizations

As in previous years, federal public sector organizations acted to raise awareness among public servants, provide education about the disclosure process and support those public servants who wish to make a disclosure. Examples of activities included:

- creating dedicated intranet sites and postings to raise awareness of the disclosure process

- developing posters to promote an ethics hotline

- organizing annual reviews of codes of conduct and the organization’s disclosure procedures

- providing values and ethics training and other self-paced online training products

- sending all-staff emails and providing education to new employees

- hosting virtual townhalls, all-staff meetings, panels and discussions

- creating podcasts

- promoting third-party reporting and the completion of the PSES

Some specific examples of how some organizations worked to create awareness of the disclosure process and educate public servants in 2020–21 include:

- Correctional Service Canada’s revamp of the disclosure pages on its intranet to ensure clear and relevant information for staff about their Office of Internal Disclosure, the disclosure process, and the roles and responsibilities of both staff and management in relation to the Act

- ESDC’s posting of both a poster entitled “Is something not looking right at work?” and a podcast entitled “Adapting Our Priorities to the New Normal” on their social media accounts to raise awareness and promote best practices in relation to ESDC’s Code of Conduct

- Environment and Climate Change Canada’s issuance of awareness messages, promotion of an evergreen recourse placemat, and use of mandatory training to ensure awareness and education about the Act, disclosure of wrongdoing, confidentiality and reprisal protections

- The International Development Research Centre’s promotion of awareness about the Act by posting messages about disclosure of wrongdoing on television screens in the office and updating internal policy and disclosure procedures to align with legislation and best practices

Overall, while the CSPS saw an increase in the number of public servants who completed their courses, individual federal public sector organizations reported that they provided fewer complementary internal values and ethics training activities to employees compared to 2019–20, with some citing the pandemic as a reason for the reduction in training activity.

In addition to the CSPS training, about one in five organizations reported:

- offering self-paced online modules and training on values and ethics and related issues or on the Act

- providing mandatory stand-alone organization-specific training in these areas

Public Service Employee Survey: ethics in the workplace

In this section

Each year, OCHRO conducts the Public Service Employee Survey (PSES), which allows the public service to gauge what it is doing well and what it could be doing better to ensure the continual improvement of people management practices in government.Footnote 2

The survey includes three questions on public servants’ perception of an ethical environment in their workplace. The results provide insights into how public servants are being equipped to address issues, such as values and ethics dilemmas. In addition, the results can be disaggregated, including based on demographics, region or organization.Footnote 3

Results for the public service as a whole

The 2020 PSES results show a more positive perception of ethics in the workplace for the public service as a whole compared to recent years:

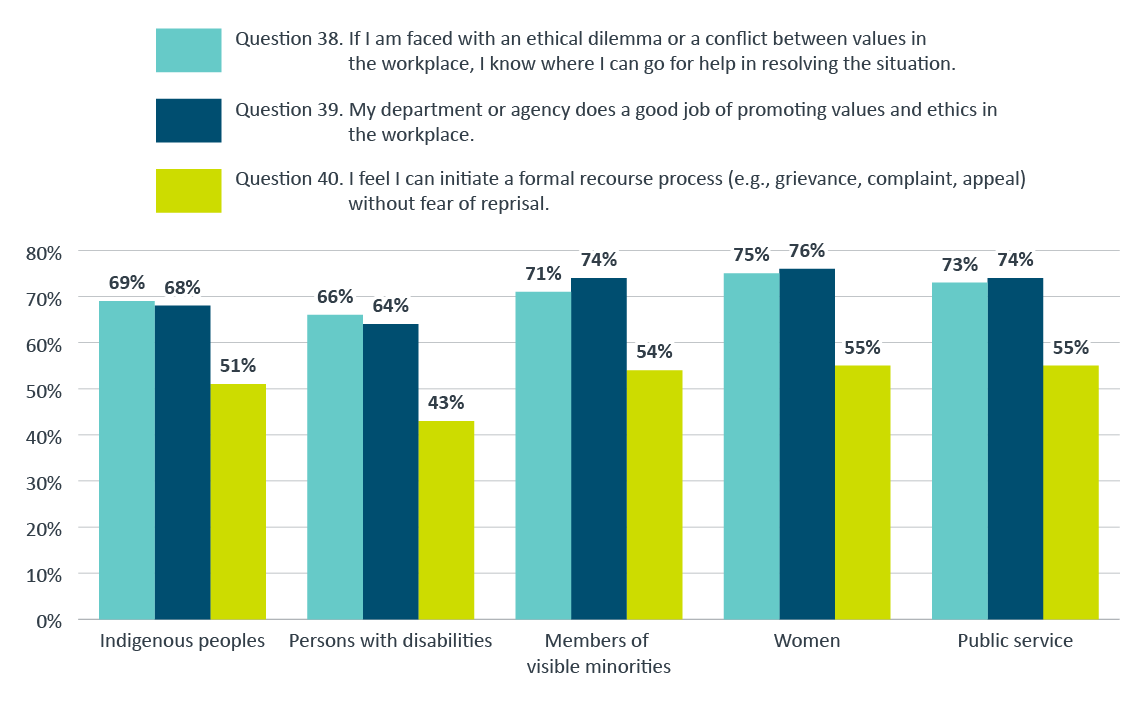

- 74% of public servants indicated that they felt their department or agency does a good job of promoting values and ethics in the workplace, up from 69% in both 2019 and 2018.Footnote 4

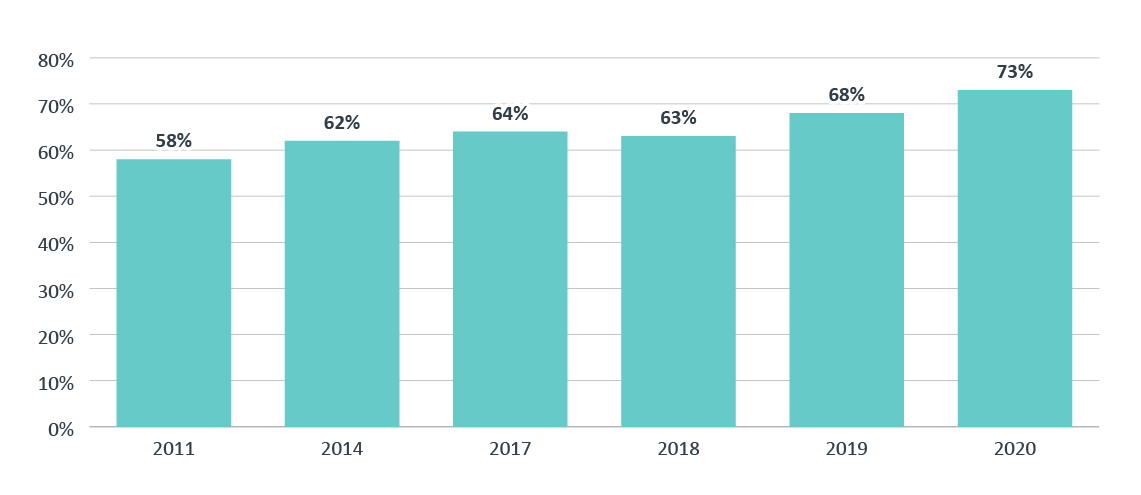

- 73% of public servants responded that senior managers in their department or agency lead by example in ethical behaviour, up from 68% in 2019. This result reflects a general upward trend over the last five PSES surveys, from 58% in 2011.

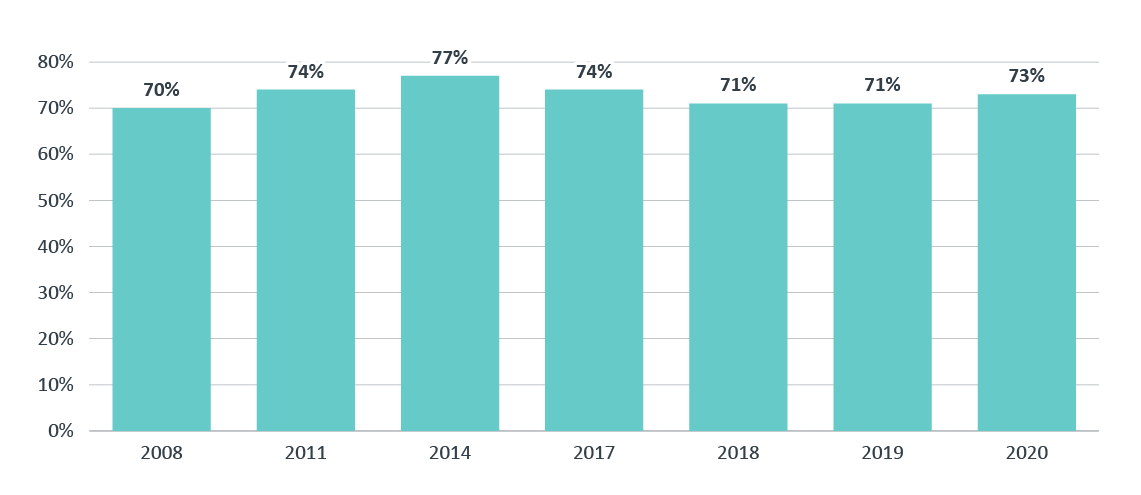

- 73% of public servants indicated that they would know where to go for help in resolving the situation if faced with an ethical dilemma or a conflict between values in the workplace, up from 71% in 2019. It is too early to signal a reverse in the downward trend observed since this indicator reached a peak of 77% in 2014.

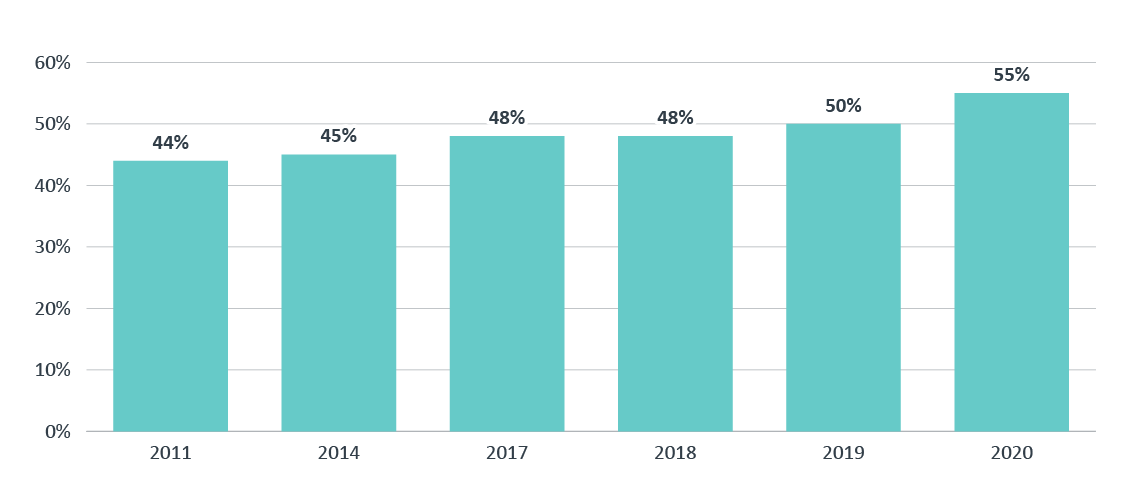

- 55% of public servants indicated they felt they could initiate a formal recourse process (for example, grievance, complaint, appeal) without fear of reprisal, up from 50% in 2019. While this indicator has trended upwards since 2011, there is still room for improvement.

Disaggregated results

The results of the PSES ethics questions were analyzed by disaggregating the data by gender, province and territory, employment equity group, employment community, and organizational mandate, to better understand the federal public service values and ethics landscape. This analysis provided insights into areas where there are noticeable differences in the views of specific communities of public servants compared to those of other groups or the public service overall.Footnote 5 For example:

- Employees who self-identify as a person with a disability, an Indigenous person or as gender-diverse reported nearly double the rates of harassment and violence and double to almost triple the rates of discrimination compared to the public service as a whole. Persons belonging to a visible minority reported higher rates of discrimination compared to the public service as a whole. These experiences may impact decisions to pursue formal recourse processes.

- Employees in British Columbia, Alberta and Saskatchewan generally had lower rates of positivity about the ethical environment in their workplace compared to employees in other locations. There has been some improvement in British Columbia and Alberta compared to 2019–20.

- Employees in the security employment community and in security and military organizations had lower rates of positivity about the ethical environment in their workplace compared to the public service as a whole. Of note, only 47% of employees in the security community and 62% of employees in security and military organizations responded positively when asked whether senior managers in their departments or agencies lead by example in ethical behaviour, compared to 73% for the public service as a whole.

- Only 41% of employees working outside of Canada were confident that they could initiate a formal recourse process without fear of reprisal versus 55% for the public service as a whole. Only 64% of this community responded positively when asked whether senior managers in their departments or agencies lead by example in ethical behaviour, compared to 73% for the public service as a whole.

- Employees working in the legal services community reported lower rates of confidence that they could initiate a formal recourse process without fear of reprisal (46%) compared to the public service as a whole (55%).

These insights will inform OCHRO and chief executives of where targeted outreach can be concentrated in order to further promote ethical practices and a positive environment for disclosing wrongdoings in the public sector.

Organizational disclosure activity

In this section

Reported enquiries and disclosure activity

As part of continuing efforts to improve reporting on public sector disclosure activity, in 2020–21, OCHRO asked organizations to report on the number of allegations of wrongdoing received through each disclosure brought forward by public servants to their supervisor or the senior disclosure officer. OCHRO’s request reflects that a single act of disclosure may include more than one allegation of wrongdoing, as outlined in section 8 of the Act. Reporting both the number of allegations and the number of disclosures enhances clarity compared to previous reports where each allegation was counted as a separate disclosure. Appendix D contains a glossary on the key terms used in this report.

Enquiries

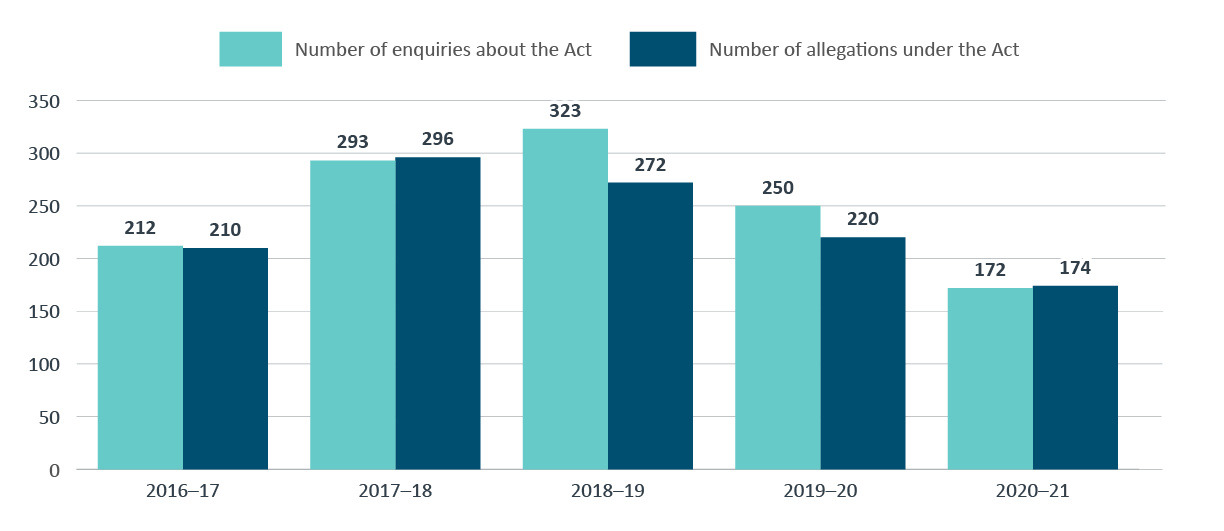

Public servants may make enquiries about the disclosure process without making a formal disclosure or allegation. The number of enquiries about the Act decreased substantially in 2020–21 to 172: the lowest number in the past five years. As shown in Figure 1, the number of enquiries and allegations show a similar trend.

Figure 1 - Text version

| Type | 2016 to 2017 | 2017 to 2018 | 2018 to 2019 | 2019 to 2020 | 2020 to 2021 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of enquiries about the Act | 212 | 293 | 323 | 250 | 172 |

| Number of allegations under the Act | 210 | 296 | 272 | 220 | 174 |

It is difficult to say precisely what is contributing to the downward trend in the number of enquiries shown in Figure 1. The trend may suggest that efforts to raise awareness of the Act, as well as other recourse mechanisms, have improved public servants’ understanding of the mechanisms available. The trend could also be a result of public servants working remotely due to COVID-19 restrictions over the past year and having fewer opportunities to observe activity that could lead to a disclosure. The trend may also be influenced by other factors beyond these, as the data does not permit a conclusion on this point.

Steps in the process of disclosing wrongdoingFootnote 6

Step 1: disclosures and allegations received

Disclosures containing one or more allegations of possible wrongdoing are received.

Step 2: allegations assessed

Allegations are assessed to determine whether they are admissible under the Act.

Step 3: allegations investigated

If the allegations are admissible, an investigation is conducted. If not, other remedial action or recourse processes are considered.

Step 4: findings and corrective measures reported

Findings are made and corrective measures are taken as appropriate.

Step 1: disclosures and allegations received

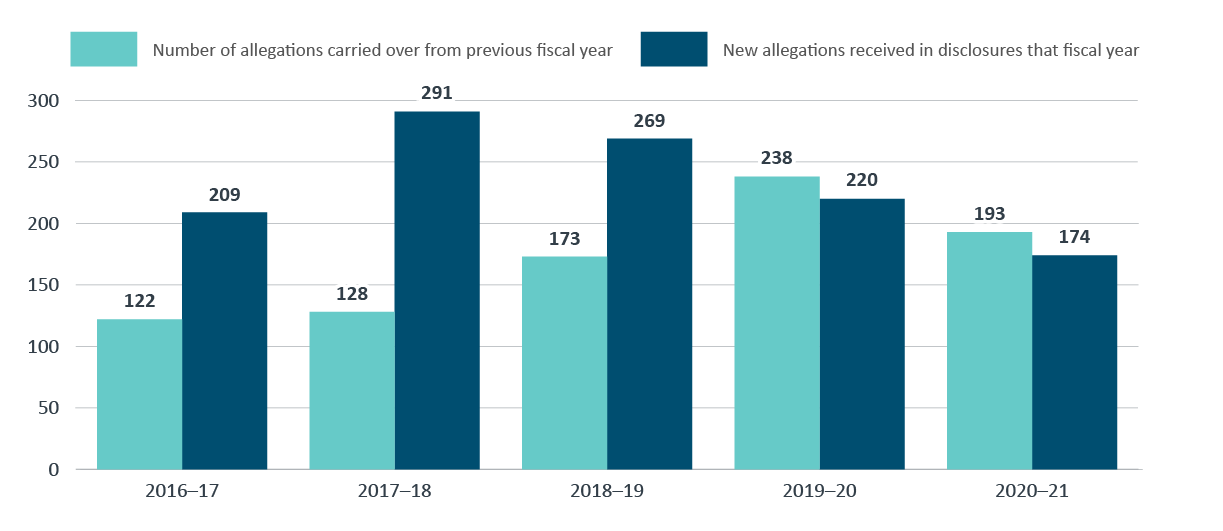

In 2020–21, 123 public servants made 101 disclosures containing 174 allegations, which is the lowest number of new allegations made in the last five years (Figure 2).Footnote 7

Figure 2 - Text version

| Type | 2016 to 2017 | 2017 to 2018 | 2018 to 2019 | 2019 to 2020 | 2020 to 2021 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of allegations carried over from previous fiscal year | 122 | 128 | 173 | 238 | 193 |

| New allegations received in disclosures that fiscal year | 209 | 291 | 269 | 220 | 174 |

There was a decrease in the number of allegations that were carried over from the previous fiscal year from 238 allegations in 2019–20 to 193 allegations in 2020–21. Of the 193 allegations carried over into 2020–21, 101 (52%) were originally received in 2019–20 and 92 (48%) were originally received in 2018–19 or earlier.

Federal public sector organizations have indicated that one barrier to being able to resolve disclosures quickly is a lack of internal investigative capacity. To address this barrier, in 2018, OCHRO put in place a National Master Standing Offer (NMSO) for investigative services, and this list of available service providers is regularly updated.

Six large organizations and one small organization used the NMSO in 2020–21. Both large and small organizations have responded positively to the NMSO. Organizations have noted, for example, that the NMSO helps them secure qualified and bilingual investigative services easily and quickly. This is particularly true for organizations that don’t have internal investigative capacity. A small number of organizations indicated that the NMSO has had no impact on their investigative capacity because they have their own investigators on staff or because the NMSO does not apply, which is the case for Crown corporations.

Step 2: allegations assessed

Each allegation is assessed by the organization’s senior officer for internal disclosure to determine whether the allegation meets the definition of wrongdoing and warrants further action.

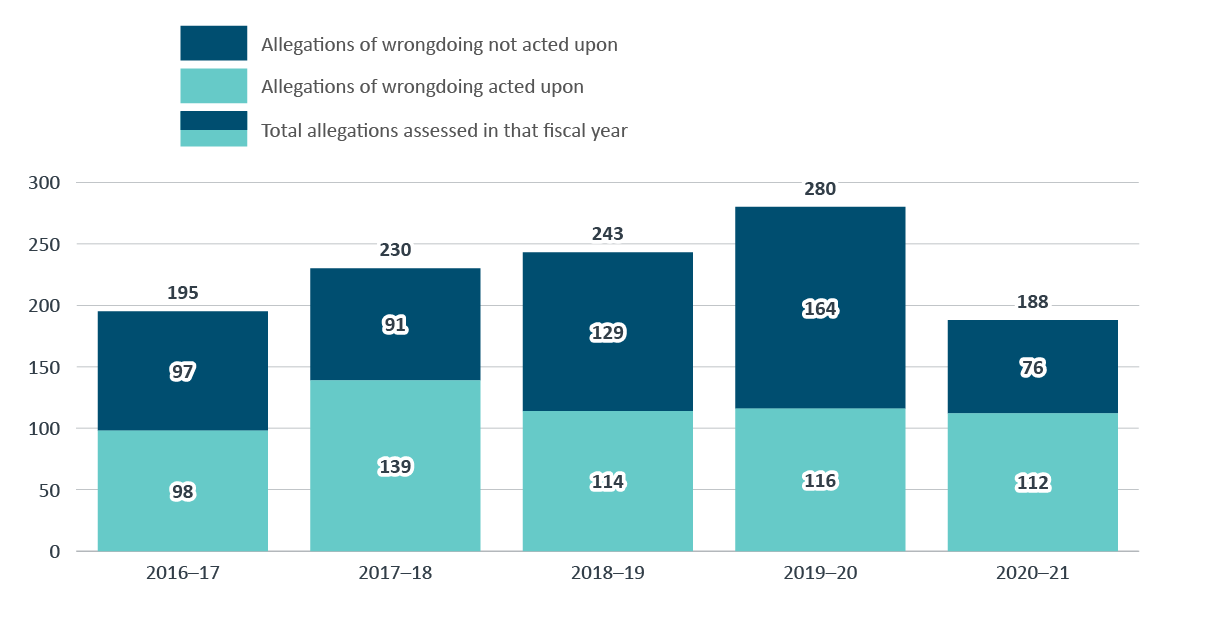

In 2020–21, 51% of total allegations were assessed (188 of 367).Footnote 8 This percentage is a decrease in comparison to the upward trend in the previous four years, where the rate of assessment of allegations varied between 54% in 2017–18 and 61% in 2019–20 (Figure 3).

Of the 188 allegations assessed in 2020–21, 102 (54%) were carried over from previous years, including 65 (35%) that were received in 2019–20 and 37 (19%) that were received in 2018–19 or earlier.

Figure 3 - Text version

| Type | 2016 to 2017 | 2017 to 2018 | 2018 to 2019 | 2019 to 2020 | 2020 to 2021 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total allegations | 332 | 424 | 445 | 458 | 367 |

| Allegations assessed | 195 | 230 | 243 | 280 | 188 |

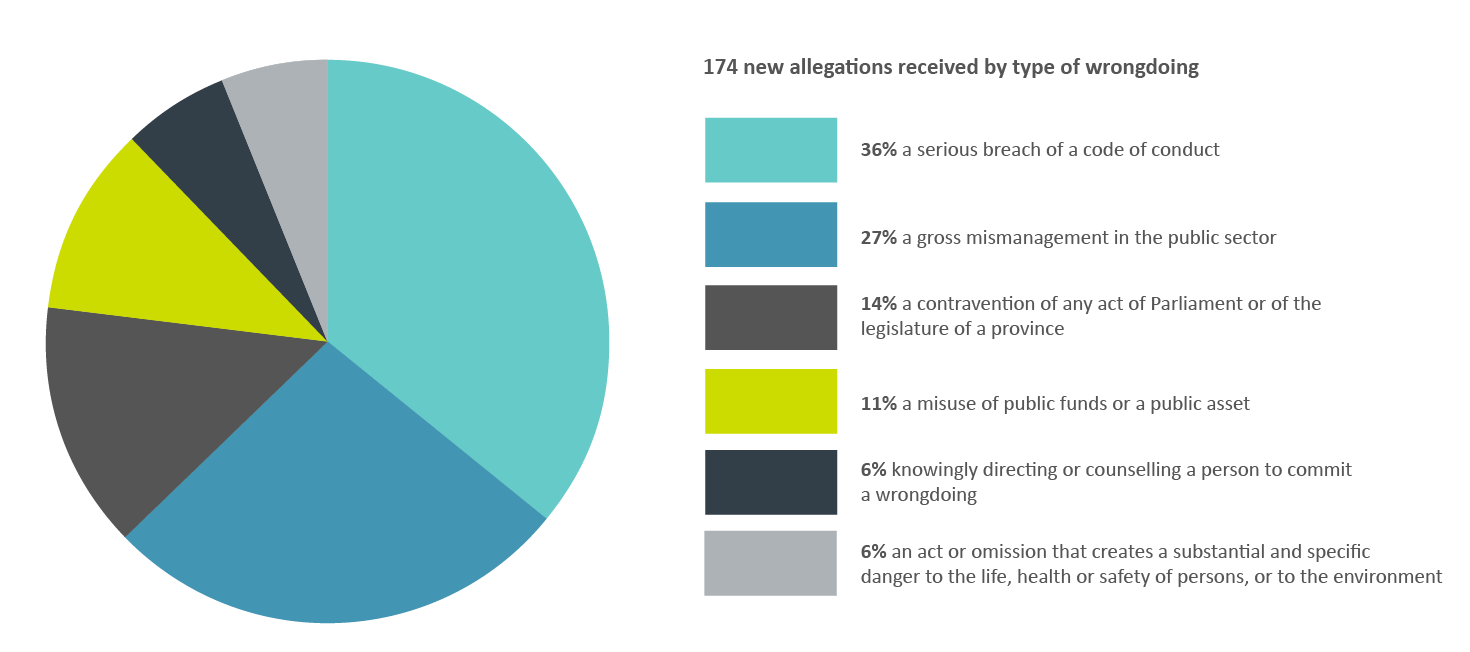

Allegations by type of wrongdoing

Compared to the previous year, the percentage of allegations about:

- a serious breach of a code of conduct decreased (from 48% in 2019–20 to 36% in 2020–21)

- a misuse of public funds or assets decreased (from 23% in 2019–20 to 11% in 2020–21)

The percentage of allegations that dealt with gross mismanagement in the public sector increased from 17% in 2019–20 to 27% in 2020–21 (Figure 4).

While the number of allegations of a serious breach of a code of conduct decreased over the last two years, it is still the most prevalent allegation of wrongdoing. This is possibly because codes of conduct include explicit standards for expected behaviours, which may make it easier for public servants to identify serious breaches.

Figure 4 - Text version

| Type | Percentage of the 174 new allegations received in 2020 to 2021 |

|---|---|

| A serious breach of a code of conduct | 36% |

| A gross mismanagement in the public sector | 27% |

| A contravention of any act of Parliament or of the legislature of a province | 14% |

| A misuse of public funds or a public asset | 11% |

| Knowingly directing or counselling a person to commit a wrongdoing | 6% |

| An act or omission that creates a substantial and specific danger to the life, health or safety of persons, or the environment | 6% |

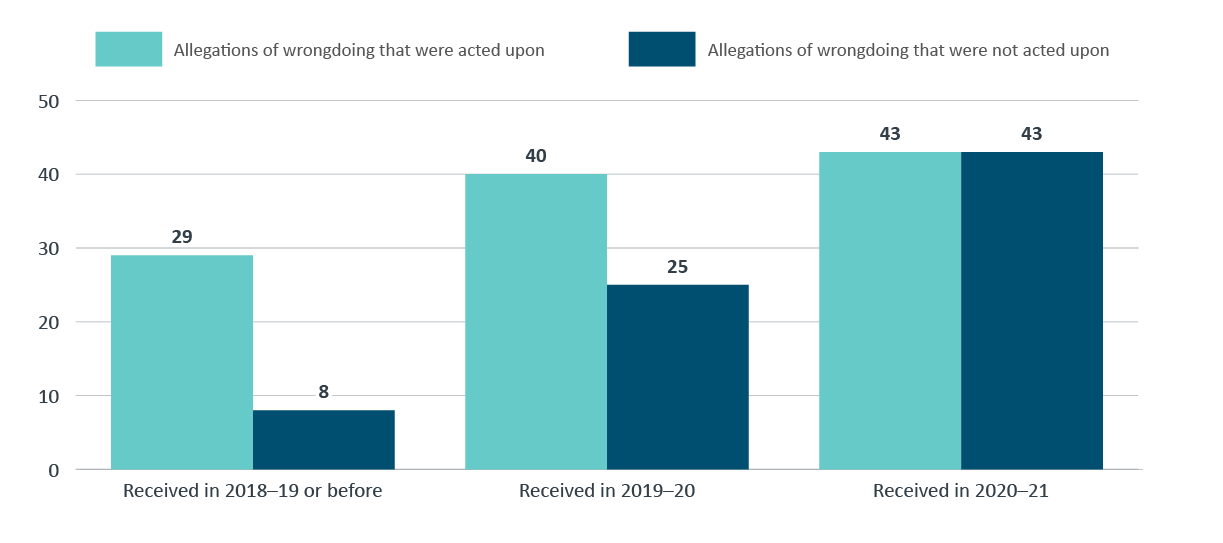

Allegations acted upon and not acted upon

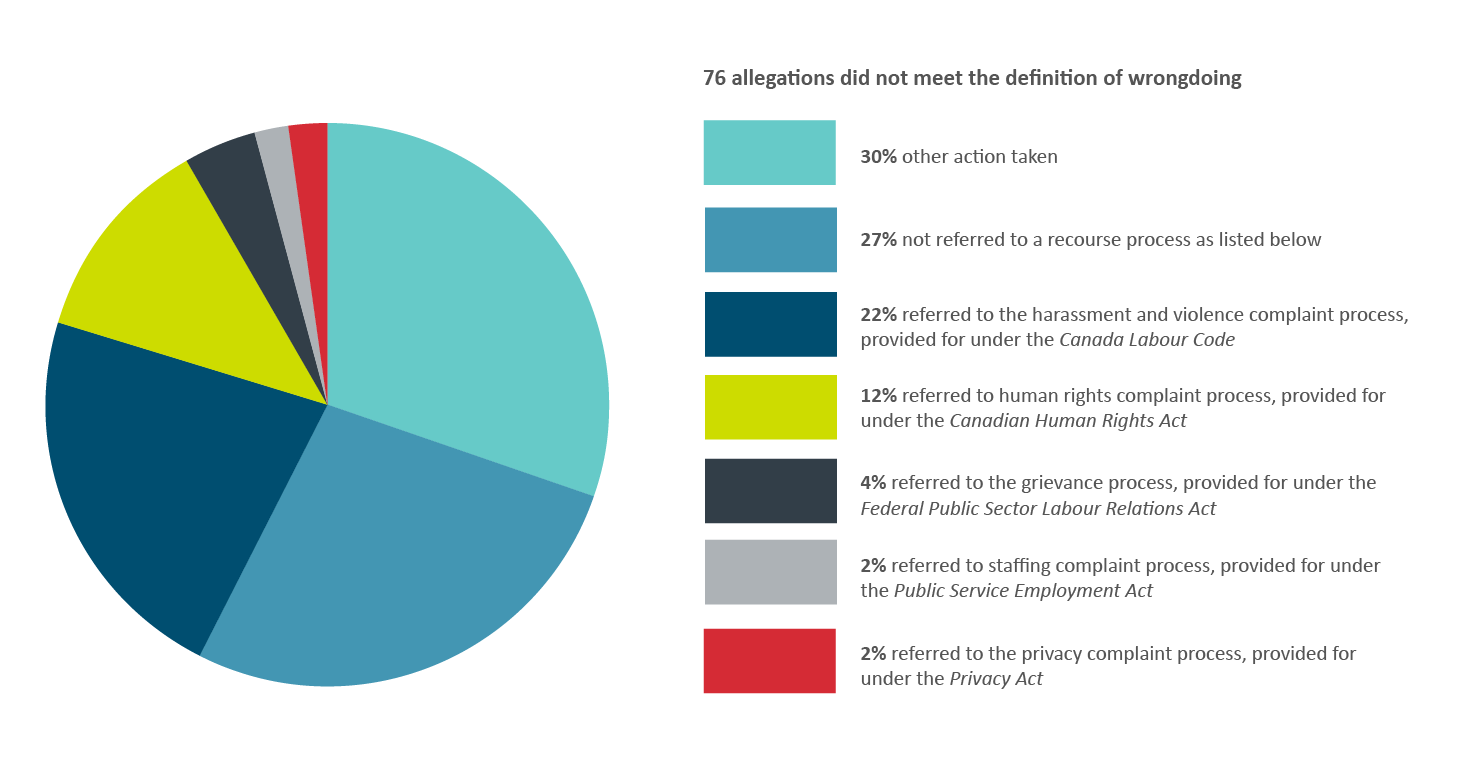

In 2020–21, of the 188 allegations assessed, 112 were found to have met the definition of wrongdoing and were acted upon under the Act. As shown in Figure 5, these 112 allegations included 43 received in 2020–21, 40 received in 2019–20, and 29 received in 2018–19 or earlier.

In addition, 76 of the 188 allegations assessed did not meet the definition of wrongdoing and were not acted upon under the Act. These 76 allegations included 43 received in 2020–21, 25 received in 2019–20, and eight received in 2018–19 or earlier.

Figure 5 - Text version

| Type | Received in 2018 to 2019 or before | Received in 2019 to 2020 | Received in 2020 to 2021 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Allegations of wrongdoing that were acted upon | 29 | 40 | 43 |

| Allegations of wrongdoing that were not acted upon | 8 | 25 | 43 |

As shown in Figure 6, over the four previous years, the number of allegations that met the definition of wrongdoing and were acted upon under the Act has fluctuated. In 2017–18, 60% of allegations (139 of 230) were acted upon compared to 41% of allegations (116 of 280) in 2019–20.

Figure 6 - Text version

| Type | 2016 to 2017 | 2017 to 2018 | 2018 to 2019 | 2019 to 2020 | 2020 to 2021 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Allegations of wrongdoing not acted upon | 97 | 91 | 129 | 164 | 76 |

| Allegations of wrongdoing acted upon | 98 | 139 | 114 | 116 | 112 |

| Total allegations assessed in that fiscal year | 195 | 230 | 243 | 280 | 188 |

In 2020–21, there were 76 allegations that did not meet the definition of wrongdoing and were not acted upon under the Act.Footnote 9 Highlights in Figure 7 include:

- a total of 42% of allegations were referred to other recourse processes, an increase from 35% in 2019–20

- 30% led to other actions (for example, resolved informally or withdrawn), an increase from 15% in 2019–20

- 27% were not referred to another recourse process and required no further action, a decrease from 50% in 2019–20

- 22% were referred to the harassment and violence complaint process, an increase from 5% in 2019–20

Figure 7 - Text version

| Type | Percentage of the 76 allegations that did not meet the definition of wrongdoing in 2020 to 2021 |

|---|---|

| Other action taken | 30% |

| Not referred to a recourse process listed below | 27% |

| Referred to the harassment and violence complaint process, provided for under the Canada Labour Code | 22% |

| Referred to human rights complaint process, provided for under the Canadian Human Rights Act | 12% |

| Referred to the grievance process, provided for under the Federal Public Sector Labour Relations Act | 4% |

| Referred to staffing complaint process, provided for under the Public Service Employment Act | 2% |

| Referred to the privacy complaint process, provided for under the Privacy Act | 2% |

As noted above, allegations that did not meet the definition of wrongdoing and were not acted upon under the Act are, in many cases, referred to more appropriate recourse mechanisms. Doing so provides an opportunity to assess whether any additional interventions or supports may be needed.

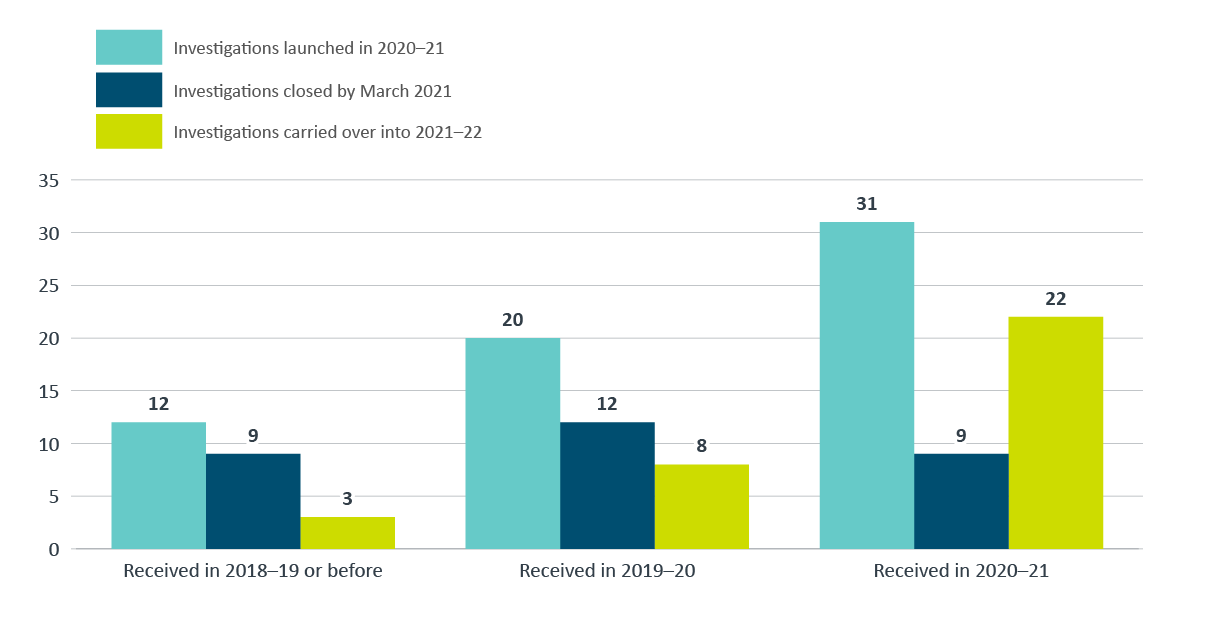

Step 3: allegations investigated

In 2020–21, 63 formal investigationsFootnote 11 were launched: the highest number in the past four years. Most of these investigations examined one or two allegations whereas some examined up to nine. Of the 63 investigations, 31 were based on allegations made in 2020–21, 20 were based on allegations made in 2019–20, and 12 were based on allegations made in 2018–19 or earlier (Figure 8).

By March 31, 2021, 30 investigations were closed. Of these, nine examined 23 allegations made in 2020–21, 12 examined 18 allegations made in 2019–20, and nine examined 33 allegations made in 2018–19 or earlier.

Finally, there were 33 investigations still ongoing at the end of the reporting period and these will be carried over to the next fiscal year. Of these, 22 investigations are examining allegations made in 2020–21, eight are examining allegations made in 2019–20, and three are examining allegations made in 2018–19 or earlier.

Figure 8 - Text version

| Type | Received in 2018 to 2019 or before | Received in 2019 to 2020 | Received in 2020 to 2021 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Investigation launched in 2020–21 | 12 | 20 | 31 |

| Investigation closed by March 2021 | 9 | 12 | 9 |

| Investigation carried over into 2021–22 | 3 | 8 | 22 |

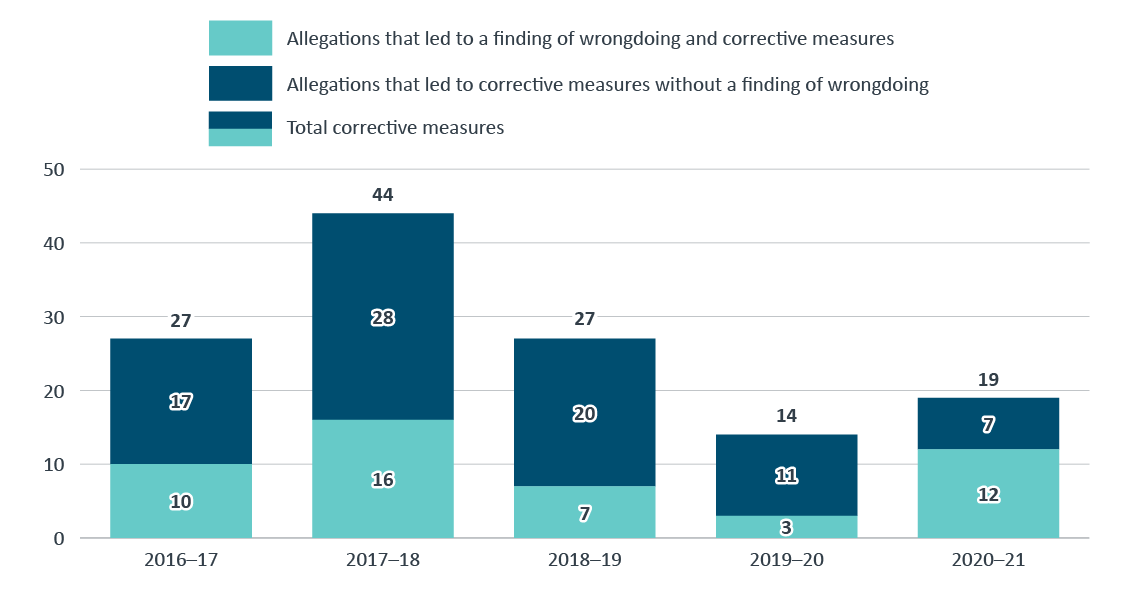

Step 4: findings and corrective measures reported

In 2020–21, the 30 investigations that were closed by March 31, 2021, examined 74 allegations and resulted in 12 allegations that led to a finding of wrongdoing and 19 allegations that led to corrective measures. For seven of the 19 allegations that led to corrective measures, there was no wrongdoing found (Figure 9).Footnote 12

A few trends were observed:

- increase in the number of allegations that led to a finding of wrongdoing and corrective measures compared to 2019–20

- decrease in the number of allegations that led only to corrective measures, continuing a trend that started in 2017–18

- more allegations that led to findings of wrongdoing and corrective measures than to corrective measures alone for the first time since 2016–17

Figure 9 - Text version

| Type | 2016 to 2017 | 2017 to 2018 | 2018 to 2019 | 2019 to 2020 | 2020 to 2021 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Allegations that led to a finding of wrongdoing and corrective measures | 10 | 16 | 7 | 3 | 12 |

| Allegations that led to corrective measures without a finding of wrongdoing | 17 | 28 | 20 | 11 | 7 |

| Total corrective measures | 27 | 44 | 27 | 14 | 19 |

Appendix A: summary of organizational activity related to disclosures under the Public Servants Disclosure Protection Act

In this section

- A.1 Disclosure activity, 2016–17 to 2020–21

- A.2 Organizations reporting activity under the Act in 2020–21

- A.3 Organizations reporting a finding of wrongdoing under the Act in 2020–21

- A.4 Organizations reporting no disclosure activities in 2020–21

- A.5 Organizations that do not have a senior officer for disclosure of wrongdoing pursuant to subsection 10(4) of the Act

- A.6 Inactive organizations for the purposes of reporting

Subsection 38.1(1) of the Public Servants Disclosure Protection Act (the Act) requires chief executives to prepare a report on the activities related to disclosures made in their organizations and to submit it to the Chief Human Resources Officer within 60 days after the end of each fiscal year. The statistics in this report are based on those reports. In the sections that follow, statistics from the four previous years are also provided to allow comparison. While these statistics provide a snapshot of internal disclosure activities under the Act, it is difficult to draw conclusions because of the differences between organizations. Employee concerns or issues, for example, may be addressed through different recourse mechanisms and processes in different organizations.

Although the Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS), Communications Security Establishment Canada (CSEC) and Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) are excluded from the Act by virtue of section 52 of the Act, they are required to establish their own procedures for the disclosure of wrongdoing, including for protecting persons who disclose wrongdoing. These procedures must be approved by the Treasury Board as being similar to those set out in the Act. CSIS’s procedures were approved in December 2009, CSEC’s procedures were approved in June 2011, and the CAF’s procedures were approved in April 2012.

A.1 Disclosure activity, 2016–17 to 2020–21

| General enquiries | 2020–21 | 2019–20 | 2018–19 | 2017–18 | 2016–17 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of general enquiries related to the Act | 172 | 250 | 323 | 293 | 212 |

| Disclosure activity | 2020–21 | 2019–20 | 2018–19 | 2017–18 | 2016–17 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of public servants who made disclosures | 123 | n/a | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Number of allegations received in disclosures under the Act | 169 | 216 | 269 | 291 | 209 |

| Number of referrals resulting from allegations received in disclosures made in another public sector organization | 5 | 4 | 3 | 5 | 1 |

| Number of cases carried over on the basis of allegations made in previous years | 193 | 238 | 173 | 128 | 122 |

| Total number of allegations (allegations received, referred, carried over) | 367 | 458 | 445 | 424 | 332 |

| Number of allegations that met the definition of wrongdoingFootnote a | 112 | 116 | 114 | 139 | 98 |

| Number of allegations that did not meet the definition of wrongdoingFootnote b | 76 | 164 | 129 | 91 | 97 |

| Number of investigations commenced as a result of disclosures received | 63 | 38 | 59 | 71 | 61 |

| Number of allegations that led to a finding of wrongdoing | 12 | 3 | 7 | 16 | 10 |

| Number of allegations that led to corrective measures | 19 | 11 | 20 | 28 | 17 |

| Organizations reporting | 2020–21 | 2019–20 | 2018–19 | 2017–18 | 2016–17 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of active organizations | 137 | 133 | 134 | 134 | 133 |

| Number of organizations that reported enquiries | 30 | 33 | 35 | 36 | 36 |

| Number of organizations that reported allegations received in disclosures | 27 | 24 | 29 | 35 | 22 |

| Number of organizations that reported findings of wrongdoing | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 |

| Number of organizations that reported corrective measures | 6 | 4 | 8 | 8 | 7 |

| Number of organizations that reported finding systemic problems that gave rise to wrongdoing | 2 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 0 |

| Number of organizations that did not disclose information about findings of wrongdoing within 60 days | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

A.2 Organizations reporting activity under the Act in 2020–21

| Organization | General enquiries | Allegations received in disclosures | Investigations commenced | Allegations received in disclosures that led to | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Received | Referred | Carried over from 2019–20 | Acted upon | Not acted upon | Carried over into 2021–22 | Finding of wrongdoing | Corrective measures | |||

| Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Atomic Energy of Canada Limited | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Canada Border Services Agency | 8 | 24 | 0 | 74 | 24 | 13 | 61 | 5 | 0 | 1 |

| Canada Economic Development for Quebec Regions | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Canada Revenue Agency | 5 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Canadian Food Inspection Agency | 0 | 4 | 0 | 17 | 3 | 18 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Canadian Heritage | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Civilian Review and Complaints Commission for the RCMP | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Correctional Service Canada | 42 | 5 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Department of Justice Canada | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Employment and Social Development Canada and Canada Employment Insurance Commission | 12 | 15 | 1 | 9 | 16 | 9 | 0 | 10 | 3 | 4 |

| Environment and Climate Change Canada | 2 | 15 | 0 | 4 | 6 | 0 | 13 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Export Development Canada | 12 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Farm Credit Canada | 0 | 27 | 0 | 0 | 26 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 4 |

| Fisheries and Oceans Canada | 3 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Global Affairs Canada | 4 | 28 | 1 | 16 | 8 | 4 | 33 | 13 | 6 | 6 |

| Health Canada | 4 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada | 0 | 7 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Impact Assessment Agency of Canada | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Indian Oil and Gas Canada | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Indigenous Services Canada | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Infrastructure Canada | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada and Office of the Superintendent of Bankruptcy Canada | 6 | 5 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 2 | 7 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| International Development Research Centre | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| National Capital Commission | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| National Defence | 12 | 8 | 2 | 31 | 11 | 1 | 29 | 6 | 0 | 0 |

| National Research Council Canada | 5 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Natural Resources Canada, Energy Supplies Allocation Board, and Northern Pipeline Agency Canada | 2 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Parks Canada | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Public Health Agency of Canada | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Public Service Commission of Canada | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Public Services and Procurement Canada | 2 | 4 | 0 | 22 | 5 | 0 | 21 | 13 | 0 | 0 |

| Royal Canadian Mint | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Royal Canadian Mounted Police | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Staff of the Non-Public Funds, Canadian Forces | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Statistics Canada | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Transport Canada | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Veterans Affairs Canada and Veterans Review and Appeal Board | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| VIA Rail Canada Inc. | 18 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Windsor-Detroit Bridge Authority | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 172 | 169 | 5 | 193 | 112 | 76 | 179 | 63 | 12 | 19 |

A.3 Organizations reporting a finding of wrongdoing under the Act in 2020–21

| Organization | Finding of wrongdoing | Corrective measures |

|---|---|---|

| Employment and Social Development Canada (ESDC) |

Knowingly directing or counselling a person to commit a wrongdoing set out in any of paragraphs (a) to (e) (paragraph 8(f) of the Act) Serious breach of a code of conduct established under section 5 or 6 (paragraph 8(e) of the Act) A contravention of any Act of Parliament or of the legislature of a province, or of any regulations made under any such Act (paragraph 8(a) of the Act) Case report: Acts of Founded Wrongdoing: PSDPA 2018-2019-006 |

An investigation into a disclosure was conducted and a manager was found to have committed wrongdoing by directing or counselling an employee to commit wrongdoing, and seriously breaching the Departmental Code of Conduct. The investigation also found that the Internal Integrity and Security Office in the Western Canada and Territories region had committed wrongdoing by contravening the Government Contracts Regulations and the Contracting Policy. The appropriate corrective or administrative measures are being determined for the individual(s) found to have committed, or been involved in, wrongdoing. Additional control measures are being implemented to prevent, avoid and address the inappropriate use of government acquisition cards:

|

| Employment and Social Development Canada |

A misuse of public funds or a public asset (paragraph 8(b) of the Act)Footnote 13 Case report: Acts of Founded Wrongdoing: PSDPA 2019-2020-007 |

An investigation was conducted in response to a disclosure, and an employee was found to have committed wrongdoing by making unauthorized use of government property. The employee failed to return a Government of Canada Blackberry cellphone and continued to use the cellphone after retiring from the public service. The Assistant Deputy Minister of Ontario region has already recovered the Government of Canada Blackberry cellphone and disconnected the cellphone account. In addition, the Ontario region has put in place a rigorous process in off-boarding employees, and the Innovation Information and Technology Branch now meticulously monitors the use of departmental cellphones and other devices to prevent these types of situations from occurring. |

| Global Affairs Canada |

A serious breach of a code of conduct established under section 5 or 6 (paragraph 8(e) under the Act) Case report: Acts of Founded Wrongdoing: FW-2018-Q1-00002 |

The Values and Ethics Unit received disclosures of wrongdoing against an executive employee outlining allegations of gross mismanagement and serious breaches of the Values and Ethics Code for the Public Sector, which would breach paragraphs 8(c) and (e) of the Public Servants Disclosure Protection Act. It was alleged that the respondent was involved in staffing irregularities and repeatedly made inappropriate comments to employees, some of which were of a sexual nature. It was also alleged that the respondent engaged in inappropriate behaviours that could constitute systemic harassment. The investigation concluded that the allegations of gross mismanagement and staffing irregularities were not founded. However, it was determined that most of the allegations of inappropriate sexual comments and behaviours were founded, and therefore constitute a serious breach of the departmental Values and Ethics Code. The disclosure was therefore deemed to be partially founded. The preponderance of evidence and the balance of probabilities supported findings of wrongdoing in accordance with paragraph 8(e) of the Act, a serious breach of a code of conduct established under section 5 or 6 of the Act. Administrative measures were taken with respect to the executive employee by the delegated authority during the course of the investigation. These measures included sensitivity training and coaching. The respondent left the public service before the conclusion of the investigation. Actions will also be taken by Global Affairs Canada to restore the work environment within the organizational unit involved. |

| Immigration, Refugees, and Citizenship Canada |

A gross mismanagement in the public sector (paragraph 8(c) under the Act) Case report: Acts of founded wrongdoing: FW-2021-Q1-00001 |

The Internal Disclosure Office received a disclosure of wrongdoing by a director at their national headquarters. It was alleged that the director bullied and marginalized another employee under their supervision (including using vulgar language and inappropriate racial comments), failed to disclose a conflict of interest in the promotion of another employee in which a personal relationship existed, and failed to disclose a conflict of interest in the approval of a sole-source contract with a third-party organization in which a financial stake was held. The investigation concluded that the allegations were founded and that the director’s actions constitute wrongdoing under the Act in relation to paragraph 8(c), “a gross mismanagement in the public sector.” While the director resigned before the investigation was concluded, it has been recommended that departmental senior officials ensure policy directives and oversight mechanisms are strengthened for prevention and early determination of potential similar acts of misappropriation. Management agrees with the report’s recommendation and has developed an action plan to address it. |

A.4 Organizations reporting no disclosure activities in 2020–21

- Accessibility Standards Canada

- Atlantic Canada Opportunities Agency

- Atlantic Pilotage Authority Canada

- Bank of Canada

- Business Development Bank of Canada

- Canada Council for the Arts

- Canada Deposit Insurance Corporation

- Canada Development Investment Corporation

- Canada Energy Regulator

- Canada Infrastructure Bank

- Canada Post

- Canada School of Public Service

- Canada Science and Technology Museum

- Canadian Air Transport Security Authority

- Canadian Broadcasting Corporation

- Canadian Centre for Occupational Health and Safety

- Canadian Commercial Corporation

- Canadian Grain Commission

- Canadian Institutes of Health Research

- Canadian Museum for Human Rights

- Canadian Museum of History and Canadian War Museum

- Canadian Museum of Nature

- Canadian Northern Economic Development Agency

- Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission

- Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission

- Canadian Space Agency

- Canadian Transportation Agency

- Courts Administration Service

- Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada

- Defence Construction Canada

- Department of Finance Canada

- Destination Canada

- Farm Products Council of Canada

- Federal Bridge Corporation

- Federal Economic Development Agency for Southern Ontario

- Financial Consumer Agency of Canada

- Financial Transactions and Reports Analysis Centre of Canada

- Freshwater Fish Marketing Corporation

- Great Lakes Pilotage Authority Canada

- Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada

- International Joint Commission (Canadian section)

- Invest in Canada Hub

- Laurentian Pilotage Authority Canada

- Library and Archives Canada

- Marine Atlantic Inc.

- Military Police Complaints Commission of Canada

- National Arts Centre

- National Gallery of Canada

- National Security and Intelligence Review Agency Secretariat

- Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada

- Office of the Auditor General of Canada

- Office of the Chief Electoral Officer

- Office of the Commissioner for Federal Judicial Affairs Canada

- Office of the Information Commissioner of Canada

- Office of the Public Sector Integrity Commissioner of Canada

- Office of the Registrar of the Supreme Court of Canada

- Office of the Secretary to the Governor General

- Office of the Superintendent of Financial Institutions Canada

- Pacific Pilotage Authority Canada

- Parole Board of Canada

- Patented Medicine Prices Review Board Canada

- Privy Council Office

- Public Prosecution Service of Canada

- Public Safety Canada

- Public Sector Pension Investment Board

- Shared Services Canada

- Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada

- Statistical Survey Operations

- The Correctional Investigator Canada

- The National Battlefields Commission

- Western Economic Diversification Canada

- Women and Gender Equality Canada

A.5 Organizations that do not have a senior officer for disclosure of wrongdoing pursuant to subsection 10(4) of the Act

- Administrative Tribunals Support Service of Canada

- Canada Lands Company Limited

- Canadian Dairy Commission

- Canadian Human Rights Commission

- Canadian Intergovernmental Conference Secretariat

- Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21

- Canadian Race Relations Foundation

- Copyright Board Canada

- Military Grievances External Review Committee

- National Film Board

- Office of the Commissioner of Lobbying of Canada

- Office of the Commissioner of Official Languages

- Office of the Privacy Commissioner of Canada

- Polar Knowledge Canada

- RCMP External Review Committee

- Standards Council of Canada

- Telefilm Canada

- Transportation Safety Board of Canada

A.6 Inactive organizations for the purposes of reporting

- The Director, The Veterans’ Land Act

- The Jacques-Cartier and Champlain Bridges Inc.

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada

Appendix B: Public Service Employee Survey – ethics in the workplace

In this section

The data presented in this appendix is sourced from the 2020 Public Service Employee Survey (PSES) results for the public service.Footnote 14

Figure 10 - Text version

| Survey year | Positive answers |

|---|---|

| 2008 | 70% |

| 2011 | 74% |

| 2014 | 77% |

| 2017 | 74% |

| 2018 | 71% |

| 2019 | 71% |

| 2020 | 73% |

Figure 11 - Text version

| Survey year | Positive answers |

|---|---|

| 2011 | 44% |

| 2014 | 45% |

| 2017 | 48% |

| 2018 | 48% |

| 2019 | 50% |

| 2020 | 55% |

Figure 12 - Text version

| Survey year | Positive answers |

|---|---|

| 2011 | 58% |

| 2014 | 62% |

| 2017 | 64% |

| 2018 | 63% |

| 2019 | 68% |

| 2020 | 73% |

Disaggregated analysis by demography, region and sector

Demography

Figure 13 - Text version

| Question | Indigenous peoples | Persons with disabilities | Members of visible minorities | Women | Public service |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Question 38. If I am faced with an ethical dilemma or a conflict between values in the workplace, I know where I can go for help in resolving the situation. | 69% | 66% | 71% | 75% | 73% |

| Question 39. My department or agency does a good job of promoting values and ethics in the workplace. | 68% | 64% | 74% | 76% | 74% |

| Question 40. I feel I can initiate a formal recourse process (for example, grievance, complaint, appeal) without fear of reprisal. | 51% | 43% | 54% | 55% | 55% |

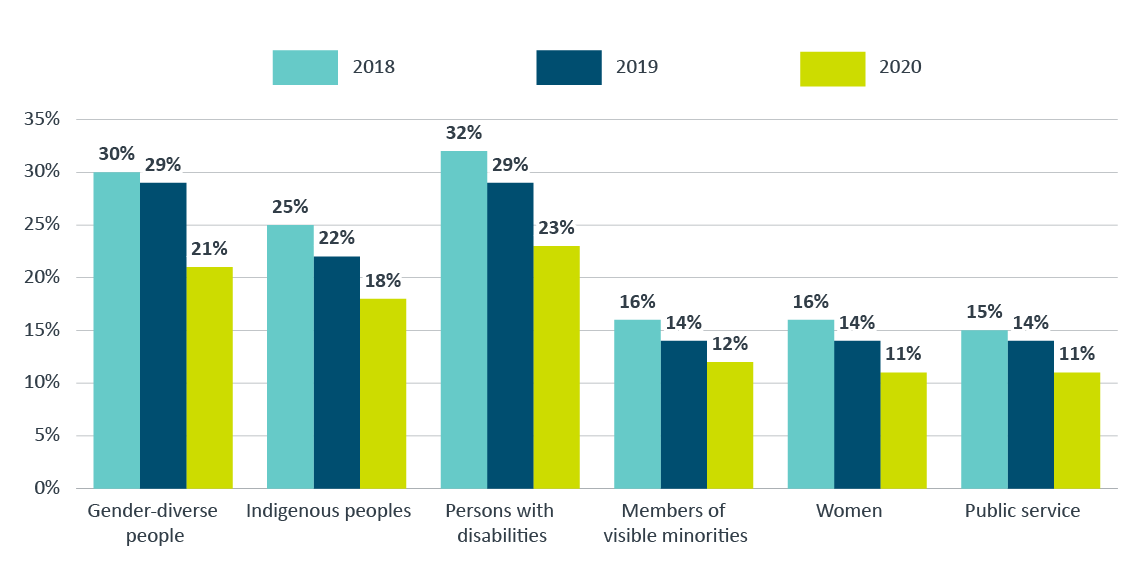

Figure 14 - Text version

| Year | Gender-diverse people | Indigenous peoples | Persons with disabilities | Members of visible minorities | Women | Public service |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2018 | 30% | 25% | 32% | 16% | 16% | 15% |

| 2019 | 29% | 22% | 29% | 14% | 14% | 14% |

| 2020 | 21% | 18% | 23% | 12% | 11% | 11% |

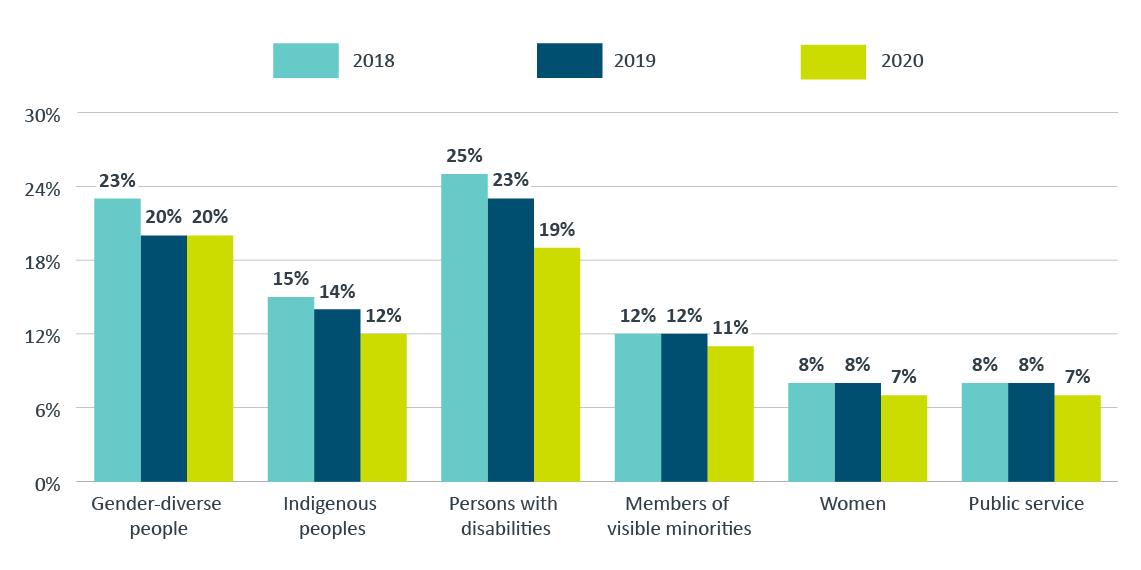

Figure 15 - Text version

| Year | Gender-diverse people | Indigenous peoples | Persons with disabilities | Members of visible minorities | Women | Public service |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2018 | 23% | 15% | 25% | 12% | 8% | 8% |

| 2019 | 20% | 14% | 23% | 12% | 8% | 8% |

| 2020 | 20% | 12% | 19% | 11% | 7% | 7% |

Region

| Provinces, territory or National Capital Region | Question 38. If I am faced with an ethical dilemma or a conflict between values in the workplace, I know where I can go for help in resolving the situation. (%) | Question 39. My department or agency does a good job of promoting values and ethics in the workplace. (%) | Question 40. I feel I can initiate a formal recourse process (e.g., grievance, complaint, appeal) without fear of reprisal. (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alberta | 71 | 70 | 53 |

| British Columbia | 70 | 69 | 52 |

| Manitoba | 73 | 74 | 56 |

| National Capital Region | 74 | 77 | 56 |

| New Brunswick | 77 | 76 | 61 |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 80 | 83 | 66 |

| Northwest Territories | 73 | 72 | 57 |

| Nova Scotia | 70 | 70 | 55 |

| Nunavut | 71 | 74 | 56 |

| Ontario (excluding National Capital Region) | 72 | 72 | 55 |

| Outside of Canada | 80 | 71 | 41 |

| Prince Edward Island | 79 | 81 | 62 |

| Quebec (excluding National Capital Region) | 71 | 74 | 58 |

| Saskatchewan | 71 | 69 | 52 |

| Yukon | 72 | 69 | 58 |

Sector

| Organizational mandate | Question 38. If I am faced with an ethical dilemma or a conflict between values in the workplace, I know where I can go for help in resolving the situation. (%) | Question 39. My department or agency does a good job of promoting values and ethics in the workplace. (%) | Question 40. I feel I can initiate a formal recourse process (e.g., grievance, complaint, appeal) without fear of reprisal. (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Agents of Parliament | 78 | 82 | 65 |

| Business and economic development | 70 | 73 | 52 |

| Central agency and government operations | 76 | 78 | 59 |

| Enforcement and regulatory | 77 | 81 | 61 |

| Justice, courts and tribunal | 74 | 75 | 50 |

| Science-based | 72 | 74 | 55 |

| Security and military | 67 | 65 | 51 |

| Social and cultural | 77 | 79 | 58 |

| Public service | 73 | 74 | 55 |

| Employment community | Question 38. If I am faced with an ethical dilemma or a conflict between values in the workplace, I know where I can go for help in resolving the situation. (%) | Question 39. My department or agency does a good job of promoting values and ethics in the workplace. (%) | Question 40. I feel I can initiate a formal recourse process (e.g., grievance, complaint, appeal) without fear of reprisal. (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Access to information and privacy | 79 | 81 | 61 |

| Administration and operations | 77 | 77 | 58 |

| Client contact centre | 77 | 81 | 63 |

| Communications or public affairs | 74 | 76 | 56 |

| Compliance, inspection and enforcement | 72 | 71 | 52 |

| Data sciences | 72 | 77 | 59 |

| Evaluation | 73 | 77 | 54 |

| Federal regulators | 73 | 73 | 52 |

| Financial management | 76 | 79 | 58 |

| Health care practitioners | 67 | 65 | 49 |

| Human resources | 80 | 80 | 61 |

| Information management | 74 | 77 | 59 |

| Information technology | 76 | 79 | 62 |

| Internal audit | 79 | 82 | 61 |

| Legal services | 74 | 74 | 46 |

| Library services | 73 | 73 | 56 |

| Materiel management | 71 | 72 | 60 |

| None of the above | 69 | 68 | 51 |

| Other services to the public | 73 | 73 | 56 |

| Policy | 73 | 74 | 51 |

| Procurement | 78 | 79 | 61 |

| Project management | 74 | 76 | 54 |

| Real property | 71 | 72 | 57 |

| Science and technology | 69 | 73 | 55 |

| Security | 57 | 51 | 40 |

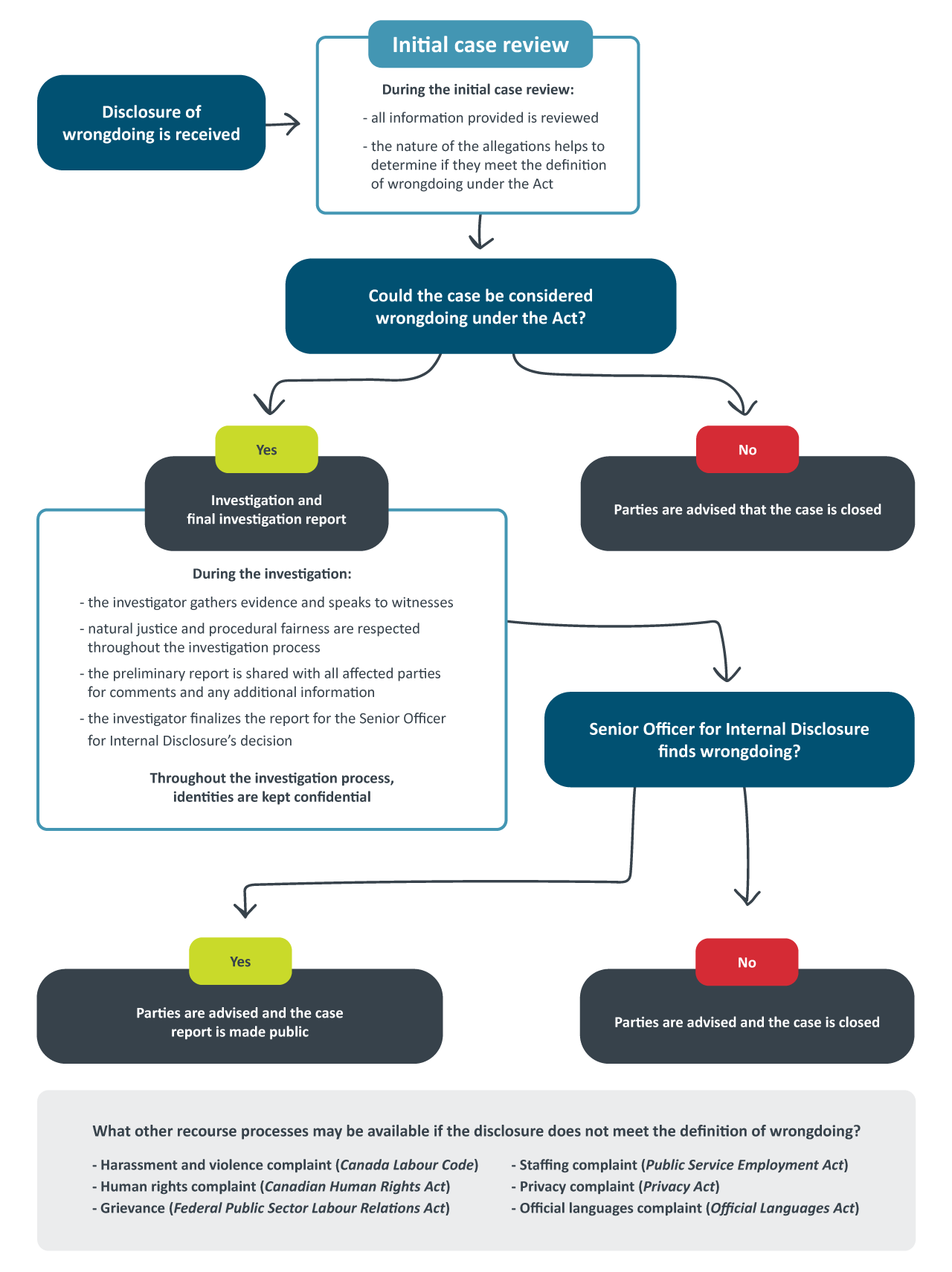

Appendix C: disclosure process under the Act

Appendix C - Text version

Disclosure of wrongdoing is received

Initial case review

During the initial case review:

- all information provided is reviewed

- the nature of the allegations helps to determine if they meet the definition of wrongdoing under the Act

Could the case be considered wrongdoing under the Act?

If no: Parties are advised that the case is closed

If yes: Investigation and final investigation report

During the investigation:

- the investigator gathers evidence and speaks to witnesses

- natural justice and procedural fairness are respected throughout the investigation process

- the preliminary report is shared with all affected parties for comments and any additional information

- the investigator finalizes the report for the Senior Officer for Internal Disclosure’s decision

Throughout the investigation process, identities are kept confidential

Senior Officer for Internal Disclosure finds wrongdoing?

If no: Parties are advised and the case is closed

If yes: Parties are advised and the case report is made public

What other recourse processes may be available if the disclosure does not meet the definition of wrongdoing?

- Harassment and violence complaint (Canada Labour Code)

- Human rights complaint (Canadian Human Rights Act)

- Grievance (Federal Public Sector Labour Relations Act)

- Staffing complaint (Public Service Employment Act)

- Privacy complaint (Privacy Act)

- Official languages complaint (Official Languages Act)

Appendix D: key terms

In this section

For the purposes of the Public Servants Disclosure Protection Act (the Act) and this report, “public servant” means every person employed in the public sector. This includes the deputy heads and chief executives of public sector organizations, but it does not include other Governor in Council appointees (for example, judges or board members of Crown corporations) or parliamentarians and their staff.

The Act defines wrongdoing as any of the following actions in, or relating to, the public sector:

- a violation of a federal or provincial law or regulation

- a misuse of public funds or assets

- a gross mismanagement in the public sector

- a serious breach of a code of conduct established under the Act

- an act or omission that creates a substantial and specific danger to the life, health or safety of persons, or to the environment

- knowingly directing or counselling a person to commit a wrongdoing

A protected disclosure is a disclosure that is made in good faith by a public servant under any of the following conditions:

- in accordance with the Act, to the public servant’s immediate supervisor or senior officers for disclosure of wrongdoing, or to the Public Sector Integrity Commissioner of Canada

- in the course of a parliamentary proceeding

- in the course of a procedure established under any other act of Parliament

- when lawfully required to do so

The Act defines reprisal as any of the following measures taken against a public servant who has made a protected disclosure or who has, in good faith, cooperated in an investigation into a disclosure:

- a disciplinary measure

- demotion of the public servant

- termination of the employment of the public servant

- a measure that adversely affects the employment or working conditions of the public servant

- a threat to do any of those things or to direct a person to do them

Every organization subject to the Act is required to establish internal procedures to manage disclosures made in the organization. Organizations that are too small to establish their own internal procedures can declare an exception under subsection 10(4) of the Act.

In organizations that have declared an exception, disclosures under the Act may be made to the Public Sector Integrity Commissioner of Canada.

The senior officer for disclosure of wrongdoing is the person designated in each organization to receive and deal with disclosures made under the Act. Senior officers have the following key leadership roles for implementing the Act in their organizations:

- providing information, advice and guidance to public servants regarding the organization’s internal disclosure procedures, including the making of disclosures, the conduct of investigations into disclosures, and the handling of disclosures made to supervisors

- receiving and recording disclosures and reviewing them to establish whether there are sufficient grounds for further action under the Act

- managing investigations into disclosures, including determining whether to deal with a disclosure under the Act, initiate an investigation or cease an investigation

- coordinating the handling of a disclosure with the senior officer of another federal public sector organization, if a disclosure or an investigation into a disclosure involves that other organization

- notifying, in writing, the person or persons who made a disclosure of the outcome of any review or investigation into the disclosure and of the status of actions taken on the disclosure, as appropriate

- reporting the findings of investigations, as well as any systemic problems that may give rise to wrongdoing, directly to their chief executive, with any recommendations for corrective action

Other relevant terms

- allegation of wrongdoing

- The communication of a potential instance of wrongdoing as defined in section 8 of the Act. The allegation must be made in good faith, and the person making it must have reasonable grounds to believe that it is true.

- disclosure

- The provision of information by a public servant to their immediate supervisor or to a senior officer for disclosure of wrongdoing that includes one or more allegations of possible wrongdoing in the public sector, in accordance with section 12 of the Act.

- disclosure that was acted upon (admissible disclosure)

- An allegation received in a disclosure where action, including preliminary analysis, fact‑finding and investigation, was taken to determine whether wrongdoing occurred and where that determination was made during the reporting period.

- disclosure that was not acted upon (inadmissible disclosure)

- An allegation received in a disclosure for which the designated senior officer for disclosure of wrongdoing determined that the definition of wrongdoing under the Act was not met. The allegation in the disclosure was either referred to another process or required no further action.

- general enquiry

- An enquiry about procedures established under the Act or about possible wrongdoings, not including actual disclosures.

- investigation

- A formal investigation triggered by a disclosure. An investigation may look into one or more allegations that result from a disclosure of possible wrongdoing.

© Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, represented by the President of the Treasury Board, 2021,

Catalogue No.BT1-18E-PDF, ISSN: 2292-048X