Annual Report on Official Languages 2021–22

Table of contents

- Message from the President of the Treasury Board

- Introduction

- Chapter 1. Communications with and services to the public

- Chapter 2. Language of work

- Chapter 3. Federal institutions and the participation of English-speaking and French-speaking Canadians

- Chapter 4. Institutions and management of the official languages file

- Chapter 5. Official languages and crisis situations

- Chapter 6. Official languages and TBS

- Conclusion of the report

- Appendix A: Methodology for reporting on the status of official languages programs

- Appendix B: Federal institutions required to submit a review for the 2021–22 fiscal year

- Appendix C: Definitions

- Appendix D: Statistical tables

- Appendix E: Statistics on events held by the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat during the 2021–22 fiscal year

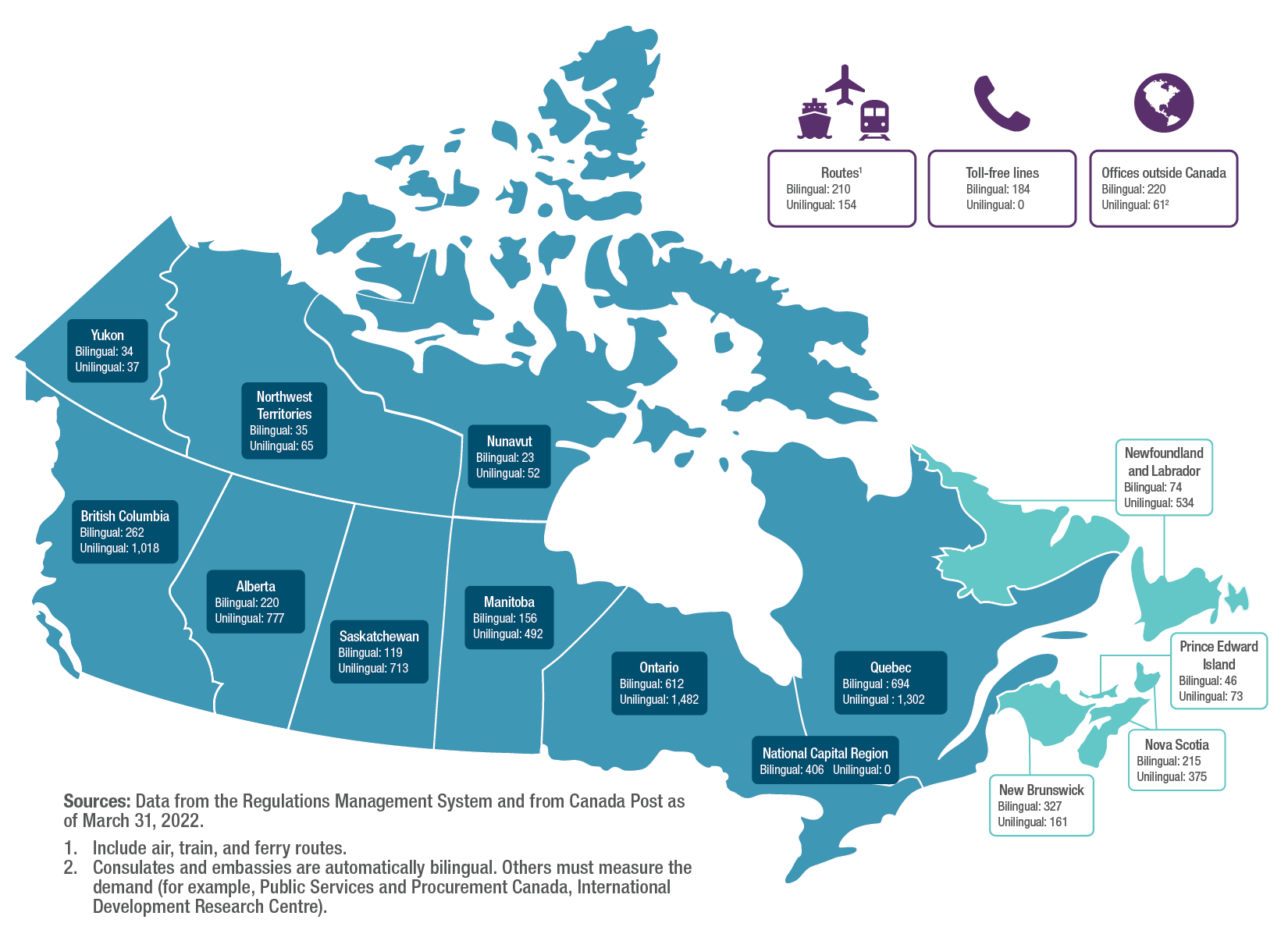

- Appendix F: Distribution of federal offices and service locations as of March 31, 2022

Message from the President of the Treasury Board

President of the Treasury Board

I am pleased to present the 34th Annual Report on Official Languages for the 2021–22 fiscal year.

Over 50 years ago, the Official Languages Act established the fundamental right that any member of the public may communicate with, and receive services from, designated federal offices in the official language of their choice. It has also been 35 years since the act gave federal public servants the right to use either official language in their workplace. This report describes how federal institutions are meeting these and other important official languages obligations.

While we have made great progress over the years to foster bilingualism across the public service, some challenges remain. To address these challenges, the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat (TBS) is driving change to achieve real impact across government. For example, TBS is setting clear objectives for institutions when they apply our new Official Languages Regulations, so that more bilingual services can be offered across the country. And to foster bilingualism among employees, we are developing a new second language training framework so that all federal public servants can find opportunities to learn, improve, and use both official languages in the workplace.

Of course, I am particularly pleased with the progress we have made on the legislative front with the passage of Bill C-13, An Act to amend the Official Languages Act. This new law will help protect and enhance the vitality of linguistic minority communities and promote our 2 official languages across the country. It also extends mandatory bilingual capacity to all deputy ministers and to all federal managers and supervisors in bilingual regions.

The act now gives the President of the Treasury Board a leading role in official languages governance and implementation. It strengthens and broadens my department’s existing powers, giving it increased responsibilities in monitoring, auditing, and evaluating institutions’ compliance. TBS will also have a new role in monitoring positive measures taken by federal institutions to enhance the vitality of official language minority communities, including agreements between the federal and other levels of government. By enhancing oversight, we will make sure that federal institutions fulfill their official languages commitments, thus improving service delivery to Canadians in the official language of their choice.

We have come a long way over the past 5 decades. The federal public service is more bilingual today than it has ever been, and our official languages are one of the key pillars of Canada’s identity. I’m optimistic that, through updated legislation and the sustained dedication of federal institutions, we will continue to deliver on the promise and expectations of a vibrant bilingual country.

I invite you to read this report to learn more about how federal institutions are working to meet their official languages commitments.

Original signed by

The Honourable Anita Anand

President of the Treasury Board

Introduction

The Treasury Board is responsible for the general direction and coordination of the policies and programs relating to the implementation of Parts IV, V and VI of the Official Languages Act (the Act) in federal institutions. The Office of the Chief Human Resources Officer, within the Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat (TBS), is responsible for establishing and assessing the extent to which these policies and programs are applied and what impacts they have.

In concrete terms, TBS assists some 200 federal institutions that are subject to the Act in fully meeting their linguistic obligations. This includes departments and agencies, Crown corporations and entities that have been privatized, such as Air Canada.

These obligations fall into four main categories. Federal institutions must

- serve and communicate with members of the public in both official languages

- establish a bilingual workplace in regions designated bilingual

- contribute to maintaining a public service whose workforce tends to reflect Canada’s demographic composition in terms of official languages

- ensure that official languages issues are suitably managed

This 34th Annual Report examines the extent to which federal institutions have been successful in meeting the above obligations. It also provides examples of practices whose widespread adoption would be beneficial.

TBS requires federal institutions to submit an official languages review at least once every three years.Footnote 1 This report provides a general overview of the results of the reviews submitted by federal institutions for the 2019–20, 2020–21 and 2021–22 fiscal years, comparing them, where possible, to those provided in the 2016–19 cycle. Appendix A presents the specific methodology used to analyze the results.

Chapter 1 of this report deals with the results for communications with and services to the public, Chapter 2 with language of work, Chapter 3 with Anglophone and Francophone representation in the federal public service, and Chapter 4 with official languages governance. Chapter 5 describes how institutions responded to the pandemic. Chapter 6 outlines some of the measures taken by TBS in 2021–22 to promote overall compliance with the Act. In particular, it discusses the efforts to strengthen official languages coordination and accountability.

Chapter 1. Communications with and services to the public

In this section

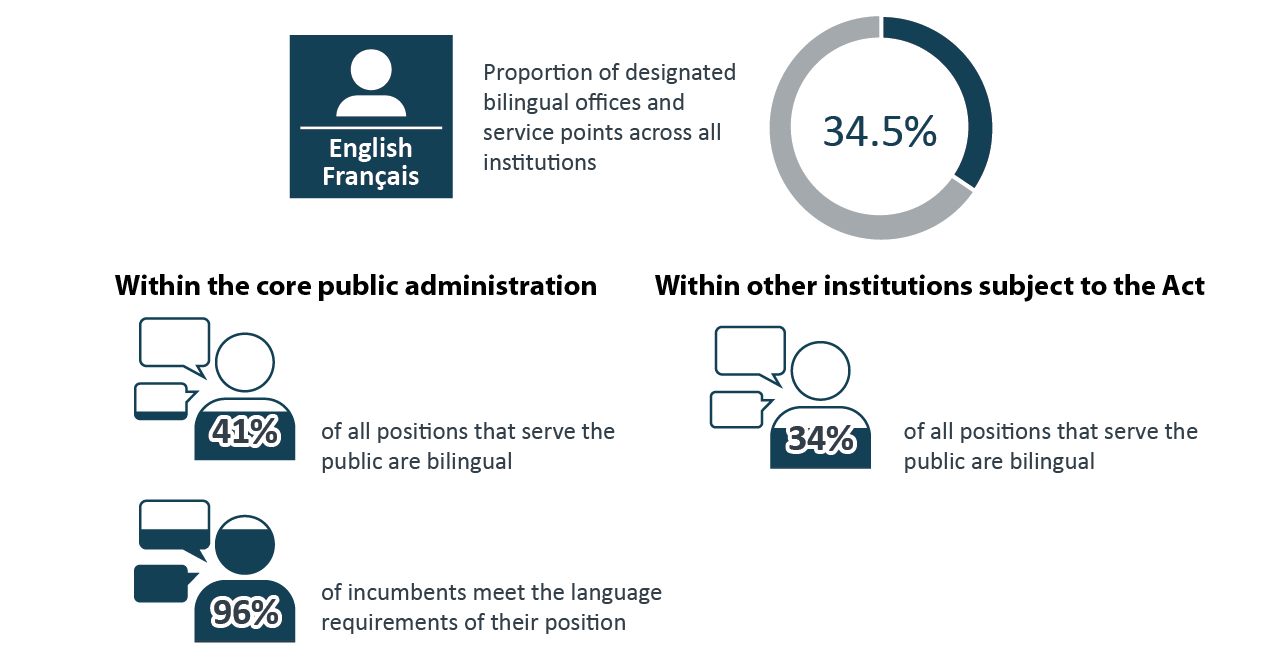

Infographic 1 - Text version

Proportion of designated bilingual offices and service points across all institutions: 34.5%

Within the core public administration, 41% of all positions that serve the public are bilingual

96% of incumbents meet the language requirements of their position

Within other institutions subject to the Act, 34% of all positions that serve the public are bilingual

1.1 Summary

The network of public offices and service locations operated by federal institutions (see Appendix F for a map of the network of offices and service locations) spans all provinces and territories and extends to Canadian offices internationally. This network provides service in person; over the telephone; aboard aircraft, ferries and trains; and through interactive kiosks. As of March 31, 2022, institutions had 11,134 offices and service locations,Footnote 2 of which 3,838 (34.5%) were required to provide services to and communicate with the public in both official languages.

TBS has a target of at least 90% of federal institutions and their offices and service locations will “nearly always” comply with their obligations under the Act and will “nearly always” apply certain best practices (such as including official languages in the agenda of senior management meetings).Footnote 3

As shown in Table 1, a very high percentage of federal institutions surveyed between 2019 and 2022 “nearly always” met obligations relating to communications with and service to the public. This positive result is largely attributable to the fact that federal institutions have the ability to provide services in both languages. For example, as of March 31, 2022, 41.1% of the 114,469 incumbents of positions serving the public in the core public administration (47,057 employees) were required to offer services in both English and French. Of these employees, 96.6% met the language requirements of their position. In other words, they were able to provide service at the desired level to both English and French speakers.Footnote 4

Nevertheless, there is room for improvement since, in the last cycle, the aforementioned 90% target was met for only 4 of the 11 statements presented in Table 1. That is insufficient, even though it is a slight improvement over 2016–19, when this target was met for only 3 of the 11 statements.

| Questions | 2016–19 | 2019–22 |

|---|---|---|

| Oral communications occur in the official language chosen by the public when the office is designated bilingual. | 86% | 89% |

| Written communications occur in the official language chosen by the public when the office is designated bilingual. | 91%Footnote * |

95%Footnote * |

| All communications material is produced in both official languages and is simultaneously issued in full in both official languages when the material comes from a designated bilingual office. | 85% | 87% |

| The English and French versions of websites are simultaneously posted in full and are of equal quality. | 89% | 93%Footnote * |

| Signs identifying the institution’s offices or facilities are in both official languages at all locations. | 93%Footnote * |

|

| Appropriate measures are taken to greet the public in person in both official languages. | 80% | 84% |

| Appropriate measures are taken to greet the public by telephone, including recorded messages, in both official languages. | N/AFootnote 6 |

82%Footnote 7 |

| Contracts and agreements with third parties contain clauses setting out the office’s or facility’s linguistic obligations that the third parties must meet. | 76% | 78% |

| The linguistic obligations in these clauses have been met. | 80% | 74% |

| The institution selects and uses advertising media that reach the targeted public in the most efficient way possible in the official language of their choice. | 100%Footnote * |

94%Footnote * |

| The institution respects the principle of substantive equality in its communications and services to the public, as well as in the development and assessment of policies and programs. | 81% | 79% |

1.2 Oral and written communications

Between 2019 and 2022, 95% of institutions reported that when communicating with the public in writing (particularly through news releases and public notices), they “nearly always” did so in the official language chosen by the public, an increase of four percentage points from the 2016–19 cycle. This is the obligation that federal institutions are currently most compliant with.

Institutions are also doing slightly better on oral communications than in the last cycle. Specifically, 89%, up from 86% in 2016–19, “nearly always” use both English and French, particularly in news conferences, public addresses and videos.

Best practice

The Copyright Board Canada assists those appearing before it to do so in the official language of their choice by providing access to simultaneous interpretation services during oral hearings. And when the Board conducts public consultations on its practices and procedures or shares information at meetings, it generally holds English-language sessions, French-language sessions and bilingual sessions. Stakeholders can choose which session they want to attend, which maximizes participation.

1.3 Active offer

For an institution, active offer means clearly indicating, both visually and orally, that English or French can be used to communicate with the institution or obtain services from one of its designated bilingual offices. It is mandatory – and critically important – for every institution to practise active offer, thereby encouraging members of the public to interact with it in the official language of their choice.

Active offer remains the Achilles heel of too many federal institutions. Only 84% of the institutions surveyed between 2019 and 2022 (four percentage points better than in 2016–19) said they “nearly always” took appropriate greeting measures (such as saying “Hello, bonjour!”) to signal to people who visit their offices that they can feel comfortable using English or French. The reviews for the last two years also show that only 82% of institutions “nearly always” practise active offer on the telephone. However, 91% of institutions have English and French signage (see Figure 1) in their designated bilingual offices almost all the time, as expected.

Best practice

Canada Revenue Agency telephone services are always available in the official language chosen by the public. Taxpayers are always referred to one number for service in English and another number for service in French. However, sometimes people choose the wrong number (for example, the one for service in French instead of the one for service in English). To remedy this problem, an audio message was added to give them the opportunity to request service in the other official language if they wish. Whichever number they use, taxpayers can change their language preference as needed.

1.4 Outreach and advertising

To meet the needs of the public, the websites of federal institutions must be accessible in both official languages. Overall, they are. In the 2019–22 cycle, 93% of institutions reported that, with rare exceptions, the English and French content on their website is posted simultaneously, is of equal quality, and is published in full. This is four percentage points higher than in the 2016–19 cycle.

While the Internet has become the tool used by a large segment of the public to access government information, many citizens still expect to be able to access government information by traditional means. Consequently, federal institutions must continue to use English and French in communication tools such as their reports and brochures. In their most recent reviews, 87% of institutions stated that communications materials issued by their designated bilingual offices are “nearly always” produced and disseminated simultaneously and in full in both English and French. In the previous cycle, the percentage was 85%, which was also below the target.

When it comes to advertising, more than 94% of federal institutions say they “nearly always” choose and use advertising vehicles (such as newspapers, television and radio stations or Facebook pages) that enable them to reach their target audience in the official language of their choice. This is a small decrease from the previous cycle, when federal institutions had a perfect score.

1.5 Contracts and agreements with third parties

Under the Act, federal institutions must ensure that the information or services provided by a partner on their behalf are provided in the public’s official language of choice. Many federal institutions do not always do so.

First, only 78% of institutions ensure that contracts and agreements with third parties acting on behalf of bilingual offices “nearly always” include clauses that set out the language obligations that these third parties must meet. This is slightly better than in 2016–19, when it was 76%. Second, 74% of federal institutions that have language clauses in their contracts or agreements with third parties report that those clauses were “nearly always” adhered to. This is a six percentage-point drop from 2016–19.

Best practice

The Canada Revenue Agency (CRA) ensures that any agreement with third parties contains clauses setting out the language obligations that the third party must meet. An example of a standard clause that the CRA includes in contracts with security agencies is provided below.

“6.0 Official languages – Active offer

The contractor must ensure that communications and services of their guards are actively offered in English and French.

- Prominently displaying the official languages symbol

- Greeting members of the public in both official languages, beginning with the official language of the majority of the population of the province or territory where the office is located (for example, ‘Hello/bonjour. Can I help you?/Puis-je vous aider?’ for all provinces outside Quebec and ‘Bonjour/hello. Puis-je vous aider?/Can I help you?’ in the province of Quebec)”

1.6 Upholding the principle of substantive equality

According to the reviews submitted between 2019 and 2022, 79% of federal institutions “nearly always” uphold the principle of substantive equality when communicating with or providing services to the public. This means that about four out of five institutions (the same as in 2016–19) work to provide official language minority communities with the same quality of information and services as those offered to the majority by offering services with distinct content or with an approach tailored to the specific needs of English-speakers or French-speakers.

Best practice

Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada (ISED) upholds the principle of substantive equality in providing services to the public. It does so by taking into account the characteristics of official language minority communities and the particular context in which they live. In practical terms, ISED ensures that the so-called official languages “filter” is applied systematically. It is used to consider and evaluate the potential effects of the institution’s policies, services and programs on English-speaking or French-speaking communities. In 2021–22, the official languages filter was applied in the assessment of 32 ISED Treasury Board submissions and 30 memoranda to Cabinet.

Best practice

Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada implemented a suite of virtual services, which have been instrumental in providing equal access to citizenship services to minority language groups across the country, including in rural areas. The Department manages the Provincial Nominee Program, which encourages the economic development of official language minority communities across Canada. All bilateral agreements to operate the program’s streams contain provisions to support and favour French-speaking immigration. The Department also launched the Atlantic Immigration Program, which presents an opportunity for businesses, including Francophone employers in the region, to recruit French-speaking foreign nationals to fill local labour market needs that cannot be filled by Canadians or permanent residents. Part of the job endorsement process requires the employer to work with a settlement service provider organization in their province to support the candidate and their family. There are Francophone organizations and pre-arrival services available for candidates whose preferred language is French.

1.7 Conclusion

A large majority of federal institutions “nearly always” comply with their obligations under Part IV of the Act or embrace certain best practices in communicating with and serving the public.

However, the 90% compliance target is met in only 7 out of 11 cases. In addition, certain key practices, such as active offer, the inclusion of language clauses in agreements with third parties, and the application of the principle of substantive equality, are applied by fewer than four out of five institutions.

Federal institutions, with TBS support (as described in Chapter 6), will need to take action to correct existing deficiencies.

Chapter 2. Language of work

In this section

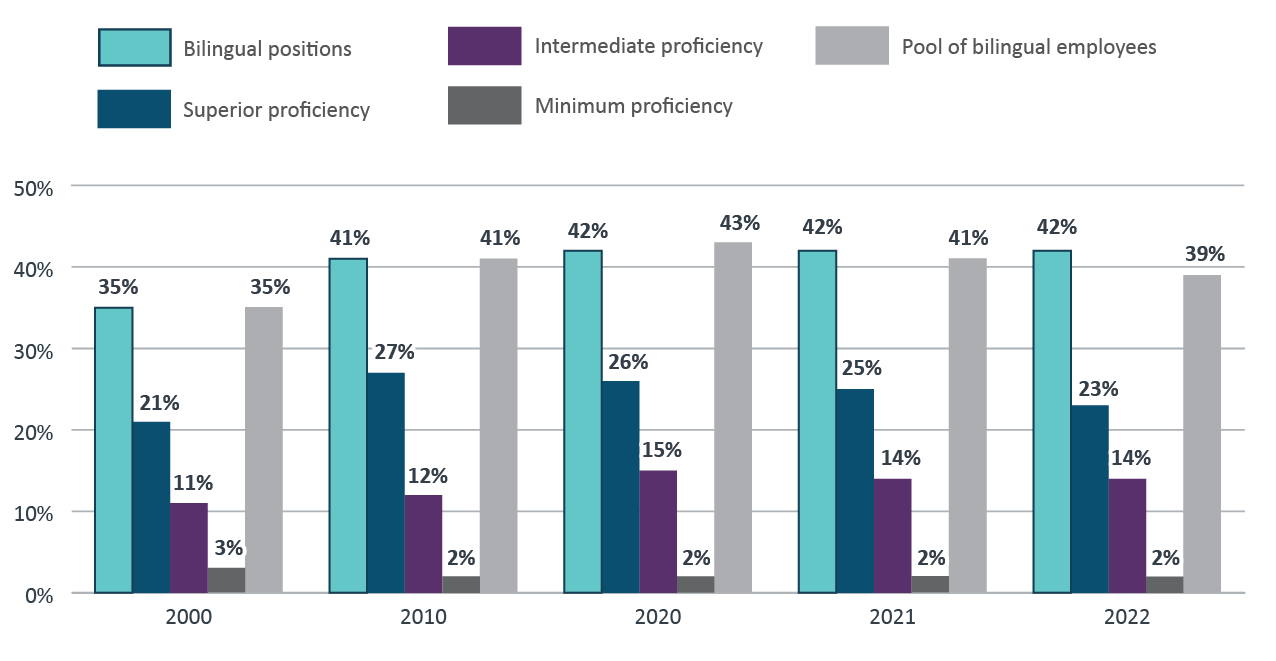

Infographic 2 - Text version

Within the core public administration, 96% of incumbents in bilingual supervisory positions met the language requirements of their position

65% of bilingual supervisory positions required Level C proficiency in oral interaction

96% of incumbents who offer personal and central services in both official languages meet the language requirements of their position

37% of bilingual positions that offer personal and central services require Level C proficiency in oral interaction

2.1 Summary

Part V of the Act deals with language of work. It aims to foster the full recognition of both official languages in the federal public service.

An analysis of the reviews submitted by institutions between 2019 and 2022 shows that, all too often, federal employees are still unable to work in the official language of their choice. Table 2 shows that less than 90% of federal institutions comply with each of the obligations the Act creates with respect to language of work. Worse still, only less than two out of three federal institutions “nearly always” allow their employees to draft documents in the official language of their choice (60%) or ensure almost always that their management communicates regularly in English and French with its staff (61%). Less than one in two institutions “nearly always” conducts truly bilingual meetings (45%).

This does not appear to be due to a lack of language proficiency. Almost all employees who must provide personal and central services in both English and French (96%) and almost all incumbents of bilingual supervisory positions (96%) in the core public administration meet the language requirements of their position.

| Questions | 2016–19 | 2019–22 |

|---|---|---|

In regions designated bilingual for language of work |

||

| It is possible for employees to write documents in their official language of choice. | 59% | 60% |

| Meetings are conducted in both official languages, and employees may use the official language of their choice. | 50% | 45% |

| Incumbents of bilingual or either/or positions are supervised in the official language of their choice. | 76% | 74% |

| Personal and central services are provided to employees in the official language of their choice. | 86% | 88% |

| The institution offers employees training in the official language of their choice. | 73% | 81% |

| Documentation and regularly and widely used work instruments and electronic systems are available to employees in the official language of their choice. | 81% | 82% |

In regions designated unilingual for language of work |

||

| Documentation and regularly and widely used work instruments and electronic systems are available in both official languages for employees who are responsible for providing bilingual services to the public or to employees in bilingual regions. | 87% | 84% |

In all regions |

||

| Senior management communicates with employees on a regular basis in both official languages. | 80%Footnote 8 |

61% |

2.2 Language of writing

Only 60% of federal institutions, compared with 59% in 2016–19, reported in their most recent review that their staff were “nearly always” able to draft documents in the official language of their choice. This very low proportion is partly due to the fact that many French-speaking employees continue to feel that they have to write in English, which is consistent with what Patrick Borbey and Matthew Mendelsohn noted in their 2017 report on language of work (a report submitted to the Clerk of the Privy Council).

Best practice

Transport Canada employees are encouraged to write in English or French at the outset of an operation. For example, Navigation Protection Program officers prepare fact sheets on new ministerial orders in the language of their choice. To ensure that they receive feedback from all of their colleagues, their drafts are translated into English or French, as applicable, before being circulated internally. Once proposed changes have been reviewed and incorporated, the final version of the fact sheet is edited, translated and published.

2.3 Languages at meetings

Significant improvement is also needed in the area of languages used in meetings. Only 45% of institutions reported that during the 2019–22 cycle, meetings in regions designated bilingual were “nearly always” conducted in both official languages. This is a five percentage-point drop from 2016–19, which shows that leadership is still lacking in too many federal institutions.

Best practice

Employment and Social Development Canada uses a variety of strategies to support effective and inclusive bilingual meetings. Managers remind employees at meetings that they can use either English or French. For virtual meetings, tools (backgrounds, for example) allow users to make it clear that they are prepared to use either official language. Checklists suggest rescheduling a meeting when the material to be reviewed is not bilingual. The Department uses automatic production of English or French subtitles when using videoconferencing platforms.

2.4 Language of employee supervision

Managers and supervisors are required to supervise employees working in a region designated bilingual in the official language of their choice when they occupy bilingual or either/or positions. This rule is too often ignored. In the 2019–22 cycle, only 74% of institutions “nearly always” followed this rule, down two percentage points from 2016–19.

Almost all incumbents of bilingual supervisory positions (96%) in the core public administration meet the language requirements of their position. They make up 31.6% of supervisory positions. In contrast, in institutions that are not part of the core public administration but have offices in regions designated bilingual for language of work, only 78% of managers who are required to be bilingual are actually able to perform their supervisory functions in both official languages.

2.5 Personal and central services

According to data collected between 2019 and 2022, 88% of federal institutions “nearly always” provide employees in regions designated bilingual with personal and central services (for example, assistance with their pay or computer network) in the official language of their choice. This is an increase of two percentage points.

Almost all employees who provide personal and central services in both official languages (96%) in the core public administration meet the language requirements of their position. They make up 72.5% of the staff assigned to personal and central services. In institutions not part of the core public administration with offices in regions designated bilingual, 40% of internal service positions are bilingual.

2.6 Training and professional development

In bilingual regions, federal institutions must ensure that the training and professional development services they offer to their employees are provided in the official language preferred by the employee. According to the data for 2019–22, 81% of organizations required to answer this question say they “nearly always” meet this requirement, an eight percentage-point increase from 2016–19.

Best practice

All mandatory training courses offered to employees by Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada are available in both official languages, as stipulated in the Department’s Continuous Learning Policy. Employees are therefore able to take their training in the official language of their choice. In addition, a learning program for mandatory training is available on the departmental intranet in both official languages.

2.7 Communicating with staff

In the 2019–22 cycle, only 61% of federal institutions said that, in general, their senior management “nearly always” communicates with employees in both English and French. More leaders should use both official languages in their formal encounters with their staff and also in their day-to-day interactions with employees (for example, in the hallway or at the coffee machine).

However, in the 2022 Public Service Employees Survey, 76% of public servants said that the senior managers in their department or agency use both official languages in their interactions with employees. Perceptions are similar between English-speaking (76%) and French-speaking (75%) public servants. Only 10% of all the respondents provided negative answers.

Best practice

The performance agreements of Employment and Social Development Canada (ESDC) executives state that they must regularly use both official languages. Meetings chaired by senior management in regions designated bilingual for language of work purposes are held in both official languages, and a number of tools and guidelines are available on the departmental intranet to help managers and executives ensure that meetings are chaired effectively in keeping with the equality of English and French. Managers are encouraged to lead by example and to use their second official language regularly. ESDC’s Portfolio Management Board, a committee composed of the five deputy ministers and all assistant deputy ministers, has approved a number of measures, some specifically for senior management, to enhance language security and thereby promote bilingualism within the Department.

2.8 Documentation and working tools

Under the Act, employees in bilingual regions have the right to access documentation (such as instruction manuals, procedures, guides and forms) and regularly and widely used work instruments (keyboards, for example) and electronic systems (such as spreadsheets or word-processing software) in English or French. As in the previous cycle, just over four out of five federal institutions (82%) say they “nearly always” uphold this right. The Act gives the same right to federal employees in unilingual regions who are required to provide services to the public in English and French or to employees in bilingual regions. According to the reviews, 84% of institutions “nearly always” make it possible for their staff to exercise this right. In the previous cycle, the figure was 87%.

2.9 Conclusion

Significant shortcomings remain in the implementation of Part V of the Act in 2019–22. In particular, far too many institutions still do not give their employees the right to prepare documents in the official language of their choice or to participate in meetings using English or French. In last year’s report, TBS stated that it would increase its interventions in the coming years to improve the language-of-work situation. In fact, TBS’s Official Languages Centre of Excellence has repeatedly addressed the language insecurity of employees and executives — and how to overcome it in order to create a workplace that is truly conducive to the use of both official languages. Its training sessions for official languages champions and leaders have also dealt with the language rights of employees. In addition, institutions shared TBS’s reminder about safeguarding linguistic duality in a remote work context.

Chapter 3. Federal institutions and the participation of English-speaking and French-speaking Canadians

In this section

3.1 General situation

Under Part VI of the Act, federal institutions are required to ensure that Anglophones and Francophones have equal opportunities for employment and advancement, while applying the merit principle in their human resources management approaches. Institutions must also ensure, taking into account factors such as their mandate and the location of their offices, that their workforce adequately reflects the official language communities in Canada. To achieve this, they could, for example, take part in job fairs held in Anglophone or Francophone communities or publish job advertisements in Anglophone or Francophone community media.

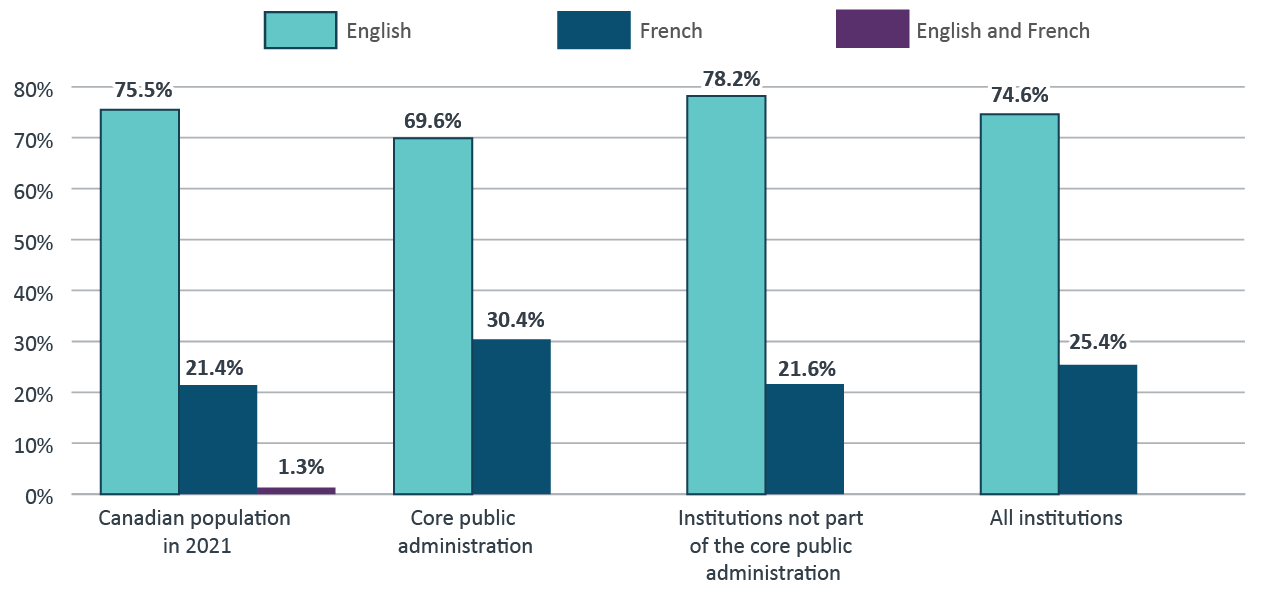

Graph 1 - Text version

Linguistic representation within the federal public service: Anglophones in the Canadian population in 2021: 75.5%, Francophones, 21.4%, and 1.3% that said that English and French are both their official languages; Anglophones in the core public administration: 69.6%, and Francophones, 30.4%; Anglophones in institutions that are not part of the core public administration: 78.2%, and Francophones, 21.6%; Anglophones in all the institutions, 74.6%, and Francophones, 25.4%. Sources: Census 2021; Positions and Classification Information System and Official Languages Information System as of March 31, 2022.

According to the reviews, 85% of federal institutions took steps in the 2019–22 cycle to ensure that the composition of their workforce tended to reflect that of the population.

As Chart 1 shows, as of March 31, 2022, the participation rate in the core public administration was 69.6% for Anglophones and 30.4% for Francophones. In federal institutions not part of the core public administration, the rates were 78.2% and 21.6% respectively. Across all institutions subject to the Act, Anglophones made up 74.6% of the workforce and Francophones 25.4%. These percentages are in line with those in the 2021 Census of Population, which showed that 75.5% of the population had English as their first official language and 21.4% had French (1.3% of respondents reported both French and English as their first official languages).

3.2 Situation of specific groups

Official language communities are well represented in federal institutions and their offices in the provinces and territories. That said, it is worth noting that English-speaking Quebecers outside the National Capital Region make up only 11.9% of the core public administration but account for 13.0% of the Quebec population (16.9% if those who answered “French and English” in the 2021 Census are counted).

Currently, 41.7% of all core public administration employees occupy a bilingual position. The percentage is somewhat lower for some employment equity groups: 32.7% of Indigenous people, 35.6% of visible minorities and 40% of persons with disabilities are in a bilingual position. Worth noting is the fact that 96.2% of Indigenous people, 95.3% of visible minorities and 95.6% of persons with disabilities meet the language requirements of their position, with the average for all employees being 95.9%.

3.3 Conclusion

At present, the composition of the federal public service is such that, on the whole, both Anglophones and Francophones can identify with it. The challenge over the next few years will be to take the necessary steps to ensure that this remains the case.

Best practice

Recruiting English-speaking employees in Quebec is an issue for Public Services and Procurement Canada (PSPC). To remedy this situation, PSPC’s Quebec office formed a partnership with an English-language CEGEP. The goal is to recruit students for co-op or summer jobs and then bring them on as permanent employees after graduation.

Best practice

The National Research Council Canada (NRC) is working with the Association francophone pour le savoir (ACFAS) and French-language universities to promote careers in science and increase the size of the pool of French-speaking researchers. The NRC also adopted a Canada-wide recruitment approach to increase opportunities for members of underrepresented groups such as Francophone minority communities to pursue careers in the federal public service.

Best practice

The Vancouver Airport Authority and its business partners are looking to serve the public in English and French. To achieve this, the Authority is making targeted efforts to recruit French-speaking volunteers, offering French language training to customer experience managers and volunteers, and assigning key customer relations management roles to French-speaking employees.

Chapter 4. Institutions and management of the official languages file

In this section

4.1 Summary

Compliance with the Act depends on establishing rigorous official languages management processes. This section discusses the human resource management, governance and monitoring measures that institutions have taken to create and implement these processes.

Analysis of the reviews submitted between 2019 and 2022 shows that few of the management processes that institutions are expected to use are being implemented at the expected level. For example, only 5 of the 19 processes shown in Tables 3, 4 and 5 below are “nearly always” applied by 90% or more of institutions. While institutions’ performance on the other 14 processes is not what it should be, it is particularly poor on four of them. Less than 60% of federal institutions are sufficiently concerned with providing language training to their employees, building a good environment for post-language training, taking official languages into account in performance agreements, and including official languages on the agenda of senior management meetings.

The situation has not really improved since the last cycle. As a result, 13 of the 19 indicators measured remained unchanged or declined slightly between 2016–19 and 2019–22.

4.2 Human resources management

Federal institutions must ensure that they implement various human resources management practices to strengthen their capacity to provide quality bilingual services to the public and their employees. Table 3 shows some shortcomings in this area.

In its examination of the reviews, TBS found that only 71% of federal institutions “nearly always” had the necessary human resources to fulfill all of their language obligations. This is a three percentage-point decrease from the 2016–19 cycle.

Federal institutions take various measures to ensure that they have staff who are able to respect the language rights of federal employees and members of the public.

| Questions | 2016–19 | 2019–22 |

|---|---|---|

| Overall, the institution has the necessary resources to fulfill its linguistic obligations relating to services to the public and language of work. | 74% | 71% |

| The language requirements of bilingual positions are established objectively. Linguistic profiles reflect the duties of employees or their work units and take into account the obligations with respect to service to the public and language of work. | 83% | 81% |

| The institution objectively reviews the linguistic identification of positions during human resources activities such as staffing, reorganizations or reclassifications. | N/AFootnote 9 |

96%Footnote * |

| Bilingual positions are staffed by candidates who are bilingual upon appointment. | 81% | 74% |

| If a person is not bilingual, administrative measures are taken to ensure that the public and employees are offered services in the official language of their choice. | 94%Footnote * |

94%Footnote * |

| Language training is provided for career advancement. | 48% | 50% |

| The institution provides working conditions conducive to the use and development of the second-language skills of employees returning from language training and, to that end, gives employees all reasonable assistance to do so, particularly by ensuring that they have access to the tools necessary for learning retention. | 62% | 57% |

As shown in Table 3, 81% of institutions, slightly less than in the previous cycle (83%), “nearly always” work to objectively define the language requirements associated with bilingual positions. Ultimately, this ensures that a person is comfortable enough in both official languages to work in a job where a particular level of proficiency in English and French is required (reading comprehension, writing, oral interaction) to perform certain tasks. Similarly, 96% of institutions “nearly always” review how a position was designated when it is staffed, reclassified or affected by a reorganization.

Best practice

The Public Prosecution Service of Canada encourages the members of hiring panels to take training on unconscious bias to minimize the risk that such bias will negatively affect the recruitment of members of minority language communities. Kick-off meetings for any staffing process are specifically intended to answer questions such as “What are the current language requirements for this position?”, “Do these requirements accurately reflect the duties of the position?”, “If similar positions exist, would it be advantageous to create a pool to fill them with candidates with various language profiles?” and, for bilingual positions, “Is the pool of potential candidates adequate?”.

Hiring candidates who are sufficiently fluent in both English and French to staff designated bilingual positions is another important human resource management practice. An examination of the reviews submitted between 2019 and 2022 shows that 74% of institutions (seven percentage points less than in 2016–19) almost always recruit individuals who are already bilingual at the expected level when appointed to a position. In addition, 94% of institutions surveyed in the 2019–22 cycle and the previous cycle reported taking specific administrative measures to ensure that services to the public and to employees remained of high quality in both English and French when the person assigned to a position was not as bilingual as they needed to be for the position.

Best practice

In 2021–22, Shared Services Canada conducted an extensive review to determine the level of English or French proficiency required to perform the key tasks identified in its job descriptions. This helped the Department improve its automated grid for determining the language requirements of a position. In addition, the Department maintains dashboards to measure its language capabilities, track its language training efforts and manage complaints.

Offering staff the opportunity to grow by improving their official bilingualism and applying their language skills on the job is another best practice, one that far too few institutions have implemented to date. Between 2019 and 2022, only one in two federal institutions “nearly always” ensured that English or French language training was offered to employees. In addition, fewer than two in three (57%, down five percentage points from 2016–19) said they “nearly always” provided employees with working conditions and tools (software for second-language writing, for example) that support language skills retention.

TBS is paying special attention to these issues, as shown in Chapter 6, which describes efforts to develop a new language training framework.

Best practice

The Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) has begun a pilot project to hire its own full-time second-language teachers. Phase 1 of the project will focus on French as a second language. The selected teachers – two from Federal Policing and one from National Division – will deliver a virtual course and provide one-on-one support to participants. If Phase 1 is successful, the RCMP will add English as a second language.

Best practice

The Canadian Food Inspection Agency helps its employees maintain their second-language skills through activities in which employees can test and develop their knowledge, such as lunch-and-learns. Thirty-five employees are trying out this program on a voluntary basis under the supervision of second-language teachers. Some 130 employees are participating.

4.3 Governance of official languages

Governance of official languages refers to mechanisms of various kinds, such as those shown in Table 4, that are put in place by an institution to ensure compliance with the Act, the achievement of language targets and the prevention of risks. Overall, as Table 4 shows, governance is a weak point that needs to be addressed in the coming years.

Specifically, 61% of all institutions (three percentage points more than in 2016–19) currently have a separate official languages action plan or have included in another planning instrument (such as their strategic plan) specific and comprehensive objectives for the parts of the Act relating to communications with and services to the public (Part IV), language of work (Part V), participation of English-speaking and French-speaking Canadians (Part VI), and/or advancement of English and French (Part VII). However, preparation is the key to success, and you can only improve what you decide to measure.

Best practice

Fisheries and Oceans Canada has three-year action plans for official languages. The 2020–23 plan describes in detail the expected results for each part of the Act. As Fisheries and Oceans Canada is a decentralized institution, its action plan is not wall-to-wall, so that the specific situations of its various units can be accommodated. For example, the Maritimes Regional Office has its own three-year official languages work plan. The Department has also prepared a report measuring its progress on official languages. The report describes the initiatives implemented after the Department applied the Official Languages Maturity Model developed by the Office of the Commissioner of Official Languages.

Another good governance measure is the inclusion of performance targets for management. Where warranted (based on the institution’s mandate, for example), the inclusion of targets in performance agreements sends a strong message to executives and managers that full compliance with the Act is a fundamental value. It also assists in the proper evaluation of management personnel. Yet only 59% of federal institutions (just three percentage points better than in 2016–19) “regularly” ensure that such targets relating to the implementation of Parts IV through VII of the Act are included.

Best practice

At Infrastructure Canada, executive performance agreements include objectives pertaining to Parts IV, V, VI and VII of the Act. All senior managers in the Department are rated on their ability to ensure that managers and supervisors in bilingual positions are actively involved in creating a work environment conducive to the use of both official languages and that the language requirements of positions are determined objectively. Senior managers must also individually commit to “creating a work environment conducive to the use of both official languages by interacting with employees in the language of their choice and ensuring that meetings are conducted in both official languages.”

To ensure that language issues are taken into account effectively at all levels of an institution, it is also important to include them “regularly” in the agenda of management meetings. According to the 2019–22 cycle reviews, this is the case in 59% of large institutions. This percentage is unchanged from 2016–19.

Best practice

During the 2021–22 fiscal year, the Canadian Food Inspection Agency’s Official Languages Centre was invited to attend seven branch management committee and executive meetings and present information about the Act, the Official Languages Maturity Model, complaints received under the Act, compliance with active offer rules, language training and second-language evaluations.

Other official languages coordinating bodies also play a role. In this regard, the reviews show that in 76% of institutions (eight percentage points less than in 2016–19),Footnote 10 the Champion (or Co-Champion) and those responsible for Parts IV, V, VI and VII of the Act meet “regularly” to discuss official languages issues. Reviews submitted between 2019 and 2022 show that 69% of institutions (down from 73% in the previous cycle) have an internal committee or network that meets frequently to help them fulfill their language obligations and responsibilities effectively.

Best practice

Canada Post established a body called the Official Languages Board, which is composed of the directors general responsible for the obligations under Parts IV, V, VI and VII of the Act. This executive forum meets quarterly. Strategic, proactive discussions are held on current and emerging official languages risks, plans to mitigate those risks, and approaches to improve compliance with the Act.

| Questions | 2016–19 | 2019–22 |

|---|---|---|

| The institution has a distinct official languages action plan or has integrated precise and complete objectives in another planning instrument in order to ensure that its obligations with regard to Parts IV, V, VI and/or VII of the Official Languages Act are met. | 58% | 61% |

| Taking into consideration the institution’s size and mandate, performance agreements include performance objectives related to Parts IV, V, VI and VII (section 41) of the Act, as appropriate. | 56% | 59% |

| Obligations arising from Parts IV, V, VI and VII (section 41) of the Act are on the Senior Management Committee’s agenda. | 59% | 59% |

| The Champion (and/or Co-Champion) and the person or persons responsible for Parts IV, V, VI and VII (section 41) of the Act meet to discuss official languages files. | 84% | 76% |

| An official languages committee, network or working group made up of representatives from different sectors or regions of your institution holds meetings to deal horizontally with questions related to Parts IV, V, VI and VII (section 41) of the Act. | 73% | 69% |

4.4 Monitoring

Establishing monitoring mechanisms enables federal institutions to track their official languages actions, identify shortcomings to be remedied or areas for improvement, and ensure rigorous accountability. While some monitoring practices are well established in institutions, others are not sufficiently ingrained.

| Questions | 2016–19 | 2019–22 |

|---|---|---|

| Measures are regularly taken to ensure that employees are well aware of the federal government’s obligations under Parts IV, V, VI, and VII (section 41) of the Act. | 90%Footnote * |

90%Footnote * |

| Activities are conducted throughout the year to measure the availability and quality of services offered in both official languages (Part IV). | 71% | 66% |

| Activities are conducted to periodically measure whether employees can use their official language of choice in the workplace (in regions designated bilingual for language of work) (Part V). | 78% | 76% |

| The deputy head is informed of the results of monitoring activities. | 89% | 92%Footnote * |

| Mechanisms are in place to determine and document the impact of the institution’s decisions on the implementation of Parts IV, V, VI, and VII (section 41) of the Act (such as adopting or reviewing a policy, creating or abolishing a program, or establishing or closing a service location). | 72% | 69% |

| Audit or evaluation activities are undertaken, by either the internal audit unit or other units, to evaluate to what extent official languages requirements are being implemented. | 66% | 54% |

| When the institution’s monitoring activities or mechanisms reveal shortcomings or deficiencies, steps are taken and documented to quickly improve or rectify the situation. | 94%Footnote * |

96%Footnote * |

The reviews for the last two cycles (Table 5) show that 90% of federal institutions regularly take steps to ensure that their employees are aware of their linguistic obligations (cited as a best practice in the Borbey-Mendelsohn report on bilingualism in the workplace). In 2016–19 and 2019–22, more than 9 out of 10 institutions also kept the deputy head informed of official languages monitoring activities and took prompt action when shortcomings were uncovered.

However, the 2019–22 reviews show that many institutions are still slow to adopt some highly desirable monitoring practices. Specifically, only 66% of federal institutions conduct activities (such as informal evaluations, spot checks and surveys) to measure the availability and quality of the services they offer to the public in English and French, and 76% do so to measure whether employees can use the official language of their choice at work. Both of these figures are a few percentage points lower than in the 2016–19 cycle.

Best practice

Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation includes questions on official languages in its quarterly employee engagement survey. It also monitors, on an annual basis, the actions taken by service providers acting on its behalf to promote English and French. In addition, it established a robust official languages review process in conjunction with the partners that support its technological and organizational transformation to ensure that its employees have access to its systems in their preferred language.

Similarly, only 69% of institutions have mechanisms (such as completing the checklist created by the Treasury Board) to define the nature and extent of the impact of their decisions on official languages (for example, to review a policy or close an office). Again, the results are down slightly from the previous cycle.

Best practice

The members of the Correctional Service Canada Executive Committee developed a guide entitled “Official Languages Lens in the Decision-Making Process.” The guide takes into account the official languages requirements for the preparation of Treasury Board submissions. Any initiative submitted to the Committee for approval must now include a systematic analysis of its linguistic effects.

Lastly, only one in two institutions (54%) in 2019–22, compared with two out of three (66%) in 2016–19, used audits or evaluations to measure the level of compliance with official languages obligations.

Best practice

Each quarter, the Canadian Air Transport Security Authority (CATSA) randomly selects passengers for a survey. The survey has questions about the availability of services in English and French. CATSA also monitors on a daily basis whether bilingual personnel are available to provide services at designated Class 1 airports, such as Pearson, Stanfield or Pierre Elliott Trudeau (including ensuring that at least one bilingual screening officer is present at each pre-board screening checkpoint). CATSA also makes periodic visits to other designated bilingual airports. The results of these monitoring activities are entered into a system and used in the preparation of official languages reports.

4.5 Conclusion

Institutions are using some of the mechanisms or processes required to ensure compliance with the various parts of the Act. More than 90% of them apply some of the human resources management, governance and monitoring best practices that support the advancement of English and French. For example, almost all institutions report conducting the language designation exercise for positions objectively and ensuring that the deputy head is informed of the results of monitoring activities. However, some official languages management practices are not sufficiently widespread, which contributes to the shortcomings noted in the various sections of this report.

Chapter 5. Official languages and crisis situations

In this section

5.1 Institutional measures

Federal institutions have an obligation to comply fully with the provisions of the Act both during crises and in normal circumstances. Marked by the pandemic, 2021–22, like the previous year, presented significant challenges for many institutions, either because there was higher demand for their digital or telephone services or because remote work and virtual meetings became the norm.

As shown in Table 6, most institutions surveyed that year reported that they had taken steps to address the pandemic while meeting their linguistic obligations.

| Questions | 2020–21 | 2021–22 |

|---|---|---|

| Official languages are included in the institution’s emergency preparedness and crisis management planning. | 73% | 92%Footnote * |

| Steps were taken to ensure that external communications were in the public’s preferred official language during the COVID-19 pandemic. | 100%Footnote * |

100%Footnote * |

| Steps were taken to ensure that internal communications were in the employees’ preferred official language of during the COVID-19 pandemic. | 100%Footnote * |

100%Footnote * |

Ninety-two percent say they have incorporated official languages into their emergency preparedness and their crisis management plan, a 19 percentage-point improvement over 2020–21, when the issue was first addressed.

In addition, 100% of the federal institutions that submitted a review in 2021–22 say they have taken various measures to ensure compliance with the part of the Act regarding communications with and services to the public or the part on language of work. Those institutions made sure that notices and alerts were in both official languages, that their news conferences were held in English and French, and that more staff were assigned to bilingual front-line services, to name just a few measures. They also communicated in both languages with equal care, held their meetings concerning the pandemic in both English and French, and posted bilingual signage in their workplaces.

In 2021–22, the Public Service Commission (PSC) continued to deal with the pandemic by working to facilitate institutions’ second-language evaluation efforts. In particular, it extended the validity period of existing evaluation results. It administered Level B and C tests remotely. Where the use of videoconferencing was an accessibility barrier for the test taker, the PSC provided an alternative evaluation mechanism. It also created unsupervised online tests to measure the reading and writing proficiency of many applicants.

5.2 Leadership

These positive results, it should be noted, are largely due to the efforts of the interdepartmental working group on bilingual communications in emergency or crisis situations that was established in 2020–21.

Piloted by TBS with the support of representatives from the Privy Council Office, Canadian Heritage, Public Safety Canada and the Translation Bureau, the group developed a multi-pronged strategy that includes strengthening instruments for official languages governance in emergencies, enhancing the bilingualism of positions responsible for crisis communications, and sharing knowledge on linguistic best practices in difficult times.

Best practice

During the year, Shared Services Canada (SSC) tested and communicated the protocol for rapid translation of urgently required texts, sometimes outside regular hours. SSC also reviewed the processes used to provide thorough revision of translated texts (the contribution of bilingual employees ensures that documents are of equal quality in both official languages).

5.3 Conclusion

Because of the pandemic, the last few years have been difficult ones for Canadians and for federal employees. There were definite shortcomings in the area of official languages at the beginning of the crisis. However, the leadership shown by TBS and the strong collaboration it developed with its partners ensured that, on the whole, those shortcomings were remedied.

Chapter 6. Official languages and TBS

In this section

TBS worked to lead or support the development of policies, programs and tools that facilitate the implementation of Parts IV, V and VI of the Act in federal institutions. It also fulfilled its role as official languages coordinator and monitor.

6.1 Ensuring public access to bilingual services

TBS’s work on implementing the Directive on the Implementation of the Official Languages (Communications with and Services to the Public) Regulations is representative of the significant efforts the institution has made to ensure that the public has access to quality services in English and French.

In the fall and winter of 2021–22, experts from TBS’s Official Languages Centre of Excellence met with various key players in the federal public administration, including the persons responsible for official languages in institutions (PROLs) and members of the Committee of Assistant Deputy Ministers on Official Languages (CADMOL), TBS’s Policy Committee, the Council of the Network of Official Languages Champions, and the Human Resources Council to discuss the new Directive, its effects and its application. The team of specialists from the Centre of Excellence also held discussions on the issue with external stakeholders, including representatives of the Office of the Commissioner of Official Languages, the Quebec Community Groups Network (QCGN), the Fédération des communautés francophones et acadienne du Canada (FCFA) and the Ministers’ Council on the Canadian Francophonie.

6.2 Enhancing bilingualism and diversity and inclusion in the public service

In 2021–22, TBS took determined action to strengthen bilingualism in the workplace.

In collaboration with Canadian Heritage and the Council of the Network of Official Languages Champions, TBS co-led the work of organizing the Best Practices Forum on Official Languages, which considered language training in the federal public service. It also organized an awareness and training event for PROLs on non-imperative staffing. In addition, it held an official languages bootcamp to help participants better understand the central agencies’ role in bilingualism matters.

The OL Connection newsletter also documents TBS’s work to support the creation of bilingual workplaces. In 2021–22, it included the following topics:

- Amendment of the Directive on Official Languages for People Management

- Extension of the temporary second-language evaluation measures

- Publication of the Guide for Drafting Memoranda to Cabinet – Official Languages Impact Analysis

- Launch of the new System for Official Languages Obligations (SOLO)

- Language rights of employees in the context of telework

- Results of the 2020 Public Service Employee Survey

- Decision tree for staffing executive positions

In 2021–22, TBS’s actions were focused on promoting linguistic duality in federal workplaces and working to make the public service more diverse and more inclusive.

TBS supported the organization of Linguistic Duality Day, an event piloted by the Council of the Network of Official Languages Champions and the Canada School of Public Service that demonstrated that the promotion of English and French can go hand-in-hand with the promotion of diversity and inclusion.

In particular, TBS revised Appendix 2 of the Directive on Official Languages for People Management. The changes will allow for the appointment of executives to bilingual positions even if, because of a long-term or recurring disability (for example, a physical or mental disability), they do not meet the second-language requirements. A presentation was held in April 2021 to provide Champions and PROLs with the necessary information about the amendment and assist them in implementing the Directive.

TBS is also developing a new second-language training framework that will ensure quality instruction for learners. The framework will take into account the specific needs of Indigenous people and persons with disabilities. It will also allow for remote learning.

6.3 Contributing to communities’ development

To help federal institutions meet their obligations under the Act to promote official language communities, TBS participated in various activities, such as the virtual meetings of the Official Languages Community of Practice, where it gave a presentation on the Gascon decision (a 2022 decision in which the Federal Court of Appeal found that the government failed to consider “the importance of the role that Francophone organizations played in the provision of employment assistance services for B.C.’s fragile French-speaking minority community” when it transferred certain employment assistance responsibilities to the British Columbia government) and its likely impact.

Most importantly, TBS issued a new Directive on the Management of Real Property in May 2021. An institution’s real property specialists are now responsible for notifying the Canada Lands Company Limited and official language minority communities of the institution’s intent to dispose of real property. This measure will give Anglophone or Francophone communities the opportunity to quickly inform the government of a province, territory or city of their interest in purchasing a property whose acquisition could further their development.

6.4 Strengthening coordination and accountability

In April 2022, the Government of Canada introduced Bill C-13, which contains important amendments to the Act, notably to better protect and promote the French language by recognizing its status as a minority language in Canada and North America. With the passage of the bill, a series of administrative measures aimed at strengthening official languages coordination and accountability will be taken.

Those measures include the following:

- Create an accountability and reporting framework to guide the federal government’s official languages actions and the implementation of the Act

- Examine official language qualification standards for potential bias and barriers to diversity and inclusion

- Review the minimum second-language requirements for bilingual supervisory positions in regions designated bilingual

- Include official languages requirements for emergency situations in Treasury Board policy instruments

- Strengthen the role of translation and interpretation functions in the federal government, including the role of the Translation Bureau

6.5 Conclusion

TBS plays a central role in the implementation of the various parts of the Act. This includes in 2021–22 the review of over 400 Treasury Board submissions under the lens of “Parts IV, V and VI of the Act.”

TBS is expected to play a greater role in official languages in the coming years. It is already planning all the internal and external measures it will have to take to ensure that it fulfills its role and supports federal institutions effectively so that they can collectively contribute to strengthening linguistic duality in Canada.

Conclusion of the report

A cursory glance at the past shows that the federal public service is more bilingual than ever, and that more and more federal institutions are meeting their obligations under the Act.

However, an analysis of the reviews submitted during the last three-year cycle and previous cycles reveals that progress on official languages is stalled in various areas, that there are still major shortcomings, and that a large percentage of institutions are still slow to systematically undertake all the actions that will make it possible to enhance the place of English and French in Canadian society and in the public service.

More than 50 years after the adoption of the first version of the Act, and nearly 35 years since the last major revision of the Act, TBS intends to rectify this situation by intensifying its monitoring of the way institutions apply official languages policies and programs.

To move things in the right direction, TBS has recently taken a number of steps that are already paying off, including the following.

- It actively supports institutions that will be required to implement the Official Languages (Communications with and Services to the Public) Regulations and that, in many cases, will have to effectively manage a growing number of bilingual offices and service locations. After the reapplication exercise of the Regulations is completed, the proportion of designated bilingual offices is expected to rise from 34.5% to 40%. This means that approximately 700 more offices than in the past will soon be required to provide Canadians with services in both English and French, rather than just unilingual services.

- It will lead an exercise to amend the Directive on the Management of Real Property, in particular to take the situation and needs of official language communities into account when the federal government disposes of real property.

- Its leadership in times of crisis ensured that as the pandemic progressed, institutions increasingly used both official languages effectively to communicate with the public and their employees.

TBS will continue to build on this momentum in the coming years. It is already strengthening its capacity to analyze institutions’ official languages reviews and the various data that they provide. It has begun taking further steps to ensure that institutions have the governance structures, mechanisms and resources required to ensure coherent management of the language file. For example, the language training framework being developed will help federal employees (particularly members of equity-seeking groups) access English or French language training to acquire new skills or consolidate existing ones. At the same time, TBS will continue to provide high-quality advice and guidance to institutions on the implementation and application of Treasury Board policy instruments.

At the end of the day, the public service exists for one reason: to effectively serve all Canadians, both in English and in French. It is important to take steps to make linguistic duality a reality of daily life.

Appendix A: Methodology for reporting on the status of official languages programs

Federal institutions must submit a review on official languages to TBS at least once every three years.Footnote 11 This fiscal year marks the third year of the three-year cycle (2019–22). Eighty-eight organizationsFootnote 12 had to complete a questionnaire on elements pertaining to the application of Parts IV, V and VI of the Act in 2021–22.

Institutions were required to report on the following elements:

- communications with and services to the public in both official languages

- language of work

- human resources management

- governance

- monitoring of official languages programs

These five elements were evaluated mainly by using multiple-choice questions. To reduce the administrative burden on small institutions,Footnote 13 they were asked fewer questions than large institutions. Deputy heads were responsible for ensuring that their institution’s responses were supported by facts and evidence. Table 1 describes the response scales used in the review on official languages for 2021–22.

Table 1

| Nearly always | In 90% or more of cases |

|---|---|

| Very often | Between 70% to 89% of cases |

| Often | Between 50% to 69% of cases |

| Sometimes | Between 25% to 49% of cases |

| Almost never | In fewer than 25% of cases |

| Yes | Completely agree with the statement |

| No | Completely disagree with the statement |

| Regularly | With some regularity |

| Sometimes | From time to time, but not regularly |

| Almost never | Rarely |

| N/A | Does not apply to the institution |

The previous sections outline the status of official languages programs in the 88 institutions that submitted a review this year or, as the case may be, the most recent results from the 168 institutions that submitted a review over the 2019–22 cycle. The statistical tables in Appendix D of this report outline the resultsFootnote 14 for all federal institutions.

Appendix B: Federal institutions required to submit a review for the 2021–22 fiscal year

Eighty-eight federal institutions submitted a review for the 2021–22 fiscal year. The distinction between small institutions and large institutions is based on size. Large institutions were required to respond to a longer questionnaire. Small institutions have fewer than 500 employees. For this fiscal year, airport authorities were also asked to submit an official languages review. The lists of federal institutions that submitted a review for the two previous years of the three-year cycle are available in the Appendix B of the Annual Report on Official Languages 2019–20 and the Annual Report on Official Languages 2020–21.

Large institutions

- Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada

- Air Canada

- Atlantic Canada Opportunities Agency

- Canada Border Services Agency

- Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation

- Canada Post

- Canada Revenue Agency

- Canada School of Public Service

- Canadian Air Transport Security Authority

- Canadian Food Inspection Agency

- Canadian Heritage

- Correctional Service Canada

- Canadian Space Agency

- Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada

- Department of Finance Canada

- Department of Justice Canada

- Employment and Social Development Canada

- Environment and Climate Change Canada

- Fisheries and Oceans Canada

- Global Affairs Canada

- Health Canada

- Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada

- Indigenous Services Canada

- Infrastructure Canada

- Innovation, Science and Economic Development Canada

- Library and Archives Canada

- National Defence

- National Research Council Canada

- Natural Resources Canada

- NAV CANADA

- Privy Council Office

- Public Prosecution Service of Canada

- Public Service Commission of Canada

- Public Services and Procurement Canada

- Royal Canadian Mounted Police

- Shared Services Canada

- Transport Canada

- Treasury Board of Canada Secretariat

- Veterans Affairs Canada

- VIA Rail Canada Inc.

Small institutions

- Canada Council for the Arts

- Canada Economic Development for Quebec Regions

- Canada Infrastructure Bank

- Canadian Museum for Human Rights

- Canadian Museum of Immigration at Pier 21

- Canadian Race Relations Foundation

- Canadian Security Intelligence Service

- Canadian Transportation Agency

- Civilian Review and Complaints Commission for the RCMP

- Copyright Board Canada

- Destination Canada

- Great Lakes Pilotage Authority Canada

- Impact Assessment Agency of Canada

- Military Grievances External Review Committee

- Montréal Port Authority

- National Capital Commission

- National Film Board of Canada

- Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada

- Office of the Commissioner for Federal Judicial Affairs Canada

- Office of the Commissioner of Official Languages

- Office of the Public Sector Integrity Commissioner of Canada

- PortsToronto

- Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada

- Supreme Court of Canada

- Telefilm Canada

- The Correctional Investigator Canada

- The St. Lawrence Seaway Management Corporation

- Trois-Rivières Port Authority

- Western Economic Diversification CanadaFootnote 15

- Windsor-Detroit Bridge Authority

- Women and Gender Equality Canada

Airport authoritiesFootnote 16

- Aéroport de Québec Inc.

- Aéroports de Montréal

- Calgary Airport Authority

- Charlottetown Airport Authority Inc.

- Edmonton Regional Airports Authority

- Fredericton International Airport Authority

- Greater Moncton International Airport Authority Inc.

- Greater Toronto Airports Authority

- Halifax International Airport Authority

- Ottawa MacDonald-Cartier International Airport Authority

- Regina Airport Authority

- Saint John Airport Inc.

- Saskatoon Airport Authority

- St. John’s International Airport Authority

- Vancouver International Airport Authority

- Victoria Airport Authority

- Winnipeg Airport Authority Inc.

Appendix C: Definitions

- “Anglophone”

- refers to employees whose first official language is English.

- “bilingual position”

- is a position in which all or part of the duties must be performed in both English and French.

- “first official language”

- is the language declared by the employee as the one that they primarily identify with.

- “Francophone”

- refers to employees whose first official language is French.

- “incomplete record”

- means a position for which data on language requirements is incorrect or missing.

- “position”

- means a position filled for an indeterminate period or a determinate period of three months or more, according to the information in the Position and Classification Information System (PCIS).

- “resources”

- refers to the resources required to meet obligations on a regular basis, according to the information available in the Official Languages Information System II (OLIS II). Resources can consist of a combination of full-time and part-time employees, as well as contract resources. Some cases involve automated functions, hence the need to use the term “resources” in this report.

- “reversible” or “either/or position”

- is a position in which all the duties can be performed in English or French, depending on the employee’s preference.

Appendix D: Statistical tables

There are four main sources of statistical data:

- Burolis is the official inventory that indicates whether offices have an obligation to communicate with the public in both official languages

- The Position and Classification Information System (PCIS) covers the names and positions of employees working in institutions that are part of the core public administration

The Official Languages Information System II (OLIS II) provides information on the resources of institutions that are not part of the core public administration (in other words, Crown corporations and separate agencies)

The Employment Equity Data Bank (EEDB) provides data based on voluntary declarations by employment equity groups and, for women, the Pay System

March 31 is the reference date of the data in the statistical tables and in the data systems (the Pay System, Burolis, the PCIS, OLIS II and the EEDB).

Notes

Percentage totals may not add up to 100% due to rounding.

The data in this report relating to positions in the core public administration are compiled from the PCIS, except for Tables 15 to 18, which also use the EEDB. Because the data related to official languages are based on the PCIS, they do not match those included in the annual report on Employment Equity in the Federal Public Service. The sum of the designated employment groups does not equal the total of all employees because employees may have chosen to self-identify in more than one group and because employees who identified as male were added to the total.

Pursuant to the Public Service Official Languages Exclusion Approval Order, incumbents may not meet the language requirements of their position for the following reasons:

- They are exempted

- They have two years to meet the language requirements

The linguistic profile of a bilingual position is based on three levels of second-language proficiency:

- Level A: minimum proficiency

- Level B: intermediate proficiency

- Level C: superior proficiency

Table 1