Canada’s first State of youth report: for youth, with youth, by youth

This publication is available upon request in alternative formats.

On this page

- List of figures

- List of acronyms and abbreviations

- Foreword message from the Prime Minister

- Foreword message from the Minister of Diversity and Inclusion and Youth

- Foreword message from the State of Youth Report Youth Advisory Group

- Introduction

- The state of youth 2021 – in their own words

- Conclusion

- Annex A: Glossary of terms

- Annex B: Spotlight on engagement data

- Annex C: Youth Advisory Group and young artist biographies

Alternate format

Canada’s first state of youth report: for youth, with youth, by youth [PDF version - 33.5 MB]

List of figures

- Figure 1. SOYR Youth Engagement Infographic

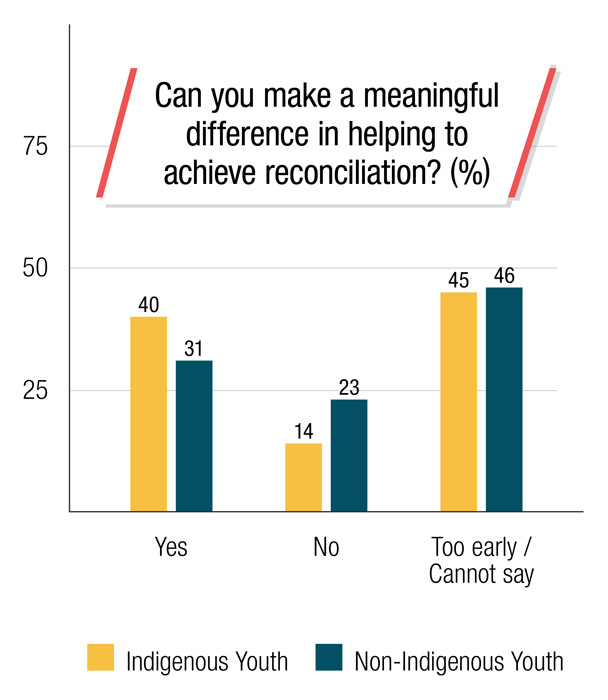

- Figure 2. Can you make a meaningful difference in helping achieve reconciliation.

- Figure 3. Whose Responsibility is Truth and Reconciliation?

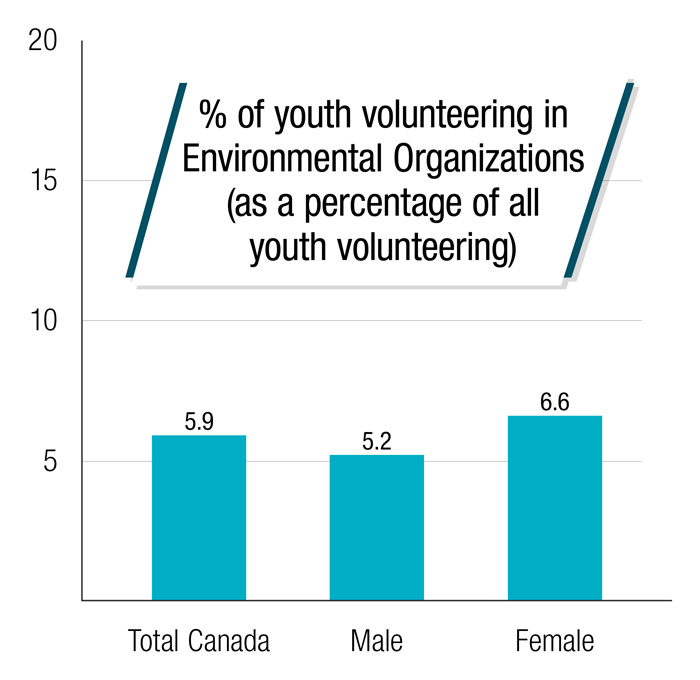

- Figure 4. Percent of Youth Volunteering in Environmental Organizations

- Figure 5. Environment and Climate Action Overall Themes

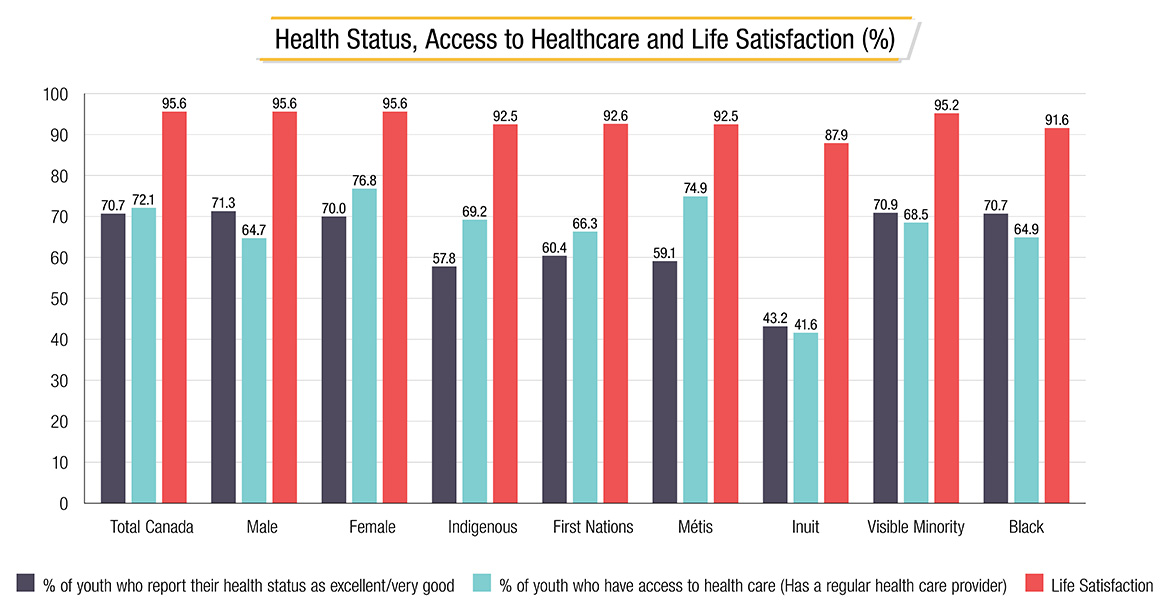

- Figure 6. Health Status, Access to Healthcare and Life Satisfaction

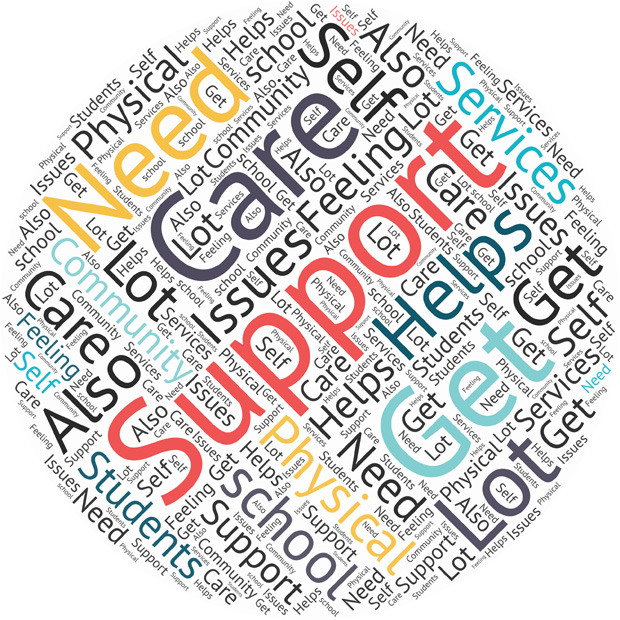

- Figure 7. Health and Wellness Overall Theme

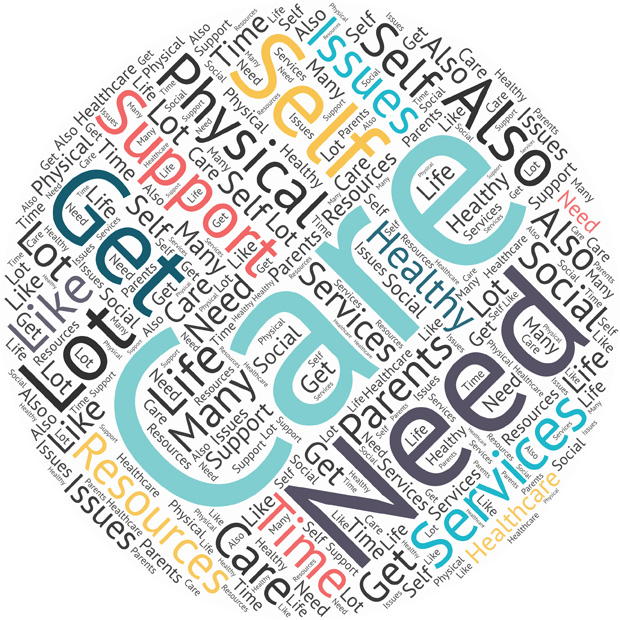

- Figure 8. Mental Health Theme

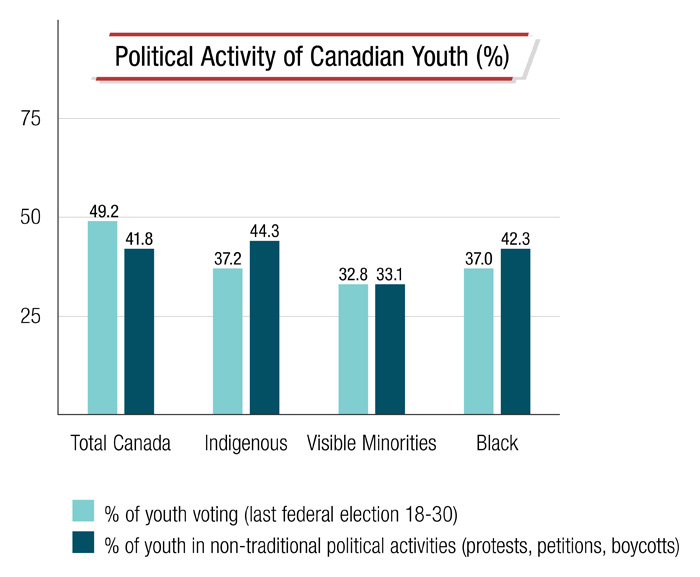

- Figure 9. Political Activity of Canadian Youth

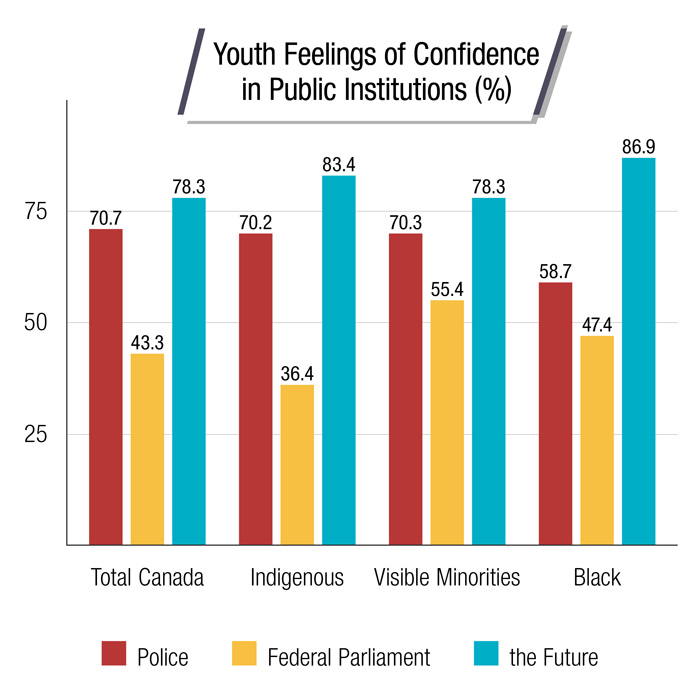

- Figure 10. Youth Feelings of Confidence in Public Institutions

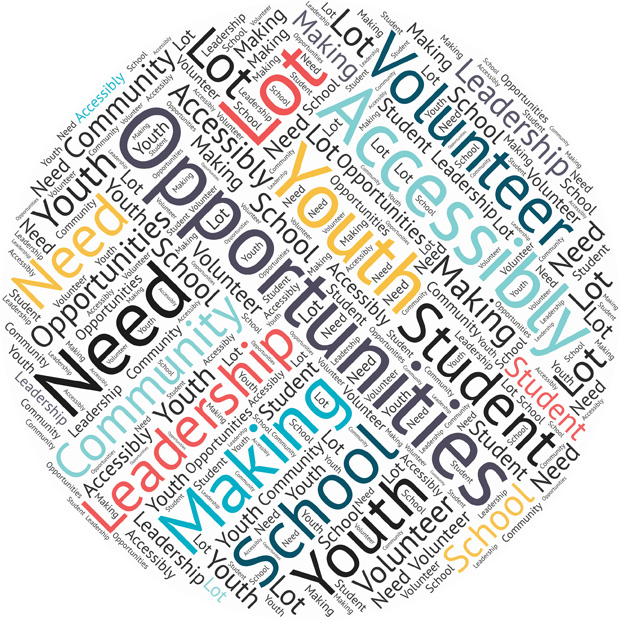

- Figure 11. Leadership and Impact Overall Themes

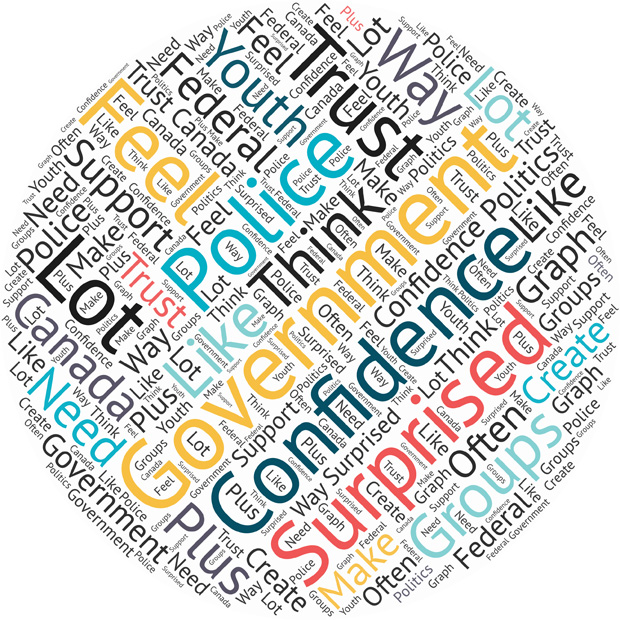

- Figure 12. Government Theme

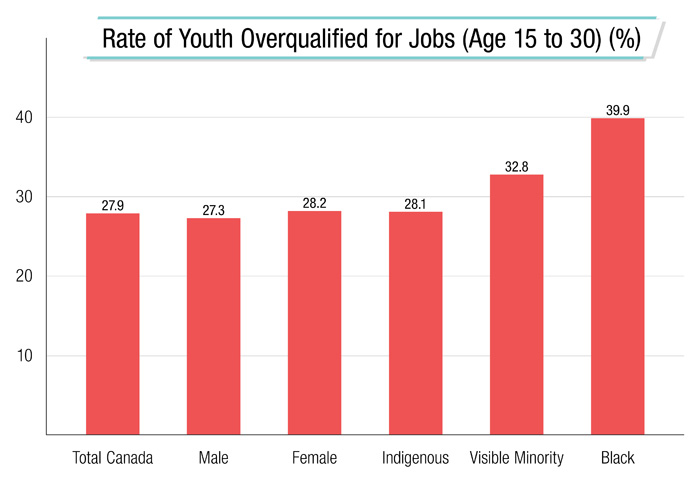

- Figure 13. Rate of Youth Overqualified for Jobs

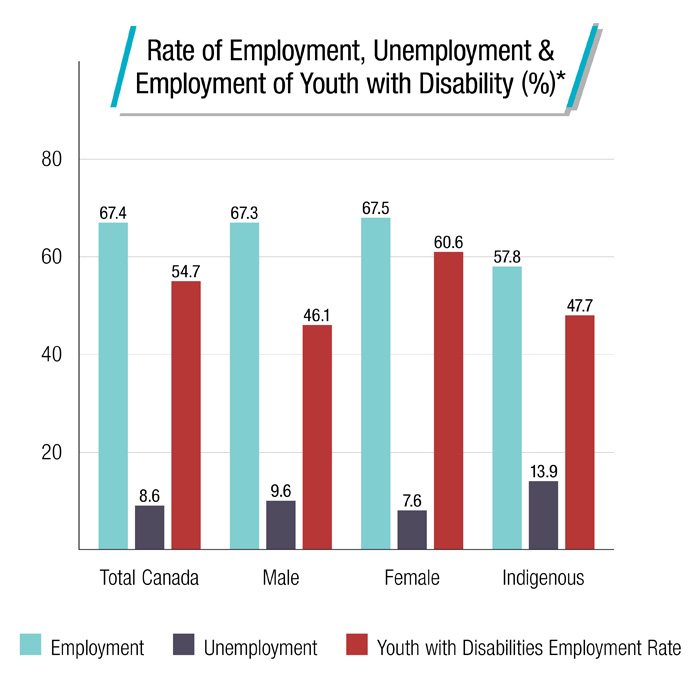

- Figure 14. Rate of Employment, Unemployment and Employment of Youth with Disability

- Figure 15. Employment Overall Theme

- Figure 16. Barriers to Employment

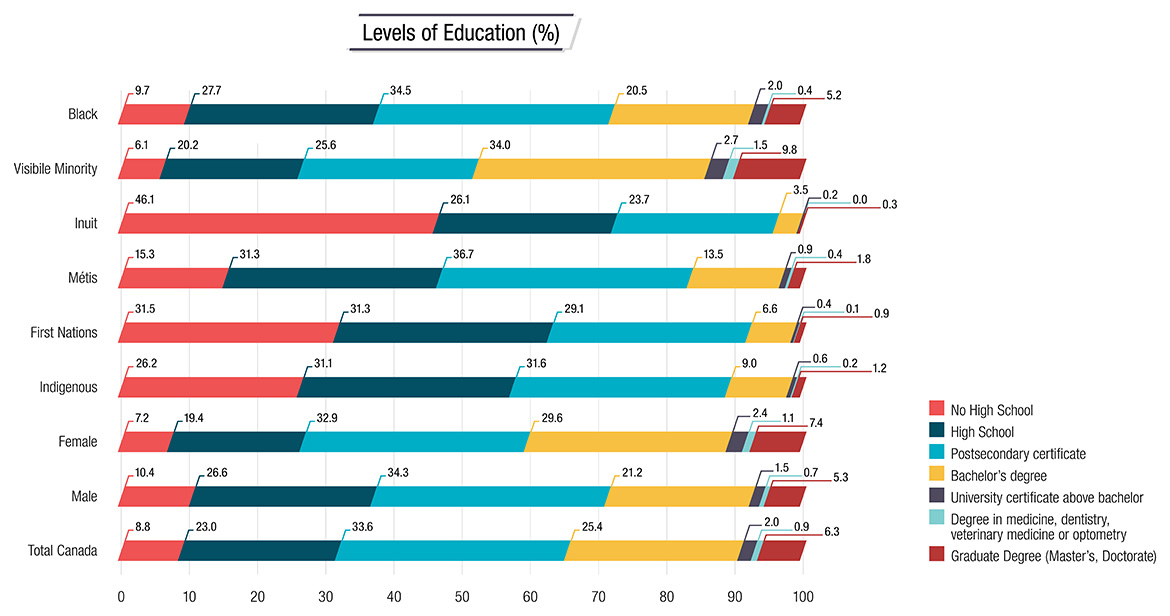

- Figure 17. Levels of Educational Attainment

- Figure 18. Equity Theme

List of acronyms and abbreviations

- 2S

- Two-spirit

- BC

- British Columbia

- CTA

- Call to Action

- K-12

- Kindergarten to Grade 12

- LGBTQ2

- Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, two-spirited

- Portable Document Format

- PhD

- Doctor of Philosophy

- PMYC

- Prime Minister’s Youth Council

- POC

- Persons/people of colour

- SOYR

- State of Youth Report

- STIP

- Science and Technology Internship Program

- SWPP

- Student Work Placement Program

- TRC

- Truth and Reconciliation Commission

- TRU

- Thompson Rivers University

- YAG

- Youth Advisory Group

- YESS

- Youth Employment and Skills Strategy

Foreword message from the Prime Minister

I am happy to welcome the first-ever State of Youth Report. Informed by nearly 1,000 young people of diverse backgrounds from across the country, this report recognizes the contributions of youth in Canada, and their potential to shape a better future for everyone.

Youth in Canada are engaged, resourceful, and resilient. They are the leaders of tomorrow, and of today. They understand the biggest issues facing our country, and they have the ideas and solutions to address them. The report focuses on their largest priorities, including truth finding and reconciliation with Indigenous Peoples, the environment and climate action, health and wellness, leadership and impact, employment, and innovation, skills, and learning. It outlines their important viewpoints on these issues, and introduces their vision for building a better Canada that works for everyone.

The past year has been challenging for everyone as we battled a global pandemic, and youth in Canada have been among those most impacted. They have made immense sacrifices to protect their parents and grandparents, and we must put them at the centre of our recovery as we build back better from this crisis. That is why the Government of Canada has made investments to support vulnerable youth, including those facing barriers to employment, as well as to make it easier for young people to pursue and complete their education, pay down student debt, and find training and work opportunities. Youth in Canada hold our future in their hands, so when we invest in them, we are investing in Canada’s success and long-term prosperity.

I thank the hundreds of young people who contributed to the creation of this report, and all others involved in its preparation. As the previous Minister of Youth, I look forward to advancing this crucial work, both through my Youth Council and the continued implementation of Canada’s first-ever youth policy. The government will continue to listen to the voices of youth in Canada, collaborate with them, and take action to empower them to drive change in their communities and make their dreams a reality.

The Right Honourable Justin Trudeau, P.C., M.P. (he/him/il)

Prime Minister of Canada

Foreword message from the Minister of Diversity and Inclusion and Youth

Canada’s first-ever State of Youth Report is unique in so many ways, and is a reminder that youth across the country are bursting with new and innovative ways of addressing some of our country’s most complex issues.

The recommendations contained in this report are a result of engagement sessions with approximately 1,000 young people, including First Nations, Métis, Inuit, Black and racialized, and LGBTQ2 youth, many of whom are facing barriers to meaningful participation in society. Through my work as Minister of Diversity and Inclusion and Youth, I’ve had the opportunity to meet with many of these youth and I’ve seen how committed they are to building a better country.

Their commitment is not only inspiring, but also a call-to-action in the areas of Leadership and Impact; Health and Wellness; Innovation, Skills and Learning; Employment; Truth and Reconciliation; and Environment and Climate Action. Through the lens of these six topics, this report highlights the opportunities and challenges faced by youth in Canada based on their lived experiences.

They further identify significant issues around environmental justice, access to education and mental health supports, job security, and the ongoing need to have a culturally-sensitive approach to the truth and reconciliation process with Indigenous communities.

Like Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, I believe in the power of youth - which is why it was so important to ensure that this report was developed “for youth, with youth, and by youth”. While it might be the first report of its kind, we know that it is a continuation of our government’s longstanding commitment to build a better future for youth in Canada.

I would like to thank the members of the Youth Advisory Group (YAG), the young artists who contributed their stunning art work, and all the partners convened by the Federal Youth Secretariat, including all the young people who took part in the productive engagement sessions.

The State of Youth Report (SOYR) responds to a commitment in Canada’s Youth Policy, and ensures that the voices of young people are heard, recognized, and reflected in an authentic way in all of our decision making, while also describing some of the programs that are currently offered.

We must also remember that youth in Canada represent a diverse cross-section of society as individuals with unique circumstances based in part on where they live, their stage in life, and their background. These intersectional identities contribute to the rich diversity of our country, but sometimes also hinder youth from reaching their full potential.

With this important context in mind, I invite you to read this report, reflect on the recommendations, and learn more about the state of young people in this country – including the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on their lives.

I truly believe that listening and hearing from our young leaders is the only way we will build a better future for all Canadians.

The Honourable Bardish Chagger (she/her/elle)

Minister of Diversity and Inclusion and Youth

Foreword message from the State of Youth Report Youth Advisory Group

As members of the YAG, we are excited to share Canada’s first-ever SOYR. This report was shaped by youth from every province and territory in Canada. Engagement sessions provided youth with the opportunity to offer insights into their experiences, ideas and solutions on relevant issues and topics directly to governments. Together, 996 young people contributed to this report while bringing forward their lived experiences and opinions.

The youth-identified priority areas are Leadership and Impact; Health and Wellness; Innovation, Skills and Learning; Employment; Truth and Reconciliation; and Environment and Climate Action. We believe that the results of this report and the recommendations brought forward by youth deserve consideration and meaningful actions by all levels of government in Canada. The recommendations and ideas brought forward by youth in Canada in this report should be designed and implemented in partnership with them and their communities.

The YAG will advocate for the results of the SOYR to be communicated through digital and physical channels, so many more people learn about the perspectives and current state of youth in Canada.

We are optimistic that these are not the last conversations and actions that the government will take with and alongside youth. This report is a valuable tool for all governments to engage in dialogue and to work with youth to address the challenges and barriers that exist in Canadian society today.

We look forward to seeing how youth will mobilize in response to this report and how governments will aid them in responding to their needs, wants and desires. If recent world events and global movements have taught us one thing, it is that youth are not voiceless; however, far too often they continue to be ignored. Let us all use this as an opportunity to take action.

Introduction

Youth matter

As Canadians, we believe that youth have the right to not only be heard, but truly listened to and respected. They have a right to equal access to opportunities and supports. When youth reach their full potential, it benefits all Canadians.

“When the Wisdom Keepers speak, all should listen. So it is with youth: when youth speak, all should listen.”

Who are youth in Canada

The term “youth” generally refers to those in the stage of life from adolescence to early adulthood. Looked at numerically, there are over 7 million young people in Canada between the ages of 15 to 29, and they are as diverse as the country itself.

Youth in Canada come from a wide variety of backgrounds, with great diversity in their ethnicitiesFootnote 1, fluency in officialFootnote 2 and non-officialFootnote 3 languages and heritage. They express their identities individually and increasingly self-identify as belonging to certain groups. Canada’s youth are more comfortable and empowered to be who they are. For example, they more commonly identify as gay, lesbian, bisexual, and other sexually diverse identities, in comparison to other age groupsFootnote 4. Inclusivity is also strong amongst youth as a majority of youth have friends from diverse backgroundsFootnote 5.

In addition, youth are full of potential. They are more educatedFootnote 6 than previous generations, and for the most part, digitally well-connectedFootnote 7. Youth's share of the population is highest in the West and the North of Canada, predominantly in towns or large urban centresFootnote 8. Although less likely to vote, they are civically engagedFootnote 9, with youth contributing 23% of all volunteer hours. With these characteristics, youth in Canada are uniquely well-positioned to inform an innovative and inclusive future for everyone.

The stories and experiences of Indigenous youth are also very diverse, as are their languages and cultures. They continue to experience intergenerational trauma and must overcome enormous challenges to succeed in different spheres of their lives. Indigenous youth will shape and inherit the results of Canada’s reconciliation agenda, and play an important role in rebuilding relationships. They are key drivers of social and economic outcomes and their voices are ensuring that no new generation of Indigenous youth is "left behind".

Canada’s Indigenous population is not only youngFootnote 10, but the fastest growing population of young people in the country come from First Nations, Inuit and Métis communitiesFootnote 11. The number of Indigenous youth aged 15 to 30 increased by 39%Footnote 12, compared to just over 5% for non-Indigenous youth from 2006 to 2016Footnote 13.

The data and statistics presented in this report are mainly taken from Statistics Canada. That said, the Government of Canada recognizes the importance of Indigenous data sovereignty, which is the right of a nation to govern the collection, ownership and application of its own data. It acknowledges that the data offered in this report does not include data collected by different Indigenous communities and that the brief portrait presented here is incomplete. The Government of Canada supports First Nations, Inuit and Métis communities to design and implement their respective visions for data governance.

More youth also self-identify as Black (the number has grown to 5.4%Footnote 14). As a growing, civic-minded, innovative and engaged group, there is the opportunity for them to play an important role in designing the future of Canada. However, anti-Black racism remains a major obstacle to their well-beingFootnote 15. Black youth reported having negative experiences with law enforcement agencies, educational institutions, private companies, child services agencies, the judicial system and public services which, compounded, have limited their equal access to employment opportunities, educational attainment and equal and just treatment from systems that are supposed to serve and support them. Despite the significant barriers that have been created for them, Black youth have immense resilience as demonstrated by having a higher desire to achieve a university degree compared with other youth (94% vs 82%)Footnote 16.

What this portrait reveals about LGBTQ2Footnote 17 youth is also incomplete. Existing data suggests that a larger proportion of youth in Canada consider themselves to be either gay or bisexual, as compared with older Canadians (e.g., about 5% to 8% youth versus 2% to 3% of Canadians 31-64 years of age, respectivelyFootnote 18). Homeless Hub estimates that anywhere from 25% to 40% of homeless youth in Canada are LGBTQ2Footnote 19. However, significant data gaps on LGBTQ2 communities in Canada have contributed to a lack of information on LGBTQ2 youth, as well as the unique issues they face. Community engagement activities are underway to inform the development of the first federal LGBTQ2 Action Plan, including a national survey of LGBTQ2 communities. This will contribute valuable data points on LGBTQ2 youth and help to ascertain their realities and needs.

Implementing the Youth Policy

In 2019, the Government of Canada published the country’s first ever Youth PolicyFootnote 20. Thousands of youth across Canada leveraged a robust, inclusive process to weigh in on what matters most to them, and identified six youth priority areas:

- Truth and reconciliation

- Environment and climate action

- Health and wellness

- Leadership and impact

- Employment

- Innovation, skills and learning

The Youth Policy also established 3 guiding principles for youth policy implementation, and flagged select federal initiatives providing supports to Youth in Canada: Canada’s Youth Policy - Canada.ca

The Youth Policy affirmed the need for government to check in with youth at regular intervals, and this first State of Youth Report represents the cornerstone for delivering on this promise. It is the result of focused efforts to better understand youth in Canada and their priorities.

This State of Youth Report is primarily for Canada’s youth. In it, youth should see reflected their hopes and needs, and find programs and initiatives that begin to address them, with the acknowledgement that more needs to be done. This report is also for policymakers, who will develop a better understanding of the desires and expectations of youth in Canada as they call upon them to act. Finally, this report is for youth-serving organizations and adult allies across the country, enabling them to engage with their young people on the topics raised in this report.

What is important to youth today?

In 2020/2021, youth returned to their six priority areas identified in Canada’s Youth Policy as a framework for expressing what is important to youth today. Throughout engagement sessions held for this report, youth shared their perspectives on all priority areas, but clearly 2020/21 was a year like no other.

During this first year of the COVID-19 global pandemic, the health of youth was top of mind. Youth well-being has been dramatically affected in almost every aspect of youth experience. For youth aged 15 to 29, life satisfaction has not only decreased between 2018 and 2020, but it was the lowest among these youth than any other age groupFootnote 21. Additionally, one of the biggest impacts of COVID-19 and related public health measures (such as physical distancing and school closures) was on mental health, particularly for youth.

That said, this report is not dedicated to the global pandemic; youth continue to express their aspirations for the breadth of the priority areas first addressed in the Youth Policy. Youth are resilient: they are a diverse, educated, well-connected and engaged population. They have been particularly challenged by the global pandemic and the insights that they share in this report are coloured by their experiences with COVID-19, but they are not limited by it.

How youth were engaged to produce this report

While an in-person model of youth outreach was originally planned, early State of Youth Report engagement quickly adapted to the new reality imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic. With a continued focus on youth who face barriers or are less often engaged in public discourse, plans were modified to speak with youth virtually, wherever they were at. Despite the challenging contextFootnote 22, youth across Canada rose to the occasion. From August 2020 to May 2021, nearly 1000 youth from all over Canada contributed their experiences, perspectives, insights and expertise.

Research protocol summary:

- Strong research ethics protocolsFootnote 23, to work with youth in good way

- Semi-structured, facilitated online discussions

- 90 sessions hosted by youth-serving organizations, youth facilitators and/or adult allies

- Preferential recruitment of youth facing barriers, those with highly intersectional identities and youth who are less often heard

- Youth included through individual response forms when bandwidth or logistics posed a challenge

- Over 50,000 qualitative data points generated by youth participants

- Qualitative analysis using a Grounded Theory approach [see Annex A- Glossary of terms]

Youth participants also contributed information about themselves through an optional demographics form. Youth across Canada affirmed multiple, intersecting identities when it came to: their Indigenous identities, race, ethnicity, education levels, languages spoken, place of residence, disabilities, mental illness, and identities as LGBTQ2Footnote 24, newcomer/immigrant, youth in care of child welfare authorities, and other distinctions.

During engagement sessions, youth used guides containing Statistics Canada data infographics to stimulate conversation. Youth responded, generating valuable qualitative data. Their perspectives often challenged the information that was presented to them (see Annex B – Spotlight on Engagement Data). Participant responses formed the evidence base for the “State of Youth 2021 - in their own words” section of this report. Furthermore, all quotes that follow were provided by youth during those sessions.

What to expect in this report

This report reflects a commitment and support for youth in Canada. Most importantly, however, this report crystalizes a diversity of youth perspectives and critical thinking, grounded in youth data and expressed by youth themselves. These perspectives are presented in their recommendations, as well as in the illustrations that appear throughout, which are visual interpretations of the priority areas made by young artists specifically for this report. As the State of Youth Report aims to amplify youth voices and self-determination, the words in the following section “The State of Youth 2021 – in their own words” are indeed their own - unfiltered. It is also important to note that youth are affected by, and have views on, all issues affecting our nation – not only those that are typically deemed “youth issues”.

The reader will note that this is not a typical government document. As its title indicates, the State of Youth Report is intended for youth, was informed by engagements with youth and also contains a significant portion drafted by youth. The following groups of youth were engaged in the writing of the State of Youth Report:

Youth authorship of the State of Youth Report

The SOYR Youth Advisory Group (YAG):

- 13 young people identified through partnerships, reflecting Canada’s diversity

- convened to interpret the engagement data and draft The State of Youth 2021 - in their Own Words portion of the report

- not representatives of any group, but as leaders with valuable lived experiences and perspectives

The Prime Minister’s Youth Council (PMYC):

- worked to publish the Youth Policy in 2019

- helped create the engagement guides

- collaborated with the YAG to draft the report

Youth Members of the federal Director General Committee on Youth:

- contributed feedback and information supplements regarding Government of Canada policies, programs and initiatives supporting youth according to the six priority areas

Young Artists:

- youth expressed early on that words are only one way of expressing complex ideas

- six diverse young artists were commissioned to create visual interpretations for each priority area, to complement and punctuate the words shared in this report

As promised in Canada’s Youth Policy, select federal initiatives designed to support young people are highlighted to help raise awareness of programming available to youth. They are provided in call-out boxes to interfere as little as possible with the perspectives expressed by youth.

The members of the Youth Advisory Group have grappled with the youth data for each of the six priority areas, and they have leveraged the opportunity to make a number of recommendations. Embracing the first Policy principle whereby “Youth have the right to be heard and respected”, here is The State of Youth 2021 – in their own words.

The state of youth 2021 – in their own words

Truth and reconciliation

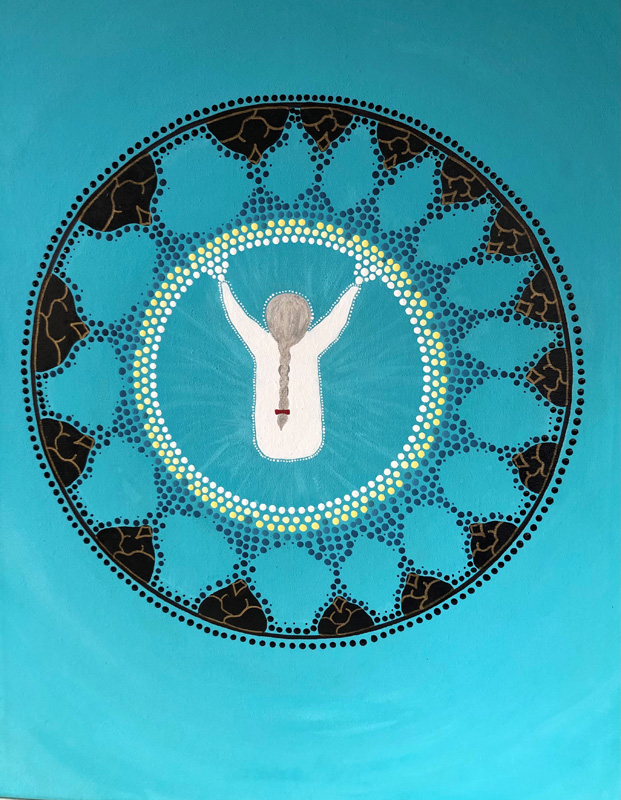

My piece revolves around Reconciliation and what it has meant to us as Indigenous People. I wanted to show the activism and protests for reconciliation over the decades in Canada. I drew inspirations from the activism and protests I saw when I was a child, and the ones that I have been a part of, or ones that had happened near my community.

Introduction

Reconciliation is not a task to be completed, it is a vision for a society where past and current injustices are recognized and addressed. The process of reconciliation must entail significant changes in order to offset the history and current reality of racism and colonization in Canada. The governmentsFootnote 25 must hold themselves accountable for the past genocidal actions of previous governments and their horrific impacts (historically and presently, including intergenerational trauma) on the Indigenous communities of Canada. The governments are responsible for creating opportunities to form good relations with Indigenous communities, to facilitate trust and to improve the quality of life of Indigenous Peoples.

COVID-19

During the COVID-19 pandemic, pressures on Indigenous communities have increased, causing the amplification of existing problems and the creation of more. Students were required to participate in online learning, and for the many Indigenous youth affected by the current infrastructural and housing crisis, this online learning could be occurring in unsafe living conditions. This makes it difficult for young people to access learning and to concentrate on it in their homes. Additionally, addictions, abuse, and the number of suicides has become more frequent in Indigenous communities. Lastly, the pandemic has limited consultations, engagements, and communications with Indigenous communities.

“Stay home stay safe, but what if your home isn't safe?” Footnote 26

Citizen responsibility

Every Canadian has a role in the reconciliation and un-colonization process. This shared commitment must be rooted in Indigenous experiences and spearheaded by everyday actions. The act of reconciliation will only be achieved with the participation every inhabitant of this land.

“It’s not an Indigenous only problem, we are all in the problem and the solution.”

Attainability

Youth in Canada have mixed feelings about whether reconciliation is possible. Previous unfulfilled government commitments and a lack of change and action has led to frustration and distrust. In order for youth to believe that reconciliation is possible, the governments must continuously take action to improve the quality of life of Indigenous Peoples. Youth want to see Canada develop an action plan that is measurable and relevant in order to hold our systems and institutions accountable. Indigenous Peoples should be engaged when determining this measurability and relevance.

“I believe there is still a very long ways to go and it is important that all Canadians remember that reconciliation will never be “over” and that it is a lifelong journey and learning process.”

Indigenization

Youth want the governments to acknowledge the fact that Canada was built on colonization and continues to thrive off of it today. The governments sustain and perpetuate some of the most pernicious effects of colonization. We will not be able to move forward and progress as a society until we understand the truth about what really happened when settlers arrived, and who was here before their encounter. The governments must take responsibility and act in a way that deconstructs colonization. Land is an imperative part of Indigenous sovereignty and it plays an enormous role in their way of life, beliefs, and vitality. The governments should put the power of land stewardship back in their hands. Until the land is returned to Indigenous Peoples, colonization continues. Listening to Indigenous Peoples and being accountable to their truths is foundational. We must Indigenize our country by integrating Indigenous practices into our society. The mistrust, lack of action, and the governments’ ongoing use of blanket terms hinders the youth’s optimism towards reconciliation.

“Would like to see the government acknowledging that Canada is built on colonization to actually recognize the truth.”

Healthcare

Across every parameter, Indigenous Peoples have poorer health outcomes and higher rates of morbidity and mortality than any other identifiable group in Canada. Reports of poor treatment by healthcare staff demonstrate the systematic racism towards Indigenous Peoples that is embedded into the Canadian healthcare system. The present infrastructure is not adequate to meet the current needs of Indigenous communities. Every Indigenous nation must be included in government supports. The lack of access to mental and physical health support is detrimental. Additionally, too many Indigenous communities do not even have access to clean water. This leads to a magnitude of individual and community-wide health issues. When interacting with the health care system, such as during hospital visits, biases, racism and discrimination are prevalent, which results in poorer health care services and negative health outcomes.

“There is an urgent need for counsellors for Indigenous youths, highly understaffed.”

Education

Education and awareness are the foundations of reconciliation. Indigenous Peoples in most northern and remote communities continue to face a major gap in education and training. Indigenous People in these regions experience a lack of choice in K-12 and degree granting institutions. In turn, this lack of available education forces Indigenous People and especially, Indigenous youth to relocate to areas with little to no familiar supports.

Along with addressing gaps and barriers to Indigenous education, every single inhabitant of Canada needs to learn about the true history of Indigenous Peoples and what happened when this land was encountered, such as land theft, residential schools, murder, the Sixties Scoop, food sovereignty, and the current living conditions in Indigenous communities. A mandatory Indigenous history curriculum within all the education systems would substantially facilitate the progress of reconciliation.

"I know a lot of people tell me they heard nothing in school, I’m sad but not surprised to hear that.”

Language preservation and vitality

Indigenous languages represent an enormous part of Indigenous cultures and need to be protected, taught, and celebrated. The cultural assimilation that has led to the loss of these languages has caused a catastrophic deficit in knowledge, tradition, and connections to ancestry, which together catalyzed and facilitated the horrific consequences of the colonization of this land. Decolonization must include the rematriation of languages in order to begin to address the damage caused by residential schools and the cultural decimation that Indigenous Peoples faced.

“It should be free to learn Indigenous languages as it was taken away from Indigenous Peoples.”

If youth are interested in exploring government programs related to Truth and Reconciliation, below are some examples:

- The Canadian Roots Exchange pilot program seeks to bring together Indigenous and non-Indigenous youth to promote reconciliation, mutual understanding and respect. This is a direct response to Call to Action (CTA) Number 66 of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC). Visit the Canadian Roots Exchange to learn more.

- The Indigenous Community Support Fund provides Indigenous leadership with funds to respond to COVID-19 in their communities. Visit Indigenous Services Canada to learn more.

Truth and reconciliation recommendations

Governments must...

- COVID-19

- Offer substantially more mental health support to Indigenous communities.

- Including therapists, social workers, and school counsellors.

- Ensure a higher quality of life in Indigenous communities by increasing and streamlining infrastructural capacity projects for physical health resources, creating additional spaces such as walk-in clinics, addiction centers, and community supports.

- Offer substantially more mental health support to Indigenous communities.

- Citizen responsibilities

- Create opportunities for nation-wide participation in reconciliation through community-based programming and organizational/institutional training.

- Indigenization

- Return Crown land back to Indigenous Peoples.

- In the case of not being able to return land back, the Government of Canada must unconditionally support Treaty Land Entitlement claims and all other Land Surrender claims.

- Take accountability for actions past, present and future.

- Support each Indigenous nation in their right to self-governance, without exception.

- Return Crown land back to Indigenous Peoples.

- Healthcare

- Stop ignoring and strongly address the blatant mistreatment of Indigenous Peoples in healthcare.

- Institute severe consequences for neglectful and harmful attitudes and actions from healthcare workers towards Indigenous Peoples.

- When an incident occurs, there must be a full, independent, unbiased investigation.

- Work to embed mandatory Indigenous Cultural Awareness training for ALL staff and faculty within the healthcare system.

- Education

- Work to embed Indigenous history and cultural education into all curricula across the country.

- Create opportunities for all students who lack them, to experience Indigenous culture and understand the past and present, traumas and strengths.

- Provide greater investments in Indigenous schools in order to facilitate their success and prosperity.

- Encourage and support access to post-secondary education

- Supports such as childcare, transport, and mental health services must be offered.

- Language preservation and vitality

- Prioritize the teaching and protection of Indigenous languages.

- The government must fund and implement a thorough investigation of all former residential school grounds to ensure recovery of any deceased children, found in unmarked mass graves or elsewhere.

- All remains found must be identified and returned to their communities and families.

- The people responsible for the crimes of sexual, physical, emotional, spiritual, cultural abuse of Indigenous children must be charged and held accountable.

- A full and detailed report of the completed investigation must be published, sent directly to affected communities, and made available to the public.

Conclusion

In conclusion, it is clear that a report like this could never encompass all of the work that needs to be done in order to reconcile between non-Indigenous and Indigenous communities of Canada. However, these thoughts are what the youth believe to be the next steps. The Canadian governments must work towards a trusting relationship with Indigenous Peoples, they must help communities in these times of pandemic, create concrete action plans and ways to be held accountable to it. We need to address the racism in healthcare, and we must implement an education that values Indigenous ways of being and learning.

Environment and climate action

For the Environment and Climate Action priority area, I wanted to express my own thoughts on the subject, but also some of the issues brought up in the report. I feel very strongly that climate action is of the utmost importance, and that governments everywhere could be doing more to reach climate action goals. I understand now that this is a privilege. It was eye opening to discover that accessibility was a major issue for many youth, and that meeting basic needs is difficult enough. Attitudes of apathy and inaccessibility are the major themes of my piece, and yet I wanted there to be hope – hope that we can turn things around for everyone (especially Indigenous communities around the world who are disproportionately affected by the effects of climate change, while contributing the least), if we can focus our efforts – together.

Introduction

The climate crisis is one of the most important issues that our generation faces. There are different facets of the climate crisis and in turn, different facets of solutions and answers. The climate crisis is a result of years of putting profits first and people and their well-being second. In many places across colonized Canada, you can see the effects of climate change and global warming now. We need radical, meaningful action that helps everybody out of this crisis and establishes changes that will put the earth first. During the engagement sessions, youth have talked about their reflections, concerns, and ideas regarding the crisis and the response to it.

Privilege

Racial privilege and socio-economic privilege are often discussed to demonstrate the impact of systemic racism on people’s socio-economic outcomes in their communities. It takes quite a bit of privilege to be able to focus on being environmentally conscious and sustainable versus only on getting the basic necessities, no matter how unsustainable. We also cannot forget that many people simply are not able to spend their time volunteering because they cannot afford it. Climate organizations generally, and not-for-profits specifically, are led by and made for white people and are structured in a way that leaves out marginalized youth.

“It is kind of like a privilege to volunteer with environmental organizations in general because there are youth who don’t even have food on the table. You have to have your own needs met before you can start helping and unfortunately a lot of youth don’t have that right now.”

Finally, one point that was brought up more than any other during the engagement sessions was the lack of trust and support offered to youth who are involved in climate action. Youth describe feeling laughed at, or discriminated against or plainly not taken seriously by the older people around them, teachers, parents, professors, etc. As a result, youth had less of a desire to participate in climate action.

“Some other things: youth income inequality and barriers to leadership as well, since youth with lower resources don’t have as much time or won’t be aware of as much opportunities to get involved [in climate action] since they have a lot more responsibilities.”

Location

The impacts of climate change vary based on an individual's location; in addition, location impacts an individual's ability to participate in climate action. Many respondents indicated feeling some isolation, especially in rural areas, regarding climate action. In smaller, more rural communities, there are a small number of groups who participate in climate action. In addition, recycling programs or community gardens may be more difficult to maintain or get underway. Location also has a clear impact on the amount one person might use a vehicle as opposed to public transit.

It is also clear that some communities often have poorer health outcomes as a direct result of their environment. Corporations or governmental actions often lead to serious changes in ecosystems and disrupt many communities further down the line, both in terms of future generations and through nature itself.

“Montréal dumped trash in the river, without thinking about how they affect other communities. In that case, it went to Quebec and other cities.”

It should also be noted that Indigenous communities often have the worst health outcomes in the country - often due to polluted water ways, change in natural habitats and general lack of support and infrastructure. Pipelines and corporations use Indigenous land as dumping grounds that disproportionately affect the health of Indigenous Peoples. Land Defenders like in 1492 Land Back Lane have had to protect their land from pipelines like the Tsleil-Waututh nations against Trans Mountain Pipeline Expansion or protect their treaty rights as is the situation with Mi’kmaw fishermen in Mi'kma'ki. Not only for the sake of the environment, but for the sake of preservation of tradition and sacred land.

Education

Education is, of course, a necessity when discussing environment and climate action. A main reason for this is the result of new information as well as misinformation coming out on the topic all the time.

Although some teachers or schools cover climate change, it is often old information that does not accurately portray the urgency and the different facets of the crisis, and it is often taught in a rushed manner. This means that youths are often left to their own devices when gaining access to new and more up to date information on the topic. As a result, youth turn to the internet and social media, but we must also note that many young people do not have access to internet at home. This, in turn, leads to increased inequality and divide with who can participate in the climate change discussion. Despite its benefits, social media can also lead to misinformation and over-simplification.

Education on this topic is also important once people are no longer in school. There is a need for more young adult programming, outside educational institutions, on the subject as well as community building. Some respondents mentioned more community gardens popping up since COVID-19, which is wonderful to see! There is definitely a need to make these types of programs more accessible and possibilities for funding for communities that want to offer educational activities on environment and climate action to create better and more sustainable communities.

“Littering is terrible and Newfoundland just got a recycling system. The litter goes to the ocean. People don't know how to manage their waste because of the aging population so nobody grew up recycling so people don't know how to do it.”

Sustainability

Sustainability refers to the idea of supporting our needs today while preserving the future’s ability to provide for their needs. According to the Climate Action TrackerFootnote 27, Canada is not on track to reach the Paris Agreement goals, meaning net zero carbon emissions by 2050 or keeping the temperature 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels. There is a rising push from scientists and youth advocates that the Paris Agreement goals are not ambitious enough, we actually need to be net zero by 2030.

Resources are central to the idea of sustainability. Canada has been reliant on one resource that is dooming us: oil and gas. Instead of continually investing in finite, carbon-filled resources, we should invest in cleaner sources of energy to which we have access. Let us use our resources to their fullest abilities and use them wisely. It should also be noted that other industries, not mentioned above also have far-reaching impacts on the environment that cannot be properly addressed in this document due to their complexity, such as deforestation, aquaculture and unsustainable agricultural practices.

“Socio-economic status plays a part. Being sustainable can be expensive, not accessible to everyone.”

When we talk about sustainability, we need to make good government choices for industry and people. The root cause of the climate crisis has been greed, corporations and lack of government regulations, not individual actions. The climate crisis can only be solved with an overhaul of the system, not individual actions.

Government

The Canadian government and its policies play an important part in climate action. The government has the responsibility and the ability to impose regulations on corporations and industries. The government must disclose its relationships, and collaborations, with corporations, and must enforce rules for themselves and other industries to be transparent about their carbon footprints and dealings.

The government also promised to respect Indigenous sovereignty, a key part of taking care of the land and fixing the broken system that has perpetuated climate change. The continuous push for pipelines comes at the expense of Indigenous communities, their safety and their sovereignty.

The politicization of the climate crisis has discouraged politicians from pushing for climate action. From a youth’s perspective, many adults around them do not view the environment as a priority and see it as an obstacle to a flourishing economy. Conversations about the climate with youth have been used as tools to increase candidate popularity within youth demographics.

“It can be really disheartening to be sharing your opinion and putting all this labour into ideas for improving the system… and then not really seeing it go anywhere.”

Youth are an important part of our landscape and we must treat them as the key stakeholder and rights-holders that they are.

“If youth are going to give up their time and their energy to give their opinion, they need to be shown that it’s not just going into the void… Take the ideas into account and actually do things with them.”

COVID-19

Pandemics, like COVID-19, will only become more common as the climate continues to warm. COVID-19 has been a sharp reminder about how the world will be impacted, socially and economically.

“[COVID-19 was] a big pause brought to us by nature that the world needed to take a breath of fresh air, for things to calm down and nature to truly thrive.”

Lockdown allowed us to spend more time at home and less time on the road, resulting in a lowering of carbon emissions for a period of time. On the other hand, more single-use plastics from masks and grocery store bags are being used which has increased pollution.

For years, governments have told us that we cannot move away from fossil fuels because our economy just does not allow it, but we were able to see a spike in support of local businesses and monetary support from the government. The pandemic has also shown us that a shift is possible and changing our way of life and economies are adaptable: if we can adapt for COVID-19, we can adapt for climate change. COVID-19 exacerbated the problems in our system, ones that have and still are contributing to the climate crisis. It is important to note that COVID-19 is an international issue, similarly to climate change, there needs to be leadership at all levels to have meaningful change.

If youth are interested in exploring government programs related to Environment and Climate Change, below are some examples:

- The Science and Technology Internship Program (STIP) and Science Horizons Youth Internship Program provide incentives to employers to hire natural sciences and engineering graduates to gain experience. Visit Green Jobs in Natural Resources Canada to learn more.

- Budget 2021 proposes to provide $17.6 billion towards a green recovery to create jobs, build a clean economy, and fight and protect against climate change. Visit Government of Canada Budget 2021 to learn more.

- The EcoAction Community Funding Program provides financial support to non-profit and non-government organizations for local action-based projects that produce positive effects on the environment. Visit the Government of Canada EcoAction Community Funding Program to learn more.

Environment and climate action recommendations

Governments must...

- Implement just transition principles into its policies.

- These policies will transition our economy and labour away from fossil fuels and into the green sector, while uplifting our most vulnerable.

- Re-train and re-tool workers of climate-catastrophic industries like oil and gas and fossil fuel industries into green jobs.

- COVID-19 gives us the opportunity to restart our economy and help it recover, through a Just Recovery with the basis of a Just TransitionFootnote 28.

- Invest in green technology and prototypes that are developing alternate solutions to our increased carbon footprints.

- Work with community and family farmers to develop environmentally-sustainable farming.

- Just and Green recovery that places, at its centre, marginalized people who have been negatively impacted by the system and building a system with safety nets and green basis.

- Create accessible grants for community projects geared towards environmental education- such as community gardens, solar farms, composting initiatives and more.

- Community organizing should be supported, since that is where change is most impactful.

- Offer increased grants for community projects.

- Subsidized projects to lower the cost of long-term green initiatives (e.g.,: community solar farms) and community education initiatives.

- Promote Indigenous sovereignty.

- Treating Indigenous nations as nations and supporting them to practice their traditions and cultures is essential to the betterment of the environment and our system.

- Stop pipelines, especially ones that go through Indigenous territories.

- Support Indigenous groups and communities by enabling the leadership opportunities required to do what they think is necessary.

- Give Crown Land back to Indigenous groups.

- Work with NGOs and other environmental organization to make participation accessible.

- Governments must support existing youth organizations and spaces, instead of creating their own.

- Give honoraria, and reimbursement for the time and effort of people who help guide policy and change.

- Encourage participation opportunities in any capacity, especially outside of school to allow more youth to participate.

- Marginalized people must be provided safe and inclusive spaces so that they may provide impactful change for their communities.

Conclusion

The climate crisis has manifested itself in all areas of our world and continues to impact our lives and livelihoods, especially to the younger generations. We must listen to scientists, and Indigenous elders. We must follow their knowledge, and their solutions. The government needs to follow up on its promises and hold itself accountable. It has become clear that youth do not just want mediocre action; they would like ambitious climate action where youth and marginalized groups are at the center of the solution. Climate change is a crisis, and we must treat it as such, using all of our resources and abilities.

Health and wellness

This year has been hard on everyone. It has been a constant struggle: stumbling, crashing, submerged and washed away under pilling concerns and a sea of worries. In this piece, I wanted to portray this burden. Whether it is due to the pandemic or another circumstance, taking care of ourselves is important. The wellness priority area spoke to me because our mental health is a major part of our well-being and it is imperative to give it the attention that it needs. I decided to illustrate hands around the subject to depict our loved ones as well as our own strength as we support each other and heal. The flowers growing throughout the piece portray this healing. The chrysanthemums symbolize the loyalty and devoted love we find in our support system; the lotuses depict a journey through darkness and pain, leading towards self-regeneration, rebirth, and enlightenment. We are constantly losing and finding ourselves. I hope this piece speaks to the viewer, allowing them to reflect on their own journey and interpret this in their own way.

Introduction

The health and wellness data demonstrate the unique ways young people in Canada experience the healthcare system. Youth face many barriers and inequalities due to their identities, inaccessible and costly healthcare, a lack of strong support systems particularly in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, insufficient education on mental health, physical well-being and an overall lack of extensive and culturally responsive resources.

Access to healthcare

Youth across the board struggle to access healthcare. Youth from low socioeconomic households face difficulties taking time off work to attend appointments.

Additionally, transportation is a serious concern for youth in rural or reserve communities, as it is often inaccessible or too expensive to commute for healthcare and mental health needs.

“Cost is a big one as well. We like to think that our health care is largely free. Going to a doctor has got out of pocket costs for the majority of us, it’s missed work, missed school, transportation.”

In terms of technology, there are challenges around accessing virtual healthcare particularly during COVID-19. More online and tele-health format services are needed to resolve geographical location barriers for many youths. In order to do so, the digital divide must be addressed to ensure access to affordable technology and internet connection in all communities.

“To me a healthy lifestyle/community means you have supports that match your needs and culture (not just western supports). It’s a community where people support each other and has access to the resources to meet their needs and have time/ funds for recreation.”

Equity and social determinants

There are a variety of factors that youth feel contribute to healthcare inequities including: marginalized identities, ableism/racism/classism/sexism, geographical location, lack of culturally responsive resources, inadequate nutrition and wellness education, food insecurity, etc.

“Social classes should be considered when collecting data because it can affect one’s access to healthcare.”

Visible minority youth, Indigenous youth, those from rural and remote communities, linguistic minority youth, youth with disabilities and LGBTQ2 youth do not have proper access to healthcare. Many could not access a physician due to geographical location, and others encountered biases in the healthcare system. Additionally, few services are offered in French outside of Québec, which is detrimental to the many francophone youth in official-language minority communities in Canada. Other factors contributing to inequities are food and economic insecurity, a lack of resources for unhoused youth, and a lack of mental health infrastructure in rural communities.

“Transportation, housing, food security… doctor tells you, you need to get healthy but low income have less access to healthy grocery stores. Easier access to junk food.”

Physical health

Instead of weight, youth felt that nutrition, fitness, mental health and wellness are better indicators of health, so these should be the focus during check-ups. Youth believe there is a need for complete healthcare access including: vision, dental, prescriptions, and mental health services, and that a balance must be struck between work and physical and mental health. Further, youth with disabilities face many barriers within the healthcare system especially with receiving proper diagnoses and finding supportive healthcare practitioners who understand their needs.

“For Canada’s youth, supporting health means providing opportunities to things like healthy food, activities that promote exercise, other people, and a safe place to de-stress."

Nutrition is heavily influenced by location, as those in rural and reserve communities have a difficult time accessing affordable healthy foods which impacts their physical and mental health. Due to the pandemic, accessing food banks has also become a challenge although the need for these resources has increased. Within urban areas as well, accessing affordable healthy foods can be a challenge especially in areas known as “food deserts”.

Mental health

Throughout the engagement sessions, it became evident that there is a mental health crisis impacting many youth in Canada. Youth mentioned that the lack of mental health education and accessible resources has led to continued stigma around mental health. Further, social media trends are identified as a concern among youth as well, as several individuals mentioned they were dealing with body image issues as a result of the content they were exposed to online. Additionally, an important point surrounding the safety of minors and privacy was mentioned, since the school has a legal duty to inform parents if their child is in crisis:

“Getting support for mental health support is hard because the parents are always involved. The parents don’t always understand the extent to which their child is suffering, therefore, communication is hard. Youth would be more comfortable to express what they are feeling if their parents weren’t involved.”

Students mentioned teachers and staff should receive better mental health training so they can assist youth and refer them appropriately. There is especially a need for better support for youth that are affected by bullying, an issue which disproportionately impacts people of colour, LGBTQ2 youth, youth with disabilities and those from marginalized communities, including linguistic minorities. Individuals also noted that there are long wait times to speak with counselors, and financial privilege associated with accessing private mental health care.

Systemic issues such as a lack of culturally responsive services and transportation for rural youth create additional obstacles. Further, the current system has created distrust among vulnerable, marginalized, Indigenous, and LGBTQ2 youth and youth with disabilities who may not feel safe accessing care due to unequal treatment in the healthcare system. Overall, many factors have an impact on mental health such as, socioeconomic status, food insecurity, substance use, etc.

“A huge step would be to see under universal healthcare cover mental health services, especially for youth, and having counsellors of all different backgrounds so you can see your own culture reflected in the professional helping you.”

COVID-19

COVID-19 has many negative consequences on the mental and physical health of youth. Specialists are difficult to access for remote and rural youth, and quality of healthcare is decreasing and is no longer a guarantee. Online health services are limited in scope and effectiveness, and miscommunication due to connectivity issues has been raised as a concern. There has also been a sharp decline in physical activity due to gym closures and a lack of green spaces in urban areas.

In terms of mental health, isolation and a lack of support systems led to negative mental health for many youth due to loneliness, work-life imbalance and uncertainty around the pandemic and future. Further, several challenges arose with stay-at-home orders for those who are unsafe at home. This has resulted in an increase in child abuse, as well as food insecurity; since schools are closed there is limited access to school-led food programs for youth, and LGBTQ2 youth who live with unsupportive or unsafe family members are at an even greater risk as they are cut off from support systems. Speaking openly in virtual mental healthcare sessions has also been difficult, due to a lack of safe spaces for some.

“For some – financial instability, social anxiety and isolation, fear of the unknown, anxiety for those with compromised immune systems or caring for someone in ill health, lack of physical exercise, depression/loss of motivation, extreme shut-downs in group homes leading to more limited personal freedom and mobility, CERB/EI not enough to survive, just covering rent.”

If youth are interested in exploring government programs related to Health and Wellness, below are some examples:

- Kids Help Phone is a 24/7 national service offering confidential counselling, referrals and supports to young people in both English and French. Visit Kids Help Phone or call 1-800-668-6868 to learn more.

- Wellness Together Canada is a cost-free mental wellness portal. It connects Canadians to mental health professionals for confidential chat sessions or phone calls, and offers information, tools and resources. Visit Wellness Together to learn more.

Health and wellness recommendations

Governments must...

- Provide health and wellness education to youth.

- Utilize an intersectional lens to raise awareness around healthy lifestyles, provide education on nutrition/wellness and to reduce stigma around mental health through the school and healthcare system.

- Establish youth-targeted substance use prevention resources.

- Ensure cross-sector collaboration among ethnic media, service providers and health practitioners in order to address cultural stigma.

- Provide educators with mental health and substance use training, so they understand warning signs among students and assist in appropriately referring them to resources and additional help if needed.

- Educate youth on using social media in a positive way to reduce detrimental impacts on mental health, and to develop cyberbullying prevention strategies as usage of these apps has increased due to COVID-19.

- Utilize an intersectional lens to raise awareness around healthy lifestyles, provide education on nutrition/wellness and to reduce stigma around mental health through the school and healthcare system.

- Address systemic issues in equitable access to healthcare and wellness.

- Establish more culturally responsive and multilingual mental and physical health resources which reflect the populations they are serving.

- Health practitioners should receive sensitivity training in order to ensure they provide effective and high-quality care to LGBTQ2 youth, racialized and marginalized youth, at-risk youth and people with disabilities.

- Provide publicly funded, affordable and accessible healthcare access that includes: vision, dental, prescriptions, and mental health services.

- Provide affordable healthy food options, clean water and low-cost public transportation to youth in rural/remote and reserve communities so they can access health care services.

- Increase tele-health services across all communities to reduce wait times, and provide affordable high speed internet connection across all communities.

- Create laws and regulations which permit youth (at least 16+) to access mental health services without the involvement of their parents.

- Ensure that the development of national standards for access to mental health care for youth are informed by youth through an intersectional lens.

- Recognize the effect COVID-19 has had on overall health.

- Create more green spaces especially in urban areas to encourage physical activity.

- Collaborate with schools and local service providers to provide more reliable mental and physical health supports for youth due to social isolation.

- Provide supports and safe spaces for at-risk, vulnerable and marginalized youth who are unsafe at home.

Conclusion

From the engagement sessions, it is evident that youth across Canada have been facing difficulties in accessing healthcare both pre-pandemic and during. Youth from marginalized communities, youth with disabilities, LGBTQ2 youth, those from remote areas, youth with disabilities, and Indigenous and visible minority youth have been disproportionately impacted by barriers to healthcare. Overall, intersecting factors such as ableism, racism, classism, sexism, homophobia, transphobia, ageism, geographical location and more have contributed to healthcare inequities. In order to increase access to healthcare, there is a need for: more education around healthy lifestyles and in reducing mental health stigma, culturally responsive resources, the healthcare system to be analyzed from an intersectional lens to understand what barriers to access exist for vulnerable groups, so that accessible, affordable, efficient and holistic healthcare services can be provided across rural and urban communities.

Leadership and impact

The priority that I was fortunate to model through my art piece was Leadership and Impact. This topic is important to me because I try to emulate leadership in my own life and hope that I can be a positive impact for others. This art piece is unique in many ways – the dot art is used to symbolize the intangible exuding of knowledge and leadership from the person in the middle toward the people sitting cross-legged around the circle. They are of various sizes to represent those who are in different stages of their own journeys and also references the four stages of the medicine wheel. The colours change as the perception of impact translates between provider and receivers while also connecting those next to one another.

Introduction

Throughout the engagement process, youth expressed how important leadership opportunities are to them, and the value these opportunities give youth. Some of the key themes that emerged include: what leadership means to youth, how equitable and accessible leadership opportunities are, and how COVID-19 has impacted youth and their leadership opportunities. Youth also described their interactions with both the Government of Canada and the education system.

Leadership takes many forms

For youth, leadership has many forms. It is not just creating change at a large scale, it is also informal actions that make positive change. While some are involved in politics, public speaking and community initiatives, other leaders solve problems, encourage peers, check in and take care of others, as well as protect their communities.

“Rural communities with less resources and higher proportion of the population being 65+, creates disenfranchised youth from a lack of opportunities for youth.”

Accessing the opportunity to make a difference

Many individuals note that not everyone has access to strong connections and networks in order to secure opportunities. Additionally, unpaid work is not accessible to low-income youth who cannot afford to volunteer, and in-turn this denies them leadership and networking opportunities. Accessibility to opportunities was also recognized as being a challenge due to, for instance, commuting and lack of public transit in rural areas, gender identity, language and cultural barriers and technology access. Further, youth emphasize that there needs to be greater investment in their futures, in areas such as employment opportunities for young people with disabilities and those with other marginalized identities. Overall, it was agreed that these gaps were widened further because of the pandemic, since support did not exist for these vulnerable individuals prior to COVID-19.

“Unpaid work puts low income youth at a disadvantage, deprives them of leadership and networking opportunities.”

Taking youth seriously and opportunities with government

Youth are concerned with authority figures’ misuse of power (specifically the police). It is important to acknowledge and recognize the harm that police in Canada have caused marginalized youth, their families and their communities. While youth feel positive relationships with police are important, the police first must be defunded and powered-weaponized before constructive conversations on reshaping the system and building positive relationships can occur. As well, youth want to be more involved across governments and have more opportunities to grow as leaders and sustain leadership opportunities. Furthermore, youth want to participate in the decisions that affect them and want those in the government and others to acknowledge and recognize their agency and autonomy. To give youth greater agency and participation, it is important that the voting age in Canada be lowered from 18 to 16.

“I live in Yellowknife and lived in Inuvik in the past and I've noticed that more than anything there's a sort of mental/emotional and geographical barrier. A lot of my friends don't feel as though their outlook is too important in terms of Canada as a whole, mainly because of where we live and how it seems as though a lot of people don't really know much about up here (and Nunavut included).”

Employment, education and credentials

Youth note that the importance of higher education in the current job market and economy makes it extremely difficult for those youth who face barriers to post-secondary education to find a meaningful path to employment or leadership opportunities in their community. Youth recognize that education is an enabler, because it provides credentials and employment opportunities, but it’s equally a barrier, as not everyone has equitable access to pursue education.

“As a barrier, meaningful leadership opportunities are sometimes directed solely for youth in school without consideration of youth not in school or requires decades of experience without a chance for new leaders to come to the table.”

Impacts of COVID-19

Especially during COVID-19, youth have had a difficult time maintaining social connections and relationships with peers, leading to increased feelings of loneliness and anxiety. However, youth recognize school clubs, youth organizations and leadership opportunities as sources of inspiration, hope and quality engagement, and as places where leadership can grow and marks can be made.

“Volunteer opportunities are mostly found through the internet, and there are still many youth both on reserves and in rural communities that don’t have access to these resources.”

The COVID-19 pandemic has brought about many different challenges for youth, from what is now being known as ‘Zoom fatigue,’ to internet connectivity issues in rural or reserve communities. Interacting virtually has made it particularly difficult for youth from cultural communities, whose cultural celebrations have become a shadow of what they used to be as a result of virtual adaptations.

LGBTQ2 youth are finding it difficult to access safe virtual spaces, putting them at greater risk. Barriers have also been present in areas such as finding volunteer opportunities and managing financially due to job losses. But COVID-19 has also had its positives for youth, leading to an onslaught of creativity and creative ways of doing things, as well as giving youth the opportunity to get virtually involved with issues beyond their community, province, and even country.

If youth are interested in exploring government programs related to Leadership and Impact, below are some examples:

- The Canada Service Corps offers meaningful volunteer service opportunities for youth to have positive impacts in their communities. Visit Canada Service Corps to learn more.

- Youth Take Charge supports youth to be active and engaged citizens through youth-led projects in communities. Visit Youth Take Charge to learn more.

Leadership and impact recommendations

Governments must...

- Provide increased opportunities for youth to lead and make an impact in all communities, especially on reserves, in rural areas and urban centres.

- Governments can do this by implementing skill-building workshops, investing in Member of Parliament-led youth councils and leadership training for youth.

- Provide funding and incentives for grassroots youth led organizations.

- Increase barrier free, paid leadership opportunities that do not require any experience as many youth cannot financially afford to volunteer.

- Support schools in sharing opportunities for youth, especially on reserves/smaller communities. These opportunities need to be advertised via multiple channels.

- Create a government-managed database for youth leadership opportunities and promote its use across channels to increase awareness of the opportunities.

- The database should be run by youth, for youth and be easy to use and accessible with multiple assistive technologies.

- Ensure youth have access to the tools they need to connect with opportunities.

- Ensure all youth have financial and logistical access to technology to engage with opportunities i.e., affordable internet access and cellular devices.

- Ensure that transportation is accessible to youth on reserves/in smaller communities, or that opportunities are brought directly to youth in these communities.

- Address public transit fee inequalities in urban centres.

- Ensure youth have solid role models, mentors and opportunities to build their agency.

- People appointed to leadership positions should reflect the diverse populations they are serving.

- Work directly with institutions (prisons, group homes, hospitals and disability specific residential schools) to provide more mentorship and leadership opportunities to youth who have experienced living in these institutions.

- For youth who have experienced institutionalization, governments have a responsibility to eliminate inequalities which exist in accessing employment, education, community opportunities, mental health support services etc.

- Make defunding and de-weaponizing the police an urgent priority and then have constructive conversations with marginalized communities about the role of policing and how to reshape the system.

- Funds must be reallocated to community supports, mutual aid initiatives, neighborhood programs, providing housing, tackling youth homelessness, and implementing more harm reduction programs.

- Decrease the prison population and give incarcerated and formerly incarcerated youth not only the opportunity to be mentored, but also to be paid a living wage to mentor others at risk.

- Take greater accountability for institutions such as disability-specific residential schools, the child welfare system and prisons, including ensuring there are tools to report abuse, greater oversight and regulation as well as greater opportunities for employment, volunteering and governmental involvement for youth who live in these settings.

- Remove police in all schools to help in dismantling power hierarchies and inequalities. Rather, the approach taken should be encouraging youth in schools to support each other, to work as a collective to create safe schools, to build community in schools and aid peers in place of police.

- Provide greater opportunity for youth to transfer knowledge to decision makers via direct participation.

- Provide youth more opportunity to be involved in government, to actually be listened to, and to grow as leaders while contributing meaningfully to a cause they are passionate about.

- Invest in more youth-led programming and organizations as a way of creating increased work-integrated learning opportunities.

- Urgently prioritize lowering the voting age for youth from 18 to 16.

Conclusion

The aim of this section is to present the experiences of youth across Canada in relation to leadership and impact. The summarized data addresses what leadership means to youth, the inequalities reflected by the gaps in equitable and accessible leadership opportunities, and how COVID-19 has impacted youth and their leadership opportunities. This section also offered a set of recommendations to be instated by both the Government of Canada and provincial governments, as well as other relevant stakeholders. Overall, leadership opportunities for youth are significant, valuable and should not be undermined.

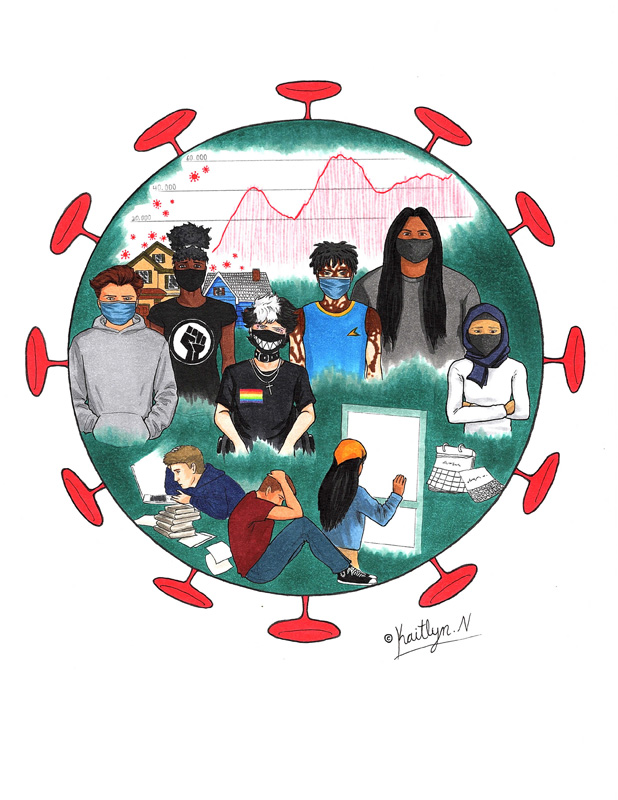

Employment

I drew a shape of a coronavirus, which is the main idea of the piece. It represents COVID-19, and how youth were affected by it. Inside the shape are young people, from many different backgrounds and identities, and the tolls that this pandemic had taken on them. I gained inspiration for this piece through how I was feeling during the pandemic, and I have not really done any art piece tying to the current state of the world, or a piece that represents a real issue before, so this priority area became the perfect opportunity.

Introduction

As barriers continue to rise, career aspirations dwindle and student debt increases, there is a pressing need to address the variety of challenges youth are facing in finding employment. While COVID-19 exacerbated many of these challenges, it also presented youth with more free time, which led to a rise in entrepreneurship. Youth are asking governments for help in growing their networks, finding entry-level opportunities, addressing their student debt and ensuring equitable opportunities for all.

Barriers to employment

Youth face many barriers that hinder their access to employment such as a lack of access to technology, professional networks and career development opportunities. Youth that come from low-income or marginalized communities are disproportionately impacted by these barriers. It is also problematic for youth who cannot find work in their official language of choice due to a lack of appropriate employment opportunities.

“If you do not have a strong network its harder to have access to certain opportunities.”

Career aspirations

Youth expressed a need for stability, work-life balance and relevant work experiences. However, given how challenging it is to find an entry-level job, youth are not able to envision their potential career options.

“If I wanted more of a casual job, I could probably get one. A career seems to be a whole different type of situation, just because I don’t actually have any college, job, or university experience.”

Youth are choosing to delay graduation or pursue further schooling due to the increased stress of not being able to find employment.

COVID-19

Due to COVID-19, job opportunities have become scarce and more competitive. As a result, youth expressed that they feel demotivated and stressed. In addition, the lack of social interaction is taking a mental toll on individuals.

“Remote work removes the social outlet that many people used to have, and has taken a toll on people who have little social interaction.”

As for positive impacts, the lack of employment opportunities led to an increase in entrepreneurship. Many youth found the motivation and capacity to start their own companies and initiatives.

“I was looking for a job with young people right ahead of COVID-19. The opportunities were all cancelled – but I was able to build my company because of it.”

Financial concerns

Youth are struggling to pay the bills. The cost of post-secondary education continues to rise and entry-level salaries are not enough for youth to pay off their student loans. This financial stress takes a toll on youth and can make it difficult for them to excel in school.

“The cost of post-secondary education compared to the wage received for those jobs is not aligned. My generation spent >$50,000 on post-secondary education with the promise of well-paying jobs. This is not the case and sets youth back in their ability to earn money, afford housing and take care of themselves financially.”

Youth are missing out on career development opportunities that are volunteer and/or unpaid.

“A lot of the job building opportunities aren’t paid, which prevents a lot of people from succeeding in their field.”

Equity

There are a disproportionate number of youth with disabilities who are unemployed. These youth are worried that a potential employer would not consider them as a viable candidate because they might be considered “expensive”.

“Will employers see me as expensive in terms of my disability?”

Youth from low-income communities aren’t able to build a strong network of professional connections which ultimately hampers their job opportunities. In addition, discrimination in the workplace leads to pay gaps and unequal opportunities.

“Incomes and salaries are not spread equally or evenly across populations with equal qualifications.”

If youth are interested in exploring government programs related to Employment, below are some examples: