Know Your Paintings – Structure, Materials and Aspects of Deterioration – Canadian Conservation Institute (CCI) Notes 10/17

Introduction

The proper care of paintings requires knowledge of both their structure and the properties of the materials they are made from. The No.10 series of CCI Notes, which includes a glossary, covers various aspects of the proper care of paintings. This Note describes the structure of paintings so that the terms and recommendations in the other Notes will be more understandable.

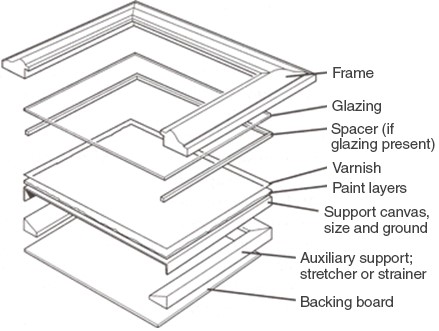

Paintings are not merely painted surfaces. Paintings are complex, three-dimensional structures composed of a variety of materials combined in an infinite number of ways (Figure 1). The unique properties of each material and the ways in which each is used all affect the behaviour of the painting as a whole. They also influence the safest way to handle, store and display the painting.

© Government of Canada, Canadian Conservation Institute. CCI 122309-0001

Figure 1. Layered structure of a traditional framed painting on fabric.

A typical painting consists of an auxiliary support (stretcher or strainer), support, size, ground, paint layers and varnish. In some cases, non-original materials used in a restoration treatment will also be present. In addition, paintings can be framed. The framing method may include glazing (glass or acrylic sheet) and a backing board secured to the frame, stretcher or strainer.

Auxiliary support

Non-rigid materials (e.g. canvas) require auxiliary (or secondary) supports to hold the flexible fabric securely in one plane. Auxiliary supports for paintings on canvas can be strainers (wooden frames with no means of expansion) or stretchers (which can be expanded at the corners and crossbars). Auxiliary supports can affect the nature of defects in a painting, e.g. paint and ground may crack along the inside edges of stretcher or strainer bars, or cracks radiating inward from the corners can develop if a stretcher is keyed-out excessively.

Paintings on thin, rigid materials may also be found stuck to or placed on an auxiliary support to provide reinforcement for handling and framing. An ivory miniature adhered to a paper or rigid board backing is one such example.

© Government of Canada, Canadian Conservation Institute. CCI 122309-0002

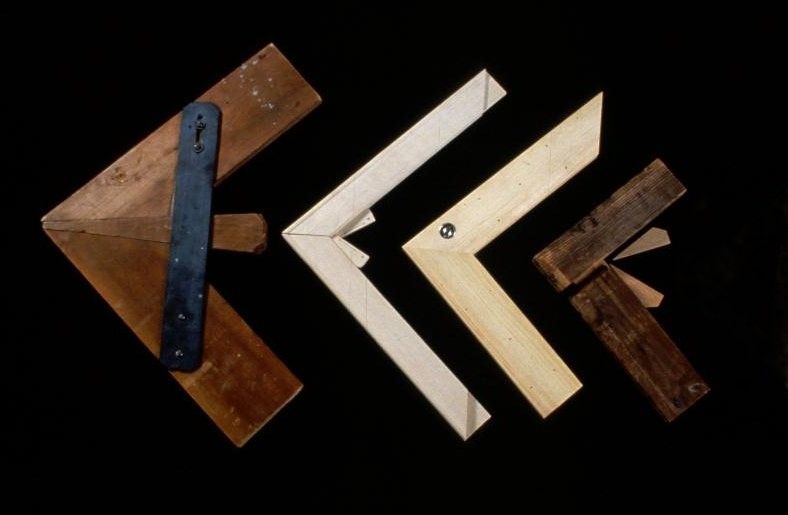

Figure 2. A stretcher can be expanded at the corners and crossbars. The mechanism of expansion varies (e.g. keys or turnbuckles).

© Government of Canada, Canadian Conservation Institute. CCI 122309-0003

Figure 3. The fixed corner joint of a strainer cannot be expanded.

Support

The support for a painting can be flexible or rigid. Support materials are usually fabric, wood, compressed wood boards, such as hardboard, or paper-based boards (referred to as paperboard, card, canvas board). Artists may also use materials such as birchbark, metal, ivory or glass. Because the support material has such a major influence on the behaviour and deterioration of the work of art, it often determines the best method for handling, storing and displaying an object; the most appropriate framing method; and the most appropriate environmental conditions, i.e. relative humidity (RH) and temperature (see CCI Notes 10/3 Storage and Display Guidelines for Paintings, 10/4 Environmental and Display Guidelines for Paintings and 10/14 Care of Paintings on Ivory, Metal and Glass). Some contemporary paintings are executed on flexible supports without an auxiliary support. These works require innovative solutions to mount them for display, handling and storage.

Wood, paper products and fabric are hygroscopic (i.e. they absorb and release water vapour), which means that they expand and contract in response to fluctuations in RH. This can cause cracking and warping of wood supports, cockling or undulations in paper-based supports, and slackening and draws (ripples) in fabric supports. Wood panels may have braces (called “cradles”) attached to the back, which may be original or applied during restoration. These cradles were intended to restrain out-of-plane movement and prevent warping. However, they may not function as intended and may have, in fact, caused damage to the wood support.

© Government of Canada, Canadian Conservation Institute. CCI 125773-0153

Figure 4. It is not unusual for out-of-plane deformation, such as overall bulging, corner draws and rippling, to develop over time as the canvas tension relaxes and slackens.

© Government of Canada, Canadian Conservation Institute. CCI 122309-0004

Figure 5. A cradle on the reverse of a wood panel painting.

Most supports suffer some form of chemical degradation with aging. This general deterioration, which causes weakening, embrittlement and discolouration of the support material, is aggravated by high light levels, high RH, high temperature, air pollutants, dirt, dust and poor-quality materials. Because overall weakening of the support increases the work of art’s susceptibility to mechanical damage, it is important to reduce or avoid damage and deterioration using procedures such as proper framing and backing boards. For example, the edges and corners of deteriorated rigid board supports are particularly vulnerable to mechanical damage and should be protected by a frame or sink mat. Similarly, the tacking margins of fabric supports are often weak and brittle (making them vulnerable to tears and splitting along the edges folded over an auxiliary support). They should be protected by a frame or a handling-travel-storage (HTS) frame (see CCI Notes 10/8 Framing a Painting, 10/10 Backing Boards for Paintings on Canvas and 10/16 Wrapping a Painting).

Supports are sometimes composed of several parts or several different materials. Wood panels, for example, may consist of two or more pieces of wood that are joined together. Collages or assemblages, seen frequently in contemporary art, may contain a variety of different materials. Such composite supports can be particularly vulnerable to handling because joints may be weak or loose, and the slightest movement could further weaken or damage the structure.

Size and ground

For oil paintings on fabric, a size is normally applied to the fabric before applying the ground. The size is usually animal glue, although synthetic sizes are currently available. The size isolates and protects the absorbent support from the acidic components of the oil medium in the ground and paint layers. The “colour field” paintings of the 1950s and 1960s executed in oil paint on canvas without size or ground preparation often show a discoloured halo around the paint on the exposed canvas, which is caused by the oil medium spreading.

A ground layer is applied to most supports. The ground ensures adhesion of the paint layers to the support and provides the desired texture and undertone for the design layer. Grounds are most often white, but may be coloured or have a coloured layer (imprimatura) applied on top. The stability of the entire painting can be at risk if the ground is not stable and coherent or does not attach well to the support.

Paint layer

The paint layers of a typical painting are composed of pigments in a binding medium such as oil, tempera or acrylic. Pigments are the colourants in the paint layer. They can influence the properties of the paint film such as drying rate, gloss and lightfastness (or stability to light; not fading). Some pigments are lightfast, i.e. they have a high degree of permanence to the effects of light. Others are fugitive (not stable in light) and can fade at even low-light levels. Each medium has its own visual attributes as well as characteristic aging or deterioration properties. Thus, each medium has its own peculiarities in terms of basic care. Common media found in collections are briefly described below.

Throughout history, artists have experimented with new and unconventional materials and methods that can hasten the deterioration of their works. This practice is not new to contemporary art. In the late 18th century, many new materials used by artists to enrich or modify their paints were unstable or had poor drying properties. During the 1950s, along with artist-quality oils, artists used industrial and trade paints, which led to darkening, cracking and cleavage (separation) between incompatible layers. Those responsible for a painting’s care must be able to recognize which defects are stable and which are unstable and require treatment.

Oil

Oil paint consists of pigments dispersed in a drying oil to which other ingredients are added to modify the drying and working properties. It is popular because of its versatility, availability and compatibility with both fabric and wood supports.

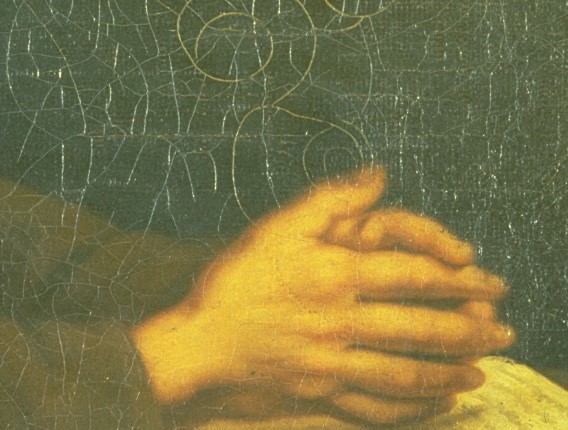

Oil paint is a relatively durable medium when used properly, but cleavage, excessive cracking, lifting and flaking can occur if the paint is used in unconventional ways that do not follow the rules of good technique or manufacturers’ instructions. Some cracking of the paint and ground layers in response to environmental fluctuations over time is inevitable and does not necessarily suggest instability.

© Government of Canada, Canadian Conservation Institute. CCI 122309-0005

Figure 6. Some cracking of paint and ground, such as seen in this detail, is inevitable and does not necessarily mean the painting is unstable.

© Government of Canada, Canadian Conservation Institute. CCI 122309-0006

Figure 7. Cracks with cupped, lifting edges can be vulnerable to flaking and paint loss.

Oil paintings are particularly vulnerable to low RH conditions, which are commonly found in buildings with central heating during Canadian winters. In low RH conditions, the size, ground and paint layers become more brittle and higher stress within the layers can develop. Below 35% RH, they are more likely to develop cracks, which in turn can lead to lifting paint and paint loss. Also, in this brittle condition, these layers are less able to withstand the mechanical stresses of handling without cracking. Fluctuations in RH, larger than 10%, can also create stresses in the layers of the painting that can eventually cause cracking. (Fluctuations occur seasonally, in day–night cycles, and near drafts, air vents, radiators, heating ducts, working fireplaces, etc.)

Some techniques, e.g. high impasto (peaks of paint), require special precautions to prevent physical contact with the fragile paint when framing, handling, displaying and storing the painting.

Synthetic media

Various synthetic resins have been developed and used for paint media. The most common synthetic paints used today are the acrylic emulsion paints, which became available in the early 1950s. Acrylic paint is also very versatile. It can be applied in thin washes as well as high impasto. Although their properties are quite different, it is sometimes difficult to visually distinguish a contemporary painting done in acrylics from one executed in oil. There is currently extensive research being undertaken to increase our understanding of the composition and properties of modern paints.

© Government of Canada, Canadian Conservation Institute. CCI 124851-0051

Figure 8. Detail of Boy and Girl Jumping Over a Fence, an acrylic painting by Norval Morrisseau, Collection of the Thunder Bay Art Gallery.

Acrylic paints are more flexible than oil paints and seem less prone to cracking; however, they have not had the test of time to determine if similar defects develop with natural aging. Acrylic paint, however, becomes more brittle and is vulnerable to cracking at moderately low temperature. It increases dramatically in stiffness at temperatures of 5–10 °C. (This dramatic change in stiffness does not occur in oil paint until a temperature range of between -5 and -10 °C.) The potential for cracking at these temperatures makes handling and transporting paintings hazardous in Canadian winter conditions. Acrylic paints also tend to attract and absorb dirt at ambient or high temperatures. As well, their surfaces can be particularly difficult to clean.

Acrylic paint lends itself to the production of large paintings, which are frequently displayed in public areas. Because these paintings often have fragile, delicate surfaces that are difficult to clean and repair, they must be protected from the physical dangers of public display (see CCI Note 10/3 Storage and Display Guidelines for Paintings, or contact a conservator for advice).

Wax

In recent years, there has been a revival of the encaustic technique. Pigments are added to a melted wax medium, applied to a rigid support, and the layers are fused with heat. The wax is often tempered (hardened) with resins or other waxes to improve durability and adhesion.

Although they are durable, encaustic paintings are vulnerable to extreme temperatures. Extreme heat, even that of direct sunlight, can cause melting, and extreme cold can cause cracking or separation from the support. Mechanical damage to the surface, such as scratches, is difficult to treat.

Tempera

This paint medium is composed of pigments dispersed in an emulsion-binding medium, which has both an oil component and a water-soluble component. The term is sometimes used incorrectly for opaque water-soluble paints such as poster colours, which do not conform to artists’ standards. To avoid confusion, a qualifying term specifies the type of emulsion medium used, e.g. “egg” tempera. The characteristics of the medium, and therefore its deterioration and care, depend on which part of the emulsion predominates, i.e. the oil or the water-soluble part. Egg tempera, which uses egg yolks as the binding medium, is usually applied on rigid supports due to its brittleness. This medium produces a delicate, smooth paint film (often characterized by fine brushstrokes and cross-hatching) that should be protected from abrasion and environmental fluctuations.

Please note: Watercolour, gouache and pastels are normally associated with paper supports, which are beyond the scope of this Note. However, they can also be used on rigid boards or in multimedia works. For this reason, they have been included here.

Watercolour

Watercolours consist of pigments ground in water-soluble gums. They are usually applied on a paper or rigid board support. Proper framing and glazing procedures are recommended because the exposed support and medium, which are porous in nature, make watercolours susceptible to damage from dirt, dust and other pollutants (see CCI Notes 11/5 Matting Works on Paper and 11/9 Framing Works of Art on Paper). Exposure to light should also be reduced. Watercolour is often executed in thin washes and even slight colour changes or fading will be apparent in colours that have poor or intermediate light stability.

Gouache

Gouache can be described as opaque watercolour. Pigments and fillers are combined with a water-soluble medium to produce a paint that is usually more thickly applied and more opaque than watercolour. Because thick applications are prone to cracking and flaking, and porous, matte surfaces hold dirt and dust and are difficult to clean, the surface of gouache paintings should be protected with appropriate frames (see CCI Notes 11/5 Matting Works on Paper, 11/9 Framing Works of Art on Paper and 10/8 Framing a Painting).

Pastel

Fabricated chalks or pastels are composed of pigment particles and a small proportion of binding medium, which supplies cohesion and hardness to the pastel stick. Pastel, characterized by a loose, powdery appearance, has a tendency to powder and flake. The pastel particles are held loosely to the support by a mechanical interaction with the surface of the support, which is usually rough or fibrous. Artists may use fixatives, a dilute resin in solution, to secure the pastel particles more firmly to the support. Fixatives, however, can discolour and change the intended chalky appearance of the pastel. For this reason, the custodian or owner of the work of art should avoid applying fixatives to it.

To avoid loss of the pastel particles, reduce vibration and shock during handling, display and storage. Suitable matting and framing procedures will also help protect the fragile surface (see CCI Notes 11/2 Storing Works on Paper, 11/3 Glazing Materials for Framing Works on Paper, 11/9 Framing Works of Art on Paper and 10/8 Framing a Painting).

Oil pastels contain pigments (or dyes) dispersed in wax and softened with a non-drying oil. Unlike oil paint, oil pastels never fully dry. Oil pastels, which can be worked into fairly thick layers, while not powdery, remain soft and very sensitive to mechanical damage, such as scraping, and to deposits of dust and dirt. Glazing in the frame can protect the vulnerable surface (see CCI Note 10/8 Framing a Painting).

Varnish

Varnish is a transparent coating of natural or synthetic resins dissolved in a volatile solvent. Traditionally, varnishes were natural resins, such as dammar or mastic. Some varnishes were tinted with pigments. Not all paintings are varnished, and some are only partially varnished. If present, varnish has both aesthetic and protective functions. It saturates the colours (revealing the depth, hue and subtle details of the design). It produces the desired surface gloss. As well, varnish protects the paint film from atmospheric pollutants, dirt, grime and minor abrasion. Unfortunately, many varnishes tend to yellow with time. This yellowing, as well as cracking or bloom (a whitish-blue haze), will change the original appearance of a painting. For this reason, and after careful consideration and testing, some original varnishes are thinned or removed by a conservation professional, who then applies a new varnish.

Evidence of previous treatment

Non-original materials from previous conservation or restoration treatments can be found on paintings. On older paintings, it is common to see a lining canvas, i.e. a second canvas adhered to the back of the original. This lining canvas provides added support to the paint, ground and weakened canvas layers. Paper strips often cover the cut edges of an original canvas. (Cutting the original tacking margins was sometimes undertaken in past lining methods. However, this practice has now been discontinued.) Poor or discoloured retouching over damaged areas may also be visible due to a poor match to the original in colour or texture. Unfortunately, older retouching often extends beyond areas of damage and covers original paint, thereby earning the term “overpaint.”

Frame

The frame, traditionally an integral part of a painting, is important in enhancing its presentation. A suitable frame and framing method can also protect the painting against mechanical damage during handling, storage and display (see CCI Notes 10/8 Framing a Painting and 11/9 Framing Works of Art on Paper).

Traditional frames are often wood mouldings covered with a thin preparation layer (gesso) and layers of paint or gilding. Ornamentation, sometimes carved but most often created by applying moulded “compo” decoration, can be present, particularly in the corners. Traditional gilding techniques can use different colours of bole (preparatory layers) and different colours of metal leaf, together with various gilding methods and finishing techniques (including burnishing or applied layers) to create many aesthetic effects. The gesso layers and ornamentation can be fragile and susceptible to lifting, flaking and loss. The thin gold leaf can be damaged by repeated or harsh dusting and cleaning methods. Even the moisture from one’s hands can mar the highly burnished surface of water gilding. Ill-advised attempts to restore frames using bronze paint can be irreversible and can destroy what is often an artwork in its own right.

Glazing (using glass or acrylic sheet in the frame) and backing boards provide additional protection against mechanical damage, dirt, dust, other pollutants, short-term environmental fluctuations, vibration and shock (see CCI Note 10/10 Backing Boards for Paintings on Canvas). New glazing materials reduce undesirable reflections (see CCI Notes 10/8 Framing a Painting and 11/3 Glazing Materials for Framing Works on Paper).

© Government of Canada, Canadian Conservation Institute. CCI 82725-0006

Figure 9. Horse and Train by Alex Colville. A non-glare glazing has been incorporated into the original frame to reduce the risk of damage to the delicate paint surface of this renowned painting. There is a spacer between the glazing and the surface of the painting. The frame, designed and painted by the artist, is an integral part of the artwork.

Some contemporary paintings are meant to be viewed without frames. Extra care must be taken during handling and storage of these paintings to prevent damage (fingerprints, abrasion, dents) to the paint surface and exposed edges. Such paintings would benefit from a temporary HTS frame that is attached to the back of the auxiliary support when the painting is not on display (see CCI Note 10/16 Wrapping a Painting).

Conclusion

All materials in a painting respond to environmental fluctuations with changes in dimension (swelling and contracting) and with changes in stiffness and strength. Even using the highest quality materials and the best techniques, defects will result if the stresses on the painting’s components become excessive. The extent and type of defects will be directly related to the artist’s technique, the type and thickness of paint, ground and size layers, the support material, and the environmental and handling conditions the painting is exposed to.

Knowledge of the materials, structure and condition of the paintings in a collection is essential when developing a program for their care. A condition survey, involving examination and condition reporting of all paintings in a collection, is an important step in identifying the types of paintings present and their basic needs in terms of storage, display and environmental conditions. The survey will identify problems, potential problems and treatment needs, as well as improvements that can be made in the preventive conservation of the collection.

Further reading

Carlyle, L. The Artist’s Assistant: Oil Painting Instruction Manuals and Handbooks in Britain 1800-1900; With Reference to Selected Eighteenth-century Sources. London, UK: Archetype Publications Ltd, 2001.

Gettens, R.J., and G. Stout. Painting Materials: A Short Encyclopedia. New York, NY: Dover Publications Inc., 1966.

Keck, C.K. A Handbook on the Care of Paintings. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Watson-Guptill, 1972.

Kirsch, A., and R.S. Levenson. Seeing Through Paintings, Physical Examination in Art Historical Studies. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2000.

by Debra Daly Hartin

Revised by Debra Daly Hartin in 2016

Originally published in 2002

Également publié en version française.

© Government of Canada, Canadian Conservation Institute, 2017

ISSN 1928-1455