Part I - Canadian Demographics Today

Systemic Racism and Discrimination in Canada

It was tempting to simply add this section on the origins of racism and discrimination in the Defence Team as an annex given the focus of this report is on how the Defence Team can correct its course rather than on how it came to have its present character. But it is unlikely that the trajectory of the Defence Team's culture will veer in the right direction unless its leaders comprehend how and why they and many DND/CAF members were programmed for the current course in the first place. Improving the future often requires understanding the past and, in this case, that means grappling with Defence Team culture from the much larger perspective of Canadian history.

And so, at the Advisory Panel's request, the Anti-Racism Secretariat summarized the history that led to the current state of racism and discrimination in the Defence Team in these short paragraphs. It was, of course, an impossible task as this limited overview of systemic inequality can hardly do justice to the libraries filled with books and stories of Canada's troubled past when it comes to its relationship with First Nations, Inuit and Métis, Black and other racialized and ethnic groups, the LGBTQ2+ communities, women, and persons with disabilities. It certainly does not cover all the forms of racism and discrimination faced by all racialized identities in Canada.Footnote 13 Nevertheless, the Advisory Panel wanted to provide a snapshot of how racism and discrimination in Canada influenced the Defence Team culture to become what it is today. The Panel believes that insight into the history of prejudice in Canada and within the Defence Team is necessary context for the remainder of this report.

Anti-Indigenous Racism

Before 1497, before the arrival of Europeans, the northern part of Turtle Island,Footnote 14 known today as Canada, was home to First Nations Peoples. The colonization of Canada began with the arrival of the first Europeans from Britain and France in the early 1600s. When Canada received its independence from Britain in 1867, it inherited treaty obligations: agreements established between First Nations Peoples as sovereign nations, and the British Crown.Footnote 15 Canada soon began to assert control over Indigenous Peoples and lands with the Indian Act of 1867, which limited self-governance of First Nations Peoples and expanded authority over Indigenous lands and services.Footnote 16

The application of the Indian Act continues to facilitate the reduction and elimination of Indigenous identities. This purpose, inherent in the Indian Act, was explicitly described by Duncan Campbell Scott, Canada’s Deputy Superintendent General of Indian Affairs, in 1920 when he remarked on the government's policy by stating: "our objective is to continue until there is not an Indian that has not been absorbed into the body politic and there is no Indian question and no Indian Department."Footnote 17

The efforts to assimilate and erase Indigenous cultures continued in the 1870s through the establishment of Residential Schools. These were religious-based schools designed to strip traditional customs, spirituality and language from Indigenous children for the sake of integrating them into Euro-Canadian culture. This form of cultural genocide lasted until 1996, when the last Residential School was closed.

Due to the institutionalization of racism in Canada, harmful conditions persist that disproportionately impact Indigenous populations. For example, institutional racism has disadvantaged Indigenous populations across education, health care, judicial and prison systems. There are glaring disparities in post-secondary attainment for Indigenous People as compared to the rest of Canadians: 8% compared to 20%, respectively.Footnote 18 Challenges to Indigenous education attainment relate to attempts to integrate Indigenous learners within "predominately Euro-Western defined and ascribed structures, academic disciplines, policies, and practices."Footnote 19 The effects of these structures within the education system are compounded by and intersect with a sense of mistrust towards Canadian education on the part of Indigenous Peoples due to "generations of grandparents and parents who were scarred by their experience"Footnote 20 in Residential Schools, as well as insufficient funding for on-reserve schools and inadequate access to essential services.Footnote 21

Substandard and lower health care outcomes, particularly for Indigenous Peoples,Footnote 22 have been linked to racism in health care institutions. Institutional racism contributes to higher infant mortality ratesFootnote 23 and lower life expectancy rates among Indigenous communities.Footnote 24 As Brenda Gunn's research suggests, "a high proportion of the Indigenous population experience individual and systemic racism when seeking health services."Footnote 25

This institutionalized racism happens both structurally and culturally. Structural racism permeates policies and practices creating profound health disparities for members of Indigenous communities.Footnote 26 In addition, cultural forms of racism relate to power inequities between care providers and Indigenous patients, and biases and stereotypes about Indigeneity held by practitioners.Footnote 27 These structural and cultural forms of racism limit Indigenous Peoples' ability to access adequate medical care.

Similarly, "more than 30% of inmates in Canadian prisons are Indigenous – even though [Indigenous Peoples] make up just 5% of the country's population."Footnote 28 These numbers can be even more pronounced when gender and region are also considered. For example, 98 percent of women in custody in Saskatchewan are Indigenous.Footnote 29 According to Senator Kim Pate, "racial and gender inequality" are the underlying factors for what is happening in the Canadian justice system. She explains that "Indigenous men have fewer opportunities, but Indigenous women have even fewer."Footnote 30 Pate argues that "part of the reason we've had to focus on the women and girls who have gone missing, been disappeared, [and] been murdered, is the very same issues that contribute to them being homeless, being on the street, and also being in prison and it's fundamentally about inequality."Footnote 31 As the National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls explained:

Colonial violence, as well as racism, sexism, homophobia, and transphobia against Indigenous women, girls, and 2SLGBTQQIA people, has become embedded in everyday life – whether this is through interpersonal forms of violence, through institutions like the health care system and the justice system, or in the laws, policies and structures of Canadian society. The result has been that many Indigenous people have grown up normalized to violence, while Canadian society shows an appalling apathy to addressing the issue.Footnote 32

Anti-Black Racism

Anti-Black racism began in Canada during the transatlantic slave trade era. The enslavement of African peoples was considered a legal instrument and was used to fuel the economic stability and growth of the colonies. In the 1760s, some laws outlined the treatment and disposition of Black people in bondage. According to the Ontario Black History Society, the 47th Article of Capitulation of Montreal ensured that African and “Panis” (Indian) slaves remained the legal property of their owners.Footnote 33 The legal recognition of Black and Panis slaves as property was recognized by the Peace Treaty of 1763 and the Quebec Act of 1774.Footnote 34

The buying and selling of enslaved Black people lasted for two centuries. During the American Civil War in the 1860s, Canada was regarded as a haven for escaped slaves on the Underground Railroad. However, the stereotypes connected with slavery and the fewer rights written into law for Black people versus their white counterparts supported a view of Black people as inferior and perpetuated their hostile and discriminatory treatment. Discriminatory attitudes towards and treatment of Black Canadians continue to this day.

For example, Black people are "dramatically overrepresented in Canada's prison system, making up 8.6 percent of the federal prison population, despite the fact they make up only 3 percent of the population."Footnote 35 And in a 2020 report commissioned by Ontario’s Ministry of Education, evidence of institutionalized anti-Black racism was reported in the Peel District School Board.Footnote 36 The report identified the suspension of Black students at higher rates than students of other ethnic backgrounds as well as a tendency to involve police in incidents involving Black students where no evidence of criminal activity was present.

Perpetuated negative stereotypes about Black people have led to the internalized racism that impacts contemporary society.Footnote 37 An example of internalized inequality is outlined in a 2015 survey showing that while "nearly 94 percent of Black young people aged 15 to 25 said they would like to complete a university degree, only 59.9 percent thought it was possible."Footnote 38 In contrast, "82 percent of other groups surveyed said they wanted to achieve a university education, and 78.8 percent believed they could."Footnote 39 This is evidence of the significant gap between hope and expectation among Black youth.

Andrea Davis, associate professor at York University's Department of Humanities, explains that Black young people "work tremendously hard and their aspirations [for education] are great. But very few people have told them they can be successful."Footnote 40 She argues that the most profound finding from her research on the impact of violence among youth in Toronto is that Black youth perceive everyday lived experiences of cultural racism as the worst form of racism. They have experienced it from "teachers who did not believe in them, who stereotyped them, who over-disciplined and over-punished them, who constructed possibilities for them that were different from the possibilities for other children."Footnote 41

Davis cautions that racism is "a kind of cycle that doesn't break. And it can be invisible, so many Canadians don't see it because they don't know how to narrate it, or it's not narrated for them."Footnote 42 Importantly she notes that "the reality is that racism is expressed not just as conscious acts of hate or violence, it's far more complex than that. It evolves out of a set of deeply rooted systems in our country. So deeply rooted that it might be easy to miss."Footnote 43

Anti-Asian Racism

Canada has a very long history of anti-Asian racism. Some of the most egregious examples include the terrible conditions that almost 20,000 Chinese workers endured while building the Canadian Pacific Railway between 1885 and 1923, and the Chinese head tax that was enacted to restrict the immigration of Chinese people afterwards.Footnote 44 Implemented through the Chinese Immigration Act (1885), the tax was the first legislation in Canadian history to limit immigration based on one's ethnic background.Footnote 45 At the time, Chinese people had to pay $50 to enter Canada, and over 38 years this increased to $500, benefiting the Canadian economy by $23 million. In 1923 the head tax was removed and replaced with the Chinese Exclusion Act, which banned all Chinese immigrants until its repeal in 1947. The Canadian Government has since apologized for issuing the head tax, acknowledging it as a racist immigration policy targeting Chinese people.Footnote 46

Large-scale discriminatory acts against Japanese Canadians were also practiced during the Second World War. Japanese Canadians lost the right to vote in federal elections because the government considered Japanese Canadians to be a threat to Canada's security. It was not until 1948 that Japanese Canadians were allowed to vote in both federal and provincial elections.

Canada's denial of entry to people from India is a further example of discriminatory practices against Asians. In 1914, Canada stopped immigration from India, detaining 376 people on the Komagata Maru ship for two months. The incident ended in a deadly encounter with police and troops, and the passengers' return to India.Footnote 47 Anti-Asian racial discrimination continued with the rise of lobbies in Canada that opposed the immigration of Chinese, Japanese, Punjabis and other South Asians.Footnote 48

The COVID-19 pandemic has only exacerbated long-standing prejudices against racialized Asian communities. Between March 2020 and February of 2021, the Chinese Canadian National Council recorded more than 1,000 incidents of anti-Asian racism.Footnote 49 Reported incidents spanned from assault to verbal threats, harassment and microaggressions.Footnote 50 Similar impacts of racism occurred during Canada’s SARS outbreak: there was a significant loss of patronage to Asian-run businesses and unfair dismissals of workers, particularly new immigrant populations from China and the Philippines.Footnote 51

There has also been an escalation of anti-Islamic racism in Canada, particularly since the World Trade Center and Pentagon attacks in the United States of America on September 11th 2001.Footnote 52 In 2017, the Islamic Cultural Centre of Quebec City was attacked: six worshippers were killed and five wounded.Footnote 53 On June 6th 2021, a London Muslim family of five was deliberately attacked in a horrific hate crime, with four members killed. There has also been a marked increase in violence and discrimination towards Muslim women in Quebec since the tabling of Bill 21, legislation banning religious symbols in segments of the province’s civil service.Footnote 54 Over that time, Justice Femme, a non-governmental organization supporting women in Quebec, received over 40 harassment and physical violence reports targeted at women who wear the hijab. These hate crimes are extremes in a long list of ethnic, gendered, and religious-based violence committed against racialized Canadians.

The Intersection of Racism with Experiential and Identity Factors

Racism intersects in complex ways with other systems of oppression that construct the differential treatment and perceived value assigned to groups based on gender, sexual orientation and ability. Racism, patriarchy, heteronormativity and white supremacy are embedded in systemic, institutionalized and structural forms of discrimination. Their manifestations range from extreme acts of hate to normalized cultural exclusion and marginalization.

LGBTQ2+ Prejudice

Prejudice against LGBTQ2+ individuals in Canada can be traced as far back as 1842 when Patrick Kelly and Samuel Moore were the first same-sex couple to be convicted of sodomy. In Canada, sodomy carried a maximum sentence of death until 1869. The men were sentenced to life imprisonment and then later released.Footnote 55

In the 1950s, sexual orientations beyond heterosexuality were regarded as security threats for defence and security organizations such as the Canadian Armed Forces and the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP).Footnote 56 In the attempt to identify gay or lesbian serving members, the RCMP used a device referred to as the “Fruit Machine” that was developed by a professor at Carleton University.Footnote 57 In 1963, the RCMP created a unit with the sole mission of finding and removing gay men from law enforcement and government, and created a map identifying residences of targeted community members. Those who identified as or were suspected of being gay or lesbian were interrogated and then fired, as homosexual acts between consenting adults were considered a crime until 1969. These operations endured by LGBTQ2+ communities were oppressive and affected thousands of lives.Footnote 58 Such exclusionary practices ended only in the early 1990s.Footnote 59

While there is increased awareness and understanding of the human rights of LGBTQ2+ individuals, including through a formal apology issued by Prime Minister Justine Trudeau on 28 November 2017, discrimination based on sexual orientation is still prevalent. In her 2015 report, former Supreme Court Justice Marie Deschamps found that the Canadian Armed Forces maintained a sexualized culture hostile to women and members of the LGBTQ2+ communities.Footnote 60

Gender Discrimination

Gender discrimination is pervasive in Canada. Women and girls in Canada face disproportionate barriers based on gender and sex that are perpetuated through violence, poverty, income disparity, and lack of access to opportunities, including those in leadership.

The poverty rate for women in Canada is consistently higher than the rate for men. Indigenous women are among the poorest women in Canada, and racialized women are also heavily economically disadvantaged, due to limited access to opportunities and income inequality resulting from processes of racialization.Footnote 61

Discriminatory policies such as the Indian Act prevented Indigenous women from benefiting from some of the same rights as men. For example, Indigenous men were able to pass on their Indian status to their children and grandchildren whereas Indigenous women were not. These discriminatory practices still impact families today.Footnote 62

A 2019 report by the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives describes the areas that require closer examination when it comes to gender equity in Canada. For instance, women’s high scores in "health and educational attainment in Canada have not translated into notable progress on the economic front or women's representation in leadership. These high scores also tend to hide fundamental disparities between different groups of women."Footnote 63 Between 2006 and 2018, Canada's gender gap in economic security "inched forward an average of 0.2% per year." At this rate of increase, it would take 164 years to close the financial gender gap between women and men in Canada.Footnote 64

Canada's gender pay gap is one of the highest in the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Canada ranks 31st out of the 36 OECD countries on gender pay inequality, falling behind all European member states and the United States. While average full-time earnings among Canadian women are higher than in many countries, Canadian women are paid 82 cents on average for every dollar that men take home. This disparity "is even larger for racialized women and Indigenous women, who make 60% and 57%, respectively, of what non-racialized men earn."Footnote 65

A common reaction to these statistics from the Defence Team is that this disparity is not reflected in DND/CAF workplaces: rank structures and departmental positions ensure that members earn the same salary regardless of their gender. However, inequities can be found when women progress more slowly because they take on significantly more childcare responsibilities. They miss out on the box-ticking requirements of a streamlined career progression: deployments, courses, exercises, training and other experiences.

Canada's gender gap score has been negatively impacted by the low share of women in public and private sector management positions. In 2018, men outnumbered women in these professions by two to one. Racialized women accounted for 6.5 percent of senior management positions, while Indigenous women accounted for 1.2 percent.Footnote 66 Similar tendencies exist within the Canadian Armed Forces, where a sharp decrease in women, Indigenous and visible minority representation occurs in higher-ranking leadership positions.Footnote 67

All people deserve to live and work in environments that are inclusive, fair and safe. Yet, gender-based violence is a daily reality for many people in Canada. More than 11 million Canadians have been physically or sexually assaulted since the age of 15. This represents 39% of women and 35% of men. There is a much higher prevalence of reported sexual assault among women than men (30% versus 8%), while men are more likely to be physically assaulted.Footnote 68 Estimates of unreported sexual assault and criminal harassment are much higher, with men less likely to report incidences of sexual assault. Women’s heightened risk of gender-based violence involves not only sexual assault, but also cyber-violence and exploitation. Sexual assault and harassment are persistently misunderstood and under-reported despite increasing awareness and education.Footnote 69

In Canada, the threat of violence is particularly acute for Indigenous women, women with disabilities, and LGBTQ2+ people. Research from the National Inquiry into Murdered and Missing Indigenous Women and Girls found that Indigenous women and girls were 12 times more likely to be murdered or missing than any other women in Canada, and 16 times more likely than Caucasian women. Statistics Canada notes that the rate of sexual assault is higher for sexual minorities, younger people and people living in urban centres.Footnote 70 In these ways, the patterns noted in Canadian reports of sexual and gender-based violence show intersections with race, gender, sex, sexuality, age, ability, and region.

Sexual violence, including rape, is a reality in the Defence Team and continues to create harm for serving members, employees and their families. The Advisory Panel was disturbed to hear about a trend where women who are abused by CAF husbands who have been diagnosed with post-traumatic stress injuries are being told that, because their husbands served their country, their violence should be met with compassion. These women are pressured into "doing their duty to support" an injured partner. They are encouraged to "take one for the team."

In April 2021, the MND appointed former Supreme Court Justice Louise Arbour to review policies regarding sexual misconduct. Former Supreme Court Justice Morris J. Fish was also mandated to review the National Defence Act and recommend changes to better protect victims and survivors. Finally, the establishment of the Chief, Professional Conduct and Culture organization is intended to address the systemic culture of gender discrimination and violence among employees and serving members.

Persons with Disabilities and Discrimination

As is noted in greater detail in Part III, section 7, the Canadian Armed Forces' universality of service principle limits the participation of persons with disabilities by requiring all service members to be able to perform general military duties. However, persons with disabilities continue to face unjustifiable discrimination and prejudice within the Defence Team, just as they do in wider Canadian society.

Grassroots focus on the human rights of persons with disabilities in Canada began after the First World War. At that time the focus was to protest institutions developed to segregate those identified with cognitive illnesses as well as intellectual and physical disabilities. Activists fought for the fundamental human rights of persons with disabilities and sought to undermine narratives that painted persons with disabilities as lesser and highly dependent on others.Footnote 71

The Canadian Government began to pay particular attention to persons with disabilities after the Second World War. The disparities between disabled veterans and civilians with disabilities became apparent. The array of social supports and occupational services for veterans, as well as their political clout, ignited broader interest in developing opportunities for persons with disabilities who were non-veterans. A movement began that saw the promotion and expansion of services to all who needed them regardless of the source of their disability.Footnote 72

The Canadian Human Rights Act, passed by the federal government in 1977, was the first law to give specific rights to persons with disabilities. It states that all Canadians have equal rights regardless of sex, race, nationality and disability. Later, other acts like the Blind Persons Rights’ Act and Employment Equity Act were also put in place. In 1985, the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms declared physical or mental disability a prohibited reason for discrimination.

In 2007, Canada was a signatory to the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. The convention seeks to create a more inclusive society by requiring member nations to meet the following obligations: adopt legislation to promote the human rights of persons with disabilities, develop accessible goods, services and technology, and adopt legislative or other measures to abolish discrimination. The passing of these laws achieved significant gains in advancing human rights and equity for Canadian persons with disabilities.Footnote 73

Yet, persons with disabilities continue to face systemic, institutionalized, structural and cultural barriers. At the early stages of Canada's disabilities rights movement in the 1970s, persons with disabilities were critically examining barriers in physical access throughout their communities; the shortage of accessible transportation; inadequate accessible and affordable housing; a shortage of personal care programs; exclusion from meaningful decision-making; and acute unemployment.Footnote 74

At present, John Rae has noted that "it is astonishing how many barriers still exist to the full participation of persons with disabilities."Footnote 75 He argues that, while there has been slight improvement, "the cutbacks to essential services keep coming."Footnote 76

Injustices faced by Canadians with disabilities extend to assault and sexual violence. A 2014 Statistics Canada report found that "persons with a disability were overrepresented as victims of violent crime."Footnote 77 Close to 40 percent of "incidents of self-reported violent crime—that is, sexual assault, robbery, or physical assault—involved a victim with a disability."Footnote 78 The report noted that experiences of violent crimes also intersect with sex and gender: in "45% of all violent incidents involving a female victim, the victim had a disability. When looking at male victims of violence, one-third of incidents involved a male with a disability."Footnote 79

White Supremacy

The term “white supremacy” is often misunderstood. For this report, the following definition is used: white supremacy “is the idea (ideology) that white people and the ideas, thoughts, beliefs and actions of white people are superior to People of Colour and their ideas, thoughts, beliefs, and actions. White supremacy expresses itself interpersonally as well as structurally (through our governments, education systems, food systems, etc.).”Footnote 80 A white supremacist is “a person who believes that the white race is inherently superior to other races and white people should have control over people of different races.”Footnote 81

In Canada, white supremacy was first woven into the fabric of Canadian society with the colonization of Indigenous lands by European settlers (see above). Since then, government and institutional policies have exercised discriminatory control over the citizenship rights of Indigenous People, racialized people, religious minorities and LGBTQ2+ communities.Footnote 82

According to Dr. Barbara Perry, one of Canada’s top hate crime researchers, Canada has close to 300 white supremacist entities, anti-immigrant groups, and holocaust deniers that have operated for decades.Footnote 83 White supremacy groups include Stormfront, Three Percenters, Soldiers of Odin, The Base, La Meute and Storm Alliance. White supremacy takes the form of anti-Black hate, holocaust denial, anti-Muslim violence, and gender- and race-based xenophobia. According to Tema Okun and Keith Jones, white supremacy culture is the systemic, institutionalized centering of whitenessFootnote 84.

Systemic Racism and Discrimination in the Defence Team

As described earlier, the “system of systems” in Canada today was established almost exclusively by European settlersbeginning in the 18th century. That system has evolved in many ways but is primarily controlled by and for the benefit of the political and social group that initially constructed it. It is only in the last century that women and non-European immigrant groups have gradually developed some political and social power. However, the pace of that progress has been slow, and those groups still face resistance, discrimination, social stereotypes and double standards.Footnote 85

With very few exceptions, the CAF (and its predecessors) recruited initially from the group identifiable as young, white, male, heterosexual, Christian and of European origin or descent. That representation has evolved, but one could argue that only during the First and Second World Wars did the Canadian Armed Forces truly “reflect” Canada. At the same time, National Defence has a rich history of diverse members serving prior to the First World War, including women, Indigenous, Black, and other racialized people and LGBTQ2+ members.

Archives show that during the First World War, over 12,000 Indigenous Canadians volunteered to serve, and approximately 1,250 Black Canadians and 200 Japanese Canadians served as part of the Canadian Expeditionary Force; of those, 130 Japanese Canadians fought at Vimy Ridge. According to records of Canadians’ service during the Second World War, 600 Chinese Canadians volunteered,Footnote 86 as well as 17,000 Jewish Canadians.Footnote 87 It is impossible to know the number of brave LGBTQ2+ Canadian Armed Forces members who had to hide their identity to serve.

The historical account illustrates a pattern of racist and discriminatory practices in Canada that have become institutionalized in laws, regulations, policies and procedures, shaping Canadians’ world view of Indigenous, Black, racialized, LGBTQ2+ people, women and persons with disabilities. National Defence, which is approximately 127,800 people strong, is a microcosm of Canadian society. As such, inequities and discriminatory practices seen in wider Canadian society are also present within the Defence Team.

Representation

For a national organization to be legitimate and effective it must reflect the national population. The composition of National Defence does not reflect the society it is mandated to serve. It is difficult to engender the credibility and trust required for DND/CAF to deliver adequate safety and security for Canadians under this condition. As David Bercuson has noted, “if an army does not reflect the values and composition of the larger society that nurtures it, it invariably loses the support and allegiance of that society.”Footnote 88

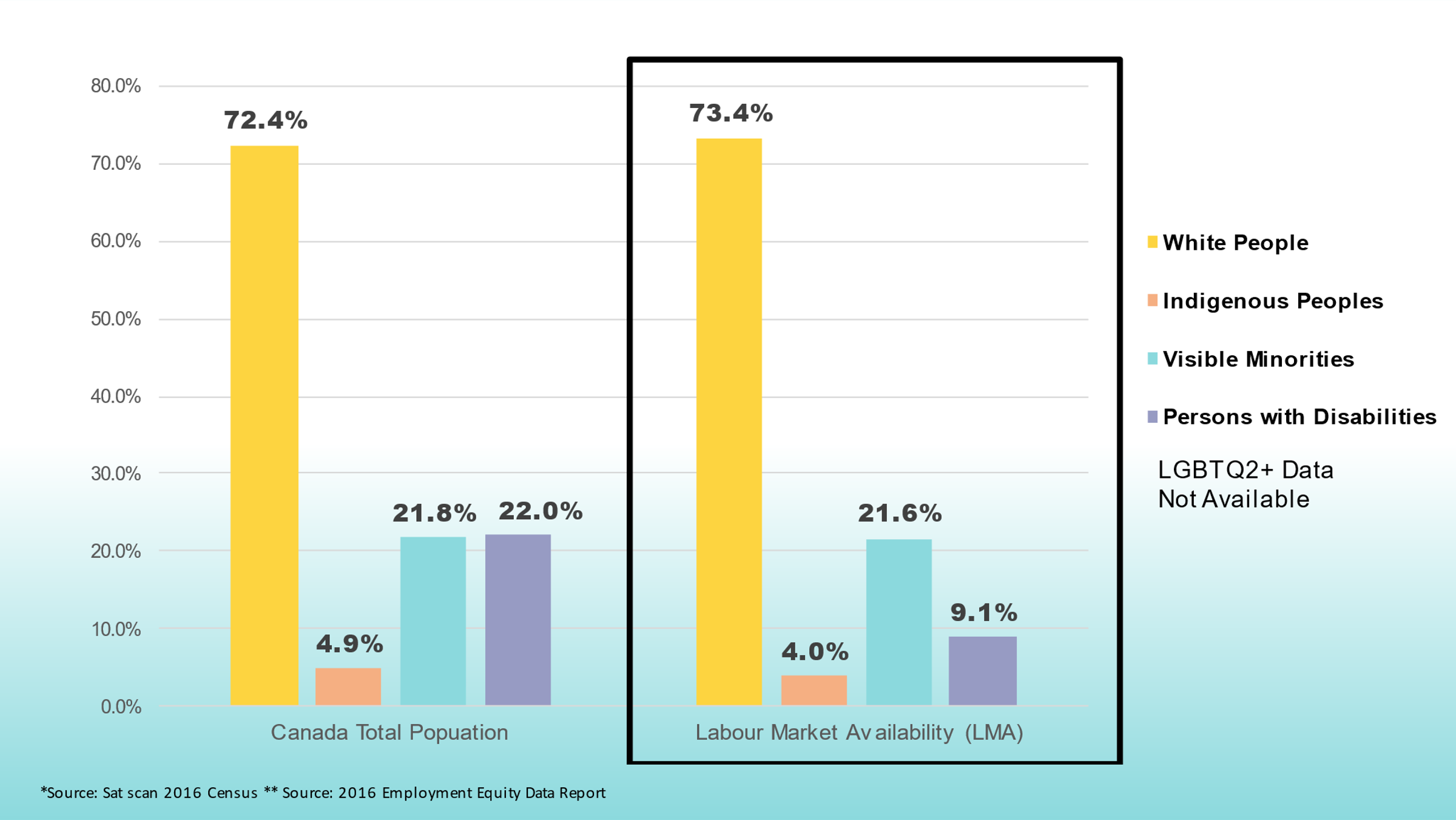

Canada's population is approximately 38 million people.Footnote 89 Figure 1 depicts Canada’s Labour Market Availability (LMA), which refers to the proportion of Canadians available to work. White men and women account for approximately 73% of Canada's LMA,Footnote 90 Indigenous Peoples comprise 4% of the labour force, while visible minorities account for 22% and persons with disabilities comprise 9% of Canada's available labour force.

Figure 1: Canada’s Total Population vs. Labour Market Availability

Long description of Figure 1

Canada Total Population

| Populations | Percentage |

|---|---|

| White People | 72.4% |

| Indigenous Peoples | 4.9% |

| Visible Minorities | 21.8% |

| Persons with Disabilities | 22 % |

Labour Market Availability (LMA)Footnote **

| Populations | Percentage |

|---|---|

| White People | 73.4% |

| Indigenous Peoples | 4.0% |

| Visible Minorities | 21.6% |

| Persons with Disabilities | 9.1% |

LGBTQ2+ Data not available

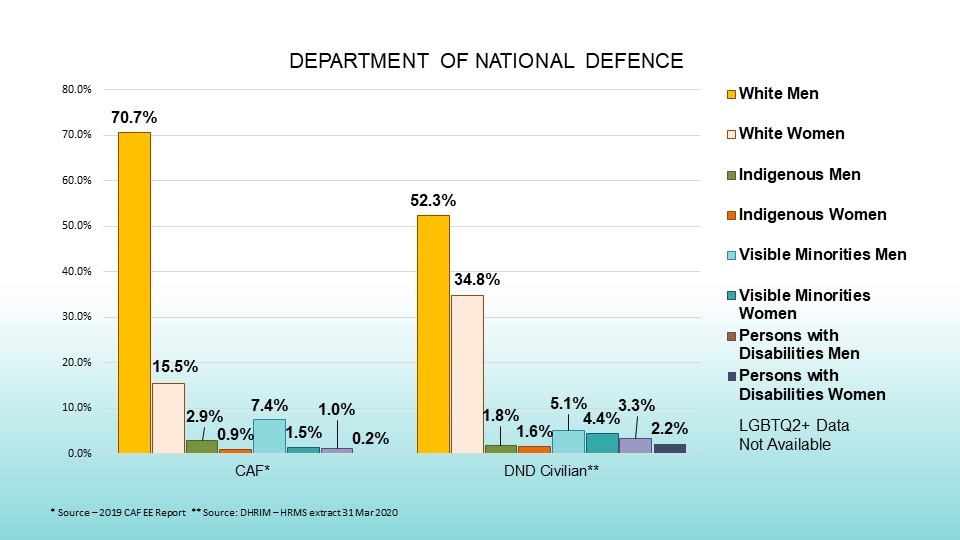

Currently, Indigenous, Black and racialized people are vastly underrepresented in both CAF and DND, and women are also notably underrepresented in both populations. White men account for approximately 39% of the available workforce but account for about 71% of the CAF population and 52% of the DND civilian population. Women account for approximately 48% of the Canadian workforce, yet only account for 18% of the CAF population and 41% of the DND civilian population.90 Indigenous, Black, and racialized people account for approximately 25% of the available workforce but only account for 13% of the CAF and DND civilian workforces combined.

Disaggregated dataFootnote 91 regarding the representation of Employment Equity (EE) groupsFootnote 92 across the entire Defence Team was not evenly available to the Advisory Panel.

Figure 2: The Demographic Breakdown of National Defence

Long description of Figure 2

CAFFootnote *

| Populations | Percentage |

|---|---|

| White Men | 70.7% |

| White Women | 15.5% |

| Indigenous Men | 2.9% |

| Indigenous Women | 0.9% |

| Visible Minorities Men | 7.4% |

| Visible Minorities Women | 1.5% |

| Persons with Disabilities Men | 1.0% |

| Persons with Disabilities Women | 0.2% |

DND CivilianFootnote **

| Populations | Percentage |

|---|---|

| White Men | 52.3% |

| White Women | 34.8% |

| Indigenous Men | 1.8% |

| Indigenous Women | 1.6% |

| Visible Minorities Men | 5.1% |

| Visible Minorities Women | 4.4% |

| Persons with Disabilities Men | 3.3% |

| Persons with Disabilities Women | 2.2% |

LGBTQ2+ Data not available

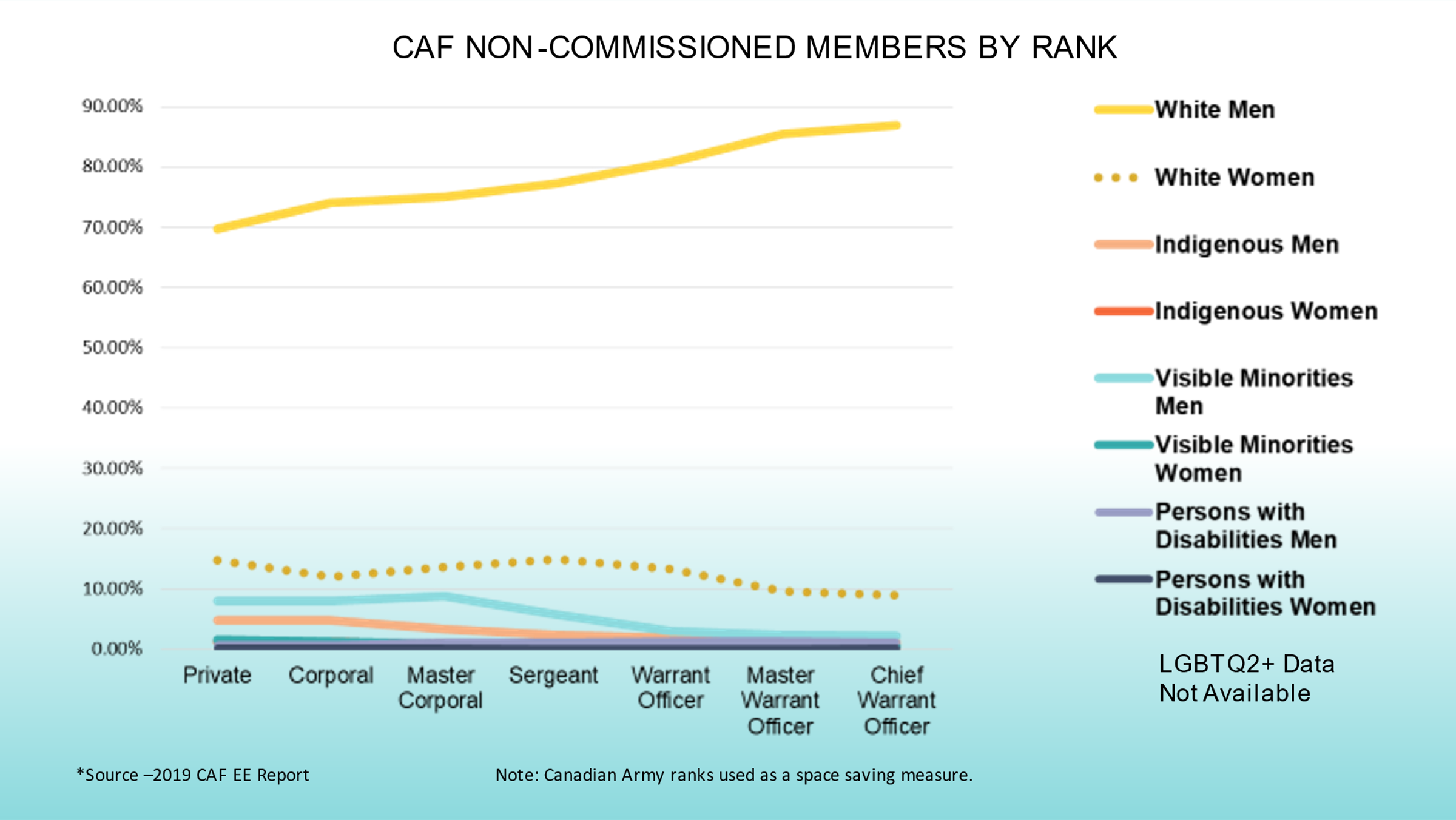

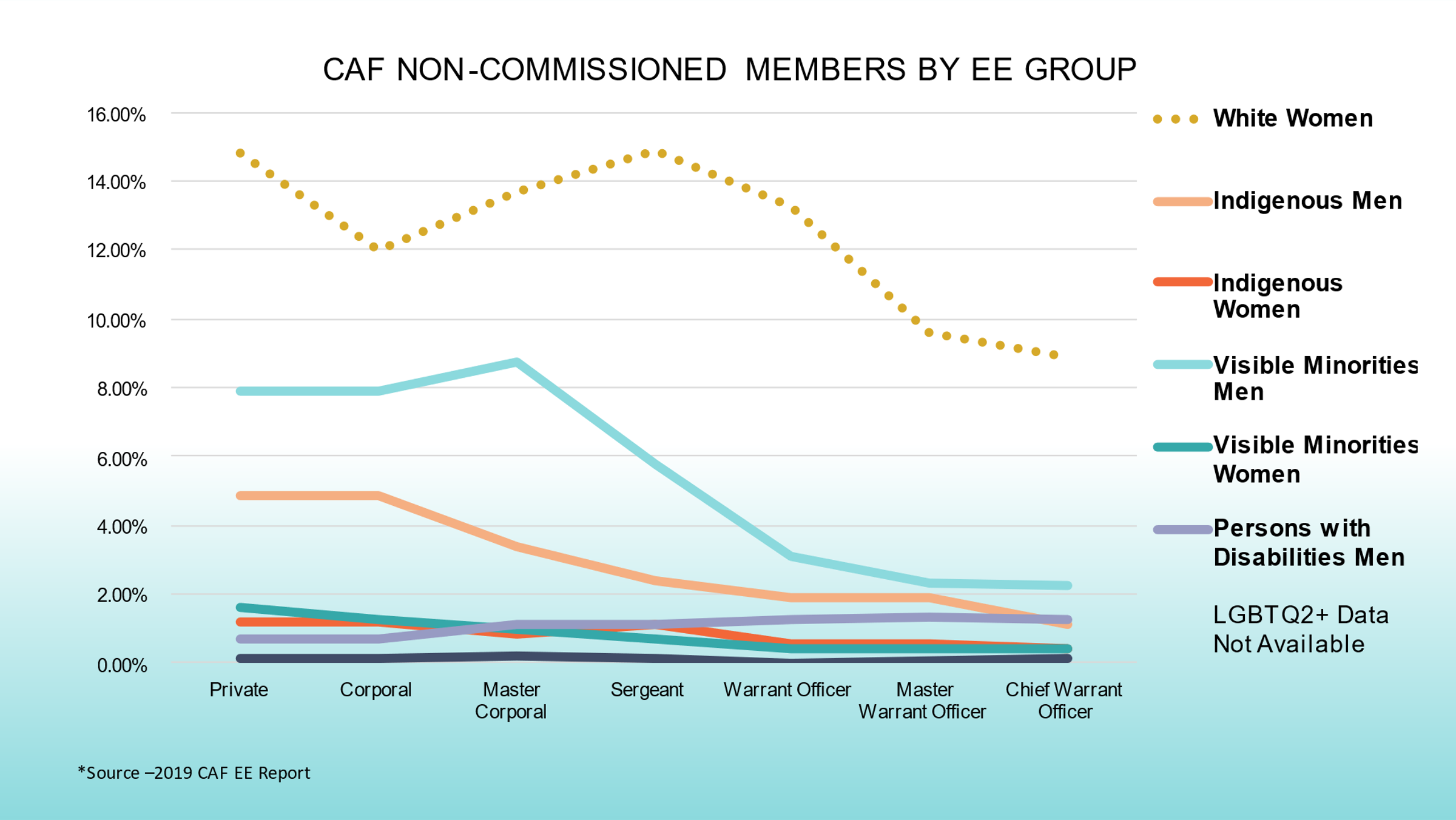

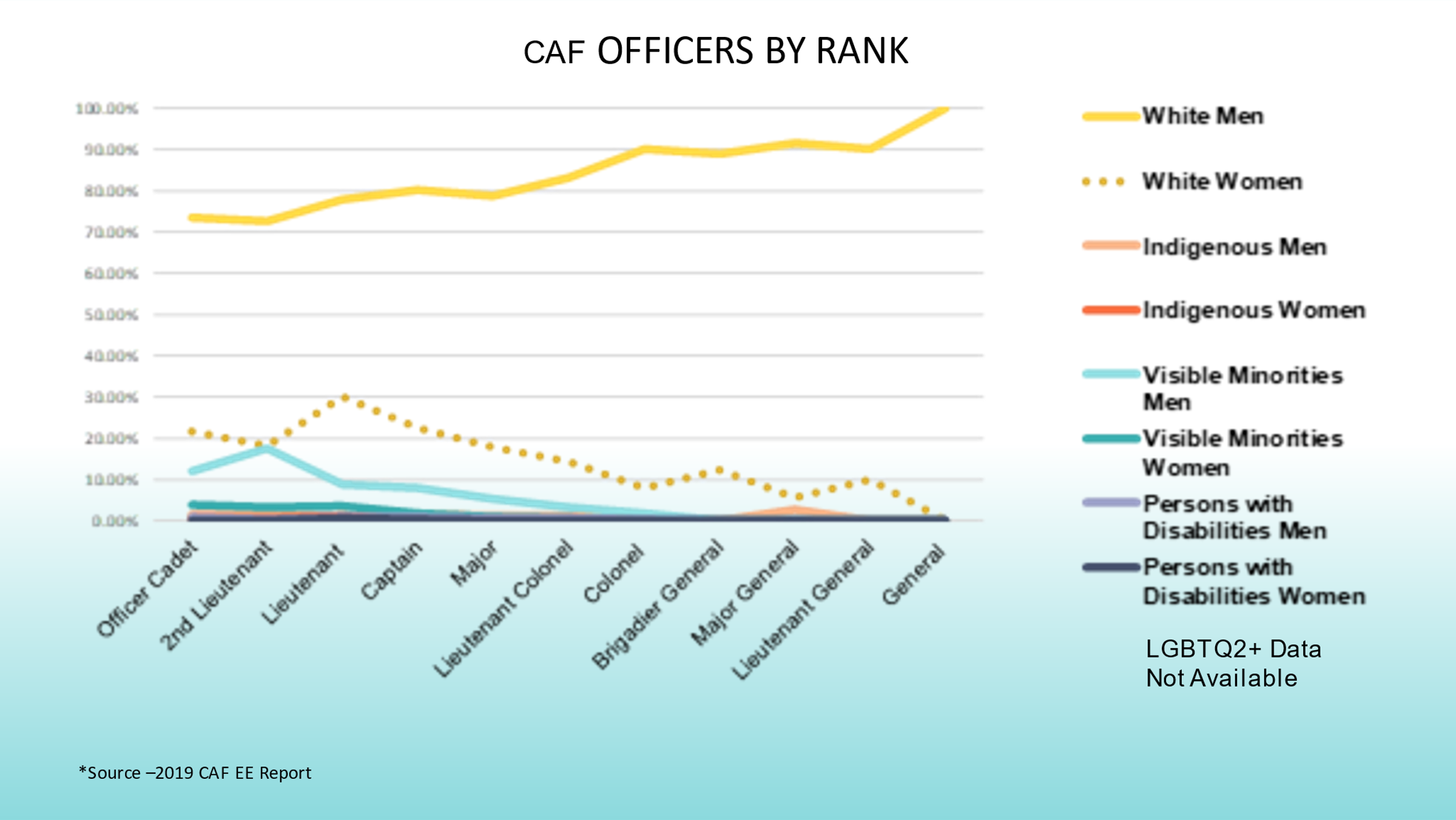

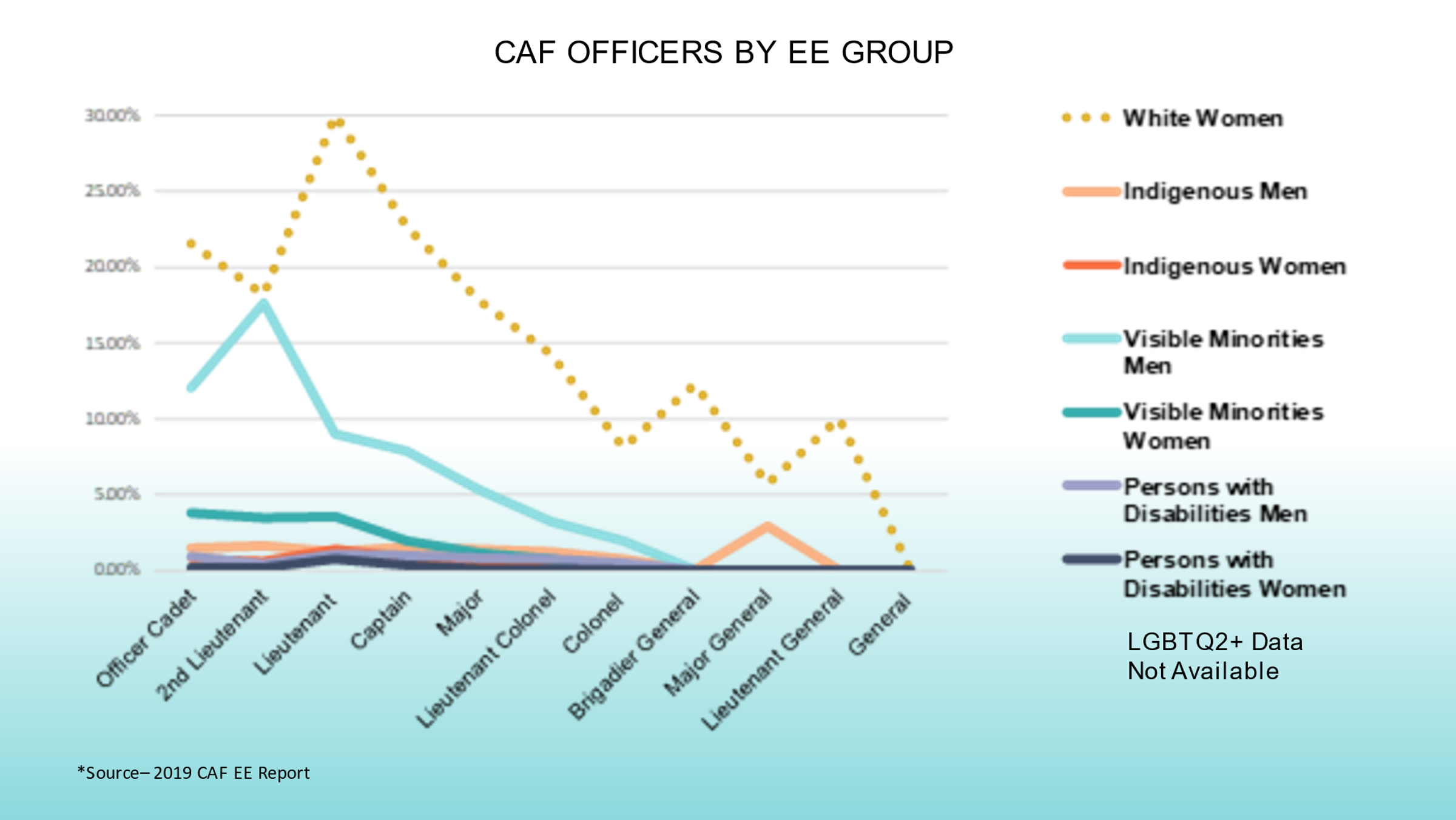

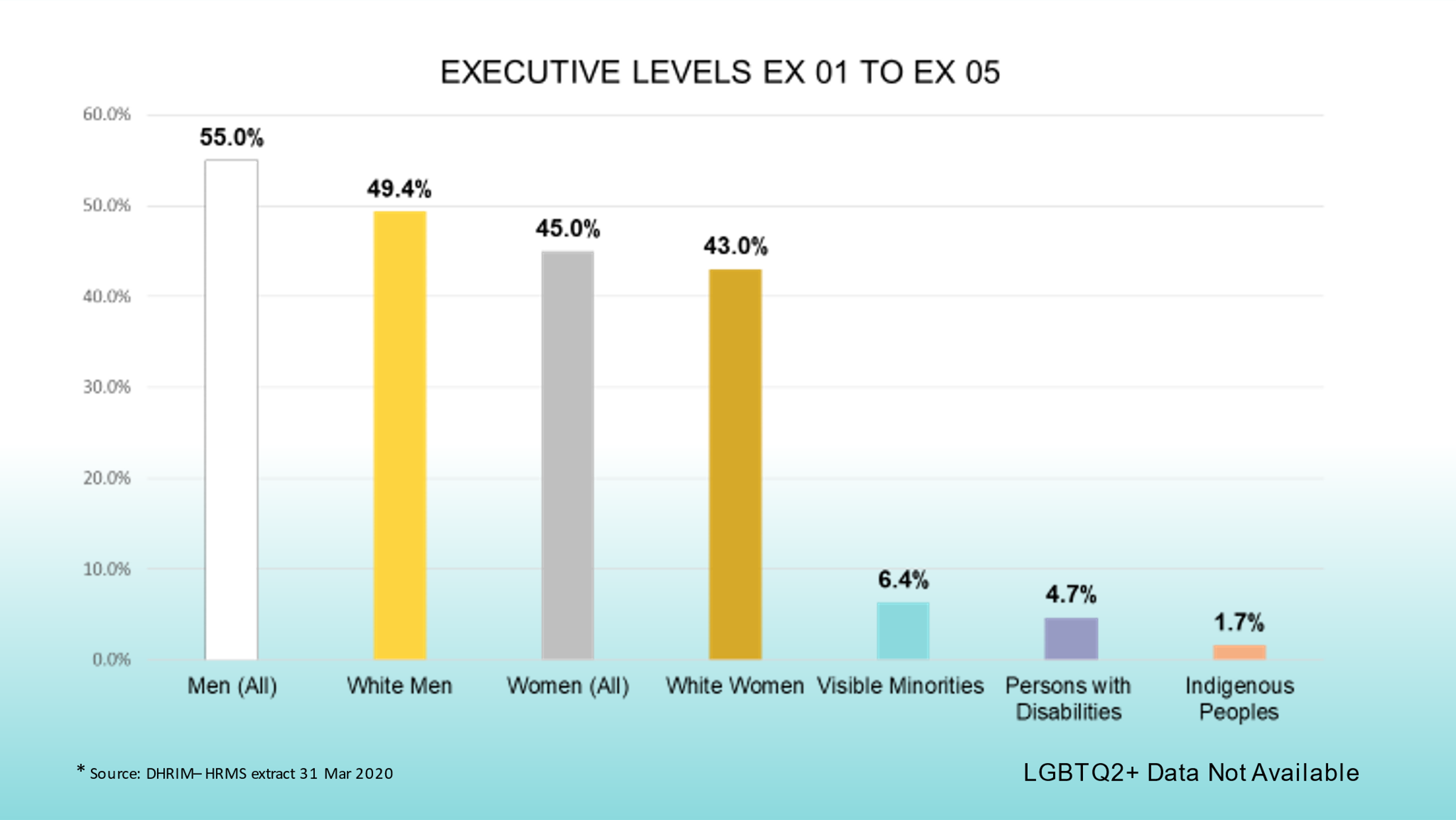

Retention

High retention rates can be an indicator of positive general morale and contribute to operational effectiveness. DND/CAF statistics demonstrate that Indigenous Peoples, visible minorities, women and persons with disabilities have much lower retention rates than white men. As a result, there are fewer individuals from these groups who reach higher rank levels or leadership positions.

In the CAF, the disparity becomes pronounced from the Sergeant and Lieutenant levels onwards. The disparity also exists at the Executive level of the National Defence civilian employee population. Again, data to compare representation of Employment Equity group members at lower-level civilian positions was not available to the Advisory Panel in time for this report.

It is important to understand that these observations do not diminish the value and contributions of white men within DND/CAF. Rather, they serve to signal that barriers are preventing all groups from equally thriving within the Defence Team. By the same token, they outline an opportunity to improve the demographic representation within the Defence Team.

Figure 3: Demographic Breakdown of CAF Non-Commissioned Members by Rank

Long description of Figure 3

CAF Non-Commissioned Members by Rank

| - | Private | Corporal | Master Corporal | Sergeant | Warrant Officer | Master Warrant Officer | Chief Warrant Officer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White Men | 69.6% | 74% | 75% | 77.2% | 80.7% | 85.4% | 86.9% |

| White Women | 14.8% | 12% | 13.7% | 14.9% | 13.2% | 9.6% | 8.9% |

| Indigenous Men | 4.8% | 4.8% | 3.3% | 2.3% | 1.9% | 1.9% | 1.1% |

| Indigenous Women | 1.2% | 1.2% | 0.8% | 1.1% | 0.6% | 0.6% | 0.4% |

| Visible Minorities Men | 7.9% | 7.9% | 8.7% | 5.8% | 3.1% | 2.3% | 2.2% |

| Visible Minorities Women | 1.6% | 1.2% | 0.9% | 0.7% | 0.4% | 0.4% | 0.4% |

| Persons with Disabilities Men | 0.7% | 0.7% | 1.2% | 1.2% | 1.3% | 1.4% | 1.3% |

| Persons with Disabilities Women | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.02% | 0.08% | 0.1% |

LGBTQ2+ Data not available

Source-2019 CAF EE Report Note: Only Canadian Army ranks are used as a space saving measure.

Figure 4: Demographic Breakdown of CAF Non-Commissioned Members by Rank (White Men Removed)

Long description of Figure 4

CAF Non-Commissioned Members by EE Group

| - | Private | Corporal | Master Corporal | Sergeant | Warrant Officer | Master Warrant Officer | Chief Warrant Officer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White Women | 14.8% | 12% | 13.7% | 14.9% | 13.2% | 9.6% | 8.9% |

| Indigenous Men | 4.8% | 4.8% | 3.3% | 2.3% | 1.9% | 1.9% | 1.1% |

| Indigenous Women | 1.2% | 1.2% | 0.8% | 1.1% | 0.6% | 0.6% | 0.4% |

| Visible Minorities Men | 7.9% | 7.9% | 8.7% | 5.8% | 3.1% | 2.3% | 2.2% |

| Visible Minorities Women | 1.6% | 1.2% | 0.9% | 0.7% | 0.4% | 0.4% | 0.4% |

| Persons with Disabilities Men | 0.7% | 0.7% | 1.2% | 1.2% | 1.3% | 1.4% | 1.3% |

| Persons with Disabilities Women | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.02% | 0.08% | 0.1% |

Source-2019 CAF EE Report

LGBTQ2+ Data not available

Figure 5: Demographic Breakdown of CAF Officers by Rank

Long description of Figure 5

CAF Officers by Rank

| - | Officer Cadet | 2nd Lt | Lt | Captain | Major | Lieutenant Colonel | Colonel | Brigadier General | Major General | Lieutenant General | General |

| White Men | 73.4% | 72.5% | 77.8% | 80.2% | 78.7% | 83.1% | 90.1% | 88.9% | 91.4% | 90% | 100% |

| White Women | 21.5% | 18.2% | 30% | 22.6% | 17.8% | 14.3% | 8% | 12.2% | 5.7% | 10% | 0% |

| Indigenous Men | 1.5% | 1.6% | 1.2% | 1.5% | 1.4% | 1.2% | 0.7% | 0% | 2.9% | 0% | 0% |

| Indigenous Women | 0.8% | 0.6% | 1.4% | 0.8% | 0.3% | 0.2% | 0.2% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Visible Minorities Men | 12% | 17.6% | 8.9% | 7.9% | 5.3% | 3.2% | 1.9% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Visible Minorities Women | 3.8% | 3.4% | 3.5% | 1.9% | 1.1% | 0.6% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Persons with Disabilities Men | 0.9% | 0.4% | 1.1% | 0.8% | 0.7% | 0.5% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Persons with Disabilities Women | 0.2% | 0.2% | 0.7% | 0.4% | .08% | .06% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

Source – 2019 CAF EE Report

LGBTQ2+ Data not available

Figure 6: Demographic Breakdown of CAF Officers by Rank (White Men Removed)

Long description of Figure 6

| - | Officer Cadet | 2nd Lt | Lt | Captain | Major | Lieutenant Colonel | Colonel | Brigadier General | Major General | Lieutenant General | General |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White Women | 21.5% | 18.2% | 30% | 22.6% | 17.8% | 14.3% | 8% | 12.2% | 5.7% | 10% | 0% |

| Indigenous Men | 1.5% | 1.6% | 1.2% | 1.5% | 1.4% | 1.2% | 0.7% | 0% | 2.9% | 0% | 0% |

| Indigenous Women | 0.8% | 0.6% | 1.4% | 0.8% | 0.3% | 0.2% | 0.2% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Visible Minorities Men | 12% | 17.6% | 8.9% | 7.9% | 5.3% | 3.2% | 1.9% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Visible Minorities Women | 3.8% | 3.4% | 3.5% | 1.9% | 1.1% | 0.6% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Persons with Disabilities Men | 0.9% | 0.4% | 1.1% | 0.8% | 0.7% | 0.5% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

| Persons with Disabilities Women | 0.2% | 0.2% | 0.7% | 0.4% | .08% | .06% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% |

Source – 2019 CAF EE Report

LGBTQ2+ Data not available

Figure 7: Demographic Breakdown of Civilian Executives within DND (Levels EX-01 to EX-05)

Long description of Figure 7

| Population | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Men (All) | 55% |

| White Men | 49.4% |

| Women (all) | 45% |

| White Women | 43% |

| Visible Minorities | 6.4% |

| Persons with Disabilities | 4.7% |

| Indigenous Peoples | 1.7% |

LGBTQ2+ Data not Available

*Source DHRIM-HRMS extract 31 Mar 2020

Canadian Demographics and Implications for the Future

The underrepresentation of Employment Equity group members within the Defence Team is expected to worsen unless drastic changes are made to address systemic discrimination, racism and misogyny within National Defence’s "system."

According to the data:Footnote 93

- The number of Canadians in the Canadian labour force (including employed and unemployed) is expected to increase from 19.7 million in 2017 to 22.9 million in 2036.

- The populations of Indigenous Peoples and persons with disabilities are statistically younger than other groups and thus are currently less proportionally represented in the available labour market. However, these groups are growing steadily, and their Labour Market Availability will follow suit.Footnote 94

- In 2016, just over 1 in 4 working people (26%) were born outside Canada. By 2036, this proportion could reach 1 in 3 working people (34%).

- Factors such as climate change, food insecurity and global conflicts will contribute to bringing more visible minority immigrants to Canada.Footnote 95 The proportion of people belonging to visible minorities in the labour force who were born in Canada is expected to increase from 20% in 2016 to 26% of the labour force by 2036 (33.5% in Ottawa). For both these reasons, in all regions, the increasing ethnocultural diversity of the labour force is expected to continue.

- In 2017, 22% of the Canadian population (15 years and over) had one or more disabilities. Among those aged 25 to 64 years, 59% are employed.

- Women remain the largest underrepresented group within the CAF. Although they represent 48% of the LMA, only 18% of women are currently represented in the CAF. Certain occupations and trades see less than 4% of women within their ranks.

Based on these trends and statistics, as the Canadian population grows, so will the chasm between the composition of National Defence and society. This is not inconsequential: the failure to consider and address the reasons for the widening rift between Canadian demographics and the composition of the Defence Team means that some positions will not be filled. Tapping a broader talent pool is the only viable solution to meeting recruitment needs without sacrificing mission readiness and operational effectiveness.

Summary of Part I

Racism in Canada is not a glitch in the system; it is the system. Colonialism and intersecting systems such as patriarchy, heteronormativity and ableism constitute the root causes of inequality within Canada. Throughout Canada's history, the existence of systemic and cultural racism has been enshrined in regulations, norms, and standard practices. Canada has recognized, and continues to acknowledge, its history of racial discrimination by introducing Canada's Charter of Rights and Freedoms, the Canadian Human Rights Commission, and the Canadian Multiculturalism Act, as well as the repealing of discriminatory policies and practices.

The Defence Team's foundational values were chiselled from Canadian ones, and formed the basis of all its practices, assumptions and approaches. The Defence Team's work schedules and holidays which are mostly based on its Christian traditions, the food prepared in mess halls which often revolves around traditional recipes from Euro-Canadian meals, and the gendered language of French—and of some English words—these are all cornerstones of unintentional biases. These practices are codified, personally and collectively, into the daily lives of each member of the Defence Team. Although at first glance they do not appear to be pernicious threats to equity, they greatly influence the comfort gauge for those who prefer a more homogenous society. Life is easier when everyone is the same. Adapting different rules, changing methodologies, and evolving norms requires effort.

Dismantling Canada's colonial culture, to which the Defence Team leadership subscribes, requires this sustained and deliberate effort. It involves feeling uncomfortable and amenable to being stretched emotionally. It calls for an organization to become more tolerant of mistakes made in good faith and better at supporting a willingness to learn from these mistakes. It also entails being bold and visionary while reviewing discriminatory structures such as laws and policies. On occasion, it necessitates artificially increasing the representation of women, Indigenous, Black and other racialized people, and people with disabilities, until archaic paradigms and systemic barriers no longer prevent them from naturally thriving in the workplace. Recognizing that the health of the National Defence organization is hampered by the powerful constraints of its inherited colonialist culture is the first step in deliberately instituting meaningful change. Throughout its mandate, the Advisory Panel witnessed many statements from members and leaders of the Defence Team that hinted at this recognition. They were ready to feel uncomfortable.

Perhaps they will lead the path forward to a new era of inclusivity, diversity, equity and accessibility.