The Imperial Wars

Iroquois chief between 1760-1790 (Reconstitution by G.A. Embleton (Parks Canada))

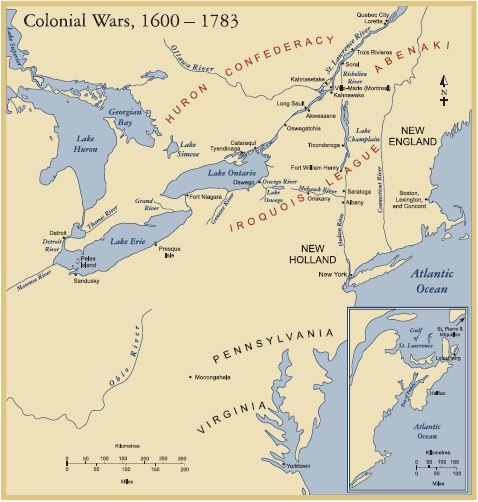

After 1689, imperial rivalries between France and England began exerting an increasingly significant influence on North American politics. King William’s War (1689-1697), the War of the Spanish Succession (1702-1713), the War of the Austrian Succession (1740-1748) and the Seven Years’ War (1756-1763) all stemmed primarily from European antagonisms. External developments had little direct influence on already-existing alliances, but new rivalries were superimposed over ancient Aboriginal conflicts and gradually came to overshadow them.

The Imperial Wars

In 1689, at the beginning of the imperial wars, New France had approximately 12,000 inhabitants, while the British colonies to the south had a population of more than 250,000. Seventy years later, at the time of the Conquest, Canada’s population was still only 70,000 habitants, while that of the Thirteen Colonies was more than 1.5 million. The British colonies were confined to a narrow strip along the Atlantic coast, while New France stretched from Acadia to Louisiana to what became the Canadian Prairies. To compensate for their demographic and geo-strategic weakness, the French had to rely on their Aboriginal allies. Largely thanks to them, New France was able to survive until 1760. While they supported the French in their battles, however, Aboriginal peoples did not become mere instruments of French imperialism. They also continued defending their own interests.

King William’s War, 1689-1697

The expansionist policy of King Louis XIV of France led to King William’s War between France and an English-Dutch-Austrian alliance in the late 17th Century. The conflict spilled over into the Americas, beginning with the arrival of the Comte de Frontenac in Canada in 1689. The Governor’s initial plan was to conquer the British colony of New York. He hoped that this would isolate the Iroquois and force them to stop their raids on New France. When Frontenac arrived in New France it was too late in the season to carry out this plan and he had to settle for less ambitious projects.

In the month of January 1690, the French organized three expeditions against the British colonies of New England. Under the leadership of French-Canadian officers of the Troupes de la Marine, such as Jean-Baptiste Hertel de Rouville and Pierre Le Moyne d’Iberville, parties composed of both Canadian militiamen and Aboriginal warriors attacked British villages and forts. Their tactics wed surprise attack and siege warfare in an effective combination of Aboriginal guerrilla tactics and European techniques. The first detachment, composed of 96 Iroquois warriors and 114 French-Canadians, left Montreal and headed due south to attack the village of Schenectady. The allies arrived on 9 February in the middle of the night and launched a surprise attack on the inhabitants: ‘The war cry rang was sounded in the manner of the Savages and everyone attacked at once.’ The houses were set aflame, the entire garrison was put to the sword, and all who tried to defend themselves were killed. Only 50 old people, women and children managed to escape and survived. Thirty Iroquois who were in the village at the time were also spared: ‘They were made to understand that our argument was only with the English.’ The large number of “mission” Iroquois among the French troops undoubtedly accounted for the conciliatory attitude towards these resident Iroquois. The second party consisted of 25 French-Canadians and 25 Abenaki and Algonquin from Sillery. It headed for the settlement of Salmon Falls in New Hampshire, where it arrived on 27 March. The contingent attacked three small forts, took 54 British prisoners and ‘withdrew for fear of falling into the hands of 200 English … who were pursuing it.’ It joined up with the third detachment, composed of 50 French-Canadians and 60 Abenaki from the Saint-François mission, who had set out from Quebec City for the Casco Bay area in Maine. Other Abenaki from Acadia joined the group. In the end, 400 to 500 warriors and 75 French-Canadians marched together on Fort Loyal and laid siege to the post. According to one account,

The trench was opened on the night of the 28th [of May]. Our Canadians and our Savages were not greatly experienced in the art of laying siege to a place. They did not stop working vigorously and by good fortune they had found in abandoned forts tools suitable for moving earth. The work advanced with such speed that … by the next morning … we would have arrived by trench at their palisades and set them on fire with a barrel of tar we had also found and some other combustible materials. Seeing this apparatus coming near and being unable to prevent it … [the British] raised the white flag to surrender.

In addition to these major expeditions, Aboriginal groups also launched small individual raids on border villages in the British colonies, from which they brought back scalps and sold them to the French. The French encouraged the practice with the aim of weakening the British and sowing terror among the British settlers, but were soon overwhelmed by the effectiveness of the Aboriginal warriors. Gédéon de Catalogne reported:

To induce our Savages not to reconcile with the English, Mr. de Frontenac promised them 10 écus for each scalp they brought back, and as a result we always had parties in the field and often scalps, from whom we could learn nothing. Therefore, the order was subsequently changed, which is to say that a low price was paid for scalps but for each prisoner we gave 20 écus (that is, those that were captured around Boston or Orange [Albany]) and for those from the countryside, 10 écus, in order to have reliable news [about the British colonies].

Finally, the allies of the French also helped defend the colony against the British. After the attacks on Schenectady, Salmon Falls and Casco Bay, the British responded by launching two expeditions against New France. The first was an impressive naval expedition against Quebec City in 1690, in which indigenous allies do not appear to have been involved. Aboriginal war parties did, however, take part in the second, which was launched the following year by the Mayor of Albany, Peter Schuyler, against the fort at La Prairie-de-La-Magdelaine. A group of Odahwah, Algonquin from Témiscamingues, Huron from Lorette and Iroquois from Sault Saint-Louis fought alongside the French to repel a mixed enemy contingent of approximately 270 New York militiamen and 150 Mohegan and Five Nations warriors.

In Acadia, hostilities had resumed between the maritime Algonquians and the British even before King William’s War broke out. In 1688, the Abenaki responded to British encroachment and set out to attack most of the British settlements along the Atlantic coast of Maine, vowing that ‘neither they, nor their children, nor their children’s children would … ever make [peace] with the Englishman, who had so often betrayed them.’ In 1692, they succeeded in driving the British out of Fort Pemaquid (now Bristol, Maine), after which they pillaged and razed the settlement. Meanwhile, the Mi’kmaq attacked the British boats that came to fish along their coasts. In 1696, it was reported that Mi’kmaq from the St. John River, joined by several Abenaki from Pentagoët,

… set out in canoes to the number of 70 for a raid on the English; as they proceeded along the coast they encountered a small English vessel which they attacked and captured …. The Indians took their prize into Pentagoet river, pillaged her of all merchandise and money amounting to 1000 or 1200 livres, which they found on board, and held her crew of 7 Englishmen as prisoners.

The conflict between the French and British was superimposed on the ancient rivalry, creating a new dynamic in the war waged by the Mi’kmaq and the Abenaki. For example, the Mi’kmaq, who proved skilful in privateering, began appearing as buccaneers on French ships. Thanks to the missionaries and the settlers who were now living in Aboriginal villages, the French were able to turn Anglo-Aboriginal hostility to their advantage. The Baron de Saint-Castin in particular played an important role in the war, so much so that the New England settlers called the conflict ‘Saint-Castin’s War.’ In the winter of 1690, for example, he urged his Abenaki allies to join with the Franco-Aboriginal force attacking the village of Casco Bay. Then, in 1695, he persuaded the Abenaki and the Mi’kmaq to join Pierre Le Moyne d’Iberville’s fleet and lay siege to Fort Pemaquid, which the British had just rebuilt. Among other things, the indigenous men prepared the way so the French troops could pull the canon and mortar from the ships to the fort.

While the alliance with the French lent the Aboriginal nations support in their own war with the British, it was also at times an obstacle to the promotion of their interests. For example, in 1693, Abenaki chiefs attempted to negotiate a peace with the British but the French made every effort to sabotage the talks, inducing their Aboriginal allies to take up the hatchet again.

The War of the Spanish Succession, 1702-1713

Mi'kmaq warrior c. 1740 (Reconstitution by Francis Back. Fortress Louisbourg (Parks Canada))

The War of the Spanish Succession was in some ways a continuation of King William’s War. In 1700, King Charles II of Spain died without issue and ceded his crown to Philip of Anjou, the grandson of Louis XIV. To prevent the French and Spanish thrones from being unified, England, the Netherlands and Austria renewed their alliance and declared war on France on 13 May 1702.

When news of the war reached North America in the fall of 1702, the Abenaki voiced their intent to remain neutral. Deprived of his valuable allies, French governor Philippe de Rigaud de Vaudreuil organized a raid on the villages of Casco and Wells in New England the following year, strongly encouraging the Abenaki to join him. Although few of them heeded his call and the troops were made up primarily of Canadians and mission Iroquois, the British authorities immediately reacted by declaring war on the Abenaki, who were thus drawn into the conflict against their will. Imperial rivalries slowly began to redefine Aboriginal conflicts.

Etow oh Kowan, an Iroquois Chief, 1710

In aboriginal, as in white society, political and military status was indicated by elaborate clothing and insignia. This Iroquois chief, prominent around 1700, is depicted dressed for formal occasion in a mixture of aboriginal and white garments. Note that he is holding a war club but also carries a decorated European sword in a scabbard, possibly presented to him as a ceremonial gift by either the French or English crowns. (Library and Archives Canada (C-092421))

In the ensuing years, the Abenaki continued to attack British posts in Maine and Massachusetts. In 1708, 60 Abenaki joined 100 French and 220 mission Iroquois in a raid on the village of Haverhill. They also helped repel the British attacks on Port Royal in 1707 and 1708. A third attack, in 1710, was successful and the town fell into British hands. When the war ended in 1713, the Treaty of Utrecht ceded Acadia to England according to its ‘ancient boundaries.’ Both Mi’kmaq and Abenaki were furious upon learning the French had surrendered their traditional territories in the treaty, lands that in their view the French had no right to dispose of, and which they had no intention of leaving. To solidify their rights over their newly conquered territory, the British rapidly set up a few posts in Acadia. At first the Abenaki anger with the French and desire for more competitive fur prices ensured that they greeted the British settlements peacefully. However, the French were not happy with British expansion into territory they hoped one day to recover and thus attempted to rebuild their relationship with the Abenaki and Mi’kmaq. In time, they were able to do so, and through their missionaries in Acadia (including Father Sébastien Râle, who lived among the Abenaki of Narantsuak, and Father Antoine Gaulin, who lived among the Nova Scotia Mi’kmaq). French encouragement and British provocations led to a rekindling of Abenaki and Mi’kmaq hostilities with the British. In 1716, the French king even set up a special fund of 2,000 pounds to fund the distribution of annual gifts to the Abenaki and Mi’kmaq.

The Anglo-Abenaki war did not flair anew until 1722, but the Mi’kmaq began boarding British vessels fishing in their waters in 1715: they captured nearly 40 vessels between 1715 and 1722. As anthropologist Harrald Prins wrote:

Each summer, to the resentment of the French, some 200 New England vessels fished off the Nova Scotia coast. From 1715 to 1722, Mi’kmaq seafighters harassed this fleet. Armed and encouraged by their French allies entrenched at Cape Breton, they formed an intrepid force of about 60 marines. Cruising along their coasts in shallops, or sometimes paddling their swift canoes, they searched for ketches and schooners hailing from distant ports. Especially when anchored in some cove, these British vessels were easy targets for surprise attack. Falling upon their prey, Mi’kmaqs would try to board the vessel and surprise the crew. Rather than killing the fishermen, the Mi’kmaq preferred to take them alive for ransom. Plundering whatever was deemed valuable, including the cargo of dried fish, they would bring their spoil to French settlements for sale.

Mi'kmaq chief c. 1740 (Reconstitution by Francis Back. Fortress Louisbourg (Parks Canada))

It must not be supposed that these Aboriginal warriors were acting simply as mercenaries on behalf of the French. On the contrary, they were primarily seeking to protect their own interests and their lands. When the British tried to explain to the Abenaki that the Treaty of Utrecht made them British subjects, one Abenaki chief replied that ‘the King of France can dispose of what belongs to him; as for him, he had his land, where God had placed him, and as long as there was one child of his nation alive, he would fight to keep it.’ Settler penetration into the interior and into Abenaki lands was the spark for renewed fighting, with the western Abenaki sagamore Grey Lock effectively sweeping settlers from what is now New Hampshire and parts of Vermont with a highly effective guerrilla campaign based out of the Green Mountains. Further east the war went against the Abenaki. When the war finally ended in 1726, the Abenaki and Mi’kmaq signed treaties with the British, recognizing the British right to settle on Aboriginal territory.

While Massachusetts was seriously affected by the Franco-Aboriginal attacks, the colony of New York was mostly spared by the war. The Canadian and New York authorities informally agreed at the outset of hostilities to remain neutral. This agreement primarily served the interests of the Aboriginal peoples and in fact was negotiated by the Iroquois, who likely wanted to avoid being dragged into the conflict by the British and having to face raids by the French and their allies again. As they explained to the French governor:

You Europeans are evil spirits, said one Iroquois chief. You quarrel in God’s name and take up the hatchet for petty things. We on the other hand do not take up the hatchet unless we see blood being shed and heads being cut off. To prevent this from happening, I am taking up my father Onontio’s hatchet and have asked my brother Corlard [the governor of New York] to take his and we shall bury them both in the pit where my late father Onontio cast them when he made the great peace.

The mission Iroquois (particularly those from Sault St. Louis) also benefited greatly from the truce, which allowed them to travel freely to Albany, where their furs commanded higher prices than in Montreal. Significant clandestine trading between Montreal and Albany ensued as the Iroquois started bringing furs purchased from Montreal merchants to the New York capital. The Canadian authorities turned a blind eye to the illicit trade, since it allowed the colony to dispose of its surplus furs and purchase goods it otherwise could not.

War of the Austrian Succession, 1740-1748

With the Treaty of Utrecht, signed in 1713, France and England remained at peace until 1744. For 30 years, there was no conflict between New France and the British colonies. However, peace did not extinguish imperial ambitions and the Anglo-French rivalry in North America continued unabated. Governor Vaudreuil’s dealmaking to encourage the Mi’kmaq and Abenaki to resist British expansion into Acadia is a clear illustration of that rivalry. To compensate for their loss of territory, the French built the fortress of Louisbourg, one of the largest military establishments ever built in North America, on Île Royale (Cape Breton Island). They hoped to defend Canada against possible British invasion and protect their interest in the east coast fishery. The British, on the other hand, took advantage of the peace to establish trade ties with the Great Lakes nations, hoping to destabilize the Franco-Aboriginal alliance, among other things. Slowly, British traders even began to venture into the Ohio region, where many Aboriginals had returned to after the Peace of Montreal and the waning of Iroquois power.

The War of the Austrian Succession began in 1740, when England declared war on Prussia, which wanted the throne of young Empress Maria Theresa of Austria. Four years later, France joined Prussia and Spain against England, once again dragging America into war. This time, the French had great difficulty garnering the support of their Aboriginal allies in fighting the British. In 1745, Governor Charles La Boische de Beauharnois complained of the “mission Indians’” lack of interest in fighting the British. As he put it, ‘the village of Sault St. Louis would readily remain neutral.’ Obviously, the mission Iroquois’ best interests lay in maintaining neutrality with the colony of New York, so they could protect their lucrative fur trade. Faced with the lack of enthusiasm, the governor assembled a party of 200 French-Canadians under the command of Paul Marin de La Malgue to ‘descend on the coast near Boston.’ They were joined by 300 or 400 mission Iroquois and Abenaki. In the end, the party changed its destination and attacked the village of Saratoga, taking a hundred prisoners in the process. The following year, Pierre-François de Rigaud de Vaudreuil led a detachment of 400 French and 300 mission and Great Lakes warriors against Fort Massachusetts (Adams, Massachusetts). According to one observer, ‘The party wreaked havoc, burning down all the settlements and crops they could find within 15 leagues, including barns, mills, churches, tanneries, etc.’ Even as they took part in the French military activities, however, the indigenous nations were trying to protect their interests. The Iroquois from the Sault and the Lake of Two Mountains, for instance, were very reluctant to continue scouting along the New York border, for fear of coming into conflict with their brothers in the League.

Only the Mi’kmaq and Abenaki were eager to go to war against the British. Encouraged once again by their missionaries, the two nations took part in two sieges on the town of Annapolis Royal in 1744 and 1745, both of which were unsuccessful. In 1745, the British captured the citadel of Louisbourg, which the French had believed was impregnable. Hoping to recapture the fortress, the French launched two expeditions, with the assistance of hundreds of Abenaki and Mi’kmaq, but to no avail. The allies had greater success on Île Saint-Jean (Prince Edward Island) in 1746, when a 100 or so Mi’kmaq and 15 French managed to repel a British squadron of 200 men trying to capture the post of Port La Joie (now Adams, near Charlottetown).

In the Great Lakes, Aboriginal peoples appeared sympathetic to the French cause at first. In 1744, Governor Beauharnois wrote that the Odahwah, Huron and Miami from Detroit ‘had taken up the hatchet presented to them to attack the British at Belle Rivière over the winter.’ A few raids were even launched on the Pennsylvania and Virginia borders in 1744. But the willingness to assist the French quickly turned to hostility. Following the capture of Louisbourg, the British were able to prevent French vessels from entering the St. Lawrence. Quebec City’s supplies were thus cut off, resulting in a scarcity of ammunition and trade goods. Trade in the Great Lakes region was quickly brought to a standstill and the price of goods for Aboriginal traders skyrocketed. In addition, the French were no longer able to give their allies the annual gifts on which they were increasingly dependent. According to historian Richard White, Aboriginal peoples saw the sudden change as ‘an example of French greed that violated the alliance.’ The French were subsequently unable to garner the support of their allies, who preferred to remain neutral in the conflict. In 1747, French officer Charles des Champs de Boishébert complained of an ‘agreement among the redskins these past years to stop destroying one another and let the pale-faces fight it out.’ Some communities turned hostile to French presence in the region, killing any coureurs de bois they came across and seizing their goods.

In October 1748, the Treaty of Aix-La-Chapelle put an end to the War of the Austrian Succession, to the great relief of the French, who were able to recover the fortress of Louisbourg in exchange for the island of Madras, which had been captured from the British in 1746, and to re-establish order in the Great Lakes. However, the massive and concerted opposition to French authority, though it had lasted just a few years, represented the first large-scale pan-Aboriginal movement in the Great Lakes region and it paved the way for Pontiac’s uprising of 1763.

Seven Years’ War, 1756-1763

Unlike previous conflicts, the Seven Years’ War broke out in North America and then spread to Europe. The Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle, which had put an end to the War of the Austrian Succession, simply restored the status quo ante bellum in America; the Anglo-French rivalry that had begun in the Ohio Valley remained alive and well. The French claimed ownership of the territory, saying they had discovered it in the 1680s. The British also claimed ownership, having acquired the rights in the Lancaster Treaty of 1744 from the Iroquois (who claimed they had conquered the region in the 1650s). To defend their interests, the French organized an expedition to Ohio in 1749, hoping to officially take possession of the territory, chase off the British traders and re-establish order among the Aboriginal ‘rebels.’ In 1753, a group of land speculators from Virginia created the Ohio Company and bought the rights to the Ohio Valley from King George II of England, hoping to place settlers on the land. That same year, the French built two forts in the region (Le Boeuf and Presqu’île) to maintain contact between Canada and Louisiana. Considering the move an affront, the Virginians sent an armed contingent under the command of the young George Washington to drive out the French and secure their rights. The battle that broke out between the French and British troops marked the start of the hostilities known in the British colonies as the French and Indian War.

While Aboriginal peoples had been reluctant to defend the French in the previous war, they did not hesitate to lend their support this time. The main reason for the about-face was the negative Aboriginal perception of the British and their territorial policy. Speaking to Aboriginal peoples from the Great Lakes region in 1754, one mission Iroquois sought to persuade them of the fundamental difference between French and British colonial practices:

Brothers, do you know the difference between our father and the English? Go and take a look at the forts our father has built and you will see that the land beneath their walls is still a hunting ground, for they have been placed in these places frequented by us only to make it easier for us to meet our needs, whereas as soon as the English take possession of the land, the game are forced to leave, because the trees are felled, the land is cleared and we can hardly find anything to give us shelter at night.

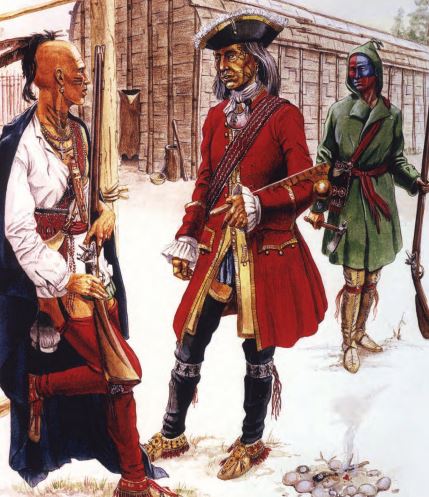

Eastern Woodland Warriors at the time of the Seven Years’ War

This modern reconstruction shows a Chief and warriors of the Eastern Woodland people as they may have appeared in the 1750s during the great struggle between France and Britain for control of North America. They are wearing a mixture of white and aboriginal clothing but their weapons are mainly European. One warrior has painted his face, a traditional activity before entering combat. (Painting by David Rickman (Department of National Defence))

Initially, Aboriginal support gave the French an advantage over the British. In 1754, a group of 100 Aboriginal men and 500 French captured a British fort in the Ohio Valley (Fort Necessity) defended by about 300 soldiers. The following year, an army of 1,500 British regulars and militiamen marched on Fort Duquesne on the Monongahela River, a tributary of the Ohio, to drive the French out. A counter force of 637 Aboriginals and 263 French laid an ambush and routed the British army killing or wounding 977 men, while suffering light losses. Many look at this battle as the classic example of the superiority of Aboriginal guerrilla warfare over traditional European battle techniques in thick forest. Historian Peter MacLeod writes:

As the allied centre stabilized, the British began to learn the limitations of grenadier tactics in a forest. Formed in line, standing upright, they had gained a fleeting ascendancy over the French, but now presented a conspicuous target to enemies who had ‘always a large mark to shoot at and we having only to shoot at them behind trees or laid on their bellies.’ The field guns were silenced by the Aboriginals who ‘kept an incessant fire on the guns & killed ye men very fast.’

Canadian militiaman wore short capots, leggings, breeches and moccasins when leaving on lengthy expeditions through the forest. (Reconstitution by Francis Back. (Parks Canada))

In 1755, France decided to send 3,000 ground troop reinforcements to the colony under the command of General Jean-Armand Dieskau. The move initially had little impact on the Aboriginal peoples, who continued to play a vital role in the fighting. That same year, for instance, 600 Aboriginal men, 600 French-Canadian militiamen and 200 French regulars attacked a British camp entrenched at Lake George, in Mohawk territory. The following year, 250 Aboriginal warriors took part in the siege of Fort Oswego on the southern shores of Lake Ontario, along with 2,787 French soldiers and militiamen led by General Montcalm, who had succeeded Dieskau.

However, while the Canadians (including Governor Pierre de Rigaud de Vaudreuil) had always based their military tactics on extensive Aboriginal participation, the regular soldiers recently arrived from France showed indifference bordering on disgust for Aboriginal guerrilla tactics. The French officer Louis-Antoine de Bougainville, for instance, wrote that Aboriginal warriors were a necessary evil, adding, ‘What a scourge! Humanity groans at having to make use of such monsters, but without them, we would be outnumbered.’ It was not long before Aboriginal peoples realized that they were held in contempt by the French officers. By 1757, 820 “mission Indian” and 979 Great Lakes Aboriginal people (from a total of 32 nations) accompanied 6,753 French soldiers (regulars and militiamen) to lay siege to Fort William-Henry south of Lake George. On that occasion, the Marquis de Montcalm’s lack of regard for the opinions and tactics of his Aboriginal allies offended them greatly. They said: ‘My father, you have brought the art of war from the world beyond the great lake to this place; we know you are a grand master of this art, but we are more skilled in the science and cunning of scouting; we know more about these woods and how to make war in the woods. If you consult us, you will not be disappointed.’ European style siege warfare, with no hand-to-hand combat, left indigenous warriors disgruntled and standing on the sidelines, unable to capture prisoners, take scalps or obtain booty. Their frustrations were not set aside when Montcalm offered the surrendering garrison the honour of marching away with their arms, baggage train and flags flying. The arcane formalities of European warfare made no sense to them whatsoever. Hundreds of warriors would stalk the column as it marched away, and accosted the panicked soldiers, and non-combatants in search of plunder and captives. This confused and dangerous scene included many killings, beatings and captures, but was subsequently blown massively out of proportion in the British colonies, with wild claims of a three hour slaughter of hundreds, perhaps more than a thousand men, women and children. Ian Steele in his recent analysis of the event estimated that between 67 and 184 British were killed. The chaotic scene marked the British psyche deeply: the ‘massacre’ became a symbol of Aboriginal savagery and perfidy and, by extension, their French allies. However, when it comes to massacres, there was little to choose between the French and the British during this period. For instance, in 1759, a group of British rangers led by Robert Rogers razed the Abenaki village of Bécancour, because its inhabitants had refused an offer of neutrality from British diplomats. During the raid, the rangers burned down the entire village, killing about 30 people and capturing five. At least two of the captives were eaten by the rangers, who were short of provisions.

By 1758, relations between the French and Aboriginal peoples had deteriorated even further. Montcalm was at Fort Carillon on Lake Champlain and had just held out against a siege by an army of nearly 15,000 British soldiers. When the warriors from Sault St. Louis arrived, the battle was already over. Montcalm was particularly ungracious in his greeting, stating, ‘Now that you’re here, I no longer need you. Did you come only to see bodies? Go out behind the fort and you’ll see some.’ The general even refused to allow the warriors to go reconnoitring in the enemy camp, telling them, ‘You can go to the devil if you’re not happy about it.’ Offended, the warriors returned to Montreal and complained to Governor Vaudreuil, who reacted by issuing a severe reprimand to Montcalm, reminding him of the crucial role indigenous allies had always played in the military affairs of New France. Montcalm and Vaudreuil’s respective attitudes are symptomatic of the gulf that had opened between French and Canadian societies.

By 1759, the tide had begun to turn against France. The year before, the British Prime Minister, William Pitt, had decided to invest huge sums in the colonial war. He managed to raise an army of 23,000 men, 13,000 of whom were sent to attack Louisbourg under the command of James Wolfe in 1758. About 200 Mi’kmaq stood alongside about 2,500 French in the assault, but after nearly 22 days of siege, the town was forced to surrender. The following year, a squadron of 11,000 British soldiers was dispatched against Quebec City. In 1755, London had decided to centralize management of American Indian affairs and take charge of the matter. Two departments were created, one for the northern colonies and one for the southern colonies. Sir William Johnson, a man who had influence with the Iroquois Five Nations, was made superintendent for the north. The new policy was highly effective and by 1759 Johnson had convinced the Iroquois to take up the hatchet against the French and participate in an attack on Fort Niagara, one of the strategic points in New France’s defence network.

Despite the increasingly arrogant attitude of certain French administrators, many indigenous nations remained allied with them until the surrender of Quebec City in the fall of 1759. At the battle of the Plains of Abraham, Aboriginal marksmen lay in wait in the bushes with Canadian militiamen along the northern flank of the battlefield. According to historian Peter MacLeod, ‘Some of the first shots of the Battle of the Plains of Abraham were fired by Amerindians.’ They also assisted the Canadian militiamen in covering the retreat of the French troops. As one French soldier reported in the aftermath of the battle, the British who pursued the retreating troops ‘encountered Indians and irregulars lying in wait in the woods.’ But their impact on the battle was minimal, things had changed in North America: the decisive action was the clash of regular British and French armies on the Plains.

The end of the Franco-Aboriginal alliances

Bust of a Mohawk Indian by Sempronius Stretton, 1804

This man is depicted wearing the red, black and yellow face paint favoured by warriors about to enter combat. The helmet style head-gear was a favourite of the Iroquois peoples and the warrior has adorned himself with jewellery and ornamentation that derives from both aboriginal and white sources. Note the crucifix. (Library and Archives Canada (C-14827))

In order to weaken the French, the British tried to break the Franco-Aboriginal alliance and neutralize their warriors. As early as 1755, William Johnson was sending messages to the Aboriginal peoples in the St. Lawrence Valley through the Iroquois League, encouraging them to let the British and French fight it out between them. The Aboriginal leaders politely refused Johnson’s invitation, however, saying they and the French were of the ‘same blood’ and they preferred to die with them.

Johnson made other overtures during the war to convince the mission communities to remain neutral, but it was not until 1760 that the allies finally agreed to lay down their weapons. At the time, over 18,000 British soldiers were converging on Montreal, the last bastion of the French in Canada. One force, under the command of William Haviland, was approaching via the Richelieu River; a second contingent, under the command of James Murray, had left Quebec City and was travelling up the St. Lawrence; lastly, General Jeffrey Amherst and William Johnson were leading a third army that had left Lake Ontario and was travelling downstream by boat. Faced with such an overwhelming opponent, the Aboriginal nations had no choice but to negotiate peace. On August 30, at Oswegatchie (or La Présentation, a village of mission Iroquois established by the Jesuits in 1749 on the site of the current town of Ogdensburg, New York), William Johnson met with representatives of the Seven Nations of Canada, which included all the “mission Indians” in the St. Lawrence Valley, and entered into a treaty with them:

Some of these Indians joined us, rapporte [sic] Johnson, and went upon parties for prisoners etc., whilst the rest preserved so strict a neutrality that we passed all the dangerous rapids, and the whole way without the least opposition, and by that means came so near to the other two armies, that the enemy could attempt nothing further without an imminent risk of the city and habitants.

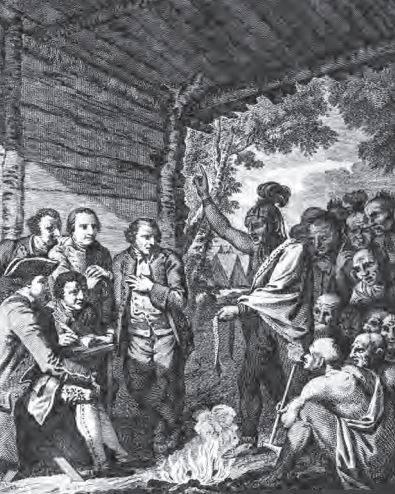

Aboriginal Council, 1764

Following the victory in the Seven Years' War, British authorities disregarded Johnson's advice to continue the practice of giving annual gifts to the Crown's aboriginal allies. The result was unrest that culminated in the Pontiac Rebellion of 1763. This illustration depicts one of the councils between aboriginal leaders and British officers which ended the rebellion and restored good relations with the Crown's important allies. (Library and Archives Canada (C-000299))

On September 8, 1760, to avoid fighting a hopeless battle, Governor Vaudreuil signed the surrender of Montreal. A week later, the Seven Nations of Canada met with William Johnson once again in Sault St. Louis, where they confirmed the Treaty of Oswegatchie. Basically, Johnson promised the Native peoples that they could keep ‘the peaceable possession of the spot of ground’ on which they were living, continue to practise their religion and maintain their customs, and benefit from ‘a free trade open.’ In return, Aboriginal groups agreed to ‘burry the French hatchet we made use of, in the bottomless Pitt, never to be seen more by us or our Posterity.’

For their part, the Abenaki and Mi’kmaq found themselves isolated after the deportation of the Acadians in 1755 and the fall of Louisbourg in 1758. Without their French allies, the two nations had no choice but to make peace with the British, and did so in June 1761. The destruction of the Abenaki village of Bécancour by Robert Rogers’ rangers two years earlier may have caused the maritime Algonquians to consider the fate awaiting them if they continued to resist British authority. Whatever the case, when the Treaty of Paris officially ended the Seven Years’ War in 1763, peace was already well established between them and the British in eastern Canada.

Related reading

BEAULIEU, Alain, Les autochtones du Québec: des premiéres alliances aux revendications contemporaines, (Québec : Éditions Fides, 2000).

CHARTRAND, René, Canadian military heritage: Volume II (1755-1871), (Montreal : Art Global, 1995).

DICKASON, Olive Patricia, Canada’s First Nations: a history of founding peoples from earliest times, 3rd ed., (Don Mills, Ont. : Oxford University Press, 2002).

HAVARD, Gilles, The Great Peace of Montreal of 1701: French-native diplomacy in the seventeenth century, (Montreal : McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2001).

LACKENBAUER, P. Whitney, Craig Mantle and Scott Sheffield, eds., Aboriginal Peoples and military participation: Canadian and international perspectives, (Kingston, Ont. : Canadian Defence Academy Press, 2007).

MILER, James R., Skyscrapers hide the heavens : a history of Indian-white relations in Canada, 3rd ed., (Toronto : University of Toronto Press, 2000).