The Arrival of the Europeans: 17th Century Wars

When Europeans began colonizing North America, they encountered warring Aboriginal nations. The pre-existing conflicts helped shape the networks of alliances that formed between the newcomers and the Aboriginal peoples, and had a significant impact on colonial wars up to the end of the 17th Century.

First Contacts

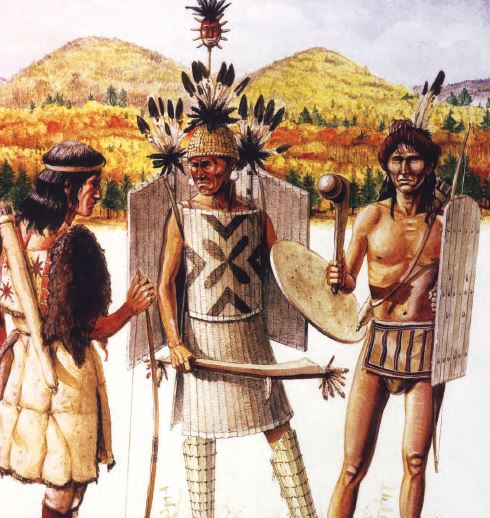

Eastern Woodland Warriors c.1600

This painting by David Rickman shows three Eastern Woodland warriors with a variety of clothing and weapons. The figure in the center represents a war chief wearing wood lathe armour and carrying a war club. On the left is an archer in winter dress and on the right is a warrior in summer dress armed with a bow and a war club and equipped with a wooden shield. (Painting by David Rickman (Department of National Defence PMRC-92-605)).

As far as we know, the Norse (Vikings) were the first Europeans to reach North America, sailing from their settlements in Iceland and Greenland. The Viking sagas relate that after several exploratory trips along the coast of Newfoundland and Labrador, a small settlement was established circa 1003 or 1004 in ‘Vinland’ (somewhere along the north-eastern coast). The expedition that founded the settlement at Leifsbudir (now L’Anse-aux-Meadows) near the Burin Peninsula consisted of about 65 people as well as domestic animals. The small community lived mainly by hunting, fishing and picking wild grapes. The first relations between the Vikings and the indigenous population, whom they called skrælings (probably Dorset Inuit or Beothuk), were fairly peaceful, revolving around trading. In the second year, however, some accounts suggest that a conflict broke out between the two groups when the Vikings refused to sell the skrælings weapons. Aboriginal warriors were armed with bows and clubs that would have been as effective as Norse bows and axes in fighting small skirmishes, their canoes were easier to manoeuvre than Viking boats, and they were in a familiar environment. Being too few in number to sustain a war, the Vikings abandoned their settlement after only two years. It is possible that a second settlement was established briefly, at about the same time, near the current site of St. Paul’s Bay, but the documents are contradictory on this point and archaeologists have yet to find any trace of it. The Vikings continued travelling to the Labrador coast up to the mid 14th Century, bringing boatloads of timber back to their barren settlements in Greenland. These expeditions were interrupted in the 1350s, however, when the Inuit drove these European settlers out of Greenland.

In the late 15th Century, English, French, and Portuguese navigators resumed exploration of Canada’s Atlantic coast, seeking a route to Asia and its legendary wealth in spices, silk and precious metals. In 1497, John Cabot took possession of Newfoundland (or Cape Breton Island) for England and in 1534 Jacques Cartier explored the Gulf of St. Lawrence in the name of the King of France. In Chaleur Bay, Cartier’s men met a group of Mi’kmaq, with whom they traded iron goods for furs. They then came to the Gaspé Peninsula, where they planted a cross to take possession of the land and encountered a group of Iroquoians from the Quebec City area (the Stadaconans). Cartier set an unfortunate precedent by kidnapping the two sons of their chief, Donnacona, and taking them back to France.

French Crossbowman

French crossbowman around 1541-42, wearing the white and black livery of the members of the Cartier and Roberval expedition to Canada. (Reconstitution by Michel Pétard (Department of National Defence))

Cartier came back the following year with his two prisoners and, despite resistance from Donnacona and the Stadaconans, travelled up the river as far as Hochelaga (Montreal). Before leaving, he kidnapped Donnacona himself to be his guide on future trips. Since the Aboriginal chief died in captivity, Cartier’s conduct was not conducive to subsequent harmonious relations with the Stadaconans. French attempts to establish a permanent settlement at Quebec City in 1541-1543 failed due to the harsh climate, an outbreak of scurvy and, most importantly, the hostility of the Iroquoian peoples, who killed approximately 35 of the French. Other explorers met with a similar fate. In 1577-1578, for example, the Englishman Martin Frobisher had several skirmishes with the Inuit while navigating along the coast of Baffin Island searching for the Northwest Passage.

The wave of European exploration and colonization was only beginning. In the second half of the 16th Century, Basque, British and French fishers, drawn by the fish stocks of Newfoundland’s Grand Banks, established seasonal outposts on the coasts of Labrador, the Island of Newfoundland, Acadia and the Gulf of St. Lawrence. Alongside their fishing and fish preservation activities, they developed trading relations with the Aboriginal peoples. Copper cauldrons, iron knives, axes and arrowheads, glass beads, mirrors and clothing were traded in exchange for the Aboriginal peoples’ beaver pelts, which were used in Europe to make felt hats.

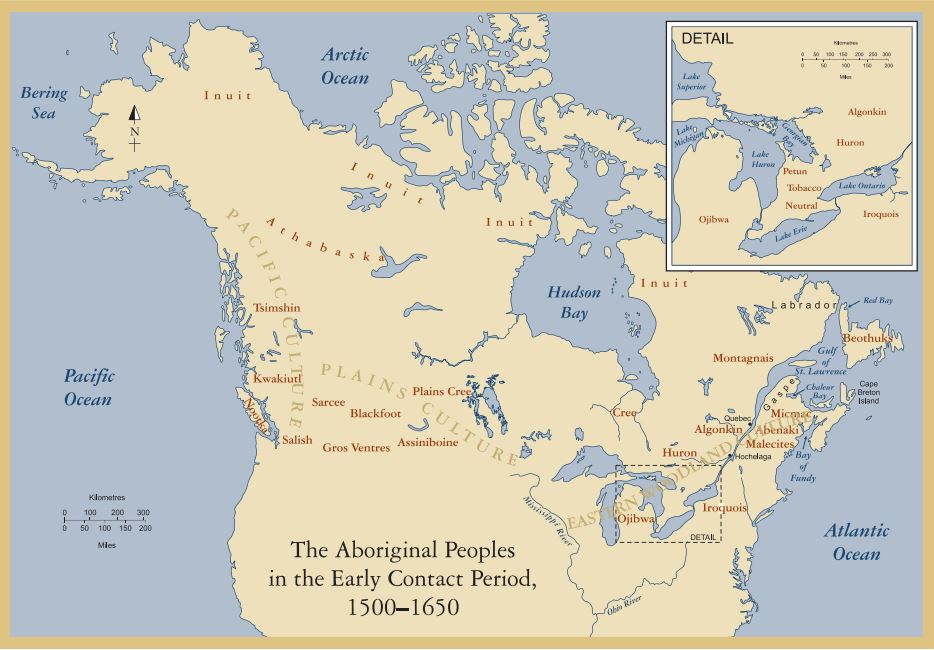

Map: The aborigianl peoples in the early contact period, 1500-1650.

Saint-Malo merchants were soon attracted by this new economy and, in the late 16th Century, men such as François du Pont-Gravé and Pierre du Gua de Monts launched purely commercial expeditions to the region. In 1604, having been granted a crown monopoly on the fur trade, de Monts began trying to establish trading posts in the Bay of Fundy and at Quebec City. He hired the geographer Samuel de Champlain for the purpose. In 1608, Champlain founded the first permanent French settlement in the St. Lawrence valley at Quebec City. Over the next two decades, England, Holland and Sweden also established settlements along the Atlantic coast. For the European powers, the lucrative fur trade and the establishment of settlements gradually superseded the quest for the Northwest Passage.

Alliance-building

French relations with the Aboriginal peoples in the early 17th Century were largely determined by pre-existing intertribal conflicts. At the time Champlain established his settlement at Quebec City, no Aboriginal nation was permanently occupying the St. Lawrence Valley. The Iroquoians that Cartier had encountered some 50 years earlier were no longer there. It would appear they had been decimated by a long war with the Five Nations (the Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga and Seneca) – who occupied the land between the Hudson River and the Genesee River in what is now New York State – and perhaps by epidemics of European origin. In the early 1600s, therefore, the shores of the St. Lawrence were only a summer gathering place for Algonquin, Montagnais and other Algonquian nations. They spent the rest of the year hunting in the interior. These nomadic nations were at war with the Iroquois, who apparently wanted to secure access to the emerging trade network in the St. Lawrence Valley. To establish solid trading relations with the Algonquin speakers surrounding Quebec, Champlain chose to ally himself with them and take sides in the conflict.

In 1603, when he spent the summer in Tadoussac, Champlain formed a trading and military alliance with the Algonquin, Montagnais and Malecite nations. He promised to send forces to help them defeat the Iroquois but also offered to help them make peace with their enemies. Like all administrators of New France after him, Champlain believed that establishing a general peace among all the Aboriginal peoples was the best way to promote trade and to peacefully settle the land. The Aboriginal response was clear: while they were prepared for the French to ‘people their land,’ they refused to make peace with the Iroquois and preferred that Champlain make war on their enemies. When he returned in 1608, Champlain renewed the alliance and was soon called upon to honour his promises and become involved in his allies’ war. In 1609, 1610 and 1615, he took part in raids against the Iroquois, along with several French soldiers and Algonquin, Montagnais and Huron warriors. Then, in 1616, missionaries and soldiers were sent to Huronia to establish the first mission there and, most importantly, to cement the Franco-Huron alliance.

During the following 15 years, there were no major clashes between the Iroquois and the allies of the French, though occasional raids still took place. The two sides concluded a peace treaty in 1624. During the lull in the fighting, a flourishing trade network developed in New France, in which the Huron, an Iroquoian confederacy concentrated in the area between Georgian Bay and Lake Simcoe in what is now the province of Ontario, played a vital role as middlemen. Because of their strategic geographic location, the Huron were able to funnel towards Quebec City large quantities of furs that they obtained from other nations in the Great Lakes region.

Meanwhile, in 1609, the Dutch began frequenting the shores of the Hudson River. In 1614, they established a trading post called Fort Orange near Iroquois territory, on the current site of the city of Albany. This development played a significant role in the period of relative calm between the Iroquois and the allies of the French, which lasted from 1615 until about 1630, since the Iroquois were busy fighting the Mohegan, an Algonquian nation that was blocking their access to the Dutch trading posts. Once the Mohegan had been driven from their land, the Iroquois made an alliance with the Dutch giving them direct access to European goods. Two major networks of alliances were now established in north-eastern North America and they would govern military relations for the next 150 years.

The Iroquois Wars

In 1629, the Kirke brothers, who were in the service of England, drove the French out of the St. Lawrence Valley. When they retook possession of New France in 1632, the French found that the war between their old allies and the Iroquois had resumed. However, the situation had changed and it was now the Iroquois who were carrying out raids in the valley of the St. Lawrence. It is difficult to determine the precise causes of these ‘Iroquois Wars,’ which flared repeatedly for much of the next 70 years. It appears that economic, cultural and political factors were all involved.

The fur trade was likely a factor in these conflicts. The territory of the Iroquois Five Nations was not particularly rich in beaver, and their geographic location not ideally suited to capitalise on the burgeoning fur trade. This argument has been articulated by a number of scholars beginning with Francis Parkman and elaborated upon by Harold Innis and George Hunt. Essentially they believed the Iroquois were seeking, by means of war, to increase their sources of supply of pelts so they could obtain European goods, and eliminate their rivals to gain dominance of the trade. To secure these goals, three courses of action were available to them: to become middlemen between the Europeans and Aboriginal nations, to conquer new hunting grounds, or to lie in wait along the riverbanks in order to ambush and rob Aboriginal convoys travelling to the French trading posts. Under this interpretation, the Iroquois Wars came to be understood as the ‘Beaver Wars.’

More recently, scholars such as Daniel Richter, George Sioui and José António Brandão have sought to challenge or refine the Beaver War interpretation, arguing for the importance of the mourning war as a collective motivation underlying Iroquois aggression. The introduction of infectious diseases against which the indigenous peoples had no antibodies powerfully affected many Aboriginal societies, including the Iroquois. Estimates suggest that up to one half of the population of the St. Lawrence Valley and the Great Lakes region was decimated by epidemics of European origin in the first half of the 17th Century alone. In response to this unprecedented wave of deaths, it seems plausible that the Iroquois engaged in a massively amplified ‘mourning wars’ in order to replace their dead, sometimes capturing more than a thousand captives in a single raid.

The Iroquois’ desire to capture entire groups was apparently motivated not only by the need to replace their dead, but also by broader political goals: hegemonic ambitions, the quest for power over other nations. These ambitions are clearly expressed in the myth of the foundation of the Iroquois League, which was essentially its Constitution. It stipulated that, in addition to establishing an alliance among the Five Nations, the League would extend peace, by diplomacy or by force, to all the nations neighbouring on the land of the Iroquois. A vast alliance would be developed, within which the Iroquois saw themselves exercising a degree of authority by virtue of their key role as mediators among the other nations. The Iroquois frequently asserted throughout the 17th Century that they hoped to become ‘one people’ with all the nations in north-eastern America, contemporary European writers noted. For example, Denis Raudot, Intendant of New France, made the following observations about the Iroquois policy in the early 18th Century:

They devoted all their energies to inducing the other nations to surrender and give themselves to them. They sent them presents and the most skilful people of their nation to lecture them and tell them that if they did not give themselves up, they would be unable to avoid destruction, and those who fell into their hands would suffer the cruellest torments; but if on the contrary they wished to surrender and disperse to their cabins, they would become the masters of other men.

It would be futile to attempt to single out, from among these factors, a sole cause for the Iroquois wars. It is highly probable that all of these factors played a decisive role at one point or another and to varying degrees. It is clear, however, that the wars waged by the Iroquois against the Aboriginal nations of the St. Lawrence Valley and the Great Lakes region were a serious threat to the fur trade in New France and to attempts by the French authorities to establish a general peace among the Aboriginal peoples. The French therefore became increasingly involved in the conflict.

When he returned to the colony in 1632, Champlain decided to settle the Iroquois problem once and for all by destroying the League of Five Nations. He renewed his alliance with the Algonquin, the Montagnais and the Huron and again pledged to support them against their enemies. However, the colony had serious financial problems at the time and Champlain was never able to get France to provide the soldiers he needed to carry out his plans. He had to settle for supplying his allies with weaponry such as iron arrowheads and knives. The economic difficulties continued after Champlain’s death in 1635 and the French were never able to properly support their allies until the 1660s.

Despite the modest support from the French, the allies managed to continue the war and to inflict heavy losses on the Iroquois up to the late 1630s. In 1636, for example, Algonquin warriors organized a raid into Mohawk territory during which they killed 28 Iroquois and captured a number of others, five of whom were brought back alive to Quebec City to be tortured. In 1638, the Huron also succeeded in capturing more than a hundred Iroquois and killing many others.

In the 1640s, the tide gradually turned against the Franco-Aboriginal alliance. For one thing, the Iroquois changed their military tactics, as a Jesuit account testifies:

In previous years, the Iroquois came in fairly large contingents at certain times during the summer and then left the river free, but this year they have changed their purpose and divided into small detachments of 20, 30, 50 or 100 at most, along all the passages and places on the river, and when one group leaves another takes its place. They are small, well-armed contingents that are constantly moving so as to occupy the entire river and prepare ambushes everywhere, emerging unexpectedly and attacking Montagnais, Algonquin, Huron and French indiscriminately.

The Iroquois also sought to split the Franco-Aboriginal alliance and tried to negotiate a separate peace with the French excluding the other Aboriginal nations. Two attempts were made, one in 1641 and the other in 1645. Though these efforts were in direct contradiction with the French desire to establish a general peace among the Aboriginal nations, they ultimately led to a Franco-Iroquois treaty, which was ratified in 1645. In a secret agreement with the French, the Iroquois succeeded in excluding from the treaty all Aboriginal peoples who had not converted to Christianity. While the peace lasted only a year, it did have the effect of undermining the Franco-Aboriginal alliance.

The decisive factor in the sudden shift in the balance of power between the Iroquois and the allies of the French was that the Iroquois had obtained firearms. In 1639, the Dutch ended the monopoly on the fur trade at Fort Orange. Merchants therefore flocked to the trading post and, despite repeated government prohibitions, began selling firearms to the Iroquois. By 1643, the Mohawk were equipped with nearly 300 muskets, while the Huron, Montagnais and Algonquin had very few because the French, fearing that the weapons would some day be used against them, restricted the sale of firearms to Aboriginal people who agreed to convert to Catholicism. The Jesuits reported that ‘since they have no arquebuses, the Huron, if they are encountered [by the Iroquois], as commonly occurs, have no defence other than flight, and if they are taken captive they allow themselves to be tied and massacred like sheep.’

Better armed than their enemies, the Iroquois undertook the systematic destruction of Huronia in the late 1640s. In 1647 and subsequent years, several Huron villages were moved following repeated Iroquois attacks. In 1648, the village of Saint-Joseph was overwhelmed with a loss of some 700 Huron, mostly taken captive, according to the Jesuits. In the following year, nearly a thousand Iroquois attacked and destroyed the villages of Saint-Louis and Saint-Ignace, burning Gabriel Lallemand and Jean de Brébeuf, the two Jesuits in charge of the missions, on the spot. According to accounts by survivors, the Iroquois won an easy victory at Saint-Ignace:

The enemy burst in at the break of day, but so secretly and suddenly that they were masters of the place before we could put up a defence, since everyone was sound asleep and had no chance to realize what was occurring. Therefore, the town was taken almost without resistance, with only 10 Iroquois killed, and all the men, women and children were either massacred on the spot or taken captive and doomed to cruelty more terrible than death.

These repeated hammer blows by the Iroquois, coupled with divisions within Huron society and despair of epidemic diseases, shattered Huron morale. The remaining population decided to abandon the land, burn their villages and disperse. Many decided to surrender and join the League of Five Nations, others took refuge among their Petun, Neutral and Erie neighbours, while still others fled to St. Joseph Island in Georgian Bay. Unfortunately, the island was too small to provide for the needs of the thousands of Huron who took refuge there, and during the following winter several hundred died in a major famine. In 1650, a group of several hundred Christian Huron decided to settle at Quebec City, in the French colony, while the rest of the nation dispersed westward as refugees. The former group originally settled on Île d’Orléans and moved frequently in the following years, finally settling at Lorette (Wendake) in the 1690s.

The Huron were not the only indigenous peoples to feel the power of the Iroquois in the wars that followed. In 1649, the Petun, a nation living south of Georgian Bay, which had supported the Huron against the Iroquois and sheltered many of their refugees, were also attacked. The village of Saint-Jean, where several Jesuits had been living for about 10 years, was besieged and destroyed. Rather than suffer the same fate, the other eight villages in the confederacy decided to flee westward and found refuge on the shores of Green Bay, west of Lake Michigan. The Iroquois then turned their assaults against the Neutral, who as their name suggests had remained neutral in the conflict between the Huron and the Iroquois. Armies of 1,200 to 1,500 Iroquois warriors destroyed one village in the fall of 1650 and then another in the following winter. Like the Petun, the Neutral survivors preferred to disperse westward rather than risk being massacred and tortured by the Iroquois. Between 1653 and 1657, the Iroquois attacked the Erie, further south, who they also dispersed. Even in the St. Lawrence Valley, the Iroquois achieved significant success. In 1651, the Jesuits reported that Iroquois warriors had travelled up the St. Maurice River and attacked the Attikamekw in their own territory, which had appeared to be virtually inaccessible, and destroyed entire encampments.

The string of Iroquois victories had serious consequences for New France. In military terms, the French found themselves totally isolated: not only were they deprived of the assistance of the Huron — who had previously exerted constant pressure on the western part of Iroquois territory — but also that of their Algonquian allies in the Laurentian region (Algonquin, Attikamekw and Montagnais), who no longer dared frequent the colony for fear of being ambushed by the Iroquois. The defenceless French settlements became a favourite target of the Iroquois. Between 1650 and 1653, they struck everywhere between Montreal and Quebec City, sparing neither settlers who ventured into the woods to hunt nor those working the fields. ‘The Iroquois have wreaked such havoc in these quarters that for a time we believed we would have to return to France,’ wrote Sister Marie de l’Incarnation in 1650. The colony was also in a precarious position economically. Since Aboriginal traders no longer dared travel to the St. Lawrence Valley, the fur returns declined sharply after 1650. Without the revenues from the trade, which by itself had been almost enough to provide for the colony’s needs, New France was no longer able to defend itself against Iroquois incursions.

In 1653, the Iroquois took advantage of the favourable circumstances to negotiate a peace with the French on their own terms. They demanded that French soldiers move into their villages to defend them against their enemies and that the Jesuits build a residence within their lands. As a result, a French outpost was established in 1655 at Onondaga, the capital of the Iroquois League. For three years, peace reigned between the French and the Iroquois. But in 1658, the French changed their policy towards the Five Nations, abandoned their new mission and returned to the colony, determined to confront the Iroquois and impose a peace, by force of arms if necessary.

When Louis XIV ascended to the throne of France, the situation in New France changed considerably. In 1663, the young king decided to take matters in hand, declared New France a crown colony and sent the Carignan-Salières Regiment, composed of 1,500 regular soldiers under the command of Alexandre de Prouville, Marquis de Tracy, to secure peace with the Iroquois. They landed at Quebec City in the summer of 1665 and began building a series of forts on the Richelieu River, the Iroquois’ main route to the St. Lawrence Valley. They also organized two major expeditions against the Iroquois. The first, consisting of 300 men from the regiment and 200 volunteers from the French colonies, left Quebec City on 9 January 1666. The results were disastrous. The soldiers were ill equipped for a winter campaign: most had no snowshoes or did not know how to use them, and were poorly dressed for ‘a cold that greatly exceeds the severity of the harshest European winter.’ In addition, the army set out hastily, without waiting for its Algonquin guides, who arrived late at the meeting place. This mistake was fatal for the troops, who had to take unknown routes and constantly went off course. The soldiers quickly lost their way. After wandering around the Lake Champlain area for three weeks, they finally arrived at the Dutch village of Schenectady and were happy to receive assistance from the local merchants. During the five-week expedition, nearly 400 soldiers died of hypothermia, hunger and disease.

Canadian on snowshoes

Canadian on snowshoes going to war over the snow at the end of the 17th century. This is the only known contemporary illustration of a Canadian militiaman. (Library and Archives Canada (C-113193))

After this catastrophic campaign, the French realized how dependent they were on their Aboriginal allies to wage war in North America. In October 1666, a second expedition was launched against Iroquois villages, and this time a hundred Aboriginal men were present along with 600 French soldiers and 600 French-Canadian volunteers. These Aboriginal allies served as guides and also hunted to provide provisions for the troops. This expedition, better prepared than the first, finally reached the Mohawk villages after marching for two weeks. To the dismay of the French, however, the villages were deserted. The Mohawk opted to retreat rather than confront the large French army. The French had to content themselves with setting fire to their villages and crops, before returning to Quebec City.

The French had been engaged in peace talks with four of the Iroquois Five Nations (the Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga and Seneca) since 1663. The arrival of the Carignan-Salières Regiment spurred the negotiations and treaties were ratified by each of the four nations in 1665 and 1666. But the outright refusal of the Mohawk to take part in the discussions opened by the rest of the League prompted the French to continue their incursions into Mohawk territory. When the Mohawk realized that the French were capable of attacking them on their own lands, in their villages, they decided to yield and finally ratified the peace treaty in Quebec City in July 1667. At the time, the Iroquois were at war with the Andaste, an Iroquoian nation in Pennsylvania. Signing the treaty with the French meant they would not have to fight on two fronts at once.

The Treaty of 1667: Rebuilding the Franco-Aboriginal alliance

The Franco-Iroquois peace lasted 15 years. It was a period of growth for New France. The French succeeded in re-establishing their system of alliances in the Great Lakes region. Since the destruction of Huronia by the Iroquois in 1650, only a few intrepid coureurs de bois such as Pierre-Esprit Radisson and Médart Chouard des Groseillers had dared venture into the region to seek new trading partners. After the 1667 treaty, the route to the Great Lakes became much safer and it was not long before French travellers appeared in the region. The Jesuits also set out to conquer the area, looking for new souls to convert. Beginning in 1665, they established a series of missions in the ‘Pays d’en Haut.’ The first was called Saint-Esprit and was located at Chagouamigon on Lake Superior.

The nations the French encountered around Lake Superior and Lake Michigan were almost all at war with the Iroquois Five Nations, and occasionally each other. Most of them had fled their lands in the 1650s and 1660s and had taken refuge from the Iroquois further west. They welcomed the arrival of the French as an external arbiter, who had powerful weapons and could protect them. When the adventurer Cavelier de La Salle visited the Potawatomi for the first time in the 1670s, they expressed their reasons for forming an alliance with the French in these words: ‘You are one of the first spirits for you make iron. You are the one who must rule and protect all men. Praised be the Sun that lights you and has brought you to our land.’

For their part, the French found among Aboriginal peoples excellent trading partners and new allies in the defence of the colony. In keeping with their policy of mediation, they sought to establish peace among all these nations (often described as enemies) and to form a commercial and military alliance with them. To encourage these nations to fight the Iroquois, the French began giving them presents, ingratiating them though the indigenous system of gift-giving diplomacy. The French did not make the same mistake they had with the Huron, and distributed firearms liberally as gifts to both confirm their alliance and arm their new allies. The historian Bacqueville de La Potherie, who stayed in the colony at the end of the 17th Century, described the formation of the Franco-Aboriginal alliance: ‘The French … had penetrated into their lands imperceptibly … the union was cemented on both sides; we took their common interests and they declared themselves our friends; we supported them in their wars and they declared themselves in our favour.’

The prolonged contact between the French and Aboriginal peoples in the region had a profound impact on French-Canadian society, particularly on military practices. In the early 1650s, the French settlers began adopting their allies’ guerrilla tactics to counter more frequent Iroquois attacks. When they started making regular trips to the Great Lakes region and trading extensively with the Aboriginal peoples, the settlers refined those tactics. According to historian Arnauld Balvay, in the 1680s the French-Canadians ‘began wearing moccasins, travelled light in order to be more mobile, and fought running battles alongside their Aboriginal allies. As a result of this intermixture, by the end of the 17th Century the Canadians had become capable practitioners of the art of la petite guerre.’ When the British attacked Quebec City in 1690, they were beaten back by an outnumbered French-Canadian militia that, according to a contemporary chronicler, was able to prevail by using guerrilla tactics:

[The French-Canadians] were divided into a number of small platoons and attacked with little order, in the manner of the Savages, this large body [the British] which was in tight ranks. They made one battalion give way and forced it to fall back. The shooting lasted more than an hour as our people flew constantly about the enemy, from tree to tree, and so the furious volleys aimed at them disturbed them little, whereas they fired accurately on people who were all in one body.

But we should not give credence to the romanticized image — propagated by some 17th and 18th Century chroniclers and embraced by more recent historians — of the French-Canadian militiamen as fierce warriors, always ready to go off to battle as the mainstay of the French forces in North America. Historian Jay Cassel has shown that the French-Canadian militia were often poorly armed and, aside from a small elite, took part in French military campaigns only infrequently and in small numbers. Their importance declined considerably in the 18th Century, after the creation of the les Compagnies franches de la Marine or Troupes de la Marine, a military corps set up by the French Ministry of the Navy and Colonies in 1684. Like the militiamen, the Troupes de la Marine quickly adapted to guerrilla warfare, which they learned from and practiced alongside their Aboriginal allies when the terrain was suitable.

The Franco-Aboriginal alliance also expanded in the St. Lawrence Valley. In the hope of cementing the peace, the Franco-Iroquois treaty of 1667 included a provision for the Jesuits to set up missions in Iroquois territory. In exchange, the Iroquois promised to send several families to settle in the St. Lawrence Valley. Groups of Iroquois began emigrating to La Prairie-de-La Magdelaine, a Jesuit mission not far from Montreal on the south shore of the St. Lawrence River, in 1667. The pace of emigration picked up after 1675. Most were former Huron who the Iroquois had taken captive around 1650 and did not wish to continue living under their conquerors. Others were newly converted Catholics who wanted to escape the tensions created by the practice of their new religion and the ‘disorders’ produced by alcohol. The French encouraged the migration, both to weaken the Iroquois and to make the colony more secure:

Mr. De Courcelle [the Governor], who was informed of everything, was pleased to see the Iroquois converts planning to settle among the French. He understood that as their numbers increased they might form a tribe and, with time, could become a barrier against the [Iroquois] districts themselves if war should break out.

Since the land around Prairie-de-La-Magdelaine was unsuitable for growing corn, the Iroquois began moving in the late 1670s and divided into two groups: one followed the Jesuits to Sault Saint-Louis (Kanawake) and the other went to the Sulpician mission of La Montagne (near Mount Royal). The La Montagne mission was moved to Sault-au-Récollet in 1697 and then to the Lake of Two Mountains (Kanesatake) in 1721, where it remains to this day. These ‘mission Iroquois’ became strategic allies of the French, along with the Huron in the Quebec City area and the Abenaki, who began arriving in the Trois-Rivières area in 1675.

Other groups also reorganized their network of alliances after the Franco-Iroquois treaty of 1667. When the British seized control of New Holland in 1664, the Iroquois were cut off from their political and commercial allies. In 1677, when the Iroquois experienced serious difficulties in their war with the Andaste, they formed an alliance with the British similar to their previous pact with the Dutch. Known as the ‘Covenant Chain,’ it called for mutual assistance by the two allies in the event of war. It also guaranteed the Iroquois preferred access to the British market and a role as intermediaries in Anglo-Aboriginal relations.

Abenaki Wars, 1675-1678 and 1687-1697

While the Iroquois Wars were shaping the development of the French colony in the St. Lawrence Valley and the Great Lakes region, another war was being waged between the Mi’kmaq and the Abenaki in Acadia. Champlain built the first French settlement in the Maritimes in 1604 on Île Sainte-Croix. The following year, it was moved to Port-Royal (Annapolis Royal), which became the centre of the Acadian colony. At the time, the Mi’kmaq, an Algonquian nation that had hostile relations with the Abenaki who lived in neighbouring Maine and Massachusetts, inhabited the region. By 1604, the French had established trading relations with the Mi’kmaq, who made use of French weaponry such as metal arrowheads, swords and even firearms to fight the Abenaki.

In the 1620s, however, the geopolitical situation in Acadia changed quickly. After the 1624 treaty between the Iroquois and the nations of the St. Lawrence Valley, the Mi’kmaq and the Abenaki became the targets of Iroquois raids. This development helped reduce tensions between the Mi’kmaq and the Abenaki, and it induced the Abenaki to open negotiations with the French for a commercial and military alliance. The first overture was made in 1629, when an Abenaki delegate travelled to Quebec City to seek Champlain’s aid against the Iroquois and propose a close friendship between their nations. Since Champlain was unable to provide the Abenaki with concrete assistance at that time, nothing came of the proposed alliance until 1651, when the Jesuit Gabriel Druillette visited the Abenaki to enlist them into a common front against the Iroquois.

In 1654, Acadia fell to the British. The French did not recover the territory until 1670, and they established a new post in Abenaki territory at the mouth of the Penobscot River (now Castine, Maine). In the following years, the Jesuits and the Récollets founded a number of missions among the Abenaki and the Mi’kmaq, while a number of the small and largely male population of French settlers married Aboriginal women. The Franco-Abenaki alliance, which had been shaky up to that point, quickly became firmer.

The Baron de Saint-Castin exemplified the close alliance that developed between the French and the Abenaki during this period. A young soldier who came to Canada with the Carignan-Salières Regiment, Jean-Vincent d’Abadie de Saint-Castin became the lover of a Aboriginal woman named Pidianske, who was the daughter of Madockawando, an important Abenaki chief of the Penobscot nation. Initially, relations between Saint-Castin and the Abenaki were of a purely commercial nature. But after a few years, the Baron decided to settle among the Abenaki, where he acquired considerable political power.

In 1675, King Philip’s War (in reference to the English name of Metacom, the Wampanoeg chief against whom the Plymouth Puritans initiated hostilities) broke out between the British colonies of New England and most of the Algonquin nations on the east coast of North America, including the Abenaki and the Mi’kmaq. The cause of the war was the expansion of the British colonies into Aboriginal lands. It ended with the destruction of most of the Aboriginal nations in Massachusetts and Connecticut, and the exodus of thousands of Abenaki. Some took refuge at Pentagoët with Saint-Castin and his allies, while others travelled to the St. Lawrence Valley and joined members of their community who had withdrawn to the Jesuit mission in Sillery in the 1660s, after the Iroquois wars. The Jesuits recorded the arrival of a large number of refugees:

When the war that the Abenaki had with the English began, many of them decided to withdraw to the land inhabited by the French …. Two nations principally, namely those called the Sokoki and the Abenaki, carried out this plan and set out at the beginning of summer in the year 1675. The Sokoki headed for Trois-Rivières, where they settled, and the Abenaki … withdrew to this place called Sillery.

Following King Philip’s War, the British began encroaching on Abenaki and Mi’kmaq land. Settlers from New England started fishing off the Acadian coast, seized Aboriginal hunting grounds, and built forts there for defence. In 1687, another war – often called King William’s War – resumed between the British and Aboriginal groups. During this conflict, the French supplied the Abenaki and the Mi’kmaq with weapons to fight the British, supported them in some battles, and continued to take in refugees fleeing the war. The population of Sillery grew so rapidly that the mission soon became overcrowded. One Abenaki group, primarily from Maine, settled at Sault de la Chaudière near Quebec City, and then moved again to the mouth of the St. François River (Odanak) in 1700. Abenaki from Vermont (known as the Sokoki) chose to relocate their village to Bécancour (Wolinak) on the south shore of the St. Lawrence River. Like the Iroquois missions, these Abenaki villages served French policy. Father Charlevoix reported that ‘the Governor General’s intention, in creating this settlement, was to fashion a barrier against the Iroquois, in case those Savages should be persuaded by the English to resume the war.’ They also served Abenaki interests, providing security from their enemies to the south while allowing Abenaki warriors to range freely against English settlers.

In Acadia, Aboriginal hostility to the British persisted until the end of the French Regime in 1760 and was at the core of the Franco-Aboriginal alliance that lasted until that date. In 1697, when the British were seeking peace with the Abenaki, the latter clearly expressed their opposition to British colonial expansion and their attachment to the French. The Abenaki chief demanded, as a condition for peace,

- That he [the British Governor] begin by withdrawing the English from their land forever.

- That they [the Abenaki] did not see on what grounds he claimed to be their master, that neither he nor any of his predecessors had ever been, that they had given themselves to the King of France willingly and without being forced to do so, and they would never take orders from anyone other than him and his generals.

- That they would never allow the English to have habitations on their lands and they had granted this permission to the French alone.

Resumption of the Iroquois Wars: 1684-1701

After a 15-year lull, hostilities between the French and the Iroquois broke out again in the 1680s, when the Seneca (the League’s westernmost nation) began robbing French coureurs de bois and attacking the Illinois, a new ally of the French. It is likely that, as in the 1640s, the Iroquois resumed the war out of a desire to take captives and to increase their supply of furs. They were particularly irritated by the French policy of mediation, however, which ran directly counter to Iroquois hegemonic ambitions. An Iroquois chief’s comments, reported by the Jesuits in 1670, expressed the extent of their frustration:

They ask, who does Onontio [the French Governor] take us for? He is angry that we are going to war: he wants us to lay down our hatchets and leave his allies in peace. Who are his allies? How does he expect us to recognize them, when he claims to take under his protection all the peoples discovered by those who go to spread the word of God across all these lands, and when every day, according to what we hear from our people who escape the cruel fires, they make new discoveries and enter into nations that have never been anything but enemies to us?

Meanwhile, thanks to their new alliance with the British, the Iroquois had vanquished the Andaste in the late 1670s. With that pressure removed and with the support of the British, the Iroquois were now able to resume their raids against the French and their allies.

In this new phase of the conflict, the Aboriginal allies — those living at missions in the St. Lawrence Valley and those in the Great Lakes region — played an important role. Among other things, they took part in many expeditions organized by the French against Iroquois villages. In 1684, when the Governor, Le Febvre de La Barre, launched an attack against the Seneca, 378 “mission Indian” warriors, including Iroquois, Abenaki, Algonquin, Nipissing and Huron men from Lorette, accompanied his 680-man contingent. About 1,000 Aboriginal warriors from the Great Lakes region were expected to join the expedition, along with a hundred French coureurs de bois. The expedition was a failure in the end: suffering from fever and short of provisions, the French troops never reached Iroquois territory. La Barre was forced to sign a peace treaty with the Iroquois that was ‘shameful’ for New France and he abandoned his Illinois allies.

After this failure, La Barre was recalled to France. His successor, René Brisay de Denonville, a professional soldier, launched an attack against the Seneca in 1687, and once again Aboriginal peoples played an important role in the campaign. This time, at least 300 “mission Indians” and another 400 from the Great Lakes region marched alongside 1,800 French soldiers and militiamen. According to the Baron de Lahontan, who took part in the expedition, the allied warriors came to the rescue of the French troops when they fell into an Iroquois ambush:

Our battalions were quickly split into small groups, which ran in all directions in a disorderly jumble, not knowing where they were going. We shot at each other instead of shooting at the Iroquois.… Finally, we were so confused that the enemy fell upon us with clubs, when our Savages, gathered together, pushed them back and pursued them so zealously to their villages that they killed more than 80, whose heads they brought back, not counting the wounded who escaped.

The Denonville expedition, like that of the Marquis de Tracy two decades earlier, was only a half-victory for the French. When they reached the Seneca, the French troops found the villages abandoned: ‘The only benefit we obtained from this great enterprise was that we laid waste the entire countryside, which caused a great famine among the Iroquois and caused many of them to perish subsequently.’ It was clearer to the French than ever before that they needed their Aboriginal partners to wage war in the forests of North America. ‘Since we cannot destroy the Iroquois with our forces alone,’ wrote Lahontan, ‘we are absolutely forced to have recourse to our allied Savages.’

The Iroquois, who had avoided directly attacking the French colony to that point, responded to the Denonville expedition by launching a large-scale raid against the village of Lachine, close to Montreal, on 5 August 1689. About 1,500 warriors took the French inhabitants by surprise at dawn, while they were asleep. The casualty figures are contradictory: from 200 French killed and 120 taken prisoner, to conservative estimates of 24 French dead and 70 prisoners. The Iroquois also set fire to barns and homes before withdrawing to torture and burn at the stake some of their captives. In the following years, numerous small Iroquois war parties invaded New France, armed and encouraged by the British, who were at war with the French at the time. The Iroquois struck everywhere — La Chesnaye, Île Jésus, Verchères — killing or capturing the inhabitants.

In the hope of putting an end to the raids, the French struck back by launching more military expeditions into Iroquois territory. In January 1693, Huron from Lorette, Abenaki from Sault de la Chaudière, and Algonquin and Sokoki from Trois-Rivières, accompanied French soldiers in a raid against the Mohawk. For the first time, the French did not find deserted villages. They succeeded in taking three villages by surprise and capturing more than 300 prisoners. This victory revealed that they had begun to master guerrilla tactics. In 1696, 500 Aboriginal warriors and approximately 1,600 French soldiers and Canadian militiamen mounted a last expedition against Onondaga and Oneida villages. The Comte de Frontenac, who was 74 years old and had to be carried through the woods on a chair, led them. Once again, the Iroquois withdrew before the arrival of the army and the French had to content themselves with destroying the crops and the villages, a practice that had become almost a ritual.

While some Aboriginal nations supported the French against the Iroquois, they were not unconditional allies and set limits on their involvement in the war. The Iroquois living at Sault and La Montagne were generally disinclined to kill their Five Nations cousins, with whom they preserved cordial relations. After the 1693 expedition against the Mohawk villages, for example, the French demanded that the 300 prisoners be put to death, so they should not become a burden on the journey home. But the several Iroquois from Sault Saint-Louis who were present were fiercely opposed to the plan:

The Savages argued that they were responsible for the prisoners and they would never consent to slay them, although they had promised to do so … when they left Montreal … These sorts of nations do not govern themselves as others do. They readily promise what is asked of them, and decide later whether to do it according to what their interests (which they do not always know) or their whims suggest.

The “mission” Iroquois proved to be much more useful as diplomatic intermediaries between the French and the Five Nations, carrying peace proposals back and forth.

The Aboriginal peoples in the Great Lakes region fought not only because the Iroquois were their traditional enemies. They also served as allies because the French sustained their relationship through generous annual distributions of gifts. According to the French officer Gédéon de Catalogne, ‘We sent large presents to all the Odahwah nations to induce them to harass the Iroquois and divert them from their course.’ When the presents were lacking, these nations, who were increasingly dependent on these gifts for a steady supply of shot and powder, were quite dissatisfied and the French western alliance faltered. In 1697, the Potawatomi chief Onanguice complained:

that we generally promised them [the Aboriginal peoples] much more than we apparently intended to give them; that we had often assured them that we would not leave them short of munitions and we had supplied them with none for more than a year; that the English did not deal in this manner with the Iroquois; and if we continued abandoning them in this way, they would no longer be seen at Montreal.

These were not empty threats, for the Aboriginal peoples of the Great Lakes region conducted ongoing secret negotiations with the Iroquois on ending the war and joining their Covenant Chain. For example, in 1696 Canadian authorities contended that such negotiations were under way between the Iroquois, the Huron and possibly other nations:

Most of the nations [in the Great Lakes region], at least the Huron, tired of attending to our interests, welcomed the Iroquois delegates. The policy [of the Iroquois], who were not dispirited by the obstacles they encountered in all their attempts, was so grand that they skilfully insinuated themselves into the minds of many of our Allies, who had until then shown great concern for our interests. They began holding their Councils in secret without informing the Commander of Michilimakinak, and they accepted the Iroquois’ necklaces.

Despite these diplomatic manoeuvrings, the western allies played an important role in the Franco-Iroquois war. According to historian Gilles Havard, they were the main factor in the defeat of the Iroquois in the late 1690s. They conducted a flurry of raids against the Iroquois in parties generally consisting of dozens or even a hundred warriors. The colonial authorities reported that in 1692 alone, ‘all the Great Lakes nations … had more than 800 men detached in small parties that were at the gates of the Iroquois villages every day or harassed them on their hunting grounds.’ These tactics ‘disturbed them more than can be said.’ The historian Bacqueville de La Potherie, who was in the colony in the late 17th Century, wrote of the nations of the Great Lakes region:

When these nations abandon our interests it will be a catastrophe for Canada. They are its support and shield. They are the ones that rein in the Iroquois on all the hunting expeditions they must make away from their homes in order to survive. Moreover, they carry iron and fire into the heart of Iroquois country.

As a result of the raids by the Great Lakes nations, alongside disastrous epidemics, the Iroquois population fell by half between 1689 and 1697. In addition, when the Treaty of Ryswick ended the war between the French and the British in 1697, the Iroquois lost the support of their British allies in their war against New France. Isolated, weakened and alarmed by the growing military might of the French, who had carried the war to most of their villages, the Iroquois signed the Great Peace of Montreal on 4 August 1701. Historians long argued that the Iroquois were forced to accept conditions dictated by the French in 1701. Some writers, such as Francis Jennings and William Eccles, have even described the Great Peace as an Iroquois surrender. But in fact the treaty of 1701 was essentially a compromise between the French and the Iroquois. In the negotiations that led to the signing of the treaty, which lasted more than five years, the Iroquois wrested major concessions from the French. Among other things, they demanded that the French Governor pledge to defend them if the Aboriginal peoples from the Great Lakes region continued their raids against them. The Governor agreed, specifying that before committing troops to a conflict he would seek to obtain reasonable satisfaction for the victim of the attack by diplomatic means. In exchange for this undertaking, the Iroquois promised to remain neutral in any French-British conflict.

Fox Wars, 1712-1714 and 1730-1735

Aboriginal wars continued to play a decisive role in the military history of New France, even during the periods of peace between France and the British, into the 18th Century. The Fox War is a good example of a conflict that helped both reaffirm and threaten the Franco-Aboriginal alliance.

Expedition against the Iroquois, 1695

Count Frontenac, Governor of New France still active at the age of 74, is seen here carried in expedition he led against the Iroquois in 1695. (Library and Archives Canada (C-6430))

The Fox lived southeast of Lake Michigan on the river that still bears their name. They came into contact with the French in the late 1660s. At the time, the Fox nation had hostile relations with many allies of the French. For some 40 years, however, influential figures, such as the well-known coureur de bois and fort commander Nicolas Perrot, were able to step in between these nations and keep the peace. In 1710, the Fox moved their village close to the French fort of Detroit, where a heterogeneous Aboriginal community was already gathered. Ancient quarrels then resurfaced and were aggravated by the arrogant attitude of the Fox towards their new neighbours. Tensions between the different nations quickly mounted and in 1712 a group of Odahwah attacked the Mascouten, close allies of the Fox. The Mascouten took refuge at Detroit among the Fox, who defended them and mounted a counter-attack against the Odahwah. Most of the nations in the region (Huron, Miami, Illinois, Potawatomi …) joined forces with the Odahwah and laid siege to the Fox and the Mascouten. The latter asked the French commander at Detroit for assistance several times but he refused. During the 19-day siege, nearly 1,000 Fox and Mascouten were killed or taken prisoner by the allies.

In the following years, France’s Aboriginal allies frequently asked the Governor, Philippe de Rigaud de Vaudreuil, to send soldiers westward to help them ‘destroy’ the Fox. Vaudreuil, whose people were at war with the British at the time, initially tried to mediate and to alleviate the conflict, suggesting to his allies that ‘if … the Fox ask you for peace, I believe it would be more fitting to grant it than to wage a war that may last a long time and cause much pain and grief in your villages.’ The Fox, however, soon resumed their raids against the allies, particularly the Illinois, and against the French coureurs de bois. The Canadian authorities were therefore forced to send troops west in the hope of overawing the recalcitrant Fox. In 1716, some 450 French soldiers and 350 Aboriginal warriors led by Louis Laporte de Louvigny, an officer of the Troupes de la Marine, travelled as far as Wisconsin, where they attacked the main Fox village. Louvigny reported that ‘after three days of digging trenches under cover of steady fire by the fusiliers, two canons and a grenade mortar, they [the Fox] were reduced to suing for peace, although there were 500 warriors in the fort who were shooting ably and more than 3,000 women.’

Though Louvigny claimed in 1716 to have ‘left this country entirely at peace,’ the Fox continued their raids against the Illinois and the French. Knowing that ‘war with the Savages [did] not suit [the] colony in its current state, without troops and without money,’ the French again attempted diplomacy in order to restore peace in the Great Lakes region. Their efforts consistently foundered on the Aboriginal refusal to cease hostilities. Therefore, ‘after having [unsuccessfully] attempted the gentle approach,’ the French resolved in the 1720s to ‘entirely destroy’ and ‘exterminate’ the Fox. In 1730, when the Fox were on their way to take refuge among the Iroquois, they were intercepted by a group of Illinois warriors, who engaged them in combat and forced them to hole up in a makeshift fort. The Illinois were soon joined by Aboriginal people from nearly all the nations in the Great Lakes region, as well as Iroquois and Huron living at the missions and the Sauk and Wea, former allies of the Fox. In all, nearly 1,100 fighters (of whom only about 100 were French) gathered to lay siege to the Fox. The Fox attempted to negotiate several times but the French commander, Robert Groston de Saint-Ange, refused. After more than one month of siege, the Fox attempted to sneak out under cover of a stormy night, but their enemies, who gave them no quarter, quickly intercepted them. At the end of the battle, more than 500 Fox lay dead and many others had been taken captive, some of whom were sent to France to be imprisoned while the others were tortured or adopted by their enemies.

In 1735, a final French campaign was mounted against the Fox. In the eyes of the western allies, however, the Fox had been sufficiently punished for their arrogance and hostility to their neighbours, and the French determination to annihilate the Fox people was excessive and deplorable. Most of the nations refused to fight alongside the French army, preferring to ‘live in peace and hunt to [feed] their women and children.’ The few Aboriginal warriors who accompanied the 84 French to Iowa (mostly ‘mission’ Iroquois) refused to fight once they reached their destination, causing the expedition to fail. In a letter to the Minister of Colonies, the Governor of the day, Charles de La Boische de Beauharnois, explained the motives of the Aboriginal people in these terms:

You may well believe, my Lord, that the Savages have their policies as we have ours, and they are reluctant to see a nation destroyed for fear their turn will come next. They show the French great eagerness and then behave altogether differently. We have recent evidence of this on the part of the Odahwah, who asked for mercy for the Sauk, although it was in their interest to avenge the death of their people and of their Grand Chief.

The Governor added: ‘The Savages generally fear the French but they do not like them and nothing of what they exhibit to the French is sincere.’

Related reading

CHARTRAND, René, Canadian military heritage: Volume I (1000-1754), (Montreal : Art Global, 1993).

RAY, Arthur J., I have lived here since the world began: an illustrated history of Canada’s Native People, Rev. ed., (Toronto: Key Porter Books, 2005).

TRIGGER, Bruce G., The children of Aataentsic : a history of the Huron People in 1660, (Kingston, Ont. ; Montreal : McGill-Queen’s University Press, 1987).

Page details

- Date modified: