The World Wars

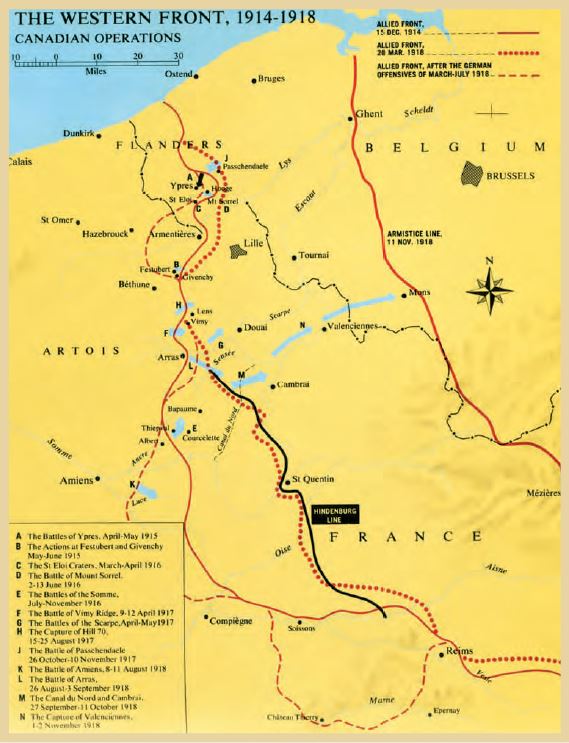

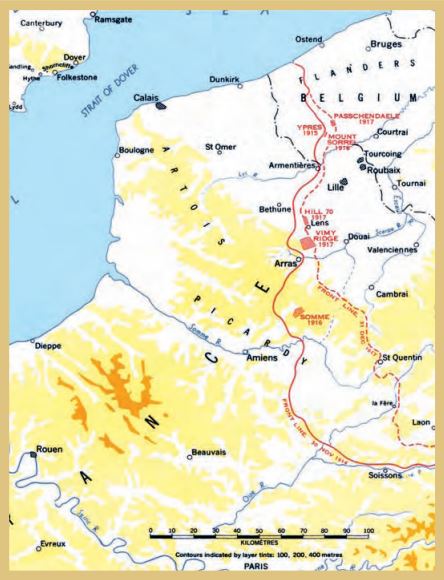

During the First World War (1914-1919) and Second World War (1939-1945), thousands of Aboriginal men and women voluntarily enlisted in Canada’s armed forces. They served in units with other Canadians, and in every theatre in which Canadian forces took part. More than 500 status Indian servicemen lost their lives on foreign battlefields during the world wars, and the number of casualties – including those injured – was much higher. Their notable contributions to the war effort became a source of inspiration and self-confidence to themselves, to their communities and to Canadians in general.

The First World War (1914-1919)

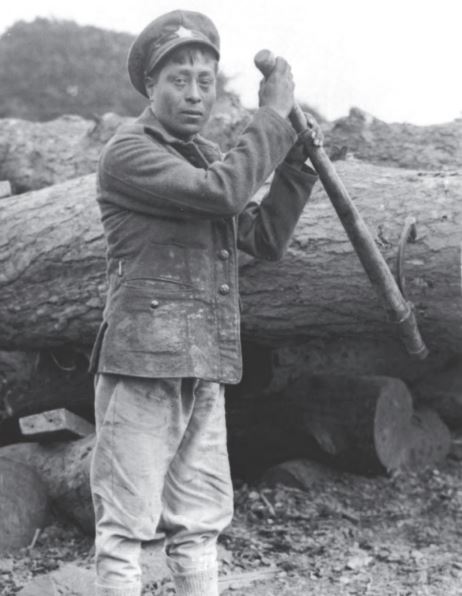

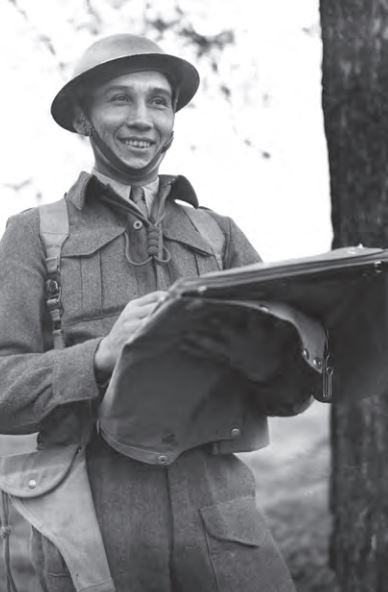

An Indian in the Canadian Forestry Corps.

By the era of the Great War, military service simultaneously provided the Aboriginal serviceman with the warrior status which was much esteemed in many Native cultures and communities back home; introduced him to the workings of a wage economy which was still unfamiliar to many; and often permitted him to utilize skills with which he was already proficient as a function of his pre-war civilian livelihood, whether in lumbering, river navigation, or hunting, scouting and tracking. The performance of at least some period of military service is still considered a significant rite of passage within many Canadian Aboriginal communities today. (Library and Archives Canada (PA 5424))

When Britain declared war in August 1914, the Dominion of Canada – as a colony – was also legally at war. The extent of Canada’s commitment, however, remained to be determined and no one could foresee the horrors that lay ahead. The First World War, or the ‘Great War’ as it was known to its generation, would force nations and empires to mobilize their resources on an unprecedented scale. Canada played its part from the beginning; so too did Aboriginal peoples in Canada.

Canadian officials contemplated the role of Aboriginal peoples in the war almost from its onset. The initial response in Ottawa was hesitation. In the popular literature of the day, ‘Red Indians’ were associated with torture and scalping, practices quite unacceptable under the rules of war laid out in the Geneva Convention (1906). ‘While British troops would be proud to be associated with their fellow subjects,’ official logic held, ‘Germans might refuse to extend to them the privileges of civilized warfare.’ The recruitment of ‘status Indians’ in Canada was therefore prohibited. While these discussions were taking place, however, many enthusiastic and dedicated Aboriginal men had already made their way to recruitment stations and begun their training for overseas service. Obviously, some militia units were either unaware of the prohibition against Indian recruits or simply decided to ignore it.

Some members of Canadian society did not give substantive weight to the worries of differential treatment and were eager to recruit Indians for service. The role of Indian agents in recruiting and Indian Affairs policies regarding enlistments from reserves fluctuated during the First World War, which reflected the contradictory mandate of the Department of Indian Affairs: it was expected to protect the rights of status Indians as well as to act in the interests of the federal government. Historian James Dempsey has charted the apparent inconsistencies in how government administrators and recruiters applied the rules. In large part, the government’s decision to actively recruit Indians appears to have been a response to Prime Minister Robert Borden’s efforts to replace the increasingly high number of casualties in front-line units by 1916. Recruitment efforts, however, did not necessarily bring the desired results. The Deputy Superintendent General of Indian Affairs, Duncan Campbell Scott, supported some Indian Councils and local Agents that objected to the tactics used by recruitment officers on their reserves. In one case, when Blackfoot elders requested that 15 enlisted Blackfoot men be discharged from the army, Indian Affairs instructed the military district’s commanding officer to release them.

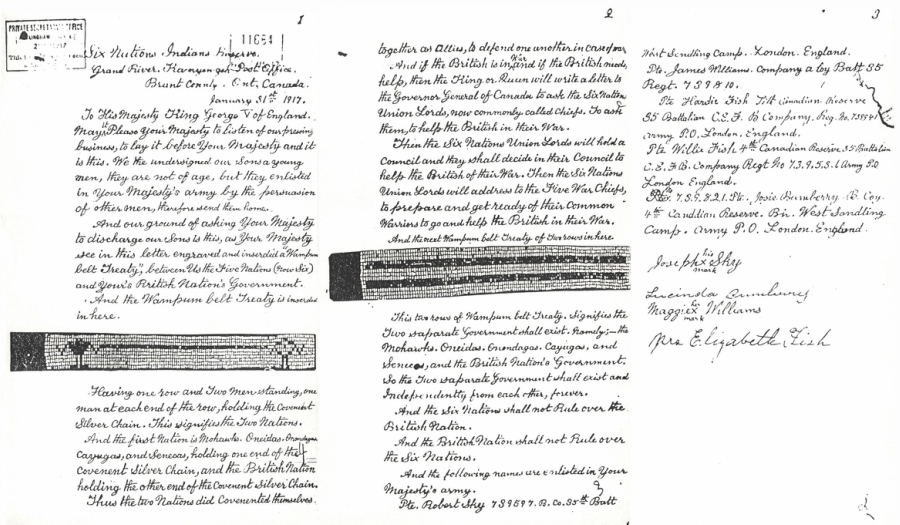

The petition of the Six Nations Clanmothers to King George V, 1917.

As would again be the case in 1939-1945, Aboriginal support for Native military involvement during the First World War was by no means universal, and the pressures to participate or not divided communities and families. Many Aboriginal cultures assign significant leadership roles to women, and in 1917 a group of clanmothers from the Six Nations of the Grand River petitioned King George V, invoking the Two-Row and Covenant Chain wampum belts which record the condition of sovereignty association existing between the Crown and the Six Nations Confederacy. The clanmothers demanded that the King release forthwith from his military service a number of their sons who had enlisted underage. (Library and Archives Canada, RG 10 Indian Affairs. (Volume 6767, File 452-15, Part 1))

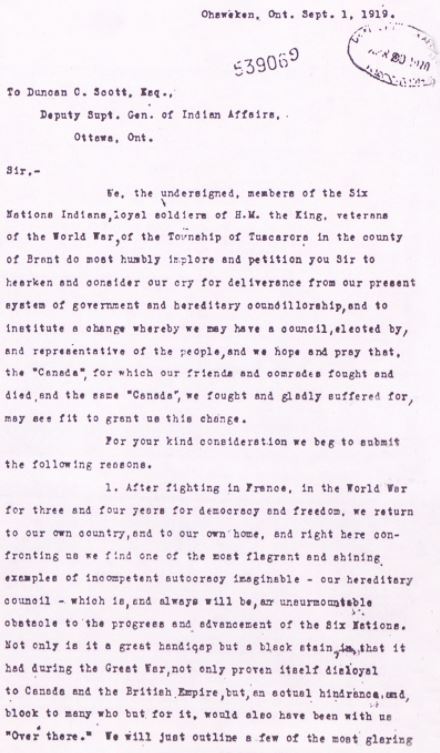

The Six Nations Veterans Petition, D.C. Scott, Deputy Superintendent General of Indian Affairs, 1919.

Following the war, newly returned veterans on the same reserve organized politically to help depose the traditional system of hereditary chiefs, which they claimed had not been supportive of them and their families during the war. (Library and Archives Canada, RG 10 Indian Affairs. (Volume 7930, File 32-32, Part 2))

For the most part, recruitment activities tried to encourage rather than coerce Indians to enlist. Private Canadian citizens also joined in the effort. In various parts of Canada, priests, missionaries and residential schoolteachers encouraged and influenced individuals who were considering voluntary enlistment. In Southern Ontario, one prominent figure offered to fund and back an entire battalion comprised solely of Six Nations warriors. Neither Ottawa officials nor the local Indian Council of Chiefs accepted the offer, albeit for different reasons. Official government policy still restricted Indian participation and, in this light, Defence officials found the offer ‘inconvenient.’ The Six Nations Chiefs’ response reflected larger political issues. Based on past treaties and alliances, the Six Nations considered themselves to be a separate nation, and thus felt that they were due a formal request from the British Crown, from one nation to another. This gesture would have political and legal ramifications, and was not one that the Canadian government could support. Nevertheless, Iroquois reserves proved active bastions of support for the war effort: the areas around Brantford (Six Nations) and Tyendinaga (Mohawks of the Bay of Quinte) became the highest sources of Indian enlistment in Canada.

In principle, the government did not form ‘ethnic’ units during the 20th Century. As a result, there were no ‘all-Indian’ units during the world wars. This makes any systematic analysis and generalizations about Indian contributions difficult. Nevertheless, several regiments boasted large numbers of Aboriginal soldiers. The 114th Battalion, more commonly known as Brock’s Rangers, drew extensively from the Six Nations of the Grand River and the Caughnawaga and St. Regis communities in Quebec. Indian officers commanded two ‘Indian’ companies of the 114th. Like many other battalions it was broken up when it arrived in England and individual soldiers were dispersed amongst other fighting battalions. Another unit with a high proportion of Aboriginal members was the 107th ‘Timber Wolf’ Battalion, raised in Winnipeg. More than 500 Aboriginal soldiers filled its ranks. It was converted to a pioneer battalion in England, then embarked to France in 1917 and participated in the battle for Hill 70, just north of Lens. The Deputy Superintendent General of Indian Affairs drew particular attention to the Anishnawbe men who served with the 52nd Battalion:

Badge of the 107th Battalion.

Pictured above is the badge worn by members of the 107th “Timberwolf” Battalion. (Canadian War Museum)

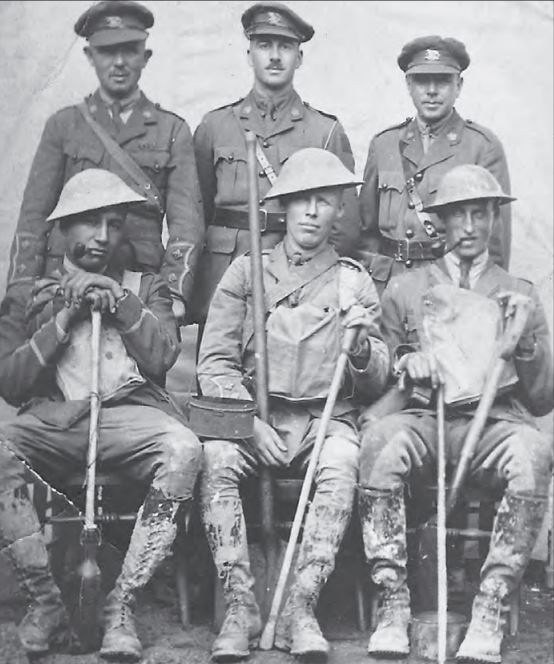

107th Battalion, "A" Company, Subalterns

The fortunes of war; Subalterns of “A” Company, 107th “Timberwolf” Battalion, France, July 29th, 1917. Pictured at front row, sitting at left, is Lieutenant Oliver Martin, a Mohawk from the Grand River Reserve; and back row standing at right, Lieutenant James Moses, a Delaware from the same Reserve. Both were later seconded to the Royal Flying Corps. Martin survived the war as a pilot, stayed active in the Canadian Militia during the interwar years, and was appointed Brigadier during the Second World War. Moses was reported missing, later confirmed killed, on April 1st, 1918 while serving as an air observer. A third Indian junior officer from the 107th, John Randolph Stacey, a Mohawk from Kahnawake, also became a pilot, but was killed in a flying accident in England a week after Moses. (J. Moses Collection)

Special mention must be made of the Ojibwa bands located in the vicinity of Fort William, which sent more than one hundred men overseas from a total adult male population of two hundred and eighty-two. Upon the introduction of the Military Service Act it was found that there were but two Indians of the first-class left at home on the Nipigon reserve, and but one on the Fort William reserve…. The Indian recruits from this district for the most part enlisted with the 52nd, popularly known as the Bull Moose Battalion. Their commanding officer, the late Colonel Hay, who was killed, stated upon frequent occasions that the Indians were among his very best soldiers. Their gallantry is testified by the fact that the name of every Indian in this unit appeared in the casualty list. The fine appearance of these Indian soldiers was specially commented upon by the press in the various cities through which the battalion passed on its way to the front. One of the Indian members of the 52nd, Private Rod Cameron, won premier honours in a shooting competition among the best marksmen of twelve battalions. He rendered valuable service at the front as a scout and sniper and was subsequently killed in action.

Private Joseph Delaronde, another Nipigon Indian, of the 52nd Battalion, won the Military Medal for gallantry in action. His cousin, Denis Delaronde, who was killed in action, was the first man of the 52nd to enter the trenches of the enemy. Two other members of this fighting Indian family, Charles and Alexander Delaronde, also served with the 52nd. The latter was wounded, returned home, and discharged, re-enlisted and went back to the front. Another Nipigon Indian of the 52nd to be decorated was Sgt. Leo Bouchard, who was awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal. Private Augustin Belanger, another Indian member of the 52nd Battalion, who was killed in action, was awarded the Military Medal. Alexander Chief, a Fort William Indian of the 52nd Battalion, returned to Canada after two years’ service with no fewer than twelve wounds. Although he was an Indian of remarkably fine physique, he fell a victim to tuberculosis as a result of the hardships he endured and died in December, 1918.

By war’s end, Aboriginal soldiers had served throughout the army. ‘Many soldiers of native ancestry shone individually within the various battalions,’ historian Fred Gaffen concluded, ‘in keeping with their traditional way of life and culture where individual heroism in battle were held in high esteem.’

Lance-Corporal John Shiwak.

Geographical isolation limited, but did not preclude, Inuit enlistments during the First and Second World Wars, and in Korea. John Shiwak (Sikoak), a Labrador Inuit from Rigolet, served with the Royal Newfoundland Regiment. He was killed on Nov. 20, 1917 during fighting at Cambrai. Frederick Freida was another Great War Inuit volunteer from the Labrador coast. During the Second World War, the presence of Inuit along the Labrador coast complicated the efforts of German U-boat crews in landing automated weather stations. Presently across the Canadian north, Inuit members of the Canadian Ranger Patrol Groups of the Canadian Forces reserve are an integral part of our military presence in the Arctic. (Royal Canadian Legion, Happy Valley, Labrador)

The Department of Indian Affairs, and in particular Duncan Campbell Scott, trumpeted the wartime achievements of status Indians. His 1919 annual report explained that, according to official records, more than 4,000 Indians had enlisted for service – approximately thirty-five percent of all status Indian males of military age. Given the challenges that faced these recruits, Scott highlighted how remarkable it was ‘that the percentage of enlistments among the Indians is fully equal to that among other sections of the community, and indeed far above the average in a number of instances.’ Furthermore, these statistics did not include non-status Indians, Métis, or Inuit, so more Aboriginal peoples served in the armed forces that any official record can provide.

In several Aboriginal communities the enlistment record was impressive. Nearly half of eligible Mi’kmaq and Maliseet men in Atlantic Canada enlisted. Every eligible male from the Mi’kmaq reserve near Sydney, Nova Scotia, volunteered. New Brunswick bands sent 62 out of 116 eligible males to the front, and 30 of 64 eligible PEI Indians joined. Although Newfoundland and Labrador remained a separate colony during the world wars, an estimated fifteen men from Labrador with Inuit ancestry served with The Royal Newfoundland Regiment in the British Army. The statistics from Quebec are somewhat sketchy, but also suggest a high enlistment rate. In Ontario, all but three eligible men from the Algonquin of Golden Lake band enlisted, and approximately 100 Anishnawbe (Ojibwa) men from isolated communities in northern Ontario travelled to Port Arthur (Thunder Bay) to sign up. As stated earlier, the Six Nations of the Grand River Reserve provided more soldiers than any other Indian community in the country: approximately 300. In Manitoba, 20 men from the Peguis band saw frontline service – an impressive statistic considering that the total adult male population was only 118. Sadly, eleven never made it home. Similarly, The Pas Band, Sioux Band at Griswold, and St. Peter’s Band all sent more than twenty percent of their adult male population overseas. More than half of the eligible adult males on the Cote Reserve in Saskatchewan served overseas. Only 29 Alberta Indians served, but 17 men volunteered from the Blood Reserve. In British Columbia, every male member of the Head of the Lake band between the ages of twenty and thirty-five enlisted. These cases are exemplary by any measure. Men who lived in the Territorial North seldom volunteered because they pursued a subsistence lifestyle and had little information about or connection to international developments, but a few – such as John Campbell, who ventured three thousand miles by trail, canoe and steamer to enlist in Vancouver – joined the war effort. ‘It must … be borne in mind,’ D.C. Scott explained at war’s end, ‘that a large part of the Indian population, located in remote and inaccessible locations, were unacquainted with the English language and were, therefore, not in a position to understand the character of the war, its cause or effect.’ This made the high levels of Aboriginal enlistment even more remarkable.

Why did they join? ‘No single answer suffices,’ Janice Summerby has explained. ‘In newspaper interviews, oral histories, biographies, and other published works, Aboriginal veterans – not unlike other war veterans – speak of the call to adventure, the attraction of regular pay, and the desire to follow friends and family into service.’ There were a multitude of reasons, from patriotism to status within their communities. According to one Indian agent, ‘the leading men of a number of west coast tribes have expressed their desire to be allowed to serve the empire at this crisis, and offer to send numbers of their younger men if called upon.’ In Ontario, Chief F.M. Jacobs of Sarnia wrote to D.C. Scott that his people were willing to provide ‘help toward the Mother Country in its present struggle in Europe. The Indian Race as a rule are loyal to England; this loyalty was created by the noblest Queen that ever lived, Queen Victoria.’ Such patriotism was tied to Aboriginal identities and culture. James Dempsey has also suggested that a persistent ‘warrior ethic’ amongst the Prairie Indians motivated young men to join.

For those who served, the experience brought with it a unique brand of culture shock. ‘For Indians who had been raised in the traditional way there were some unique problems of adjusting to army life,’ Gaffen observed. The rigid military hierarchy in the Canadian Corps sharply distinguished between officers and other ranks, whereas traditional relationships between war chiefs and warriors were more equal and familiar. Other systemic differences plagued Aboriginal enlistees during the First World War. Recruits from isolated communities faced language barriers when they went off to train in the larger centres. Some, such as Anishnawbe William Semia from Northern Ontario – who travelled more than 400 kilometres to enlist and found himself in the city for the first time – had the fortune of meeting other Aboriginal recruits with basic training who could assist them. Semia eventually mastered English and fought in the muddy trenches at Passchendaele. A few fortunate individuals found themselves in the 107th Battalion, where Lieutenant-Colonel Glen Campbell spoke the native tongue of several of his men, or in an Alberta unit which had sixteen interpreters – including the commanding officer, who himself spoke Cree, Chipewyan, Dogrib and several dialects of Inuktitut. Another factor working against Native people was health, particularly for those from the more remote parts of the country where they had had little contact with white men and the white man’s diseases. These enlisted soldiers were unusually susceptible to sicknesses such as tuberculosis and pneumonia, and many of those who enlisted were struck down early in their military careers. This susceptibility was also used as a reason for requesting the de-enlistment of men serving overseas by their elders back home, as in the case of the Blackfoot of Alberta.

Many Aboriginal communities eagerly contributed in whatever ways they could. Their donations to the Patriotic Fund became a source of propaganda; posters promoted the idea that Aboriginal peoples were so generous that non-Aboriginal people had to follow their lead. Reserve communities donated to the Red Cross, fundraised by selling native crafts, and knitted socks and sweaters for those serving overseas. Although Aboriginal people were often poor, government officials such as D.C. Scott proved through statistics how they generously gave to the war effort. The amounts varied greatly, from $7.35 donated by the Children on John Smith’s Reserve to over $8,000 by the File Hills Agency. Even the smallest donations were heartfelt. The Sioux of Oak River sent their donation of $101 directly to the King stating ‘nobody asked us to do this we are doing this with our free will this is not much but we are doing it with all our hearts.’

Voluntary contributions were one thing; compulsion was another. The most contentious issue facing Aboriginal peoples in Canada during the world wars was conscription, or compulsory military service. While members of so many communities had willingly enlisted as volunteers, they did not believe that they should be forced into military service. In 1917, after the spectacular Canadian Corps victory at Vimy Ridge, the federal government faced a severe manpower shortage overseas and decided that conscription was necessary. When the Military Service Act was originally drafted, government officials did not consider the special case of the Indians. Indian communities reacted swiftly, however, and a flood of letters from Indians and Indian agents demanding that status Indians be exempt from conscription caught Indian Affairs unprepared. ‘There are no general grounds I know of for relief or exemption of Indians from military service,’ D.C. Scott initially claimed, which meant that they would be called up for conscription like everyone else in Canada. Many Indian communities considered this a grave injustice, reminding the government of verbal treaty promises that assured them they would never have to take up arms against their will. Numerous letters noted that status Indians did not have full rights of citizenship: they could not vote, for example, and were legally treated as ‘wards’ or ‘minors.’ Given this status, how fair would it be to compel them to serve and assume the same responsibilities as enfranchised people? In the end, this sustained Aboriginal lobbying of the government proved successful. Cabinet passed an order-in-council (P.C. 111) on 17 January 1918 that exempted Indians from the Military Service Act. Indians could still be called upon to perform non-combat roles in Canada, but this legislation made it easier for them to claim deferrals for industrial or agricultural work. Status Indians who served overseas during the First World War thus did so as volunteers.

Henry Norwest gravesite.

An Aboriginal serviceman’s civilian livelihood, in combination with longstanding stereotypes attributing extraordinary stealth and cunning to Natives, in both World Wars and Korea often had the effect of placing such individuals in the most hazardous jobs the Army had to offer. Henry Norwest, a Cree-Métis saddler, cowboy, trapper and hunter from Alberta, served as a sniper with the 50th Battalion C.E.F. Officially credited with 115 confirmed kills, the highest “score” recorded in the armies of the British Empire to that point, Norwest was killed in action August 18th, 1918 near Amiens. (Glenbow Archives)

The lore of the war maintains that Aboriginal soldiers particularly distinguished themselves in dangerous but essential infantry roles. Accounts of individual gallantry abound in studies such as Gaffen’s Forgotten Soldiers, Janice Summerby’s Native Soldiers, Foreign Battlefields, and James Dempsey’s Warriors of the King. Several themes clearly emerge. First and foremost, Aboriginal soldiers were lauded as effective snipers and scouts. Gaffen concluded that in battle ‘the skills of the Indian hunter and warrior came to the fore.’ Aboriginal soldiers were seen to be adaptable and patient, with keen observation powers, stamina, and courage. Correspondingly, an Aboriginal background and rugged livelihood (acting in concert with longstanding stereotypes attributing extraordinary stealth and cunning to Native people) sometimes placed Aboriginal soldiers in the most hazardous jobs that the army had to offer. Anecdotal evidence suggests that many relished and excelled in these tasks. Francis Pegahmagabow, an Ojibwa from the Parry Island agency in Ontario, was perhaps the most renowned for his marksmanship. He enlisted in August 1914 and went on to serve at Ypres, the Somme, Passchendaele, and Amiens. Credited with 378 kills, his record was amongst the most impressive of any Allied sniper on the Western Front. Amongst his many awards for bravery were the Military Medal and two Bars for his services – he was one of only 39 members of the CEF to achieve that distinction. Métis marksman Henry Norwest also displayed remarkable prowess as a sniper. ‘On one occasion he waited two days for two enemy snipers who had heard his rifle, as he accounted for another of their friends, knowing they were suspicious of his post,’ one of his comrades recalled after the war. ‘At last he caught them off guard and one went down followed by the other in fifteen minutes.’ Lance Corporal Norwest amassed 115 confirmed kills and a Military Medal before falling to an enemy sniper in August 1918. In all, at least 37 Aboriginal infantrymen were decorated for gallantry. Aboriginal soldiers also served in other important roles, and by Armistice Day they could be found in pioneer, forestry, and labour battalions, and amongst the Railway Troops, Veterinary Corps, Service Corps, and the Canadian Engineers.

Formal educational restrictions meant that few Aboriginal soldiers had access to commissions as officers, but many became non-commissioned officers: corporals, lance corporals, and sergeants. These leadership roles built confidence and demonstrated that they were just as capable and intelligent as their non-Aboriginal comrades. A few managed to secure commissions, often by virtue of their performance in the field, including Lieutenants Cameron Brant and Oliver Milton Martin, and Captains Alexander Smith and Charles D. Smith, all from Six Nations, and Hugh John McDonald from the Mackenzie Valley. A small number also served in the Royal Flying Corps/Royal Air Force, including Lieutenant James David Moses of Oshweken and Lieutenant John Randolph Stacey of Kahnawake. In late March 1918, Moses wrote home:

My pilot and I have had some very thrilling experiences just lately. We bombed the German troops from a very low height and had the pleasure of shooting hundreds of rounds into dense masses of them with my machine gun. They simply scattered and tumbled in all directions. Needless to say we got it pretty hot and when we got back to the aerodrome found that our machine was pretty well shot up.

On 1 April, his plane was shot down by anti-aircraft fire and he lost his life. He was one of 88 volunteers from Six Nations who lost their lives during the conflict.

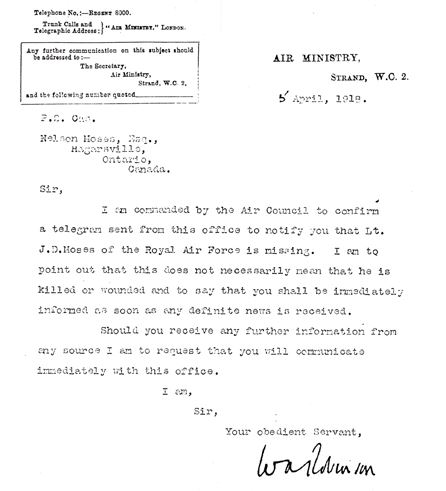

Lieutenant J.D. Moses of the Royal Air Force is missing.

The dreaded telegram. It was subsequently revealed through German Air Force documents that the RAF 57 Squadron DH4 aircraft in which Moses was the observer was shot down by Ltn. Hans Joachim Wolff of Jagdgeschwader Freihrr von Richtofen, popularly known as the Flying Circus. Lieutenant Moses was 28, and his pilot, 2nd Lieutenant Douglas Price Trollip (a South African) was 23. (J. Moses Collection)

In all, more than 300 status Indians died in the Great War. Hundreds more were wounded, in body and in mind. Some veterans returned with tuberculosis and other diseases that they had contracted amidst the horrid conditions on the Western Front. When some soldiers returned to isolated communities at the end of the war, they also unwittingly carried with them the deadly influenza that swept the country in 1919. They had made deep sacrifices alongside their comrades from the rest of Canada, and Aboriginal peoples remembered their patriotic contributions to victory. ‘Now that peace has been declared, the Indians of Canada may look with just pride upon the part played by them in the Great War, both at home and on the field of battle,’ Edward Ahenakew, a Saskatchewan Cree clergyman proclaimed in 1920:

Not in vain did our young men die in a strange land; not in vain are our Indian bones mingled with the soil of a foreign land for the first time since the world began; not in vain did the Indian fathers and mothers see their son march away to face what to them were understandable dangers; the unseen tears of Indian mothers in many isolated Indian reserves have watered the seeds from which may spring those desires and efforts and aspirations which will enable us to reach sooner the stage when we will take our place side by side with the white people.

For this sacrifice, changes were necessary to better the Indian way of life in Canada.

Interwar Politics

In the Indian Affairs’ 1918-1919 Annual Report, Deputy Superintendent of Indian Affairs Duncan Campbell Scott wrote that:

In this year of peace, the Indians of Canada may look with just pride upon the part played by them in the Great War both at home and on the field of battle. They have well and nobly upheld the loyal traditions of their gallant ancestors who rendered invaluable service to the British cause in 1776 and in 1812, and have added thereto a heritage of deathless honour, which is an example and an inspiration for their descendants.

Portrait photo of Charlotte Edith Anderson Monture, AEF.

Demonstrating the Iroquois woman’s traditional independence of spirit, Edith Anderson from the Six Nation’s of the Grand River reserve was living and working as a registered nurse in New York City when the U.S. entered the First World War in 1917. Joining the American Expeditionary Force as an army nurse, she served overseas in France until demobilized in 1919. She returned home to the reserve to continue nursing, and to raise a family. Aboriginal women on the homefront during both World Wars were heavily involved in charitable work, and with various forms of war relief and soldier’s support. During the Second World War, a number of Aboriginal women served in the women’s branches of the three services. (J. Moses Collection)

Portrait photo of Lieutenant F.O. Loft.

“As peaceable and law-abiding citizens in the past, and even in the late war, we have performed dutiful service to our King, Country and Empire, and we have the right to claim and demand more justice and fair play as recompense.” Lieutenant Frederick Ogilvie Loft had served with the Canadian Forestry Corps during the First World War. A Mohawk from the Six Nations of the Grand River, in 1919 he founded the League of Indians of Canada, the first national Native political organization in the country. The League’s political activities (which were entirely self-funded) in agitating for Indian rights and political reform soon became an irritant to the federal government. In the Bolshevik scare of the 1920’s in Canada, some government officials were concerned that the fledgling Native political organizations were somehow affiliated with communist leagues and militant trade union movements. The 1927 Indian Act amendments attempted to limit Indian political activity. Although never fully successful, these restrictive Indian Act clauses remained in force until 1951.

There was, however, more continuity than change in the administration of Aboriginal peoples after the war. ‘In contrast to the country which made political and economic gains,’ Gaffen concluded, ‘the lot of the Indian people remained much the same. The sacrifice of killed and wounded achieved very little politically, economically or socially for them.’ Historian James Dempsey has described the disappointment felt by many Prairie Indian veterans when they returned home. Their exposure to the broader world had changed them profoundly, but they returned to the same patronizing society that they had left. Although eligible for the vote overseas, they lost their democratic rights after the war. Furthermore, the inequitable eligibility requirements and dispensation of veterans’ settlement packages (money and land) disadvantaged many Indian veterans. Although they had fought overseas, their legal status had not changed; they continued to be wards of the Crown.

Armed with increased political awareness following their experiences at war, veterans began to organize politically. Fred Loft from Six Nations spearheaded the establishment of the League of Indians of Canada, the first pan-Canadian Indian political movement, in the early 1920s. ‘As peaceable and law-abiding citizens in the past, and even in the late war, we have performed dutiful service to our King, Country and Empire,’ Loft explained, ‘and we have the right to claim and demand more justice and fair play as a recompense.’ The treatment of First Nations veterans was amongst the primary concerns of Loft and other Aboriginal leaders. Aboriginal soldiers had fought in the war as equals, and even voted for the first time in 1917, but when they returned home they found that they had unequal access to veterans’ benefits compared to non-Indians. The Soldier Settlement Acts of 1917 and 1919 were the cornerstone of the federal government’s attempt to look after Great War veterans, providing access to land and farming implements at a low rate of interest. When status Indian veterans expressed an interest in farming on their own reserves, however, Indian Affairs took over administration of the act from the Department of Soldiers’ Civil Reestablishment. Complications regarding ownership of lands both on and off reserves made it nearly impossible for Indian veterans to receive reestablishment loans. Allegations that returned soldiers were being forcibly enfranchised (losing their Indian status), were denied War Veterans’ Allowance Act benefits, that the application of the Last Post Fund was inequitable, and also that 85,000 acres of allegedly ‘surplus’ Indian reserve land were surrendered for non-Aboriginal veteran settlers, further frustrated Aboriginal veterans during the 1920s and 30s.

Indian Soldiers' war memorial Wekwemikon indian reserve. (Canadian Museum of Civlization (#78927))

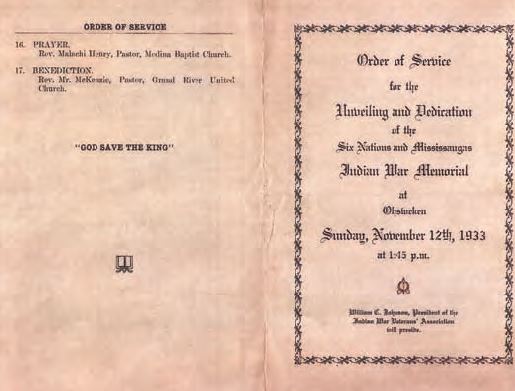

Order of service for the Unveiling and Dedication of the Six Nations and Mississaugas Indian War Memorial...Sunday, November 12th, 1933. (J. Moses collection)

Notice to trespassers on Indian Reserves c. 1922. (Canadian Museum of Civlization (#56862)

As in towns, villages, hamlets and cities across all parts of Canada, during the interwar years, Aboriginal communities likewise recalled the sacrifices of their fallen members. Despite their recent service overseas, there were few improvements to the lot of Aboriginal peoples in Canada following the War. The impacts of the Depression were especially hard upon Native communities. Indian Act amendments introduced in 1920 briefly mandated the compulsary enfranchisement (loss of legal Indian status) of more “advanced” Indians deemed by Indian Affairs to have achieved an acceptable level of self-sufficiency. By definition this category tended to include many newly returned veterans. Earlier Indian Act amendments had for a time stipulated the compulsary enfranchisement of any Indian person in receipt of a university degree.

The veterans generated sympathetic attention. During the interwar years (1919-39) ‘no factual account [of the Great War] was complete without a salutary reference to the gallantry of Canada’s “braves at war,”’ historian Jonathan Vance observed. The ties of camaraderie transcended cultural lines. The Royal Canadian Legion acknowledged that Aboriginal veterans were being short-changed, and passed resolutions demanding equal benefits for status Indians. In 1936, government policies were revised to reflect these recommendations. By this point, however, ominous clouds had begun to gather in the Far East and in Europe. When the storm broke soon thereafter, Canada’s Aboriginal peoples again found themselves fighting alongside their comrades to free the world from dictatorial tyranny.

The Second World War (1939-1945)

The Indian Act, 1938, sections 140-141.

By the eve of the Second World War, status Indians in Canada had among the most severely limited range of civil, political and legal rights of any group of people anywhere in the Commonwealth. Successive Indian Act amendments in force between 1884 and 1951 (thus spanning the era of the two World Wars and Korea) variously placed restrictions on status Indian travel, the raising of funds in payment of legal advice, and the perpetuation of cultural practices including spiritual observances and the wearing of traditional dress. (Department of National Defence)

On 10 September 1939, the Canadian Parliament declared war against Nazi Germany. Hitler’s armies had invaded Poland, and the leaders of the Western world realized that appeasement was no longer a viable strategy. Nazi aggression had to be countered, and Canada could not stand aside in another great war involving Great Britain. Yet Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King was loath to make an unlimited commitment. Canada’s war effort thus began as one of ‘limited liability.’ A modest military force of one division was sent overseas, and the government devoted the bulk of its attention to the British Commonwealth Air Training Plan and to gearing up for war production. Fearful events soon made this ‘Canada’s War,’ and for six gruelling years Canadians poured their energies into a fight to protect and uphold Western democratic ideals. By war’s end, out of a population of only 11 million people, more than one million Canadian men and women had donned a military uniform.

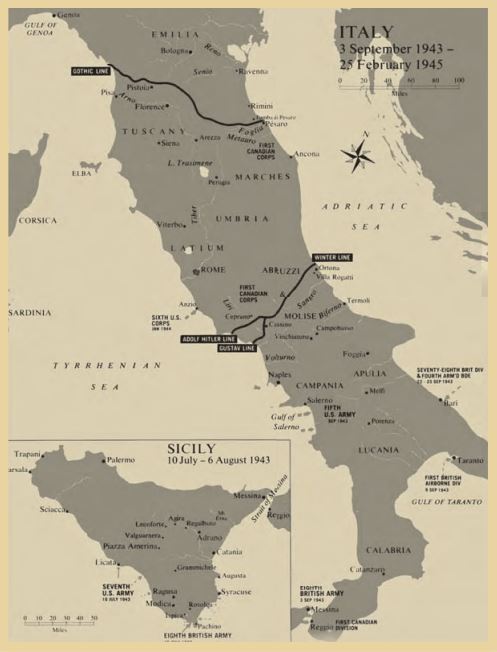

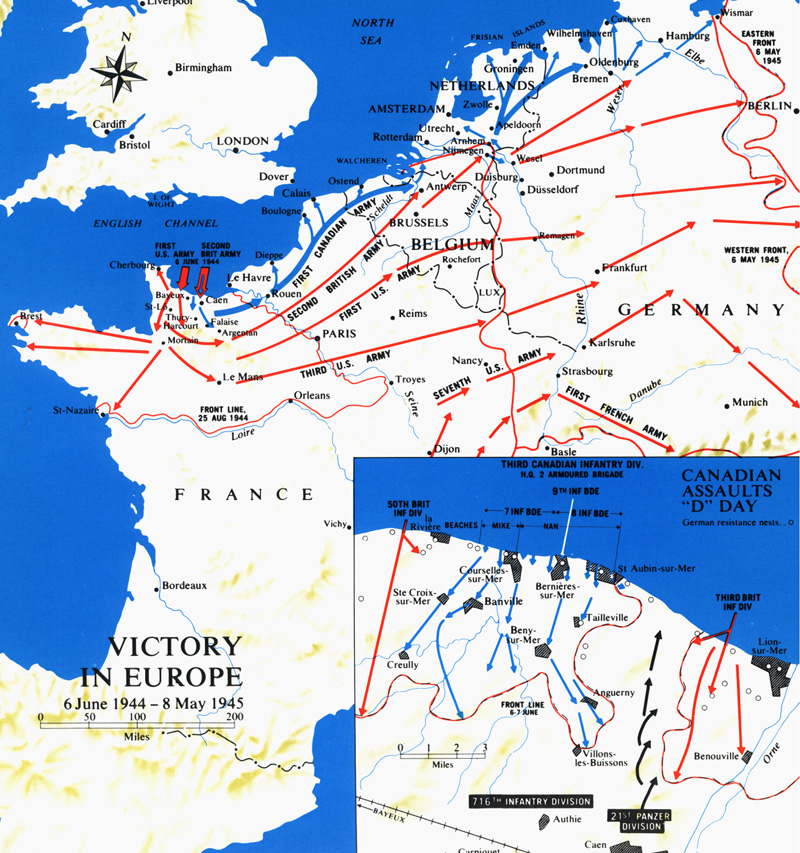

Despite Aboriginal veterans’ discontent during the interwar years, there remained an undeniable sense of patriotism across Canada when the Second World War broke out. When the German armies swept through Denmark, Norway, Holland, Belgium and France in May and June of 1940 the Canadian government dropped its ‘limited liability war effort’ for one of ‘total war.’ Aboriginal peoples, like all other Canadians, were called upon to make sacrifices and contribute to the national crusade to defeat totalitarian aggression. Aboriginal service personnel were among the casualties at Hong Kong and Dieppe, they fought in Italy and Sicily, served on convoy escorts in the Battle of the Atlantic, and flew with bomber and fighter crews around the world. They landed with 3rd Canadian Infantry Division on D-Day, and fought through the campaigns in Normandy and Northwest Europe. The war was a partnership between all Canadians who were willing to sacrifice their lives to restore peace and security to a world in turmoil.

There were many reasons to volunteer for the defence of Canada and Britain. As in the First World War, these reasons were as diverse as the Aboriginal people who participated. Lawrence Martin, an Ojibway with the Red Rock band in northern Ontario, had many family members who served in both world wars. His uncle was killed at Passchendaele, and his father was wounded twice in the First World War. His father said to him ‘if you [have] to go to war do not shirk your duty.’ He served with the Lake Superior Regiment in Europe. Sidney Gordon, who grew up on the Gordon’s Reserve in Saskatchewan, joined the army in April 1941. ‘I was single so I thought it was good experience for me to go in the army,’ he recalled. He was making little money at the time working as a farm labourer, ‘so I figured a dollar and a half a day would be better than what I’m doing. See I get my food, I get my clothes, so therefore I thought of it.’ Russell Modeste, a member of the Cowichan band who served in the Second World War, recalled that the reason he served was his experience at the Coqualeetza Residential School in Sardis, British Columbia. ‘I heard some of the staff mention that the fact that a member of their family or loved ones had been killed in the bombing in London, Scotland and brothers and cousins who were killed in North Africa.’ His experiences at residential school prepared him for military life:

We lined up every morning for whatever, breakfast, lunch, supper, church…. So when I entered the military this was nothing new to me, I just blended right in with it and little easier than some of the white boys who came out of the cities who had no inkling of any discipline in the military, if you will. So I was partly prepared. I left the school at the age of 16 and worked for a couple of years and … the day I turned 18, instead of going to work … in the logging industry… I went to the recruiting office and joined up.

Like others, he joined out of patriotism and a desire to help stop the Germans: he wanted to ‘do his bit.’ His father was upset. ‘He said I know what you’ve done and it’s none of you’re business,’ Modeste explained. ‘If the War was on in Canada I would expect you to do what you’ve done and help the country. But the War’s in Europe, it’s a European War, it has nothing to do with you, it’s none of your business and I don’t appreciate what you’ve done. I said dad it’s too late I’ve given my oath I have to go through with it.’ Overseas, Modeste served on the front lines with the Lanark and Renfrew Scottish Regiment, fighting through the mountains, vineyards, and small towns of Italy.

For some Aboriginal soldiers, military service was an adventure, an opportunity to demonstrate their loyalty to the King and Queen. Chief Walking Eagle from Rocky Mountain House, Alberta encapsulated this sentiment when he declared, ‘every Indian in Canada will fight for King George.’ For others, it was the chance to perpetuate a warrior tradition, or represented freedom from stifling conditions on reserves. For a large number of hopeful recruits it represented a welcome relief to unemployment. The depression of the 1930’s had devastated many reserve communities, and like other Canadians, Aboriginal men looked to support their families in whatever way they could. The chance to become a soldier meant a good salary and the additional benefit of a dependents allowance. After the declaration of war, there was no shortage of eager men in the enlistment queues.

Early in the war, the Royal Canadian Navy, Canadian Army, and Royal Canadian Air Force were selective in who they chose to enlist. In the Army there were general requirements for good health and minimum standards for education. Across the country many more men volunteered than were accepted, and the racial barriers to Aboriginal participation that were evident during the First World War were still in place. Aboriginal people had, on average, a substantially lower level of education than most other Canadians. This excluded many from enlisting early in the war. The number of cases of tuberculosis and other infectious diseases that ravaged Aboriginal people were in excess of those in non-Aboriginal communities. An Indian Affairs Branch report that listed the incidence of tuberculosis among Indians during the war as ‘more than ten times as high as among the white population.’ In fact, an assistant superintendent of medical services noted that it was possible to identify the health of a reserve community based on the number of recruits that enlisted. Additional barriers to Aboriginal enlistment were set up through individual prerogative. In certain areas, despite letters lauding Aboriginal achievements from Ottawa, local recruiting officers were disinclined to take applicants from Aboriginal volunteers. In some instances, these refusals stemmed from the preconceived notion that Aboriginal recruits could not handle the demands of the training program and the confinement of military quarters.

The Royal Canadian Navy was more selective in its recruitment policy than the Army. At the onset of the war, the standing policy held that only a person ‘of pure European descent and of the white race’ would be admitted for naval service. This policy effectively barred any Aboriginal participation. There were three primary reasons for this discriminatory policy, outlined in a report from the Commanding Officer, Pacific Coast: that confined spaces do not lend themselves to positive racial mixing; that there were legal restrictions on Indian access to liquor (the navy was the only arm of defence that still distributed a grog ration to its enlistees); and that Indians would have to be messed separately. The Canadian government upheld this policy until 12 March 1943, when it was finally changed. The application of this policy, however, was not universal. The 1942-43 Indian Affairs report already listed nine status Indians in the Navy.

The Royal Canadian Air Force had high education standards and also did not accept ethnic applicants. The Royal Canadian Air Force was closely linked to its British counterpart, the Royal Air Force, and it was expected to follow the same codes of behaviour and policies. Prior to the war, the standard was not only ‘pure European descent,’ but also specifically ‘sons of parents both of whom are … British subjects.’ In 1939, correspondence from the acting Chief of Air Staff indicated that North American Indians were an exception to this rule. Despite this apparent opening, there was far less Aboriginal representation within the air force than in the infantry. To become a pilot, applicants were required to have completed ‘junior matriculation’ – the equivalent to grade 11 or 12. This effectively eliminated most Aboriginal hopefuls: more than seventy-five percent of Aboriginal peoples in Canada attained a level of education equivalent to grade 1 to 3. As a result, the 1942-1943 Indian Affairs Branch report listed only twenty-nine Aboriginal servicemen in the RCAF. Nevertheless, men like David Moses, a Delaware from Ohsweken who had studied agriculture at the University of Guelph before the war, served with the RCAF. He was in Iceland for the last year of the war flying Consolidated Canso ‘flying-boats’ on convoy duty in search of German U-boats.

Regulations aside, Aboriginal people enlisted in high numbers and once again a sense of equality developed in the Canadian forces, inspired in part by shared training and camaraderie. Enlistees – both Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal – spent months training in Canada before deploying to Britain. There, they spent months further preparing for active service. The troops also spent time socializing with Britons. Russell Modeste found the reception for Native people in England to be a refreshing change from the discrimination that he faced in Canada. ‘When we landed in England it was so different,’ he reminisced. ‘We’d go to a dance and anyone you asked, yes they would dance.’ Aboriginal soldiers, free from the constraints of the Indian Act and the watchful eyes of Indian agents, discovered English pubs and lived the life of any other soldier overseas. This experience was formative: it was liberating to some; for others it served to highlight the inequities of Aboriginal life at home. It left lasting impacts, which ranged from growing personal self-confidence, to marriage with British citizens, later called ‘war brides,’ to increased Aboriginal activism in the post-war years.

Aboriginal Peoples’ direct contributions to the war effort through military service grew during the war, as it had during the previous one. In the 1940 Annual Report of the Indian Affairs Branch, Director H.W. McGill observed that:

Always loyal, [Indian communities] were not slow to come forward with offers of assistance in both men and money. About one hundred Indians had enlisted by the end of the fiscal year and the contributions of the Indians to the Red Cross and other funds amounted to over $1,300.

As laudable as this initial participation was, McGill subsequently noted that by 1942 the rate of participation was not as high as it had been during the First World War. Aboriginal men and women were drawn to high paying war industry employment off-reserve. Enlistments were still recorded in all provinces in Canada, and the 1942 Annual Report indicated an increase in enlistees to 1,801. But mid-1943, the number of Indian service personnel grew to 2,383 and then swelled to 2,603 in 1944. At the war’s end, the Indian Affairs Branch officially reported that 3,090 status Indians had participated in the war (2.4% of the 125,946 status Indians identified in the Canadian census). As was the case during the First World War, the figure for Aboriginal soldiers was undoubtedly much higher because non-status Indians and Métis were excluded from this count.

| Province | Total native population | Native enlistment | |

|---|---|---|---|

| People | Percentage | ||

| Prince Edward Island | 266 | 27 | 10.2% |

| New Brunswick | 2,047 | 203 | 9.9% |

| Nova Scotia | 2,364 | 117 | 4.9% |

| Ontario | 32,421 | 1,324 | 4.1% |

| Saskatchewan | 14,158 | 443 | 3.1% |

| Quebec | 15,182 | 316 | 2.1% |

| British Columbia | 25,515 | 334 | 1.3% |

| Manitoba | 15,892 | 175 | 1.1% |

| Alberta | 12,754 | 144 | 1.1% |

| Yukon | 1,531 | 7 | 0.0% |

| Northwest Territories | 3,816 | 0,0% | - |

| Total | 125,946 | 3,090 | 2.4% |

Enlistment rates differed by region. The Maritimes boasted the highest per capita rates of participation, with 7.4% of the overall status Indian population enlisting. Ontario had the highest number of Aboriginal recruits, which registered just over 4% of the status Indian population in that province. Slightly more than 2% of Quebec Indians served. Nearly 1.8% of all Prairie Indians enlisted, although Saskatchewan participation rates were significantly higher than those in Alberta or Manitoba. Finally, 1.3% of status Indians living in British Columbia served overseas. The increased demand for British Columbia fishers following the internment of the Japanese Canadians helps to account for this comparatively low rate of participation. The tiny number of enlistments from the Territorial North reflects the relative isolation of their communities, as well as their involvement in other wartime activities such as remote airfield and road construction connected to the Alaska Highway, Northwest and Northeast Staging Routes, and the Canol oil pipeline, which dramatically transformed their homelands.

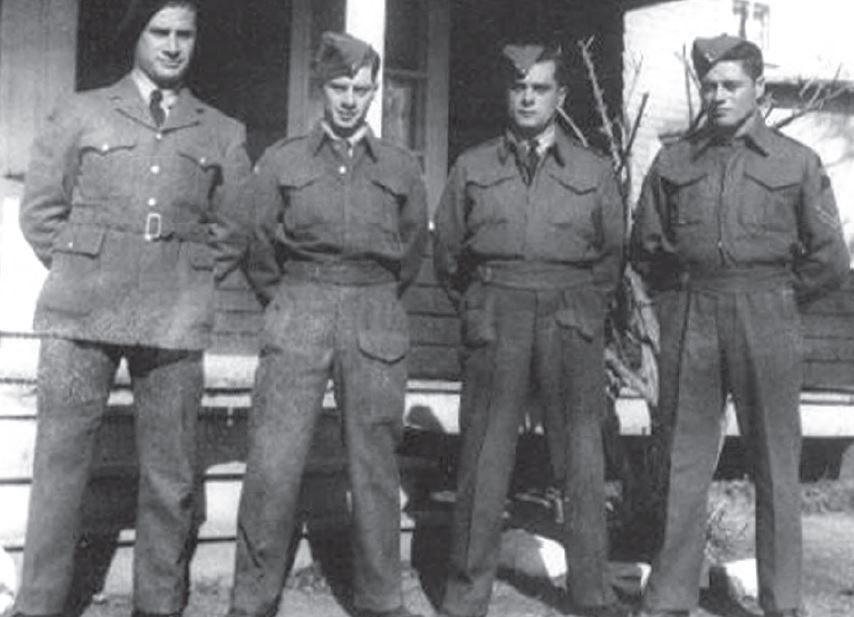

The Lainé brothers from the Huron-Wendat Reserve in Wendake, Quebec.

Not knowing if she would see her sons alive together again, their mother took the opportunity to take this group photograph (date unknown). From left to right are: Joffre (who served with the American army), Fernand, Robert and Jean-Baptiste. All four brothers survived the war. (Photo courtesy of Denis Lainé)

Aboriginal women also served and noted a spirit of camaraderie that transcended ethnic lines. Dorothy Asquith, a Métis who served in the RCAF Women’s Auxiliary, recalled:

Discrimination? Everybody was so involved in what was happening with the war that nobody was involved in such pettiness. I don’t think you bothered to look at the colour of your buddies’ skin, especially the guys who were involved in warfare. A couple cousins of mine said, “Who the hell ever stopped to look at colour? We were so all darned glad that you could get a place to duck into; who gave a damn who’s with you? We were there together, two lives. That’s my feeling; everything was too serious to think petty like that.

P. Gayle McKenzie and Ginny Belcourt Todd have interviewed and recorded the memories of some of the Aboriginal servicewomen in Our Women in Uniform. In their reminiscences, these women indicated that their reasons for joining up were not very different from those commonly cited by Aboriginal men. Several women noted the prospect of earning 65 cents a day (less than the wage paid to male recruits), the opportunity to travel, and patriotism. They were trained in non-traditional jobs, but their primary role was seen as supportive. The RCAF Women’s Division motto was ‘We serve that men may fly.’ In the Canadian Women’s Army Corps, Aboriginal women learned first aid, military clerical duties, and motor mechanics. In 1943, 16 of the 1,801 Aboriginal people in military service were women. A 1950 government memorandum indicates that 72 status Indian women served overseas during the world wars.

Aboriginal service also transcended generational lines. Older men not eligible for overseas service enlisted for home defence with the Veteran’s Guard. For instance, Joe Dreaver from the Mistawasis Cree Band had earned a Military Medal at Ypres in the Great War; during that conflict he had lost one brother in action and another who later died from his wounds. In the Second World War he joined the Veteran’s Guard while three of his sons and two daughters served overseas. The McLeod family from the Cape Croker Reserve, on the Bruce Peninsula in south-western Ontario, also had substantial representation in the military. John McLeod, an Ojibwa, served in the Great War and with the Veteran’s Guard of Canada in the Second. Six of his sons and one of his daughters enlisted between 1940 and 1944: two of the boys were killed in action, and two others were wounded. In acknowledgment of her family’s sacrifice, Mrs. McLeod was named Silver Cross Mother of the Year in 1972, and she was the first Canadian Indian to lay a wreath on the National War Memorial in Ottawa on behalf of mothers who lost their children to the wars.

The McLeod family was not alone in its sacrifices. In October 1943, the Globe and Mail reported that the Cape Croker Reserve – total population of 471 – had 43 men in uniform with the army, navy, and air force; nine members of the Veterans Guard; and seven women with the Canadian Women’s Army Corps. These were exceptional numbers. In British Columbia, the interior agencies of Kamloops, Stuart Lake, Williams Lake, Kootenay and the Okanagan had the highest rates of enlistment. In Alberta, where the overall numbers were much lower than the other provinces, the Blood, Lesser Slave Lake, Saddle Lake and the Blackfoot agencies provided the most recruits. Saskatchewan had higher than average representation for the Prairies; the agencies with the highest enlistments were Carlton, File Hills, Crooked Lake and Duck Lake. In Manitoba, Fisher River, Portage la Prairie and Norway House proved to be solid recruiting grounds. In the well-populated province of Ontario, the Six Nations, Manitoulin Island, Parry Sound and Tyendinaga agencies produced high numbers of volunteers. Most Indian recruits in Quebec came from Restigouche, St. Regis and Lorette agencies. On the East coast the agencies of South West (in New Brunswick) and Kings (in Nova Scotia) contributed the highest numbers of young men and women to service overseas.

After the Japanese surprise attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941, West Coast residents demanded protection from possible attack. In response, the Pacific Coast Militia Rangers were formed in British Columbia. These voluntary ‘citizen-soldiers’ helped to defend the ‘Pacific Province’ by patrolling their local area, reporting any findings of a suspicious nature, and adopting guerrilla tactics in the case of enemy invasion. By 1943, 15,000 British Columbians and Yukoners served as Rangers in isolated communities from Dawson to the Queen Charlotte Islands to the American border. Given the demographic and geographical realities of remote coastal areas, Aboriginal peoples made ‘natural’ Rangers. ‘Indians, with knowledge of trails that are charted imperfectly,’ the Vancouver Sun noted on 6 March 1942, were ‘given a chance to do heroic work in defense of a province … impregnable against the yellow menace through intelligent, understanding manning of its contours and natural barriers.’ The Pacific Coast Militia Rangers gave Aboriginal men in B.C. a chance to serve in the defence of their communities while continuing their daily employment and traditional activities. They made a vital contribution in several areas, particularly along the extensive – and vulnerable – Pacific coastline, serving as guides and scouts for soldiers on Active Service. The members from Aboriginal communities provided important operational intelligence to the military, reporting unusual activities and phenomena (such as sighting Japanese bomb-carrying balloons) through to war’s end in September 1945.

Home front contributions went beyond military service. As had been the case in the First World War, women’s service clubs and community groups donated and raised funds for the Red Cross and other war charities. By the end of 1945, Indian bands officially had donated $23,596.71. A note found in Indian Affairs records indicated that many donations went directly to local organisations and that the ‘substantial donations of furs, clothing and other articles were made, the monetary value of which has not been calculated.’ One community in particular received international recognition for supporting the children orphaned by the London air raids. In 1941, the Old Crow Indians in the Yukon sent $432.30 to buy boots and clothing for these children. The British Press noted their generosity, and the Old Crow community continued to support various war funds in the subsequent years of the conflict.

As Allied fortunes worsened in mid-1940 with the fall of France and the Low Countries, the Canadian government again faced the difficult question of conscription. Late in the First World War, P.C. 111 had excluded status Indians from compulsory overseas services. This legislation was repealed before the Second World War broke out, and therefore the issue had to be dealt with once more. Parliament passed the National Resources Mobilization Act (NRMA) on 21 June 1940 to intensify Canada’s war effort. The legislation required Canadian men and women to register so that the federal government could rationally manage the country’s resources, but it assured Canadians that conscription would be for home defence only. Nevertheless, several Aboriginal leaders and band councils wrote letters and petitions to Ottawa, expressing their concern with compulsory enlistment and service. The issue was not about home defence; most Aboriginal communities were willing to contribute to the war effort. The choice of whether to serve overseas was one of principle. In Alberta, the Peigan chief and headmen ‘expressed the views that the Indians should not be liable for military service,’ the Indian agent explained in October 1940, ‘on the principles that as they were native born Canadians and at the treaties signed with them [it] was urged upon the Indians to settle down, cease fighting, and live on peaceable terms with the whites.’ Several tribal councils in north-western Ontario also passed resolutions denouncing conscription, and demanded that their Indian Agent ‘stretch out a long arm and halt all the functions of government.’ For their part, the Six Nations at Brantford, Ontario ‘strongly protested the imposition of 30 days military training upon the young single men of this reservation.’ Initially, groups of men were only conscripted for 30 days of training. As enlistments slowed throughout Canada, these mandatory terms extended to four months service and then for the duration of the war. This reflected Canada’s transition from a ‘limited liability’ war effort to a ‘total war’ footing.

Government promises and the wording of the NRMA reassured most status Indian men that they would not be sent overseas and many complied with domestic conscription. Several resisted its provisions by refusing to report to medical examinations or evading police attempts to track them down. These evasions became more common after a national plebiscite held on 27 April 1942 released the federal government from its obligation to limit conscripts to home defence. Bill 80 authorized conscription for overseas service if necessary. First Nations leaders raised issues of fairness. ‘Why should we be asked to go?’ chiefs from the Blood Reserve in Alberta questioned. They emphasized that, as wards of the government who did not have the right to vote, they should not be asked ‘to submit like children and take responsibility with those who are fortunate to be full citizens and subjects of the King.’ This injustice would only be corrected if they received the franchise. The government responded that Indians were liable for conscription like other Canadian men. In Quebec, an Aboriginal rights organization known as the ‘Protection Committee’ maintained that status Indians were exempt from conscripted service, citing their inferior status under the Indian Act and their sovereignty under the Royal Proclamation of 1763. The issue led to a confrontation between police and the Aboriginal residents who opposed conscription on the Caughnawaga (Kahnawake) reserve near Montreal. In northern Ontario, Indian reserve communities argued exemptions under the terms of the Robinson-Huron and Robinson-Superior treaties of 1850. When several objectors, who failed to register, went to court, the Department of Justice explained that ‘Indians, being British subjects, are subject to Section 3 of the National War Service Regulations, 1940 (Recruits).’ This remained the government’s official position for the duration of the war.

In practice, the enforcement of the NRMA proved nearly impossible, particularly in remote areas. The case of Edward Cardinal of Whitecourt, Alberta, typified the problems facing NRMA registrars. When the post office returned a notice ordering Cardinal’s medical examination prior to military training, the Edmonton registrar asked the postmaster why it had not been picked up. He replied that Cardinal frequented an area twelve miles north and only picked up his mail twice each year. Other Indians who pursued a trapping, hunting and fishing lifestyle were even more difficult to contact, and the registrar admitted that it was ‘practically impossible’ to locate many of them. In lower mainland British Columbia, for example, the Native peoples tended to treat the notices ‘with apparent indifference,’ according to the Vancouver registrar. This made administration very difficult, and therefore the government inconsistently applied the regulations regarding Aboriginal men. Furthermore, language barriers and persistent health problems on many reserves meant that many status Indians who registered were never compelled to serve. As a result, any success in conscripting Aboriginal peoples was limited at best.

By 1943, some of Canada’s volunteer soldiers found themselves in sustained operations in Europe. Henry Beaudry from Sheepgrass First Nations was a young man who left his reserve to work for a farmer in the spring saw a sign at the Post Office: ‘Join the army and see the world.’ He decided to do so. ‘I went to the post office and just … signed my name. That same evening I was in a train going to Saskatoon.’ After serving with the forestry corps in Scotland, he transferred to Saskatchewan Light Infantry and participated in the Sicilian and Italian Campaigns. ‘I was in the front all the way along,’ Beaudry recalled, ‘and we came to this place called Ortona, one of Hitler’s defence line. I was an attack gunner. I had a gun on the top of the hill and the town was kind of on the lower part.’ During the battle, Beaudry was hit by sniper fire. When he got out of hospital a month later, he transferred to the Princess Louise Dragoon Guards (a reconnaissance unit) that ‘used to go to in front of infantry to … cut off communications and supply lines.’ In one of their more harrowing tasks, they had to cross two canals to take a town. ‘They were pretty deep up to our necks you know. We had our guns up. My clothes were past these canals and when we got on the other side we were all ice it was so cold. Our clothes were all icy, we had cross two canals. One of my friends from Meadow Lake, Saskatchewan, he was a Métis, he got killed right beside me then we kept on going.’ Beaudry was again injured in hand-to-hand combat but kept on fighting. Pinned down in a building throughout the night, he faced a continuous stream of German grenades infamously known as ‘potato mashers.’ ‘They used to come around the floor you know by the time they reach us I used to throw them back to them and they explode,’ Beaudry reminisced. He ran out of ammunition by morning, and when the Germans captured the building he played dead. They prodded him awake and he was taken prisoner. Two officers questioned him a few days later. One had been to Saskatchewan a few years earlier and said ‘We are honoured to capture a Brave. You guys are the best fighters in the world. You’ve been fighting for 500 years, [and you’re] still fighting. Why do you come and fight? Them guys took all your country.’ Beaudry could not reply because he had told his captors that he did not speak English. He spent time in prisoner of war camps in Italy and Germany before participating in a two month long ‘death march’ in the spring of 1945. When he finally returned to England, he had to spend time in hospital to recover.

The main Allied invasion of Europe came in mid-1944. Raymond Anderson, from Sandy Hook, Manitoba, went overseas in 1943 with the 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion. He parachuted into France just before midnight on 5 June 1944 to set up the drop zone for the remainder of his battalion. ‘I was picked for this job and leading patrols because I was a Métis,’ Anderson explained, ‘and they thought my skills as a Métis, with an Aboriginal background, should be come very valuable.’ The following morning, D-Day, the 3rd Canadian Infantry Division landed at Juno Beach. Charles Bird recalled:

Early on the 6th of June … we got into these … Landing Craft Assault, now we were going into the real thing now… We were getting close, oh about a mile off the beach when the shells start coming. From the beach now they were shelling but they weren’t landing right here where we were in that boat. Then we hit the beach and there was a big pillbox right on the left of us a big in there. The gun was down and we figured we were all coming in on the beach now. When the big door opened at the front then the machine guns started. That was rough.… They bombed the beach before and there was a bomb that kind of hit the ground and five of us got into that hole there. Just got there and there was a wall about ten feet high, we just got to that when a grenade came flying in amongst us. Right in amongst us all you could do was just swing around and turn around so we swung around. That grenade exploded in there. One guy got pretty badly hurt I got in the leg. I got shrapnel in the leg….

George Myram of Edwin (Long Plain), Manitoba, remembers landing and ‘seeing the dead, the wounded and the suffering. I think that was the longest day of my life…. All these bombers coming over bombing, and artillery and the heavy artillery from the battleships just roaring and planes flying all over – some are on fire – and, fireworks. Like fireworks but this was for real, this was for victory.’ The liberation of Western Europe had begun.

The Canadian fighting in Normandy and Northwest Europe took its toll: 18,444 casualties in the Normandy Campaign. Canada was given a significant role in the ensuing pursuit of the retreating Germans through Belgium and the Netherlands. Harry Lavallee, a Métis from Stonewall, Manitoba, avoided the fate of several relatives who ended up at Hong Kong with the Winnipeg Grenadiers. He joined the Royal Canadian Ordnance Corps, and eventually served in Northwest Europe as a rifleman with the Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders. ‘We marched, marched and marched, but the first night going into the front line I nearly got killed [by] bombing,’ he remembered. ‘We walked to the front line so we had to go there and all of a sudden there were bombs coming all over and we had to dive for the ground and ended up going up into a trench, and that’s where I was nearly shot.’ He felt the breeze of shrapnel or machine gun bullets as they passed near his body. ‘If I’d have went over a foot or something I could have been split in half.’ George Myram also fought through Northwest Europe. He explained that ‘when there was a war on we knew you were going over there to kill or be killed but we still volunteered.’ They fought ‘with rifles and bayonets’ and ‘didn’t wait for the heavy guns to soften up the enemy or bombard a position before we went in. We went in, we fought our way in.’ By late November, the Canadian Army was deeply engaged in the clearing the Scheldt Estuary. Facing stiff resistance in difficult polder country, Canadian casualty rates quickly outpaced enlistments.

With much consternation, Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King decided in November 1944 to send NRMA conscripts overseas. As the first conscripts boarded ships for Europe, the Cabinet War Committee dealt with the unique case of Aboriginal service. In late December 1944, it decided that all Indians were liable for military service; Cabinet did not grant a blanket exemption as it had in the First World War. Indian Affairs could not find any references to conscription in the written texts of the treaties, but they did find cases where ‘exemption under treaty could be claimed with justification.’ Verbal promises were made to the Indian signatories of Treaties 3, 6, 8 and 11 that they would not have to fight in future wars. By 1944, at least 324 individuals from these treaty areas had already volunteered to serve overseas. The conscripts from these treaty communities who remained in Canada would only be expected to defend their homes in North America, and would not be compelled to serve overseas.

Officially, all other Aboriginal conscripts in Canada were liable for overseas service, but few if any of the 13,000 Canadian conscripts sent overseas in the Second World War were status Indians. In February 1945, Indian Affairs directed federal registrars not to call up Indians who spoke neither English nor French, not to issue orders to any Native person living in remote areas, and to record any Indian recruit deemed unacceptable to the army, regardless of his physical condition, as ‘Not Acceptable for Medical Reasons.’ This excluded most status Indian men who remained in Canada. Band council opposition and grassroots resistance to conscription continued, however, and tensions ran high. As a result, the government abandoned any concentrated attempt to conscript the status Indian population in the final months of the war. Officials decided to drop any further prosecution of Aboriginal men who had fought the registration process, and granted suspended sentences on all outstanding cases before the courts. Concurrently, Aboriginal volunteers fought on in Europe. Lawrence Martin fought with the Lake Superior Regiment along the Maas River and into Germany. He spent much of his time on half-tracks or clearing houses. “It was a dirty job,” he reminisced. “But somebody had to do it.” Alongside other Canadian and Allied soldiers, they celebrated Victory in Europe on 8 May 1945.

Cecil Ace, Ojibway from Aird Island, Ontario in the Canadian Army, reclining at left somewhere in Germany, the morning after the peace was signed.

“We went to Caen which we helped to liberate … We started our push and we moved up to the Falaise Gap ... We fought in the Scheldt Estuary also, a lot of fighting there [against] a pocket of Germans. [We] lost a lot of soldiers there … We were there quite a while in the Scheldt. We had a hard time there. The weather was so bad … cold [and] muddy … We had to dig [the guns] in all the time too. [And there were a lot of German 88s]. And then when we got to [the] other side were in Germany, then we really started to move … After that the war was just about finished … We could see big columns of Germans marching back home … and we were there to watch where they were going … That was it.” (Photo provided by Cecil Ace)

Although the conscription issue generated significant concerns during the war, it cannot be allowed to overshadow the important voluntary contributions made by Aboriginal peoples on individual and communal levels. Most of the 3,000 status Indian recruits served in the infantry. Similar to the structure found in the First World War there were no ethnic specific units formed. However there were many infantry battalions that had significant numbers of Aboriginal personnel, such as the Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry, The Calgary Highlanders, The Edmonton Regiment, The South Saskatchewan Regiment, The Hastings and Prince Edward Regiment, The Royal Hamilton Light Infantry, The Regina Rifle Regiment and The Royal Winnipeg Rifles. The skills that served them in peacetime were readily adaptable to infantry training. Books by Janice Summerby and Fred Gaffen provide additional biographical sketches of specific individuals and their wartime contributions, including courageous men who earned multiple decorations. Three anecdotes provide an introduction to their noteworthy achievements.

Charles Byce’s mother, Louisa Saylors, was a Cree from Moose Factory, Ontario. His father Henry Byce, a non-Aboriginal man from Westmeath, Ontario, had won both the Distinguished Conduct Medal and France’s Médaille militaire during the Great War. At his urging Charles joined The Lake Superior Regiment during the Second World War. On 21 January 1945, Charles was serving in the Netherlands. An acting-corporal at the time, he led a five-man group across the Maas River to capture German prisoners for intelligence. When the patrol landed it came under attack from three different enemy positions. Corporal Byce personally located two of them and silenced them with grenades. ‘As the patrol hurried across the dyke several grenades hurtled through the air towards them. Fortunately, they exploded harmlessly … but they did serve to reveal the location of two more enemy soldiers.’ In response, Byce ‘charged the German dug-out and into it hurled a 36 [the type classification] grenade,’ killing both the occupants. For his bravery he was awarded the Military Medal. Six weeks later, Summerby explains, during the battle for the Rhineland’s Hochwald Forest, Byce became one of 162 Canadians to win the Distinguished Conduct Medal during the war. His ‘C’ Company was under severe fire and sustained heavy casualties, including every officer. Acting Sergeant Byce took over the command and ‘fought as long as he could; then gathering what few men he was able to find about him he made his way back through the bullet-strewn escape alley.’ Byce personally covered the retreat, sniping at the enemy infantry to prevent them from overrunning his men. His citation reads:

The magnificent courage and fighting spirit displayed by this N[on] C[ommissioned] O[fficer] when faced with almost insuperable odds are beyond all praise. His gallant stand, without adequate weapons and with a bare handful of men against hopeless odds will remain, for all time, an outstanding example to all ranks of the Regiment.

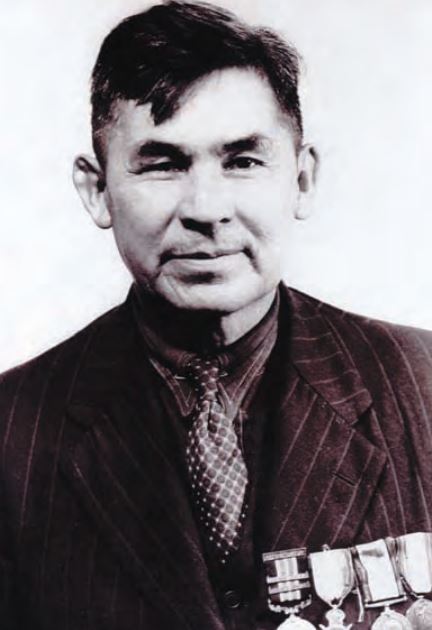

Lieutenant David Greyeyes, Cree from Muskeg Lake, Cree Nation, 1st Infantry Division Support Battalion (The Saskatoon Light Infantry), 21 September 1943. (Department of National Defence)

Department of National Defence public affairs noted that Greyeyes enlisted in 1940 and attained the rank of Sergeant overseas before being returned to Canada in February 1943 for officer training. Returning to Britain as a Lieutenant in July 1943 “he was believed to be the only officer of Indian blood who is serving in the Canadian Army overseas”. This image was used for recruiting during and after the war. The Winnipeg Tribune caption identified “Councillor Harry Bull, of the Piagut Indian community near Regina who lost a leg at Vimy Ridge in the Great War ‘giving his blessing. Stephen Reid recalled later that his mother ” the first Indian girl to enlist in Canada…was accepted into the CWAC as a cook and was posted overseas to England in the Laundry Unit”. Two other brothers also served.

Private Mary Greyeyes, Cree from Muskeg Lake,Cree Nation, Canadian Women's Army Corps. (Library and Archives Canada (PA-129070))

Charles Byce was one of the few Canadians who won both the Distinguished Conduct Medal and the Military Medal.

During a long and distinguished military career, Oliver Milton Martin, a Mohawk from the Six Nations of the Grand River, made his mark in both the army and the air force. Martin attained the highest rank ever by an Indian, ending his wartime service as a brigadier. Born in 1893, he joined The Haldimand Rifles as a bugler in 1909. Six years later, he volunteered for the Canadian Expeditionary Force with his two brothers. As a lieutenant he spent seven months in France and Belgium before becoming an observer with the Royal Flying Corps in 1917. The following year he earned his pilot’s wings. Between the wars he taught school and commanded The Haldimand Rifles from 1930 until 1939, and at the outbreak of war he was promoted to colonel. The following year he was promoted to brigadier and subsequently commanded the 14th and 16th Infantry Brigades on the West Coast. In October 1944, at the age of 53, Brigadier Martin retired from active service. He eventually became a magistrate and a proud spokesperson for the Aboriginal cause.

Perhaps the best-known Aboriginal soldier of the 20th Century is Thomas George Prince, who distinguished himself in battle in Italy and in France during the Second World War. Prince was born into a large family in Manitoba, and began his military career as a sapper with the Royal Canadian Engineers. He trained with the 1st Canadian Special Service Force and became a paratrooper. The ‘Devil’s Brigade,’ as the Germans came to call the Special Service Force, took Prince to Italy in 1944. On one occasion, he was ordered to maintain surveillance at an abandoned farmhouse approximately 200 metres from the enemy lines. Connected to his battalion by some 1,400 metres of telephone wire, Prince radioed updates about artillery placements. When the communication line was cut by enemy shelling during his watch, Prince put on civilian clothes and pretended to be a farmer hoeing his field. Slowly making his way down the line he fixed the severed line and continued his reports. He repaired damaged lines a number of times in this manner during his 24-hour posting. With the information he provided, four German positions were destroyed and Prince earned the Military Medal. Six months later, Prince’s unit was stationed in Southern France. He and another soldier went behind enemy lines to locate gun sites and an encampment area. They then walked back 70 kilometres to make their report. For this bravery Prince received his recommendation for the Silver Star – an American decoration for gallantry in action. After the fighting was finished, King George VI summoned Prince to London and awarded him the Silver Star and ribbon on behalf of the President of the United States. There were only 59 Canadians awarded the Silver Star, and only three also wore the Military Medal. Prince was in elite company.

North American Indian Brotherhood convention, Ottawa, 1945 (Kahnawake Cultural Centre)

Francis Pegahmagabow, Anishinabeg of Parry Island, during a 1945 visit to Ottawa. (Canadian Museum of Civilization (#95292-3))

Following the Second World War, Canada as a nation embarked upon an unprecedented period of economic growth, prosperity and social reform, as the government implemented the features of the modern welfare state. As had been the case following the First World War, newly returned Aboriginal veterans and their supporters were active in promoting the rights and interests of their people through various means. Francis Pegahmagabow was emblematic of those veterans who assumed leadership roles within their respective communities during the interwar and post-war years. Pegahmagabow served as a sniper with the 1st Canadian Infantry Battalion during the First World War and was awarded the Military Medal for bravery three times. Treated as an equal by his fellow soldiers, he was disillusioned upon his return to the Reserve where he was treated as a second-class citizen. He would champion aboriginal rights through a peaceful campaign of letter writing and court challenges for the rest of his life. He presided as band Chief from 1921-25 and served as a band councillor from 1933-36. In 1943, he was named Supreme Chief of The Native Independent Government, an early native rights group. Other groups such as the League of Indians of Canada (led by another Great War veteran, F.O. Loft) pushed for the recognition of aboriginal rights. The North American Indian Brotherhood pictured at a convention in Ottawa in 1945 was another of these organizations.