Transforming Relationships, 1815-1902

The end of the War of 1812 marked the end of an era in Canadian history. From 1815 onward, Aboriginal peoples in the Eastern portions of the country quickly lost their military and political power beneath a tide of immigration. The 60,000 European inhabitants of Upper Canada prior to 1812 had exploded to more than 400,000 by the 1830s, as disease continued to whittle away at the indigenous population. This demographic reality gave the European residents the confidence to disregard the military potential of tribal or national contingents of Aboriginal warriors. Instead, the British colonial authorities began to look at Aboriginal communities as administrative challenges rather than as sources of potent military allies. The 19th Century brought profound alterations in the relationship between the British, and later Canadians, and Aboriginal peoples.

Anishinabeg men at Coldwater (Lake Simcoe area) in 1844.

Several hundred Anishinabeg at numerous locations across Upper Canada – including groups to the north and east of Toronto – mobilized in support of Crown forces on many occasions between 1830 and 1840. (Watercolour by Titus Hibbert Ware (Metropolitan Toronto Library T 14386))

Nicholas Vincent Isawahoni, a Huron Chief, holding a wampum belt, 1825.

Even if colonial or subsequent Dominion governments were unwilling or unable to do so, Aboriginal groups steadfastly retained the knowledge of their unique relationship with the Crown during peace and war throughout the 19th century into the 20th century and beyond. (Library and Archives Canada (C-38948))

Another important historical process underway was the progressive expansion of Imperial authority and colonial settlement into the west and the north. This occurred gradually through the fur trade under the auspices of the Hudson’s Bay Company. The company functioned as an aloof and somewhat indifferent governing agency for the territories it had been granted as a trade monopoly – Rupert’s Land and the Northwest Territory (essentially most of Western and Northern Canada). In reality, Aboriginal peoples lived as they wished, subject only to the political, social and military realities of the fur trade. Through the latter half of the 19th Century, this distant presence was increasingly replaced by colonial settlement on the Pacific coast and in the Prairies. More significant for the Aboriginal peoples of the west and north was the extension of state authority and administrative control to the region after 1869. At that point, the Hudson’s Bay Company handed over control of Rupert’s Land to the new dominion government in Ottawa, thereby bringing more than a hundred thousand Aboriginal people under the wing of the state. By the dawn of the 20th Century, government authority over indigenous peoples was steadily tightened from the Atlantic to the Pacific.

Consolidation of the British, and later Canadian, grip on the northern part of the continent occurred gradually, and recast the indigenous population from independent allies to legal wards of the Crown. Treaties between Aboriginal nations and the imperial/colonial authorities were critical to this transformation. The treaty process grew out of the Royal Proclamation in 1763, and became prevalent in the wake of the American Revolution as Imperial authorities sought land from the Mississaugas on which to settle the United Empire Loyalists, including indigenous Loyalists like the Six Nations. Treaties were important for both parties as a means to resolve disputes over land and resources before they could escalate into conflicts between Aboriginal people and settlers. The early land cession treaties were usually one-off arrangements with land exchanged for a lump sum of goods and/or money. The form of the agreements evolved through the first half of the 19th Century, however, coalescing in the Robinson-Huron and Superior treaties with the Ojibwa (Anishnabeg) in 1850. Based on this model subsequent treaties would generally provide for an extinguishment of what is now termed ‘Aboriginal title’ to a wide tract of traditionally occupied land. In exchange, the Crown agreed to pay small annuities to each member of a band in perpetuity, guarantee fishing and hunting rights to all land surrendered, and set aside a piece of land to be held in common for each band as a reserve. As the government concluded the eleven numbered treaties across the Northwest from the 1870s to the early 20th Century, additional obligations were conceded to adept Aboriginal negotiators including government-supplied medical care, education and support in the transition to agriculture.

The movement onto Indian reserves symbolised the shift from free peoples to administered wards, though in principle the reserve was intended as a protective measure.

Lone canoeist on the St. Lawrence River, with the Windmill and Fort Wellington in the background, c. 1840.

Riverine and inshore smallcraft operations were a First Nations speciality. A principal employment of First Nations militias in 1837-38 was to patrol the water frontiers of Upper and Lower Canada. In addition to giving advance warning of suspicious activity, they were useful in apprehending deserters of British Army garrisons. While such deserters were a perennial problem for military commanders, the bounties paid for their return provided casual but steady income to First Nations located near British outposts. (Library and Archives Canada (C-11863))

In practice, reserves were turned into social laboratories where the language and values of Christianity and the Western world were to be inculcated into the inhabitants. In 1876, the transition to administered peoples was consolidated in a single piece of Canadian legislation, the Indian Act. Thereafter, Canadian Indian administrators became increasingly forthright in pressing the agenda of assimilation as the logical solution to what was termed the ‘Indian problem.’ Yet though the relationship between Aboriginal peoples and the Euro-Canadian state had altered profoundly since 1815, a military connection persisted.

Rebellions

This military connection was renewed in 1837-38, when the majority of Aboriginal peoples in Upper and Lower Canada chose either to remain neutral, or to actively support the British efforts to suppress the Rebellions in both provinces. The outbreak of those violent political protests followed years of increasingly inflammatory rhetoric from small but vocal minorities of agitators within the respective provinces. In each instance, there were calls by radical reformers, labelled patriotes in Lower Canada, for the elimination of patronage-riddled, nondemocratic administrative systems and their replacement with American-style republican governments. The clashes in Lower Canada ultimately proved the more violent affairs, in part because of the added religious and ethno-linguistic dimensions that were not present in Upper Canada.

The first overt act of the Rebellion in Lower Canada drew the Caughnawaga (Kahnawake) Mohawk into the fray on 4 November 1837, when a group of patriotes, 75 strong, under the command of Joseph-Narcisse Cardinal, came in search of weapons. In his Rebellion: The Rising in French Canada 1837, Joseph Schull recounts what happened:

An Indian woman, chasing a stray cow, had seen the approach of the party and had run to inform the chief. She found him at early mass, and there had been a prompt exodus from the church. By the time the patriotes entered the road to the village, the woods on either side were thick with Indians. The chief appeared alone, grave and inquiring. What was the purpose of this unannounced visit? He was gravely informed by Cardinal of the patriotes need of weapons. By what authority, the chief asked, was such a request made? ‘By this,’ Cardinal replied, whipping a pistol from his pocket and pointing it at the chief’s head.

It was his last warlike gesture. The chief’s hand shot out to knock the pistol aside. A blood-curdling war-whoop shattered the Sunday calm, and a hundred armed braves were around the patriotes. Of the seventy-five who came, only eleven escaped, and the chief was prompt in his disposition of the others…. By mid-morning the warriors from Caughnawaga had crossed over to Lachine to deliver sixty-four rebels to the Lachine volunteer cavalry….

Indian village at St. Regis.

Iroquois and other First Nations groups – including those at St. Regis (Akwesasne), Kahnawake, and Kanesatake – also wishing to ensure the stability of Crown government, likewise supported the Loyalist cause during the Rebellions in Lower Canada. (Watercolour by W.H. Bartlett (McCord Museum collection, McGill University))

Over the next weeks, violence in Lower Canada escalated, beginning in the streets of Montreal with running brawls between gangs of patriotes, known as Les Fils de la Liberté, and the loyalist Doric Club. The Riot Act was read and British troops quickly restored order, but civil unrest was growing in the countryside and open conflict seemed imminent. On 16 November, the authorities issued warrants for the arrest of 26 patriote leaders. British regulars clashed with rebels in the first major engagement at St. Denis on 23 November. Though initially rebuffed, the British soundly defeated a patriote force at St. Charles two days later and in mid-December thrashed a rebel force at St. Eustache, effectively ending the Lower Canadian rebellion only a week after that in Upper Canada had begun. Such as they were, the principal incidents (clashes would be too strong a word) in Upper Canada were the laughable encounter of rebels and loyalists at what is now the vicinity of Yonge and Dundas Streets in Toronto. There, rebels under the command of William Lyon Mackenzie marched south to take control of the provincial capital in early December. A tragic comedy followed: both sides fled from the initial exchange of fire, before skirmishing around Montgomery’s Tavern (a few kilometres further north) resulted in the deaths of a dozen rebels and the wounding of twice that number. Elsewhere in Upper Canada the Rebellion played out in a number of relatively minor and brief episodes, including: the rapid dispersal (without any fighting at all) of the London District rebels; the rebel seizure of Navy Island, in the Niagara river; the so-called Battle of the Short Hills, at St. John’s on the Niagara escarpment west of Thorold; the capture and burning of the American steamer Caroline, which had been supplying the Navy Island rebels, by white loyalists; and abortive raids on Pelee Island and Windsor.

The government expected the support of Aboriginal communities in the crisis. John Macaulay, civil secretary for Upper Canada, circulated an order in November 1838 that directed colonial officials:

The extensive organization of a force within the U.S. Frontier for the purpose of invading their [sic] Province having become fully known to the Lt. Governor I am directed to request, that you will hold the Indians in your neighbourhood in readiness to take to the field & act with promptitude& effect under your command on the first notice, which you may receive of actual invasion by a foreign enemy or of insurrection in expectation of foreign aid, in any part of the province.

Understandably, not all Aboriginal peoples were that keen on fighting the white man’s battles. Disciples of Pazhekezhikquashkum at the St. Clair Mission (present-day Sarnia, Ontario) told their people:

… we consider it best to spread our matts to sitdown & smoke our pipes and to let the people who like powder & ball fight their own battles. We have some time ago counselled with the Indians around us & we are all agreed to remain quiet and we hope that all the Indians will do so, as we can gain nothing by fighting but may lose everything … Should such as are … foolish be induced to commence war on the whites of any party, we should all be more hated by the whites than we are now. We would just observe that we cannot be compelled to go & fight for any party, we mention this fact in order that should you be called on you may know that you are free men & under the control of no one who has authority to make you take up arms.

Nevertheless, some Loyalists feared that even if the Indians did not join the rebels they might rise on their own behalf. Rumour was rife. ‘A report has reached us that 400 Indians had come down on Toronto and slaughtered a number of the inhabitants … this seems to be unfounded,’ diarist Catherine Parr Traill wrote on 7 December.

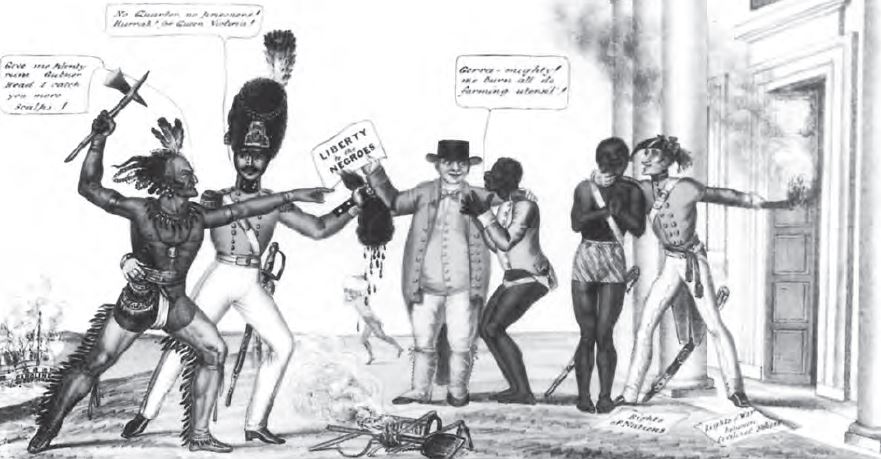

“Give me plenty rum, Gubner Head”

Foreseeing the likely outcomes for their respective peoples in the event of a reform seizure of power – including possible annexation by the U.S. – First Nations and Blacks were willing to support the continuity of the Crown government in Upper Canada during the rebellions of 1837-38. In so doing they became the subject of racist attacks by reform propagandists. (Library and Archives Canada (C-40831))

In fact, most Aboriginal people preferred the existing government and were fearful of effects that an American style republic might have on their status and well-being. As a result, there were numerous examples of Aboriginal contingents offering their support to British authorities and loyalist militia commanders in both the Canadas. A day or so before the fight at St. Eustache, when it still seemed that there might be much fighting to be done, about 200 Caughnawaga Mohawk joined loyalist forces around Montreal and Lachine. ‘Every Warrior in Caughnawaga was crossing to join the Lachine Brigade,’ recalled John Fraser, one of its white members. ‘A cheer of welcome from the … band of Volunteers greeted the arrival of the Indian Warriors.’ Grand River Iroquois, under William Johnson Kerr, and Tyendinaga (Deseronto) Mohawks, under John Culbertson, helped suppress both domestic rebels and American-based ‘Patriots.’ Kerr proudly reported that, ‘the Indian Warriors turned out with alacrity, and joined their Brethren the Militia in defence of the Country, its laws and institutions, at a period when there were no regular troops in the Country … to their honor be it spoken, they have neither Indian Radicals nor Indian Rebels amongst them.’ Tyendinaga offered to provide enough men to form a rifle company, although whether it was actually formed is unclear. Anthony Manahan, a militia officer, wrote to Colonel James FitzGibbon explaining that ‘a band of Indians here with Chief John Culbertson … have expressed a wish to join my Regiment as a Volunteer Rifle Company under Culbertson as their captain …. I beg you think favourably of the Indian Rifle Company. Such a company will do more than a Regiment of Regular Infantry to reduce the turbulent, by the fears they entertain [of Indian warriors].’

Sir George Arthur, who succeeded Francis Bond Head as the lieutenant-governor of Upper Canada, subsequently wrote to Lord Glenelg, the Colonial Secretary in England, explaining and justifying the employment of Aboriginal warriors:

In more than one instance since last Autumn have the Indians been called out in defence of the Country. They furnished a large force to protect the Niagara Frontier last winter, when it was menaced by the armed assemblage of Canadian Refugees, and American adventurers, who had taken possession of Navy Island; and on that occasion, as well as on others when their services were required by my predecessor, their conduct was perfectly unexceptionable. In employing them in the month of June last, I had it for my Chief object to cut off the communication between the mixed band of brigands and insurgents, who were in arms at the Short Hills, and the disaffected portion of the London and Talbot Districts, and to intercept all fugitives. The Indians were thus employed on a duty for which they were peculiarly well qualified ….

The Warriors of these tribes, who promptly obeyed my summons, were under the guidance of human leaders who readily enforced my earnest injunctions for the maintenance of the Strictest order and a scrupulous observance of the merciful rules of civilized warfare ….

27 soldiers and nearly 300 rebels were killed in the Lower Canada campaign, and far fewer in the Upper Canada rebellion. In all, more than a dozen rebels went to the gallows, with dozens more banished to the British penal colony in Van Diemen’s Land (now Tasmania) off the south-eastern shore of Australia. All of those men, as well as some of the key leaders that had escaped to the United States, were eventually pardoned. In the end, Aboriginal warriors saw little combat, but their aid was still sought by British and loyalists alike. Their military relationship was reaffirmed, albeit modestly, by these failed Canadian rebellions.

Militia

Despite the relative peace and stability in Canada through the rest of the 19th Century, a military dimension was never absent. It was evident in the treaties that the Crown negotiated with the Aboriginal peoples of the west. They were encouraged to cease all fighting with Europeans or other Aboriginal nations and to live in peace. Importantly, several Aboriginal groups expressed concern that signing a treaty would obligate them to being compelled to fight for the Crown. Crown negotiator Alexander Morris assured the Saulteaux at the negotiation of Treaty 3 (also known as the North-West Angle Treaty) in 1873 that ‘The English never call the Indians out of the country to fight their battles.’ Similarly at Fort Pitt in 1876, the Cree were told, ‘In case of war you ask not to be compelled to fight. I trust there will be no war, but if it should occur I thing [sic] the Queen would leave you to yourselves. I am sure she would not ask her Indian children to fight for her unless they wished.’ These verbal assurances would prove significant in the conscription crises of the World Wars of the 20th Century. At the time, such examples demonstrated that the military capacity of indigenous warriors, though latent, had not become irrelevant, either to Aboriginal peoples or to the state.

Coloured tin type portrait of Cornelius Moses

Cornelius Moses was one of the Grand River band of Delaware who organized a Home Guard for local defence at the time of the 1866 Fenian incursion at Ridgeway in Canada West. Their subsequent efforts to formally incorporate as a volunteer Militia company would, however, remain unsuccessful for another quarter-century. In the mid-19th century, colonial officials in some regions were initially suspicious of Natives who sought to organize themselves militarily, although the Confederation-era volunteer militia movement did have its supporters and patrons within specific communities having strong United Empire Loyalist ties. These surfaced again during the South African War and the First World War, with calls for units composed entirely of Native Canadians. (J. Moses collection.)

But neither the imperial nor the Canadian government formalised a role or structure for indigenous people in the Canadian defence establishment during the 19th Century. By 1855 the old, unpaid, Sedentary Militia had fallen into desuetude. The government of the Canadas – Upper and Lower Canada had been re-united as Canada East and Canada West in 1840 – felt it necessary to introduce a new Militia Act, retaining the principle of universal unpaid military service which could be called upon in times of emergency. The Act also creating a new Active or Volunteer Militia, 5,000 strong, who would be equipped by the government and paid to train ten days a year. Faced with the threat of American expansionism, the Canadian government soon doubled the authorized strength. Yet, outside a few local instances of small Aboriginal militia units, there was no corollary in Canada to the American example of segregated indigenous regular units or scouting units. In part, this was because the lesser incidence of conflict in the Canadian West did not create the same need for such forces.

The very structure and function of the militia in Canadian society during the Victorian Age also worked against a place for Aboriginal warriors. After the reorganisation and expansion of the Active Militia, service became increasingly fashionable and the new militia units soon achieved considerable social status as exclusive men’s clubs. They competed with each other in drill and shooting. Often, men were expected to donate their pay to the unit, to be used for purchasing trophies or uniform adornments, or paying for regimental dinners. By 1862 the Maritime colonies had followed suit, ‘so that there were soon 18,000 of them happily parading in their spare time in towns and cities all across British North America.’ The key words in that quotation are ‘towns and cities.’ There were a few rural units, with companies based in different villages, but most were established at battalion strength in the larger centres of population where it was easier to gather together men. This urban-elite organisation tended to marginalise Aboriginal peoples whose communities were mostly rural in nature. It also demonstrated the beginning of a shift away from prior practices of seeking Aboriginal men as generalist fighters, especially in tribal or national contingents. This process would be evident in the Prairie West during the efforts of the Métis people to exert some influence over Canada’s western expansion in the 1870s and 1880s.

Métis Resistance

Not all dealings between the Canadian state and Aboriginal peoples in the 19th Century were amicable. In 1869-70, as the young government of Canada prepared for the handover of Rupert’s Land and the Northwest to its jurisdiction, it neglected to consult the existing inhabitants, either the First Nations or the mixed-heritage Métis community in the Red River region. Under the leadership of a young, dynamic man named Louis Riel, the residents of Red River blocked the transfer of power to ensure the protection of their individual and collective rights to their religion, language and land, as well as to secure a political role in any new provincial government. The Métis declared a provisional government and seized Fort Garry to demonstrate their determination and force the Canadian leadership to negotiate. Riel and his colleagues secured guarantees to create a new province of Manitoba. Canadian authorities, however, dispatched an expeditionary force to Red River. Under the command of British regular officer, Colonel Garnet Wolseley, the Red River Expedition was sent to assert Crown authority. Mohawks, Plains and Swampy Cree, and a considerable number of Ontario and Quebec Métis, were among the nearly 400 civilians contracted to transport the troops and their equipment.

The presence and participation of experienced Aboriginal boatmen and voyageurs in the ranks of the Expedition’s transportation corps was fundamental to its successful arrival in Manitoba. Wolseley had become familiar with the capabilities of Kahnawake Mohawk boatmen in 1862 when, as a lieutenant-colonel, he had been assigned as an instructor to the Militia officers’ training school at La Prairie, across the St. Lawrence from Montreal and adjacent to the Kahnawake reserve. Now he called upon Simon Dawson, a Dominion land surveyor and civil engineer, to make the transportation arrangements for the expeditionary force, including the recruitment of some 140 Indian and Métis voyageurs.

Left: Archibald acknowleging Riel’s and Royal’s offer of Métis assistance against the Fenians, 8 October 1871. (Glenbow Museum (NA 22-33))

Right: An unidentified Métis hunter on horseback c. 1890. (Photograph by R. Randolph, Glenbow Museum)

A formal offer of Métis assistance in countering the Fenian threat in Manitoba in 1871 was tendered under the political leadership of Louis Riel. Irregular units of armed Métis horsemen acting as mounted infantry were mobilized for local defence in small units based on methods adapted from Métis buffalo hunt, with elected “captains” leading mounted squads of ten “soldiers” each. This same organization was used again by Gabriel Dumont during the Northwest rebellion in 1885. Other tactics included the construction of camouflaged rifle pits dug beneath barricades of encircled Red River carts. Such tactics were successful in defeating neighbouring First Nations opponents with whom the Métis were in competition over access to the same dwindling buffalo herds. The battle with Dakota Sioux at the Grand Coteau in July 1851 is the best documented example of this.

The successful movement of some 400 British regulars and 700 militiamen with all their necessary equipment and supplies from Collingwood, on Georgian Bay, to Fort Garry – without the loss of a single man – was a logistical triumph. During the arduous voyage, the Expedition traversed 47 portages and ran some 82 kilometres of rapids. The soldiers had nothing but praise for their indigenous chauffeurs. Lieutenant Henry Riddell of the British 60th (The King’s Royal Rifle Corps) noted that: ‘Fortunate was the officer who secured for his boat the skilful Iroquois, the finest boatmen in Canada.’ The expeditionary force was divided into 21 ‘brigades,’ each consisting of about 50 men. Each boat carried ten or 12 soldiers, with a voyageur bowman and steersman. There were also three canots de maître and a number of smaller birchbark canoes manned by voyageurs. One of these canoes, manned by Aboriginal paddlers, was Colonel Wolseley’s personal choice of transport. In it he could move rapidly from one end of the line of march to the other. His experience with these Aboriginal voyageurs would lead to his request for their services years later in the Nile Expedition.

By the time the Canadian force arrived in Red River, negotiations between the Métis and Canada were completed and Riel had fled into hiding. At the order of Riel’s provisional government, a pro-Canadian Orangeman by the name of Thomas Scott had been executed, and many Protestants in Ontario howled for Riel to be hanged. Although the Métis continued to have their grievances, even after the creation of Manitoba in 1870, they still turned out in force the following year to oppose a potentially serious threat to the new province. There was, as yet, no organized militia to resist an incursion from the south that materialised in 1871. Usually labelled as a Fenian raid (the Fenians were an Irish American brotherhood created to secure Irish independent from Britain), this attack was hardly that because the council of the Fenian Brotherhood never approved it. It was inspired and organized by William O’Donahue, the one-time treasurer of Riel’s short-lived provisional government, and was intended to de-stabilize Canadian and British control over the region. He managed to secure the support of a number of Fenians, including ‘General’ O’Neill (the victor at Ridgeway) giving the movement some status.

O’Donahue, of course, was relying on Red River Métis dissatisfaction with Ottawa. The Métis, however, after due deliberation, tendered a formal offer to assist the Canadian government in quashing any Fenian challenge. In a formal declaration of loyalty, the Métis parishes of the Red River decided that ‘… being subjects of Her Majesty Queen Victoria, we believe it our duty to obey her, [and] that having received, through her representative, orders to meet to fight the Fenians, we do so and are resolved to follow the order which competent authorities shall give.’ Irregular units of Métis horsemen, acting as mounted infantry, mobilized in small units and adopted methods from the buffalo hunt, with elected ‘captains’ leading their mounted squads or platoons of ten ‘soldiers’ each. ‘Generally I hear it said that the English are really frightened,’ reported a St. Boniface clergyman. ‘If the Fenians really number 1,500, only the Métis horsemen can stop them. The English have said that the Métis count for nothing; now they are going to find out [what they do count for].’ The actual raiding force, perhaps 75 strong, crossed the border on 6 October, occupied the Canadian Customs House and looted a Hudson’s Bay Company store. The raiders immediately dispersed and fled upon hearing news of approaching American troops. American authorities, and some by the Fort Garry militia, subsequently arrested many of them, and Métis volunteers captured O’Donahue himself. All the Canadian prisoners were subsequently handed over to the Americans, though none of the raiders were ever brought to trial.

In the years that followed, the Métis began to leave Manitoba, partly pushed out by the tens of thousands of new settlers and partly drawn westward in pursuit of the shrinking herds of buffalo. Temporary camps in the Qu’Appelle and Saskatchewan valleys gradually evolved into permanent settlements, where Métis families reestablished themselves on farms in their traditional French style of long, narrow plots. Once again they petitioned the federal government to officially confirm their possession of these lands and for greater economic and political autonomy, but they met with little success. Frustrated, and under increasing economic strain by the early 1880s, the Métis and some European residents of the region decided to appeal to their old hero, Louis Riel. At this time Riel was a school teacher in Montana, and he agreed in November 1884 to return and help lead the Métis. He had spent much of the last decade in asylums and in exile in the United States, but he remained a dynamic and charismatic individual.

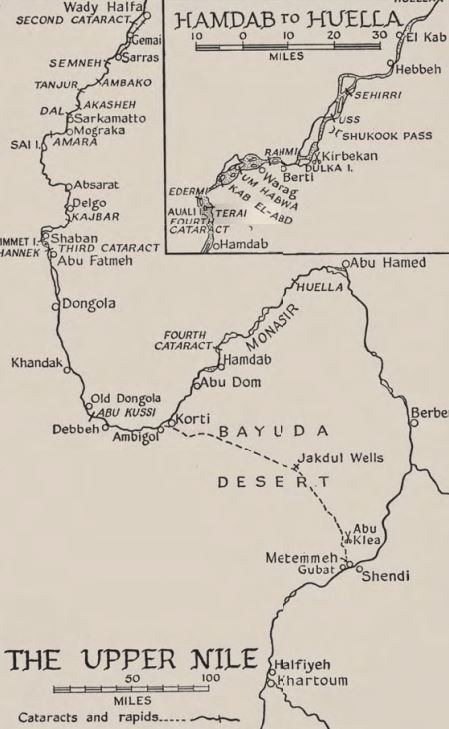

Map: The North-West campaign of 1885 (A military History of Canada. Desmond Morton (Department of National Defence))

Unable to gain a hearing from the Canadian government, Riel sought to follow a similar course to that of 1869-70, seizing arms and declaring a provisional government to undertake negotiations with Ottawa. Unfortunately in this instance, the process provoked violent conflict almost immediately. Riel and a force of Métis horsemen, seeking weapons and ammunition from the store in Duck Lake, collided with a column of North West Mounted Police and mounted volunteers out of Fort Carleton. The ensuing clash was a clear Métis victory, but thereafter, events rapidly snowballed beyond Riel’s abilities to control them. Unlike 1870, the federal government was not constrained by any legal ambiguities over sovereignty in the Northwest. Furthermore, the existence of telegraph lines and a near-complete rail link to Ottawa meant that information and troops could travel very rapidly to respond to the crisis. The Wolseley expedition in 1870 had taken months to complete their arduous voyage to Manitoba. In 1885, the lead elements of the Canadian militia were marching north from Qu’Appelle, behind Aboriginal scouts, within two weeks of the Duck Lake clash. Despite the crafty military leadership of Gabriel Dumont, the roughly 350 experienced Métis fighters concentrated in Batoche could not withstand the onslaught of the inexperienced, but much larger, Canadian force under the command of the British Major-General Frederick Middleton. The defeat of the Métis at the Battle of Batoche in May 1885, and the surrender of Riel a few days later, effectively broke the resistance, though it was not the only fighting to occur.

Left: Dog Child, a North West Mounted Police scout, and his wife, members of the Blackfoot Nation, c. 1890. (Library and Archives Canada (PA-195224))

Right: Métis men working for the Boundary Commission 1872-74: the 49th Rangers (Manitoba Archives (N14060))

During the westward and northward expansion of Dominion government, paramilitary organizations like the North West Mounted Police and the British North American Boundary Commission routinely engaged local Aboriginal people, both men and women, as civilian scouts, guides, trackers, outfitters and translators. The selfstyled “49th Rangers” composed of Red River Métis, provided an armed mounted escort to Boundary Commission surveyors in 1872-1874.

There were several skirmishes between Mounties, the militia and some of the Plains First Nations in the region. It is important to emphasize, however, that most of the Aboriginal population in the Prairies wanted no part in what they saw as a Métis adventure. Although Riel claimed to speak in their interests and the level of anger and despair among the Plains peoples was high, prominent Plains Cree and Assiniboine leaders like Big Bear, Poundmaker, Little Pine and Piapot had spent years working for a political resolution to their treaty grievances with the federal government. Similarly, the powerful Blackfoot Confederacy of what is now southern Alberta chose to honour its treaty commitments and remained aloof from the hostilities. Had all of the estimated 25,000 to 35,000 First Nations people living in the region (as opposed to roughly 2,000 Euro-Canadians) thrown their weight behind Riel and the Métis, the Canadian government might have been faced with a military situation beyond its resources. As it turned out, some Plains Cree under Big Bear, Poundmaker and other chiefs became involved in the fighting, usually incited either by warlike elements of their own population (Frog Lake Massacre) or by having to defend themselves from attacks by Canadian militia (Cut Knife Hill and Frenchman’s Butte). This was the exception rather than the rule: as Blair Stonechild and Bill Waiser demonstrate in their book, most remained ‘loyal till death.’

Most Métis communities also stayed clear of the fighting. The dominion government recruited units of mounted Métis riflemen and scouts from other regions to patrol the frontier with the United States, to guard the lines of communication and transport, and to act as security against cross-border arms smuggling and the possible movement of Métis or Indian reinforcements in support of Riel. Jean Louis Legare, originally from Quebec, was the chief resident trader for the Hudson’s Bay Company in the Wood Mountain area. He explained to Edgar Dewdney, the lieutenant-governor of the North-West Territories, that the Métis of Willow Branch and Wood Mountain were ‘in a starving condition [and] that they wished to remain there, so as not to be implicated in any way with the rebellion, and that they would be glad of any employment’ that might give them some relief. Thus, as would be the case in the 20th Century, economic necessity was often one of the premier motives motivating Métis and other Aboriginal involvement in military or paramilitary undertakings with the Canadian government. The North West Mounted Police found this arrangement perfectly satisfactory, since the Métis patrols ‘fulfilled the double purpose of finding work for idle hands to do, and having the country thoroughly watched.’

Métis also served as individuals in primarily non-Aboriginal militia units. Indeed, one of them served in the three-man patrol to whom Riel surrendered after his defeat at Batoche, according to Harvey Dwight, the American-born general manager of the Great North-West Telegraph Company’s cable to Ottawa:

Riel was captured today at noon by three scouts named Armstrong, D.H. Diehl and Howrie four miles north of Batoche’s [sic]. The scouts had been out in the morning to scour the country, but these three spread from the main body, and just as they were coming out of some brush on an unfrequented trail leading to Batoche’s they spied Riel with three companions. He was unarmed but they carried shot-guns…. No effort was made on his part to escape and after a brief conversation in which they expressed surprise at finding him there, Riel declared that he intended to give himself up. His only fear was that he would be shot by the troop…. He was assured of a fair trial, which was all he seemed to want …. To avoid the main body of the scouts Riel was taken to a coulee near by and hidden while Diehl went off to corral a horse for him.

Thomas Hourie (not Howrie) was a Métis serving with French’s Scouts attached to Middleton’s column. Whether Riel’s trial was fair is still subject to intense historical debate, but he was found ‘guilty’ at the time and was hanged for high treason. Gabriel Dumont, Riel’s adjutant and military commander, fled to the United States.

Left: Métis man, wearing a decorated jacket, who was a scout for the North West Mounted Police c. 1885. (Photograph by Fred A. Russell, Kalamazoo Public Museum)

Right: French and his men (Library and Archives Canada (C-18942))

Local Métis and First Nations support for Louis Riel and his followers during the 1885 Northwest Rebellion was not complete. Specially raised units of mounted Métis riflemen and scouts, including the Wood Mountain Scouts attached to the North West Mounted Police (left), were recruited by the Dominion government to patrol the frontier with the United States, and to guard the lines of communication and transport. Thomas Hourie, a Métis serving with French’s Scouts (right) in Middleton’s column, was one of three civilian trackers credited with the actual apprehension of Riel. Prarie First Nations leaders like Crowfoot chose to respect the spirit of numerous treaty relationships previously ratified with the Crown.

Imperial Adventures in Africa

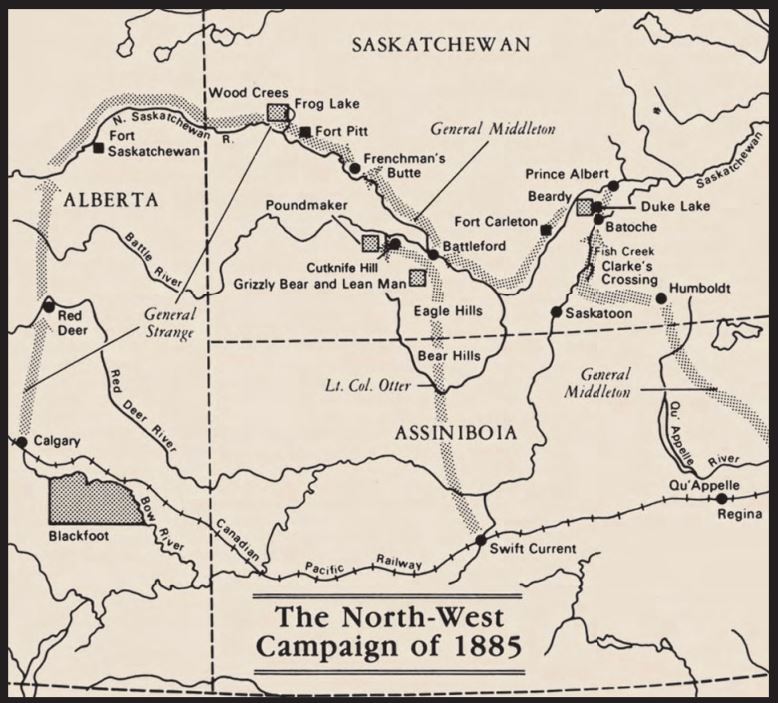

While some Aboriginal people were clashing against Canadian military forces in the Northwest, others were embarking on adventures in aid of British Imperial military operations far beyond Canada’s shores. The first such excursion was the famed Nile Expedition of 1884-85, organised to save a British garrison under General Charles (‘Chinese’) Gordon which was trapped in the city of Khartoum by forces of the Mahdi – an Islamic holy leader who sought independence from Egypt and the establishment of an Islamic republic. Major-General Sir Garnet Wolseley, of Red River fame, commanded the relief expedition. One of his first acts was to ask the Governor General of Canada ‘to endeavour to engage 300 good voyageurs from Caughnawaga, St. Regis and Manitoba as steersmen in boats for Nile expedition.’

Frontispiece and titlepage of Louis Jackson, 1885, “Our Caughnawagas in Egypt: A narrative of what was seen and accomplished by the Contingent of North American Voyageurs who led the British Boat Expedition for the Relief of Khartoum up the Cataracts of the Nile.” (By Louis Jackson, of Caughnawaga, Captain of the Contingent of Kahnawake Mohawks)

“The Canadian Voyageurs’ first touch of the Nile”

In 1884-85, Canadians serving as a unit took part for the first time in a military action overseas. Of the 367 civilian boathandlers constituting the Canadian Voyageur Contingent with the Nile Relief Expedition, no fewer than 86 were Indians from Quebec, Ontario and Manitoba. An unspecified number of Métis also served. Depicted above, with British Army regulars and their Canadian boat crews aboard, are the specially constructed whalers used to transport the Expedition up the Nile. (C.P. Stacey, The Nile Voyageurs, 1884-1885 (The Graphic, London, November 22, 1884))

Much had changed in fourteen years and it was simply not possible to recruit 300 voyageurs. By 1884 the canoe men who had long made a profession of transporting people and supplies over great distances had mostly yielded to the railway. Expert rivermen of a different type were, however, readily available. In the woods of Quebec and Ontario, men felled trees and stacked logs on the river banks all winter; in the spring, when the ice broke, and thereafter all summer long, these ‘shantymen’ drove great rafts of logs downstream, through many rapids to the waiting sawmills. They had a broad knowledge of river work, which was of some value, but they lacked the small boat and canoe skills of the voyageurs. Altogether, 367 men were recruited, of whom 86 were status Indians from Quebec, Ontario and Manitoba. Fifty-six of them were Mohawks from Caughnawaga, captained by Louis Jackson, who subsequently wrote a little book about their experiences entitled Our Caughnawagas in Egypt. As the anonymous preface noted, ‘There is something unique in the idea of the aborigines of the New World being sent for to teach the Egyptians how to pass the Cataracts of the Nile, which has been navigated in some way by them for thousands of years ….’

The Red River Expedition, 1877

Kahnawake Mohawk boatmen, some Manitoba First Nations, and an unrecorded number of Ontario and Québec Métis were among the nearly 400 civilians contracted to transport troops and material during the Red River Expedition in 1877. Aboriginal employment as boatmen in the lumbering industry of the St. Lawrence and Ottawa River watersheds was one early example of Native participation in the emerging wage economy in central Canada. Later Kahnawake Mohawk economic pursuits included high steel construction as well as professional military service. The process by which Aboriginals undertook paid individual employment in support of colonial and Dominion military projects was complex and occured over time as Native peoples and communities gained ever greater exposure to the mainstream wage economy. Initially hired at the time of the Red River Rebellion and the Nile Expedition as civilian labourers possessing specialized skills in boat handling and other tasks having a military application, only toward the end of the 19th century did Natives begin to consider enrolment as private soldiers in Crown military forces. ( Library and Archives Canada (C-134480))

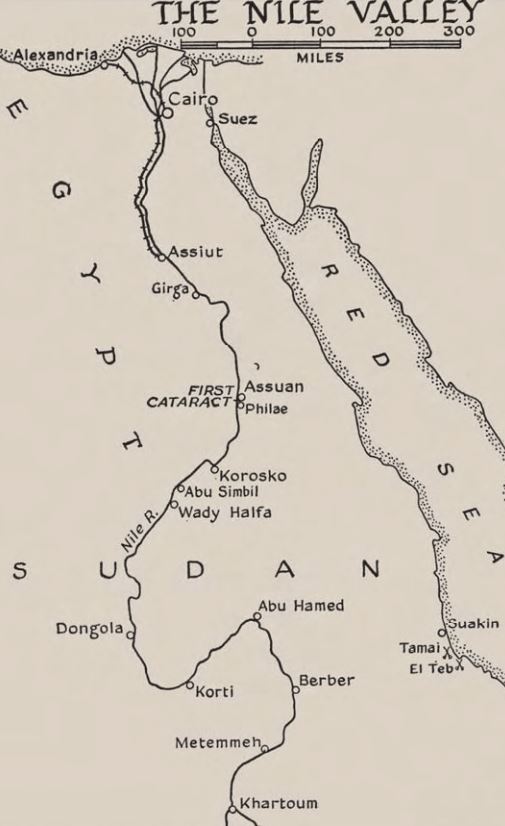

Map: the Nile Valley (Department of National Defence)

The passage up the long Nile from the railhead at Wadi Halfa would prove long, exhausting and dangerous. Toronto militiaman Lieutenant-Colonel Frederick Charles Denison and his men disembarked from the foot of the Second Cataract on 26 October 1884. They were approximately halfway to Khartoum, with 1300 kilometres, four cataracts and many lesser rapids in their path. They succeeded in transporting the British troops to the upper Nile by January 1885, when they made contact with steamers sent out of Khartoum by Gordon. On 24 January these steamers found that the city had fallen to the Mahdists and Gordon was dead. Wolseley’s expedition arrived 56 hours too late. Subsequently the British returned back down the Nile, ably guided by the Canadian rivermen.

Although the military operation failed to relieve the ill-fated garrison at Khartoum, there was no doubting the success of the Canadian contingent. Lieutenant-Colonel Coleridge Grove, the commandant at Gemai and assistant adjutant-general for boat services, recorded that:

The employment of the voyageurs was a most pronounced success. Without them it is to be doubted whether the boats would have got up at all, and it may, be taken as certain that if they had, they would have been far longer in doing so, and the loss of life would have been much greater than has been the case….

Brigadier-General F.W. Grenfell, in charge of Nile communications, fully endorsed Grove’s view. ‘I am of opinion that the Indians were best adapted to working the many rapids. Their skill in handling a boat in bad water was most marked. The expedition could hardly have done without their valuable aid.’ Finally, Butler concluded that the best of the voyageurs were:

… French-Canadians, Iroquois from Lachine, and Swampy Indians and half-breeds from Winnipeg. Could we have obtained a couple of hundred more of this class of real voyageurs, our gain in time would have been very great – so great indeed that the saving of an entire week might easily have been effected in the concentration of the fighting force at the rendezvous at Korti.

Those boatmen, who actually reached Khartoum, were awarded the KIRBEKAN bar together with THE NILE (1884-85) medal. Sixteen Canadians, including one Saulteaux and two Caughnawagas, lost their lives. Six were drowned in the Nile cataracts, two were killed when they fell from a train in Egypt, and eight died of natural causes. Though their numbers were not huge, the Aboriginal voyageurs in the Nile operation played a significant role. Nor would it be the last time that Aboriginal men were called upon, as part of a Canadian expeditionary force, to support of the Crown far from their traditional homelands.

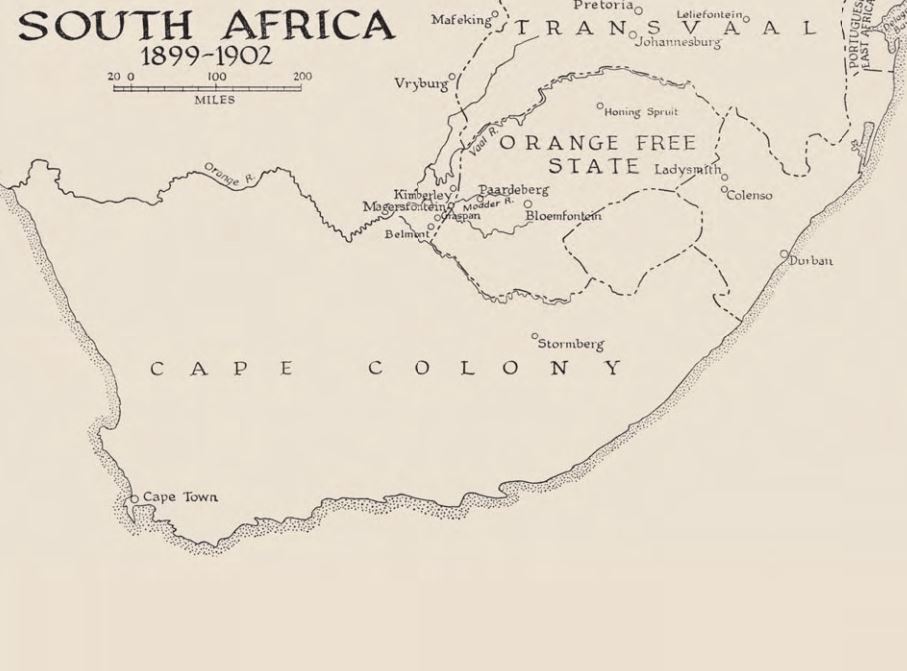

Map: South Africa 1899-1902 (Canadian War Museum)

In 1899, the British found themselves engaged in another colonial conflict in Africa, this time at the southern extremity against the Boer Republics. After some initial defeats to the determined and well-armed Boer fighters, the British Empire began concentrating substantial reinforcements at the Cape, and called upon its dominions for men. Pressure from the Anglo-Canadian community drove Wilfrid Laurier’s government to commit voluntary contingents to serve in South Africa. In all, more than 8,000 Canadians enlisted in Canada’s first major international expeditionary force. Nearly all of these volunteers were ‘amateur’ soldiers, given that Canada’s tiny regular component, the Permanent Force, was only a few hundred strong. Unfortunately, we will never know the exact number of Aboriginal recruits that served with the Canadian troops in South Africa, as enlistment was on an individual basis and no account was taken of racial origin in enlistment papers. Those who joined did so as individuals, and some had militia experience. Canadian militia units may have welcomed some because their heritage and upbringing was believed to ideally suit them to such necessary roles as scouts and sharpshooters, though this remains conjecture.

Portrait of John Ojijatekha Brand-Sero (David Boyle, Ontario Archaeological Report, 1898)

Sergeant Walter White, 21st Essex Fusiliers (Frederick Neal, The Township of Sandwich Illustrated)

The Canadian South African Memorial Association's officially styled granite monument, listing Bloody Sunday's fatalities (Feb. 18th, 1900) (Canadian South African Memorial Association's Collection (NA PA-18142))

It was during the South African War that Canadian Aboriginals, for the first time, made concerted efforts to enlist as individual soldiers in the military forces of the Canadian Dominion and British Empire. John Brant-Sero (above left) a Grand River Mohawk, was refused entry into a British unit on grounds, he felt, of racial bias. Private Walter White, (Anderdon band of Wyandot) of The Royal Canadian Regiment (above centre), late colour sergeant of the 21st Essex Fusiliers in the Canadian Militia, was killed in action in South Africa in 1900. His name is the last shown on the monument pictured above right.

Left: Six Nations Militia in front of the Council House, c. 1880. (Warriors, A Resource Guide, the Woodland Indian Cultural Educational Centre, 1985)

Right: A Six Nations Regiment (The Indian Magazine, Vol. III, No.4, January, 1896)

Although raised as early as 1892, the Oshweken (Six Nations) Company of the 37th Haldimand Rifles (above), Canadian Militia, were unsuccessful in their attempts to have their number transferred for active service overseas during the South African War. Separate attempts in 1896 to raise an entire regiment exclusively from among Grand River Iroquois volunteers had likewise been unsuccessful – despite the eclectic uniform proposed (shown here).

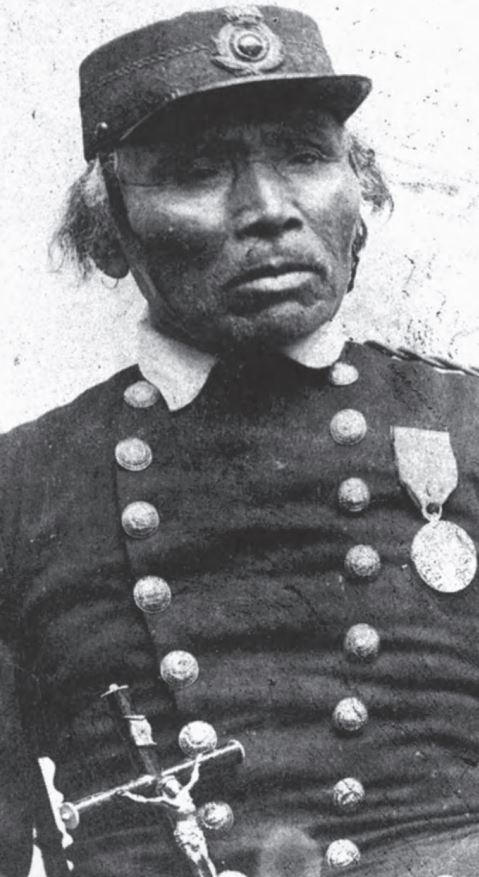

Chief Lo-Haar of the Comiaken hand of Cowichan (1824-1899)

From the 1840’s to the end of the 19th century, from the praries to the Northwest coast, ad hoc local units of Indian and Métis volunteers, variously styled Home Guards, Native Constabulary or Militia, were raised periodically in response to particular circumstances. These ranged from providing aid to the civil power in apprehending Indian and other fugitives from colonial law, to countering feared Russian, American or Fenian invasions. Pictured here in colonial militia uniform is Chief Lo-Haar (1824-1899) of the Comiaken band of Cowichan. In 1856 1856 he worked closely with civil, military and naval authorities in apprehending individuals sought in attacks against settlers in the Crown colony of Vancouver Island. The motives of individuals and groups who cooperated with colonial authorities against other Aboriginals were complex and varied. These ranged from the desire to act against traditional enemies, to the conviction that the advent of Crown hegemony would be a stabilizing influence on intertribal relationships. (Royal British Columbia Museum photo (PN 5935))

There was at least one effort to include an indigenous unit in the Canadian expeditionary force. As early as 1892, an Ohsweken (Six Nations) company of the 37th Haldimand Battalion of Rifles was mustered. However, efforts to have the militia company transferred en masse to one of the Canadian contingents recruited to fight in South Africa were unsuccessful. Perhaps, Indian agent ‘Reports of rumours circulating in the North West that Indians wish to join the Boer force in Transvaal’ caused the government concern that the provision of modern military training and organization to Aboriginals, would somehow be utilized against the state itself.

One of the volunteers was Private Walter White of the enfranchised Anderdon band of Wyandot (Hurons), near Sarnia, Ontario. He enlisted in the First Contingent with the 2nd (Special Service) Battalion, Royal Canadian Regiment of Infantry, after previous service as a colour sergeant with the 21st Battalion Essex Fusiliers. Like many other South African volunteers, White willingly dropped in rank to enlist. Unfortunately, the nineteen year old was killed in action ‘within twenty yards of the Boer trenches and much in advance of any other British dead’ during the Battle of Paardeberg on 18 February 1900. At least those who enlisted in Canada were spared the frustration of John Brant-Sero, a Grand River Mohawk who travelled to South Africa and tried to enrol in a British unit:

I have just returned from South Africa, disappointed in many respects, but I do not wish these lines to be understood as a grievance. I went to that country from Canada hoping that I might enlist in one of the mounted rifles; however, not being a man of European descent, I was refused to do active service in Her Majesty’s cause as did my forefathers in Canada … I was too genuine a Canadian.

In Canada’s next war, although there would initially be some similar feelings in parts of the Dominion, the precedent of enlisting Aboriginal individuals in Canadian regiments was re-established.

By the dawn of the 20th Century, the relationship between the state and Aboriginal peoples in Canada had been fundamentally transformed over the preceding century. Once politically independent peoples were now increasingly constrained within a tight administrative and legislative regime, as legal wards of the Crown. Nevertheless, Aboriginal peoples had continued to answer the call to arms, against rebels and Fenians close to home, and against enemies of the Crown in far-flung fields of battle. Initially they had done so as warriors fighting in their own national or tribal contingents. As the years progressed, Aboriginal men were increasingly sought as individuals, or for their specialist skills at boat handling, field craft or marksmanship. The forms of service had changed, but traditions of military service remained.

Related reading

BERNIER, Serge, Canadian military heritage: Volume III (1872-2000), (Montreal : Art Global, 2000).

GRAVES, Donald E., Guns across the river : the battle of the Windmill, 1838, (Prescott, Ont. : Friends of the Windmill Point ; Toronto : Robin Brass Studio, 2001).

STACEY, Charles P., ed., Records of the Nile Voyageurs, 1884-85: the Canadian Voyageur Contingent in the Gordon Relief Expedition, (Toronto : Champlain Society, 1959).

STANLEY, George F.G., Toil and trouble: military expeditions to Red River, (Toronto : Dundurn Press, 1989).

STONECHILD, Blair and Bill Waiser, Loyal till death: Indians and the North-West Rebellion, (Calgary : Fifth House, 1997).