In Defence of their Homelands

The fall of New France and the end of French power in the interior of the continent altered the geo-strategic situation for Aboriginal peoples in the north-eastern portions of North America. Unfortunately for Britain and for its Aboriginal allies, victory in the Seven Years’ War failed to create prolonged peace in North America. Instead, Aboriginal communities were forced into a series of wars over the next 55 years, first against the British and later the new American Republic, for their freedom, their lands and their survival.

Shifting Relationships

Chief of the Ottawa nation, War of 1812

Depicted as he may have appeared at a formal council with British officers of the Indian Department during the war, this chief wears finely embroidered clothing and is adorned with a mixture of aboriginal and white jewelry. (Painting by Ron Volstad (Department of National Defence))

In 1760-61, with the French threat gone, British officials no longer felt obliged to accommodate Aboriginal wishes. This was particularly evident among the western nations of the Great Lakes and the Ohio valley that had traditionally allied with France. British settlers from the Thirteen Colonies, whose penetration of Aboriginal lands in this area had previously been restricted by fear of French and Indian attack, now flooded in unchecked. They began to carve out farmsteads, in some cases without first consulting the Miami, or Ottawa, or Wyandot on whose land they settled. In other cases, shady and competing land purchase deals were obtained by British land speculatiors. This drastic transformation in Aboriginal relations with the Europeans fostered a burning resentment amongst Native peoples across the frontier. As one of the western chiefs explained to his British counterpart:

… although you have conquered the French, you have not yet conquered us! We are not your slaves. These lakes, these woods, and mountains, were left to us by our ancestors. They are our inheritance; and we will part with them to none. Your nation supposes that we, like the white people, cannot live without bread – and pork – and beef! But you ought to know, that He, the Great Spirit and Master of Life, had provided food for use, in these spacious lakes, and on these woody mountains.

Sir William Johnson, the superintendent of the Indian Department, the Crown agency created in 1755 to manage Aboriginal affairs in British North America, was aware of this resentment. He warned the British commander-in-chief, Major-General Sir Jeffrey Amherst, that the situation was serious, but Amherst was determined to reduce expenditure in North America by stopping the traditional practice of giving gifts. He viewed this practice as mercenary; furthermore it was not his intention ‘to gain the friendship of Indians by presents.’ Instead, he calculated that a scarcity of supplies and ammunition among the western nations, combined with a firm British hand, would keep them quiet.

The Pontiac Rebellion of 1763

Costume of Domiciliated Indians, c. 1807

Depicted in a temporary hunting and fishing camp, this 1807 drawing by George Heriot shows aboriginal peoples of the early 19th century wearing and using a mixture of traditional and European clothing, tools and weapons. By the time of the War of 1812 many of the aboriginal groups in eastern Canada had chosen to live in fixed locations. (Library and Archives Canada (C-012781))

By the spring of 1763, widespread rumours and reports suggested that the Aboriginal peoples were planning an offensive against the British frontier. These rumours were true. The so-called Pontiac Rebellion of 1763 was another in a series of struggles by desperate Aboriginal peoples to preserve their territory, independence and culture against the pressure of European intrusion. In May, an alliance of western nations came together under the Ottawa chief, Pontiac. Pontiac’s primary target was the principle British fort in the region at Detroit. Alerted to his danger, the British commander managed to foil Pontiac’s efforts to take the fort by subterfuge. Pontiac was left with little choice but to lay siege. This was the signal for the warriors of all the allied Aboriginal people across the Great Lakes-Ohio region to strike, and the results stunned the British. Unexpectedly, Aboriginal warriors attacked and overwhelmed almost every British fort in the area: Fort Sandusky fell to the Ottawa; Fort St. Joseph to the Potawatomi; Fort Miami to the Miami; Fort Ouiatenon to the Miami, Kickapoo and Illinois; Fort Michilimakinaw to the Ojibwa; Fort Edward Augustus to the Ottawa, Wyandot and Ojibwa; and Forts Venango, La Boeuf and Presque’Ile to the Seneca and others. In addition, warriors lashed out at the settlers in their midst, killing up to two thousand in raids on farms and villages in the Ohio valley that deadly summer.

Sir William Johnson (1715-1774)

The first Superintendent of the British Indian Department, Johnson was instrumental in securing an alliance between the British crown and the Iroquois League of Six Nations that stood British interests in good stead during the Seven Years and American Revolutionary Wars. (Library and Archives Canada (C-005197))

Despite successes elsewhere, Pontiac’s failure to seize Detroit gradually undermined his prestige and the power and cohesion of his alliances dissipated. Sir William Johnson, a resident of northern New York and connected by marriage with the leadership of the Iroquois League of Six Nations (the Tuscarora people having joined the League in the 1720s), was able to conclude peace and restore the traditional distribution of presents. More importantly, shocked by the death and expense of war with the still potent Aboriginal people of the continental interior, the British crafted the Royal Proclamation of 1763. This important document established the colony of Quebec and sought to establish regulations and rules of conduct for dealings with the Indians in the fur trade and in land deals. Moreover, it set a boundary between the British colonies and a designated Indian Territory into which White settlers were forbidden to trespass. This and a subsequent treaty, signed at Fort Stanwix in 1768, established a line from Oneida Lake, in northern New York, southward to the Pennsylvania border and then southwest, to and along the Ohio River, as the boundary between non-Aboriginal and Aboriginal peoples. These measures were intended to protect the nations of the Great Lakes and provide for a peaceful and gradual expansion of the frontier.

American colonists, covetous of the rich lands of the interior, did not view this new territory in the same light. They saw it as an arbitrary attempt by Great Britain to limit their westward expansion. Effectively, Britain found itself fulfilling the role previously occupied by France as the barrier to American colonial expansion. As it turned out, the settlement pressures to move across the border into the Indian Territory were too great, and the British government’s ability to control the frontier was too limited. In the decade that followed the Pontiac Rebellion, settlement continued to expand into what the Americans considered the Northwest, despite the Royal Proclamation. British efforts to control the frontier were the first of many measures, including increased taxation, which provoked widespread resentment and ultimately resulted in American civil unrest.

American Revolutionary War, 1775-1783

Thayendanegea or Joseph Brant (1742-1807)

A war chief of the Mohawk nation, Thayendanegea led aboriginal forces in northern New York during the Revolutionary War. Following the British defeat he brought his people to Canada to settle along the banks of the Grand River and was prominent in aboriginal diplomacy in North America until his death. (Library and Archives Canada (C-011092))

The Thirteen Colonies moved toward an outright breach with the British in the 1770s. Initially, both sides hoped and intended that the Aboriginal people should remain neutral. Soon both were competing to recruit Aboriginal allies. Throughout the American Revolutionary War, Aboriginal military power in the Great Lakes area became a major consideration for British military leaders in the northern theatre. The major diplomatic efforts were directed at the League of Six Nations Iroquois, which had largely remained neutral in European conflicts since 1701. Although the League attempted to maintain its neutral stance, it was dragged into the conflict and torn asunder in its own civil war. Warriors from both the Iroquois League and the Seven Nations of Canada were instrumental in holding up a rebel offensive against a weakly defended Canada in the autumn of 1775. The delay forced the Americans to prolong their campaign over the winter and ultimately to face defeat at the gates of Quebec City. In the summer of 1777, a force of British regulars, Loyalists and warriors won a notable success at the battle of Oriskany, but Aboriginal allies were less decisive in assisting the doomed offensive led by Major-General John Burgoyne up the Champlain Valley that autumn. Burgoyne’s defeat and surrender at Saratoga brought France into the war on the side of the rebellious colonies and the conflict broadened into a general European war.

For the next five years, Britain’s Aboriginal allies in the north, led by the Mohawk chief Thayandenaga, or Joseph Brant, participated in a series of campaigns and raids against the border settlements of New York and Pennsylvania. Little quarter was given on either side. Although the main focus of the larger conflict shifted to the south in 1780, Britain’s Aboriginal allies won two of their most notable successes – Sandusky and Blue Licks – after the surrender of Cornwallis at Yorktown in 1781. Aboriginal peoples also suffered fearsome losses. The homelands of the Iroquois League were devastated by an American punitive campaign in 1779, and perhaps the worst depredation on either side was the massacre by American troops of more than a hundred Christian Delaware men, women and children at the Gnadehutten Mission in the Ohio country in 1782.

Undefeated on the field of battle, Brant and his warriors were appalled to learn of the terms of the 1783 Treaty of Paris that ended the war and established a new international border between Britain’s North American possessions and her former colonies. Negotiated in Europe by European and American statesmen, this treaty did not include a single reference to the Aboriginal nations who had participated in the conflict, although it ceded the lands of those who had been allied with Britain to the new American republic. As an officer of the Indian Department reported to London, the Indians rightfully felt betrayed by the terms of the treaty:

… [They] look upon our conduct to them as treacherous and cruel: they told me they never could believe that our King could pretend to cede to America what was not his own to give … they would defend their own Just Rights or perish in the attempt to the last man, they were but a handful of small People but they would die like men, which they thought preferable to misery and distress if deprived of their Hunting Grounds.

This resentment was so strong that for a considerable period after 1783 British authorities feared that their former allies would attack them. Fortunately for the war weary British, this did not happen. The British offered land in Canada and financial compensation to the Iroquois Loyalists, as they did to non-native Loyalists. Brant, the Mohawk war chief, and Tekarihogen, the peace chief, led 1,800 Mohawks, Cayuga and other Six Nations people to a large tract of land on the Grand River north of Lake Erie, while John Deserontyon established a smaller and separate Mohawk community at Tyendinaga on Lake Ontario’s Bay of Quinte. John Graves Simcoe, the governor of the new colony of Upper Canada (created in 1791), hoped that these new Aboriginal settlements would provide an active barrier against possible American aggression from the south.

Trouble in the Northwest, 1783-1794

Officer, Indian Department. 1812

During the War of 1812, the aboriginal people of the Great Lakes area played an important role in defending Canada against American invasion. Warriors in the field were often accompanied by officers of the British Indian Department who spoke their language and knew their customs, and who served as liaison between aboriginal leaders and Britsh military commanders. This Indian Department officer is dressed practically for the field and wears a felt slouch hat, and old and patched uniform coatee, and laced rather than high riding boots. He would have little use for his sword in action but retains it as a symbol of his rank. (Painting by Ron Volstad (Department of National Defence))

Some of the Aboriginal peoples who had been allied with Britain elected to remain in the new American republic, a choice many came to regret. As soon as the restraints stipulated in the Royal Proclamation of 1763 and the Treaty of Fort Stanwix of 1768 were removed, the attitude of the American government was that those nations who had fought for Britain during the war were conquered peoples and their territory was forfeit. American officials imposed severe treaties on the Iroquois still resident in the United States, forcing them off their traditional land onto reservations. Ironically, those who suffered worst were the Oneida and Tuscaroras who had supported the revolutionaries during the war. The Americans had less luck with the Algonkian and Iroquoian-speaking peoples further west in the Ohio valley. More numerous, more united in the defence of their territory, and further from the centres of White population, these Aboriginal communities refused to accept any change in the boundary of the Ohio River, that had been established in the 1760s. The victorious, but nearly bankrupt, American government viewed this region as its birthright, its inheritance, and needed the revenues from the sale of these lands to pay its substantial war debts. The stage was set for further conflict.

The nations of the Northwest (the modern states of Illinois, Indiana, Michigan and Ohio) formed a new confederacy in 1786, which they called ‘The United Indian Nations,’ to defend their land. The infant American government, caught between a flood of settlers who wanted to move into the Ohio area and the intractability of Aboriginal peoples who wished to preserve that river as their boundary, was forced into military action after the Native Confederacy attacked illegal settlements on their side of the river. In September 1790, Brigadier-General Josiah Harmar was ordered ‘to extirpate, if possible,’ the attackers. He set out from Fort Washington (modern Cincinnati) with 1,400 regulars and militia to invade the Miami nation. Within three weeks, having suffered more than 200 casualties, he was back at his base, with nothing accomplished but the burning of a few abandoned villages.

American hopes for a quick victory were shattered. One congressman brooded ‘a horid [sic] Savage war Stairs [sic] us in the face.’ Instead of being humbled by the Harmar expedition, the Confederacy ‘appear ditermined [sic] on a general War.’ In the early summer of 1791, Major-General Arthur St. Clair assembled a larger force, consisting of 1500 regulars and 800 militia. His advance was delayed while he trained an army consisting of recruits who one of his staff characterized as ‘the offscourings of large Towns and Cities; – enervated by Idleness, Debaucheries and every species of Vice.’ St. Clair began to creep forward in September, accompanied by a lengthy procession of camp followers. Shortly after sunrise on 4 November 1791, 2,000 warriors led by the Confederacy’s war chiefs, the Shawnee, Blue Jacket and the Miami under their warrior chief Michikinikwa (Little Turtle), attacked St. Clair’s camp on the banks of the Wabash River. Although, St. Clair, old, sick and feeble, had neglected to post proper pickets around the badly sited camp, the initial attacks were twice repulsed. At this point, one witness recorded, the Ohio warriors, ‘irritated beyond measure,’ simply pulled back to reorganise:

… a little distance, where separating into their different tribes and each conducted by their own Leaders, they returned like Furies to the assault & almost instantly got possession of near half the Camp – they found it in a row of Flour Bags, & bags of Stores, which serv’d them as a Breast work, from behind which kept up a constant & heavy fire, the Americans charg’d them several times with Fixed Bayonets, but were as often repuls’d – at length General Butler, second in Command, being kill’d, the Americans fell into confusion & were driven from their Cannon, round which a Hundred of their bravest Men fell, the Rout now became universal, & in the utmost disorder, the Indians follow’d for Six Miles & many fell Victims to their Fury.

When it was over, 647 American soldiers were dead, 229 wounded and all St. Clair’s camp stores and 21 pieces of artillery lost. Aboriginal casualties were estimated at 50 warriors killed and wounded. The Battle of the Wabash was the single greatest victory by Aboriginal peoples against the armed forces of the United States.

Following that triumph, the Northwest Confederacy ravaged the White settlements on their side of the 1768 boundary for nearly two years, but refrained from attacking American territory. Throughout its struggle, the Confederacy received advice from the British Indian Department officers at Detroit, but their requests for active military support were denied, even though Britain had retained its posts south of the border. Britain offered to mediate in the contest and suggested the establishment of an independent and neutral Aboriginal state between the Mississippi, the Ohio and the Great Lakes. Not surprisingly, the American government firmly rejected this proposal, which it regarded as unwanted meddling. For nearly three years, Britain, the United States, the Confederacy, and the Six Nations of Canada under Joseph Brant tried to end the controversy over the boundary through a series of conferences, but the Aboriginal peoples of the Northwest remained adamant that the Ohio River continue to be the dividing line.

The Snow-shoe Dance, 1844 (Library and Archives Canada (C-006271))

The Confederacy’s desires for independence were shattered in 1794 when a new and well-trained American army under Major-General Anthony Wayne advanced into their territory and defeated a series of Aboriginal attacks, culminating in the major American victory at the battle of Fallen Timbers in August. When British military commanders refused military aid to retreating Aboriginal warriors, the Confederacy began to disintegrate. Tensions between Britain and the United States, which had come close to the point of troubles in the Northwest and maritime matters on the high seas, were ameliorated with the signing of Jay’s Treaty in 1794. The British turned over the posts they had retained on American territory in return for guarantees that British subjects and Aboriginal peoples could pass freely over the border. For the Aboriginal Confederacy, the result was despair: the British had abandoned them for a second time. Some fled to Canada, but most signed a general peace treaty with Wayne in 1795 that ceded the Ohio valley to the American government. Their 12-year stand against the United States had failed, but it provided ample time for the infant province of Upper Canada to take root and prosper.

Tecumseh, His Confederacy and the Road to War

Tecumseh (1768-1813)

The Shawnee Chief Tecumseh dreamed of forming a confederacy of all the aboriginal nations from the Great Lakes to the Gulf of Mexico. He brought his followers to the British side in the War of 1812, but military reverses led to his death in battle in 1813. There is no known picture of Tecumseh but most specialists agree that this sketch, drawn from an eyewitness description of the man, is the closest likeness. (Library and Archives Canada (C-000319))

For nearly a decade after the battle of Fallen Timbers, there was relative peace in the Northwest. White settlers flooded into the area and the new American territories of Illinois, Indiana, Michigan and Ohio were established. By 1810, some 200 000 Americans lived in Ohio alone. The Northwest nations had not forgotten their humiliation, however. They began to pay greater attention to an impressive young Shawnee named Tecumseh, who urged the creation of a single native confederacy stretching from the Canadian border to Spanish territory in Mexico that would be strong enough to resist the encroachment of the ‘Big Knives,’ as he termed the Americans. Tecumseh travelled ceaselessly, spreading his message to the Aboriginal peoples from the Great Lakes to the mouth of the Mississippi river. But while Tecumseh gave his listeners hope for the future he also advised them not to engage in warfare with the Americans until the time was right.

Not surprisingly the popularity of the charismatic Tecumseh worried American frontier officials. Governor William Henry Harrison of the Indiana Territory met with Tecumseh twice in vain attempts to reduce the increasing tension between the Aboriginal peoples and White settlers, and he was both impressed and concerned:

The implicit obedience and respect which the followers of Tecumseh pay to him, is really astonishing, and more than any other circumstance bespeaks him one of those uncommon geniuses which spring up occasionally to produce revolutions, and overturn the established order of things. If it were not for the vicinity of the United States, he would, perhaps, be the founder of an empire that would rival in glory Mexico or Peru. No difficulties deter him. For four years he has been in constant motion. You see him to-day on the Wabash, and in a short time hear of him on the shores of Lake Erie or Michigan, or on the banks of the Mississippi; and wherever he goes he makes an impression favorable to his purposes. He is now upon the last round to put a finishing stroke to his work.

Which is Tecumseh?

Pictured above are two varying depictions of Tecumseh. The sketch at left depicts Tecumseh in traditional dress and was drawn in 1808. The 1848 painting at right by Benson Lossing was based on the former sketch but this version depicts Tecumseh in the uniform of a British general as was the popular (but untrue) belief of the time. Also note that Tecumseh is pictured sporting a “nose ring” which was usually not depicted in drawings of aboriginal peoples of this period.

In the autumn of 1811, Harrison decided to make a preemptive strike against this latest Confederacy. In early November, while Tecumseh was absent on a journey to the south, he moved a force of regulars and militia near the village of Tippecanoe (near modern Lafayette, Indiana) established by Tecumseh’s brother, Tenskwatawa or the Prophet. The Prophet was unable to restrain his warriors and sniping between sentries escalated into a pitched battle that was won by the Americans. Many of the defeated fled to the safety of Canada. When Tecumseh returned to the area early in 1812, he set out to rebuild his Confederacy and to placate American authorities. At the same time, he sought the assistance of British officers of the Indian Department who listened to him partly because they were convinced that war between Britain and the United States was at hand.

Although Tecumseh still counselled peace, he also believed that war was imminent and promised his Confederacy would ally itself with Britain in the forthcoming contest. He expressed to the Indian Department officers that ‘if their father the King should be in earnest and appear in sufficient force, they would hold fast by him.’ Tecumseh also stated that his followers were determined to defend their land and, although they did not expect Britain to engage in military operations, they did expect logistical support – ‘you will push forward towards us what may be necessary to supply our wants.’ For their part, the Indian Department cautioned the Confederacy not to attack until war was declared. As one officer put it, ‘Keep your eyes fixed on me; my tomahawk is now up; be you ready, but do not strike until I give the signal.’ Tecumseh agreed with this advice, but warned the British that:

If we hear of the Big Knives coming towards our villages to speak peace, we will receive them, but if We hear of any of our people being hurt by them, or if they unprovokedly advance against us in a hostile manner, be assured we will defend ourselves like men. And if we hear of any of our people having been killed, We will immediately send to all the Nations on or towards the Mississippi, and all this Island will rise as one man.

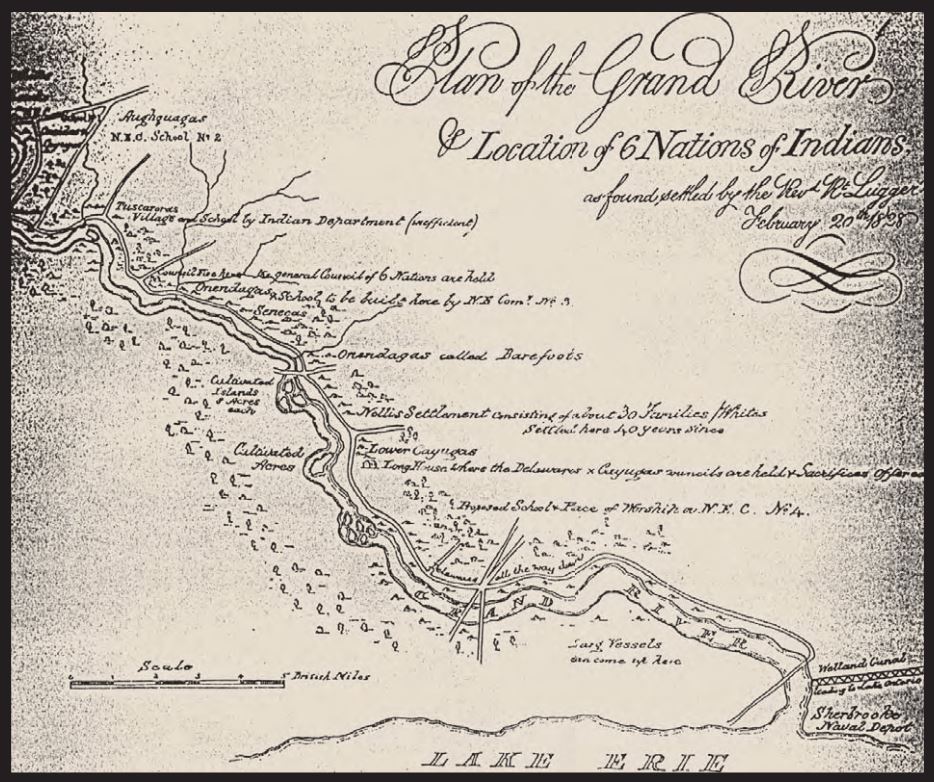

Plan of the Grand River and Location of Six Nations of Indians, as found settled by the Reverend RT Lugger, February, 26th, 1828.

As it was designed to do from the time of its founding in 1784, the original Grand River tract provided a military corridor which effectively checked potential invasion from either the Detroit-Windsor frontier to the west, or from the Niagara frontier to the east. As with neighbouring Anishinabeg groups, Grand River fighters were successfully mobilized in the Crown interest in the War of 1812 and again during the Rebellions of 1837-1838. Their proximity in relation to government and population centres, military garrisons, transportation and communication routes, and frontiers with the U.S., and their economic adaptations arising from these situations, influenced the manner in which First Nations might subsequently support the Crown militarily during war and conflicts other than war. (Metropolitan Toronto Reference Library (971.3-C4.))

Throughout this period, the Indian Department had continued to provide annual gifts, including weapons and shot, to Aboriginal peoples in the United States and shelter for refugees from the struggles below the border. Such activities were regarded with great suspicion by American officials. Although some Aboriginal warriors residing in Canadian territory had participated in the fighting in the Ohio valley, their leaders in Canada encouraged the peaceful resolution of the differences between the Northwest nations and the Americans. The Seven Nations of Canada and the Iroquoian peoples in Upper Canada had seen enough conflict in the previous century and preferred to stay out of Anglo-American quarrels.

This desire to remain neutral became difficult, however, as Britain and the United States drifted toward war in the first decade of the 19th Century. The origins of the tensions between the two were, as usual, to be found in Europe. In 1793, revolutionary France had declared war on Britain, initiating a struggle that would ensue, with a brief intermission, for 23 years. Both countries had adopted restrictive maritime policies, forbidding the ships of neutral nations that traded with one belligerent from trading with the other. These measures severely curtailed the profits of American merchants. Since the British were supreme at sea, particularly after Nelson’s great naval victory at Trafalgar in 1805, American resentment was exacerbated by the Royal Navy’s penchant for stopping American vessels on the high seas and forcibly impressing their sailors, some who were British deserters, into British service. Many also suspected that Britain was promoting trouble in the Northwest by actively supporting the nations of Tecumseh’s Confederacy. Britain, pre-occupied with the war in Europe, seemed oblivious to American concerns. A few weeks after the battle of Tippecanoe in 1811, President James Madison of the United States, convinced that war was the only way that his country could resolve its grievances, decided to put the republic ‘in armour’ and prepare for hostilities against Britain. Given the overwhelming strength of the Royal Navy, the United States had only one practical military option: an attack on Canada.

The Coming of War in 1812

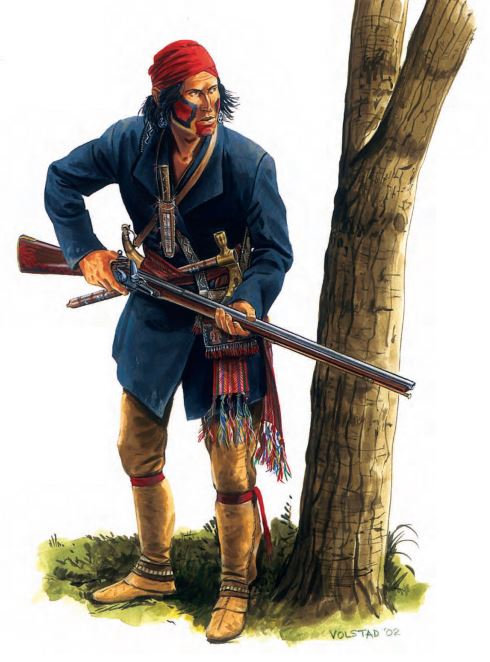

Mohawk Warrior from Tyendinaga, Autumn 1813

The warriors from the small Mohawk community at Tyendinaga near Kingston, although few in numbers, participated in much fighting during the War of 1812, seeing action at Sacketts Harbor and in the Niagara peninsula in 1813. Their most prominent service was rendered at the battle for Crysler’s Farm in November,1813 where they played a role disproportional of their numbers. This warrior is depicted as he may have appeared at Crysler’s Farm. (Painting by Ron Volstad (Department of National Defence))

Lieutenant-General Sir George Prevost, governor-general and commander-in-chief of the British colonies in North America, knew that because of British military commitments in Europe he could not expect massive troop reinforcements. Prevost had about 5,600 regular soldiers in Upper and Lower Canada, backed up by some 60,000 militia in the lower province and 11,000 in the upper. Faced by an enemy population estimated to be more than seven million, his plan was to abandon Upper Canada, which was surrounded on three sides by American territory, and pull back to Montreal and, if necessary, Quebec, until he could be reinforced from Britain. This cautious defensive strategy was opposed by Major-General Isaac Brock, Prevost’s subordinate commander in Upper Canada. Brock argued that the upper province could be successfully defended if the Aboriginal nations in the Northwest were encouraged to attack the frontier settlements in that area, disrupting possible American invasion plans. Brock recognized, however, that before the British could ‘expect an active cooperation on the part of the Indians, the reduction of Detroit and Michilimackinac must convince that people, who conceive themselves to have been sacrificed in 1794, to our policy, that we are earnestly engaged in war.’

In the six months preceding the American declaration of war in June 1812, Indian Department officers were secretly active among Native peoples on both Canadian and American territory, where they estimated they might be able to call on the support of as many as 10,000 warriors. The largest proportion, 8,410 according to the Department, would come from the western nations whose own conflict with the Americans made them ‘amicable to the Cause.’ There were far fewer warriors available on Canadian territory. The Seven Nations of Canada were estimated to be only 1,040 strong, while in Upper Canada the Iroquois people on the Grand River and at Tyendinaga, and the Mississaugas and Ojibwa peoples, could only contribute 550 men. While the western nations were mostly prepared to ally themselves with the British, the Aboriginal peoples in Canada proved more equivocal.

This uncertain response was particularly evident in the Grand River nations, the strongest Aboriginal force in the Canadas, who adopted a neutral stance toward the forthcoming conflict at the urging of their fellow Iroquois who lived in American territory. The Six Nations had longstanding grievances against officials of the British Indian Department, whom they suspected were profiting from the sale of their lands to the whites. Even Brock’s promise to investigate these grievances and, if appropriate, adjust them in their favour failed to change their stance. More persuasive to the Six Nations was the argument made by a delegation of Cayuga and Onondaga chiefs from the United States who visited the Grand River in June 1812 to advise caution:

We have come from our homes to warn you, that you may preserve yourselves and families from distress. We discover that the British and Americans are on the Eve of a War, – they are in dispute respecting some rights on the Sea, with which we are unacquainted; – should it end in a Contest, let us keep aloof: – Why should we again fight, and call upon ourselves the resentment of the Conquerors? We know that neither of these powers have any regard for us … except when they want us. Why then should we endanger the comfort, even the existence of our families, to enjoy their smiles only for the Day in which they need us?

The majority of the Six Nations living along the Grand felt that this was sound reasoning for keeping out of the white man’s quarrels, despite the exhortations of a smaller pro-British faction led by John Norton, Teyoninhokarawen, or the Snipe. The son of a Cherokee father and a Scottish mother, Norton had become a respected leader amongst the Six Nations, and by 1812 was a prominent war chief. The Grand River nations were going to remain neutral and Norton was forced to report to Brock that the community was divided, but that, if threatened by American invasion, ‘I have no doubts they are not so depraved as to be faithless.’

1812: A Year of Victories

Teyoninhokarawen or John Norton, the Mohawk War Chief (1760-1830)

The product of a Cherokee father and Scots mother, Norton was adopted by the Grand River Mohawks and rose to become a war chief of that nation. Between 1812 and 1815 he proved to be, after Tecumseh, one of the most loyal and effective aboriginal military leaders in Canada. Educated in white schools, he not only translated the Gospels into Mohawk but also wrote one of the most complete and literate personal memoirs of the War of 1812 from either side. Note the turban, another popular form of headgear among the Iroquois peoples. (Library and Archives Canada (C-123832))

On 18 June 1812 the United States declared war on Great Britain. American leaders were confident: ‘the acquisition of Canada this year will be a mere matter of marching’ boasted former President Thomas Jefferson. Reality proved different. In 1812, the outnumbered British, Canadian and Aboriginal fighters won a series of critical battles that stopped the Americans in their tracks for that year and consolidated the Anglo-Aboriginal alliance in the Great Lakes-Ohio country.

Impelled by urgent requests from territorial governors in the Northwest concerned about preserving their frontier settlements against Tecumseh and his allies, the Americans planned their main thrust in the Detroit area. Thus, from the outset of the war, American strategic thinking was influenced by the need to reduce what was perceived as a dangerous Aboriginal threat in the Northwest, and deflected from the more decisive objective – the vulnerable St. Lawrence waterway. When war broke out, Brigadier-General William Hull was stationed at Detroit with the better part of the American regular forces and substantial militia under his command. This policy did not change throughout the war and was, perhaps more than military prowess and victories, the major contribution of the Aboriginal peoples to the successful defence of Canada.

On 17 July, a small British force consisting of a few regulars, fur traders, and 130 Menominee, Winnebago and Sioux warriors surrounded the American fort on Mackinac Island which guarded the water passage to Lake Michigan and persuaded the American commander to surrender without a fight. Although Hull had crossed the Detroit River with the bulk of his command on 12 July, capturing the village of Sandwich, this early victory convinced the peoples of the Northwest that the British were serious and they began to threaten Hull’s supply lines, forcing him to withdraw from Canada and take up a defensive position at Detroit on 8 August. By early August, contingents under Tecumseh’s leadership actively prowled around the American position and attacked supply columns. Hull began to lose his nerve. The victory at Mackinac had given Brock one of the two objectives he regarded as necessary to secure the support of the Northwest peoples, and it was already paying dividends.

Brock’s other objective was Detroit. In early August, he moved west to Amherstburg with a force of regulars and militia to join some 600 Northwest warriors. There, on 13 August, he met Tecumseh for the first time, and the two men liked and trusted each other from the outset. Brock wrote to Prevost that ‘a more sagacious or a more gallant Warrior’ than the Shawnee chief ‘does not I believe exist.’ Their combined force of British regulars, Canadian militia and Aboriginal warriors then advanced on Detroit where Hull, convinced he was surrounded by superior numbers of British regulars and warriors, became increasingly distraught. He was even less happy when he received a letter from Brock containing the grim hint that, since ‘the numerous body of Indians who have attached themselves to my troops, will be beyond control the moment the contest commences,’ Hull should surrender in order ‘to prevent the unnecessary effusion of blood.’ The American commander at first refused, but after British artillery opened fire, he agreed to surrender his 2,000 well-entrenched men to Brock and the 1,300 British, militia and Aboriginal fighters under his command. Brock’s bluff had paid off and the only field force in the American army marched into captivity. The victory at Detroit, coming on the heels of the success at Mackinac electrified both the European and Aboriginal peoples of Upper Canada and the Great Lakes-Ohio region, many of whom had assumed that the province would succumb to overwhelming enemy strength.

Though shaken by their early defeats, the Americans would not give up easily. In late September and early October, American troops began massing on the Niagara frontier. To meet this threat, Brock moved the greater part of his forces to Fort George, near Newark (now Niagara-on-the-Lake). He was joined there by Norton and a force of Grand River warriors who, buoyed by the victories in the west, had decided to take an active role in the defence of Canada. Norton was at Newark on the morning of 13 October when information came that the American forces had crossed the Niagara River and established themselves in the village of Queenston, seven miles south. He was ordered to assemble his warriors and move to the threatened spot, learning on the way that Brock had been killed leading a counterattack and that the invaders were in a strong position on the heights above Queenston. The Americans at Queenston outnumbered British forces and it would be some time before reinforcements of regular troops would arrive. Norton’s men hesitated, but one of his warriors urged his ‘Comrades and Brothers’ to:

… be Men; – remember the fame of ancient Warriors, whose Breasts were never daunted by odds of number; – We have found what we came for … there they are, – it only remains to fight …. Look up, it is He above who shall decide our fate. Our gallant friends the Red Coats, will soon support us.

The war party ascended the heights by a little known path, flanking the American position and proceeded to snipe and harass the Americans from behind with ‘coolness & Spirit’ until British reinforcements arrived.

At that point a general attack commenced against the invaders that pushed them back to the edge of the cliffs overlooking the Niagara gorge. John Norton recorded the final moments of the battle.

We rushed forward, & saw the Grenadiers led by Lt. Bullock coming from the right along the Bank of the River; – the Enemy disappeared under the Bank; many plunging into the River. The inconsiderate still continued to fire at them [in the water], until checked by repeated commands of “Stop Fire.” The White Flag from the American General then met General Sheaffe [the British successor to Brock], proposing to Surrender at Discretion the remainder of those who had invaded us. The Prisoners amounted to about Nine Hundred.

The Battle of Queenston Heights was an overwhelming victory, but the death of Brock, as Norton remembered, ‘threw a gloom over the sensations which this brilliant Success might have raised.’

1813: Triumphs and Disasters

The tide of British and Aboriginal victories continued into early 1813 on the western frontier. The loss of Detroit was a major setback for the United States and Madison’s government immediately began planning a counter-attack. William Henry Harrison, the popular and effective governor of the Indiana Territory, was given command of a force of 6,000 regulars and militia with orders to break the power of the Northwest nations and retake Detroit. One of his subordinates, Brigadier-General James Winchester, became impatient and pressed on to the British outpost of Frenchtown on the River Raisin, about forty kilometres southwest of Detroit. The new British commander on the western frontier, Brigadier-General Henry Procter, assembled a force of 550 regulars and militia and about 600 warriors from the Northwest nations and defeated Winchester on 22 January.

In the wake of the victory, Procter neglected to guard his prisoners and a party of Pottawatomi and Wyandot warriors killed about thirty wounded Americans. Warfare on the frontier between Native peoples and newcomers had long been characterised by viciousness and the calculated use of terror by both sides, and this war was no different. The Americans, particularly the frontier militia, neither gave nor expected quarter, determined as they were to annihilate the Aboriginal threat in the area. Northwest peoples, who regarded the war as a struggle for survival, responded in kind. The cruel nature of the conflict was aptly summed up by Assiginack, or Black Bird, an Ottawa chief, in a speech addressed to the officers of the Indian Department who had admonished him for not restraining his warriors’ excesses in battle.

We have listened to your words, which words come from our father. We will now say a few words to you. At the foot of the Rapids last spring we fought the Big Knives, and we lost some of our people there. When we retired the Big Knives got some of our dead. They were not satisfied with having killed them, but cut them into small pieces. This made us very angry. My words to my people were: ‘As long as the powder burnt, to kill and scalp,’ but those behind us came up and did mischief. Last year at Chicago and St. Joseph’s the Big Knives destroyed all our corn. This was fair, but, brother, they did not allow the dead to rest. They dug up their graves, and the bones of our ancestors were thrown away and we never could find them to return them to the ground.

I have listened with a good deal of attention to the wish of our father. If the Big Knives, after they kill people of our colour, leave them without hacking them to pieces, we will follow their example. They have themselves to blame. The way they treat our killed, and the remains of those that are in their graves in the west, makes our people mad when they meet the Big Knives. Whenever they get any of our people into their hands they cut them like meat into small pieces.

We thought white people were Christians. They ought to show us a better example. We do not disturb their dead. What I say is known to all the people present. I do not tell a lie.

Although there may have been isolated incidents of this type, John Norton felt it ‘would be useless as well as endless to repeat the number of cruelties that had been asserted, & as bluntly contradicted, – without proofs to substantiate either on one Side or the other.’ Regardless of proof, greatly exaggerated accounts of the Frenchtown massacre circulated in the United States, stoking the fires of vengeance.

Voltigeurs on the march in 1813.

Canadian voltigeurs on the march in 1813. An aboriginal scout accompanies the soldiers. (Reconstitution by G.A. Embleton (Parks Canada.))

Frenchtown was not the only victory the defenders of Upper Canada gained that winter. On the morning of 22 February, a combined British/Canadian force that included thirty Tyendinaga Mohawk warriors crossed the ice of the frozen St. Lawrence and took the American village of Ogdensburg after a short but sharp battle. Thereafter, the tide began to turn as the United States successfully mobilized its superior manpower to launch major offensives. At the end of April 1813, an American amphibious expedition attacked York, overwhelming the defenders who included forty Ojibway and Mississauga warriors. The Americans captured and burned the capital of Upper Canada.

A month later, the Americans made another successful landing at Fort George, at the mouth of the Niagara River, forcing the British and their Aboriginal allies in the Niagara peninsula to retreat west to where the modern city of Hamilton stands. A British victory during the night action fought at Stoney Creek on 6 June, however, caused the invaders to withdraw to the fortified camp they had constructed near Fort George and it was not long before British regulars and Canadian militia, together with their Aboriginal allies, closed in around the American position.

Two Ottawa Chiefs who with others lately came down from Michillimackinac, Lake Huron to have a talk with their Great Father, the King or his representative.

Watercolour depicting a group of Aboriginal Chiefs, possibly at Bois Blanc Island near Amherstburg, Ontario. Circ 1813-20. (Library and Archives Canada (C-14384.))

The American commander, Major-General Henry Dearborn, responded by mounting an expedition against De Cew’s House. This post was known to be the forward supply depot for the aboriginal warriors harassing his positions and was garrisoned by about fifty British soldiers under the command of Lieutenant James FitzGibbon. Unbeknownst to the Americans, a contingent composed of 200 Grand River warriors, 180 Seven Nations warriors, and 70 Ojibway and Mississaugas from Upper Canada, led by Dominique Ducharme and John Brant, were encamped about two kilometres east of FitzGibbon’s post, near an area of ponds and streams known as the Beaver Dams (close to what is now the modern city of St. Catharines).

On 23 June, a force of 600 American regular infantry and cavalry with three pieces of artillery, marched out of Fort George for De Cew’s House under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel Charles Boerstler. Contact was made just after dawn the next day, when Ducharme and Brant sprung an ambush from the woods lining both sides of the road through the Beaver Dams. The allied warriors devastated the American advance guard of regular cavalry, and then advanced through the cover of the woods on the American main force that was deploying. Though American musketry and cannon inflicted casualties, the warriors sniping and ‘their horrible yells terrified the enemy so much that they retired precipately’ into a hollow where they were then surrounded. Two hours later Lieutenant FitzGibbon carried a flag of truce. He informed Boerstler that the Americans were surrounded, not only by warriors from the Canadas but also those from the Northwest who were ‘by no means as easily controlled,’ and, as they ‘had suffered very severely they were outrageous and would commence a general massacre’ if Boerstler did not immediately yield. The Americans surrendered. FitzGibbon later wrote:

With respect to the affair with Captain [sic] Boerstler, not a shot was fired on our side by any but the Indians. They beat the American detachment into a state of terror, and the only share I claim is taking advantage of a favourable moment to offer them protection from the tomahawk and scalping knife.

The Battle of the Beaver Dams was one of the most notable Aboriginal victories of the War of 1812 – for a cost of not more than twenty killed and wounded, the warriors had killed, wounded or captured 600 American soldiers.

The twin victories at Stoney Creek and Beaver Dams blunted the American campaign in the Niagara peninsula, but to the west, Procter and Tecumseh, after a deep, but unsuccessful, offensive into the Ohio Territory, were forced back to Amherstburg. Even this position soon proved untenable as the British supply lines depended on their naval control of Lake Erie. The Americans had been feverishly constructing a squadron of warships at Presque’ Isle, on the southern shore of that lake to mount a challenge. In early September, they managed to wrest control of the Lake after sinking or capturing the British squadron in battle. When news of this disaster reached Procter, he decided to retreat toward Burlington Bay (now Hamilton Harbour). He neglected, however, to inform Tecumseh or the thousands of warriors and their families camped in and around Amherstburg. Their suspicions became aroused, however, when they saw the British dismantling the fortifications of the post and loading supplies and ammunition into wagons for a retreat. At a council between Procter, his officers and the Aboriginal leaders, held on 18 September 1813, Tecumseh delivered a stinging rebuke to his British ally that summarized the disappointments and disasters that regularly occurred when Aboriginal peoples became involved in European conflicts. In what later became known as the ‘yellow dog’ speech, Tecumseh castigated Proctor by likening him to ‘a fat animal that carries its tail upon its back; but when affrighted, it drops it between its legs and runs off.’

Procter’s mind was made up, however, and in late September his small army commenced a retreat towards Lake Ontario, accompanied by the reluctant Tecumseh and those of his followers who had not gone home in disgust at what they saw as another British betrayal. On 5 October, Tecumseh’s old opponent, Major-General William Henry Harrison, caught up with them near the Moraviantown mission on the Thames River. Procter deployed his regular infantry badly and they were run down by Harrison’s mounted troops, at which point the British general fled the battle. Tecumseh and his warriors fought well enough to let many of their British allies escape before they stubbornly retired through the woods. Tecumseh was not with them – killed during the battle, his body was spirited away by his warriors to be placed in an unknown grave. Harrison’s victorious troops included many Kentucky frontiersmen who displayed ‘peculiar Cruelty to the Families of the Indians who had not Time to escape, or conceal Themselves.’ The Americans remained in control of the southwestern portions of Upper Canada until the end of the conflict.

The last months of the year brought renewed success to British arms. In October and November, two American armies moving on Montreal were stopped by the twin victories at Chateauguay and Crysler’s Farm and Aboriginal warriors participated in both actions. But the disastrous defeat at the Thames, and the death of Tecumseh, marked the end of the military power of the Northwest peoples. Although some of the nations continued to fight on, and achieved some success at Prairie du Chien on the upper Mississippi in 1814, most of the nations either made a separate peace with the United States or fled to British territory.

Battle of Moraviantown on the Thames, 5 October 1813.

The defeat of the British and aboriginal force in this battle took place near modern London, Ontario. Tecumseh was killed in the fighting but his followers spirited his body away to be buried in an unmarked grave. (Library and Archives Canada (C-041031.))

Deputation of Aboriginal Nations from the Mississippi, 1814.

In the spring of 1814, a delegation of aboriginal leaders representing the nations of the west travelled to Quebec City to meet Sir George Prevost, the commander-in-chief, British North America. Note the sword worn by one of the warriors. Also note the black warrior. The adoption of strangers was much more commonplace in Aboriginal than in white society. This man was perhaps an escaped slave. (Library and Archives Canada (C-134461.))

The End of the War and the Treaty of Ghent

By 1814, the third year of the war, military campaigns were waged largely by increasing numbers of British and American regular troops who engaged in a number of pitched battles in the Niagara peninsula and Lake Champlain valley. Although the Aboriginal nations from the Northwest and their allies from the Canadas participated in some of these engagements, they did so as auxiliaries and their activities were less crucial to the outcomes of the battles.

In August 1814, negotiations to end the war began in the Dutch city of Ghent. Mindful of the disastrous omission of the Aboriginal peoples from the Treaty of Paris, which had ended the Revolutionary War, the British negotiators came to the table demanding that the Aboriginal allies of Great Britain should be included in the treaty and ‘a definite boundary to be settled for their territory.’ The Americans were even more shocked when they learned that ‘the object of the British government was, that the Indians should remain as a permanent barrier between our western settlements, and the adjacent British province,’ and that neither nation ‘should ever hereafter have the right to purchase, or acquire any part of the territory thus recognized, as belonging to the Indians.’ The British position was totally unacceptable to the United States, who had about a hundred thousand citizens living in the proposed Indian Territory. Negotiations stalled as a result.

After much discussion on the subject, the American delegates suggested instead that the final treaty include ‘a reciprocal and general stipulation of amnesty covering all persons, red as well as white, in the enjoyment of rights possessed at the commencement of the war.’ The British negotiators rejected this but, after consultation with London, they were instructed to drop the demand for the creation of a barrier state. Instead, they propose the following article for inclusion in the treaty:

The United States of America engage to put an end immediately after the ratification of the present Treaty, to hostilities with all the Tribes or Nations of Indians, with whom they may be at war at the time of such ratification, and forthwith to restore to such Tribes or Nations respectively all the possessions, rights and privileges, which they may have enjoyed or been entitled to in 1811, previous to the hostilities.

Provided always, that such Tribes or Nations shall agree to desist from all hostilities against the United States of America, their Citizens, and subjects, upon the ratification of the present Treaty being notified to such Tribes or Nations, and shall so desist accordingly.

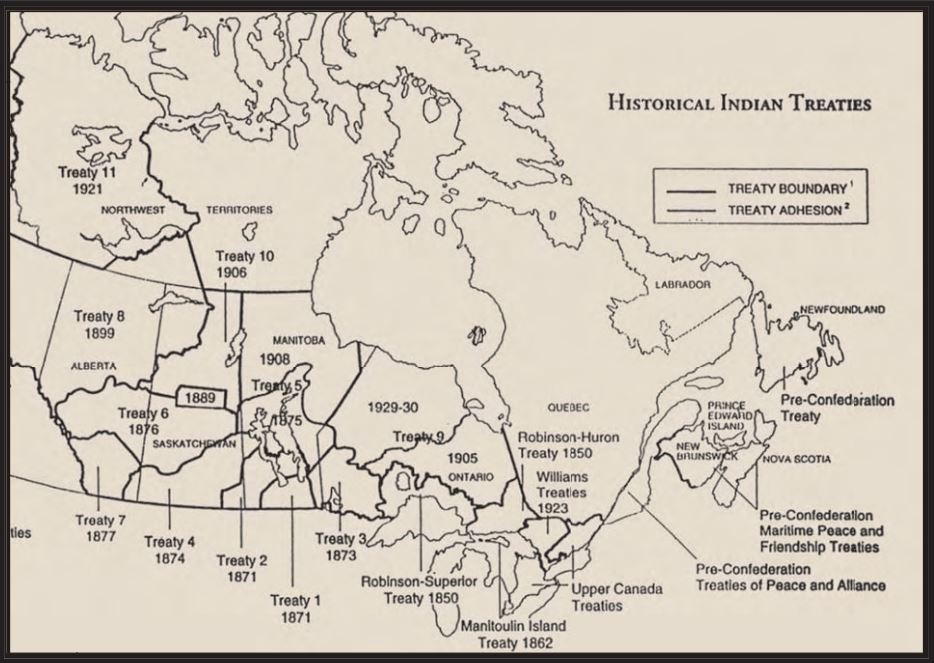

Historical Indian Treaties.

Following the War of 1812, British North American and U.S. border tensions stabilized somewhat while Aboriginal populations continued to decline and non-Aboriginal immigration increased dramatically. No longer courted as economic partners in peacetime, nor as military allies during war, British North American colonial governments came to regard First Nations as impediments to agricultural and industrial development. The subsequent expansion of the Canadian confederation was premised upon the assimilation of Aboriginal peoples and the attainment of their lands by treaty, legislation or otherwise. During this era, the extent to which Aboriginal peoples attempted to – or were permitted to – participate in various domestic or imperial military undertakings in support of the Crown varied from region to region and from decade to decade. (Archaeological Resource Management in a Lands Claim Context, Parks Canada, 1997)

There is little doubt that the Aboriginal peoples contemplated by the authors of this draft article were those residing on American territory, particularly those Northwest nations of Tecumseh’s Confederacy. The specific reference to the year 1811, when conflict broke out in the northwest, and not 1812 when the United States had declared war on Britain, makes this clear. After much discussion the American delegates accepted this proposal and it appeared as Article IX of the Treaty of Ghent, which was signed on Christmas Eve, 1814. Three days later, the British government sent a copy of the treaty to Sir George Prevost and drew his attention to the articles relating to Aboriginal peoples ‘that may be at war with either of the two contracting parties.’ Prevost was told to assure them that the Crown ‘would not have consented to make peace with the United States of America unless those Nations or tribes which had taken part with us, had been included in the Pacification.’ He was to use his ‘utmost endeavours’ to induce the Aboriginal peoples living in the United States to conclude separate peace treaties with the American government ‘as we could not be justified in offering them further assistance if they should persist in Hostilities.’

The War of 1812 secured the continued existence of British North America under British rule, and the role played by Aboriginal warriors in that defence had been substantial. Indeed in some of the early battles it had been decisive. Unfortunately, the outcome of the war was less positive for the Aboriginal peoples of the Great Lakes-Ohio region, as it marked the end of their long efforts to defend their autonomy and homelands from the European and American settlement frontier. Thereafter, the Native peoples of the Northeastern portions of the continent would not be able to defend themselves by military means. Yet 1815 would not be the last time that Aboriginal peoples were called upon to defend Canada.

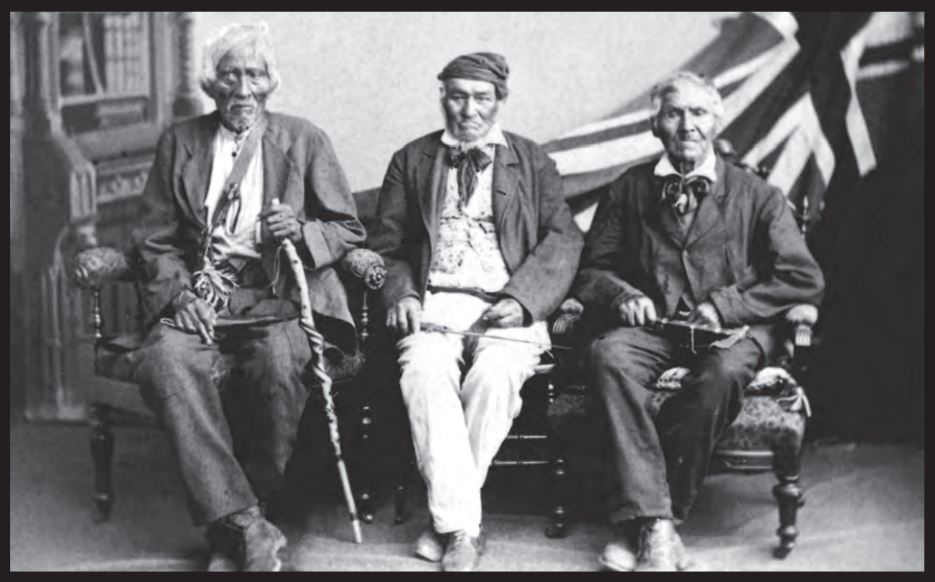

Studio photo taken in July 1882 of the surviving Six Nations Warriors who fought with the British in the War of 1812.

Throughout the remainder of the 19th century the personal example and high local profile of veterans like these ensured the survival of the military service tradition in Aboriginal communities across eastern and central Canada. Pictured from left to right in Brantford in 1882 are Grand River war of 1812 veterans Jacob Warner (aged ninety-two), John Tutlee (aged ninety-one) and John Smoke Johnson (aged ninety-three). (Library and Archives Canada (C-085127))

Related reading

ALEN, Robert S, His Majesty’s Indian allies: British Indian policy in the defence of Canada, 1774-1815, (Toronto : Dundurn Press, 2008).

BEN, Carl, The Iroquois in the War of 1812, (Toronto : University of Toronto Press, 1998).

MACLEOD, D. Peter, The Canadian Iroquois and the Seven Years War, (Toronto : Dundurn Press, 1996).

MORTON, Desmond, A military history of Canada: from Champlain to Kosovo, 5th ed., (Toronto : McClelland & Stewart, 2007).