Evaluation of Providing Services and Information to Canadians through Service Canada

On this page

- List of figures

- List of tables

- Executive summary

- Management response and action plan

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Service transformation and delivery through Service Canada

- 3 Findings

- 3.1 Responsibility and alignment with federal and departmental priorities

- 3.2 Meeting demonstrable needs for services and information

- 3.3 Accessibility and timeliness of service delivery across channels

- 3.4 Channel choice, channel mobility, and client satisfaction

- 3.5 Language

- 3.6 Meeting diverse needs for information

- 3.7 Awareness of the Canada Pension Plan Retirement Pension

- 3.8 Challenges meeting needs of population groups at higher risk of being vulnerable

- 4 Key conclusions and recommendations

- Appendix A – Evaluation questions

- Appendix B – Methods and limitations

- Appendix C – List of technical reports

- Appendix D – Provision of pension information in Australia and the United Kingdom

Alternate formats

Evaluation of Providing Services and Information to Canadians through Service Canada [PDF - 1.34 MB]

Large print, braille, MP3 (audio), e-text and DAISY formats are available on demand by ordering online or calling 1 800 O-Canada (1-800-622-6232). If you use a teletypewriter (TTY), call 1-800-926-9105.

List of figures

Figure 1: Service Canada’s service tiers

Figure 2: Access to pensions Specialized Call Centres, 2014 to 2015 to 2018 to 2019

Figure 3: Number of new and returning visitors to the Canada Pension Plan Retirement Pension website, December 2015 to April 2019

Figure 4: Use of channels by client need (stage of the client journey)

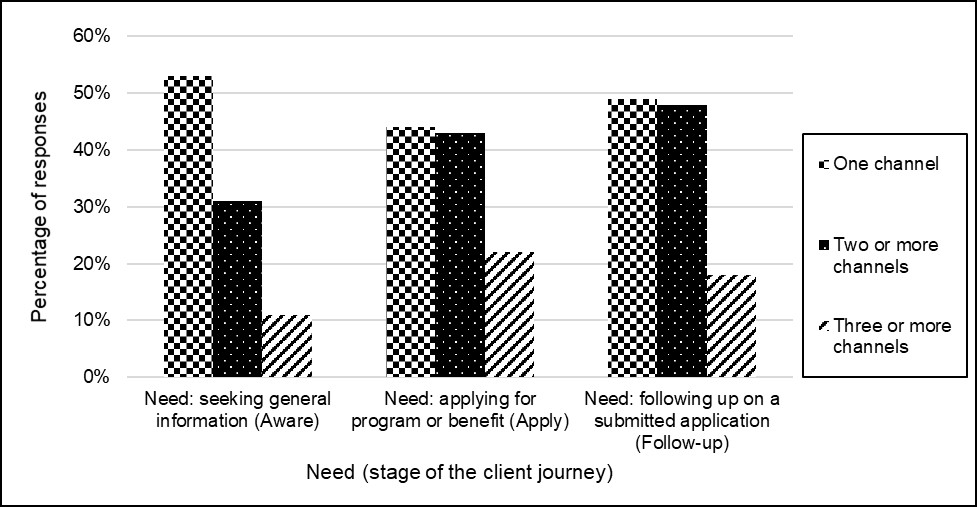

Figure 5: Number of channels used by client need (stage of the journey)

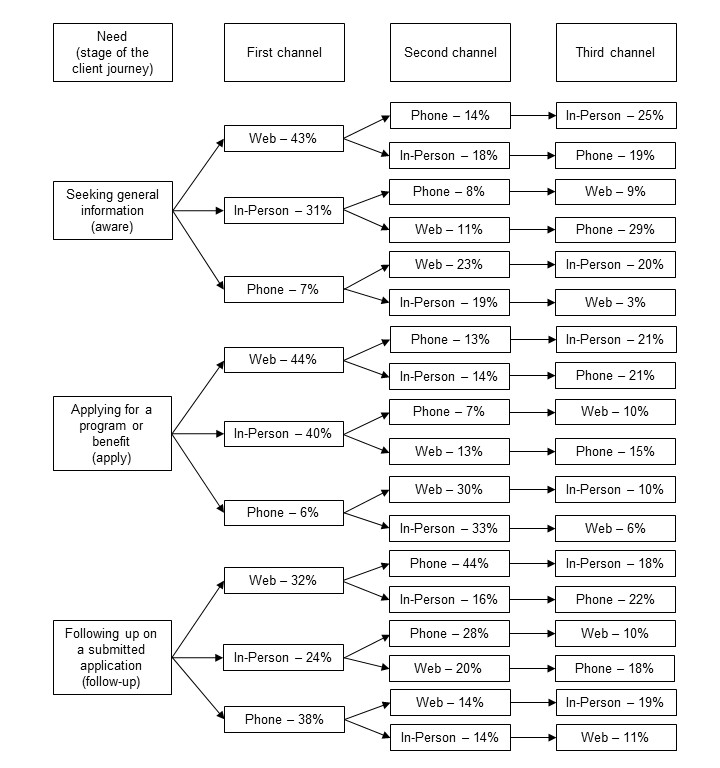

Figure 6: Channel mobility by client need

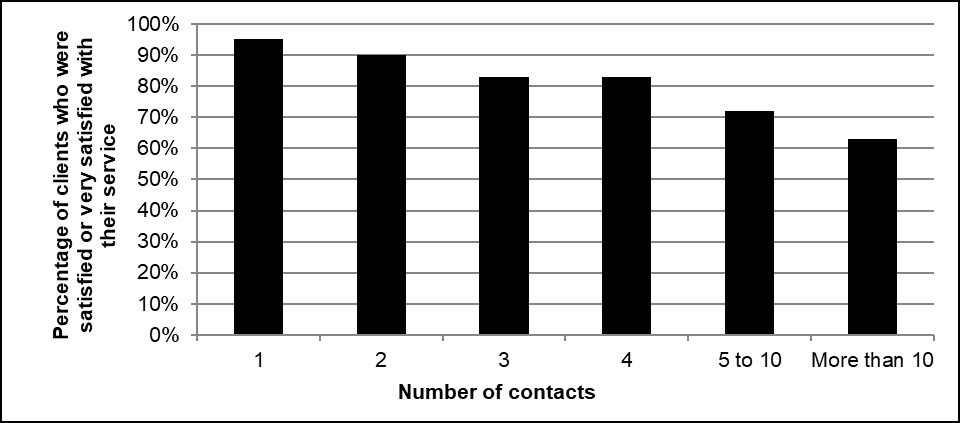

Figure 7: Client satisfaction by number of contacts with Service Canada

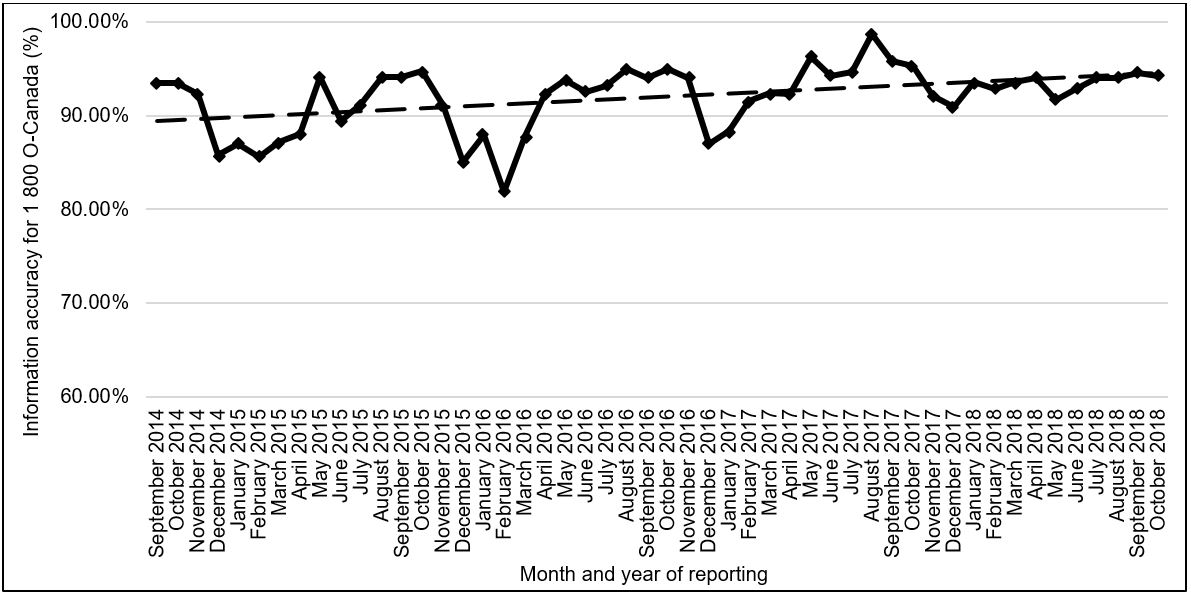

Figure 8: Information accuracy (%), 1 800 O-Canada

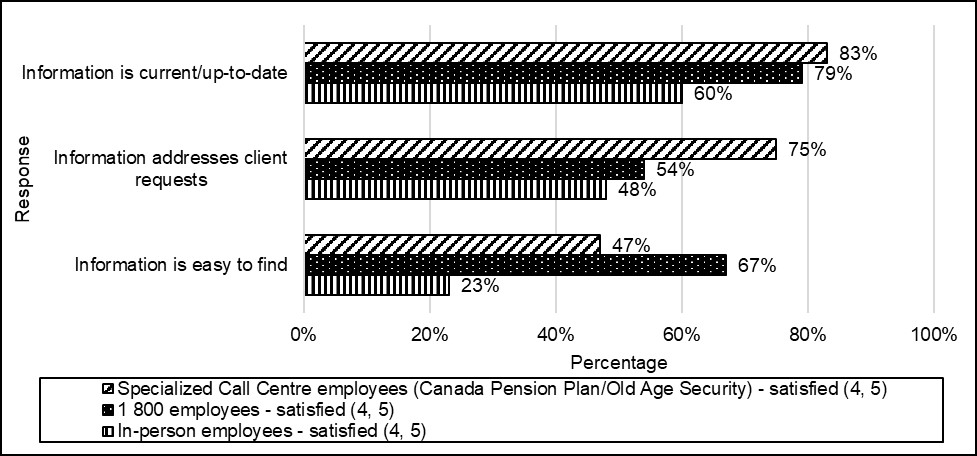

Figure 9: Employee satisfaction with reference tools

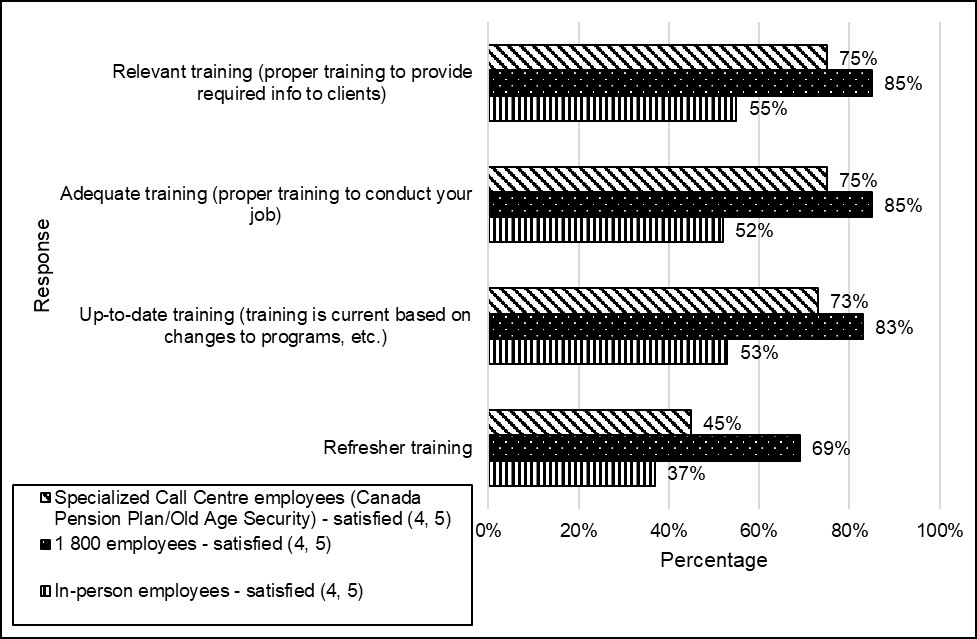

Figure 10: Employee satisfaction with training

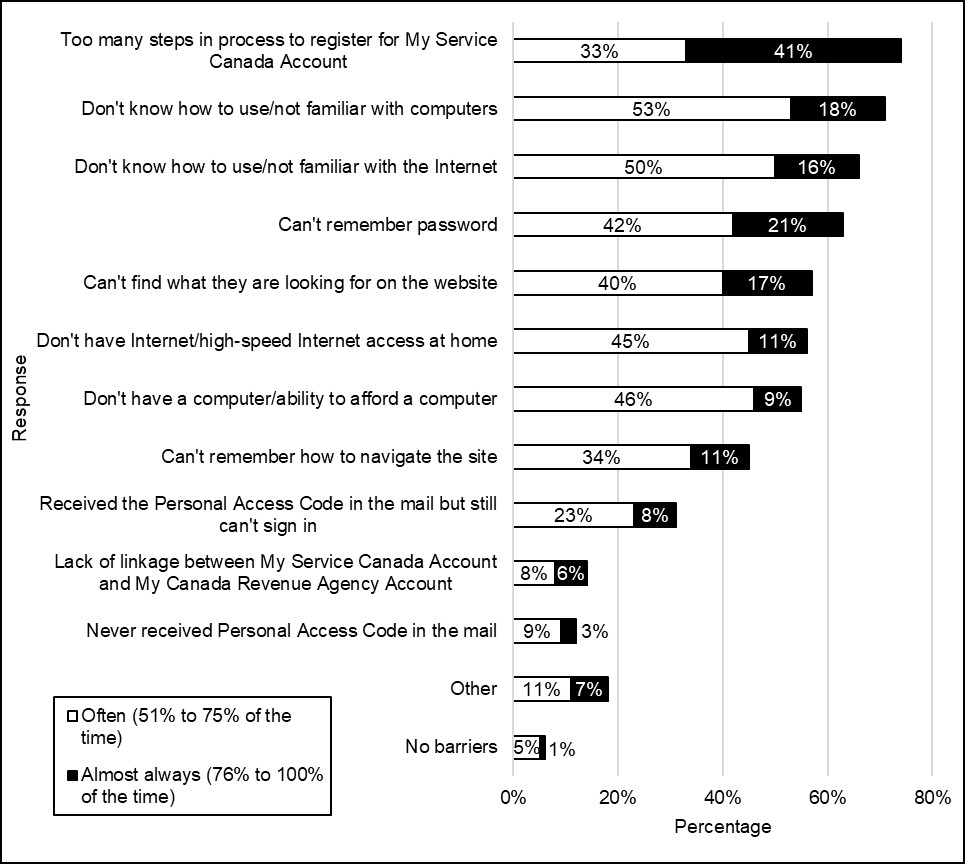

Figure 11: Digital services barriers experienced by clients as reported by employees (percent of survey respondents who reported the following barriers)

List of tables

Table 1: Outreach to Indigenous communities in 2018 to 2019

Table 2: Percentage of Employment Insurance, Old Age Security, and Canada Pension Plan mobile outreach events by target audience, April 2018 to March 2019

Table 3: First Nations reserves’ access to broadband Internet services (2011)

Executive summary

Evaluation purpose

This horizontal evaluation assesses the relevance and performance of Service Canada’s provision of general information and services (Tier 1) through 3 channels (in-person, telephone, and online) and the provision of personalized information and services (Tier 2) for the Canada Pension Plan Retirement Pension.

The evaluation focuses on the delivery of information and services for Employment Social Development Canada ’s 3 main statutory programs: Employment Insurance, Old Age Security, and the Canada Pension Plan Retirement Pension.

In particular, this evaluation assesses Service Canada’s contributions to ensuring clients’ ability to access timely services, and sufficient and accurate information through the service delivery channel that best meets their needs. It addresses key questionsFootnote 1 on the continued need for the services and information provided through the 3 channels; whether service delivery activities provide Canadians with easy, timely access to accurate information and services; and whether any barriers are encountered by different demographic groups.

Scope and methodology

The evaluation covers fiscal yearsFootnote 2 2014 to 2015 to 2018 to 2019 and provides evidence regarding results under Employment Social Development Canada’s core responsibility related to “information delivery and services for other departments”Footnote 3. This evaluation used a Gender-Based Analysis Plus lens to inform data collection and analysis, including by assessing how diverse groups of people may experience programs and initiatives differently.

Evaluation findings are based on 8 lines of evidence, as well as results from Service Canada’s Client Experience Survey (2017). Efforts were made to gather detailed and client-specific information on the Canada Pension Plan Retirement Pension. In some cases, this information provides the basis for generalizable findings relevant to client needs regarding the delivery of other programs.

Key findings and conclusions

Service Canada is meeting most client needs for access to services and general information, although challenges exist with timeliness and access to Specialized Call Centres

Most clients are able to access the services and general information they need through their preferred service delivery channel (in-person, telephone, and internet), in a timely manner, in the official language of their choice, and with a high level of client satisfaction.

For instance, results from Service Canada’s Client Experience Survey (2017) indicate high satisfaction rates with services among clients of the main statutory programs: Canada Pension Plan (87%); Old Age Security (86%); and Employment Insurance (83%).

Some exceptions include timeliness and accessibility challenges through specialized call centres. Key concerns related to access include high numbers of callers receiving High Volume MessagesFootnote 4 and being rerouted to an Interactive Voice Response system, and increased wait times and abandoned calls to Canada Pension Plan/Old Age Security Specialized Call Centres.

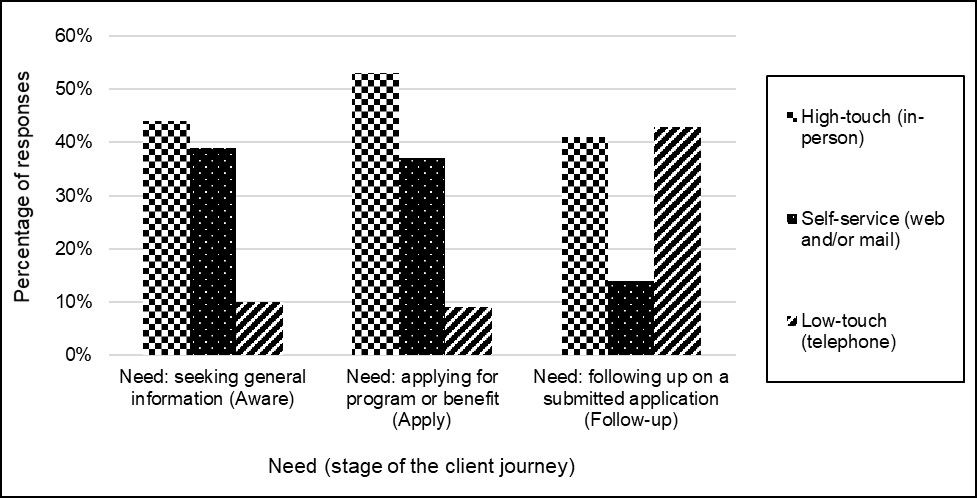

Movement between channels reflects that the service delivery model is functioning as designed, with many clients using multiple channels to obtain the information they are searching for. For instance, most clients reported using the in-person (44%); Web channels (39%); and telephone (10%) when seeking general information about a benefit or a program, according to the Service Canada Client Experience Survey (2017) results. The same survey found that most clients also apply for programs or benefits through the in-person (53%) or Web/mail channels (37%). The telephone (43%) and in-person (41%) channels are used more frequently than the Web channel (14%) for follow-up. Finally, clients seeking to solve problems tend to use the highest number of channels.

However, client satisfaction decreases on average as the number of times a client has to contact Service Canada increases. Some movement between channels could be resulting from clients’ inability to access required services/information at first contactFootnote 5. This was the case particularly for clients belonging to potentially vulnerable groups, who were not comfortable using the online channel, and preferred to obtain in-person assistance.

Regarding Specialized Call Centres, Report 1 of the 2019 Spring Reports of the Auditor General of Canada identified similar challenges and included recommendations for which the department will be undertaking the following actions:

- modernize the Canada Pension Plan and Old Age Security telephone system by May 2020

- complete a review of the new telephone system by March 2021

- continue to enhance and set service standards that are relevant to clients, in accordance with the Policy on Service

- include the capture of performance data on number of callers that hang up after the service standard time frame

Since the department has initiated efforts to address the concerns raised pertaining to Specialized Call Centers, additional recommendations are not required for this key finding.

Canadians need and expect improved information to support informed and optimal decision-making regarding complex programs such as the Canada Pension Plan Retirement Pension

General program information related to the Canada Pension Plan Retirement Pension, available through all channels, is not sufficient to support clients’ optimal decisions with respect to their Retirement Pension. For example, individuals must have personalized information such as how much they have contributed to the Canada Pension Plan over the contributory period and what their estimated benefit is in order to understand how this benefit amount might be affected by the various pension provisions including the age when they begin their pension.

However, personalized information is available through the Canada Pension Plan/Old Age Security Specialized Call Centres and “My Service Canada Account” online. In addition, only 31% of surveyed clients accessed their estimated benefits, 22% accessed their Statement of Contribution, and only 19% used the Canadian Retirement Income Calculator.

Clients were also found to lack knowledge of program details. For example, only 32% looked for information about the various pension provisions and only 3% of surveyed clients reported consulting a financial professional regarding when they should begin their benefit.

Some Canadians living in rural and remote areas as well as Indigenous people and people with lower levels of education experience barriers to accessing services and information they require

Some population groups experience greater challenges in obtaining services and information that meet their needs, as evidenced by the lower client satisfaction rates among Indigenous people and people with disabilities.

For instance, Client Experience Survey 2017 results indicate that Indigenous respondents had an overall level of satisfaction of 77% compared with 86% for non-Indigenous respondents. Results further indicate that Indigenous clients in general may face more difficulties finding and understanding the information they require, with only 64% of Indigenous clients reporting satisfaction with the ability to find information in a reasonable time compared to 79% of non-Indigenous respondents. In addition, only 73% of Indigenous respondents were satisfied that they understood the requirements of their application for a program or benefit compared to 81% of non-Indigenous clients.

Other population groupsFootnote 6 are at high risk of experiencing a range of non-digital and digital barriers. These population groups may be the least likely to know how to access the services and information needed to meet their needs. For instance, client survey and focus group results indicate that Canada Pension Plan Retirement Pension clients with lower levels of education are less likely to search for and use Government of Canada information to support informed and optimal decision-making. They are also more likely to begin their pension prior to age 65, thereby incurring a lifelong reduction in pension amount.

The literature review indicates that several population groups have a higher likelihood of experiencing digital barriers consistent with the 3 dimensions of Employment Social Development Canada's E-Vulnerability Index: Internet access (infrastructure and cost); comfortability; and competency. For example, some Indigenous people may experience challenges related to all 3 dimensions of e-vulnerability. At the national level, Internet access on all reserves is only 70% compared to 94% among other Canadian households, while access on remote reserves falls to only 57%Footnote 7.

Recommendations

- Explore innovative options to meeting clients’ needs for specific, personalized information about their Canada Pension Plan Retirement Pension

- Continue to identify and reduce barriers in accessing services and benefits amongst potentially vulnerable populations and explore inclusive approaches to providing those services

Management response and action plan

Overall management response

The Canada Pension Plan is 1 of 3 pillars of Canada’s retirement income system and a key element of the retirement security of Canadians. In fiscal year 2017 to 2018, 5.8 million individuals benefited from the Canada Pension Plan and more than 302,432 individuals applied for their Retirement Pension.

The decision of when to begin receiving the Canada Pension Plan Retirement Pension is complex. It requires clients to consider their Canada Pension Plan contributions and other sources of retirement income, their relative financial wealth, needs, general health and anticipated life expectancy. As indicated in the Canada Pension Plan Retirement Pension Survey, clients “don’t know what they don’t know”. To assist clients in making well-informed decisions about their Canada Pension Plan Retirement Pension, especially in regards to the implications of starting to collect the Retirement Pension at different ages, information and tools are available both to individuals who continue to work and those who will stop working.

The Canadian Retirement Income Calculator tool allows clients to estimate their retirement income. The calculator helps clients better understand how each level of the retirement income system will contribute to their future financial security and to provide a thorough understanding of the public pension system. Likewise, My Service Canada Account is a secured and personalized website that lets clients view their monthly estimated Canada Pension Plan benefits and apply for their Retirement Pension. In addition, through Canada.ca’s Public Pensions link, the department provides information on the Retirement Pension and other Canada Pension Plan benefits. Recently, a number of brief videos have been developed which describe the Canada Pension Plan, and the implications of starting to collect the Retirement Pension at different ages, for both individuals who continue to work and those who stop working. In addition, a letter is sent to clients at age 59 and 64 to inform them of their options. The letter includes the client’s Statement of Contributions to help them estimate their Canada Pension Plan Retirement Pension amount.

The department joined in a Government-wide multi-media advertising campaign targeting seniors, their families and stakeholders. The ad campaign raised awareness of services benefiting seniors, including the Canada Pension Plan, and directed visitors to our informative campaign page: Canada.ca/seniors. The campaign informed and engaged Canadians on how the Canada Pension Plan works to support Canadian retirees and how the program is being strengthened for future generations. As well, to help Canadians make informed decisions about their retirement, in spring 2019, the Public Affairs and Stakeholder Relations branch engaged working Canadians aged 30 to 59 on the Canada Pension Plan deferral and Canada Pension Plan enhancements through our “It’s Your Choice-Canada Pension Plan Marketing Campaign.” Using innovative communications tools, the campaign built increased awareness by generating more than 15,000 Facebook impressions, nearly 150,000 Twitter impressions, more than 40,000 LinkedIn impressions, almost 7,000 video plays and collecting close to 4,500 responses to a quiz gauging comprehension of key messaging.

Management recognizes that even with the current information, tools, and campaigns, clients face challenges in understanding the intricacies of the Canada Pension Plan to make the optimal decision as to when they should take their Retirement Pension. Through continuous improvements, the department will keep on developing and improving its information, tools and services to meet client’s needs.

Recommendation #1

Explore innovative options to meeting clients’ needs for specific, personalized information about their Canada Pension Plan Retirement Pension.

Management response

Management agrees with Recommendation #1. Given the complexity of the Canada Pension Plan Retirement Pension, the department recognizes that some clients will need more information to help them to make informed and optimal decisions by providing them with sufficient information early on. This includes helping clients increase their knowledge of the program and how it relates to their personal situation, accessing key information and tools to make the best decision possible as to when to take their pension, especially for clients with lower levels of education.

Currently, Benefits Delivery Services in cooperation with the Citizen Services Branch and Income Security and Social Development Branch continues to refine the Canada Pension Plan Retirement Pension Web pages on Canada.ca for ease of navigation, use of plain language, and organization of client-centric information. Since the evaluation period, Benefits Delivery Services has started to assess the possibility to personalize its letters to provide more detailed information on options. As presented in the management action plan table that follows, beginning in fiscal year 2019 to 2020 and moving forward in fiscal year 2020 to 2021, Benefits Delivery Services, in consultation with Income Security and Social Development, will explore innovative options to meet clients’ needs for specific, personalized information on their Canada Pension Plan Retirement Pension options.

Management action plan

1.1 Improve our communications with clients by continuing to update Canada Pension Plan Retirement Pension Web information and letters and forms. Assess the possibility to provide more client centric information in communications with clients, including outlining what options are available to clients and the potential implications of those options. This will include a review of international best practices to inform this assessment.

Completion date: March 2021

Recommendation #2

Continue to identify and reduce barriers in accessing services and benefits amongst potentially vulnerable populations and explore inclusive approaches to providing those services.

Management response

Consistent with the evaluation findings, the factors for non-participation are diverse and it is important to consider how social, personal and overlapping circumstances can exacerbate them. Thus, the quantitative and qualitative portions of the 2019 to 2020 Client Experience Survey project will explore these issues to improve our understanding and inform measures to address them. To date, we are identifying best practices in our outreach to remote and reserve communities, and pilots are underway in 6 cities.

Management action plan

2.1 Target the quantitative and qualitative components of Employment Social Development Canada’s third annual Client Experience Survey, to generate actionable insights to the barriers and challenges experienced by Service Canada clients.

Completion date: Summer/Fall 2020

2.2 Conduct targeted outreach pilots in 6 urban Indigenous communities through the Indigenous Outreach Program, to assess the effectiveness of various models in reaching vulnerable populations in urban settings.

Completion date: Winter 2020

1 Introduction

1.1 Evaluation objectives and scope

The evaluation addresses the following overarching questions:

- to what extent is Service Canada meeting clients’ needs by providing information and services that are accurate and easy to understand, timely, and easy to access through its 3 service delivery channels?

- do various population groups experience any specific barriers with regard to their use of the 3 channels?

Appendix A presents the full list of evaluation questions which were approved by the Performance Measurement and Evaluation Committee on July 13, 2016.

The evaluation takes a horizontal approach to understanding Service Canada’s contributions to client outcomesFootnote 8 by examining the provision of services and information for 3 major statutory programs (Employment Insurance, Old Age Security, and Canada Pension Plan Retirement Pension) through the 3 main service delivery channels (in-person, telephone, and Internet).

The evaluation covers fiscal years 2014 to 2015 to 2018 to 2019 and includes general information and services provided through Tier 1 services for the 3 main statutory programs. The evaluation also assesses the provision of personalized information and services for Canada Pension Plan Retirement Pension as provided through Canada Pension Plan/Old Age Security Specialized Call Centres in Tier 2. Figure 1 outlines the multi-channel, multi-tier model.

Figure 1: Service Canada’s service tiers

Source: Adapted from Service Canada, In-Person Operations (2017).

Figure 1: text description

An image depicting Service Canada’s Multi-Channel Service Delivery Model at the time of the evaluation reference period. From left to right, a box representing clients abuts 3 boxes representing the 3 Tier 1 service delivery channels. From top to bottom, these boxes represent Canada.ca, 1 800 O-Canada, and Service Canada Centres/Community Outreach and Liaison Service. Each box has a list of services offered to clients through the channel in question.

Canada.ca:

- information about programs

- links to tool and online application forms

- video tutorials for selected programs

- search engine

1 800 O-Canada:

- needs assessments

- general information about Government of Canada programs

- teletypewriter service for the deaf and speech-impaired

- pathfinding

- referrals

- promotion of self-service tools

- mail out information packages/brochures

Service Canada Centres and Community Outreach and Liaison Services include:

- needs assessments

- general information about Government of Canada programs (bundling)

- promotion of self-serve tools (Web)

- assisted services for people with special needs

- warm transfer to Tier 2 call centres

- application intake and review for completeness

- client file account maintenance

- validation of citizenship documents

- Social Insurance Number issuance

- collect fees (debts)

- claimant information sessions

- hosting Social Security Tribunals hearings

An arrow pointing to the right shows the flow of some client inquiries from Tier 1 services to Tier 2 services. A box represents Specialized Call Centres, and lists the services provided:

- entitlement/eligibility determination

- authentication of applicants

- payment issuance

- client call backs

- account maintenance

- provide explanations to clients

- escalate issues to Tier 3

Another arrow pointing to the right shows the flow of some client inquiries from Tier 2 services to Tier 3 services. The arrow points to a box with a list of Tier 3 services:

- policy interpretation

- liaison with policy department

- appeals

- decision on complex cases

A box runs below the entire image. It lists the following activities that support the 3 service tiers:

- client segment research and analysis

- tracking and reporting capabilities

- proactive mail-outs

- quality management

- marketing

- other support services

- client satisfaction measurement

- client feedback analysis

1.2 Methodology

This evaluation used multiple lines of enquiry to assess Service Canada’s contributions to clients’ ability to access timely services and sufficient and accurate information through the service delivery channel that best meets their needs. By way of examining the Canada Pension Plan Retirement Pension in detail, specific findings were used to further bolster general findings presented in this report. Some of these findings were found to be relevant to client needs regarding the delivery of other programs.

A Gender-Based Analysis Plus lens was applied to this evaluation to inform data collection and analysis, and to assess any difference in needs and barriers in the delivery of services and information across diverse groups of people. Issues related to determination of eligibility for benefits, as well as the accuracy of payments, are outside the scope of the evaluation.

8 lines of evidence, and 1 study conducted by Service Canada support the evaluation findings found in this report:

- survey of Canada Pension Plan Retirement clients - 2,017 completed surveys by recent beneficiaries of the Canada Pension Plan Retirement Pension. A Gender-Based Analysis Plus approach informed analysis of survey data to produce findings concerning vulnerable populations

- client focus groups – 20 focus groups (total 133 participants) with recent applicants to Canada Pension Plan Retirement Pension in urban, rural and remote areas across Canada, and in both official languages. Efforts were made to ensure focus groups were conducted with potentially vulnerable populations including Indigenous people and immigrants

- survey of Service Canada front line employees (1 800 O-Canada, Canada Pension Plan/Old Age Security Specialized Call Centre agents, and in-person Citizen Service Officers) with a total of 1,205 completed surveys

- key informant interviews – 62 semi-structured interviews with program officials and other stakeholders

- administrative data review – Administrative data from Service Canada call centres, in-person points of service and the Canada Pension Plan/Old Age Security Specialized Call Centres

- Web analytics – data on the online service delivery channel from December 2015 to December 2017 for Canada Pension Plan Retirement Pension webpage onlyFootnote 9

- literature review – academic literature, grey literature, media coverage, and internal government research on service delivery and modernization initiatives from 2006 to 2019

- document review –120 documents from 2011 to 2019 provided by partners in Service Canada, including National Scorecards

This evaluation also used evidence from Service Canada’s Client Experience Survey – a 2017 Service Canada survey of 4,000 clients of 6Footnote 10 Employment Social Development Canada programs about their experiences and satisfaction with their client journey.

Refer to Appendix B for a more detailed description of the evaluation methods used, including the 8 lines of evidence.

Refer to Appendix C for a list of the 8 corresponding technical reports (available upon request) that informed this interim report.

2 Service transformation and delivery through Service Canada

2.1 Service transformation

For nearly half a century, the Government of Canada has been working toward improving how it delivers services to the publicFootnote 11. At the same time, service delivery in the private sector has evolved rapidly through ever-advancing technologies. Clients increasingly expect the delivery of government services to keep pace – digital, easy to access, available at any time, and accompanied by timely assistanceFootnote 12,Footnote 13. Currently, there is a trend whereby Canadians are “more critical in and demanding of their interactions with government and business, putting pressure on [client] satisfaction”Footnote 14.

In a context of changing constraints and priorities on cost-efficiency, a global move towards increased use of modern digital services, and the changing expectations and demands of clients, Employment Social Development Canada has committed to transforming its service delivery approach to enhance the service experience. 1 of Employment Social Development Canada’s major undertakings over the past decade has been to improve the delivery of Employment Insurance. Noteworthy is that the evaluation of Employment Insurance Automation and ModernizationFootnote 15 and the Employment Insurance Service Quality ReviewFootnote 16 recommended the enhancement of the antiquated technology systems being used. Employment Social Development Canada’s response to these findings included new financial investments in specialized call centres and processing.

These efforts are ongoing and range from broad initiatives spanning multiple programs, such as Benefits Delivery Modernization, to more program-specific strategies, such as the Old Age Security and Canada Pension Plan Service Improvement Strategies. The Service Improvement Strategies have identified potential cost savings by way of modernizing information technology infrastructure, automation and e-services to Canadians. Information technology and e-service transformation activities are intended to address risks such as aging infrastructure, potential increased costs of delivering services, and the potential inability to meet future service demand. Implementation risks, such as service disruptions, are also possible.

Other innovative examples include outreach visits by Service Canada to all Indigenous communities in 2016 and 2017 to provide services and information on Canada Child Benefit applications. Budget 2018 provided additional funds to support outreach to all Indigenous communities, in order to increase uptake and reduce barriers related to service and information delivery that Indigenous people may face when trying to obtain benefits. As a result, over 700 Indigenous communities are engaged each year through Community Outreach and Liaison Service and visited at the request of the community.

The Employment Social Development Canada Service Strategy (2016) is the current key strategic planning document that covers all of the department’s service delivery modernization initiatives. It supports government wide service priorities and policy work on improving service delivery by aiming to modernize services in line with Canadians’ expectations through the following principles:

- client-centric – responsive to current and emerging client needs

- digital – secure and easy to use

- collaborative – connected through integrated and seamless collaboration and partnerships

- efficient and effective – providing value for money

- service excellence – based on a strong innovative service culture and engaged workforce

The department’s multi-year Service Transformation Plan (2017) outlines short, medium, and long-term opportunities and key goals including increased access, experience, timeliness and quality in service delivery. Through the use of design thinking in consultation with clients, employees, and private-sector experts, client-centric solutions have been identified under the following 5 themes:

- Allow Me – allow citizens and clients to apply for benefits/services in a faster, more efficient manner

- Trust Me – enable better ability for clients to apply for benefits/services faster by leveraging known data about the client. Clients will feel trusted and recognized

- Tell Me – give more information about the benefits and services and have multiple means of efficiently communicating

- Hear Me, Show Me – increased ability for clients to provide feedback and answer their questions

- My Choice – provide multiple options to engage with Employment Social Development Canada, allowing clients to choose how they want to interact and receive benefits and services

The Service Transformation Plan aims at a future in which clients receive world class, high quality, timely services wherever they are in Canada, supported by dedicated Service Canada employees. The plan indicates that such enhanced client-centric service delivery will help Employment Social Development Canada achieve policy and program results, and ultimately build trust in government.

Solutions and improvements are underway in each service delivery channel and tier. Initiatives include website updates, new call centre systems, and re-organized outreach efforts through Community Outreach Liaison Services in a manner which improves access for clients.

Online, Canada Pension Plan and Old Age Security clients can now access more self-serve options, such as viewing account information related to benefit payments, requesting a child rearing provision, and giving consent to authorize individuals to communicate on the client's behalf. Additional transformation activities are planned or ongoing.

In addition to these transformation efforts, the department is developing the Call Centre Improvement Strategy to frame the transformation plan for Specialized Call Centres (Tier 2). This strategy is a transformation initiative that will leverage industry best practices and implement ongoing business and technology improvements to increase accessibility and enhance services to clientsFootnote 17.

Finally, Employment Social Development Canada and Service Canada have also been producing research on the client journey, client experience, and service delivery for population groups at higher risk of being vulnerable. These research activities are conducted in support of transformation initiatives and to help inform future service improvements.

Administrative documents indicate that the Service Management Committee sets strategies and priorities for service delivery across the department. Responsibilities include overseeing service transformation, ensuring alignment between policy and service delivery, making decisions related to the department’s service delivery mandate, and monitoring performance related to service delivery and service transformation. The Service Transformation Committee oversees implementation of the Service Strategy and Service Transformation Plan at the Assistant Deputy Minister level.

Although the service transformation initiatives form an important part of the context in which the evaluation is conducted, they are not themselves under evaluation in this project.

2.2 Service delivery through Service Canada

Introduced in 2005, Service Canada provides an integrated location where Canadians can access services and information for Employment Social Development Canada’s main statutory programs through in-person Points of Service, online or over the phone. Service Canada is the service delivery business line of Employment Social Development Canada and provides information about government organizations, programs, services, events and initiatives, including information on public consultation and citizen engagement activities.

Service Canada is a large, complex operation. Its channels differ in role, mandate, and activities, despite their overarching focus on clients, as illustrated in Figure 1Footnote 18.

General information and services across the channels (Tier 1)

For the 3 main statutory programs, general information and services (Tier 1) can be accessed through:

- in-person points of service (Service Canada Centres and Community Liaison and Outreach activities)

- online services (Canada.ca and previously, servicecanada.gc.ca)

- phone services (Telephone General Enquiries Service at 1 800 O-Canada)

In addition, the department proactively reaches out by mail to Canadians aged 64 years and 1 month regarding their eligibility for several benefits for which they may be eligible including Canada Pension Plan Retirement Pension, Old Age Security, and Guaranteed Income Supplement.

There are some differences between the channels in the provision of general services. For example, 1 800 O-Canada is limited to providing general information and making referrals as appropriate. In-person Citizen Service Officers may also provide additional services such as assisting clients with special needs, processing account maintenance (for example, address changes), and providing a transfer to Specialized Call Centres (Tier 2). In addition, 2 Employment Insurance transactions have recently been delegated to in-person Citizen Service Officers providing increased authority as part of the First Point of Contact Resolution initiative.

Personalized information and services across the channels (Tier 2)

Tier 2 information and services are those specific to clients’ personal files for the 3 main statutory programs. Clients can access these services and information directly through Specialized Call Centres and online through the secure My Service Canada Account portal. Specialized Call Centre agents can address informational and transactional enquiries that require detailed program knowledge and access to the client’s file. Examples include decision status enquiries, administrative file maintenance such as address changes, and the adjudication of some entitlement issues at first point of contactFootnote 19. Through the My Service Canada Account, clients may interact with Service Canada regarding their specific files for purposes such as changing their account details or applying for Employment Insurance or Canada Pension Plan Retirement Pension. Clients may also use the Citizen Access Workstation Service available at in-person Service Canada Centres to access Canada.ca general information or their My Service Canada Accounts.

In October 2018, there were a total of 607 in-person points of service available to Canadians across 4 defined regions: Western/Territories Region, the Atlantic Region, the Ontario Region and the Quebec Region. Approximately 50% of the in-person points of service are full-time Service Canada Centres and 3% are part-time centres. Most of the remaining locations are Scheduled Outreach Sites (40%), which are regularly-scheduled points of service located outside Service Canada Centres, and which offer similar services provided by Citizen Service Officers who travel from their “parent office”. The final 5% of offices are Service Canada Centres – Passport Services, which are offices that exclusively offer passport servicesFootnote 20.

Finally, there are 6 Canada Pension Plan/Old Age Security Specialized Call Centres located regionally across the country: 1 in the Atlantic Region, 1 in Quebec, 2 in Ontario, and 2 in the Western/Territories Region.

3 Findings

3.1 Responsibility and alignment with federal and departmental priorities

Providing clients with services and information about Government of Canada programs is a federal responsibility that is supported by Service Canada. Service Canada meets the current government policies and aligns with government priorities. Additionally, its 3 service delivery channels are strategically aligned with Employment Social Development Canada’s priorities.

The literature reviewed emphasizes that there is more than simply a commercial relationship between a government and its citizens and notes that clients are “usually also taxpayers and citizens, that is: bearers of rights and duties in a framework of democratic community. As taxpayers and members of a civic or democratic community, citizens ‘own’ the organizations that provide public services, and have civic interests that go well beyond their own service needs”Footnote 21.

Alignment with federal priorities

Service Canada’s provision of services and information to Canadians is aligned with existing policies. The federal government is responsible for delivering a wide range of services to Canadians and effectively communicating about these services. These responsibilities are guided by the Policy on Service and the Policy on Communications and Federal Identity. The Policy on Service is rooted in the principles of client centricity, operational efficiency, and a culture of service management excellence.

According to the Policy on Communications and Federal Identity, “communications are central to the Government of Canada’s work and contribute directly to the Canadian public’s trust in government”. The Government communicates with the public in both official languages to inform Canadians of policies, programs, services and initiatives, and of Canadians’ rights and responsibilities under the law. The Government also has a responsibility to communicate with Canadians to help protect their interests and well-being, and to promote Canada as a prosperous, diverse and welcoming country.

A key expected result of this policy is that “government communications products and activities are timely, accurate, clear, objective, non-partisan, cost-effective, in both official languages, and meet the diverse information needs of the public”Footnote 22.

Current Treasury Board policies emphasize the obligation to provide services to Canadians in the language and platform of their choice. In addition, the 2013 and 2016 federal budgets confirmed the priority of the federal government to shift to electronic publishing, examine opportunities to streamline Web presence, transform service delivery, and allocate significant financial resources to renewal across multiple departments.

Alignment with departmental priorities

One of Employment Social Development Canada’s core priorities is to ensure that Canadians are able to access high-quality, timely and accurate government information and services that meet their needs. This builds on previous Employment Social Development Canada priorities to ensure that Canadians have the information necessary to make informed choices about available programs and services, and are able to access these services and information in the most accessible and convenient way. The literature notes that these service priorities support other Employment Social Development Canada responsibilities to assist Canadians in maintaining income for retirement (including through the strengthening of Canadians’ pensions), and to help Canadians receive financial support during employment transitions such as job loss, illness or maternity/parental leave.

The Employment Social Development Canada Departmental Plan 2018 to 2019 describes the approach for delivering against Government priorities as Employment Social Development Canada’s 5 core responsibilities. Of particular importance is the core responsibility “to provide information to the public on the programs of the Government of Canada and the department, and provide services on behalf of other government departments”Footnote 23. Activities undertaken by the 3 service delivery channels subject to this evaluation are key to fulfilling this responsibility. Finally, Employment Social Development Canada’s Departmental Plan 2018 to 2019 states explicitly that “service delivery is fundamental to achieving Employment Social Development Canada’s mandate and contributes to the achievement of policy results”.

3.2 Meeting demonstrable needs for services and information

There is a continued need amongst Canadians and non-Canadians for Government of Canada services and information from all channels and tiers for a number of different programs. Potential challenges with obtaining services and information persist for more complex programs and for population groups that are at higher risk of experiencing 1 or more barriers. While several initiatives are underway across channels to improve service delivery, it remains important to provide multiple service delivery options to meet everyone’s needs.

There is an ongoing need for the federal government to provide services and information through all 3 service delivery channels. In fiscal year 2018 to 2019, Service Canada received 8.4 million client visits to in-person points of service (Service Canada Centres and Scheduled Outreach) (nationally). This number includes 1,943,080 Citizen Access Workstation Service sessions occurring throughout in-person Service Canada Centres across the country. On April 1, 2019, the total monthly number of visits to Canada Pension Plan Retirement Pension webpages was 252,742. 1 800 O-Canada received approximately 1.6 million calls in fiscal year 2018 to 2019.

Clients have various needs depending on the program they wish to access and on their personal characteristics. According to the Service Canada employees surveyed for the evaluation, clients across the 3 major statutory programs ask for similar types of general information, including how and when to apply, the benefit amount, when they would receive payment, and when they would receive a response about a current or previous inquiry.

Although there is general satisfaction with needs for government services and general information being met, several population groups may experience challenges having their needs met. For example, Service Canada’s Client Experience Survey (2017) results indicate that 2 thirds of Employment Insurance clients were confident their applications would be processed in a reasonable amount of time, leaving 1 third neutral or not confident. Approximately 3 quarters of Canada Pension Plan and Old Age Security clients who participated in the same survey reported it was easy to find information about the programs, and slightly fewer found that program information was easy to understand.

Findings from the Canada Pension Plan Retirement Pension focus group study suggest that the In-Person channel continues to provide a needed service option to individuals who experience difficulties or barriers using the online channel. Across all groupsFootnote 24, most of the participants who used the In-Person channel said they chose to do so because they were not comfortable with applying online, and wanted to be able to ask questions and get assistance if they needed it. They also wanted confirmation that they were completing their applications correctly and completely.

The survey of Service Canada employees also found that some clients tell front line employees about experiencing digital barriers to accessing services and information online. For instance, 57% of respondents reported that clients often or almost always tell them they cannot find what they are looking for online, and 74% reported that clients often or almost always tell them they do not know how to use or are unfamiliar with computers. (Refer to section 3.5.)

In regards to needs varying by personal characteristics, results from Service Canada’s Client Experience Survey (2017) indicate that 77% of Indigenous respondents were satisfied with the services they receivedFootnote 25, compared to 86% of non-Indigenous respondents. These results are consistent with evidence from an evaluation of the Guaranteed Income Supplement that suggests Indigenous seniors experience a general lack of trust in government and even a fear of interacting with it. (Refer to section 3.5.)

Employment Social Development Canada’s Departmental Plan 2018 to 2019 identifies several outreach initiatives specifically intended to assist Indigenous people to access the full range of federal social benefits. These initiatives are being implemented in Indigenous communities in rural and remote communities, in the North, and through urban pilots. It is beyond the scope of this evaluation to assess the extent to which these specific initiatives meet the needs of Indigenous people.

Efforts are ongoing throughout Service Canada, and Employment Social Development Canada writ large, to find innovative ways to better meet client needs, including improved performance measurement of activities and improved use of new technology. Examples of initiatives to improve client service from 2017 include the Service Canada Client Experience Survey, the development of an E-Vulnerability Index, continued tracking of complaints and reporting monthly on performance through national scorecards, etc.

A series of improvements are planned and underway across all 3 channels as part of the Service Transformation Plan, including a range of Web initiatives, Community Outreach and Liaison Services, and a new call center system platform.

Another innovative initiative is the partnership between Service Canada and the Government of the Northwest Territories. This partnership allows employees from the Government of the Northwest Territories to provide in-person services for Service Canada, and when necessary, transfer clients to a Service Canada agent by phone. As a result, 15 northern and remote indigenous communities in the Northwest Territories now have daily access to Service Canada services. Moreover, some Government Liaison Officers in the Government of the Northwest Territories can deliver these services in the local Indigenous language or dialect.

3.3 Accessibility and timeliness of service delivery across channels

Across the In-Person, Telephone, and Internet channels, most clients are able to access services and information in a timely manner, but accessibilityFootnote 26 and timeliness vary by channel and purpose of the interaction.

In general, wait times for in-person services are met, and most Canada Pension Plan Retirement Pension clients in particular confirmed in-person wait times are reasonable. The locations, schedules, and design of in-person services are generally accessible in one form or another for most clients.

Although Service Canada has continued to make greater efforts to target service offerings for potentially vulnerable populations, a small percentage of clients across programs may not be able to obtain services and information in person as easily or regularly as most.

Many clients, including Canada Pension Plan Retirement Pension clients, express satisfaction with general telephone and Specialized Call Centre service. However, challenges were noted in regards to accessing Specialized Call Centre agents, with many clients needing to phone more than once to speak to an agent.

In regards to timeliness, in recent years, Specialized Call Centres have not always met their wait time targets. Abandoned calls have increased significantly, and clients who report having to wait longer than the service standard times to speak to a call centre agent found the wait times to be unreasonable.

Meanwhile, the availability and use of online services has expanded. Most Canada Pension Plan Retirement Pension clients who go online for information on the program are satisfied with the service, many clients continue to use paper applications.

In addition to the In-Person, Telephone, and Internet channels, Service Canada continues to contact Canada Pension Plan Retirement Pension and Old Age Security clients proactively by mail to inform them of their eligibility or enrolment for these benefits.

In-person services – accessibility

As of October 2018, the in-person service delivery channel provides a network of 607 physical locations and over 700 Community Outreach and Liaison Service sites in Indigenous communities, where clients can access Government of Canada programs and services. This network consists of 317 Service Canada Centres, 247 Scheduled Outreach sites, 32 Service Canada Centres – Passport Services, and 11 service delivery partnersFootnote 27.

For most clients, the In-Person channel is meeting expected needs for services and information. Results of a survey of Canada Pension Plan Retirement Pension clients confirm this, with 86% of the 771 respondents who visited the Service Canada Centre agreeing the staff members were helpful, and that there were enough staff available. More generally, the Client Experience Survey (2017) results are consistent, indicating a satisfaction rate of 87% among Canada Pension Plan Retirement Pension clients, and overall client satisfaction rates (across 6 programsFootnote 28) of 89% for the In-Person channel.

For most clients, in-person services are geographically accessible. The Client Experience Survey (2017) results indicate that 91% of respondents who accessed services in person strongly agreed (78%) or agreed (13%) that it was easy to get to a Service Canada office. The same survey indicates that 90% of Canada Pension Plan Retirement Pension respondents found it easy to get to a Service Canada officeFootnote 29.

Similar results were observed in the survey of Canada Pension Plan Retirement Pension clients, which indicates that 88% of these clients that visited a Service Canada Centre agreed that the office was easy to get to. When surveyed, Service Canada front line employees also agreed that location, specifically locating Service Canada Centres in major urban areas is the most effective factor for in-person service delivery (85% rated as effective or very effective) followed by providing a sufficient number of Citizen Access Workstations (83%).

At the same time, findings suggest there may still be clients for whom accessing services in person may pose certain challenges pertaining to location, scheduling, and design of the services. These individuals are often part of population groups at higher risk of being vulnerable. For example, around 1.3 million Canadians (3.5%) live more than 50 km from an in-person point of service, which can pose a challenge to reaching services which can be made worse in the winter when weather conditions worsen. More specifically, Canada Pension Plan Retirement Pension focus group participants confirmed that distance and weather may pose challenges to accessibility. However, there was also a general understanding that more regular service in remote locations may not be possible.

In 2017, select Service Canada Centres allowed staff to assist clients through video chat from anywhere in Canada. Service Canada reported that clients who used the video chat kiosks found they made for a fast visit that provided a comparable experience to speaking with staff in-personFootnote 30.

In regards to specific populations, 63% of residents living in remote areas have regular access to in-person services through Service Canada Centres and Scheduled Outreach, compared to 92% of rural residents and 99.97% of urban residents. Many residents in remote locations are also Indigenous.

Through Scheduled Outreach services, Service Canada has made attempts to reach clients who experience location-based barriers to accessing full-time, in-person services and to address seasonal, emergency, or population-specific needs for services. These are part-time, in-person services offered on a regularly-scheduled basis at the same location each time, and are intended to improve Canadians’ awareness of and access to programs and service offerings.

Canada Pension Plan Retirement Pension focus group participants suggested a number of possible improvements to scheduled outreach:

- better advertisement, as some people were unaware of it

- allow scheduled appointments

- more frequent visits for outreach service in Northern Indigenous communities

Community Outreach and Liaison Services target populations at a higher risk of being vulnerable, including Indigenous persons, individuals with lower levels of income, visible minorities, people with disabilities, the homeless, and seniors.

An analysis of Service Canada administrative data from April 2014 to May 2017 shows that 40.5% of outreach events for the 3 main statutory programs targeted 1 or a combination of population groups at higher risk of being vulnerable, with an additional 45.4% targeting workers and 14.1% targeting other population groups (youth, families near-seniors, and the general public).

More recently, Community Outreach and Liaison Services has undergone a transformation to be more responsive to serving citizens in the absence of other sustainable sources. It has been designed to remove barriers and ensure substantive equality for all vulnerable Canadians. To accomplish this, there is an increased focus on engagement with partners and communities to develop an approach based on service delivery tailored to specific needs.

From April 2018 to March 2019, Community Outreach and Liaison Services engaged all Northern, remote and on-reserve Indigenous communities and visited 669 Indigenous communities, many on more than 1 occasion. In fiscal year 2018 to 2019, there were 4,065 transactional services provided for the 3 main statutory programs (refer to Table 1).

| Program | Transactional Volumes |

|---|---|

| Canada Pension Plan | 1,193 |

| Canada Pension Plan Disability | 189 |

| Old Age Security | 1,493 |

| Employment Insurance | 1,190 |

| Total | 4,065 |

Source: Employment Social Development Canada (2019), “The Evaluation of the Provision of Services and Information to Canadians: Administrative Document and File Review” technical report (internal document).

In addition to these visits, Community Outreach and Liaison Services targets vulnerable populations, including urban Indigenous, newcomers, people with disabilities and seniors. Administrative data from April 2018 to March 2019 shows that 52.7% of outreach events for the 3 main statutory programs targeted 1 or a combination of population groups at higher risk of being vulnerable (Table 2), with an additional 33.4% targeting workers and employers and 13.9% targeting other population groups.

| Population group | Percentage of outreach events that targeted the population group |

|---|---|

| Seniors | 25.80% |

| Low-income/homeless | 10.70% |

| Urban Indigenous people | 3.80% |

| Newcomers/Immigrants | 6.80% |

| People with disabilities | 5.60% |

| Workers | 22.10% |

| Employers | 11.30% |

| Other (families, general public, youth, near retirees) | 13.90% |

| Total | 100% |

Source: Employment Social Development Canada (2019). “The Evaluation of the Provision of Services and Information to Canadians: Administrative Document and File Review” technical report (internal document).

The accessibility of Service Canada infrastructure is another important feature to ensure that all clients can access the services. Service Canada’s Service Strategy Performance Measurement Framework lists accessibility as a measure of high-quality service. Most surveyed Service Canada front line employees (75%) agreed that providing accessible facilities and services is key to effective in-person service.

Service Canada’s efforts to improve access to services for a range of programs are ongoing. For example, in addition to the partnership with the Government of the Northwest Territories referred to in section 3.2, the Western Canada and Territories Region will implement the Remote Services Expansion and Remote Strategy that provides outreach for Government of Canada services to remote and vulnerable northern communities, according to Employment Social Development Canada’s 2018 to 2019 Departmental Plan. Through the pilot project, Government of the Northwest Territories service delivery employees provide some Service Canada services and information in up to 15 communities. Under the Service Transformation Plan, a toolkit, tools, and connectivity support are being implemented to help with outreach.

In-person services – timeliness

Analysis of administrative data from April 2014 to May 2017 indicates an upward trend in the national average wait time during this period and ranges between about 10 and 17 minutes depending on the time of the year. Wait times are highest in March and April, July and August, and December and January, which aligns with when the centres are most visited. These trends continue from June 2017 to March 2019 with the highest wait times in similar months, and the average wait time ranging between around 9 and 18 minutes.

Across all channels, employee survey results indicate that most employees (80%) rated their ability to provide clients with information quickly as very high or high (4 or 5 on the rating scale).

In-person Service Canada Centres have surpassed their service target for timeliness of service from fiscal years 2014 to 2015 to 2016 to 2017 with approximately 85% of clients served within 25 minutes at in-person Service Canada Centres. Regionally, all in-person Service Canada Centres have been able to meet the 80% target on an annual basis other than Ontario, which fell below the 80% target in fiscal years 2015 to 2016 and 2016 to 2017. Also, while the Western Region has been able to stay above the 80% target, administrative documents indicate it dropped by over 4% between fiscal years 2015 to 2016 and 2016 to 2017. Results of the survey of Canada Pension Plan Retirement Pension clients indicate that 82% of those who visited a Service Canada Centre thought the wait time to receive assistance was reasonable.

Phone service - accessibility

Clients can access services and information through the telephone using either 1 800 O-Canada (Tier 1) or program-specific Specialized Call Centres (Tier 2).

1 800 O-Canada

Looking at services across programs, results show that Canadians are able to access a 1 800 O-Canada agent with minimal level of effort. Most reach an agent on the first try and within the service standard of 18 seconds. Noteworthy, the National Performance Scorecard data indicate a downward trend in the number of calls about Canada Pension Plan and Old Age Security answered by 1 800 O-Canada from 247,225 in October 2014 to 201,067 in October 2018.

Specialized Call Centres

Evidence indicated that clients had a high satisfaction with Specialized Call Centers. While access to the Interactive Voice Response is 99.98%, there are times of the year where a high level of effort is required to reach an agent.

Survey results from Service Canada’s Client Experience Survey (2017) indicate overall client satisfaction rates of 82% among survey respondents who obtained services from Employment Insurance and Canada Pension Plan/Old Age Security Specialized Call Centres. Agents working in both types of call centres, when surveyed for the evaluation, agreed that knowledgeable staff, hours of operation, and providing services in both official languages are important factors for providing clients with effective access.

A higher level of effort may be required for Canadians to access an agent at a Canada Pension Plan/Old Age Security or Employment Insurance Specialized Call Centre. Service Canada’s Client Experience Survey (2017) shows that 45% were able to get through to a Specialized Call Centre agent in 1 call, and an additional 20% were successful in 2 calls. However, 28% needed to call 3 to 5 times, and 4% made over 5 calls before connecting with an agent.

The survey of Service Canada employees reported that clients continue to tell them they experience difficulties reaching Canada Pension Plan/Old Age Security Specialized Call Centres, with 81% of respondents hearing this comment from clients often or almost always.

Results from a survey of Canada Pension Plan Retirement Pension clients indicates that of the 12% of clients who reported using the Specialized Call Centre, 32% reported they were not able to get through to an agent on their first call, and further reported needing a median of 2 calls in order to reach an agent. However, 24% of these clients indicated that they never got through to a staff memberFootnote 31. Focus group results identify similar challenges issues with long wait times to get through to a call centre agentFootnote 32.

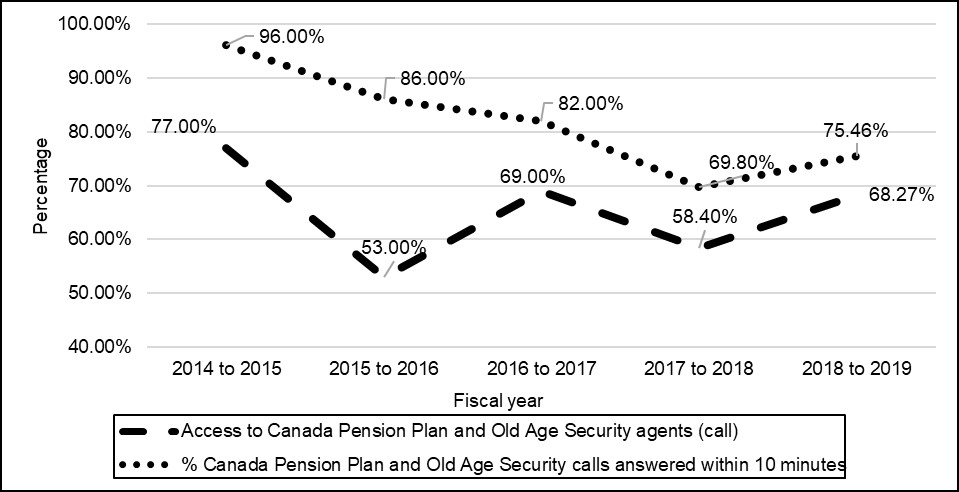

National Scorecard data shows a general decrease in the percentage of Canada Pension Plan and Old Age Security calls that get through to a call centre agent from 77.09% in fiscal year 2014 to 2015 to 68.2% in fiscal year 2018 to 2019 as demonstrated in Figure 2. National Performance Scorecard data further indicate a slight increasing trend in the number of Canada Pension Plan and Old Age Security calls resolved in the Interactive Voice Response (automated) system from 190,455 in October 2014, to 223,353 in October 2018. In fiscal year 2014 to 2015, no clients were blocked from accessing the Interactive Voice Response system and 905 calls were blocked in fiscal year 2015 to 2016. However, in fiscal year 2016 to 2017, 5,020 clients were blocked from accessing the Interactive Voice Response system due to higher call demand. This number fell to 3,373 clients in fiscal year 2018 to 2019.

According to Report 1 of the 2019 Spring Reports of the Auditor General of Canada, in fiscal year 2017 to 2018, a total of 4.9 million calls were made to the Canada Pension Plan/Old Age Security Specialized Call Centres in which the caller asked to speak to an agent. Of these, 49% (2.4 million) were answered by an agent. The rest of the calls were either prevented from reaching an agent (42% of cases), or the caller hung up (9% of cases)Footnote 33.

The department agreed with the Auditor General’s report’s recommendation that it will review how it manages incoming calls to improve access. The report also outlined some of the key commitments made by the department to improve the performance of the Canada Pension Plan and Old Age Security call centres. For example, on May 11, 2019, Canada Pension Plan/Old Age Security Specialized Call Centres migrated to a Hosted Call Centre solution, a modern technology to replace the outdated information technology of its call centre network, which has increased the percentage of callers able to reach an agent to 100%. The implementation of this solution includes the provision of larger call centre queues and resolves the technological limitation of the previous telephone systemFootnote 34,Footnote 35.

Challenges accessing Specialized Call Centres affect the demand on other channels. Key informants from Employment Social Development Canada noted that when the Specialized Call Centres do not have the necessary capacity to respond to demand, clients may turn to other channels for information, which they may not be able to provide. Key informants added that this has the potential to impact access to other channels, especially 1 800 O-Canada and in-person services, because of the increase in demand.

Phone service – timeliness

1 800 O-Canada

Across programs, timeliness of access to 1 800 O-Canada has been consistently high since 2014. Nearly 100% of calls to the centre are received, and approximately 80% of these calls are answered within the service standard of 18 seconds. According to employee survey data, employees working in 1 800 O-Canada are more likely than those in Canada Pension Plan/Old Age Security Specialized Call Centres to have a positive view on the effectiveness of their ability to answer calls in a timely manner.

Specialized Call Centres

The evaluation found that there has been a steady decrease in timely access to specialized call centres between fiscal years 2014 to 2015 and 2017 to 2018. National Scorecard data shows a decline in the percentage of Canada Pension Plan and Old Age Security calls answered by a Specialized Call Centre agent within the service standard of 10 minutes from 96% in March 2015 to 69.8% in March 2018, with an increase to 75.4% in fiscal year 2018 to 2019 as demonstrated in Figure 2. According to Service Canada, the decrease in calls answered within 10 minutes was the result of Canada Pension Plan/Old Age Security Specialized Call Centre agents helping with processing activities to reduce excess inventory of work. In addition, the Canada Pension Plan/Old Age Security Specialized Call Centres experience cyclical peaks in call volumesFootnote 36 which impact accessibility and timeliness. Yearly reporting in Figure 2 reflects averages across cyclical peaks and valleys.

Figure 2: Access to pensions Specialized Call Centres, fiscal years 2014 to 2015 to 2018 to 2019

Source: National Scorecard Data, Year to Date Results March 2015, 2016, 2017, 2018, and 2019Footnote 37.

Figure 2: text description

| Fiscal year | Access to Canada Pension Plan and Old Age Security agents (call) | % Canada Pension Plan and Old Age Security calls answered within 10 minutes |

|---|---|---|

| 2014 to 2015 | 77.00% | 96.00% |

| 2015 to 2016 | 53.00% | 86.00% |

| 2016 to 2017 | 69.00% | 82.00% |

| 2017 to 2018 | 58.40% | 69.80% |

| 2018 to 2019 | 68.27% | 75.46% |

Similarly, 76% of respondents in the Client Experience Survey (2017) reported having to wait more than 5 minutesFootnote 38 to speak to an agent, with 46% of clients waiting over 11 minutesFootnote 39. The majority of those that said they had to wait more than 11 minutes responded that they found these wait times to be unreasonable. This does not necessarily reflect abandoned calls,Footnote 40 which have been steadily increasing. It is important to note that over 90% of abandoned calls occur within the 10-minute threshold.

The Auditor General of Canada’s spring 2019 report indicates that 72% of calls were answered within 10 minutes, and that the average wait time was 5 minutesFootnote 41. This report further notes that respondents to a 2018 survey conducted by the Institute for Citizen-Centred Service’s indicated they expected to wait an average of 7 minutes when calling the Government of Canada. The report also highlights some of the efforts made by Employment Social Development Canada to ensure that client needs are taken into consideration. For example, a service standard review of the Canada Pension Plan and Old Age Security program service standard was recently completed in December 2018. The review included client consultations, and confirmed that established standards were relevant and consistent with client expectations. Moreover, the report also outlines further commitments made by Employment Social Development Canada to enhance its publishing of call centre service reporting, notably by increasing the frequency of reporting, and by including calls abandoned beyond the 10-minute service standard when reporting results from fiscal year 2019 to 2020 onwards.

Similarly, participants in a focus group study conducted with Canada Pension Plan Retirement Pension clients reported that wait times were very long, and they had to call back multiple times to speak to “the right person” who could not then answer their questionFootnote 42. In addition, participants reported they did not receive promised call-backsFootnote 43, nor were they able to obtain the information they needed, despite the fact they had been referred to the Specialized Call Centre by another channelFootnote 44.

General online services – accessibility

Substantial efforts have been made to increase and improve online service delivery. The creation of Canada.ca allows for program information from the 3 main statutory programs to be housed in 1 place online. A number of online tools are available to assist clients in understanding the programs and making decisions. These include the Benefits Finder Tool, the enhanced functionality of the Canada Retirement Income Calculator, and the expansion of the My Service Canada Account, which permits online applications for Canada Pension Plan Retirement Pension and Old Age Security, as well as allowing clients to link to their Canada Revenue Agency accounts. Service Canada’s Client Experience Survey (2017) found that 79% of clients were satisfied or very satisfied with the online channel.

Despite this, key informants suggest there is a need for better integration of some of the online tools (for example, the Benefits Finder Tool and the My Service Canada Account). They identified other gaps in the digital services offered including dated technology, not being user-friendly, not being well organized, and not being written in plain language. Half of the front line employees surveyed in the Service Canada employee survey indicated that clients could not locate relevant information on the Web and the Web information is not clear/sufficient/specific to their needs.

According to the Web Exit Survey of Employment Insurance clients who said they were successful applying online, or successful submitting an Employment Insurance report, 88% were very satisfied or satisfied with the amount of time it took them. Web Exit Survey results also indicate that of the clients who said they were successful in learning about or applying for the Canada Pension Plan, 79% were very satisfied or satisfied with the amount of time it took them.

Canada Pension Plan Retirement Pension online services – accessibility

A small percentage of front line employees surveyed indicated that they receive fewer client enquiries about applying for the Canada Pension Plan Retirement Pension since the application process was available online.

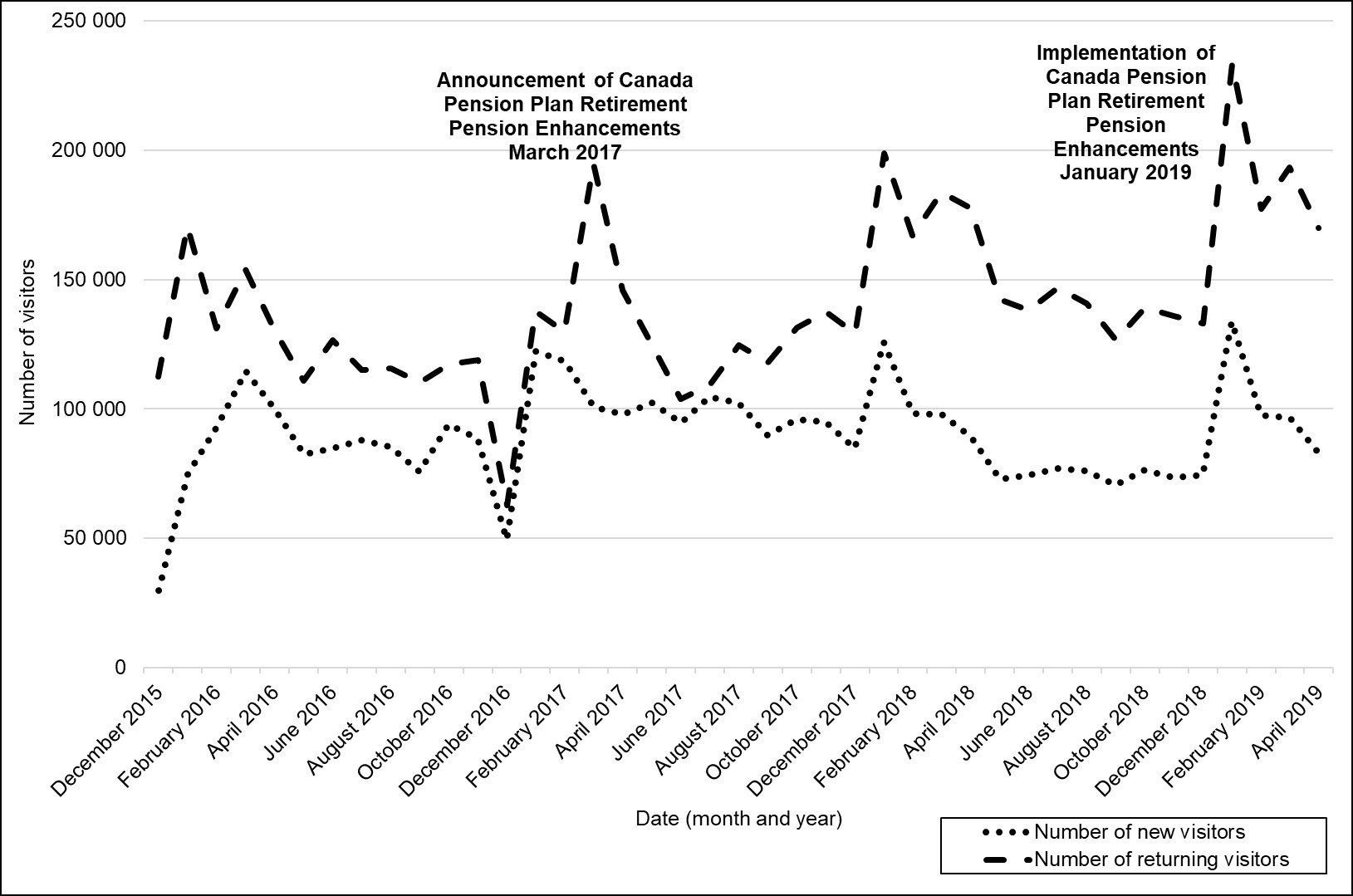

Figure 3 illustrates that the total number of new visitors to the Canada Pension Plan Retirement Pension webpages increased by 73% from December 2015 to March 2017. During the same period, the total number of returning visitors increased by 330%, with returning visitors outnumbering new visitors starting in June 2017Footnote 45. On April 1, 2019, the total monthly number of visits to Canada Pension Plan Retirement Pension webpages was 252,742.

Figure 3: Number of new and returning visitors to the Canada Pension Plan Retirement Pension website, December 2015 to April 2019

Source: Employment Social Development Canada (2018). “Providing Services and Information through Service Canada Evaluation: Web Analytics Technical Report” (deck), internal document.

Figure 3: text description

| Date (month and year) | Number of new visitors | Number of returning visitors | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| December 2015 | 29,876 | 112,352 | n/a |

| January 2016 | 74,848 | 170,514 | n/a |

| February 2016 | 92,964 | 130,945 | n/a |

| March 2016 | 114,418 | 153,987 | n/a |

| April 2016 | 99,639 | 130,468 | n/a |

| May 2016 | 82,317 | 110,763 | n/a |

| June 2016 | 84,542 | 126,495 | n/a |

| July 2016 | 87,879 | 115,053 | n/a |

| August 2016 | 85,495 | 115,530 | n/a |

| September 2016 | 75,643 | 110,286 | n/a |

| October 2016 | 94,077 | 117,119 | n/a |

| November 2016 | 88,674 | 118,867 | n/a |

| December 2016 | 49,435 | 62,554 | n/a |

| January 2017 | 122,144 | 137,793 | n/a |

| February 2017 | 118,385 | 129,651 | n/a |

| March 2017 | 100,635 | 194,615 | Announcement of Canada Pension Plan Retirement Pension Enhancements |

| April 2017 | 97,882 | 145,682 | n/a |

| May 2017 | 102,317 | 125,095 | n/a |

| June 2017 | 94,767 | 103,921 | n/a |

| July 2017 | 104,660 | 109,155 | n/a |

| August 2017 | 102,414 | 124,575 | n/a |

| September 2017 | 89,976 | 117,915 | n/a |

| October 2017 | 95,779 | 131,465 | n/a |

| November 2017 | 94,864 | 137,482 | n/a |

| December 2017 | 84,738 | 129,071 | n/a |

| January 2018 | 125,668 | 198,692 | n/a |

| February 2018 | 98,318 | 167,057 | n/a |

| March 2018 | 97,869 | 183,639 | n/a |

| April 2018 | 89,263 | 177,574 | n/a |

| May 2018 | 72,957 | 142,450 | n/a |

| June 2018 | 74,437 | 138,271 | n/a |

| July 2018 | 77,063 | 146,770 | n/a |

| August 2018 | 75,928 | 140,837 | n/a |

| September 2018 | 70,694 | 126,635 | n/a |

| October 2018 | 76,377 | 139,212 | n/a |

| November 2018 | 73,566 | 135,761 | n/a |

| December 2018 | 74,561 | 133,127 | n/a |

| January 2019 | 133,783 | 233,469 | Implementation of Canada Pension Plan Retirement Pension Enhancements |

| February 2019 | 97,466 | 177,370 | n/a |

| March 2019 | 96,421 | 193,265 | n/a |

| April 2019 | 82,882 | 169,860 | n/a |

The most visited pages included the main information pages: “Overview”, “Eligibility” and “How Much You Could Receive”. Moreover, Web analytics results indicate that between 2016 and 2017 visits to the Canadian Retirement Income Calculator, an information tool to help clients estimate benefits, outnumbered visits to the Apply page by a small amount. A possible interpretation is that visitors to the Canada Pension Plan Retirement Pension main pages are seeking information and could potentially be learning about the program.

Results of the survey of Canada Pension Plan Retirement Pension clients indicates that approximately 62% of clients surveyed accessed the website. Of these, a majority reported that information and instructions on the website were clear, easy to follow and understand. However, fewer than 40% of respondents agreed that the examples of different situations on the website helped them think about the best age to start Canada Pension Plan Retirement PensionFootnote 46. In addition, Service Canada’s Web Exit Survey results indicate that only 52% of those learning about or applying for the Canada Pension Plan find the information easy to understand.

Regarding the use of My Service Canada AccountFootnote 47, results of the survey of Canada Pension Plan Retirement Pension clients indicates that almost half of the respondents (45%) applied for their pension online through their My Service Canada AccountFootnote 48. A majority (70%) of these reported that registering for their My Service Canada Account was easy or very easy.

In the Service Canada’s Client Experience Survey (2017), 76% of Canada Pension Plan Retirement Pension respondents expressed that the My Service Canada Account was easy to use and 80% of those clients who used the online service to apply had a good overall experience with it. Focus group results are also consistent, although some participants found it problematic to request and wait for an access code.

However, slightly over half (52%) of surveyed Canada Pension Plan Retirement Pension clients did not apply online through the My Service Canada Account, primarily because the staff at a Service Canada Centre gave them an application to mail in or they chose to print and mail a paper application, they did not know how to apply online, or they did not have a computer. This is consistent with Web Exit Survey results indicating that only 48% of those who attempt to apply online are successful.

Results from the client survey and focus group study also indicate that specific groups of respondents encountered challenges in understanding information on the website, and applying online through My Service Canada Account. These include Indigenous and immigrant respondents, respondents with a disability, and respondents with lower levels of education and income. All of these groups were more likely to submit their pension application through a Service Canada Centre, preferring to seek assistance from the In-Person channel.

Key informants indicated that, although the website redesign has focused on Web content and easier to address issues, the online capacity for the Canada Pension Plan Retirement Pension is still limited as some information still must be mailed in. The standard Canada Pension Plan Retirement Pension application can be completed online through the My Service Canada Account, but specific provisions such as pension sharing, credit splitting for divorced or separated couples, and the child rearing provision may require additional documentation to be mailed in. These challenges may account for the fairly high number of unsuccessful online applicants noted previously.

Pensions-related mail-outs – accessibility