Employment Insurance Monitoring and Assessment Report for the fiscal year beginning April 1, 2017 and ending March 31, 2018

Chapter 3: Impact and effectiveness of Employment Benefits and Support Measures

From: Employment and Social Development Canada

On this page

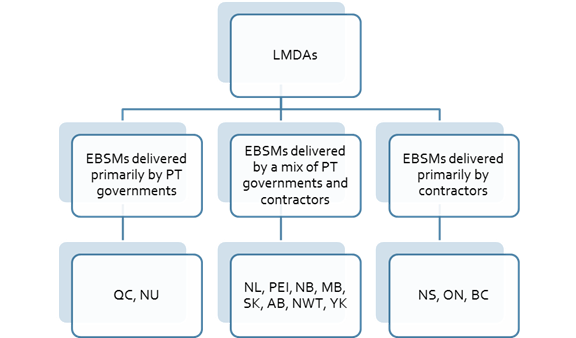

Activities delivered under Part II of the Employment Insurance (EI) Act help individuals in Canada prepare for, find and maintain employment. Under the umbrella of Employment Benefits and Support Measures (EBSMs), these activities include programs delivered by provinces and territories under Labour Market Development Agreements (LMDAs), as well as the Government of Canada’s pan-Canadian programming and functions of the National Employment Service (NES).

This chapter presents program results for EBSMs achieved under Part II of the EI Act during the fiscal year beginning on April 1, 2017 and ending on March 31, 2018 (FY1718). Section 1 provides a national overview of EBSM-similar programming delivered under the LMDAs and by Aboriginal Skills and Employment Training Strategy (ASETS) agreement holders. Provincial and territorial employment programming activities are presented in Section 2, with a description of each jurisdiction’s labour market and employment priorities. Section 3 presents a national and international overview of service delivery models, issues, and best practices for active employment programs comparable to EBSMs. Section 4 discusses the results of Employment and Social Development Canada’s (ESDC) delivery of pan-Canadian activities, and the administration of certain NES functions.

Notes to readers

- The data used to analyze EBSM activities were collected from provinces, territories, and ASETS agreement holders. Governments continue to improve data quality and collection to ensure accurate, reliable, and consistent information. While all data sets are verified before publication, systems and operational changes may affect the comparability of data from year to year.

- Throughout this chapter, references to average levels of activity and to highs and lows generally use the 10-year period from FY0708 to FY1718 as a frame of reference.

- Statistics Canada’s Labour Force Survey (LFS) is the source of labour market data reported. Data for Canada and the provinces are fiscal-year averages, calculated using seasonally unadjusted monthly data, while monthly references are seasonally adjusted. Data for the Northwest Territories, Yukon and Nunavut are calculated using unadjusted three-month moving averages of monthly data. In discussions of employment trends by industry, standard industry titles are taken from the North American Industry Classification System (NAICS).

- Real GDP data and other non-LFS macroeconomic indicators are from Statistics Canada’s Economic accounts. Forecasts are based on published analyses from the Bank of Canada, the Conference Board of Canada, Canadian banks, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development and Statistics Canada, as well as on internal analysis, using information available as of January 2019.

1. National overview

1.1 Economic and labour market context

In FY1718, Canada’s labour force grew by 1.0% to a total of 19.7 million, while employment expanded at a faster pace (+1.8%), to a total of 18.5 million. This marked the eighth consecutive year of employment growth in Canada, with most of the jobs being in full-time employment. Employment growth was similar among women and men, increasing by 1.8% and 1.9%, respectively.

Canada’s overall unemployment rate edged down to 6.1%, compared to 6.9% in the previous fiscal year. The unemployment rate for both women and men dropped by varying degrees. Women’s unemployment rate registered at 5.7% (compared to 6.2% in the previous year), while men’s unemployment rate registered at 6.5% (compared to 7.5% in the previous year).

Among youth aged 15-24 years old, employment grew by 1.4% in FY1718. In turn, the youth unemployment rate declined from 13% in FY1617, to 11.2% in the recent year. This is the lowest unemployment rate among youth since FY0708. Canadians aged 55 or older saw their employment levels grow up by 4.1%, and their unemployment rate declined from 6.0% to 5.5%, year over year.

Employment levels increased or remained relatively stable in most provinces and territories. Prince Edward Island (+3.3%) and British Columbia (+3.2%) experienced the strongest employment growth, followed by Quebec (+2.1%) and Ontario (+1.9%). Moderate growth was registered in Manitoba (+1.5%) and Alberta (+1.6). In Nova Scotia (+0.8%) and New Brunswick (+0.1%) employment levels remained relatively stable. Employment declined only in Newfoundland and Labrador and Saskatchewan, by -3.3% and -0.3%, respectively. In the territories, Yukon’s employment levels increased by 2.1%, while in Northwest Territories and Nunavut employment dropped by -4.9% and -1.3%, respectively.

Canada’s overall labour market participation rate held steady at 65.7% in FY1718, with the labour population and labour force both growing at a nearly equal pace, +1.1% and +1.0%, respectively.

Statistics CanadaFootnote 1 reported 298,000 job vacancies across Canada in FY1718, compared to 221,000 in FY1617 (+35.2% increase year over year). The survey also reported 1.21 million unemployed workers in FY1718. Taken together—expressed as the unemployment-to-job vacancies ratio (U/V ratio) —for every job vacancy, 4.1 individuals were unemployed. In comparison, Canada’s U/V ratio stood at 6.1 in the previous year. Overall, this suggests Canada’s labour market tightened considerably in FY1718.

In 2017, Canada’s real gross domestic product (GDP) rose 3.0%, following a 1.1% increase in 2016. Real GDP increased in every province and territory, with Alberta's growth being the strongest among the provinces (+4.4%), rebounding from a 4.2% decline in the previous year. In the territories, real GDP growth ranged from 3.1% in Yukon, 3.7% in Northwest Territories, and 9.8% in Nunavut.

For 2018, Canada’s real GDP is forecasted to grow by approximately 2%, with economic expansion projected in most parts of the country, albeit at a more moderate pace than in 2017.

1.2 Main resultsFootnote 2

Decline in the number of EBSM clients and interventionsFootnote 3

In FY1718, the use of labour market programming declined throughout Canada. Under the Labour Market Development Agreements (LMDAs), provinces and territories served 695,911 clients, dropping by 5.2% compared to the previous year. Similarly, the number of LMDA interventions delivered to clients decreased by 6.5% year over year; to a total of 1,071,881 interventions.

With the addition of programs and services delivered by Indigenous organization through the Aboriginal Skills and Employment Training Strategy (ASETS), a grand total of 715,658 EBSM clients were served (-4.8%), and 1,107,740 EBSM interventions (-6.0%) were delivered in FY1718.

The overall client-to-intervention edged down to 1.55, compared to 1.57 in the previous year, as the number of interventions declined at a higher rate than the client totals.

Overall expenditures edged down by 0.6% to a total of $2.17 billion.

1.3 Client profile and participation

Terminology guide

A client is a person who has participated in programs or services that are funded by the LMDAs or by Indigenous organizations. See section 1.3 for details for client types.

An intervention is a discrete program or service that a client participates in. See Section 1.4 and 1.5 for the type of interventions available to clients.

Any reference to participants in this chapter is equal to the number of interventions, where information on designated groups is only collected at the intervention level.

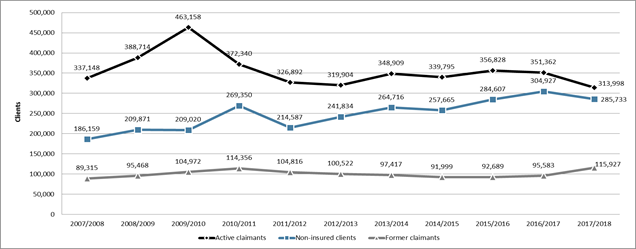

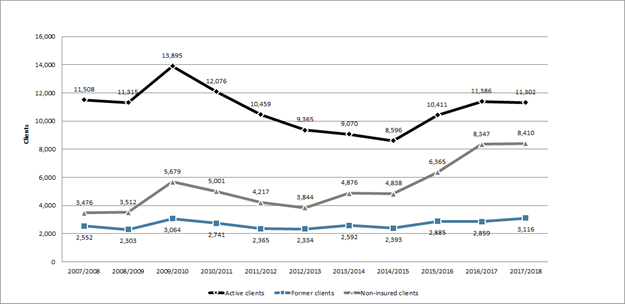

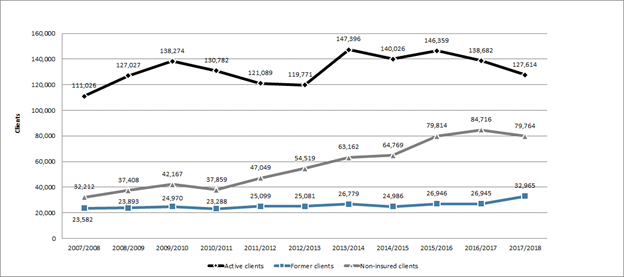

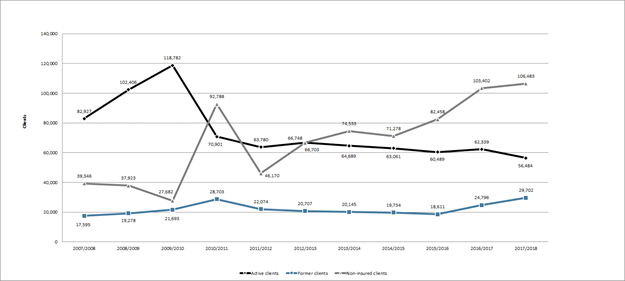

In FY1718, 313,998 active EI claimants were served, decreasing by 10.6% year over year. Non-insured clients also declined by 6.3%. Former EI claimants were the only client type to increase, growing by 21.3% year over year. New provisions introduced in July 2016 expanded the definition of former claimants to those who completed an EI claim in the previous five years, compared to three years under old provisions.Footnote 4 As a result, the sudden growth among former claimants in FY1718 is largely attributable to the legislation changes. The decline in active claimants largely stems from overall declines in the usage of EI programming (see table 1 for details about the three types of clients).

| Client type | Total of client served | Year-over-Year Change (%) | Share of total clients |

|---|---|---|---|

| Active claimants | 313,998 | -10.6% | 43.9% |

| Former claimants | 115,927 | +21.3% | 16.2% |

| Non-insured clients: | 285,733 | -6.3% | 39.9% |

Active claimants are those who had an active EI Part I regular claim when they requested assistance under Part II of the Employment Insurance Act. Typically, they have stronger and more recent job attachment. They tend to be able to return to work more quickly than those with weaker ties to employment. Active claimants who are considered job-ready from an analytical point of view often seek out short-term interventions under EI Part II to find their next employment opportunity. Others require longer-term Employment Benefits to upgrade their skills, establish certification or refine their job search strategies.

Former claimants are those who completed an EI claim in the previous five years, or who began a parental or maternity claim in the last five years when they requested assistance under Part II. They are no longer eligible for EI Part I; however, they remain eligible for EI Part II under certain criteria.Footnote 5 Former claimants do not receive income support under Part I of the Employment Insurance Act while they complete an Employment Benefit intervention; however, they may receive Part II support while completing their return-to-work action plan.

Non-insured clients are unemployed individuals who are neither active nor former EI clients. Non-insured clients usually have little substantive or recent job attachment. They include new labour force participants and individuals who were formerly self-employed without paid employment earnings. While these clients are not eligible for Employment Benefits under EI Part II, they may access Employment Assistance Services.

Compared to FY0708, provinces, territories and Indigenous organizations served more total clients in FY1718 increasing from a total of 612,622 in FY0708, to 715,658, growing by 16.8% over the ten years. Active EI claimants declined from 337,148 in FY0708, to 313,998 in the most recent fiscal year, dropping by 6.9% over the period.

Former EI claimants and non-insured clients both increased over the ten-year period, by +29.8% and 53.5%, respectively. The growth among non-insured clients in the last ten years resulted in their shares among all clients increasing from 30.4% in FY0708 to 39.9% in the recent year.

Chart 1 - Text version

| Active claimants | Non-insured clients | Former claimants | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2006/2007 | 349,865 | 176,879 | 91,458 |

| 2007/2008 | 337,148 | 186,159 | 89,315 |

| 2008/2009 | 388,714 | 209,871 | 95,468 |

| 2009/2010 | 463,158 | 209,020 | 104,972 |

| 2010/2011 | 372,340 | 269,350 | 114,356 |

| 2011/2012 | 326,892 | 214,587 | 104,816 |

| 2012/2013 | 319,904 | 241,834 | 100,522 |

| 2013/2014 | 348,909 | 264,716 | 97,417 |

| 2014/2015 | 339,795 | 257,665 | 91,999 |

| 2015/2016 | 356,828 | 284,607 | 92,689 |

| 2016/2017 | 351,362 | 304,927 | 95,583 |

| 2017/2018 | 313,998 | 285,733 | 115,927 |

Over a number of years, provinces and territories have prioritized serving clients with barriers searching for employment, and individuals further removed from the labour market. This changing shift in focus has resulted in jurisdictions serving more clients who enter LMDA-funded programming as non-insured clients.

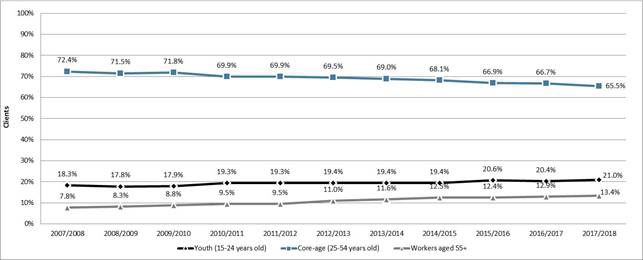

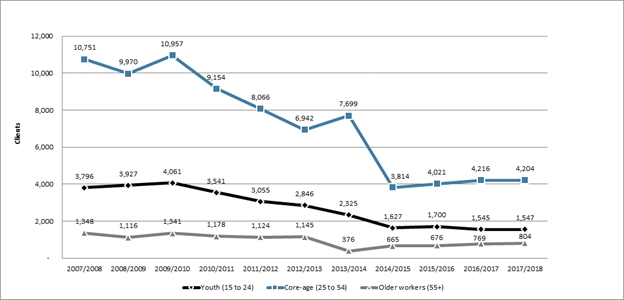

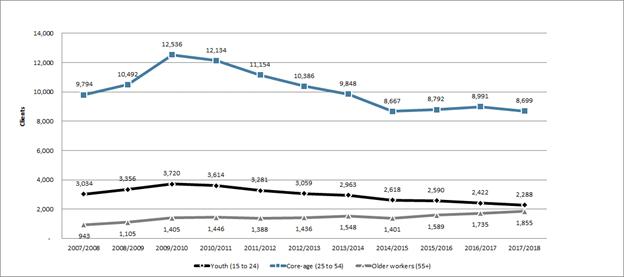

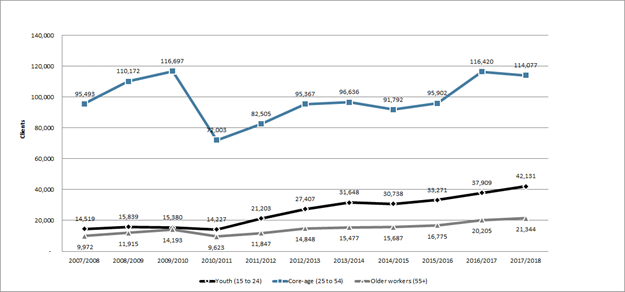

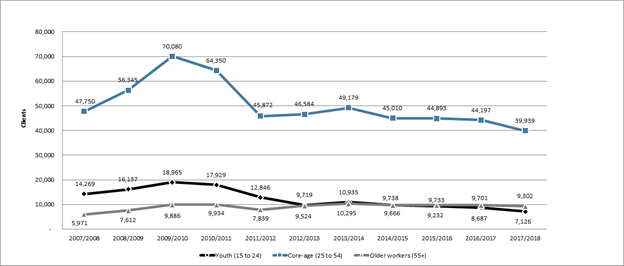

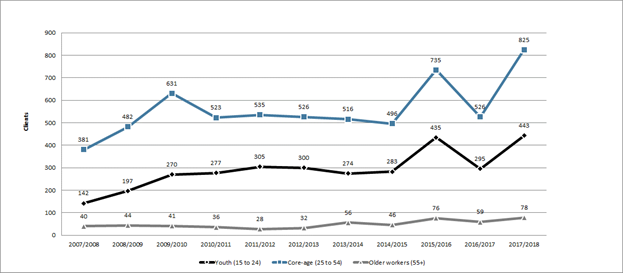

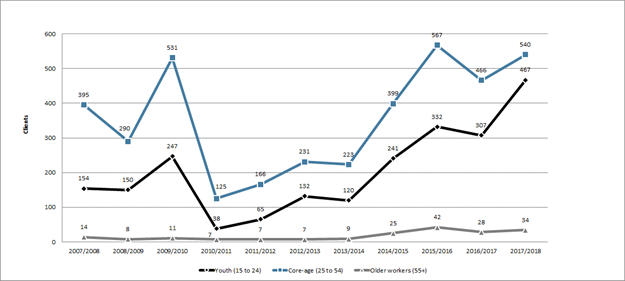

Age distributionFootnote 6

In FY1718, the majority (65.5%) of EBSM clients were in their core working years (25 to 54 years old), totalling 413,524 individuals. Youth – those aged 15-24 years old – represented 21.0% of all clients (132,814), and clients aged 55 or older were the remaining 13.4% of the shares (84,918 clients). Compared to the previous year, all three age groups declined: core-aged workers dropped by 6.1%, youth clients slid by 1.2%, and those aged 55 or older edged down by 0.2%.

| Client age group | Total clients served | Year-over-Year Change (%) | Share of total clients |

|---|---|---|---|

| Youth (15 to 24 years old) | 132,814 | -1.2% | 21.0% |

| Core-age (25 to 54 years old) | 413,524 | -6.1% | 65.5% |

| Workers aged 55+ | 84,918 | -0.2% | 13.4% |

Characteristics of youth EBSM clients and youth in the labour market in FY1718:

- Majority of youth are non-insured participants

- Represented 24% of Employment Benefit participants and 20% of EAS participants

- 14% of labour force

- 11.1% unemployment rate

- 63.8% participation rate

Characteristics of core-aged EBSM clients and cored-aged in the labour market in FY1718:

- Close to 80% were either EI active claimants or non-insured

- Represented roughly 2/3 among both Employment Benefit and EAS participants

- 65% of labour force

- 5.2% unemployment rate

- 86.9% participation rate

Characteristics of EBSM clients aged 55+ and workers aged 55 and older in the labour market in FY1718:

- Half of participants are EI active claimants

- Represented about 9% of Employment Benefit participants and 14% of EAS participants

- 21% of labour force

- 5.5% unemployment rate

- 38.0% participation rate

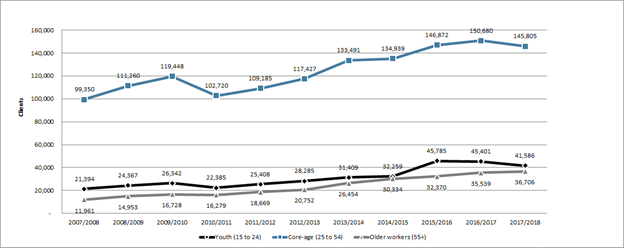

Chart 2 - Text version

| Youth (15-24 years old) | Core-age (25-54 years old) | Workers aged 55+ | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2007/2008 | 18% | 72% | 8% |

| 2008/2009 | 18% | 72% | 8% |

| 2009/2010 | 18% | 72% | 9% |

| 2010/2011 | 19% | 70% | 9% |

| 2011/2012 | 19% | 70% | 9% |

| 2012/2013 | 19% | 70% | 11% |

| 2013/2014 | 19% | 69% | 12% |

| 2014/2015 | 19% | 68% | 12% |

| 2015/2016 | 21% | 67% | 12% |

| 2016/2017 | 20% | 67% | 13% |

| 2017/2018 | 21% | 66% | 13% |

In the context of an aging labour force, participation in labour market programming for clients aged 55 or older increased by 111.4% since FY0708, and their proportion among all clients has jumped from 7.8% in FY0708, to 13.4% in FY1718. This age cohort has more representation in the workforce than other cohorts, making up roughly 21.1% of the labour force.

Compared to FY0708, youth participation in labour market programming also increased (+41.2%). This age cohort now represents 21.0% of all clients, compared to 18.3% ten years ago. Youth make up about 14% of the labour force, meaning young Canadians are over-represented in labour market programming relative to their representation in the labour market. In recent years, provinces and territories prioritized serving youth, as a means of addressing an aging workforce, and developing and maintaining a competitive workforce.

Given the growth of both youth and clients aged 55 or older, the share of core-age workers (25-54 years old) declined over the last ten years. Core-age workers now represent 65.5% of all clients, compared to 72.4% in FY0708. The representation of this age group in labour market programming is proportional to their current shares in the labour force, which stood at 64.8% in FY1718.

Designated groupsFootnote 7

In support of employment equity principles, ESDC collects information on the EBSM participation of women, Indigenous peoples, members of visible minority groups and persons with disabilities. As participantsFootnote 8 voluntarily self-identify, as such, annual fluctuations may be due to changes in self-identification.

- Women participated in a total of 481,969 EBSM interventions in FY1718, a 2.4% decrease year-over-year (44.4% of all interventions delivered to Canadians). Women represented 44.2% of unemployed workers in FY1718. Women accessed EAS-only interventions (91.3%) at a higher rate than men (82.1%). Among participants who were women, 47.8% were non-insured clients, compared to 37.6% for men.

- In FY1718, a total of 140,688 participants self-identified as persons with disabilities, an increase of 1.2% year-over-year. Over ten years, the proportion of participants with disabilities has increased by over 150%. Among several factors, this can be attributed to workers aging into disability.Footnote 9 Persons with disabilities participated in 13.0% of all interventions delivered in FY1718. The vast majority (93.8%) participated in an EAS-only intervention, compared to 6.2% who participated in Employment Benefits. Just over half were non-insured clients (50.6%), followed by 27.2% who were active claimants, and 22.2% who were former claimants.

- Indigenous peoples participated in 87,519 interventions in FY1718, a slight increase of 0.9% year-over-year. As a share of all ESBM interventions delivered in Canada, Indigenous people participated in 7.9% of the total, including programming delivered through ASETS. As in previous years, most Indigenous participants relied on EAS-only interventions (94.7% of all interventions). However, Employment Benefits grew by almost 28%, and represented 5.3% of total interventions delivered to Indigenous participants.

- Members of visible minority groups participated in 77,719 interventions in FY1718, increasing by 10.0% year-over-year. As a proportion of all interventions delivered in Canada, members of visible minority groups represented 7.2% of all participants. The majority of interventions (95.4%) were EAS-only, compared to 4.6% for Employment Benefits.

Official languages

ESDC furthers the commitment of the Government of Canada to foster the full recognition and use of both English and French in Canadian society, by ensuring that labour market programs and services are delivered in both official languages. In this context, all LMDAs contain commitments by provinces and territories to have programs and services delivered in both official languages where there is significant demand.

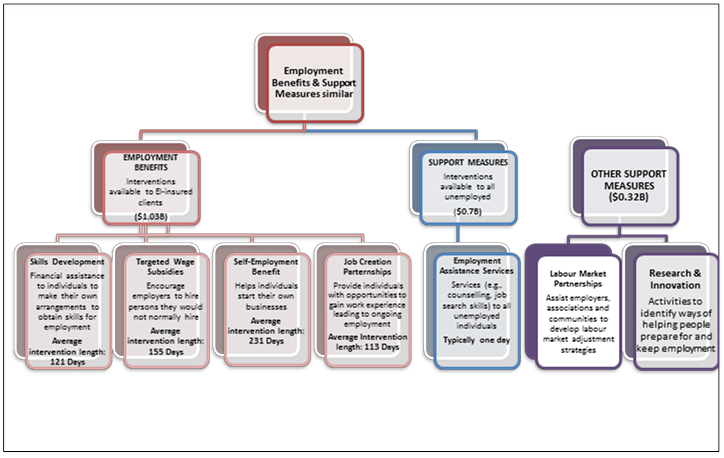

1.4 Interventions: Employment benefits

Employment Benefits consists of longer-term interventions focused on providing skills or work experience required to regain employment. Under the LMDAs, provinces and territories provide employment benefits similar to the following six benefits types outlined in the EI Act: Skills Development-Regular (SD-R); Skills Development-Apprentices (SD-A); Targeted Wage Subsidies (TWS); Self-Employment (SE); Job Creation Partnerships (JCPs); and Targeted Earnings Supplements (TES)Footnote 10.

In FY1718, Employment Benefits interventions totalled 141,722, decreasing by 3.6% compared to the previous reporting period. This can be attributed to the declining number of active claimants, usually the main beneficiaries of these types of interventions. The average length of an Employment Benefit intervention increased from 117 days in FY1617, to 125 days in FY1718. The increased duration of Employment Benefits suggests clients participating in labour market programming were served with more intensive supports.

SD-R interventions edged up by +5.2% to a total of 55,360, while SD-A interventions dropped by 9.3%, to a total of 62,277 in FY1718. Combined, Skills Development interventions made up 83.3% of all Employment Benefits, and Skills Development expenditures totalled $829.6 million, lower than the $855.3 million spent in FY1718.

In FY1718, TWS interventions dropped by 6.9% year-over-year, to 15,266, and represented 10.8% of all Employment Benefits. Expenditures on TWS programming totalled $109. 9 million, a decline of $11.1 million in spending compared to the previous fiscal year.

The number of SE interventions delivered decreased by 6.3%, to 5,749, with their shares among all Employment Benefits reaching 4.1%. However, SE expenditures increased in FY1718; going from $59.8 million in FY1617, to $61.6 million in the current reporting year.

Overall, JCP interventions declined to 3,070, sliding by 5.6% year over year. JCP expenditures dropped to $33.7 million, compared to $34.8 million in the previous year.

Text version

- Employment Benefits & Support Measures similar

- EMPLOYMENT BENEFITS: Interventions available to EI-insured clients ($1.03B)

- Skills Development: Financial assistance to individuals to make their own arrangements to obtain skills for employment. Average intervention length: 121 Days

- Targeted Wage Subsidies: Encourage employers to hire persons they would not normally hire. Average intervention length: 155 Days

- Self-Employment Benefit: Helps individuals start their own businesses. Average intervention length: 231 Days

- Job Creation Partnerships: Provide individuals with opportunities to gain work experience leading to ongoing employment. Average Intervention length: 113 Days

- EMPLOYMENT BENEFITS: Interventions available to EI-insured clients ($1.03B)

- SUPPORT MEASURES: Interventions available to all unemployed ($0.7B)

- Employment Assistance Services: Services (e.g., counselling, job search skills) to all unemployed individuals. Typically one day

- Other Support Measures ($0.32B)

- Labour Market Partnerships :Assist employers, associations and communities to develop labour market adjustment strategies

- Research & Innovation: Activities to identify ways of helping people prepare for and keep employment

| Employment benefits | Interventions | Share of Employment Benefits | Year-over-Year Change | Expenditures ($000s) | Estimated Cost Per Intervention |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Targeted Wage Subsidies | 15,266 | 10.8% | -6.9% | $109.9 | $7,195 |

| Self-Employment | 5,749 | 4.1% | -6.3% | $61.6 | $10,713 |

| Job Creation Partnerships | 3,070 | 2.2% | -5.6% | $33.7 | $10,973 |

| Skills Development-Regular | 55,360 | 39.3% | +5.2% | $829.6 | $7,052 |

| Skills Development-Apprentice | 62,227 | 44.0% | -9.3% | ||

| Canada | 141,722 | 100% | -3.6% | $1,034.7 | $7,301 |

1.5 Interventions: Support measures

Part II of the Employment Insurance Act authorizes three support measures: Employment Assistance Services (EAS), Labour Market Partnerships (LMPs) and Research and Innovation (R&I). Through LMDAs, provinces and territories deliver these measures at regional and local levels, while ESDC retains responsibility for pan-Canadian delivery of LMPs and R&I (see section 4: Pan-Canadian Activities and the National Employment Services). In FY1718, Support Measures were available to all unemployed individuals in Canada, including non-insured clients. However, LMPs and R&I are generally not associated with direct client services and, therefore, counts on participants or interventions are not available. Delivered by the provinces and territories, the EAS component of Support Measures provides a full range of self-help and assisted services, such as support in determining career objectives through employment counselling, improving job search techniques, completing a return-to-work action plan, and accessing labour market information in support of career choices.

1.5.1 Employment Assistance Services

Provinces and territories design and deliver interventions similar to Employment Assistance Services (EAS), which in FY1718, were available to all unemployed people in Canada. In addition to helping EI-insured clients, EAS interventions provide crucial support to those who have been absent from the labour market for an extensive period or who have low job attachment. They may also support new immigrants or young people who are entering the Canadian labour market for the first time. These interventions are reported in one of the three following categories: Employment Services, Group Services, and Individual Counselling.

In FY1718, a total of 930,159 EAS interventions were delivered, decreasing by 7.0% year-over-year. Total expenditures on EAS dropped by 3.7%, to a total of $694.1 million, a decline of $26.1 million compared to the previous year.

Interventions similar to Employment Services continued to be the most common EAS intervention type, accounting for 57.7% of all EAS interventions in FY1718. A total of 537,032 Employment Services interventions were delivered, a decrease of 10.7% year-over-year. Group Services dropped by 28.2%, for a total of 21,764 interventions delivered. In turn, the share of Group Services among all EAS-type interventions dropped to 2.3%, compared to 2.5% in the previous year. Individual Counselling is particularly important when supporting clients who face barriers to employment, and often need action plans as a pathway to Employment Benefits. A total of 371,363 interventions were delivered in FY1718, dropping by 0.5% year-over-year.

1.5.2 Other support measures

The Labour Market Partnership (LMP) initiative facilitates collaboration between employers, employees and employer associations, as well as, community groups and communities to develop solutions to labour force imbalances, such as persistent high unemployment or skill shortages. In FY1718, LMP expenditures totalled $171.9 million, increasing by 7.2% year-over-year.

Research and Innovation (R&I) initiatives identify better ways of helping people prepare for, return to or maintain employment and participate productively in the labour force. In FY1718, R&I expenditures increased to $148.4 million, which is 27.4% higher than in the previous year.

| Interventions | Share of Employment Support Measures | Year-over-year Change | Expenditures ($000s) | Estimated cost per intervention | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Employment Assistance Services* | |||||

| Employment Services | 537,032 | 57.7% | -10.7% | $694.1 | $746 |

| Group Services | 21,764 | 2.3% | -13.9% | ||

| Individual Counselling | 371,363 | 39.9% | -0.5% | ||

| Total Employment Assistance Services | 930,159 | 100% | -7.0% | $694.1 | |

| Other Support Measures | |||||

| Labour Market Partnerships | n/a | n/a | n/a | $171.9 | n/a |

| Research & Innovation | n/a | n/a | n/a | $148.4 | n/a |

| Canada | 930,159 | 100% | -7.0% | $1,014.4 | n/a |

- *Expenditures for Employment Assistance Services are only reported at the aggregate level by most provinces and territories.

1.6 Expenditures

Total expenditures under Part II of the Employment Insurance Act were $2.17 billion in FY1718, which included EBSM programming, LMPs and R&I, as well as the pan-Canadian activities. This represented a slight decrease of 0.6% compared to the previous year.

Under the LMDAs, Employment Benefits remained the largest investment, at $1,034.7 billion, representing half of total expenditures by provinces and territories. Compared to FY1718, spending on Employment Benefits declined by over $35 million (-3.3%). Employment Assistance Services expenditures decreased as well, sliding by 3.7%, or $26.3 million, to a total $694.1 million. This decline in spending is largely attributable to decreasing interventions due to an improving economy, and fewer clients served by provinces and territories.

Expenditures towards LMPs and R&I measures increased, going from $277 million in FY1617, to $320.43 million in FY1718 (+15.7%).

Pan-Canadian expenditures edged up by 5.4%, increasing from $114.1 million in FY1617 to $120.2 million to FY1718. See Section 4 of this chapter for details on Pan-Canadian activities.

FY1718 Employment Benefits and Support Measures Key Facts

| EI Active & Former Clients (LMDA) | Non-Insured Clients (LMDA) | Pan-Canadian1 |

|---|---|---|

| 429,925 | 285,733 | 19,747 |

| Active Claimants | Former Claimants | Non-Insured |

|---|---|---|

| 43.9% | 16.2% | 39.9% |

| Youth clients (15–24)2 | Core Age clients (25–54)2 | Clients aged 55 or older2 |

| 21% | 65.5% | 13.4% |

| FY1718 | Year-over-Year Change | |

|---|---|---|

| Employment Benefits | 141,722 | 3.6% |

| Support Measures: EAS | 930,159 | 7.0%  |

| Pan-Canadian | 35,859 | 13.0% |

| FY1718 | Year-over-Year Change (p.p.) | |

|---|---|---|

| Employment Benefits | 13.2% | 0.4 |

| Support Measures: EAS | 86.8% | 0.4 |

| FY1718 ($ Million) | Year-over-Year Change | |

|---|---|---|

| Employment Benefits | $1,034.7 | 3.3% |

| Support Measures: EAS | $694.1 | 3.7% |

| LMPs and R&I | $320.3 | 15.7% |

| Pan-Canadian | $120.2 | 5.4% |

| Total Expenditures | $2,169 | 0.6% |

| Indicator | Total | Year-over-Year Change |

|---|---|---|

| Active Claimants Served | 313,998 | 10.6% |

| Returns to Employment | 177,335 | 5.3% |

| Estimated Unpaid Benefits ($ Million) | $1,103.2 | 18.0% |

- 1 EI Part II Pan-Canadian services to individuals are through the Aboriginal Skills and Employment Training Strategy.

- 2 Age distribution does not equal 100%, as the “unknown” category is not reported here. Date of birth is not collected for clients in SD-Apprentices and Group Services.

- 3. Totals may not add up exactly due to rounding; accounting adjustments are not included.

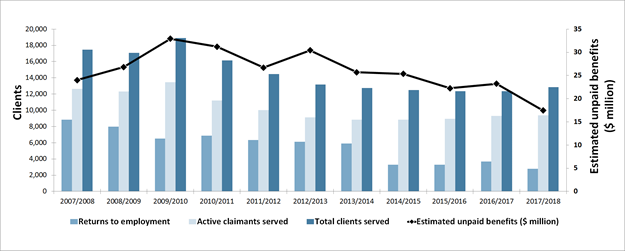

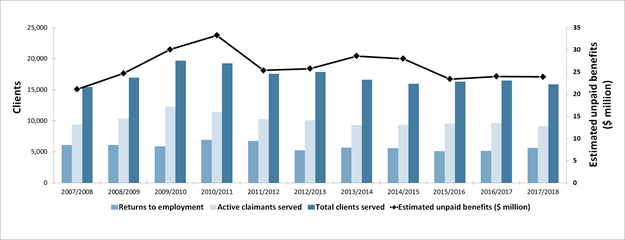

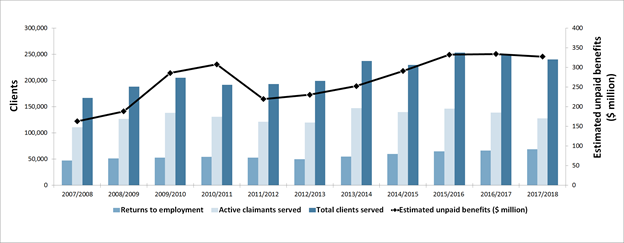

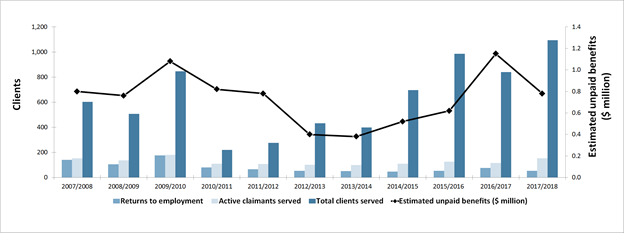

1.7 Key Performance IndicatorsFootnote 11

ESDC monitors the results of EBSM-similar programming delivered by provinces and territories through three key performance indicators:

- the number of active EI claimants served;Footnote 12

- the number of EI clients who return to employment following an intervention;Footnote 13 and

- the amount of unpaid EI Part I benefits resulting from the returns to employment.

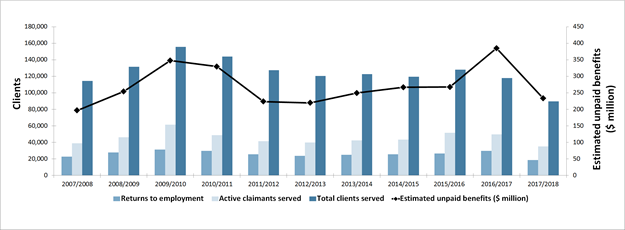

In the context of improving labour market and economic conditions in FY1718 throughout most parts of Canada, the number of active EI claimants served (313,998) dropped by 10.6% year-over-year. Returns to work edged down by 5.3% year-over-year, with a total of 177,335 clients finding employment within six months of completing their interventions. Stemming from the declines in active EI claimants and lower returns to work, unpaid EI Part I benefits totalled $1.103 billion, dropping by 18.0% compared to the previous year.

Table 5 presents supplementary performance indicators at the national and provincial/territorial level, contextualized with labour market aggregates. Since multiple factors can influence results at the individual, jurisdictional and national level, these indicators cannot be unequivocally attributed to LMDAs.

At the national level, 59.5% of active EI claimants began their first LMDA-funded intervention within 12 weeks after their Benefit Commencement Period (BPC). Compared to FY1617, this is an increase of 2.8 percentage points, where 56.7% of active claimants began within 12 weeks that year. At the provincial/territorial level, most jurisdictions registered an increase, as well, and results ranged from 74.8% in Quebec, to 20.2% in Newfoundland and Labrador.

In FY1718, Canada’s returns to work from interventions among active clients, expressed as a proportion of Canada’s labour force, was 0.9%. Five provinces and territories exceeded the national average. Secondly, unpaid EI regular benefits stemming from returns to work, expressed as a proportion of total EI regular benefits paid, was 8.7% at the national level. Quebec, Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta, and British Columbia posted higher proportions than the national figure.

Only Quebec registered above the national average for the last two ratios. This suggests an effective and efficient balance between returning clients to work as soon as possible, while ensuring the necessary active employment services for employment success over a mid- to long-term horizon.

| Unemployment Rate (FY1718) | Job Vacancy Rate (FY1718) | EI Active Claimants (%) Beginning EI Part II within 12 Weeks Following their Part I Benefit Period Commencement* (FY1718) | Returns to Work Among Active EI Clients from EBSM Interventions, as a Proportion of the Labour Force (FY1718) | Estimated Unpaid EI Regular Benefits Resulting EBSM Interventions, as a Proportion of Part I Regular Benefits Paid (FY1718) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Newfoundland & Labrador | 14.7% | 1.7 | 20.2% | 1.1% | 1.8% |

| Prince Edward Island | 8.2% | 2.7 | 60.1% | 2.7% | 4.1% |

| Nova Scotia | 8.3% | 2.5 | 36.1% | 1.1% | 3.7% |

| New Brunswick | 8.0% | 2.6 | 55.3% | 2.3% | 4.0% |

| Quebec | 5.9% | 2.5 | 74.8% | 1.5% | 10.8% |

| Ontario | 5.8% | 3.0 | 44.3% | 0.5% | 7.3% |

| Manitoba | 5.5% | 2.4 | 49.3% | 0.7% | 10.7% |

| Saskatchewan | 6.1% | 2.2 | 35.0% | 0.8% | 10.6% |

| Alberta | 7.4% | 2.6 | 38.4% | 0.8% | 12.9% |

| British Columbia | 5.0% | 4.1 | 41.7% | 0.8% | 11.4% |

| Northwest Territories | 6.9% | 2.8 | 34.4% | 0.6% | 6.3% |

| Yukon | 5.4% | 4.0 | 41.1% | 0.6% | 5.3% |

| Nunavut | 14.5% | 3.1 | 27.0% | 0.3% | 5.0% |

| Canada | 6.1% | 2.9 | 59.5% | 0.9% | 8.7% |

- Source: Labour Force Survey, Business Payroll Survey, and EI Administrative Data.

- *This includes a small percentage of clients who began EI Part II programming up to 2 weeks prior to their Part I Benefit Period Commencement. SD-A participants and those who were non-insured participants were excluded, if they had taken EAS in the previous year.

1.8 Online resources about LMDAs programs and services

Increasingly the internet is an important resource when seeking employment, or to learn about skills development and training supports that are available to Canadians.

In FY1718, the federal government reached out to provinces and territories to gain a better understanding of the tools and materials about the labour market programming on their respective websites. In many cases, these resources serve as the central point of access to information regarding employment and training initiatives, and most are funded by the provinces and territories. (See Annex 3.16 for a full list of websites.)

For more information about LMDA-funded programs and services in your province or territory, visit the following:

- Newfoundland and Labrador’s Department of Advanced Education, Skills and Labour

- Prince Edward Island’s Skills PEI Division

- Nova Scotia’s Labour and Advanced Education

- New Brunswick’s Post-Secondary Education, Training and Labour

- Quebec’s Ministry of Education and Social Solidarity

- Ontario’s Ministry of Training, Colleges and Universities

- Manitoba’s Entrepreneurship, Training and Trade

- Saskatchewan’s Ministry of the Economy

- Alberta’s Ministry of Human Services

- British Columbia’s Ministry of Social Development

- Northwest Territories’ Department of Education, Culture and Employment

- Yukon’s Department of Education

- Nunavut’s Department of Education

Newfoundland and Labrador

Newfoundland and Labrador delivers a range of employment and training programs and services through the province’s website. These online tools assist individuals to find employment, help employers to access the workers they need, and ensure that communities and regions throughout Newfoundland and Labrador are well equipped to respond to labour market opportunities and challenges. There are a number of online employment related workshops available to assist individuals in their career and employment planning process. As well, there are online workshops available to assist employers with a host of human resource related needs. Clients can also access computers and online resources through any of the community-based resource Employment Centres located across Newfoundland and Labrador. The province also uses the Labour Market Programs Support System (LaMPSS), an online application system for employers and community partners to apply for programs. This online resource provides information about program guidelines and offers a user guide for the application.

Prince Edward Island

Prince Edward Island’s SkillsPEI website and the provincially funded WorkPEI site connect job seekers with employers. These sites, in conjunction with JobBank, provide valuable information to job seekers about programs and services to assist them transition to employment as well as provide employers with information to assist them meet their workforce needs. Through the EAS program, service providers offer a variety of tools to support clients as they navigate the career assessment process and move along the path to sustainable employment. The Department of Workforce and Advanced Learning (WAL) launched a new provincially funded website in 2016, called WorkPEI.ca. WorkPEI provides job seekers and employers with a variety of job search tools including a job board, information on labour related programs and services available on PEI and labour market information. WorkPEI also enables employers to search the online resumes of registered job seekers. Using their own private dashboard, employers can manage job applications and contact applicants directly for any published vacancies or future opportunities. WorkPEI helps match labour supply with local labour demand through the centralized location of job vacancies in PEI, while also providing job seekers with greater access to the hidden job market.

Nova Scotia

Similarly, in Nova Scotia LMDA program information is posted to the Labour and Advanced Education website, which offers details on each program’s objective, eligibility criteria and program guidelines. Programs directed to employers also provide information and the means to apply on-line. Each EAS service provider also makes links to the LAE website on their own organisation’s web pages. Nova Scotia will also be launching a Virtual Careers portal. In FY1718, the province has developed the Request for Proposals for a vendor to design, create, and manage Nova Scotia’s virtual employment services presence on the Internet.

New Brunswick

In New Brunswick, the province’s NBjobs.ca site offers clients links to job postings, job search guides, labour market information, and resources for employers. The province is developing an online job fair platform, as a cost-effective way to connect employers with prospective candidates, and to communicate many provincial workforce strategies with the public. The site also promotes Employment and Continuous Learning Services, and a viable way to collect local LMI from employers and job seekers to feed into a regional/provincial database.

Quebec

Under the LMDA, Quebec has the exclusive responsibilities of government services for placement and labour market information in the province. These services, which are an integral part of the continuum of services, are intended for the public and for businesses. They are provided in different ways but are most often used online.

L’IMT en ligne provides relevant information to career exploration and choices as well as job reintegration. This site, which receives about three million visits annually, disseminates information on occupations, training programs, industries, and companies to help users make employment-related decisions.

Placement en ligne enables job seekers to post their applications and companies to advertise their vacant positions (regular jobs, student jobs, and internships). Due to the breadth of information made available to the public (over 900,000 vacant positions per year from more than 40,000 companies) and the matching mechanisms associated with it, Placement en ligne’s website receives several million visits every year.

Ontario

The redesigned Employment Ontario website gives job seekers information on training, skills building, or assistance finding a job. Through the website, users are also able to request an appointment with a counsellor to help them develop career goals, prepare for interviews, or get ready for a new job. The website’s new live chat option supports users with job search advice, and offers details on training and hiring supports. An important part of the website redesign included the addition of real-time labour market information, acquired through the collection and analysis of job posting data. These data provide Ontarians with more timely, local, and specific information compared to traditional sources of labour market information. In addition to Ontario’s own online resources, the Career Ready Fund and Skills Catalyst Fund (funded as Research and Innovation) support a range of organizations to offer digital tools that help jobseekers, students, as well as, recent graduates connect and collaborate with employers to develop their skills.

Manitoba

Manitoba’s website provides information on a wide range of provincial labour market programming including LMDA, WDA and provincially funded services including directory of where to obtain these services. The website provides Manitobans with links to Apprenticeship Manitoba, Job Bank website, youth services, Adult Literacy Programs, Adult Learning Centres, Manitoba Student Aid, Post Secondary Education and career development resources.

Saskatchewan

Saskatchewan’s website provides links and information on labour market development programs, tools, and services to assist clients return to work. In addition, community-based organizations and training institutions also provide information about programs and services they deliver. These organizations may also use social networking sites to promote their programs and services. For employers, SaskJobs is an effective tool to find potential workers.

Alberta

ALIS is Alberta’s gateway to career, learning, employment and workplace information and resources, helps Albertans make informed decisions necessary to succeed in the labour market. ALIS provides support to a broad audience including junior high, senior high and post-secondary students, newcomers and influencers such as parents, educators, counsellors and career practitioners. ALIS is used by front-line delivery staff, educators and parents to support students in career planning, as well as by third-party agencies supporting Albertans with barriers to the labour market. ALIS provides Albertans with tools to help them through the career planning process and information related to résumé and cover letter writing, preparing for an interview, who to provide as references, and how to find work opportunities. ALIS also includes a series of work books to help individuals with low-literacy enter the workforce. The series cover topics such as making job choices, deciding on a job, finding a job, keeping a job, and training for work. ALIS is partially supported with LMDA funding: these funds support the development of some of contents and tools, and provides ongoing maintenance for some of the resources. The contents and articles on ALIS are updated regularly.

British Columbia

British Columbia provides extensive online resources to help potential clients learn about programs and services, research career paths, and learn about local labour market conditions. In addition to detailed information about WorkBC employment services, online resources for potential clients include BC’s Career Guide for Indigenous People 2018; Blueprint Builder ‐ an online career planning tool; and WorkBC's Career Trek videos. In addition to tools for potential clients, WorkBC’s Online Employment Services (OES) system provides clients with 24/7 access to ministry information and services via an online channel. Among the many online functionalities, clients and service providers can access an online application portal for Apprenticeship programs and services; an Intake Management application for service providers to manage applications; and a Targeted Referral and Feedback (TRF) functionality for service providers to receive prospective clients from Service Canada. Additionally, providers can complete and submit Community Employment Partnerships (CEP).

WorkBC also provides multiple online resources to connect employers with potential workers. This site contains the most comprehensive database of B.C. job postings, an interactive map of WorkBC Employment Services Centres across the province, and features a live chat for instant help with using the website and finding information. The Government of BC Service Design team within the Government Digital Experience Division is changing how citizens access government services by bringing innovation and a human‐centred approach. The role of service design is to put human experience and need in the forefront of the design thinking process. Empathizing, asking questions and testing ideas can help create better innovations and services relevant to the people who use them. The WorkBC Online Employment Service Portal will continue to leverage this Service Design approach and client experience analytics to continually improve the citizen experience.

Northwest Territories

In Northwest Territories, the territory’s website offers information about the suite of labour market programming, labour market information, and information about in-demand occupations, as well as, links various job boards, including Job Bank. Moving forward, the territory intends to develop an Interactive Labour Market Information Portal that targets youth and students, providing relevant, accurate, and timely labour market information to make informed and evidence-based educational, career and business decisions.

Yukon Territories

Yukon’s online resources for employment benefits and support measures are delivered through the territory’s website. Skills Development, Apprenticeship, EAS, and Labour Market Partnerships are currently centrally located through Yukon Government's website.

2. Provincial and territorial EBSM activities

This section analyzes the provincial and territorial economic environment and EBSM-similar activities in FY1718; linking trends in clients served, interventions, and expenditures to local labour market conditions, and employment programming priorities.

2.1 Context

Under the LMDAs, provinces and territories received funding to support the delivery of programs and services, similar to the EBSMs established under Part II of the Employment Insurance Act.Footnote 14 To address unique labour market challenges, provinces and territories delivered employment programming under LMDAs, which were individually negotiated with the Government of Canada. Provinces and territories designed and delivered all EI-funded active employment programming, except for pan-Canadian activities, discussed in Section 4 of this chapter.

Broad-based consultations were held in FY1617 with provinces, territories and stakeholders to identify ways to improve labour market transfer agreements and guide future investments to strengthen labour market programming. Comments received indicated a desire for agreements to be more flexible and responsive to the needs of employers and Canadians, especially those who are underrepresented in the workforce.

Budget 2017 announced new measures to rationalize and expand the existing bilateral labour market transfer agreements with provinces and territories, including the LMDAs. This included amending the EI Act to expand eligibility for Employment Benefits to also include unemployed individuals who have made minimum Employment Insurance premium contributions in at least five of the last ten years. Eligibility for Employment Assistance Services was broadened to include both the unemployed and employed. Provinces and territories were also provided with increased flexibility to support employer-sponsored training under the Labour Market Partnerships Support Measure. These changes took effect on April 1, 2018 and were reflected in amending agreements signed with provinces and territories. These amendments can be found through the LMDA’s website.

In addition, the amended LMDAs require provinces and territories to consult with employer and employee organizations and stakeholders representing Official Language minority communities as part of their annual planning process, as well as to provide ESDC with lists of stakeholders consulted, key priorities coming out of the consultations and linkages with labour market programming priorities.

Budget 2017 also announced an additional $1.8 billion investment in the LMDAs over six years (2017-2018 to 2022-2023), to help more Canadians access EI-funded skills training and employment supports.

Overall, Canada’s economy and labour market performed well in FY1718, resulting in a decline in the number of clients served and LMDA-funded interventions delivered in most provinces and territories. The economy grew in all provinces and territories, and employment levels increased in all but two provinces. Despite varying economic and labour market outcomes, all jurisdictions prioritized improving the labour market attachment of underrepresented groups, such as persons with disabilities, Indigenous persons, recent immigrants, youth, and older workers; as well as ensuring that employers can readily access a skilled workforce. An aging workforce and out-migration remains a particular labour market challenge for Atlantic region, where the provinces worked with communities and regional stakeholders to ensure labour market programming responds to the demographic pressures.

The Managing for Results section for each provincial and territorial summary highlights innovative approaches to improve outcomes for clients. These include:

- Employer engagement in program priorities and design,

- Strategies to deliver active employment supports earlier for EI claimants and,

- Approaches in the use of the Research and Innovation support measure in some jurisdictions.

2.2 Newfoundland and LabradorFootnote 15

In 2017, Newfoundland and Labrador’s real GDP rose by 0.9%, the lowest growth rate among all provinces and territories. The province’s economic growth is forecasted to further soften in 2018, as construction on large scale projects such as the Hebron oilfield and Muskrat Falls dam continue to wind down.

Newfoundland and Labrador: EBSM Key Facts

| EI Clients | Non-Insured Clients |

|---|---|

11,760 |

1,107 |

| Interventions Type | 2017/2018 | Year-over-Year Change |

|---|---|---|

| Employment Benefits | 8,037 | 5.6% |

| Support Measures: EAS | 18,627 | 3.9% |

| Interventions Type | 2017/2018 | Year-over-Year Change(pp) |

|---|---|---|

| Employment Benefits | 30.1% | 2.1 |

| Support Measures: EAS | 69.9% | 2.1 |

| Total Expenditures | 2017/2018 ($ million) | Year-over-Year Change |

|---|---|---|

| Employment Benefits | $112.3 | 4.0% |

| Support Measures: EAS | $6.8 | 9.3% |

| LMPs and R&I | $9.7 | 201.6% |

| Total Expenditures1 | $128.9 | 1.9% |

| 2016/2017 | 2017/2018 | Year-over-Year Change |

|---|---|---|

| $23.23 | $17.47 | 24.8% |

- 1 Totals may not add up due to rounding; does not include accounting adjustments.

Labour market conditions in Newfoundland and Labrador continued to deteriorate in FY1718. Employment declined by 3.4% to 223,600, representing a setback for a fifth consecutive year. Employment in the goods-producing sector decreased from 49,600 to 47,200 (-4.9%), with significant losses in forestry, fishing, mining, oil and gas (-2,000, -14.3%) and in construction (-1,000; -4.6%), only partially offset by gains in agriculture (+400; +26.7%) and utilities (+100; +5.2%). Following the same trend, employment in the services-producing sector weakened (-5,400; -2.9%), with the largest losses recorded in information, culture and recreation (-1,100; -14.9%); finance, insurance, real estate, rental and leasing (-1,000; -13.9%); professional, scientific and technical services (-1,100; -10.1%); trade (-2,800; -6.6%); and other services (-700; -5.5%).

Changes in the economy, technology and an aging population are the main driving forces shaping labour market conditions in Newfoundland and Labrador. To create a provincial climate conducive to economic growth and job creation, in partnership with communities and various local and regional stakeholders, the province identified the following key investment priorities in FY1718:

- strengthening access to flexible, responsive and innovative labour market programming;

- developing a responsive and adaptive workforce, through effective employment and skills training programming, with a focus on underrepresented groups; and,

- commencing the development of a comprehensive human resources plan to support sector diversification and the development of a productive and knowledge-intensive economy.

2.2.1 Managing for results

The Government of Newfoundland and Labrador, through the Cabinet Committee on Jobs, has initiated a number of activities in recent years to support sector growth and diversification. These include:

- bringing a wide range of stakeholders (industry, education and training providers, as well as government) together to discuss sector challenges and determine actions to address these challenges (to date, with agriculture, aquaculture, technology, forestry, community and mining sector);

- sector-specific research activities related to human resources (e.g., occupation-related research in aquaculture, agriculture, and oil and gas);

- greater career exploration programming within the primary and secondary educational system to more closely align with future industry demands;

- initiatives related to immigration, education and literacy, to increase and strengthen the province’s labour supply for future sector requirements; and,

- actions to build upon the quality, availability and benefits of labour market information.

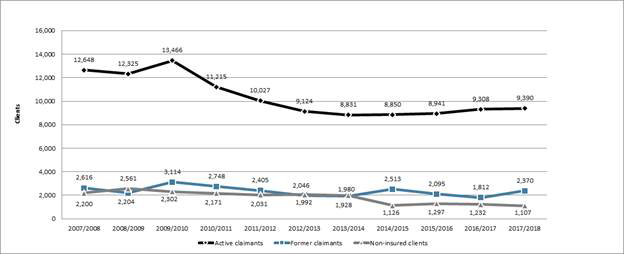

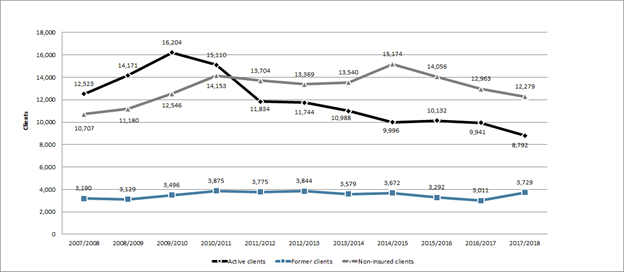

2.2.2 Clients, interventions and expenditures

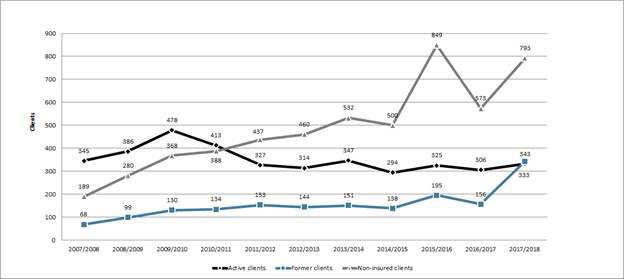

Compared to the previous fiscal year, the total number of clients served in Newfoundland and Labrador during FY1718 increased from 12,352 to 12,867, a growth of 4.2% year-over-year. While the number of active claimants (+82; +0.9%) and former claimants (+558; +30.8%) expanded, non-insured clients (-125; -10.1%) weakened.

With respect to their shares of the total number of clients served, active claimants (73.0%) and non-insured clients (8.6%) fell by 2.4 and 1.4 percentage points respectively, whereas former claimants (18.4%) climbed by 3.7 percentage points.

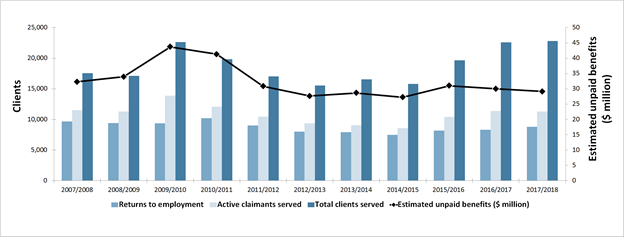

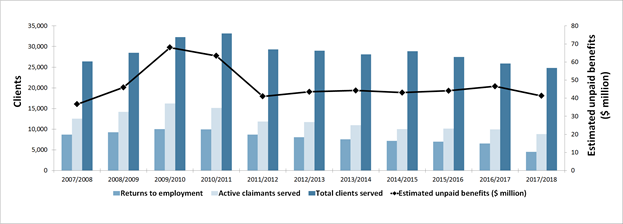

For a fourth consecutive year, the total number of EBSM-similar interventions in Newfoundland and Labrador grew, reaching 26,664 (+0.9%) in FY1718. The Employment Benefits’ share of all EBSM-similar interventions declined from 32.2% to 30.1%. A total of 2,795 (-24.4%) EI clients returned to employment after participating in an EBSM-similar program. Unpaid benefits (-24.8%) fell from $23.23 million to $17.47 million. EBSM total expenditures reached $128.9 million (+1.9 %), including $4.6 million from the province’s share of the additional $125 million LMDA investment announced in Budget 2017.

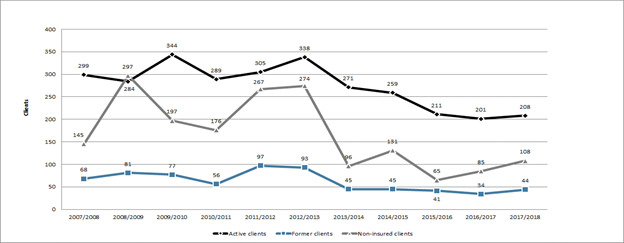

Chart 3 - Text version

| Active claimants | Former claimants | Non-insured clients | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2007/2008 | 12,648 | 2,616 | 2,200 |

| 2008/2009 | 12,325 | 2,204 | 2,561 |

| 2009/2010 | 13,466 | 3,114 | 2,302 |

| 2010/2011 | 11,215 | 2,748 | 2,171 |

| 2011/2012 | 10,027 | 2,405 | 2,031 |

| 2012/2013 | 9,124 | 1,992 | 2,046 |

| 2013/2014 | 8,831 | 1,928 | 1,980 |

| 2014/2015 | 8,850 | 2,513 | 1,126 |

| 2015/2016 | 8,941 | 2,095 | 1,297 |

| 2016/2017 | 9,308 | 1,812 | 1,232 |

| 2017/2018 | 9,390 | 2,370 | 1,107 |

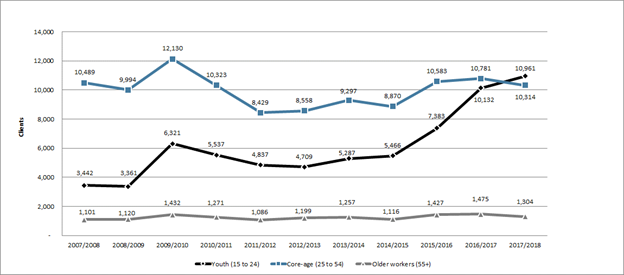

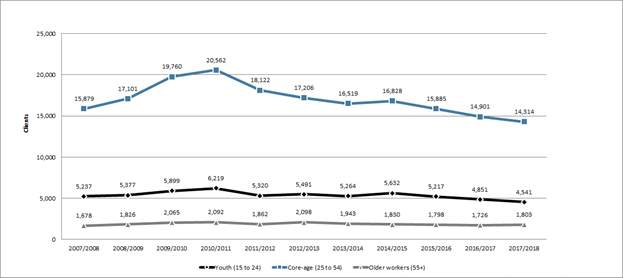

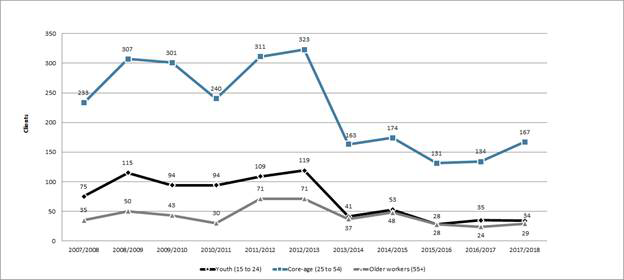

Chart 4 - Text version

| Youth (15 to 24) | Core-age (25 to 54) | Older workers (55+) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2007/2008 | 3,796 | 10,751 | 1,348 |

| 2008/2009 | 3,927 | 9,970 | 1,116 |

| 2009/2010 | 4,061 | 10,957 | 1,341 |

| 2010/2011 | 3,541 | 9,154 | 1,178 |

| 2011/2012 | 3,055 | 8,066 | 1,124 |

| 2012/2013 | 2,846 | 6,942 | 1,145 |

| 2013/2014 | 2,325 | 7,699 | 376 |

| 2014/2015 | 1,627 | 3,814 | 665 |

| 2015/2016 | 1,700 | 4,021 | 676 |

| 2016/2017 | 1,545 | 4,216 | 769 |

| 2017/2018 | 1,547 | 4,204 | 804 |

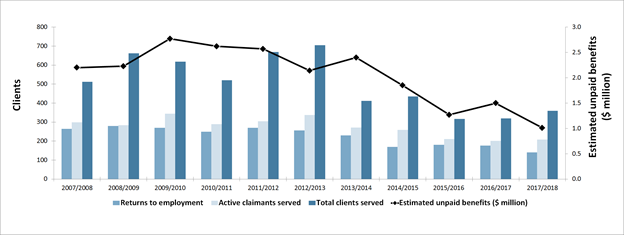

Chart 5 - Text version

| Returns to employment | Active claimants served | Total clients served | Estimated unpaid benefits ($ million) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2007/2008 | 8,856 | 12,648 | 17,464 | $24.00 |

| 2008/2009 | 7,995 | 12,325 | 17,090 | $26.83 |

| 2009/2010 | 6,526 | 13,466 | 18,882 | $32.94 |

| 2010/2011 | 6,857 | 11,215 | 16,134 | $31.20 |

| 2011/2012 | 6,335 | 10,027 | 14,463 | $26.71 |

| 2012/2013 | 6,114 | 9,124 | 13,162 | $30.42 |

| 2013/2014 | 5,918 | 8,831 | 12,739 | $25.69 |

| 2014/2015 | 3,298 | 8,850 | 12,489 | $25.35 |

| 2015/2016 | 3,306 | 8,941 | 12,333 | $22.25 |

| 2016/2017 | 3,696 | 9,308 | 12,352 | $23.23 |

| 2017/2018 | 2,795 | 9,390 | 12,867 | $17.47 |

Table 7 – Newfoundland and Labrador: EBSM-similar programming, 2017/2018

| Interventions | Year-over-Year Change | Expenditures ($ 000s) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Employment Benefits | ||||

| SD-R | Newfoundland and Labrador Skills Development | 3,608 | +12.5% | 90,748 |

| SD-A | Newfoundland and Labrador Skills Development | 2,012 | -26.4% | |

| TWS | Newfoundland and Labrador Wage Subsidies | 820 | +1.0% | 5,752 |

| SE | Newfoundland and Labrador Self-Employment Assistance | 286 | +21.2% | 7,314 |

| JCPs | Newfoundland and Labrador Job Creation Partnerships | 1,311 | -14.0% | 8,497 |

| Support Measures | ||||

| EAS | Newfoundland and Labrador Employment Assistance Services | 18,627 | +3.9% | 6,835 |

| LMPs | Newfoundland and Labrador Labour Market Partnerships | n/a | n/a | 4,485 |

| R&I | Research and Innovation | n/a | n/a | 5,229 |

2.2.3 Employment benefits

In FY1718, Newfoundland and Labrador delivered 8,037 Employment Benefits interventions, a 5.6% year-over-year decrease. Significant declines were recorded in SD-A (-722; -26.4%) and JCP (-213; -14.0%). On the other hand, SE (+50) and SD-R (+402) increased by 21.2% and 12.5%, respectively. The province spent $112.3 million (-4.0%) on Employment Benefits.

2.2.4 Support measures: EAS

For a fourth consecutive year, Newfoundland and Labrador delivered a growing total number of EAS interventions, reaching 18,627 (+3.9%) in FY1718. While Group Services (-259; -6.6%) dropped, Employment Services (+388; +4.8%) and Individual Counselling (+572; +9.5%) both grew. EAS total expenditures increased by 9.3% to $6.8 million.

The Province has increased its capacity to provide EAS to the larger urban centres in the province by contracting a third party service provider, Employment Options, to provide employment counselling and case management services to EI eligible clients in the larger communities; St. John’s, Corner Brook and Grand Falls. This increase in capacity and expansion aligns with the vision and goals of the Workforce Innovation Centre, designed to support innovations and impact employability, entrepreneurship, and attachment to the workforce in Newfoundland and Labrador. The focus is to identify ways to better help people prepare for, find, return to, or maintain sustainable employment. Employment Assistance Services will still be available at the Department’s employment centres across the province and assist EI eligible individuals with job searches, resume writing, labour market information, as well as career and employment needs assessments.

2.2.5 Other support measures: LMPs and R&I

In FY1718, total funding for LMPs ($4.5 million) and R&I ($5.2 million) rose significantly, by $1.6 million and $4.9 million, respectively. It should be noted that R&I was delivered for the second time in FY1718, after having been introduced in FY1617.

A Workforce Innovation Centre was established at College of the North Atlantic in February 2017. The Centre’s goal is to support research, testing and sharing of ideas and models of innovation in workforce development that will positively impact employability, entrepreneurship and job attachment in Newfoundland and Labrador.

During FY1718, the Workforce Innovation Centre funded eight multi-year initiatives, totaling over $3.1 million, to support applied research projects that test innovative approaches to address labour market issues and improve employment outcomes. Two examples of such projects include $588,000 over three years to Hospitality Newfoundland and Labrador, to support rural Newfoundlanders and Labradorians who wish to transition to work in the tourism sector, and close to $500,000 over three years for the Genesis Centre of Memorial University, to explore ways to increase entrepreneurship among women and immigrants in the technology sector.

Newfoundland and Labrador Workforce Innovation Centre (NLWIC) supporting sector innovation

With support under the Canada-Newfoundland and Labrador Labour Market Development Agreement, the NLWIC is helping set a new path of discovery. By fostering and establishing partnerships such as the Genesis Project, the NLWIC is supporting a spirit of innovation through initiatives that demonstrate innovation and identify methods to better support workforce development.

The Genesis Project is designed to explore ways to foster innovation in technology entrepreneurship through increased female participation and immigration initiatives. This project will reduce the barriers to entry for under-represented groups in the technology sector, and therefore increase the number of companies with women and/or immigrant founders in Newfoundland and Labrador.

2.3 Prince Edward Island

Following a 1.8% expansion in 2016, Prince Edward Island’s real GDP increased by 3.5% in 2017. The province’s economic growth is expected to have moderated to around 2% in 2018, according to forecasts from the major banks.

Prince Edward Island: EBSM Key Facts

| EI Clients | Non-Insured Clients |

|---|---|

4,271 |

1,852 |

| Interventions Type | 2017/2018 | Year-over-Year Change |

|---|---|---|

| Employment Benefits | 3,292 | 35.2% |

| Support Measures: EAS | 6,592 | 8.8% |

| Interventions Type | 2017/2018 | Year-over-Year Change(pp) |

|---|---|---|

| Employment Benefits | 33.3% | 4.6 |

| Support Measures: EAS | 66.7% | 4.6 |

| Total Expenditures | 2017/2018 ($ million) | Year-over-Year Change |

|---|---|---|

| Employment Benefits | $18.8 | 11.3% |

| Support Measures: EAS | $5.1 | 47.9% |

| LMPs and R&I | $1.7 | 17.3% |

| Total Expenditures1 | $25.6 | 1.8% |

| 2016/2017 | 2017/2018 | Year-over-Year Change |

|---|---|---|

| $7.14 | $7.13 | 0.27% |

- 1 Totals may not add up due to rounding; does not include accounting adjustments.

Compared to the previous fiscal year, Prince Edward Island’s labour market conditions in FY1718 improved, since employment (74,300) increased by 3.3% (+2,400) and the unemployment rate edged down by 0.7 percentage points, to 9.9%.

Employment growth was mostly realized in full-time employment (+2,100; +3.6%), while part-time employment (+300; +1.9%) only slightly increased.

In FY1718, employment growth in the good-producing sector (+1,500; +9.3%) was led by gains in construction (+700; +14.4%) and manufacturing (+600; +9.7%).

As for the more modest employment growth in the services-producing sector (+800; +1.5%), gains in trade (+1,000; +9.4%), as well as in health care and social assistance (+400; +3.7%), were partially offset by losses in business, building and other support services (-500; -20.3%) and accommodation and food services (-300; -5.3%).

In FY1718, Prince Edward Island continued to face demographic pressures such as an aging population and the out-migration of the working age population. To address those, the province released its population strategy titled ‘Recruit, Retain, Repatriate – A Population Action Plan for Prince Edward Island’. This strategy will create opportunities to repatriate skilled workers and entrepreneurs, and encourage people worldwide to immigrate to Prince Edward Island. In addition, this action plan sets out a course to grow the population and expand the skills and opportunities of all Islanders.

To ensure employers can access talented, work-ready individuals, the province identified the following labour market priorities for FY1718:

- assist Islanders in developing the necessary skills to prepare for, find and keep employment;

- provide employers access to a skilled workforce;

- ensure communities in Prince Edward Island are able to respond effectively to labour market opportunities and challenges;

- provide financial assistance to non-profit community organizations for short term projects, that provide unemployed individuals with a valuable work experience to develop new skills and increase the potential for long term employment in the labour market;

- invest in supports that provide unemployed individuals with financial and entrepreneurial assistance to launch a new business;

- provide short term funding to encourage partners to develop activities or strategies that will assist individuals or employers who are impacted by labour market challenges in a community or an industry;

- provide funding to external service providers across the province to deliver employment assistance services to assist unemployed Islanders connect to the labour force; and,

- support research and innovative projects aimed at strengthening the ability of the province to respond to emerging labour market realities.

2.3.1 Managing for Results

Throughout FY1718, Workforce and Advanced Learning met both formally and informally with employers, industry associations, chambers of commerce, community based organizations, post-secondary institutions and individuals to learn more about the labour market issues of importance to them, as well as of relevance to job seekers. This collaborative effort ensured programs and services were responsive, timely, relevant and aligned with the labour force needs of PEI’s key economic sectors. As well, ongoing engagement through program delivery provided opportunities for the department to understand the needs, wants and expectations of key stakeholders across the province.

The department supported a number of activities including community outreach, participation in joint tables with federal colleagues and representatives of the Indigenous and Francophone communities along with other key partners. Through this process, the province received valuable feedback and input that informed their design and delivery of the programs and services.

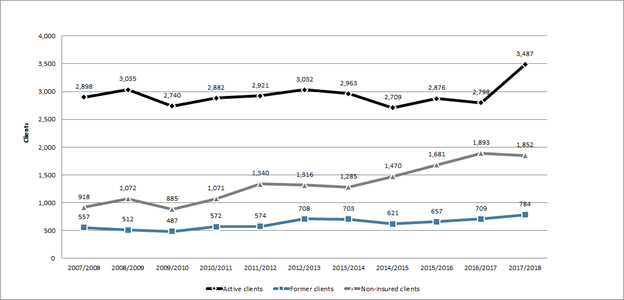

2.3.2 Clients, Interventions and Expenditures

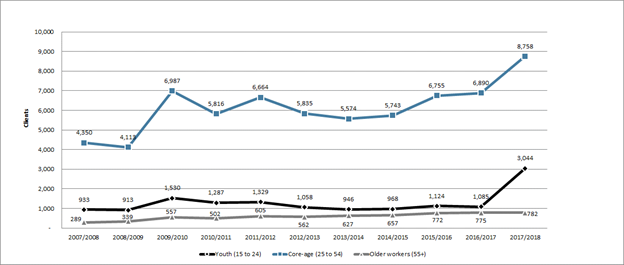

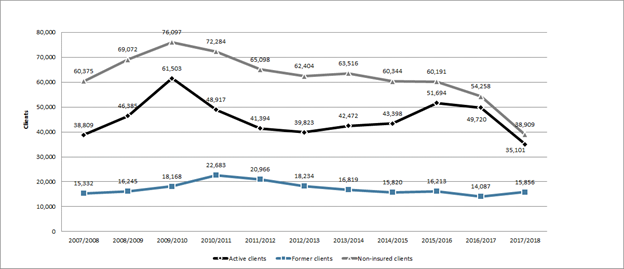

In FY1718, for a third consecutive year, Prince Edward Island served a growing number of clients, totalling 6,123 (+13.4%). While the numbers of both active (+689; +24.6%) and former claimants (+75; +10.6%) rose, non-insured clients (-41; -2.2%) experienced a drop. With respect to their shares of total number of clients served, active claimants (56.9%) advanced by 5.1 percentage points, while the shares of former claimants (12.8%) and non-insured clients (30.2%) decreased by 0.3 and 4.8 percentage points, respectively.

The province delivered, for a fourth consecutive year, a growing number of interventions, reaching 9,884 (+16.4%) in FY1718. The share of EAS relative to the total number of interventions continued to decline, totalling 66.7% (-4.6 percentage points) of all interventions in FY1718.

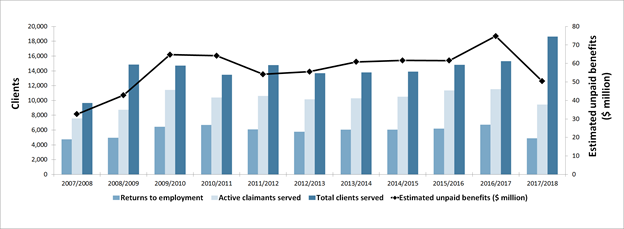

A total number of 2,202 (+5.8%) EI clients returned to employment after participating in EBSM-similar programming. Unpaid benefits remained stable at $7.13 million (-0.3%). Prince Edward Island spent $25.6 million (-1.8%) for EBSM expenditures, including $1.1 million from the additional LMDA funding announced in the Budget 2017.

Chart 6 - Text version

| Active clients | Former clients | Non-insured clients | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2007/2008 | 2,898 | 557 | 918 |

| 2008/2009 | 3,035 | 512 | 1,072 |

| 2009/2010 | 2,740 | 487 | 885 |

| 2010/2011 | 2,882 | 572 | 1,071 |

| 2011/2012 | 2,921 | 574 | 1,340 |

| 2012/2013 | 3,032 | 708 | 1,316 |

| 2013/2014 | 2,963 | 703 | 1,285 |

| 2014/2015 | 2,709 | 621 | 1,470 |

| 2015/2016 | 2,876 | 657 | 1,681 |

| 2016/2017 | 2,798 | 709 | 1,893 |

| 2017/2018 | 3,487 | 784 | 1,852 |

Chart 7 - Text version

| Youth (15 to 24) | Core-age (25 to 54) | Older workers (55+) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2007/2008 | 1,003 | 2,645 | 323 |

| 2008/2009 | 1,060 | 2,784 | 323 |

| 2009/2010 | 950 | 2,504 | 275 |

| 2010/2011 | 1,124 | 2,705 | 312 |

| 2011/2012 | 1,202 | 2,937 | 364 |

| 2012/2013 | 1,265 | 3,023 | 446 |

| 2013/2014 | 1,259 | 2,920 | 463 |

| 2014/2015 | 1,276 | 2,776 | 438 |

| 2015/2016 | 1,456 | 2,954 | 508 |

| 2016/2017 | 1,542 | 3,137 | 458 |

| 2017/2018 | 2,309 | 3,072 | 499 |

Chart 8 - Text version

| Returns to employment | Active claimants served | Total clients served | Estimated unpaid benefits ($ million) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2007/2008 | 2,148 | 2,898 | 4,373 | $7.10 |

| 2008/2009 | 2,186 | 3,035 | 4,619 | $7.69 |

| 2009/2010 | 1,839 | 2,740 | 4,112 | $8.92 |

| 2010/2011 | 2,159 | 2,882 | 4,525 | $9.07 |

| 2011/2012 | 2,034 | 2,921 | 4,835 | $8.16 |

| 2012/2013 | 1,939 | 3,032 | 5,056 | $7.53 |

| 2013/2014 | 2,194 | 2,963 | 4,951 | $7.19 |

| 2014/2015 | 1,934 | 2,709 | 4,800 | $6.52 |

| 2015/2016 | 1,997 | 2,876 | 5,214 | $6.99 |

| 2016/2017 | 2,081 | 2,798 | 5,400 | $7.14 |

| 2017/2018 | 2,202 | 3,487 | 6,123 | $7.13 |

| Interventions | Year-over-Year Change | Expenditures ($ 000s) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Employment Benefits | ||||

| SD-R | Training PEI—Individual | 2,123 | +98.4% | 12,501 |

| SD-A | Training PEI—Apprentice | 267 | -9.5% | |

| TWS | Employ PEI | 696 | -16.3% | 3,512 |

| SE | Self-Employ PEI | 146 | -14.1% | 2,061 |

| JCPs | Work Experience PEI | 60 | -11.8% | 692 |

| Support Measures | ||||

| EAS | Employment Assistance Services | 6,592 | +8.8% | 5,120 |

| LMPs | Labour Market Partnerships | N/A | N/A | 1,721 |

| R&I | Research & Innovation | N/A | N/A | 0 |

2.3.3 Employment benefits

In FY1718, for a third consecutive year, the number of Employment Benefits interventions grew, totaling 3,292 (+35.2%). With the exception of SD-R (+1,053; +98.4%), all other benefit-types dropped: TWS (-136; -16.3%), SE (-24; -14.1%), JCP (-8; -11.8%) and SD-A (-28; -9.5%). The significant increase in Skills Development – Regular interventions can be attributed to the implementation of the Career Connect program in FY1718. Career Connect provides unemployed workers, who qualify for Employment Insurance (EI) benefits, an opportunity to continue to receive those benefits while attending full-time, post-secondary training within Canada for the duration of their claim. Employment Benefits expenditures went down, from to $21.1 million to $18.8 million, representing a year-over-year decrease of 11.3%.

The province used its share of the additional LMDA funding announced in the Budget of 2017 to support various priorities, including employment services for unemployed individuals, address sectoral employment challenges through industry associations and sector councils, develop incentives to hire and train unemployed workers and recent graduates, as well as to support new business start-ups.

2.3.4 Support measures: EAS

In FY1718, EAS interventions in Prince Edward Island rose by 8.8% to 6,592. Employment Services (+623, +12.7%) advanced, while Individual Counselling (-90; -7.7%) dropped. EAS total expenditures reached $5.1 million (+47.9%).

2.3.5 Other support measures: LMPs and R&I

In FY1718, LMPs expenditures (+28.1%) grew from $1.3 million to $1.7 million. There were no reported expenditures under R&I for FY1718.

Jenna’s journey to sustainable employment

Jenna was interested in exploring new career options in trades and increasing her employability skills. She was able to find her dream job by progressing along a path to sustainable employment which included:

1) Career exploration via a program offered by the Women’s Network PEI;

2) Training to develop skills needed to succeed in the workforce by enrolling in and graduating from the Heritage Retrofit Carpentry program; and

3) An opportunity to bridge education with work experience through the Graduate Mentorship program.

With a lot of perseverance and support from the province, Jenna developed new skills and abilities that will contribute to the success of the renovations at the historic Province House in Charlottetown.

2.4 Nova Scotia

For the second year in a row, Nova Scotia’s real GDP growth in 2017 was 1.5%. It was the fourth consecutive year with economic growth. Real GDP growth is expected to have eased in 2018 to about 1%.

Nova Scotia: EBSM Key Facts

| EI Clients | Non-Insured Clients |

|---|---|

11,549 |

4,337 |

| Interventions Type | 2017/2018 | Year-over-Year Change |

|---|---|---|

| Employment Benefits | 4,138 | 7.0% |

| Support Measures: EAS | 26,653 | 6.9% |

| Interventions Type | 2017/2018 | Year-over-Year Change(pp) |

|---|---|---|

| Employment Benefits | 13.4% | 0.1 |

| Support Measures: EAS | 86.6% | 0.1 |

| Total Expenditures | 2017/2018 ($ million) | Year-over-Year Change |

|---|---|---|

| Employment Benefits | $51.3 | 6.1% |

| Support Measures: EAS | $29.0 | 9.7% |

| LMPs and R&I | $2.3 | 18.8% |

| Total Expenditures1 | $82.6 | 0.8% |

| 2016/2017 | 2017/2018 | Year-over-Year Change |

|---|---|---|

| $24.02 | $23.91 | 0.5% |

- 1 Totals may not add up due to rounding; does not include accounting adjustments.

After four consecutive years of decline, employment levels in Nova Scotia improved in FY1718, rising by 3,500 (+0.8%). During the same period, the unemployment rate rose from 8.1% to 8.3%, as more Nova Scotians joined the labour force.

Employment grew in the goods-producing sector (+1,300; 1.6%), particularly in utilities (+500; +14.4%) and manufacturing (+3,200; +11.4%). However, these gains were partially offset by employment losses in forestry, fishing, mining, oil and gas (-1,700; -15.1%). Employment in the services-producing sector (+2,100; +0.6%) also improved year-over-year, most notably in accommodation and foodservices (+1,800; +6.1%); public administration (+1,600; +5.6%); and information, culture and recreation (+700; +4.6%). This expansion was partially offset by losses in health care and social assistance (-4,700; -6.2%) and in other services (-800; -4.0%).

To address labour market challenges related to an aging population, shrinking workforce and shifting industrial composition, Nova Scotia engaged multiple stakeholders to develop program and service priorities. Accordingly, the province invested in high-skill training, with the goal to develop and maintain a competitive workforce. In addition, the province continued to support the integration of underrepresented groups, by reducing barriers to employment, with the view of stimulating economic growth and enhancing the labour market.

2.4.1 Managing for results

Nova Scotia is in its second year of implementation of a transformed employment services system, which includes a common branding of all employment service centres as Nova Scotia Works. Eighteen third-party, community-based organizations have agreements with the province to deliver a common and consistent suite of services to all Nova Scotians. The transformation of the employment services system in Nova Scotia has resulted in the implementation of a performance management approach that focuses on outcome measures, monitoring through regular collection and reporting to track progress, evaluation of achieving desired outcomes and incorporating learnings gleaned through monitoring and evaluation into program design decisions.

Innovation and evidence-based approaches to client service delivery and programming are beginning to be fostered through a newly created Centre for Employment Innovation. Diversity and inclusion - meeting the needs of all Nova Scotians – is a focus of the transformed system which now provides specialized services behind ‘one door’ versus multiple employment services doors providing certain specialized services. Nova Scotians and service providers have responded well to the new structures and focus on client outcomes is increasing over time.

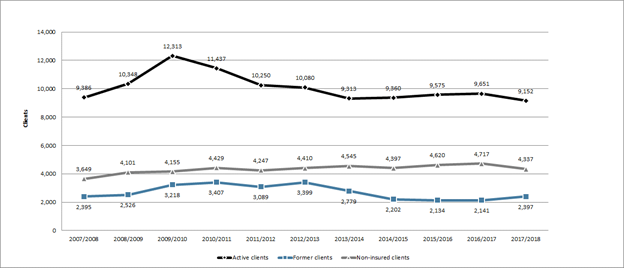

2.4.2 Clients, interventions and expenditures

Nova Scotia served fewer clients in FY1718 compared to FY1617, for a total of 15,886 clients (-3.8%). Both active claimants (9,152) and non-insured clients (4,337) fell by 5.2% and 8.1%, respectively, while former claimants (2,397) rose by 12.0%. Following the same trends, all client-types’ shares of the total number of clients served moved in the same direction, with active claimants (57.6%) and non-insured clients (27.3%) decreasing by 0.8 and 1.3 percentage points, respectively; while former claimants (15.1%) advanced by 2.1 percentage points.

In FY1718, the province delivered 30,791 (-6.9%) interventions. At 86.6%, the share of EAS continued to remain the largest of all EBSM-similar interventions. A total of 5,624 (+9.1%) individuals returned to employment following participation in the programs. Unpaid benefits decreased from $24.02 million to $23.91 million (-0.5%). EBSM total expenditures declined, reaching $82.6 million (-0.8% year-over-year). This amount includes Nova Scotia’s portion of the additional $125 million in LMDA investments announced in Budget 2017. This represents $4.6 million for FY1718. About $2.3 million of this funding has been directed to the delivery of employment services to individuals who are job-ready but face significant employment barriers in order to integrate them into employment through pre-employment and employment services focused on personal, academic and work skill development. This program is delivered in partnership with the Department of Community Services and provincial funding support.

Chart 9 - Text version

| Active clients | Former clients | Non-insured clients | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2007/2008 | 9,386 | 2,395 | 3,649 |

| 2008/2009 | 10,348 | 2,526 | 4,101 |

| 2009/2010 | 12,313 | 3,218 | 4,155 |

| 2010/2011 | 11,437 | 3,407 | 4,429 |

| 2011/2012 | 10,250 | 3,089 | 4,247 |

| 2012/2013 | 10,080 | 3,399 | 4,410 |