Discover Canada - Who We Are

Who We Are

Listen to this chapter

Discover Canada: The Rights and Responsibilities of Citizenship - Who We Are

Duration: 11 minutes, 24 seconds. Read by The Rt. Hon. Adrienne Clarkson.

Download this chapter: MP3 (MP3, 15.67MB)

You can also download all of Discover Canada (MP3, 155.94MB) as a single file.

The audio may take a moment to load.

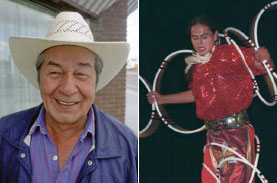

(From left to right) Métis from Alberta; Cree dancer

[ See larger version ]

Canada is known around the world as a strong and free country. Canadians are proud of their unique identity. We have inherited the oldest continuous constitutional tradition in the world. We are the only constitutional monarchy in North America. Our institutions uphold a commitment to Peace, Order, and Good Government, a key phrase in Canada’s original constitutional document in 1867, the British North America Act. A belief in ordered liberty, enterprise, hard work and fair play have enabled Canadians to build a prosperous society in a rugged environment from our Atlantic shores to the Pacific Ocean and to the Arctic Circle—so much so that poets and songwriters have hailed Canada as the “Great Dominion.”

To understand what it means to be Canadian, it is important to know about our three founding peoples—Aboriginal, French and British.

(From left to right) Inuit children in Iqaluit, Nunavut; Haida artist Bill Reid carves a totem pole

Aboriginal Peoples

The ancestors of Aboriginal peoples are believed to have migrated from Asia many thousands of years ago. They were well established here long before explorers from Europe first came to North America. Diverse, vibrant First Nations cultures were rooted in religious beliefs about their relationship to the Creator, the natural environment and each other.

Aboriginal and treaty rights are in the Canadian Constitution. Territorial rights were first guaranteed through the Royal Proclamation of 1763 by King George III, and established the basis for negotiating treaties with the newcomers— treaties that were not always fully respected.

From the 1800s until the 1980s, the federal government placed many Aboriginal children in residential schools to educate and assimilate them into mainstream Canadian culture. The schools were poorly funded and inflicted hardship on the students; some were physically abused. Aboriginal languages and cultural practices were mostly prohibited. In 2008, Ottawa formally apologized to the former students.

In today’s Canada, Aboriginal peoples enjoy renewed pride and confidence, and have made significant achievements in agriculture, the environment, business and the arts.

Today, the term Aboriginal peoples refers to three distinct groups:

Indian refers to all Aboriginal people who are not Inuit or Métis. In the 1970s, the term First Nations began to be used. Today, about half of First Nations people live on reserve land in about 600 communities while the other half live off-reserve, mainly in urban centres.

The Inuit, which means “the people” in the Inuktitut language, live in small, scattered communities across the Arctic. Their knowledge of the land, sea and wildlife enabled them to adapt to one of the harshest environments on earth.

The Métis are a distinct people of mixed Aboriginal and European ancestry, the majority of whom live in the Prairie provinces. They come from both French- and English-speaking backgrounds and speak their own dialect, Michif.

About 65% of the Aboriginal people are First Nations, while 30% are Métis and 4% Inuit.

Unity in Diversity

John Buchan, the 1st Baron Tweedsmuir, was a popular Governor General of Canada (1935-40). Immigrant groups, he said, “should retain their individuality and each make its contribution to the national character.” Each could learn “from the other, and … while they cherish their own special loyalties and traditions, they cherish not less that new loyalty and tradition which springs from their union” (Canadian Club of Halifax, 1937).

The 15th Governor General is shown here in Blood (Kainai First Nation) headdress.

(From left to right)

St Patrick’s Day Parade, Montreal, Quebec

Highland dancer at Glengarry Highland Games, Maxville, Ontario

Celebrating Fête Nationale, Gatineau, Quebec

Acadian fiddler, Village of Grande-Anse, New Brunswick

English and French

Canadian society today stems largely from the English-speaking and French-speaking Christian civilizations that were brought here from Europe by settlers. English and French define the reality of day-to-day life for most people and are the country’s official languages. The federal government is required by law to provide services throughout Canada in English and French.

Today, there are 18 million Anglophones—people who speak English as a first language—and 7 million Francophones—people who speak French as their first language. While the majority of Francophones live in the province of Quebec, one million Francophones live in Ontario, New Brunswick and Manitoba, with a smaller presence in other provinces. New Brunswick is the only officially bilingual province.

The Acadians are the descendants of French colonists who began settling in what are now the Maritime provinces in 1604. Between 1755 and 1763, during the war between Britain and France, more than two-thirds of the Acadians were deported from their homeland. Despite this ordeal, known as the “Great Upheaval,” the Acadians survived and maintained their unique identity. Today, Acadian culture is flourishing and is a lively part of French-speaking Canada.

Quebecers are the people of Quebec, the vast majority French-speaking. Most are descendants of 8,500 French settlers from the 1600s and 1700s and maintain a unique identity, culture and language. The House of Commons recognized in 2006 that the Quebecois form a nation within a united Canada. One million Anglo-Quebecers have a heritage of 250 years and form a vibrant part of the Quebec fabric.

The basic way of life in English-speaking areas was established by hundreds of thousands of English, Welsh, Scottish and Irish settlers, soldiers and migrants from the 1600s to the 20th century. Generations of pioneers and builders of British origins, as well as other groups, invested and endured hardship in laying the foundations of our country. This helps explain why Anglophones (English speakers) are generally referred to as English Canadians.

Becoming Canadian

Some Canadians immigrate from places where they have experienced warfare or conflict. Such experiences do not justify bringing to Canada violent, extreme or hateful prejudices. In becoming Canadian, newcomers are expected to embrace democratic principles such as the rule of law.

Celebration of Cultures, Edmonton, Alberta

(From left to right)

Ismaili Muslims in the Calgary Stampede, Alberta

Caribbean cultural festival,Toronto, Ontario

Ukrainian Pysanka Festival, Vegreville, Alberta

Young Polish dancers in Oliver, British Columbia

Diversity in Canada

[ See larger version ]

The majority of Canadians were born in this country and this has been true since the 1800s. However, Canada is often referred to as a land of immigrants because, over the past 200 years, millions of newcomers have helped to build and defend our way of life.

Many ethnic and religious groups live and work in peace as proud Canadians. The largest groups are the English, French, Scottish, Irish, German, Italian, Chinese, Aboriginal, Ukrainian, Dutch, South Asian and Scandinavian. Since the 1970s, most immigrants have come from Asian countries.

Non-official languages are ly spoken in Canadian homes. Chinese languages are the second most-spoken at home, after English, in two of Canada’s biggest cities. In Vancouver, 13% of the population speak Chinese languages at home; in Toronto, the number is 7%.

The great majority of Canadians identify as Christians. The largest religious affiliation is Catholic, followed by various Protestant churches. The numbers of Muslims, Jews, Hindus, Sikhs and members of other religions, as well as people who state “no religion” are also growing.

In Canada the state has traditionally partnered with faith communities to promote social welfare, harmony and mutual respect; to provide schools and health care; to resettle refugees; and to uphold religious freedom, religious expression and freedom of conscience.

Canada’s diversity includes gay and lesbian Canadians, who enjoy the full protection of and equal treatment under the law, including access to civil marriage.

Together, these diverse groups, sharing a common Canadian identity, make up today’s multicultural society.

(From left to right)

Christmas in Gatineau

Chinese-Canadian war veterans

Notre-Dame-des-Victoires, Québec City

Chinese New Year celebration, Vancouver

Olympian Marjorie Turner-Bailey of Nova Scotia is a descendant of black Loyalists, escaped slaves and freed men and women of African origin who in the 1780s fled to Canada from America, where slavery remained legal until 1863.