Evaluation of the Immigration Loan Program

4. Findings Related to Program Performance

This section of the report presents the results of the assessment of program performance in relation to the outcomes regarding determining need and ability to repay, access, understanding of the loan, the role of CIC Collection Services in facilitating loan repayment, loan repayment and impact on settlement. As the majority of loan recipients are refugees, this section of the report focuses on the program’s performance primarily in relation to this group.

4.1 Determining Need and Ability to Repay

The Overseas Processing manual for Loans (OP 17) is the overarching guidance for the delivery of immigration loans.Footnote 40 OP 17 indicates that, in order to approve a loan, an officer must review three key criteria:

- The need for a loan, which focuses on the individuals’ ability to find employment and the type of employment most likely to be found;

- The potential ability to repay, which looks at an individual’s ability to earn income, capacity to use one of Canada’s official languages, current employment and transferable skills, the need for extensiveFootnote 41 retraining or additional education in order to compete in the labour market, temporary or permanent restrictions on employment due to medical problems or long-term illness and the presence of other financial obligations (including number of dependent family members); and

- Contributing factors, some of which need to be assessed in combination with other factors, as they are not considered to be “stand-alone”. These factors include age, official language capacity, level of education, number of family members and their income, and motivation and initiative.

A comparison with other loan programs revealed that assessment criteria are common when the Government of Canada issues loans. For example, the eligibility criteria for Employment and Social Development Canada’s (ESDC) Canada Student Loans Program include: the student category (single or married, dependent or independent), the post-secondary education expenses (tuition, fees, etc.), and financial resources (income, savings, assets, parental or spousal contributions, etc.).Footnote 42

Finding: While TB Directives stipulate that loans are to be authorized on the expectation of full repayment, the procedures required to assess a potential recipient’s ability to repay a loan, as outlined in OP 17, are not practical, given that limited information and time are available to conduct this assessment as part of refugee processing overseas. Furthermore, refusing a loan could prevent the resettlement of the refugee.

According to the TB Directive on Loans and Loan Guarantees: “Loans are authorized appropriately” and “on the expectation of full repayment of principal and interest...Accordingly, if a fixed repayment schedule is not feasible or if repayment is conditional on some future event, a loan may not be issued.”Footnote 43

The assessment for transportation and admissibility loans is done within the context of the selection interview with refugees.Footnote 44 The document review and interviews revealed that the potential ability of a specific individual to repay an immigration loan is very difficult to assess in this context, due to time constraints and a lack of information. Interviews with visa offices indicated that very little time is spent on the loan during the selection interview – typically between one and five minutes. As well, it was mentioned in a few interviews with CIC representatives that the need for the loan overrides the ability to repay, as the main focus at that point in time is refugee resettlement. In addition, a review of the overseas refugee selection process, conducted as part of the evaluation, found that the immigration loan comprises a very small component of the overall selection interview process.Footnote 45

Program guidance requires visa officers to assess applicants against the criteria required to come to Canada as a refugee, as well as assess them against the criteria for an immigration loan.Footnote 46 OP 17 notes that the loan assessment is intended to be “distinct” from the assessment in the selection interview.Footnote 47 However, the resulting decisions are inextricably linked. The loan is the main mechanism currently being used to assist refugees in coming to Canada, supporting the mandate of the refugee resettlement program. For refugees without financial means, where no contribution funds or other avenues of assistance are available, a refusal for a loan would prevent them from coming to Canada, irrespective of the selection decision. Therefore, considering the refugee context, a refusal for a loan would not be feasible, as it would be counter to the objectives of the resettlement program, which the loan program is trying to support.

A review of the refugee selection process revealed that, at the time the eligibility for the loan is being decided, various decisions surrounding the refugee’s application would not be normally determined (e.g. health, final destination, etc.).Footnote 48 There are no formal tools to assess official language capacity and employability. Rather, the visa officer is asked to consider a complex myriad of factors which may affect linguistic ability and employment potential, and try to predict how the individual will fare in Canada. OP 17 does acknowledge that the potential ability to repay a loan “is more difficult to evaluate as it involves weighing many contributing factors”, and that “sound judgment and discretion are essential to evaluate an applicant’s ability, or potential ability, to repay a loan.”Footnote 49

In sum, considerable guidance is provided to assess eligibility for the loan in OP 17. However, irrespective of the guidance provided, the assessment of the potential ability to repay a loan is impractical given the timing and circumstances of the overseas refugee processing context, and given the critical role of the loan in ensuring that refugees have the means to come to Canada once selected.

4.2 Access

4.2.1 Access to Loans

As noted earlier, when the Immigration Loan Program was introduced in 1951, it was intended to assist immigrants from Europe whose services were urgently needed and who could not afford their own transportation.Footnote 50 Over time, the program evolved into a mechanism to help finance the resettlement of refugees.Footnote 51

Finding: While several immigration classes are eligible to receive immigration loans, the program is being used primarily to resettle refugees from abroad.

As described in Section 1.2.2, foreign nationals, permanent residents, and Canadian citizens are eligible to apply for a loan, with eligibility linked to the purpose of the loan to be issued.Footnote 52 However, OP 17 indicates that “[in] practice, the majority of loans are approved for Convention refugees and their family dependants, and members of the Humanitarian-protected persons abroad classes, who come to Canada, either with government assistance or through private sponsorships, as part of the Annual Refugee Plan.”Footnote 53 This was confirmed in the administrative data, which revealed that, between 2008 to 2012, the vast majority of loan recipients (97.8%) were resettled refugees – 57.5% were GARs and 40.3% were PSRs. Correspondingly, 93.5% of GAR cases and 87.9% of PSR cases resettled in Canada during this timeframe received at least one loan (see Table 13).Footnote 54 Furthermore, it was noted in some interviews with CIC representatives that, by default, all refugees get a loan overseas.Footnote 55

| Fiscal Year | GAR cases # | GAR Cases % | PSR cases # | PSR Cases % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2008 | 2,567 | 92.9% | 1,359 | 87.2% |

| 2009 | 2,668 | 92.6% | 1,962 | 89.5% |

| 2010 | 2,662 | 94.2% | 1,783 | 84.8% |

| 2011 | 2,574 | 93.9% | 2,299 | 89.8% |

| 2012 | 2,084 | 93.8% | 1,704 | 87.7% |

| Overall (2008 to 2012) | 12,555 | 93.5% | 9,107 | 87.9% |

Source: CIC IFMS (SAP) System and FOSS/GCMS.

The interviews indicated that those in need have access to loans. However, it was observed during the evaluation that the Immigration Loan Program is broadly viewed by CIC and other stakeholders as a “refugee program”, and that it is implemented as such by CIC, as evidenced by the target set for program reach (100% of resettled refugee principal applicants landing in Canada),Footnote 56 as well as program documentation.Footnote 57

A review of publicly available program information found that immigration loans do not appear to be broadly promoted by CIC. While the CIC website includes information on immigration loans, it is general in nature, not easily located, and is targeted to refugees.Footnote 58 The CIC website also includes online bulletins that contain some information on loans. However, they are specifically targeted to GARs and PSRs and presume that the individual will be given a loan (i.e., there is no information on eligibility), further supporting the view held by some interviewees that loans are provided automatically to refugees.Footnote 59

Finding: While assistance loans are available to meet labour market access needs, they are, in practice, used almost exclusively to pay for housing rental and utility deposits.

The evaluation found that there are some missed opportunities – specifically, in relation to the assistance loan. While this type of loan is broadly available to foreign nationalsFootnote 60 for various types of assistance (i.e., assistance for the basic needs of life, basic household needs and labour market access needs),Footnote 61 the manner in which the program is being implemented limits its use.

Under the category “basic needs of life”, a departmental audit revealed that, generally, assistance loans are being issued to GARs for the purpose of paying rental and utility deposits.Footnote 62 This was further confirmed in the administrative data, which revealed that, between 2008 and 2012, 97% of assistance loans were issued to GARs, and in interviews with CIC representatives who indicated that because deposits are mandatory in many regions of the country but are not covered under RAP start-up allowances, the loan is commonly used for this purpose.

With respect to “basic household needs”, no mention is made of loans for this purpose in the Inland Processing Manual for Convention Refugees Abroad (IP 3), and no mention was made of its use by interviewees.

With respect to labour market access needs, IP 3, Part 2 indicates that assistance loans can cover certain costs, such as the purchase of required tools or work clothing or the costs of licensing exams; however, interviews with CIC representatives confirmed it is rarely used for this purpose. After further review of IP 3, it was found that CIC officers in Canada are instructed to use this type of assistance loan in cases “where a job is secured” or “where employment is offered”.Footnote 63 In essence, an applicant must have already accessed the labour market in order to be eligible for this type of loan, and cannot use this type of loan to improve their employability, further limiting its use in assisting with settlement needs.

4.2.2 Access to Overseas Contributions and Loan Conversions

As stated earlier, the Immigration Loan Program allows for access to RAP contributions,Footnote 64 instead of a loan, for certain GARsFootnote 65 with special needs, in order to pay transportation and medical costs associated with coming to Canada. These refugees are understood to have “higher settlement needs”, and thus may require additional support in Canada to become self-sufficient. Operational Bulletin 513 states that PSRs are “not normally eligible for contributions” and in practice, only GARs receive overseas contributions. While PSRs do not receive contributions, sponsors can assume the medical and travel costs on behalf of the sponsored refugees, should they choose to do so.Footnote 66

PSRs are “not normally eligible for contributions; however, the sponsor may be willing to undertake medical and travel costs on behalf of the sponsored refugees”Footnote 67.

Eligibility for access to RAP contributions is generally determined prior to the arrival of the refugee in Canada, and arrangements are made overseas for a contribution to be granted in lieu of a loan (i.e. an overseas contribution). As the responsible authority for the RAP budget, IPMB reviews all requests from visa officers and approves or refuses access based on the case information and available budget.Footnote 68 The RAP annual budget allocated for the transportation and medical costs of refugees with higher settlement needs was increased from $400,000Footnote 69 to $500,000 in FY 2004/05.Footnote 70

For a five-year period (2006-07 to 2010-11), eligibility for access to these contributions could be determined after the refugee’s arrival, with arrangements made to convert an existing loan to a contribution in Canada (i.e., allowing for an in-Canada loan conversion). These arrangements were made through calls for requests for conversions, which were sent to regional and local CIC offices, who in turn, consulted with RAP SPOs before submitting these requests to IPMB for final decision.Footnote 71

Finding: The budget allocated for contributions is not sufficient to meet the apparent demand. While contributions can be provided overseas, there is currently no mechanism in place to convert a loan to a contribution after arrival in Canada.

Currently, the total amount available for contributions per year is $500,000, equivalent to about 4% of the total value of loans provided annually ($12.7M on average).

It is estimated in OP 17 that a $400,000 budget could “reasonably accommodate between 40 and 50 refugee families per year”.Footnote 72 Using this information as a guide, the current budget of $500,000 could accommodate between 50 and 63 families, or about 2% of GAR cases each year.Footnote 73 Based on an analysis of 2003-2012 program data, access to contributions was slightly higher than this prediction, though still infrequent, with only 4% of the 26,342 GAR cases having had access to a contribution.Footnote 74

Exhibit 1 – Loan Conversions

In 2012, the practice of in-Canada loan conversions was stopped after a review of the practice led by CIC’s Finance Branch revealed that in-Canada loan conversions were not in line with the Terms and Conditions of the RAP contribution fund. Advice received from the Treasury Board Secretariat (TBS) during the review indicated that the Debt Write-off Regulations supersede the Policy on Transfer Payments and confirmed that transportation and medical costs were not an eligible expenditure for GARs under the RAP Terms and Conditions. This was confirmed by a review of program documentation for the evaluation which showed that the RAP contribution fund is divided into two parts, with two sets of eligible recipients and expenditures. While GARs are eligible recipients for RAP, travel and medical costs overseas are not an eligible expense for GARs. Rather, these costs are an eligible expense for service provider organizations, such as the IOM. Therefore, RAP funds can be used to reimburse the IOM for the travel and medical costs overseas (i.e. overseas contributions), but cannot be given to GARs to help them repay their loan in Canada (i.e. in-Canada loan conversion).

Guidance provided to officers in determining whether or not to recommend a contribution reflects the limited funding available. While the Operational Bulletin released in 2013 encouraged visa officers overseas to be proactive in putting forward requests for contributions,Footnote 75 OP 17 warns “that not every special-needs refugee will be allowed to access the contribution fund”Footnote 76 It also notes that as available contribution dollars are limited, IPMB may look at other options when reviewing each contribution request, such as the possibility of assistance from a sponsor.

There is evidence that the loss of the loan conversion mechanism (see Exhibit 1) has hampered the program’s ability to adequately provide access to contributions for those in need. As shown earlier, the overseas context does not lend itself well to assessing a person’s potential ability to repay a loan (and therefore, the ability to assess the need for a contribution). Additionally, some interviewees indicated that issues affecting the ability to repay may not present themselves until after arrival in Canada. This was supported by findings from the RAP SPO and SAH surveys which showed that many respondents had encountered refugees, at least sometimes, who at first looked like they would have the potential ability to repay a loan, but for whom it later became apparent (after arrival) that there was no way that they would ever be able to repay the loan.

A review of administrative data revealed that contribution spending for the Immigration Loan Program, along with the distribution of contributions among GAR cases, were highest in the years when the in-Canada loan conversions were permitted. During this timeframe, access to contributions peaked at 8.7% of GAR cases in 2009, and averaging 6.8% of GAR cases over the four-year period. In fact, during this period, spending consistently surpassed the $500,000 budget.

Currently, in the absence of the loan conversion mechanism through RAP, loans that cannot be repaid have to be written-off. The write-off mechanism, however, does not waive the debt; it is an accounting mechanism and not a form of forgiveness. As noted previously in Section 3.1, the write-off “does not forgive the debt or release the debtor from the obligation to pay; nor does it affect the right of the Crown to enforce collection in the future.”Footnote 77 As such, the write-off mechanism does not adequately replace the loan conversions, which released the recipient from any further responsibility for the debt, and is not in line with the overall intent of the contributions component of the program: to provide additional settlement support to those with high settlement needs.Footnote 78

In sum, budget constraints as well as the lack of a mechanism to provide assistance after arrival in Canada undermine the intent of the contribution funding, which is to provide a mechanism to assist those who are deemed to not have the potential to repay a loan.

4.3 Recipients’ Understanding of the Loan

The recipients’ understanding of the loan was assessed at two different points in time: 1) at the time of signing the loan agreement up to departure for Canada; and 2) after arrival.

4.3.1 At Time of Signing

Finding: Prior to departure, many recipients are aware of the loan and the requirement to pay it back, but some do not know the loan details, notably, the amount of the loan.

As previously noted in Section 4.1, the loan is first discussed at the time of the selection interview with the refugee overseas. A review of program documentation showed that there are procedures and guidance in place for CIC staff to explain the loan (e.g., OP 17, the loan agreement form, and an operational bulletin), however, interviews with visa offices indicated that the only written information provided to the loan recipient to assist with their understanding is the loan agreement, which is not available in multiple languages and is a legal document and thus, not written in plain and accessible language. Moreover, as previously noted, visa officers spend very little time - typically between 1 and 5 minutes - explaining the loan.

Interviews with visa offices further revealed that the individual’s understanding of the loan is also limited by various factors such as their ability to absorb the information, their state of mind at the time (as they are people in need of protection), and the degree to which they would likely understand the relative value of the loan. In addition, the profile of loan recipients showed that many (53.5%) have no knowledge of either official language. These individuals must often rely on the assistance of an interpreter during the selection process. As well, questions are not always asked by refugees overseas, but when they are, interviewees noted they are general in nature, related to the loan amount and length of time to repay. Findings from the focus groups with refugees confirmed that they did not ask a lot of questions overseas, as there are time constraints, or they did not have questions at that stage. As a result, refugees have varying levels of understanding of the loan prior to departure for Canada.

Findings from the survey of loan recipients showed that 73.3% of those who received an overseas transportation and/or admissibility loan first learned that they were getting a loan prior to departure. Of those who did know, many indicated they did not know the amount of the loan (55.6%) or how much time they would have to repay it (57.4%). Moreover, some (24.4%) did not know who was included in the loan. The first source of information reported most frequently by those who first learned about the loan overseas was a government of Canada official overseas (56%), or an orientation session provided by the IOM prior to departure (29.6%). There were no significant differences between GARs and PSRs, who learned overseas, in how they first found out about the loan.

Similarly, the majority of focus group participants indicated that they knew about the loan prior to departure for Canada, but not the details. Many did not know the loan amount, that interest would be charged, or the terms and conditions of repayment until they were in Canada. A number indicated that they signed the loan agreement without understanding all of the details because they felt they had no choice, or they were rushed.

From a legal perspective, the most important piece of information to have prior to departure is the amount of the loan for which they are responsible to repay. Without this, there cannot be a “meeting of the minds”,Footnote 79 which is essential to the establishment of the loan as a legal contract. The evaluation found that the process and procedures in place for preparing and signing the loan agreement do not facilitate this understanding, as the final amount is not yet available. This is acknowledged on the reverse side of the loan agreement, which indicates that the amount on “the agreement represents the estimated principal amount of the loan… [the] actual principal amount of this loan, if different…will be made known to you after the transportation company honouring this warrant and Revenue Accounting, NHQ Finance, audits your loan account.”Footnote 80 In addition, the Directive on Receivables Management requires that “debtors are informed of their obligations under applicable acts and regulations”.

With this in mind, OP 17 indicates that the visa officer “must explain…that although the total amount of the transportation loan will not be written on the form before they are ready to travel to Canada, they will be responsible for repayment of the loan.” According to procedures, the IOM or a visa officer will return the signed client copy of the loan agreement, with the final total amount, to the recipient when they are ready to travel to Canada.Footnote 81 However, it is unclear how and exactly when this transaction occurs, or to what extent recipients are made aware of what they are receiving at that time.

4.3.2 After Arrival in Canada

Finding: At the time of receiving their first loan statement, the majority of recipients know they have a loan and need to repay it, but some do not fully understand the repayment requirements, such as the repayment start date.

Findings from the survey of loan recipients showed that 26.7% of those who received an overseas transportation and/or admissibility loan first learned that they were getting a loan after they arrived in Canada. Of these, 37.3% first learned about the loan through their loan statementFootnote 82 or letter, and 32.2% were informed through a settlement/immigrant serving organization in Canada. In addition, at the time of receiving the first loan statement, the vast majority of respondents indicated that they understood that they had been provided with a loan (96.6%), and that they would have to repay the loan (97.5%). However, somewhat fewer understood that they would be charged interest on the loan (70.3%), or that they could pay more than the minimum amount (75.3%), and only 56.3% understood that they would have to start repaying the loan 30 days after their arrival.

The lack of understanding of loan repayment requirements among loan recipients was also confirmed in the interviews with CIC officers in regional offices and collection officers at NHQ, as well as in interviews with program stakeholders. Furthermore, findings from the RAP SPO and SAH surveys indicated that they generally receive questions from refugees regarding the loan, and the most common questions are related to repayment (see Table 14).

| Types of Questions | RAP SPOs re: GARs (n=19) |

SAHs re: PSRs (n=14) |

Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Questions about the concept of a loan | 16 | 9 | 25 |

| Questions about interest and interest-free period | 19 | 10 | 29 |

| Questions about repayment | 19Footnote * | 14Footnote * | 33 |

| Questions about arrears | 16 | 11 | 27 |

| Questions about the consequences of not paying the loan | 17 | 9 | 26 |

| Other questions | 12 | 1 | 13 |

Source: SAH Survey and RAP SPO Survey

4.4 Role of CIC Collection Services

CIC has four main means to recover debts: direct collection action, recovery through set-off, use of private collection agencies, and legal action, such as the garnishment of wages.Footnote 83 CIC currently uses direct collection action (through the CIC Collection Services), garnishment of wages, and set-offs through CRA as its main methods of debt recovery. It was noted in interviews that collection agencies were used in the past, but were found not to be cost-effective.Footnote 84

Finding: CIC Collection Services are accessible in terms of language of service, hours of services and methods of payment. However, information on how to contact CIC Collection Services, and what services they offer, is not visible on the CIC public website, nor well communicated in CIC documentation provided to loan recipients.

Findings from the interviews, as well as the surveys of RAP SPOs and SAHs, did not indicate any significant issues with the accessibility of CIC Collection Services in terms of language of service, hours of service or methods of payment. Overall, respondents to the RAP SPO and SAH surveys generally agreed or strongly agreed that the hours of service are appropriate, that CIC offers enough ways to pay the loan, and CIC Collection Officers are generally able to answer questions.

The vast majority (95.1%) of respondents to the loan recipient survey, who had contacted CIC regarding their loan (either on their own or through someone on their behalf) agreed or strongly agreed that CIC offers enough ways to pay the loan. Furthermore, 94.9% of those who had used the 1-800 number to contact CIC on their own indicated that they were able to get answers to their questions, 92.2% indicated that they were able to contact CIC at a time of day that was convenient for them, and 89.4% indicated that it was easy to understand the person to whom they were talking. That said, only 38.7% of respondents had contacted CIC regarding their loan (either on their own or through someone on their behalf), with a lower percentage of PSR respondents (31.1%), compared to GAR respondents (43.5%) reporting this contact.

The focus groups highlighted the need for better promotion of the number to call for CIC Collection Services and the assistance they could provide. Very few focus group participants were aware that they could call CIC to make alternative arrangements and did not know the phone number to call or where to find it. Of those who mentioned CIC Collection Services, all indicated that their SPO or sponsor called on their behalf.

Observations during the evaluation revealed that the 1-800 number for CIC Collection Services is not well advertised. The number does not appear to be posted on the CIC website,Footnote 85 nor is there sufficient information online regarding the loan (see Section 4.2.1). Moreover, the information bulletins designed for refugees do not include this number.Footnote 86 The number can be found on the back of the loan agreement, but the loan form is a carbon-based document, which over time, likely becomes difficult to read. It can also be found on the monthly loan statement, but it is located on the part of the statement that is to be detached and returned with the recipient’s payment.

In sum, CIC Collection Services are generally operating well, and are accessible. However, many recipients are not accessing these services. When they do access the services, generally they do so using the toll-free 1-800 number. Evidence suggests that there is a lack of awareness of CIC Collection Services, brought on by a lack of promotion of the program and the 1-800 number on the part of CIC, which may be affecting the level of access.

4.5 Loan Repayment

Findings related to repayment are organized along three broad themes: starting to repay the loan; repayment within the loan term and interest-free period; and difficulties experienced in repaying and the use of alternative arrangements to alleviate these difficulties.

Context for this Section of the Report

The evaluation examined repayment for loan accounts issued between 2003 and 2012. A total of 48,446 loan accounts were found for the reporting period,Footnote 87 from which a random sample of 4,742 loan accounts was drawn for the analysis.Footnote 88 Based on the 2003-2012 sample of loan accounts, 69.4% had been paid in full and 10.3% were currently being paid at the time of data extraction for the evaluation, while 20.3% were not being (or had not been) paid (see Table 15).

| Payment Status as of December 31, 2013 | # | % |

|---|---|---|

| All accounts in sample | 4,742 | 100.0% |

| Paid in full | 3,290 | 69.4% |

| Being Paid | 490 | 10.3% |

| Not being (had not been) paid | 962 | 20.3% |

| Payment Status as of December 31, 2013 | # | % |

|---|---|---|

| Paid | 1,912 | 40.3% |

| Overpaid | 395 | 8.3% |

| Written off - small balance | 983 | 20.7% |

| Total - Paid in full | 3,290 | 69.4% |

| Payment Status as of December 31, 2013 | # | % |

|---|---|---|

| Paying | 490 | 10.3% |

| Total - Being Paid | 490 | 10.3% |

| Payment Status as of December 31, 2013 | # | % |

|---|---|---|

| Deferred | 17 | 0.4% |

| Delinquent | 600 | 12.7% |

| Tracing | 63 | 1.3% |

| Special (pending bankruptcies) | 4 | 0.1% |

| Bad Debt | 236 | 5.0% |

| Written off - reasons other than small balance | 42 | 0.9% |

| Total - Not being (had not been) paid | 962 | 20.3% |

Source: Sample of IFMS (SAP), IPAR and Archived Microfiche Loan Accounts (2003-2012).

The subsequent repayment analysis focuses on paid loan accounts, using the sample of loan accounts described above.Footnote 89

For some repayment outcomes, comparisons by socio-demographic characteristics were conducted on a sub-population of loans issued between 2008 and 2012. As well, a comparison between the results of the evaluation and a repayment analysis undertaken by the policy program area of CIC in 2012 was undertaken.Footnote 90

4.5.1 Starting to Repay the Loan

Finding: While all recipients are required to start repaying their loan 30 days after arrival, evidence indicates that 68% do not start repaying until 6 months or more after arrival.

Regulations stipulate that loan repayment is to start 30 days after the person for whose benefit the loan was made arrives in Canada (for a transportation or an admissibility loan), or 30 days after the person benefiting from the loan has been issued the loan (for an assistance loan).Footnote 91

Based on the 2003-2012 sample of loan accounts, almost no one started repaying their loan within 30 days, and 68% of recipients did not start repaying their loan until six months or more after arrival (see Table 16). In addition, 29.8% did not start repaying their loan until more than 12 months after arrival.

| Length of time after term start | Percentage of loan accounts |

|---|---|

| Within 30 days | 0.0% |

| Between 1 and 3 months | 3.7% |

| Between 3 and 6 months | 28.2% |

| Between 6 and 12 months | 38.2% |

| More than 12 months | 29.8% |

Note: n=4,393. Some of the sampled accounts are not included in this analysis as they were missing pertinent information, notably first payment dates. Percentages are rounded and do not add up to 100%.

Source: Sample of IFMS (SAP), IPAR and Archived Microfiche loan accounts (2003-2012).

Information from other loans programs suggests that the 30-day requirement to start repayment is not consistent with standard practices. The travel loans provided to refugees resettling in the United States allow recipients to start repayment six months after arrival.Footnote 92 Similarly, the Canada Student Loans Program does not require recipients to start loan repayment until six months after the completion of their studies.Footnote 93

Finding: It takes up to 4 months for CIC to set up a loan account and issue the first loan statement, at which point the recipient’s account can be in arrears.

The evaluation found that the first loan statement is used as a mechanism to initiate and facilitate the repayment process, but is not sent to the recipient until the loan account is set up. It is widely acknowledged in program documents, including the CIC Collection Services Manual,Footnote 94 OP 17Footnote 95 and the loan agreement itself,Footnote 96 that it takes longer than 30 days for CIC to establish a loan account in the department’s financial system.

Loan recipients are expected to start making payments 30 days after arrival, even though the first statement is not sent out until their loan account is established.Footnote 97 Given the link between setting up the loan account and receipt of the first statement, stakeholders were asked to estimate when the first loan statement is typically received. Respondents to the RAP SPO and SAH surveys and focus group participants both estimated the first loan statement is received, on average, about 3 months after arrival.

As explained in Section 4.3, CIC informs loan recipients regarding payment requirements. However, the requirement to start paying within 30 days is not emphasized, unless the recipient makes an inquiry about their loan before receiving their first statement. If the loan recipient inquires about their loan before receiving their first monthly statement, the CIC Collection Services Manual instructs officers to inform the recipient that they can pay by cheque, and that as soon as the account is created, they will receive a statement and will be able to start making payments at the bank or online.Footnote 98 Information bulletins for GARs and PSRs are posted on the CIC website (in multiple languages) with some information about the loan and the requirement to start repayment within 30 days of arrival, however, these bulletinsFootnote 99 were only recently introduced (May 2014) and it is too early to assess the extent to which they are being accessed and used by loan recipients.

Thus, while information exists, the 30-day requirement to start repaying is not always well communicated or understood in a timely manner. The misaligned timing between the dissemination of the first statement and the deadline to start repayment is problematic, inadvertently setting up recipients to be late in the repayment of their loan, i.e. in arrearsFootnote 100 – owing money from earlier missed payments.Footnote 101 Even if the requirement was to be better communicated, it is still confounded by the delay in setting up the loan account and the dissemination of the loan statement, which are fundamental to formally initiating and facilitating the repayment process.Footnote 102

4.5.2 Repayment within the Loan Term

Finding: Overall, approximately two-thirds of loan accounts analyzed were repaid within the loan term. For loans of $1,200 or less, the average length of time taken by recipients to repay surpassed the 12-month timeframe provided.

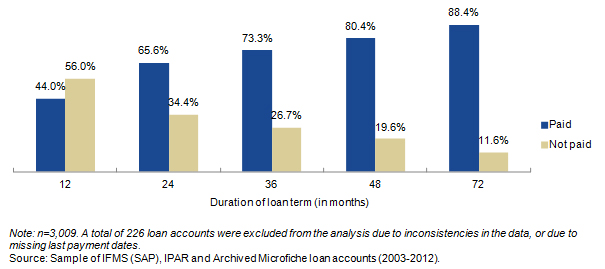

The analysis of administrative data revealed that, overall, 67.7% of the 2003-2012 sampled accounts were repaid within the loan term. The majority of loan recipients were able to repay within the loan term, with the exception of those with a 12-month term. In these cases, less than half (44%) were able to repay within the loan term (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Percentage of Paid Loan Accounts Repaid Within the Loan Term by Duration (2003-2012)

Figure 1: Percentage of Paid Loan Accounts Repaid Within the Loan Term by Duration (2003-2012) - Table

| Duration of loan term (in months) | 12 | 24 | 36 | 48 | 72 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Paid | 44.0% | 65.6% | 73.3% | 80.4% | 88.4% |

| Not Paid | 56.0% | 34.4% | 26.7% | 19.6% | 11.6% |

Note: n=3,009. p< .001 A total of 226 loan accounts were excluded from the analysis due to inconsistencies in the data, or due to missing last payment dates.

Source: Sample of IFMS (SAP), IPAR and Archived Microfiche loan accounts (2003-2012).

As previously discussed, a large percentage of recipients did not begin repayment until six months after the start of their loan term. As a consequence of this late start, it may take some time to catch up in their payments. It appears that recipients with a longer term have more time to catch up.

The analysis shows that a number of recipients were unable to repay the 12-month loan within the loan term even though the loan size is relatively small. In contrast, most recipients with a 72-month loan were able to repay within the loan term, even though the amount of these loans is considerably larger (over $4,800) relative to the 12-month loans (up to $1,200).

Months Required to Repay the Loan

The evaluation found that average repayment time varied by duration of the loan term, with smaller loans taking fewer months to repay than larger loans. Furthermore, recipients who repaid their loan within the loan term did so much sooner than required by the schedule, while those who did not repay within the loan term took almost an additional year to repay (see Table 17).

| Loan Term | Average months | n |

|---|---|---|

| 12 months | 17.4 | 494 |

| 24 months | 23.9 | 1,408 |

| 36 months | 32.0 | 463 |

| 48 months | 37.8 | 301 |

| 72 months | 46.8 | 380 |

| Overall | 28.3 | 3,046 |

Note: The analysis of repayment time by incidence of repayment within the loan term excludes some accounts due to inconsistencies in the data. Therefore, the total number of accounts is not equal to 3,046 for this part of the analysis.

Source: Sample of IFMS (SAP), IPAR and Archived Microfiche loan accounts (2003-2012).

| Yes | No | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Loan Term | Average number of months | n | Average number of months | n |

| 12 months | 9.4 | 214 | 23.6 | 271 |

| 24 months | 17.2 | 908 | 36.2 | 476 |

| 36 months | 26.4 | 335 | 46.9 | 122 |

| 48 months | 32.7 | 242 | 58.8 | 59 |

| 72 months | 42.1 | 336 | 82.3 | 44 |

| Overall | 23.8 | 2,035 | 37.5 | 972 |

Note: The analysis of repayment time by incidence of repayment within the loan term excludes some accounts due to inconsistencies in the data. Therefore, the total number of accounts is not equal to 3,046 for this part of the analysis.

Source: Sample of IFMS (SAP), IPAR and Archived Microfiche loan accounts (2003-2012).

Repayment Rate

The evaluation examined repayment time in relation to the amount of time needed for the Immigration Loan Program to reach a target of 90% of loan accounts repaid, corresponding to the loan recovery rate commonly used by the department.Footnote 103 The analysis looked at this rate by loan term, and found that, in general, more time was needed than allowed by the loan terms to reach a repayment rate of 90%. However, the variance between the duration of the loan term and time needed to repay decreased as the loan term increased.

| Loan Term | n | Number of months within which 90% of loan accounts were repaid |

|---|---|---|

| 12 months | 494 | 31.3 |

| 24 months | 1,408 | 38.3 |

| 36 months | 463 | 45.5 |

| 48 months | 301 | 54.8 |

| 72 months | 380 | 74.5 |

Source: Sample of IFMS (SAP), IPAR and Archived Microfiche loan accounts (2003-2012).

4.5.3 Repayment within the Interest-Free Period

Finding: While overall 59% of accounts analyzed were repaid within the interest-free period, less than half of the accounts with a 12-month or 72-month term were repaid within the interest-free period.

The Immigration Loan Program provides an interest-free period which may vary from one to three years, depending on the amount of the loan.Footnote 104 The analysis of administrative data found that, overall, 58.6% of the 2003-2012 sampled accounts were repaid within the interest-free period, and duration of the loan term had a significant impact on the incidence of repayment within the interest-free timeframe (see Figure 2).

Figure 2: Percentage of Paid Loan Accounts Repaid within Interest-free Period by Duration of Loan Term (2003-2012)

Figure 2: Percentage of Paid Loan Accounts Repaid within Interest-free Period by Duration of Loan Term (2003-2012) - Table

| Interest-free period = loan term | Interest-free period = 36 months | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Duration of loan term (in months) | 12 | 24 | 36 | 48 | 72 |

| Paid | 44.0% | 65.4% | 73.3% | 51.4% | 40.1% |

| Not Paid | 56.0% | 34.6% | 26.7% | 48.6% | 59.9% |

Note: n=3,001. p< .001. A total of 234 loan accounts were excluded from the analysis due to inconsistencies in the data, or due to missing last payment dates.

Source: Sample of IFMS (SAP), IPAR and Archived Microfiche loan accounts (2003-2012).

Program documents stipulate that the interest-free period for loans was intended to prevent undue hardship being placed on loan recipients during their initial settlement period.Footnote 105 The interest-free period, however, can be as little as one year, which is much less than the timeframe of three to five years identified in program documents as a reasonable timeframe after which the individual should no longer rely on social assistance for food or shelter.Footnote 106

In addition, findings from the focus groups revealed that, for some, the payment of interest is not allowed for religious reasons. For these individuals, the loan term must equal the interest-free period, resulting in the need to make higher monthly payments over a shorter period than what is normally suggested, negating the intent to prevent undue hardship for this particular group. This is further complicated by the fact that the loan statement provided to recipients includes a minimum monthly payment amount, which is calculated according to the amount borrowed by dividing the total loan amount by the number of months in the corresponding loan term.Footnote 107 As a result, if the loan recipient makes only the minimum monthly payment for the 48- and 72-month loans, where the loan term is longer than the interest-free period, they will not be able to avoid paying interest on the loan.

The Canada Student Loans Program (CSLP) also charges interest, with the Government of Canada paying the interest on student loans while borrowers are in school,Footnote 108 while the travel loans offered to refugees resettled in the US are interest-free.Footnote 109

4.5.4 Difficulty Repaying and Use of Alternative Arrangements

Finding: Having employment facilitates the ability to repay the loan. However, GARs and PSRs have a low incidence of employment income and often rely on income support (particularly GARs) in the first year after landing.

As previously discussed, to approve a loan, the CIC designated officer must assess the applicant’s potential ability to repay a loan. The key consideration in this assessment is the applicant’s income potential, which is largely predicated on getting a job once in Canada.Footnote 110

The survey of loan recipients found that a little over half of loan recipients surveyed (53.4%) were employed while paying back their loan. This percentage was significantly higher for PSR loan recipients (75.7%) compared to GAR loan recipients (39.7%).

Correspondingly, 59.4% of loan recipients surveyed indicated that they had to use their income support or social assistance to pay their loan. As expected, this percentage was significantly higher for GAR loan recipients (76.3%) compared to PSR loan recipients (31.9%). While this difference can be attributed to the fact that GARs typically receive income support through RAP during their first year in Canada, the percentage of PSRs relying on this assistance to help repay the loan is noteworthy. PSRs receive financial support from their sponsors, and do not typically have access to social assistance during their first year in Canada.Footnote 111

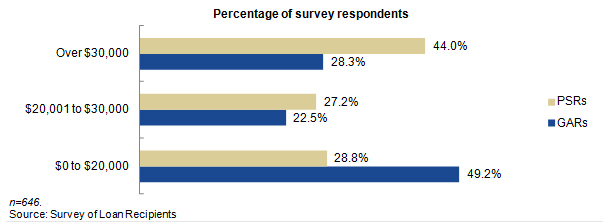

When asked to estimate their total household annual income (before taxes) from all sources, 41.3% of loan recipients surveyed indicated a household income of $20,000 or less at the time of the survey. Although higher for GAR loan recipients (49.2%) compared to PSR loan recipients (28.8%), the percentage of loan recipients with a low income was considerable for both groups (Figure 3). Of note, 44.2% of those with a household income of $0-$20,000 were still paying off their loan at the time of the survey.

Figure 3: Estimated Household Income (before taxes) of Loan Recipients by Immigration Category

Figure 3: Estimated Household Income (before taxes) of Loan Recipients by Immigration Category (2003-2012) - Table

| Estimated Household Income (before taxes) | Percentage of survey respondents - GARs | Percentage of survey respondents - PSRs |

|---|---|---|

| $0 to $20,000 | 49.2% | 28.8% |

| $20,001 to $30,000 | 22.5% | 27.2% |

| Over $30,000 | 28.3% | 44.0% |

n=646. p< .001

Source: Survey of Loan Recipients.

A little over three quarters of loan recipients reporting a household income of $20,000 or less indicated a household size of three or more people – 45.3% indicated a household of three to five people, and 32.2% indicated a household of six or more people. In comparison, the low income cut-off (1992 base) before tax in 2013 for a family of three people, living in a community of between 30,000 and 99,999 inhabitants was $31,256.Footnote 112 As the low income cut-off represents the income threshold below which a family will likely devote a larger share of its income on the necessities of food, shelter and clothing than the average family, it would appear that the resources available to these recipients to help with repayment of a loan would likely be limited.

Incidence of Employment Earnings

The percentage of GAR familiesFootnote 113 with employment earnings in the year of landing was quite low (16.0%). One year after landing in Canada, there was a significant increase in the percentage of GAR families who declared employment earnings (47.4%), which continued until five years after landing, at which time it reached a plateau. About 70.0% of GAR families declared employment earnings five to ten years after landing.

In comparison, 61.2% of PSR families had employment earnings in the year of landing. One year after landing, the incidence of employment among PSR families was about 80%, and remained relatively stable during the ten years following landing at around 75% to 80% (see Table 19).Footnote 114

| Immigration Category | Years Since Landing | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

| GAR families | 16.0 | 47.4 | 58.3 | 65.2 | 68.3 | 70.0 | 70.4 | 69.9 | 70.8 | 72.1 | 72.6 |

| PSR families | 61.2 | 79.9 | 79.4 | 80.1 | 80.7 | 80.6 | 79.9 | 78.0 | 77.1 | 77.0 | 74.8 |

Source: IMDB.

Incidence of Income Support and Social Assistance

Most GAR families received social assistance in the year of landing, which can be attributed to their receipt of RAP income support. In spite of the increase in the incidence of employment, the incidence of social assistanceFootnote 115 remained high one year after landing, indicating that a number of GAR families rely on both sources of income during their first year in Canada. The percentage of GAR families receiving social assistance declined sharply two years after landing, and then more steadily over time; however, by ten years after landing, it still represented about a third of GAR families (33.1%) (see Table 20).

As expected, the percentage of PSR families who received social assistance in their year of landing was very low (2.9%), as PSR families receive financial support from their sponsor during their first year in Canada. However, one year after landing, the incidence of social assistance among PSR families increased sharply, to 22.8%. While less than the incidence among GAR families, the incidence among PSR families is still noteworthy, reaching a plateau of 22% to 24% five to ten years after landing.Footnote 116

| Immigration Category | Years Since Landing | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

| GAR families | 94.8 | 90.4 | 67.7 | 57.2 | 49.5 | 43.9 | 40.6 | 39.0 | 37.1 | 35.2 | 33.1 |

| PSR families | 2.9 | 22.8 | 28.0 | 27.2 | 25.3 | 24.3 | 23.8 | 23.9 | 22.6 | 22.4 | 23.7 |

Source: IMDB.

Employment Earnings

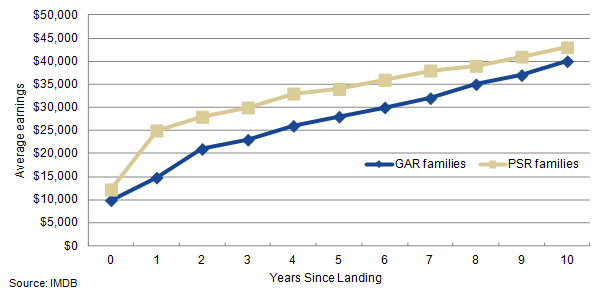

Average earnings for GAR families who had employment in their year of landing were low ($9,900), but increased over time, reaching an average of $40,000 ten years after landing (see Figure 4).

Average earnings of PSR families, though higher than those for GAR families with employment, were relatively low ($12,200) in their year of landing. Ten years after landing, their earnings reached an average of $43,000.

Figure 4: Average Earnings of GAR and PSR Families Who Declared Employment by Years since Landing

Figure 4: Average Earnings of GAR and PSR Families Who Declared Employment by Years since Landing - Table

| Years Since Landing | 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GAR families | $9,900 | $14,800 | $21,000 | $23,000 | $26,000 | $28,000 | $30,000 | $32,000 | $35,000 | $37,000 | $40,000 |

| PSR families | $12,200 | $25,000 | $28,000 | $30,000 | $33,000 | $34,000 | $36,000 | $38,000 | $39,000 | $41,000 | $43,000 |

Source: IMDB.

Finding: Some loan recipients experience difficulties in repaying the loan. A greater percentage of GARs, recipients with larger loans and those with a lower annual household income experienced difficulty with loan repayment.

Respondents to the loan recipient survey were evenly distributed in their responses to the level of difficulty they experienced in paying back the loan – 31.7% indicated that it was very easy/easy; 36.8% indicated that it was neither easy nor difficult; and 31.5% indicated that it was difficult/very difficult. There were, however, significant differences in these responses by immigration category, size of loan, employment status and income level, with a greater percentage of GARs, recipients with larger loans, those not employed, and those with less income indicating difficulty with repayment (see Table 21).

| Characteristics | Very easy/ easy |

Neither easy nor difficult |

Difficult/ very difficult |

|---|---|---|---|

| GARs | 21.7% | 38.6% | 39.7% |

| PSRs | 47.9% | 33.9% | 18.2% |

| Characteristics | Very easy/ easy |

Neither easy nor difficult |

Difficult/ very difficult |

|---|---|---|---|

| $1,200 or less | 57.5% | 22.5% | 20.0% |

| >$1,200 up to $2,400 | 45.3% | 32.8% | 21.9% |

| >$2,400 up to $3,600 | 27.4% | 45.3% | 27.4% |

| >$3,600 up to $4,800 | 30.9% | 38.3% | 30.9% |

| >$4,800 | 20.9% | 38.2% | 40.8% |

| Characteristics | Very easy/ easy |

Neither easy nor difficult |

Difficult/ very difficult |

|---|---|---|---|

| Not employed | 21.9% | 36.5% | 41.5% |

| Employed | 40.4% | 37.1% | 22.5% |

| Characteristics | Very easy/ easy |

Neither easy nor difficult |

Difficult/ very difficult |

|---|---|---|---|

| $0 to $20,000 | 32.2% | 42.4% | 49.7% |

| $20,001 to $30,000 | 25.9% | 23.0% | 23.9% |

| Over $30,000 | 42.0% | 34.6% | 26.4% |

Source: Survey of Loan Recipients.

The review of administrative data revealed that, based on the 2008-2012 sub-population of loans, 31.2% of loan accounts had demonstrated signs of difficulty,Footnote 117 and 22% of accounts had a CRA set-off.

A number of factors affecting difficulty in repaying were also reported in the RAP SPO and SAH surveys. Most RAP SPO and many SAH respondents most frequently reported a lack of employment, transferable skills and job readiness as contributing to difficulty with repayment and the associated burden of the loan. In explaining how this factorFootnote 118 contributes, generally RAP SPO and SAH respondents highlighted challenges in relation to securing adequate employment and earning sufficient income in order to support their families and repay the loan. They also discussed how other factors, such as disabilities, issues related to language, literacy and education, as well as the trauma of their refugee experience limit their ability to repay the loan.

The review of academic literature found that limited financial resources places a strain on the individual, which is further exacerbated by loan repayment. It also confirmed the need for assistance for PSRs in order to repay (either through providing funds, or advice and guidance on repayment), as well as cultural/religious issues or social stigma associated with debt that adds to the burden to repay.

Difficulties repaying the loan were mentioned in all focus groups. Various reasons were given for these difficulties, such as lack of English skills, no work experience in Canada, difficulties finding a job, learning new culture/financial system, and health problems. GARs mentioned that their income support (through RAP) was not sufficient to pay for basic needs, as well as the loan, and that employment income along with the income support would be sufficient to pay for all costs. PSRs indicated that the main difficulty in repayment for them was not being able to find a job.

In sum, some recipients have difficulty repaying their loans, and a number do not repay their loans within the loan term or interest-free period. Recipients of the Immigration Loan Program are mainly refugees, and a number of refugees, especially GARs, are not employed for the first few years following their arrival. GARs, in particular, rely heavily on income support benefits during their first year in Canada. A little under half of GAR and PSR loan recipients surveyed (46.6%) indicated they did not have a job while paying back their loan, but having a job and higher income were shown to affect loan repayment.

Finding: Many loan recipients are not aware of the option to make alternative arrangements to repay their loan. While alternative loan arrangements, such as deferred payments, make it somewhat easier for recipients to pay back their loan in the short term, these arrangements do not change the interest-free period.

The IRPR allows CIC to negotiate alternative repayment arrangements with recipients who are having difficulty. It specifies that if repaying a loan as per the requirements would cause the recipient financial hardship (by reason of their income, assets and liabilities), the CIC Collections Officer may defer the start of repayment of the loan, defer payments on the loan, vary the amount of payments, or extend the repayment period up to two years.Footnote 119

Many GARs and PSRs reported not knowing that alternative arrangements could be made – 49.6% of respondents to the loan recipient survey were not aware that CIC sometimes allows people to re-negotiate their loan in this way, and a greater percentage of PSRs (56.5%) were unaware, compared to GARs (45.4%). Similarly, as noted earlier, many GARs and PSRs in the focus groups were unaware that they could call CIC to make alternative arrangements. Findings further showed that only 21.6% of loan recipients surveyed had made arrangements with CIC to change the amount of their monthly loan payment or the time when they would have to pay. A greater percentage of GARs (27.1%) had made these arrangements, compared to PSRs (12.8%).

Of those survey respondents who had made alternative arrangements, the majority (91%) indicated that the arrangements made to change the amount or schedule related to loan repayment made it “at least somewhat easier” to pay back the loan (with 51% indicating that it made it “quite a bit easier”). In addition, many respondents to the RAP SPO survey who assisted GARs with the renegotiation process indicated that options were presented to find a payment plan/schedule for the loan that GARs could manage and that the changes that were made during the re-negotiation made it easier for GARs to pay the loan (though a few indicated that they did not know).

While there is some indication that arrangements make it somewhat easier to repay the loan, it was also noted in the interviews that arrangement to defer payment does not completely eliminate the problem. While repayment can be deferred, it doesn’t change the interest-free period; interest will accrue as per the IRPR.Footnote 120

In comparison, the Canada Student Loans Program (CSLP) provides a variety of assistance to borrowers who are having difficulties meeting their repayment obligations. Under the CSLP Loan Repayment Assistance Plan, borrowers experiencing financial hardship in repaying their loans are eligible for up to 54 months of interest relief during the lifetime of their loans, depending upon the circumstances. As well, borrowers experiencing financial hardship can ask for revision of the terms of repayment. Borrowers still experiencing financial difficulties after five years of leaving full-time or part-time study, and who have exhausted all interest relief, can apply to have their loan principal reduced, and can receive up to three reductions on their loan principal during their lifetime, for a total of up to $26,000 (depending on their financial circumstances)Footnote 121.

In sum, more GARs than PSRs are taking advantage of the alternative arrangements offered by CIC to alleviate the burden of repayment. There appears to be greater awareness among GARs of the possibility of re-negotiation, as well as opportunity for them to receive assistance from RAP SPOs for this purpose. In the end, however, the alternative arrangements are making it somewhat easier to repay the loan for some loan recipients. Making smaller payments, however, may increase the repayment time for the loan, thereby extending the period for potential hardship. In addition, given that the alternative arrangements do not prevent the accrual of interest at a later time, some loan recipients will have to pay more than the original loan amount.

4.6 Impact on Settlement

The evaluation looked at the overall impact of the loan on the ability to settle as well as the impact on the use of settlement services.

4.6.1 Impact on Ability to Settle

Finding: For some loan recipients, requirements to repay an immigration loan are a source of stress and create additional challenges, such as the ability to pay for basic necessities.

Findings from the survey of loan recipients showed that while most GARs and PSRs were proud that they were able to repay their loan (95.3%) and felt that they better understood the Canadian financial system as a result of the loan (88.7%), a number of recipients had experienced some negative impacts on their settlement as a result of loan repayment:

- 53.9% indicated that paying back the loan made it difficult to pay for basic necessities like food, clothing and housing;

- 55.0% indicated that after paying for basic necessities, paying back the loan took a large portion of their remaining resources; and

- 51.1% indicated that paying back the loan was stressful for them and/or their family.

The survey also revealed that a greater percentage of GARs than PSRs had experienced stress (58.9% vs. 38.6%), difficulty in paying for basics such as food, clothing and housing (63.6% vs. 38.0%), and difficulty affording to participate in community-related activities (56.1% vs. 32.3%) as a result of having to repay the loan.

A greater percentage of survey respondents with larger loans had also experienced these negative settlement-related impacts. Similarly those who were unemployed at the time of repayment and those with a lower household income had experienced stress, difficulty meeting their basic needs, and difficulty affording to participate in community-related activities as a result of loan repayment (see Appendix D for detailed figures).

These findings were also reflected in the RAP SPO and SAH surveys (see Appendix D for detailed table). Also of note, a number of RAP SPO and SAH respondents indicated that having to repay the loan makes loan recipients feel the need to get into the labour market more quickly. Findings from the interviews highlighted similar impacts on loan recipients, such as feeling rushed to get a job and having to accept a minimum wage job.

Respondents to the loan recipient survey were asked about their experiences related to employment while paying back the loan. As noted earlier, 53.4% of respondents reported having a job while repaying their loan. Of these recipients, 53.7% indicated having taken on a job that did not fit their skills and experience, with a greater percentage of GARs (60.7%) than PSRs (47.8%) reporting this. In addition, 36.3% of those with a job indicated having worked more than one job, with no significant differences between GARs and PSRs.

Having to take a subsistence job in order to pay back the loan was also mentioned in the focus groups with GARs and PSRs, as well as difficulty in finding a job, lack of job opportunities, lack of language skills and difficulty with foreign credential recognition, which in turn made it more difficult to repay the loan. Some PSRs, in particular, did not feel they had sufficient assistance in finding a job, and thought it would be easier to find a job.

Many focus group participants noted the need to make sacrifices (e.g. basic needs) in order to pay back the loan. Some GARs, in particular, were concerned about how they would cope with all the daily living expenses, including the loan, once their income support would end and some talked about using the Child Tax Benefit to pay the loan. While having a job somewhat alleviated the burden of the loan for some focus group participants, they indicated that they still felt stress as a result of the loan.

4.6.2 Impact on Use of Settlement Services

CIC funds services that help newcomers settle and adapt to life in Canada. These settlement services are intended to assist immigrants and refugees to overcome barriers specific to the newcomer experience (such as a lack of official language skills and limited knowledge of Canada) so that they can participate in social, cultural, civic and economic life in Canada.Footnote 122

Finding: While the majority of loan recipients accessed settlement services, the need to have employment income to facilitate loan repayment makes it difficult for some to take full advantage of these services, particularly language training.

An analysis of administrative data on the use of CIC funded settlement services,Footnote 123 covering the period from 2008 to 2012 revealed that 93.5% of GAR and PSR loan recipients had used at least one settlement service (see Table 22).Footnote 124

| Immigration category | Yes | No |

|---|---|---|

| GAR | 97.6% | 2.4% |

| PSR | 88.1% | 11.9% |

| Gender | Yes | No |

|---|---|---|

| Male | 92.6% | 7.4% |

| Female | 95.0% | 5.0% |

| Official language capacity | Yes | No |

|---|---|---|

| None | 95.0% | 5.0% |

| One or both | 91.7% | 8.3% |

n=16,016.

Source: CIC IFMS (SAP) loan accounts (2008-2012), FOSS/GCMS, Immigration Contribution Accountability Measurement System (iCAMS) and Immigration Contribution Agreement Reporting Environment (iCARE) data.

While access appears to be high overall, results from the survey of loan recipients suggests that recipients are having difficulties in taking advantage of these services. Just under half of respondents to the loan recipient survey (47.8%) indicated that as a result of working to pay back their loan, it was more difficult to find the time to use services to help them adapt to living in Canada (i.e. settlement services). In addition, 23.8% of loan recipients surveyed indicated having put off or quit language training in order to pay back their loan, and 22% indicated having put off or quit school (other than language training) in order to pay back their loan. Similarly, many focus group participants indicated that it was difficult to take advantage of language training opportunities (full-time or part-time) as they were working. Others were taking language training while actively trying to find a job.

Findings from the interviews were generally mixed, with some interviewees feeling that the loan has an impact on access to settlement services and others feeling that there is no impact. However, most respondents to the RAP SPO and SAH surveys indicated that GARs and PSRs have to put off at least sometimesFootnote 125 accessing settlement services (including language training) to work or look for work in order to pay back the loan. Similarly, most RAP SPO and SAH respondents indicated that GARs and PSRs have to put off at least sometimes going to school or to other training for this reason. Some RAP SPO and SAH survey respondents also felt that GARs and PSRs are focused too much on paying back the loan during their first year in Canada, rather than on their settlement needs (see Appendix D).

In sum, the immigration loan is having negative impacts related to settlement for some GARs and PSRs, and represents an additional burden to an already challenging integration process. Having a loan to repay makes it difficult for some refugees to meet their basic household needs and participate in their communities. It also causes stress for a number of refugees, and impacts on their ability to access learning opportunities through school, training and settlement services designed to help them adapt to life in Canada and overcome obstacles inherent to the newcomer experience.