Evaluation of the Reviews and Interventions Pilot Project

3. Evaluation Findings

This section presents the findings of the evaluation, organized by the two evaluation issues of performance and relevance.

3.1 Performance

3.1.1 Implementation of the Pilot

The Pilot was assessed in terms of whether it was implemented as intended, the nature of any challenges experienced with implementation, and the level of coordination and communication within CIC and between CIC and partners.

Planned Versus Actual Implementation

Finding: The Pilot was implemented as intended, in that a function was put in place for CIC to be able to review and intervene on cases where it identified concerns with respect to credibility and program integrity. Modifications were made to timing, budget, scope; which differed from the original implementation plan.

Limited detailed documentation related to the implementation of the Pilot was available and thus, the assessment of this aspect was based on foundational documents and information gathered from interviews and focus groups. The objective of the Pilot was to put in place a function for CIC to be able to review and intervene on cases of credibility and program integrity. CIC was successful in achieving this objective and in putting in place the infrastructure to be able to conduct reviews and interventions. The evaluation found that there were some modifications to the original plan, including:

- Launch and duration: The launch of the Pilot was delayed by one year (to October, 2012), due to the delay of the coming-into-force of the Protecting Canada's Immigration System Act. Additionally, the duration of the Pilot was extended by one year to March, 2016.

- Process: To allow for a review of all claims and to avoid duplication, a joint triage process was put in place between CIC and the CBSA. In addition, while all information exchange with the CBSA and the IRB was intended to be done electronically; this was only implemented between CIC and the CBSA, and exchanges with the IRB remain paper-based.

- Scope: Due to a lower number of claims than expected, the scope of the Pilot was expanded to include the review of legacy cases (i.e., claims made pre-coming-into-force) and the conduct of trend analysis. In addition, to increase program integrity, the scope was expanded to include the review of all positive RPD decisions on DCO claims, the review of certain case types for recommendation for judicial review at the Federal Court, and refugee redeterminations.

- Organizational Structure: It was originally intended that all three managers would be located in the Toronto office. However, due to an increase in the number of SIOs in the Montreal office, it was decided that one manager would be located in that office. In addition, due to the efforts required to implement the paper-based process with the IRB, more clerical support was hired than originally envisioned. The classification levels of the RIAs and SIOs were also lower than originally intended, which interviewees noted resulted in lower costs for the Pilot.Footnote 14

- Budget and FTEs: In addition, based on the estimated expenditures provided by CIC's Financial Management Branch, spending for the Pilot was $3.6 million less than planned and fewer FTEs were engaged than planned. These reductions were related to the high turn over of staff, which left positions vacant for periods of time, as well as the lower classification of RIAs and SIOs.

These modifications resulted in a few challenges, mainly related to staffing and the need to manage the paper-based process with the IRB. These and other challenges with respect to the implementation of the R&I Pilot are summarized below.

Implementation Challenges

Finding: The biggest implementation challenges faced by the Pilot have been high staff turnover, the paper-based process with the IRB, a lack of training and tools for R&I staff, and coordination issues between CIC and the CBSA.

Interviewees and focus group participants were asked about the key challenges experienced in implementing the Pilot. CIC identified the following key challenges:

- Staffing: Some staffing processes had already been completed when the delay of the Pilot was announced, which resulted in the loss of some staff and the need for other staff to find temporary assignments. In addition, due to the temporary nature of the Pilot, there is a high rate of staff turnover, with respondents noting that the R&I offices have always been "in staffing and training mode".

- Paper-based process with the IRB: As already noted, the use of a paper-based system to exchange information between CIC and the IRB has resulted in increased workload and the need for the hiring of additional clerical staff.

- Training and tools: R&I staff noted a lack of training, particularly with respect to RAD processesFootnote 15, document analysis, and CIC information systems such as FOSS, GCMS, and NCMSFootnote 16. They also noted gaps in the availability of tools, such as standard operating procedures for SIOs and RIAs, document comparison software, and facial recognition software. In addition, R&I staff are dependent on the CBSA for some information (e.g., document analysis), yet no formal channels are in place to obtain this information (see the section below for more on this).

- R&I framework: From a policy perspective, the lack of a clear framework to guide the interventions process was identified as a key challenge. While there is a standard operating procedure for the joint triage process, which provides triggers that may be grounds for an intervention, it was noted that there is little guidance currently available on when an intervention should be made, the process by which information should be gathered, and the sources of information that could be used to support an intervention. As a result, it was noted by a few interviewees that the scope for interventions may be too wide and needs to be better defined and adjusted.

- International partner information requests: Interviewees indicated that the CIC reviews and interventions function is only able to place a limited number of requests for information from Five Country Conference partners and Interpol. These requests provide information to help ascertain any potential identity issues. This creates a challenge in appropriately prioritizing requests for information from international partners.

- Reviews and interventions data: Interviewees identified a number of data issues for the R&I Pilot, namely the fact that several data sources are used to report on the Pilot (i.e., OPMB, MACAD, RCC), but these different sources do not contain the same information (as noted in the section on Limitations). This has resulted in inconsistencies across CIC with respect to the data are being used to monitor and report on the performance of the Pilot.

Some of these challenges, particularly those related to the availability of training and tools, the lack of an R&I framework, and data inconsistencies, may be reflective of the fact that the Pilot was in the early stages of implementation at the time of the evaluation.

Communication and Coordination

Finding: Mechanisms for communication and coordination at senior levels within the regions and between the R&I offices and CIC are in place, and are viewed as effective by interviewees. However there are limited formal communication and coordination mechanisms in place between CIC and the CBSA.

Within CIC

The evaluation found that mechanisms were put in place at all levels within CIC to support the coordination and communication for the Pilot, including:

- At the senior level, coordination for the Pilot was done via the committees that were put in place for the ICAS reforms (e.g., Senior Review Board). Interviewees noted that these mechanisms worked well and that there was a less of a need for these committees to meet post-implementation.

- At the regional level, the Regional Management Committee of OntarioFootnote 17 was noted as the senior-level forum to discuss the Pilot. The Regional Director General also discusses the Pilot with the Associate Assistant Deputy Minister of Operations as required and has regular bi-lateral meetings with the R&I Director to discuss the operation of the Pilot. Within the R&I offices, the Director has weekly manager meetings and there are regular staff meeting. The R&I offices also contact other areas within CIC (e.g., intake offices, missions, Legal), as needed.

- In terms of coordination between the Region and Headquarters, the R&I offices and OMC have regular phone calls, in-person meetings two times per year, and contact each other as needed (e.g., via an OMC e-mail address). There is also a working group that meets on a quarterly basis to discuss data-related issues.

Interviewees noted that these mechanisms were very effective and that working relationships within CIC are very good, with just a few suggestions for improvements. A few interviewees expressed a desire to have more formal communication and coordination mechanisms put in place with other areas within CIC, such as the visa offices and the refugee intake unit, as it is done fairly informally at present. A few also noted the need to have better communication and coordination on data issues to ensure that data are analyzed and reported consistently.

Between CIC and Partners

The Operational and Implementation Issues Working Group, chaired by CIC, was described by interviewees as a successful mechanism for CIC, the CBSA, and the IRB to discuss the implementation of the Pilot and any related issues.Footnote 18 In addition, quarterly meetings are held between the CIC Ontario Regional Director General and the Regional Director Generals of the three CBSA Ontario Regions and updates on R&I are routinely provided at these meetings. At the working level, CIC and CBSA interviewees and CIC focus group participants generally reported good working relationships, but noted that there are few formal mechanisms in place for coordination and communication between the two organizations. While there is an approach used by CIC and the CBSA that allows for the sharing of files, interviewees and focus group participants felt that they rely on informal contacts to obtain required information (e.g., claimant-related information, document analysis). Interviewees from both the CBSA and CIC and CIC focus group participants expressed the need for more formal channels for information exchange between the two departments, particularly at the regional level. The lack of formal channels may be reflective of the fact that the Pilot was in the early stages of implementation at the time of the evaluation.

In addition to the Operational and Implementation Issues Working Group, the IRB's Regional Consultative Committee on Practices and ProceduresFootnote 19 was noted by CIC and IRB interviewees as a forum through which information could be obtained from the IRB, although they noted it was primarily a forum for the IRB to provide information to stakeholders, and not one through which stakeholders could bring issues forward for discussion. Outside of this committee, IRB and CIC interviewees and CIC focus group participants noted that communication and coordination between the two organizations is limited to administrative issues but that the appropriate channels are in place and are working well (i.e., CIC can contact the registries or case officers, as is the case for all government departments).

One issue for CIC with respect to coordination with the IRB is the fact that all information exchange is paper-based. A few also noted a desire to have more direct contact with the IRB; although it is recognize that the IRB is arm's-length and thus opportunities for communication and coordination are limited.

3.1.2 Contribution of the Pilot to Program Integrity

Finding: The Reviews and Interventions Pilot has positively contributed to the integrity of the asylum system because it has identified issues of credibility and program integrity and brought that information forward to IRB decision-makers, which may not have previously been available.

Availability of Information Prior to the R&I Pilot

As a result of conducting interventions, CIC has provided information to IRB decision-makers that may not have previously been available consistently across the country. CBSA interviewees noted that because its mandate is related to security and criminality, the conduct of reviews and interventions is prioritized based on those grounds and that, while the Montreal and Vancouver CBSA offices had the capacity to also conduct reviews and interventions on grounds of credibility and program integrity prior to the implementation of CIC's pilot, the Toronto CBSA office did not.

Number of Reviews and Interventions Completed

In the first 18 months of the Pilot (January 2013-June 2014), CIC conducted 10,775 reviews of in-Canada claims, with just over three quarters (77%) of those claims being reviewed prior to being heard at the RPD (Table 3.1). CIC conducted interventions on 23% of the cases that were reviewed, which represents 2,465 interventions, almost all of which were conducted on claims before the RPD (98%). The majority of reviews (about 78%) and interventions (70%) conducted at RPD were conducted by the R&I office in Toronto.Footnote 20 The Montreal R&I office conducted about 13% of the reviews and about 20% of the interventions made during this period, and the Vancouver R&I office conducted about 8% of the reviews and about 11% of the interventions. Of the 2,404 cases in which CIC intervened before the RPD, 91% had issues related to credibility and 52% had issues related to program integrity, which indicates that CIC R&I officers identified multiple grounds for interventions.

| January 2013 - December 2013 |

January 2014 - June 2014 |

Total | Total as % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reviews | ||||

| Refugee Protection Division | 5,485 | 2,798 | 8,283 | 77% |

| Refugee Appeal Division | 1,062 | 1,430 | 2,492 | 23% |

| Total | 6,547 | 4,228 | 10,775 | 100% |

| Interventions | ||||

| Refugee Protection Division | 1,934 | 470 | 2,404 | 98% |

| Refugee Appeal Division | 37 | 24 | 61 | 2% |

| Total | 1,971 | 494 | 2,465 | 100% |

| % of cases intervened | 30% | 11% | 23% | -- |

Sources: Operations Performance Management Branch; Monitoring, Analysis, and Country Assessment Division.

As noted in Section 3.1.1, the original scope of the Pilot was expanded to include trend analysis and the review of in-Canada claims made prior to December 15, 2012 (legacy cases). Of the total number of reviews conducted, 18% of those before RPD and 4% of those before RAD were legacy cases (Table 3.2). Of the total number of interventions conducted at RPD, 38% were legacy cases. The high percentage of interventions on legacy cases is attributable to the trend analysis work that the R&I units conducted, which resulted in a large number of interventions filed against a particular group of claimants in February and March 2013, who had made claims prior to December 2012.

| January 2013 - December 2013 |

January 2014 - June 2014 |

Total | Total as % | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reviews at RPD | ||||

| New Cases | 4,123 | 2,646 | 6,769 | 82% |

| Legacy Cases | 1,362 | 152 | 1,514 | 18% |

| Total | 5,485 | 2,798 | 8,283 | 100% |

| Reviews at RAD | ||||

| New Cases | 1,017 | 1,373 | 2,390 | 96% |

| Legacy Cases | 45 | 57 | 102 | 4% |

| Total | 1,062 | 1,430 | 2,492 | 100% |

| Interventions at RPD | ||||

| New Cases | 1,083 | 404 | 1,487 | 62% |

| Legacy Cases | 851 | 66 | 917 | 38% |

| Total | 1,934 | 470 | 2,404 | 100% |

Source: Operations Performance Management Branch.

Impact of the Reviews and Interventions

Finding: There is evidence that the R&I information is being used in IRB decision-making and that interventions have had an impact on acceptance rates of in-Canada claims, particularly on a per-country basis.

Although it was not possible to ask IRB decision-makers directly about the value-added of the Pilot, the evaluation reviewed a small number of RPD written decisions to determine whether there was any indication that the information provided by the intervention was being used.Footnote 21 In several cases, the written decision cited evidence specifically from the reviews and interventions as a factor in the decision, which suggests that it is being considered in decision-making. The R&I office was also able to provide anecdotal evidence, including e-mail exchanges, showing that issues of credibility and program integrity are being identified, and that trends in claims are being noticed and flagged for further investigation.

In terms of measuring the added-value of the interventions, the evaluation examined the RPD decision rates for 2013 and compared cases in which interventions were made and cases in which interventions were not made. It is important to note that examining the changes in the rates of positive or negative RPD decisions over time (i.e., comparing 2013 to previous years) is not the most appropriate indicator to measure the value-added of the reviews and interventions. First, because of the small number of interventions conducted, compared to the total number of claims each year, it would be unlikely that overall decision rates would be affected. Second, as noted by CIC interviewees, the expected result of an intervention is not a negative decision. Rather, the intent is to ensure that comprehensive information is brought forward for decision-making and to improve the integrity of the system by providing a challenge function during the refugee determination process.

For 2013 cases, it was observed that where an intervention took place, decision rates differed from cases where no intervention was made. For example, as shown in Table 3.3, in cases intervened by either CIC or the CBSA, there was a higher proportion of negative RPD decisions than in cases where no intervention was made. The strongest effects observed were for the rate of positive RPD decisions, where positive decisions were 40% when no intervention was conducted and 24% when a CIC intervention was conducted and 26% when a CBSA intervention was conducted. This is based on a total number of 20,474 decisions at the RPD in 2013. Of these decisions, CIC intervened in 805 cases; the CBSA intervened in 643 cases; and no intervention was made in 19,026 cases.

| Intervention Type | Positive RPD Decision | Positive RPD Decision (%) | Negative RPD Decision | Negative RPD Decision (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CIC Intervention | 192 | 24% | 400 | 50% |

| CBSA Intervention | 170 | 26% | 334 | 52% |

| No Intervention | 7653 | 40% | 8,894 | 47% |

| Overall | 8,015 | 39% | 9,628 | 47% |

Source: Refugee Claimant Continuum.

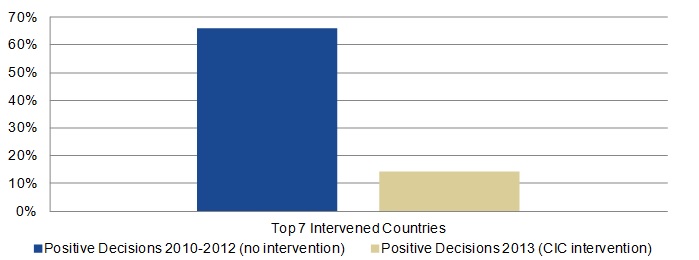

An examination of the decision rates by claimant country of citizenship suggests that these differences are attributable to claims from a few countries in particular. The evaluation examined the RPD decision rates for claimants by country of alleged persecution for which CIC had conducted a large number of interventions. Seven of these countries accounted for 49% of the total number of interventions conducted by CIC in 2013 (391 of 805). This showed that the positive RPD decision rate in 2013 was lower than in the three previous years when CIC was not conducting interventions. As illustrated in Figure 3.1, between 2010 and 2012, 66% of claims made by citizens of these seven countries received a positive decision from the RPD. In 2013, only 14% of claims made by citizens of these countries received a positive RPD decision, with certain countries experiencing significant declines in their rates (ranging from a 6% to 74% decrease). Acceptance rates can be influenced by variety of factors beyond interventions, and thus, the associated change in acceptance rates cannot be attributed solely to the intervention.Footnote 22 Further, it is important to note that CIC conducts an intervention when issues of credibility or program integrity are identified, regardless of country of citizenship.

In 2013, the majority of CIC's interventions were based on program integrity concerns related to migration trends, as well as credibility concerns triggered by discrepancies and/or inconsistencies in claimants' information. The third highest category was credibility issues related to claimants' previous Canadian immigration history, including previous misrepresentation (e.g., failure to disclose information or providing false information).

Figure 3.1: RPD Positive Decision Rates (2010-2012 and 2013), for Most-intervened Countries

Figure 3.1: RPD Positive Decision Rates (2010-2012 and 2013), for Most-intervened Countries - Table

| Decision rate | |

|---|---|

| Position decision 2010-2012 (no intervention) | 66% |

| Position decisions 2013 (CIC intervention) | 14% |

Source: Refugee Claimant Continuum

While it appears that CIC interventions are adding value in terms of providing additional comprehensive information for decision-making and on RPD decision rates, it is important to note that interventions are conducted on only a very small proportion of total cases. In 2013, there were 20,474 decisions rendered by the RPD, 4% (805) of which had interventions conducted by CIC and about one-quarter (204) of these interventions were as a result of trend analysis work conducted by the R&I offices on legacy cases. Thus, the overall value-added of the reviews and interventions has been achieved by focusing on known areas of concern about integrity and credibility within the refugee program.

It was difficult to reconcile the program data with the perspectives of interviewees, as CIC and CBSA interviewees held opposing views. Some CBSA interviewees questioned the value of the pilot because:

- the CBSA had previously intervened on credibility grounds on some cases in some regions; and

- new information was not always being provided through the CIC interventions.

CIC interviewees and CIC focus group participants expressed strong support for the pilot and noted that it provided important incremental value because:

- it ensures that comprehensive information is made available for decision-making and compiles it in a way that can be used in the decision-making process;

- intervention information provided by CIC was specifically cited in IRB decisions;

- increased rates of withdrawal and abandonmentFootnote 23 ; and

- the work in trend analysis has yielded some strong results and they have seen changes in the rates of negative IRB decisions.

3.1.3 Efficiency of the Pilot

The evaluation examined the efficiency of the Pilot in terms of whether it met planned targets for the number of reviews and interventions and its impact on the holding of IRB hearings.

Finding: Overall, CIC was able to conduct the number of reviews and interventions for which it was funded, although it was necessary to review claims that were made prior to the reforms coming into force to meet these targets.

Meeting of Targets

Foundation documents for the Pilot outlined targets for the number of reviews and interventions that CIC would conduct.Footnote 24 However, these targets were adjusted during implementation due to changes to the process that were not accounted for during its design. In particular, because the triage function is shared between CIC and the CBSA, it was not possible to establish in advance the number of claims that each department would be accountable for reviewing. The challenges in establishing a target number of reviews had a cascading effect on the ability of the Pilot to measure progress against the other targets that had been established.

As a result, the 2013 year-end Metrics of Success report noted that the established targets (in terms of the percentage of cases reviewed) no longer reflected the effectiveness of the Pilot.Footnote 25 Instead, the volume of reviews and interventions of both new and legacy cases was measured against the funded levels for that year. Based on an anticipated volume of in-Canada refugee claims of 22,500, the targets were revised to 6,790 reviews and 1,514 interventions (for the period December 15, 2012 to December 31, 2012). This target was further defined by the number of reviews and interventions to be conducted at RPD and RAD.

As shown in Table 3.4, for the period December 15, 2012 to December 31, 2013, 6,547 reviews (96% of the target) and 1,971 interventions (130% of the target) were conducted. The Pilot was able to exceed the funded targets for reviews and interventions at the RPD. The targets related to reviews and interventions at the RAD were not achieved, with only 58% of the reviews target and 6% of the interventions conducted. This was a result of receiving a lower number of in-Canada claims than anticipated, which limited the number of claims that ultimately were heard at the RAD.Footnote 26

| Funded Target Footnote * | Number Conducted | % of Target Met | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reviews | |||

| Refugee Protection Division | 4,944 | 5,485 | 111% |

| Refugee Appeal Division | 1,846 | 1,062 | 58% |

| Total | 6,790 | 6,547 | 96% |

| Interventions | |||

| Refugee Protection Division | 852 | 1,934 | 227% |

| Refugee Appeal Division | 662 | 37 | 6% |

| Total | 1,514 | 1,971 | 130% |

Source: Operations Performance Management Branch.

It is important to note that the meeting of the funded targets was achieved through the review of legacy cases), which was not the original intent of the Pilot. As noted in Section 3.1.2, due to the lower number of claims than expected in the first year of the Pilot (10,336 claims received, rather than the 22,500 anticipated), CIC began reviewing in-Canada claims made prior to December 15, 2012. This represented 18% of all claims reviewed before RPD and 38% of all claims intervened before RPD. Again, the low number of new cases reviewed was a result of lower-than-anticipated claim volumes, which meant that fewer cases were brought before the RAD.

Impact on CBSA Hearings Processes, IRB Registry Processes, and the Holding of RPD Hearings

Finding: CIC's reviews and interventions function did not have a negative impact on CBSA hearings processes or IRB registry processes, nor did it contribute significantly to delays in the holding of Refugee Protection Division hearings.

CBSA and IRB interviewees were asked their views on the impact of the Pilot on the CBSA hearings processes and IRB registry processes, in terms of adding inefficiencies or delays. Interviewees did not note any impacts on these processes, although CBSA interviewees noted operational challenges related to the joint triage process (for more on this see Section 3.2.3).

The evaluation also did not find any evidence that the R&I Pilot caused delays in the holding of RPD hearings. The reforms to the in-Canada asylum system established timelines for when claims were to be scheduled for RPD hearings, based on whether the claimant was from a DCO or non-DCO, and on whether the claim was made at an inland office or at a port of entry. As per the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act, hearings before the RPD are to be “fixed” within 30, 45, or 60 days (30 days after referral to RPD for DCO claimants who have made their claim inland; 45 days after referral to RPD for DCO claimants who have made their claim at POE; and 60 days after referral for all non-DCO claimants). The 2013 Year-End Metrics of Success Report noted that the policy intent was to have hearings held within those legislated timelines and thus reporting is done against those timeframes. Therefore, the evaluation also examined the extent to which the holding of the hearing was delayed as a result of interventions.

Interviewees from the IRB Registries did not cite any concerns related to the impact of the Pilot on the scheduling or holding of hearings. In addition, while information from the 2013 Year-End Metrics of Success Report noted that 36% (2,924) of hearings did not take place on time (Table 3.5), 29% of those (858) were delayed due to reasons of fairness and natural justice (delays due to an intervention are one of a number of reasons for delay included in this category). The front-end screening process accounted for almost half of the delays in holding of hearings (48% or 1,418 of 2,924).

The Metrics of Success Report does not provide further detail on the proportion of these delays that may be due to reviews and interventions. One other data source was examined to determine the extent to which delays in the holding of the hearing could be attributed to the reviews and interventions function. The evaluation reviewed the reasons for hearing delays for all cases where an intervention took place at the RPD in 2013. The review determined that there was no evidence to suggest that interventions contributed significantly to delays in the holding of Refugee Protection Division hearings (accounting for less than 5% of the total number of delays).Footnote 27

| DCO # of Claims | DCO % |

Non-DCO # of Claims | Non-DCO % |

Total # of Claims | Total % |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RPD hearings held on time | 302 | 47 | 4,953 | 66 | 5,255 | 64 |

| Late hearings | 343 | 53 | 2,581 | 34 | 2,924 | 36 |

| Total | 645 | 100 | 7,534 | 100 | 8,179 | 100 |

Source: 2013 Year-End Metrics of Success Report

3.2 Relevance

3.2.1 Need for Reviews and Interventions

Finding: There is a need to conduct reviews and interventions for credibility and program integrity reasons to ensure that comprehensive information is brought forward for the IRB decision-making process, therefore contributing to the overall integrity of the asylum system.

As a result of the reviews and interventions Pilot project, CIC proceeded with an intervention in 23% of the cases that it reviewed. This suggests that CIC had identified issues related to credibility and program integrity, which it felt would not have been sufficiently brought forward to decision-makers. As previously mentioned, information from the interventions are figured in IRB written decisions and CIC interventions have resulted in lower acceptance rates in RPD cases that received a decision in 2013, which supports to need to have a reviews and interventions mechanism in place.Footnote 28 CIC conducts an intervention when issues of program integrity or credibility are identified. In some instances, trend analysis points to potential systemic issues with claiminants from particular regions or countries of origin. The pilot provided an approach for identifying and dealing with the systemic issues.

Furthermore, the majority of CBSA interviewees and all CIC interviewees agreed that having a reviews and interventions function in place is important to ensure the integrity of the refugee program, to act as a deterrent for abuse, and to ensure that decision-makers have comprehensive information required to support their decisions. Many CIC interviewees noted that they see the added value of their interventions in decision-making (i.e., number of refusals) and thus see that as an indicator that the function is needed.

3.2.2 Consistency with Departmental and Government-Wide Priorities

Finding: The R&I Pilot is aligned with departmental and governmental priorities related to improving the integrity of the asylum system.

Improving the integrity of the in-Canada asylum system was identified as a priority in CIC's planning and reporting documents as early as 2006/07. In subsequent years, these documents continue to note the department's desire to streamline the in-Canada asylum system and achieve faster results; in 2009/10, CIC identified a focus on reviewing refugee-oriented policies and programs to ensure program integrity, and signalled that it was would address the timeliness, efficiency, and effectiveness of the in-Canada asylum system.Footnote 29

The integrity of the asylum system, and the need to implement changes to improve it, were identified as an ongoing priority for the Government of Canada, and was referenced in the 2010 and 2013 Speeches from the Throne. This issue was also raised in several speeches made by the Minister of CIC between 2010 and 2012. The coming-into-force of the Balanced Refugee Reform Act (June 2010) and the Protecting Canada's Immigration System Act (June 2012) indicated the government's commitment to refining Canada's asylum system.

With its focus on integrity, credibility, and fraud, the Pilot was developed as a mechanism to enhance the integrity of the in-Canada asylum system and reduce system abuse, thus aligning with CIC and Government of Canada priorities.

3.2.3 Role and Responsibility of the Federal Government

Finding: The government of Canada has a legislated responsibility to protect refugees, but to also ensure the integrity of the refugee system, which is aligned with the objectives of the Pilot. The roles of the CBSA and CIC in conducting reviews and interventions are in alignment with their respective departmental mandates. However, from an operational perspective, greater clarity is required with respect to the division of responsibilities, particularly around the triage process and hybrid cases.

Federal Role and Responsibility for Refugee Protection and Safeguarding the in-Canada Asylum System

As a signatory to the 1951 Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees; the 1967 Protocol; the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment; and further to provisions set forth in the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms, Canada has international and domestic legal obligations to provide safe haven to individuals in need of protection. The federal government's mandate for refugee protection is derived from the Immigration and Refugee Protection Act (Section 3(2)), which came into force following major legislative reform in 2002. Section 3(2) also states ensuring the integrity of the Canadian refugee protection system is maintained as an objective. Thus, in addition to ensuring the protection of refugees, the federal government is responsible for implementing measures to safeguard the integrity of the in-Canada asylum system, which is the main objective of the Pilot.

Role of CIC and the CBSA in the Reviews and Interventions Pilot

As noted, both CIC and the CBSA have a reviews and interventions function—CIC's focuses on issues related to credibility and program integrity and the CBSA's focuses on issues related to criminality and security. The evaluation examined the rationale for having this mandate split between two federal departments and its impact on the delivery of the function. Based on program documentation and information from interviews, the rationale for CIC's pilot was based on the fact that the CBSA did not systematically review credibility and program integrity issues across all regions (although CBSA interviewees noted that it was conducting reviews and interventions on issues related to credibility and program integrity in its Montreal and Vancouver offices prior to the Pilot).

There were opposing views on whether having two departments share the responsibility was efficient from an operational perspective. CIC interviewees felt strongly that the division of responsibilities is reasonable given the mandates of the departments and did not raise any concerns about duplication of roles or inefficiencies. CIC interviewees believed that CIC should continue in its role in interventions because it is better positioned to intervene on cases of credibility in support of CIC's current objective to improving the integrity of the in-Canada asylum system.

In contrast, CBSA interviewees had strong views that the CBSA is best positioned to conduct the reviews and interventions because it has the capacity and expertise to do so. They also noted that the sharing of the responsibility has resulted in some operational challenges, such as the triage process, which was highlighted as one of the biggest challenges, and also noted that it can sometimes take CIC some time to triage the file and provide it to the CBSA (in Ontario region). In addition, when a hybrid caseFootnote 30 is identified, it is the CBSA's responsibility to review. However, CBSA interviewees noted that there can be disagreement between the two departments on the definition and identification of hybrid cases, which has resulted in the file being sent back and forth between the two departments. CBSA interviewees generally felt that it would be more efficient for only the CBSA to conduct reviews and interventions, and at a minimum, the CBSA should be responsible for triaging in all regions.

Because the CBSA reviews and interventions function was outside the scope of the evaluation and because the CBSA's and CIC's reviews and interventions function differ (i.e., process for interventions, reasons for interventions), the evaluation did not aim to compare the individual efficiency or effectiveness of each of the two functions. Thus, it is not possible to draw conclusions on whether it would be more efficient or effective to have the function centralized in one department. Any future evaluation of the function will need to be conducted jointly with CBSA to develop a comprehensive assessment of all R&I aspects.