Archived - Laboratory exposures to human pathogens and toxins in Canada 2017

Download this article as a PDF

Download this article as a PDFPublished by: The Public Health Agency of Canada

Issue: Volume 44-11: Healthcare-associated infections and antimicrobial resistance

Date published: November 1, 2018

ISSN: 1481-8531

Submit a manuscript

About CCDR

Browse

Volume 44-11, November 1, 2018: Healthcare-associated infections and antimicrobial resistance

Surveillance

Surveillance of laboratory exposures to human pathogens and toxins: Canada 2017

D Pomerleau-Normandin1, M Heisz1, F Tanguay1

Affiliation

1 Centre for Biosecurity, Public Health Agency of Canada, Ottawa, ON

Correspondence

Suggested citation

Pomerleau-Normandin D, Heisz M, Tanguay F. Surveillance of laboratory exposures to human pathogens and toxins: Canada 2017. Can Commun Dis Rep 2018;44(11):297–304. https://doi.org/10.14745/ccdr.v44i11a05

Keywords: laboratory exposures, laboratory incidents, laboratory-acquired infections, human pathogens, surveillance, bacteria, virus, toxins, biosafety

Abstract

Background: Under Canada’s Human Pathogens and Toxins Act and Human Pathogens and Toxins Regulations, the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) is mandated with monitoring laboratory incident notifications through the Laboratory Incident Notification Canada (LINC) surveillance system. The year 2017 marks the second complete year of data.

Objective: To describe the laboratory exposure and laboratory-acquired infection incidents that occurred in Canada in 2017 by sector, human pathogens and toxins involved, number of affected persons, incident type and root causes.

Methods: The incidents included in the analysis occurred between January 1 and December 31, 2017. They were reported by laboratories with active licences to PHAC through the LINC surveillance system. Microsoft Excel 2010 was used for basic descriptive statistics.

Results: A total of 44 exposure and laboratory-acquired infection incidents were reported to the LINC in 2017. Compared by sector and their respective shares of licences, the number of incidents was highest in the academic and hospital sectors compared with government laboratories and private industry. Altogether 118 people were exposed for an average of 2.7 people per incident (range of 1–29). There were no reports of secondary exposure. Six exposure incidents (14%) led to “suspected” (n=5) or confirmed (n=1) cases of laboratory-acquired infection. Although overall, risk group (RG)2 human pathogens and toxins were involved in the majority of incidents (n=23; 52%), Francisella tularensis (n=4; 9%) and Coccidioides immitis (n=3; 7%) were the most frequently involved in reported exposure incidents. These two pathogens are both RG3 and security-sensitive biological agents (SSBAs). An average of 2.3 root causes were identified per incident (n=101). Problems with standard operating procedures (SOPs) and human error were the two most common causes.

Introduction

Laboratories that enable the study and diagnosis of pathogens and their associated toxins pose an inherent risk of exposure to those who work in them. Yet until recently, laboratory incidents were only reported internally and, when applicable, to occupational health authorities. A few countries developed some reporting requirements for biosafety and biosecurity-related incidents at the national level Footnote 1Footnote 2Footnote 3. However, it was the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) that established one of the first comprehensive and standardized surveillance systems of laboratory incidents involving human pathogens and toxins at the national level. The Laboratory Incident Notification Canada (LINC) surveillance system was launched in December 2015 in response to the requirements established by the 2009 Human Pathogens and Toxins Act (HPTA) Footnote 4 and the subsequent the Human Pathogens and Toxins Regulations (HPTR) Footnote 5. The year 2017 therefore represents the second complete year of data gathered through the LINC surveillance system.

Under the HPTA and HPTR, it is mandatory for organizations performing controlled activities with human pathogens and toxins to be licenced, unless otherwise exempted. Of note, one organization may possess multiple licences, and one licence can cover multiple containment zones. The vast majority of the laboratory work performed in Canada involves risk group (RG)2 human pathogens and toxins (93.2%), which pose a moderate risk to individuals but low risk to public health, because they can cause serious disease in humans but are unlikely to do so. A minority of the laboratory work performed (6.4%) involves RG3 human pathogens, which pose a high risk to individuals but a low risk to public health, because they are likely to cause serious disease but are unlikely to spread. Work with RG4 organisms, which are of highest risk to both individuals and the community, represent only 0.2% of all regulated work. Similarly, activities involving Security-Sensitive Biological Agents (SSBAs) represent only 0.2% of all regulated work in Canada. SSBAs constitute a subset of human pathogens and toxins that pose an “increased biosecurity risk due to their potential or use as a biological weapon” Footnote 6Footnote 7. See Appendix for the definition of some commonly used terms.

Under the HPTA, it is mandatory for all licenced facilities to report incidents involving human pathogens and toxins of RG2 or higher to PHAC. Notifications include both exposures and non-exposure incidents. Exposures are defined as contact with, or close proximity to, human pathogens or toxins that may result in laboratory-acquired infections or intoxication (LAI). Non-exposure involves inadvertent possession, production and/or release of a human pathogen or toxin; a missing, lost or stolen human pathogen or toxin; or an SSBA not being received within 24 hours of expected arrival Footnote 8. The first full year of data from Canada’s LINC surveillance system was in 2016 Footnote 9. This study focuses on exposure incidents that occurred in 2017.

The objective of this report is to describe the laboratory exposure incidents that occurred in Canada between January 1 and December 31, 2017, by sector, human pathogens and toxins involved, number of affected persons, incident type and root causes.

Methods

The LINC surveillance system uses a customized interface of the Microsoft Dynamics Customer Relations Management (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, Washington, United States) program. Data is entered using standardized forms specific to the type of report submitted; most data fields in these forms are mandatory, which enables precise and accurate comparison. While incidents are self-reported, accuracy is validated throughout the investigatory process; the information can be updated until the final follow-up report is marked as complete and submitted online by the reporter. It is important to note that several follow-up reports can be submitted for a single event. In this study, we used the data of the final follow-up report. Incidents found to fall outside the scope of the HPTA and HPTR were removed from analysis.

The initial notification report provides the essential elements related to the incident such as the administrative information and brief description of the incident. The follow-up report provides information on the investigation results, the affected persons and corrective actions.

Data from reports of exposures and laboratory-acquired infections (suspected or confirmed) that occurred in 2017 were extracted from the system once it had been ensured that all expected data from that year had been entered. LAIs are often confirmed in the follow-up report based on the results of the investigation. However, some cases are never confirmed and remain “suspected”. For instance, if it is impossible to rule out that the infection might have been acquired outside the containment zone (i.e., community acquired) then the LAI will remain “suspected”. Ultimately, the status of the LAI is based on the local risk assessment and investigation.

Data elements used for analysis from the initial exposure reports included the licence information (number of licences, sector [academic, hospital, private industry/business, public health, veterinary/animal health, environmental, other]) and the key dates (incident dates, dates reported to internal authority, initial notification dates to PHAC). Data elements used for analysis from the follow-up report included the incident type, information on affected persons (number of primary affected, number of secondary affected,route of exposure, first aid, drug treatment and postexposure prophylaxis), the date of the submission of the follow-up report, the biological agent involved (type, risk group level), incident type(s) and the root cause(s) of the incident.

Microsoft Excel 2010 was used for basic descriptive analysis. All exposure and LAI data were reported except where it could lead to the exact identification of a licenced facility. In such cases, for security and confidentiality purposes, the information was not included in this report.

Results

As of December 31, 2017, Canada had issued 905 active licences permitting regulated activities involving human pathogen or toxins. From laboratories with active licences, a total of 51 exposure incidents were reported to the LINC surveillance system for incidents that occurred between January 1 and December 31, 2017. Following the investigation process, exposure was ruled out in seven cases, leaving a total of 44 exposure incidents. The sample included three incidents for which the exact dates remained unknown but the circumstances (type of incident and date internal authorities were first notified) allowed us to conclude that they occurred in the year 2017. In total, exposure and/or laboratory-acquired infection incidents occurred in 4.9% of all licenced facilities.

All confirmed exposures (n=44, 100%) occurred in containment level two laboratories. The majority were exposure-only cases (n=38; 86%). Of the six LAI cases, five remained “suspected” and only one resulted in a confirmed LAI (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Case selection and exposure incidents retained for analysis, Canada 2017

Text description: Figure 1

Figure 1: Case selection and exposure incidents retained for analysis, Canada 2017

Figure 1 is a figure of a flow chart. The first box states that 51 exposure incidents were notified to PHAC in 2018. A second box branches off and states that 44 incidents were confirmed and retained for analysis. Of these, 38 exposures and 6 laboratory-acquired infections (LIAs) were identified. From the 6 LAIs, 5 were suspected and 1 was confirmed.

From the 51 exposure incidents notified to PHAC (the initial flow chart box), 7 incidents were ruled out (removed from analysis).

Exposure incidents by sector

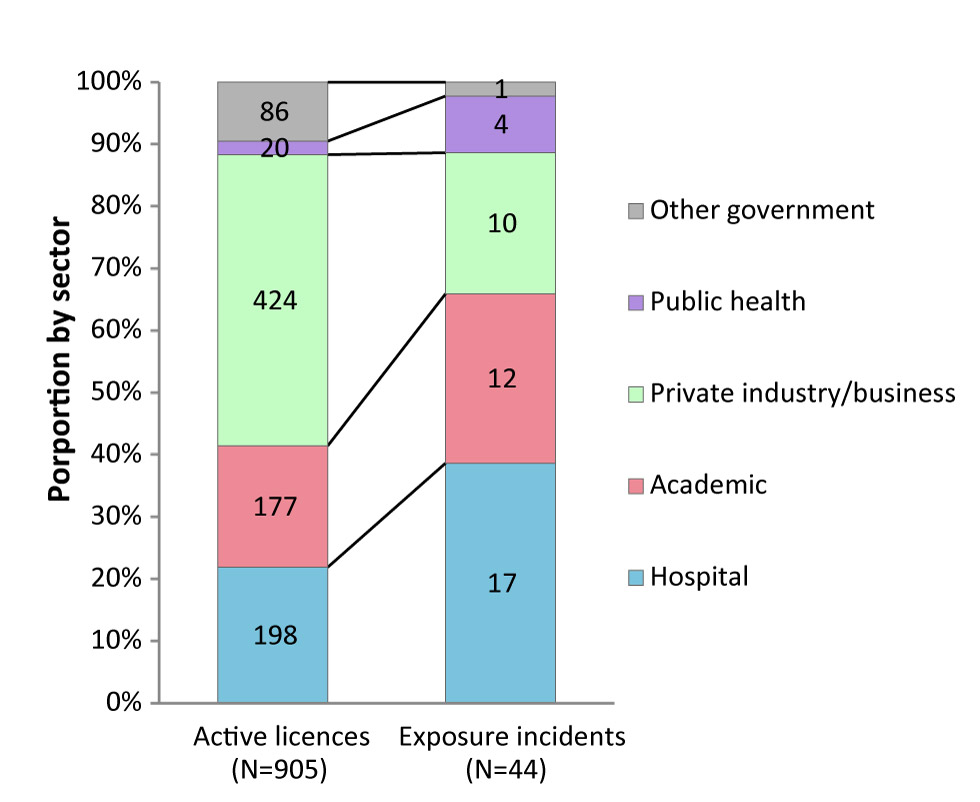

Figure 2 compares the number of active licences (N=905) to the number of exposure reports (N=44) submitted to the LINC surveillance system by sector in 2017. The laboratories that reported the highest number of exposure incidents in 2017 were from the academic and hospital sectors. Yet, compared to their respective shares of licences, the incidence of exposure incidents was higher in the public health (20%) and hospital (8.6%) sectors. The lowest incidence was in the private industry/business sector and other government sectors, with exposure incidents occurring in 2.4% and 1.2% of licenced facilities respectively.

Figure 2: Active licences and reported human pathogen or toxin exposure incidents, by sector, Canada 2017

Text description: Figure 2

| Proportion by sector | Active licences (n=905) |

Exposure incidents (n=44) |

|---|---|---|

| Other government | 86 | 1 |

| Public health | 20 | 4 |

| Private industry/business | 424 | 10 |

| Academic | 177 | 12 |

| Hospital | 198 | 17 |

Human pathogens and toxins involved

Table 1 presents the distribution of each human pathogen security status (non SSBA, SSBA), toxin risk group (2, 3 or 4) and type (bacterium, virus, toxin, prion or unknown) cited. RG2 human pathogens or toxins were involved in the majority of incidents (n=23; 52%). RG3 human pathogen or toxins were involved in 14 incidents (32%). The human pathogen or toxin involved remained unknown in seven incidents (16%). Among incidents with known pathogen or toxin involved (n=37), bacteria were the most often involved (n=21; 57%), followed by viruses (n=10; 27%).

In the 44 exposure incidents, 25 different human pathogens and toxins were identified. The three most frequently involved in the reported exposure incidents were Francisella tularensis (n=4; 9%), Coccidioides immitis (n=3; 7%)—both RG3 SSBAs—and Salmonella species (n=3; 7%).

| Biological agent type by risk group | Non SSBA | SSBA | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| RG2 | 22 | 88 | 1 | 8 | 23 | 52 |

| Bacterium | 11 | 44 | 0 | – | 11 | 25 |

| Toxin | 1 | 4 | 1 | 8 | 2 | 5 |

| Virus | 10 | 40 | 0 | – | 10 | 23 |

| RG3 | 3 | 12 | 11 | 92 | 14 | 32 |

| Bacterium | 2 | 8 | 8 | 67 | 10 | 23 |

| Fungus | 0 | – | 3 | 25 | 3 | 7 |

| Prion | 1 | 4 | 0 | – | 1 | 2 |

| Unknown | 0 | – | 0 | – | 7 | 16 |

| Total | 25 | 100 | 12 | 100 | 44 | 100 |

Number of affected persons

A total of 118 persons were exposed in the 44 exposure and/or laboratory-acquired infection incidents reported. The number of persons exposed per incident in 2017 ranged from 1 to 29. The average was 2.7 with a median of one. In the majority of exposure incidents (n=33; 75%), only one person was exposed. The incidents in which more than 10 persons were exposed (n=3) were reported from the private industry/business (n=1) and hospital (n=2) sectors. The incident in which 29 persons were exposed occurred in a diagnostic setting and was related to the slow growth of a Brucella species culture on standard media that was manipulated over more than one work shift. Table 2 presents the pathogens associated with exposures and laboratory-acquired infection.

Over a quarter of the affected persons (n=34; 29%) received postexposure prophylaxis within seven days of the exposure incident. In addition, 16 (14%) received first aid and seven (6%) underwent drug treatment. No secondary transmission was reported from the LAI.

| Biological agent | Incidents (N=44) |

Exposed persons (N=5) |

Suspected LAI (n=5) |

Confirmed LAI (n=1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RG2 | 23 | 25 | 3 | 1 |

| Rubella virus | 2 | 4 | – | – |

| Salmonella spp | 3 | 3 | 2 | – |

| Escherichia coli O157:H7 | 1 | 1 | – | 1 |

| Vaccinia virus | 2 | 1 | 1 | – |

| Other RG2 organisms | 15 | 16 | – | – |

| RG3 | 14 | 85 | 1 | 0 |

| Brucella suis | 1 | 29 | – | – |

| Francisella tularensis | 4 | 23 | – | – |

| Brucella abortus | 1 | 19 | – | – |

| Coccidioides immitis | 3 | 4 | – | – |

| Mycobacterium spp | 2 | 4 | 1 | – |

| Other RG3 organisms | 3 | 6 | – | – |

| Unknown | 7 | 8 | 1 | 0 |

| Total | 44 | 118 | 5 | 1 |

Incident types

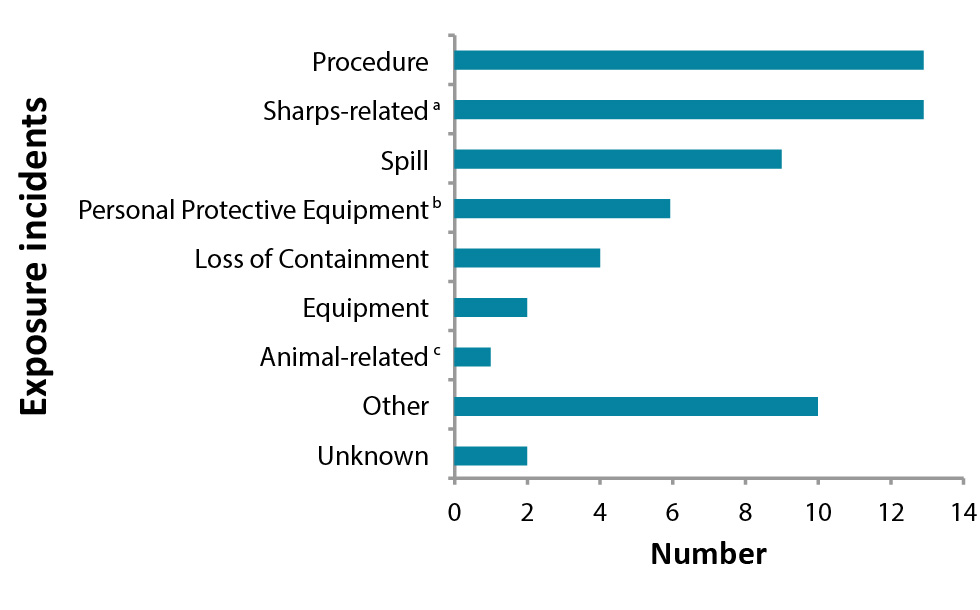

Figure 3 presents the types of exposure incidents reported in 2017 related to the specific action/event that prompted the incident. Most reports described incidents related to inadequate or breaches in procedures (n=13; 30%) and sharps (n=13; 30%). In 14 (32%) of the 44 exposure incidents, inadvertent possession of a RG3 biological agent in a containment level two laboratory also played a role in leading to exposure (data not shown). Such a scenario is more common in diagnostic settings as the specimen received may contain an unidentified human pathogen or toxin. Among the 14 cases of inadvertent possession, 11 (79%) were reported from the public health and hospital sectors. Exposures related to inadvertent possession often involved human pathogens or toxins that can be transmitted through aerosols (e.g., when handling Brucella species, Burkholderia pseudomallei, Coccidioides immitis and Francisella tularensis).

Figure 3: Reported incident types of human pathogen or toxin exposure incidents, Canada 2017 (N=60)

Text description: Figure 3

| Exposure incidents | Number |

|---|---|

| Unknown | 2 |

| Other | 10 |

| Animal-relatedFigure 3 footnote c | 1 |

| Equipment | 2 |

| Loss of Containment | 4 |

| Personal Protective EquipmentFigure 3 footnote b | 6 |

| Spill | 9 |

| Sharps-relatedFigure 3 footnote a | 13 |

| Procedure | 13 |

Route of exposure

Of the 118 persons affected in the 44 incidents, the majority were potentially exposed to infectious material through inhalation (n=72; 61%). The second most common route of exposure was through inoculation/injection via needle or sharps injury (n=11; 9%). Absorption via contact with the skin or mucous membrane, inoculation/injection via bites or a scratch, or ingestion were also routes of exposure reported in a few instances.

Root causes

A total of 101 root causes were identified for the 44 incidents reported in 2017, for an average of 2.3 root causes cited per incident. Table 3 presents the distribution of each root cause listed in the follow-up report. Standard operating procedures (SOPs) were cited in 37 (84%) reports, followed by human interaction in 14 reports (32%). Equipment was also a root cause in a quarter (n=11; 25%) of reported incidents.

| Root cause | Areas of concern | Citations | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | ||

| Standard operating procedure (SOP) | Documents were known but not followed | 37 | 84 |

| Documents were not known by user | |||

| Documents were not followed correctly | |||

| Documents were not correct for the task/activity | |||

| Documents were not in place but should have been in place | |||

| Human interaction | Labelling/placement/operation/displays of tools/equipment needed improvement | 14 | 32 |

| Environmental factors within the work area needed improvement | |||

| Workload constraints/pressures/demands needed improvement | |||

| Equipment | Equipment design needed improvement | 11 | 25 |

| Equipment was not properly maintained | |||

| Equipment failed | |||

| Equipment was not fit for purpose | |||

| Quality control was not performed/needed improvement | |||

| Communication | There was no method or system for communication | 10 | 23 |

| Communication did not occur | |||

| Communication was unclear, ambiguous or misunderstood | |||

| There was no method or system for communication | |||

| Training | Training was not developed or implemented | 8 | 18 |

| Training was inappropriate or insufficient | |||

| Training was available, but not completed | |||

| Staff were not qualified or proficient in performing the task | |||

| Management and oversight | Supervision needed improvement | 7 | 16 |

| Auditing/evaluating/enforcement of standard operating procedure needed improvement | |||

| Auditing/evaluation/enforcement of training needed improvement | |||

| Preparation needed improvement | |||

| Human factors needed improvement | |||

| Risk assessment needed improvement | |||

| Worker selection needed improvement | |||

| Other | 14 | 32 | |

Discussion

Overall, the incidence of laboratory exposures to pathogens and toxins in Canada remain relatively low in 2017, with a total of 44 incidents nation-wide representing slightly less than 5% of all licenced facilities. Most reports described were related to inadequate or breaches in procedures and sharps. Accordingly, SOPs and human error were cited most frequently as root causes of the incident.

We are unable to compare these findings to those in other countries, as there are no other comparable comprehensive national surveillance system. For example, in the United States the focus of incident reporting is limited to bloodborne pathogens.

The main strength of this study is that it is based on mandatory and standardized reporting of laboratory incidents across Canada, across all regulated toxins and pathogens. It therefore provides an overarching picture of biosafety in all licenced laboratories and allows the assessment of the true incidence of exposures and LAIs in Canada Footnote 10.

Conversely, the main limitation of this study is that the data may be incomplete. Under certain circumstances, laboratory incidents may not be reported. Incidents may not be detected or may simply not be reported due to a lack of awareness or understanding of the reporting requirements or due to a reluctance to report because of the generally negative interpretation of the term “incidents” Footnote 9. This is being addressed and, as regulated parties learn more about and normalize the reporting requirements, we expect the reporting frequency will increase over the next few years.

The information provided in the follow-up reports may also be biased due to the nature of the investigative process. Trying to identify the causes of the incident working backward based on the symptoms or general outcome can foster recall bias in the results of the investigation. To mitigate these limitations, the LINC surveillance system continuously makes adjustments to improve the user-friendliness and clarity of the forms and interface. PHAC is developing guidance documents to support regulated parties in incidents reporting and investigation.

There are some interesting preliminary comparisons of the 2016 and 2017 data. Despite the expectation that reporting incidents would increase over the first few years of the system, reporting incidents declined from 46 in 2016 Footnote 11 to 44 in 2017. The frequency of exposure incidents decreased in the academic sector (from 35% in 2016 to 27% in 2017) and increased in the hospital sector (from 26% in 2016 to 39% in 2017). Although the number of reported exposure incidents decreased in 2017, the number of people exposed increased by 18%, largely due to the one exposure incident of 29 people to Brucella suis. The proportions of SSBAs increased from 24% in 2016, to 27% in 2017. In both 2016 and 2017, procedures and sharps-related occurrences were the most cited incident types, which concur with the results reported in other studies Footnote 9Footnote 12Footnote 13. Inadvertent possession of an RG3 human pathogen in a containment level two laboratory was more frequently reported in 2017 (at 32%) compared to 2016 (at 22%). However, it should be noted that with only two years of complete data, it is too early to establish reliable baselines or identify trends.

The information acquired from this report is significant for several reasons. It provides an overarching snapshot of the current biosafety practices in laboratories across Canada and the biosafety risks that exist in these settings, which can serve as a comparative baseline for other reporting programs in Canada and elsewhere. PHAC has been able to develop outreach initiatives to improve awareness of commonly occurring incidents. For example, PHAC developed a newsletter with a notice related to sharps injuries due to disposable scalpel blades, and wrote a journal article describing the risk of misidentification of RG3/SSBAs by Matrix Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization-Time of Flight Mass Spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) device Footnote 14.

Conclusion

The incidence of laboratory exposure incidents was relatively low in 2017. The most common route of exposure was through inhalation and the most common root causes were problems with SOPs and human error. The LINC surveillance system will continue to identify risk factors and recurrent challenges in biosafety and biosecurity in laboratory settings and contribute to building excellence in investigation and response to laboratory incidents by sharing expertise and lessons learned among the laboratory community.

Authors’ statement

DPN – Incident monitoring, data analysis, writing – original draft, writing – review and editing

MH – Incident monitoring, writing – editing, supervision

FT – Incident monitoring, data analysis, writing – editing, supervision

Conflict of interest

None.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Craig Brooks and Ken Turcotte for their expertise and input. We would also extend our appreciation to all the licence holders and biological safety officers for providing high quality reports.

Funding

This work was supported by the Public Health Agency of Canada as part of its core mandate.

Appendix: Definitions relating to the Human Pathogens and Toxins Act

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Biological safety officer (BSO) | An individual designated for overseeing the facility’s biosafety and biosecurity practices. |

| Containment level (CL) | Minimum physical containment and operational practice requirements for handling human pathogens or toxins safely in laboratory environments. There are four containment levels, ranging from a basic to the highest level of containment (1 to 4). |

| Containment zone | A physical area that meets the requirements for a specified containment level. A containment zone can be a single room, a series of co-located rooms or several adjoining rooms. Dedicated support areas, including anterooms (with showers and ‘clean’ and ‘dirty’ change areas, where required), are considered to be part of the containment zone. |

| Exposure | Contact with, or close proximity to, human pathogens or toxins that may result in infection or intoxication, respectively. Routes of exposure include inhalation, ingestion, inoculation and absorption. |

| Exposure follow-up report | A tool used to report and document incident occurrence and investigation information for an exposure incident previously notified to the Public Health Agency of Canada. |

| Exposure notification report | A tool used to notify and document preliminary information to the Public Health Agency of Canada of an exposure incident. |

| Incident | An event or occurrence involving infectious material, infected animals or toxins that have the potential to result in injury, harm, infection, disease or cause damage. |

| Laboratory-acquired infection/intoxication | Infection or intoxication resulting from exposure to infectious material, infected animals, or toxins being handled or stored in the containment zone. |

| Licence | An authorization to conduct one or more controlled activities with human pathogens or toxins issued by the Public Health Agency of Canada under Section 18 of the Human Pathogens and Toxins Act. One licence can cover many containment zones. |

| Risk group (RG) | The classification of biological material based on its inherent characteristics, including pathogenicity, virulence, risk of spread and availability of effective prophylactic or therapeutic treatments, that describes the risk to the health of individuals and the public as well as the health of animals and the animal population. |

| Security-sensitive biological agents (SSBAs) | The subset of human pathogens and toxins that have been determined to pose an increased biosecurity risk due to their potential for use as a biological weapon. Security-sensitive biological agents are identified as prescribed human pathogens and toxins by Section 10 of the Human Pathogens and Toxins Regulations. This includes all risk group 3 and 4 human pathogens that are in the List of Human and Animal Pathogens for Export Control, published by the Australia Group, as amended from time to time, with the exception of Duvenhage virus, Rabies virus and all other members of the Lyssavirus genus, Vesicular stomatitis virus, and Lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus. This also includes all toxins listed in Schedule 1 of the Human Pathogens and Toxins Act that are listed on the List of Human and Animal Pathogens for Export Control when in a quantity greater than that specified in Section 10(2) of the Human Pathogens and Toxins Regulations. |

| For more definitions, please see the Canadian Biosafety Standard, Second Edition Footnote 15. | |