Public health and knowledge brokering

Download this article as a PDF

Download this article as a PDFPublished by: The Public Health Agency of Canada

Issue: Volume 47-3: Influenza and Other Respiratory Viruses

Date published: March 2021

ISSN: 1481-8531

Submit a manuscript

About CCDR

Browse

Volume 47-3: Influenza and Other Respiratory Viruses

Series

Knowledge brokering on infectious diseases for public health

Margaret Haworth-Brockman1,2, Yoav Keynan1,2,3

Affiliations

1 National Collaborating Centre for Infectious Diseases, Rady Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, MB

2 Department of Community Health Sciences, Max Rady College of Medicine, University of Medicine, Winnipeg, MB

3 Departments of Internal Medicine and Medical Microbiology, Max Rady College of Medicine, University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, MB

Correspondence

Suggested citation

Haworth-Brockman M, Keynan Y. Knowledge brokering on infectious diseases for public health. Can Commun Dis Rep 2021;47(3):161–5. https://doi.org/10.14745/ccdr.v47i03a06

Keywords: public health, infectious diseases, knowledge brokering, Canada, COVID-19

Abstract

The National Collaborating Centres (NCCs) for Public Health (NCCPH) were established in 2005 as part of the federal government's commitment to renew and strengthen public health following the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) epidemic. They were set up to support knowledge translation for more timely use of scientific research and other knowledges in public health practice, programs and policies in Canada. Six centres comprise the NCCPH, including the National Collaborating Centre for Infectious Diseases (NCCID). The NCCID works with public health practitioners to find, understand and use research and evidence on infectious diseases and related determinants of health. The NCCID has a mandate to forge connections between those who generate and those who use infectious diseases knowledge.

As the first article in a series on the NCCPH, we describe our role in knowledge brokering and the numerous methods and products that we have developed. In addition, we illustrate how NCCID has been able to work with public health to generate and share knowledge during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic.

Introduction

The National Collaborating Centres (NCCs) for Public Health (NCCPH) were established in 2005 as part of the Canadian federal government's commitment to renew and strengthen public health following the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) epidemic. The NCCs were set up to support knowledge translation for more timely use of scientific research and other knowledges in public health practice, programs and policies in CanadaFootnote 1. Funded by the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC), each of the six NCCs is hosted at a university or government-based organization and focuses on a specific public health area: Determinants of Health, Environmental Health, Healthy Public Policy, Indigenous Health, Infectious Diseases and Knowledge Translation Methods and ToolsFootnote 1.

The National Collaborating Centre for Infectious Diseases (NCCID) is hosted at the University of Manitoba and works with public health practitioners to find, understand and use research and evidence on infectious diseases and underlying determinants that affect disease distribution, impact and effective mitigation strategies. Our eight staff forge connections between those who generate and those who use infectious diseases knowledge related to a wide range of topics, including antimicrobial resistance and stewardship, sexually transmitted and blood-borne infections (STBBI), vaccine preventable diseases, tuberculosis (TB) and emerging infections.

As the first article in a series on the NCCPH, we describe knowledge translation role, specifically as knowledge brokersFootnote 2Footnote 3 and our numerous methods and products, and then illustrate how NCCID has been able to work with public health to nimbly and responsively mobilize knowledge during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic.

A program science framework for knowledge brokering

Every year, NCCID undertakes a variety of projects, based on consultations with stakeholders and evidence of existing knowledge gaps. Events and resources are developed in consultation with partners across Canada, although they are often tailored for specific audiences or regional contexts. Wherever possible, we work with the other NCCs to ensure greater applicability and relevance.

The NCCID uses a program science framework to organize our work and to focus on the stages of public health interventions. Program science is a systematic application of theoretical and empirical scientific knowledge to improve the design, implementation and evaluation of public health programsFootnote 4. It enables a rigorous commitment to understanding the different types of evidence that are needed and that can be acted upon in specific contextsFootnote 5. This framework allows us to demonstrate the interrelatedness of policy and practice-related evidence in different topic areas, while emphasizing the context and circumstances for promising practices in three areas: 1) drivers and burdens of infectious diseases—relating to the program science domain of surveillance; 2) public health responses and interventions—relating to the same domain in program science; and 3) systems and policy for monitoring infectious diseases—relating to the program science domain of monitoring and evaluationFootnote 6 (Table 1). In so doing, we illustrate overarching approaches that are applicable to several diseases and desired public health outcomes, especially in terms of health equity approaches for syndemics and for disadvantaged populations.

| Program science areas | Knowledge brokering topics | Intended outcomes |

|---|---|---|

| Drivers and burden of infectious diseases |

|

CHOOSE

|

| Public health responses and interventions |

|

DO

|

| Monitoring and evaluation |

|

ENSURE

|

ndemics and for disadvantaged populations.

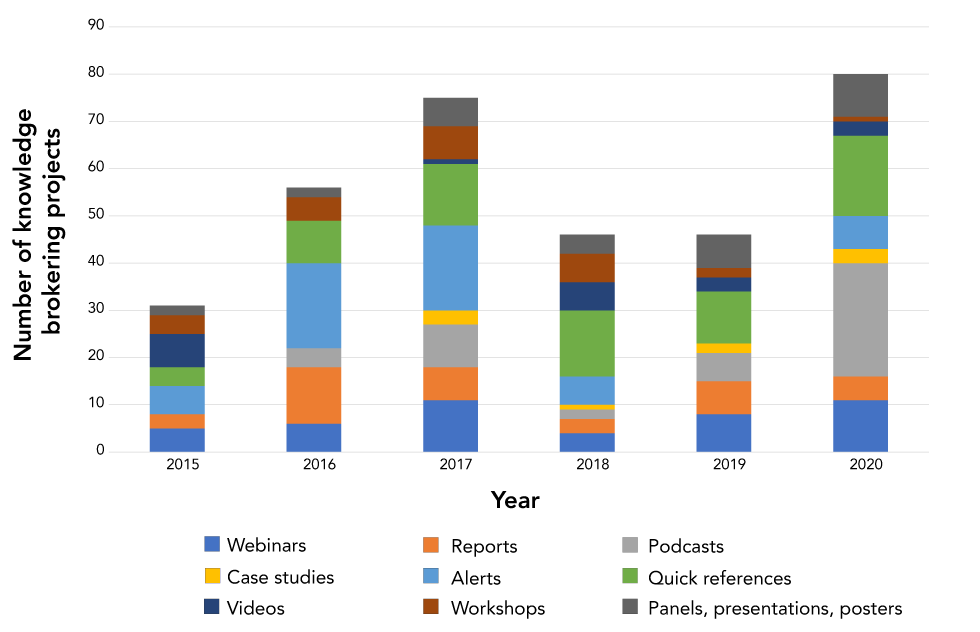

Knowledge brokering has been defined as both a process and a productFootnote 7Footnote 8. The NCCID undertakes different types of projects within the three program science areas (Figure 1). The first type of project relates to creating and fostering knowledge exchange among public health personnel at all levels; convening webinars, panel presentations, workshops and gatherings. The NCCID brings together community, policy, clinical and academic experts from several jurisdictions to discuss issues and share successful (and not-so-successful) public health strategies. Facilitated conversations, enabled by NCCID, encourage thoughtful consideration of timely questions. Using newer formats, such as fishbowl discussionsFootnote 9, expert commentaries, and pre-taped seminars, provides more time for presenters and participants to have lively discussions on content.

Figure 1: National Collaborating Centre for Infectious Diseases' knowledge brokering projects by type and year, 2015–2020

Text description: Figure 1

| Knowledge brokering projects | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | 2018 | 2019 | 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Webinars | 5 | 6 | 11 | 4 | 8 | 11 |

| Reports | 3 | 12 | 7 | 3 | 7 | 5 |

| Podcasts | 0 | 4 | 9 | 2 | 6 | 24 |

| Case studies | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Alerts | 6 | 18 | 18 | 6 | 0 | 7 |

| Quick references | 4 | 9 | 13 | 14 | 11 | 17 |

| Videos | 7 | 0 | 1 | 6 | 3 | 3 |

| Workshops | 4 | 5 | 7 | 6 | 2 | 1 |

| Panels, presentations, posters | 2 | 2 | 6 | 4 | 7 | 9 |

The NCCID develops and disseminates new knowledge products that apply evidence to specific public health practice and policy contexts. These knowledge products include podcasts, animated videos and plain-language case studies, as well as more traditional realist, scoping, and narrative reviews and journal papers. We tailor knowledge products to meet the specific needs of public health nurses, medical officers, policy analysts, students and front-line providers.

NCCID has integrated three overarching priorities across disease topics. The first priority is a focus on the mobility of populations in Canada. Earlier projects on public health approaches for refugees and asylum seekers, and on communities evacuated due to fires and floodsFootnote 10, highlighted the need for knowledge brokering on the effects of migration into and within Canada. For example, collecting data on and managing TB and syphilis outbreaks are complicated when patients have to moveFootnote 11, including from rural areas to cities and towns Footnote 12. Syndemics of STBBIs and TB, combined with growing epidemics of opioid and crystal methamphetamine use, are further complicated by movement, incarceration and jurisdictional dividesFootnote 13Footnote 14.

The second priority for NCCID is to address inequities in public health responses to communicable diseases in rural and remote communities. While resources are strained in all public health units, this is especially true outside of the main urban centres. As well as working with public health personnel to understand the particular drivers of infectious diseases in rural, remote and northern regions—including factors associated with stigma and poor mental health—NCCID serves as a secretariat for the Rural, Remote and Northern Public Health Network of public health physicians, and partners with Indigenous scholars and health authorities on First Nations, Métis and Inuit-specific approaches to address TB, STBBIs and vector-borne illnesses.

The third priority for NCCID is to support opportunities for using big data for infectious disease surveillance, prevention, control and monitoring. The NCCID has been at the forefront of creating opportunities for knowledge exchange between mathematical modellers and public health personnelFootnote 15Footnote 16. We recently started new collaborations with leading Canadian big data consultants to help demonstrate how big data can be used to plan and assess public health interventions.

The use of the program science framework allows NCCID to apply knowledge brokering methods and approaches across a number of topic areas. For example, NCCID is consistently explicit about which communities are disadvantaged (e.g. by geographic location, by systemic and historic racism or by inappropriate or inadequate public health and health care services) and which inequities can be mitigated to reduce disease burden. In the program science domain of public health responses, we highlight promising practices used to control one disease in a specific location that can be adapted to respond to another (e.g. providing evidence on rapid responses to curtail HIV outbreaks in Indiana that can be adapted to address rising hepatitis C in the Canadian Prairie ProvincesFootnote 17. In the domain of monitoring and evaluation, NCCID projects that encourage disaggregated and cross-tabulated indicators for monitoring public health program performanceFootnote 18 have been adapted to support health equity integration in public health organizationsFootnote 19.

National Collaborating Centre for Infectious Diseases in the time of COVID-19

With evidence in early January 2020 of a new COVID-19 that was likely to be transmitted beyond Asia, NCCID developed a new Quick Links resource for public health personnel, collating key information from the World Health Organization, PHAC and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. More thorough descriptions were developed into a Disease Debrief and posted online a week later. The information summary was updated throughout 2020 to keep up with the changes in clinical and epidemiological knowledge related to the pandemic.

By late January 2020, it was clear that the new disease was going to require more attention from public health both in Canada and around the world. The NCCID rapidly initiated a series of podcasts on many significant aspects of COVID-19, providing public health audiences with brief answers to commonly asked questions, and summarizing the latest evidence from experts across Canada. There are now 20 podcast episodes available for public health physicians, nurses, field inspectors and policy analysts which have been downloaded over 1,200 times to date, and were rated among the 30 best public health podcasts series in North America by MPH Online, an independent online resource for public health students.

The flexibility of NCCID's arrangements with PHAC allowed us to offer and follow through on a number of COVID-19 projects throughout 2020. These projects included supporting knowledge brokering via new Canadian Institutes of Health Research grants (eight grants to date), creating a hub for the Canadian Public Health Laboratory Network guidelines, developing a series of webinars to introduce mathematical modelling concepts to public health audiences and to delve into how models are used to plan COVID-19-related measures (over 350 attendees). In addition, the NCCID connected Canadian modelling experts to colleagues in Medellin, Colombia to support their ongoing modelling for public health. In the winter of 2020–2021, NCCID co-hosted PHAC's information webinars on the new COVID-19 vaccines (over 5,000 attendees).

In the context of population migration and rural, remote and northern equity concerns, NCCID staff and students are conducting more long-term projects. These projects include a forthcoming analysis of equity considerations of clinical treatment decision processes and the development of new models to predict longer-term outcomes of school closuresFootnote 20 and isolation measures in long-term care facilities.

Contributions to public health competencies in infectious diseases

The activities of the NCCID align with key areas of focus within the Canadian public health system in several ways. The NCCID contributes to the Chief Public Health Officer's overall goal of leveling "the playing field"Footnote 21 in the prevention and control of COVID-19, TB, STBBIs and antimicrobial resistance by fostering action on the determinants of health and strengthening multi-sectoral partnerships. The NCCID encourages cross-jurisdictional sharing of tried and successful approaches to reaching underserved populations.

Our academic and public health partnerships create teaching and mentorships opportunities for students, particularly in the following core competenciesFootnote 22:

- Prevention and control of infectious diseases

- Emergency responses

- Assessment, analysis and program planning

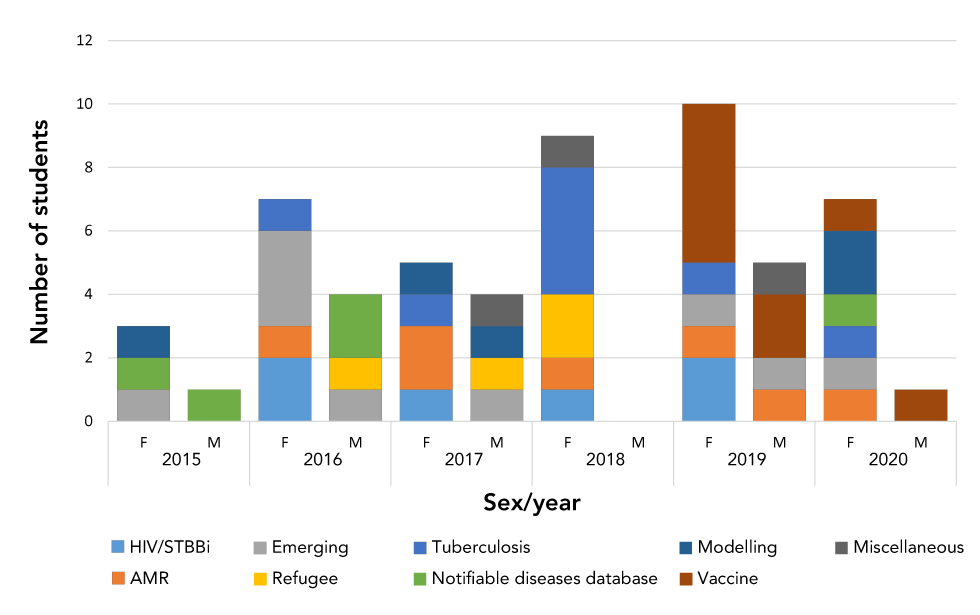

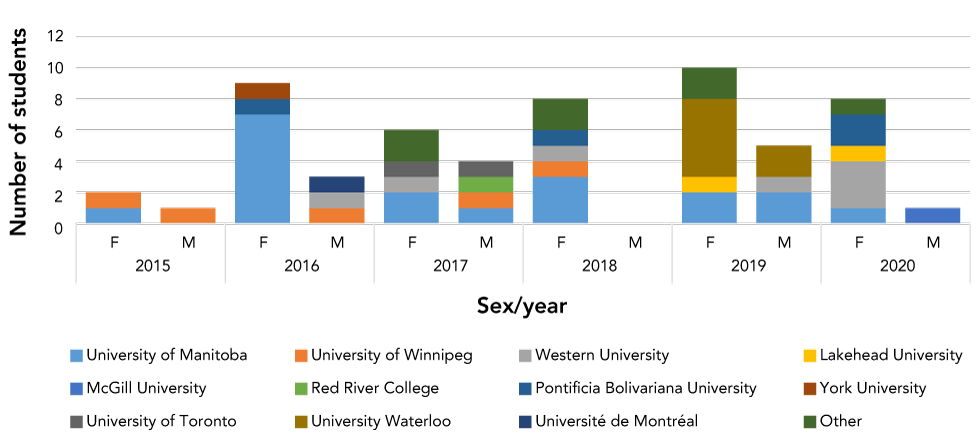

Undergraduate and post-graduate students in public health, medicine, basic sciences, nursing, communications and sociology are among the more than 40 trainees who have developed new skills in knowledge brokering at NCCID (Figures 2 and 3). Over time, NCCID has also drawn in participants from other sectors to encourage knowledge sharing to improve public health interventions for infectious diseases prevention and control.

Figure 2: Number of students at the National Collaborating Centre for Infectious Diseases, by topic research topic, by sex, and by year, 2015–2020

Text description: Figure 2

| Calendar year | Student | Research topic | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIV/STBBI | AMR | Emerging | Refugee | Tuberculosis | Notifiable diseases database | Modelling | Vaccine | Miscellaneous | ||

| 2015 | F | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| M | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 2016 | F | 2 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| M | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 2017 | F | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| M | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| 2018 | F | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| M | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 2019 | F | 2 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 |

| M | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 1 | |

| 2020 | F | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| M | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

Figure 3: Number of students at the National Collaborating Centre for Infectious Diseases, by home university, by sex, and by year, 2015–2020

Text description: Figure 3

| Calendar year | Student | Home university | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| University of Manitoba | University of Winnipeg | Western University | Lakehead University | McGill University | Red River College | Pontificia Bolivariana University Medillin, Colombia | York University | University of Toronto | University of Waterloo | Université de Montréal | Other | ||

| 2015 | F | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| M | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 2016 | F | 7 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| M | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| 2017 | F | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| M | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 2018 | F | 3 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| M | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 2019 | F | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 0 | 2 |

| M | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | |

| 2020 | F | 1 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| M | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

Conclusion

A knowledge broker adapts "to the social and technical affordances of each situation, and fashions a unique and relevant process to create relationships and promote learning and change"Footnote 23. This description aptly describes the role of NCCID. Analysis of the year-over-year increasing reach, uptake and impact of our activities and products confirm that our approach has value for public health audiences in Canada. By working with the other NCCs, and across disciplines, sectors and jurisdictions, NCCID optimizes the gathering and dissemination of knowledge, mobilization, facilitates development of networks and partnerships, and draws attention to knowledge gaps and issues for underserved populations. Our ability to bring to the table issues such as housing and addictions is critical for addressing determinants that often underlie disease transmission.

Authors' statement

- MHB — Original concept, initial drafts, final revisions

- YK — Original concept, substantive input, review of drafts

Competing interests

None.

Acknowledgements

Our thanks to colleagues at the National Collaborating Centres for Public Health Program and to the editors for this opportunity.

Funding

This work was funded by the Public Health Agency of Canada.

References

- Footnote 1

-

Medlar B, Mowat D, Di Ruggiero E, Frank J. Introducing the National Collaborating Centres for Public Health. CMAJ 2006;175(5):493-4. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.060850

- Footnote 2

-

National Collaborating Centre for Infectious Diseases. Knowledge Brokering for Infectious Diseases Public Health in Canada. Winnipeg (MB): NCCID; 2014. https://nccid.ca/publications/knowledge-brokering-for-infectious-diseases-public-health-in-canada-part-1/

- Footnote 3

-

Dobbins M, Robeson P, Ciliska D, Hanna S, Cameron R, O'Mara L, DeCorby K, Mercer S. A description of a knowledge broker role implemented as part of a randomized controlled trial evaluating three knowledge translation strategies. Implement Sci 2009;4:23. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-4-23

- Footnote 4

-

Blanchard JF, Aral SO. Program Science: an initiative to improve the planning, implementation and evaluation of HIV/sexually transmitted infection prevention programmes. Sex Transm Infect 2011;87(1):2-3. https://doi.org/10.1136/sti.2010.047555

- Footnote 5

-

Aral SO, Blanchard JF. The Program Science initiative: improving the planning, implementation and evaluation of HIV/STI prevention programs. Sex Transm Infect 2012;88(3):157-9. https://doi.org/10.1136/sextrans-2011-050389

- Footnote 6

-

Becker M, Haworth-Brockman M, Keynan Y. The value of program science to optimize knowledge brokering on infectious diseases for public health. BMC Public Health 2018;18(1):567. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-5493-7

- Footnote 7

-

Pablos-Mendez A, Shademani R. Knowledge translation in global health. J Contin Educ Health Prof 2006;26(1):81-6. https://doi.org/10.1002/chp.54

- Footnote 8

-

Green LW, Ottoson JM, García C, Hiatt RA. Diffusion theory and knowledge dissemination, utilization, and integration in public health. Annu Rev Public Health 2009;30(1):151-74. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.publhealth.031308.100049

- Footnote 9

-

Facing History and Ourselves. Teaching Strategy: Fishbowl (accessed 2020-10-02). https://www.facinghistory.org/resource-library/teaching-strategies/fishbowl

- Footnote 10

-

Clow B, Haworth-Brockman M, Boily-Larouche G, Qadar Z, Keynan Y. Looking for evidence of public health's role for long-term evacuees. Front Public Health 2019;7:15. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2019.00015

- Footnote 11

-

Asadi L, Heffernan C, Menzies D, Long R. Effectiveness of Canada's tuberculosis surveillance strategy in identifying immigrants at risk of developing and transmitting tuberculosis: a population-based retrospective cohort study. Lancet Public Health 2017;2(10):e450-7. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2468-2667(17)30161-5

- Footnote 12

-

Orr P. Adherence to tuberculosis care in Canadian Aboriginal populations, Part 1: definition, measurement, responsibility, barriers. Int J Circumpolar Health 2011;70(2):113-27. https://doi.org/10.3402/ijch.v70i2.17809

- Footnote 13

-

Quinn B, Gorbach PM, Okafor CN, Heinzerling KG, Shoptaw S. Investigating possible syndemic relationships between structural and drug use factors, sexual HIV transmission and viral load among men of colour who have sex with men in Los Angeles County. Drug Alcohol Rev 2020;39(2):116-27. https://doi.org/10.1111/dar.13026

- Footnote 14

-

Wise A, Finlayson T, Sionean C, Paz-Bailey G. Incarceration, HIV risk-related behaviors, and partner characteristics among heterosexual men at increased risk of HIV infection, 20 US cities. Public Health Rep 2019;134(1_suppl):63S-70S. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033354919833435

- Footnote 15

-

Moghadas SM, Haworth-Brockman M, Isfeld-Kiely H, Kettner J. Improving public health policy through infection transmission modelling: Guidelines for creating a Community of Practice. Can J Infect Dis Med Microbiol 2015;26(4):191-5. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/274569

- Footnote 16

-

Milwid R, Steriu A, Arino J, Heffernan J, Hyder A, Schanzer D, Gardner E, Haworth-Brockman M, Isfeld-Kiely H, Langley JM, Moghadas SM. Toward standardizing a lexicon of infectious disease modeling terms. Front Public Health 2016;4:213. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2016.00213

- Footnote 17

-

National Collaborating Centre for Infectious Diseases. Harm Reduction in a Rural Setting: Lessons learned from HCV and HIV outbreaks in Scott County, Indiana. Winnipeg (MB): NCCID; 2020 (accessed 2020-12-14). https://nccid.ca/publications/harm-reduction-in-a-rural-setting/?hilite=%27harm%27

- Footnote 18

-

Haworth-Brockman MJ, Keynan Y. Strengthening tuberculosis surveillance in Canada. CMAJ 2019;191(26):E743-4. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.72225

- Footnote 19

-

National Collaborating Centre for Infectious Diseases. Measuring What Counts in the Midst of the COVID-19 Pandemic: Equity Indicators for Public Health. Winnipeg (MB): NCCID; 2020. https://nccid.ca/publications/measuring-what-counts-in-the-midst-of-the-covid-19-pandemic-equity-indicators-for-public-health/

- Footnote 20

-

Abdollahi E, Haworth-Brockman M, Keynan Y, Langley JM, Moghadas SM. Simulating the effect of school closure during COVID-19 outbreaks in Ontario, Canada. BMC Med 2020;18(1):230. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-020-01705-8

- Footnote 21

-

Public Health Agency of Canada. Chief Public Health Officer of Canada: Health Equity Approach and Areas of Focus for Prevention and Promotion. Ottawa (ON): PHAC; 2020. https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/corporate/organizational-structure/canada-chief-public-health-officer/statements-chief-public-health-officer/health-equity-approach.html

- Footnote 22

-

Public Health Agency of Canada. Core Competencies for Public Health in Canada Release 1.0. Ottawa (ON): PHAC; 2008. https://www.phac-aspc.gc.ca/php-psp/ccph-cesp/pdfs/zcard-eng.pdf

- Footnote 23

-

Conklin J, Lusk E, Harris M, Stolee P. Knowledge brokers in a knowledge network: the case of Seniors Health Research Transfer Network knowledge brokers. Implement Sci 2013;8:7. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-8-7