Original mixed methods research – “I see beauty, I see art, I see design, I see love.” Findings from a resident-driven, co-designed gardening program in a long-term care facility

HPCDP Journal Home

Published by: The Public Health Agency of Canada

Date published: July 2022

ISSN: 2368-738X

Submit a manuscript

About HPCDP

Browse

Previous | Table of Contents | Next

Shannon Freeman, PhDAuthor reference footnote 1; Davina Banner, PhDAuthor reference footnote 1; Meg Labron, MSWAuthor reference footnote 2; Georgia Betkus, MScAuthor reference footnote 3; Tim Wood, MScNAuthor reference footnote 1; Erin Branco, RD, HBScAuthor reference footnote 4; Kelly Skinner, PhDAuthor reference footnote 5

https://doi.org/10.24095/hpcdp.42.7.03

This article has been peer reviewed.

Author references

Correspondence

Shannon Freeman, School of Nursing, University of Northern British Columbia, 3333 University Way, Prince George, BC V2N 4Z9; Tel: 250-960-5154; Email: shannon.freeman@unbc.ca

Suggested citation

Freeman S, Banner D, Labron M, Betkus G, Wood T, Branco E, Skinner K. “I see beauty, I see art, I see design, I see love.” Findings from a resident-driven, co-designed gardening program in a long-term care facility. Health Promot Chronic Dis Prev Can. 2022;42(7):288-300. https://doi.org/10.24095/hpcdp.42.7.03

Abstract

Background: Engagement with the natural environment is a meaningful activity for many people. People living in long-term care facilities can face barriers to going outdoors and engaging in nature-based activities. In response to needs expressed by our long-term care facility resident partners, we examined the feasibility and benefits of a co-designed hydroponic and raised-bed gardening program.

Methods: Our team of long-term care facility residents, staff and researchers co-designed and piloted a four-month hydroponic and raised-bed gardening program along with an activity and educational program, in 2019. Feedback was gathered from long-term care facility residents and staff through surveys (N = 23 at baseline; N = 23 at follow-up), through five focus groups (N = 19: n = 10 staff; n = 9 residents) and through photovoice (N = 5). A qualitative descriptive approach was applied to focus group transcripts to capture a rich account of participant experiences within the naturalistic context, and descriptive statistics were calculated.

Results: While most residents preferred to go outside (91%), few reported going outside every day (30%). Program participants expressed their joy about interacting with nature and watching plants grow. Analyses of focus group data generated the following themes: finding meaning; building connections with others through lifelong learning; impacts on mental health and well-being; opportunities to reminisce; reflection of self in gardening activities; benefits for staff; and enthusiasm for the program to continue.

Conclusion: Active and passive engagement in gardening activities benefitted residents with diverse abilities. This fostered opportunity for discussions, connections and increased interactions with others, which can help reduce social isolation. Gardening programs should be considered a feasible and important option that can support socialization, health and well-being.

Keywords: social isolation, loneliness, older adults, aging, photovoice, qualitative, co-creation, engagement, gardening

Highlights

- Integrating nature-based interventions, including hydroponic and raised-bed gardening, into the long-term care facility setting is feasible and can result in active and inclusive engagement of residents, along with meaningful conversation among residents and between residents and facility staff.

- Participation in gardening activities increased opportunities for social engagement and relationship building as well as for mitigating social isolation.

- Locating flower beds and/or hydroponic gardens in a high traffic area with nearby seating and access for wheelchairs and mobility devices supported inclusivity so that all residents could engage in gardening activities.

- Implementation and sustainability of the gardening program and activities require collaboration among multiple stakeholders.

Introduction

Social isolation and loneliness in long-term care facilities in Canada are reaching epidemic proportions.Footnote 1 Individuals who are socially isolated (socially disconnected with small, infrequent interactions with others) and lonely (subjective perception of lack of social relationships) are one of the most vulnerable social groups in Canadian society.Footnote 2Footnote 3Footnote 4 An estimated 12% of Canadians aged 65 years and older report social isolation, while 24% reported low participation in social activities including recreational, sports, volunteering and friendship activities.Footnote 5 Although social isolation and loneliness are separate constructs, it is important to examine them together when trying to understand the social context of older adultsFootnote 3 as the people experiencing both social isolation and loneliness are more likely to experience psychological distress and gaps in social supports networks.Footnote 4

With improvements in health care services and increases in life expectancy, the number of Canadians living longer with multimorbidities continues to grow.Footnote 6Footnote 7 While most individuals, including those with complex care needs, prefer to live independently in the community, entry into a long-term care facility can be a necessary option when the need for support requires a level of care that can no longer be met by personal and community supports.Footnote 8 Long-term care facilities are increasingly becoming places where people with substantial physical and cognitive impairments receive care until death.Footnote 8

During relocation to a long-term care facility, people may become disconnected from friends, family and their community, which can substantially affect their ability to create new friendships and engage in activities within an unfamiliar setting. Risk factors for social isolation in long-term care facilities are experienced at the individual level (e.g. communication barriers, cognitive impairment), systems level (e.g. location of the long-term care facility, availability of staff, types of service provision) and structural level (e.g. social and physical characteristics of the long-term care facility; built design; shared vs. private space).Footnote 9 In this context, social isolation and loneliness can negatively affect the health and well-being of older adults,Footnote 2Footnote 4Footnote 10Footnote 11 with a lack of social networks associated with decline in cognition and increased risk of depression, anxiety and mortalityFootnote 2Footnote 12Footnote 13. Although residents in long-term care facilities may be surrounded by other people every day and have regular contact with staff and others at mealtimes, they may still experience loneliness and/or isolation.

Long-term care facilities face increasing expectations to balance finite resources and necessary provision of personal and health care supports, while also providing person-centred care and facilitating activities that promote meaningful engagement and quality of life (QOL) among diverse resident populations. Meeting person-specific needs of residents who range in needs and abilities, from independent/minimal care to severe impairments/high dependency, poses unique challenges. A one-size-fits-all approach to planned physical, social and recreational activities in the long-term care facility settingFootnote 14 is not ideal as residents may differ widely in what they perceive to be meaningful activities. Matching activities to residents’ individualized preferences can promote a sense of control, empowerment and autonomy and improve QOL.Footnote 15 A person-centred approach can support people to engage in activities they find meaningful and purposeful, and result in improved health and well-being of the person and their support network.Footnote 16

In 2018, one long-term care facility resident shared, with a researcher on our team, their need to connect to nature and their strong desire to participate in gardening activities. This individual felt connection to nature, having lived all their life on a rural property, gardening and growing their own food. They described feeling disconnected from nature since transitioning into the long-term care facility, and how this had negatively affected their mental health and well-being. Gardening programs did not exist within their long-term care facility at that time; opportunities to spend time outdoors were also limited, especially during long, harsh winters.

Contemporary qualitative research has reported on older adults’ pleasure and enjoyment when they are in a natural environment.Footnote 17 Studies have demonstrated that an increase in exposure to a natural environment is associated with a decrease in psychological issues in older adults.Footnote 18 Gardening has been shown to promote overall health and QOL, including physical fitness and strength, fall prevention, cognitive ability, socialization, pain and stress reduction, and improved life satisfaction and self-esteem.Footnote 19Footnote 20Footnote 21Footnote 22Footnote 23 Yet, current understandings of older adults’ sensory engagement with the natural environment remain under-researched.Footnote 17

In response to the great and immediate need to address the mental wellness and psychosocial needs identified by the long-term care facility resident, our team of long-term care facility residents, dietitians, researchers and staff co-designed a gardening pilot program as a means to provide opportunities for meaningful engagement and to potentially reduce social isolation and loneliness.

Methods

Study location

This study took place at a medium-sized (100+ beds) assisted living and long-term care facility in a northern, geographically isolated, medium-sized city (population <100 000 people) in a province in western Canada, in 2019. The facility has various outdoor courtyards and protected garden areas, but before this program started, these spaces were not widely used.

Project design and research

This project was co-created in partnership with seven long-term care facility residents, four of whom had created a small gardening club, along with researchers, allied health care providers, nursing management and trainees.

With the support of a research assistant, gardening club members gathered information from online resources, academic literature and other care facilities to learn if and how long-term care facilities can offer horticulture/gardening programs. They found limited horticulture/gardening programming in Canadian long-term care facilities, with only a handful offering gardening programs year-round and few reporting that they had employees with any training in horticulture therapy. Long-term care facilities more commonly offered access to passive nature and gardening activities, such as nature walks, visits to outdoor gardens and greenhouses, and enjoying indoor plants located in shared spaces and residents’ rooms.

Planning and design

During the planning stages, residents identified challenges related to declining health and changes in function that affected their abilities to engage in gardening. These challenges included physical limitations (inability to lift or grasp garden tools) and vision and mobility impairments that prevented them from being able to get outdoors to enjoy the natural environment. In particular, poor physical health contributing to walking and mobility challenges acted as a barrier to enjoying nature.Footnote 24 Access to adaptable tools was identified by residents as necessary to support residents’ involvement in gardening activities.

Based on the early planning, four wooden raised-bed vegetable gardens were placed in an outdoor courtyard space at the long-term care facility (Figure 1A–1D) and an indoor hydroponic tower garden was situated in the entrance to the building (Figure 1E).

Figure 1 - Text description

Figure 1A-1E consists of five photos showing the outdoor raised beds and hydroponic gardens.

Figure 1A depicts empty raised beds in a courtyard prior to planting.

Figure 1B is a close-up of raised beds at the time of planting in a courtyard showing the variation in height of raised beds for those who may be standing (left) and seated in a wheelchair (right).

Figure 1C depicts a raised bed garden planting party.

Figure 1D is a close-up of a planted raised bed.

Figure 1E is a close-up of the hydroponic tower garden.

To complement the opportunities for hands-on gardening, a four-month activity and educational program was offered (see Table 1 for the schedule and list of activities). These activities were chosen by the gardening club members.

| Season | Week no. | Activity | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spring | 1 | Initial planting | Seeds started for hydroponic tower garden Set up of hydroponic tower |

| 2 | Opening event – Garden planting party | Residents, staff and research team members joined together to plant outdoor raised beds Attendees planted seeds in small pots to care for in their rooms Attendees enjoyed ice cream treats |

|

| 3 | Hydroponic tower care presentation | Master gardeners from local botanical society gave an educational presentation on hydroponic gardening and maintenance of the tower Residents and research team planted seedlings in the hydroponic tower |

|

| Summer | 7 | Salad creations | Harvested greens and edible flowers from hydroponic tower Harvested vegetables and sprouts from outdoor raised beds Gardening club members prepared, shared and ate salads |

| 8 | Drying teas | Residents harvested plants and prepared to dry them ahead of fall tea party | |

| 9 | House plant care presentation | Master gardeners from local botanical society gave an educational presentation on caring for houseplants | |

| 10 | Fairy garden workshop | Community gardeners led an interactive activity where residents created small fairy gardens for their rooms | |

| 11 | Smoothie making | Attendees made and consumed smoothies from vegetables and fruits harvested from hydroponic tower and outdoor raised beds Activity led by dietitian and recreation staff |

|

| 12 | Garden summer picnic | Gardening club members prepared and enjoyed eating salads from vegetables from the hydroponic tower and outdoor raised beds | |

| 13 | Growing microgreens | Master gardeners from local botanical society gave an educational presentation on growing microgreens | |

| 14 | Putting the gardens to bed | Attendees and research team members harvested the remaining plants and flowers Raised beds prepared for winter storage |

|

| Fall | 17 | End-of-season tea party | Garden club participants showcased their photovoice activities Attendees sampled a variety of teas made from dried leaves, flowers and plants grown in the hydroponic tower and outdoor raised beds |

At the initial garden planting party, residents, research assistants and staff planted a variety of vegetables (e.g. kale, cucumbers, snow peas), herbs (e.g. dill, oregano, cilantro) and flowers (e.g. pansies, violas). These plants were identified and chosen by the gardening club members.

The smoothie making and tea party activities, led by long-term care facility dietitian (EB) in partnership with recreation staff, were designed to safely include individuals with swallowing difficulties (e.g. dysphagia) or dental concerns.

In addition to these formal events, the residents, research assistants, volunteers and staff spent many hours in the garden.

Ethical considerations

The study underwent harmonized research ethics review (#H19-01250-A002). While all residents and long-term care facility staff were invited to make use of the garden spaces and to attend gardening activity programming, those who chose to participate in surveys and focus groups were required to provide informed written or verbal consent. Recreation staff identified which residents were able to give consent. As a result, the number of residents who attended and participated in activities exceeded the number who provided feedback.

Data collection and analysis

A multimethod participatory research design, including the use of descriptive surveys, focus groups and photovoice, was adopted for this pilot study. Through this approach, a combination of quantitative and participatory qualitative methods was employed to glean insights on a complex health issue. Each method provided a unique exploration of engagement in nature-based gardening activities. In concert with the multimethod approach, findings were integrated later in the analytic process.Footnote 25 In addition, team members were regularly available onsite for residents to share their insights and provide feedback into the research process and outcomes, which was documented in field notes.

Descriptive surveys

At the start and end points of the study, respondents completed, anonymously, a descriptive survey of background information (age, sex, length of time residing in the facility) as well as experiences and interests in gardening. The Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS-5) screener was used to determine possible depression;Footnote 26 a score of two or higher on the five-item scale indicated potential depression.

Survey data were considered valuable to understanding the characteristics and perspectives of the participants with respect to depression and loneliness. The small sample size limited our abilities to measure individual change in scores over time, so only descriptive statistics of aggregate scores are provided. As some participants did not provide responses to all the questions, the respective percentages have been calculated based on those who did respond to that question. Descriptive statistics (sample percentages) were calculated using Microsoft Excel 2016 (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA, US).

Focus groups

A total of 19 people—including long-term care facility staff (n = 10) and residents (n = 9)—participated in three staff focus groups and two resident focus groups. The focus groups varied in size from 4 to 7 participants. They were run as “town hall” meetings to determine insights and experiences related to the gardening intervention.

A qualitative description approach, guided by Sandelowski,Footnote 27Footnote 28 was applied to analyze focus group transcripts. This is a flexible and pragmatic approach that supports in-depth investigation of participant experiences within the naturalistic context. The qualitative descriptive approach seeks to understand phenomena from the perspectives of participants and seeks to generate straight descriptions of phenomena by staying as close as possible to the participants’ words.

Researchers took an inductive thematic approach by cleaning transcripts (editing lightly to ease readability), reviewing for accuracy and then reading closely to become familiar with the data before coding and organizing words and phrases into a codebook of themes. Coding was conducted manually, and segments of text were highlighting and coded using Microsoft Word 2016 (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA, US). As analysis progressed, codes were grouped to form themes and illustrative quotes organized using a codebook. Throughout the analysis process, the team met to discuss the emerging codes and themes, working to clarify and refine these over time. This strategy captured a rich account of participant experiences while also remaining close to the participants’ words.Footnote 27Footnote 29

Photovoice

Photovoice was used, in addition to the focus groups, to engage more deeply with gardening club members, co-create research and centre members’ voices and perspectives throughout the research process.Footnote 30 Photos are valuable for promoting discussions about important topics within a community and to reach policy makers.Footnote 31 As a social process, the generation of grassroots participation through photovoice has been shown to empower individuals.Footnote 30 The use of pictures as self-expression can be enlightening and empowering, especially for people experiencing cognitive loss.

Five residents were recruited to participate in the photovoice activities. Participants used their own devices, or were provided with a camera, to take photos to document their experiences in the gardening project. While most were able to take photos independently, to remain inclusive and respectful of the varying degrees of physical abilities, residents could also opt to direct a research team member to take photos for them.

Participants shared between three and four photos at each of the focus groups, engaging in discussions using the “SHOWED” mnemonic.Footnote 32 SHOWED follows a series of six questions: S (“What do you SEE here?”); H (“What is really HAPPENING here?”); O (“How does this relate to OUR lives?”); W (“WHY does this problem exist?”); E (“How can we be EMPOWERED by this?”); and D (“What can we DO about it?”). Insights were generated collectively and detailed field notes were recorded and analyzed descriptively.

Results

Descriptive survey results

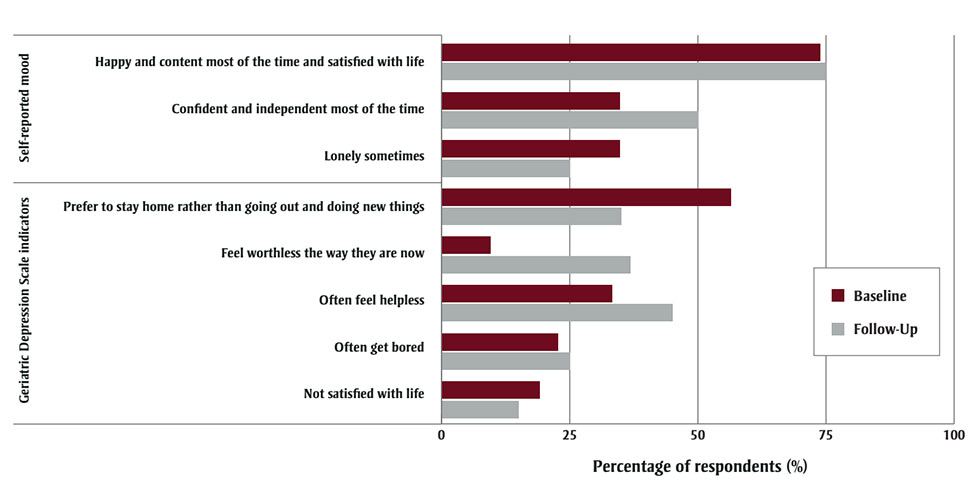

At the initial raised-bed planting event, 23 residents (n = 19 women; mean age 83.2 years, range 59–99 years) completed the baseline survey. Respondents reported living in the facility for between less than 1 year and 14 years, with the average length of time 3 years and 3 months. Nearly three-quarters of respondents (n = 17/23) felt happy and content most of the time and satisfied with life; about one-third (n = 8/23) reported feeling confident and independent most of the time. An equal proportion (n = 8/23) reported feeling lonely sometimes (see Figure 2).

Figure 2 - Text description

| Indicators | Follow-up | Baseline | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Geriatric Depression Scale indicators | Not satisfied with life | 15% | 19.1% |

| Often get bored | 25% | 22.7% | |

| Often feel helpless | 45% | 33.3% | |

| Feel worthless the way they are now | 36.8% | 9.5% | |

| Prefer to stay home rather than going out and doing new things | 35% | 56.5% | |

| Self-reported mood | Lonely sometimes | 25% | 34.8% |

| Confident and independent most of the time | 50% | 34.8% | |

| Happy and content most of the time and satisfied with life | 75% | 73.9% | |

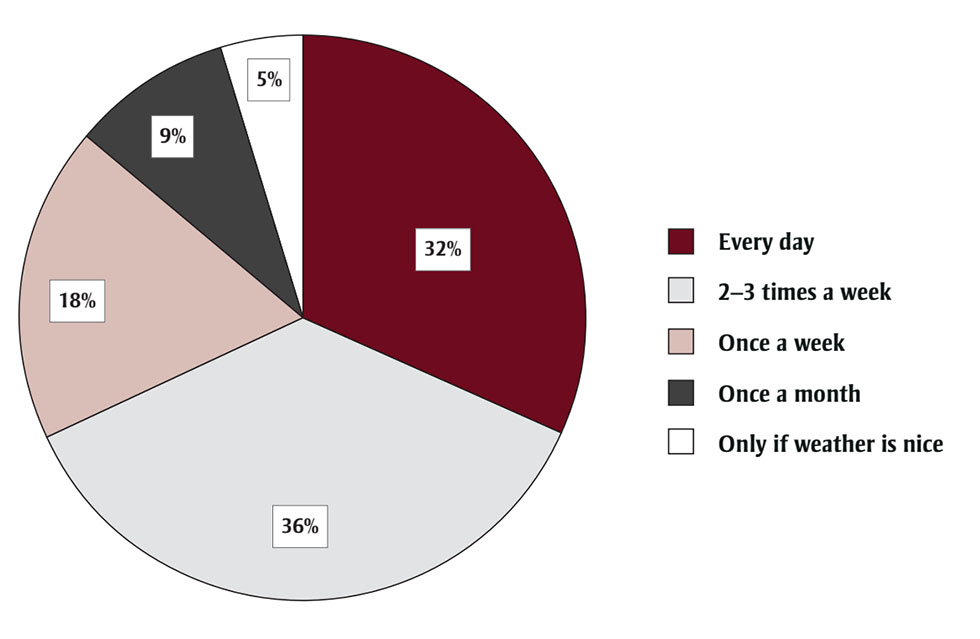

More than half of respondents (n = 11/21) exhibited signs of depression (GDS score >2) (Figure 2). Most respondents (n = 21/23) preferred to go outside; however, less than one-third (n = 7/22) reported going outside daily (Figure 3). Four-fifths (n = 17/21) reported that they enjoyed gardening. When asked what aspects of gardening they enjoyed the most, respondents said that they liked watching the plants grow from small seeds and being harvested, noted joy in being able to eat what they grew and described the advantages of the gardening environment, including being outside in fresh air and being able to “get their hands dirty in the soil.” Respondents expressed interest in actively participating in the planned gardening activities, hoping to work the soil, weed, sit in the gardening environment, watch the plants grow and harvest the vegetables.

Figure 3 - Text description

| Frequency | Percentage of residents (n = 22) |

|---|---|

| Every day | 32 |

| 2–3 times a week | 36 |

| Once a week | 18 |

| Once a month | 9 |

| Only if weather is nice | 5 |

At the end-of-season tea party, 23 residents (n = 21 women; mean age 83.2 years, range 58–99 years) completed the follow-up survey. Three-quarters of respondents (n = 15/20) felt happy and content most of the time and satisfied with life; half (n = 10/20) reported feeling confident and independent most of the time; one-quarter (n = 5/20) reported feeling lonely sometimes. More than half (n = 10/19) exhibited signs of depression (GDS score >2); nearly half reported feeling helpless (n = 9/20); over one-third reported feeling worthless the way they are now (n = 7/19) (Figure 2).

Respondents found meaning and joy in getting their “hands in the dirt,” watching plants grow, getting outside, socializing and connecting with others, and reminiscing about past outdoor activities such as gardening when they were younger. About half reported discussing the gardening program activities with other residents (n = 11/20) and with their family and friends (n = 10/20). Almost all (n = 15/17) hoped to see the program continue.

Photovoice showcase

At the end-of-season tea party, photovoice participants presented photo displays that included phrases and words the residents associated with the photos. Examples of the photos and the meanings described by photovoice participants are shown in Table 2.

| P8, Female, Resident | |||

|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

P8 said that this photo reminded them of growth, representing the process from seed to vegetable, and attainment of a desired result. Seeing “mother nature at work,” even for a short time, led to the participant feeling grateful for the opportunity: “We weren’t just fooling around, we were actually trying to grow something edible!” |

P8 took this photo two days after planting alfalfa microgreens. They saw the change from morning to afternoon in the same day, sharing their joy in the process of capturing a photo of something they were working on: “I was watching it day by day and knew how quickly it grew.” |

P8 shared how this photo shows new growth and old growth together. Being able to grow outdoor plants indoors brought P8 happiness and pride. P8 noted that hydroponic tower gardening was clean, was something that anyone could do and that it allowed growing things all winter long. |

P8 took this photo when a butterfly landed on their plate during an outdoor gardening activity. When reflecting on the photo’s beauty, they noted the comparison between the vegetables and the butterfly: “We don’t normally invite butterflies to our food, but in that case, it was very nice.” P8 emoted how looking at and showing the photo elicited strong feelings of gratitude and amazement: “We need to eat more food outside! Picnic more often!” |

| P1, Male, Resident | |||

|

|

|

|

|

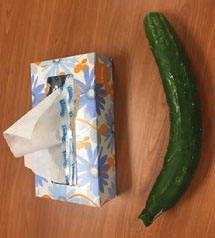

P1 noted that the cucumber in the photo represented a sense of accomplishment and life. The tissue box was placed beside it to show its size. P1 reflected on the meaningfulness of watching a seed grow into a plant that eventually produced a big, edible cucumber: “It made me feel good about myself,” and was a reason to get out of their room. P1 said that the cucumber was a good conversation starter, noting that it “kept me busy. Everyone was asking me how my cucumber was growing.” |

P1 described how watching plants grow amazed them, especially what can be grown in water. P1 described how looking at the hydroponic tower garden relaxed them and gave them a purpose for leaving their room. P1 also described purpose in going to look at the tower, seeing the changes overnight: “It means a lot to me.” The tower also served as a valuable topic of conversation. |

P1 described how gardening made them feel “useful and engaged with life.” They found that watching something grow elicited feelings of meaningfulness, sharing that this made them feel like they were doing something. P1 shared that the meaningful activity of “going out there brightens my day up. |

When reflecting on this photo, P1 described the power in observing the plants’ life cycles and growth. They felt accomplished in their role leading the watering of the garden and pride seeing the success of the raised beds. P1 shared how this photo represented the value of gardening and how it “got them going and doing something instead of procrastinating.” |

| P4, Female, Resident | |||

|

|

|

|

| P4 focussed on the meaningfulness of “getting their hands dirty.” The participant described how the earth and nutrients represented the starting point for the whole garden as the foundation of life and growth. They described their experiences and feelings of pleasure, joy, happiness and fulfillment. P4 described the beauty and satisfaction they found in pushing one’s limits, both through gardening and by taking pictures. | Describing this photo, P4 reflected on the devastation that plants can experience, noting, “the plant is still living and happy.” They were interested in the shapes the bugs make, connecting that to disappointments and anxieties that are a part of life. Although the plant had “been through a lot,” P4 emphasized that the plant is still “growing and winning … it’s still smiling too.” They felt this reflected the reality of life coming to an end and feelings of thankfulness for that life. | P4 vividly described the beauty and loveliness watching how “the dew makes the leaves shimmer.” Further, they described how the leaves were “happy” as the dew stays for such a long time. They described feeling fascinated and excitement, noting “I’m drawn to it.” |

P4 found it interesting to see what a big root system the plants have inside the hydroponic tower. To them the roots symbolized death but not sadness. “We’re on the same path as the plant, our life is coming to an end.” They described the complexity long-term care facility residents experience in their lives, comparing that to the long roots and incredible bodies, each with their own interesting pattern and design. |

Focus group analyses

Analyses of data from the five focus groups—three with long-term care facility staff (n = 10) and two with residents (n = 9)—generated seven themes: finding meaning; building connections with others through lifelong learning; impacts on mental health and well-being; opportunity to reminisce; reflection of self in gardening activities; benefits for staff; and enthusiasm for the program to continue.

Finding meaning

Residents described the profound impact that engaging in the gardening project had on their daily lives, giving them a reason to wake up, providing opportunity for meaningful contribution to the other residents and community within the facility, and in the joy of fostering and caring for something that grew and developed over time. Residents described how active engagement in gardening activities made them feel valued. One resident noted, “It makes me feel useful, like I’m doing something, helping someone … got me going and doing something instead of procrastinating … I went out every day and checked on the cucumber and that got me out and got me going.” [P1, male resident]

Residents shared how the physical connection to nature through gardening led to feelings of satisfaction from getting their hands dirty in the soil and warmth in watching what they planted as seeds grow into vegetables and flowers.

They’re so pretty and they smell so nice. They really do. Everybody commented on my morning glories, so that’s nice. Makes other people happy too. Earth is so… it feels good in your hands. It just makes you feel good to put your hand in the earth and feel it. [P4, female resident]

The long-term care facility staff echoed this quote, observing decreased boredom, increased engagement and increased sense of connection, joy, pride and ownership among residents who participated in the gardening activities. The staff also noted the residents experiencing the joy of meaningful engagement with the gardens by watching the plants grow. For some, the presence and awareness of the gardens fostered the opportunity to get outside.

I find this program meaningful to the residents, yeah. I think it’s a good opportunity for them to be outdoors, doing stuff. … imagine like how months in a year and they’ll just be indoors or doing stuff. I find that a lot of us, you know, if they get out and do something in their yard or in the garden, I think that’s a break from the monotony. [P5, male staff member]

Gardening at the long-term care facility also fostered a sense of interpersonal connection and community cohesion. The respondents saw the value in the meaningful engagement between residents, between residents and staff, and between residents and visiting family and friends as a result of the gardens. Many described how taking part in the program enabled them to build new connections and strengthen existing bonds.

It was very positive, just to even see them out there with their hats on and checking the herbs. … I’m in the main office and I could see families just kind of peek through the doors, and when it was nice and sunny, they would grab their loved ones, and just even to walk or push them in their wheelchair around the gardens was, to me, like you say [it] was satisfying and it was something different that they were doing. Because they had something to look for, they had something, not that they just had a flower, they were looking at, “oh, has the lettuce grown? Oh, look at that” … like just even the talk amongst them was very positive, that I witnessed. [P6, female staff member]

The gardens led to conversations that may not otherwise have occurred, connecting residents with a common interest.

I know it’s opened a lot of conversation already. Different people ask me about what’s going on. ‘Cause I know different people see me going to the garden all the time. … Then they ask questions and call me “Mr. Gardener.” I mean that’s why I feel I accomplished something. I feel right at home. [P1, male resident]

The long-term care facility staff described how important it was for residents to feel part of a group with a shared focus and engagement in group conversation and activity: “There’s a sense of belongingness and commitment. ‘Cause they feel part of a community. They feel valuable because there’s something they can contribute even if it’s in their own little ways.” [P5, male staff member]

I think they feel that “I belong to something,” because I mean let’s face it, in the long-term facility, there’s not much going on, you know. Other than some recreation programs. And a lot of these folks don’t have families to take them out, so I think for them to be part of something like this, it makes them realize they are worth more than what they think they are. Because they are belonging to something. [P6, female staff member]

The residents actively involved in the gardening club put stickers on their doors to let others know that they were leading gardening activities. These stickers sparked further conversation: “The stickers on their door, like it’s a little bit like a pride, ‘I’m a garden member!’ When I asked one of the residents out there what does that mean, she was very proud to tell me.” [P7, female staff member]

Residents also found the photos they took as part of the photovoice activities useful for showing to other residents, family and friends as proof of their accomplishments in the gardening activities. Taking photos and participating in photovoice activities was new and challenging.

… a lot of plusses for this [photovoice discussion group]. And taking pictures. I didn’t think we’d be doing this. We’re just learning and here we are taking pictures. [Resident Name] takes beautiful pictures you know. We’re pushing our limits and that’s good for us, at our age pushing ourselves into you know, being active and enjoying what we have. What we can still do. To me, anyway. [P4, female resident]

Building connections with others through lifelong learning

All respondents self-identified as lifelong learners. During the co-design process, gardening club members had a strong desire to continue to learn about gardening, even though many had been gardeners their whole life. They were very enthusiastic about connecting with master gardeners from outside of the facility and learning more about the nuances of gardening in the specific region as some residents had grown up in other geographical regions and relocated to the city to live in the facility. This allowed for meaningful conversation about a shared topic of interest with new connections.

I think it’s fantastic! It brings the whole… the city, the botanical society together… talking to the mayor, and we’re connected with all the gardeners in [City Name], like the big group gardeners, they come in and give us talks on different things. Isn’t that nice? [P4, female resident]

Residents, including those actively engaged in the gardening activities, embraced the opportunity to learn and experiment with new things. One described great pride in their accomplishments: “Made us all feel a little better about ourselves.” [P8, female resident]

I’m very proud of what the display is. I’m very proud of what we did for the year. I think we accomplished a great deal and I’m very proud of it. … Expands it, enriches us, and it’s good for your heart that we can still contribute. [P4, female resident]

One resident also described how having the photos supported him in overcoming his shyness and engaging more with others, which led to greater confidence when opening up and participating in discussions.

[The photos] show what we’re doing, accomplishing. And sharing, and I tell people what I’m doing. And I find it easier if I have a picture. I can talk. I can explain what I’m doing. It’s easier for me … Yeah, I got to meet new people ‘cause they were always asking me questions. Everybody knew I was the gardener. Sit at coffee time and talk, usually one or two will ask me how my garden is doing. It’s a great project. [P1, male resident]

Increased conversation and engagement with others led to a sense of accomplishment, confidence and personal growth: “It gives you a feeling of being able to do something. It feels good. It really … it’s not very easy to grow cucumbers. And it just made me feel good. Wow.” [P1, male resident]

Engaging in gardening activities, from co-design of the program, through deciding what to plant where in the gardening beds, searching together online and talking to experts about solutions for overcoming bugs, residents were invigorated and encouraged to learn and do more. As residents were able to find answers to their questions, and see the plants continue to grow, they reflected on the impacts that had on their confidence: “[It gives us] a lot of confidence in ourself that we had an idea and we brought it to fulfillment and we’re just seeing that it really, it’s really working.” [P4, female resident]

Impacts on mental health and well-being

Residents used a variety of words to describe the effects of the gardening program and how it made them feel.

Isn’t that just charming? ... It was just magical, really … I see beauty, I see art, I see design, I see excitement, interest. I see love, caring. … It gives me a calm, good feeling—warm feeling to go in the garden and relax. I think about the garden club, me going out there, forget about everything else that was going on and I was calm. Just go out there and look at some …, just relax. [P4, female resident]

The top 75 descriptive words are represented as a word cloud in Figure 4. The residents perceived the garden to be a happy place and an escape from daily routines. The long-term care facility staff also reported this, describing the effects they saw on residents: “I think this is a positive program for them, for sure. It’s meaningful and it’s something for them to, as she said, look forward to every day.” [P5, male staff member]

Figure 4 - Text description

Residents used a variety of words to describe the effects of the gardening program and how it made them feel.

Accomplished, achievement, active, adored, amazing, anticipation, appreciate, art, autonomy, awe, beautiful, beauty, belong, better, brightens day, brighten life, brightens me, calm, caring, challenge, change, charming, clean, colour, commitment, committed, communicating, complex, confidence, connected, connection, cool, courage, curious, cycle of life, death, delicious, design, development, different, dream, earth, easy, effort, end of life, energetic, engaged, enjoy, enriching, enriching, exciting, exciting, experience, explain, familiarity, Fantastic, fascinating, feel it, feel valuable, focus, fresh, friendships, fulfilment, fun, fundamental living, gives, glad, glows, goal, good, gorgeous, grateful, great, growth, happy, heart, important, incredible, independence, interest, interested, interesting, invested, involved, joy, joyful, keep me going, knowledgeable, learned, learning, life, life changing, life giving, light up a room, like, liked, lot of work, love, loved, lovely, magic, magical, meaning, meaningful, means a lo, memories, mental care, mental health, motivation, my heart, mystery, neat, new, nice, opportunity, overwhelming, passion, peaceful, phenomenal, pleasing, pleasure, positive, precious, pretty, pride, productive, proud, purpose, pushing our limits, pushing ourselves, reality, relax, reluctant, rewarding, right at home, sad, safe, satisfying, sensitive, share, smiling, smiling, smitten, spontaneous, spread our wings, striking, success, sunshine, supportive, surprised, suspense, sweet, takes your breath away, talk, team effort, tried, uncertainty, unexpected, unique, useful, variation, warm feeling, well, wonderful, wow.

Figure 4 represents a word cloud containing 75 words of varying sizes depending on how frequently they were used by the residents to describe the gardening program. The most prominent words are: good, nice, exciting, interesting, enjoy, accomplished, proud, growth, wonderful, positive, happy, life, fun.

Note: The size of the word corresponds to the frequency with which the word was used: the larger the print size in the cloud, the more times the word was used.

Residents involved in the gardening club perceived the gardening program to be a “mature” activity that engaged them intellectually, physically and socially. The educational components and connection with community gardening leaders differentiated their role from participation as an activity/program attendee to being actively engaged in the co-design, prioritization and selection of educational and activity program components. Residents involved in the gardening project felt great pride in being able to contribute their experiences and to talk about, on an equal level, their engagement in the program. This shifted the dynamic of power as the residents took ownership of this project. The long-term care facility staff recognized this when interacting with residents, for example:

[Resident Name], up on the [Floor Number], she really enjoyed it. She thought it was really cool that there was something, like a program that was mature in the way that it wasn’t like patronizing them, it was something that was like necessary, and yeah, just more mature activity. [P7, female staff member]

Opportunity to reminisce

Conversations about the current gardening activities sparked conversations about past experiences. Residents shared positive memories of gardening when they were younger and of family and friends. One participant shared fond memories of their mother and how they used to garden together, while another participant shared vivid descriptions of their past home and gardens:

Brings back, flood[s] memories back, of before. Reminds me of the first house we had, we had neighbours and there were buildings too. It was an old house, an old farmstead we bought, I had them gut it, and rebuilt it and it’s just beautiful … Yeah, memories. I think that’[s the case] for the other people too. [P4, female resident]

Facility staff also observed that the gardens prompted reminiscences, bringing back memories for many residents who grew up in rural areas, of being outside and growing things.

I think, for me, is people got out of their rooms more because they had a purpose. They had another purpose, and even listening to them sometimes—you know when we’re having breaks—it took them back … to especially people that were raised on farms, and we have a lot of those folks and it took them back to those days, you know. And I think my wish was to have that area garden, vegetable garden, all of it. [P6, female staff member]

Reflection of self in gardening activities

Discussions of photos showing the root system of a plant and showing how a bug had eaten through the leaves sparked thought-provoking conversations about the realities of life, the cycle of life and how the residents could see themselves in the plants they were growing. The residents recognized the beauty in watching “Mother Nature” at work and the reality that the plant is on a journey of life towards death.

It’s reality and that’s just the way life is, right? As long as you can … the plant has obviously been through a lot, but it’s still growing and it’s winning. It’s winning. So, there’s a lot of meaning in that if you read it. And it still looks reasonably happy [laughs]. It’s still smiling too. Well, it’s not really what we want to see, but if you don’t keep your eye on it, that’s what happens. Reality. Reality is always there. Just the way life is. Life does come to an end. [P4, female resident]

The following conversation illustrates the residents’ shared connections of how they identified with the plants they had worked to grow and saw the beauty in their own mortality.

P8, female resident: For that plant it’s the end of life and yet the roots are healthy.

P4, female resident: And we’re on the same path as the plant. Our life is coming to an end too so we can relate that way too. Just the way it’s supposed to be.

Interviewer: Cycle of life.

P4, female resident: Kind of sad, but it’s positive, it’s the way it is. Life … Very complex, our lives, I mean everybody’s life is really complex.

Benefits for staff

Long-term care facility staff reported experiencing benefits from engaging in gardening activities with residents, including helping care for plants, taking residents for a walk and chatting about the plants, and enjoying participating in gardening activities. They noted that encouraging residents to get outside helped provide a more home-like environment. Sharing in activities led to conversation starters and were noted to spark meaningful discussions “[We] enjoyed mint leaves from it, [it was a] conversation starter with residents and other staff. [P11, female staff member]

The required maintenance of the garden was not possible without help from research team members, who obtained and safely stored the chemicals (e.g. fertilizers) necessary to keep the garden healthy. While it was recognized that these tasks could be adopted by the recreation staff, it was noted that recreation staff need to have the capacity and commitment to take on this responsibility and that time demands can be taxing on staff and a barrier to older adults’ use of green spaces.

Enthusiasm for the program to continue

Residents and facility staff alike expressed an interest in continuing the program following completion of this pilot study: “I’d like to see the group kind of get together and talk about what we plan to do for next year. That’s my goal.” [P1, male resident]

To sustain the activities, participants recognized and noted the need to engage more people and were excited to take on this role.

We need more people involved with the garden club and we need to kind of build up the garden club … I think we want to get more people involved, there’s not too many people. Most people I know like gardening. I think it can draw people to come. That’s what we’re hoping for. [P4, female resident]

The facility staff were keen to encourage greater engagement with family, friends and volunteers:

I think once the word gets out, you know, there’s a lot of families, or a lot of residents … that their families don’t come and visit them too often, and I think once the word gets out and says hey, we have this at [Facility Name], I think it will bring in more families. ‘Cause I know the difference when the garden was there, when we initiated the garden and we had a few new residents come in, especially for the first floor, and we mentioned, hey this is, they’re like what? You have that? Can my mom participate? You can tell the excitement. Really, they can go outside and weed. [P6, female staff member]

The interest in continuing to support residents’ engagement in the gardening activities was rooted in the positive value and meaning that participation brought to the residents’ QOL and to the atmosphere in the facility environment. None of the facility staff reported that presence of the hydroponic tower or the raised-bed gardens increased their workload.

Discussion

It can be challenging to create a home-like atmosphere for each individual in the long-term care facility setting, especially when residents previously lived in rural or remote geographical areas. Over time, depression remains a pervasive issue in the long-term care facility setting, which warrants focussed attention. Enhancing opportunities for engagement with the natural environment through indoor and outdoor gardening, as well as nature-based activities, can benefit many residents.

Participation in gardening activities presented new opportunities to reduce both social isolation and loneliness, especially for those looking to “get their hands dirty” and garden through the group gardening club activities. Respondents described how these activities led to interactions and purposeful discussions with other residents and staff. Further, passive engagement with the hydroponic tower and raised-bed gardens may have reduced loneliness, as residents noted their connection to the beauty and atmosphere by simply looking at and being close to nature. This confirms findings from a recent literature review that concluded that older adults derive pleasure and enjoyment from being in and viewing nature, which in turn, positively affects their well-being and QOL.Footnote 17

Long-term care facilities in both rural and urban communities may lack surrounding green space areas, resulting in an increased prevalence of social isolation and loneliness. Residents described longing for nature, especially those who relocated from the countryside where they were close to the natural environment.Footnote 33 Residents may also have limited or no access to gardening and the nature-based activities they found meaningful when living in the community. Thus, nature-based activities may provide a meaningful and impactful way to promote the health and well-being of adults in long-term care facilities.

In northern communities where winters are often harsh and growing seasons short, outdoor gardening may be challenging for beginner and novice gardeners. The built environment may also prevent many from going outside (e.g. doors may be locked or are too heavy for residents to push open and navigate on their own, outdoor spaces may be inaccessible in the winter due to heavy snowfall or ice). Hydroponic technology can be a feasible and innovative way to support connection to nature and reduce isolation year-round, regardless of climate and infrastructure.

The hydroponic tower enhanced opportunities for residents to connect with others. Introduction of this technology offered opportunities for shared learning and encouraged positive interaction between individuals, often acting as a source of discussion for visiting friends and family. Some residents felt more valued through their participation in the planting, growing and maintenance of the tower. This is consistent with existing literature demonstrating that the availability of green spaces generating opportunities for social interaction, elevating the everyday lives of older adults.Footnote 34 Engaging in activities with nature was important for maintaining social connections and self-confidence.Footnote 35

Overall, there existed a sense of accomplishment and pride, as the tower provided year-round access to fresh produce and flowers. Sharing of the plants and flowers also gave residents opportunities for social engagement. The placement of the hydroponic tower in a high traffic area in the hallway of the facility, with seating nearby, further enhanced opportunities for passive enjoyment of the plants. The rapid growth of the plants provided an ongoing topic for conversation for those actively and passively engaged in the gardening activities.

This pilot project demonstrated that a nature-based gardening intervention, including outdoor raised-bed and indoor hydroponic gardens, is feasible and beneficial in the long-term care facility setting. While gardening was embraced by residents, their families and the facility staff, sustainability and safe operation of the gardening sites, including the hydroponic tower, relied heavily upon staff and facility management. Although both residents and staff experienced diverse benefits, it was noted that recreation or other long-term care facility staff must have the capacity and commitment to take on the responsibility. The time demands and complexities involved in maintaining gardens can be taxing on staff and a barrier to older adults’ use of green spaces.Footnote 36 Staff commitment and support is essential for successful engagement of older adults with nature and green activities, and a lack of support can be a barrier for ongoing engagement.Footnote 17

Strengths and limitations

This research focussed on the inclusion of diverse long-term care facility residents in planned and adapted nature-based activities. Adaptations are key when working with an aging population to ensure meaningful participation, including residents’ involvement in co-creation activities. The co-creation process identified many meaningful activities and resulted in several revelations for the research team. Further, adopting photovoice as an approach for gardening club members to engage more deeply was a powerful way to mitigate social isolation as it enabled individuals to reflect on strengths of the gardening activities and promoted discussions.

However, despite initial enthusiasm, two participants withdrew due to declining health, and a few felt some frustration with using digital camera technology. While cellphones with cameras are common, only one participant in this study owned one.

Further research iterations of the raised-bed and hydroponic gardening project were also disrupted by the COVID-19 pandemic. This resulted in an early pause in the hydroponic tower activities and associated programming; gardening club members were able to continue their raised-bed gardening activities in a more limited capacity.

Finally, our small sample size and inability to link survey responses at the baseline and follow-up periods are limitations. Future research may benefit from the engagement of a larger cohort of long-term care facility residents as well as more systematic screening for depression and QOL. Future research should also seek to gather quantitative data from a larger number of participants to investigate the potential impact of participation in gardening activities.

Implications for long-term care facility settings

Integrating nature-based interventions, including hydroponic and raised-bed gardening, into the long-term care facility setting is feasible and can result in the active and inclusive engagement of residents, along with meaningful conversations among residents and with facility staff. Key learnings include:

- Residents’ participation in gardening activities increases opportunities for social engagement and relationship building between residents and staff, providing opportunities to mitigate social isolation.

- Positioning flower beds and/or hydroponic gardens in a high traffic area with seating nearby and access for wheelchairs and mobility devices supports inclusivity for all residents who wish to engage in gardening activities.

- Implementation and sustainability of the gardening program and activities requires collaboration among multiple stakeholders—residents, care staff, recreation staff and dietitians—to co-create a gardening program that is tailored to the long-term care facility context.

- Access to outdoor raised-bed gardens may require support from facility staff/families.

Conclusion

Participation in gardening activities was a valued and meaningful activity for long-term care facility residents and can help provide opportunities for meaningful engagement with others. Active and passive engagement with hydroponic indoor gardening and outdoor raised-bed gardening fostered opportunities for discussion, connection and increased interaction with others, helping to reduce social isolation. In this study, gardening activities helped participants feel connected to nature and the land, helping to reduce feelings of disconnection and isolation in the long-term care facility setting. Of note, connections and interactions between residents and with staff improved, demonstrating the importance of these activities in initiating and sustaining robust connections. When developing and prioritizing activity programming for long-term care facilities, gardening programs are an important option that can support the socialization, health and well-being of residents.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank all the residents, staff, families and volunteers as well as community leaders who were involved in this project. We wish to thank Emma Rossnagel for her support in editing the final manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

Kelly Skinner is an Associate Scientific Editor with the HPCDP Journal, but has recused herself from the review process for this paper. The authors have no other conflicts of interest to declare.

Financial support

Grant support for this work was received from the Northern Health-PHSA-UNBC seed grant as well as from the BC Support Unit-Northern Centre seed grant programs.

Authors’ contributions and statement

All authors actively contributed to this project.

SF, DB and KS were involved in all aspects of the project, from project design and conceptualization through to analysis, drafting and revising of this paper.

EB was involved in project design and data acquisition.

ML was involved in acquisition of the data and drafting the paper.

GB was involved in acquisition and cleaning of the data.

TW was involved in analysis, drafting and revising this paper.

The content and views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Government of Canada.