Preparing for Climate Change: Canada’s National Adaptation Strategy (Discussion Paper - May 2022)

Overview – The urgent need for adaptation action

People living in Canada are already witnessing and experiencing devastating impacts of climate change. Canada's climate is warming two times faster than the global average, and three times faster in the North. Across the country, the impacts of climate change are already affecting our communities, economy and environment.

The National Adaptation Strategy is an opportunity to establish a clear framework for action to achieve climate resilience.

This discussion paper allows us to hear from you and people across Canada about what you think should be the priority actions over the next five years to prepare for climate change. This will inform the outcome of the National Adaptation Strategy which will be released by the end of the year. The proposed principles and objectives in this discussion paper represent the result of conversations to date with experts, government officials, and Indigenous representatives.

Long description

The flowchart shows the timeline of the National Adaptation Strategy. The project began with a Strategy development Forum, then there was targeted engagement with key stakeholder and partners, then expert Advisory Tables were created to help develop transformational goals and medium term objectives. From here, partners and key stakeholders were engaged, followed by public engagement on short term objectives. By late summer/fall 2022, a first draft of the Strategy will be released, and by the end of 2022, the Final Strategy will be released.

We want to hear from you

We want to hear your experiences with the effects of climate change, your priorities for action, and your thoughts on this discussion paper. Your input will strengthen the Strategy and ensure that targets, milestones and actions reflect the priorities of people living in Canada.

In addition to questions throughout the document, consider sharing your views on the questions below.

- How are climate change impacts (e.g., permafrost thaw, flooding, sea-level rise, fires and heatwaves) affecting you, your community, your workplace, or your organization?

- What do you think are some of the biggest risks that climate change poses to people living in Canada?

- What do you think we need to do to be better prepared?

- What actions would help you, your community, workplace, and organization to better prepare for climate change impacts?

- Do you agree with the ideas in this discussion paper? Why or why not?

How to participate

The public consultation period for the Strategy will be open for spring and summer 2022, with the release of the Strategy planned for fall 2022.

Share your views

- Share your ideas and expertise at the May 16 National Adaptation Strategy Symposium and in upcoming workshops

- Provide feedback and answer questions on the Let's talk adaptation website

- Share your adaptation stories on the Let's talk adaptation website by submitting photos or videos of how you and your community are preparing for climate change impacts (e.g., installing community gardens, protecting or restoring a wetland, planting trees to prevent erosion, creating gathering areas for emergencies, etc.).

- Send your written comments by email to adaptation@ec.gc.ca

How Canada's climate is changing

Canada's changing climate is causing deep and lasting impacts on our society, economy and environment. Higher temperatures, shifting rainfall patterns, extreme weather events and rising sea levels are just some of the changes already affecting many aspects of our lives. Changes in climate will persist and, in many cases, will intensify over the coming decades. Understanding these impacts is necessary to reduce risks, build resilience and support sound decision-making.

In the past five years alone, communities all over Canada have lived through unprecedented events. In spring 2022, the Red River Valley and many other parts of central and southern Manitoba experienced some of the highest flood waters on record. In 2021, record-breaking high temperatures caused one of the deadliest heat waves in Canadian history. In Lytton and other communities in British Columbia, this extreme heat was followed by forest fires and then devastating flooding from rare atmospheric rivers, all within a few months. Atmospheric rivers on the east cost washed out roads and bridges, and limited access to essential services in parts of Atlantic Canada. The Ottawa River flooding in 2017 and 2019 both surpassed historic levels. Warmer temperatures in the North are making ice roads – like the Dettah across Yellowknife Bay – less reliable and affecting the supply of fuel, food and building material to many communities.

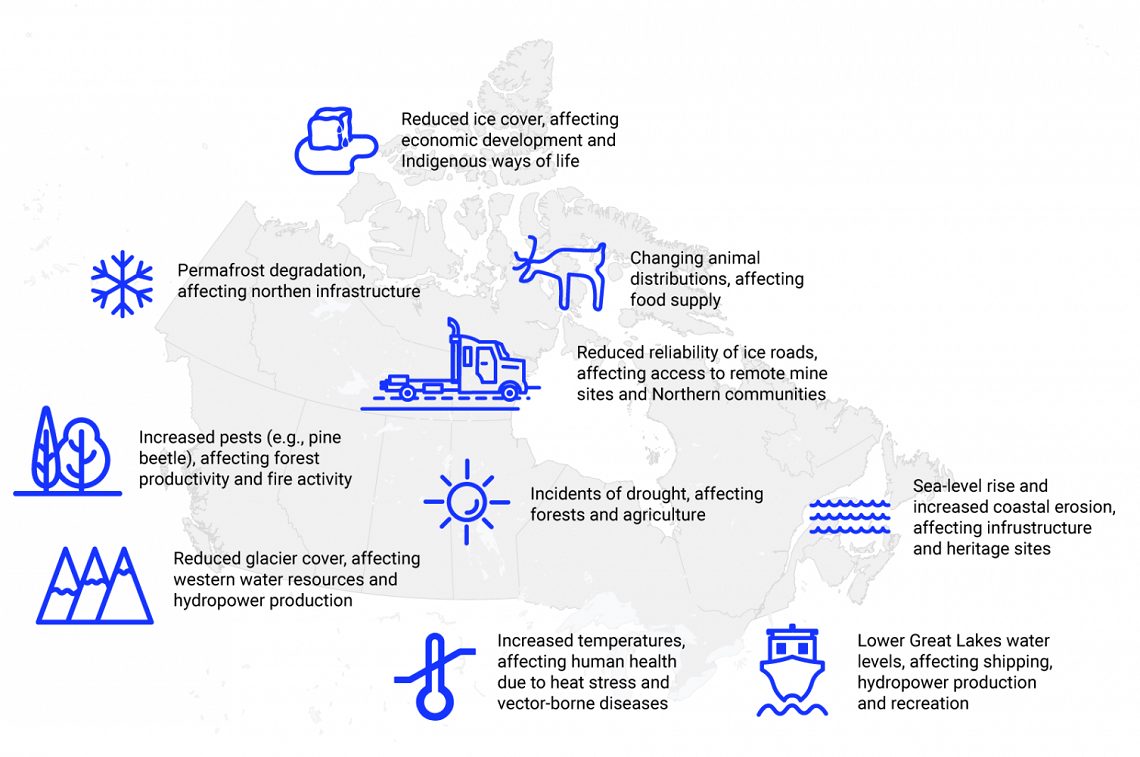

Figure 1: Some of the many regional climate change impacts that people in Canada are already facing.Footnote 1

Long description

A map of Canada with 10 different climate change impacts across the country. These impacts include: reduced glacier cover; increased pests; permafrost degradation; reduced ice cover; changing animal distribution; reduced reliability of ice roads; incidents of drought; increased temperatures; lower Great Lakes water levels; and sea-level rise and increased coastal erosion.

Climate impacts are complex and touch upon almost all aspects of society: emergency services, food production, housing and infrastructure, ecosystems, human health, supply chains and national security. Climate change poses serious risks to the well-being and livelihoods of people and communities.

Extreme weather and climate events like heatwaves, wildfires, droughts, storms and floods are becoming more frequent and intense, and the costs related to recovery after the fact are growing at an almost exponential rate. Heat-related illnesses and vector-borne diseases pose growing risks to health. Slower but pervasive impacts like rising sea levels, coastal erosion, ocean acidification, as well as warmer water temperatures are increasingly affecting oceans, lakes, and coastal ecosystems and communities. Thawing permafrost and declining sea ice coverage are irreversibly altering the land, transportation and ways of life in the North. All of these impacts are changing the natural environment upon which we depend.

These impacts also build upon each other and lead to additional effects such as increased demand for emergency assistance, loss of biodiversity, reduced food and economic security, and increased demands on physical and mental health services. Climate change impacts worsen existing inequalities and vulnerabilities and multiply existing hazards – meaning that some people living in Canada are more at risk or more exposed.

Indigenous Peoples experience disproportionate effects of climate change. Lower socio-economic outcomes, the legacy of colonization (including displacement from traditional territories onto reserve lands that are often more prone to flooding or fire), and a unique relationship with the land are factors that compound the effects of climate change, leading to intensified negative cultural, social and economic impacts for First Nations, Inuit and Métis Peoples.

We must reduce emissions to limit climate change. Temperatures will continue to increase until global net-zero emissions are achieved. While we are all taking steps to reduce our greenhouse gas emissions, our communities will continue to suffer from the effects of climate change. The federal government, along with all levels of government and Canadians, must prepare for the unavoidable impacts of climate change and ensure our efforts and investments support resiliency in our communities.

- How has climate change affected you, your community, your work or your organization?

- What climate impacts are most concerning to you?

- How do you expect climate change to impact you and your community in the future?

Our path to a climate-resilient Canada

What can we do?

What is climate change adaptation?

Adaptation means planning for and acting on the impacts of climate change. It involves being ready to respond to climate change events (reactive) as well as making changes to where we live and what we do before climate change events happen (anticipatory).

People living in Canada can take action to understand how climate change is affecting us now and the risks it will pose for the future. Then we can take proactive actions to minimize risks – this is climate change adaptation.

We can achieve climate resilience by increasing our ability to anticipate and deal with the climate change impacts we cannot prevent. To do this, we must transform how we build our communities, the way we interact with nature, and how we look out for each other.

Climate change does not affect all people in the same way. We must recognize and address the factors that contribute to individual and community vulnerability to ensure that all people living in Canada can prepare for climate impacts. We must take action in a just and fair way so that climate change preparations are widespread and benefits are shared.

What is Canada's National Adaptation Strategy?

The National Adaptation Strategy will advance a shared vision for climate resilience in Canada that will be based on high-level principles and focused objectives. It will provide a blueprint for whole of society action to help communities and residents of Canada better adapt to and prepare for the impacts of climate change.

Who has been involved in developing the National Adaptation Strategy so far?

This discussion paper is based on the views received from targeted and expert engagement since early 2021, including:

- An international peer-learning event in May 2021 was an opportunity to learn about international best practices in the development of national adaptation strategies and action plans. The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, Japan, Germany, and the United States, among others shared their expertise and lessons from their experiences.

- A virtual Strategy Development Forum in June 2021 identified early ideas for a National Adaptation Strategy for Canada. The 60+ participants included representatives from all provinces and territories, National Indigenous Organizations, professional and industry associations, youth organizations, climate service providers, research institutes, municipal and local community networks and other non-governmental organizations.

- Five expert Advisory Tables, launched in fall 2021, provided advice on transformational goals and objectives within five key systems: Health and Wellbeing, Natural and Built Infrastructure, Environment, Economy, and Disaster Resilience and Security. These tables are co-chaired by a federal representative along with one from outside the federal government and included diverse representatives including Indigenous peoples, youth, professional associations, the private sector, environmental organizations, academia, adaptation experts, and others.

- The reports of the advisory tables were shared with officials from provincial and territorial governments and National Indigenous Organizations to get their feedback on the tables' recommendations and what the priorities should be in the National Strategy.

- Discussions with experts and stakeholders have also informed the process so far. This includes an armchair discussion and a roundtable at Globe 2022, where federal ministers heard from those directly impacted by climate change, as well as expert recommendations for urgent adaptation needs in the context of more frequent and severe climate disasters in the country.

Why do we need a whole-of-Canada approach?

As the impacts of climate change touch nearly all aspects of society, we need shared and coordinated action across Canada. We need to work together. The Strategy aims to unite groups across Canada through an integrated approach to understanding and reducing the climate change risks that we can no longer avoid. Coordinating efforts and investments means we can be more efficient and achieve better results for all of us living in Canada. Key groups with a role to play include:

- The federal government, which makes policy and regulatory decisions on national and international issues, creates federal laws and regulations, sets national codes and standards, and has responsibilities related to emergency response and recovery from natural disasters. It provides funding for programs, projects and partnerships to support action and provides important information such as weather monitoring and forecasting, scientific research and analysis, and climate change information and advice.

- Provincial and territorial governments, which have significant influence through their jurisdiction over property and civil rights, which is actioned through land-use planning laws, building regulations, natural resource management, health care systems, and investments in infrastructure – just to name a few. This includes the delivery and design in key areas such as emergency services, environmental protection, health, education, planning, economic development and transport. They also collect data and information and conduct science at local and regional scales that can be used to better understand climate change risks.

- Indigenous peoples and governing bodies, who are leaders, knowledge-holders, knowledge-generators, and stewards of the environment; hold unique rights to lands and territories; and who are advancing self-determined or self-governed actions as keepers of their territories and communities.

- Local governments, which integrate the effects of climate change into decisions such as land-use planning and zoning, water resource management, flood and wildfire risk management, and emergency management; and integrate local circumstances and involve local communities in adaptation efforts.

- The private sector, which is directly impacted by climate change and which can direct investment in adaptation to change behaviours, operations and activities, and develop innovative technical solutions that increase climate resilience and support adaptation action.

- Communities and individuals, who can make informed choices about how they will respond to climate change and have the right to express their values and preferences for how adaptation is implemented to protect their health and safety, including at an individual, household, family or community level.

- Academic institutions, researchers, scientists, non-governmental organizations, which undertake climate adaptation research and action, develop new technology and innovative solutions, and play major partnership roles with all orders of government and other stakeholders and partners when it comes to understanding, evaluating, and assessing the impacts of climate change and how to adapt to these challenges.

Where are we starting from?

The National Adaptation Strategy will build on extensive work on adaptation already underway across the country. Many provinces, cities, communities, companies and organizations have made plans to prepare for the changing climate. The Strategy aims to support existing work and strengthen linkages among strategies and initiatives underway. Some examples are outlined in Annex A.

The federal government has also accelerated its programs and spending on climate adaptation in the past six years. Some of the key federal leadership efforts are as follows:

- Disaster Mitigation and Adaptation Fund (DMAF) to help communities remain resilient in the face of natural disasters triggered by climate change. Budget 2021 recapitalized DMAF with an additional $1.375B over 12 years, introducing a new small-scale projects stream and allocating a minimum of 10% of funding to Indigenous recipients. As of May 2022, DMAF has invested $2.1B to date for 70 infrastructure projects to mitigate threats of natural disasters such as floods, wildfire and drought. Additional funding announcements will occur throughout 2022.

- Natural Infrastructure Fund (NIF) to support projects that use natural or hybrid approaches to protect the natural environment, improve access to nature for Canadians, and support healthy and climate resilient communities. Budget 2021 provided $200M over 3 years for the Natural Infrastructure Fund. The Fund is investing up to $120M in large-scale projects. Select major cities with innovative natural infrastructure strategies have been invited to apply for up to $20M in funding. A small project stream will be launched to support smaller natural infrastructure projects. A minimum of 10% of the overall program envelope will be allocated to Indigenous recipients.

- Wildfire Mapping for areas in Northern Canada at risk of wildfires and work to enhance the capacity of the Canadian Interagency Forest Fire Centre, which is jointly funded in partnership with provinces and territories.

- Flood Mapping objectives, to work with provinces and territories to complete flood maps for higher-risk areas, along with the establishment of a Task Force on Flood Insurance and Strategic Relocation to examine options for low-cost residential flood insurance and potential relocation of residents in areas at the highest risk of recurrent flooding.

The National Adaptation Strategy builds on the commitment to adapt to climate change found in the Pan-Canadian Framework on Clean Growth and Climate Change. The Strategy was identified as a specific commitment in the Strengthened Climate Plan, A Healthy Environment and a Healthy Economy released in 2020.

How will the Strategy evolve?

Long description

A pie chart that shows how the National Adaptation Strategy will evolve over time. The pie chart is divided into three sections: Plan, Implement, and Evaluate. There is also a clockwise arrow around the circle that says "Understand Risks".

As the climate continues to change, our actions to prepare and respond must also change. The National Adaptation Strategy will include a review and evaluation component for the federal government and partners to understand what is working, what is not and how to make adjustments. We will build on achievements and learn lessons from previous actions. This will enable us to identify and understand new risks that climate change will bring and how to adapt to them.

Setting direction

Like Canada's plans to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, the adaptation strategy will also set out short, medium and long-term direction. The Strategy will set transformational 2050 goals to provide a national destination for climate-resilience. It will include 2030 objectives to ensure accountability and progress in the right direction, and 5-year action plans. While we are experiencing the effects of climate change right now, we do not know all the ways that climate change will affect us in the future. Because of this, the action plans will be updated regularly, based on the changes that we observe and our further understanding of what works best.

Informed by an up-to-date understanding of the risks of climate change

The Strategy will be informed by science and knowledge, risk assessments, as well as other diverse ways of knowing such as local and traditional knowledge. Federal, provincial, and municipal governments have all contributed assessments, as well as Indigenous peoples and organizations, the private sector, non-governmental organizations, academics, and other climate change experts. Some examples of these assessments are outlined in Annex B. Recognizing the importance of up-to-date information on climate change risks, the National Adaptation Strategy will require regular review of climate change effects across the country to inform action on what we should do to prepare for these impacts.

Measuring progress

The reporting and evaluation framework for the National Adaptation Strategy will provide a transparent and accessible way to take stock of national progress on adaptation. Monitoring and evaluation will begin with the collection of available sources of climate information, including quantitative, qualitative, and traditional forms of knowledge, through ongoing coordination with partners and key stakeholders. An initial set of indicators and associated targets is under development. In time, regular reporting at the national level will provide information on where efforts are yielding results and where more work is needed.

- What steps are you taking in your community, organization or sector to prepare for climate change and to build resilience?

- Does your community, workplace, or organization integrate climate risks in planning, operations, and management practices? What works best?

- Are you aware of others that effectively consider climate risks in their community, workplace or organization?

A common vision and guiding principles for climate change adaptation in Canada

Our vision for adaptation unites and guides the Strategy's goals, objectives, and actions, and brings partners and stakeholders together in a shared direction.

Vision

All of us living in Canada are resilient in the face of a changing climate. Our adaptation actions enhance our well-being and safety, promote justice, equity, and Indigenous reconciliation, and secure a thriving environment and economy for future generations.

Guiding principles

To support this vision, a series of principles will guide and drive all adaptation efforts advanced by the Strategy. Actions will be evaluated and implemented with a thorough consideration of how they meet these principles.

- Adaptation actions will build on the commitments, plans and actions being advanced by all orders of government, including those by Indigenous peoples.

The Strategy will build on and respect the adaptation actions, commitments, and strategies that are already in place by federal, provincial, territorial and municipal governments, as well as Indigenous peoples.

- Adaptation actions will respect the constitutional, treaty, and recognized rights of Indigenous peoples in accordance with United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous peoples, prioritize the self-determined actions of Indigenous peoples, and advance reconciliation.

In alignment with the principles of the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous peoples and Truth and Reconciliation Commission calls to action, the Strategy will honour Indigenous people's rights to own, use, develop, control, conserve and protect the environment of their lands, territories and resources. It will also respect, above all, the right for Indigenous peoples to choose and advance their own self-determined actions on adaptation. As a result, the Strategy will uphold Indigenous Rights, including those enshrined in s. 35 of the Constitution Act and treaty rights, and be respectful of Indigenous Knowledge and worldviews in their entirety. At the same time, the Strategy would support Indigenous peoples to take adaptation actions in the ways and at a pace at which they choose. The use of the term "Indigenous" acknowledges and recognizes the distinctions-based identification of First Nations, Métis communities, Inuit, and urban and off-reserve communities, and the diversity of cultures, languages, needs, economies, and assets across communities.

- Adaptation actions will advance social, gender, intergenerational equity, and prioritize those populations at greater risk of climate change impacts due to historical and political contexts that have shaped current lived experiences, capacity, and access to resources.

Climate change adaptation requires not only improving the resiliency of critical systems (e.g., health, infrastructure), but also addressing the socio-economic determinants of vulnerability that affect how climate-related hazards will impact individuals and communities. Adaptation measures, when planned with care, through inclusive and accessible processes, and with equity, justice, and anti-racism lenses, can promote equity and lessen disparities. All adaptation measures should account for existing social inequities, and should not exacerbate those inequities or create new ones. Measures should be designed to ensure that those that are at highest risk benefit from the efforts. Equitable approaches recognize that not all groups are at the same stage or have the same needs, and as a result, adaptation actions will look different for different groups. These targeted approaches will help ensure that no group is left behind as we advance whole-of-society adaptation action.

- Adaptation actions will be informed by science, data, Indigenous Knowledge, and other diverse ways of knowing.

Adaptation decisions will be evidence-based and make full use of the latest research, data and practical experience relevant to climate change adaptation. In addition, the knowledge systems and experiences of Indigenous peoples will inform decision-making in line with their knowledge and data sharing practices and principles. Indigenous knowledge systems, including practices, skills and philosophies are critical for adapting to a changing climate.

- Adaptation actions will maximize co-benefits and should avoid maladaptation.

With careful, integrated and coordinated planning and policies, adaptation actions can have many other positive impacts, providing multiple co-benefits to society and the environment in areas such as biodiversity conservation, climate change mitigation, and economic development. For example, growing forests can capture and store carbon released through greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, while improving water and air quality, as well as providing protection against flooding and soil erosion. Adaptation actions should also avoid maladaptation, or unintended negative effects, such as solutions that increase greenhouse gas emissions or contribute to nature loss.

- Adaptation actions will be flexible to climate change and to technology advancement and reflect unique regional and local circumstances including values and culture.

While change itself is certain, some uncertainty will always exist. Canada's climate will change at a speed and scale we have not yet experienced. We expect to see technology advancements and a reduction in greenhouse gas emissions, however the climate will continue to change, even while we work towards net zero emissions. Adaptation decisions need to be flexible and readily adjusted so they can respond to evolving information and knowledge. Different regions of Canada have different adaptation priorities based on their local circumstances and unique risks, so different adaptation options will need to be considered.

- Adaptation actions will support the capacity of communities, businesses, and governments and will include opportunities for two-way information and local knowledge sharing, training, and building capacity.

Continued collaboration and partnerships are vital for building resilience to climate impacts in a way that reflects regional realities. For example, northern and remote communities are witnessing climate change impacts and are aware of the risks, but often lack the resources and capacity to implement solutions. Adaptation actions should include flexible opportunities for two-way information sharing, listening to local knowledge, and building capacity. In rural and northern communities, Indigenous and local knowledge is especially important for adaptation actions.

- Adaptation actions will focus on the most effective use of funding to support emergency preparedness and disaster resilience across the country, while also supporting effective recovery efforts.

A risk-based approach to policy and investments will inform decision-making, focusing on our most urgent challenges and priorities. Funding needs to shift to proactive disaster mitigation and preparedness from primarily supporting response and recovery efforts after disaster strikes. Actions should focus on helping communities across Canada invest in up-front measures to both better protect and reduce the impact of disaster events and damages.

- Does the vision capture what you think we should be trying to achieve? Are any key aspects missing from the vision statement?

- Do you agree with these principles? Why or why not?

- Are we missing any principles for action?

Goals and objectives for climate change adaptation in Canada

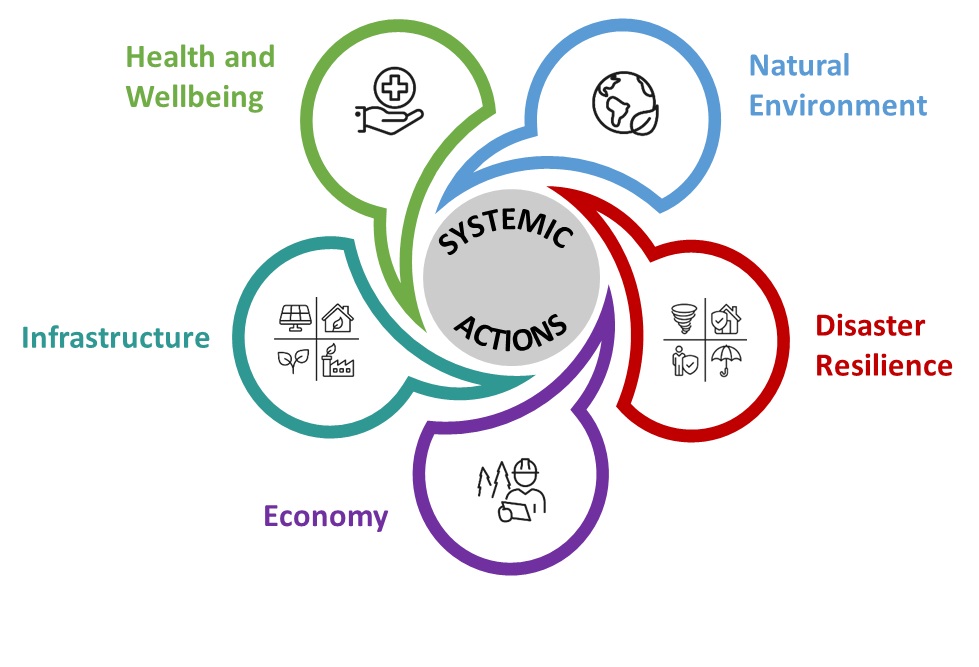

Based on work with partners, stakeholders, and expert advisors, we propose that the Strategy advance climate preparedness across five key systems at the core of our lives and communities: health and wellbeing, infrastructure and the built environment, the natural environment, the economy, and disaster resilience. The Strategy should recognize the connections and relationships among these systems and the climate change risks each one faces.

Figure 2: The five systems of the National Adaptation Strategy.

Long description

A graph that shows how all the systems of the National Adaptation Strategy are intertwined. The systems include: Health and Wellbeing; Infrastructure; Natural Environment; Economy; and Disaster Resilience.

What is a "System"?

Systems are defined as a cluster of structural and non-structural elements that are connected and organized to achieve specific objectives. Systems-based approaches look beyond individual assets and consider the interrelationships.

This systems approach will enable the National Adaptation Strategy to address large-scale adaptation opportunities. Through the long-term goals, medium-term objectives and tangible, short-term priority actions, the Strategy establishes a blueprint for ongoing improvements and innovation.

For each of the five systems, the Strategy would set out:

- Challenges that climate change poses for that system;

- Transformational goals (set to 2050, in alignment with Canada's climate change mitigation targets);

- Objectives, which outline specific medium-term milestones (set to 2030) needed to make progress towards the transformational goals;

- Clear actions, which outline priorities for the first five years of the Strategy to enable accountability and focus investments; and

- Highlights of solutions that are already being implemented.

The following sections outline our proposed direction, based on work with experts and partners so far. Please review them carefully – we want to hear what you think.

- Do the goals and objectives for each system capture the full range of action we need?

- Do the goals reflect where you think we need to be by 2050?

- Are there important characterizations/outcomes that are missing in the goal statements?

- Do the 2030 objectives capture where we need to be by the end of this decade? If not, what should be changed?

- Are any key objectives for your community, organization or sector missing?

Disaster resilience

The challenge

Increasing frequency and severity of extreme weather events, like floods, fires, heat domes and other climate-related disasters, are costing billions and putting people, public safety, infrastructure, the environment, natural resources, food production, supply chains and the economy at risk.

A risk-based approach to policy and investments will need to inform decision-making – focusing on the most urgent challenges and priorities. While recovery efforts after climate disasters will be required, spending by the public and the private sectors needs to shift to help communities invest in up-front measures to both protect and reduce potential damages from climate events.

The National Adaptation Strategy will build on the ongoing work under Canada's official disaster risk reduction strategy, the Emergency Management Strategy for Canada (EMS), which was approved by Federal, Provincial and Territorial Ministers in 2019 and articulates priorities to strengthen the resilience of Canadian society by 2030. The objectives listed below build on existing work and targets, and identify opportunities and actions to strengthen Canada's preparedness and readiness to climate-related disaster events. The proposed targets aim to empower, inform, and enable people living in Canada to take the steps they need to address the climate-related disasters within their respective communities. Overall, they call for greater accountability, coordination across sectors, awareness of disaster risk and increased capacity. This includes strengthening our well-being in a way that addresses social, physical and financial vulnerabilities.

The Emergency Management Strategy for Canada establishes federal-provincial-territorial government priorities aimed at strengthening the resilience of Canadian society. It establishes roles and responsibilities, and seeks to guide and support federal-provincial-territorial governments in assessing risks and to prevent, prepare for, respond to, and recover from disasters. There are many links between emergency management and disaster risk reduction, and climate change adaptation. Climate-related hazards, including floods, wildland fires, and extreme storms and weather events highlight these links.

Proposed 2050 goal: Communities and all people living in Canada are better enabled to prepare for, mitigate, respond to, and recover from the hazards, risks and consequences of disasters linked to the changing climate; the well-being and livelihoods of people living in Canada are better protected; and overall disaster risks have been reduced, particularly for vulnerable sectors, regions, and populations at greater risk.

Proposed 2030 objectives

Objective 1

Disaster risk management and planning by public and private sector organizations is based on a shared understanding of disaster and climate change risks in all its dimensions of vulnerability, capacity, exposure of persons and assets, hazard characteristics, the environment, and other inadvertent impacts to better prepare for disaster risk response in the future. For example, this could include identifying the top risks, such as flooding, wildfire and heat events, along with concrete actions that could be undertaken by whole-of society partners.

Objective 2

All people living in Canada are able to access information on the climate risks they face in their communities and what actions they can take to prepare for, reduce, and respond to them. For example, this could include strengthening public awareness campaigns on emergency preparedness and disaster risk reduction.

Objective 3

An increased, prioritized and sustained investment in Emergency Management (EM) and disaster risk reduction capabilities, and capacity building, across jurisdictions and amongst partners, with a view to leverage this expertise and increase coordination. For example, this could include developing a civilian response capacity with the participation of various orders of government and whole-of-society partners.

Objective 4

People living in Canada have the tools and capacity needed to remain and/or become financially secure and responsive to the threats and impacts of climate-related hazards. For example, this could include developing a Flood Risk Portal where the public could access information on how to better protect themselves and their households from flood risks.

Objective 5

National and regional readiness, mitigation, and recovery plans and policies allow people living in Canada of all socio-economic backgrounds to overcome challenges. For example, this could include incorporating traditional Indigenous knowledge into emergency management plans.

Objective 6

All orders of government have built, and are leveraging, interoperable mitigation/prevention programming across the Emergency Management system. For example, this could include developing standardized tools as well as enhancing public alerting and emergency communications capabilities.

Objective 7

There is a measurable reduction of people in Canada impacted by climate-related hazards. For example, this could include investing in managed retreats and strategic relocations for high flood risk areas and better planning and prevention for urban wildfire interface areas.

Objective 8

Every person living in Canada who was victim of a climate disaster is no longer displaced and their livelihood is restored within one year of onset as a result of relocation, and/or community investments in disaster mitigation. For example, this could include developing new disaster recovery mechanisms and appropriate disaster financial assistance supports.

- What are the most urgent priorities in your community for disaster resiliency?

- How can we improve recovery efforts to help Canadians that experience a climate disaster?

- What are examples of key capacities in your community that are currently helping or would help with preparedness?

Health and well-being

The challenge

Climate change is having a serious impact on the health and well-being of people living in Canada, and placing additional stress and increasing costs on the health system. Climate change increases the frequency and severity of existing health risks (e.g., extreme heat, wildfires, floods, air pollution, water quality, Lyme disease, chronic diseases, etc.) and is driving the emergence of new risks (e.g., mental health impacts associated with climate change, emerging infectious diseases, food safety). The 2010 and the 2018 extreme heat events in Quebec led to 291 and 86 deaths respectively. The 2021 heat wave in British Columbia was associated with 740 deaths. Climate impacts on food and water security can also exacerbate health-related issues.

Certain priority populations are disproportionately impacted by health inequities that can be exacerbated by climate change impacts. These groups include infants and children, seniors, people with underlying health conditions, northern communities, First Nations, Inuit and Métis, and those of lower socio-economic status, requiring an equitable approach and responses.

Climate change affects mental health, leading to increased anxiety, depression, Post Traumatic Stress Disorder and/or ecological grief. It also affects cultural identities through loss of access or connection to places, practices and traditions. The mental health impacts of lost access to land, sites, practices or traditional food sources can be significant. Culture can also be a powerful tool for adaptation, and artists can inspire creative action.

Indigenous peoples are among the first to face the direct consequences of climate change, due to their close relationships to land, waters, animals, plants, and natural resources. The existing burden of health inequities and related determinants of health put them at greater risk. An equitable approach and response means improving social determinants of health including income and employment, housing, and education. We must urgently accelerate health adaptation, including research to help prevent negative health impacts, and health promotion and response efforts, across all parts of Canada in order to save lives and reduce pressures on the health system.

Proposed 2050 goal: The health of all people in Canada is supported by a climate-resilient and adaptive health sector that has robust and agile systems and services that account for and support the diverse components of well-being.

Proposed 2030 objectives

Objective 1

Healthcare and public health systems in Canada have the resources, capacity, tools, and competencies needed to continually assess, understand, and reduce priority climate-related health risks.

Objective 2

People living in Canada have equitable access to climate change and health adaptation measures, where they understand their climate change health risks and are knowledgeable in ways to take action.

Objective 3

Climate change and health adaptation decision-making in Canada is underpinned by robust health, socio-economic, and environmental evidence, as well as Indigenous and other knowledge systems, to address climate-related health impacts.

Objective 4

The health sector as well as other health supporting systems are integrating health and climate change considerations into all decision-making processes.

- Has your health been impacted by climate related events? In what way?

- What are the top climate related health impacts (e.g. heath-stroke, mental well-being) that should be prioritized for action? Why?

Infrastructure

The challenge

Climate impacts have clear implications for Canada's infrastructure services and systems, as evidenced by extreme weather events across Canada throughout 2021. The historic extreme events in British Columbia throughout 2021 compounded and exacerbated one another. The atmospheric river events that caused unprecedented flooding and landslides were worsened by, and exacerbated impacts of, the heat dome and devastating forest fires in the summer. These events, and the climate-driven weather events in Atlantic Canada, continue to disrupt and affect communities, key sectors, services, and infrastructure. All aspects of the built environment in Canada, including grey, hybrid, and natural infrastructure, are impacted by climate change, including: roads, bridges, dams, highways and railways, buildings, housing, health care infrastructure, water supply infrastructure, wastewater and storm water infrastructure, ports, harbours, and waterways, energy infrastructure, and information / telecommunication technologies.

What is the difference between built and natural infrastructure?

Built and natural infrastructure include both new and existing assets and include the services and provisions that infrastructure provides and the systems in which they function. A systems-based approach helps frame adaptation solutions to account for the interdependencies and cascading impacts across a variety of infrastructure responses that involve a combination of technical, financial, policy, legal, and socio-economic aspects. Infrastructure systems also cut across multiple scales, from jurisdictions to ecosystems and watersheds, to provide community benefits, health care, utilities, water and wastewater, telecommunications, emergency services, trade, transportation, and power, amongst others.

Climate change risks to infrastructure can:

- Endanger people's health and safety and increase the incidence of death, injury or disease

- Disrupt businesses, market and food access, supply chains, services, and everyday community activities

- Incur major repair costs for buildings and infrastructure

- Increase hazard exposure and investment uncertainty, affecting the vitality and growth of our cities, towns, suburbs and regional areas

Accelerating progress towards climate-resilient infrastructure requires a whole-of-society effort, including all orders of government, especially as provincial, territorial, Indigenous and local governments own and operate about 97 percent of publicly owned infrastructure in the country.

Importantly, in building climate-resilient infrastructure systems, decisions may need to explicitly consider reducing or discontinuing investment in order to achieve resilience outcomes. We will need to consider the balance between investing in high-risk areas and no longer investing in infrastructure where resiliency is not achievable. Examples include building in high-risk floodplains or investing in port facilities where roads are at high-risk of extreme events.

Proposed 2050 goal: All infrastructure systems in Canada are climate-resilient and undergo continuous adaptation to adjust for future impacts, to deliver reliable, equitable, and sustainable services to all of society.

Proposed 2030 objectives

Objective 1

Technical standards have been updated or developed to skillfully embed climate change in all decisions to locate, plan, design, manage, adapt, operate, and maintain infrastructure systems across their lifecycle.

Objective 2

A robust investment framework is in place to guide the allocation of sufficient public and private funds towards low-carbon and climate resilient infrastructure, maximizing the long-term benefits of infrastructure investments.

Objective 3

All orders of government utilize a coherent and integrated, community-informed policy and regulatory framework to drive resilience in public and private infrastructure decision-making.

Objective 4

Our increasingly climate-resilient infrastructure systems support the health and well-being in communities and secure economies, with a particular emphasis on prioritizing benefits and eliminating funding gaps for marginalized populations and those in high-risk areas.

- How has climate change affected the infrastructure services in your community? How long was your access to these services interrupted?

- Which parts of the built environment (e.g., homes and buildings, bridges, wastewater infrastructure) in your community are the most exposed to the risks of climate change? Which parts should be prioritized for action?

Natural environment

Nature-based solutions in focus

Nature-based solutions on working landscapes represent a win-win solution for adaptation, mitigation, and other environmental priorities (i.e., soil health, biodiversity, and water conservation), including within the agriculture and agri-food sector. For example, this includes but is not limited to maintaining and restoring grasslands, wetlands, piloting innovative regenerative agriculture practices, and enhancing riparian areas and on-farm wildlife areas (e.g., establishing pollinator strips).

The challenge

Climate change is affecting the resilience of Canada's ecosystems and causing impacts to the biodiversity they support and the services they provide. Canada's natural environment includes land-based ecosystems such as grasslands and forests, freshwater ecosystems such as rivers and wetlands, as well as coastal and marine ecosystems. Ecosystems support life and provide some of our most basic needs, like food, clean water, productive soil, natural pest control, pollination, flood and erosion mitigation, and carbon sequestration. These ecosystems also have immeasurable intrinsic value, and our cultural identities are closely tied to our connection to land, water, and air. Replacing the services that ecosystems provide would be extremely challenging and costly, if possible at all. The ecological integrity of our natural environment, including genetic diversity, is vital to adapt to ongoing changes in our climate.

In the context of advancing a thriving natural environment through the Strategy, outcomes will require us to shift away from a development lens and towards a stewardship lens. This stewardship lens positions people as part of, and active participants in, ecosystems, including their protection and recovery. It recognizes that when the environment thrives, people thrive.

Proposed 2050 goal: Biodiversity loss has been halted and reversed and nature has fully recovered allowing for natural and human adaptation, where ecosystems and communities are thriving together in a changing climate, with human systems existing in close connection with natural systems.

Proposed 2030 objectives

Objective 1

Human activities are transformed to halt and reverse biodiversity loss, while respecting Indigenous rights and titles.

Objective 2

Inclusive adaptation governance systems are in place that involve communities in the co-development and implementation of actions that support a thriving natural environment.

Objective 3

Indigenous peoples, organizations, and communities exercise self-determination on their lands and territories for ecosystem stewardship initiatives to adapt to climate change.

Objective 4

The power of nature is leveraged, and resilience is enhanced through nature-based solutions that are mainstreamed, underpinned by decision-making frameworks that take into account both the economic and non-economic values of ecosystem services and avoid unintended negative impacts on ecosystems.

Objective 5

Conservation and restoration practices and plans, monitoring programs, and management practices are in place for the ecosystem services most affected by climate change to ensure their continued viability and adaptive capacity.

Objective 6

Decisions on adaptation actions are informed by comprehensive and accessible information on the state of ecosystems and their abilities to adapt and their overall resilience.

- How has climate change affected your access to nature? How has this impacted your mental well-being and sense of self?

- What information or tools would help your community or sector adopt nature-based solutions or leverage the power of nature?

- Can you share examples of expansive and inclusive decision-making?

Economy

The challenge

In the context of the Strategy, a 'Strong and Resilient Economy' refers to strengthening the resilience and reducing the vulnerability to impacts of climate change on people living in Canada, and on Canada's individual economic and financial sectors. Seven key sectors identified inCanada's National Issues Report are particularly at greater risk of the impacts of climate change: forestry, fisheries, agriculture, mining, energy, transportation, and tourism. While these sectors are accustomed to dealing with historic climate variability, the pace of climate change is forcing them to adapt to new, more frequent, and more extreme weather events and climate extremes, and to anticipate projected risks. Adaptation is also needed in areas such as labour, trade, and supply chains, finance, investment, and insurance underwriting to support behaviours and products that enhance resilience. Climate change-related risks that pose the significant threat of disruptions to the operations of Canada's individual economic sectors and reliant communities are often crosscutting in nature – for example, disruptions in the agriculture sector can have major impacts for food production and food security. The adaptation of Canada's individual economic sectors to the impacts of climate change will require collaborative efforts to address both crosscutting and unique challenges faced by each of the sectors. Proactive climate change decision-making and adaptation actions must support a resilient economy, Indigenous rights, and equitable opportunities.

Proposed 2050 goal: Canada's economy is structured to anticipate, manage, and respond to climate change impacts; and to advance actively new and inclusive opportunities within a changing climate, particularly for communities at greater risk, Indigenous peoples, and vulnerable economic sectors.

Proposed 2030 objectives

Objective 1

The business case for adaptation is developed through research and knowledge is disseminated to the appropriate users.

Objective 2

The right incentives are in place and disincentives are removed for proactive adaptation.

Objective 3

Canada has a skilled, diverse, and adaptable workforce that is supported by education, training, and knowledge and skills development as the country adapts to climate change.

Objective 4

Investment in adaptation actions and activities is attracted through leadership and collaboration of all jurisdictions, both public and private sectors.

- How do you expect climate change to impact your economic future (e.g., job stability, earning potential, etc.)?

- Does your community or sector have access to financial resources to adapt to and prepare for a changing climate?

Our priority short-term actions

In order to reach our ambitious goals, we need to take action now. The National Adaptation Strategy will outline priority actions to meet Canada's objectives and address challenges across systems. Accompanying action plans will outline responsibilities, resources, and targets for the first five years.

We are seeking your input and ideas to develop a strong set of priority actions in the next 3-5 years to support implementation of the Strategy.

Some illustrative priority actions

- Enhance food security by assessing Canada's food system and identifying enabling conditions for supply-side (e.g., efficient production and distribution, reduced exposure to import risks) and demand-side (e.g., reduction in food loss and waste) actions – prioritizing impacts on populations that face greater risks

- Continue to develop and share information to protect communities from climate-related disasters (e.g., identify and share information on high risk flood zones including flood mapping; develop tools and training to protect communities from wildfire risks)

- Implement regulatory and policy measures in both public and private sectors to encourage the assessment and disclosure of the physical risks posed by climate change to inform planning and financial decision-making by individuals, communities, organizations and all orders of government

- Update codes and standards (e.g., building codes, infrastructure standards, professional certifications) to fully reflect low-carbon climate resilience considerations and promote their uptake and adoption across jurisdictions to support resilient communities across the country

- Expand the network of trained responders and equipment strategically located across the country to respond to emergency situations, including climate events

- Integrate and prioritize nature-based solutions in public spending on climate adaptation

- Professional associations and organizations in Canada integrate comprehensive considerations of climate change, ecosystem stewardship, nature-based solutions, Indigenous laws, rights and title, and values of environmental and intergenerational justice in ethics, standards, regulations, and operations

- Put in place effective decision-making mechanisms to incorporate climate adaptation considerations within and between different orders of government, in order to scale up efforts and avoid piecemeal approaches to building climate resilience

- How is climate change currently impacting your sector?

- What actions do we need to take in the next five years?

- What are your priorities for action?

Our foundations for an effective strategy

The foundations for an effective strategy are: governance; scientific knowledge and diverse ways of knowing; sustained funding for capacity building and long-term action; and awareness and commitment of indidivuals to act.

Governance

Strong leadership, clear responsibilities and accountability are needed to effectively adapt to climate change over long periods of time. We need robust ways to work together to coordinate among government jurisdictions, Indigenous peoples as rights holders, and to hear from many different voices to identify shared priorities, scale up solutions, and make progress.

The Strategy will develop a governance structure that will increase attention on the need for climate change adaptation and preparedness, mobilise and coordinate actions, and track actions and initiatives. Details on governance will evolve as the Strategy is developed; however, it will consider all orders of government, Indigenous Knowledge Systems and governance structures within Indigenous Nations, private companies, academia, civil society, youth, women, non-governmental organizations, and the public.

Governance for climate change adaptation will be:

- Effective, efficient, and coordinated with clear responsibilities and accountabilities within and between jurisdictions, including with Indigenous peoples. This will allow for effective and cooperative action on best practices and solutions that account for unique needs and context across the country.

- Aligned with formal mechanisms being established to achieve stronger coordination and strategic partnership for disaster risk reduction and emergency management and implementation of adaptation actions.

Scientific knowledge and diverse ways of knowing

Building scientific knowledge, reflecting diverse ways of knowing, and ethically valuing Indigenous knowledge are essential to inform ambitious action and measure progress. Our systems are changing rapidly in response to climate change; the effectiveness of solutions will depend on the ability to look ahead to understand how the climate will continue to change.

Measuring progress towards our goals will require investment in monitoring and analysis to ensure our efforts support equitable outcomes and do not have unintended negative impacts. New knowledge will also help build the business case for investment in adaptation and support innovation to create more effective options and give decision-makers a greater range of choices. Research and study in the social sciences will help us recognize how different people and groups are at greater risk of climate change impacts and help reduce inequity.

Environment and Climate Change Canada is leading the development of Canada's first National Climate Change Science Plan, which will be released in Fall 2022. The Science Plan will identify priority scientific research and related activities that can deliver results over the next five to seven years. These will also support progress on longer-term science challenges such as understanding future climate warming, assessing risk and designing solutions. The scope that will include natural, social, economic, behavioural and health sciences will help inform the transformational changes needed to reach the National Adaptation Strategy's 2050 goals and medium-term objectives. The Science Plan will enable Canada, like other countries, to align its science efforts with its goals and actions to prepare for and adapt to climate impacts.

Sustained funding for capacity building, long-term planning and action

Taking action to prepare for climate change impacts will require investments; but the cost of delaying or not taking action is much greater. Long-term planning and action will require a strong commitment to act, and to continue these efforts over time. Our investments must reflect the importance of the challenge.

The current approach—too often fragmented, short-term, and project-based—is insufficient to address the climate change challenges Canada is facing. There is a need to shift the predominant investment patterns by the public and private sector to support up-front measures that would help communities avoid or reduce potential climate related damages. Sustained funding and policies can allow governments to be able to identify and act on their own adaptation priorities, with specific support for the most at risk communities and regions, including Indigenous peoples.

The impacts of climate change affect all aspects of society, and the costs of adapting cannot be borne by governments alone; the private sector and civil society must also make important contributions, including through innovative partnerships, training, and skills development.

Awareness and commitment of individuals to act

While some adaptation measures can be implemented through policy processes (e.g., codes, standards, by-laws), some will require individual action and broader support (e.g., re-zoning flood plains, wildfire-smart homes and communities, and household measures to reduce the effects of storms and flooding). Individuals can also play an important role in showcasing measures which can lead to greater uptake in their communities and neighbourhoods.

- What do you think about these foundations for action?

- What foundational actions are missing?

Next steps

The Government of Canada will work with partners (provincial, territorial and municipal governments and Indigenous peoples) to develop Canada's first National Adaptation Strategy for release in fall 2022. Accompanying action plans will outline responsibilities, resources, and targets to implement the Strategy in the first five years.

Experts, key stakeholders, and public engagement will help shape the Strategy and the actions that will be taken. The public engagement period for the Strategy will be open for spring and summer 2022.

Share your views

- Share your ideas and expertise at the May 16 National Adaptation Strategy Symposium and in upcoming workshops

- Provide feedback and answer questions on the Let's talk adaptation website

- Share your adaptation stories on the Let's talk adaptation website by submitting photos or videos of how you and your community are preparing for climate change impacts (e.g., installing community gardens, protecting or restoring a wetland, planting trees to prevent erosion, creating gathering areas for emergencies, etc.).

- Send your written comments by email to adaptation@ec.gc.ca

Annex A: Current adaptation action

Canada's Map of Adaptation actions

The National Adaptation Strategy is building on Canada's efforts to date, to scale-up actions across regions and sectors. Check out the Map of Adaptation Actions to see what others have done in Canada to prepare and adapt to climate change. Have questions about the Map? Get in touch with the project team: carteadapt-mapadapt@ec.gc.ca.

Many strategies and initiatives across the country are helping to build climate resilience and reducing greenhouse gas emissions in Canada. Ongoing initiatives are also focused on decarbonisation, decolonization, and addressing systemic inequalities.

The National Adaptation Strategy will build on existing work and forge linkages with strategies and initiatives, including:

- 2030 Emissions Reductions Plan

- Arctic and Northern Policy Framework

- Blue Economy Strategy

- Canada Water Agency

- Canada's 2030 Agenda National Strategy: Moving Forward Together

- Canada's Buildings Strategy

- Canada's First National Housing Strategy

- Canada's First Poverty Reduction Strategy

- Canada's Youth Policy

- Canadian Agricultural Partnership and the Next Agricultural Policy Framework (including The Guelph Vision Statement)

- The Canadian Wildland Fire Strategy

- Emergency Management Strategy for Canada

- Food Policy for Canada

- The National Infrastructure Assessment

Provincial and territorial governments' climate change and emergency management plans include strong adaptation components; many have developed stand-alone climate change adaptation plans or strategies, and have made investments to support adaptation decision-making.

Cities and communities are actively planning for climate change risks by developing adaptation strategies that inform city planning and infrastructure investment decisions, encouraging action by homeowners and businesses, and putting in place measures to advance local action (e.g., land-use by-laws, policies and zoning regulations, public health measures).

For many generations, Indigenous peoples have been the carers of the environment and continue to demonstrate strong climate change adaptation leadership. For example, Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami developed the National Inuit Climate Change Strategy; the Assembly of First Nations' (AFN) National Climate Change Strategy is under development; and the Métis National Council is building capacity to address the increasing impacts of climate change on the health and well-being of their citizens and communities. Regional-level initiatives and strategies are also being advanced and many Indigenous communities are implementing community-based adaptation initiatives.

Federal initiatives to date

The following provides high-level information on initiatives that support climate change adaptation being led by key federal departments that are partnering with ECCC on the National Adaptation Strategy: Health Canada (HC), Infrastructure Canada (INFC), Natural Resources Canada (NRCan), and Public Safety Canada (PS). Adaptation-related roles, responsibilities and mandate commitments of the key departments are also outlined.

Health Canada

HC supports the health sector through research, information, and services to better understand and prepare for the health risks of climate change.

Key initiatives:

- Climate Change and Health Adaptation: Heat and Health Risk Assessment Program. Budget 2016 provided $8.5M over 5 years, with $1.6M ongoing, to better respond to heat-health risks through planning, training, engagement, and research.

- Climate Change and Health Adaptation: Information and Action for Resilience [sunset in March 2022]. Budget 2017 provided $17.2M over 5 years to better understand and track the current and potential future health impacts of climate change; ensure that health system actors are supported in efforts to prevent, promote and respond appropriately.

- Health of Canadians in a Changing Climate: Advancing our Knowledge for Action report, under the Canada in a Changing Climate national assessment process. This report offers an assessment of these risks and will support healthcare decision-makers in taking action at a local, provincial/territorial and national levels. It is also relevant to those who work in public health, health care, emergency management, research and community organizations (release date: February 9, 2022).

Infrastructure Canada

INFC leads the delivery of long-term funding to enable investments in resilient infrastructure. INFC also builds partnerships, develops policies, and fosters knowledge about public infrastructure in Canada.

Key initiatives:

- Disaster Mitigation and Adaptation Fund (DMAF). Budget 2017 provided an initial $2B over 10 years to support built and natural infrastructure projects. This funding helps communities remain resilient in the face of natural disasters triggered by climate change. Budget 2021 recapitalized DMAF with an additional $1.375B over 12 years, introducing a new small-scale projects stream and allocating a minimum of 10% of funding to Indigenous recipients. As of May 2022, DMAF has invested $2.1B to date for 70 infrastructure projects to mitigate threats of natural disasters such as floods, wildfires and drought. Additional funding announcements will occur throughout 2022.

- Investing in Canada Infrastructure Program – Green Infrastructure Stream. Budget 2017 provided $9.2B over 10 years to support green infrastructure projects that advance outcomes related to climate change mitigation; adaptation, resilience and disaster mitigation; and environmental quality. Projects are advanced through Integrated Bilateral Agreements with the provinces and territories.

- Natural Infrastructure Fund (NIF). Budget 2021 provided $200M over 3 years to support projects that use natural or hybrid approaches to protect the natural environment, improve access to nature for Canadians, and support healthy and climate resilient communities. The NIF is investing up to $120M in large-scale projects. Select major cities with innovative natural infrastructure strategies have been invited to apply for up to $20M in funding. A small project stream will be launched to support smaller natural infrastructure projects. A minimum of 10% of the overall program envelope will be allocated to Indigenous recipients.

- National Infrastructure Assessment. Budget 2021 provided $22.6M over 4 years to INFC to conduct Canada's first National Infrastructure Assessment. The assessment once in place, will help identify Canada's evolving needs and priorities in the built environment and undertake evidence-based long-term planning toward a resilient and net-zero emissions future.

Natural Resources Canada

NRCan supports climate change adaptation in four key areas: foundational knowledge and capacity building, wildfire resilience in the forestry sector, resilient housing, and geoscience/flood mapping.

Key initiatives:

- Adapting to a Changing Climate program. Budget 2016 provided $35M (sunset in 2021) and $3.5M in ongoing funding to support the delivery of Canada's Adaptation Platform, as well as projects to fill knowledge gaps, share information, and build capacity to adapt with a particular focus on communities and the natural resource sectors. This includes the National Assessment process, Canada in a Changing Climate: Advancing our Knowledge for Action, which is producing a series of reports on how the climate is changing, the impacts of these changes, and how Canada is adapting.

- Building Regional Adaptation Capacity and Expertise [sunset in March 2022]. Budget 2017 provided $18M over 5 years to Natural Resources Canada to build expertise and capacity to take action, including by supporting training, and capacity-building through workshops, online training modules, professional training; and establishing communities of practice.

- Wildfire Mapping. Budget 2021 provided $28.7M over 5 years to support increased mapping of areas in Northern Canada at risk of wildfires. This funding would also enhance the capacity of the Canadian Interagency Forest Fire Centre, which is jointly funded in partnership with provinces and territories.

- Flood Hazard Identification & Mapping Program. Budget 2021 provided $63.8M over 3 years to NRCan, ECCC and PS to help Canadians better plan and prepare for future floods. In partnership with provincial and territorial governments, the FHIMP aims to complete flood hazard maps of higher risk areas in Canada and make this flood hazard information accessible.

- Canada Greener Homes Grants. Launched in 2021, the $2.6B, 7-year program is helping Canadians make energy-efficient upgrades to their homes, as well as targeted resilience upgrades. The 2021 Ministerial Mandate Letters committed to expanding the program to include more resilience measures and creating a Climate Adaptation Home Rating Program as a companion to the EnerGuide home energy audits.

Public Safety Canada

PS leads federal emergency management initiatives and ensures coordination across all federal departments and agencies responsible for national security and the safety of Canadians. This includes working to keep Canadians safe from a range of risks such as natural disasters and human-induced disasters (e.g. crime and terrorism).

Key initiatives:

- Leads work with provinces and territories to implement the Emergency Management (EM) Strategy for Canada, which establishes FPT priority actions to strengthen Canada's ability to assess disaster risks and to prevent/mitigate, prepare for, respond to, and recover from disasters.

- Manages the Disaster Financial Assistance Arrangements (DFAA), which is the mechanism through which the federal government provides financial assistance to PT governments in the event of a large-scale natural disaster where response and recovery costs exceed what individual PTs could reasonably be expected to bear on their own.

- An independent Expert Panel focused on DFAA review has been stood up. Recommendations and options to amend the terms and conditions of the DFAA are expected in Spring 2022.

- PS was allocated $6.3M over 2 years, starting in 2020-21, to undertake work on flood insurance and relocation, including to stand up the Task Force on Flood Insurance and Strategic Relocation. Policy objectives have been developed and options are currently being researched for a national insurance and flood relocation action plan. The Task Force will report on its findings by Spring 2022.

- The National Risk Profile is a strategic national disaster risk and capability assessment to create a forward-looking picture of Canada's disaster risks and capabilities in order to strengthen Canadian communities' resilience to disasters, such as floods, wildfires and earthquakes. The National Risk Profile will help to improve Canadians' awareness and understanding of disaster risks through biennial public reporting.

- National Disaster Mitigation Program [sunset in March 2022]. Budget 2014 earmarked $200 million over five years, to establish the National Disaster Mitigation Program (NDMP). The Economic and Fiscal Snapshot 2020 provided an additional $25M over 2 years to support provinces and territories to address flood risks through risk assessments, flood mapping, flood mitigation planning, and investments in non-structural flood mitigation projects.

Annex B: Climate change risk and knowledge assessments and supporting services

Knowledge and risk assessments

National climate change assessment processes include, but are not limited to:

- A series of national assessments reports coordinated by Natural Resources Canada, which provide the most up-to-date syntheses of knowledge on climate change, impacts and how Canada is adapting, and the foundation to inform decision-making on climate change adaptation in Canada. The assessments are developed through a rigorous, open process that ensures relevancy and credibility, and engage a broad partnership of subject-matter experts and assessment users from all orders of government, Indigenous organisations, universities, professional and non-governmental groups and the private sector.

- The most recent report (2022) in the series, The Health of Canadians in a Changing Climate: Advancing our Knowledge for Action report, led by Health Canada, provides an evidence base for the health portion of the Strategy. This report provides an assessment of the risks of climate change to the health of Canadians and to the health care system; and helps to support actions by health decision makers at local, provincial/territorial and national levels, as well as those who work in public health, health care, emergency management, research, and community organizations.

- Public Safety Canada is currently leading the development of a National Risk Profile to support a greater understanding of disaster risk, as per one of the key priorities under the Emergency Management Strategy for Canada: Toward a Resilient 2030. This initiative will bring Canada in-line with other countries. The National Risk Profile is a strategic national disaster risk and capability assessment that uses scientific evidence and stakeholder input to strengthen Canadian communities' resilience to the most costly natural hazards, including earthquakes, and climate-related hazards, such as floods and wildfires.

- Infrastructure Canada is currently leading a National Infrastructure Assessment to assess Canada's long-term infrastructure needs, improve coordination amongst infrastructure owners and funders, and determine the best ways to fund and finance infrastructure.

A wide range of climate change risk and vulnerability assessments have been completed or are being completed by provincial, territorial, and Indigenous governments, Indigenous communities, urban and rural municipalities, sectors, and businesses.

Climate services

Climate service organizations play a critical role in the provision of data, information, training and tools that decision makers need to better understand the changing climate. Recognizing the need to improve access to climate data as well as training and support to use this information, the Canadian Centre for Climate Services (CCCS) was established in 2018, as part of the Pan-Canadian Framework on Clean Growth and Climate Change to improve access to authoritative, foundational climate science and information. The CCCS supports a suite of user-friendly online climate portals, making relevant, timely and user-oriented climate information easily accessible and understandable for Canadians to consider historical trends and projected future climate conditions in their decisions. This includes information on ClimateData.ca, the CCCS Website and ClimateAtlas.ca. The CCCS also operates a Support Desk to answer user questions, and conducts outreach and training activities to improve skills regarding how to access and use climate data, information, and tools.

Through a partnership-based approach working with provinces, territories, climate services experts and regional climate service organizations such as PCIC, ClimateWest, Ouranos and CLIMAtlantic, the CCCS aims to provide Canadians with the information and support they need to consider climate change in their decisions, reduce vulnerability and increase resilience to climate change impacts.

Training and skills

Although having access to these climate change assessment activities and to the science, data, and knowledge behind them is useful and important for understanding climate change risks, training, education, and capacity building are essential to further enhancing this understanding. Despite current government investments in expanding professional capacity for adaptation, there remain substantive gaps in training and skills with respect to using climate projections to inform the choice of action (e.g., including the skills needed to understand data availability and gaps, incorporate climate projections, and interpret and use regional climate data, and assess impacts, risks, and vulnerabilities). Training and capacity building is also needed to help with the application of climate information into assessments, planning and decision making for various sectors, such as infrastructure development, land-use planning, public health, emergency preparedness, agriculture, mining and tourism.

Annex C: Key terms and concepts

- Adaptation

- In human systems, the process of adjustment to actual or expected climate and its effects, in order to moderate harm or exploit beneficial opportunities. In natural systems, the process of adjustment to actual climate and its effects; human intervention may facilitate adjustment to expected climate and its effects.Footnote 2

- Adaptation Pathways

- A series of adaptation choices involving trade-offs between short-term and long-term goals and values. These are processes of deliberation to identify solutions that are meaningful to people in the context of their daily lives and to avoid potential maladaptation.Footnote 3

- Adaptive Capacity

- The ability of systems, institutions, humans and other organisms to adjust to potential damage, to take advantage of opportunities, or to respond to consequences.Footnote 4

- Adaptive Management

- Adaptive Management is a process where decision makers take action in the face of uncertainty. Adaptive management seeks to improve scientific knowledge, and to develop management regimes that consider a range of possible futures outcomes and even take advantage of unanticipated events.Footnote 5

- Co-benefits