Five Steps to Safe Shipment – Canadian Conservation Institute (CCI) Notes 20/3

Disclaimer

The information in this document is based on the current understanding of the issues presented. It does not necessarily apply in all situations, nor do any represented activities ensure complete protection as described. Although reasonable efforts have been made to ensure that the information is accurate and up to date, the publisher, the Canadian Conservation Institute (CCI), does not provide any guarantee with respect to this information, nor does it assume any liability for any loss, claim or demand arising directly or indirectly from any use of or reliance upon the information. CCI does not endorse or make any representations about any products, services or materials detailed in this document or on external websites referenced in this document; these products, services or materials are, therefore, used at your own risk.

List of abbreviations

- A

- area

- h

- height

- LDPE

- low-density polyethylene

- RH

- relative humidity

- t

- thickness

- W

- weight

Introduction

This Note outlines a five-step approach to packing fragile objects for shipment. The steps describe some of the key actions to take to help ensure that objects arrive at their destinations safely.

When shipping a fragile object, the main concerns will be

- shock and vibration;

- punctures, dents and abrasion, impact and distortion;

- strain and compressive forces acting on packages during handling, storage and transport; and

- environmental hazards such as incorrect temperature and humidity, water, pollutants and pests.

Step 1: begin with object features and shipping details

It helps to start the packing project by asking questions such as the following:

- What makes this object special or a cause for concern (perhaps its importance, value, unique features, unusual fragility or handling challenges)?

- What are the object’s dimensions and weight?

- What information is available about the object’s structure, materials and condition?

- Is there someone who has first-hand knowledge of the object and its history?

- When will it travel?

- Is it a one-way shipment, a return shipment or a travelling exhibit?

- If it is a one-way shipment, is it a door-to-door scenario with oversight by a single carrier?

- Where is it going?

- Why is it being shipped?

- What type of carrier will be used?

- What do you know about the carrier’s vehicles and the distribution network?

The answers to these questions will help you plan your shipment and establish appropriate packaging requirements.

Advise your carrier if there is anything unusual about the object being shipped or the shipping specifications. Basic package design information, such as object size and weight, helps in selecting the right vehicle; it also makes it easier to estimate the package size to ensure that it can move easily through shipping and receiving sites. Information on the object and its materials will help to prioritize hazards and necessary control measures.

Insights gained from people familiar with the object can help to specify handling methods and the design of suitable packaging, especially where handling forces or package features come in contact with the object. This dialogue may also aid in the discovery of unusual or hidden object susceptibility. If objects are shipped for treatment, they may require protective measures (such as consolidating loose paint). In this case, seek conservation advice in advance.

The time of year and the amount of time in transit will indicate whether or not temperature-controlled transport is needed. Typical packaging provides anywhere from 30 minutes to several hours of protection against sudden temperature changes. When temperature-controlled transport is required, the standard specification is reliable control in the range of 15°C to 25°C (59°F to 77°F).

The type of shipment will help inform a package concept. A one-way source-to-destination shipment can be packed simply (for example, basic screw closures for shipping crates). If packing for multiple venues, you can include features that simplify repeated crating and uncrating cycles.

To ensure safe shipment, anticipate the hazards on the toughest leg of the journey and pack accordingly. Table 1 summarizes several shipping network scenarios and compares their hazard profiles. Some packaging comments are offered for basic guidance. Because object susceptibility and museum package performance are often unknown, consider additional actions you can take to ensure safe shipment. They include good planning and oversight, ensuring that cargo is well secured in the transport vehicle and using good carriers and well-maintained transport vehicles.

| Scenario | Relative hazard intensity | Packaging comments |

|---|---|---|

| Art handler door-to-door shipment without cargo transfers (controlled network) | Low |

|

| Art handler shipment and supervised air cargo | Low to moderate |

|

| Art handler shipment, air cargo and trusted commercial carriers | Moderate |

|

| Commercial carriers | Moderate to high |

|

| Parcel post courier shipments | High to very high |

|

| Factor | How it causes damage | Remedies |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental problems |

|

|

| Excessive force |

|

|

| Lack of restraint in transit |

|

|

| Environmental hazards |

|

|

| Extreme hazards |

|

|

Step 2: reduce object susceptibility, if possible

The susceptibility of an object or its parts to damage by shock or vibration increases with the degree of flexibility and looseness, the presence of structural or material weaknesses and any pre-existing damage. In some cases, it may be possible to reduce susceptibility by controlling these factors. Table 3 lists several examples and suggested remedial measures.

| Example | Remedies |

|---|---|

| Out-of-plane displacement (bowing out of the canvas perpendicular to its plane) of small to medium-sized canvas paintings |

|

| Out-of-plane displacement of a large canvas |

|

| Forces causing weak painting frames or stretcher boards to scissor (deform) and increase strain levels in a stretched canvas |

|

| Fragile paint layers in a painting being shipped for treatment |

|

| Minimize factors that increase force susceptibility in large items, such as furniture and machinery |

|

| Pre-existing damage |

|

| Complex assembly (such as a dinosaur skeleton or a contemporary art item) |

|

Step 3: achieve important benefits with primary packaging

Primary packaging is basic protection that is applied close to or in contact with the object. This may include wrapping, protective interleaves between objects, and transit mounts that firmly restrain an object in all directions. Primary packaging can make objects easier to handle and pack, and it may provide adequate protection on its own in some cases. It can also be used to control environmental hazards for susceptible items. Table 4 provides examples of primary packaging treatments and their benefits.

| Primary packaging treatment | Benefits |

|---|---|

| Basic wrapping with an interleaf material followed by polyethylene (wrapping paintings, as outlined in CCI Note 10/16 Wrapping a Painting) |

|

| Armatures or other provisions to support a fragile object or one with fragile surfaces at non-critical areas |

|

| Careful, repetitive wrapping of an object with a fragile surface with narrow strips of unbuffered tissue paper made of abaca fibres, also known as a “mummy wrap” |

|

Negative mount (a form-fitting cut-out in a firm foam material such as polyethylene foam) or a padded wooden armature (An interleave material may be used between the object and the mount to improve the fit of the mount or to further protect fragile surfaces at support locations.) |

|

| Hard objects such as bottles or dishes packed together in a box and separated from each other and the inner box surfaces with an interleave material such as cardboard, foam, tissue, cellulose wadding or paper |

|

| Measures to ensure that the items do not move or collide with each other, such as several items firmly packed and separated with suitable interleaves or durable partitions for heavy items |

|

| Filling internal voids of thin-walled items such as hats or boxes |

|

| Material | Description | Applications |

|---|---|---|

| High-density polyethylene sheet (HDPE) |

|

|

| Low-density polyethylene sheet (LDPE) |

|

|

| Thread seal tape made of poly(tetrafluoroethylene) (Teflon) |

|

|

| Aluminum-coated polyethylene (such as Marvelseal 360) |

|

|

| Unbuffered tissue paper |

|

|

| Non-woven polyethylene sheets (such as Tyvek) |

|

|

| Cross-linked polyethylene sheet (such as Volara) |

|

|

| Stretch wrap |

|

|

| Polyethylene foam sheet (such as Ethafoam and PolyPlank) |

|

|

| Acid-free tissue, unbuffered |

|

|

| Polyester quilt batting |

|

|

| Extruded polystyrene foam plank (such as Styrofoam) |

|

|

Step 4: use protective cushioning effectively

Protective cushioning provides consistent protection on all sides of an object. It is easy to apply to items that have simple shapes and durable flat surfaces. The challenges of cushioning objects with complex shapes or fragile surfaces can be addressed with mounts, fixtures or a double case system. Cushioning methods for several object types are described in Table 6.

| Object | Cushioning method |

|---|---|

| Unframed painting structure that is weak and susceptible to deformation | Add a travel frame that provides reinforcement and flat durable surfaces for cushion application (consult CCI Note 10/16 Wrapping a Painting). |

| Delicate ornate frame | Securely mount the frame inside an HTS frame and apply cushioning to the frame surfaces (consult CCI Note 10/16 Wrapping a Painting). |

| Fragile pottery item with projections | Use a negative mount that has voids carved around the small projections. This mount can then be cushioned or placed in a cushioned inner case. |

| Several fragile items that will be shipped together | Pack the items into the inner case of a double case system with suitable interleaves or mounts. Use durable partitions for heavy items. |

Cushioning can be achieved in a number of ways. This Note considers typical cushioning methods that include wrapping in resilient material such as bubble pack and the use of foam cushioning material.

© Government of Canada, Canadian Conservation Institute. CCI 132906-0001

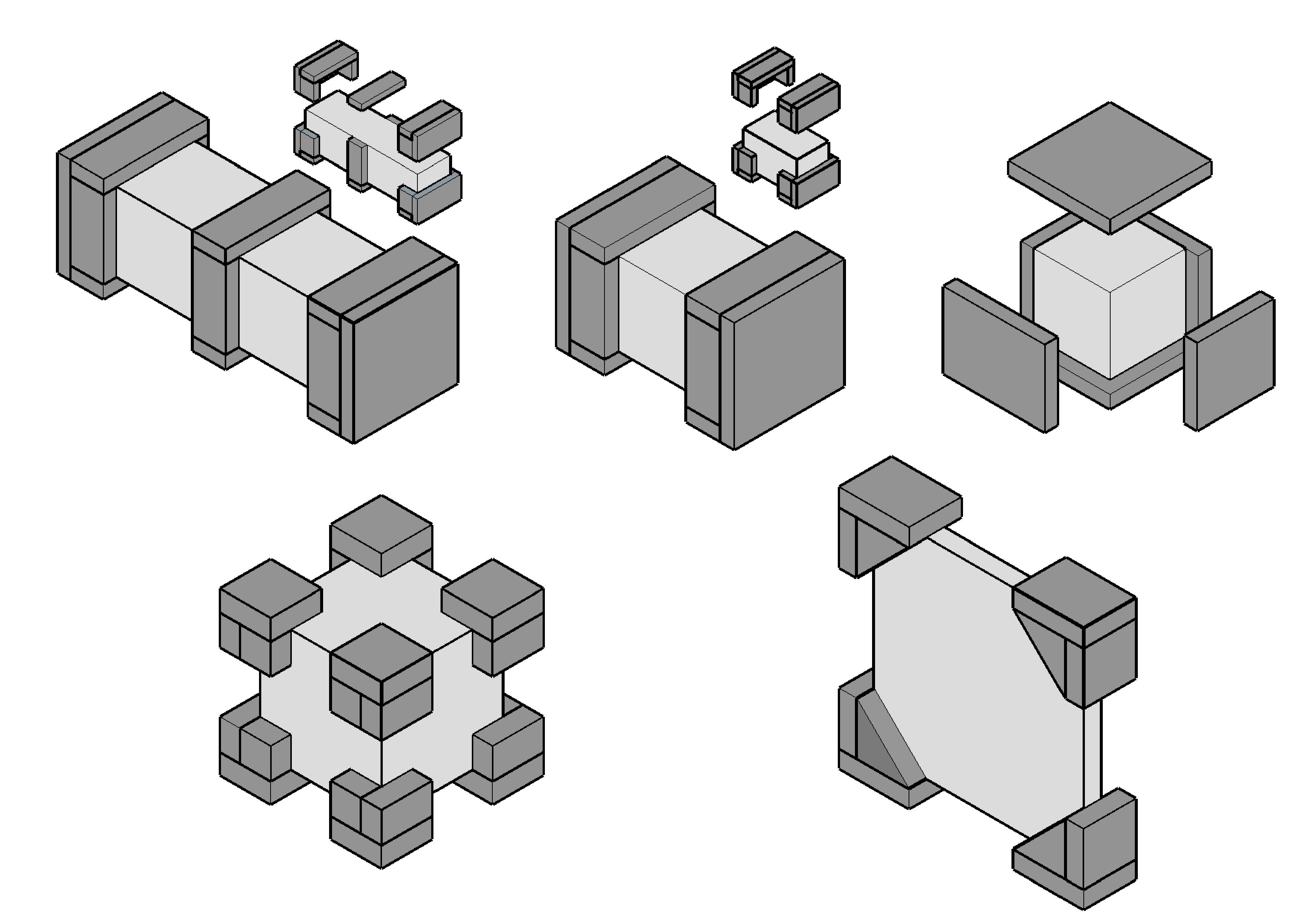

Figure 1. Pad layouts for several object shapes using foam sheet material. Objects can also be cushioned by using simple wrapping and padding methods, with attention paid to the load imposed on the cushioning material.

To verify that a material is being used correctly, divide the total weight (W) supported by the cushioning material by the area (A) of cushion coverage. Do this on each side if the coverage is different. If the result is within the load range shown in Table 7, the material is being used correctly; this means that the object can deflect into the cushioning but is not at risk of bottoming out. If the result is outside the range, adjust the coverage (increase or decrease A) or select a different material. Data regarding additional materials can be found in Technical Bulletin 34 Features of Effective Packaging and Transport for Artwork and in other references cited in the Bibliography, and it can be obtained directly from manufacturers.

Polyurethane ester foam is a good choice for cushioning. It is highly efficient, but it should not be placed in direct contact with object surfaces.

Polyethylene foam is chemically stable and easy to carve, making it a popular choice for mount-making applications. It is also a good cushioning material for heavy or moderately heavy objects.

Adequate thickness is an important feature of effective cushioning. As a general guide, cushioning should be at least 50 mm (2 in.) thick. For fragile items shipped through high hazard networks, a cushion thickness of up to 75 mm (3 in.) or 100 mm (4 in.) may be necessary.

Further to the basic cushioning advice provided here, CCI Note 20/2 Foam Corner Pads provides a list of pre-designed pads. CCI’s web-based cushion design calculator PadCAD is also freely available. This online tool applies cushion design methods used in commercial packaging and only requires basic information on the object, the shipping hazard and the desired cushion layout.

For effective shock and vibration isolation, everything that floats on the cushioning should be reasonably firm. The protected item should move on its cushioning with relative ease and behave as a single unit without any secondary movement of its own. The cushioning system should be the most flexible part of the protective package.

| Material | Description | Applications | Typical load range for cushioning (W/A) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polyurethane ester |

|

|

|

| Polyethylene |

|

|

|

| Bubble pack |

|

|

|

Step 5: find or construct appropriate shipping crates

The shipping crate is the first line of defence against shipping hazards. Lightweight crates may be suitable in controlled networks, but greater durability may be necessary in common shipping networks.

Light crating options include corrugated mirror boxes, triwall containers (consult CCI Note 1/4 Making Triwall Containers) and channel crates (consult CCI Note 20/1 The CCI Channel Crate: Making a Lightweight, Reusable Crating System). Wood crate specifications for domestic or overseas shipment of items weighing up to 454 kg (1000 lb.) are available as published standards.Footnote 1.

The minimum crate panel thickness in published standards is 9.5 mm (3/8 in.). In museum practice, 12 mm (1/2 in.) is a typical minimum thickness because the panels are flatter and easier to work with and there is not much difference in cost.

© Government of Canada, Canadian Conservation Institute. CCI 132906-0002

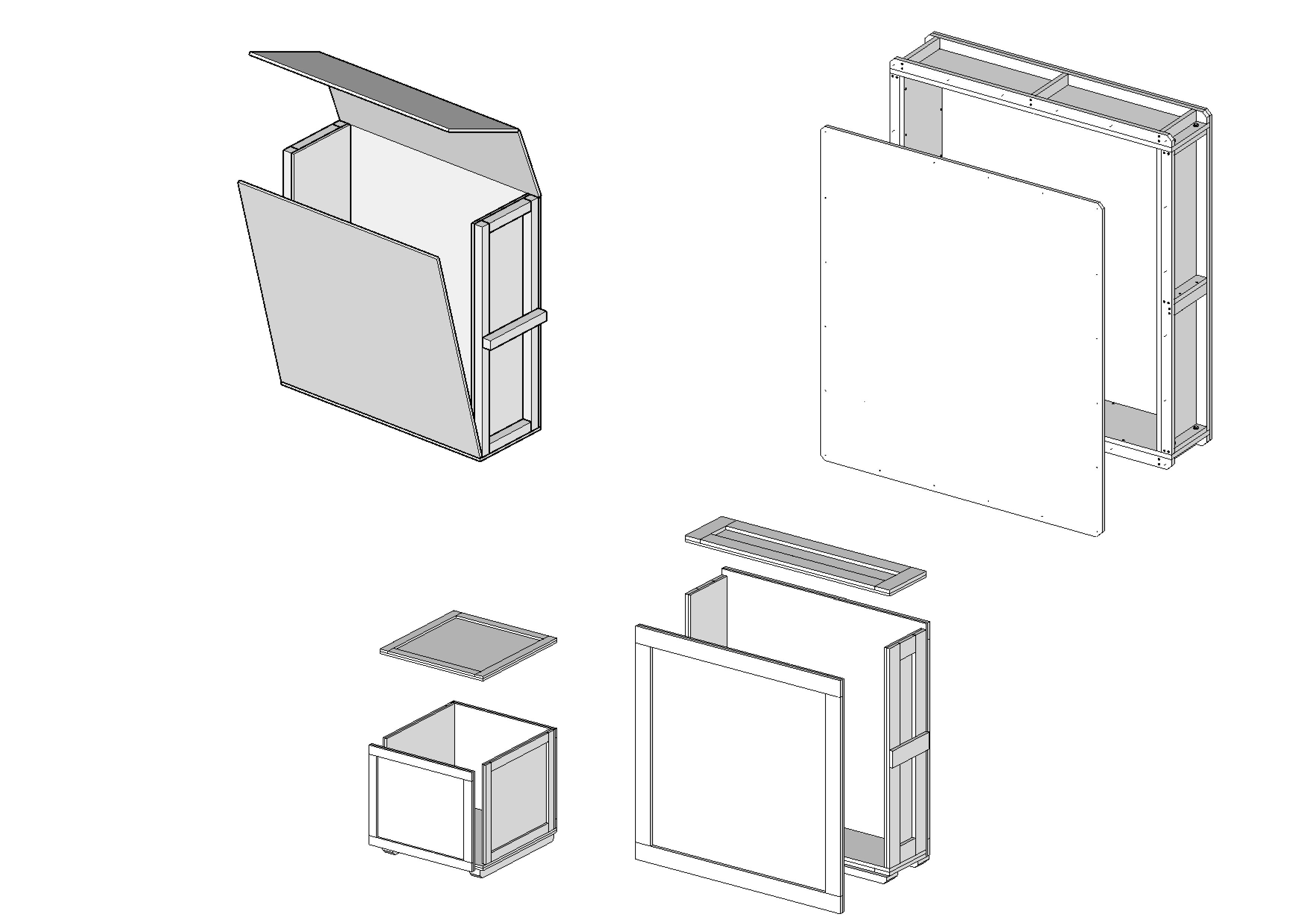

Figure 2. Three container options, clockwise from top left: a triwall container case, a CCI channel crate and two versions of an ASTM D6251 plywood crate.

Handles and skids will make it easier to move larger crates by manual and mechanical means. Careful handle positioning can reduce drop hazards by minimizing the height to which a package is raised during manual handling. Knee height is a good general guide for handle placement.

| Crate type | Description | Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Triwall container |

|

|

| CCI channel crate |

|

|

Basic shipping crate (such as ASTM D6251) |

|

|

Note that pest control regulations apply to all wood packaging material greater than 6 mm (1/4 in.) thick that is shipped to international destinations. This includes shipments between Canada and the U.S. At the time of writing, manufactured woods such as plywood, particleboard and waferboard were not subject to regulation. For up-to-date information on applicable regulations, consult the Canadian Food Inspection Agency, which administers the Canadian Wood Packaging Certification Program.

If objects are wrapped (in polyethylene, for example) and will not be stored in the case for long periods, they will be protected against contaminants. Thus, the case interior may be left unfinished. However, good construction detailing is still necessary to prevent the ingress of moisture and pests.

Applying a barrier to the inside surface of a wooden shipping crate can offer the following advantages:

- It helps block the entry of moisture.

- It provides a barrier against organic compounds released by the wood.

- It offers a smooth interior surface to improve cushion effectiveness and ease of packing.

Aluminum-coated polyethylene (Marvelseal 360) is highly effective as a moisture and pollutant barrier and offers a low-friction surface. A lower cost alternative to Marvelseal is to paint the case interior. However, performance is also lower. Painting is advisable if the case contents will be stored inside for long periods. The following paints are suitable for this purpose and will need to dry thoroughly (four weeks is recommended) before the case is used:

- acrylic latex paints

- acrylic-urethane emulsion paints

- two-part epoxies or urethanes

- moisture-cured urethane

Any paint or coating can be applied to the exterior of the shipping case. For the interior, some paints and coatings should never be used, as they give off compounds that could react with object materials. These include:

- oil-based paints

- alkyds

- one-part epoxies

- oil-modified urethane

Features of a good crate

- Handles are positioned for ease of handling and to minimize the drop height (for example, at knee height).

- Skids keep the larger cases off the ground and permit easy access for moving equipment.

- There are screw or latch closures for multiple packing cycles.

- Hardware is recessed so it will not break off.

- It is in good condition and well detailed (studies indicate that this may encourage better handling).

- It has discrete labelling, such as “fragile” or “handle with care.” Avoid labelling the crate as “art.”

© Government of Canada, Canadian Conservation Institute. CCI 132906-0003

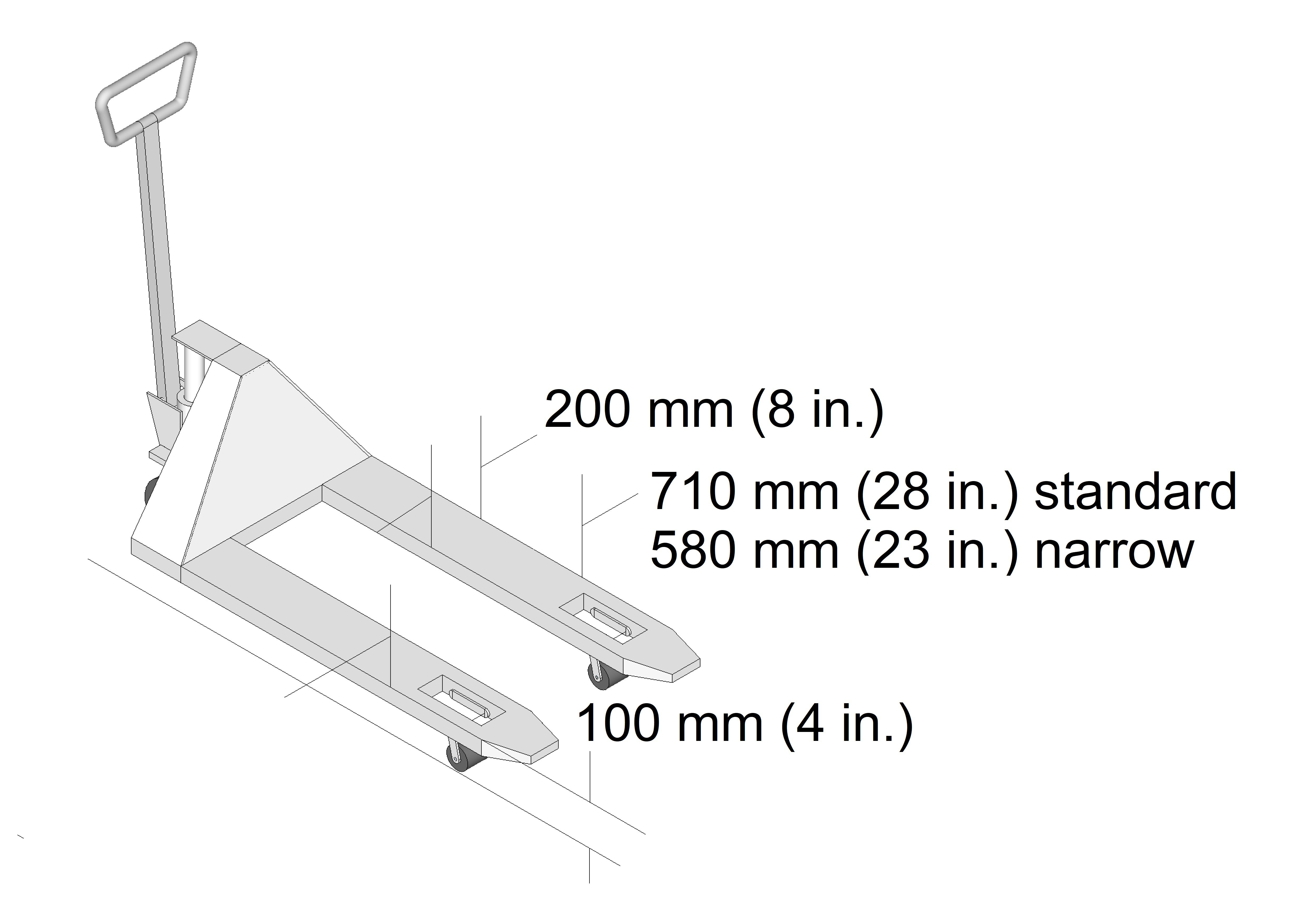

Figure 3. Pump truck dimensions to consider for large or heavy crates: distance between tines for standard and narrow pump trucks, typical tine width and typical raised height.

Final comments

The basic information provided in this Note can help provide more assurance of safe shipment for fragile items. For more detailed information on this topic, consult Technical Bulletin 34 Features of Effective Packaging and Transport for Artwork and the publications listed in the Bibliography. CCI also welcomes direct client enquiries about packaging problems and is happy to offer assistance.

Bibliography

Barclay, R., A. Bergeron and C. Dignard. Mount-making for Museum Objects, 2nd ed. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Conservation Institute, 2002.

Daly Hartin, D. Backing Boards for Paintings on Canvas, revised. CCI Notes 10/10. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Conservation Institute, 2017.

Marcon, P. Features of Effective Packaging and Transport for Artwork. Technical Bulletin 34. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Conservation Institute, 2020.

Marcon, P. Foam Corner Pads. CCI Notes 20/2. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Conservation Institute, 2021.

McKay, H., R. Arnold, W. Baker and D. Daly Hartin. Paintings: Considerations Prior to Travel, revised. CCI Notes 10/15. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Conservation Institute, 2015.

McKay, H., A. Morrow, C. Stewart, W. Baker and D. Daly Hartin. Wrapping a Painting, revised. CCI Notes 10/16. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Conservation Institute, 2015.

Mecklenburg, M.F. Art in Transit: Studies in the Transport of Paintings. Washington, D.C.: National Gallery of Art, 1991.

Schlichting, C. Working with Polyethylene Foam and Fluted Plastic Sheet. Technical Bulletin 14. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Conservation Institute, 1994.

Snutch, D., and P. Marcon. Making Triwall Containers. CCI Notes 1/4. Ottawa, ON: Canadian Conservation Institute, 1997.

Further reading

The Wooden Crates Organization. Box and crate standards. N.p.: Deploy Tech Services, LLC., 2020.

By Paul Marcon

© Government of Canada, Canadian Conservation Institute, 2021

Cat. No.: NM95-57/20-3-2021E-PDF

ISSN 1928-1455

ISBN 978-0-660-38050-6