Value of the Canadian Military Colleges

On this page

- Comparative Quality of Education, Socialization & Military Training

- Alternative Education & Training Models

- Costs

The question of whether the Canadian Military Colleges (CMCs) should remain in their current form or whether they require reform and/or restructuring ultimately hinges on their value – real and perceived – to the Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) and to Canada. At the heart of this calculation lies the threshold issue that provided the genesis of the Board’s mandate in the first instance: harmful conduct and culture, and particularly the issue of sexual misconduct. (NB: For the purposes of this Report, “sexual misconduct” has been used as an umbrella term to capture all conduct deficiencies of a sexual nature, harassment of a sexual nature and crimes of a sexual nature.) The Board reflected extensively upon this issue and returned to it many times.

Had the Board determined that – as posited in the Independent External Comprehensive Review – negative conduct and culture at the CMCs is so entrenched, widespread and systematic that the institutions are inherently problematic and irrevocably broken, the Board would have argued for their closure, despite having ideas regarding how they could be improved in other respects. Had the evidence pointed to institutions rife with toxic masculinity or racism or misogyny or homophobia, for example, whose origins were embedded within the marrow of the Military Colleges, the Board would not have hesitated to conclude that the cost to the CAF and to Canada of maintaining them was too high a price to pay given the harm they caused, regardless of their history, utility, relevance or symbolism.

This was not the case. In their current state, the Board found no singular fatal flaw, toxic mix of circumstances or irredeemable structural weakness that would call for their demise.

The Colleges are not perfect – far from it. There are elements intrinsic to their nature as military institutions, such as hierarchy, emphasis on physical prowess and a culture of deference to authority, that give rise to problematic notions of what it takes to be an officer. There are aspects of their character as residential institutions, with a high percentage of male Naval and Officer Cadets (N/OCdts), that present ongoing challenges, contributing to a concerning disconnect between the experiences and perceptions of men and women at the CMCs. And there are events that have happened on their grounds and in their facilities that are deeply traumatic and harmful – ranging from attitudes to actions, from the subtle to the explicit, from the distasteful to the unlawful. This combination of factors must be meaningfully and consistently addressed; it is shameful that anyone who has chosen to serve our country experiences harm in the very places where they have come to join the Profession of Arms.

But there is also deep value in what the Canadian Military Colleges offer to the CAF and to the country, and tremendous potential for them to deliver even more for Canadians.

The Board arrived at this conclusion by evaluating the quality of education, socialization and military training provided to N/OCdts compared to those entering the CAF via other officer entry streams (who have earned degrees at civilian universities), and in relation to the experiences offered at foreign military academies. It also examined the advantages and drawbacks of the CMCs as currently structured and run, particularly compared to alternative education and training models, and assessed the overall benefits they offer in relation to the costs they incur. The Board further examined six interconnected thematic areas that impact the CMC’s overall effectiveness, relevance and health:

- Identity;

- Governance;

- Program Structure;

- Peer Leadership Model;

- Conduct, Health & Wellbeing; and

- Infrastructure, Operations & Support.

The findings and analysis that flowed from this exercise form the backbone of the Board’s recommendations. Taken together, these recommendations will spur enough meaningful reform to help realize the full potential and significant value of the Military Colleges as important national institutions that are critical to Canada in this period of growing global competition, insecurity and change. It is the hope of the Board that its observations and recommendations will also help honour the experiences of all of those who have been, and continue to be, part of the fabric of Canada’s Military Colleges.

Comparative Quality of Education, Socialization & Military Training

In Relation to Other Entry Streams

There exist multiple mechanismsFootnote 10 through which to become an officer in the Canadian Armed Forces; however, three entry streams in particular represent 90% of the recruitment of officers every year: the Regular Officer Training Plan - Canadian Military College (ROTP CMC), the Regular Officer Training Plan - Civilian University (ROTP Civ U) and the Direct Entry Officer Program (DEO). The Board has therefore limited its analysis of the CMCs to comparisons with the ROTP Civ U and DEO streams only.

Underpinning this analysis is the Board’s view that, while having multiple entry streams may pose challenges in terms of standardization across the CAF, that is greatly outweighed by the value that the diverse backgrounds, perspectives and life experiences of its officers bring to the Canadian Armed Forces. A variety of entry streams is beneficial for an all-volunteer military in other ways as well: it supports recruiting by offering entry at different life stages, it fills key occupations by drawing candidates with different areas of expertise, and it supports the rapid expansion of military forces, if required.

As such, the Board accepts that there is variety in the programmatic elements of each entry stream, and that what may be identified as positive/valuable/effective for one stream does not necessarily need to be replicated in another. In sum, the benefits of diversity outweigh the establishment of any common denominator across the entry streams, beyond Basic Training and the requirement to hold an undergraduate degree from an accredited institution.

This degree requirement stems from a recommendation in Defence Minister Douglas Young’s 1997 Report to the Prime Minister on the Leadership and Management of the Canadian Forces, which responded to findings and recommendations in the Report of the Commission of Inquiry into the Deployment of Canadian Forces to Somalia.Footnote 11

The Board considered whether to revisit the requirement for officers to hold undergraduate degrees and decided against doing so; the Canadian Military Colleges Review Board (CMCRB) supports the rationale upon which this requirement is based and believes that it still holds. The judgment, critical thinking skills, foundational knowledge and personal growth that are cultivated in response to the demands of a university-level education remain as important, valuable and impactful now as they were when the decision was first taken. The Board is firm in its view that the CAF, and Canada, are better served by having a university-educated officer corps.

Beyond a few exceptions for particular occupations within the Profession of Arms, however, the CAF does not prescribe any specific type of degree, and therefore degrees from all civilian universities in Canada are accepted to meet this requirement. Moreover, the CAF is agnostic with respect to how incoming officers meet their academic degree requirements (which are typically set by their universities), so long as, when applicable, those requirements satisfy external oversight requirements (such as professional accreditation bodies like the Engineers Canada Accreditation Board).

Education

In light of the above, the starting point for comparison between the three entry streams is not whether an officer has a degree or what degree they hold, but rather whether the quality of that degree varies between entry streams. Because candidates in the DEO and ROTP Civ U streams earn their degrees via civilian universities, this would require the Board to compare the quality of every institution from which an officer in the CAF has earned a degree, in relation to all the other institutions, including the CMCs, and vice versa.

This is near impossible; the wide range of degree offerings, credit requirements, types of institutions, number of students and professors, geographic locations, course delivery modes and program structures, among other variables, make undergraduate educational experiences across the Canadian university landscape rich, yet highly individualized. For example, to try to compare a small, residential English-language university in Quebec like Bishop’s University to a multi-campus research-intensive institution with a high commuter population like Simon Fraser University, let alone to compare Canada’s Military Colleges to the diverse array of civilian universities across the country, particularly in terms of quality of the education, is an impractical and unhelpful exercise.

What all of these organizations have in common, however, is that they are accredited institutions of higher learning that have been granted the power to confer degrees via provincial legislative authority. In satisfying the Quality Assurance Framework of their respective provincial oversight bodies via an Institutional Quality Assurance Process (IQAP), they are considered credible by the academic community, by society and by applicable professional oversight bodies.

As such, the Board accepts that degrees granted by the Canadian Military Colleges, in line with the legislative authorities conferred upon them by the provinces of Ontario and Quebec, and in compliance with the requirements of their respective Quality Assurance Frameworks, are of equal quality to any other undergraduate degree from any other civilian university in Canada (or nationally recognized international institution), and the CMCRB holds them to be of equal value.

Separate from variations in the academic experiences of officers coming from all three entry streams, there are three key differentiators in the academic experience between ROTP CMC and both ROTP Civ U and DEO: the Core Curriculum, second language training and physical fitness activities.

While its current structure and delivery model are ripe for change, the objectives of the Core Curriculum remain valid. The ability to leverage the Core Curriculum to deliver tailored academic offerings in areas of specific interest to the CAF, and to provide a depth and breadth of study directly related to the Profession of Arms, is a unique feature of the CMCs. Moreover, it offers a broad liberal education which teaches skills such as critical thinking, and it exposes N/OCdts to different academic disciplines and different ways of thinking, analyzing and communicating. Equivalents to the Core Curriculum are not generally found in civilian universities, and it therefore provides great value to those enrolled in the ROTP CMC.

Although Bilingualism stands as its own Pillar under the 4-Pillar Model, second language training forms a de facto part of the academic experience for most N/OCdts, as they are required to attend language classes until they achieve an Intermediate Level of Bilingualism (BBB)Footnote 12, as a prerequisite for earning their degree. This dedicated second language training is a unique and valuable opportunity in a bilingual country and within a bilingual institution: it yields significant positive outcomes for the N/OCdts in terms of promotion rates and skill development, as well as meaningful institutional outcomes in terms of communication, cultural integration and cost savings. Few, if any, Canadian civilian universities offer such training, making it another unique feature of the Military Colleges that the Board views as particularly valuable and noteworthy.

Physical Fitness also stands as its own Pillar but, until recently, successful completion of a physical performance test was included as a criterion for earning an academic degree and thus factored into the Board’s consideration of the comparative value of the CMC’s academic program. Moreover, both CMCs require N/OCdts to attend physical education classes for the duration of their program, the content of which varies slightly between the two Colleges. Offered as non-credit mandatory courses, these classes include a mix of lectures, individual and group physical fitness activities, and sports. This is a unique feature of the CMCs, but not an exclusive one: a number of civilian universities offer physical fitness activities within their academic programs, albeit typically within Kinesiology and other health-related programs. As such, while the Board sees value in an emphasis on health and fitness, the current ROTP CMC construct provides only a minimal comparative advantage in this domain.

Socialization

The Board has interpreted “socialization” as referring to the process of becoming a member of the Profession of Arms. This process of coming to understand norms and expectations, accepting beliefs and embracing values comprises a variety of elements including mindset and lifestyle changes. It represents the transition between civilian life and life as a member of the collective professional body that is empowered to use force on behalf of Canada. More specifically, this transition reflects the personal journey of each member as they acquire the appropriate knowledge, skills, abilities and attributes to become a leader in an institution charged with the use of organized violence. This process can be difficult for many people, and particularly for junior officers who are new to the profession and who must be prepared to apply deadly force or expose themselves to lethal dangers, and order others to do so as well.

The Basic Military Officer Qualification (BMOQ) course, Parts 1 and 2, which all new officers must take, coupled with training specific to each member’s occupation, is designed to facilitate this transition and deliver the functional and organizational competencies necessary for success in their first jobs in the military. These training courses further include material on the CAF EthosFootnote 13 as well as on The Fighting SpiritFootnote 14 and its reflections and directives on the Profession of Arms in Canada.

Although ROTP Civ U entrants are members of the CAF while completing university, they have limited engagement with the CAF regarding the Profession of Arms until they graduate. DEO entrants have none. As such, these members will often find themselves leading soldiers, sailors and aviators, with minimal to no previous experience and with generally less than one year of combined basic and occupation training.

As was shared with the Board during the Listening Sessions held at CAF bases, this transition from civilian to officer in the Canadian Armed Forces can feel abrupt and can present a steep and challenging learning curve. While this does not impair the longer-term integration and success of ROTP Civ U and DEO entrants, many of these individuals indicated that they felt inadequately prepared at the outset of their careers to flourish in their new roles, particularly compared to their peers who attended a Military College. Nevertheless, the life experience that the ROTP Civ U and DEO entrants often bring with them to the CAF – based on things like travel, time at civilian universities and previous exposure to the workforce – are valuable to the institution and serve these members well in terms of their maturity, confidence and judgment.

ROTP CMC entrants experience a no less rapid transition from civilian society into the military, but they have a four-year period of gradually increasing responsibilities to adjust to the idea of being a member of the Profession of Arms. The CMCs dedicate significant time and effort to developing the principles of leadership, professionalism and ethics that form the foundation for continued service in the CAF, as delivered through the Core Curriculum, the Cadet Chain of Responsibility (CCOR) and the Military Pillar, all of which place particular emphasis on teamwork and leadership.

Notwithstanding the shortcomings of the Core Curriculum, the CCOR and the military training (all of which are discussed in detail below), exposure to these three elements plays an important role in habituating N/OCdts to the challenges and opportunities of military life. They typically move into their roles as junior officers with greater ease and with a higher level of comfort vis-a-vis the expectations and responsibilities that accompany these early posts; data collected during CMCRB Listening Sessions at 5th Canadian Division Support Base Gagetown, at Royal Canadian Air Force 12 Wing Shearwater and at Canadian Forces Base Halifax - which focused extensively on engagement with recent CMC graduates, with recent ROTP Civ U and DEO entrants and with the supervisors of these newly commissioned officers – showed that graduates from the CMCs typically came into their roles as junior officers with a higher degree of familiarity with the military, greater comfort in taking on leadership roles, and a deeper baseline knowledge in areas of relevance to the mandate and mission of the CAF.

While these were viewed as positive outcomes, participants in the Listening Sessions also noted that CMC grads often carried with them a reputation for arrogance or a lack of humility, had limited “adult” life experience outside of the military, and were frequently less mature than their non-ROTP colleagues. Moreover, it was noted that the benefits of having gone to Military College were largely neutralized within a couple of years, and that commanding officers were rarely able to differentiate between an ROTP CMC graduate and their ROTP Civ U or DEO counterparts once the officers had fully entered the workforce.

The limited literature regarding the comparative impact of socialization between various officer entry streams paints a slightly different picture. A 2018 internal Department of National Defence (DND) study assessed the impact of entry stream on career development and retention rates from 1997 to 2018. While the study noted that no high-quality data exists in any CAF system of record that can be used to distinguish officer entry streams with confidence, and that interpretation of correlated data was required to determine the actual entry stream, it nevertheless found that

- CMC graduates were promoted from Captain/Lieutenant (Navy) to Major/Lieutenant-Commander and from Major/Lieutenant-Commander to Lieutenant-Colonel/Commander more quickly than graduates from other entry streams;

- CMC graduates had significantly higher levels of second language abilities, particularly at the level of Captain/Major and Major/Lieutenant-Colonel;

- CMC graduates had lower attrition rates than the officers from other entry streams in the short, medium and long terms; and

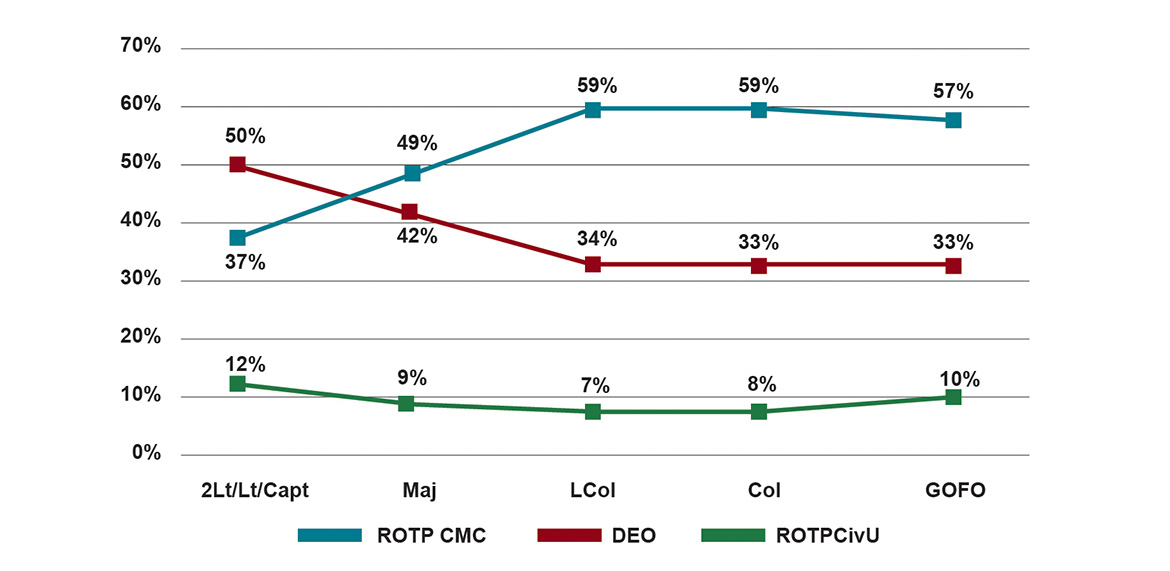

- CMC graduates were found to make up a relatively high proportion of CAF senior ranks at the levels of Lieutenant-Colonel/Commander and higher (Figure 2).

Figure 2: CAF Officers by Entry Program and Rank, 2018 - Text version

| Rank | Total number at the CMC | Percentage of CMC | Number of DEO/OCTP | Percentage of DEO/OCTP | Number of ROTP CivU | Percentage of ROTP CivU |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2Lt/Lt/Capt | 1845 | 37% | 2478 | 50% | 601 | 12% |

| Maj | 958 | 49% | 818 | 42% | 167 | 9% |

| LCol | 490 | 59% | 278 | 34% | 59 | 7% |

| Col | 148 | 59% | 82 | 33% | 19 | 8% |

| GOFO | 57 | 57% | 33 | 33% | 10 | 10% |

Legend:

|

||||||

Despite challenges in accessing clean data, the Board was able to draw some additional insights into the issue of quality of socialization by assessing the percentage of General and Flag Officers (GOFOs) (senior leaders in the CAF at the rank of Brigadier-General/Commodore and above) and those at the rank of Colonel/Captain(Navy) who are graduates of the CMCs, versus graduates of the other entry streams. The results are notable: in fiscal year 2023/2024, 67% of GOFOs and 58% of Colonels/Captains(N) were CMC graduates – an upward trend for GOFOs and a similar proportion for Colonels/Captains(N) compared to the 2018 results.

The degree to which CMC graduates are represented among the highest ranks in the CAF is particularly striking, as only about 33% of the CAF’s officer corps is drawn from the Military Colleges. However, it is less surprising when one takes into account the fact that CMC graduates are more likely to remain in the CAF for longer than ROTP Civ U or DEO entrants, and therefore have a higher chance of being promoted. This assessment does not factor in the impact that military training, leadership development and networking at the CMCs may also have on these disproportionately high rates.

Either way, the initial investment in the ROTP CMC appears to pay long-term dividends for the CAF; although a definitive causal link is difficult to prove, such statistics cannot be discounted. The Board is of the view that the socialization which occurs at the CMCs for young, newly minted N/OCdts is formative and is likely connected to their sense of commitment to a lifetime of service in the CAF. While not proof of the quality of socialization they receive at the Military Colleges, it nevertheless speaks to the importance of the CMCs for new recruits in supporting their transition from civilian to military life.

The Board observed that the CAF is less successful at recruiting into the DEO stream than into ROTP (both CMC and Civ U) for almost all occupations. A comparison between the success of recruiting under the ROTP and DEO entry streams reveals a large disparity between the performance of the two programs. The seven-year average for success in recruiting into the ROTP is 92%%; for the DEO stream, it is 70%. In pure numbers, over those seven years the ROTP recruited 3,125 people on a target of 3,386, while the DEO stream recruited 2,658 people on a target of 3,811.

DEO recruiting success was not evenly distributed across occupations. Occupations such as Pilot (92%), Intelligence Officer (133%), and Military Police Officer (127%) had great success recruiting DEOs; however, occupations that require a science or engineering degree such as Electrical and Mechanical Engineer (43%), Army Engineer (34%), Communication and Electronics Engineer (53%) and Naval Combat Systems Engineer (55%) struggled to recruit DEOs, even with recruiting incentives of up to $40,000. In all cases, the ROTP entry stream for occupations that require a science or engineering degree achieved significantly greater success than the DEO entry stream (100%, 90%, 97%, and 77% respectively).

The key takeaway here is that the ROTP contributes substantially to the recruitment of Canadians into the CAF and provides considerably greater recruiting success for occupations that require a science or engineering degree.Footnote 15

The Canadian Military Colleges also contribute positively towards achieving the employment equity goals of the CAF (Figure 3). The statistics demonstrate that representation of designated groups (in particular, women and visible minorities) consistently trends significantly higher at the CMCs than in the general CAF population and exceeds CAF officer statistics. This represents a meaningful contribution to the CAF’s overall approach to addressing the historic underrepresentation of designated groups within the military. Conversely, the representation of Indigenous peoples and persons with disabilities at the CMCs remains at or below overall CAF representation trendlines. More generally, the underrepresentation of Indigenous peoples within the CAF officer corps remains a challenge. Special measures, especially the Indigenous Leadership Opportunity Year (ILOY) at RMC, endeavour to address this issue, and such efforts should continue.

Figure 3: 5-Year Comparison Table for CAF Employment Equity Designated Groups

| Employment equity statistics, by year, for the CMC and the CAF | Women | Visible Minorities | Indigenous Peoples | Persons with Disabilities |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CMC Stats | 20.9% | 16.6% | 2.3% | 0.8% |

| CAF Officer Stats | 19.7% | 12.5% | 1.9% | 0.7% |

| CAF General population stats | 15.9% | 9.4% | 2.8% | 1.2% |

Legend:

Notes: These statistics were provided by the Director Inclusion from the Canadian Forces Employment Equity Database. The statistics were derived from voluntary self-identifications of Officer/Naval Cadets at the Canadian Military Colleges. |

||||

| Employment equity statistics, by year, for the CMC and the CAF | Women | Visible Minorities | Indigenous Peoples | Persons with Disabilities |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CMC Stats | 21.9% | 19.3% | 2% | 0.5% |

| CAF Officer Stats | 19.9% | 13.1% | 2.0% | 0.7% |

| CAF General population stats | 16.3% | 9.5% | 2.8% | 1.1% |

Legend:

Notes: These statistics were provided by the Director Inclusion from the Canadian Forces Employment Equity Database. The statistics were derived from voluntary self-identifications of Officer/Naval Cadets at the Canadian Military Colleges. |

||||

| Employment equity statistics, by year, for the CMC and the CAF | Women | Visible Minorities | Indigenous Peoples | Persons with Disabilities |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CMC Stats | 22.7% | 22.1% | 3.1% | 0.6% |

| CAF Officer Stats | 20.2% | 14.2% | 2.0% | 0.6% |

| CAF General population stats | 16.3% | 10.8% | 2.9% | 1.1% |

Legend:

Notes: These statistics were provided by the Director Inclusion from the Canadian Forces Employment Equity Database. The statistics were derived from voluntary self-identifications of Officer/Naval Cadets at the Canadian Military Colleges. |

||||

| Employment equity statistics, by year, for the CMC and the CAF | Women | Visible Minorities | Indigenous Peoples | Persons with Disabilities |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CMC Stats | 23.5% | 26.1% | 2% | 0.7% |

| CAF Officer Stats | 20.4% | 15.7% | 2.0% | 0.8% |

| CAF General population stats | 16.5% | 12.0% | 3.1% | 1.2% |

Legend:

Notes: These statistics were provided by the Director Inclusion from the Canadian Forces Employment Equity Database. The statistics were derived from voluntary self-identifications of Officer/Naval Cadets at the Canadian Military Colleges. |

||||

| Employment equity statistics, by year, for the CMC and the CAF | Women | Visible Minorities | Indigenous Peoples | Persons with Disabilities |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CMC Stats | 21.8% | 26.2% | 1.9% | 0.6% |

| CAF Officer Stats | 20.6% | 16.4% | 2.0% | 0.8% |

| CAF General population stats | 16.5% | 12.2% | 3.0% | 1.2% |

Legend:

Notes: These statistics were provided by the Director Inclusion from the Canadian Forces Employment Equity Database. The statistics were derived from voluntary self-identifications of Officer/Naval Cadets at the Canadian Military Colleges. |

||||

Military Training

DEO, ROTP Civ U and ROTP CMC entry streams all participate in the BMOQ course, Parts 1 and 2, and this common training is the only requirement for commissioning. As such, the single differentiating element between the military training experiences of N/OCdts and their ROTP Civ U and DEO counterparts – prior to occupation-specific training – is the additional training that N/OCdts receive at the CMCs under the auspices of the Military Pillar.

Military training at the CMCs – as currently structured and delivered – leaves much to be desired; the program standard and training plans are ad hoc, vague and misaligned between the two Colleges, the time allocated to developing military skills and leadership is not sufficiently prioritized, and the Cadet Chain of Responsibility that is intended to equip N/OCdts with practical leadership learning opportunities is not currently fulfilling that function. The result is a Pillar that has no clear purpose and is not particularly effective. It is also the area in which more than 70% of recent graduates wish they had learned more during their time at the CMCs.Footnote 16

Ultimately, military training at the CMCs has no comparator in the ROTP Civ U or DEO streams, and therefore its quality cannot be assessed against other programs. Unto itself, however, a lack of rigour around the design and implementation of the Military Pillar has seriously undermined the important function of the CMCs as exceptional leadership institutions of singular value to the CAF and to Canadian society. The creation of a systematic, standardized and well-sequenced military training program should help create a greater sense of identity and a clearer sense of value at the CMCs, as well as an improved product in terms of the development of officers with better character and greater leadership capabilities. In the pursuit of these objectives, the CAF cannot be satisfied with mediocrity; a revised military training program must strive for excellence.

In Relation to Foreign Military Academies

Canada is not alone in its need to produce military officers to serve in the nation’s armed forces or in its decision to establish dedicated institutions responsible for doing so. Across the world, allies and partners are seized with the critical importance of educating and training young officers in support of their defence and security requirements, and they have developed a wide variety of models to meet these needs.

The Board had the opportunity to engage with, visit and learn from a range of countries – from NATO Allies to traditional and non-traditional defence partners across North and South America, Europe, the Indo-Pacific and Africa – all of which have some sort of military academy/academies that provide training for their officer corps. While no two models are alike, and each reflects the particular history, social values, demographic profile and geopolitical context of its respective country, these military academies nevertheless share some common objectives, similar philosophical underpinnings and comparable challenges.Footnote 17

These include a commitment to investing in education and training as the backbone of a strong military – present and future; a focus on equipping cadets with the appropriate skills, knowledge, character and competencies to become effective officers as well as skilled leaders and upstanding citizens; and a determination to ensure that their professional military educational institutions remain relevant and responsive to the needs of their armed forces.

Many of them are also grappling with misconduct issues that are not dissimilar to the challenges faced at the CMCs, particularly since many of the foreign academies are also fully residential and have co-educational dormitories. This is particularly true of other Western countries, whose military cultures are evolving alongside rapid societal change – often in response to scandals, public outcry, and negative incidents – and who face tremendous pressure to keep up.

Although these issues are not necessarily seen as prevalent or pressing by all interlocutors, most foreign military academies have developed, or are developing, policies and procedures to address misconduct in a variety of forms, and in all cases have demonstrated a commitment to continual improvement. The United States Naval Academy’s Sexual Assault Prevention and Response program,Footnote 18 the Royal Military Academy Sandhurst’s Critical Mass trial,Footnote 19 and the Norwegian Military Academy’s Mitt Lag (My Team) initiative provide meaningful examples of these efforts.

Another point of commonality is that most countries intake officers through multiple entry streams, rather than relying on their military academies alone. These entry streams typically include a mix of

- academic bursary/scholarship programs to support N/OCdts attending civilian university,

- direct entry from civilian university programs, and

- prior-service commissioning schemes (wherein former non-commissioned members are able to commission without requiring a degree).

For example, the Australian Defence Force (ADF) recruits officers to the Australian Defence Force Academy; offers a Defence University Sponsorship scheme that subsidizes education at civilian universities in exchange for service in the military; recruits university and high school graduates directly into its officer corps to attend one of the ADF’s three service training academies; and offers a pathway for non-commissioned members to transition to become officers.

Notwithstanding these similarities, the respective geopolitical ambitions of each country, alongside public attitudes towards their military and their levels of defence spending, all make a difference in how foreign partners and allies treat professional military training and education. This is reflected in both structure and substance.

In most cases, foreign militaries deliver officer basic training by service academies (army, navy, air force) or training schools, not by a joint (tri-service) training school. For example, in the United States each of the three services operates independently and provides an officer training and education program that is specific to the unique requirements of its service. Canada is among the minority of countries that have combined all services to deliver a joint basic officer training program, and this is currently provided by the Canadian Forces Leadership and Recruit School (CFLRS) in Saint Jean-sur-Richelieu, Quebec.

Therefore, while all officers in the CAF go through the same common and service-specific training phases as other armed forces, the CMCs do not play a meaningful role in this process; military training at the CMCs is not part of common training requirements and has not been well structured or standardized in the way it is in comparable foreign institutions.

Moreover, while several nations have established a joint military academy that provides an undergraduate degree alongside military training (i.e., Australia, Japan, Belgium, Germany), this joint military training is supplemented by occupation training that is delivered by service-specific military training organizations. Meanwhile, in the Canadian context, service/occupation-specific training at the CMCs remains largely absent and unstandardized across the services, falling short of the structured approach taken by most other nations.

Thus, while each country has its own distinct approach to the common and service-specific training phases, and while Canada is unusual in having a joint model, most countries nevertheless better leverage their military academies to deliver military training. At present, the CMCs are not contributing in a formal, measurable or systematic way to either common training or service-specific training, calling into question the value of the Military Pillar, not just unto itself, as noted above, but in particular as compared to other militaries.

The varying degrees of emphasis placed on academics versus military training is another key differentiator between the various models. Some countries, such as the United Kingdom and Australia, do not require a university degree for entry into their military academy, let alone for commissioning, while others call for an undergraduate degree as a pre requisite for entry into the academy (e.g., Denmark). Yet others deliver an undergraduate education as part of the military academy program (e.g., Sweden, United States, Brazil, Philippines, Norway, Japan, Belgium and South Africa). In this latter context, the program can take several forms, such as delivering academics and military training concurrently or taking a mixed/sequential approach. Some separate military training entirely in time and space from academic studies. For example, in Germany, the military relies on civilian academics who are separate from the State to educate their officers, and on their military to train their officers, and these periods of study and training occur independently of one another.

In some instances, the academic education is delivered by the provider of military training (like Brazil’s Military Academy of Agulhas Negras), whereas in others the academic education is outsourced to another governmental institution (like the Norwegian Defence College) or a private service provider (like the University of New South Wales in Australia). In all cases, there is a high degree of clarity regarding the intent, objectives and expected outcomes of the academic program in relation to its relevance to its country’s armed forces, a factor that is missing from the broad academic offerings of the CMCs.

Additionally, while various actors may be responsible for different aspects of the program delivery, the relationship between the military academy and its armed forces is typically strong; practices such as ongoing feedback sessions, formalized dialogue opportunities or the regular surveys seeking input from the services that the Philippine Military Academy uses, help ensure that the military academies remain relevant and that the skills, knowledge, character and capabilities of newly commissioned officers meet the overall needs of their armed forces.

In situations where a degree is required, almost all countries take a narrow approach to program offerings. For example, the Swedish Defence University offers only three “profiles of study” as part of their Officer Programme (military science, military technology or naval science), all of which lead to a Bachelor of Military Science, while the Philippines Military Academy offers a number of areas of study (including Humanities, Management, Psychology and International Relations) but only grants a single Bachelor of Science degree with a major in Security Studies. The academic program at the United States Naval Academy is focused on science, technology, engineering and mathematics programs, in order to meet the U.S. Navy’s technical needs, and offers only one degree – a Bachelor of Science – albeit with 26 options for majors.

Within their degrees, many academies still require Cadets to take some form of core curriculum. However, this takes a wide variety of forms, and in most cases it manifests through a more standardized approach to leadership training that includes elements of the liberal arts.

In terms of physical and psycho-social infrastructure, investment varies, although all countries acknowledge the importance and value of a high-quality environment on the health, wellbeing and learning outcomes of their Cadets. On-campus support and access to health and wellbeing resources also vary widely, and in this regard, the CMCs are leaders from whom many other countries could learn; access to resources and on-campus support networks are among the most comprehensive and robust at the CMCs as compared to most other academies, and the CMCs also benefit from fitness facilities that are of exceptionally high quality compared to many other countries.

Apart from Belgium, the specific challenges facing Canada as a bilingual country do not exist elsewhere, such as the requirement to deliver the programs at the CMCs in both Official Languages. Very few military academies require second language training, though many offer second language courses; typically, when they do, the second language offered is English. As such, it is of limited value to draw on lessons learned from other military academies to apply to the CMCs in terms of second language training.

In sum, it is clear that there is no “right model” for delivering professional military training and education, nor is there a “better model” – each comes with particular strengths, weaknesses, drawbacks and opportunities specific to its distinct context. The Canadian model shares touchpoints with other militaries but is unique to Canada, and for good reason: there are numerous features of Canada, and the CAF, that require a one-of-a-kind approach, including linguistic duality, diversity and equity considerations, geography and joint training, that cannot simply be pulled from other models.

Nevertheless, there are myriad opportunities for the CMCs to look to, and be inspired by, best practices among other countries, even if they may not be fully applicable. For example, in Nordic countries selective conscription allows those nations to influence the demographic composition of their military and can result in a greater percentage of female members being recruited into the military than is common for volunteer-service forces. While Canada is not moving towards a conscription model, understanding the impact of having a critical mass of women is nonetheless valuable in terms of influencing recruitment strategies and program design. The Royal Military Academy Sandhurst’s Critical Mass initiative noted above – in which some training platoons will boost the number of women cadets to 30% in order to help offset the negative pressures associated with women being a small minority in an otherwise male-dominated living, working and study environment – provides another example from which we can learn.

More generally, Canada can draw lessons from the attitude and mindsets driving all of the foreign military academies. They are unequivocal about the importance of their armed forces in defending their national interests, values and ways of life, and are therefore unapologetic about the imperative to prepare their junior officers to be able to fight and win in the contemporary geopolitical security environment. They view their military academies as extensions of their armed forces and use them as tools of military diplomacy, as centres of leadership excellence, as symbols of strength and as vehicles for projecting power. They take their success seriously.

The Board was inspired by the thoughtful and deliberate approach taken by the Swedish Defence University to its public art collection – designed to stimulate deep reflection on themes of war and peace, defence and security. It was motivated by the efforts of the Norwegian Defence College, which runs a sought-after leadership course every year that is so highly respected that it counts national leaders and industry scions among its regular participants. It was persuaded by the Australian Defence Force Academy’s belief in the value of psychosocial infrastructure as tool for addressing issues such as health and wellbeing, community cohesion and risk reduction. It was moved by the importance of tradition, connection to history and sense of place that the Karlberg Military Academy and the United States Naval Academy evoked through the high quality of their buildings and grounds. And it was impressed by the way in which the Royal Military Academy Sandhurst leverages adventure training, experiential learning and field exercises to teach N/OCdts to foster deeper relationships with self, grapple with fear, develop courage and learn to manage risk. These are just a few of the ways in which the CMCs and the CAF can learn and benefit from the experiences, expertise and approaches of Canada’s partners and allies.

Alternative Education & Training Models

An assessment of whether Canada’s Military Colleges as currently structured are effective in generating the professional officer corps required by the Canadian Armed Forces – which in turn speaks to the overall value proposition of the CMCs – benefits from a comparison to alternative models.

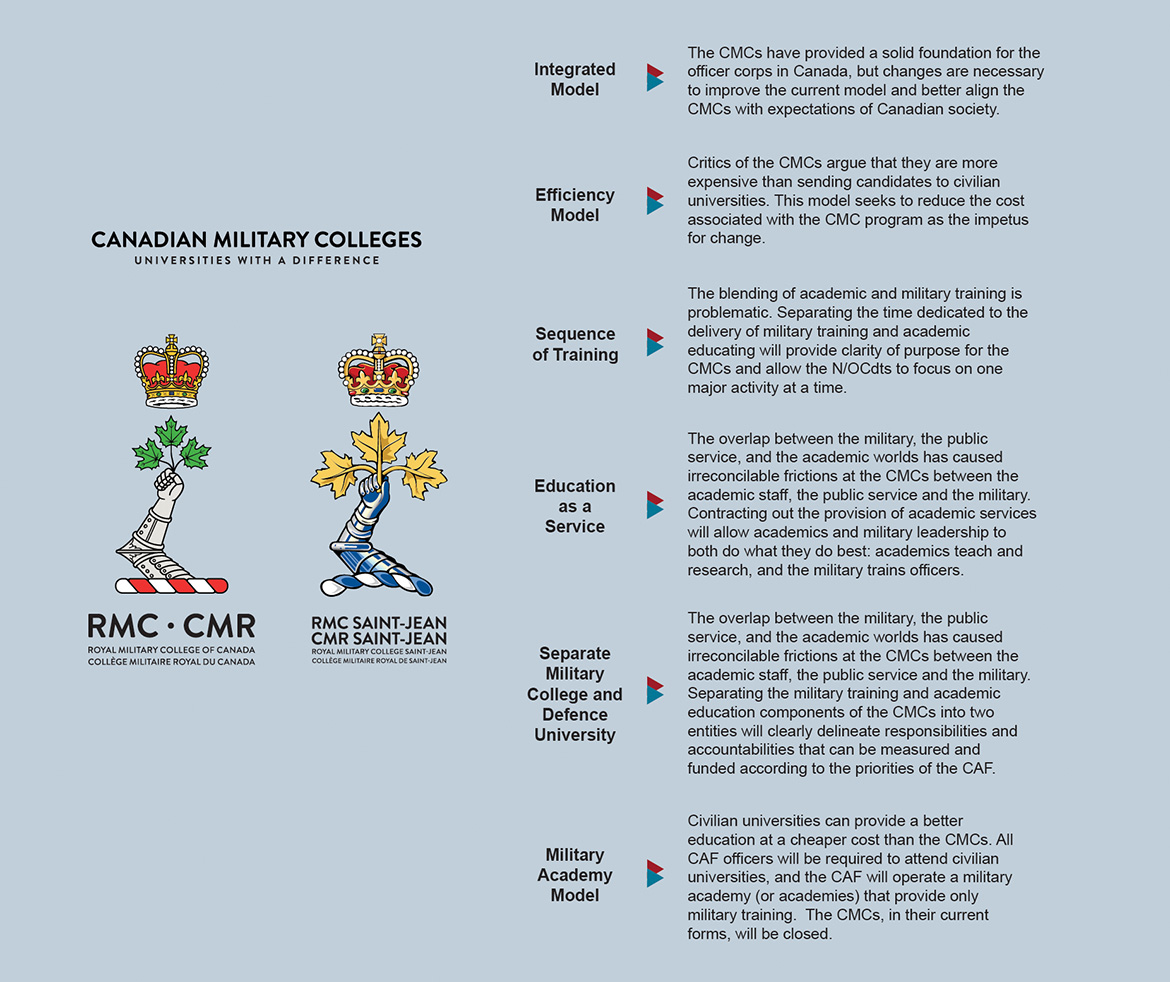

As noted above, a wide range of models exists, each with its own permutations and combinations. The Board elected to draw upon its review of foreign military academies – from NATO Allies to traditional and non-traditional partners – in order to develop six types of organizational models capable of delivering military training and education (Figure 4 and further described in Annex 3).

These vary from a model that is very similar to the present structure (the Integrated Model), to a model in which academic education is separated from the purview of the military academy and the degree-granting function of the institution is removed (the Military Academy Model).

Figure 4: Organizational Models Examined - Text version

Figure 4 contains information relevant to both Royal Military College Kingston and Royal Military College Saint-Jean:

- The Integrated Model: The Canadian Military Colleges (CMC) have provided a solid foundation for the officer corps in Canada, but changes are necessary to improve the current model and better align the CMCs with expectations of Canadian society.

- Efficiency Model: Critics of the CMCs argue that they are more expensive than sending candidates to civilian universities. This model seeks to reduce the cost associated with the CMC program as the impetus for change.

- Sequence of Training: The blending of academic and military training is problematic. Separating the time dedicated to the delivery of military training and academic education will provide clarity of purpose for the CMCs and allow the Naval and Officer Cadets (N/OCdts) to focus on one major activity at a time.

- Education as a service: The overlap between the military, the public service, and the academic worlds has caused irreconcilable frictions at the CMCs between the academic staff, the public service and the military. Contracting out the provision of academic services will allow academics and military leadership to both do what they do best: academics teach and research, and the military trains officers.

- Separate Military Colleges and Defence University: The overlap between the military, the public service, and the academic worlds has caused irreconcilable frictions at the CMCs between the academic staff, the public service and the military. Separating the military training and academic education components of the CMCs into two entities will clearly delineate responsibilities and accountabilities that can be measured and funded according to the priorities of the Canadia Armed Forces (CAF).

- Military Academy Model: Civilian universities can provide a better education at a cheaper cost than the CMCs. All CAF officers will be required to attend civilian universities, and the CAF will operate a military academy (or academies) that provide only military training. The CMCs, in their current forms, will be closed.

Each of these six models offers a feasible method for DND/CAF to deliver pre-commissioning training and education, but each comes with its own opportunities and challenges. For example, transforming the CMCs into strictly military academies and sending all applicants to civilian universities for their education would provide clarity of purpose and improve governance of the military academy. However it would also increase the amount of time required to train and educate officers, limit valuable opportunities for the kind of career-long networking that occurs at the CMCs, and reduce the second Official Language abilities of the officer corps.

Establishing a separate defence university that delivers a university education alongside a distinct military academy would facilitate greater alignment between the defence university and a civilian university model, but would be more expensive and would not resolve the challenge of dividing the N/OCdts’ time between the four Pillars of the CMCs.

Contracting out the provision of academic services to a civilian university would streamline the academic offerings and crystallize governance but would prove more costly to deliver and risk removing the close relationship that exists between the faculty and the N/OCdts.

Changing the sequence of training would offer greater distinction between activities but would trade off the opportunity to accomplish multiple objectives concurrently with no real additional benefits.

Lastly, pursuing greater cost efficiencies – though a critical aspect of the value calculation of the CMCs – is not a sufficient factor unto itself to determine the optimal design of the CMCs.

Ultimately, as detailed further below, after examining the pros and cons of each of the models, the Board determined that the Integrated Model (which most resembles the current CMC model), serves Canada best.

Costs

Canada’s post-secondary institutions vary widely, including in terms of the size of the student body, the number of campuses, the residential or commuter nature of the school, and its areas of specialization. This makes it difficult to undertake a comparative analysis of the cost of the CMCs relative to civilian universities. Moreover, the Military Colleges are unique national institutions that fulfill a different function in society than other academic bodies. It is difficult to quantify the benefits, advantages and disadvantages they yield, relative to their costs, in terms of the defence and security of Canada. The Board also accepts that there are particularities associated with running Military Colleges, and in particular running two Military Colleges, that are distinct and that further impact the cost-benefit calculus. Put another way, cost is not the exclusive comparator on which to base a determination of the value of the CMCs.

Nonetheless, a reflection on the costs of operating and maintaining Canada’s Military Colleges is necessary and worthwhile. Such an exercise reveals that the CMCs are markedly more expensive than civilian universities. Some of the factors that increase costs have a strong and justifiable rationale, others less so.

To effectively compare the costs of the CMCs to civilian universities – with costs commonly assessed by determining the operating expenses of an institution compared to the number of full-time equivalent students – the CMCRB selected eight universities that most closely resemble the CMCs in scope and scale (Figure 5).

| RMC Kingston | RMC Saint-Jean |

|---|---|

| Acadia University | Brescia University College |

| Brandon University | Canadian Mennonite University |

| Cape Breton University | Huron University College |

| St. Francis Xavier University | St. Thomas More College |

| University of Northern British Columbia | The King’s University |

| Université du Québec en Abitibi-Témiscamingue | Université Sainte-Anne |

| Université du Québec à Chicoutimi | Université Saint-Boniface |

| Université du Québec à Rimouski | Université Saint-Paul |

Annex 4 details the basis upon which the Board selected these universities for comparison and the sources upon which it drew to do so, as well as the methodology used to undertake the exercise.

Comparative Cost Observations Regarding RMC

The comparison between RMC and the selected institutions reveals that the cost per student at RMC is 1.6 times greater than the average cost per student at a civilian university. It also reveals that the student-to-faculty ratio is more than 2.5 times lower than the average ratio (Figure 6). While the current cost per student ratio is lower than previous studies, these findings are consistent with the findings of the 2017 Office of the Auditor General Report that concluded that the cost per student was higher at RMC compared to civilian universities, and that the student-to-faculty ratio was low.

| RMC | Université du Québec à Chicoutimi | St. Francis Xavier University | Université du Québec à Rimouski | Acadia University | University of Northern British Columbia | Brandon University | Cape Breton University | Université du Québec en Abitibi-Témiscamingue | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FTE | 1,951 | 6,222 | 4,738 | 4,258 | 3,745 | 2,488 | 3,145 | 3,617 | 2,691 |

| Academic | 228 | 240 | 228 | 225 | 174 | 183 | 171 | 129 | 150 |

| OE | 71,782 | 116,234 | 96,909 | 88,934 | 77,518 | 90,156 | 59,226 | 67,421 | 65,686 |

| OE/FTE | 36,792 | 18,681 | 20,454 | 20,886 | 20,699 | 36,236 | 18,832 | 18,640 | 24,410 |

| FTE/Acad. | 8.6 | 25.9 | 20.8 | 18.9 | 21.5 | 13.6 | 18.4 | 28.0 | 17.9 |

Legend:

|

|||||||||

Comparative Cost Observations Regarding RMC Saint-Jean

The comparison between RMC Saint-Jean and the selected institutions indicates that the cost per student at RMC Saint-Jean is four times greater than the average cost per student at a civilian university, and that the student-to-faculty ratio is three times lower than the average ratio (Figure 7). The 2017 Office of the Auditor General audit did not examine RMC Saint-Jean.

| RMC Saint-Jean | Université St-Paul | Université St-Boniface | Huron University College | The King’s University | Canadian Mennonite University | Université Sainte-Anne | Brescia University College | St. Thomas More College | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FTE | 318 | 916 | 756 | 1,560 | 868 | 507 | 440 | 1,239 | 1,160 |

| Academic | 40 | 66 | 42 | 45 | 48 | 32 | 29 | 35 | 29 |

| OE | 30,979 | 22,338 | 29,662 | 38,736 | 18,719 | 12,280 | 20,266 | 24,215 | 15,947 |

| OE/FTE | 97,418 | 24,386 | 39,235 | 24,831 | 21,566 | 24,221 | 46,059 | 19,544 | 13,747 |

| FTE/Acad. | 8.0 | 13.9 | 18.0 | 34.7 | 18.1 | 15.8 | 15.2 | 35.4 | 40.0 |

Legend:

|

|||||||||

In order to assess the overall value proposition of the CMCs from a financial perspective, the Board sought to contextualize the above observations in relation to four guiding principles:

- Canada’s Military Colleges are unique institutions that play a critical role in the education, training and development of junior officers.

- Such education, training and development is the backbone of the Canadian Armed Forces and requires ongoing and significant investment.

- The CMCs are not the only source of capable, talented, effective leaders for the CAF; the costs of running the CMCs must be reasonable, sensible and defensible.

- The CMCs must ensure that they have a distinct identity, a clear sense of purpose, an excellent track record and a first-rate program in order to justify any major discrepancies in costs relative to comparable civilian universities.

Viewed through this lens, while variation is to be expected, the overall scale of difference is difficult to justify; it is evident that there is a need to reduce costs at the CMCs and that certain areas are particularly ripe for reform.

Arguably the most critical cost driver for the CMCs is the low number of N/OCdts, who make up one-half (RMC) to one-third (RMC Saint-Jean) of the average size of the student body at comparable universities. Growing this number, predominantly through an increase of N/OCdts within the ROTP CMC cohort, would serve as a key lever for reducing the cost per student, while also serving to promote other CAF objectives around reconstitution (growing the trained strength of the CAF), recruitment and diversity.

The large number of faculty members relative to the student body is also a key factor in driving costs at the CMCs. While small class sizes can be very beneficial for learning outcomes and are often seen as desirable by both students and faculty members (although this remains a point of debate and the “ideal” ratio remains contested),Footnote 20 the significant discrepancy between the CMCs and comparable universities is notable and evidences a compelling need to increase the student-to-faculty ratio.

RMC Saint-Jean also shoulders costs (including internal resources and contracted resources) that are absent from comparable universities and from RMC, primarily as a consequence of offering the Collège d’enseignement général et professionnel (CÉGEP) program. The value of continuing to offer CÉGEP is highly debatable from a variety of perspectives and will be discussed in detail in a subsequent section of this Report. Additionally, the facilities maintenance and service support contract with the Corporation Fort St-Jean is a significant cost driver unique to RMC Saint-Jean, although it yields great benefit, as reflected by the quality of services and facilities at RMC Saint-Jean, and provides an excellent example of the principle that “you get what you pay for.”

Certain other cost drivers are also more understandable and defensible, particularly when they are linked to the unique nature of the CMCs as federally regulated military institutions that reflect the unique socio-political realities of our bilingual country. For example, the decision to maintain two separate, small institutions in two different provinces results in significant duplication (whereas some of the comparable universities are satellite organizations of larger universities, an arrangement that helps reduce costs). Consequently, between the CMCs there are two Commandants, two Principals, two Boards of Governors, two Registrar’s Offices and two Fitness Directors, etc. Canada is the only country among the foreign partners and allies studied to adopt this approach.

The need for federal government bodies to offer services to employees in both official languages, and to provide comparable instruction in both official languages, presents another cost factor; such a requirement is absent from the Canadian civilian university landscape, and it both increases costs and presents staffing hurdles.

The fact that N/OCdts are employees of the CAF introduces another area of difference: as part of their employment, they are provided with uniforms at public expense, including for their upkeep and maintenance. Their activities, including On-the-Job-Experience, are paid for by their employer, the CAF. These costs, over which the Military Colleges themselves have little control, are included in the cost assessment and contribute to the greater overall operating costs of the CMCs.

In sum, while there are a range of socio-political and regulatory imperatives that impact the cost of operating the CMCs, as well as particular elements of their inherent character that present additional costs as compared to comparable civilian universities, there are also key opportunities available to the Military Colleges to deliver a more cost-effective outcome in service of their overall value proposition.