Annexes

On this page

- Annex 1 – Terms of Reference

- Annex 2 – Composition of the Board

- Annex 3 – Six Types of Organizational Models

- Annex 4 – Cost Analysis

- Annex 5 – Scoring Process for the Organizational Models

- Annex 6 – Boards of Governors Comparison Charts

- Annex 7 – Proposed Integrated Officer Development Program (IODP) Framework

- Annex 8 – The Cadet Chain of Responsibility (CCOR)

- Annex 9 – Literature Reviewed

Annex 1 – Terms of Reference

Background

Reference: Report of the Independent External Comprehensive Review 20 May 2022

- On 29 April 2021, the Minister of National Defence (MND) announced the launch of an Independent External Comprehensive Review (IECR) of current policies, procedures, programs, practices, and culture within the Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) and the Department of National Defence (DND). In May 2021, DND/CAF engaged former Supreme Court Justice, The Honourable Louise Arbour, to undertake the review. The aims of this review were to: shed light on the causes for the continued presence of harassment and sexual misconduct despite efforts to eradicate it; identify barriers to reporting inappropriate behaviour; assess the adequacy of the response when reports are made; and make recommendations on preventing and eradicating harassment and sexual misconduct.

- The Report of the IECR (the “Report”) included the views and workplace experiences of current and former DND employees, CAF members, and defence contractors. The IECR team conducted a review of the recruitment, training, performance evaluation, posting, and promotion systems in the CAF, as well as the military justice system’s policies, procedures, and practices to respond to allegations of harassment and sexual misconduct. It also considered all relevant independent reviews concerning DND/CAF, along with their findings and recommendations.

- The Report was produced on 20 May 2022, and on 30 May MND welcomed the Report. In her 13 December 2022 report to Parliament, MND directed DND/CAF officials to move forward on implementing all of the 48 recommendations as described within the Report.

- The Report identified serious deficiencies and systemic issues with the experience of naval/officer cadets at the Royal Military College of Canada (RMC), in Kingston and Royal Military College Saint-Jean (RMC Saint-Jean), known collectively as the Canadian Military Colleges (CMCs), and documented persistent concerns with sexual harassment, discrimination, and misconduct. The Report concluded that the CMCs “appear as institutions from a different era, with an outdated and problematic leadership model”. In particular, the Report viewed the CMC Cadet Wing structure as antiquated and counter-productive and recommended that it should be eliminated. Further, the Report identified systemic deficiencies and harmful cultural issues at the colleges and concluded by questioning the purpose, outcomes, and methods for, and with which, the CMCs currently operate.

- These findings led to two recommendations specifically focused upon the CMCs, as follows:

- Recommendation 28. The Cadet Wing responsibility and authority command structure should be eliminated; and

- Recommendation 29. This recommendation consists of two parts, as follows:

- Part 1. A combination of Defence Team members and external experts, led by an external education specialist, should conduct a detailed review of the benefits, disadvantages, and costs, both for the CAF and more broadly (i.e. the nation), of continuing to educate Regular Officer Training Plan (ROTP); cadets at the CMCs. The review should focus on the quality of education, socialization and military training in that environment. It should also consider and assess the different models for delivering university-level and military leadership training to officer cadets, and determine whether RMC and RMC Saint-Jean should continue as undergraduate degree-granting institutions, or whether officer candidates should be required to attend civilian university undergraduate programs through the ROTP.

- Part 2. In the interim, the Chief of Professional Conduct and Culture (CPCC) should engage with RMC and RMC Saint-Jean authorities to address the long-standing culture concerns unique to the military college environment, including the continuing misogynistic and discriminatory environment and the ongoing incidence of sexual misconduct. Progress should be measured by metrics other than the number of hours of training given to cadets. The Exit Survey of graduating cadets should be adapted to capture cadets’ experiences with sexual misconduct or discrimination.

- Recommendation 28 is directly related to both parts of Recommendation 29 and, as such, has been subsumed into the work to address the latter.

Mandate

- As per Part 1 of Recommendation 29 of the Report, the conduct of a review of the CMCs will be conducted by a blended DND/CAF and external review board as directed by MND. Part 2 is being led by the Canadian Defence Academy (CDA) and supported by CPCC, Director General Military Personnel Research and Analysis (DGMPRA), and the CMCs. These terms of reference apply to Part 1 of Recommendation 29 and will address Recommendation 28 as well.

Convening Authority

- The Deputy Minister of National Defence (DM) and Chief of the Defence Staff (CDS) will jointly convene the CMCs Review Board to address Recommendation 28 and Part 1 of Recommendation 29 of the IECR; they will be hereafter referred to as the "Convening Authority".

Scope of the Board

- The Convening Authority mandates the CMCs Review Board (hereafter referred to as the “Board”):

- to review the costs, benefits, disadvantages, and advantages, both to the CAF and the nation, of continuing to educate ROTP naval/officer cadets at the CMCs;

- to assess the comparative quality of education, socialization (including inculcation of Canadian values and expectations), and military leadership training in the CMCs environments;

- to assess the potential of different models for delivering university-level education and military leadership training to naval/officer cadets;

- to recommend whether RMC and RMC Saint-Jean should continue in their current or an altered capacity as undergraduate degree-granting institutions, or whether all ROTP naval/officer cadets should instead be required to attend civilian university for their undergraduate education;

- if it is recommended that the CMCs should continue as undergraduate degree-granting institutions, the Board will examine:

- the model of early leadership development that draws upon the current Cadet Wing structure and recommend whether it should be eliminated or modified, and

- any other changes required to improve the conduct of the CMCs ROTP model, such as ensuring that ethics courses are taught by independent specialists;

- if it is recommended that all ROTP naval/officer cadets attend civilian university undergraduate programs, the Board will assess:

- the feasibility of integrating: military leadership; physical fitness and sports; and bilingualism into naval/officer cadet development by means of a modified military college model;

- how to transition to a modified military college model, ensuring the academic completion for those cadets still in the CMCs system; and

- the implications for other programs at the CMCs, such as: undergraduate education to other members of the Defence Team, and the public; graduate studies (to include those offered through the Canadian Forces College), other related programs; and defence research.

Responsibilities of the Board

- The Board will submit a final report to the Convening Authority to include specific recommendations on the following:

- the recommended model for university-level education and military leadership training to naval/officer cadets;

- whether RMC and RMC Saint-Jean should continue as undergraduate degree-granting institutions. If it is recommended that they should continue as such, the Board will make recommendations as to:

- whether the Cadet Wing structure should be eliminated or modified,

- any changes required to improve the conduct of ROTP at the CMCs, and

- any additional courses and curriculum changes that are warranted;

- whether ROTP naval/officer candidates should be required to attend university undergraduate programs solely through the ROTP Civilian University model. If this course of action is proposed, the Board will make recommendations on the feasibility of the CAF adopting a modified military college model; and

- if significant change is recommended, an outline plan for:

- the transition to a modified military college model and the completion of under-graduate education by currently enrolled cadets, and

- the delivery of other functions in support of the Defence Team currently provided by the CMCs.

- The Board will employ an evidence-based approach in executing their mandate. They will consult broadly with subject-matter experts across a range of domains, both in Canada and abroad, and with both current and former members of the Defence Team with lived experiences at the CMCs. All information received by the Board will be duly considered, and all recommendations will be based upon a documented, transparent process of analysis, derived from evidence and research. All information gathered, submitted, or considered will be appropriately catalogued and archived.

Board Composition

- As stated in the Report, Recommendation 29 Part 1 is clear in that this review will be led by an external education specialist, and that it be composed of a combination of external and Defence Team members. An effective review will require different perspectives, competencies, and qualifications. Therefore, the CMCs Review Board will be comprised of the following:

- Chairperson: an independent external-to-DND education specialist.

- Members:

- Four external civilian members; and

- Two Defence Team members, with at least one General/Flag Officer or Captain(Navy)/Colonel, and one executive level DND public service employee.

- The Board will have access to specialist advice and be supported by a team for its administrative needs.

Methodology and Approach

- The following guidance is provided to the Board:

- the Board’s recommendations will apply to both CMCs, noting and addressing circumstances unique to either RMC or RMC Saint-Jean;

- the Board will examine the conduct of naval/officer cadet education and military leadership training from a sample of allied nations for models from which best practices would be adaptable, feasible, and advisable to the Canadian context; and

- the Board’s work plan will include a review of previous studies into the operation of the CMCs including, but not limited to, the following:

- Report of the Ministerial Committee on the Canadian Military Colleges (May 1993);

- Report of the RMC Board of Governor’s Study Group – Review of the Undergraduate Programme at RMC (Withers Report, 24 September 1998);

- Special Staff Assistance Visit (SSAV) – Report on the Climate, Training Environment, Culture and ROTP Programme at the Royal Military College of Canada (10 March 2017);

- 2017 Fall Reports of the Auditor General of Canada to the Parliament of Canada, Report 6 – Royal Military College of Canada – National Defence (OAG Report 6 – RMC);

- A Qualitative Study on the Career Progression of General Officer / Flag Officers in the CAF, Defence Research and Development Canada Scientific Letter (July 2018);

- Distribution of Scientific Brief: Highlights of Studies Comparing Officers From Various Entry Plans, Director General Military Personnel Research and Analysis (23 November 2018); and

- The RMC Response to Report 6, RMC, of the 2017 Fall Reports of the Auditor General of Canada (10 July 2019).

Deliverables

- The Chairperson shall ensure the production of the following deliverables:

- Written work plan and verbal briefings to Convening Authority

- Progress Reports to the Convening Authority

- Draft Report to the Convening Authority

- Final Report to the Convening Authority

Language Requirements

- The Board shall conduct all meetings and interviews in English and/or French as required by the person being interviewed. When required, document translation, including of any deliverables, will be facilitated by the support organization.

Support to the Review Board

- DND has overall responsibility for funding and support to the Board. As a minimum, the support staff will include a Director/Chief of Staff (COS), with public affairs-/communications, legal, linguistic, intersectional analyst, and administrative (clerical, travel, etc.) support).

- The support staff will provide a liaison function between the Board and DND/CAF organizations and external expertise. The support staff will facilitate timely access to DND/CAF documents, employees/members, and, to the degree possible, external experts, stakeholders, and foreign military organizations. The support staff will also coordinate any briefings to be provided by the Defence Team to the Board and facilitate access to other relevant source material or people.

- The Board will be provided with access to relevant records under the control of the DND, or the CAF, through the support staff. All access to relevant records will be provided subject to applicable exemptions, or those ordinarily applied under the Access to Information Act and Privacy Act, with the support staff consulting with the Director of Access to Information and Privacy if required.

Confidentiality and Disclosure

- The meetings of the Board, as well as information gleaned throughout the interview and report-writing process, and the contents of the Draft Review Report and Final Review Report (until published), are confidential. In addition, the Board will conduct the review with discretion and confidentiality.

Conflict of Interest

- The actual and perceived impartiality of the Board, and the support staff, is of utmost importance in order to ensure the credibility of the report and its corresponding recommendations, and their utility for the evolution of the CMCs and, in turn, the CAF. Before empanelment, all board members will be required to disclose any real, apparent, or potential conflicts of interest. Board members will be briefed after empanelment on mitigating any apparent or potential conflicts of interest. Should an issue arise wherein a Board member has a conflict that cannot be mitigated, the Convening Authority may remove the individual from the Board.

- To reduce potential undue influence, the support staff will be geographically separated from either Kingston or Saint-Jean-sur-Richelieu.

Annex 2 – Composition of the Board

Chairperson – Dr. Kathy Hogarth

Dr. Kathy Hogarth holds a PhD in Social Work from Wilfrid Laurier University. She has more than 20 years’ experience as an adult-education specialist at York University, King’s University College, the University of Waterloo - Renison University College and Wilfrid Laurier University, specifically in the roles of professor, special advisor on anti-racism and inclusivity, and dean. Dr. Hogarth currently is an Associate Vice President, Global Strategy at Wilfrid Laurier University. She is a published book author and published in numerous academic journals in the areas of social work, psychology, anti-racism, diversity and inclusion, and has spoken widely at national and international conferences on the topics of race and race representation, decolonization, and the lived experiences of racialized peoples. She has consulted with several organizations and institutions through their organizational change management processes and has served on numerous Boards nationally and internationally.

Young Adult Socialization Expert – Dr. Chantal Beauvais

Dr. Chantal Beauvais has 20 years’ experience in university management, most recently as Rector at the University of Saint-Paul where she was responsible for implementing the strategic vision of the university, including transformative change in its day-to-day operations. As a professor of philosophy, she relaunched the faculty and department by creating new programs in philosophy and ethics. She has experience in university governance, including as past Chair of the Royal Military College Saint-Jean Board of Governors, and is involved in public sector associations and committees focused on social integration and the accessibility of higher education to marginalized people. She sits on several boards of directors, including the Gîte-Ami in Gatineau, a community organization that works with people experiencing homelessness.

Culture Evolution Expert – Mr. Michael Goldbloom

Mr. Michael Goldbloom, C.M. served as Principal and Vice-Chancellor of Bishop’s University from August 2008 to July 2023. Prior to that he was Vice-Principal Public Affairs at McGill University. He began his professional career as a labour lawyer and was subsequently President of the YMCA de Montréal. Mr. Goldboom has extensive experience in Canada’s news industry, initially as a journalist and editorial writer, and subsequently as the publisher of The Gazette in Montreal and of the Toronto Star. In 2013 he received the Order of Canada in recognition of his work in building bridges between Montreal’s English- and French-speaking communities. He is experienced in institutional leadership, strategic planning, labour relations, governance, government relations, equity, diversity and inclusion initiatives, finance and risk management. Mr. Goldbloom has served as Chair of the Board of Directors of CBC/Radio-Canada since 2018.

Executive Expert – Dr. Renée Légaré

Dr. Renée Légaré is a human resources executive with more than 25 years of experience in various industries, including healthcare, security, transportation and education. Her background is in talent development and management, behaviour and change management practices, and organizational development and design. As the Executive Vice-President and Chief Human Resources Officer at The Ottawa Hospital, Dr. Légaré built a responsive and agile human resources department responsible for 12,000 employees, and oversaw the performance and engagement of more than 15,500 staff working at more than 19 locations. Her specialty is performance management and culture change, specifically as it relates to health and safety, retention, reward and recognition, and staff morale. Dr. Légaré now serves as an Executive-in-Residence and the Director of the Master of Health Administration Program at the University of Ottawa’s Telfer School of Management.

Academic Expert – Dr. Martin Maltais

Dr. Martin Maltais holds a Doctorate in Educational Administration and Evaluation from Université Laval in Quebec City. Prior to joining the Canadian Military Colleges Review Board (CMCRB), he was a professor of financing and education policies at the Lévis campus of the Université du Québec à Rimouski (UQAR). Author of several reports and research projects, he has experience in the development of higher education, research and digital policies. Dr. Maltais was a member of the Council of Directors and served on the executive committee of UQAR. He holds other membership roles at various Canadian university governing bodies and is a visiting research fellow at international universities in Europe and the United States.

DND Public Service Executive – Ms Suneeta Millington

Ms Suneeta Millington studied Humanities at the University of Calgary before obtaining her Juris Doctor from the University of Western Ontario. She joined the Canadian Foreign Service in 2006 and was called to the Bar of the Law Society of Ontario as a Barrister and Solicitor in 2007. With expertise in international law, multilateral diplomacy, strategy development and governance, Ms Millington has held a variety of increasingly senior diplomatic, legal and policy positions in Canada and abroad, including at the United Nations in New York and Geneva (Global Affairs Canada); within the Office of the Judge Advocate General and the Canadian Special Operations Forces Command (Canadian Armed Forces); in the International Security Policy Bureau (Department of National Defence) and, most recently, within the Foreign and Defence Policy Secretariat at the Privy Council Office.

Military Representative – Brigadier-General Kyle Solomon

Brigadier-General Kyle Solomon is an Army Engineer and a registered Professional Engineer who graduated from the Royal Military College of Canada in Kingston in 1997 with a degree in Chemical and Materials Engineering. He has command experience at the Troop, Squadron, Unit and Formation levels and broad staff experience across DND/CAF. He has deployed internationally to Kosovo and Afghanistan and also holds experience in domestic operations. A graduate of the United States Army Command and General Staff College and the United States Army School of Advanced Military Studies, Brigadier-General Solomon holds a Master’s Degree in Environmental Engineering, a Master’s Degree in Military Arts and Science, and a Master of Business Administration. Prior to his secondment to the CMCRB, he was the Commandant of the Canadian Army Command and Staff College.

Annex 3 – Six Types of Organizational Models

A range of models exist to deliver the training and education necessary to generate a professional officer corps required by the CAF and the nation.

Inspired by the various models for military officer training and education offered by the partners and allies the Board studied, the CMCRB developed six representative models, each of which takes a different approach to balancing and delivering military training and academic education in terms of sequencing and organizational structure.

Ranging from an “Integrated Model,” in which academic study and military training are undertaken concurrently and delivered by the same institution, to a “Military Academy Model” wherein no academics are even offered, each of these models presents unique challenges and opportunities and offers a variety of benefits and drawbacks. To determine which was best suited to Canada, the Board scored them against ten criteria, as detailed in Annex 5.

Model 1: The Integrated Model

The Big Idea: The CMCs have provided a solid foundation for the officer corps in Canada, but changes are necessary to improve the current model and better align the CMCs with expectations of the CAF and Canadian society.

Inspiration: Belgium, Brazil, Denmark, France, Japan, Norway, Republic of Korea, Republic of South Africa and United States.

Description: Training and education are delivered via an integrated program designed around an undergraduate academic education, second language acquisition, military and leadership training, and fitness, health and wellbeing development. The program is delivered at RMC and RMC Saint-Jean, which exist as provincially accredited, federally funded institutions of higher learning that serve the Canadian Armed Forces.

Key reforms are required to the status quo in relation to identity and governance, cost and program structure, peer leadership and the Naval and Officer Cadet experience. These include renewed focus on the military identity of the CMCs, streamlined and better-defined governance structures, an increase in the number of Naval and Officer Cadets (N/OCdts), a reduction in the number of academic staff, the elimination of the CÉGEP program at RMC Saint-Jean, the restructuring of the Cadet Chain of Responsibility, greater focus on language training, a re-conceptualization of “fitness,” new approaches to addressing misconduct prevention and response, an ameliorated approach to infrastructure, operations and support, and more dedicated financial resources.

Model 2: The Integrated Efficiency Model

The Big Idea: Critics of the CMCs argue that they are more expensive than sending candidates to civilian universities. This model seeks to reduce the cost associated with the CMC program.

Inspiration: The 2017 Auditor General of Canada Report

Description: The Integrated Efficiency Model seeks to reduce the costs of training and educating officers via the ROTP CMC to a cost comparable to the ROTP Civ U stream, by reducing the number of academic programs offered and increasing the number of N/OCdts who attend the CMCs.

Activities that do not directly result in officer training and university-level education are eliminated, such as the ILOY program, the Non-Commissioned Member Executive Professional Development Programme (NEPDP), Army Technical Warrant Officer (ATWO)/Army Technical Staff Officer (ATSO), the cyber program, and Chemical, Biological, Radiological and Nuclear (CBRN) training. To ensure the adequacy of facilities, the Deputy Minister of National Defence should create a fenced financial account dedicated to infrastructure maintenance and development at the CMCs. The concept of two campuses should be re-evaluated.

Key reforms to the status quo in relation to identity and governance, cost and program structure, the Cadet Chain of Responsibility, and the cadet experience are still required, as per Model 1, with additional cost reduction items.

Model 3: The Sequence of Training Model

The Big Idea: The blending of academic and military training is problematic. Separating the time dedicated to the delivery of military training from the time allocated to academic study will provide clarity of purpose for the CMCs and allow the N/OCdts to focus on one major activity at a time.

Inspiration: Germany.

Description: Training and education are delivered by the same institution and remain focused on academic study, second language acquisition, military and leadership training, and fitness, health and wellbeing development. The program is delivered at RMC and RMC Saint-Jean, which exist as provincially accredited, federally funded institutions of higher learning. However, the military skills and leadership training, second language training, and fitness, health and wellbeing programs take place separately from the academic education, occurring at a different time entirely.

The fall and winter academic terms should focus on academics, second language training, and health and fitness activities. All military training activities take place during the summer semesters, when CAF training objectives take precedence over academics.

Additional reforms in relation to identity and governance, cost and program structure, the Cadet Chain of Responsibility, and the cadet experience are still required.

Model 4: The Education as a Service Model

The Big Idea: The overlap between the military, the public service, and the academic worlds has caused irreconcilable frictions at the CMCs between the academic staff, the public service, and the military. Contracting out the provision of academic services will allow academics and military leadership to both do what they do best: academics teach and research, and the military trains officers.

Inspiration: Australia, The Canadian Coast Guard College.

Description: Training and education are delivered by the same institution and remain focused on academic study, second language acquisition, military and leadership training, and fitness, health and wellbeing development. The military, fitness and language programs are delivered by the CMCs, and the academic program is delivered by a third party under contract. RMC and RMC Saint-Jean exist as military academies. The CAF pays only for academic programs that they determine are required for their officer corps. All academic accreditation and governance are provided via the service provider.

Key reforms to the status quo in relation to identity and governance, cost and program structure, the Cadet Chain of Responsibility, and the cadet experience are still required, as per Model 1.

Model 5: The Separate Military College and Defence University Model

The Big Idea: The overlap between the military, the public service, and the academic worlds has caused irreconcilable frictions at the CMCs between the academic staff, the public service, and the military. Separating the military training and academic education components of the CMCs into two entities will clearly delineate responsibilities and accountabilities that can be measured and funded according to the priorities of the CAF.

Inspiration: Sweden.

Description: The military, fitness, and language programs are delivered by the CMCs, and the academic program is delivered by a separate Defence University that exists as a provincially accredited, federally funded university.

To ensure the autonomy necessary for a Canadian university, the Canadian Defence University (CDU) is established as a crown corporation. As such the CDU is wholly owned by the federal government but is structured like an independent university. The CMCs are Military Academies operated by the CAF. The Commandants work with the President of the Canadian Defence University to deliver the academic degree requirements for the CAF.

Additional reforms in relation to identity and governance, cost and program structure, the Cadet Chain of Responsibility, and the cadet experience are still required.

Model 6: The Military Academy Model

The Big Idea: Civilian universities can provide a better education at a cheaper cost than the CMCs. All CAF officers will be required to attend civilian universities, and the CAF will operate a military academy (or academies) that provide only military training. The CMCs, in their current forms, will be closed.

Inspiration: United Kingdom, New Zealand.

Description: The Regular Officer Training Plan - Civilian University is expanded. All CAF officers attend a military training program that is delivered via a joint military academy for initial training (basic training currently takes place at the Canadian Forces Leadership and Recruit school) and via service academies for service-specific training. Education is received from civilian universities, either independent from the CAF (for DEOs) or via a CAF-subsidized education program. Second language training is provided to CAF members using the existing second language training and education program.

All university education programs and research activities at the CMCs are eliminated, along with associated academic and support staff positions. The CAF must determine the preferred organization and construct to deliver military training. The CAF should also establish a mechanism to accredit or provide the academic component of the Joint Command and Staff Program and National Security Program, via a contract with an existing Canadian university.

Annex 4 – Cost Analysis

The method used to identify comparable universities is the 6-dimensional Euclidean Distance Method. The dimensions in question are the total number of full-time equivalent students (FTES) and professors (3 ranks) for each of the major fields (Health, Pure and Applied Sciences, and Social Sciences and Humanities).

Information regarding these civilian universities was drawn from Statistics Canada, as well as from the following sources:

- Financial Information of Universities and Colleges produced by the Canadian Association of University Business Officers (FIUC-CAUBO);

- Postsecondary Student Information System (PSIS);

- University and College Academic Staff System (UCASS).

The following should also be noted:

- Full-time equivalent students are calculated based on the number of students according to the study program. A full-time equivalent student represents 1 FTES while a part-time student represents 1/3.5 FTES..

- Students at the Royal Military College Saint-Jean include college (CÉGEP) students.

- Professors at the Royal Military College Saint-Jean include two types of professors: University Teachers (UTs), who are similar in status to civilian university professors, and Education Specialists (EDSs) who are similar in status to college (CÉGEP) teachers. Military faculty members are also included.

It is important to recall that the Royal Military College Saint-Jean is not recognized as a college (CÉGEP)-level establishment by the Ministry of Higher Education in Quebec and does not have the power to grant a college diploma, making it difficult to compare RMC Saint-Jean costs with those of civilian universities.

The expenses at civilian university establishments included in this analysis are those paid out of the operating fund. Expenditures from other funds were excluded.

Information for the CMCs was drawn from the Defence Resources Management Information System, the Human Resource Management System and the Cost Factors Manual. CMC costs were adjusted to remove expenditures attributed to second language training, military training, and fitness activities, all of which are unique to the ROTP and are not replicated at civilian universities. Financial information for RMC Saint-Jean was further adjusted to remove costs that are attributable to the Osside Institute (which is located on its campus but is not part of the College).

Annex 5 – Scoring Process for the Organizational Models

Drawing from its respective areas of expertise, the Board identified ten factors that play a significant role in determining the health, quality, viability, credibility and relevance of the CMCs. It then used these factors as the lens through which to assess which of the six models outlined in Annex 3 would best serve Canada in the current domestic and geopolitical context, using a five-point scale that ranged from 1 (Not At All) to 3 (Moderately) to 5 (Very Much):

- Identity: Does the model support a clear identity for the CMCs as a military institution?

- Governance: Does the model promote clarity and create clear lines of responsibility, authority and accountability at the CMCs?

- Cost: Does the model promote a more efficient cost per N/OCdt?

- Culture: Does the model facilitate, support or promote the desired culture to which the CAF aspires?

- Military Training: Does the model support the development and delivery of effective military skills and leadership training to meet CAF requirements, including the development of the right character and competencies?

- Academics: Does the model support the development and delivery of an appropriate academic program that meets national standards and effectively supports officer development?

- Bilingualism: Does the model support the delivery of second language training and facilitate the N/OCdts’ ability to achieve requisite second language qualifications?

- Health, Fitness & Wellbeing: Does the model support the development and delivery of health, fitness and wellbeing programs in support of healthy lifestyles?

- Recruitment: Does the model support and promote the recruitment of officers into the CAF?

- Diversity and Inclusion: Does the model support CAF diversity and inclusion objectives?

This exercise produced a consolidated assessment (Figure 13). The Board then further reflected on whether, broadly speaking, a new model would improve the status quo, and/or introduce other consequences. Based on the results of the scoring and on this reflection process, the Board concluded that Model 1 represents the best model for Canada.

This figure reflects the scoring system used by the CMCRB to assess six models for delivering military training and education to naval and officer cadets (N/OCdts). The six models assessed were:

- Model 1: Integrated Model

- Model 2: Efficiency Model

- Model 3: Sequence of Training Model

- Model 4: Education as a Service Model

- Model 5: Separate Military Colleges and Defence University Model

- Model 6: Military Academy Model

Each model was assessed according to ten categories: Identity, Governance, Cost, Culture, Military training, Bilingualism, Health and Fitness, Academics, Recruiting, Diversity and Inclusion, with each category rated on a score of 1 to 5.

| Assessed Categories | Integrated Model | Efficiency Model | Sequence of Training Model | Education as a Service Model | Separate Military Colleges and Defence University Model | Military Academy Model |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identity | 4.0 | 3.7 | 3.4 | 4.0 | 4.0 | 4.9 |

| Governance | 3.9 | 4.0 | 3.3 | 3.9 | 3.3 | 4.9 |

| Cost | 3.4 | 3.9 | 2.3 | 1.9 | 2.3 | 3.3 |

| Culture | 4.1 | 3.4 | 2.6 | 2.9 | 3.3 | 3.9 |

| Military Training | 4.7 | 3.6 | 3.3 | 3.3 | 3.7 | 4.9 |

| Bilingualism | 4.3 | 3.6 | 3.4 | 2.3 | 2.3 | 1.1 |

| Health and Fitness | 4.6 | 3.7 | 3.4 | 2.7 | 2.6 | 3.4 |

| Academics | 4.6 | 3.9 | 3.6 | 3.9 | 3.9 | 2.7 |

| Recruiting | 4.3 | 3.6 | 3.1 | 3.4 | 3.1 | 3.6 |

| Diversity and Inclusion | 3.4 | 3.1 | 2.9 | 3.1 | 2.9 | 2.6 |

| Total | 41.2 | 36.4 | 31.4 | 31.2 | 31.4 | 35.2 |

Total scores for each model out of 50:

|

||||||

Annex 6 – Boards of Governors Comparison Charts

| Canadian Universities | Canadian Military Colleges |

|---|---|

| Boards of Governors (BoG) at civilian universities govern and manage the affairs of the University, including oversight of the governance, conduct, management and control of the University and its property, revenues, expenditures, business and related affairs. Overall, they ensure sound governance and stewardship of the University. | The role of the Boards of Governors (BoG) at the CMCs are partially similar to those of civilian universities. Even though the BoGs do not govern and manage the affairs of the CMCs, they provide strategic oversight and ensure sound governance. |

| Area of Responsibility | Canadian Universities | Canadian Military Colleges | Assessment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Governance | Promote a culture of accountability; ensure effective management; approve Board governance policies; and manage succession planning. | Bicameral system. The BoG manages its succession plan and procedures through the Governance and Nominating Committee. The Commandant provides a report to the Board at each meeting, allowing members to ask questions and exercise oversight. | Similar |

| Strategy | Ensure that a robust strategic planning process is in place; provide input, review and approve the University’s strategic plan; contribute to the development of the mission, vision and values of the university; review and approve the University’s annual operating and capital plans and budgets. | The Terms of Reference provide direction on this function (i.e. “assist in the development of the strategic direction, and review and advise on the business and long-range development plans”). Even though the BoG has not been traditionally involved in development plans, it has made recommendations on the process. A BoG member is also part of the development of the Strategic Research Plan. | Partially Similar |

| Finances | Ensure that financial results are reported fairly and with accepted accounting principles; ensure adequate resources and financial solvency; review operating performance relative to budgets and objectives. | The BoG has no fiduciary responsibilities. Funding in the CAF is under the authority of the DM, and funding allocations are managed by the chain of command (CMP/CDA). | Not Similar |

| Reporting, Monitoring & Internal Controls | Ensure that the University reports on performance against the objectives set out in its strategic and operational plans; monitor performance against the objectives; ensure appropriate internal and external audit and control systems and receive regular status updates. | The Commandant reports to the Board at each meeting on key activities. Performance objectives are seldom discussed. The BoG does not have visibility on audit or control systems. | Partially Similar |

| Risk Management | Understand the University’s key risks; ensure that there is a process to identify, monitor, and mitigate/manage risks; receive regular risk assessments and reports. | The BoG has no extant responsibilities related to risks. The Strategy Committee has recently raised an interest in cybersecurity and network risks. | Not Similar |

| Human Resources | Appoint and support the President; provide advice to the President and monitor their performance; review HR strategies and plans for appointment of senior management. | The MND is the President, and the role is executed by the Commandant. The BOG is not involved in their appointment or performance. However, the BoG Chair is part of the selection committee for the Principal. | Not Similar |

| Code of Conduct & Ethics | Approve and act as a guardian of the University’s values; promote a culture of integrity through its own actions and interactions with senior executives and external parties. | Members of the BoG are either CAF members, public servants or civilians under contracts, who all must adhere to a Code of Ethics. | Similar |

| Communications | The President is the spokesperson for the University, and the Chair of the Board is the spokesperson for the Board. The Chair will seek guidance from the Board and consult with the President to determine items to be released publicly. | The same is true of the BoG at the CMCs. For external communications, the chain of command and ADM (PA) hold the authority regarding release of public-facing communications. | Partially Similar |

| Signing Authorities | Appoint committees it considers necessary to carry out the Board’s functions, and to confer on the committees the power and authority to act for the Board; and to enter into agreements on behalf of the University. | The BoG has the authority to appoint committees and confer powers as stated in the ToR. The BoG is not authorized to enter into any agreements. | Partially Similar |

Annex 7 – Proposed Integrated Officer Development Program (IODP) Framework

| Year 1 | Spring/Summer (2 Months) | Fall (4 Months) | Winter (4 Months) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Entry Stream | July – August | September – December | January – April |

| High School Graduates going into First Year of CMC in Ontario or Quebec |

Basic Military Officer Qualification (BMOQ) 1 Course FORCE Test Initial Language Assessment + Varsity Try-Outs during last two weeks No Academic Credit |

Academic Term

Arts/Science: 4 Credits + 1 Credit LT/FHW Engineering: 5 Credits + 1 Credit LT/FHW |

Academic Term

Arts/Science: 4 Credits + 1 Credit LT/FHW Engineering: 5 Credits + 1 Credit LT/FHW |

| CÉGEP Students who have completed one year of CÉGEP and are going into First Year of CMC in Ontario or Quebec | BMOQ 1 Course FORCE Test Initial Language Assessment + Varsity Try-Outs during last two weeks No Academic Credit |

Academic Term

Arts/Science: 4 Credits + 1 Credit LT/FHW Engineering: 5 Credits + 1 Credit LT/FHW |

Academic Term

Arts/Science: 4 Credits + 1 Credit LT/FHW Engineering: 5 Credits + 1 Credit LT/FHW |

|

|||

| Year 2 | Spring/Summer (4 Months) | Fall (4 Months) | Winter (4 Months) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| May – August | September – December | January – April | ||

| All Students + N/OCdts Merge Into A Single Cohort At This Point | BMOQ 2 Course (7 Weeks) Language Intensive (3 Weeks) + Varsity Try-Outs during last two weeks Orientation (1 Week) For CÉGEP Grads beginning the CMC Program 1 Credit

|

Integrated Officer Development Program (IODP) Launch The IODP will begin with the four-week Military Skills & Leadership (MSL) - Foundations

1 Credit |

Academic Term (Compressed)

Arts/Science: 3 Credits + 1.5 Credit LT/FHW/MSL Engineering: 4 Credits + 1.5 Credit LT/FHW/MSL |

Academic Term

Arts/Science: 4 Credits + 1.5 Credit LT/FHW/MSL Engineering: 5 Credits + 1.5 Credit LT/FHW/MSL |

|

||||

| Year 3 | Spring/Summer (4 Months) | Fall (4 Months) | Winter (4 Months) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| May – August | September – December | January – April | ||

| Communications Intensive (10 Weeks) Focus on Language Acquisition (in 2nd Language Environment where possible). Followed by focus on experiential learning (including exposure to Service/Occupation Training).

1 Credit

|

Military Skills & Leadership (MSL) - Consolidation (2 Weeks) As part of the MSL – Consolidation, the last two weeks of the Spring/Summer Term are dedicated to the CCOR Intensive Leadership Preparatory Course

No Credits |

Academic Term

Arts/Science: 3 Credits + 1.5 Credit LT/FHW/MSL Engineering: 5 Credits + 1.5 Credit LT/FHW/MSL |

Academic Term

Arts/Science: 3 Credits + 1.5 Credit LT/FHW/MSL Engineering: 5 Credits + 1.5 Credit LT/FHW/MSL |

|

| Year 4 | Spring/Summer (4 Months) | Fall (4 Months) | Winter (4 Months) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| May – August | September – December | January – April | ||

| Military Culture Intensive Focus on Experiential Learning (Exposure to Services & Occupations). Followed by focus on language acquisition (in 2nd Language Environment where possible).

1 Credit

|

Academic Term

Arts/Science: 3 Credits + 1.5 Credit LT/FHW/MSL Engineering: 5 Credits + 1.5 Credit LT/FHW/MSL |

Academic Term (Compressed) (3 months with reduced course load)

Arts/Science: 3 Credits + 1.5 Credit LT/FHW/MSL Engineering: 4 Credits + 1.5 Credit LT/FHW/MSL |

Military Skills & Leadership (MSL) - Validation & Wrap-Up (4 Weeks)

1 Credit |

|

Academic Credits: 25 (Arts/Science) // 38 (Engineering) Mandatory Officership Credits: 16 // 16 Total Credits: 41 // 54 |

||||

Notes

- Language Training (LT) = 6 Hours/Week, 0.5 Credit/Term (As required until achievement of BBB)

- Military Skills & Leadership (MSL) = 3 Hours/Week, 0.5 Credit/Term

- Fitness, Health and Wellbeing (FHW) = 3 Hours/Week, 0.5 Credit/Term (Run by PSP)

- Academic Courses = Variable Hours/Week, 1 Credit/Course

Key Principles

- The academic calendars must be aligned between the two Colleges (including Academic Courses; the Integrated Officer Development Program, the Military Skills & Leadership strand, the Fitness, Health & Wellbeing strand, the Experiential Education periods; the International Exchanges; and Exams).

- All CMC N/OCdts should be given the same foundational military skills and leadership training.

- Movement between campuses during the N/OCdts time at the CMCs is encouraged and should be facilitated.

- The IODP and MSL strand is fully standardized between both Colleges.

- DND/CAF should not operate a CÉGEP.

Additional Questions/Considerations/Points

- The content, approach and expected outcomes of the Integrated Officer Development Program (IODP) must be further developed in detail, to include a detailed Overview of the MSL across all three years. The CAF Intermediate Leadership Program run by the Osside Institute provides an excellent starting point.

- The content of the current Core Curriculum three Psychology and Leadership courses should be integrated into the MSL strand. Other key elements of the current Core Curriculum should be considered for integration into the restructured IODP (i.e. regarding Values & Ethics, Judgment, Critical Thinking, etc.)

- Courses in Engineering may need to be offered during Summer Term (Years 3 & 4).

- Teaching Staff will be required during the Summer (UTs funded through SWE; Sessional Instructors funded through O&M).

- Lab hours are part of courses (i.e. they have no separate credits allocated to them).

- This Program Configuration will reduce the number of courses required of Arts/Science/SSH students from 40 to 25; it will reduce the number of courses required of Engineering students from 48 to 38. This means that on average Engineering students will take 3 courses/year more than Arts/Science students but their overall courseload is still reduced by ten courses.

Annex 8 – The Cadet Chain of Responsibility (CCOR)

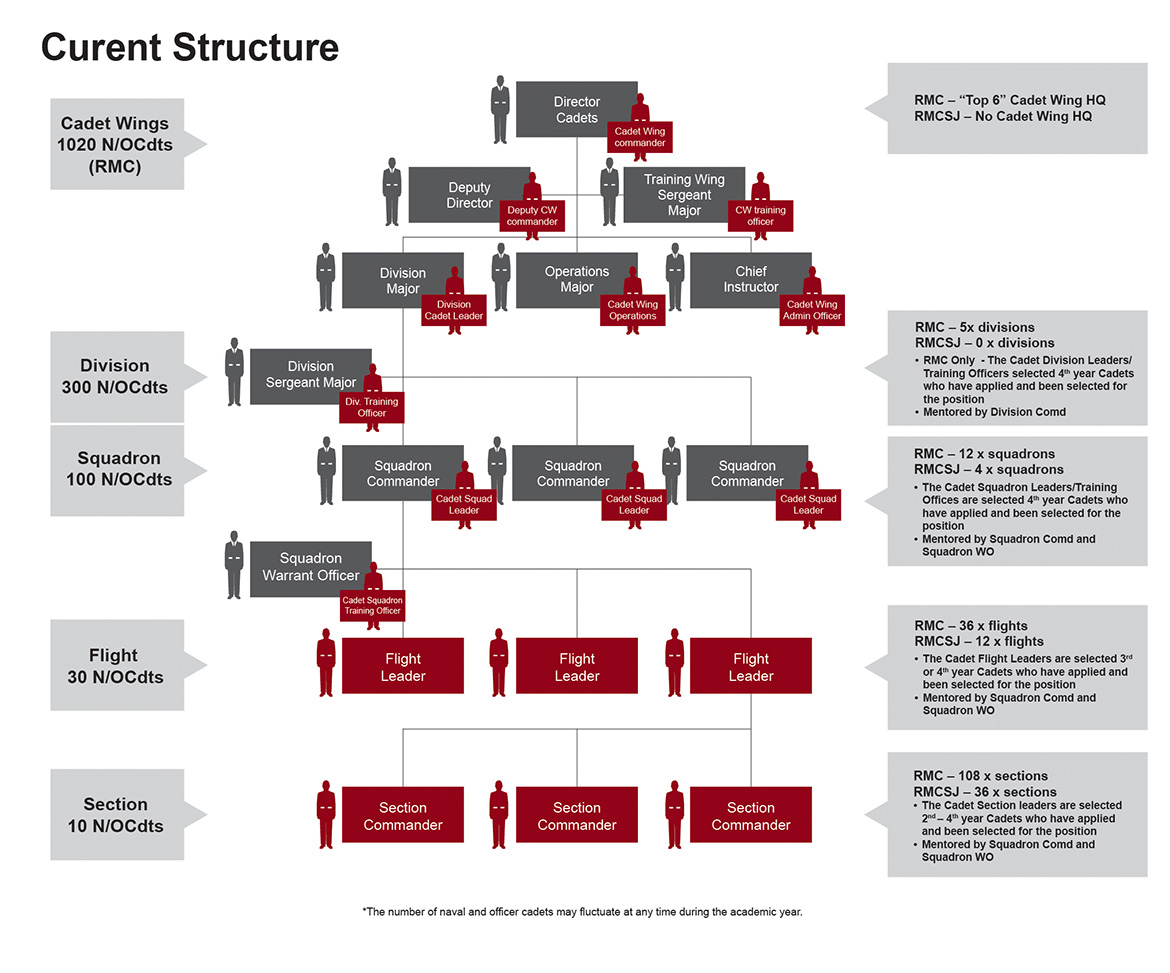

The CMCs have a Cadet hierarchy called the Cadet Chain of Responsibility (CCOR) with an organizational structure typical of military organizations, wherein upper-year Cadets have authorities and responsibilities over their peers and more junior Naval and Officer Cadets.

Figure 14: Current Structure of the Cadet Chain of Responsibility at RMC and RMC Saint-Jean - Text version

| Cadet Wing 1020 N/OCdts (RMC) |

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Division 300 N/OCdts |

|

|

| Squadron 100 N/OCdts |

|

|

| Flight 30 N/OCdts |

|

|

| Section 10 N/OCdts |

|

|

| The number of naval and officer cadets may fluctuate at any time during the academic year. | ||

Royal Military College of Canada

The CCOR comprises the Cadet Wing Headquarters and its subordinate Divisions, Squadrons, Flights and Sections. Two separate appointments to the CCOR occur each year – one each for the Fall and Winter academic terms – where N/OCdts are appointed to the Barslate. Approximately 161 out of 1,050 N/OCdts occupy a Barslate position. Other types of positions also exist related to supporting and administrative positions. In total, there are 50 types of CCOR positions and 16 types of Secondary Duty positions, the Terms of Reference for which are defined in the Cadet Wing Instructions (CADWINS). CCOR positions are classified as Junior Appointments for Third Year Cadets and Senior Appointments for Fourth Year Cadets. In addition, there are Secondary Duty positions for Second to Fourth Year Cadets, but these do not count towards completion of the RMC commissioning requirements.

Royal Military College Saint-Jean

The CCOR is slightly different at RMC Saint-Jean. RMC Saint-Jean eliminated the Cadet Wing Headquarters positions in the Fall of 2023 and it does not require a “Division level” in its organizational hierarchy due to the low number of N/OCdts who attend the College. As such, at RMC Saint-Jean, the Cadet Chain of Responsibility comprises Squadrons, Flights and Sections only. The Terms of Reference for each position are defined in the CADWINS. Cadet Wing Barslate positions are classified as Junior Appointments for Second to Third Year Cadets and Senior Appointments for Third to Fourth Year Cadets. In addition, there are Secondary Duty positions for Second to Fourth Year Cadets, but these do not count towards completion of the RMC Saint-Jean commissioning requirements.

The CCOR construct has given rise to concerns, most recently as articulated by Madame Arbour in the Independent External Comprehensive Review, but also as highlighted by the 2017 Special Staff Assistance Visit and the 2017 Office of the Auditor General’s Report.

In particular, Madame Arbour recommended that the Cadet Wing responsibility and authority command structure be eliminated, based on four systemic concerns:

- The basis of the CCOR finds its origins in the English private school system, where upper-year students are invested with responsibilities towards their juniors.

- The co-educational nature of the residences at the CMCs.

- The tension between the Duty to Report and the need for N/OCdts to fit in with their peers.

- Potential misalignment between leadership ideals taught at the CMCs and actual institutional perspectives and requirements.

Concerns and considerations regarding the CCOR have also been voiced by the N/OCdts themselves, as well as by the leaders at the CMCs. Cadets held a range of opinions and perspectives – negative and positive – regarding the structure and value of the CCOR, many of which elicited strong emotion.

Among these, the way in which the CCOR has been leveraged to facilitate the effective operation of the Colleges – given the impact of limited resources to engage more staff – was raised as an issue. Some felt that this undermined the real purpose of the CCOR, while others noted that removing the CCOR would have significant negative consequences for the CMCs due to the extent to which the Colleges rely on it to fulfill administrative and supporting functions.

The need for more interaction, coaching and mentoring from staff also surfaced as a critical missing piece in the existing CCOR leadership model; at the Section, Flight, and Squadron levels, most direct leadership is performed by Cadets who occupy positions within the CCOR, given the dearth of officers and non-commissioned members allotted to the CMC for the direct supervision and leadership of the N/OCdts.

Additionally, given the wide range of types of interactions the N/OCdts have with the CCOR, many graduates did not have any systematic exposure to specific learning objectives related to this leadership experience.

Lastly, as noted in the IECR, the power dynamic created through the CCOR – in which some N/OCdts have the ability to sanction other Cadets – was flagged by many as deeply problematic. As the CCOR contains certain disciplinary authorities, in the form of loss of privileges and corrective measures (described in CADWINS), N/OCdts in certain CCOR positions are able to impose loss of privileges and corrective measures on other Cadets. Although these must be approved by and administered under the supervision of the military chain of command (meaning that all Cadet-imposed sanctions must be authorized by the Squadron Commander, who holds the rank of Captain), this “safeguard” does little to mitigate perceived and actual abuses of power.

Notwithstanding scope for improvement, a scan of the approaches taken by partner and allied nations reveals that the appointment of students to positions of peer leadership is also a longstanding practice adopted by most service academies. Such appointments vary in nature and duration, from a single task to responsibilities that can last anywhere from 24 hours to a week to a full semester. In every case, the objective of the exercise is to provide Cadets with a greater leadership experience, enhanced stability, and sustained learning opportunities.

Annex 9 – Literature Reviewed

- Al-Homedawy, H. (2024). From findings to insights: harnessing triangulation to elevate your research: a pathway to meaningful, actionable UX research.

- Alber, A. (2007). The Training of Officers: A European Comparison (PhD Thesis).

- Antoniou, F., Alghamdi, M.H., & Kawai, K. (2024). The effect of school size and class size on school preparedness. Frontiers in Psychology.

- Armstrong, K. (2019). The stone frigate: The royal military college’s first female cadet speaks out. Toronto, ON: Dundurn Press.

- Association of Canadian Professors of Public Universities (ACPPU). (2013). Report of the Commission on Governance of the Royal Military College of Canada (PDF).

- Australian Human Rights Commission. (2013). Review into the treatment of women at the Australian Defence Force Academy: Audit report.

- Barrett, J. (2012). Education for reform: New students, new methods, new assessments. Connections: The Quarterly Journal, 11(4), 34-42.

- Barrett, J. (2018). Scholars and soldiers: Some reflections on military academe. Canadian Military Journal, 18(4).

- Barrett, J. (2023). From Rowley to Arbour: The Royal Military College through six reports. Canadian Military Journal, 23(1), 19–29.

- Beaulieu-B, P., Mitchell, P.T. (2019). Challenge-driven: Canadian Forces College’s agnostic approach to design thinking education.

- Bell, H. H., & Reigeluth, C. M. (2014). Paradigm change in military education and training. Educational Technology, 54(3), 52–57.

- Boëne, B. (2017). La formation Initiale et sa place dans le continuum de la formation des officiers de carrière. Stratégique, 3(116), 37-60. (Not available in English).

- Bradley, P.J., & Nicole, A.A.M. (2006). Predictors of military training performance for officer cadets in the Canadian Forces. Military Psychology, 18(3), 219-226.

- Bremner, N., et al. (2017) Sexual misconduct: Socialization and risk factors [literature review]. Director General Military Personnel Research and Analysis Contract Report DRDC-RDDC-2017-C302. Defence Research and Development Canada.

- Briner, E., Mercer, N. (2019). Socialization: Espoused values and the culture in practice. Summary and analysis of members in basic and entry level occupational training. Defence Research and Development Canada.

- Briner, E. (2022). Closing the gap in military socialization: Espoused values and culture in practice. Defence Research and Development Canada. DRDC-RDDC-2022-B090.

- British Ministry of Defence Crown (n.d). Army leadership. Doctrine (PDF).

- Brian L.C. (2022). The arbour report and supporting effective cultural reform in the Canadian Armed Forces.

- Brown, V. (2020). Locating Feminist Progress in Professional Military Education. Gender and the Canadian Armed Forces, 41(2), 26-41.

- Canadian Defence Academy. (2024). Fighting spirit – The profession of arms in Canada.

- Canadian Forces Recruiting Group. (n.d) Occupational Transfers in The Mil Pers Gen System.

- Castonguay, J. (1989). Le Collège Militaire Royal de Saint-Jean. Méridien. (Not available in English).

- CDA-CFLI. (2009). Duty with honour: The profession of arms in Canada (PDF).

- CDA-PCLD. (2022). CAF ethos: Trusted to serve (PDF) (accessible only on the National Defence network).

- CJCSI 1800.01 Officer professional military education Policy. (2020). Washington, Department of Defence.

- CPCC, HR-Civ. (2024). Official languages modernization – Defence Team’s way ahead.

- Davis, K., & Brian, M. (2004). “Women in the military: Facing the Warrior Framework,” in Challenge and change in the military: Gender and diversity issues. 17 Wing Publishing Office for the Canadian Forces Leadership Institute, Winnipeg, Manitoba.

- De Reviers, H. (2017). L’École de Guerre et la formation des élites militaires. Revue Défense Nationale, 798(3). (Not available in English).

- Deng, M. E., Ford, E., Nicol, A. A. M., & De France, K. (2023). Are equitable physical performance tests perceived to be fair? Understanding officer cadets’ perceptions of fitness standards. Military psychology: the official journal of the Division of Military Psychology, American Psychological Association, 35(3), 262–272.

- Department of National Defence Canada. (2001). Canadian military leadership in the 21st century (the officer in 2020): Strategic direction for the Officer Corps and the Canadian Forces officer professional development system.

- Director General Military Personnel Research and Analysis. (2021). Summary of Challenges and Barriers for Women in the CAF.

- Donatien, L., & Aleksandar, S. (2020). La formation des officiers de l’armée de terre en France, au Royaume-Uni et aux États-Unis. Approche comparative et traductologique (PDF). Onzième colloque international Les études françaises Aujourd’hui (pp. 131-147). Faculté de philologie de l’Université de Belgrade. (Not available in English, originally in Serbian only translated to French).

- Gell, H. (2021). Increase of officer cadets’ competences by internationalization. Journal of peace and war studies (p. 201). Norwich University, Archives & Collections.

- George, T. (2016). Be All You Can Be or Longing to Be: Racialized soldiers, the Canadian military experience and the Im/Possibility of belonging to the nation. University of Toronto ProQuest Dissertation Publishing.

- Goldman, C.A., Mayberry, P.W., Thompson, N., & Hubble, T. (2024). Intellectual firepower: A review of professional military education in the U.S. Department of Defense. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation.

- Government of Canada. (2009). DAOD 5002-6, Continuing education officer training plan – Regular force.

- Government of Canada. (2019). Comd CDA Initiating Directive for the Establishment of the CDS Governance Review Working Group. National Defence.

- Government of Canada. (2021). Gender representation and diversity consultation group: Summary report – Schedule O – Canadian Armed Forces (CAF)/Department of National Defence (DND) Sexual Misconduct Class Action Settlement (PDF).

- Government of Canada. (2022). Sexual misconduct incident tracking annual report. CPCC, DGPMC.

- Government of Canada. (2024). 2024 Canadian Military Colleges’ (CMCs) student experience, health and well-being survey – Topline results.

- Government of Canada. (2024). Advisory on sexual violence prevention at Canadian Military Colleges. Preliminary observations. ADM(Review Services).

- Government of Canada. (2024). Occupational transfers in the mil pers gen system.

- Government of Canada. (2024). Official languages modernization – Defence Team’s way ahead. CPCC and HR-Civ.

- Hackey, K. K., Libel, T., & Dean, W.H. (2020). Rethinking military professionalism for the changing armed forces. (Switzerland, AG: Springer).

- Hamelin, F. (2003). The soldier and the technocrat: The training of officers using the model of civilian elites. Revue Française de Science Politique, 53(3), 453-463.

- Hedlund, E. (2019). A generic pedagogic model for academically based professional officer education. Armed Forces & Society, 45(2), 333-348.

- Henri, J. (2023). Final report RMC Kingston. Solution design Sessions report – Henri investigations inc for Department of National Defence. HENRI Investigations Inc. Ottawa.

- Henri, J. (2023). Final report RMCSJ. Solution design sessions report – Henri investigations inc for Department of National Defence. HENRI Investigations Inc. Ottawa.

- Hill, A. (2015). Military innovation and culture. The US Army War College Quarterly: Parameters, 45(1), 85-98.

- Horn, B. & Bentley, B. (2015). Forced to Change: Crisis and Reform in the Canadian Armed Forces. Dundurn Press: Toronto.

- Hornstra, S., Hoogenboezem, J., Durning, S., van Mook, W. (2023). Instructional design linking military training and academic education for officer cadets: A scoping review. Journal of Military and Strategic Studies, 22(4).

- Hristov, N. (2018). Military Education as Possibility in Bulgaria. IJAEDU-International E-Journal of Advances in Education, 4(10).

- Huebner, M., Sowinski, C. (2024). Canadian Military Colleges (CMCs) graduates’ experience survey (GES) – Topline result. DROOD 3, DROOD, DGMPRA.

- James, P. (2020). Barriers to women in the Canadian Armed Forces. Canadian Military Journal, 2(0), 20-31.

- Jungblut, J., Maltais, M., Ness, E., & Rexe D. (2023). Comparative higher education politics: Policymaking in North America and Western Europe. Springer Nature.

- Kiluange, F., Rouco, C., Silva, A.P., & Fragoso da Costo Baio, L.G. (2024). Leadership training models for junior officers and captains in Europe (pp. 7162-7168). INTED2024 Proceedings, IATED.

- Kowal, H. J. (2019). The royal military college of Canada: Responding to the call for change. Security and Defence Quarterly, 24(2), 87-104.

- Krystal, H. (2017). Summary and analysis of the contract report on the role of social media in sexual misconduct. Defence Research and Development Canada.

- Kyle, F., & Shannon, R. (2017). Research summary and analysis related to the contract report on sexual misconduct and early training environments. Defence Research and Development Canada.

- Larsson, S. (2024). The military academy as a civilizing institution: A historical sociology of the academization of officer education in Sweden. Armed Forces & Society, 0(0).

- LeBlanc, M., & Pullman, L. (2018). Survey on sexual misconduct in the Canadian Armed Forces. Basic military qualification administration. Defence Research and Development Canada.

- LeBlanc, M., & Pullman, L. (2019). Survey on sexual misconduct in the Canadian Armed Forces. Basic military qualification administration. Defence Research and Development Canada.

- Lin, I., van der Werf, D., & Butler, A. (2019). Measuring and monitoring culture change: Claiming success (Director General Military Personnel Research and Analysis Contract Report DRDC-RDDC-2019-C039). Defence Research and Development Canada.

- Lick, G. (2014). The never-ending story of studying military to civilian transition. The Hill Times.

- Long, A. (2016). The Soul of Armies: Counterinsurgency Doctrine and Military Culture in the US and UK. Cornell University Press.

- MacKenzie, M. (2023). Good soldiers don’t rape: The stories we tell about military sexual violence. Cambridge University Press.

- Madison, G.R., Neasmith, D.G.,Tattersall, V.C., Bouchard, A.M.C., Dow, M.J., Gauthier, A.J., Halpin, C.A., & Thibault, C.J. (2017). Special staff assistance visit - Report on the climate, training environment, culture and ROTP programme at the Royal Military College of Canada – Kingston.

- Magnussen, L. I., Boe, O., & Torgersen, G.-E. (2023). Agon—Are military officers educated for modern society? Education Sciences, 13(5), 497.

- Maltais, M. (2021). Rapport sur le développement des activités de recherche et d’enseignement du Collège Militaire Royal de Saint-Jean comme université militaire québécoise - CMR St-Jean (Not available in English).

- Maxwell, A. (2019). Experiences of unwanted sexualized and discriminatory behaviors and sexual assault among students at Canadian Military Colleges, 2019. Statistics Canada.

- McAlpine, A. (2021). Reflecting on operation HONOUR: Race and sexual misconduct in the CAF. Centre for International and Defence Policy.

- McKay, J.R., Breede, H.C., Dizboni, A., & Jolicoeur P. (2022). Developing strategic lieutenants in the Canadian Army, Parameters, 52(1), 135-148.

- Melnikovas, A. (2019). Officer education policy development in the context of the changing European security and defence identity. Šiuolaikinės visuomenės ugdymo veiksniai, 4(1).

- Meyer, M. S., & Rinn, A. N. (2022). School‐Based leadership talent development: An examination of Junior Reserve Officers’ training corps participation and postsecondary plans. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 45(1), 4-45.

- Mitchell, P.T. (2017). Stumbling into design: Action experiments in professional military education at Canadian Forces College. Journal of Military and Strategic Studies, 17(4).

- Ministry of Defense Brazilian Army. (2024). Canadian Military College Review Board, CMCRB – Virtual Meeting.

- Mohamed, A.T.F.S. (2016). Civilian to Officer: Threshold Concepts in Military Officers’ Education. Doctoral thesis, Durham University.

- Mohamed, A.T.F.S., Nasir, A.Q., Ab Rahman, N.K., Abd Rahman, E. (2018). Military training or education for future officers at tertiary level. Zulfaqar Journal of Defence Management, Social Science & Humanities, 1(1), 45-60.

- Morris, S.A. (2001). Barriers to female officers cadets’ education at the Royal Military College of Canada. Royal Military College of Canada Master’s paper.

- Nicol, A. A. M., Charbonneau, D., & Boies, K. (2007). Right-wing authoritarianism and social dominance orientation in a Canadian military sample. Military Psychology, 19(4), 239–257.

- Niculescu, B.-O., Cosma, M., & Mandache, R. (2014). The modern officer – The leader of the military organization.

- North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). (2021). Integrating gender perspective into the NATO command structure Bi-Strategic Command Directive 040-001.

- O’Connor, G. (2006). Ministerial directives respecting the principal of the Royal Military College of Canada. Minister of Nationale Defence.

- Otis, N., Scoppio, G., Yan, Y.L., & Chiasson, C. (2021). Gender and ethnicity differences in applicants’ perceptions of the Regular Officer Training Plan (ROTP) recruitment and selection process: Phase 3 of the ROTP Study. Defence Research and Development Canada. DRDC-RDDC-2021-R013.

- Paile, S. (2008). Towards a European understanding of academic education of the military officers.

- Paile, S. (2009). L’Enseignement militaire à l’épreuve de l’européanisation adaptation de la politique de l’enseignement pour l’Ecole Royale Militaire de Belgique aux évolutions de la PESD. Thématique du Centre des Sciences Sociales de la Défense, 19(0), 61. (Not available in English).

- Paile, S. (2011). Europe for the future officers, officers for the future Europe - Compendium of the European military officers basic education. Warsaw, Poland: Department of Science and Military Education - Ministry of Defence of Poland.

- Parenteau, D. (2021). Teaching professional use of critical thinking to officer-cadets: Reflection on the intellectual training of young officers at military academies. Army University Press.

- Parenteau, D., & Maisonneuve, M. (2022). Time to reset the Canadian Military Colleges as military academies. CDA Institute.

- Parenteau, D. (2022). Officers must play key role in transforming organizational culture (PDF). Canadian Military Journal, 22(2), 27-33.

- Perron, S. (2017). Out standing in the field: A memoir by Canada’s first female infantry officer. Toronto, ON: Cormorant Books Inc.

- Office of the Auditor General of Canada. (2017). Report 6, Royal Military College of Canada—National Defence.

- Official Web Page of the United States Military Academy at West Point.

- Preston, R. A. (1991). To Serve Canada: A History of the Royal Military College of Canada. University of Ottawa Press.

- Pugliese, D. (2024). Defence leaders violating law by withholding documents are ‘reprehensible’ retired major general says. (It’s) hard to believe my case was not politicized if records can be unreasonably delayed this long or are denied release because the case was the subject of discussions amongst cabinet. Ottawa Citizen.

- Pulsifer, C. (n.d). The Royal Military College of Canada: 1876 to the present. Dispatches: Backgrounders in Canadian Military History. Canadian War Museum.

- Randall, W. (2010). Military education in Canada and the Officer Development Board March 1969, dans Wakelam et Coombs.

- Razack, S. H. (2004). Dark Threats and White Knights: The Somalia Affair, Peacekeeping, and the New Imperialism. University of Toronto Press.

- RMCSJ. (2024). Canadian Military College core curriculum. Course calendar - Core curriculum - Royal Military College Saint-Jean (RMC Saint-Jean).

- Rostek, M. (2023). Socialization, norms and organizational culture change (Toronto Research Centre Scientific Letter DRDC-RDDC-2023-L169). Defence Research and Development Canada.

- Rubenfeld, S., Denomme, W., LeBlanc, M., & Messervey, D. (2022). Results of the respect in the Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) training assessment. Director General Military Personnel Research and Analysis.

- Rubenfeld, S., & Russell, S. (2021). Sexual misconduct in the Canadian Armed Forces. Senior non-commissioned members’ perspectives. Defence Research and Development Canada.

- Rubenfeld, S., & Sobocko, K. (2022). Training and education for professional military conduct. Review of novel or evidence-based Programs. Defence Research and Development Canada.

- Russell, S., & Rubenfeld, S. (2019). Bystander behavior. Individual, organizational and social factors influencing bystander intervention of sexual misconduct. Defence Research and Development Canada.

- Schaefer, H. S., Callina, K.S., Powers, J., Kobylski, G., Ryan, D., & Lerner, R.M. (2021). Examining diversity in developmental trajectories of cadets’ performance and character at the United States Military Academy. Journal of Character Education, 17(1), 59-80.

- Scoppio, G., Otis, N., Yan, Y. (Lizzie), & Hogenkamp, S. (2022). Experiences of officer cadets in Canadian Military Colleges and civilian universities: A gender perspective. Armed Forces & Society, 48(1), 49-69.

- Scoppio, G., & Otis, N. (2019). Gender and ethnicity perspectives of officer cadets’ Recruitment Process and College Experience: Phase 2 of the Regular Officer Training Plan (ROTP) Study. Defence Research and Development Canada. DRDC-RDDC-2019-R091.

- Serre, L., & Michelle, S. (2018). Attrition Patterns on Women in the Canadian Armed Forces. Res Militaris, 8(2), 16.

- Shinn, M. (2024). Air Forces Academy phased out sexual assault prevention program shown to work at other schools. The Denver Gazette.

- Silins, S. (2023). Experiences of Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) members affected by sexual misconduct. An examination of workplace support. Defence Research and Development Canada.

- Silins, S., & LeBlanc, M. (2020). Experiences of CAF members affected by sexual misconduct: Perceptions of support. Defence Research and Development Canada.

- Smirnov, S. (2021). Analysis of Professional Training of Future Reserve Officers in the System of Modern Military Education (PDF). Science and Education a New Dimension, [S. l.], 7(199), 49-52.

- Snider, D.M. (2010). Développer un corps de professionnels. Dans Jean A. Nagl et Brian M. Burton (eds.), Garder l’avantage: revitaliser Corps des officiers militaires américains. Centre pour un nouvel américain Sécurité, (p. 22). (Not available in English).

- Stirling, P., Musolino, E., Eren, E (2020). Ensuring effective military socialization: A literature review (Director General Military Personnel Research and Analysis Contract Report DRDC-RDDC-2020-C163). Defence Research and Development Canada.

- Taber, N. (2018). After deschamps: Men, masculinities, and the Canadian Armed Forces. Journal of Military, Veteran and Family Health, 4(1), 100-107.

- Tait, V. (2020). Regendering the Canadian Armed Forces. Atlantis Journal, 41(2) 8-25.

- The British Army. (nd). The army leadership code an introductory guide (PDF).

- The International Association of Military Academies (IAMA)/L’Association internationale des académies militaires (AIAM).

- The Royal Military College Sandhurst. (2022). SO 104 RMAS Group & Sandhurst Station Alcohol Action.

- Thompson, K. (2019). Girls need not apply: Field Notes from the forces.

- United States Naval Academy. (2022) Blue and gold book.

- van Tol, J., & van Creveld, M. (1991). Training of officers: From military professionalism to irrelevance. Naval War College Review, 44(4), Article 16.

- Waruszynski, B., MacEachern, K.H., Raby, S., & Ouellet, E. (2019). Women serving in the Canadian Armed Forces: Strengthening military capabilities and operational effectiveness. Canadian Military Journal, 19(2), 24-33.

- Wilson, D.L. (2022). Duty to care: An exploration of compassionate leadership (PDF). Master of Defence Studies Paper. Canadian Forces College.

- Withers’ Study Group. (1998). Report of the RMC board of governors. Balanced excellence leading Canada’s Armed Forces in the new millenium.

- Wood, V.M., & Cherif, L. (2022). Resilience-based curriculum for Canadian Military Colleges: An environmental scan and literature review. Journal of Military, Veteran and Family Health, 8(1).

- Wright, J. (n.d.). Military identity development and informal social norms: Socialization experiences of first-year officer cadets at the Royal Military College of Canada.

- Young’s 1997 Report to the Prime Minister on the Leadership and Management of the Canadian Forces.