Findings, Analysis and Recommendations

On this page

- Organizational Structure

- Systemic Reform

As discussed above, the Board believes that the Canadian Military Colleges (CMCs) have value

- in relation to other entry streams;

- as compared to civilian universities; and

- relative to foreign military academies.

This conclusion is separate, however, from the question of the inherent value – real and perceived – of Military Colleges to Canadians. Historically, the role the CMCs have played in the defence and security of Canada, and in the country’s journey towards sovereignty, territorial integrity, economic security and social stability, have rendered this obvious.

However, in recent decades, a recognition that the Military Colleges have at times been the venue for exclusion and harm, and that there has been a hidden cost to aspects of the traditional ways of operating them, has diminished their worth in the eyes of many Canadians. Coupled with negative public attention and a sense of post–Peace Dividend complacency, some have even come to question why the country needs to invest in professional military education and training in the first place, or whether the Military Colleges are the best venues for it its delivery.

Putting aside comparative value, the Board therefore also focused extensive efforts on examining the current utility of the Military Colleges as institutions unto themselves, by undertaking a discrete analysis of seven thematic areas. Through this process, the Board identified a series of key levers where pressure can and should be exerted in order to result in the changes required to ensure that Canada’s Military Colleges deliver exceptional value for Canada and the Canadian Armed Forces (CAF).

Organizational Structure

Function

In the context of Madame Arbour’s findings in the Independent External Comprehensive Review and the mandate given to the Canadian Military Colleges Review Board (CMCRB), the first issue before the Board, as discussed at the outset, is whether, in their current state, the CMCs are so out of step with society and so broken that they are irredeemable, and therefore require major structural change or even closure. Or whether, despite any shortcomings that may endure, the CMCs as currently structured remain “the best way to form and educate tomorrow’s military leaders.”

The Board believes the latter: Canada’s Military Colleges remain an important vehicle through which to develop this nation’s leaders of tomorrow. As will be discussed in more detail below, the evidence shows that while misconduct in all its forms continues to occur at the Military Colleges, the CMCs are largely the place where, not the reason why, it happens. Moreover, to the extent that issues of misconduct arise, they are not disproportionate to the incidence rate elsewhere in Canadian society, particularly at similarly sized residential civilian universities with a similar-age peer group.

Furthermore, the CMCs are, at their core, functioning organizations that generate well-educated, well-trained, bilingual and physically fit officers for the CAF and for Canada. Removing their degree-granting function and outsourcing the formative education of Naval and Officer Cadets (N/OCdts) to civilian universities would amount to dissolving organizations that play an important strategic and social function in Canada which cannot be fulfilled by any other institution, and that serve as an important complement to the Direct Entry Officer Plan and the Regular Officer Training Plan - Civilian University entry streams.

This does not mean that the CMCs are as effective, relevant, healthy or fit-for-purpose as the nation requires them to be. Major elements of the program, culture, and physical and psychosocial infrastructure at the CMCs are problematic and, among other outcomes, permit or foster negative, inappropriate or unacceptable behaviour. These issues must continue to be addressed. The Board is encouraged by the fact that both Military Colleges have proven themselves willing, able and determined to do so.

For example, demonstrable efforts to positively evolve the culture of the CMCs – such as the establishment of a “Chair, Cultural Evolution” position at Royal Military College in Kingston, Ontario (RMC) and the establishment of a “Specialist in Resources and Training on Sexual Violence and Promoting a Positive Culture” at Royal Military College in Saint-Jean-sur-Richelieu, Québec (RMC Saint-Jean) – have prompted observable change at the CMCs, in keeping with global best practice, impacting everything from policies and procedures to management practices. Key initiatives have been developed, are taking root and are being tracked, from the creation of the Athena Network supporting women and the Agora LGBTQ2+ support group to the establishment of the Indigenous Knowledge and Learning Group. These need to be given a chance to yield greater dividends.

Overall, given their comprehensive influence as places of work, study and personal life, the CMCs have an outsized ability to shape N/OCdts. This presents challenges, but also huge opportunities. The CMCs offer an effective instrument to bring meaningful change to the CAF, through the training and education of a new generation of officers who will be exemplars of the Profession of Arms as they move into leadership positions within the institution. Thus, to the extent that the CAF is committed to making positive change, this change can find its origins in the Military Colleges.

However, this also means that the CAF and the CMCs have an even greater responsibility towards these vulnerable and impressionable young adults, particularly because as representatives of the CAF, expectations of N/OCdts are high regarding reputation and conduct, and scrutiny is intense. The Board is persuaded that the CMCs can rise to this occasion, but a genuine commitment is required from the Government of Canada and the leadership of the Department of National Defence and the Canadian Armed Forces to support them in this work.

Dismantling the CMCs at this stage and dispersing the N/OCdts to civilian universities would not solve the challenges identified above. Rather, this would simply shift them to other institutions that are perhaps less equipped to help foster the character, behaviour and attitudes needed to advance positive culture evolution in the CAF.

It should also be noted that due to their design, their funding model and their academic human resource considerations, removing the undergraduate degree programs from the CMCs would effectively cause the collapse of the graduate and research programs. Ultimately, the CMCs would thus cease to be institutes of higher learning. The impact of this – while outside of the scope of this Board’s focus – should not be underestimated. In complementarity with the work of Defence Research and Development Canada, the CMCs play a critical role in producing timely and relevant defence and security research that is highly valued, both by the Department of National Defence (DND)/CAF and by international partners and NATO Allies. A loss of this capacity would have serious negative practical and reputational consequences for Canada, and pose challenges to the country’s ability to meet its defence and security objectives.

Form

Once it had determined that the CMCs should retain their degree-granting function, the Board identified ten factors that play a significant role in ensuring the health, quality, viability, credibility and relevance of the institutions:

- Identity;

- Governance;

- Cost;

- Culture;

- Military Training;

- Academic Education;

- Bilingualism;

- Health, Fitness & Wellbeing;

- Recruitment; and

- Diversity & Inclusion.

It then assessed the six organizational models discussed above (and detailed in Annex 3) against each of these factors, using a question-based five-point scale. It further considered whether a new model would improve the status quo and/or introduce other consequences.

Through this process (detailed further in Annex 5), the Board determined that the Integrated Model, which most closely aligns with the current structure of the CMCs, remains the right fit for Canada in the current domestic and geopolitical context. Under this model, the form of the Canadian Military Colleges should appear very similar going forward to what it has looked like in past decades, particularly at RMC. Specifically:

- Both Colleges should continue to offer military training alongside an accredited academic education, through which N/OCdts earn a degree.

- No new body or mechanism should be created to deliver the academic elements of the program (be it an external service provider or a new DND/CAF-run academic Defence & Security university).

- Responsible fiscal management should guide program delivery, but cost-cutting and efficiencies should not be the primary drivers for change.

In sum, while meaningful reform is needed in how the program is governed and delivered (as discussed below), the function and form of the CMCs will not appear significantly different.

Recommendation 1

Maintain the Canadian Military Colleges as undergraduate degree-granting institutions. Continue to train and educate Naval and Officer Cadets at the Canadian Military Colleges through an Integrated Model.

Systemic Reform

The Board’s recommendation to maintain the CMCs as undergraduate degree-granting institutions via an Integrated Model is premised on the assumption that retaining the existing organizational structure is accompanied by substantive change in several areas. The Board has focused on a systems-centric approach to understanding and solving the existing issues, and the systemic reforms that are proposed aim to address the underlying problems that have plagued the Military Colleges, not simply treat the symptoms.

The findings, analysis and recommendations laid out herein are designed to identify the problematic issues, articulate why they are of concern, and propose the action needed to address them.

Collectively, these reforms should yield impactful, sustainable and positive change for the CMCs, helping to crystallize their value proposition, sharpen their clarity of purpose, reinforce their culture evolution efforts and shield them from the need for constant cycles of scrutiny.

Identity

The foundational issue undermining the CMCs at this juncture is the absence of a clear identity. The ramifications of this uncertainty – stemming from a contested understanding of their purpose – are numerous, and are the source of many of the attendant challenges facing the Military Colleges.

To some, the CMCs are military units defined by their mandate to develop N/OCdts as leaders in the Profession of Arms who are preparing for careers in warfighting and conflict management. They want to “put the M(ilitary) back into RMC” and speak of the overemphasis on academic coursework as a distraction from time that could be spent honing the military skills, gaining the practical knowledge and developing the physical fitness needed to produce excellent officers.

To others, the CMCs are first and foremost institutions of higher learning whose primary purpose is to educate university students who may ultimately serve as officers in the Canadian Armed Forces. Demands regarding drill and deportment are seen as a nuisance, and time spent playing sports, undertaking adventure training or learning about risk management is not viewed as relevant to developing the critical thinking abilities, judgment or cognitive function needed to produce smart and thoughtful citizens.

Most, however, hold a more nuanced view that adapts elements of both extremes to see the Military Colleges as places that should be responsible for all of the above, with a mandate to develop N/OCdts as both leaders and scholars – as currently reflected by the 4-Pillar model. In principle, this seems wise. In practice, it is failing.

Over time, to support this balance, three distinct, sometimes contradictory, institutional identities have emerged. Specifically, the CMCs have simultaneously become military units, federal public service institutions, and provincially chartered universities. Each identity carries its own culture and values, which do not necessarily align with one another, and each has its own stakeholders with distinct interests, divergent expectations and differing objectives. This recipe gives rise to chronic problems and ongoing tensions.

For example, for prospective N/OCdts who are leaving secondary school and seeking to join the CAF as officers, attending the CMCs provides a subsidized pathway to a university education. But it also requires commitment to joining the military and becoming part of the Profession of Arms, and as members of the CAF they are subject to terms and requirements of employment even while studying that are not applicable to students at civilian universities. It is therefore troublesome that many N/OCdts are unclear about whether they are attending a military academy where they can expect to learn leadership and military skills or whether they are post-secondary students who can expect an undergraduate education identical to that being delivered at a civilian institution. This uncertainty has longer-term ramifications, as the expectations of N/OCdts while they attend the CMCs have a critical impact on their recruiting, retention and satisfaction as CAF members.Footnote 21

Meanwhile, academic faculty are full-time, indeterminate public servants, whose terms of employment are governed by the policies of the Treasury Board of Canada, but they have also come to expect employment conditions and authorities that are aligned with civilian academic institutions. This creates significant friction, particularly in relation to the issue of institutional autonomy, which is the capacity of the institution to administer its own affairs, including its academic programming and the deployment of its financial resources, without external interference. Institutional autonomy is a fundamental characteristic of civilian universities in Canada, and the academic faculty and staff at the CMCs therefore expect the same.Footnote 22 However, unlike civilian universities, the CMCs are federal institutions and have been established as military units empowered to grant degrees. They are inherently and purposefully not autonomous from the CAF or the Government of Canada, and therefore the entire concept of institutional autonomy is inapplicable by design.

Unlike institutional autonomy, academic freedom – as defined in sources such as provincial legislationFootnote 23 and international guidelinesFootnote 24 – is a fundamental characteristic of both civilian universities and the Canadian Military Colleges. However, over the years the concept of academic freedom has been invoked to advocate for decision-making independence for academics at the CMCs in a way that has created ongoing tensions within the institutions, particularly given that the military leadership has struggled to understand its own scope of authority or to effectively exercise its management rights.

In the context of the CMCs, wherein the role of an academic education is to serve the Canadian Armed Forces, it is squarely within the purview of DND/CAF to determine what degrees and programs should be offered and how to allocate financial and human resources accordingly. Doing so is neither an infringement on academic freedom nor inconsistent with the nature of the CMCs and the degree of autonomy they enjoy.Footnote 25

Moreover, some members of the Academic Wing – comprising the faculty and staff who deliver the academic program – have struggled to understand that academics are intended to form but one part of the N/OCdts’ experience at the CMCs and have steadily placed increasing and unrealistic demands on their time. This combination of factors leads to persistent strain between many of the faculty members and management, as well as between the civilian and military sides of the institution, which negatively pervades the environment at the CMCs and consumes significant energy and attention.

For its part, the military often appears uncomfortable working alongside its public service colleagues, issuing directives in lieu of engaging in dialogue and taking unhelpfully rigid approaches to uncontroversial issues. Moreover, the CAF has paid little attention to the CMCs in past decades, with the Army, Navy and Air Force having largely abdicated any active role in the evolution or development of the Military Colleges in a sustained or systematic way. This has sent mixed messages to the academic faculty, who have been given limited guidance and guardrails in terms of vision, direction and boundaries, but who feel reprimanded when they are seen to stray off course.

As a result of each group developing differing diagnoses and devising differing solutions to what they think the problems are, the CMCs have become mired in convoluted governance structures, unclear authorities and ballooning programs, many of which deliver costly yet ineffective outcomes at the expense of the N/OCdts and the CAF more broadly. Ultimately, there is no sense of shared vision regarding the fundamental role and purpose of the Military Colleges.

So what are they? The Board believes that the CMCs are first and foremost military institutions, whose raison d’être is to develop exceptional leaders for the Canadian Armed Forces. Their programs must be laser-focused and resolutely committed to being relevant and responsive to the needs and demands of the CAF. DND/CAF senior leaders must be prepared to align allocated fiscal and human resources in support of this renewed focus.

A critical element of this officer development process is the acquisition of a rich and reputable academic education, the quality and credibility of which should continue to be reflected by earning a nationally recognized, provincially regulated undergraduate degree. But despite their use of the tagline, the CMCs are not “Universities with a Difference” or even “Universities that make a difference.” They are military academies.

To this end, more weight, attention and resources must be given to the other elements that also make up an integral part of the N/OCdt’s journey at these institutions. This includes language training, military skills, leadership development, and overall fitness, health and wellbeing, as will be discussed in greater detail in subsequent sections of this Report.

Canada has more than a hundred universities, none of which can fully respond to the specific needs associated with the mission and mandate of the CAF. What Canada does not need from the CMCs is for them to be civilian university equivalents that simply add fitness, language and military training requirements into packed academic schedules that have little specific nexus to the CAF.

What Canada does need – even more so in the highly contested, adversarial geopolitical space in which this country now operates – and what only the CAF can provide, are world-class institutions focused on defence and security, underpinned by the values, ethics and judgment that are fostered by exposure to the liberal arts, and dedicated to educating and training leaders in the Profession of Arms. It has only two of these, and they must be leveraged to their maximum potential.

Increasing the number of graduates is one way of doing so. In addition to reasons of costs and academic efficiency, enlarging the N/OCdt Corps will help create a critical mass of individuals every year who are going through dedicated foundational military education and training, with a specific focus on the defence and security needs of the country.

Another important avenue for maximizing the impact of the CMCs is to raise their profile and stature within the national psyche and around the world. Too few Canadians know about the Military Colleges, and many of those who do are aware of them solely through the lens of critical reports and media coverage. Globally, Canada’s Military Colleges are well respected, but they do not have a distinct brand that elevates them to the echelons of certain other institutions. The CMCs should be a source of pride for Canadians, and should be better leveraged as a source of national power for the country.

While this must start with appropriately resourcing their programs, increasing investment in their infrastructure and ensuring ongoing support for their operations and maintenance - none of which are easy to justify absent a strong value proposition - it must also be accompanied by a major overhaul in the branding and marketing of the Colleges. At present, recruitment efforts are lacklustre and untargeted, and completely misaligned with the calendars of civilian universities, meaning that N/OCdts often receive admission offers from civilian universities long before they hear from the CMCs, which disincentivizes many from choosing the Colleges in the first place. The CMC websites are disorganized, hard to navigate and distinct from one another in structure, content and look-and-feel, rendering them ineffective as communications and public affairs tools. And promotional materials have lost focus on the military identity and specific value proposition of the Colleges, negatively impacting their ability to inspire, excite and draw in a new generation of talent who could be motivated to join the CAF.

“Branding and marketing” has a concrete impact on the quantity and quality of applicants, the credibility of the institutions and the ability of the CAF and the CMCs to demonstrate to Canadians what they do and why it matters. It is critical for all Canadians to see themselves reflected in the composition of the CAF and to see a role for themselves within the CMCs.

Some key changes are therefore needed: new elements of a recruitment strategy should be developed and implemented by the CAF to more effectively compete for talent across the country, including by taking into account the dates at which civilian universities make acceptance offers; exemptions are needed from Government of Canada standards to build more user-friendly, harmonized and organized Military College websites, which serve as the main point of entry into the CMCs for potential applicants and interested Canadians; more tailored outreach is needed to connect with young people and their families who might not otherwise be familiar with the CMCs and what they offer; and new promotional materials must be developed that better reflect the identity, programs and value proposition of the CMCs.

Alongside these changes, elevating the stature of the Canadian Military Colleges also requires that RMC Saint-Jean’s standing vis-à-vis RMC be equalized. While both CMCs are part of a proud military tradition in Canada and are seen as distinct yet complementary counterparts, differences in size, budget, history and leadership rank have effectively relegated RMC Saint-Jean to the role of “younger sibling,” with less clout and a lower national profile than RMC. Standardizing the nomenclature used to refer to the Colleges will be an important way to reflect RMC Saint-Jean’s equal status. Currently, the Colleges are formally known as the Royal Military College of Canada (RMC) in Kingston, Ontario, and the Royal Military College Saint-Jean (RMC Saint-Jean). Colloquially, the College in Kingston is known as the Royal Military College or RMC, whereas the College in Saint-Jean is known simply as Saint-Jean or CMR Saint-Jean. In both instances, this terminology perpetuates the idea that the College in Kingston is the central military academy in Canada, and that the college in Saint-Jean is merely an add-on to the main institution.

The Board therefore considered whether to rename the institutions entirely, in order to equalize the two Colleges, better reflect the role and purpose of the CMCs, and bring them in line with the names of comparable institutions around the world. It contemplated dropping the words “College,” given the university-level education the CMCs provide, and “Royal” from the names, given a desire to modernize and nationalize the institutions. Ultimately, the Board rejected such changes as unwarranted, unnecessarily polarizing, and potentially confusing.

Instead, to help underscore the fact that Canada has two unique military colleges of which the country should be proud, in two distinct locations, with historical linkages to each of our Official Language communities, the Board believes that the names of the CMCs should be modified as follows:

- Royal Military College of Canada, Kingston (RMC Kingston)

- Collège militaire royal du Canada, Kingston (CMR Kingston)

and

- Royal Military College of Canada, Saint-Jean-sur-Richelieu (RMC Saint-Jean)

- Collège militaire royal du Canada, Saint-Jean-sur-Richelieu (CMR Saint-Jean)

The Board also considered whether to propose upgrading the rank of the Commandant at RMC Saint-Jean to Brigadier-General in order to help increase the profile of RMC Saint-Jean within the CAF and within Canada, to better project its value to Canadians, and to establish greater equality between RMC Saint-Jean and RMC. The Board believes this could be appropriate, when certain conditions are met, as discussed further below.

An increase in the number of degrees offered at RMC Saint-Jean from one to three, as also proposed and discussed below, would further serve to elevate the stature of the College.

Overall, the shift in mindset and approach that is needed to reaffirm the primary identity and value-add of the CMCs as military institutions will require greater assertiveness on the part of the military leadership at the Colleges and full support from the academic leadership. It will also require acknowledgement by the academic faculty and staff that academics – while of high calibre – exist in service of the military’s needs, not independently from them. Lastly, it will require much greater attention to, engagement with and investment in the CMCs on the part of the Canadian Armed Forces, which has long abdicated responsibility in this space.

Recommendation 2

Revise governance structures, authorities, activities, programs and training to reflect the fact that the Canadian Military Colleges are first and foremost military institutions responsible for training and educating officers as members of the Profession of Arms.

Recommendation 3

Amend the Ministerial Organizational Orders to change the name of the Royal Military College of Canada to “Royal Military College of Canada, Kingston” (RMC Kingston) and the name of the Royal Military College Saint-Jean (RMC Saint-Jean) to “Royal Military College of Canada, Saint-Jean-sur-Richelieu” (RMC Saint-Jean).

Recommendation 4

Update all branding and marketing materials and all public affairs and communications products to align with the changes proposed in this Report and to support a revised recruitment strategy.

Governance

The mission of the CMCs is to provide N/OCdts and officers with the education and training they need for a career in the Canadian Armed Forces. Under the National Defence Act, the CMCs are governed and administered in the manner prescribed by the Minister of National Defence, who has established the institutions via Ministerial Organization OrdersFootnote 26 as units of the Canadian Armed Forces and assigned them to the Canadian Defence Academy (CDA). The Minister has also determined that Canada’s Military Colleges should have the status of universities.Footnote 27

As higher education in Canada is a matter of exclusive provincial jurisdiction, Ontario and Quebec were required to enact legislation establishing both RMC and RMC Saint-Jean as universities. The Royal Military College of Canada Degrees Act was passed in 1959 by the Province of Ontario, and the Collège militaire royal de Saint-Jean Act was passed in 1985 by the Province of Quebec. RMC Saint-Jean lost its status when it was closed in 1995, but regained it, along with the right to grant degrees, in 2021. Despite running a CÉGEP program, RMC Saint-Jean does not have authority to grant CÉGEP diplomas, and it has entered into a contract with CÉGEP Saint-Jean-sur-RichelieuFootnote 28 to award the diplôme d’études collégiales.

These Constitutional realities have had far-reaching, often negative impacts on the CMCs. In particular, the way in which governance models have been set up at the Colleges – to grapple with the fact that the CMCs are federally run military institutions into which provincially regulated elements are embedded – is leading to significant, systemic, widespread and chronic problems, as well as undermining the clear sense of identity and purpose that is fundamental to their value-add, as discussed above.

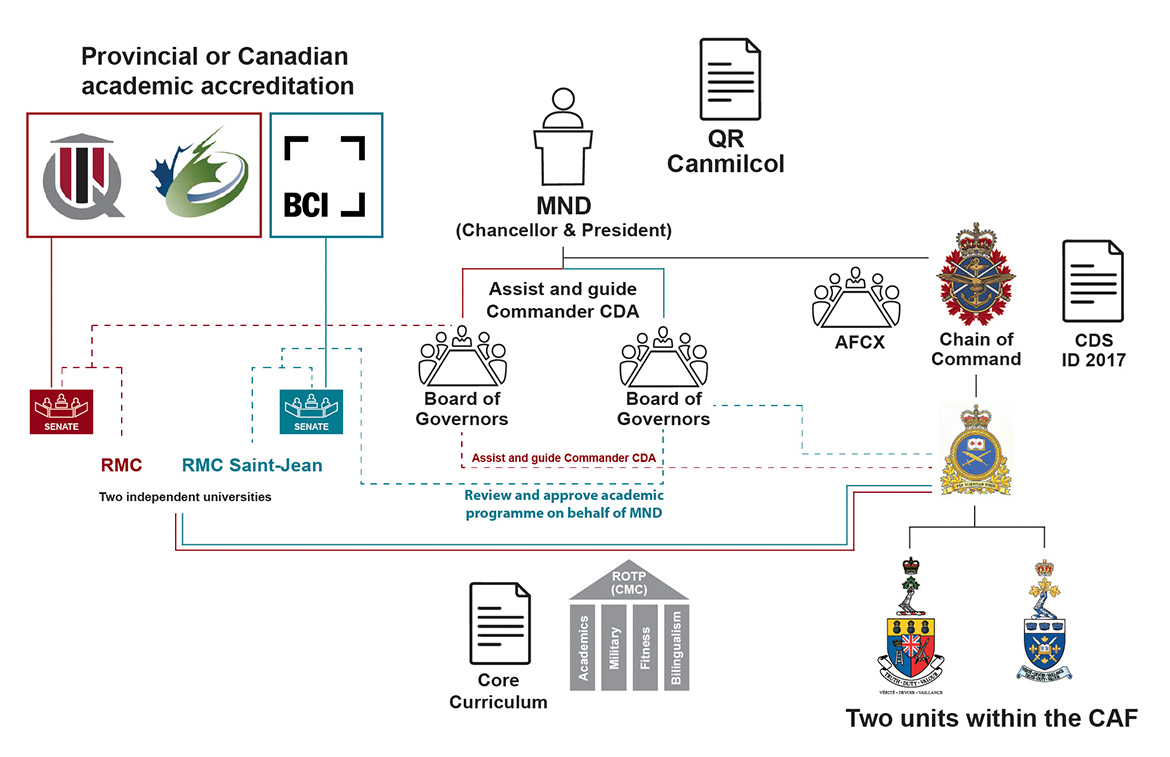

Currently, the governance framework, prescribed inter alia by the Queen’s Regulations and Orders for the Canadian Military Colleges (QR Canmilcols)Footnote 29 looks like this:

Figure 8: Canadian Military Colleges Basic Governance Model - Text version

This figure represents a partial governance structure of the Canadian Military Colleges. The military colleges are both military units and academic institutions and as such, the figure of the Governance Model depicts the dual aspects. Each number (1 to 10) refers to the different parts of the governance structure.

Military Units

- The Minister is the authority for the organization of the Department of National Defence and the Canadian Armed Forces. The Minister has created the Canadian Military Colleges as military units under National Defence Act section 17, to report to the Canadian Defence Academy.

- The Chief of the Defense Staff is the most senior military position. The Chief of the Defense Staff issues all orders and instructions to the Canadian Armed Forces that are required to give effect to the decisions and to carry out the directions of the Government of Canada or the Minister. The Chief of the Defense Staff has direct responsibility for the command, control and administration of the Canadian Armed Forces. The Chief of the Defense Staff establishes promotion requirements including those requirements that must be embedded into the professional education of officers.

- The Armed Forces Council Executive is the senior Canadian Armed Forces governance body and is chaired by the Chief of the Defense Staff. It provides the Chief of the Defense Staff with advice on issues of strategic important to the overall administration and management of the Canadian Armed Forces and the Canadian Profession of Arms, as well as for senior officer career management and succession planning.

- The Commander, Canadian Defence Academy, has command and control authority for (5) the Royal Military College of Canada, in Kingston and the Royal Military College Saint Jean, has assigned responsibilities for the management of Canadian Armed Forces professional development, and has authority for Canadian Armed Forces common programmes. These functions include roles in the oversight of the core curriculum and the four programmes (academic, bilingualism, physical fitness and military leadership) under the Regular Officer Training Plan for the Canadian Military Colleges.

Academic Institutions

- The Minister has also created the Canadian Military Colleges as educational institution under the National Defence Act section 47. This provides the Minister authority to prescribe the governance and administration of educational institutions established for the purpose of defence. The Minister has established the Queen’s Regulations and Orders for the Canadian Military Colleges to provide their direction; these regulations have not seen any significant updates since early 2000s. The Minister is designated Chancellor and President of the Canadian Military Colleges.

- Each institution has degree-granting powers conferred by laws passed by their respective provincial legislature.

- Each institution has its own senate.

- Each senate is charged with abiding by the best practices, processes and guidelines of the Ontario Universities Council of Quality Assurance, and the Bureau de Cooperation Interuniversitaire in Quebec, respectively, and any provincial regulations as applicable, and complying with the standards established by the national engineering accreditation body (Engineers Canada).

Governance

- The learning outcomes of the four programmes of the Regular Officer Training Plan for the Canadian Military Colleges are managed, in part, through the Commander, Canadian Defence Academy, as the training authority for Canadian Armed Forces common programmes. The learning outcomes of the core curriculum are based on military requirements, and as such are under the purview of the Chief of the Defence Staff. The physical fitness and military leadership programmes of the Regular Officer Training Plan for the Canadian Military Colleges are delivered by the two military colleges and the academic and bilingualism programmes are delivered by the two universities.

- The Minister created the boards of governors to assist and guide Comd CDA and the commandants of the military colleges and to approve the academic programme on behalf of the Minister. Each institution has its own boards of governors and, while not having “power” over the universities, they act in an advisory and guidance capacity. Their responsibilities include to review and endorse the core curriculum and the four programmes of Regular Officer Training Plan for the Canadian military colleges. The boards of governors meet once a year with the Armed Forces Council Executive to discuss their activities, the challenges at the Canadian military colleges and the needs of the Canadian Armed Forces.

Within this model, the Minister of National Defence is designated as the Chancellor and President of both CMCs, but is equipped with no specific Terms of Reference. The heads of the CMCs are the two Commandants, who are designated in the QRCanMilCols as the Vice-Chancellors of their respective institutions and who chair the Senate in the absence of the Chancellor. The two Commandants have full command of their organizations and are responsible for their effective operation, including achieving mission objectives, managing resources and fostering a healthy workplace environment.

However, the Commandants are not fully autonomous. They report to the Commander of the Canadian Defence Academy, who in turn reports to the Chief of Military Personnel, who in turn reports to the Chief of the Defence Staff. The Commandants thus sit squarely within the military chain of command and are subordinate to CDA, which sets the training standards, allocates financial resources to the CMCs and serves as the training authority responsible for CAF-common training and education.

Notwithstanding this, the chain of command does not have exclusive authority over the Military Colleges; the Deputy Minister of National Defence holds specific authorities that directly impact the CMCs, the most significant relating to financial resource allocations, infrastructure management and civilian human resource management.

Notionally, the Minister is supported by two Boards of Governors which submit annual reports regarding the activities of both the CMCs and the Boards themselves. Effectively, however, the Boards of Governors – which have undergone a series of changes over their lifespans – function purely as advisory bodies to the Commandants and to the Commander of the Canadian Defence Academy.

Within the CMCs, the Principal (known as the Academic Director at RMC Saint-Jean) serves as the academic head of the College and reports to the Commandant, with a mandate to manage the interface between the military culture of the CAF and the institutional culture of a civilian university. The Principal further functions as the academic advisor to both the Commandant and the Commander of CDA, and is also considered a “senior academic” of the Department of National Defence.

This framework gives rise to significant problems for the CMCs. It is unnecessarily complex, poorly defined and extremely confusing, even to actors within its system. It remains founded in an instrument (QR CanMilCols) that is decades out of date, and it has been stretched sideways to fit into a civilian mould that does not reflect the particular needs, functions or objectives of a military institution.

What is particularly frustrating is that these observations reflect the same findings made by previous reviews; both the 2017 Special Staff Assistance Visit (SSAV)Footnote 30 and the 2017 Office of the Auditor General (OAG) ReportFootnote 31 proposed substantive amendments to the CMC governance model, yet few of their relevant recommendations have been implemented.

This Board thus finds itself back in the same space, proposing a new approach to governance and a series of concrete revisions – particularly in relation to the existence, roles, responsibilities and authorities of the Chancellor, Board of Governors and Principals, but also in relation to the appointment, tenure and career advancement of the Commandant and the Director of Cadets.

Chancellor/President

Beyond conferring degrees at convocation, successive Ministers of National Defence irrespective of political stripe have had little substantive engagement with the CMCs in their role as Chancellor and President. Without defined Terms of Reference, the expected roles and obligations of the Chancellor and President are unclear, and this lack of clarity gives rise to further confusion from other actors within the CMC governance structure regarding how and when to interface appropriately with the Minister.

It also hampers the ability of the CMCs to accomplish some of their key activities. For example, in a civilian university, the Chancellor serves as a titular or ceremonial head of the institution, and by statute presides over convocation ceremonies, confers degrees and acts as an ambassador in advancing institutional interests. The President typically serves as Chief Executive Officer, providing leadership, management and oversight. None of these functions – which are as integral to the functioning of the CMCs as to civilian universities – are easily achieved under a construct wherein the Minister of National Defence of Canada serves as the Chancellor and President of the country’s Military Colleges. In reality, competing demands on the Minister’s time preclude his/her ability to undertake these functions in an effective and sustained way, and yet occupying the position precludes others from taking up the mantle. This enduring challenge – common across political lines since the establishment of the Boards of Governors – was addressed in the 1993 Report of the Ministerial Committee on the Canadian Military Colleges,Footnote 32 which recommended that the Minister of National Defence should be considered a "Visitor" and that each College should elect its own Chancellor, based on recommendations from the Board of Governors.

This Board shares a similar perspective; the current designation of the Minister of National Defence as Chancellor and President contributes significantly to confusion and ineffectiveness vis-à-vis the governance of the CMCs and stands as an impediment to allowing a person better suited for the role (by virtue of position) to take on these roles, particularly in terms of actually leading the institution by serving as an advocate/champion for each College.

Board of Governors

Importing the concept of a Board of Governors from the civilian university context into DND/CAF has also brought significant confusion and uncertainty to the CMCs (although the underlying intent of this approach, in terms of trying to introduce greater accountability to the Military Colleges, is laudable). While in a civilian context the Board of Governors has the authority to approve the institutional strategic plan and budget, to select the President, to evaluate the President’s performance and to oversee remuneration, the Boards of Governors of the CMCs have no such authority. They play no role in civilian hiring, in performance assessment or remuneration of the Commandant or Principal, in financial matters, or in adopting the strategic plans of the Colleges. In fact, they have no actual power. Conversely, they play a limited, albeit important advisory role to the Commandants, the Commander of the Canadian Defence Academy and the Minister (as Chancellor and President). A comparison of the roles and responsibilities of the CMC Boards of Governors compared to Canadian civilian universities is presented at Annex 6.

Calling these two groups of distinguished people “Boards of Governors” is therefore misleading. Instead, they are de facto Advisory Committees and should be referred to as such. As they have no actual or meaningful relationship with the Minister, and their role is to advise and make recommendations to the Commandants and the Commander of the Canadian Defence Academy, their Terms of Reference should further reflect these facts.

Senate

The function of the Senate is to grant degrees and honorary degrees, and the Colleges have empowered a number of Senate Standing Committees, as part of Academic governance, to ensure that the quality of those degrees is of the highest standard. However over time, lack of clarity and misunderstandings regarding this function have caused consternation and confusion.

While it is up to the Senate to ensure that all academic programs are appropriately constituted in order to meet the applicable university degree requirements, it is up to the CMCs to establish and periodically review/amend the list of programs offered at the Colleges in light of institutional priorities, with the Commandant holding authority to allocate resources and set priorities in relation to academic programs. Indeed, it is within the power and authority of the federally regulated and federally run CMCs to establish and make changes to the list of academic programs at the Military Colleges, not the Senate – a misunderstanding that was recently perpetuated via the amendments approved to QRCanMilCols Chapter 2, Part : paras 2.50 (2) and 2.56 (2) pursuant to the November 2021Footnote 33 exchange of correspondence between the Minister and the Commandant of RMC. More specifically, the assertion that the Senate is the “final authority for all academic matters” should be qualified. As such, the Board believes that a further amendment to the QRCanMilCols is required to clarify the Senate’s actual authority and reassert the primacy of the CMCs in making determinations regarding the academic programs at the Military Colleges.

Commandant

The Commandants of the CMCs are the leaders of the Military Colleges. In this regard, their roles are akin to those of a President and Vice-Chancellor in a civilian university; consistent with the findings of the 2017 OAG Report, the Board sees the Commandants as the preeminent institutional leaders of large and complex organizations who ultimately hold responsibility and authority for the training, education and wellbeing of the N/OCdts. It is appropriate, therefore, that they be identified as such, by designating them as the President and Vice-Chancellor of the Colleges. The effect of this would not only help clarify what they do and the position they occupy within the institution, but would further help underscore the fact that the CMCs are military institutions, led by military officers, for military purposes. This designation will also firmly establish the Commandant as Chair of the Senate, and as the executive head and the formal representative of the institution. Having the Commandant in this role is key to creating a shared vision for Canada’s Military Colleges.

Such a designation must be accompanied by changes to the tenure of the Commandants. At present, the length of time in position has varied among incumbents, but on average has lasted no more than two years, as the office holders regularly depart for promotion or reassignment.

It is not realistic to expect that a leader can help effect the changes that are required in the CMCs, or provide the degree of stability needed at the top to ensure the ongoing health and success of the institutions, if they are given only two years to do so. Significantly more time is required in the position to establish baseline knowledge, build trust, foster relationships and develop networks, in support of the overall mandate of the Colleges. These observations are not new; the high turnover of senior military personnel has been highlighted multiple times in previous reports as a critical impediment to effective governance at the CMCs and reiterated repeatedly during this Board’s Listening Sessions by military staff and academic faculty members. In response, the Report of the RMC Board of Governors by the Withers’ Study GroupFootnote 34 recommended a tenure of five years, while the SSAV recommended a minimum tenure of three years, but noted that a four-to-five-year tenure would be optimal.Footnote 35 The Board recommends that the CAF extend the appointments of the Commandants to a minimum of four years and develop innovative human resource practices to break the cycle of two-year appointments.

Given that the Military Colleges are unique national institutions with a global profile, responsible for a subset of particularly vulnerable members of the CAF, exposed to regular public scrutiny, and responsible for foundational leadership training within the Profession of Arms, the Board also believes that it is appropriate that the Commandant be a General Officer/Flag Officer. While other organizations within the CAF of similar size are led by officers at the rank of Colonel/Captain(N) and below, it is the Board’s view that this speaks more to the leadership talent within the CAF (wherein even junior officers hold positions with spans of responsibility that far outstrip any comparable position within a civilian context) than to the import of those organizations.Footnote 36 Furthermore, the distinct features and functions of the CMCs allow for their distinct treatment.

Nevertheless, the Board accepts that the role, responsibilities, level of risk and budget that the Commandant of RMC Saint-Jean currently manages are better aligned with the rank of Colonel/Captain(N) than with the rank of Brigadier-General. Therefore, despite the Board’s views regarding the importance of ensuring equality between the two Colleges and increased stature for RMC Saint-Jean, it is comfortable in accepting that an upgrade to the rank of the Commandant should happen only in due time and in step with the proposals found elsewhere in this Report to grow the size of the N/OCdt body and increase the program offerings at RMC Saint-Jean.

When this occurs, the position of Director of Cadets at RMC Saint-Jean should correspondingly be upgraded from a Lieutenant-Colonel/Commander to a Colonel/Captain (Navy), premised on the same rationale. This follows the logic employed in the Special Staff Assistance Visit Report regarding its recommendation to upgrade the position of Director of Cadets at RMC from a Lieutenant-Colonel/Commander to a Colonel/Captain(N).

Aside from the question of rank, not every officer is necessarily the right fit for leading the Military Colleges. Selecting Commandants with the right skills, competencies, character and knowledge for this unique role will be critical to ensuring the overall outcomes that this Board is seeking to achieve. Leading a military unit within which an academic institution is embedded presents challenges that are not common across the CAF, particularly one that is responsible for educating and training some of the youngest and most at-risk members of the Profession of Arms.

Decades of experience as a CAF officer should prepare the Commandant to lead the military and public service aspects of the CMCs. Special consideration should also be given to the knowledge and skills required to run an academic institution. As most officers may not have received such exposure before this stage in their career, a newly appointed Commandant should be required to enroll in a Development Period Four Fellowship Program at a civilian university focused on understanding university governance and operations. Timely selection of the Commandant may also allow exposure to university President training programs that are available in Canada and the United States.

The Board understands that the current selection process does not lend itself to equipping future Commandants with the necessary competencies and skills and considers that access to the right training and experience is essential to enable their success. This means that the selection process must happen much earlier, in effect “deep selecting” the Commandants well ahead of their respective appointments.

At RMC, this would mean identifying the next Commandant as a Colonel/Captain(N) and sending them on their Development Period Four training with the express intent of selecting them to be the Commandant in the future. It may also require the Chief of the Defence Staff and the Minister of National Defence to exercise an “Acting While So Employed” promotion process to align timing. At RMC Saint-Jean, until changes are made to up-rank the position of Commandant to a Brigadier-General, the future Commandant should attend their Development Period Four training either prior to promotion to Colonel/Captain(N) or immediately upon promotion, to provide them the time necessary to complete four years at the helm of the institution.

Principal

There remains much confusion regarding the role of the Principal at the CMCs (known as the Academic Director at RMC Saint-Jean), largely because of an erroneous tendency to import civilian university concepts into the Military College construct. This creates tension between the Commandant and Principal positions, breeds resentment between military and academic faculty and staff, and undermines the identity of the CMCs as first and foremost military institutions.

For example, many members of the academic community at the CMCs articulated an expectation that the Principal / Academic Director should be empowered to perform the functions associated with the President (also called the Principal or Rector) of a civilian university, such as control of financial resources, control of hiring decisions and involvement in dispute resolution processes within the academic faculty. The fact that the Principal / Academic Director does not have those authorities at the CMCs, and that they are vested instead in the Commandant, was a source of consternation and frustration for many academics.

These sentiments are understandable but misplaced. In reality, the role of the Principal / Academic Director at the Military Colleges is more akin to that of a Provost and Vice-President Academic at a civilian university, and it should be re-named accordingly. This would better reflect both what the position entails and what it does not, helping to create clarity and to set more appropriate expectations.

In better aligning the title to the function of the position, thought must also be given to the way in which this position is filled. At present, the Principal at RMC is appointed through a Governor in Council (GIC) process (a process that is currently being replicated at RMC Saint-Jean), which lends it gravitas and helps ensure a high calibre of candidate. Those who have filled the roles to date have brought professional seniority, strong leadership, academic credibility and high-quality experience to the job, yielding important benefits to the CMCs. On the flip side, appointing the Principal / Academic Director via a GIC process typically results in hiring someone who may not be expecting, at this stage of their career, to report to another executive or be hierarchically subordinate to a military Commandant.

To better clarify the parameters of the position and associated expectations, both for the office-holder and for other stakeholders at the CMCs, the position of Principal should be re-designated as Provost and Vice-President Academic & Research. It should also be made a GIC appointment to attract the right talent and appropriate experience level for this position – with the clear caveat that the Provost and Vice-President Academic & Research will be working with, and subordinate to, the Commandant. Representatives from both DND and the CAF should serve on the Appointment Committees, with the Commandants of the respective Colleges best suited to serve as the CAF Representative on the Committee.

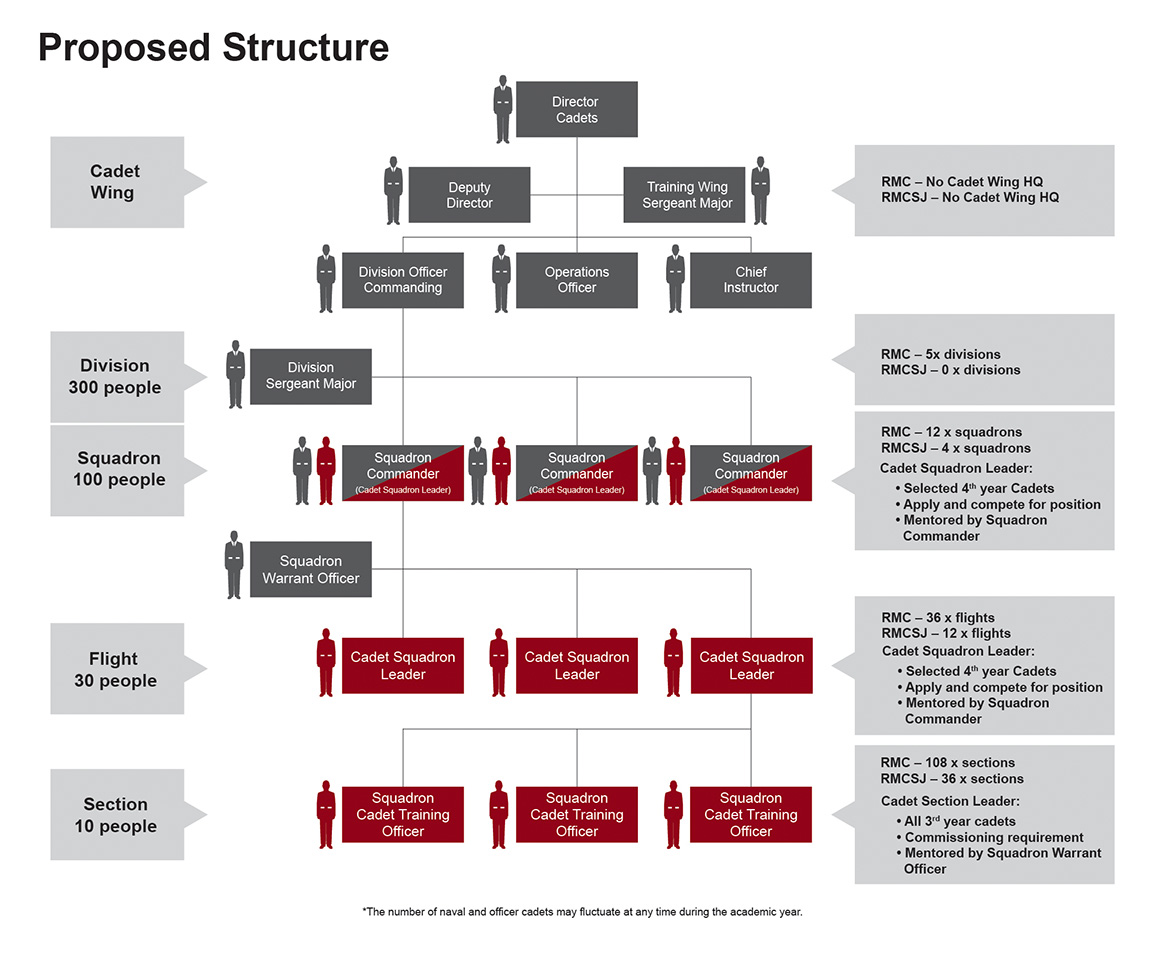

Director of Cadets

A key figure in the lives of the N/OCdts and a lynchpin in the success of their military training experience is the Director of Cadets. This role thus requires the right person for the right length of time. Two years in position, which has become the general norm, is insufficient. In line with the arguments made for extending the tenure of the Commandant, the Board believes that a longer tenure is also required for the Director of Cadets. This will create greater institutional stability, deepen trust with N/OCdts, and provide more time to implement change and see initiatives through.

Given that the driving argument behind longer tenure is both a need for stability and the ability to oversee and implement effective change management, it is also important that the terms of the Commandant, the Provost and Vice-President Academic & Research and the Director of Cadets be staggered, so as to avoid a situation in which all three are arriving or departing in the same year. This will further enhance the positive experiences of the N/OCdts during their three-to-four-year journeys at the Colleges, as they will be able to build more enduring and trusting relationships with the key individuals who have an impact on their daily lives. While there are various combinations and permutations that can achieve the desired effect, the Board views it as critical that the three positions be managed together in this regard.

Extending the length of tenure for the Director of Cadets should in no way preclude career advancement for the incumbent; a posting at the Colleges should be viewed as an asset and the timing of promotion opportunities should be aligned accordingly.

In sum, the temptation to turn towards civilian universities for inspiration in respect of CMC governance frameworks must be resisted unless it makes specific sense to do so. When efforts to make the Military Colleges align with the civilian model have a clear purpose tied to their institutional identity as a military unit responsible for training and educating members of the Profession of Arms, then those should continue. When such efforts confuse or undermine this identity and purpose, they need to be revised.

Recommendation 5

Remove the Minister of National Defence from the position of Chancellor and President of the two Canadian Military Colleges. Amend the Queen’s Regulations and Orders for the Canadian Military Colleges accordingly.

Recommendation 6

Appoint an eminent Canadian to the ceremonial role of Chancellor of the two Canadian Military Colleges. Amend the Queen’s Regulations and Orders for the Canadian Military Colleges accordingly.

Recommendation 7

Re-designate the Board of Governors at each Military College as an Advisory Committee that advises and makes recommendations to the Commandant. Update the Queen’s Regulations and Orders for the Canadian Military Colleges accordingly.

Recommendation 8

Clarify the parameters of the Senate’s authority and stipulate that the responsibility to allocate resources and set priorities in relation to academic programs at the Military Colleges lies with the Commandant. Update the Queen’s Regulations and Orders for the Canadian Military Colleges accordingly.

Recommendation 9

Designate the Commandants as the “President and Vice-Chancellor" of their respective Military Colleges, vested with appropriate authorities and responsibilities. Amend the Queen’s Regulations and Orders for the Canadian Military Colleges accordingly.

Recommendation 10

Establish the tenure of the Commandant at each Military College for a minimum of four years.

Recommendation 11

“Deep select” the Commandant for each Military College and use a Developmental Period Four Fellowship Program and/or University President Training Program to expose them to university governance and operations.

Recommendation 12

Re-designate the Principal at each Military College as the Provost and Vice-President Academic & Research and appoint them, via a Governor-in-Council process, as the most senior academic officer of their respective Colleges, reporting to the Commandant. Amend the Queen’s Regulations and Orders for the Canadian Military Colleges accordingly.

Recommendation 13

Establish the tenure of the Director of Cadets for a minimum of three years.

Program: The Academic Pillar

The Regular Officer Training Plan - Canadian Military Colleges (ROTP CMC) is a fully residential four-year (or five-year) program comprising academics, military training, physical fitness and bilingualism. It is this 4-Pillar program, described above, that differentiates the Military Colleges from civilian universities, and thus it is this program that is at the core of the CMC’s value proposition. Without a strong, distinct and rationalized Military College program that goes beyond the academic courses all other officers receive through their civilian university education, the additional costs of running the CMCs are not justifiable and the entire raison d’être of the Military Colleges is called into question.

To date, the CMCs have relied on the 4-Pillar model as the value-add for the Colleges. In reality, however, the Academic Pillar has functioned as the lodestone around which the other Pillars take a lesser role. As such, while a detailed examination of these four Pillars led the Board to conclude that the model addresses the right substantive areas, the Board also found that

- the program in its current form is flawed, and has contributed to a growing disconnect between the CMCs and the Profession of Arms; and

- the Academic Pillar merits particular attention because of the impact it has had on the overall evolution and success of the Canadian Military Colleges.

On that front, the CMCs benefit from a cadre of well-respected, high-calibre and actively engaged academic faculty and staff who develop and deliver a wide range of top-quality programs and courses. They are committed to excellence, enthusiastic about education and research, and genuinely interested in the success of the N/OCdts, who, in turn, hold them in high regard.

In recent years – in response to growing opportunities, fresh ideas and evolving trends – faculty and staff have created new programs, identified new degrees, pursued new areas of study and added new personnel. This has been exciting for the institution and very well received by the N/OCdts. Unfortunately, while each of these initiatives may have been positive in isolation, the collective result has been costly growth - in terms of money, human resources and time – that increasingly runs at cross-purposes with the broader objectives of the Military Colleges. These costs are now too big to ignore, too difficult to justify and too entrenched to be solved with superficial fixes. An examination of the current size and scope of the academic program, its linkages to the mandate and mission of the CAF, and its impact on the other Pillars of the ROTP CMC reveal that meaningful reform to this Pillar is required.

Size & Scope

The starting point for these problems is the size of the academic program and the scope of its offerings, particularly as compared to the size of the student body. At present, RMC has three Faculties (Social Sciences and Humanities, Engineering, and Sciences), with fourteen Departments that offer 44 undergraduate programs (22 in English and 22 in French). The academic faculty includes 189 indeterminate University Teacher (UT) positions plus 39 military faculty positions, and is supplemented with additional term and sessional instructors, though not all UT or military faculty positions are filled at all times. RMC typically has around 1,100 N/OCdts who are part of the ROTP and an additional 3,000 post-graduate, part-time, and other students. RMC Saint-Jean has two Faculties (Social Sciences and Sciences), runs three Departments (Language, Science, and Humanities and Social Sciences) in addition to Professional Military Education, and provides one university-level program in International Studies. RMC Saint-Jean employs 40 faculty and teaching staff for a student body of 350 (including university and CÉGEP offerings). Academic salaries are not the only driver of costs at the Military Colleges, but they are significant.

The program offerings at the Military Colleges also extend across a variety of disciplines, and while this breadth of options is popular with the N/OCdts, it is not necessary to meet the needs of the CAF; the CAF is largely agnostic to the nature of the undergraduate degree earned, and with only a very few exceptions, almost all degrees and programs are acceptable for almost all occupations. Although Canada is not alone in offering a wider variety of degrees and programs (with countries such as Japan and Germany taking a similar approach), this differs from many foreign military academies, which offer more tailored degrees with clear thematic ties to the Profession of Arms and the requirements of their Armed Forces.

The wide range of types of degrees and programs offered at the Military Colleges further gives rise to the creation of a high number of courses. Due to this volume of courses and programs, compared to the number of N/OCdts, many of them are seriously undersubscribed. For example, the Mathematics, English Culture & Communications, French Culture & Communications and Economics programs have all failed to graduate more than fifteen participants in any one of the last five years yet have consistently been supported by over forty academic faculty members. Many courses consequently suffer the same fate, compounded by the duplication of course offerings to fulfill bilingualism imperatives, resulting in classes with as few as three N/OCdts. Despite a recent decision to impose a minimum threshold for running a course (now set at three N/OCdts per class), class sizes remain significantly lower than in civilian universities and the overall number of course offerings remains vastly out of sync with national averages. This contributes to an associated issue, which is the very low ratio of N/OCdts to faculty; at both CMCs this figure stands at 8:1 which far outweighs the average of 21:1 for comparable Canadian civilian universities, as detailed above (see Figures 6 and 7).

Another factor driving up the number of course offerings, while concurrently imposing additional demands on the time of the N/OCdts, is the 16-credit Core Curriculum. As noted above, this series of required courses represents the minimum content that N/OCdts must acquire as part of their degrees, in two thematic areas

- Math and Sciences, and

- Canadian History, Language and Culture, Political Science, International Relations and Leadership and Ethics.

The Core Curriculum amounts to a significant portion of the approximately 40-credit Social Sciences & Humanities degree and turns Engineering into a 48–51-credit degree program that requires a minor in Social Sciences & Humanities. It also requires significant human resources to deliver. While the Core Curriculum provides an excellent academic foundation for CMC graduates, when taking into consideration the reality that it is only one component of the ROTP CMC program, it takes up too much of the N/OCdts’ time and constitutes “too much of a good thing.”

The fact that RMC Saint-Jean runs a Collège d’enseignement général et professionnel (CÉGEP) program also contributes to the expansive size and scope of the CMCs. This two-year college-level program (equivalent to Grade 12 and First Year university in the rest of Canada) is a unique feature of Quebec’s higher education system and is normally provided at nominal cost to residents of Quebec by the Government of Quebec. Because the federal government has no authority unto itself to offer the program, it is contracted out by RMC Saint-Jean to the CÉGEP de Saint-Jean-sur-Richelieu for support and accreditation. Moreover, running a second program alongside university-level education programs means that a high number of Education Specialist (EDS) public service positions must also be funded. Additionally, because those N/OCdts who go into CÉGEP do so at the ages of 16 and 17, there are additional downstream costs for the government in terms of pension and salary dollars due to how young these individuals are when they become employees of the Canadian Armed Forces.

A smaller but impactful issue is the degree of variance between the academic calendars at the two Colleges. Due to the fact that RMC Saint-Jean is constrained by the provincially set CÉGEP calendar, it has limited flexibility with scheduling, which in turn makes it difficult to coordinate its timings with the CAF and with RMC in relation to everything from course timetables to special events and exams. More specifically, the CÉGEP academic term is 16 weeks, including exam weeks, whereas Quebec and Ontario universities have 15-week academic terms, including exams. While this may seem inconsequential, the discrepancy has a profound effect on the possibilities for the movement of N/OCdts between Colleges in order to leverage different course offerings, language learning opportunities and interchange possibilities.

For example, N/OCdts at RMC Saint-Jean must return earlier than those at RMC, resulting in less summer training time, especially military training time, and that further eliminates many possibilities for synergies around things like distance learning and virtual classes. As a result, there is a high degree of duplication in course offerings and materials between the Colleges that could otherwise be reduced.

The cumulative effect of all of these factors is to drive up costs; at present, the Canadian Military Colleges are 1.6 times (RMC) and 4 times (RMC Saint-Jean) more expensive than comparable civilian universities, when adjusted for non-academic activities.Footnote 37 While the calibre, professionalism and overall quality of academics at the Military Colleges is unassailable, it far surpasses industry standards in relation to class size, student-to-professor ratio and quantity of offerings and cannot be justified against the baseline objective of delivering a credible undergraduate university degree.

Strength of Linkages

Another problem facing the academic program is its tenuous relationship with the defence and security mandate of the CAF. Academic faculty and staff are cognizant of the mission of the CMCs, and they often seek ways to incorporate officer development and leadership skills formally and informally into their programs. This manifests in myriad ways, from the development of courses that directly support CAF operations (e.g. CCE409 Combustion and Explosives Engineering) and the establishment of course reading lists that stimulate relevant reflections and discussions (e.g. ENE331 World Literature: Crisis and Conflict) to the inclusion of experiential elements within courses that build practical officership skills. Such efforts are laudable and valuable. They are appreciated by the N/OCdts and reflect the care with which the faculty members typically engage with the student body.

However, these approaches are limited and ad hoc. They are not standardized or easily replicable, they are not tethered to specific learning outcomes and they are not systematically measured. Moreover, beyond these efforts, there are no explicit links between the Academic Pillar and the overarching objectives of the CMC’s professional military education and officer development, rendering the relationship negligible at best. To be clear, this is not a failing of any individual, and it does not reflect on character, capability or professionalism. Rather, it is a reflection of a flaw in the way the system was originally designed and has evolved over decades.

The vast assortment of programs noted above dilutes focus and clarity, with the CMCs being neither Liberal Arts schools nor Engineering or Technical schools. Although there is strength in some aspects of this mix, the lack of a clear identity as a military academy makes it difficult for the academic program as a whole to anchor itself to a clear vision or sense of common institutional purpose.

Impact on the Other Pillars

In addition to resource concerns, the amount of time required to fulfill the requirements of the academic program at the CMCs creates significant issues regarding its impact on other key elements of the Military College experience, severely hampering the ability of N/OCdts to invest sufficient energy into anything else. Any “extra” hours are found in the early mornings or late evenings, which effectively relegates all non-academic activities to the margins of the workday and to weekends. This in turn creates undue stress, negatively impacts sleep and sends a clear message regarding the prioritization of academics at the expense of language learning, military skills training, fitness, health and wellbeing, and leadership development.

A Way Forward

In short, the proliferation of programs and courses offered at the Military Colleges, coupled with the high number of academic faculty and staff currently employed to deliver those activities – particularly in relation to the overall number of N/OCdts, and in part given the lack of harmonized schedules between the Colleges – has driven up staffing levels and the associated support and operating costs to problematic levels. Coupled with the lack of clear connection between academics and the CAF’s defence and security mandate, an over-prioritization of academic studies at the expense of other important program elements, and the availability of alternative models that can effectively develop strong officers, the Academic Pillar as currently configured is too expansive and too expensive to support.

The Board accepts that the Military Colleges are unique institutions that require significant investment. Whether the costs are more or less than those of civilian institutions is only one of the factors the Board has taken into consideration in assessing the value proposition of the Colleges. However, it is critical that public money be well spent. In this regard, costs must not only be reasonable, but they must also be directly tied to the raison d’être of the Military Colleges and must directly support the objectives of the organization that they exist to serve.

Accordingly, and in line with common management practice in government and across academia, there is a need to redeploy existing financial and human resources from within the academic program towards higher-priority items, to streamline offerings and to strengthen linkages to the requirements of the Profession of Arms.

Several groups of interconnected reforms are needed to accomplish this. In developing this list, the Board has considered various approaches taken by other military academies, together with innovations in the civilian university context.

Firstly, it makes no sense that the one undergraduate degree offered at the Military Colleges that is specifically tied to the military identity of the institutions – the Bachelor of Military Arts and Science – is not available to N/OCdts.Footnote 38 Going forward, this degree should be added to the offerings within the ROTP CMC, to bring the total to four degrees:

- A Bachelor of Arts

- A Bachelor of Science

- A Bachelor of Military Arts & Science

- A Bachelor of Engineering

The first three degrees would be offered at RMC Saint-Jean, and all four would be offered at RMC.

Secondly, the number of programs and courses offered by the Canadian Military Colleges needs to be significantly reduced. All programs that have neither accepted nor graduated more than 15 N/OCdts at least once in the last five years should be eliminated, and more reductions should be undertaken in line with the intent to significantly streamline offerings that are undersubscribed. Alongside this, a commensurate reduction in the number of University Teacher (UT) positions at RMC should occur. At both Colleges, a minimum 15:1 student-to-faculty ratio should be implemented. In this way, the CMCs would transition from having a N/OCdt-to-faculty ratio that is one-third of the comparable average, to two-thirds of the comparable civilian university average. This would maintain small class sizes and personal connections between faculty and students, but also take into account the requirement to improve the financial efficiency of these institutions.

Thirdly, the number of N/OCdts must also be increased at both Colleges, to reduce costs per N/OCdt, maximize resources and effectively leverage the CMCs for the benefit of the CAF. In total, the number of N/OCdts should be increased to a minimum of 1,850 (or increased in line with limits imposed by the CAF regarding its ability to absorb and train new officers), to be distributed between the two Colleges.

The Board considered two permutations regarding the appropriate distribution of this growth. The first would see the number of N/OCdts at RMC increase from 1,000 to 1,500, with the number of N/OCdts at RMC Saint-Jean increasing from 100 to 350. This option could require building additional residences in Kingston. The second permutation would see the number of N/OCdts at RMC increase from 1,000 to 1,200, while the number of N/OCdts at RMC Saint-Jean would increase from 100 to 650. Taking into account a number of factors – the current infrastructure at both Colleges, the existing number of faculty, the respective areas of expertise resident at each College, the opportunities to create greater equality between the Colleges, the importance of avoiding the gender segregation that would arise if RMC Saint-Jean focused exclusively on Liberal Arts and RMC focused exclusively on Science & Technology, and the proposed changes to the degree offerings – the Board is of the view that the second option should be pursued.

Nevertheless, the Board is conscious that such changes could create unintended consequences, particularly in relation to the presence of the Osside Institute at RMC Saint-Jean, and must be considered among factors such as infrastructure, logistical feasibility, program delivery considerations and existing contractual requirements. Thus, the Board believes that the Canadian Defence Academy and the CMCs themselves are ultimately best placed to make final determinations regarding allocation of growth between the two Colleges.

Fourthly, the Core Curriculum should be eliminated. Its purpose is valid and important, and it is laudable to provide a balanced education that includes arts and science to all N/OCdts regardless of their field of study, with a view to instilling values and ethics, developing solid judgment and critical thinking abilities, establishing a strong foundation of relevant knowledge and building effective writing skills. But the intensive staff complement and significant cost required to deliver it make the Core Curriculum difficult to rationalize. This is particularly true given the availability of alternative mechanisms for achieving similar outcomes.

Fifthly, the CÉGEP program at RMC Saint-Jean should be eliminated. Over the past five years, it has cost between $2.2 million and $3.5 million annuallyFootnote 39 to pay the CÉGEP de Saint-Jean-sur-Richelieu (CSJR) for support and accreditation of the RMC Saint-Jean program, since the Military College does not have authority to deliver this program, which includes approximately $500,000 to accredit and administer these programs. In addition, it pays approximately $1.5 million in salary dollars to the education services staff at RMC Saint-Jean to deliver the courses under the CÉGEP program, meaning that in total, the Government of Canada pays over $5 million a year to offer a program that is within provincial jurisdiction and that is already offered at only nominal cost to all residents of Quebec. These expenditures are indefensible, particularly in the absence of any compelling rationale for running a CÉGEP at a Military College.

In advancing the recommendation to eliminate the CÉGEP program, the Board has considered concerns raised during consultations regarding the potential impact of this loss to RMC Saint-Jean. These include fears that it will undermine recruiting efforts in Quebec and decrease Quebecers’s interest in attending the CMCs, diminish the status of RMC Saint-Jean, hurt efforts to maintain a strong Francophone presence in the CAF and lead to the eventual closure of the institution. Most of these arguments are speculative, though some raise valid considerations. Nevertheless, all can be effectively managed and mitigated.

For example, the argument that the CÉGEP program at RMC Saint-Jean is a primary driver of recruitment in Quebec is not borne out by the facts, and the notion that the CAF must maintain the program in order to meet recruiting targets in Quebec is flawed. Nonetheless, should the CAF determine that eliminating the CÉGEP program is negatively impacting traditional sources of recruits in Quebec, various alternatives are available to offset this – particularly via new, targeted strategies. For instance, the CAF could enroll interested CÉGEP students in the Primary Reserve Force for periods of military training during the summer months, until those students have completed either one or two years of CÉGEP, and then enroll them as Regular Force officers under a paid education program. Alternatively, CÉGEP students could be enrolled under the ROTP Civ U program and attend civilian CÉGEPs at no cost to the Government of Canada, entering into the CMCs after the completion of their first or second year of study. In all cases, CAF recruiting efforts are likely to be more impactful when they can be concentrated on the 48 CÉGEPs and approximately 60 private colleges in Quebec, rather than being spread more broadly across the 521 secondary schools in the province. These are but a few options for a revised approach to ensuring suitable recruitment from residents of Quebec into the CAF.