Summative evaluation of the Canada Pension Plan - Retirement pension and survivor benefits

Alternate formats

Summative Evaluation of the Canada Pension Plan – Retirement Pension and Survivor Benefits [PDF - 899 KB]

Large print, braille, MP3 (audio), e-text and DAISY formats are available on demand by ordering online or calling 1 800 O-Canada (1-800-622-6232). If you use a teletypewriter (TTY), call 1-800-926-9105.

List of abbreviations

- CPP: Canada Pension Plan

- CRA: Canada Revenue Agency

- ESDC: Employment and Social Development Canada

- GIS: Guaranteed Income Supplement

- LAD: Longitudinal Administrative Databank

- LICO: Low Income Cut-Off

- OAS: Old Age Security

- OECD: Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development

- QPP: Quebec Pension Plan

- SFS: Survey of Financial Security

- SLID: Survey of Labour and Income Dynamics

Executive summary

This evaluation examines the Canada Pension Plan (CPP) retirement pension and survivor benefits and covers the period from 1992 to 2012 and summarizes the evidence collected from 14 in-depth technical studies prepared specifically for this evaluation (see Appendix 2). This is the first summative evaluation focusing specifically on the retirement pension and survivor benefits since 1997.

The CPP is a mandatoryFootnote 1 contributory program that is funded by the contributions of employees, employers and self-employed persons, and by the revenue earned on CPP investments. The intent of the CPP is to provide contributors and their families with a minimum level of income replacement upon the retirement, disability or death of a wage earner. The CPP complements the two other pillars of the retirement income system (universal support through the Old Age Security/Guaranteed Income Supplement and private savings). The CPP was not designed to meet all financial needs in retirement, but to provide contributors with income up to 25% of pensionable earnings – which can be built upon from other income sources.

The CPP provides contributors and their families with three major types of benefits:

- CPP retirement pension: provides a monthly taxable benefit to retired contributors who are at least 60 years old. To qualify, a person must have worked and have made at least one valid contribution to the CPP.

- CPP survivor benefits: paid to a deceased contributor’s estate, if sufficient contributions were made. Benefits may also be available to a surviving spouse or common-law partner (depending on their age and the presence of children and/or disability), and to dependent children (depending on their age).

- CPP disability pension: paid to people who have made enough contributions to the CPP and who are disabled and cannot work at any job on a regular basis. Benefits may also be available to their dependent children.

Within the period being evaluated (1992 to 2012), reforms were introduced to change the funding from pay-as-you-go (i.e. where contributions pay for all benefits) to steady-state (where contributions are used to partially finance a fund whose earnings will be used after 2022). This is when the large cohort of baby boomers will have largely retired from the labour force such that annual contributions will need to be supplemented by income from the fund to pay benefits.

This report summarizes findings related to a number of topics including the profile of CPP beneficiaries, the CPP income share and income replacement, the contribution of the program to economic well-being, program delivery, the CPP impact on labour market participation, and program administrative/delivery costs.

Infographic: Canada Pension Plan (CPP) Evaluation

This infographic provides a visual narrative of the Summative evaluation of the Canada Pension Plan - Retirement pension and survivor benefits.

Key findings

Profile of beneficiaries

Since the inception of the program in 1966, there has been a significant increase in the labour force participation of women. Over the evaluation period (1992 to 2012), these changes led to an increase in the proportion of retirement pension beneficiaries who are female (to roughly 50%) and a decrease in the share of survivor benefit recipients who are female (from 90% to 80%). While more women are contributing to (and drawing benefits from) the program, women who have lost a spouse remain financially vulnerable. The reason for this is that women tend to live an average of 4 to 5 years longer than men, while also getting married two years earlier than men, on average. Thus, they are expected to continue to require financial support for up to 6 or 7 additional years without their spouse. As such, survivor financial well-being can be seen more in terms of maintaining important consumption patterns (such as paying for children’s education).

Participation in the program varies by age and marital status – those over age 70 and married represent a higher proportion of recipients. Recent immigrants (landed since 1990) were significantly less likely than both longer-term immigrants and non-immigrants to be program beneficiaries. Immigrants who landed since 1980 represent 10% of the total population of 70-79 year olds, but only 6% of CPP beneficiaries in this age group. Generally speaking, participation is lower among those who made fewer CPP contributions.

Income share and replacement

Among those over age 70, the CPP retirement pension represents about a quarter of their retirement income, varying by factors such as age, pre-retirement income, immigration status, and cohort (i.e. start of CPP benefit receipt). It replaces a significant amount of pre-retirement income and is a large source of retirement income for low-wage earners. According to the focus groups, CPP recipients consider their benefits to be positive contributors to their well-being, insofar that it would have a negative economic impact if they did not receive them. Those with lower incomes tend to indicate that the CPP is more important to their overall well-being.

Among those over age 70, nearly 100%Footnote 2 who are eligible for a retirement pension receive one. Where non-participation exists among those eligible, it can be explained by awareness and/or limitations in the knowledge, skills and confidence that constitute financial literacy. Other factors such as complex program design, insufficient government outreach efforts, and certain characteristics of the target population may also be associated with non-participation.

Contribution to well-being

The CPP is a significant contributor to well-being, as measured by financial viability. The program is an important contributor to this type of economic well-being, particularly for those with fewer income resources in retirement. Indeed, aggregate poverty levels among retirees would increase in the absence of the CPP, with one study suggesting that the presence of a retirement pension reduced the incidence of low income by about half for recipients between 70 and 79 years old.Footnote 3

Program delivery

Service provision has been made more modern with the implementation of web-based service points. That being said, service and outreach challenges still exist for older seniors (some of whom lack computer literacy), Aboriginal Canadians and immigrants (who tend to have challenges with application processes due to language barriers), and residents of remote areas (who may have limited access to the internet or Service Canada centres). In addition, processing time for survivor benefits, and the two-tiered structure of personal service were flagged as in need of improvement.

Although applicants’ experiences were generally positive, the evaluation found that some applicants lacked an understanding of combined benefits, benefit calculation/entitlement, the child-rearing provision, credit splitting, the combining of pensions from other countries, and the Post-Retirement Benefit.

Impact of labour market participation

Labour force participation among recipients of a CPP retirement pension increased during the evaluation period, particularly among higher income retirees and male retirees. The majority of the studies indicated that receipt of a survivor pension tended to have no effect on the propensity to continue working.

Receipt of a CPP pension affects other sources of income (e.g. by increasing a beneficiary’s total income, a smaller proportion of that income would be provided by income tested benefits such as the Guaranteed Income Supplement or Social Assistance). However, the receipt of Old Age Security pension benefits remains unaffected for those over 65 years of age with an annual income of less than $73,756 for the 2016 taxation year. Women tend to be affected more by the resultant increase in taxes than men when comparing a non-CPP scenario to one in which the CPP is present. However, this is because incomes are also higher with CPP than without it – the net benefit of participation is positive.

Administrative and delivery costs

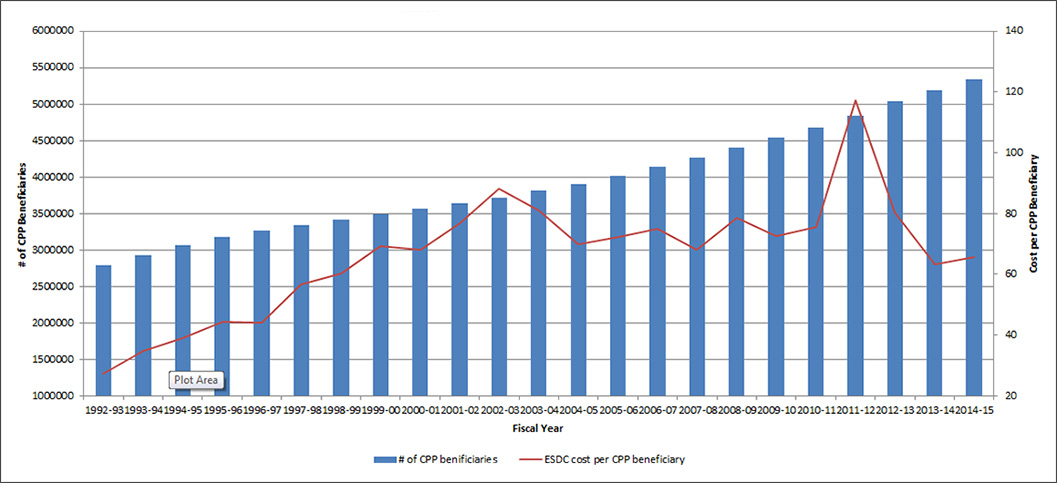

From 1992-93 to 2014-15, the total administrative cost of the CPP in nominal dollars (which has five components including ESDC administrative costs and CPP Investment Board costs) increased steadily – from $167.7 million to $1.3 billion. Despite this overall trend in total CPP administrative costs, ESDC administrative costs have remained relatively stable since 2002-03. Between 1992-93 and 2002-03, ESDC administrative costs increased from $76.6 million to $328.0 million, but since then they have fluctuated fairly little (reaching $351.0 million in 2014-15) – even though there was a 43.5% increase in the number of CPP beneficiaries since 2002-03. The majority of the total CPP administrative cost increase over this latter period was due to an increase in CPP Investment Board costs (from $12.9 million in 2002-03 to $803.0 million in 2014-15).

Recommendations

- Address deficiencies in the administrative data by ensuring that measures appropriate to evaluation needs are included at source. This would include information on employment history, marital status history (to address problems with assessing survivor benefits take-up rates), and a clearer disaggregation of CPP benefits (such as when retirement and survivor benefits are combined, but the specific benefit cannot be deduced due to the formula used to calculate combined benefits).

- Improve communication and outreach with CPP clients (and particularly Aboriginal Canadians, older seniors, and with non-recipient contributors to the CPP) to reinforce their understanding of the program, the various benefits, eligibility requirements, and the application processes.

- To the extent that they are under ESDC control, steps should be taken to address (A) factors that slow benefit processing time, (B) including complex applications resulting from International Social Security Agreements and (C) temporary delays in obtaining duplicate T4 slips.

- In addition, greater effort should be made to keep clients notified of the status of their application from the point of initial submission of the benefit request and receipt of the benefit.

- Improve Service Canada website navigability and awareness in order to encourage use by CPP clients. This would include providing more detailed information than what is currently available. Tailor service and communications to better fit seniors’ current situation with regard to their propensity to go on-line to seek information about the CPP.

Management response

To ensure the Canada Pension Plan (CPP) continues to meet the needs of Canadians, Management takes seriously both the findings of the Summative Evaluation of the CPP Retirement Pension and Survivor Benefits and the resulting recommendations outlined below. Management also acknowledges the important contribution of those who participated in the Summative Evaluation. Drawing on multiple lines of evidence, the Summative Evaluation demonstrates the continued relevance of the Survivor’s and Retirement Pensions. It also confirms that key CPP objectives are automatically achieved because they are embedded in the very design of the Plan.

The evaluation also sheds light on the development of the CPP specifically and the retirement income system in general. Together, these have evolved in a changing socio-economic and demographic context. While the retirement income system is beyond the scope of the Summative Evaluation, it is clear that the efficiency with which the CPP performs creates positive impacts and effects for contributors and on the net costs of other seniors programs and on the tax revenues recovered through the CPP Retirement Pension and Survivor Benefits.

Regarding service delivery, the implementation of the CPP Service Improvement Strategy (SIS) will directly support and build upon the Evaluation’s recommendations. This includes direct measures to collaborate with the Canada Revenue Agency (CRA) to enhance information sharing, reduce factors that slow benefit processing time, potential enhancements to online international applications, and improvements to client access to the status of their application.

Five recommendations are provided in the Summative Evaluation report. These recommendations are important and the Department will respond to them.

Recommendations and responses

- Address deficiencies in the administrative data by ensuring that measures appropriate to evaluation needs are included at source. This would include information on employment history, marital status history (to address problems with assessing survivor benefits take-up rates), and a clearer disaggregation of CPP benefits (such as when retirement and survivor benefits are combined, but the specific benefit cannot be deduced due to the formula used to calculate combined benefits).

ESDC is committed to making evidence-based decisions while also respecting the requirements concerning the collection and use of personal information. As part of the CPP Service Improvement Strategy, we are exploring enhanced information sharing and broader use of administrative data from multiple sources. This will leverage additional data allowing us to streamline and automate processes (e.g. the Death Notification Hub). In pursuing these initiatives, we will identify opportunities to maximize the use of personal information for program policy development while at the same time limiting the collection of personal information for the purposes prescribed under the program.

- Improve communication and outreach with CPP clients (and particularly Aboriginal Canadians, older seniors, and with non-recipient contributors to the CPP) to reinforce their understanding of the program, the various benefits, eligibility requirements, and the application processes.

In 2015-2016, Service Canada Mobile Outreach Services delivered over 10,415 information sessions to 74,276 Canadians across the country. Of these information sessions, Service Canada Mobile Outreach Services delivered over 1,230 information sessions to 15,882 senior citizens and caregivers, community groups and service delivery partners across the country. Service Canada is modernizing its outreach activities in 2016-17 with a new Targeted Reach service which will equip Service Canada with the ability to meet partner’s needs by pro-actively and more directly targeting specific client groups to assist in advancing program objectives and outcomes.

To improve communication and outreach with CPP clients in 2016-17, Service Canada will roll out the Initiative for Reaching Vulnerable Seniors pilot to all Regions. This will be the first example of targeted outreach activities that are aimed at a specific client group (vulnerable seniors which include aboriginal, low-income, disabled, low literacy, etc.) and will be aligned with program outcomes and performance measurement indicators.

- To the extent that they are under ESDC control, steps should be taken to address (A) factors that slow benefit processing time, (B) including complex applications resulting from International Social Security Agreements and (C) delays in obtaining duplicate T4 slips.

(A) ESDC is addressing factors that slow benefits processing time through the CPP Service Improvement Strategy (SIS). The SIS initiatives will be deployed in a number of phases, beginning in late 2016 to September 2019. The SIS is founded on the following 3 key pillars:

- Excellence in Client Service: Key initiatives include providing clients access to self-service online applications and speed up processing for straightforward files. This will enable service agents to focus on complex files and improve their processing times as well

- Excellence in Performance and Results: A number of changes to processes and tools are planned to improve workload management and enable real-time monitoring of performance and results. The Department will consequently be able to react to workload pressures in a more agile manner and take prompt action to address slippage in service standards

- Excellence in Program Stewardship: Managing the long-term sustainability of the CPP program by improving operating costs and leveraging integrity and risk management capabilities

In addition, policy and program simplifications will be explored to support simplified, streamlined and automated applications and business processes with the aim of reducing processing times and improving service.

(B) International Operations continue to work with international Social Security Agreement (SSA) liaison agency partners on an on-going basis to review operational processes to gain efficiencies and improve service delivery. SSA benefit processing, including CPP benefit processing, is within scope of the Old Age Security (OAS) and CPP Service Improvement Strategies, and therefore, will also leverage many of the efficiencies gained through these initiatives.

(C) Delays in obtaining duplicate T4 slips resulting from the implementation of the Corporate Payment Management System have since been resolved. Corrective measures were successfully implemented in July 2015 and the printing backlog was eliminated. Follow-up monitoring has identified no further issues.

- In addition, greater effort should be made to keep clients abreast of the status of their application from the point of initial submission of the benefit request and receipt of the benefit.

The online CPP Retirement application process was launched in June 2015. Applicants are guided through a series of automated workflows where only eligible applicants can perform a formal submission. The system has automatically determined the applicant’s eligibility and therefore provided the applicant with the status of their request.

As more individuals use the My CPP Retirement online application (as part of the CPP SIS), an increasing number of clients will benefit from automation and reduce the need for follow-up due to delays encountered with manual processing.

A planned self-serve Check Status functionality will eventually provide clients with transactional status updates – from time of application is accepted to payment received – within a secure environment over the internet.

- Improve Service Canada website navigability and awareness in order to encourage use by CPP clients. This would include providing more detailed information than what is currently available. Tailor service and communications to better fit seniors’ current situation with regard to their propensity to go on-line to seek information about the CPP.

As part of the Government-wide Web Renewal Initiative, ESDC is moving its online presence to canada.ca.This includes Service Canada’s web pages for the CPP.

The CPP web pages have been using the new canada.ca service initiation template since December 2015. This new template allows users to quickly locate a service, initiate it, and complete the intended task by accessing the service through their channel of choice.

Program, communications and web teams worked closely together to review and update key CPP web pages to also:

- support a consistent approach to task initiation and completion

- provide users with the information they need before initiating the task of completing a service online, in-person or by mail

- ensure that users have read and accepted any mandatory disclaimers (or other legal information) required before initiating the service – after they have triggered the initiation button or downloaded the printable materials and forms; and

- provide easy access to related services, such as: applying for an OAS pension, the Canada Retirement Income Calculator, My Service Canada Account, applying for Direct Deposit, and updating personal information.

As part of the move to canada.ca, ESDC conducted usability testing on the new CPP pages in February 2016. The results demonstrated a 90% success rate on performing specific tasks related to the CPP application process.

Overall, web Renewal seeks to consolidate 1,500 Government of Canada (GC) websites into one website designed to respond to the needs of Canadians first. This initiative aims to enhance the effectiveness and efficiency of the GC online presence through user-centered design principles to create an optimal user experience. Users will quickly and easily do what they need to do, while building trust and credibility. The GC will deliver information and services more effectively and engage with Canadians through more consistent and effective websites, social media and mobile tools. Its implementation will create new opportunities to provide useful communications to the right audiences at meaningful points in time.

Canada.ca’s new information architecture (IA) involves organizing and labelling content, designing a navigation system, and enabling search functions to allow users to complete tasks and find the information and services they need. Content that is published on canada.ca must be organized and labelled in a manner that users understand. Navigation design needs to support user-centred information constructs, and search functions must be wholly integrated into the IA model. The IA supports the user’s experience of canada.ca by improving both usability and findability to build fewer but better and more intuitive methods to navigate and find content.

The CPP’s online presence will increasingly benefit from this initiative as it continues forward.

In addition, in April 2015, ESDC established the Innovation Lab, with a mandate to find innovative solutions to service delivery challenges while promoting greater integration between policy, program and service delivery. The value proposition of the Lab lies in integrating end-user experience in the development of services, and bringing together key stakeholders at the beginning of a project to reduce the incubation period between policy development, program design and service delivery to Canadians.

The Innovation Lab is developing a variety of approaches, utilizing different media, to give Canadians more relevant, detailed and user-friendly information about the CPP on the web, which includes making useful information easier to find. This new information will be designed to help Canadians understand the Plan and make optimal decisions in accessing its benefits based on their personal circumstances and preferences.

Introduction

The Canada Pension Plan (CPP) was introduced in 1965 and, along with Old Age Security (OAS), comprises one of the two public pillars of Canada’s public retirement income system. In 2014-15 alone, the CPP paid out about $38.7 billion in benefits to over 5.3 million beneficiaries.Footnote 4

A comprehensive multi-phase evaluation of the CPP was previously conducted between 1993 and 1997 and included an examination of the CPP retirement pension component and its funding mechanism, the CPP disability benefit, and survivor benefits. A more recent CPP disability benefit evaluation was published in 2011. Thus, this evaluation is necessary to provide more recent evidence on how the program, specifically the retirement pension and survivor benefits, is meeting its objectives.

This report summarizes findings related to a number of topics including the profile of CPP beneficiaries, the CPP income share and income replacement, the contribution of the CPP to economic well-being, program delivery, the CPP impact on labour market participation, and administrative/delivery costs of the CPP. Specific questions can be found in Appendix 1. The evaluation covers the period from 1992 to 2012. Because key informant interviews, focus groups and the expert panel were conducted in 2015, information from these sources includes references to the period after 2012. In addition, more recent figures (post-2012) were included where available.

Methodology and limitations

The CPP administrative data is the most accurate and up-to-date data source unlike sources such as the Census (which relied on self-reporting in 2011) the administrative data uses information directly from the CPP program itself. However, because it is program data designed for administrative purposes, it lacks a complete range of measures to address all of the evaluation questions. Marital status is particularly difficult to determine, as it can change over time and, in practical terms, does not present categories that are necessarily mutually exclusive (as when, for example, a widow reports herself, after a time, as single/not married). This creates barriers for adequately measuring take-up for the survivor’s pension.

This shortfall was addressed by linking the CPP administrative data to income tax data from the Canada Revenue Agency (CRA). However, these linked data (while useful) do not include a comparison group of non-beneficiaries, since they were linked with current CPP beneficiaries only. Further, other data sources used for this evaluation have a wide range of measures but do not include panel data (e.g. the Survey of Financial Security – SFS) or if they do, lack a full range of appropriate measures such as a multifaceted measure of well-being that moves beyond the strictly financial realm, or clear discrete measures of marital status that take into consideration changing status (e.g. the Survey of Labour and Income Dynamics (SLID), or variables that clearly delineate between the retirement and survivor’s pensions (e.g. Longitudinal Administrative Databank or LAD). In addition, data sources which can model changes in the Canadian population (e.g. LifePaths) require the construction of specific modules (which are time- and resource-intensive) to directly address some of the evaluation questions.

To help address some of these limitations, various sources of qualitative data were used (e.g. key informant interviews, expert panel and focus groups) to provide supplemental information to the quantitative lines of evidence.

For these reasons, this evaluation relies on evidence from multiple technical studies using a wide variety of methods (see Appendix 2 for more information). In doing so, the limitations of one particular line of evidence are augmented by the strengths of another line of evidence.

Background information

Canada’s retirement income system

Canada's retirement income system is composed of three pillars (two public and one private):

- Old Age Security (OAS) pension and the Guaranteed Income Supplement (GIS): combine to provide a minimum income guarantee for older CanadiansFootnote 5

- CPP and the parallel Quebec Pension Plan (QPP): compulsory earning-related programs designed to replace about 25% of pre-retirement employment and self-employment earnings

- Private pensions and tax-assisted savings and investment plans such as Registered Pension Plans and Registered Retirement Saving Plans

As one part of Canada’s multi-dimensional retirement income system, the CPP is not intended to meet all financial needs in retirement. It is intended to provide Canadians with a partial replacement of eligible earnings (up to 25%) upon retirement. The CPP provides contributors and their families with three major types of benefits:Footnote 6

- CPP retirement pension: provides a monthly taxable benefit to retired contributors. Those who continue to work while receiving a retirement pension may also receive an increased retirement income which is called the Post-Retirement Benefit

- CPP survivor benefits: paid to a deceased contributor’s estate, if sufficient contributions were made. Benefits may also be available to a surviving spouse or common-law partner (depending on their age and the presence of children and/or disability), and to dependent children (depending on their age)

- CPP disability pension: paid to people who have made enough contributions to the CPP and who are disabled and cannot work at any job on a regular basis. Benefits may also be available to their dependent children

The CPP also includes ‘drop-out’ provisions that help to compensate for periods when individuals may have relatively low or no earnings by basing benefit calculations on years when earnings were higher, as well as progressive features that recognize family and individual circumstances.Footnote 7

Since the focus of this evaluation is on the retirement pension and survivor benefits, only these two types of benefits are discussed in detail below.

CPP retirement pension

The CPP retirement pension is a monthly benefit paid to contributors who are at least 60 years old. It is designed to replace about 25% of the earnings on which a person’s contributions were based.Footnote 8

To qualify for a CPP retirement pension, a person must have worked and have made at least one valid contribution to the CPP. Contributions are made on earnings between the year’s basic exemption and the year’s maximum pensionable earnings.Footnote 9 CPP retirement pension amounts are determined by how long and how much individuals have contributed and at what age they begin to receive benefits.Footnote 10

Flexibility is offered for both older workers and their employers with respect to the age of retirement. For persons electing to take their CPP retirement pension before turning 65 years old, the benefit amount is adjusted downwards utilizing an actuarial factor for each month before age 65. For persons choosing to postpone receipt of their CPP retirement pension until after the age of 65, the benefit amount is adjusted upwards for each month after age 65 up to age 70.

A person can elect to receive a retirement pension and still continue to work. As of January 2012, in cases where a person retires, continues to work, and is under the age of 65, contributions to the CPP are mandatory for both the retiree and their employer. These additional post-retirement contributions will increase the retirement benefit level at age 65, which is called the Post-Retirement Benefit. For persons still working and between ages 65 and 70, additional contributions are voluntary.Footnote 11 No contributions are made after the age of 70.

CPP survivor benefits

CPP survivor benefits are paid to a deceased contributor’s estate, surviving spouse or common-law partner and to dependent children. The three benefit types are:

- The death benefit: a one-time payment to, or on behalf of, the estate of a deceased contributor

- The survivor pension: a monthly pension paid to the surviving spouse or common-law partner of a deceased contributor

- The children’s benefit: a monthly benefit paid to the dependent children of a deceased contributor under age 18, or between the ages of 18 and 25 and in full-time attendance at a school or university

The deceased must have contributed to the CPP for ten years, or for at least one third of the total number of years in his or her contributory period (with a minimum of three years) in order for the contributor’s estate, survivor or children of the deceased to receive one or more of the survivor benefits. The death benefit is equal to six times the amount of the decreased contributor’s monthly retirement pension at age 65, up to a maximum of $2,500. This maximum was set in 1997 and is not adjusted annually to inflation. Prior to the change, the maximum was equal to one-tenth of the Year’s Maximum Pensionable Earnings.

The survivor pension amount is based on a calculation of how much the contributor’s retirement pension was, or would have been, if the contributor had been 65 years old at the time of death. A further calculation is then made using the survivor’s age at the time of the contributor’s death. The survivor pension can be combined with either the disability or retirement pension of the survivor, capped at the maximum benefit level for the disability or retirement pension.

The maximum monthly survivor pension in 2016 for those under age 65 is $593.62. This includes a flat-rate portion of $183.93 and an earnings-related portion of $409.69 (37.5% of the deceased contributor’s retirement pension). The maximum amount at age 65 and over is $655.50, which is equal to 60% of the deceased contributor’s retirement pension. The children’s benefit in 2016 is a flat-rate amount of $237.69 per month. Footnote 12

Objectives of CPP benefits

In the 1964 CPP White Paper, it was noted that the CPP was designed to provide “reasonable minimum levels of income available at normal retirement ages, to people who become disabled, and to the dependents of people who die”. Although demographic and economic conditions have changed since the CPP was first introduced, the objectives of the program have not changed from what was originally stated in the CPP White Paper.Footnote 13

According to the expert panel conducted as part of this evaluation, there continues to be a demonstrated need among retired Canadians for the CPP. It provides a secure and portable earnings-related pension program that guarantees the lifetime continuation in retirement of a specific and defined portion of a contributor’s average income (as well as clearly specified survivor benefits in the case of the death of a contributor). The CPP balances individual equity (benefits are largely based on individual contributions to the program) with social insurance; for the latter, insofar as the pooling of risk offers participants a more affordable and accessible method of income protection, in the case of both retirement and unanticipated income loss, than might be available to many Canadians from private sources. In this way, poverty among the retired is no longer primarily addressed via social assistance mechanisms.

With respect to survivor benefits, the literature review indicated that they were originally designed to support families where a wage earner died and where the survivors were unable to support themselves. Since the inception of the CPP, the demographic and socio-economic context has changed significantly:

- There have been significant increases in women’s participation in the labour force, which has potentially increased the financial capacity of many households with two earners

- The number of re-marriages and blended families has increased. For example, the number of widows who were lone-parents declined from 34.7% in 1980 to 19.4% in 2011.Footnote 14 Many families receiving survivor benefits are no longer composed of a widow (who was usually a non-earner) and dependent children compared to when survivor benefits were first implemented

- Compared to the 1960s, the maturation of Canada’s retirement income system has increased the number of retirement saving vehicles (such as Registered Retirement Savings Plans and Tax-Free Savings Accounts) available to Canadians (including widows and widowers), which is playing an increasingly significant role in their retirement preparedness. In addition, the OAS Allowance was introduced to provide additional income for an eligible spouse of an OAS/GIS recipient who was, nonetheless, below the age threshold for receiving an OAS pension

Despite the above changes, female survivors remain a financially vulnerable group compared to their male counterparts (Townson 2009),Footnote 15 survivor families are still in a more precarious financial position due to the impact of widowhood (James 2009),Footnote 16 and many low-income Canadians do not have sufficient savings to take advantage of private retirement savings plans (Statistics Canada 2010)Footnote 17 – necessitating a continued need for survivor benefits.

Expert panel participants noted that the context within which the CPP came into being was characterized by a lack of a portable retirement income replacement vehicle other than OAS benefits and a social structure that assumed a single-earner family. This had the effect of putting many survivors (mostly women) in financial jeopardy upon the death of a spouse. However, the expert panel suggested that women’s vulnerability has declined significantly (but not completely) since the inception of the CPP. Notwithstanding, the expert panel found that even if women earned exactly the same amount as men, there would still likely be enough differences in gender-based mortality rates and age of marriage to make the issue of widows’ financial security an ongoing concern. Indeed, as the proportion of married/common law women who are currently in the labour force has (statistically) plateaued, there is little room for additional family income to compensate upon the death of a spouse. For this reason, it is possible to see how family income might suffer from the death of a spouse more in the current socioeconomic climate than in the past.

As a self-calibrating program, the CPP has automatically responded to these socio-economic changes. As women’s earnings and their own retirement pensions under the CPP have risen, the limit on combined benefits has reduced their survivor benefits. In addition, the 1998 reform revised the calculation of combined benefits.Footnote 18 Finally, there was a decrease in the quantity of children’s benefits being paid. In 1979-80, children’s benefits represented 20% of total survivor benefits expenses compared to only 5% in 2014-15.Footnote 19 As a result, the proportion of survivor benefits as a percentage of total CPP benefits paid fell from 20.1% in 1980-81 to 10.8% in 2014-15.Footnote 20

Program design

Federal and Provincial Finance Ministers review the state of the CPP every three years to ensure that the Plan remains financially sustainable and to determine whether any changes are required.Footnote 21 As a result, the CPP has adapted to better meet the needs of Canadians.

Between 1992 and 2012 (the period covered by this evaluation), two substantial reforms were introduced to the CPP which supported and enhanced sustainability, and fairness of the CPP:

- The 1998 reform changed the CPP from pay-as-you-go financing to steady-state funding.Footnote 22 The combined employer-employee contribution rate was increased to 9.9% by 2003. As well, the CPP Investment Board was established to obtain a higher rate of the return on the CPP reserve fund. According to the 2014-15 Annual Report of the CPP, the 1998 reforms significantly improved the financial sustainability of the CPP and “fairness across generations” with regard to funding the programFootnote 23

- The 2012 reforms included the following changes to the CPP:Footnote 24

- The actuarial factor for pre-age-65 or post-age-65 commencement of retirement pensions was changed to restore actuarial fairness;

- Changes were made to the general drop-out provision to further protect workers from work interruption;

- The Work Cessation Test was eliminated to better accommodate gradual transitions to retirement from the labour force; and

- The Post-Retirement Benefit was introduced to allow working retirees to build income in retirement by continuing to participate in the CPP.

Overall, these changes help ensure that the current design of the CPP remains consistent with its legislative mandate and objectives.

Roles and responsibilities

From an economic perspective, a fundamental role of the government is to provide public goods and services that cannot be efficiently provided by the private sector. Providing a mandatory public pension is a classic example of such a public good. It can be justified on both equity and efficiency grounds. From a legislative perspective, the delivery of the CPP is consistent with Sections 5 and 6 of the Department of Employment and Social Development Act, which guides the Minister in the capacity to improve the quality of life of Canadians by allowing the use of information as seen fit to achieve this goal.Footnote 25

The CPP is a joint federal-provincial program.Footnote 26 As stated in the CPP White Paper, federal legislation on pensions and supplementary benefits shall not affect the operation of any present or future provincial legislation with respect to pensions. The federal objective can be achieved only in cooperation with the provinces. Any changes made to the CPP require the agreement of two-thirds of the provinces carrying two-thirds of the population.

The administration of the CPP falls under the mandate of ESDC while the CRA collects contributions on behalf of the program. The CPP is delivered through Service Canada across nine provinces and the territories, while the QPP operates in Quebec as a parallel plan. Funding of the CPP is made through mandatory contributions by virtually all Canadian workers, their employers and the self-employed, as well as revenue earned on CPP investments.Footnote 27

Finance Canada leads the Triennial Review process during which federal and provincial finance ministers assess the CPP’s financial health and also review the Plan to ensure that it continues to meet its objectives as the needs of contributors evolve over time.

Relevance of CPP benefits

This section examines questions related to the relevance of the CPP. Two of the key evaluation questions in this section include:

- Do the objectives of the CPP align with federal government priorities and ESDC strategic objectives?

- What other countries provide a similar public pension program and how does the CPP compare to similar programs in these countries?

Alignment with federal government and departmental priorities

The literature review conducted as part of this evaluation noted that supporting seniors and protecting families have been constantly identified as government priorities for the past two decades. The CPP contributes to this priority by providing:

- a retirement pension to working Canadians when they reach the age of 60 years;

- disability benefits to the contributor and their children when a disability prohibits working;

- benefits to survivors (including children) in the event of death; and

- pension sharing and credit splitting among couples.

The CPP also contributes to the government priorities of helping Canadians achieve a safe, secure and dignified retirement and of empowering all Canadians, including seniors, to build better lives for themselves through:

- the Post-Retirement Benefit, which provides enhanced flexibility in making retirement decisions;

- the general drop-out provision, which takes into consideration work interruptions caused by involuntary job losses; and

- the elimination of the Work Cessation Test to support phased transitions to retirement.

By providing working Canadians and their families with a reasonable minimum level of income in the case of retirement, disability or death, the CPP directly supports ESDC’s mandate to build a stronger and more inclusive Canada, to help Canadians live productive and rewarding lives, and to improve their standard of living and quality of life.

International comparison

There is a wide variety of retirement and survivor pension programs across the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries, based on their different roles, objectives, funding mechanisms, program design features, and culture. In order to make meaningful comparisons of these programs, it is important to examine these programs on their own as well as against the country’s fiscal context and overall social security regimes/programs.

According to the OECD’s global classification for pension plans, many countries’ retirement income systems consist of a redistributive first-tier, an earnings-related second-tier, and a voluntary third-tier.Footnote 28 The CPP is most comparable to other publicly managed earnings-related pension programs under the second tier in other countries. Like the CPP, these programs are mandatory and financed by contributions. However, unlike the majority of these plans which operate on a pay-as-you-go basis, the CPP adopted a sustainable partially-funded model in the late 1990s.

Many OECD countries have similar pension policy objectives and a comparable public pension program design. Like Canada, there is a focus on the financial well-being of lower-income groups and specific vulnerable groups (e.g. survivors).

For a more meaningful comparative analysis, the countries to be compared to Canada with regard to their public pension programs should have not only earnings-related pension programs similar to the CPP but also comparable living standards and the institutional environment, specifically the U.S., the UK, France, Germany, Sweden, Switzerland, and Australia.

The expert panel convened as part of this evaluation noted that other countries have a similar mix of first-tier (guaranteed pensions) and second-tier (earned pensions) systems as Canada, although the specific elements of the pensions may vary. For example, the U.S. first-tier pension is tightly targeted in terms of need (instead of being more universal as OAS). The UK is in the process of changing their pension system from a mix of a flat rate and an earnings-related plan to one flat rate Basic State Pension plus a quasi-mandatory employer-based defined contribution pension plan. Germany has only one tier, an earnings-related pay-as-you-go system.Footnote 29

Based on findings from the international comparison study conducted as part of this evaluation, Canada’s retirement income system is recognized internationally as among the strongest in the world. The strengths of the system are based on its long-term sustainability, balanced mix of mandatory and voluntary pillars, and shared public and private responsibility. According to the Department of Finance, this system has resulted in Canada having a very low rate of poverty and high rates of income replacement among seniors.Footnote 30

The major similarities and differences between these programs can be summarized as follows:

- Overall schemes: Canada, Australia, Switzerland, the UK and U.S. have some degree of a defined benefit scheme, in which benefits are predetermined by earnings history and age. France and Germany have a scheme where workers earn pension points based on their earnings each year which are then converted into pension payments at retirement. Sweden has a notional-accounts defined contribution scheme which records contributions in an individual account and applies a rate of return to the balance. These three schemes are closely related variations of earnings-related pension schemes, as the structures are essentially similar.

- Pension calculation: France, Germany and Australia have a linear accrual rate like Canada, while the U.S., UK and Switzerland have an earnings related accrual rate and Sweden’s accrual rate increases with age. Canada, the U.S., France and Australia weight their pension calculation on the best years of earnings while Sweden, Switzerland and the UK use lifetime average earnings. Indexation: With regard to indexing benefits to rising cost of living, France, the UK and U.S. use price indexation, while Germany and Sweden use wage indexation. Switzerland uses both prices and wages and Australia uses a discretionary price indexation that is reduced for high pensions. In Canada, wage indexation is used for contributions and price indexation for benefits.

- Survivor programs: Although eligibility criteria and benefit coverages are different, all of the selected countries have earnings-related survivor pension schemes under the second tier. These survivor programs generally supplement as an explicit add-on to the retirement pension program, paying a specific percentage of the actual or potential primary benefit to the survivor.

According to the expert panel, only the UK has had notable reform initiatives in recent years. The UK’s retirement pension is currently being changed from a mix of first-tier and second-tier (guaranteed and earnings related) plans to a flat rate Basic State Pension plus a quasi-mandatory employer-based defined contribution pension plan. The new Basic State Pension does not include survivor benefits.Footnote 31 However, widows and widowers currently may receive benefits based on credits earned under the former state pension plan.

Achievement of program objectives

This section examines questions related to the achievement of program objectives of the CPP as it relates to the contribution of CPP benefits to total income and well-being. The three key questions in this section include:

- What percentage of CPP beneficiaries’ total income is represented by CPP benefits and how does it vary by beneficiary type?

- What would be the level of income among CPP beneficiaries (in relation to low-income measures) if CPP benefits were not available?

- What earning replacement rate is provided by the CPP retirement pension and how does it differ by beneficiary type?

Before addressing the achievement of program objectives, this section begins with a profile of CPP beneficiaries.

Profile of CPP beneficiaries

Table 1 provides a profile of CPP beneficiaries by gender, marital status and age.

| Retirement pension | Survivor pension | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1992 | 2012 | 1992 | 2012 | |

| Gender* | ||||

| Male | 56.4 | 49.1 | 9.7 | 17.2 |

| Female | 43.6 | 50.9 | 90.3 | 82.8 |

| Marital status** | ||||

| Married/Common-law | 68.9 | 67.2 | 12.7 | 12.4 |

| Widowed | 11.8 | 14.9 | 81.5 | 80.6 |

| Other | 19.3 | 18.0 | 5.8 | 7.0 |

| Age* | ||||

| 60-64 | 14.9 | 17.7 | 32.5 | 22.4 |

| 65-69 (65+ for survivor) | 31.6 | 27.3 | 67.5 | 77.6 |

| 70-74 | 24.2 | 20.0 | Not available | Not available |

| 75-79 | 16.1 | 14.9 | Not available | Not available |

| 80-84 | 8.8 | 10.8 | Not available | Not available |

| 85+ | 4.3 | 9.2 | Not available | Not available |

Sources:

- * 2013 CPP and OAS Stats Book

- ** Linked CPP Administrative and CRA T1 Income Tax Data

According to the 2013 CPP and OAS Stats Book, 50.9% of all CPP retirement pension beneficiaries were female in 2012 – up from 43.6% in 1992 – reflecting increased labour force attachment (primarily in the form of full-time employment) for women and, consequently, increased eligibility for a CPP retirement pension. During this same time period, the proportion of survivor pension beneficiaries who were female decreased from 90.3% to 82.8%.Footnote 32

The linked CPP-CRA data analyses revealed that the share of retirement pension beneficiaries in a married/common-law relationship decreased from 68.9% in 1992 to 67.2% in 2012, while the share identifying as widowed increased from 11.8% to 14.9% (there was little change by other marital status type). Among survivor benefit recipients, there was minimal change over this period, with roughly 12.7% to 12.4% identifying as being in a married/common-law relationship, 81.5% to 80.6% identifying as being widowed, and the remainder indicating being single, divorced or separated (5.8% to 7.0%).

Additional information from the 2013 CPP and OAS Stats Book (as presented in Table 1) showed a significant change in the profile of CPP retirement pension beneficiaries by age between 1992 and 2012. The share of beneficiaries aged 60-64 increased from 14.9% to 17.7%, the share aged 65-79 fell from 71.9% to 62.2%, and the share aged 80 or older increased from 13.2% to 20.0%. Of particular note is that the share aged 85 and over more than doubled, from 4.3% to 9.2%. There was also a major shift in the distribution of survivor benefit recipients between 1992 and 2012. The share under the age of 45 declined from 4.8% to 1.5%, the share aged 45-64 fell from 27.6% to 21.0%, and the share aged 65 or older increased from 67.5% to 77.6%.

In terms of education, the Census study noted that individuals with a high school diploma were significantly more likely to receive a CPP retirement pension than those who did not finish high school (the SLID study produced similar findings). For example, 71% of the population over age 70 with a high school diploma received a retirement pension in 1991 compared to 62% for those with less than high school (the respective numbers for 2011 were 92% and 87%). In terms of survivor benefits, the SLID study indicated that those aged 35-59 with less than a high school degree were slightly more likely to receive survivor benefits than those with higher levels of education.

Finally, foreign-born individuals have a lower likelihood of collecting CPP benefits. The SLID study demonstrated that while foreign-born Canadians aged 60-84 accounted for 41.9% of all CPP retirement pension recipients during the 2006 to 2010 periodFootnote 33, they accounted for only 29.3% of retirement pension recipients (they were similarly less likely to collect survivor benefits). However, the magnitude of the difference was particularly large for those not born in the U.S. or in Europe. The LAD study further noted that more recent immigrants (specifically those landing since 1990) were far less likely to receive CPP benefits in 2012, while the Census study showed that the younger an immigrant was when they first arrived in Canada, the more likely they were to collect CPP benefits. In fact, the Census study showed that there was little difference in the receipt of CPP benefits between individuals aged 65 and over who were born in Canada and immigrants who arrived in Canada before the age of 40. It is not clear from the data whether or not immigrants were less likely to receive a retirement pension because of ineligibility (i.e. not enough contributions in Canada) or due to lack of awareness. The CPP provides payments internationally and Canada has pension agreements with numerous other countries where foreign pension payments are provided to immigrants living in Canada.Footnote 34

CPP income shareFootnote 35

General trends

Human Resources Development Canada (1995) noted that the CPP/QPP retirement pension represented about 17% of the gross income of beneficiaries in 1991. More recent data using 2012 estimates from the Longitudinal Administrative Databank (LAD), Survey of Financial Security (SFS) and linked CPP-CRA studies indicated that the CPP retirement pension constituted 20% to 25% of gross income for beneficiaries.Footnote 36 Survivor benefits in 1991 were not a significant income source for most recipients, but for women with $10,000 in annual income or less they represented 35% to 60% of household income.Footnote 37 Linked CPP-CRA analyses for survivor benefits showed that they constituted between 6% and 15% of the total income of survivor beneficiaries during the period from 1992 to 2012.Footnote 38 A substantial increase in this proportion was seen between 2011 and 2012 when it went from just under 10% to 15% of total income.

By beneficiary characteristics

In general, most of the studies completed for this evaluation confirm that the CPP share of total income is lower among those still employed compared to those who are retired (as employment income will represent a large share of total income). As a result, most factors correlated with employment (such as being younger, having a higher level of education, and having a higher level of family income) will result in CPP benefits constituting a lower relative share of total income.

According to the LAD study, the CPP retirement pension share of 2012 income was much higher among lower-income families compared to higher-income families. For example, the average CPP share of income of those aged 60 to 69 was about 33% for those with a total family income below $20,000 and about 20% for those with a total family income above $50,000. For the same income levels among those aged 70 to 79, the corresponding figures were roughly 25% and 21%. For survivor benefits, the average share of income among recipients below age 60 was 37% and 8% for men with a family income below $20,000 and $50,000, respectively, and 44% and 14% for women.Footnote 39

The LAD report also indicated that CPP benefits as a share of total income averages around 25% by age 70 (i.e. the point at which there is no longer any advantage to delaying CPP take-up). The CPP-CRA data analysis showed a rapid increase in CPP share of total income just after take-up (from approximately 14% of total income to about 20% of total income two years later) due to many beneficiaries ceasing to work. There was a leveling off at roughly an average of 20% to 22% of total income thereafter. Survivor benefits as a share of total income rises steadily and peaks at an average of 12% between the ages of 60 and 64.

LAD findings regarding immigration status indicated that CPP benefits as a share of total income in 2012 were lower for more recent immigrants than for those who had been in Canada for a longer period of time (more than 23 years). For example, for post-1989 immigrants who were between age 70 and 79 in 2012, only about 7% of their income, on average, came from a CPP retirement pension (compared to 25% for 70-79 year-olds who had been in Canada since at least 1979). Survivor benefits represented, on average, 10% to 11% of the total income for those who came to Canada after 1989 who were between 70 and 79 years old in 2012 (compared to 27% for those who had been in Canada since at least 1979).Footnote 40 SLID findings further noted that European immigrants derived a higher proportion of their total income (roughly 24%) from the CPP retirement pension than non-European immigrants (roughly 22%).

Income replacement

The income replacement rate is the percentage of pre-retirement income that needs to be replaced in order to maintain a continuous standard of living after retirement. Since expenses usually decrease after retirement (such as those related to employment, housing, pension plans, and children, and decreased costs of living for seniors which accrue from seniors’ discounts and tax credits),Footnote 41 findings from the literature review suggested that a replacement rate of between 50% and 70% is sufficient to maintain a pre-retirement standard of living for most Canadians.Footnote 42 Target replacement rates vary depending on a number of factors such as the income measure used (e.g. gross or net), income levels, the number of members in a household, home ownership, or whether it is lifetime average income or income immediately prior to retirement that is replaced.

The other way to calculate the replacement rate focuses on actual consumption rather than income. It assumes that people wish to arrange their affairs so that their consumption possibilities stay the same after the transition from paid work to retirement. It is referred to as the consumption replacement rate and takes into consideration variations, over the life course, in taxes, savings, and other factors. It measures what people actually spend in retirement and estimates the income needed to generate that level of consumption. Many households downsize as they approach the retirement period, partly because children are leaving. How this is handled in a study greatly matters. Using a consumption measure adjusted for possible economies of scale, many recommend that the optimal rate for such a replacement should be between 85% and 100%.Footnote 43 This optimal replacement rate can be expected to vary over the retirement period (e.g. people in their 80s spend differently, often less, than people who have just retired). Although a desirable theory, the net consumption replacement rate requires precise measurements of spending patterns and detailed estimates of wealth, as well as many implicit assumptions such as those related to the treatment of housing and durables, and economies of scale associated with a larger household.

The CPP is designed to replace approximately 25% of the earnings on which one’s contributions were based.Footnote 44 The previous CPP evaluation in 1995 examined earnings replacement rates provided by the CPP retirement pension in 1993 and concluded that the CPP was meeting its objective of replacing 25% of average pensionable earnings. The primary objective of the CPP is to replace a specific and defined amount of pre-retirement income. Poverty reduction is the objective of the overall retirement income system, which includes the first tier (OAS/GIS) and third tier (private sources of retirement income).

Contribution to well-being

Income and wealth measures do not capture all aspects of well-being. Overall well-being after retirement is also affected by many personal and environmental factors. Using subjective measures of well-being to assess the living standards of retired individuals, a recent study found high levels of overall satisfaction in life among Canadian retirees, despite the declining income among retired Canadians reported in studies using income or wealth measures.Footnote 45

Focus groups conducted with CPP recipients indicated that they consider the contribution of the pension to their well-being to be positive. Generally speaking, there is an inverse relationship between the amount of current economic resources (e.g. retirement income, workplace pension) and the perceived importance of the CPP, with those having fewer resources indicating that the pension contributed more to their well-being than those with greater resources. The findings were the same when focus groups with CPP recipients were asked about financial security – the CPP was more important among those with lower retirement income.

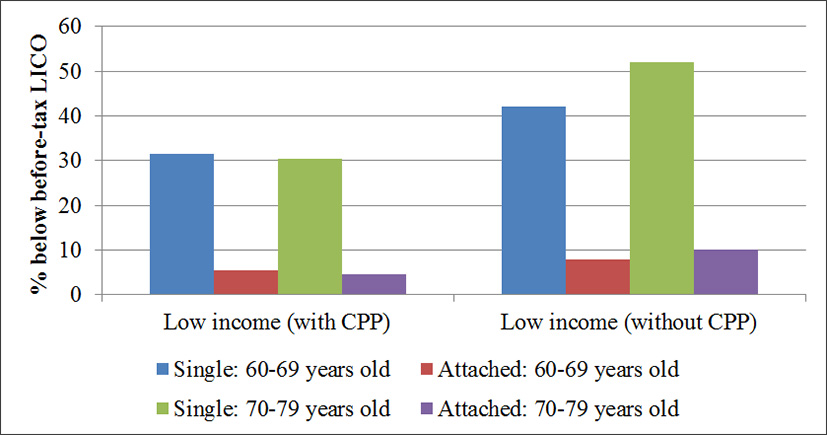

Evidence from the LAD study (see Appendix 2) suggests that there would be a significant reduction in income and well-being if the CPP did not exist. Using Statistics Canada’s before-tax low income cut-off (LICO), the LAD study showed that the presence of a CPP retirement pension reduced the incidence of low income from 16% to 11% among 60-69 year-olds and from about 22% to 11% among 70-79 year-olds.Footnote 46 Differences were more pronounced when considering marital status (see Figure 1).Footnote 47

Text description of Figure 1

Figure 1 shows that single individuals are far more likely than attached individuals to be considered to be in low income (i.e. below the before-tax LICO) – whether they receive a CPP retirement pension or in the absence of one.Footnote 48 For example, the share of attached CPP retirement pension beneficiaries aged 70-79 with low income was only 5% and would have increased to 10% in the absence of the CPP retirement pension, while the share of single beneficiaries aged 70-79 below the LICO was 31% and would have increased to 52%.

Source: Data Probe Economic Consulting Inc. (2015), “Evaluation of the Canada Pension Plan Retirement and Survivor’s Pensions – Based on the Longitudinal Administrative Databank”.

Note: that CPP retirement pension beneficiaries may also be receiving survivor benefits.

Program delivery issues

This section examines questions related to program delivery – specifically communications and outreach activities, awareness, processing and take-up. The three key questions in this section include:

- How effective are outreach activities that publicize the CPP and what is the level of awareness?

- Has service quality changed over time?

- What are the take-up rates of CPP survivor benefits and the retirement pension?

Program communications/outreach and awareness

According to key informants (Service Canada employees across Canada),Footnote 49 CPP clients typically receive CPP information from many sources, with the most common sources being Service Canada (including in-person centres, call centres and online), word of mouth, funeral service providers (for information on survivor benefits and death benefits), community groups, and financial service providers. However, based on interviews with CPP contributors (who are not yet receiving a pension), little is understood about the program other than the fact that it is a pension one receives from paying mandatory contributions and that there is an age requirement for receipt of a pension. Most contributors interviewed had not sought information on the CPP nor were they aware of outreach information.

The same group of key informants as above further noted that many CPP clients, especially older clients ”not in their early 60s”, did not access the Service Canada website prior to calling the 1-800 number or going to an in-person service centre. In addition, many clients preferred in-person services.Footnote 50 Those who did consult the website before contacting a Service Canada agent, tended to have difficulty in navigating the site and setting up a My Service Canada Account. Information on the website was also considered too general. In focus groups, CPP recipients indicated that they would go to the Government of Canada for information, but were not aware of mobile outreach services or CPP clinics.Footnote 51

According to those delivering the services, the most misunderstood program information among clients included issues surrounding taxability (specifically, that one can request that tax be deducted directly from their CPP pension payment) and the application process itself. Even after accessing Service Canada information (both online and printed materials) there was still confusion related to combined benefits, benefit calculation/entitlement, the child-rearing provision, credit splitting, the combining of pensions from other countries, and the Post-Retirement Benefit. As indicated from interviews of Service Canada staff, many clients were also not familiar with, or were confused about, how to set up a My Service Canada Account, the Canadian Retirement Income Calculator, and the Benefits Finder on the Service Canada website.

Service Canada informants suggested the following three ways to increase awareness and understanding among CPP clients:

- Adding/expanding outreach activities:

- Pension clinics and information sessions targeting older seniors;

- Sessions in Aboriginal communities to create a level of comfort and to deal with complexities with regard to Aboriginal workers; and

- Partnering with other government organizations to provide combined sessions on pensions/taxes.

- Increased advertising:

- Traditional (television and radio stations, newspapers, magazines, and pamphlets); and

- Digital (webinars, social media, chat rooms and video conferences, links to CPP information on other websites).

- Stakeholder training (e.g. further training of third-party stakeholders to improve understanding).

Communicating information about the CPP to contributors is important and is conveyed via a number of institutions and organizations, including those outside of government. Interviews with contributors indicated that the main stakeholders/sources of information involved in the outreach process were provincial and territorial governments (especially social services), employers, social and health workers, financial service providers, community groups, and the CRA. As well, funeral service providers not only convey information but also deliver certain types of services (such as application services) to potential beneficiaries of survivor benefits.

Program delivery and processing

Findings from the focus groups confirmed that clients in general find it easy to apply for the retirement pension. However, a small minority of focus group participants indicated that they still had difficulty with obtaining the application form (it is no longer mailed out by call centres) and filling it out (including trouble reading due to a disability or frustration with not being able to add an electronic signature),Footnote 52 navigating the options presented when calling the 1-800 number, setting up a My Service Canada Account, and the two-step online process which requires mailing in a signed page.

For the survivor benefits application process, focus groups participants (most of whom were female) generally found the process simple and straightforward, a positive experience given the stressful context in which it was requested. Service Canada staff did note that some clients were frustrated with the process being long and overwhelming, gaining authorization to access information on a deceased client’s file, having to provide proof for common-law relationships, and the fact that no benefits were paid out to those without spouses or children.

In terms of processing time, Service Canada has committed to achieve a processing time of 28 days (maximum) to process a CPP retirement pension payment and between 6 and 12 weeks to process a survivor benefits payment (in both cases, ‘processing’ includes the receipt of the first payment by a beneficiary).Footnote 53 Findings indicated that in 2011-12, 96% of 300,000 retirement pensions were processed (and paid) within the first month of entitlement.Footnote 54

A special process is also in place to expedite processing time for clients in “dire need” situations who require the benefits urgently in order to meet their daily expenses. However, according to the Service Canada personnel interviewed for this evaluation, processing is not considered timely for the following situations/reasons:

- Complex applications (such as dual CPP/QPP benefits and benefits involving International Social Security Agreements) that are processed at National Headquarters;

- Temporary delays in obtaining duplicate T4 slips; and

- Clients do not receive any notification between the submission of their application and the receipt of their first payment, which can take up to a maximum of 12 months. This was seen as stressful for clients insofar as they do not know if their application has been approved.

The experiences reported by CPP beneficiaries in the focus groups, with regard to processing time, were positive. The majority of focus group participants indicated that they were satisfied with the amount of waiting time between application for a retirement pension or survivor benefits and the receipt of first payment.

That being said, Service Canada personnel interviewed for this evaluation considered the processing time for survivor benefits of two to four months to be too long, as it comes at an inherently difficult and stressful time when there is emotional upheaval, lost income, and extra expenses. Service Canada personnel also noted that it was challenging to provide timely and high quality service at the same time, especially during high volume periods. Also making things more difficult were an increased workload accompanied by significant staff reductions, organizational and structural changes in processing centres, and frequent upgrades to internal systems.

Findings from the CPP Annual Reports and the Service Canada Performance Package indicate a decline in client service times.Footnote 55 The data indicate that the proportion of calls answered by a Service Canada agent within 180 seconds declined from highs of 82%Footnote 56 , 96%Footnote 57 , and 99%Footnote 58 in 2001-02, 2002-03, and 2003-04, respectively, to lows of 61%, 52%, and 51% in 2009-10, 2010-11, and 2011-12, respectively.Footnote 59 These were general service calls and, as such, were not necessarily about CPP concerns.

The average number of working days to process initial CPP applications (excluding disability applications) declined from 31 days in 2000-01 to 22 days in 2003-04. From 2004-05 to 2011-12, the percentage of CPP retirement pension benefits paid within the first month of entitlement was well above the 85% national objective in each year.

The Annual Report of the CPP also indicated that since its launch, Service Canada has continually updated its Internet service options, which have led to an increase in the number of CPP retirement pension applications made online.Footnote 60 Additional service delivery changes noted by some key informants included the use of internal computer programs to improve the working connections between call centres, in-person centres and processing centres. However, Service Canada staff commented that the new program-specific systems and HR systems could be difficult to use, and have been found to slow down service delivery.

Key informants (as represented by Service Canada staff) stated that service delivery was considered to have deteriorated due to the emergence of a two-tiered service model. According to this model, in-person service officers are considered generalists who have access to limited information and tools, are not provided training required to provide more than standard information, and do not have authority to access certain kinds of information. In order to access specific information about or make changes to an individual file, in-person service officers have to refer clients to the specialized call centres, creating a higher workload for themselves and the call centre agents at the same time, and leaving clients frustrated as they are not getting the level of in-person service they would like.

Additionally, it was pointed out that a number of sub-populations (below) face particular challenges with accessing the information and services they need:

- Seniors who were “not in their early 60s” (as defined by key informants)

- The primary barrier involves a lack of computer literacy and a lack of desire to use a computer. Poor hearing and memory also make it difficult for older clients to utilize certain services available to them

- Aboriginal people

- Employers on reserves are not required to contribute to the CPP.Footnote 61 As a result, some Aboriginal workers may have missed the opportunity to make CPP contributions while working on-reserve (even though they can opt to do so if they wish to)

- For those working on reserves and earning non-taxable income, there is uncertainty regarding the taxability of their CPP benefitsFootnote 62

- There is anxiety when dealing with government

- Some Aboriginal groups face language barriers. In one case mentioned in the key informant interviews, CPP forms and basic information were not available in the native Slavey language

- Immigrants

- Language barriers and awareness of the International Social Security Agreements Canada has with many other countries

- Residents of remote areas

- Mobility is an issue in communities where there are no Service Canada Centres, especially for those who rely on public transportation or help from family members

- Internet connectivity can pose difficulty for both the residents and the mobile outreach service locations

- Some areas have no banks or ATM machines

CPP take-up

The proportion of people who are eligible for a CPP benefit who actually receive these benefits is known as the ‘take-up rate’.Footnote 63 Evidence from the LAD report illustrated that the take-up rate for the retirement pension among contributors to the CPP was virtually 100% for eligible men and women by the time they reached 70 years of age. However, this was not the case among those who are less likely to participate (i.e. to make contributions) in the CPP, such as immigrants who came to Canada after 1989 (95% take-up) or individuals below the Low Income Cut-Off (98% take-up).Footnote 64 That being said, these two groups are a small proportion of those eligible for the CPP.Footnote 65

Based on findings from the literature review, in 1999 approximately 55,000 eligible Canadians were missing out on receiving the CPP retirement pension. In 2007, about 26,000 individuals who were in receipt of OAS, GIS or CPP survivor benefits had not applied for their CPP retirement pension.Footnote 66

A lack of take-up of government benefits, including the CPP, can be explained by awareness and/or limitations in the knowledge, skills and confidence that constitute financial literacy. Other factors such as complex program design, a lack of government outreach efforts, and certain characteristics of the target population may also play a role.

While participation in the CPP is mandatory for most employees and employers, when looking at the general population of Canadians, notable differences in participation arise. This is due to whether or not one is working and contributing to the program. With respect to overall participation in the CPP (rather than take-up among those eligible for a pension), the analysis based on Census data from 1991 to 2011Footnote 67 conducted for this evaluation identified several characteristics that appeared to have influenced the share of the population in receipt of CPP benefits.Footnote 68

Overall, being unemployed, female, an immigrant, a visible minority, having an education level lower than a high school degree, or having a lower income were all characteristics associated with a lower probability of participation in the CPP among those aged 70 years old or more. That said, female participation increased considerably from 1991 (when 56.1% were receiving benefits compared to 79.9% of men) to 2011 (when 88.6% of women and 93.2% of men were receiving benefits). A similar change is seen for those with less than a high school education (62.0% in 1991 versus 87.7% in 2011).

Note that the take-up rate for survivor benefits could not be calculated using the available data sources, as it is difficult to derive an accurate estimate of those who are eligible (i.e. widows and widowers). If one uses a similar concept, incidence, nearly 100% of widows over 70 years of age received a survivor pension in 2012, compared to 62% of widowers.

Impacts and effects

This section examines questions related to the impacts and effects of the CPP – namely on labour market participation and on other sources of income. The two key questions in this section include:

- What is the impact of the CPP benefits on beneficiaries’ employment activity/status and how does this vary by different factors?

- How do CPP benefits impact other sources of income and what is the effect of the loss of contributor income on family income?

CPP impact on labour market participation